User login

Product News: 07 2017

Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40, a mineral-based formula for face and body with micronized zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octisalate. The lightweight formula is water resistant for up to 40 minutes and contains hyaluronic acid to nourish the skin and help boost natural moisture levels to visibly reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

proactivMD

The Proactiv Company launches the proactivMD Essentials System, a 3-step acne regimen that has been reformulated to include

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40, a mineral-based formula for face and body with micronized zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octisalate. The lightweight formula is water resistant for up to 40 minutes and contains hyaluronic acid to nourish the skin and help boost natural moisture levels to visibly reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

proactivMD

The Proactiv Company launches the proactivMD Essentials System, a 3-step acne regimen that has been reformulated to include

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces Glytone Sunscreen Lotion Broad Spectrum SPF 40, a mineral-based formula for face and body with micronized zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octisalate. The lightweight formula is water resistant for up to 40 minutes and contains hyaluronic acid to nourish the skin and help boost natural moisture levels to visibly reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles. For more information, visit www.glytone-usa.com.

proactivMD

The Proactiv Company launches the proactivMD Essentials System, a 3-step acne regimen that has been reformulated to include

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Metastatic Crohn Disease: A Review of Dermatologic Manifestations and Treatment

Almost half of Crohn disease (CD) patients experience a dermatologic manifestation of the disease. A rare entity, metastatic CD (MCD) presents a diagnostic challenge without a high index of suspicion. Its etiology is not well defined; however, it appears to be an autoimmune response to gut antigens. Herein, we review the etiology/epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, and treatment for this uncommon condition.

Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of MCD

Metastatic CD was first described by Parks et al1 in 1965 and refers to a diverse collection of macroscopic dermatologic manifestations in tissue not contiguous with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. To be classified as MCD, the tissue must demonstrate characteristic histopathologic findings, which invariably include noncaseating granulomas.

Crohn disease may affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to anus, with a multitude of associated cutaneous manifestations having been described. The terminal ileum is the most commonly affected portion of the GI tract in CD, but the large intestine also may be involved in 55% to 80% of cases.2 The incidence of non-MCD-associated anal lesions seems to correlate with intestinal involvement in that as few as 25% of patients with ileal-localized CD have anal lesions compared to nearly 80% of patients with large intestinal involvement.3

It has been estimated that 18% to 44% of patients with CD have some form of cutaneous manifestation,4 with MCD being a rare subcategory. As few as 100 cases have been described from 1965 to the present.5 The presence of MCD does not correlate well with severity of intestinal CD, and although a majority of MCD cases present after at least 6 months of GI symptoms,6 there are instances in which MCD presents without prior or existing evidence of intestinal CD.7

With regard to MCD, the term metastatic is sometimes supplanted in the literature by cutaneous to avoid any implication of cancer; however, due to a myriad of dermatologic manifestations, both terms can cause confusion. The categorization of the various types of cutaneous findings in CD is well summarized in a review by Palamaras et al8 with the following classifications: (1) granulomatous by direct extension (oral or perianal), (2) MCD lesions (genital and nongenital), (3) immune-related lesions, and (4) lesions from nutritional deficiencies. Of the cutaneous manifestations relating to CD, MCD is the least common cutaneous categorical manifestation and is further divided into subcategories of genital and nongenital lesions.8

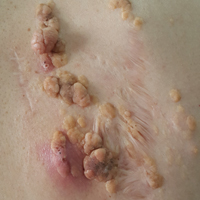

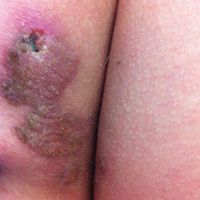

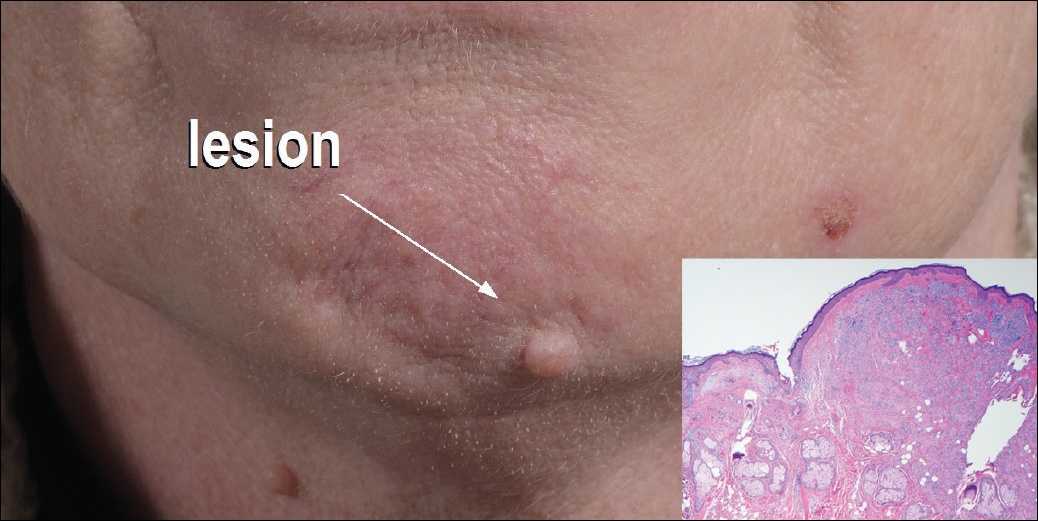

The nongenital distribution of MCD is the more common variety in adults and particularly seems to affect the legs and plantar surfaces (38%), the trunk and abdomen (24%), and the face (15%).5,9 These nongenital MCD manifestations are most commonly described as nodules, ulcerations, or erythematous to purple plaques, and less commonly described as abscesses, pustules, or papules.

The sequence of cutaneous symptoms of MCD relative to intestinal disease depends to some degree on patient age. In adults diagnosed with MCD, it has been noted that a GI flare is expected 2 months to 4 years after diagnosis; however, in children the subsequent GI flare has been noted to vary more widely from 9 months to 14 years following presentation of MCD.8 Furthermore, roughly 50% of children diagnosed with MCD present concomitantly with their first symptoms of a GI flare, whereas 70% of adults with MCD had been previously diagnosed with intestinal CD.8 In one review of 80 reported cases of MCD, 20% (16/80) had no symptoms of intestinal disease at the time of MCD diagnosis, and the majority of the asymptomatic cases were in children; interestingly, the majority of these same children were diagnosed with CD months to years later.9

Both the location and characteristics of cutaneous findings in MCD correlate with age.9 Metastatic CD has been identified in all age groups; however, lymphedema is more common in children/young adults, while nodules, ulceration, and fistulating disease are more often seen in adults.10 Affected children and adolescents with MCD range from 5 to 17 years of age, with a mean age at disease onset of 11.1 years and equal incidence in males and females.8 Adults with MCD range from 18 to 78 years of age, with a mean age at presentation of 38.4 years.8,11

Concerning anatomic location of disease, adults with MCD most commonly have nodules with or without plaques on the arms and legs and less commonly in the genital area.8 In contrast, children with MCD are more prone to genital lesions, with up to 85% of cases including some degree of genital erythematous or nonerythematous swelling with or without induration.8 Genitourinary complications of CD as a broad category, however, are estimated to occur in only 5% to 20% of intestinal CD cases in both children and adults.12

There have been conflicting reports regarding gender predilection in MCD. Based on a review by Samitz et al13 of 200 cases of CD over an 18-year period, 22% of patients with CD were found to have cutaneous manifestations--presumably not MCD but rather perianal, perineal, vulvar fistulae, fissures, or abscesses--with a male to female preponderance of almost 2 to 1. A more recent review of the literature by Palamaras et al8 in 2008 reported that contiguous non-MCD affects adult females and children more often than adult males, with 63% adult cases being female. This review seems to be more congruent with other reports in the literature implicating that females are twice as commonly affected by MCD than males.9,14

Pathophysiology

The etiology of MCD has not been well defined. One proposed mechanism of the distal tissue involvement of MCD is through passage of antigens to the skin with subsequent granulomatous response at the level of the dermis.10 Another proposed mechanism suggests antibody sensitization to gut antigens, possibly bacterial antigens, that then coincidentally cross-react with analogous skin antigens.8,14 Burgdorf11 supported this notion in a 1981 report in which it was suggested that the granulomatous reaction was related to deposition of immune complexes in the skin. Slater et al15 and Tatnall et al16 offered a variation of Burgdorf's notion, suggesting that it was sensitized T cells to circulating antigens that were the initiators of granuloma formation in the periphery.

