User login

Dapagliflozin Improves Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the effects of dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes.

Design. Multicenter, international, double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting and participants. Adult patients with symptomatic heart failure with an ejection fraction of 40% or less and elevated heart failure biomarkers who were already on appropriate guideline-directed therapies were eligible for the study.

Intervention. A total of 4744 patients were randomly assigned to receive dapagliflozin (10 mg once daily) or placebo, in addition to recommended therapy. Randomization was stratified by the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was the composite of a first episode of worsening heart failure (hospitalization or urgent intravenous therapy) or cardiovascular death.

Main results. Median follow-up was 18.2 months; during this time, the primary outcome occurred in 16.3% (386 of 2373) of patients in the dapagliflozin group and in 21.2% (502 of 2371) of patients in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-0.85; P < 0.001). In the dapagliflozin group, 237 patients (10.0%) experienced a first worsening heart failure event, as compared with 326 patients (13.7%) in the placebo group (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.59-0.83). The dapagliflozin group hadlower rates of death from cardiovascular causes (9.6% vs 11.5%; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.98) and from any causes (11.6% vs 13.9%; HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.71-0.97), compared to the placebo group. Findings in patients with diabetes were similar to those in patients without diabetes.

Conclusion. Among patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction, the risk of worsening heart failure or death from cardiovascular causes was lower among those who received dapagliflozin than among those who received placebo, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes.

Commentary

Inhibitors of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) are a novel class of diabetic medication that decrease renal glucose reabsorption, thereby increasing urinary glucose excretion. In several large clinical trials of these medications for patients with diabetes, which were designed to meet the regulatory requirements for cardiovascular safety in novel diabetic agents, investigators unexpectedly found that SGLT-2 inhibitors were associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events, driven by a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. The results of EMPA-REG OUTCOME, the first of these trials, showed significantly lower risks of both death from any cause and hospitalization for heart failure in patients treated with empagliflozin.1 This improvement in cardiovascular outcomes was subsequently confirmed as a class effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors in the CANVAS Program (canagliflozin) and DECLARE TIMI 58 (dapagliflozin) trials.2,3

While these trials were designed for patients with type 2 diabetes who had either established cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors for it, most patients did not have heart failure at baseline. Accordingly, despite a signal toward benefit of SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure, the trials were not powered to test the hypothesis that SGLT-2 inhibitors benefit patients with heart failure, regardless of diabetes status. Therefore, McMurray et al designed the DAPA-HF trial to investigate whether SGLT-2 inhibitors can improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, with or without diabetes. The trial included 4744 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, who were randomly assigned to dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily or placebo, atop guideline-directed heart failure therapy, with randomization stratified by presence or absence of type 2 diabetes. Investigators found that the composite primary outcome, a first episode of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death, occurred less frequently in patients in the dapagliflozin group compared to the placebo group (16.3% vs 21.2%; HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.65-0.85; P < 0.001). Individual components of the primary outcome and death from any cause were all significantly lower, and heart failure–related quality of life was significantly improved in the dapagliflozin group compared to placebo.

DAPA-HF was the first randomized study to investigate the effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on patients with heart failure regardless of the presence of diabetes. In addition to the reduction in the above-mentioned primary and secondary endpoints, the study yielded other important findings worth noting. First, the consistent benefit of dapagliflozin on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with and without diabetes suggests that the cardioprotective effect of dapagliflozin is independent of its glucose-lowering effect. Prior studies have proposed alternative mechanisms, such as diuretic function and related hemodynamic actions, effects on myocardial metabolism, ion transporters, fibrosis, adipokines, vascular function, and the preservation of renal function. Future studies are needed to fully understand the likely pleiotropic effects of this class of medication on patients with heart failure. Second, there was no difference in the safety endpoints between the groups, including renal adverse events and major hypoglycemia, implying dapagliflozin is as safe as placebo.

There are a few limitations of this trial. First, as the authors point out, the study included mostly white males—less than 5% of participants were African Americans—and the finding may not be generalizable to all patient populations. Second, although all patients were already treated with guideline-directed heart failure therapy, only 10% of patients were on sacubitril–valsartan, which is more effective than renin–angiotensin system blockade alone at reducing the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure and death from cardiovascular causes. Also, mineralocorticoid receptor blockers were used in only 70% of the population. Finally, since the doses were not provided, whether patients were on the maximal tolerated dose of heart failure therapy prior to enrollment is unclear.

