User login

Pruritic Eruption on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

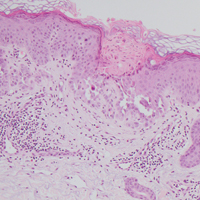

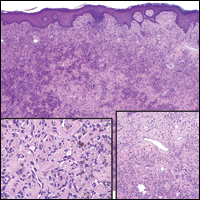

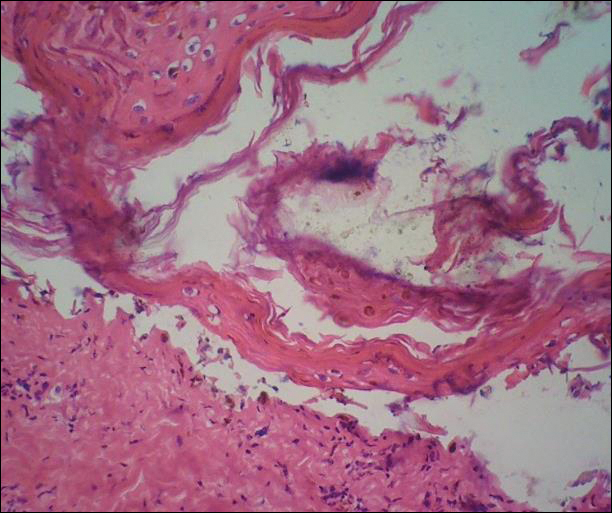

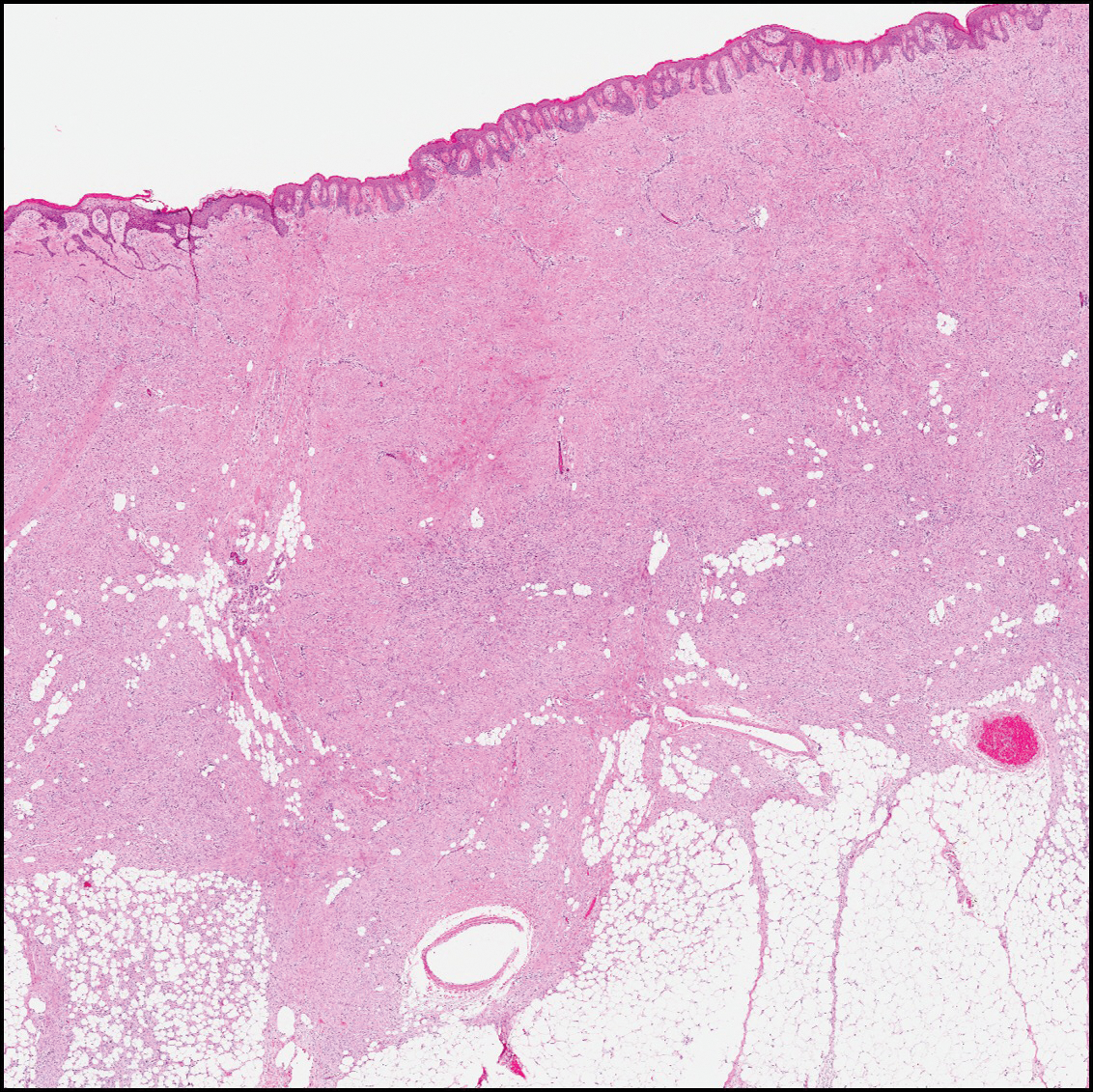

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

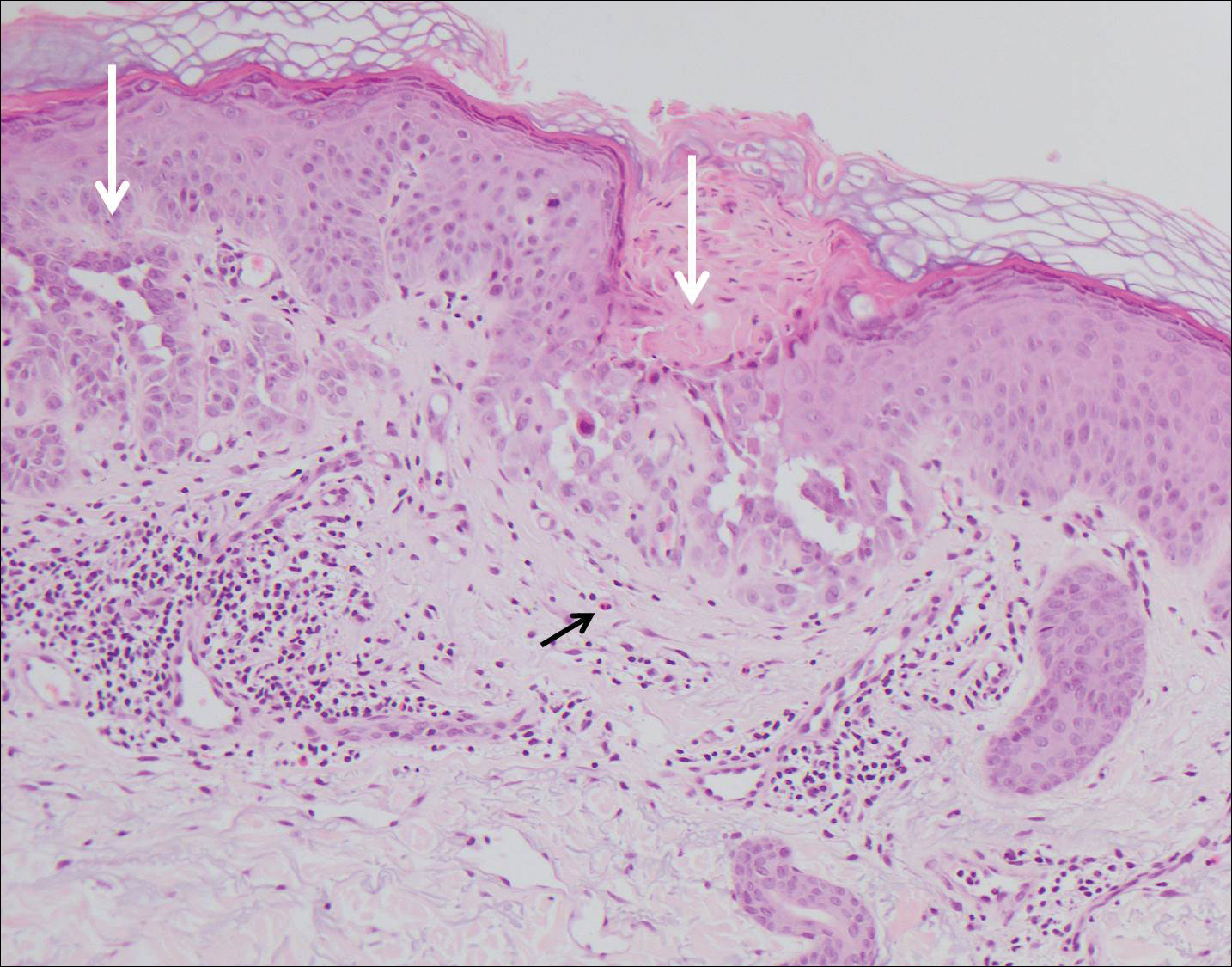

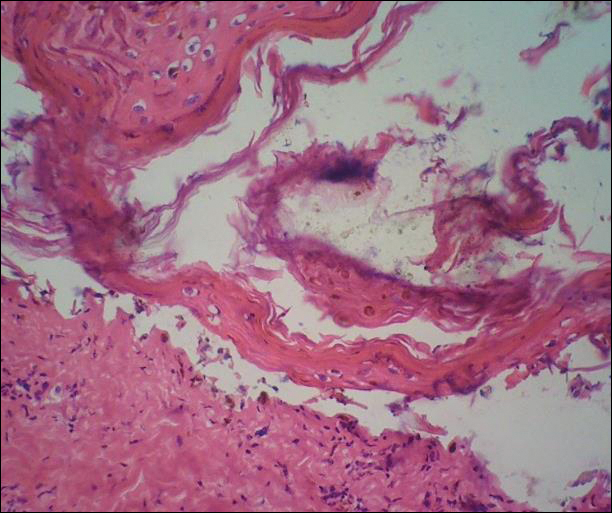

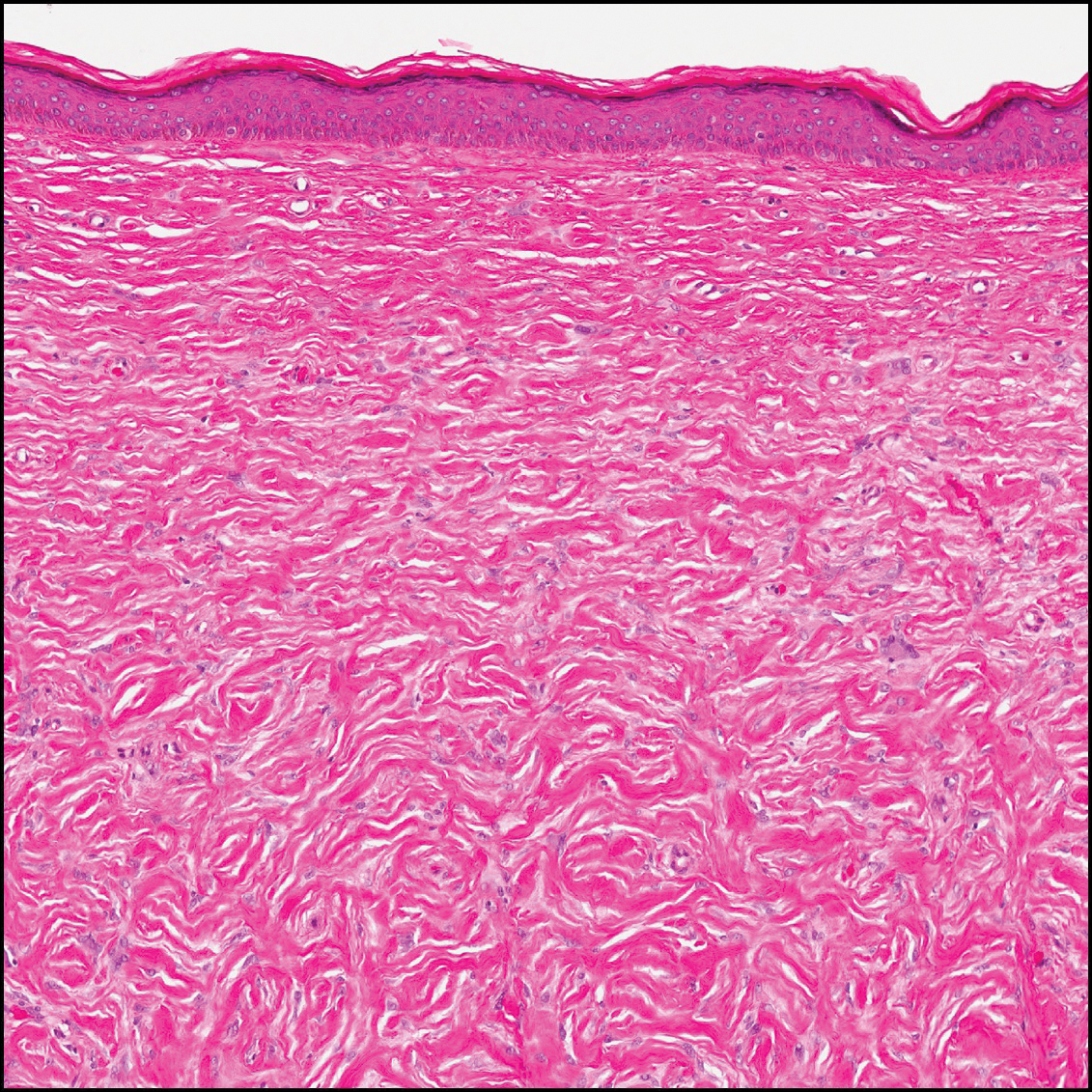

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

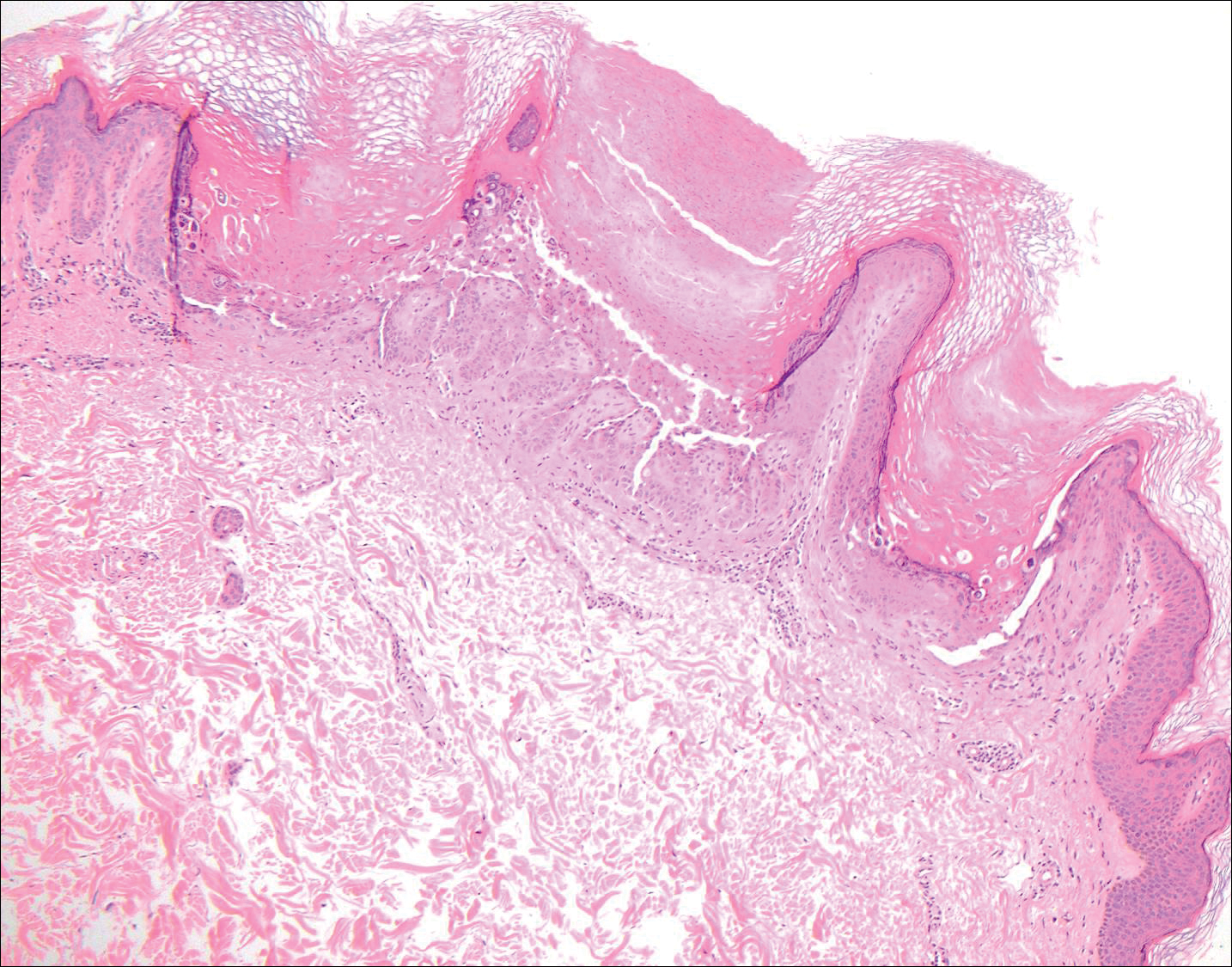

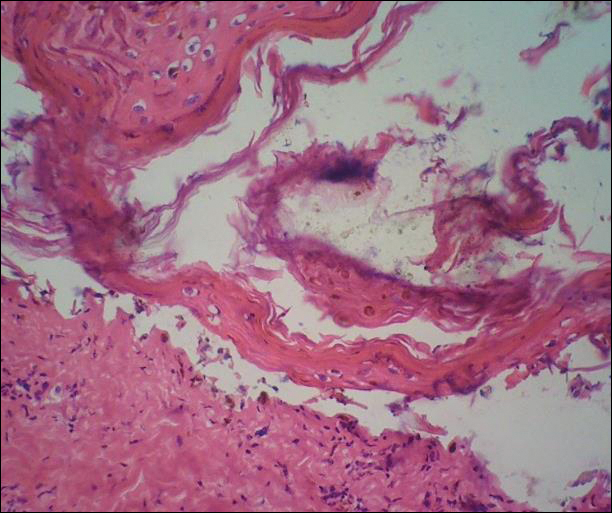

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

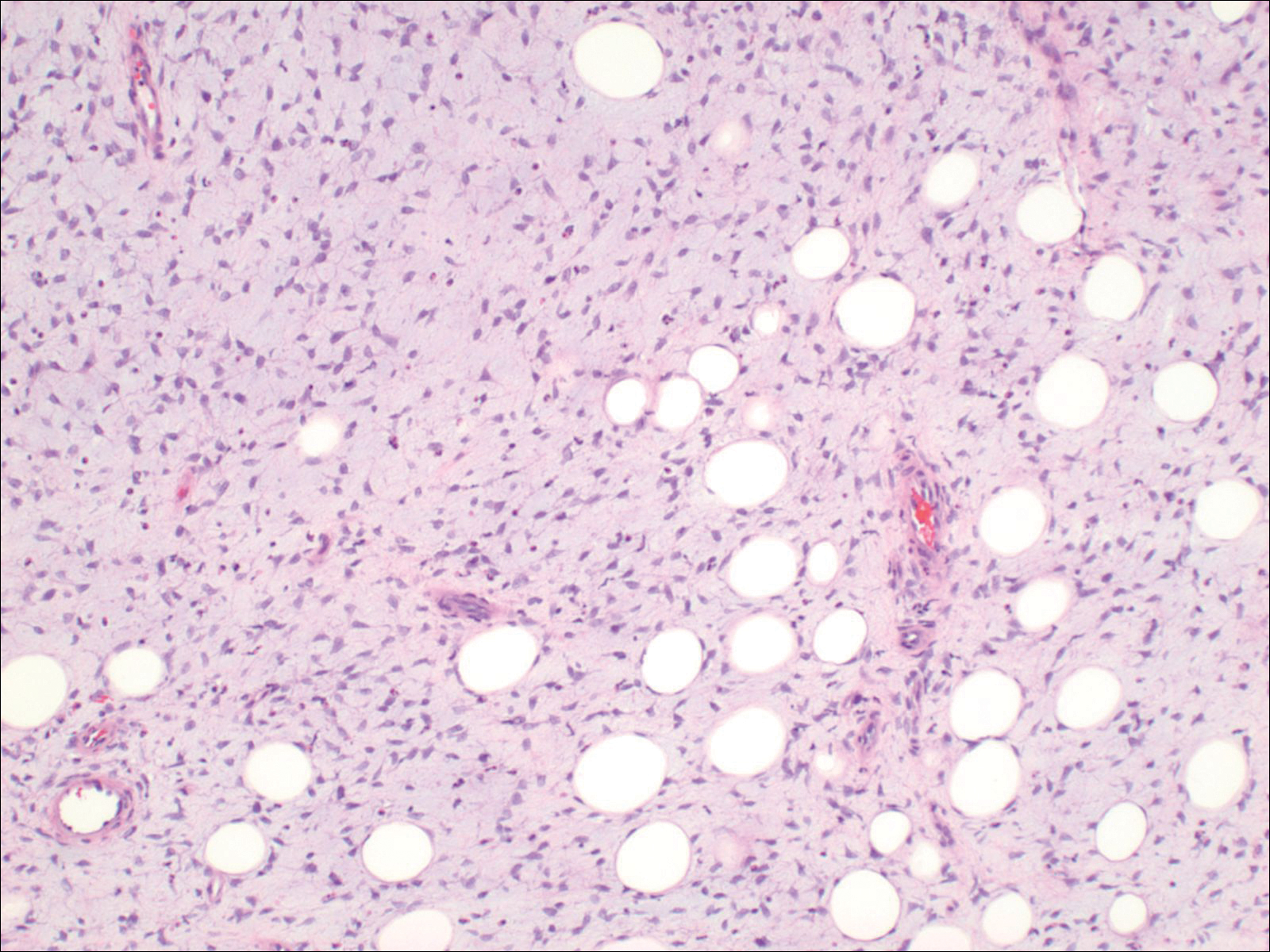

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

A 55-year-old man presented with small, erythematous, nonfollicular, pruritic papules on the mid chest.

