User login

Solitary Tender Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

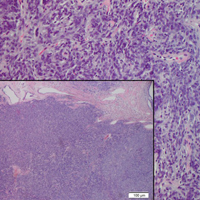

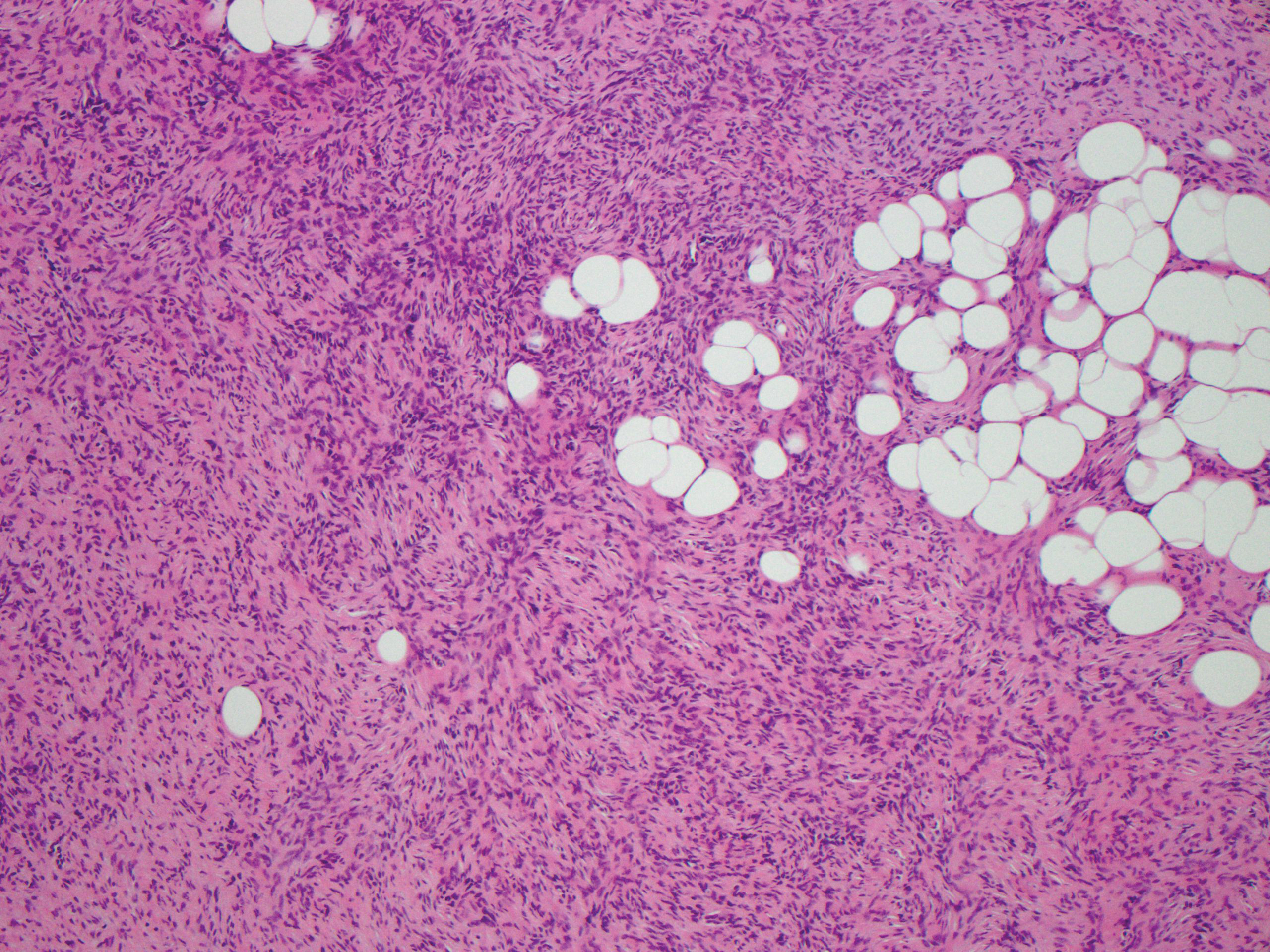

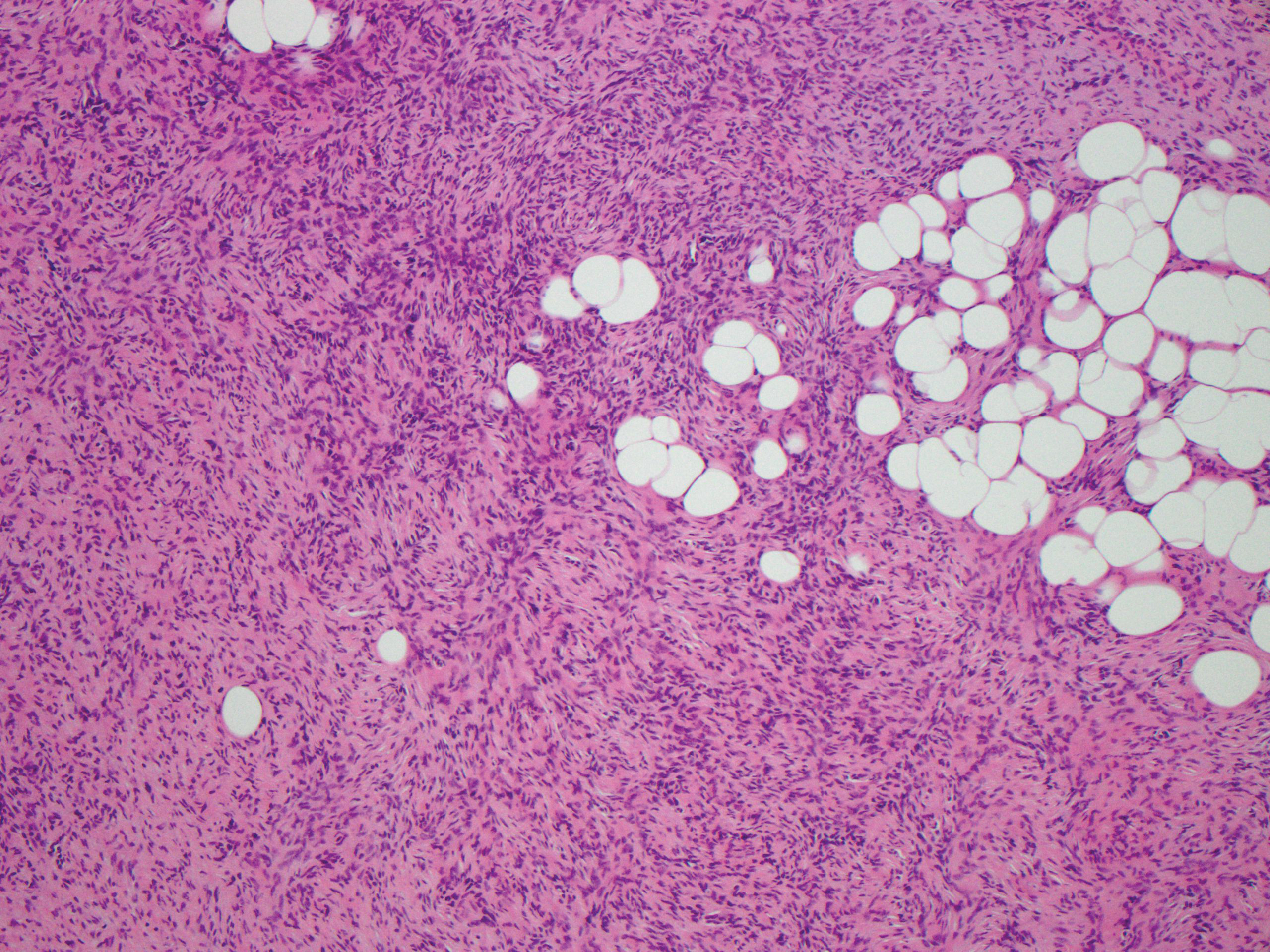

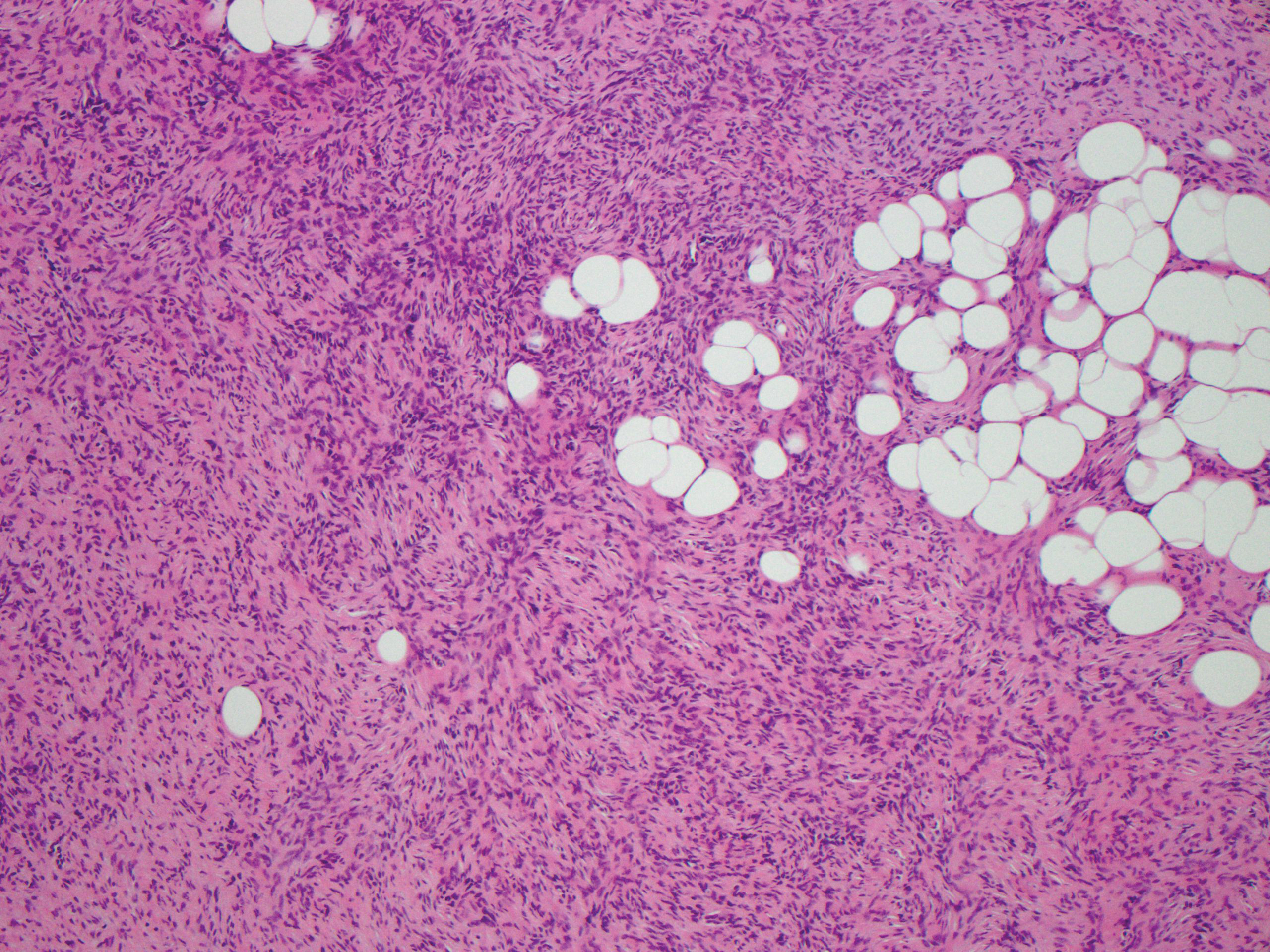