Based on the results of the DAPA-HF trial, the Food and Drug Administration approved dapagliflozin for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction on May 5, 2020. This is the first diabetic drug approved for the treatment of heart failure.

Applications for Clinical Practice

SGLT-2 inhibitors represent a fourth class of medication that patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction should be initiated on, in addition to beta blocker, ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker/neprilysin inhibitor, and mineralocorticoid receptor blocker. SGLT-2 inhibitors may be especially applicable in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and relative hypotension, as these agents are not associated with a significant blood-pressure-lowering effect, which can often limit our ability to initiate or uptitrate the other main 3 classes of guideline-directed medical therapy.

—Rie Hirai, MD, Fukui Kosei Hospital, Fukui, Japan

—Taishi Hirai, MD, University of Missouri Medical Center, Columbia, MO

—Timothy Fendler, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO

1. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117-2128.

2. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:644-657.

3. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347-357.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the effects of dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes.

Design. Multicenter, international, double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting and participants. Adult patients with symptomatic heart failure with an ejection fraction of 40% or less and elevated heart failure biomarkers who were already on appropriate guideline-directed therapies were eligible for the study.

Intervention. A total of 4744 patients were randomly assigned to receive dapagliflozin (10 mg once daily) or placebo, in addition to recommended therapy. Randomization was stratified by the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was the composite of a first episode of worsening heart failure (hospitalization or urgent intravenous therapy) or cardiovascular death.

Main results. Median follow-up was 18.2 months; during this time, the primary outcome occurred in 16.3% (386 of 2373) of patients in the dapagliflozin group and in 21.2% (502 of 2371) of patients in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-0.85; P < 0.001). In the dapagliflozin group, 237 patients (10.0%) experienced a first worsening heart failure event, as compared with 326 patients (13.7%) in the placebo group (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.59-0.83). The dapagliflozin group hadlower rates of death from cardiovascular causes (9.6% vs 11.5%; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.98) and from any causes (11.6% vs 13.9%; HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.71-0.97), compared to the placebo group. Findings in patients with diabetes were similar to those in patients without diabetes.

Conclusion. Among patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction, the risk of worsening heart failure or death from cardiovascular causes was lower among those who received dapagliflozin than among those who received placebo, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes.

Commentary

Inhibitors of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) are a novel class of diabetic medication that decrease renal glucose reabsorption, thereby increasing urinary glucose excretion. In several large clinical trials of these medications for patients with diabetes, which were designed to meet the regulatory requirements for cardiovascular safety in novel diabetic agents, investigators unexpectedly found that SGLT-2 inhibitors were associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events, driven by a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. The results of EMPA-REG OUTCOME, the first of these trials, showed significantly lower risks of both death from any cause and hospitalization for heart failure in patients treated with empagliflozin.1 This improvement in cardiovascular outcomes was subsequently confirmed as a class effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors in the CANVAS Program (canagliflozin) and DECLARE TIMI 58 (dapagliflozin) trials.2,3

While these trials were designed for patients with type 2 diabetes who had either established cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors for it, most patients did not have heart failure at baseline. Accordingly, despite a signal toward benefit of SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure, the trials were not powered to test the hypothesis that SGLT-2 inhibitors benefit patients with heart failure, regardless of diabetes status. Therefore, McMurray et al designed the DAPA-HF trial to investigate whether SGLT-2 inhibitors can improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, with or without diabetes. The trial included 4744 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, who were randomly assigned to dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily or placebo, atop guideline-directed heart failure therapy, with randomization stratified by presence or absence of type 2 diabetes. Investigators found that the composite primary outcome, a first episode of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death, occurred less frequently in patients in the dapagliflozin group compared to the placebo group (16.3% vs 21.2%; HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.65-0.85; P < 0.001). Individual components of the primary outcome and death from any cause were all significantly lower, and heart failure–related quality of life was significantly improved in the dapagliflozin group compared to placebo.

