User login

Perianal Condyloma Acuminatum-like Plaque

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

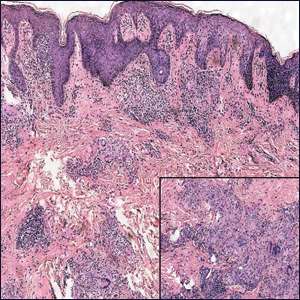

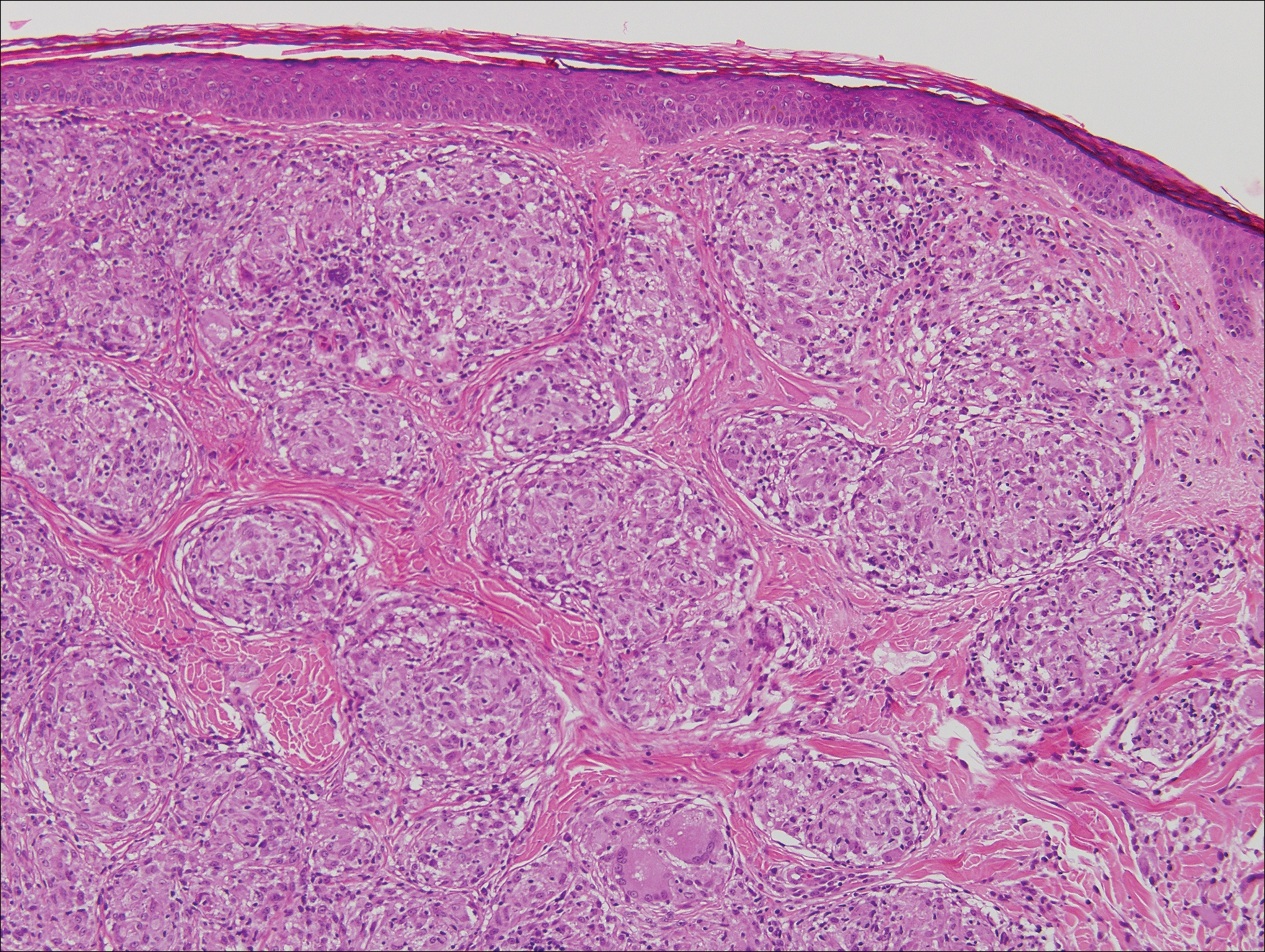

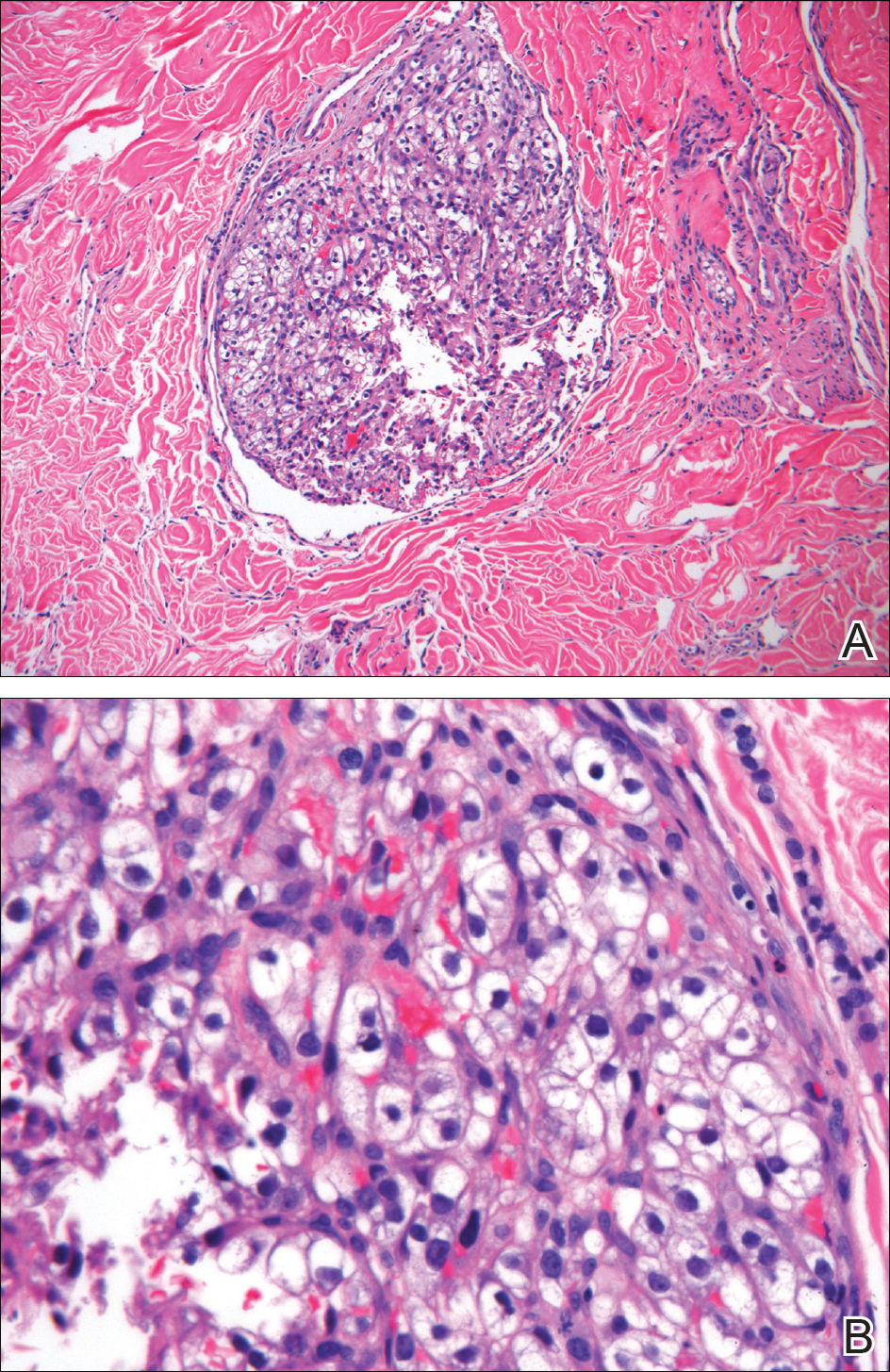

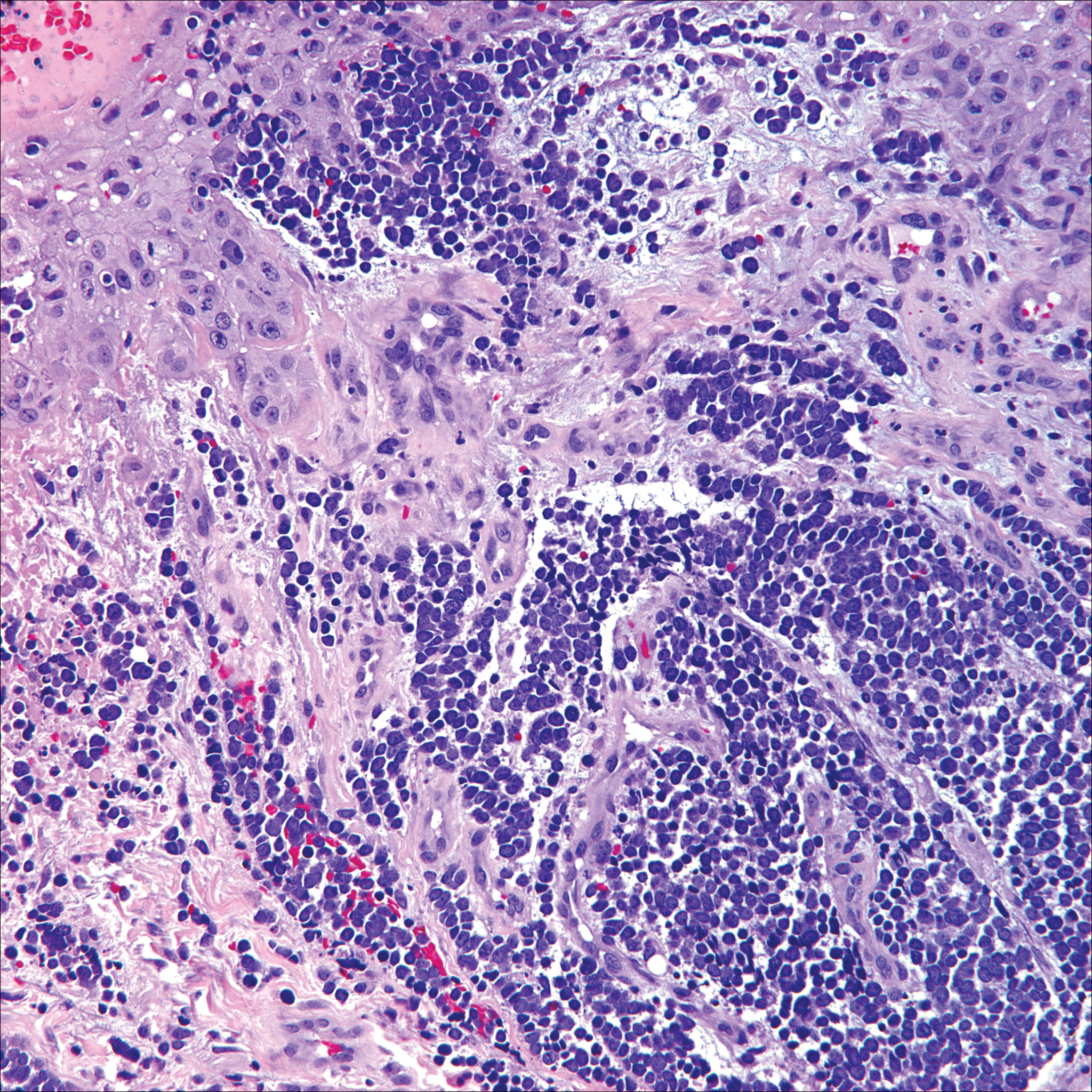

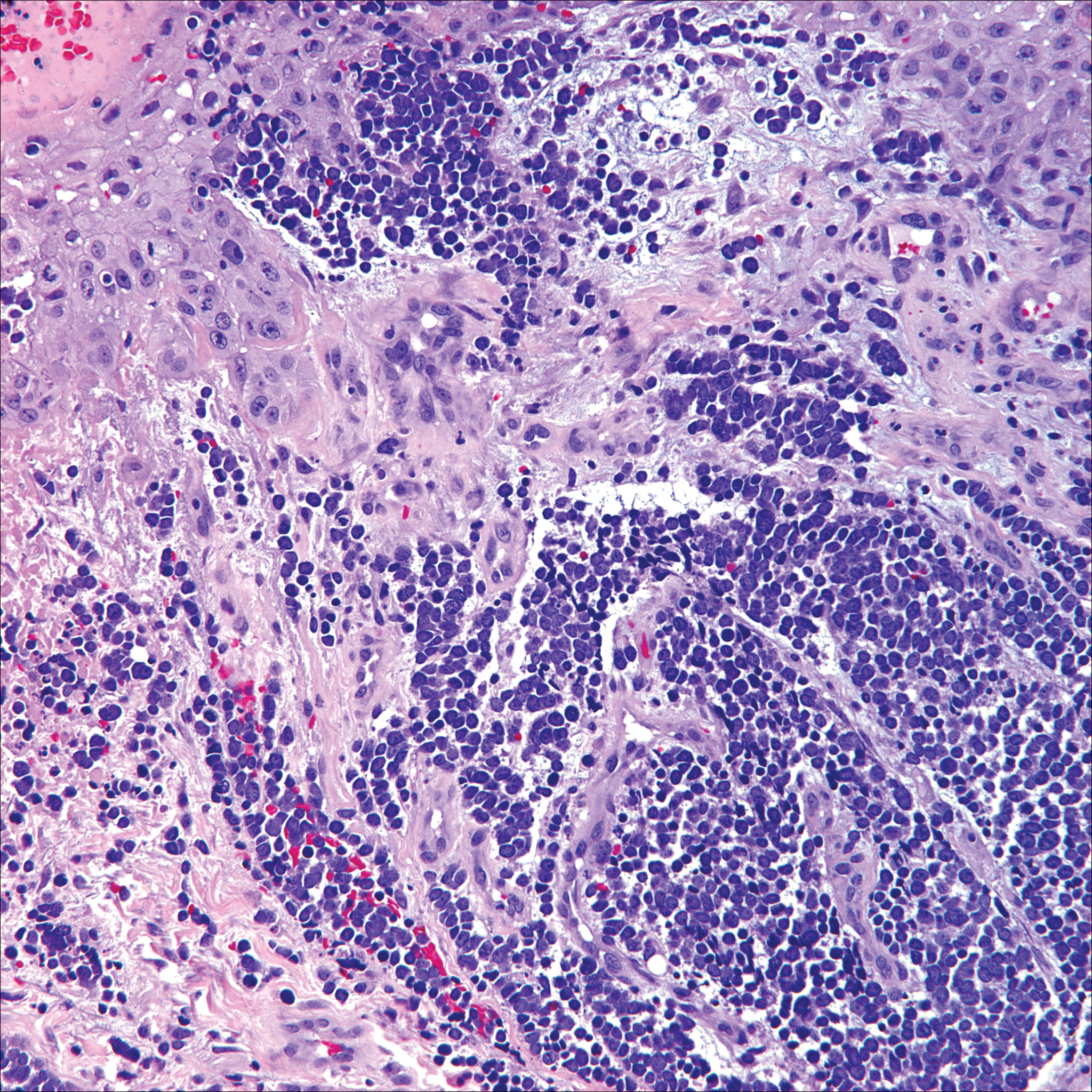