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

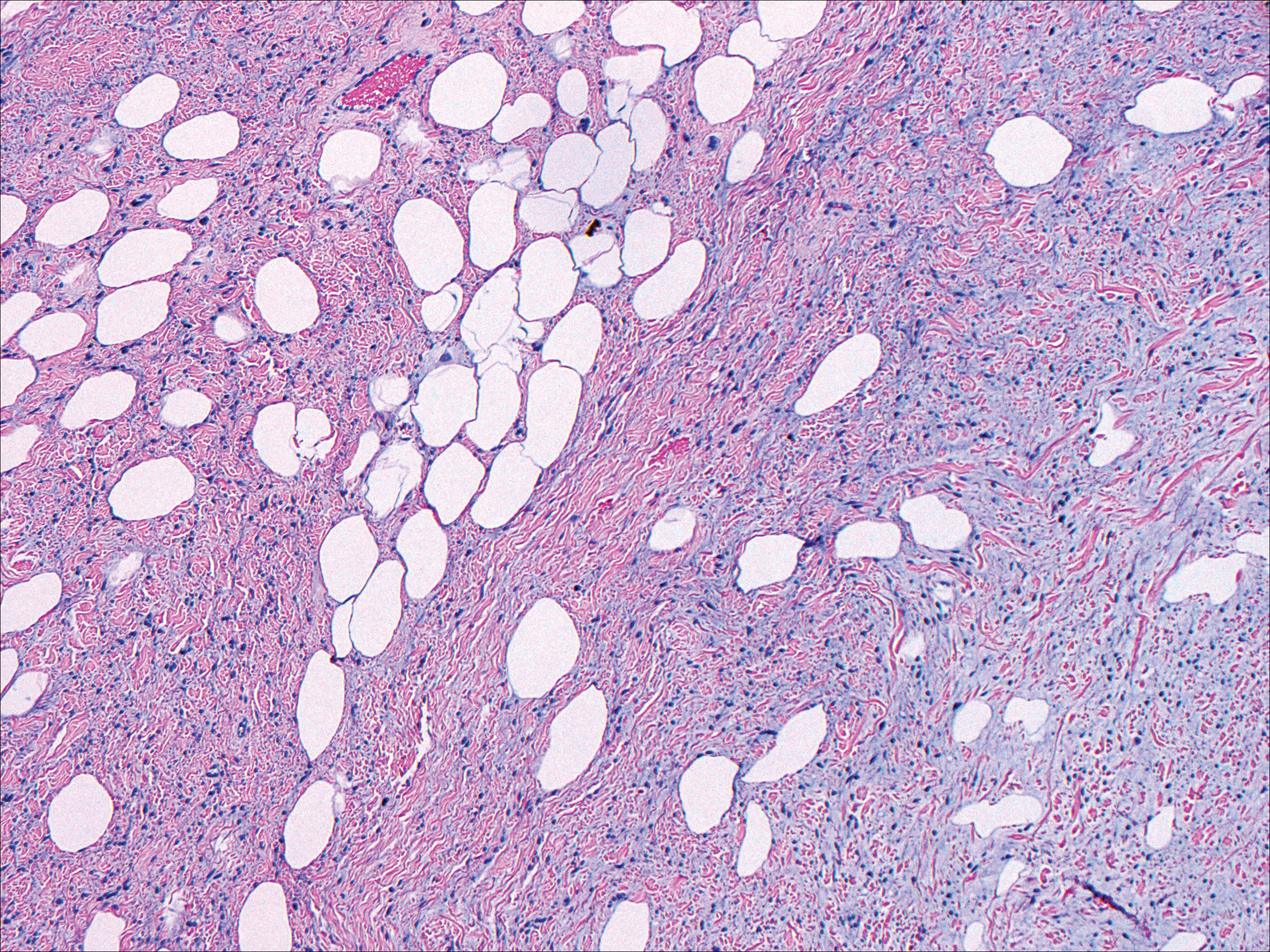

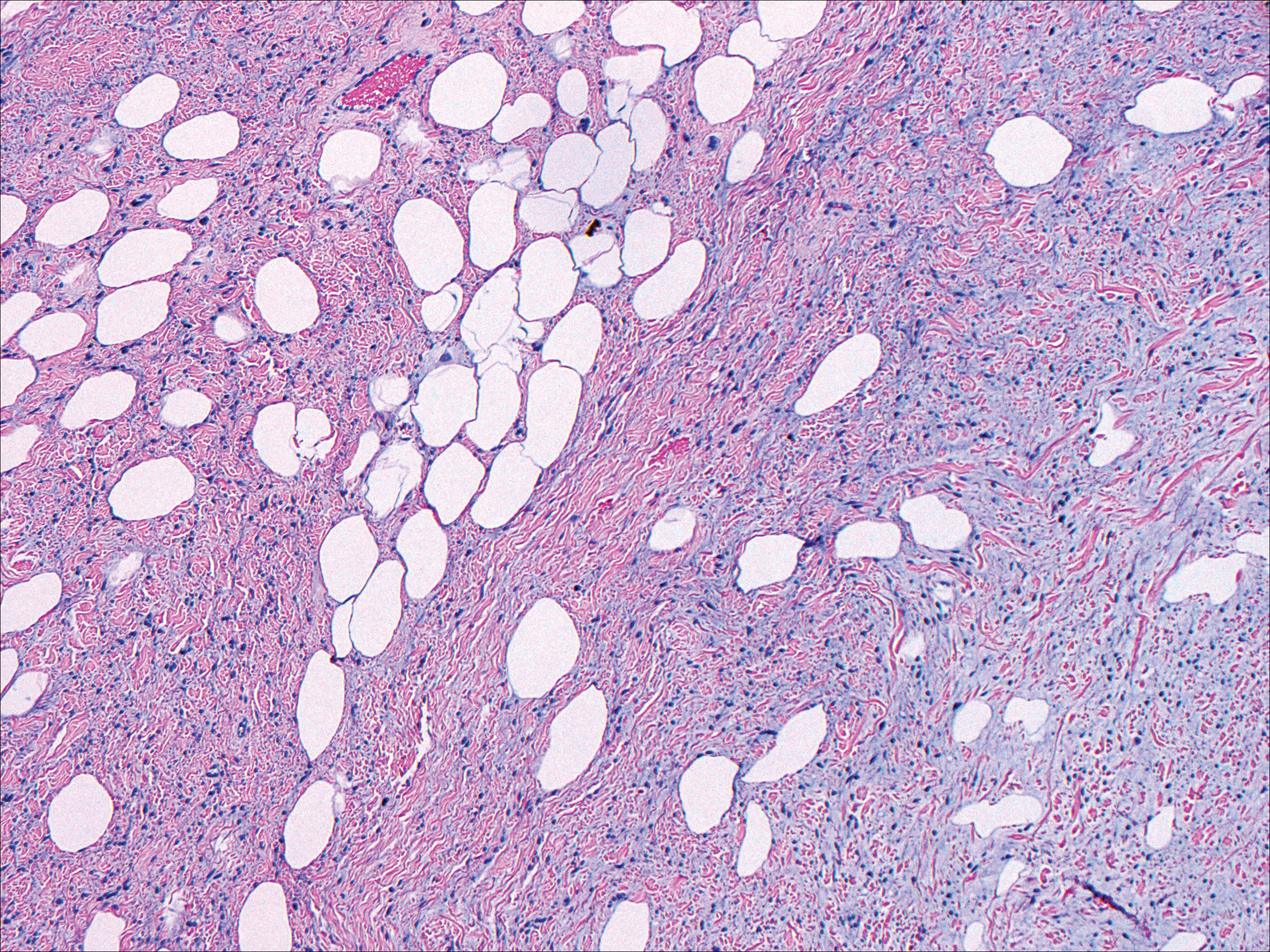

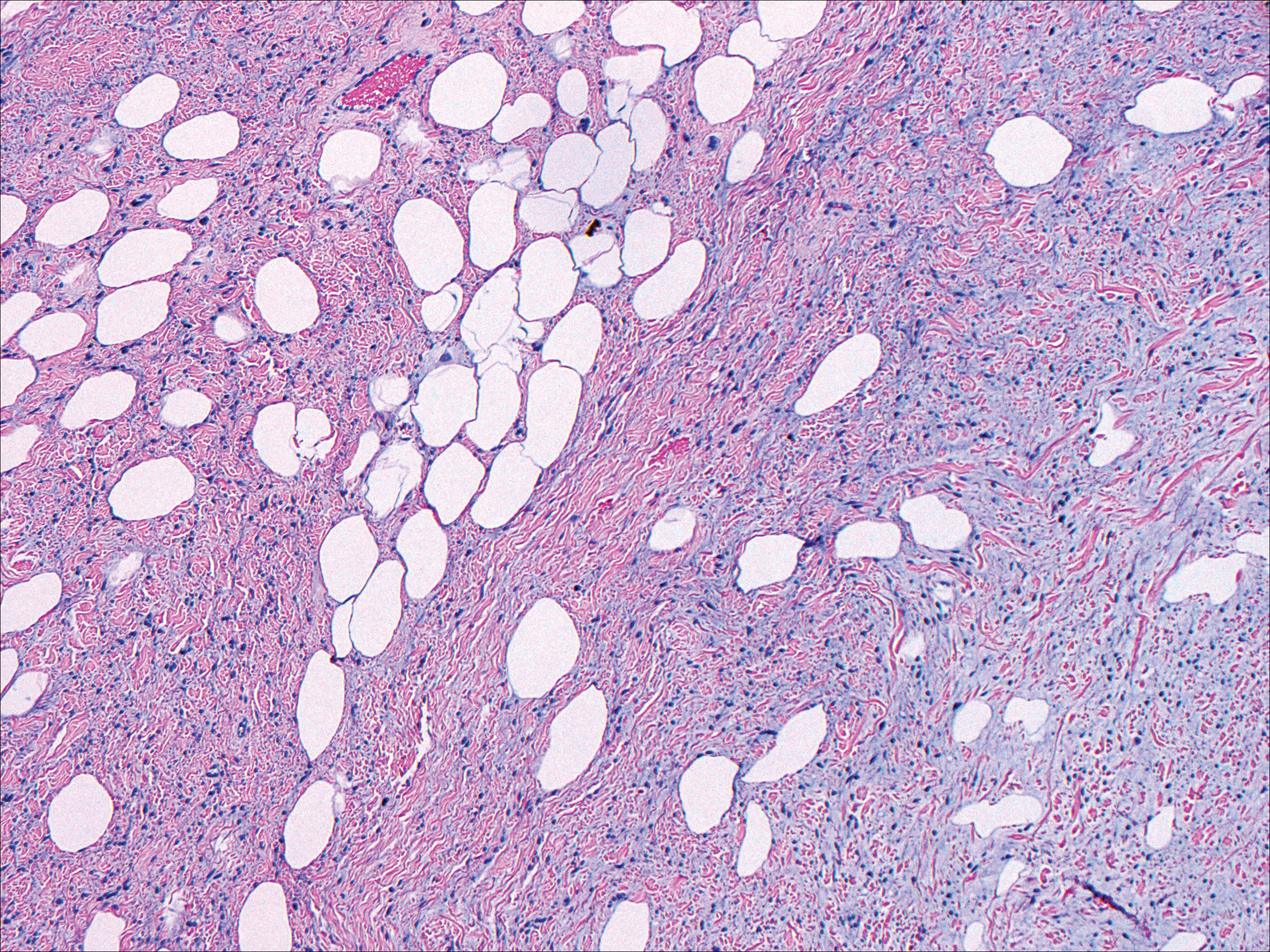

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

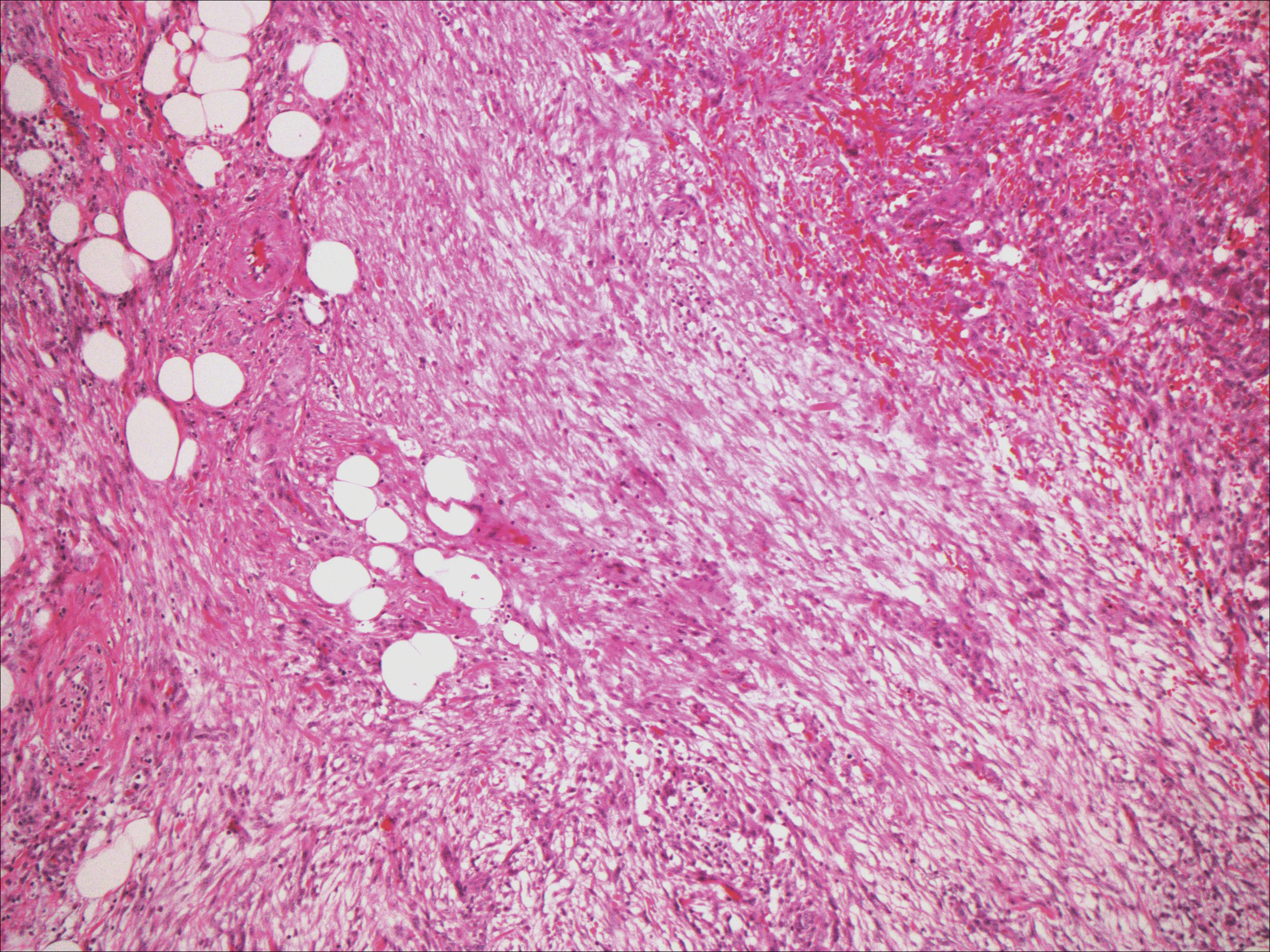