DAPA-HF was the first randomized study to investigate the effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on patients with heart failure regardless of the presence of diabetes. In addition to the reduction in the above-mentioned primary and secondary endpoints, the study yielded other important findings worth noting. First, the consistent benefit of dapagliflozin on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with and without diabetes suggests that the cardioprotective effect of dapagliflozin is independent of its glucose-lowering effect. Prior studies have proposed alternative mechanisms, such as diuretic function and related hemodynamic actions, effects on myocardial metabolism, ion transporters, fibrosis, adipokines, vascular function, and the preservation of renal function. Future studies are needed to fully understand the likely pleiotropic effects of this class of medication on patients with heart failure. Second, there was no difference in the safety endpoints between the groups, including renal adverse events and major hypoglycemia, implying dapagliflozin is as safe as placebo.

There are a few limitations of this trial. First, as the authors point out, the study included mostly white males—less than 5% of participants were African Americans—and the finding may not be generalizable to all patient populations. Second, although all patients were already treated with guideline-directed heart failure therapy, only 10% of patients were on sacubitril–valsartan, which is more effective than renin–angiotensin system blockade alone at reducing the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure and death from cardiovascular causes. Also, mineralocorticoid receptor blockers were used in only 70% of the population. Finally, since the doses were not provided, whether patients were on the maximal tolerated dose of heart failure therapy prior to enrollment is unclear.

Based on the results of the DAPA-HF trial, the Food and Drug Administration approved dapagliflozin for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction on May 5, 2020. This is the first diabetic drug approved for the treatment of heart failure.

Applications for Clinical Practice

SGLT-2 inhibitors represent a fourth class of medication that patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction should be initiated on, in addition to beta blocker, ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker/neprilysin inhibitor, and mineralocorticoid receptor blocker. SGLT-2 inhibitors may be especially applicable in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and relative hypotension, as these agents are not associated with a significant blood-pressure-lowering effect, which can often limit our ability to initiate or uptitrate the other main 3 classes of guideline-directed medical therapy.

—Rie Hirai, MD, Fukui Kosei Hospital, Fukui, Japan

—Taishi Hirai, MD, University of Missouri Medical Center, Columbia, MO

—Timothy Fendler, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the effects of dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes.

Design. Multicenter, international, double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting and participants. Adult patients with symptomatic heart failure with an ejection fraction of 40% or less and elevated heart failure biomarkers who were already on appropriate guideline-directed therapies were eligible for the study.

Intervention. A total of 4744 patients were randomly assigned to receive dapagliflozin (10 mg once daily) or placebo, in addition to recommended therapy. Randomization was stratified by the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was the composite of a first episode of worsening heart failure (hospitalization or urgent intravenous therapy) or cardiovascular death.

Main results. Median follow-up was 18.2 months; during this time, the primary outcome occurred in 16.3% (386 of 2373) of patients in the dapagliflozin group and in 21.2% (502 of 2371) of patients in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-0.85; P < 0.001). In the dapagliflozin group, 237 patients (10.0%) experienced a first worsening heart failure event, as compared with 326 patients (13.7%) in the placebo group (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.59-0.83). The dapagliflozin group hadlower rates of death from cardiovascular causes (9.6% vs 11.5%; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.98) and from any causes (11.6% vs 13.9%; HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.71-0.97), compared to the placebo group. Findings in patients with diabetes were similar to those in patients without diabetes.

Conclusion. Among patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction, the risk of worsening heart failure or death from cardiovascular causes was lower among those who received dapagliflozin than among those who received placebo, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes.

Commentary

Inhibitors of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) are a novel class of diabetic medication that decrease renal glucose reabsorption, thereby increasing urinary glucose excretion. In several large clinical trials of these medications for patients with diabetes, which were designed to meet the regulatory requirements for cardiovascular safety in novel diabetic agents, investigators unexpectedly found that SGLT-2 inhibitors were associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events, driven by a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. The results of EMPA-REG OUTCOME, the first of these trials, showed significantly lower risks of both death from any cause and hospitalization for heart failure in patients treated with empagliflozin.1 This improvement in cardiovascular outcomes was subsequently confirmed as a class effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors in the CANVAS Program (canagliflozin) and DECLARE TIMI 58 (dapagliflozin) trials.2,3

While these trials were designed for patients with type 2 diabetes who had either established cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors for it, most patients did not have heart failure at baseline. Accordingly, despite a signal toward benefit of SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure, the trials were not powered to test the hypothesis that SGLT-2 inhibitors benefit patients with heart failure, regardless of diabetes status. Therefore, McMurray et al designed the DAPA-HF trial to investigate whether SGLT-2 inhibitors can improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, with or without diabetes. The trial included 4744 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, who were randomly assigned to dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily or placebo, atop guideline-directed heart failure therapy, with randomization stratified by presence or absence of type 2 diabetes. Investigators found that the composite primary outcome, a first episode of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death, occurred less frequently in patients in the dapagliflozin group compared to the placebo group (16.3% vs 21.2%; HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.65-0.85; P < 0.001). Individual components of the primary outcome and death from any cause were all significantly lower, and heart failure–related quality of life was significantly improved in the dapagliflozin group compared to placebo.