Asymptomatic Cutaneous Polyarteritis Nodosa: Treatment Options and Therapeutic Guidelines

In 1931, Lindberg1 described a cutaneous variant of polyarteritis nodosa, which lacked visceral involvement and possessed a more favorable prognosis.2 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN) is a localized small- to medium-vessel vasculitis restricted to the skin. Both benign and chronic courses have been described, and systemic involvement does not occur.3 Diagnostic criteria proposed by Nakamura et al3 in 2009 included cutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, purpura, or ulcers; histopathologic fibrinoid necrotizing vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels; and exclusion of systemic symptoms (eg, fever, hypertension, weight loss, renal failure, cerebral hemorrhage, neuropathy, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, pericarditis, pleuritis, arthralgia/myalgia). Nodules occur in 30% to 50% of cases and can remain for years if left untreated. Ulcerations occur in up to 30% of patients. Myositis, arthritis, and weakness also have been reported with this condition.4 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa has been associated with abnormal antibody testing with elevations of antiphospholipid cofactor antibody, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2-glycoprotein I–dependent cardiolipin antibody, as well as elevated anti–phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibody.5 These antibodies suggest increased risk for thrombosis and systemic diseases such as lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue disease. The distinction of this entity from systemic polyartertitis nodosa is key when determining treatment options and monitoring parameters.