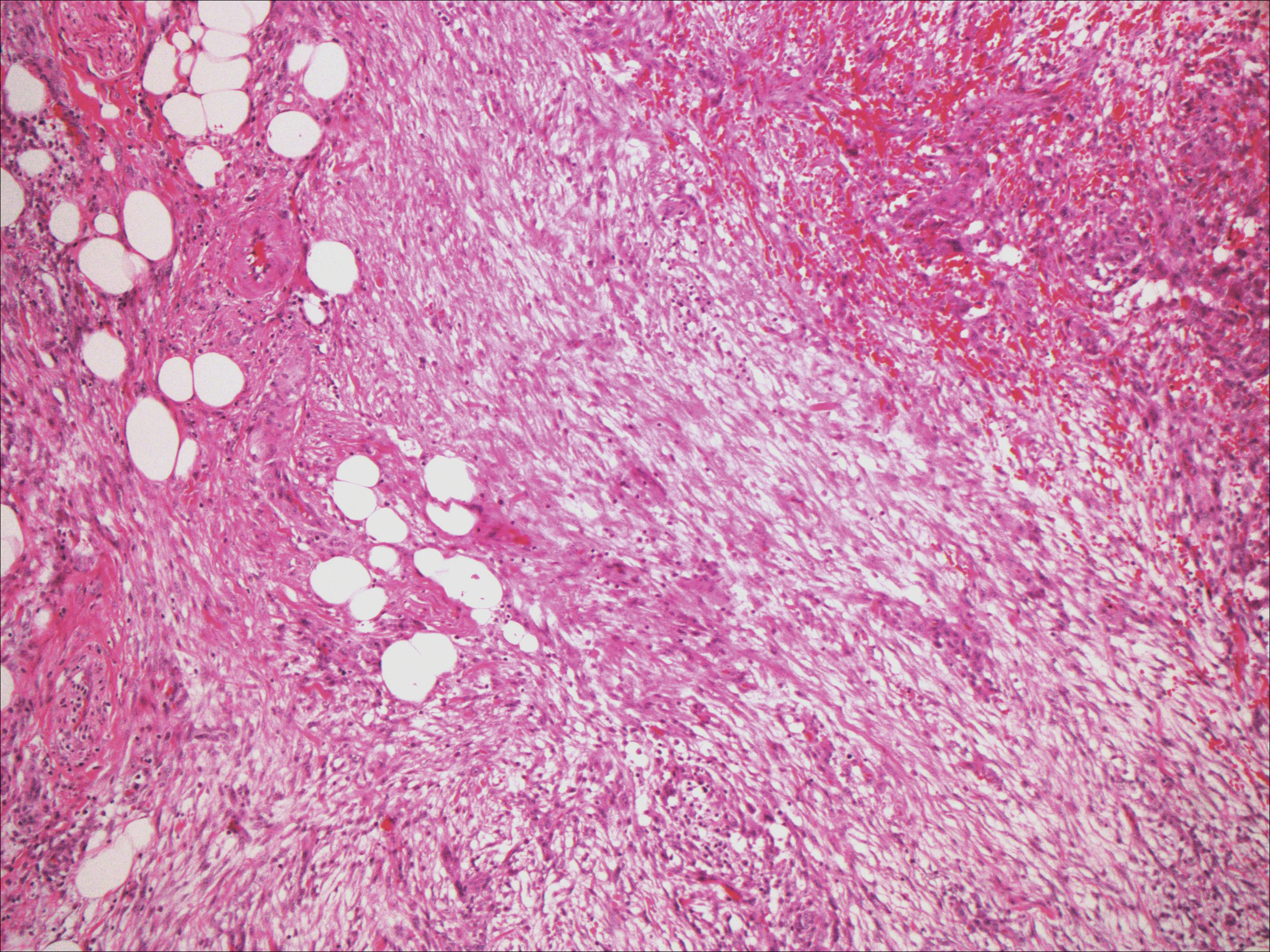

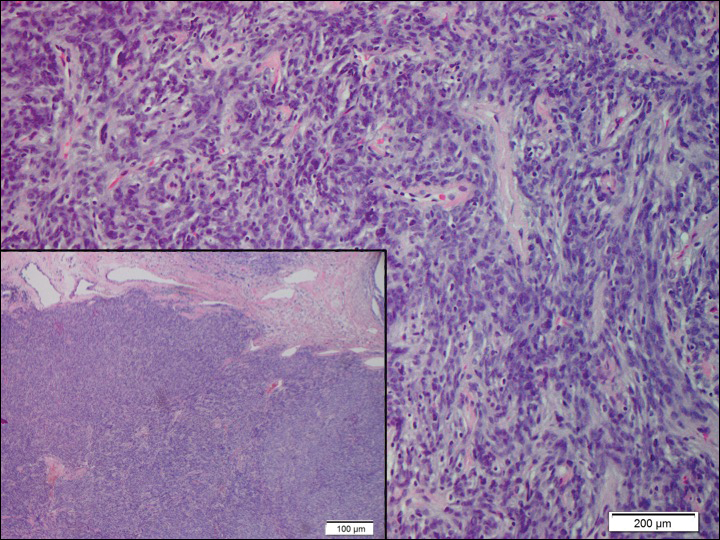

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

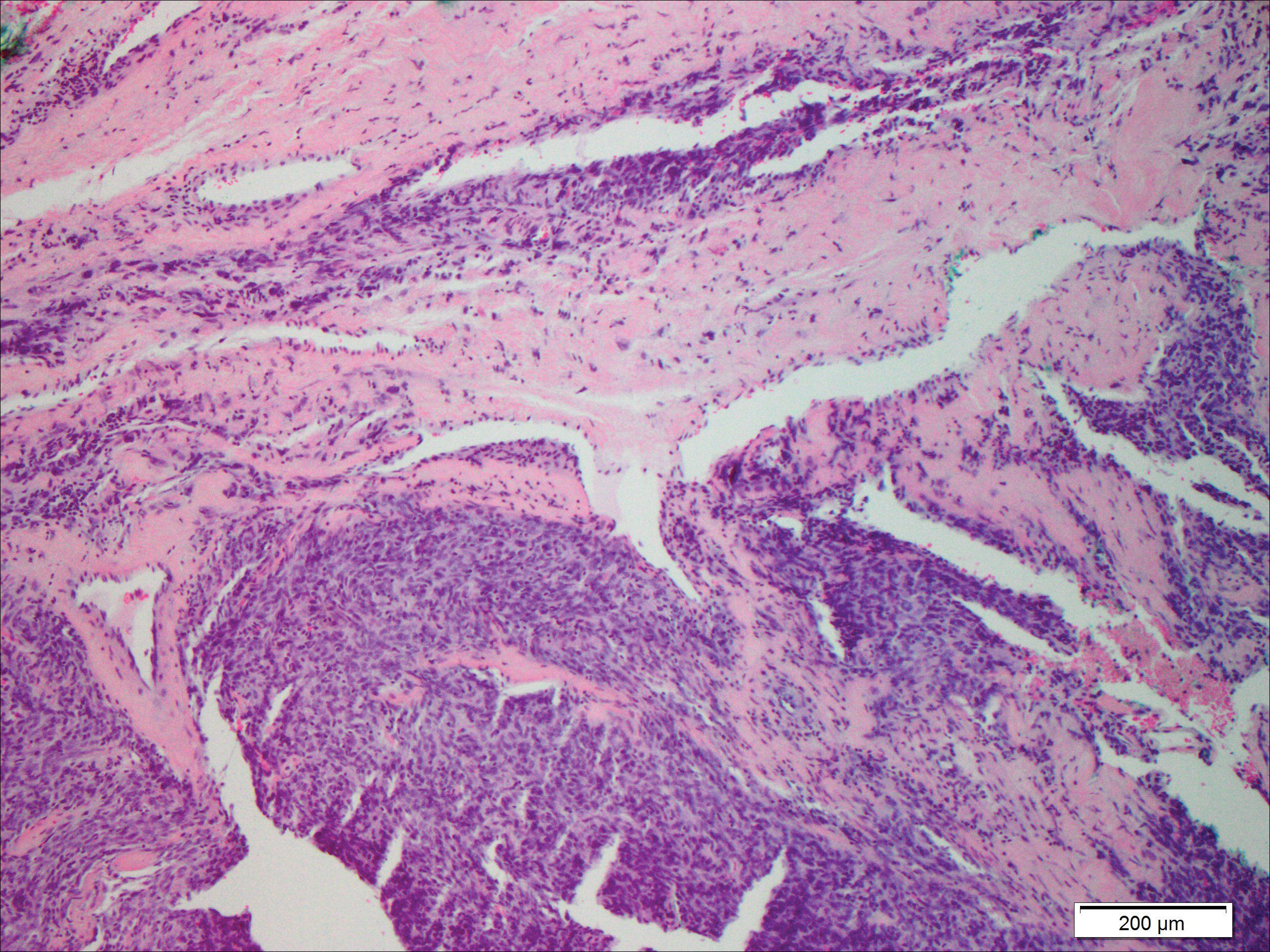

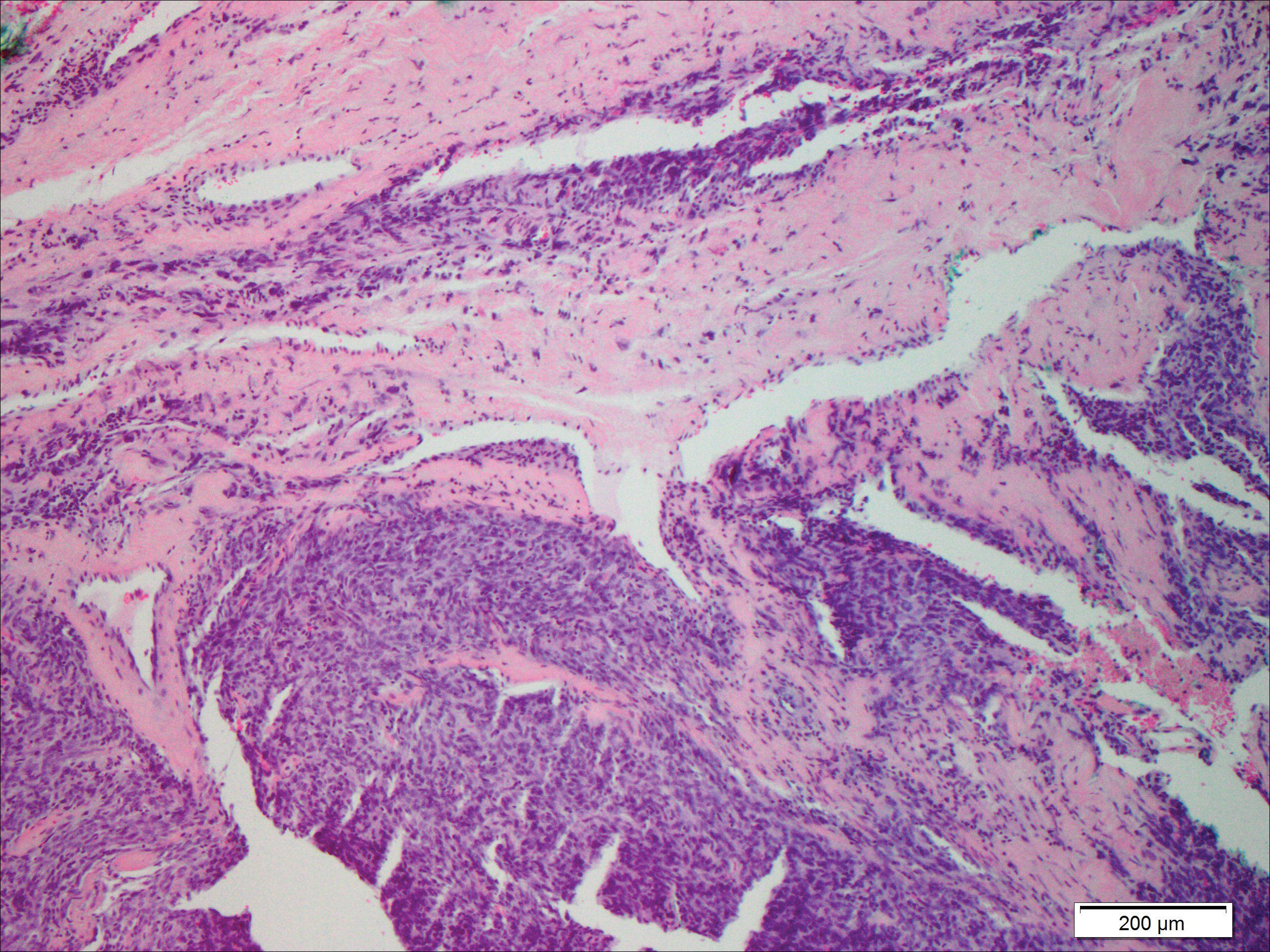

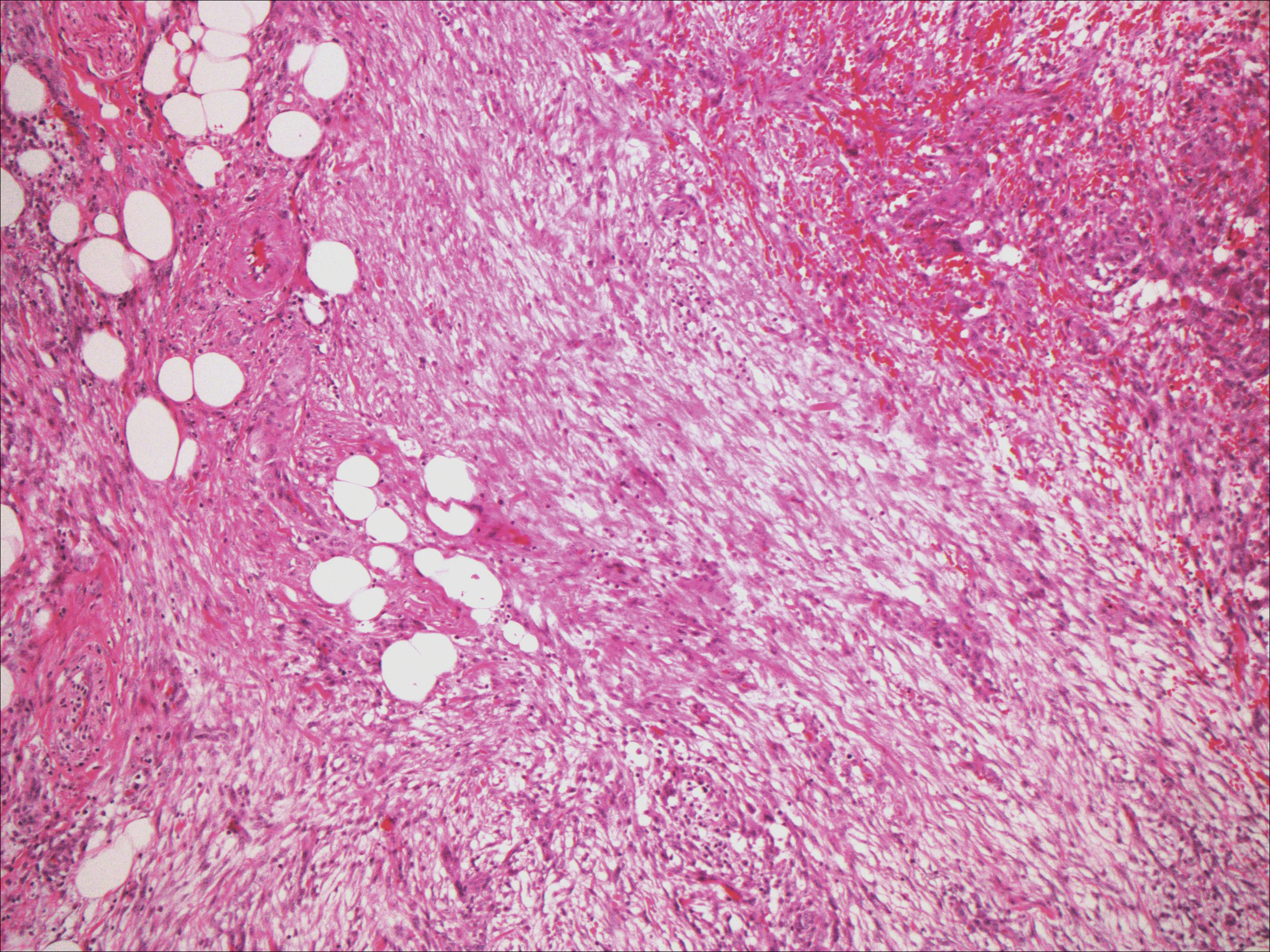