DAPA-HF was the first randomized study to investigate the effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on patients with heart failure regardless of the presence of diabetes. In addition to the reduction in the above-mentioned primary and secondary endpoints, the study yielded other important findings worth noting. First, the consistent benefit of dapagliflozin on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with and without diabetes suggests that the cardioprotective effect of dapagliflozin is independent of its glucose-lowering effect. Prior studies have proposed alternative mechanisms, such as diuretic function and related hemodynamic actions, effects on myocardial metabolism, ion transporters, fibrosis, adipokines, vascular function, and the preservation of renal function. Future studies are needed to fully understand the likely pleiotropic effects of this class of medication on patients with heart failure. Second, there was no difference in the safety endpoints between the groups, including renal adverse events and major hypoglycemia, implying dapagliflozin is as safe as placebo.

There are a few limitations of this trial. First, as the authors point out, the study included mostly white males—less than 5% of participants were African Americans—and the finding may not be generalizable to all patient populations. Second, although all patients were already treated with guideline-directed heart failure therapy, only 10% of patients were on sacubitril–valsartan, which is more effective than renin–angiotensin system blockade alone at reducing the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure and death from cardiovascular causes. Also, mineralocorticoid receptor blockers were used in only 70% of the population. Finally, since the doses were not provided, whether patients were on the maximal tolerated dose of heart failure therapy prior to enrollment is unclear.

Based on the results of the DAPA-HF trial, the Food and Drug Administration approved dapagliflozin for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction on May 5, 2020. This is the first diabetic drug approved for the treatment of heart failure.

Applications for Clinical Practice

SGLT-2 inhibitors represent a fourth class of medication that patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction should be initiated on, in addition to beta blocker, ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker/neprilysin inhibitor, and mineralocorticoid receptor blocker. SGLT-2 inhibitors may be especially applicable in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and relative hypotension, as these agents are not associated with a significant blood-pressure-lowering effect, which can often limit our ability to initiate or uptitrate the other main 3 classes of guideline-directed medical therapy.

—Rie Hirai, MD, Fukui Kosei Hospital, Fukui, Japan

—Taishi Hirai, MD, University of Missouri Medical Center, Columbia, MO

—Timothy Fendler, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO

1. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117-2128.

2. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:644-657.

3. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347-357.

1. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117-2128.

2. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:644-657.

3. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347-357.