An examination of MCD tissue in 1990 by Shum and Guenther17 under electron microscopy and immunofluorescence provided evidence against prior studies that purported to have identified immune complexes as the causative agents of MCD. In this study, the authors found no evidence of immune complexes in the dermis of MCD lesions. In addition, an attempt to react serum antibodies of a patient with MCD, which were postulated to have IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies to specific gut antigens, yielded no response when reacted with the tongue, ileum, and colon tissue from a rat. As a culminant finding, the authors also noted MCD dermis tissue with granulomas without vasculitis, suggesting a T-cell mediated type IV hypersensitivity response with a secondary vasculitis from T-cell origin lymphokines and T-cell mediated monocyte activation.17

Research implicating other immunologic entities involved in the pathophysiology of CD such as β-2 integrin,18 CD14+ monocytes,19 and the role of the DNA repair gene MLH1 (mutL homolog 1)20 have been considered but without a clearly definitive role in the manifestations of MCD.

The utility of metronidazole in the treatment of MCD has been suggested as evidence that certain bacteria in the gut may either serve as the causative antigen or may induce its formation21; however, the causative antigen has yet to be identified, and whether it travels distally to the skin or merely resembles a similar antigen normally present in the dermis has not yet been determined. Some research has used in situ polymerase chain reaction techniques to attempt to detect similar microbial pathogens in both the vasculature of active bowel lesions and in the skin, but to date, bacterial RNA noted to be present in the gut vasculature adjacent to CD lesions has not been detected in skin lesions.22

Diagnosis

Physical Findings

Overall, it is estimated that roughly 56% of all MCD cases affect the external genitalia.23 The classic appearance of MCD includes well-demarcated ulcerations in the areas of intertriginous skin folds with or without diffuse edema and tenderness to palpation.23 Although MCD has been historically noted as having a predilection for moist skin folds, there are numerous case reports of MCD all over the body, including the face,7,24-29 retroauricular areas,30 arms and legs,16,17,31-34 lower abdomen,3,5 under the breasts,1 perineum,35 external genitalia,1,9,36-40 and even the lungs41 and bladder.42

As a dermatologic disease, MCD has been referred to as yet another great imitator, both on the macroscopic and microscopic levels.8 As such, more common causes of genital edema should be considered first and investigated based on the patient's history, physical examination, skin biopsy, lymphangiogram, ultrasound, and cystogram.43 Ultrasonography and color Doppler sonography have been shown to be helpful in patients with genital involvement. This modality can evaluate not only the presence of normal testes but also intratesticular and scrotal wall fluid, especially when the physical examination reveals swelling that makes testicle palpation more difficult.6 Clinically, the correct diagnosis of MCD often is made through suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease based on classic symptoms and/or physical findings including abdominal pain, weight loss, bloody stool, diarrhea, perianal skin tags, and anal fissures or fistulas. Any of these GI findings should prompt an intestinal biopsy to rule out any histologic evidence of CD.

Metastatic CD affecting the vulva often presents with vulvar pain and pruritus and may clinically mimic a more benign disease such as balanitis plasmacellularis, also referred to as Zoon vulvitis.23 Similar to MCD on any given body surface, there is dramatic variation in the macroscopic presentation of vulvar MCD, with physical examination findings ranging from bilateral diffuse, edematous, deeply macerated, red, ulcerated lesions over the vulva with lymphadenopathy to findings of bilateral vulvar pain with yellow drainage from the labia majora.23 There have been cases of vulvar MCD that include exquisite vulvar pain but without structural abnormalities including normal uterus, cervix, adnexa, rectovaginal septum, and rectum. In these more nebulous cases of vulvar MCD, the diagnosis often is discovered incidentally when nonspecific diagnostic imaging suggests underlying CD.23

Beyond the case-by-case variations on physical examination, the great difficulty in diagnosis, particularly in children, occurs in the absence of any GI symptoms and therefore no logical consideration of underlying CD. Consequently, there have been cases of children presenting with irritation of the vulva who were eventually diagnosed with MCD only after erroneous treatment of contact dermatitis, candidiasis, and even consideration of sexual abuse.37 Because it is so rare and obscure among practicing clinicians, the diagnosis of MCD often is considered only after irritation or swelling of the external genitalia has not responded to standard therapies. If and when the diagnosis of MCD is considered in children, it has been suggested to screen patients for anorectal stricture, as case studies have found the condition to be relatively common in this subpopulation.44

In the less common case of adults with genitourinary symptoms that suggest possible MCD, the differential diagnosis for penile or vaginal ulcers should include contact and irritant dermatitis, chronic infectious lesions (eg, hidradenitis suppurativa, actinomycosis, tuberculosis),45 sexually transmitted ulcerative diseases (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes genitalia, granuloma inguinale),46 drug reactions, and even extramammary Paget disease.47

Histologic Findings

Because MCD has so much macroscopic variation and can present anywhere on the surface of the body, formal diagnosis relies on microscopy. As an added measure of difficulty in diagnosis, one random biopsy of a suspicious segment of tissue may not contain the expected histologic findings; therefore, clinical suspicion may warrant a second biopsy.10 There have been reported cases of an adult patient without history of CD presenting with a lesion that resembled a more common pathology, such as a genital wart, and the correct diagnosis of MCD with pseudocondylomatous morphology was made only after intestinal manifestations prompted the clinician to consider such an unusual diagnosis.48