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

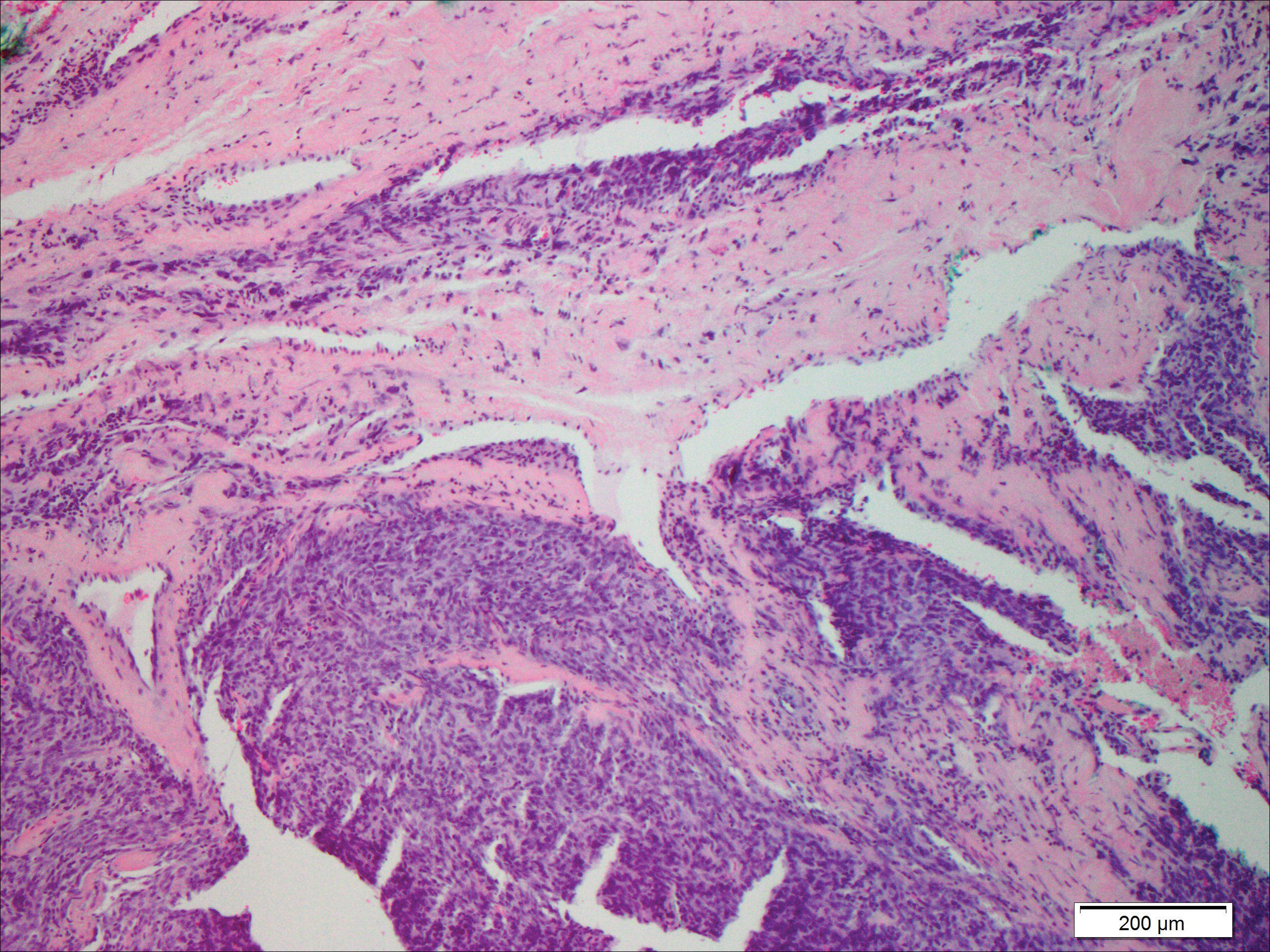

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

A 73-year-old man presented with a tender nodule on the back that had recently increased in size. On physical examination, a solitary 4-cm nodule was noted in the right trapezius region. The patient denied any personal or family history of similar lesions or a penchant for cysts. Due to the symptomatic nature of the lesion, surgical excision was performed.