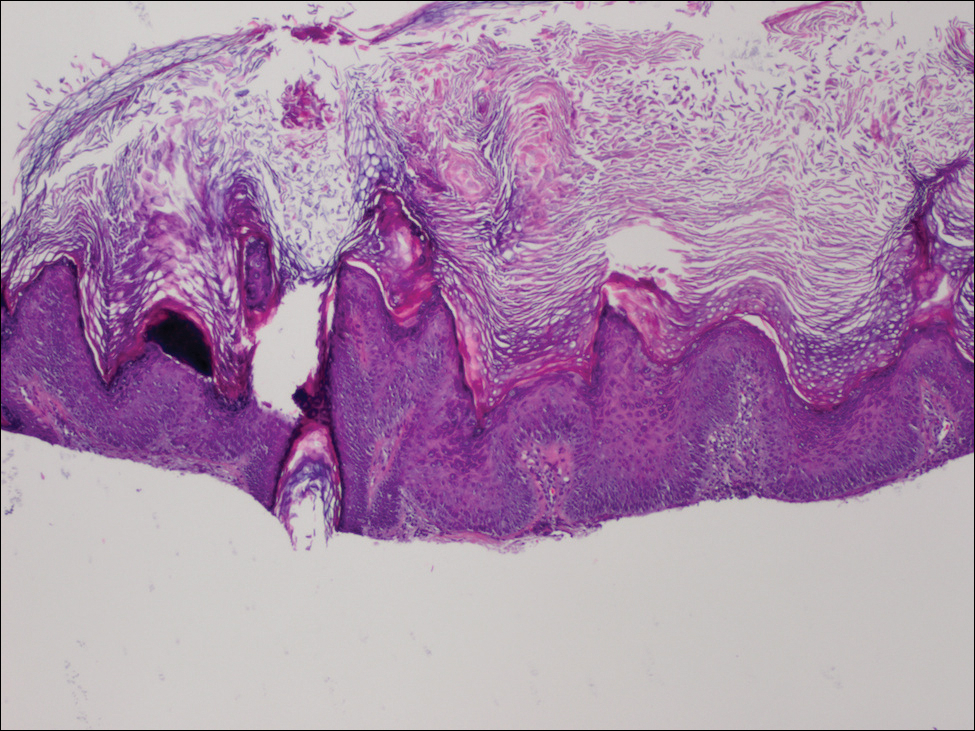

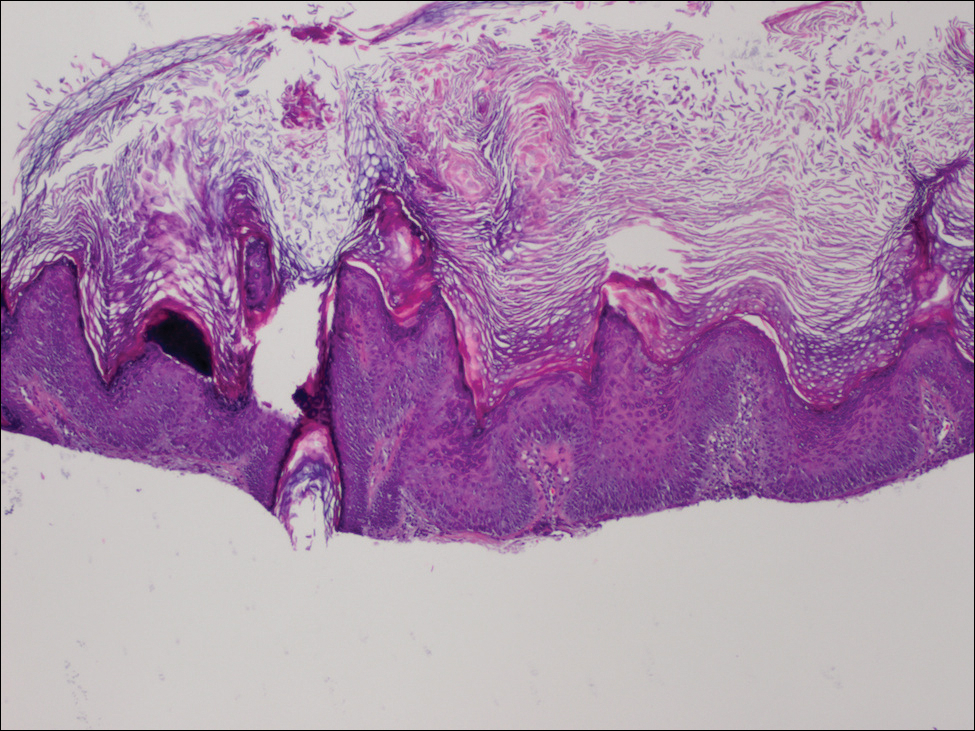

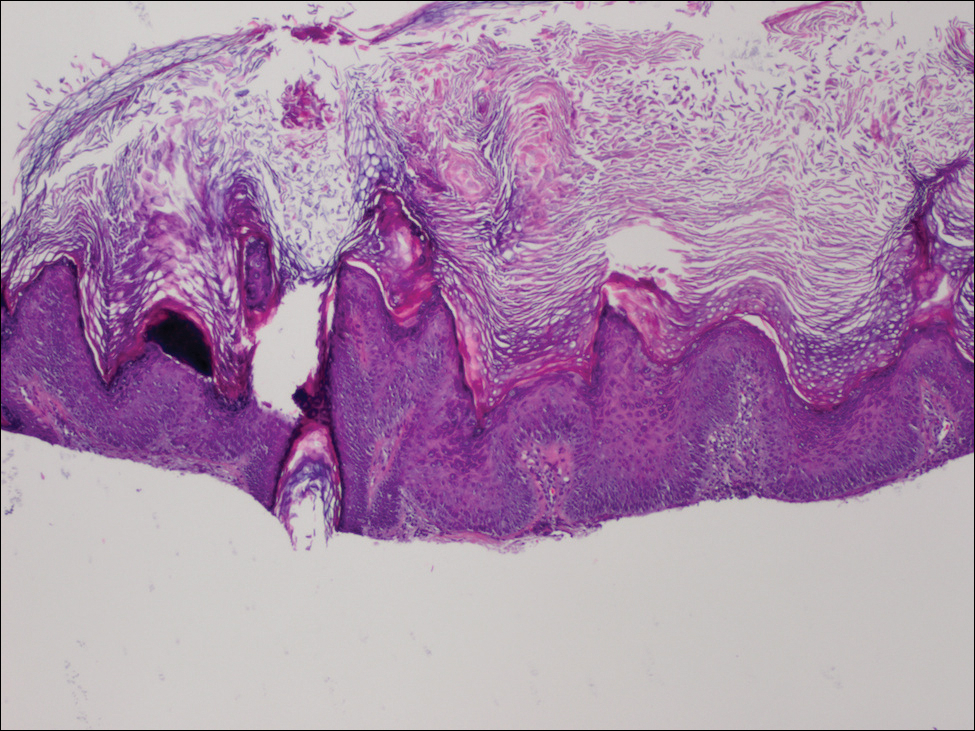

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

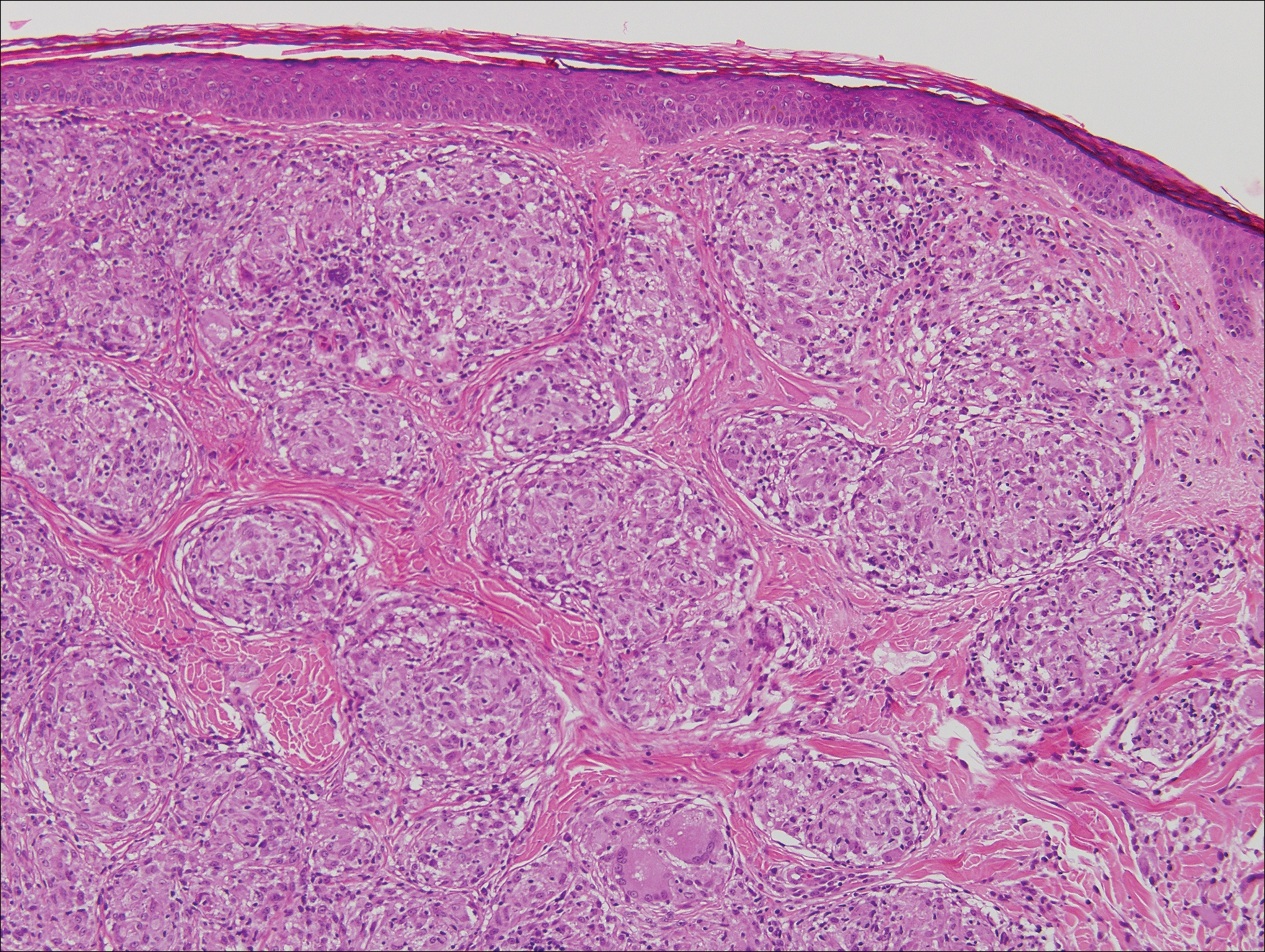

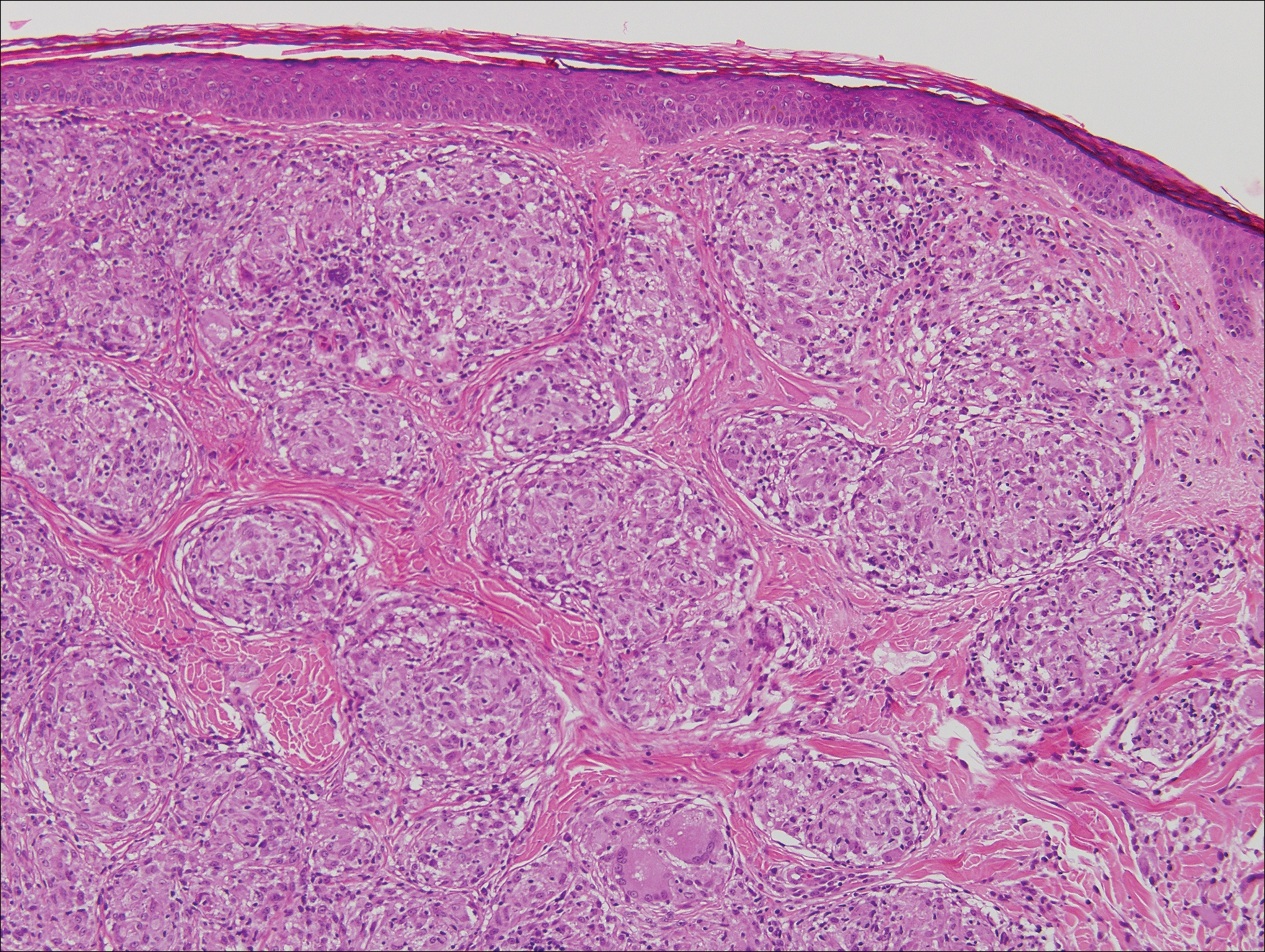

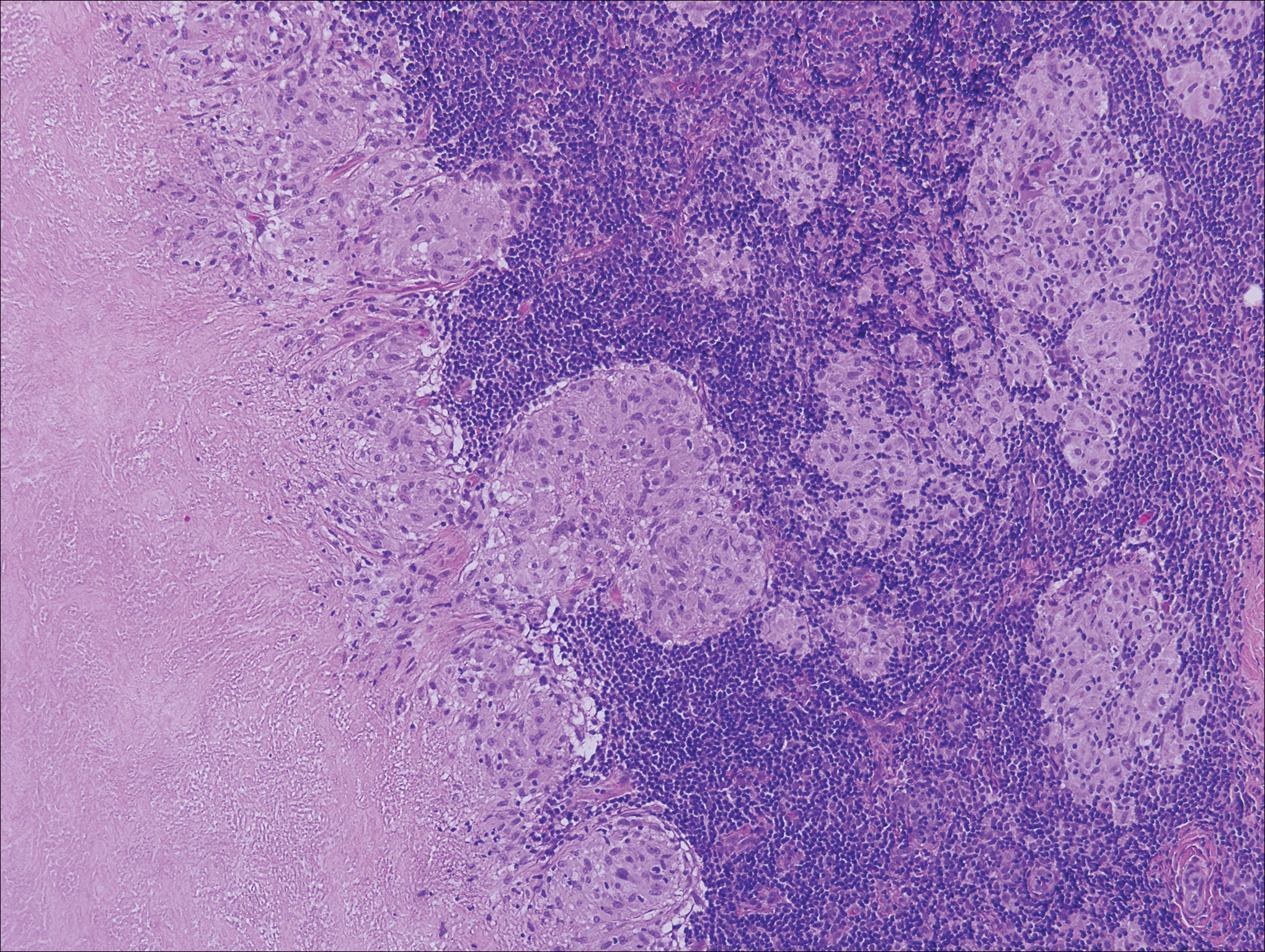