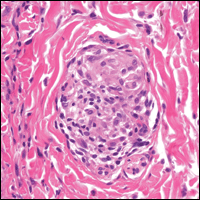

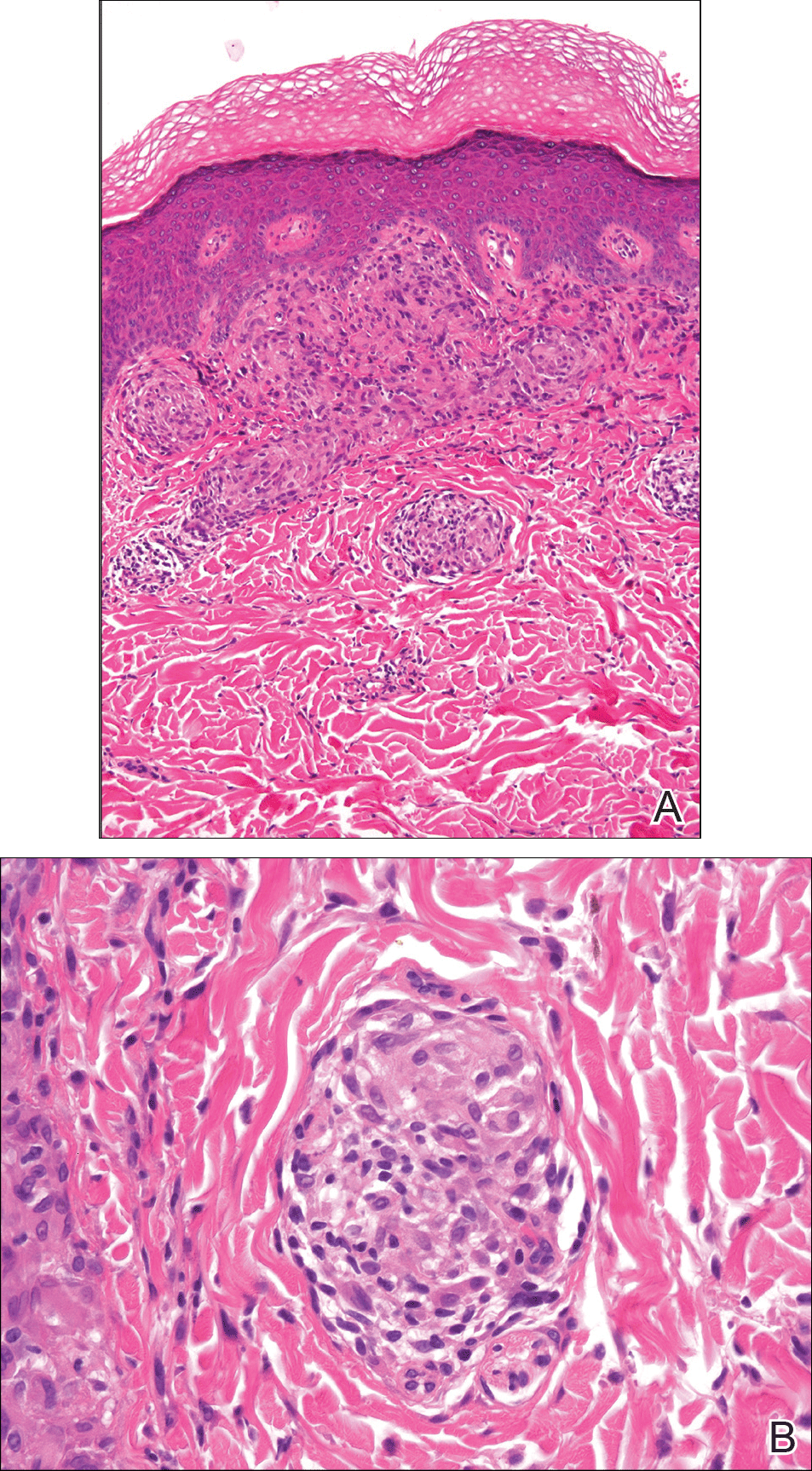

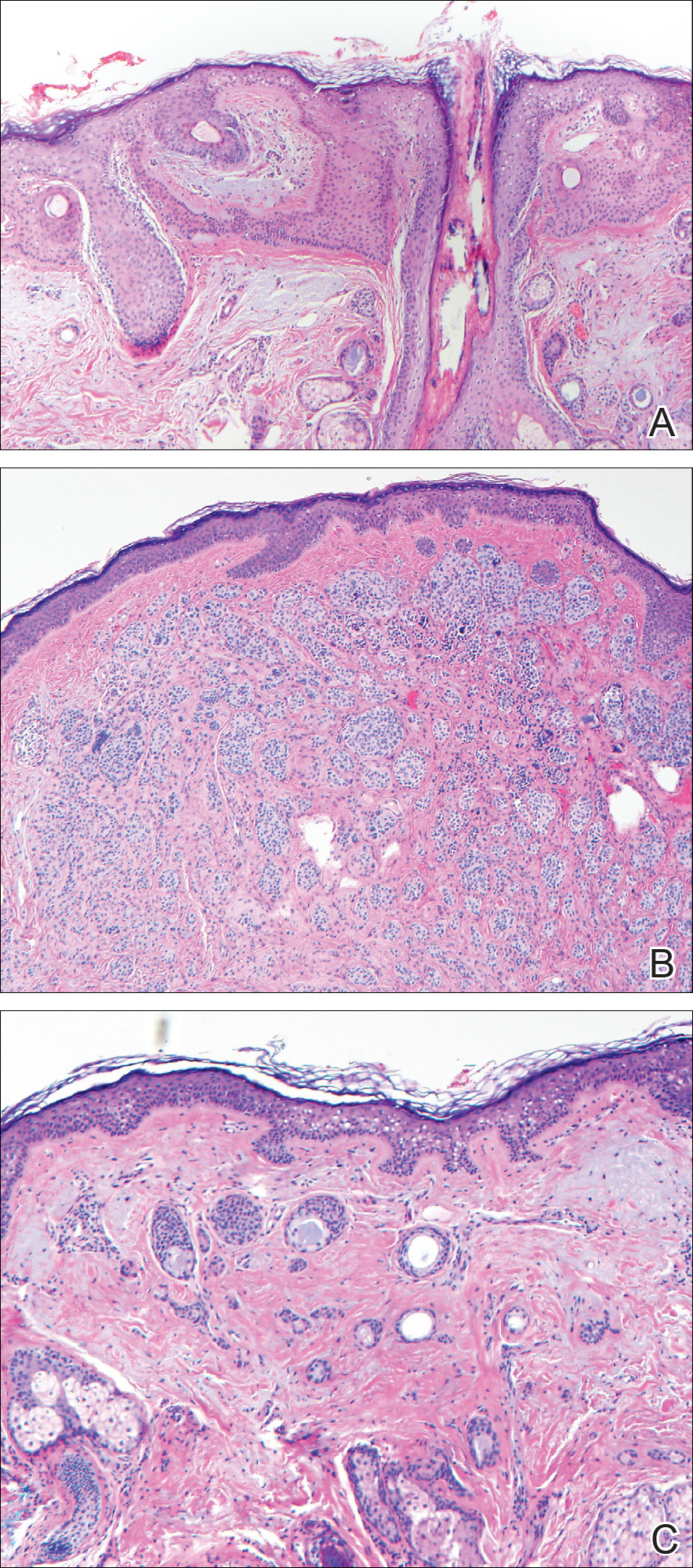

From a histopathologic perspective, MCD is characterized by discrete, noncaseating, sarcoidlike granulomas with abundant multinucleated giant cells (Langhans giant cells) in the superficial dermis (papillary), deep dermis (reticular), and adipose tissue (Figure).8,17 In the presence of concomitant intestinal disease, the granulomas of both the intestinal and dermal tissues should share the same microscopic characteristics.8 In addition, copious neutrophils and granulomas surrounding the microvasculature have been described,34 as well as general lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrate.45 Some histologic samples have included collagen degeneration termed necrobiosis in the middle dermal layer as another variable finding in MCD.14,34

On microscopy, it has been reported that use of Verhoeff-van Gieson staining may be helpful to highlight the presence of neutrophil obstruction within the dermal vasculature, particularly the arterial lumen, as well as to aid in highlighting swelling of the endothelium with fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina.17 Although not part of the routine diagnosis, electron microscopy of MCD tissue samples have confirmed hypertrophy of the endothelial cells composing the capillaries with resulting extravasation of fibrin, red blood cells, lymphocytes, and epithelioid histiocytes.17 Observation of tissue under direct immunofluorescence has been less helpful, as it has shown only nonspecific fibrinogen deposition within the dermis and dermal vessels.17

In an article on treatment of MCD, Escher et al43 reinforced that the macroscopic findings of MCD are diverse, and the microscopic findings characteristic of MCD also can be mimicked by other etiologies such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, fungal infections, lymphogranuloma venereum, leishmaniasis, and connective tissue disorders.43 As such, the workup to rule out infectious, anatomic, and autoimmune etiologies should be diverse. Often, the workup for MCD will include special stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen stain to rule out Mycobacterium tuberculosis and acid-fast bacilli and Fite stain to consider atypical mycobacteria. Other tests such as tissue culture, chest radiograph, tuberculin skin test (Mantoux test), IFN-γ release assay, or polarized light microscopy may rule out infectious etiologies.9,49 Serologic testing might include VDRL test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus.5

Crohn disease is characterized histologically by sarcoidlike noncaseating granulomas, and as such, it is important to differentiate MCD from sarcoidosis prior to histologic analysis. Sarcoidosis also can be considered much less likely with a normal chest radiograph and in the absence of increased serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels.7 The differentiation of sarcoidosis from MCD on the microscopic scale is subtle but is sometimes facilitated in the presence of an ulcerated epidermis or lymphocytic/eosinophilic infiltrate and edema within the dermis, all suggestive of MCD.14

Metastatic CD also should be differentiated from erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, which are among the most common cutaneous findings associated with CD.14 Pyoderma gangrenosum can be distinguished histologically by identifying copious neutrophilic infiltrate with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.50

Treatment

Because MCD is relatively rare, there are no known randomized trials suggesting a particular medical or surgical treatment. In a review of perineal MCD from 2007, the 40-year-old recommendation by Moutain3 opting for surgical debridement versus medical management still resonates, particularly for perineal disease, as an effective measure in all but the mildest of presentations.51 However, recent case reports also suggest that the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors such as infliximab and adalimumab should be considered prior to surgery even with severe perineal MCD.51 Moreover, even if medical management with TNF-α inhibitors or some combination of immunosuppressants and antibiotics does not eradicate the disease, it often helps reduce the size of the ulcers prior to surgery.52 With a limited understanding of MCD, one might think that removal of the affected bowel would eliminate cutaneous disease, but it has been shown that this strategy is not effective.53,54

The composition and location of the particular lesion affects the trajectory of treatment. For example, MCD manifesting as local ulcers and plaques has been described as responding well to topical and intralesional steroids.10,55,56 In the case of penile swelling and/or phimosis, circumcision has been helpful to improve the patient's ability to void as well as to attain and maintain erection.10 In the case of scrotal swelling secondary to MCD, early treatment (ie, within 4 to 6 months) with oral steroids and/or metronidazole is likely beneficial to prevent refractory edematous organization of the tissue.57

As a general rule, an effective treatment will include a combination of an immunosuppressant, antibiotic therapy, and sometimes surgery. The most commonly used immunosuppressant agents include topical or intralesional steroids, infliximab,43,58 cyclosporine A,59,60 dapsone, minocycline, thalidomide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, tacrolimus, and 6-mercaptopurine.4 Steroids have been the conventional treatment of extraintestinal manifestations of CD61; however, perineal CD has been poorly controlled with systemic steroids.62 If steroids are found not to be effective, sometimes agents such as dapsone or thalidomide are considered. One case report noted stabilization of MCD penile ulcers with oral thalidomide 300 mg once daily, oral minocycline 100 mg once daily, and topical tacrolimus 0.3% with benzocaine twice daily with continuation of prednisolone and methotrexate as parts of previously unsuccessful regimen.52

Metronidazole is perhaps the most commonly used antibiotic, having been a component of many successful regimens.4,63 For example, a 27-year-old patient with MCD presenting as a nonhealing ulcerative lesion in the subcoronal area of the penis and scrotum was treated successfully with a 6-month course of mesalamine, prednisone, and metronidazole.45 Another case report of vulvar MCD reported initial success with intravenous methylprednisolone, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole.23 The primary limitation of metronidazole is that subsequent tapering of the dose seems to result in recurrence of disease.64 Consequently, patients must remain on the antibiotic for an indeterminate course, with dosages ranging from 5 mg/kg daily in adolescents65 to 1000 to 1500 mg daily in adults.66

Of the various immunosuppressants available, infliximab has been listed in numerous reports as a successful agent in both the induction and maintenance of extraintestinal manifestations of CD including MCD.67-71 Infliximab has been reported to be effective in the treatment of penile and scrotal edema secondary to MCD that did not respond to other immunosuppressants including oral prednisolone, azathioprine, and cyclosporine.43 Infliximab may be a good option to help heal draining fistulas, particularly in combination with an antibiotic such as metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, which helps to prevent abscess formation during healing.72 The response to infliximab has been dramatic, with resolution of cutaneous lesions after just 6 weeks in some cases.73 The dosing regimen of infliximab has been suggested at 5 mg/kg administered at 0, 2, and 6 weeks, with subsequent maintenance infusions every 10 weeks,70 or at 0, 4, and 12 weeks, with subsequent infusions every 8 weeks.43

Adalimumab may be considered as an alternative to infliximab and is potentially less allergenic as a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, which also has been used successfully to both induce and maintain remission of moderate to severe CD.42,74,75 Proposed dosing of adalimumab includes a loading dose of 160 mg subcutaneously on day 1, followed by an 80-mg dose 2 weeks later and a 40-mg maintenance dose every other week indefinitely.48 Of note, adalimumab has been noted in the literature to have many potential side effects, including one particular case in which severe headaches were attributed to its use.59 As a consequence of the headaches, the patient was switched from adalimumab to cyclosporine and responded well with no subsequent flare-ups on follow-up.