Black Eschars on the Face and Body

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

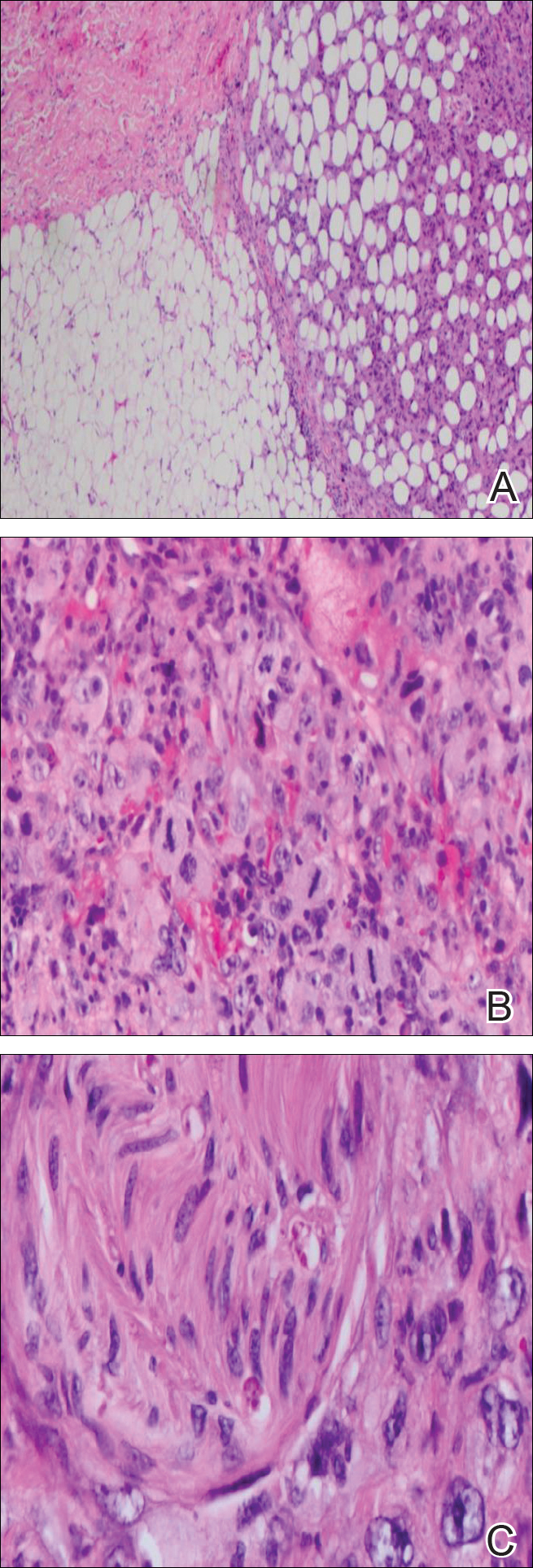

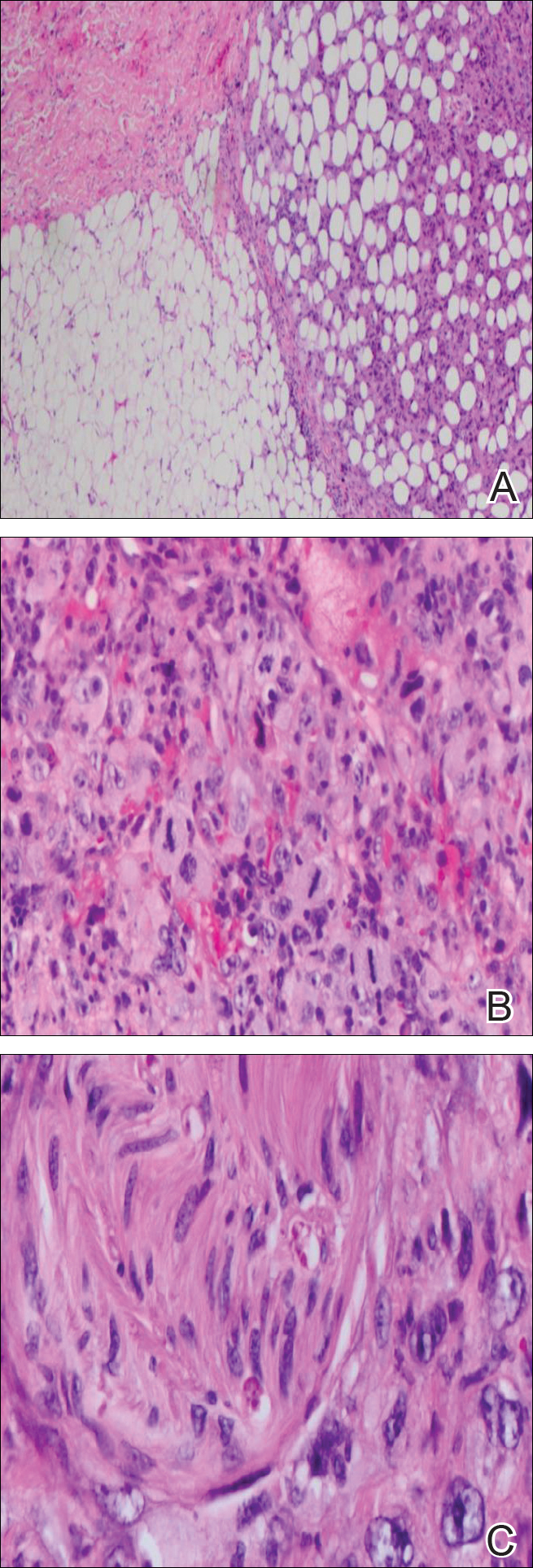

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical examination of the ulcer revealed a dense nodular and diffuse infiltrate in the papillary and reticular dermis comprised predominantly of atypical, CD30+, small T cells and large lymphoid cells admixed with neutrophils and eosinophils (Figures 1 and 2). Tissue cultures and infectious stains were negative. The complete blood cell count, metabolic panel, serum lactate dehydrogenase level, and peripheral blood flow cytometry were normal. Correlation of the lesions' self-healing nature with the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings led to a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). In light of this diagnosis, a shave biopsy was obtained of one of the patient's poikilodermatous patches and was found to be consistent with poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides (MF).

At 4-month follow-up, the patient reported that she continued to develop crops of 1 to 3 LyP lesions each month. She continued to deny systemic concerns, and the poikilodermatous MF appeared unchanged. As part of a hematologic workup, a positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan revealed glucose-avid lymph nodes in the axillary, supraclavicular, abdominal, and inguinal regions. These findings raised concern for possible lymphomatous involvement of the patient's MF. Systemic therapy may be required pending further surveillance.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic papulonecrotic disease characterized clinically by recurrent crops of self-healing papules. Histopathologically, LyP features a perivascular infiltrate with atypical dermal T cells. Macaulay1 first described LyP in 1968 in a 41-year-old woman with a several-year history of continuously self-resolving crops of necrotic papules, noting the paradox between the patient's benign clinical course and malignant-seeming histology featuring "an alarming infiltrate of anaplastic cells." Since this report, LyP has continued to spur debate regarding its malignant potential but is now recognized as an indolent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with an excellent prognosis.2

There are several histopathologic subtypes of LyP, the most common of which are type A, resembling Hodgkin lymphoma; type B, resembling MF; type C, resembling primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL); and type D, resembling aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2

The multifocal ulcers and eschars of LyP may appropriately raise suspicion for an infectious process, as in the present case. Numerous reports show that LyP may be initially misdiagnosed as an infection, such as cellulitis,3 furunculosis,4 parapoxvirus Orf,5 and ecthyma.6 Furthermore, several cutaneous infections have histopathologic features indistinguishable from LyP.7 For example, herpes simplex virus infection, molluscum contagiosum, Milker nodule, syphilis, and leishmaniasis may contain an appreciable number of large CD30+ T cells, which is compatible with both LyP type C and C-ALCL.7 As in the present case, the final diagnosis rests on clinicopathologic correlation, with LyP often distinguished by its invariable self-resolution, unlike its numerous infectious mimickers. The self-regressing nature of LyP also helps differentiate LyP occurring in the setting of MF from MF that has underwent CD30+ large cell transformation. In addition, the diagnosis of MF-associated LyP is favored over transformed MF when, as in the present case, CD30+ lesions develop on skin distinct from MF-affected skin.

Although isolated LyP is benign, 18% (11/61) of patients will subsequently develop lymphoma. More commonly, lymphomas may precede or occur concomitantly with the onset of LyP. In a retrospective study of 84 LyP patients, for example, 40% (34/84) had prior or concomitant lymphoma.8 Owing to the well-established link between LyP and lymphoma, there is appropriate emphasis on close monitoring of these patients. In addition, a careful history and physical examination are necessary to evaluate for a preceding, previously undiagnosed lymphoma. In point of fact, our patient had undiagnosed poikilodermatous MF prior to developing LyP, which was proven by biopsy at the time of LyP diagnosis. A distinct clinical variant of MF, poikilodermatous MF is characterized by hyperpigmented and hypopigmented patches, atrophy, and telangiectasia. A study of 49 patients with poikilodermatous MF found that this variant had an earlier age of onset compared with other types of MF. The study also showed that 18% (9/49) of patients had coexistent LyP, suggesting that poikilodermatous MF and LyP may be more frequently associated than previously believed.9

Treatment of LyP is unnecessary beyond basic wound care to avoid bacterial superinfection.2,10 Therapy for poikilodermatous MF, similar to other types of MF, is based on disease stage. Topical therapy may be utilized for localized disease, while systemic therapies are reserved for recalcitrant cases and internal involvement.9

Acknowledgments

We thank David L. Ramsay, MD, for obtaining aspects of the patient's history, and Shane A. Meehan, MD, and Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, as well as Cynthia M. Magro, MD, (all from New York, New York) for performing the histopathologic and immunohistochemical analyses.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis. a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Meena M, Martin PA, Abouseif C, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis type C of the eyelid in a young girl: a case report and review of literature. Orbit. 2014;3:395-398.

- Dinotta F, Lacarrubba F, Micali G. Sixteen-year-old girl with papules and nodules on the face and upper limbs. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:103-104.

- Eminger LA, Shinohara MM, Kim EJ, et al. Clinicopathologic challenge: acral lymphomatoid papulosis. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:531-534.

- Harder D, Kuhn A, Mahrle G. Lymphomatoid papulosis resembling ecthyma. a case report. Z Hautkr. 1989;64:593-595.

- Werner B, Massone C, Kerl H, et al. Large CD30-positive cells in benign, atypical lymphoid infiltrates of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1100-1107.

- Kunishige JH, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-581.

- Abbott RA, Sahni D, Robson A, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides: a study of its clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and prognostic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:313-319.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical examination of the ulcer revealed a dense nodular and diffuse infiltrate in the papillary and reticular dermis comprised predominantly of atypical, CD30+, small T cells and large lymphoid cells admixed with neutrophils and eosinophils (Figures 1 and 2). Tissue cultures and infectious stains were negative. The complete blood cell count, metabolic panel, serum lactate dehydrogenase level, and peripheral blood flow cytometry were normal. Correlation of the lesions' self-healing nature with the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings led to a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). In light of this diagnosis, a shave biopsy was obtained of one of the patient's poikilodermatous patches and was found to be consistent with poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides (MF).