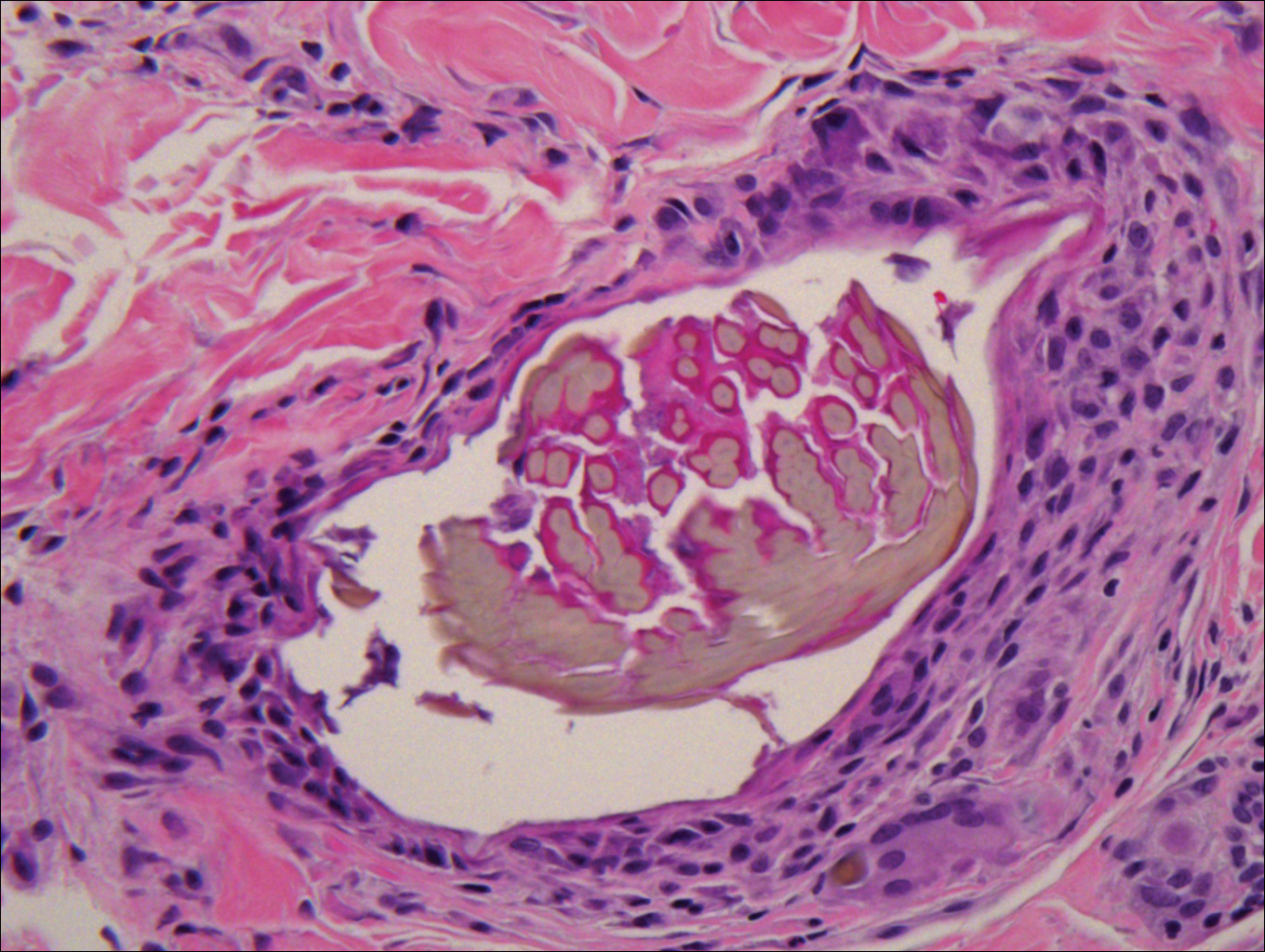

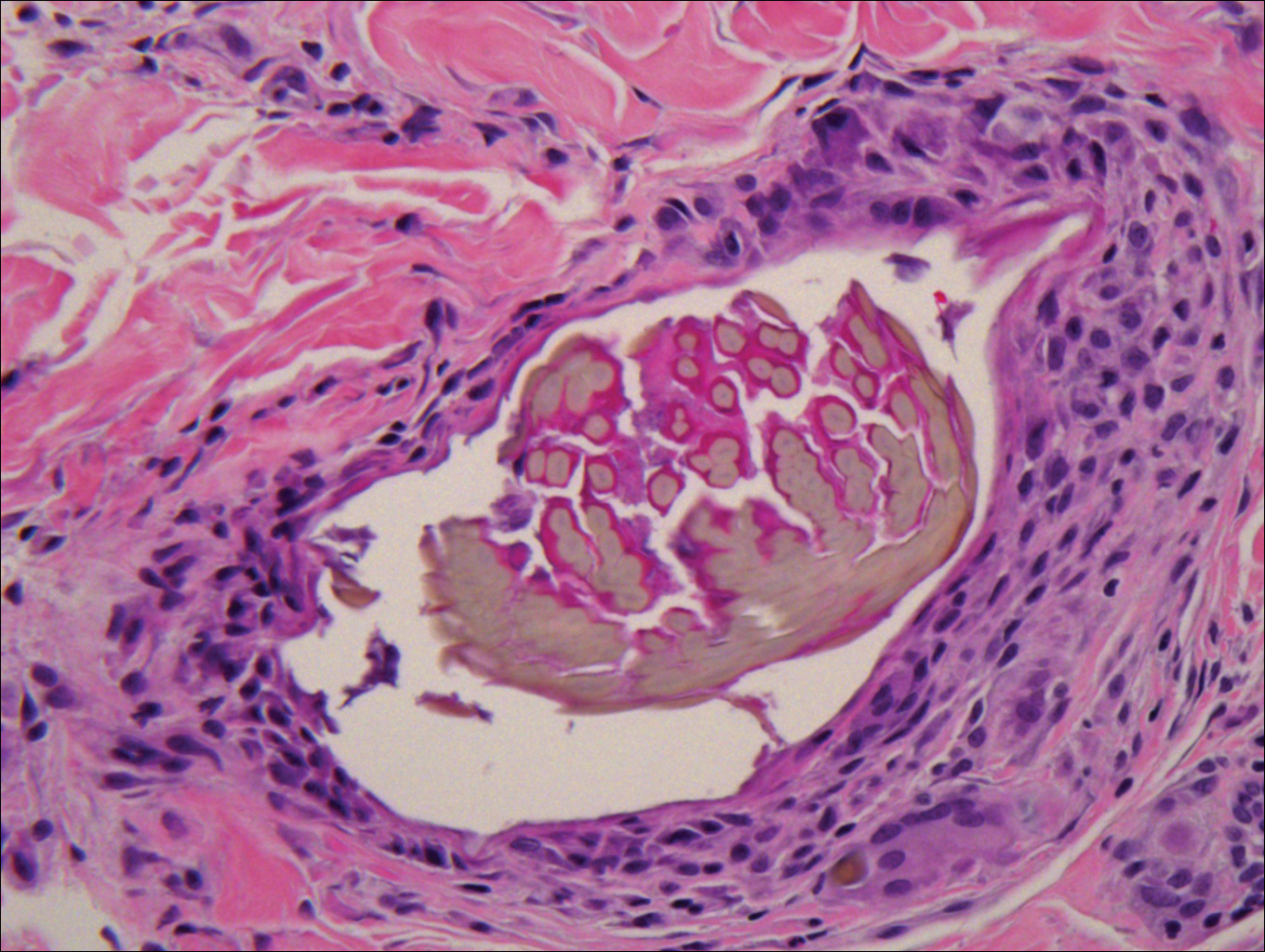

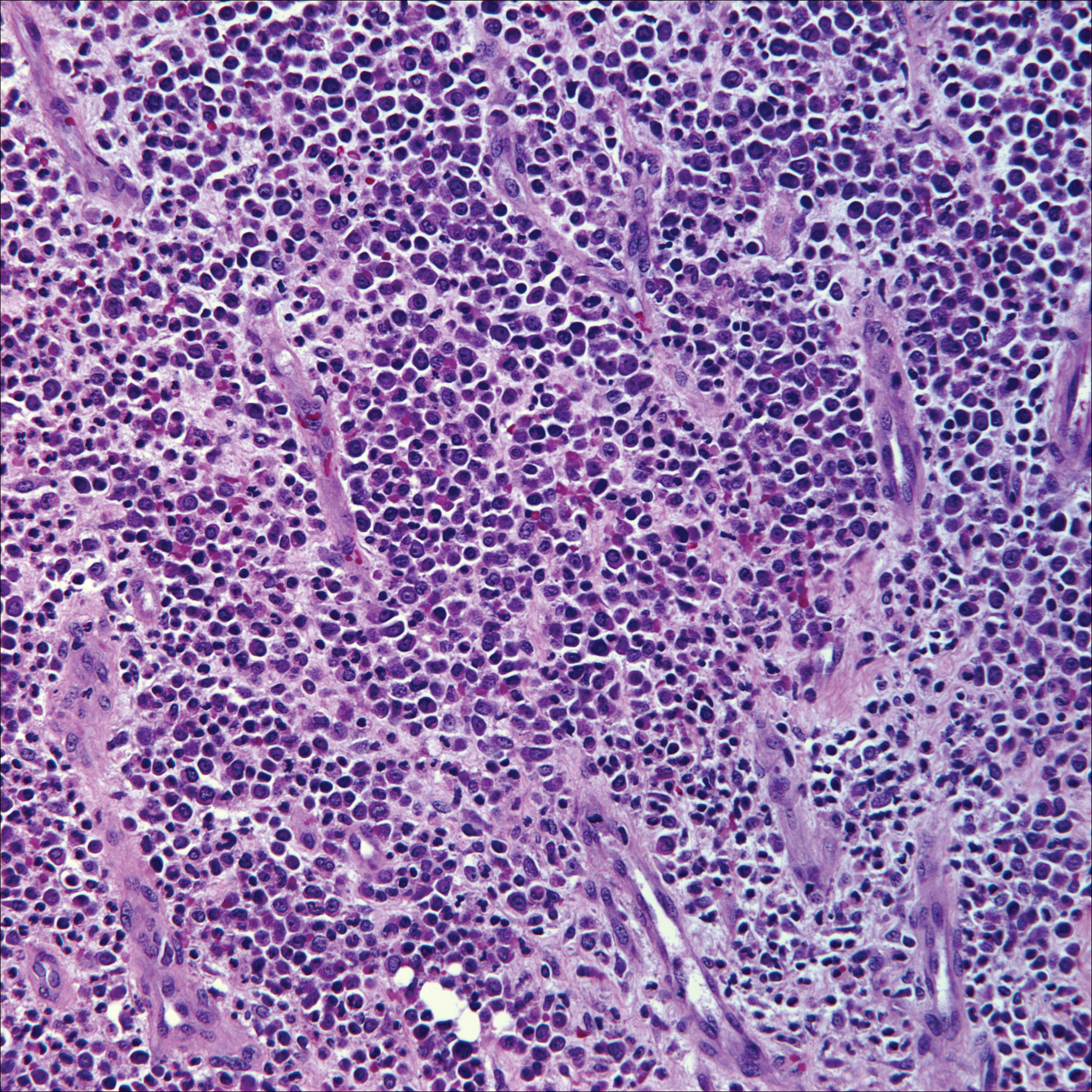

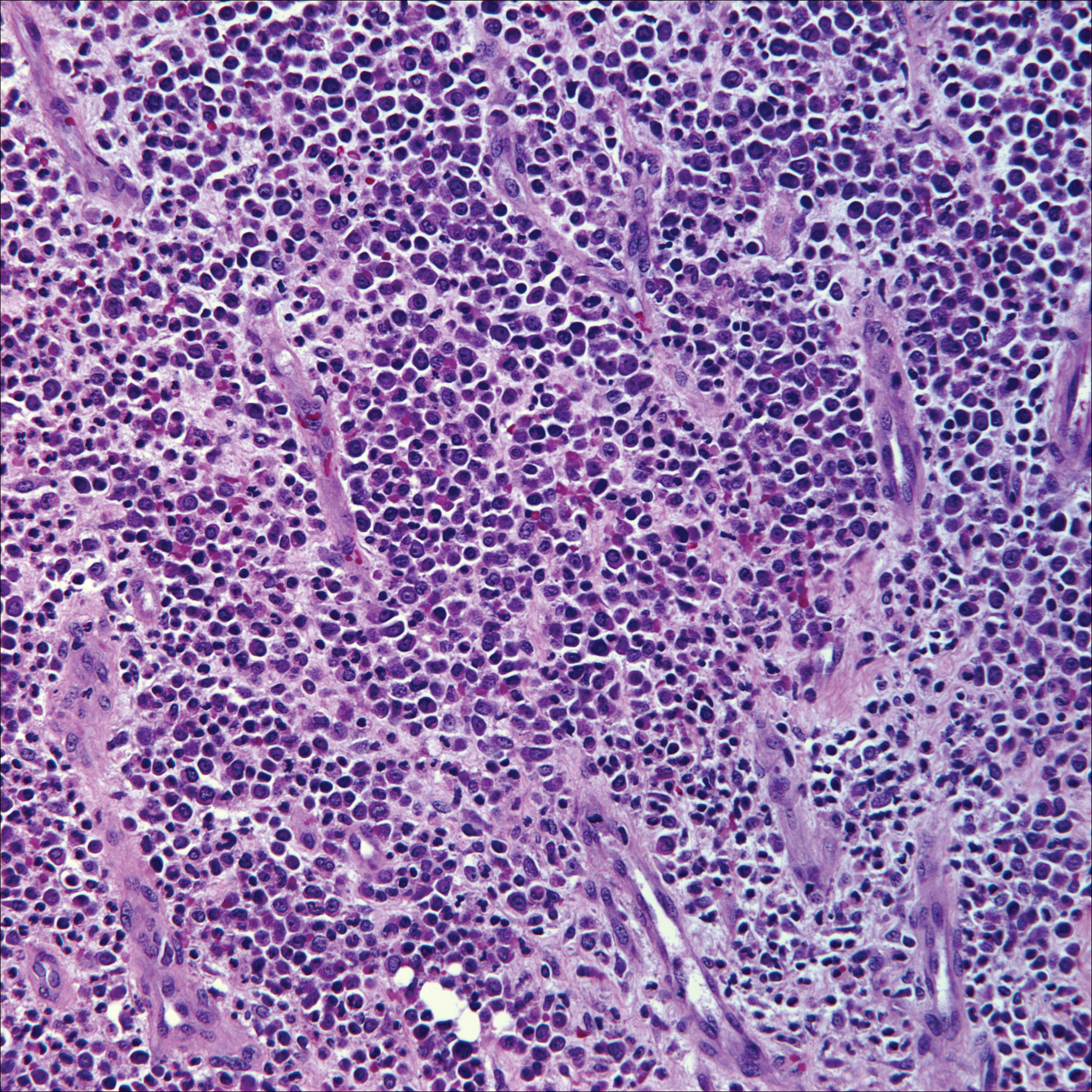

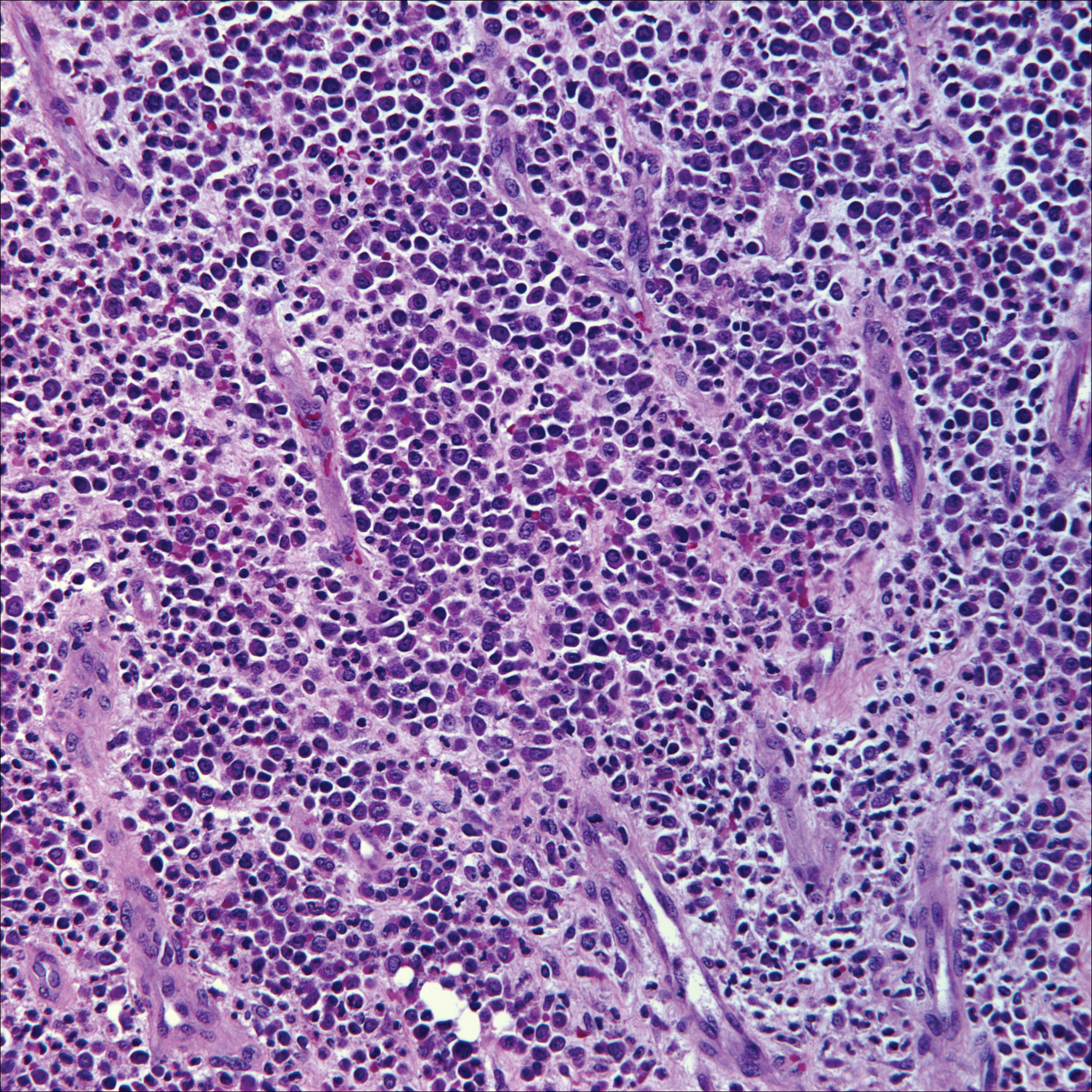

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

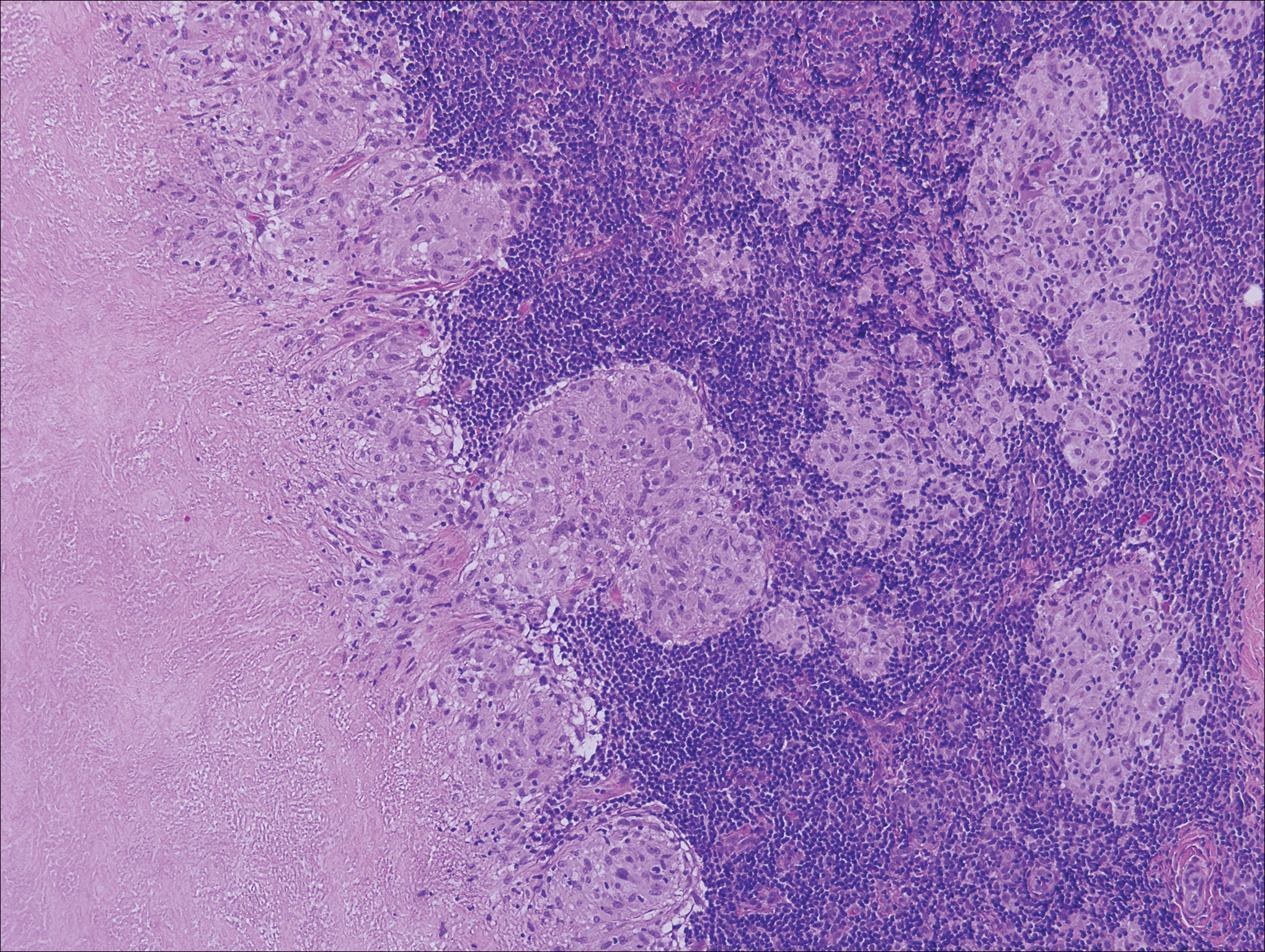