In summary, treatment of MCD depends on cutaneous location, severity, physician experience with certain antibiotics or immunosuppressants, availability of medication, and patient disposition. It seems reasonable to attempt medical management with one or more medical regimens before committing to surgical intervention. Furthermore, even with debridement, curettage, skin graft, or other surgical strategy, the patient is likely to require some period of immunosuppression to provide long-lasting remission.

Conclusion

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease often develop dermatologic sequelae, with MCD being a rare but serious process. Patients may present with a wide array of physical concerns and symptoms, many resembling other disease processes. As such, education and a high index of suspicion are needed for proper diagnosis and treatment.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Friedman S, Blumber RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al, eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1778-1784.

- Moutain JC. Cutaneous ulceration in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1970;11:18-26.

- Lester LU, Rapini RP. Dermatologic manifestations of colonic disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;25:66-73.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Simoneaux SF, Ball TI, Atkinson GO Jr. Scrotal swelling: unusual first presentation of Crohn's disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:375-376.

- Albuquerque A, Magro F, Rodrigues S, et al. Metastatic cutaneous Crohn's disease of the face: a case report and review of literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:954-956.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Ploysangam T, Heubi JE, Eisen D, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:697-704.

- Vint R, Husain E, Hassain F, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the penis: two cases. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:45-49.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Resnick MI, Kursh ED. Extrinsic obstruction of the ureter. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Stamey TA, et al, eds. Campbell's Urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1998:400-402.

- Samitz MH, Dana AS Jr, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease--review of statistics of skin complications. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a histo-pathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:457-461.

- Slater DN, Waller PC, Reilly G. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis: presenting features of Crohn's disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:589-590.

- Tatnall FM, Dodd HJ, Sarkany I. Crohn's disease with metastatic cutaneous involvement and granulomatous cheilitis. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:49-51.

- Shum DT, Guenther L. Metastatic Crohn's disease: case report and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:645-648.

- Bernstein CN, Sargent M, Gallatin WM. Beta2 integrin/ICAM expression in Crohn's disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;86:147-160.

- Grimm MC, Pavli P, Van de Pol E, et al. Evidence for a CD-14+ population of monocytes in inflammatory bowel disease mucosa--implications for pathogenesis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:291-297.

- Pokorny RM, Hofmeister A, Galandiuk S, et al. Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with the DNA repair gene MLH1. Ann Surg. 1997;225:718-723; discussion 723-725.

- Ursing B, Kamme C. Metronidazole for Crohn's disease. Lancet. 1975;1:775-777.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn's disease, its spectrum, and pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn's disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185.

- Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, et al. Clinical spectrum of vulva metastatic Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1565-1571.

- Chen W, Blume-Peytavi U, Goerdt S, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:986-988.

- Ogram AE, Sobanko JF, Nigra TP. Metastatic cutaneous Crohn disease of the face: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:25-27.

- Graham D, Jager D, Borum M. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the face. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2062-2063.

- Biancone L, Geboes K, Spagnoli LG, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the forehead. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:101-105.

- Kolansky G, Green CK, Dubin H. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the face: an uncommon presentation. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1348-1349.

- Mahadevan U, Sandborn WJ. Infliximab for the treatment of orofacial Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:38-42.

- McCallum DI, Gray WM. Metastatic Crohn's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:551-554.

- Lieberman TR, Greene JF Jr. Transient subcutaneous granulomatosis of the upper extremities in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72:89-91.

- Kafity AA, Pellegrini AE, Fromkes JJ. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a rare cutaneous manifestation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:300-303.

- Marotta PJ, Reynolds RP. Metastatic Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:373-375.

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn's disease. report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:928-932.

- van Dulleman HM, de Jong E, Slors F, et al. Treatment of therapy resistant perineal metastatic Crohn's disease after proctectomy using anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody, cA2: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:98-102.

- Lavery HA, Pinkerton JH, Sloan J. Crohn's disease of the vulva--two further cases. Br J Dermatol. 1985;113:359-363.

- Lally MR, Orenstein SR, Cohen BA. Crohn's disease of the vulva in an 8-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 1988;5:103-106.

- Tuffnell D, Buchan PC. Crohn's disease of the vulva in childhood. Br J Clin Pract. 1991;45:159-160.

- Schrodt BJ, Callen JP. Metastatic Crohn's disease presenting as chronic perivulvar and perirectal ulcerations in an adolescent patient. Pediatrics. 1999;103:500-502.

- Slaney G, Muller S, Clay J, et al. Crohn's disease involving the penis. Gut. 1986;27:329-333.

- Calder CJ, Lacy D, Raafat F, et al. Crohn's disease with pulmonary involvement in a 3 year old boy. Gut. 1993;34:1636-1638.

- Saha S, Fichera A, Bales G, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the bladder. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:140-142.

- Escher JC, Stoof TJ, van Deventer SJ, et al. Successful treatment of metastatic Crohn disease with infliximab. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:420-423.

- Saadah OI, Oliver MR, Bines JE, et al. Anorectal strictures and genital Crohn's disease: an unusual clinical association. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:403-406.

- Martinez-Salamanca JI, Jara J, Miralles P, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: penile and scrotal involvement. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38:436-437.

- Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417-429.

- Acker SM, Sahn EE, Rogers HC, et al. Genital cutaneous Crohn disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:443-446.

- Lestre S, Ramos J, Joao A, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease presenting as genital warts: successful treatment with adalimumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:504-505.

- Yu JT, Chong LY, Lee KC. Metastatic Crohn's disease in a Chinese girl. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:467-469.

- Wilson-Jones E, Winkelmann RK. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma: a localized vegetative form of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:511-521.

- Moyes LH, Glen P, Pickford IR. Perineal metastatic Crohn's disease: a case report and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:W1-W3.

- Rajpara SM, Siddha SK, Ormerod AD, et al. Cutaneous penile and perianal Crohn's disease treated with a combination of medical and surgical interventions. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:21-24.

- Cockburn AG, Krolikowski J, Balogh K, et al. Crohn disease of penile and scrotal skin. Urology. 1980;15:596-598.

- Guest GD, Fink RL. Metastatic Crohn's disease: case report of an unusual variant and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1764-1766.

- Sangueza OP, Davis LS, Gourdin FW. Metastatic Crohn disease. South Med J. 1997;90:897-900.

- Chiba M, Iizuka M, Horie Y, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease involving the penis. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:817-821.

- Poon KS, Gilks CB, Masterson JS. Metastatic Crohn's disease involving the genitalia. J Urol. 2002;167:2541-2542.

- Shanahan F. Anti-TNF therapy for Crohn's disease: a perspective (infliximab is not the drug we have been waiting for). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:137-139.

- Carranza DC, Young L. Successful treatment of metastatic Crohn's disease with cyclosporine. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:789-791.

- Bardazzi F, Guidetti MS, Passarini B, et al. Cyclosporine A in metastatic Crohn's disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:324-325.

- Faubion WA Jr, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255-260.

- Gelbmann CM, Rogler G, Gross V, et al. Prior bowel resections, perianal disease, and a high initial Crohn's disease activity index are associated with corticosteroid resistance in active Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1438-1445.

- Thukral C, Travassos WJ, Peppercorn MA. The role of antibiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2005;8:223-228.

- Brandt LJ, Berstein LH, Boley SJ, et al. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn's disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:383-387.

- Lehrnbecher T, Kontny HU, Jeschke R. Metastatic Crohn's disease in a 9-year-old boy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:321-323.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

- Rispo A, Scarpa R, Di Girolamo E, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of extra-intestinal manifestations of Crohn's disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:387-391.

- Kaufman I, Caspi D, Yeshurun D, et al. The effect of infliximab on extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:406-410.

- Konrad A, Seibold F. Response of cutaneous Crohn's disease to infliximab and methotrexate. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:351-356.