At 4-month follow-up, the patient reported that she continued to develop crops of 1 to 3 LyP lesions each month. She continued to deny systemic concerns, and the poikilodermatous MF appeared unchanged. As part of a hematologic workup, a positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan revealed glucose-avid lymph nodes in the axillary, supraclavicular, abdominal, and inguinal regions. These findings raised concern for possible lymphomatous involvement of the patient's MF. Systemic therapy may be required pending further surveillance.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic papulonecrotic disease characterized clinically by recurrent crops of self-healing papules. Histopathologically, LyP features a perivascular infiltrate with atypical dermal T cells. Macaulay1 first described LyP in 1968 in a 41-year-old woman with a several-year history of continuously self-resolving crops of necrotic papules, noting the paradox between the patient's benign clinical course and malignant-seeming histology featuring "an alarming infiltrate of anaplastic cells." Since this report, LyP has continued to spur debate regarding its malignant potential but is now recognized as an indolent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with an excellent prognosis.2

There are several histopathologic subtypes of LyP, the most common of which are type A, resembling Hodgkin lymphoma; type B, resembling MF; type C, resembling primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL); and type D, resembling aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2

The multifocal ulcers and eschars of LyP may appropriately raise suspicion for an infectious process, as in the present case. Numerous reports show that LyP may be initially misdiagnosed as an infection, such as cellulitis,3 furunculosis,4 parapoxvirus Orf,5 and ecthyma.6 Furthermore, several cutaneous infections have histopathologic features indistinguishable from LyP.7 For example, herpes simplex virus infection, molluscum contagiosum, Milker nodule, syphilis, and leishmaniasis may contain an appreciable number of large CD30+ T cells, which is compatible with both LyP type C and C-ALCL.7 As in the present case, the final diagnosis rests on clinicopathologic correlation, with LyP often distinguished by its invariable self-resolution, unlike its numerous infectious mimickers. The self-regressing nature of LyP also helps differentiate LyP occurring in the setting of MF from MF that has underwent CD30+ large cell transformation. In addition, the diagnosis of MF-associated LyP is favored over transformed MF when, as in the present case, CD30+ lesions develop on skin distinct from MF-affected skin.

Although isolated LyP is benign, 18% (11/61) of patients will subsequently develop lymphoma. More commonly, lymphomas may precede or occur concomitantly with the onset of LyP. In a retrospective study of 84 LyP patients, for example, 40% (34/84) had prior or concomitant lymphoma.8 Owing to the well-established link between LyP and lymphoma, there is appropriate emphasis on close monitoring of these patients. In addition, a careful history and physical examination are necessary to evaluate for a preceding, previously undiagnosed lymphoma. In point of fact, our patient had undiagnosed poikilodermatous MF prior to developing LyP, which was proven by biopsy at the time of LyP diagnosis. A distinct clinical variant of MF, poikilodermatous MF is characterized by hyperpigmented and hypopigmented patches, atrophy, and telangiectasia. A study of 49 patients with poikilodermatous MF found that this variant had an earlier age of onset compared with other types of MF. The study also showed that 18% (9/49) of patients had coexistent LyP, suggesting that poikilodermatous MF and LyP may be more frequently associated than previously believed.9

Treatment of LyP is unnecessary beyond basic wound care to avoid bacterial superinfection.2,10 Therapy for poikilodermatous MF, similar to other types of MF, is based on disease stage. Topical therapy may be utilized for localized disease, while systemic therapies are reserved for recalcitrant cases and internal involvement.9

Acknowledgments

We thank David L. Ramsay, MD, for obtaining aspects of the patient's history, and Shane A. Meehan, MD, and Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, as well as Cynthia M. Magro, MD, (all from New York, New York) for performing the histopathologic and immunohistochemical analyses.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical examination of the ulcer revealed a dense nodular and diffuse infiltrate in the papillary and reticular dermis comprised predominantly of atypical, CD30+, small T cells and large lymphoid cells admixed with neutrophils and eosinophils (Figures 1 and 2). Tissue cultures and infectious stains were negative. The complete blood cell count, metabolic panel, serum lactate dehydrogenase level, and peripheral blood flow cytometry were normal. Correlation of the lesions' self-healing nature with the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings led to a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). In light of this diagnosis, a shave biopsy was obtained of one of the patient's poikilodermatous patches and was found to be consistent with poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides (MF).

At 4-month follow-up, the patient reported that she continued to develop crops of 1 to 3 LyP lesions each month. She continued to deny systemic concerns, and the poikilodermatous MF appeared unchanged. As part of a hematologic workup, a positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan revealed glucose-avid lymph nodes in the axillary, supraclavicular, abdominal, and inguinal regions. These findings raised concern for possible lymphomatous involvement of the patient's MF. Systemic therapy may be required pending further surveillance.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic papulonecrotic disease characterized clinically by recurrent crops of self-healing papules. Histopathologically, LyP features a perivascular infiltrate with atypical dermal T cells. Macaulay1 first described LyP in 1968 in a 41-year-old woman with a several-year history of continuously self-resolving crops of necrotic papules, noting the paradox between the patient's benign clinical course and malignant-seeming histology featuring "an alarming infiltrate of anaplastic cells." Since this report, LyP has continued to spur debate regarding its malignant potential but is now recognized as an indolent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with an excellent prognosis.2

There are several histopathologic subtypes of LyP, the most common of which are type A, resembling Hodgkin lymphoma; type B, resembling MF; type C, resembling primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL); and type D, resembling aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.2

The multifocal ulcers and eschars of LyP may appropriately raise suspicion for an infectious process, as in the present case. Numerous reports show that LyP may be initially misdiagnosed as an infection, such as cellulitis,3 furunculosis,4 parapoxvirus Orf,5 and ecthyma.6 Furthermore, several cutaneous infections have histopathologic features indistinguishable from LyP.7 For example, herpes simplex virus infection, molluscum contagiosum, Milker nodule, syphilis, and leishmaniasis may contain an appreciable number of large CD30+ T cells, which is compatible with both LyP type C and C-ALCL.7 As in the present case, the final diagnosis rests on clinicopathologic correlation, with LyP often distinguished by its invariable self-resolution, unlike its numerous infectious mimickers. The self-regressing nature of LyP also helps differentiate LyP occurring in the setting of MF from MF that has underwent CD30+ large cell transformation. In addition, the diagnosis of MF-associated LyP is favored over transformed MF when, as in the present case, CD30+ lesions develop on skin distinct from MF-affected skin.

Although isolated LyP is benign, 18% (11/61) of patients will subsequently develop lymphoma. More commonly, lymphomas may precede or occur concomitantly with the onset of LyP. In a retrospective study of 84 LyP patients, for example, 40% (34/84) had prior or concomitant lymphoma.8 Owing to the well-established link between LyP and lymphoma, there is appropriate emphasis on close monitoring of these patients. In addition, a careful history and physical examination are necessary to evaluate for a preceding, previously undiagnosed lymphoma. In point of fact, our patient had undiagnosed poikilodermatous MF prior to developing LyP, which was proven by biopsy at the time of LyP diagnosis. A distinct clinical variant of MF, poikilodermatous MF is characterized by hyperpigmented and hypopigmented patches, atrophy, and telangiectasia. A study of 49 patients with poikilodermatous MF found that this variant had an earlier age of onset compared with other types of MF. The study also showed that 18% (9/49) of patients had coexistent LyP, suggesting that poikilodermatous MF and LyP may be more frequently associated than previously believed.9

Treatment of LyP is unnecessary beyond basic wound care to avoid bacterial superinfection.2,10 Therapy for poikilodermatous MF, similar to other types of MF, is based on disease stage. Topical therapy may be utilized for localized disease, while systemic therapies are reserved for recalcitrant cases and internal involvement.9

Acknowledgments

We thank David L. Ramsay, MD, for obtaining aspects of the patient's history, and Shane A. Meehan, MD, and Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, as well as Cynthia M. Magro, MD, (all from New York, New York) for performing the histopathologic and immunohistochemical analyses.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis. a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Meena M, Martin PA, Abouseif C, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis type C of the eyelid in a young girl: a case report and review of literature. Orbit. 2014;3:395-398.

- Dinotta F, Lacarrubba F, Micali G. Sixteen-year-old girl with papules and nodules on the face and upper limbs. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:103-104.

- Eminger LA, Shinohara MM, Kim EJ, et al. Clinicopathologic challenge: acral lymphomatoid papulosis. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:531-534.

- Harder D, Kuhn A, Mahrle G. Lymphomatoid papulosis resembling ecthyma. a case report. Z Hautkr. 1989;64:593-595.

- Werner B, Massone C, Kerl H, et al. Large CD30-positive cells in benign, atypical lymphoid infiltrates of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1100-1107.

- Kunishige JH, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-581.

- Abbott RA, Sahni D, Robson A, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides: a study of its clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and prognostic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:313-319.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis. a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Meena M, Martin PA, Abouseif C, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis type C of the eyelid in a young girl: a case report and review of literature. Orbit. 2014;3:395-398.

- Dinotta F, Lacarrubba F, Micali G. Sixteen-year-old girl with papules and nodules on the face and upper limbs. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:103-104.

- Eminger LA, Shinohara MM, Kim EJ, et al. Clinicopathologic challenge: acral lymphomatoid papulosis. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:531-534.

- Harder D, Kuhn A, Mahrle G. Lymphomatoid papulosis resembling ecthyma. a case report. Z Hautkr. 1989;64:593-595.

- Werner B, Massone C, Kerl H, et al. Large CD30-positive cells in benign, atypical lymphoid infiltrates of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1100-1107.

- Kunishige JH, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-581.