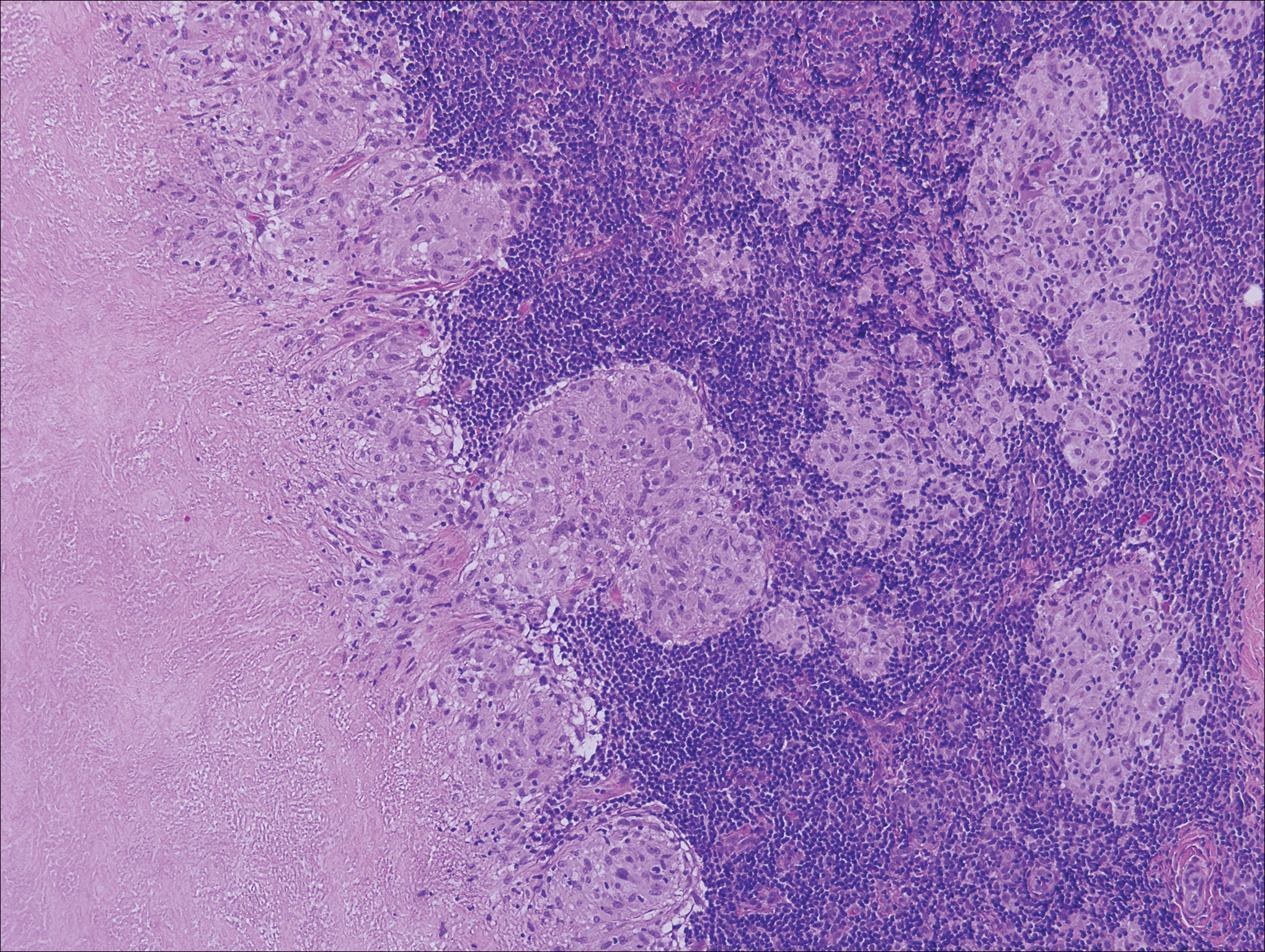

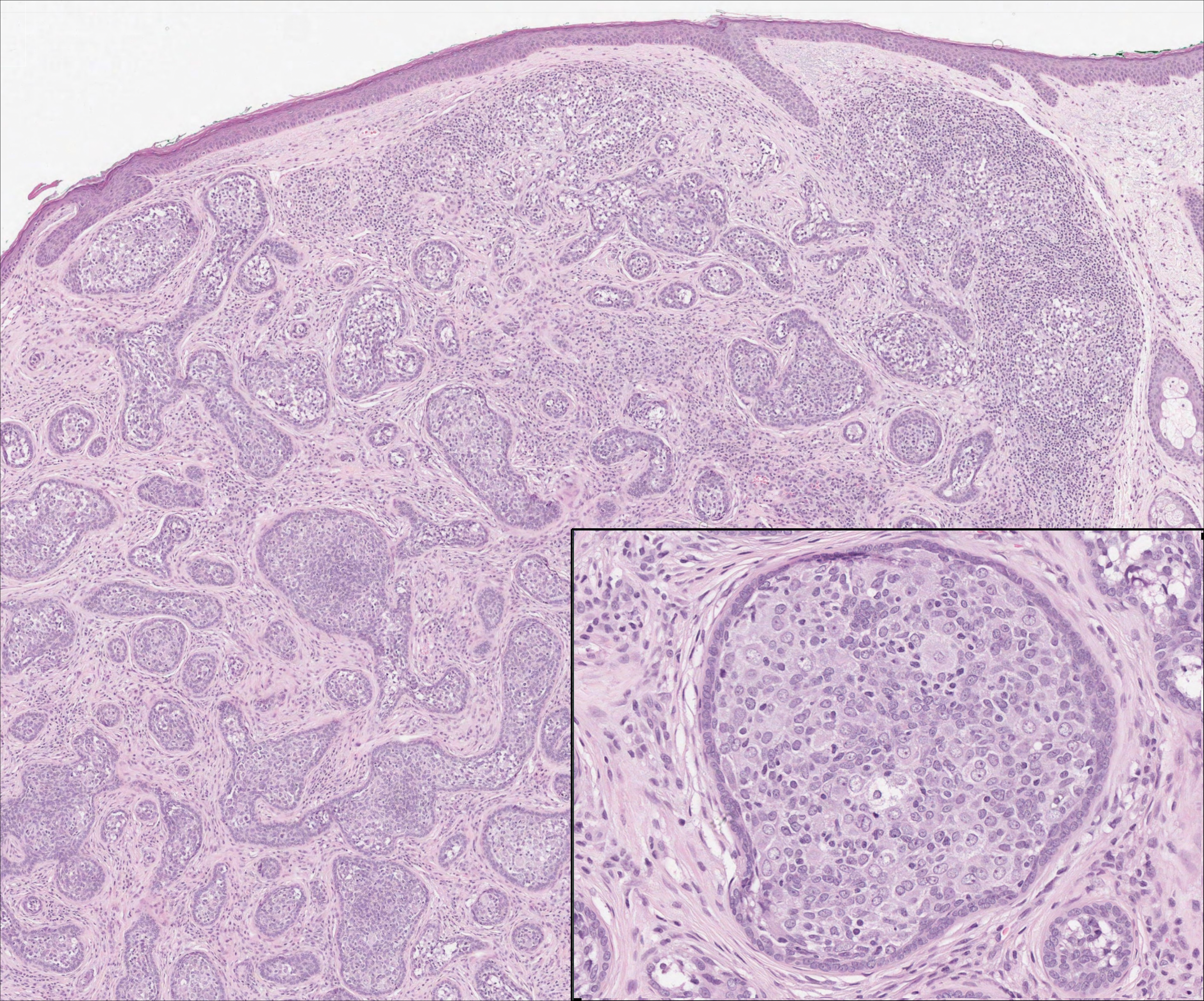

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

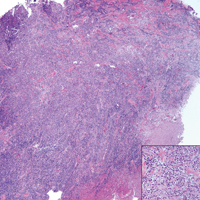

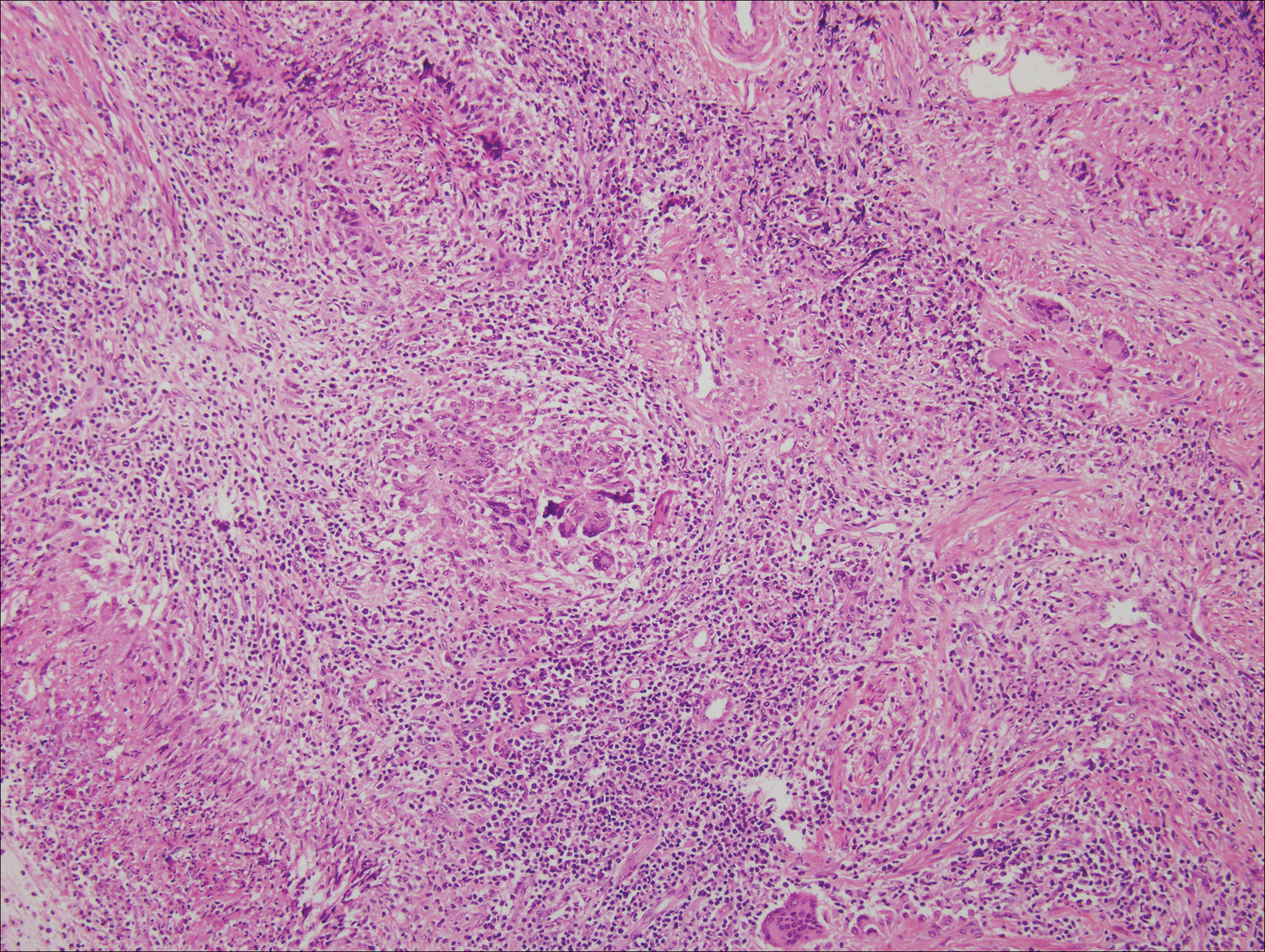

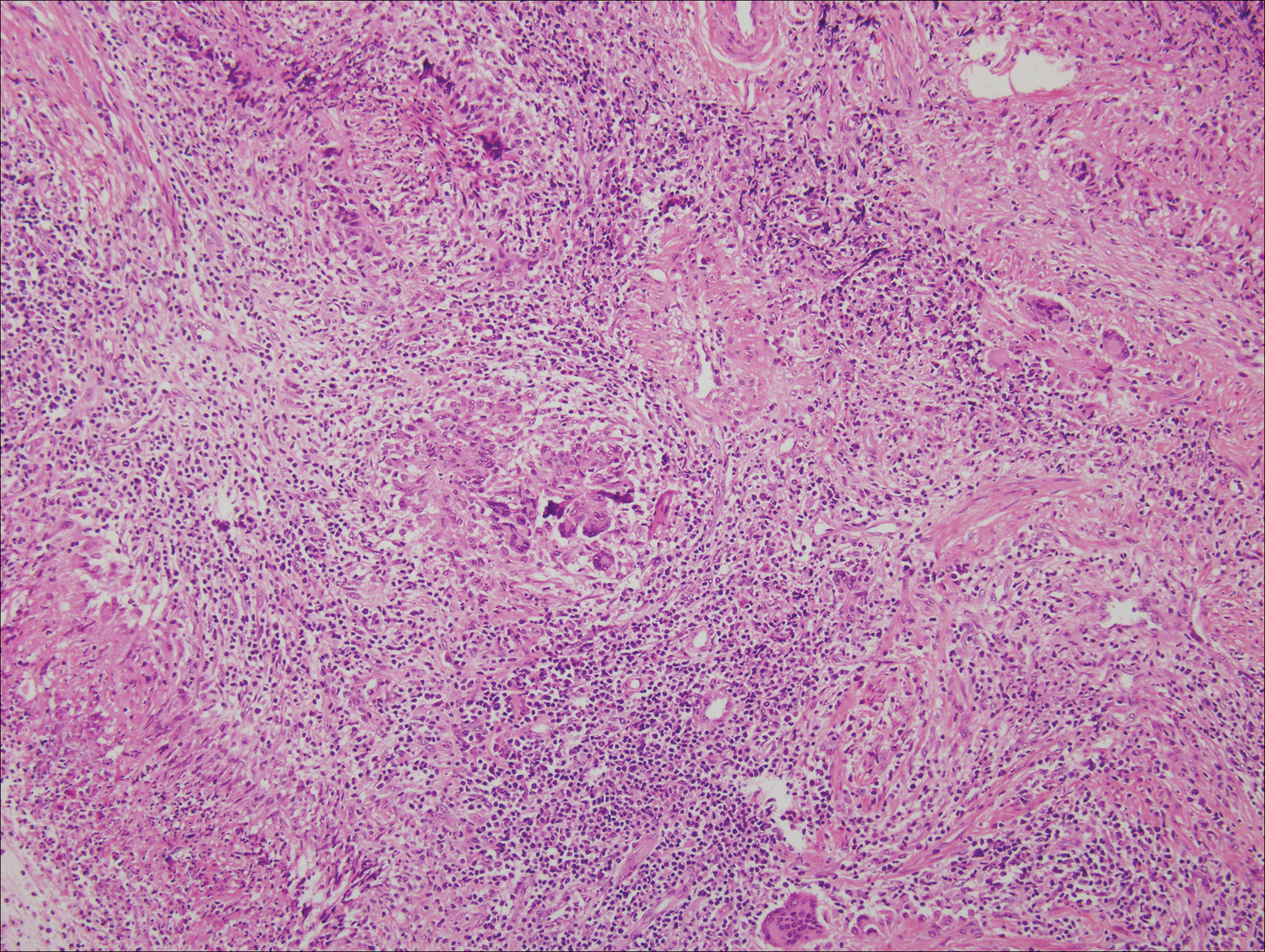

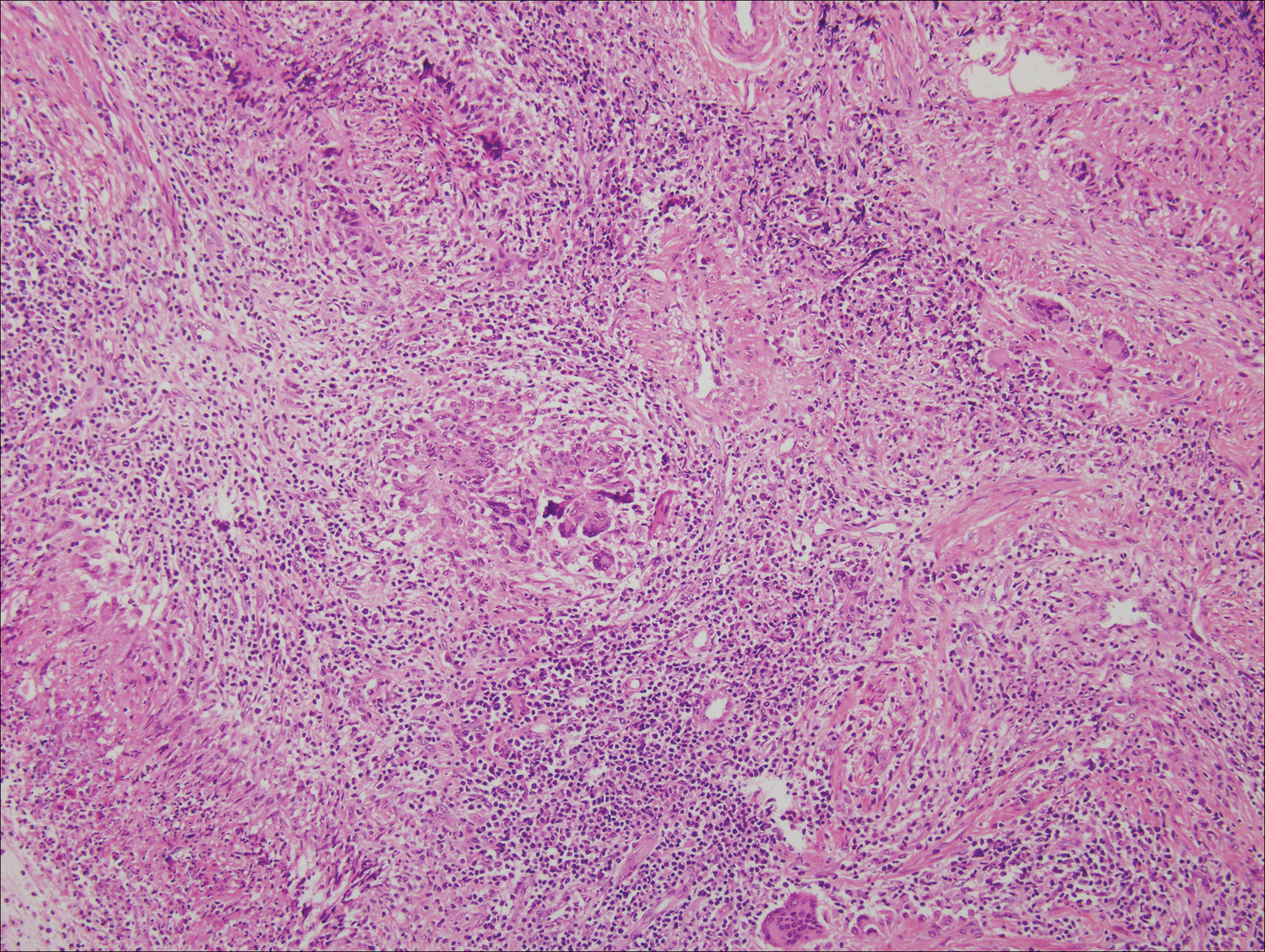

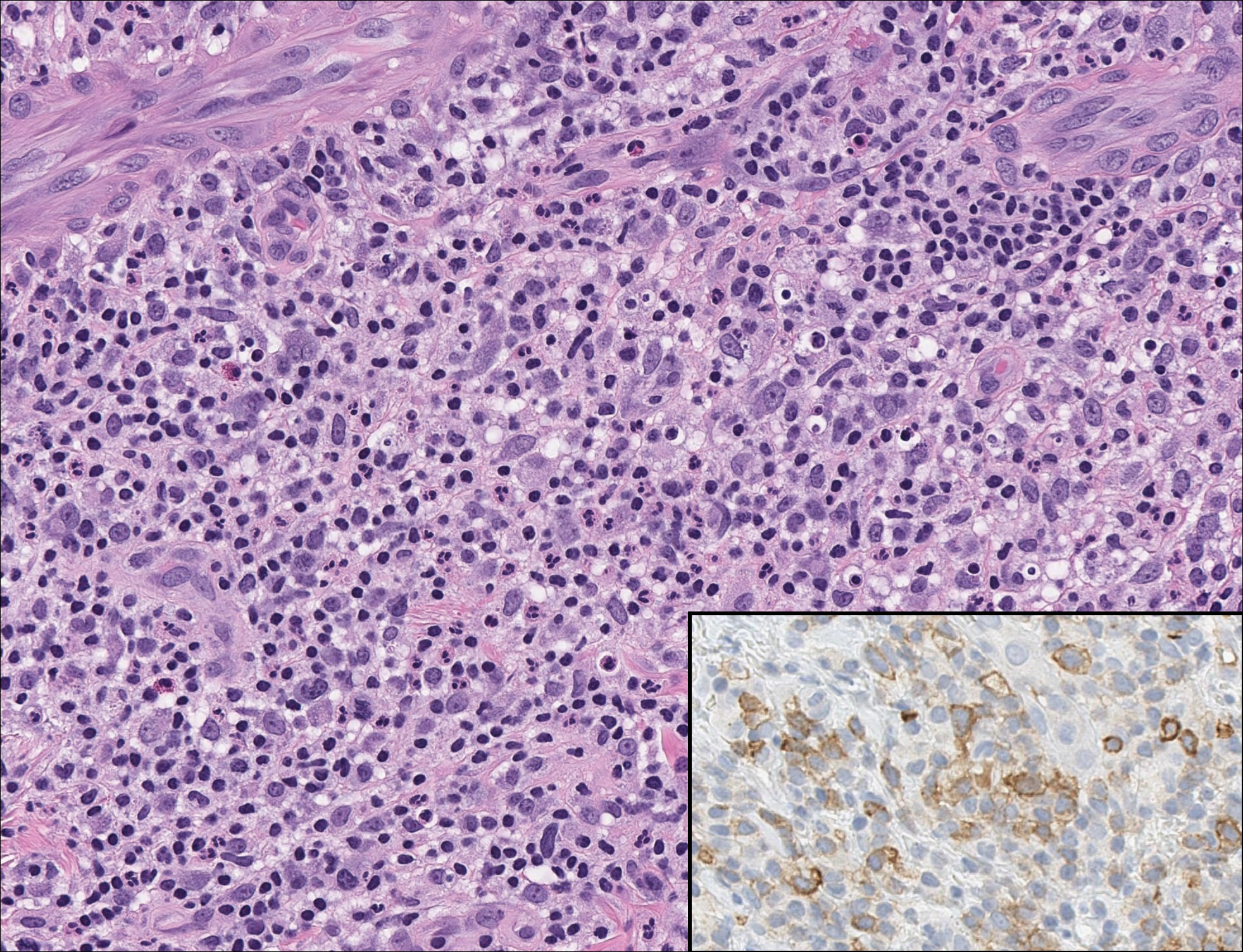