- Miller AM, Elliott PR, Fink R, et al. Rapid response of severe refractory metastatic Crohn's disease to infliximab. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:940-942.

- Chuah JH, Kim DS, Allen C, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease of the ear. Int J Otolaryngol. 2009;2009:871567.

- Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405.

- Petrolati A, Altavilla N, Cipolla R, et al. Cutaneous metastatic Crohn's disease responsive to infliximab. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1058.

- Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn's disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323-333.

- Cury DB, Moss A, Elias G, et al. Adalimumab for cutaneous metastatic Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:723-724.

Almost half of Crohn disease (CD) patients experience a dermatologic manifestation of the disease. A rare entity, metastatic CD (MCD) presents a diagnostic challenge without a high index of suspicion. Its etiology is not well defined; however, it appears to be an autoimmune response to gut antigens. Herein, we review the etiology/epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, and treatment for this uncommon condition.

Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of MCD

Metastatic CD was first described by Parks et al1 in 1965 and refers to a diverse collection of macroscopic dermatologic manifestations in tissue not contiguous with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. To be classified as MCD, the tissue must demonstrate characteristic histopathologic findings, which invariably include noncaseating granulomas.

Crohn disease may affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to anus, with a multitude of associated cutaneous manifestations having been described. The terminal ileum is the most commonly affected portion of the GI tract in CD, but the large intestine also may be involved in 55% to 80% of cases.2 The incidence of non-MCD-associated anal lesions seems to correlate with intestinal involvement in that as few as 25% of patients with ileal-localized CD have anal lesions compared to nearly 80% of patients with large intestinal involvement.3

It has been estimated that 18% to 44% of patients with CD have some form of cutaneous manifestation,4 with MCD being a rare subcategory. As few as 100 cases have been described from 1965 to the present.5 The presence of MCD does not correlate well with severity of intestinal CD, and although a majority of MCD cases present after at least 6 months of GI symptoms,6 there are instances in which MCD presents without prior or existing evidence of intestinal CD.7

With regard to MCD, the term metastatic is sometimes supplanted in the literature by cutaneous to avoid any implication of cancer; however, due to a myriad of dermatologic manifestations, both terms can cause confusion. The categorization of the various types of cutaneous findings in CD is well summarized in a review by Palamaras et al8 with the following classifications: (1) granulomatous by direct extension (oral or perianal), (2) MCD lesions (genital and nongenital), (3) immune-related lesions, and (4) lesions from nutritional deficiencies. Of the cutaneous manifestations relating to CD, MCD is the least common cutaneous categorical manifestation and is further divided into subcategories of genital and nongenital lesions.8

The nongenital distribution of MCD is the more common variety in adults and particularly seems to affect the legs and plantar surfaces (38%), the trunk and abdomen (24%), and the face (15%).5,9 These nongenital MCD manifestations are most commonly described as nodules, ulcerations, or erythematous to purple plaques, and less commonly described as abscesses, pustules, or papules.

The sequence of cutaneous symptoms of MCD relative to intestinal disease depends to some degree on patient age. In adults diagnosed with MCD, it has been noted that a GI flare is expected 2 months to 4 years after diagnosis; however, in children the subsequent GI flare has been noted to vary more widely from 9 months to 14 years following presentation of MCD.8 Furthermore, roughly 50% of children diagnosed with MCD present concomitantly with their first symptoms of a GI flare, whereas 70% of adults with MCD had been previously diagnosed with intestinal CD.8 In one review of 80 reported cases of MCD, 20% (16/80) had no symptoms of intestinal disease at the time of MCD diagnosis, and the majority of the asymptomatic cases were in children; interestingly, the majority of these same children were diagnosed with CD months to years later.9

Both the location and characteristics of cutaneous findings in MCD correlate with age.9 Metastatic CD has been identified in all age groups; however, lymphedema is more common in children/young adults, while nodules, ulceration, and fistulating disease are more often seen in adults.10 Affected children and adolescents with MCD range from 5 to 17 years of age, with a mean age at disease onset of 11.1 years and equal incidence in males and females.8 Adults with MCD range from 18 to 78 years of age, with a mean age at presentation of 38.4 years.8,11

Concerning anatomic location of disease, adults with MCD most commonly have nodules with or without plaques on the arms and legs and less commonly in the genital area.8 In contrast, children with MCD are more prone to genital lesions, with up to 85% of cases including some degree of genital erythematous or nonerythematous swelling with or without induration.8 Genitourinary complications of CD as a broad category, however, are estimated to occur in only 5% to 20% of intestinal CD cases in both children and adults.12

There have been conflicting reports regarding gender predilection in MCD. Based on a review by Samitz et al13 of 200 cases of CD over an 18-year period, 22% of patients with CD were found to have cutaneous manifestations--presumably not MCD but rather perianal, perineal, vulvar fistulae, fissures, or abscesses--with a male to female preponderance of almost 2 to 1. A more recent review of the literature by Palamaras et al8 in 2008 reported that contiguous non-MCD affects adult females and children more often than adult males, with 63% adult cases being female. This review seems to be more congruent with other reports in the literature implicating that females are twice as commonly affected by MCD than males.9,14

Pathophysiology

The etiology of MCD has not been well defined. One proposed mechanism of the distal tissue involvement of MCD is through passage of antigens to the skin with subsequent granulomatous response at the level of the dermis.10 Another proposed mechanism suggests antibody sensitization to gut antigens, possibly bacterial antigens, that then coincidentally cross-react with analogous skin antigens.8,14 Burgdorf11 supported this notion in a 1981 report in which it was suggested that the granulomatous reaction was related to deposition of immune complexes in the skin. Slater et al15 and Tatnall et al16 offered a variation of Burgdorf's notion, suggesting that it was sensitized T cells to circulating antigens that were the initiators of granuloma formation in the periphery.

An examination of MCD tissue in 1990 by Shum and Guenther17 under electron microscopy and immunofluorescence provided evidence against prior studies that purported to have identified immune complexes as the causative agents of MCD. In this study, the authors found no evidence of immune complexes in the dermis of MCD lesions. In addition, an attempt to react serum antibodies of a patient with MCD, which were postulated to have IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies to specific gut antigens, yielded no response when reacted with the tongue, ileum, and colon tissue from a rat. As a culminant finding, the authors also noted MCD dermis tissue with granulomas without vasculitis, suggesting a T-cell mediated type IV hypersensitivity response with a secondary vasculitis from T-cell origin lymphokines and T-cell mediated monocyte activation.17

Research implicating other immunologic entities involved in the pathophysiology of CD such as β-2 integrin,18 CD14+ monocytes,19 and the role of the DNA repair gene MLH1 (mutL homolog 1)20 have been considered but without a clearly definitive role in the manifestations of MCD.

The utility of metronidazole in the treatment of MCD has been suggested as evidence that certain bacteria in the gut may either serve as the causative antigen or may induce its formation21; however, the causative antigen has yet to be identified, and whether it travels distally to the skin or merely resembles a similar antigen normally present in the dermis has not yet been determined. Some research has used in situ polymerase chain reaction techniques to attempt to detect similar microbial pathogens in both the vasculature of active bowel lesions and in the skin, but to date, bacterial RNA noted to be present in the gut vasculature adjacent to CD lesions has not been detected in skin lesions.22

Diagnosis

Physical Findings

Overall, it is estimated that roughly 56% of all MCD cases affect the external genitalia.23 The classic appearance of MCD includes well-demarcated ulcerations in the areas of intertriginous skin folds with or without diffuse edema and tenderness to palpation.23 Although MCD has been historically noted as having a predilection for moist skin folds, there are numerous case reports of MCD all over the body, including the face,7,24-29 retroauricular areas,30 arms and legs,16,17,31-34 lower abdomen,3,5 under the breasts,1 perineum,35 external genitalia,1,9,36-40 and even the lungs41 and bladder.42

As a dermatologic disease, MCD has been referred to as yet another great imitator, both on the macroscopic and microscopic levels.8 As such, more common causes of genital edema should be considered first and investigated based on the patient's history, physical examination, skin biopsy, lymphangiogram, ultrasound, and cystogram.43 Ultrasonography and color Doppler sonography have been shown to be helpful in patients with genital involvement. This modality can evaluate not only the presence of normal testes but also intratesticular and scrotal wall fluid, especially when the physical examination reveals swelling that makes testicle palpation more difficult.6 Clinically, the correct diagnosis of MCD often is made through suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease based on classic symptoms and/or physical findings including abdominal pain, weight loss, bloody stool, diarrhea, perianal skin tags, and anal fissures or fistulas. Any of these GI findings should prompt an intestinal biopsy to rule out any histologic evidence of CD.