Case Report

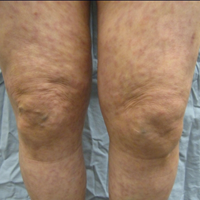

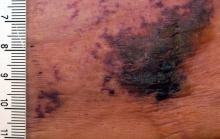

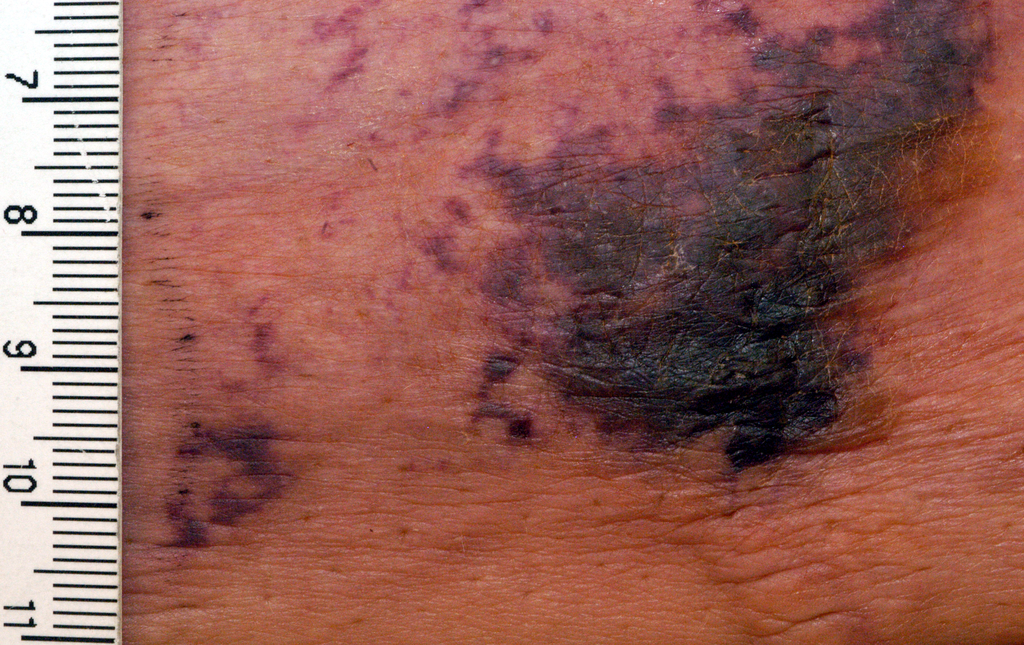

A 66-year-old woman was referred to our facility by an outside dermatologist with a mildly pruritic, blanchable, reticulated erythema on the chest and bilateral arms and legs of 3 months’ duration consistent with livedo reticularis (Figure 1). Prior systemic therapy included prednisone 10 mg 3 times daily, fexofenadine, loratadine, and hydroxyzine. When the systemic steroid was tapered, the patient developed an asymptomatic flare of her eruption. On presentation, the lesions had waxed and waned, and the patient was taking only vitamin B12 and vitamin C. Her medical history was notable for an unknown-type lymphoma of the chest wall diagnosed at 46 years of age that was treated with an unknown chemotherapeutic agent, chronic pancreatitis that resulted in a duodenectomy at 61 years of age, chronic cholecystitis, and 1 first-trimester miscarriage. Outside laboratory tests, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, urinalysis, renal function, and liver function tests were within reference range, except for the finding of mild leukocytosis (11,000/µL)(reference range, 3800–10,800/µL), which resolved after steroids were discontinued, with otherwise normal results. Punch biopsy of a specimen from the right thigh revealed medium-vessel vasculitis consistent with polyarteritis nodosa (Figure 2). Laboratory workup by our facility including hepatitis panel, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, factor V Leiden, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, anticardiolipin antibody, and proteins C and S were all within reference range. Abnormal values included a low positive but nondiagnostic antinuclear antibody screen with negative titers, and the lupus anticoagulant titer was mildly elevated at 44 IgG binding units (reference range, <40 IgG binding units). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and urine protein electrophoresis also were performed, and SPEP was low positive for elevated κ and γ light chains. The patient was referred to oncology, and further testing revealed no underlying malignancy. The patient was monitored and no treatment was initiated; her rash completely resolved within 3 months. Laboratory monitoring at 6 months including SPEP, urine protein electrophoresis, lupus anticoagulant, and clotting studies all were within reference range.

Comment

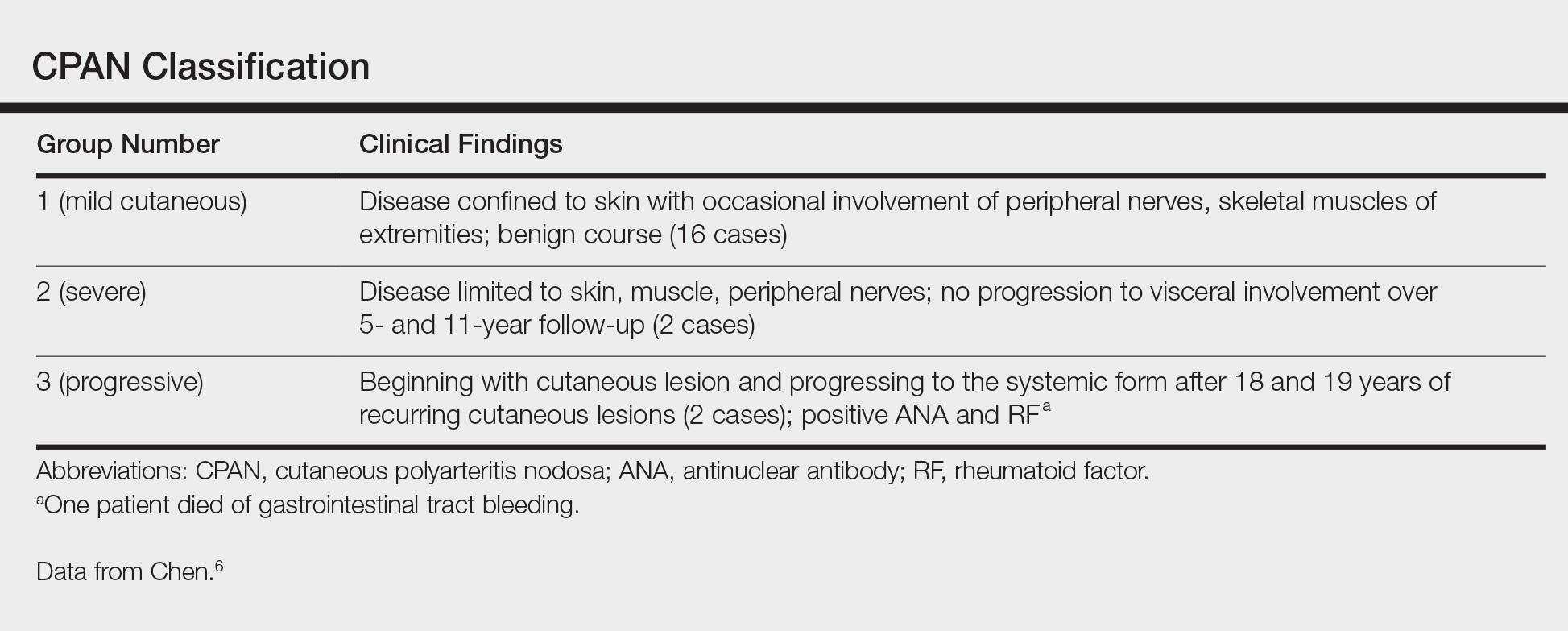

Although the treatment of systemic polyarteritis nodosa often is necessary and typically involves high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, the treatment of CPAN initially is less aggressive. Of the options available for treatment of CPAN, each has associated risks and side effects. Chen6 classified CPAN into 3 groups: 1 (mild), 2 (severe with no systemic involvement), and 3 (severe with progression to systemic disease)(Table). The authors performed a review of all the published treatments and their respective side effects to evaluate if treatment should be instituted for asymptomatic (group 1) disease presenting with abnormal antibody findings as demonstrated in our case.