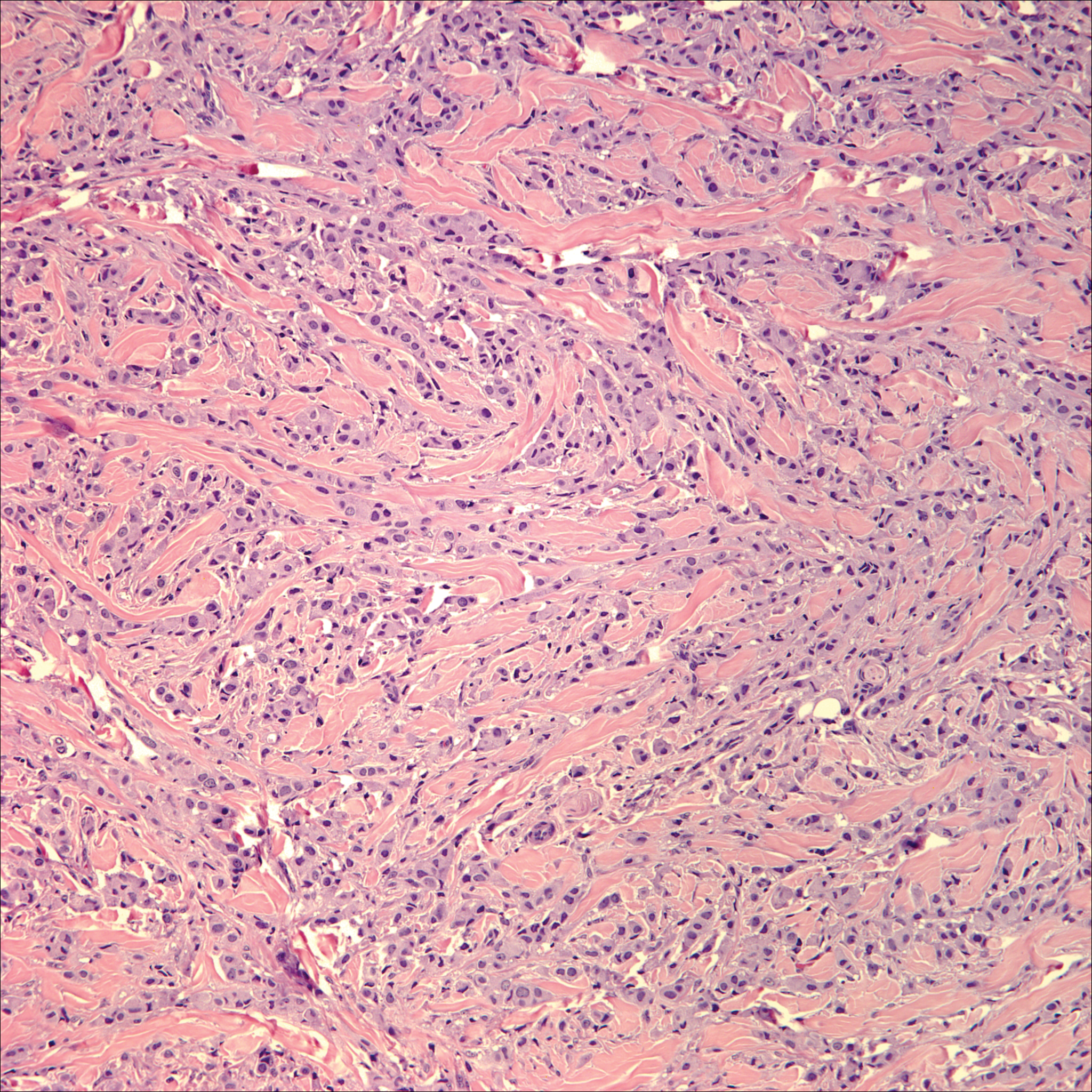

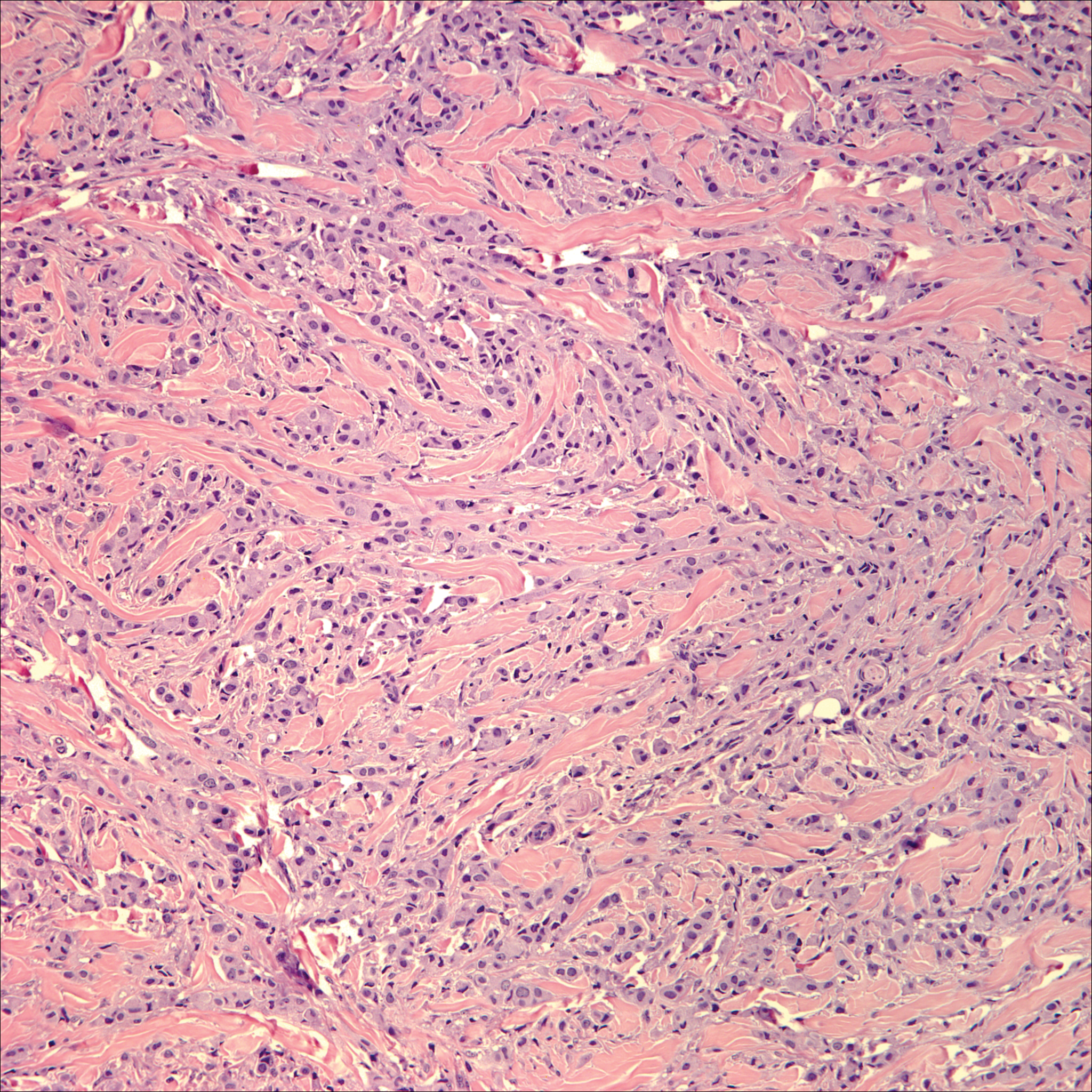

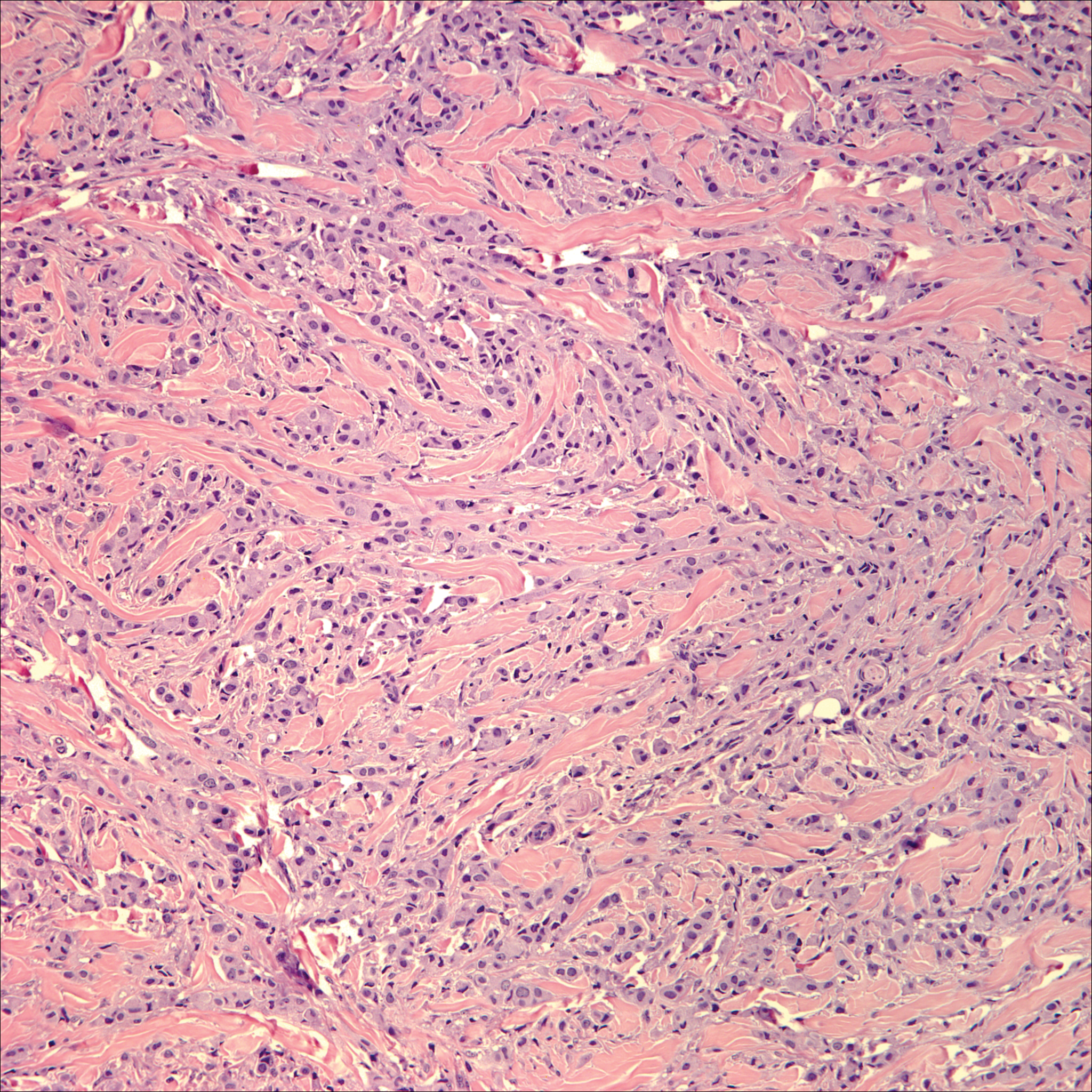

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

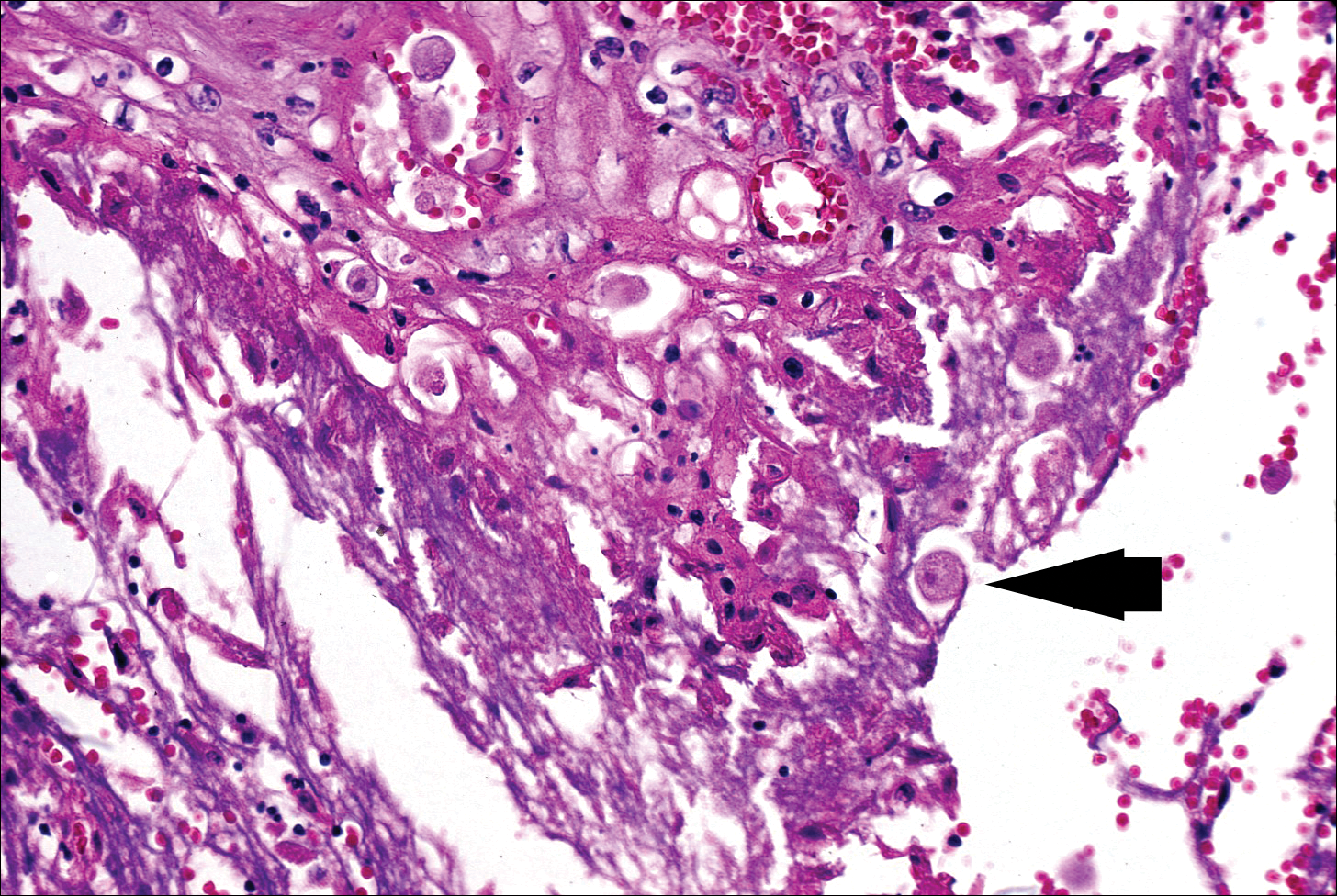

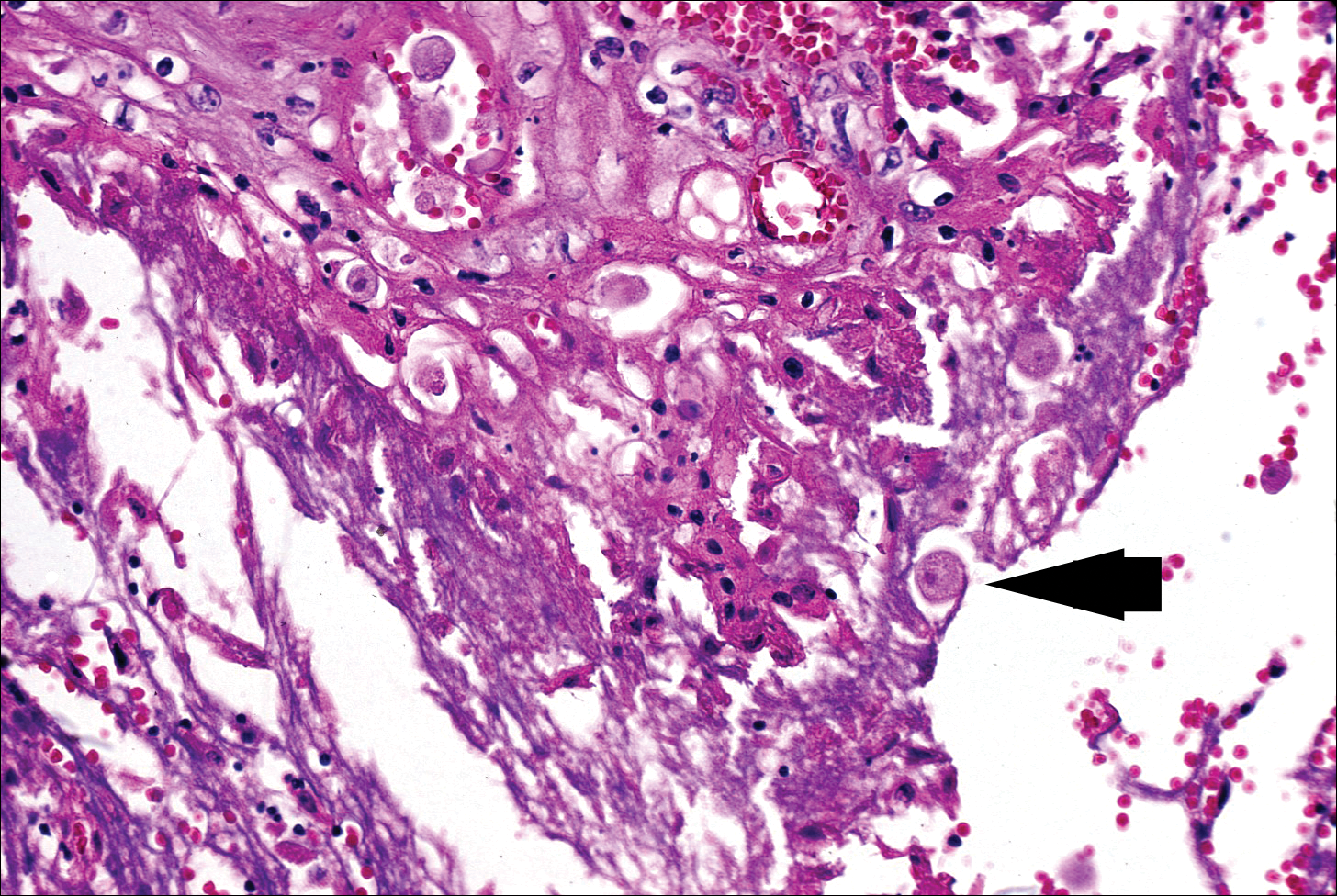

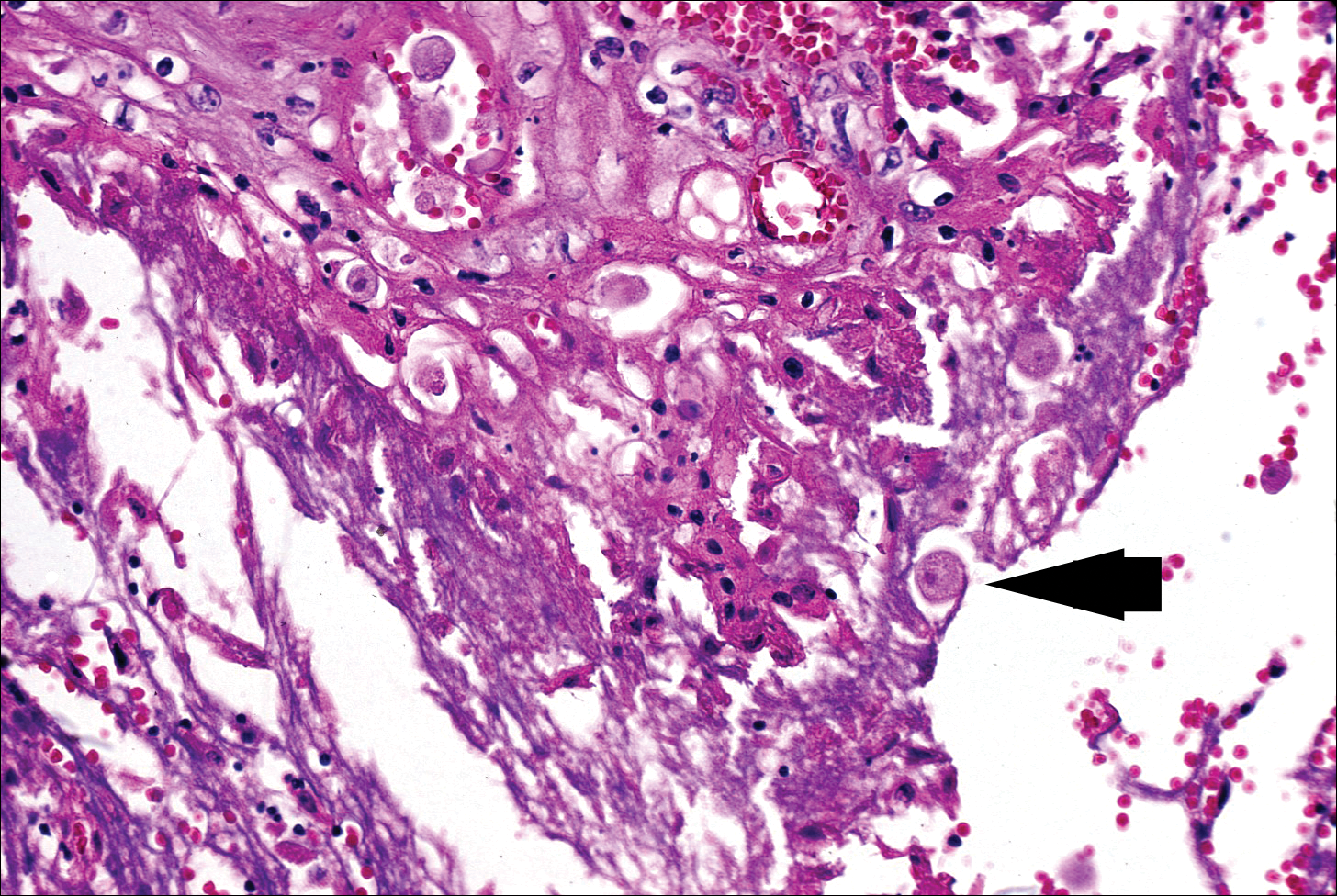