Part 5: Screening for “Opathies” in Diabetes Patients

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

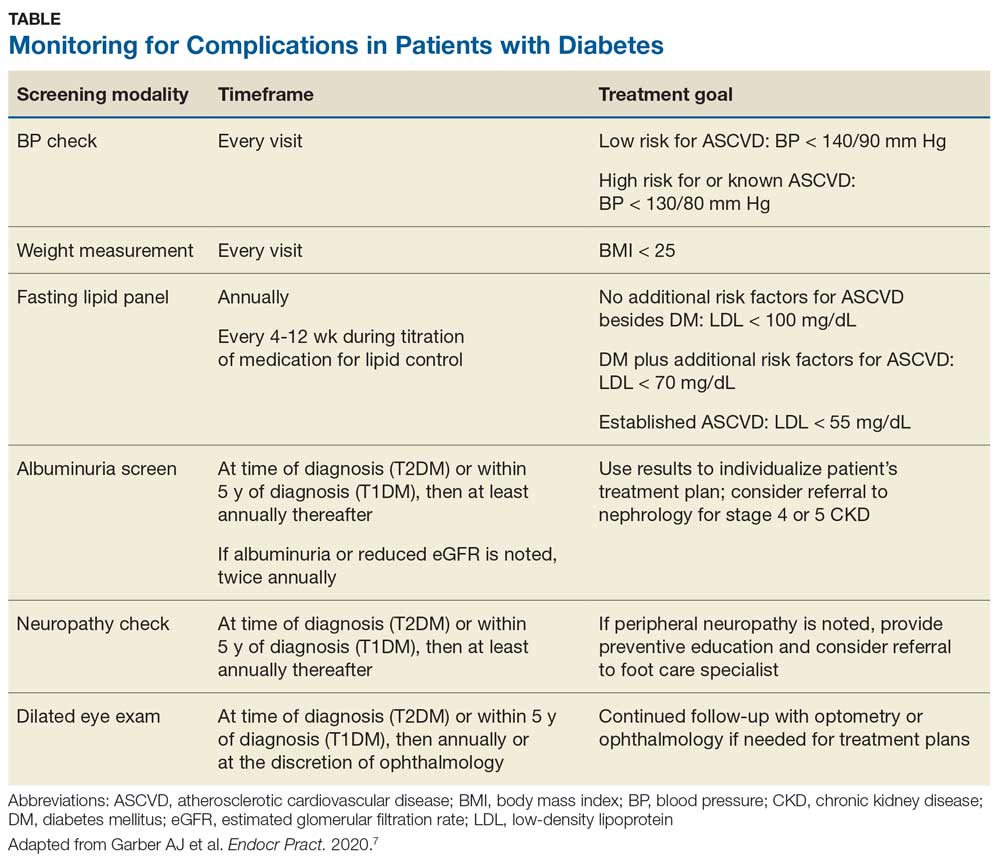

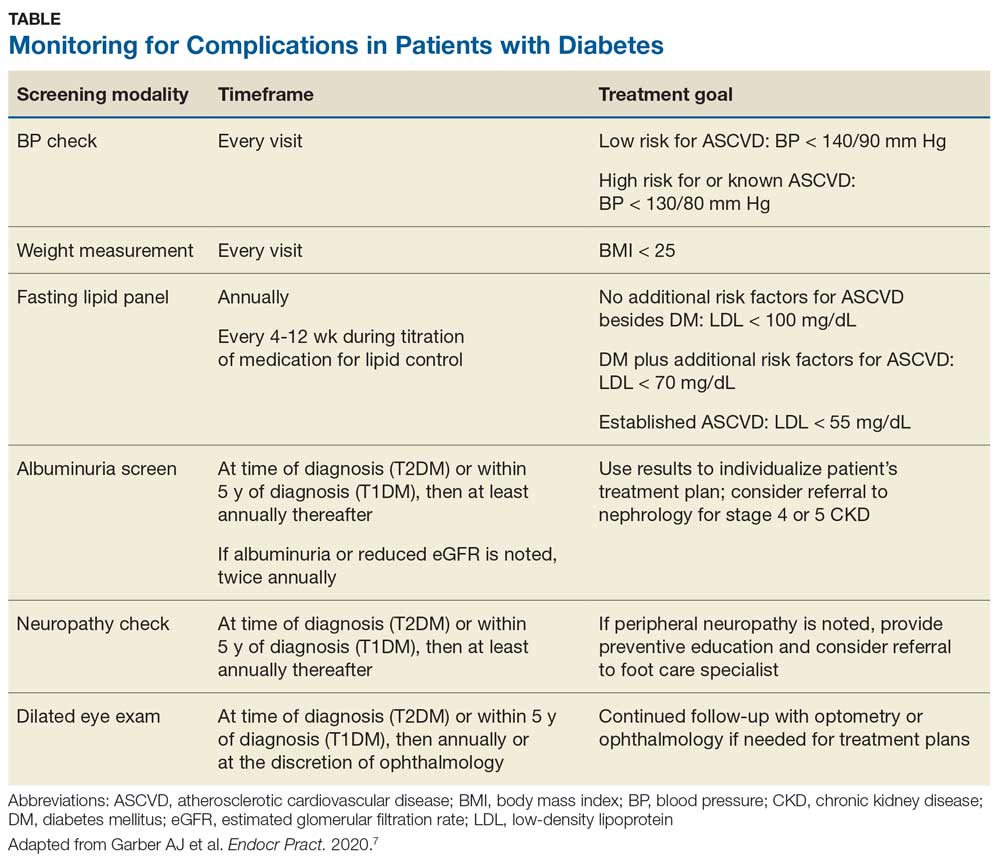

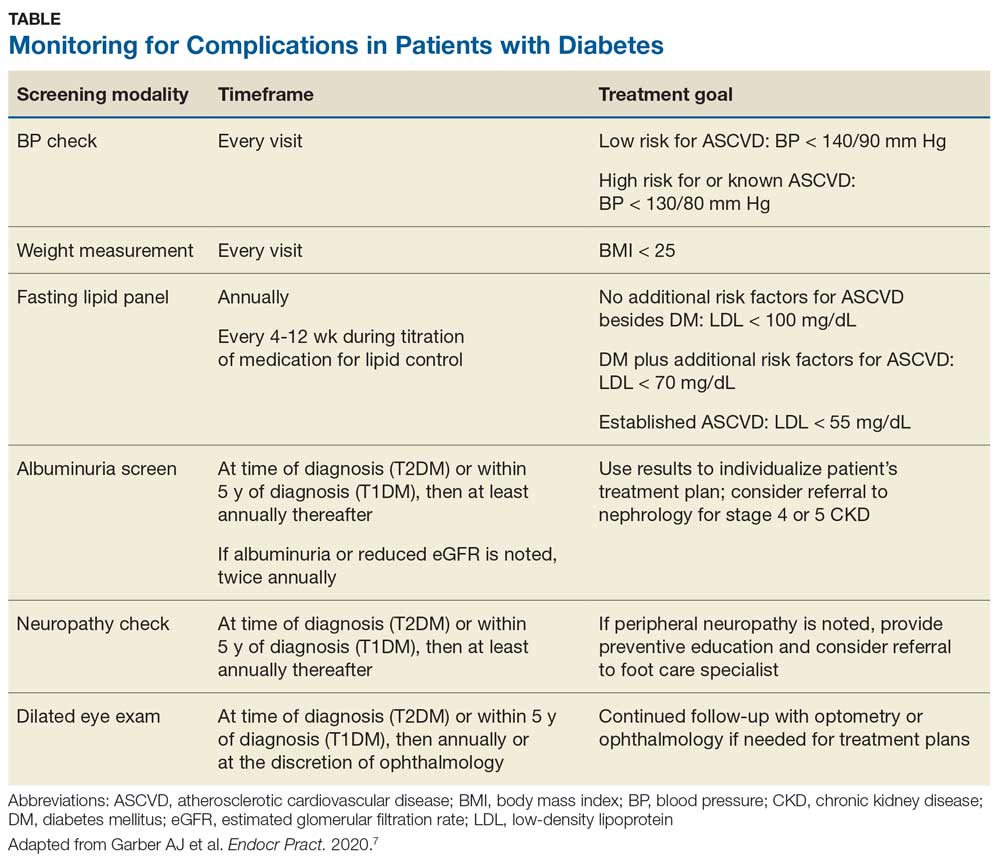

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

Cleaner data confirm severe COVID-19 link to diabetes, hypertension

Further refinement of data from patients hospitalized worldwide for COVID-19 disease showed a 12% prevalence rate of patients with diabetes in this population and a 17% prevalence rate for hypertension.

These are lower rates than previously reported for COVID-19 patients with either of these two comorbidities, yet the findings still document important epidemiologic links between diabetes, hypertension, and COVID-19, said the study’s authors.

A meta-analysis of data from 15,794 patients hospitalized because of COVID-19 disease that was drawn from 65 carefully curated reports published from December 1, 2019, to April 6, 2020, also showed that, among the hospitalized COVID-19 patients with diabetes (either type 1 or type 2), the rate of patients who required ICU admission was 96% higher than among those without diabetes and mortality was 2.78-fold higher, both statistically significant differences.

The rate of ICU admissions among those hospitalized with COVID-19 who also had hypertension was 2.95-fold above those without hypertension, and mortality was 2.39-fold higher, also statistically significant differences, reported a team of researchers in the recently published report.

The new meta-analysis was notable for the extra effort investigators employed to eliminate duplicated patients from their database of COVID-19 patients included in various published reports, a potential source of bias that likely introduced errors into prior meta-analyses that used similar data. “We found an overwhelming proportion of studies at high risk of data repetition,” the report said. Virtually all of the included studies were retrospective case studies, nearly two-thirds had data from a single center, and 71% of the studies included only patients in China.