Metastatic CD affecting the vulva often presents with vulvar pain and pruritus and may clinically mimic a more benign disease such as balanitis plasmacellularis, also referred to as Zoon vulvitis.23 Similar to MCD on any given body surface, there is dramatic variation in the macroscopic presentation of vulvar MCD, with physical examination findings ranging from bilateral diffuse, edematous, deeply macerated, red, ulcerated lesions over the vulva with lymphadenopathy to findings of bilateral vulvar pain with yellow drainage from the labia majora.23 There have been cases of vulvar MCD that include exquisite vulvar pain but without structural abnormalities including normal uterus, cervix, adnexa, rectovaginal septum, and rectum. In these more nebulous cases of vulvar MCD, the diagnosis often is discovered incidentally when nonspecific diagnostic imaging suggests underlying CD.23

Beyond the case-by-case variations on physical examination, the great difficulty in diagnosis, particularly in children, occurs in the absence of any GI symptoms and therefore no logical consideration of underlying CD. Consequently, there have been cases of children presenting with irritation of the vulva who were eventually diagnosed with MCD only after erroneous treatment of contact dermatitis, candidiasis, and even consideration of sexual abuse.37 Because it is so rare and obscure among practicing clinicians, the diagnosis of MCD often is considered only after irritation or swelling of the external genitalia has not responded to standard therapies. If and when the diagnosis of MCD is considered in children, it has been suggested to screen patients for anorectal stricture, as case studies have found the condition to be relatively common in this subpopulation.44

In the less common case of adults with genitourinary symptoms that suggest possible MCD, the differential diagnosis for penile or vaginal ulcers should include contact and irritant dermatitis, chronic infectious lesions (eg, hidradenitis suppurativa, actinomycosis, tuberculosis),45 sexually transmitted ulcerative diseases (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes genitalia, granuloma inguinale),46 drug reactions, and even extramammary Paget disease.47

Histologic Findings

Because MCD has so much macroscopic variation and can present anywhere on the surface of the body, formal diagnosis relies on microscopy. As an added measure of difficulty in diagnosis, one random biopsy of a suspicious segment of tissue may not contain the expected histologic findings; therefore, clinical suspicion may warrant a second biopsy.10 There have been reported cases of an adult patient without history of CD presenting with a lesion that resembled a more common pathology, such as a genital wart, and the correct diagnosis of MCD with pseudocondylomatous morphology was made only after intestinal manifestations prompted the clinician to consider such an unusual diagnosis.48

From a histopathologic perspective, MCD is characterized by discrete, noncaseating, sarcoidlike granulomas with abundant multinucleated giant cells (Langhans giant cells) in the superficial dermis (papillary), deep dermis (reticular), and adipose tissue (Figure).8,17 In the presence of concomitant intestinal disease, the granulomas of both the intestinal and dermal tissues should share the same microscopic characteristics.8 In addition, copious neutrophils and granulomas surrounding the microvasculature have been described,34 as well as general lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrate.45 Some histologic samples have included collagen degeneration termed necrobiosis in the middle dermal layer as another variable finding in MCD.14,34

On microscopy, it has been reported that use of Verhoeff-van Gieson staining may be helpful to highlight the presence of neutrophil obstruction within the dermal vasculature, particularly the arterial lumen, as well as to aid in highlighting swelling of the endothelium with fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina.17 Although not part of the routine diagnosis, electron microscopy of MCD tissue samples have confirmed hypertrophy of the endothelial cells composing the capillaries with resulting extravasation of fibrin, red blood cells, lymphocytes, and epithelioid histiocytes.17 Observation of tissue under direct immunofluorescence has been less helpful, as it has shown only nonspecific fibrinogen deposition within the dermis and dermal vessels.17

In an article on treatment of MCD, Escher et al43 reinforced that the macroscopic findings of MCD are diverse, and the microscopic findings characteristic of MCD also can be mimicked by other etiologies such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, fungal infections, lymphogranuloma venereum, leishmaniasis, and connective tissue disorders.43 As such, the workup to rule out infectious, anatomic, and autoimmune etiologies should be diverse. Often, the workup for MCD will include special stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen stain to rule out Mycobacterium tuberculosis and acid-fast bacilli and Fite stain to consider atypical mycobacteria. Other tests such as tissue culture, chest radiograph, tuberculin skin test (Mantoux test), IFN-γ release assay, or polarized light microscopy may rule out infectious etiologies.9,49 Serologic testing might include VDRL test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus.5

Crohn disease is characterized histologically by sarcoidlike noncaseating granulomas, and as such, it is important to differentiate MCD from sarcoidosis prior to histologic analysis. Sarcoidosis also can be considered much less likely with a normal chest radiograph and in the absence of increased serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels.7 The differentiation of sarcoidosis from MCD on the microscopic scale is subtle but is sometimes facilitated in the presence of an ulcerated epidermis or lymphocytic/eosinophilic infiltrate and edema within the dermis, all suggestive of MCD.14

Metastatic CD also should be differentiated from erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, which are among the most common cutaneous findings associated with CD.14 Pyoderma gangrenosum can be distinguished histologically by identifying copious neutrophilic infiltrate with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.50

Treatment

Because MCD is relatively rare, there are no known randomized trials suggesting a particular medical or surgical treatment. In a review of perineal MCD from 2007, the 40-year-old recommendation by Moutain3 opting for surgical debridement versus medical management still resonates, particularly for perineal disease, as an effective measure in all but the mildest of presentations.51 However, recent case reports also suggest that the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors such as infliximab and adalimumab should be considered prior to surgery even with severe perineal MCD.51 Moreover, even if medical management with TNF-α inhibitors or some combination of immunosuppressants and antibiotics does not eradicate the disease, it often helps reduce the size of the ulcers prior to surgery.52 With a limited understanding of MCD, one might think that removal of the affected bowel would eliminate cutaneous disease, but it has been shown that this strategy is not effective.53,54

The composition and location of the particular lesion affects the trajectory of treatment. For example, MCD manifesting as local ulcers and plaques has been described as responding well to topical and intralesional steroids.10,55,56 In the case of penile swelling and/or phimosis, circumcision has been helpful to improve the patient's ability to void as well as to attain and maintain erection.10 In the case of scrotal swelling secondary to MCD, early treatment (ie, within 4 to 6 months) with oral steroids and/or metronidazole is likely beneficial to prevent refractory edematous organization of the tissue.57

As a general rule, an effective treatment will include a combination of an immunosuppressant, antibiotic therapy, and sometimes surgery. The most commonly used immunosuppressant agents include topical or intralesional steroids, infliximab,43,58 cyclosporine A,59,60 dapsone, minocycline, thalidomide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, tacrolimus, and 6-mercaptopurine.4 Steroids have been the conventional treatment of extraintestinal manifestations of CD61; however, perineal CD has been poorly controlled with systemic steroids.62 If steroids are found not to be effective, sometimes agents such as dapsone or thalidomide are considered. One case report noted stabilization of MCD penile ulcers with oral thalidomide 300 mg once daily, oral minocycline 100 mg once daily, and topical tacrolimus 0.3% with benzocaine twice daily with continuation of prednisolone and methotrexate as parts of previously unsuccessful regimen.52

Metronidazole is perhaps the most commonly used antibiotic, having been a component of many successful regimens.4,63 For example, a 27-year-old patient with MCD presenting as a nonhealing ulcerative lesion in the subcoronal area of the penis and scrotum was treated successfully with a 6-month course of mesalamine, prednisone, and metronidazole.45 Another case report of vulvar MCD reported initial success with intravenous methylprednisolone, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole.23 The primary limitation of metronidazole is that subsequent tapering of the dose seems to result in recurrence of disease.64 Consequently, patients must remain on the antibiotic for an indeterminate course, with dosages ranging from 5 mg/kg daily in adolescents65 to 1000 to 1500 mg daily in adults.66

Of the various immunosuppressants available, infliximab has been listed in numerous reports as a successful agent in both the induction and maintenance of extraintestinal manifestations of CD including MCD.67-71 Infliximab has been reported to be effective in the treatment of penile and scrotal edema secondary to MCD that did not respond to other immunosuppressants including oral prednisolone, azathioprine, and cyclosporine.43 Infliximab may be a good option to help heal draining fistulas, particularly in combination with an antibiotic such as metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, which helps to prevent abscess formation during healing.72 The response to infliximab has been dramatic, with resolution of cutaneous lesions after just 6 weeks in some cases.73 The dosing regimen of infliximab has been suggested at 5 mg/kg administered at 0, 2, and 6 weeks, with subsequent maintenance infusions every 10 weeks,70 or at 0, 4, and 12 weeks, with subsequent infusions every 8 weeks.43

Adalimumab may be considered as an alternative to infliximab and is potentially less allergenic as a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, which also has been used successfully to both induce and maintain remission of moderate to severe CD.42,74,75 Proposed dosing of adalimumab includes a loading dose of 160 mg subcutaneously on day 1, followed by an 80-mg dose 2 weeks later and a 40-mg maintenance dose every other week indefinitely.48 Of note, adalimumab has been noted in the literature to have many potential side effects, including one particular case in which severe headaches were attributed to its use.59 As a consequence of the headaches, the patient was switched from adalimumab to cyclosporine and responded well with no subsequent flare-ups on follow-up.