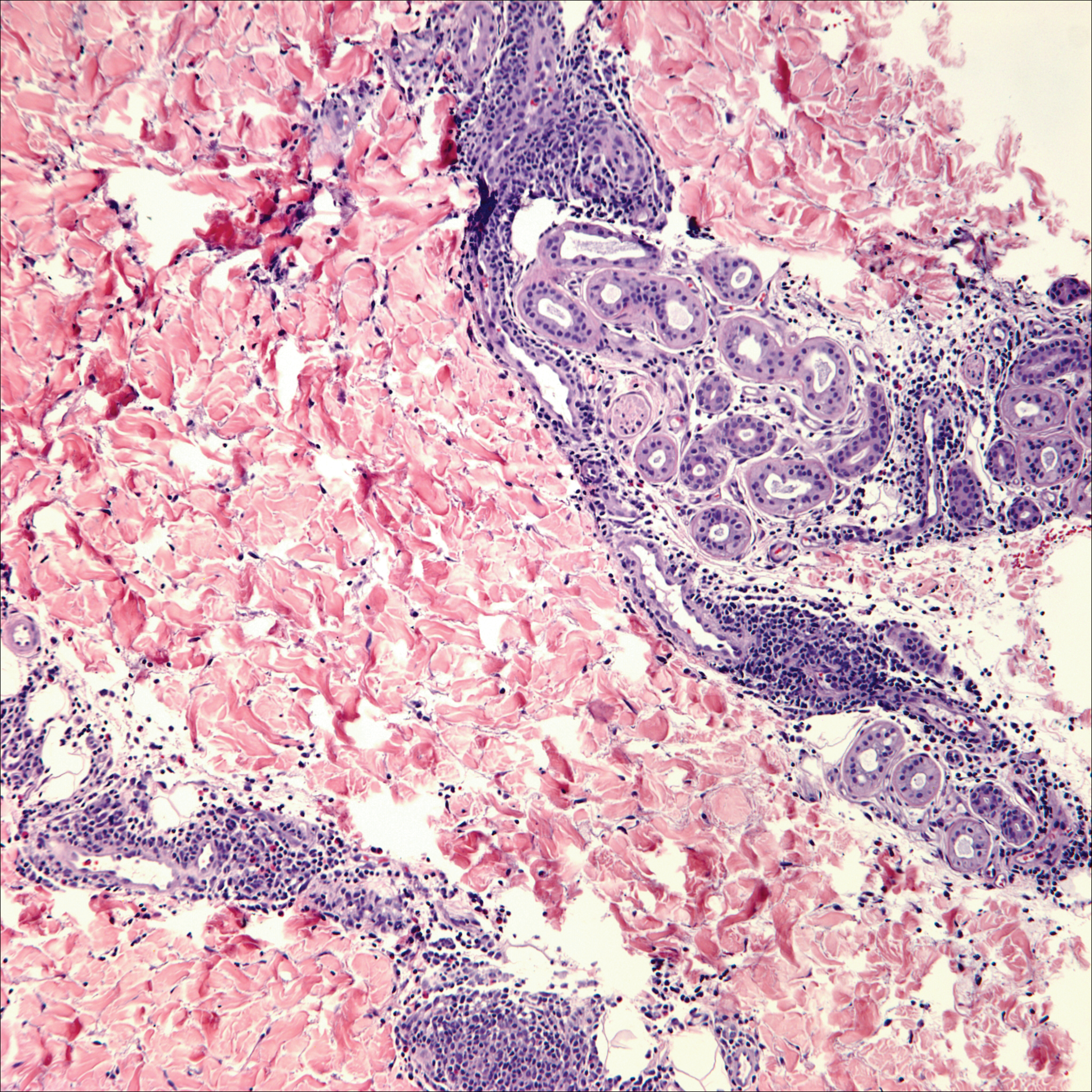

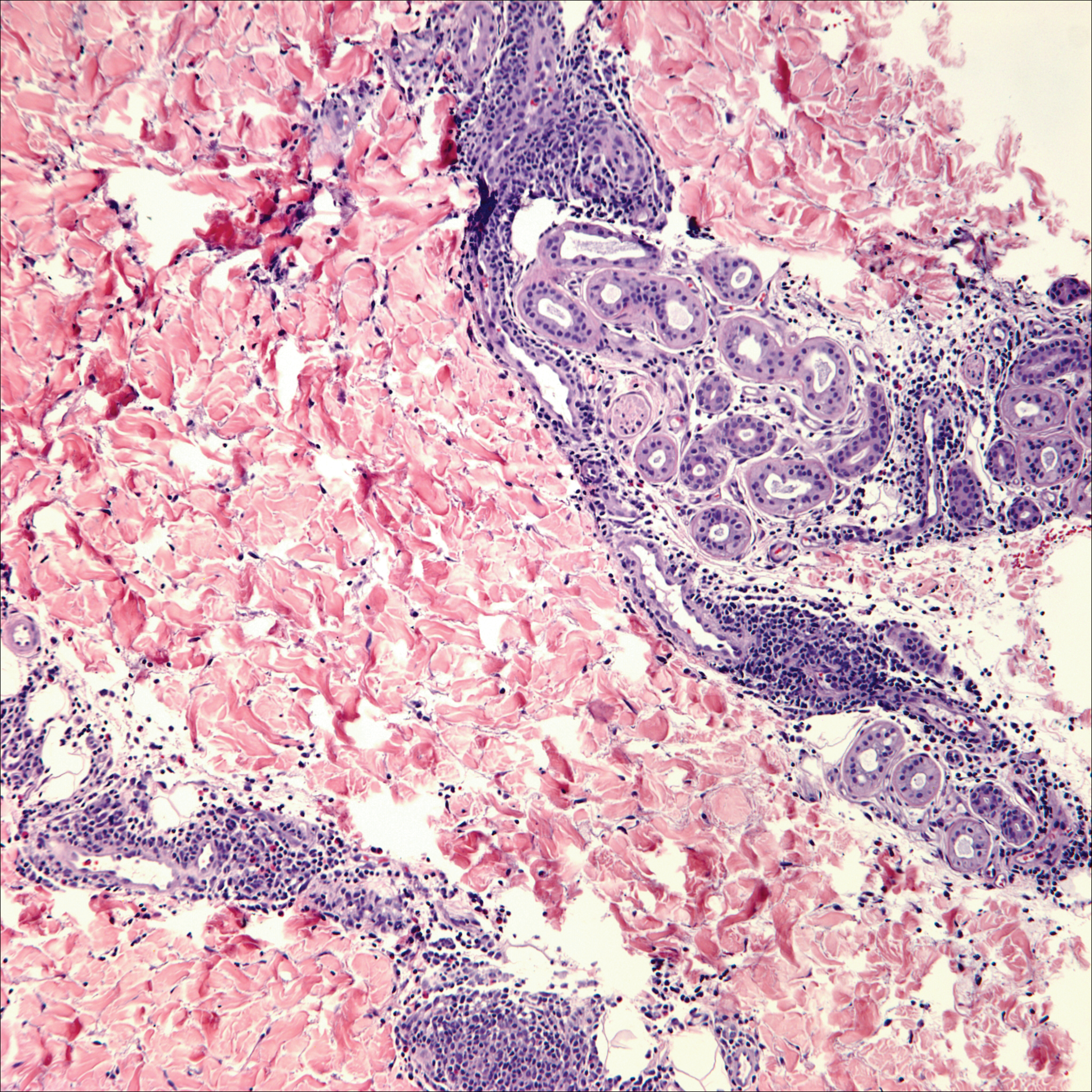

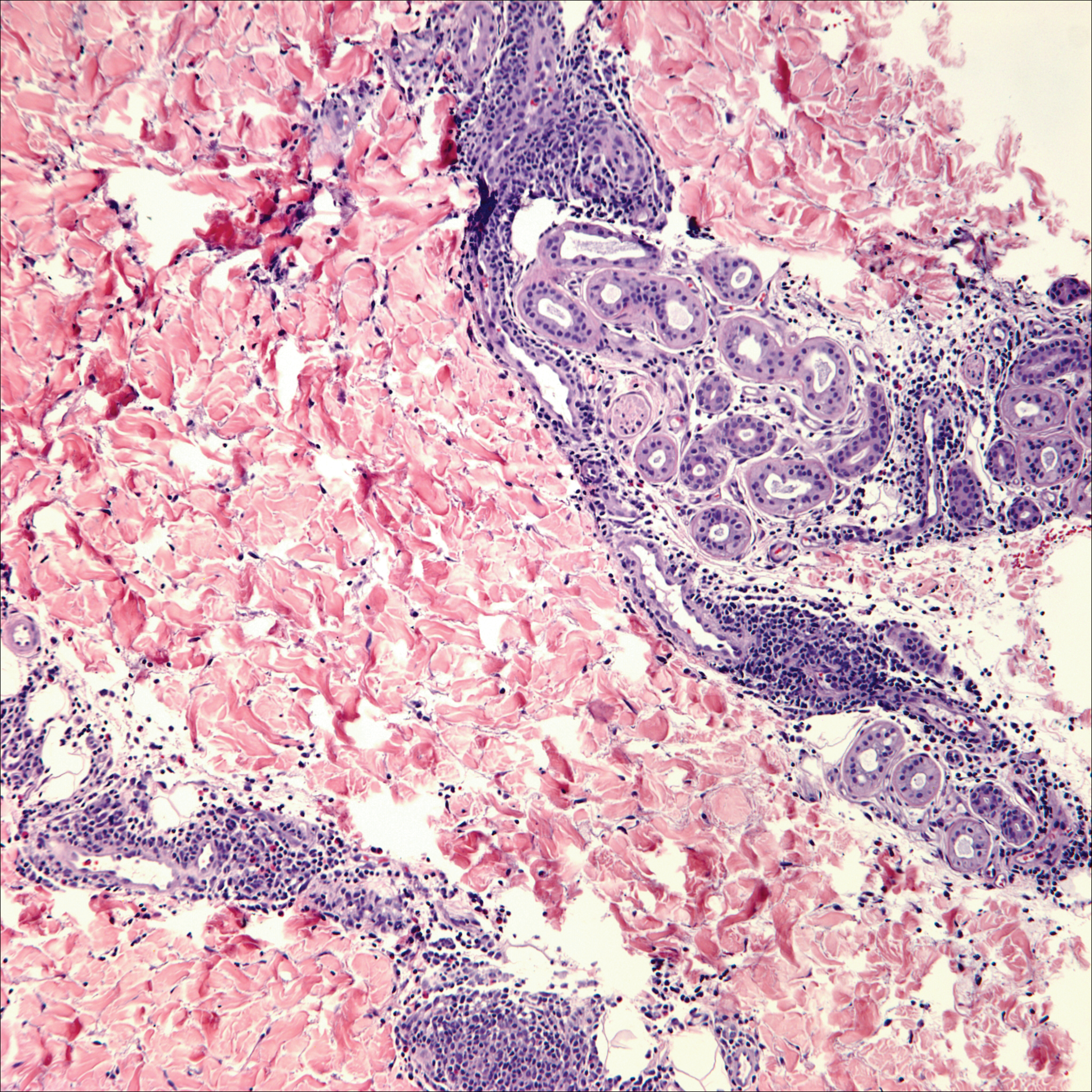

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

A 19-year-old man presented with a perianal condyloma acuminatum-like plaque of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea.