First-line treatment of CPAN includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and colchicine.7 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are preferred; however, they also have been associated with gastrointestinal tract upset and increased risk for peptic ulcer disease with long-term use. Although colchicine often is used in conjunction with NSAIDS8 for its anti-inflammatory activity, no studies have been performed on this drug as monotherapy, and the side effect of diarrhea often limits its use.

Other therapies include dapsone, which should be monitored carefully due to the risk for dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome.8,9 Topical corticosteroids have been proven effective for mild cases of confluent erythema with remission occurring as early as 4 weeks.4 Some reports emphasize the role of streptococcal infections in CPAN, especially in children.8,10-12 Consequently it is recommended that anti–streptolysin O titers should be included in the workup for CPAN. Long-term penicillin prophylaxis and tonsillectomy have been used to prevent disease flares with limited success.8,10-12

For more severe disease, especially with neuromuscular involvement, oral methylprednisolone up to 1 mg/kg daily has been used and has proven effective in the control of acute exacerbations.7,13 However, the many adverse effects of systemic steroids limit their use long-term, and taper will often result in flare of disease.4,7 Medications used in conjunction with steroids include hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, sulfapyridine, pentoxifylline, infliximab, etanercept, and intravenous immunoglobulin.4,9,12-17

Low-dose methotrexate has shown some improvement in skin disease with CPAN, but other case reports suggest that complete remission is not achieved with this drug.15,18 More studies are needed to assess the use of methotrexate for CPAN.

Immunomodulators have been used in multiple case reports with varying levels of success. Rogalski and Sticherling4 reported 3 cases that cleared with methylprednisolone plus azathioprine ranging from 4 weeks to 6 months; nausea limited tolerance of azathioprine in 1 case. Mycophenolate mofetil also was successfully used in 2 cases with clearance at 17 weeks and 6 months. In this series of cases, cyclosporine was ineffective for CPAN.4 Two case reports documented cutaneous clearance with cyclophosphamide in conjunction with prednisolone.9,10 No prospective trials have been performed on these medications, and immunosuppressants should only be considered in steroid-resistant cases.

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin has been reported effective in prior cases that showed resistance to more conventional trials of steroids, azathioprine, and/or cyclophosphamide.12,14 Intravenous immunoglobulin may be regarded as a treatment option for severe resistant disease. Several case reports also have documented success using tumor necrosis factor α blockers, particularly infliximab, as an adjunct to steroids and etanercept as both a steroid adjunct and monotherapy.16,17,19 More studies are necessary to evaluate these treatments.

Additionally, single case reports have outlined the use of other therapeutic agents, including tamoxifen (10 mg twice daily increased to 20 mg twice daily during episodes of breakthrough lesions),20 hyperbaric oxygen therapy (100% oxygen for 90 minutes 5 times weekly at 1.5 atm absolute followed by 2 weeks of 2 atm absolute),21 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (300 µg injection in small portion to ulcer edges twice monthly for 2 months).22 All of these treatments show promise, but data are limited.

Because thrombosis is postulated to be a potential mechanism leading to CPAN, agents such as pentoxifylline, clopidogrel, and warfarin have been examined as treatment options. Pentoxifylline in combination with mycophenolate mofetil has been successful in treating a case that was resistant to other immunosuppressants.23 Clopidogrel blocks the adenosine diphosphate pathway and impairs clot retraction. Clopidogrel was reported effective in an acute flare of CPAN for clearance of skin lesions and normalization of lupus anticoagulant.24 It also was used successfully in recurrent CPAN after steroid treatments in a patient with neuromuscular symptoms. There was no recurrence in either of the patients in this case report series. Warfarin therapy at an international normalized ratio of 3.0 also has demonstrated success in halting disease progression and in facilitating the resolution of skin changes and normalization of anti–phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibodies.24 Our review of the literature did not reveal evidence of a standardized length of treatment following symptom resolution or if treatment is indicated in asymptomatic disease, or as in our case, with only mild elevations of antiphospholipid antibodies.

Conclusion

Multiple treatment options exist for CPAN, but the data on their efficacies is limited and based only on anecdotal evidence, not prospective analysis. We believe that it seems reasonable to initiate treatment only for symptomatic disease or cases in which the antibody titers suggest that the patient may be at high risk for thrombosis. Mild symptoms and mild cutaneous changes would suggest the likely choice of NSAIDs, colchicine, or dapsone as treatment options versus no treatment. In patients with antibody titers, pentoxifylline, clopidogrel, or warfarin may be considered first-line therapies. With severe ulcerative lesions and neuromuscular involvement, steroids, immunosuppressants, and other investigative agents should be contemplated. In our patient, the laboratory studies were repeated and normalized on complete resolution of her livedo eruption. She remained asymptomatic and clear for 8 months without any treatment. The incidence of this presentation of CPAN is unknown and is likely underreported, as we would not expect most patients to present to their physicians for the evaluation of otherwise asymptomatic livedo reticularis. In essence, our case report suggests that it may be prudent to simply monitor patients with asymptomatic CPAN.

- Lindberg K. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Periarteritis nodosa. Acta Med Scand. 1931;76:183-225.

- Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa [published online August 26, 2005]. J Neurol. 2005;252:1155-1166.

- Nakamura T, Kanazawa N, Ikeda T, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: revisiting its definition and diagnostic criteria. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:117-121.

- Rogalski C, Sticherling M. Panateritis cutanea benigna—an entity limited to the skin or cutaneous presentation of a systemic necrotizing vasculitis? report of seven cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:817-821.

- Kawakami T, Yamazaki M, Mizoguchi M, et al. High titer of anti-phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibodies in patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1507-1513.

- Chen KR. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a clinical and histopathological study of 20 cases. J Dermatol. 1989;6:429-442.

- Morgan AJ, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a comprehensive review. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:750-756.

- Ishiguro N, Kawashima M. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a report of 16 cases with clinical and histopathologic analysis and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2010;37:85-93.

- Flanagan N, Casey EB, Watson R, et al. Cutaneous polyartertitis nodosa with seronegative arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:1161-1162.

- Fathalla B, Miller L, Brady S, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:724-728.

- Misago N, Mochizuki Y, Sekiyama-Kodera H, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: therapy and clinical course in four cases. J Dermatol. 2001;28:719-727.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins for cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa resistant to conventional treatment. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45:169-170.

- Maillard H, Szczesniak S, Martin L. Cutaneous periarteritis nodosa: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of 9 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;26:125-129.

- Lobo I, Ferreira M, Silva E. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;22:880-882.

- Boehm I, Bauer R. Low-dose methotrexate controls a severe form of polyarteritis nodosa. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:167-169.

- Campanilho-Marques R, Ramos F, Canhão H, et al. Remission induced by infliximab in a childhood polyarteritis nodosa refractory to conventional immunosuppression and rituximab. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:277-278.

- Inoue N, Shimizu M, Mizuta M, et al. Refractory cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: successful treatment with etanercept. Pediatr Int. 2017;59:751-752.

- Schartz NE. Successful treatment in two cases of steroid dependent cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa with low-dose methotrexate. Dermatology. 2001;203:336-338.

- Valor L, Monteagudo I, de la Torre I, et al. Young male patient diagnosed with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa successfully treated with etanercept. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:688-689.

- Cvancara JL, Meffert JJ, Elston DM. Estrogen sensitive cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: response to tamoxifen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:643-646.

- Mazokopakis E, Milkas A, Tsartsalis A, et al. Improvement of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa with hyperbaric oxygen. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1017-1029.