In summary, treatment of MCD depends on cutaneous location, severity, physician experience with certain antibiotics or immunosuppressants, availability of medication, and patient disposition. It seems reasonable to attempt medical management with one or more medical regimens before committing to surgical intervention. Furthermore, even with debridement, curettage, skin graft, or other surgical strategy, the patient is likely to require some period of immunosuppression to provide long-lasting remission.

Conclusion

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease often develop dermatologic sequelae, with MCD being a rare but serious process. Patients may present with a wide array of physical concerns and symptoms, many resembling other disease processes. As such, education and a high index of suspicion are needed for proper diagnosis and treatment.

Almost half of Crohn disease (CD) patients experience a dermatologic manifestation of the disease. A rare entity, metastatic CD (MCD) presents a diagnostic challenge without a high index of suspicion. Its etiology is not well defined; however, it appears to be an autoimmune response to gut antigens. Herein, we review the etiology/epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, and treatment for this uncommon condition.

Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of MCD

Metastatic CD was first described by Parks et al1 in 1965 and refers to a diverse collection of macroscopic dermatologic manifestations in tissue not contiguous with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. To be classified as MCD, the tissue must demonstrate characteristic histopathologic findings, which invariably include noncaseating granulomas.

Crohn disease may affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to anus, with a multitude of associated cutaneous manifestations having been described. The terminal ileum is the most commonly affected portion of the GI tract in CD, but the large intestine also may be involved in 55% to 80% of cases.2 The incidence of non-MCD-associated anal lesions seems to correlate with intestinal involvement in that as few as 25% of patients with ileal-localized CD have anal lesions compared to nearly 80% of patients with large intestinal involvement.3

It has been estimated that 18% to 44% of patients with CD have some form of cutaneous manifestation,4 with MCD being a rare subcategory. As few as 100 cases have been described from 1965 to the present.5 The presence of MCD does not correlate well with severity of intestinal CD, and although a majority of MCD cases present after at least 6 months of GI symptoms,6 there are instances in which MCD presents without prior or existing evidence of intestinal CD.7

With regard to MCD, the term metastatic is sometimes supplanted in the literature by cutaneous to avoid any implication of cancer; however, due to a myriad of dermatologic manifestations, both terms can cause confusion. The categorization of the various types of cutaneous findings in CD is well summarized in a review by Palamaras et al8 with the following classifications: (1) granulomatous by direct extension (oral or perianal), (2) MCD lesions (genital and nongenital), (3) immune-related lesions, and (4) lesions from nutritional deficiencies. Of the cutaneous manifestations relating to CD, MCD is the least common cutaneous categorical manifestation and is further divided into subcategories of genital and nongenital lesions.8

The nongenital distribution of MCD is the more common variety in adults and particularly seems to affect the legs and plantar surfaces (38%), the trunk and abdomen (24%), and the face (15%).5,9 These nongenital MCD manifestations are most commonly described as nodules, ulcerations, or erythematous to purple plaques, and less commonly described as abscesses, pustules, or papules.

The sequence of cutaneous symptoms of MCD relative to intestinal disease depends to some degree on patient age. In adults diagnosed with MCD, it has been noted that a GI flare is expected 2 months to 4 years after diagnosis; however, in children the subsequent GI flare has been noted to vary more widely from 9 months to 14 years following presentation of MCD.8 Furthermore, roughly 50% of children diagnosed with MCD present concomitantly with their first symptoms of a GI flare, whereas 70% of adults with MCD had been previously diagnosed with intestinal CD.8 In one review of 80 reported cases of MCD, 20% (16/80) had no symptoms of intestinal disease at the time of MCD diagnosis, and the majority of the asymptomatic cases were in children; interestingly, the majority of these same children were diagnosed with CD months to years later.9

Both the location and characteristics of cutaneous findings in MCD correlate with age.9 Metastatic CD has been identified in all age groups; however, lymphedema is more common in children/young adults, while nodules, ulceration, and fistulating disease are more often seen in adults.10 Affected children and adolescents with MCD range from 5 to 17 years of age, with a mean age at disease onset of 11.1 years and equal incidence in males and females.8 Adults with MCD range from 18 to 78 years of age, with a mean age at presentation of 38.4 years.8,11

Concerning anatomic location of disease, adults with MCD most commonly have nodules with or without plaques on the arms and legs and less commonly in the genital area.8 In contrast, children with MCD are more prone to genital lesions, with up to 85% of cases including some degree of genital erythematous or nonerythematous swelling with or without induration.8 Genitourinary complications of CD as a broad category, however, are estimated to occur in only 5% to 20% of intestinal CD cases in both children and adults.12

There have been conflicting reports regarding gender predilection in MCD. Based on a review by Samitz et al13 of 200 cases of CD over an 18-year period, 22% of patients with CD were found to have cutaneous manifestations--presumably not MCD but rather perianal, perineal, vulvar fistulae, fissures, or abscesses--with a male to female preponderance of almost 2 to 1. A more recent review of the literature by Palamaras et al8 in 2008 reported that contiguous non-MCD affects adult females and children more often than adult males, with 63% adult cases being female. This review seems to be more congruent with other reports in the literature implicating that females are twice as commonly affected by MCD than males.9,14

Pathophysiology

The etiology of MCD has not been well defined. One proposed mechanism of the distal tissue involvement of MCD is through passage of antigens to the skin with subsequent granulomatous response at the level of the dermis.10 Another proposed mechanism suggests antibody sensitization to gut antigens, possibly bacterial antigens, that then coincidentally cross-react with analogous skin antigens.8,14 Burgdorf11 supported this notion in a 1981 report in which it was suggested that the granulomatous reaction was related to deposition of immune complexes in the skin. Slater et al15 and Tatnall et al16 offered a variation of Burgdorf's notion, suggesting that it was sensitized T cells to circulating antigens that were the initiators of granuloma formation in the periphery.

An examination of MCD tissue in 1990 by Shum and Guenther17 under electron microscopy and immunofluorescence provided evidence against prior studies that purported to have identified immune complexes as the causative agents of MCD. In this study, the authors found no evidence of immune complexes in the dermis of MCD lesions. In addition, an attempt to react serum antibodies of a patient with MCD, which were postulated to have IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies to specific gut antigens, yielded no response when reacted with the tongue, ileum, and colon tissue from a rat. As a culminant finding, the authors also noted MCD dermis tissue with granulomas without vasculitis, suggesting a T-cell mediated type IV hypersensitivity response with a secondary vasculitis from T-cell origin lymphokines and T-cell mediated monocyte activation.17

Research implicating other immunologic entities involved in the pathophysiology of CD such as β-2 integrin,18 CD14+ monocytes,19 and the role of the DNA repair gene MLH1 (mutL homolog 1)20 have been considered but without a clearly definitive role in the manifestations of MCD.

The utility of metronidazole in the treatment of MCD has been suggested as evidence that certain bacteria in the gut may either serve as the causative antigen or may induce its formation21; however, the causative antigen has yet to be identified, and whether it travels distally to the skin or merely resembles a similar antigen normally present in the dermis has not yet been determined. Some research has used in situ polymerase chain reaction techniques to attempt to detect similar microbial pathogens in both the vasculature of active bowel lesions and in the skin, but to date, bacterial RNA noted to be present in the gut vasculature adjacent to CD lesions has not been detected in skin lesions.22

Diagnosis

Physical Findings

Overall, it is estimated that roughly 56% of all MCD cases affect the external genitalia.23 The classic appearance of MCD includes well-demarcated ulcerations in the areas of intertriginous skin folds with or without diffuse edema and tenderness to palpation.23 Although MCD has been historically noted as having a predilection for moist skin folds, there are numerous case reports of MCD all over the body, including the face,7,24-29 retroauricular areas,30 arms and legs,16,17,31-34 lower abdomen,3,5 under the breasts,1 perineum,35 external genitalia,1,9,36-40 and even the lungs41 and bladder.42

As a dermatologic disease, MCD has been referred to as yet another great imitator, both on the macroscopic and microscopic levels.8 As such, more common causes of genital edema should be considered first and investigated based on the patient's history, physical examination, skin biopsy, lymphangiogram, ultrasound, and cystogram.43 Ultrasonography and color Doppler sonography have been shown to be helpful in patients with genital involvement. This modality can evaluate not only the presence of normal testes but also intratesticular and scrotal wall fluid, especially when the physical examination reveals swelling that makes testicle palpation more difficult.6 Clinically, the correct diagnosis of MCD often is made through suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease based on classic symptoms and/or physical findings including abdominal pain, weight loss, bloody stool, diarrhea, perianal skin tags, and anal fissures or fistulas. Any of these GI findings should prompt an intestinal biopsy to rule out any histologic evidence of CD.