Disseminated Vesicles and Necrotic Papules

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

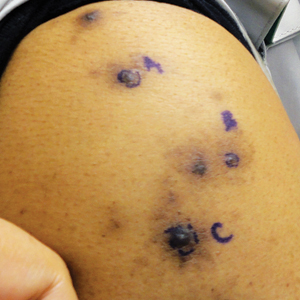

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

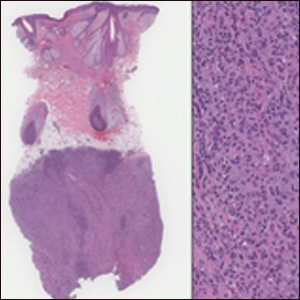

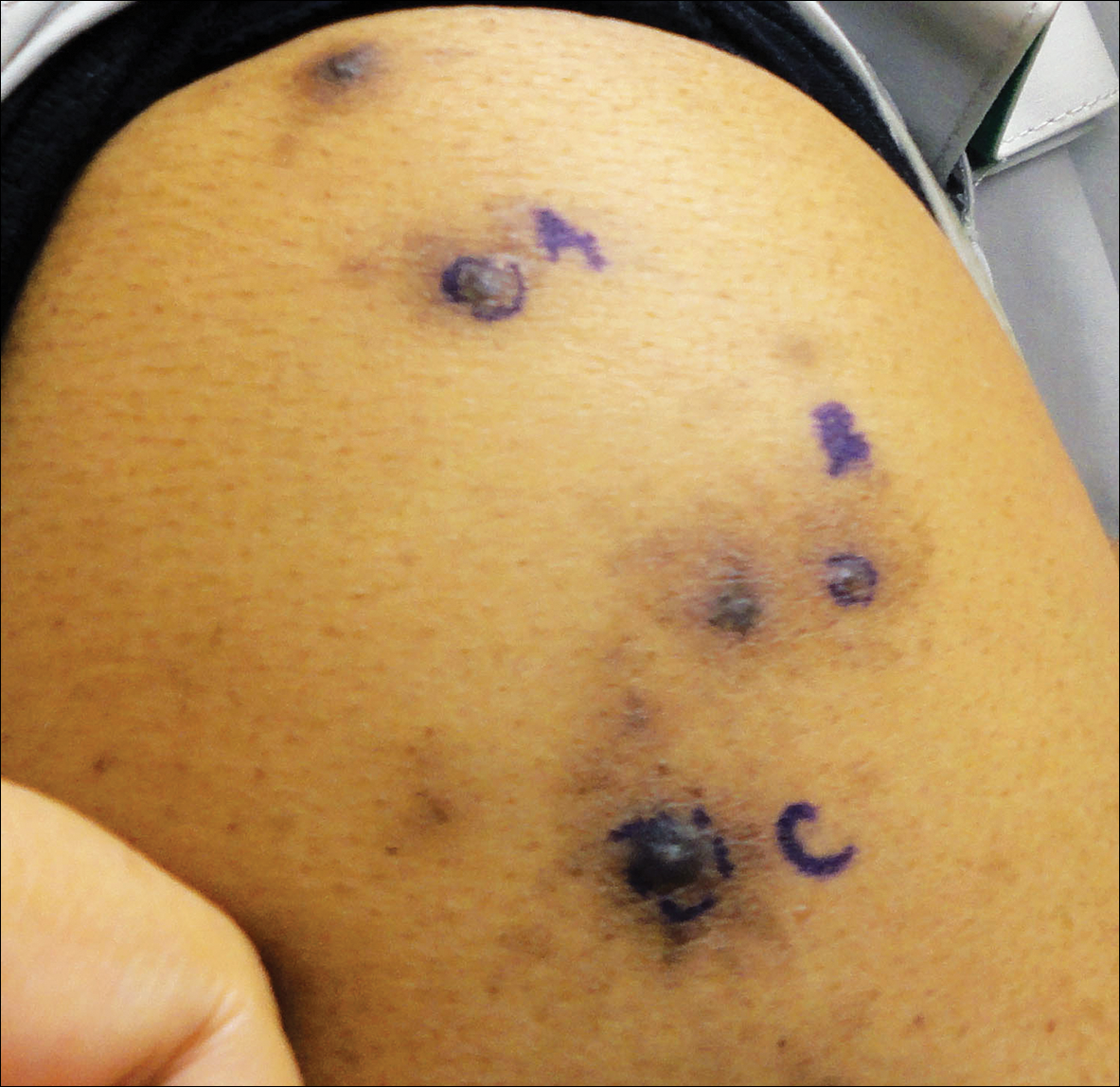

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

A 30-year-old man who had contracted human immunodeficiency virus from a male sexual partner 4 years prior presented to the emergency department with fevers, chills, night sweats, and rhinorrhea of 2 weeks' duration. He reported that he had been off highly active antiretroviral therapy for 2 years. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, papulonecrotic, crusted lesions on the face, neck, chest, back, arms, and legs that had developed over the past 4 days. Fluid-filled vesicles also were noted on the arms and legs, while erythematous, indurated nodules with overlying scaling were noted on the bilateral palms and soles. The patient reported that he had been vaccinated for varicella-zoster virus as a child without primary infection.

A Recalcitrant Case of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)