- Tursen U, Api H, Kaya TI, et al. Rapid healing of chronic leg ulcers during perilesional injections of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor in a patient with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1341-1343.

- Kluger N, Guillot B, Bessis D. Ulcerative cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with mycophenolate mofetil and pentoxifylline. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:175-177.

- Kawakami T, Soma Y. Use of warfarin therapy at a target international normalized ratio of 3.0 for cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:602-606.

In 1931, Lindberg1 described a cutaneous variant of polyarteritis nodosa, which lacked visceral involvement and possessed a more favorable prognosis.2 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN) is a localized small- to medium-vessel vasculitis restricted to the skin. Both benign and chronic courses have been described, and systemic involvement does not occur.3 Diagnostic criteria proposed by Nakamura et al3 in 2009 included cutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, purpura, or ulcers; histopathologic fibrinoid necrotizing vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels; and exclusion of systemic symptoms (eg, fever, hypertension, weight loss, renal failure, cerebral hemorrhage, neuropathy, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, pericarditis, pleuritis, arthralgia/myalgia). Nodules occur in 30% to 50% of cases and can remain for years if left untreated. Ulcerations occur in up to 30% of patients. Myositis, arthritis, and weakness also have been reported with this condition.4 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa has been associated with abnormal antibody testing with elevations of antiphospholipid cofactor antibody, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2-glycoprotein I–dependent cardiolipin antibody, as well as elevated anti–phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibody.5 These antibodies suggest increased risk for thrombosis and systemic diseases such as lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue disease. The distinction of this entity from systemic polyartertitis nodosa is key when determining treatment options and monitoring parameters.

Case Report

A 66-year-old woman was referred to our facility by an outside dermatologist with a mildly pruritic, blanchable, reticulated erythema on the chest and bilateral arms and legs of 3 months’ duration consistent with livedo reticularis (Figure 1). Prior systemic therapy included prednisone 10 mg 3 times daily, fexofenadine, loratadine, and hydroxyzine. When the systemic steroid was tapered, the patient developed an asymptomatic flare of her eruption. On presentation, the lesions had waxed and waned, and the patient was taking only vitamin B12 and vitamin C. Her medical history was notable for an unknown-type lymphoma of the chest wall diagnosed at 46 years of age that was treated with an unknown chemotherapeutic agent, chronic pancreatitis that resulted in a duodenectomy at 61 years of age, chronic cholecystitis, and 1 first-trimester miscarriage. Outside laboratory tests, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, urinalysis, renal function, and liver function tests were within reference range, except for the finding of mild leukocytosis (11,000/µL)(reference range, 3800–10,800/µL), which resolved after steroids were discontinued, with otherwise normal results. Punch biopsy of a specimen from the right thigh revealed medium-vessel vasculitis consistent with polyarteritis nodosa (Figure 2). Laboratory workup by our facility including hepatitis panel, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, factor V Leiden, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, anticardiolipin antibody, and proteins C and S were all within reference range. Abnormal values included a low positive but nondiagnostic antinuclear antibody screen with negative titers, and the lupus anticoagulant titer was mildly elevated at 44 IgG binding units (reference range, <40 IgG binding units). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and urine protein electrophoresis also were performed, and SPEP was low positive for elevated κ and γ light chains. The patient was referred to oncology, and further testing revealed no underlying malignancy. The patient was monitored and no treatment was initiated; her rash completely resolved within 3 months. Laboratory monitoring at 6 months including SPEP, urine protein electrophoresis, lupus anticoagulant, and clotting studies all were within reference range.

Comment

Although the treatment of systemic polyarteritis nodosa often is necessary and typically involves high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, the treatment of CPAN initially is less aggressive. Of the options available for treatment of CPAN, each has associated risks and side effects. Chen6 classified CPAN into 3 groups: 1 (mild), 2 (severe with no systemic involvement), and 3 (severe with progression to systemic disease)(Table). The authors performed a review of all the published treatments and their respective side effects to evaluate if treatment should be instituted for asymptomatic (group 1) disease presenting with abnormal antibody findings as demonstrated in our case.

First-line treatment of CPAN includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and colchicine.7 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are preferred; however, they also have been associated with gastrointestinal tract upset and increased risk for peptic ulcer disease with long-term use. Although colchicine often is used in conjunction with NSAIDS8 for its anti-inflammatory activity, no studies have been performed on this drug as monotherapy, and the side effect of diarrhea often limits its use.

Other therapies include dapsone, which should be monitored carefully due to the risk for dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome.8,9 Topical corticosteroids have been proven effective for mild cases of confluent erythema with remission occurring as early as 4 weeks.4 Some reports emphasize the role of streptococcal infections in CPAN, especially in children.8,10-12 Consequently it is recommended that anti–streptolysin O titers should be included in the workup for CPAN. Long-term penicillin prophylaxis and tonsillectomy have been used to prevent disease flares with limited success.8,10-12

For more severe disease, especially with neuromuscular involvement, oral methylprednisolone up to 1 mg/kg daily has been used and has proven effective in the control of acute exacerbations.7,13 However, the many adverse effects of systemic steroids limit their use long-term, and taper will often result in flare of disease.4,7 Medications used in conjunction with steroids include hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, sulfapyridine, pentoxifylline, infliximab, etanercept, and intravenous immunoglobulin.4,9,12-17

Low-dose methotrexate has shown some improvement in skin disease with CPAN, but other case reports suggest that complete remission is not achieved with this drug.15,18 More studies are needed to assess the use of methotrexate for CPAN.

Immunomodulators have been used in multiple case reports with varying levels of success. Rogalski and Sticherling4 reported 3 cases that cleared with methylprednisolone plus azathioprine ranging from 4 weeks to 6 months; nausea limited tolerance of azathioprine in 1 case. Mycophenolate mofetil also was successfully used in 2 cases with clearance at 17 weeks and 6 months. In this series of cases, cyclosporine was ineffective for CPAN.4 Two case reports documented cutaneous clearance with cyclophosphamide in conjunction with prednisolone.9,10 No prospective trials have been performed on these medications, and immunosuppressants should only be considered in steroid-resistant cases.

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin has been reported effective in prior cases that showed resistance to more conventional trials of steroids, azathioprine, and/or cyclophosphamide.12,14 Intravenous immunoglobulin may be regarded as a treatment option for severe resistant disease. Several case reports also have documented success using tumor necrosis factor α blockers, particularly infliximab, as an adjunct to steroids and etanercept as both a steroid adjunct and monotherapy.16,17,19 More studies are necessary to evaluate these treatments.

Additionally, single case reports have outlined the use of other therapeutic agents, including tamoxifen (10 mg twice daily increased to 20 mg twice daily during episodes of breakthrough lesions),20 hyperbaric oxygen therapy (100% oxygen for 90 minutes 5 times weekly at 1.5 atm absolute followed by 2 weeks of 2 atm absolute),21 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (300 µg injection in small portion to ulcer edges twice monthly for 2 months).22 All of these treatments show promise, but data are limited.

Because thrombosis is postulated to be a potential mechanism leading to CPAN, agents such as pentoxifylline, clopidogrel, and warfarin have been examined as treatment options. Pentoxifylline in combination with mycophenolate mofetil has been successful in treating a case that was resistant to other immunosuppressants.23 Clopidogrel blocks the adenosine diphosphate pathway and impairs clot retraction. Clopidogrel was reported effective in an acute flare of CPAN for clearance of skin lesions and normalization of lupus anticoagulant.24 It also was used successfully in recurrent CPAN after steroid treatments in a patient with neuromuscular symptoms. There was no recurrence in either of the patients in this case report series. Warfarin therapy at an international normalized ratio of 3.0 also has demonstrated success in halting disease progression and in facilitating the resolution of skin changes and normalization of anti–phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibodies.24 Our review of the literature did not reveal evidence of a standardized length of treatment following symptom resolution or if treatment is indicated in asymptomatic disease, or as in our case, with only mild elevations of antiphospholipid antibodies.