- Abbott RA, Sahni D, Robson A, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides: a study of its clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and prognostic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:313-319.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

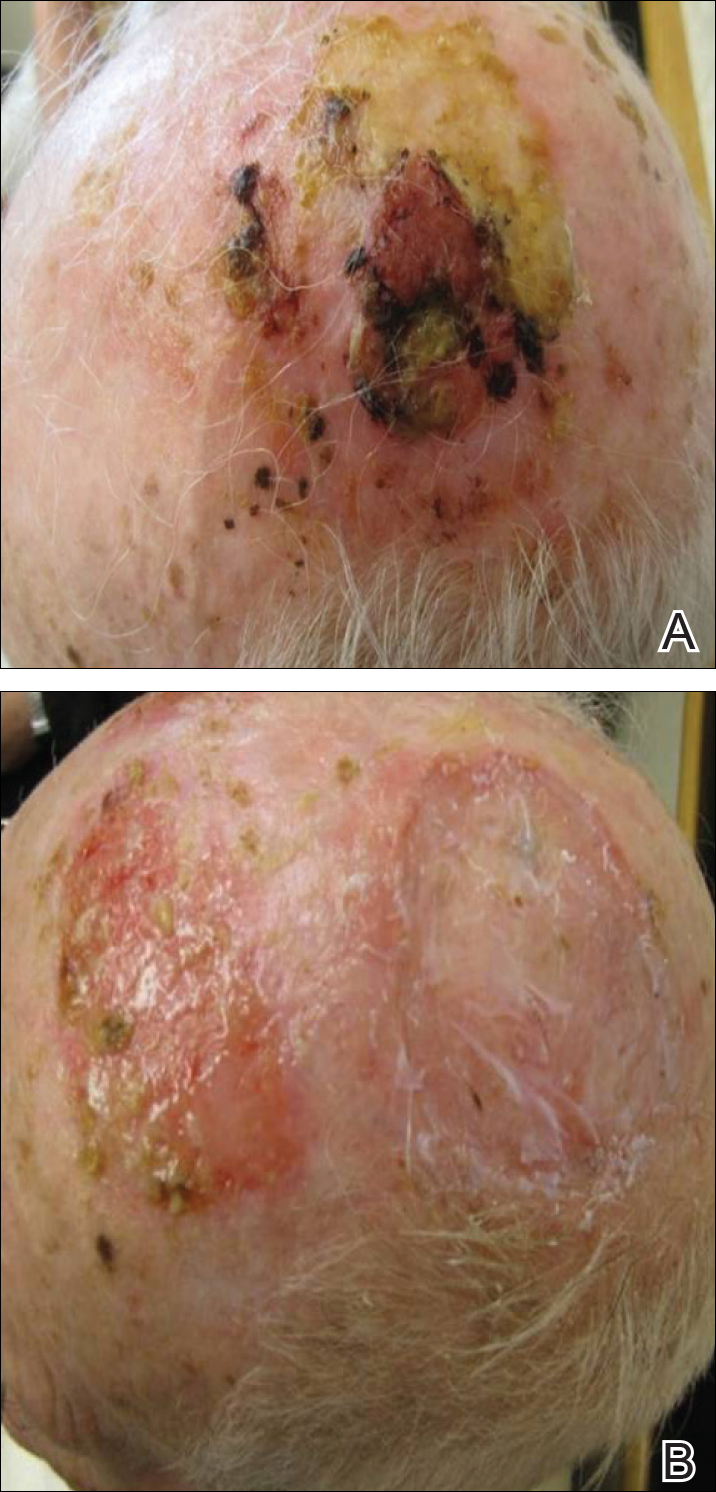

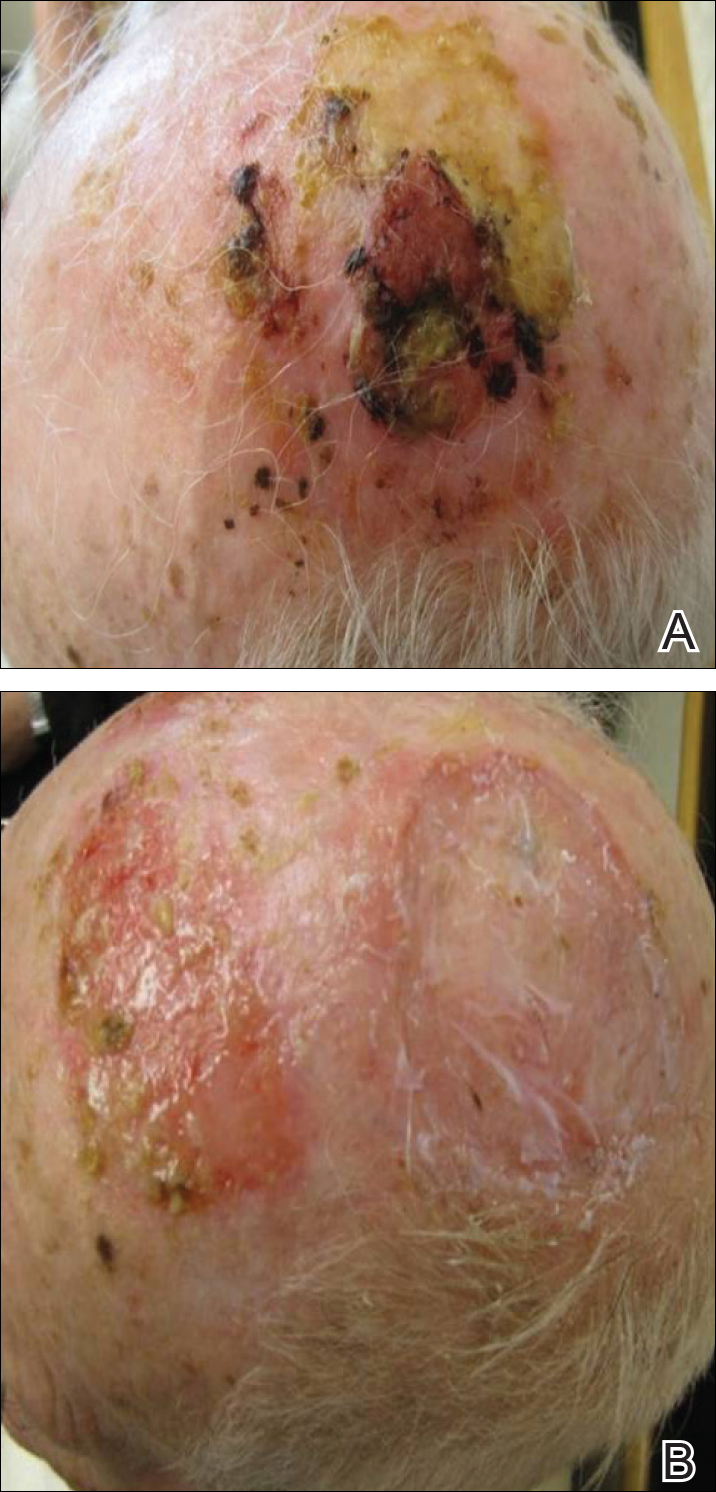

A 50-year-old woman presented for evaluation of black eschars on the face and body. Over the preceding 8 weeks she had developed several asymptomatic papules that gradually enlarged, ulcerated, and formed a black eschar, prior to gradually self-resolving over the course of several weeks. During this time, new lesions were forming. The resulting skin revealed dyspigmentation and scar formation. Prior to presentation, antimicrobial therapy had been initiated for a presumed infectious etiology; however, the eruption continued to progress. The patient denied sick contacts, livestock exposure, or recent travel. A complete review of systems, including fever, chills, or lymphadenopathy, was negative. Physical examination revealed 6 circular necrotic ulcers with an overlying black eschar on the face (top), trunk (bottom), hands, and thighs, all in various stages of healing. In addition, large, reticulated, poikilodermatous patches were incidentally noted in areas free of ulcers and eschars on the trunk (bottom) and bilateral arms and legs. Upon questioning, the patient said these patches had been present for more than 30 years. A punch biopsy from an ulcer on the chest was obtained and sent for histopathologic and immunohistochemical examination.

Chromoblastomycosis Infection From a House Plant

To the Editor:

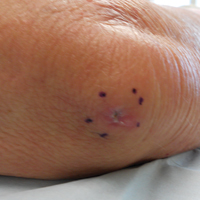

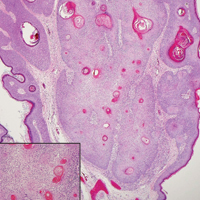

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

Practice Points

- Chromoblastomycosis is an uncommon fungal infection that should be considered in cases of traumatic injuries to the skin.

- Biopsies of growing or nonhealing nodules will demonstrate characteristic golden brown spherules (medlar bodies).

- In localized cases, surgical excision may be curative.

Verrucoid Lesion on the Eyelid

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

- Ruhoy SM, Thomas D, Nuovo GJ. Multiple inverted follicular keratoses as a presenting sign of Cowden's syndrome: case report with human papillomavirus studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:411-415.

- Lever WF. Inverted follicular keratosis is an irritated seborrheic keratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:474.

- Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, et al. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid may not be detected in non-genital benign papillomatous skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:334-338.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- Ogawa T, Kiuru M, Konia TH, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is usually associated with hair follicles, not acantholytic actinic keratosis, and is not "high risk": diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes in a series of 115 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:327-333.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Sano DT, Yang JJ, Tebcherani AJ, et al. A rare clinical presentation of desmoplastic trichilemmoma mimicking invasive carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:796-798.

- Stierman S, Chen S, Nuovo G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in trichilemmomas and verrucae using in situ hybridization. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:75-80.

- Ngeow J, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: clinical risk assessment and management protocol [published online October 22, 2014]. Methods. 2015;77-78:11-19.

- Molvi M, Sharma YK, Dash K. Cowden syndrome: case report, update and proposed diagnostic and surveillance routines. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:255-259.

- Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:637-640.

- Mehregan AH, Brownstein MH. Pilar sheath acanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1495-1497.

- Newland JR, Leventon GS. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:176-183.

- Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma--"follicular dyskeratoma": analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.