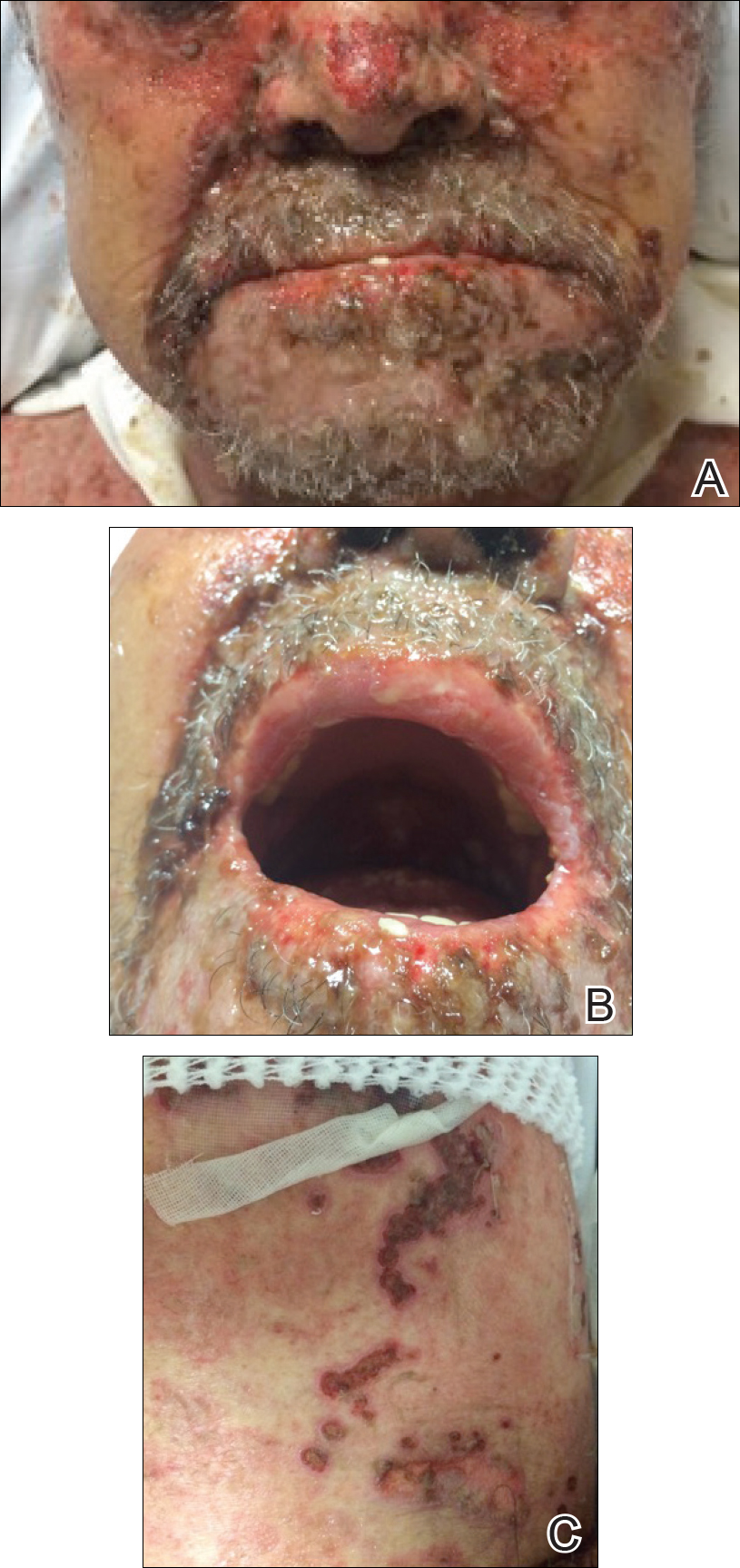

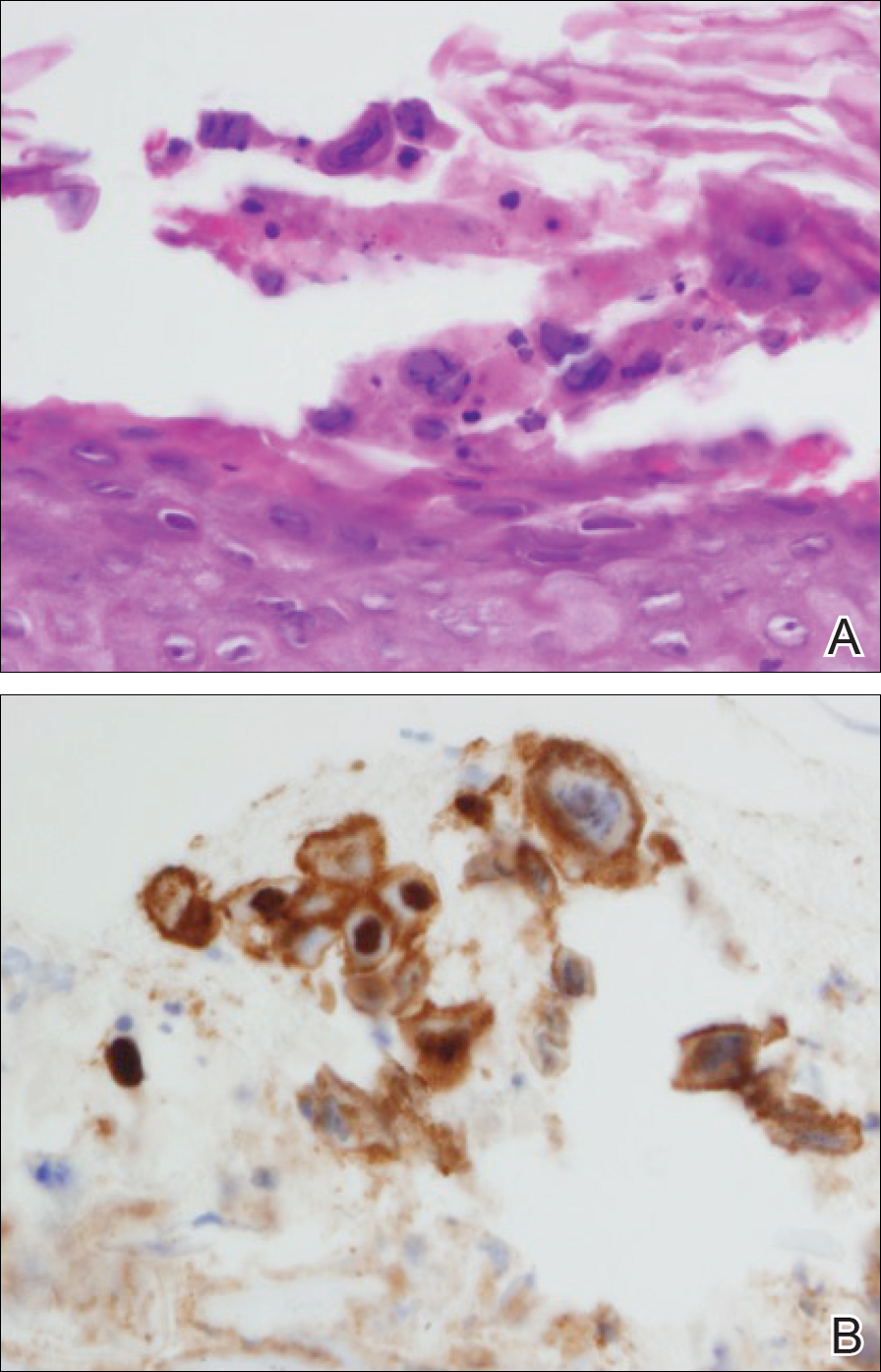

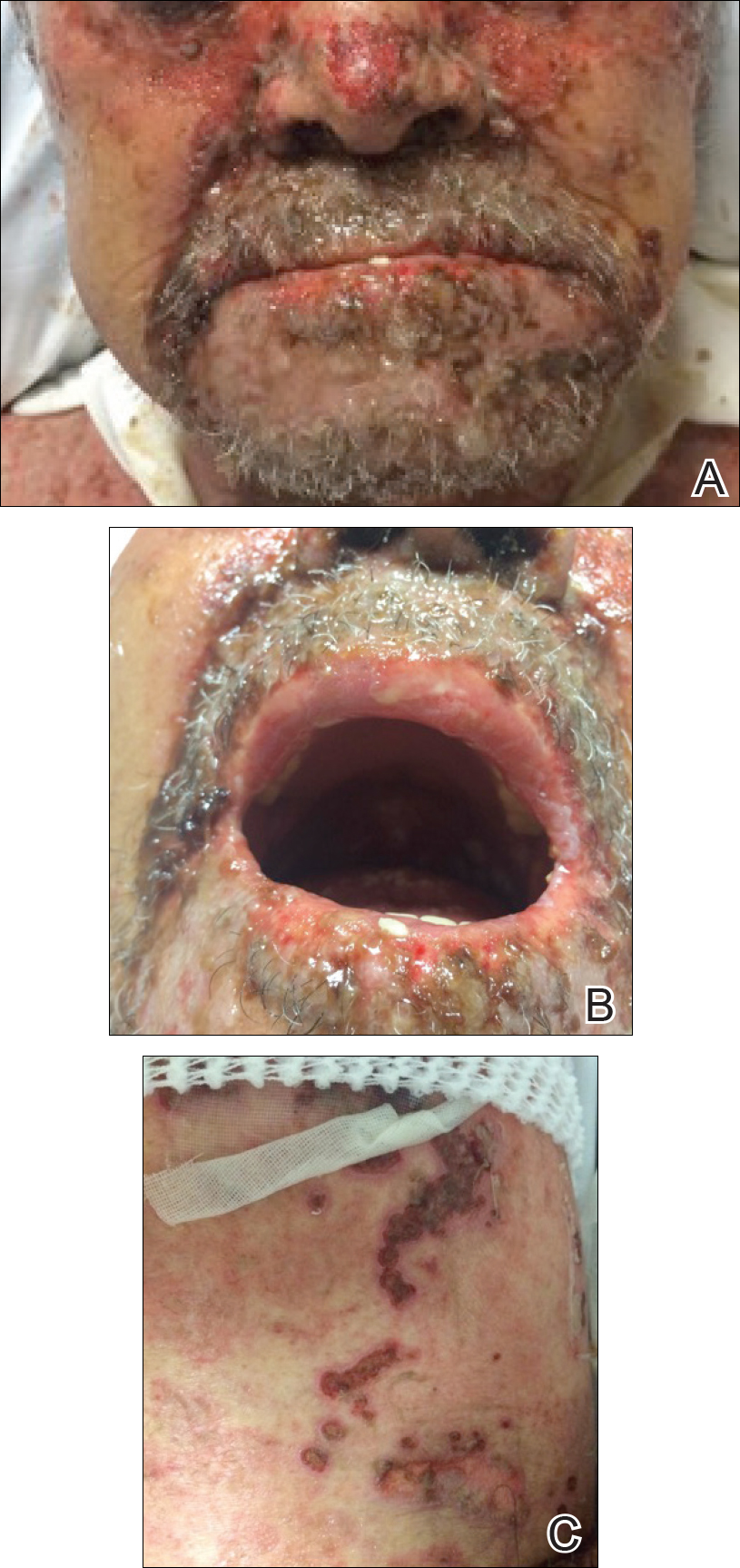

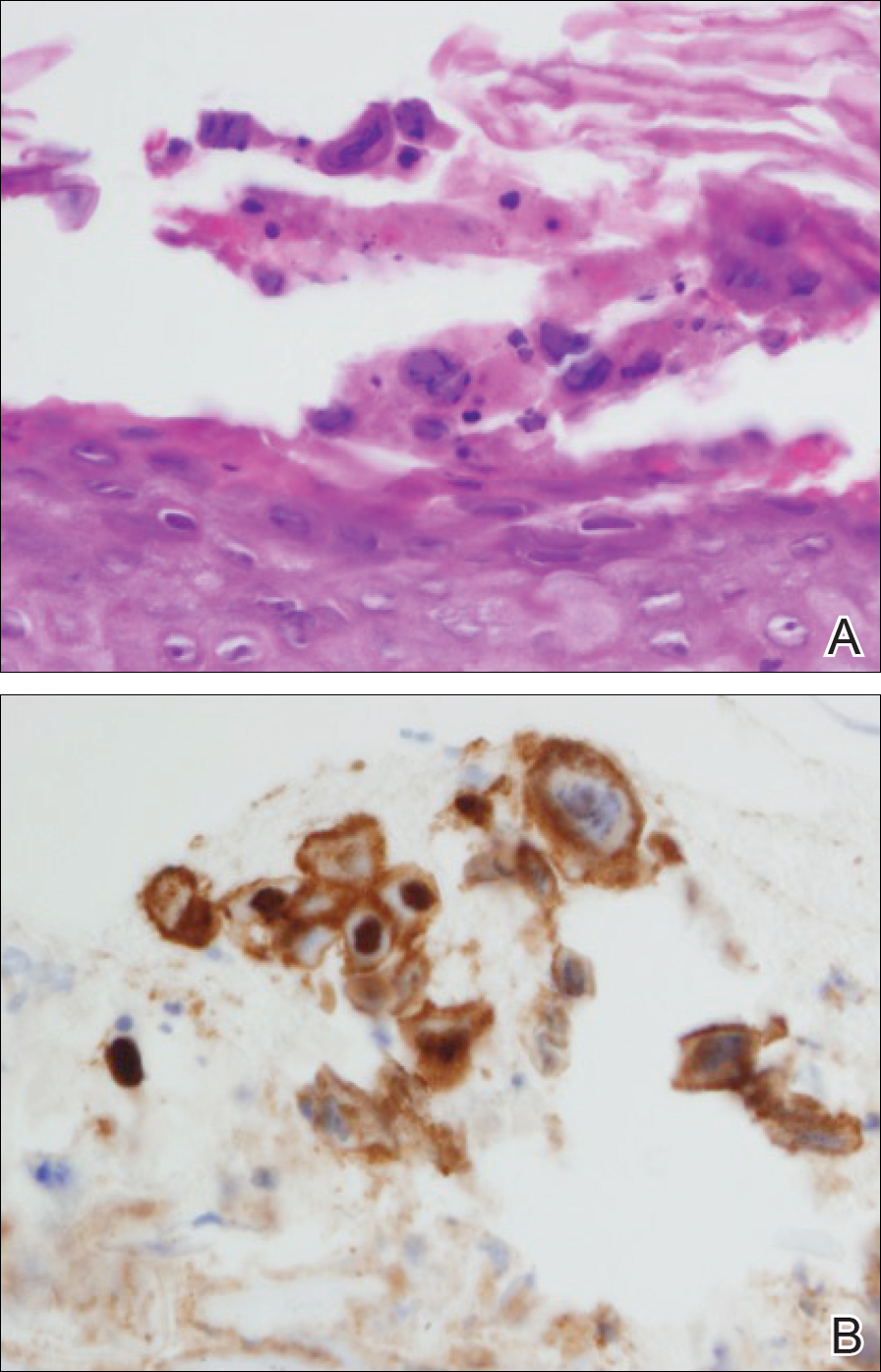

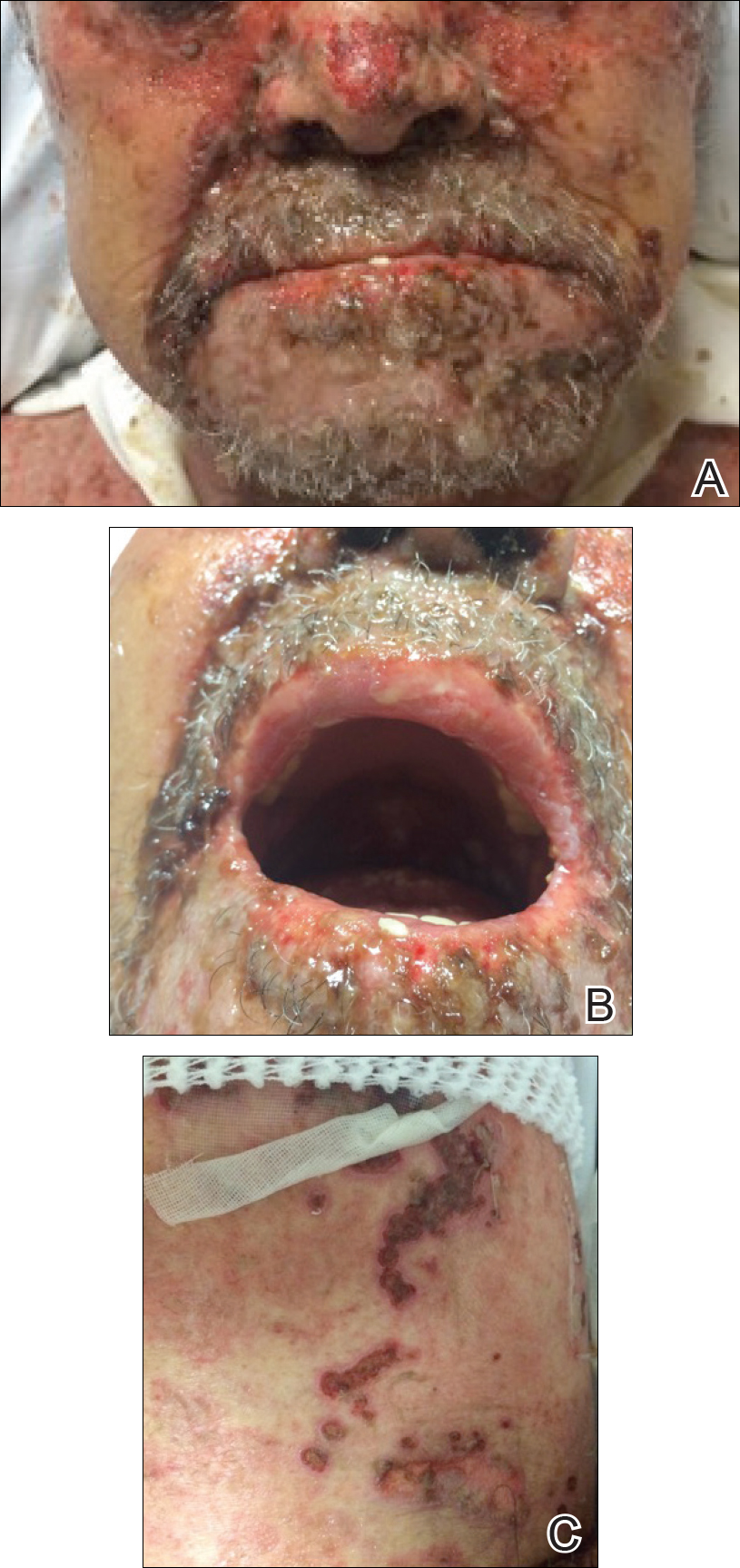

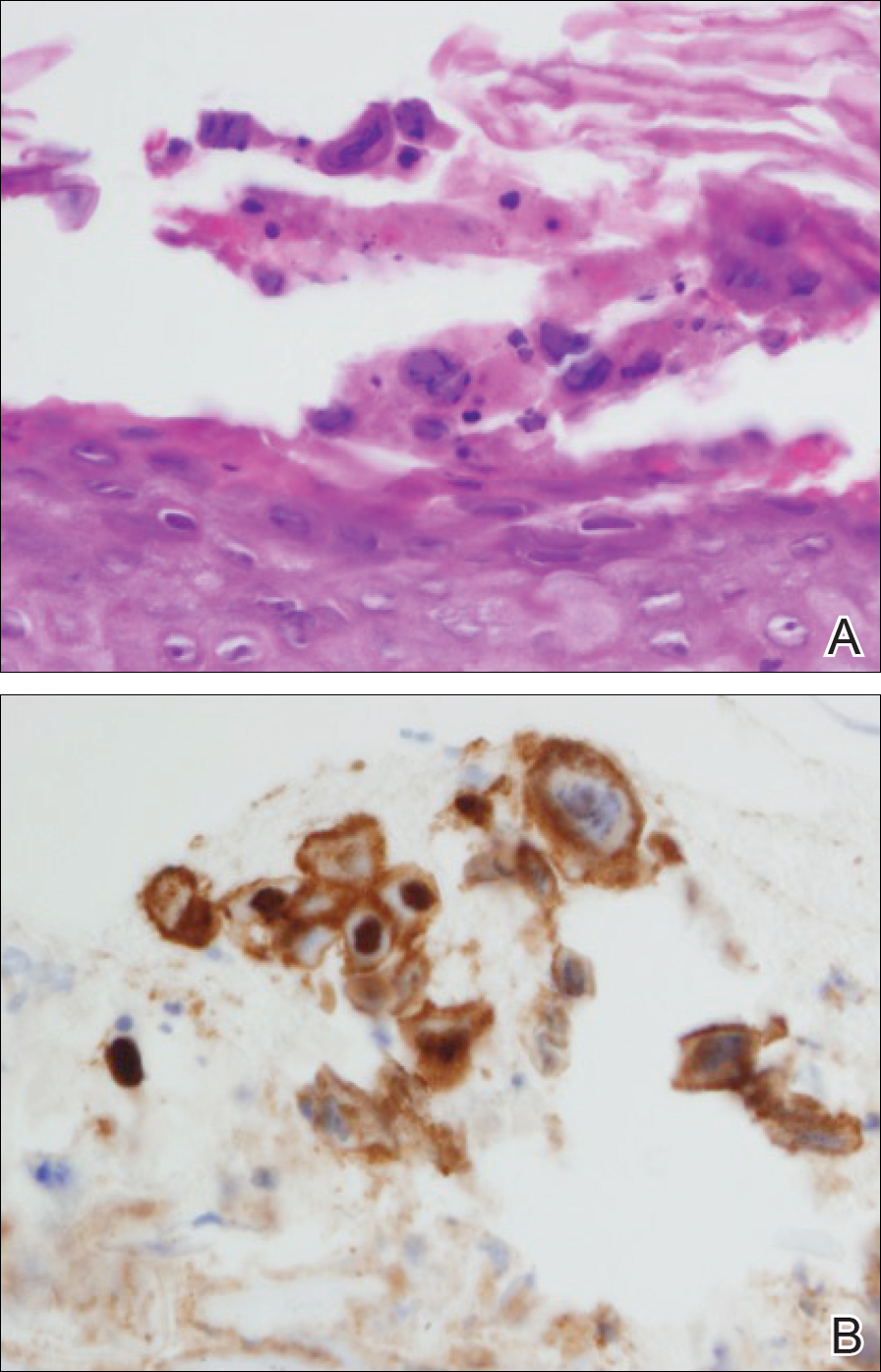

At that time, physical examination revealed numerous confluent erosions with honey-colored crust involving the entire face (Figure 1A) and sharp demarcation at the cutaneous lip (Figure 1B). There was a large erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral mucosa was spared. The trunk and proximal extremities showed numerous grouped, punched-out erosions with scalloped borders (Figure 1C). A repeat skin biopsy showed an ulcer with viral cytopathic changes. Immunoperoxidase studies demonstrated positive staining for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (Figure 2). The original slides were a frozen section from an outside facility and could not be obtained. A tissue culture and direct fluorescent antibody also confirmed HSV-1, and the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes. He was rapidly tapered off of the steroids and started on IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 21 days. All prior erosions reepithelialized within 7 days of treatment (Figure 3). The patient had an otherwise uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on hospital day 21.

Comment

A patient with an acute generalized blistering eruption requires urgent workup and treatment given the potentially devastating sequelae. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and immunobullous diseases often are the first diagnoses to be ruled out. Certainly infections such as HSV can cause a vesicular and erosive eruption, especially in the setting of a poorly controlled dermatitis, but they typically are not in the same differential as the other diagnoses.

Clinical Presentation

This case highlights 2 key physical examination findings that can alert the clinician to a possible underlying herpetic infection. First, the distribution of this patient’s oral lesions was telling. In most cases of TEN or pemphigus vulgaris, there is notable involvement of the oral mucosa, particularly the buccal and labial mucosa. Although herpes can involve any mucocutaneous surface, it does have a predilection for keratinized tissue, with the tongue and cutaneous lip commonly involved.2,3 Our patient had a solitary linear erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral cavity was strikingly spared. In addition, the erosions around the mouth stopped right at the cutaneous lip, sparing the labial mucosa (Figure 1B).

Second, the configuration of the erosions on the trunk, arms, and legs was diagnostic. Herpes classically presents as a cluster of vesicles overlying an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out erosions are left behind. Because these vesicles often are grouped, they can develop a scalloped border, which is a helpful indicator of HSV (Figure 1C). When these erosions become more confluent and irregular, the distinction from other conditions may not be as clear. A careful skin examination often can show areas that have preserved this herpetiform configuration.

Immune Compromise

Additionally, this case is illustrative of how immunosuppression and immunocompromise can affect the clinical presentation of HSV infection. Herpetic infections in the immunocompromised host tend to have a more protracted course, with chronic enlarging ulcers involving multiple sites.

Conclusion

This case is a good reminder that not everything that blisters and involves the mucosa is due to a hypersensitivity state such as TEN and Stevens-Johnson syndrome or an immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans. The fact that this patient was worsening despite drug cessation, high-dose steroids, and IV immunoglobulin should have indicated a misdiagnosis. This case also shows that the early histopathologic findings of disseminated HSV and TEN can be nonspecific, and viral cytopathic changes may not always be obvious early in the disease.

Disseminated HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, and careful history and physical examination should be taken to rule out a viral etiology.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008.

- Woo SB, Lee SF. Oral recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:239-243.

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)

At that time, physical examination revealed numerous confluent erosions with honey-colored crust involving the entire face (Figure 1A) and sharp demarcation at the cutaneous lip (Figure 1B). There was a large erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral mucosa was spared. The trunk and proximal extremities showed numerous grouped, punched-out erosions with scalloped borders (Figure 1C). A repeat skin biopsy showed an ulcer with viral cytopathic changes. Immunoperoxidase studies demonstrated positive staining for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (Figure 2). The original slides were a frozen section from an outside facility and could not be obtained. A tissue culture and direct fluorescent antibody also confirmed HSV-1, and the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes. He was rapidly tapered off of the steroids and started on IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 21 days. All prior erosions reepithelialized within 7 days of treatment (Figure 3). The patient had an otherwise uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on hospital day 21.

Comment

A patient with an acute generalized blistering eruption requires urgent workup and treatment given the potentially devastating sequelae. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and immunobullous diseases often are the first diagnoses to be ruled out. Certainly infections such as HSV can cause a vesicular and erosive eruption, especially in the setting of a poorly controlled dermatitis, but they typically are not in the same differential as the other diagnoses.

Clinical Presentation

This case highlights 2 key physical examination findings that can alert the clinician to a possible underlying herpetic infection. First, the distribution of this patient’s oral lesions was telling. In most cases of TEN or pemphigus vulgaris, there is notable involvement of the oral mucosa, particularly the buccal and labial mucosa. Although herpes can involve any mucocutaneous surface, it does have a predilection for keratinized tissue, with the tongue and cutaneous lip commonly involved.2,3 Our patient had a solitary linear erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral cavity was strikingly spared. In addition, the erosions around the mouth stopped right at the cutaneous lip, sparing the labial mucosa (Figure 1B).

Second, the configuration of the erosions on the trunk, arms, and legs was diagnostic. Herpes classically presents as a cluster of vesicles overlying an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out erosions are left behind. Because these vesicles often are grouped, they can develop a scalloped border, which is a helpful indicator of HSV (Figure 1C). When these erosions become more confluent and irregular, the distinction from other conditions may not be as clear. A careful skin examination often can show areas that have preserved this herpetiform configuration.

Immune Compromise

Additionally, this case is illustrative of how immunosuppression and immunocompromise can affect the clinical presentation of HSV infection. Herpetic infections in the immunocompromised host tend to have a more protracted course, with chronic enlarging ulcers involving multiple sites.

Conclusion

This case is a good reminder that not everything that blisters and involves the mucosa is due to a hypersensitivity state such as TEN and Stevens-Johnson syndrome or an immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans. The fact that this patient was worsening despite drug cessation, high-dose steroids, and IV immunoglobulin should have indicated a misdiagnosis. This case also shows that the early histopathologic findings of disseminated HSV and TEN can be nonspecific, and viral cytopathic changes may not always be obvious early in the disease.

Disseminated HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, and careful history and physical examination should be taken to rule out a viral etiology.

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)

At that time, physical examination revealed numerous confluent erosions with honey-colored crust involving the entire face (Figure 1A) and sharp demarcation at the cutaneous lip (Figure 1B). There was a large erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral mucosa was spared. The trunk and proximal extremities showed numerous grouped, punched-out erosions with scalloped borders (Figure 1C). A repeat skin biopsy showed an ulcer with viral cytopathic changes. Immunoperoxidase studies demonstrated positive staining for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (Figure 2). The original slides were a frozen section from an outside facility and could not be obtained. A tissue culture and direct fluorescent antibody also confirmed HSV-1, and the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes. He was rapidly tapered off of the steroids and started on IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 21 days. All prior erosions reepithelialized within 7 days of treatment (Figure 3). The patient had an otherwise uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on hospital day 21.

Comment

A patient with an acute generalized blistering eruption requires urgent workup and treatment given the potentially devastating sequelae. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and immunobullous diseases often are the first diagnoses to be ruled out. Certainly infections such as HSV can cause a vesicular and erosive eruption, especially in the setting of a poorly controlled dermatitis, but they typically are not in the same differential as the other diagnoses.

Clinical Presentation

This case highlights 2 key physical examination findings that can alert the clinician to a possible underlying herpetic infection. First, the distribution of this patient’s oral lesions was telling. In most cases of TEN or pemphigus vulgaris, there is notable involvement of the oral mucosa, particularly the buccal and labial mucosa. Although herpes can involve any mucocutaneous surface, it does have a predilection for keratinized tissue, with the tongue and cutaneous lip commonly involved.2,3 Our patient had a solitary linear erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral cavity was strikingly spared. In addition, the erosions around the mouth stopped right at the cutaneous lip, sparing the labial mucosa (Figure 1B).

Second, the configuration of the erosions on the trunk, arms, and legs was diagnostic. Herpes classically presents as a cluster of vesicles overlying an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out erosions are left behind. Because these vesicles often are grouped, they can develop a scalloped border, which is a helpful indicator of HSV (Figure 1C). When these erosions become more confluent and irregular, the distinction from other conditions may not be as clear. A careful skin examination often can show areas that have preserved this herpetiform configuration.

Immune Compromise

Additionally, this case is illustrative of how immunosuppression and immunocompromise can affect the clinical presentation of HSV infection. Herpetic infections in the immunocompromised host tend to have a more protracted course, with chronic enlarging ulcers involving multiple sites.

Conclusion

This case is a good reminder that not everything that blisters and involves the mucosa is due to a hypersensitivity state such as TEN and Stevens-Johnson syndrome or an immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans. The fact that this patient was worsening despite drug cessation, high-dose steroids, and IV immunoglobulin should have indicated a misdiagnosis. This case also shows that the early histopathologic findings of disseminated HSV and TEN can be nonspecific, and viral cytopathic changes may not always be obvious early in the disease.

Disseminated HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, and careful history and physical examination should be taken to rule out a viral etiology.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008.

- Woo SB, Lee SF. Oral recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:239-243.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008.

- Woo SB, Lee SF. Oral recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:239-243.

Practice Points

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis can be difficult to diagnose and treat.

- Patients who are refractory to treatment should prompt further management considerations.

Brown-Black Papulonodules on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

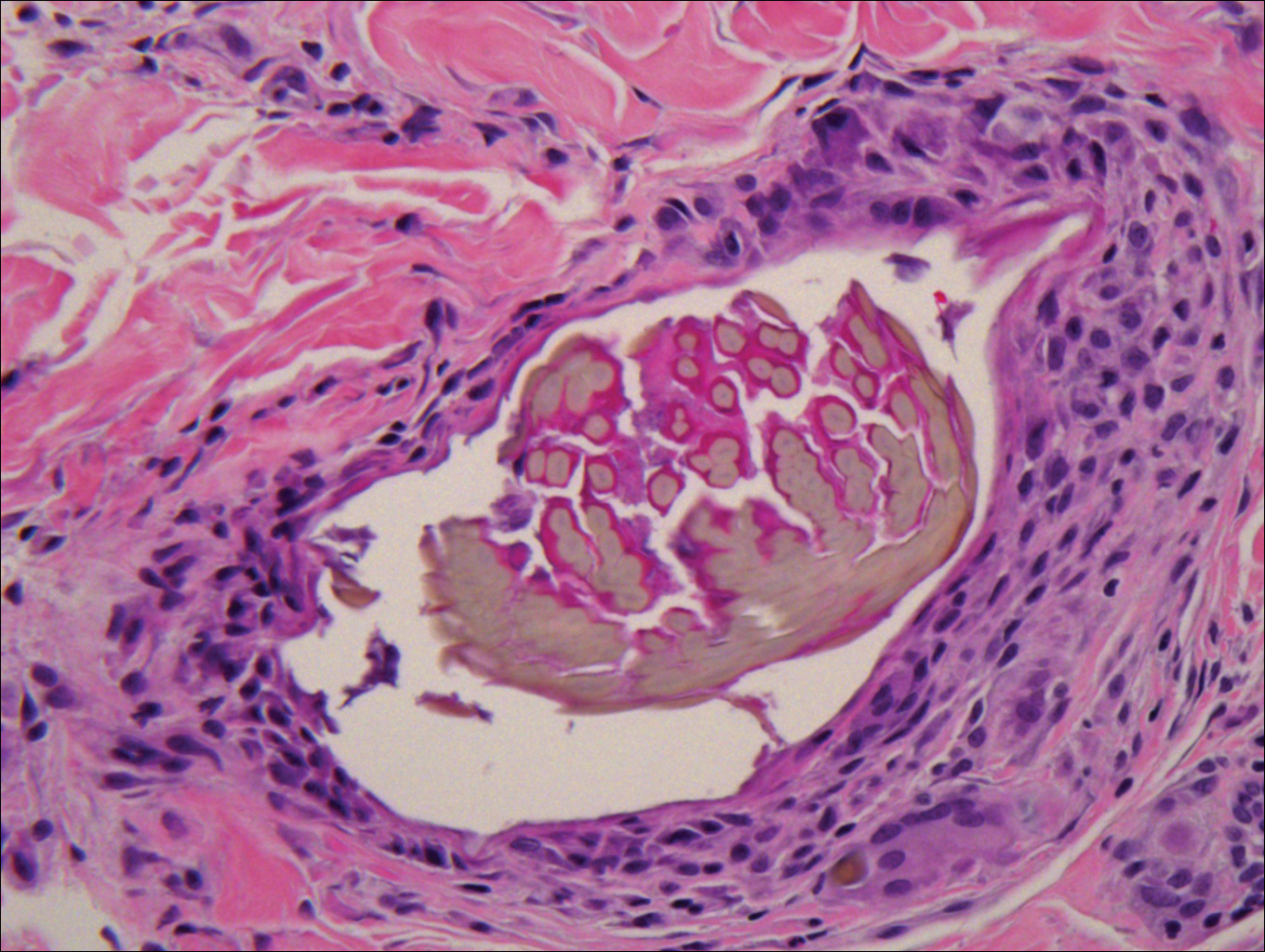

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.