Conclusion

Multiple treatment options exist for CPAN, but the data on their efficacies is limited and based only on anecdotal evidence, not prospective analysis. We believe that it seems reasonable to initiate treatment only for symptomatic disease or cases in which the antibody titers suggest that the patient may be at high risk for thrombosis. Mild symptoms and mild cutaneous changes would suggest the likely choice of NSAIDs, colchicine, or dapsone as treatment options versus no treatment. In patients with antibody titers, pentoxifylline, clopidogrel, or warfarin may be considered first-line therapies. With severe ulcerative lesions and neuromuscular involvement, steroids, immunosuppressants, and other investigative agents should be contemplated. In our patient, the laboratory studies were repeated and normalized on complete resolution of her livedo eruption. She remained asymptomatic and clear for 8 months without any treatment. The incidence of this presentation of CPAN is unknown and is likely underreported, as we would not expect most patients to present to their physicians for the evaluation of otherwise asymptomatic livedo reticularis. In essence, our case report suggests that it may be prudent to simply monitor patients with asymptomatic CPAN.

In 1931, Lindberg1 described a cutaneous variant of polyarteritis nodosa, which lacked visceral involvement and possessed a more favorable prognosis.2 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN) is a localized small- to medium-vessel vasculitis restricted to the skin. Both benign and chronic courses have been described, and systemic involvement does not occur.3 Diagnostic criteria proposed by Nakamura et al3 in 2009 included cutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, purpura, or ulcers; histopathologic fibrinoid necrotizing vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels; and exclusion of systemic symptoms (eg, fever, hypertension, weight loss, renal failure, cerebral hemorrhage, neuropathy, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, pericarditis, pleuritis, arthralgia/myalgia). Nodules occur in 30% to 50% of cases and can remain for years if left untreated. Ulcerations occur in up to 30% of patients. Myositis, arthritis, and weakness also have been reported with this condition.4 Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa has been associated with abnormal antibody testing with elevations of antiphospholipid cofactor antibody, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2-glycoprotein I–dependent cardiolipin antibody, as well as elevated anti–phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibody.5 These antibodies suggest increased risk for thrombosis and systemic diseases such as lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue disease. The distinction of this entity from systemic polyartertitis nodosa is key when determining treatment options and monitoring parameters.

Case Report

A 66-year-old woman was referred to our facility by an outside dermatologist with a mildly pruritic, blanchable, reticulated erythema on the chest and bilateral arms and legs of 3 months’ duration consistent with livedo reticularis (Figure 1). Prior systemic therapy included prednisone 10 mg 3 times daily, fexofenadine, loratadine, and hydroxyzine. When the systemic steroid was tapered, the patient developed an asymptomatic flare of her eruption. On presentation, the lesions had waxed and waned, and the patient was taking only vitamin B12 and vitamin C. Her medical history was notable for an unknown-type lymphoma of the chest wall diagnosed at 46 years of age that was treated with an unknown chemotherapeutic agent, chronic pancreatitis that resulted in a duodenectomy at 61 years of age, chronic cholecystitis, and 1 first-trimester miscarriage. Outside laboratory tests, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, urinalysis, renal function, and liver function tests were within reference range, except for the finding of mild leukocytosis (11,000/µL)(reference range, 3800–10,800/µL), which resolved after steroids were discontinued, with otherwise normal results. Punch biopsy of a specimen from the right thigh revealed medium-vessel vasculitis consistent with polyarteritis nodosa (Figure 2). Laboratory workup by our facility including hepatitis panel, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, factor V Leiden, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, anticardiolipin antibody, and proteins C and S were all within reference range. Abnormal values included a low positive but nondiagnostic antinuclear antibody screen with negative titers, and the lupus anticoagulant titer was mildly elevated at 44 IgG binding units (reference range, <40 IgG binding units). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and urine protein electrophoresis also were performed, and SPEP was low positive for elevated κ and γ light chains. The patient was referred to oncology, and further testing revealed no underlying malignancy. The patient was monitored and no treatment was initiated; her rash completely resolved within 3 months. Laboratory monitoring at 6 months including SPEP, urine protein electrophoresis, lupus anticoagulant, and clotting studies all were within reference range.

Comment

Although the treatment of systemic polyarteritis nodosa often is necessary and typically involves high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, the treatment of CPAN initially is less aggressive. Of the options available for treatment of CPAN, each has associated risks and side effects. Chen6 classified CPAN into 3 groups: 1 (mild), 2 (severe with no systemic involvement), and 3 (severe with progression to systemic disease)(Table). The authors performed a review of all the published treatments and their respective side effects to evaluate if treatment should be instituted for asymptomatic (group 1) disease presenting with abnormal antibody findings as demonstrated in our case.

First-line treatment of CPAN includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and colchicine.7 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are preferred; however, they also have been associated with gastrointestinal tract upset and increased risk for peptic ulcer disease with long-term use. Although colchicine often is used in conjunction with NSAIDS8 for its anti-inflammatory activity, no studies have been performed on this drug as monotherapy, and the side effect of diarrhea often limits its use.

Other therapies include dapsone, which should be monitored carefully due to the risk for dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome.8,9 Topical corticosteroids have been proven effective for mild cases of confluent erythema with remission occurring as early as 4 weeks.4 Some reports emphasize the role of streptococcal infections in CPAN, especially in children.8,10-12 Consequently it is recommended that anti–streptolysin O titers should be included in the workup for CPAN. Long-term penicillin prophylaxis and tonsillectomy have been used to prevent disease flares with limited success.8,10-12

For more severe disease, especially with neuromuscular involvement, oral methylprednisolone up to 1 mg/kg daily has been used and has proven effective in the control of acute exacerbations.7,13 However, the many adverse effects of systemic steroids limit their use long-term, and taper will often result in flare of disease.4,7 Medications used in conjunction with steroids include hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, sulfapyridine, pentoxifylline, infliximab, etanercept, and intravenous immunoglobulin.4,9,12-17

Low-dose methotrexate has shown some improvement in skin disease with CPAN, but other case reports suggest that complete remission is not achieved with this drug.15,18 More studies are needed to assess the use of methotrexate for CPAN.

Immunomodulators have been used in multiple case reports with varying levels of success. Rogalski and Sticherling4 reported 3 cases that cleared with methylprednisolone plus azathioprine ranging from 4 weeks to 6 months; nausea limited tolerance of azathioprine in 1 case. Mycophenolate mofetil also was successfully used in 2 cases with clearance at 17 weeks and 6 months. In this series of cases, cyclosporine was ineffective for CPAN.4 Two case reports documented cutaneous clearance with cyclophosphamide in conjunction with prednisolone.9,10 No prospective trials have been performed on these medications, and immunosuppressants should only be considered in steroid-resistant cases.

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin has been reported effective in prior cases that showed resistance to more conventional trials of steroids, azathioprine, and/or cyclophosphamide.12,14 Intravenous immunoglobulin may be regarded as a treatment option for severe resistant disease. Several case reports also have documented success using tumor necrosis factor α blockers, particularly infliximab, as an adjunct to steroids and etanercept as both a steroid adjunct and monotherapy.16,17,19 More studies are necessary to evaluate these treatments.

Additionally, single case reports have outlined the use of other therapeutic agents, including tamoxifen (10 mg twice daily increased to 20 mg twice daily during episodes of breakthrough lesions),20 hyperbaric oxygen therapy (100% oxygen for 90 minutes 5 times weekly at 1.5 atm absolute followed by 2 weeks of 2 atm absolute),21 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (300 µg injection in small portion to ulcer edges twice monthly for 2 months).22 All of these treatments show promise, but data are limited.