Metastatic CD affecting the vulva often presents with vulvar pain and pruritus and may clinically mimic a more benign disease such as balanitis plasmacellularis, also referred to as Zoon vulvitis.23 Similar to MCD on any given body surface, there is dramatic variation in the macroscopic presentation of vulvar MCD, with physical examination findings ranging from bilateral diffuse, edematous, deeply macerated, red, ulcerated lesions over the vulva with lymphadenopathy to findings of bilateral vulvar pain with yellow drainage from the labia majora.23 There have been cases of vulvar MCD that include exquisite vulvar pain but without structural abnormalities including normal uterus, cervix, adnexa, rectovaginal septum, and rectum. In these more nebulous cases of vulvar MCD, the diagnosis often is discovered incidentally when nonspecific diagnostic imaging suggests underlying CD.23

Beyond the case-by-case variations on physical examination, the great difficulty in diagnosis, particularly in children, occurs in the absence of any GI symptoms and therefore no logical consideration of underlying CD. Consequently, there have been cases of children presenting with irritation of the vulva who were eventually diagnosed with MCD only after erroneous treatment of contact dermatitis, candidiasis, and even consideration of sexual abuse.37 Because it is so rare and obscure among practicing clinicians, the diagnosis of MCD often is considered only after irritation or swelling of the external genitalia has not responded to standard therapies. If and when the diagnosis of MCD is considered in children, it has been suggested to screen patients for anorectal stricture, as case studies have found the condition to be relatively common in this subpopulation.44

In the less common case of adults with genitourinary symptoms that suggest possible MCD, the differential diagnosis for penile or vaginal ulcers should include contact and irritant dermatitis, chronic infectious lesions (eg, hidradenitis suppurativa, actinomycosis, tuberculosis),45 sexually transmitted ulcerative diseases (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes genitalia, granuloma inguinale),46 drug reactions, and even extramammary Paget disease.47

Histologic Findings

Because MCD has so much macroscopic variation and can present anywhere on the surface of the body, formal diagnosis relies on microscopy. As an added measure of difficulty in diagnosis, one random biopsy of a suspicious segment of tissue may not contain the expected histologic findings; therefore, clinical suspicion may warrant a second biopsy.10 There have been reported cases of an adult patient without history of CD presenting with a lesion that resembled a more common pathology, such as a genital wart, and the correct diagnosis of MCD with pseudocondylomatous morphology was made only after intestinal manifestations prompted the clinician to consider such an unusual diagnosis.48

From a histopathologic perspective, MCD is characterized by discrete, noncaseating, sarcoidlike granulomas with abundant multinucleated giant cells (Langhans giant cells) in the superficial dermis (papillary), deep dermis (reticular), and adipose tissue (Figure).8,17 In the presence of concomitant intestinal disease, the granulomas of both the intestinal and dermal tissues should share the same microscopic characteristics.8 In addition, copious neutrophils and granulomas surrounding the microvasculature have been described,34 as well as general lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrate.45 Some histologic samples have included collagen degeneration termed necrobiosis in the middle dermal layer as another variable finding in MCD.14,34

On microscopy, it has been reported that use of Verhoeff-van Gieson staining may be helpful to highlight the presence of neutrophil obstruction within the dermal vasculature, particularly the arterial lumen, as well as to aid in highlighting swelling of the endothelium with fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina.17 Although not part of the routine diagnosis, electron microscopy of MCD tissue samples have confirmed hypertrophy of the endothelial cells composing the capillaries with resulting extravasation of fibrin, red blood cells, lymphocytes, and epithelioid histiocytes.17 Observation of tissue under direct immunofluorescence has been less helpful, as it has shown only nonspecific fibrinogen deposition within the dermis and dermal vessels.17

In an article on treatment of MCD, Escher et al43 reinforced that the macroscopic findings of MCD are diverse, and the microscopic findings characteristic of MCD also can be mimicked by other etiologies such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, fungal infections, lymphogranuloma venereum, leishmaniasis, and connective tissue disorders.43 As such, the workup to rule out infectious, anatomic, and autoimmune etiologies should be diverse. Often, the workup for MCD will include special stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen stain to rule out Mycobacterium tuberculosis and acid-fast bacilli and Fite stain to consider atypical mycobacteria. Other tests such as tissue culture, chest radiograph, tuberculin skin test (Mantoux test), IFN-γ release assay, or polarized light microscopy may rule out infectious etiologies.9,49 Serologic testing might include VDRL test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus.5

Crohn disease is characterized histologically by sarcoidlike noncaseating granulomas, and as such, it is important to differentiate MCD from sarcoidosis prior to histologic analysis. Sarcoidosis also can be considered much less likely with a normal chest radiograph and in the absence of increased serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels.7 The differentiation of sarcoidosis from MCD on the microscopic scale is subtle but is sometimes facilitated in the presence of an ulcerated epidermis or lymphocytic/eosinophilic infiltrate and edema within the dermis, all suggestive of MCD.14

Metastatic CD also should be differentiated from erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, which are among the most common cutaneous findings associated with CD.14 Pyoderma gangrenosum can be distinguished histologically by identifying copious neutrophilic infiltrate with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.50

Treatment

Because MCD is relatively rare, there are no known randomized trials suggesting a particular medical or surgical treatment. In a review of perineal MCD from 2007, the 40-year-old recommendation by Moutain3 opting for surgical debridement versus medical management still resonates, particularly for perineal disease, as an effective measure in all but the mildest of presentations.51 However, recent case reports also suggest that the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors such as infliximab and adalimumab should be considered prior to surgery even with severe perineal MCD.51 Moreover, even if medical management with TNF-α inhibitors or some combination of immunosuppressants and antibiotics does not eradicate the disease, it often helps reduce the size of the ulcers prior to surgery.52 With a limited understanding of MCD, one might think that removal of the affected bowel would eliminate cutaneous disease, but it has been shown that this strategy is not effective.53,54

The composition and location of the particular lesion affects the trajectory of treatment. For example, MCD manifesting as local ulcers and plaques has been described as responding well to topical and intralesional steroids.10,55,56 In the case of penile swelling and/or phimosis, circumcision has been helpful to improve the patient's ability to void as well as to attain and maintain erection.10 In the case of scrotal swelling secondary to MCD, early treatment (ie, within 4 to 6 months) with oral steroids and/or metronidazole is likely beneficial to prevent refractory edematous organization of the tissue.57

As a general rule, an effective treatment will include a combination of an immunosuppressant, antibiotic therapy, and sometimes surgery. The most commonly used immunosuppressant agents include topical or intralesional steroids, infliximab,43,58 cyclosporine A,59,60 dapsone, minocycline, thalidomide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, tacrolimus, and 6-mercaptopurine.4 Steroids have been the conventional treatment of extraintestinal manifestations of CD61; however, perineal CD has been poorly controlled with systemic steroids.62 If steroids are found not to be effective, sometimes agents such as dapsone or thalidomide are considered. One case report noted stabilization of MCD penile ulcers with oral thalidomide 300 mg once daily, oral minocycline 100 mg once daily, and topical tacrolimus 0.3% with benzocaine twice daily with continuation of prednisolone and methotrexate as parts of previously unsuccessful regimen.52

Metronidazole is perhaps the most commonly used antibiotic, having been a component of many successful regimens.4,63 For example, a 27-year-old patient with MCD presenting as a nonhealing ulcerative lesion in the subcoronal area of the penis and scrotum was treated successfully with a 6-month course of mesalamine, prednisone, and metronidazole.45 Another case report of vulvar MCD reported initial success with intravenous methylprednisolone, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole.23 The primary limitation of metronidazole is that subsequent tapering of the dose seems to result in recurrence of disease.64 Consequently, patients must remain on the antibiotic for an indeterminate course, with dosages ranging from 5 mg/kg daily in adolescents65 to 1000 to 1500 mg daily in adults.66

Of the various immunosuppressants available, infliximab has been listed in numerous reports as a successful agent in both the induction and maintenance of extraintestinal manifestations of CD including MCD.67-71 Infliximab has been reported to be effective in the treatment of penile and scrotal edema secondary to MCD that did not respond to other immunosuppressants including oral prednisolone, azathioprine, and cyclosporine.43 Infliximab may be a good option to help heal draining fistulas, particularly in combination with an antibiotic such as metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, which helps to prevent abscess formation during healing.72 The response to infliximab has been dramatic, with resolution of cutaneous lesions after just 6 weeks in some cases.73 The dosing regimen of infliximab has been suggested at 5 mg/kg administered at 0, 2, and 6 weeks, with subsequent maintenance infusions every 10 weeks,70 or at 0, 4, and 12 weeks, with subsequent infusions every 8 weeks.43

Adalimumab may be considered as an alternative to infliximab and is potentially less allergenic as a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, which also has been used successfully to both induce and maintain remission of moderate to severe CD.42,74,75 Proposed dosing of adalimumab includes a loading dose of 160 mg subcutaneously on day 1, followed by an 80-mg dose 2 weeks later and a 40-mg maintenance dose every other week indefinitely.48 Of note, adalimumab has been noted in the literature to have many potential side effects, including one particular case in which severe headaches were attributed to its use.59 As a consequence of the headaches, the patient was switched from adalimumab to cyclosporine and responded well with no subsequent flare-ups on follow-up.