Because thrombosis is postulated to be a potential mechanism leading to CPAN, agents such as pentoxifylline, clopidogrel, and warfarin have been examined as treatment options. Pentoxifylline in combination with mycophenolate mofetil has been successful in treating a case that was resistant to other immunosuppressants.23 Clopidogrel blocks the adenosine diphosphate pathway and impairs clot retraction. Clopidogrel was reported effective in an acute flare of CPAN for clearance of skin lesions and normalization of lupus anticoagulant.24 It also was used successfully in recurrent CPAN after steroid treatments in a patient with neuromuscular symptoms. There was no recurrence in either of the patients in this case report series. Warfarin therapy at an international normalized ratio of 3.0 also has demonstrated success in halting disease progression and in facilitating the resolution of skin changes and normalization of anti–phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibodies.24 Our review of the literature did not reveal evidence of a standardized length of treatment following symptom resolution or if treatment is indicated in asymptomatic disease, or as in our case, with only mild elevations of antiphospholipid antibodies.

Conclusion

Multiple treatment options exist for CPAN, but the data on their efficacies is limited and based only on anecdotal evidence, not prospective analysis. We believe that it seems reasonable to initiate treatment only for symptomatic disease or cases in which the antibody titers suggest that the patient may be at high risk for thrombosis. Mild symptoms and mild cutaneous changes would suggest the likely choice of NSAIDs, colchicine, or dapsone as treatment options versus no treatment. In patients with antibody titers, pentoxifylline, clopidogrel, or warfarin may be considered first-line therapies. With severe ulcerative lesions and neuromuscular involvement, steroids, immunosuppressants, and other investigative agents should be contemplated. In our patient, the laboratory studies were repeated and normalized on complete resolution of her livedo eruption. She remained asymptomatic and clear for 8 months without any treatment. The incidence of this presentation of CPAN is unknown and is likely underreported, as we would not expect most patients to present to their physicians for the evaluation of otherwise asymptomatic livedo reticularis. In essence, our case report suggests that it may be prudent to simply monitor patients with asymptomatic CPAN.

- Lindberg K. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Periarteritis nodosa. Acta Med Scand. 1931;76:183-225.

- Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa [published online August 26, 2005]. J Neurol. 2005;252:1155-1166.

- Nakamura T, Kanazawa N, Ikeda T, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: revisiting its definition and diagnostic criteria. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:117-121.

- Rogalski C, Sticherling M. Panateritis cutanea benigna—an entity limited to the skin or cutaneous presentation of a systemic necrotizing vasculitis? report of seven cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:817-821.

- Kawakami T, Yamazaki M, Mizoguchi M, et al. High titer of anti-phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibodies in patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1507-1513.

- Chen KR. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a clinical and histopathological study of 20 cases. J Dermatol. 1989;6:429-442.

- Morgan AJ, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a comprehensive review. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:750-756.

- Ishiguro N, Kawashima M. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a report of 16 cases with clinical and histopathologic analysis and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2010;37:85-93.

- Flanagan N, Casey EB, Watson R, et al. Cutaneous polyartertitis nodosa with seronegative arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:1161-1162.

- Fathalla B, Miller L, Brady S, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:724-728.

- Misago N, Mochizuki Y, Sekiyama-Kodera H, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: therapy and clinical course in four cases. J Dermatol. 2001;28:719-727.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins for cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa resistant to conventional treatment. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45:169-170.

- Maillard H, Szczesniak S, Martin L. Cutaneous periarteritis nodosa: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of 9 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;26:125-129.

- Lobo I, Ferreira M, Silva E. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;22:880-882.

- Boehm I, Bauer R. Low-dose methotrexate controls a severe form of polyarteritis nodosa. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:167-169.

- Campanilho-Marques R, Ramos F, Canhão H, et al. Remission induced by infliximab in a childhood polyarteritis nodosa refractory to conventional immunosuppression and rituximab. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:277-278.

- Inoue N, Shimizu M, Mizuta M, et al. Refractory cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: successful treatment with etanercept. Pediatr Int. 2017;59:751-752.

- Schartz NE. Successful treatment in two cases of steroid dependent cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa with low-dose methotrexate. Dermatology. 2001;203:336-338.

- Valor L, Monteagudo I, de la Torre I, et al. Young male patient diagnosed with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa successfully treated with etanercept. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:688-689.

- Cvancara JL, Meffert JJ, Elston DM. Estrogen sensitive cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: response to tamoxifen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:643-646.

- Mazokopakis E, Milkas A, Tsartsalis A, et al. Improvement of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa with hyperbaric oxygen. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1017-1029.

- Tursen U, Api H, Kaya TI, et al. Rapid healing of chronic leg ulcers during perilesional injections of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor in a patient with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1341-1343.

- Kluger N, Guillot B, Bessis D. Ulcerative cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with mycophenolate mofetil and pentoxifylline. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:175-177.

- Kawakami T, Soma Y. Use of warfarin therapy at a target international normalized ratio of 3.0 for cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:602-606.

- Lindberg K. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Periarteritis nodosa. Acta Med Scand. 1931;76:183-225.

- Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa [published online August 26, 2005]. J Neurol. 2005;252:1155-1166.

- Nakamura T, Kanazawa N, Ikeda T, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: revisiting its definition and diagnostic criteria. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:117-121.

- Rogalski C, Sticherling M. Panateritis cutanea benigna—an entity limited to the skin or cutaneous presentation of a systemic necrotizing vasculitis? report of seven cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:817-821.

- Kawakami T, Yamazaki M, Mizoguchi M, et al. High titer of anti-phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex antibodies in patients with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1507-1513.

- Chen KR. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a clinical and histopathological study of 20 cases. J Dermatol. 1989;6:429-442.

- Morgan AJ, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a comprehensive review. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:750-756.

- Ishiguro N, Kawashima M. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a report of 16 cases with clinical and histopathologic analysis and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2010;37:85-93.

- Flanagan N, Casey EB, Watson R, et al. Cutaneous polyartertitis nodosa with seronegative arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:1161-1162.

- Fathalla B, Miller L, Brady S, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:724-728.

- Misago N, Mochizuki Y, Sekiyama-Kodera H, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: therapy and clinical course in four cases. J Dermatol. 2001;28:719-727.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins for cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa resistant to conventional treatment. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45:169-170.

- Maillard H, Szczesniak S, Martin L. Cutaneous periarteritis nodosa: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of 9 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;26:125-129.

- Lobo I, Ferreira M, Silva E. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;22:880-882.

- Boehm I, Bauer R. Low-dose methotrexate controls a severe form of polyarteritis nodosa. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:167-169.

- Campanilho-Marques R, Ramos F, Canhão H, et al. Remission induced by infliximab in a childhood polyarteritis nodosa refractory to conventional immunosuppression and rituximab. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:277-278.

- Inoue N, Shimizu M, Mizuta M, et al. Refractory cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: successful treatment with etanercept. Pediatr Int. 2017;59:751-752.

- Schartz NE. Successful treatment in two cases of steroid dependent cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa with low-dose methotrexate. Dermatology. 2001;203:336-338.

- Valor L, Monteagudo I, de la Torre I, et al. Young male patient diagnosed with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa successfully treated with etanercept. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:688-689.

- Cvancara JL, Meffert JJ, Elston DM. Estrogen sensitive cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: response to tamoxifen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:643-646.

- Mazokopakis E, Milkas A, Tsartsalis A, et al. Improvement of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa with hyperbaric oxygen. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1017-1029.

- Tursen U, Api H, Kaya TI, et al. Rapid healing of chronic leg ulcers during perilesional injections of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor in a patient with cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1341-1343.

- Kluger N, Guillot B, Bessis D. Ulcerative cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with mycophenolate mofetil and pentoxifylline. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:175-177.

- Kawakami T, Soma Y. Use of warfarin therapy at a target international normalized ratio of 3.0 for cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:602-606.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa should be in the differential of new-onset livedo reticularis.

- Workup with biopsy and specific blood work is important.

- Treatment options at this time are limited.

Necrotic Ulcer on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis, and therapy [published online November 25, 2016]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13-24.

- Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity [published online January 17, 2003]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous cryptococcus infection and AIDS: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Korfel A, Menssen HD, Schwartz S, et al. Cryptococcosis in Hodgkin's disease: description of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:283-286.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.