“We developed a method to identify reports that had a high risk for repetitions” of included patients, said Fady Hannah-Shmouni, MD, a senior author of the study. “We also used methods to minimize bias, we excluded certain patients populations, and we applied a uniform definition of COVID-19 disease severity,” specifically patients who died or needed ICU admission, because the definitions used originally by many of the reports were very heterogeneous, said Dr. Hannah-Shmouni, principal investigator for Endocrine, Genetics, and Hypertension at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Despite the effort to eliminate case duplications, the analysis remains subject to additional confounders, in part because of a lack of comprehensive patient information on factors such as smoking, body mass index, socioeconomic status, and the specific type of diabetes or hypertension a patient had. “Even with these limitations, we were able to show that the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes is elevated in patients with COVID-19, that patients with diabetes have increased risk for both death and ICU admissions, and that there is the potential for reverse causality in the reporting of hypertension as a risk factor for COVID-19,” Dr. Hannah-Shmouni said in an interview. “We believe the explosion of data that associated hypertension and COVID-19 may be partially the result of reverse causality.”

One possible example of this reverse causality is the overlap between hypertension and age as potential risk factors for COVID-19 disease or increased infection severity. People “older than 80 frequently develop severe disease if infected with the novel coronavirus, and 80% of people older than 80 have hypertension, so it’s not surprising that hypertension is highly prevalent among hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” but this “does not imply a causal relationship between hypertension and severe COVID-19; the risk of hypertension probably depends on older age,” noted Ernesto L. Schiffrin, MD, a coauthor of the study, as well as professor of medicine at McGill University and director of the Hypertension and Vascular Research Unit at the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, both in Montreal. “My current opinion, on the basis of the totality of data, is that hypertension does not worsen [COVID-19] outcomes, but patients who are elderly, obese, diabetic, or immunocompromised are susceptible to more severe COVID-19 and worse outcomes,” said Dr. Schiffrin in an interview.

The new findings show “there is certainly an interplay between the virus, diabetes, and hypertension and other risk factors,” and while still limited by biases, the new findings “get closer” to correctly estimating the COVID-19 risks associated with these comorbidities,” Dr. Hannah-Shmouni said.

The connections identified between COVID-19, diabetes, and hypertension mean that patients with these chronic diseases should receive education about their COVID-19 risks and should have adequate access to the drugs and supplies they need to control blood pressure and hyperglycemia. Patients with diabetes also need to be current on vaccinations to reduce their risk for pneumonia. And recognition of the heightened COVID-19 risk for people with these comorbidities is important among people who work in relevant government agencies, health care workers, and patient advocacy groups, he added.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Hannah-Shmouni and Dr. Schiffrin had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Barrera FJ et al. J Endocn Soc. 2020 July 21. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa102.

Further refinement of data from patients hospitalized worldwide for COVID-19 disease showed a 12% prevalence rate of patients with diabetes in this population and a 17% prevalence rate for hypertension.

These are lower rates than previously reported for COVID-19 patients with either of these two comorbidities, yet the findings still document important epidemiologic links between diabetes, hypertension, and COVID-19, said the study’s authors.

A meta-analysis of data from 15,794 patients hospitalized because of COVID-19 disease that was drawn from 65 carefully curated reports published from December 1, 2019, to April 6, 2020, also showed that, among the hospitalized COVID-19 patients with diabetes (either type 1 or type 2), the rate of patients who required ICU admission was 96% higher than among those without diabetes and mortality was 2.78-fold higher, both statistically significant differences.

The rate of ICU admissions among those hospitalized with COVID-19 who also had hypertension was 2.95-fold above those without hypertension, and mortality was 2.39-fold higher, also statistically significant differences, reported a team of researchers in the recently published report.

The new meta-analysis was notable for the extra effort investigators employed to eliminate duplicated patients from their database of COVID-19 patients included in various published reports, a potential source of bias that likely introduced errors into prior meta-analyses that used similar data. “We found an overwhelming proportion of studies at high risk of data repetition,” the report said. Virtually all of the included studies were retrospective case studies, nearly two-thirds had data from a single center, and 71% of the studies included only patients in China.

“We developed a method to identify reports that had a high risk for repetitions” of included patients, said Fady Hannah-Shmouni, MD, a senior author of the study. “We also used methods to minimize bias, we excluded certain patients populations, and we applied a uniform definition of COVID-19 disease severity,” specifically patients who died or needed ICU admission, because the definitions used originally by many of the reports were very heterogeneous, said Dr. Hannah-Shmouni, principal investigator for Endocrine, Genetics, and Hypertension at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Despite the effort to eliminate case duplications, the analysis remains subject to additional confounders, in part because of a lack of comprehensive patient information on factors such as smoking, body mass index, socioeconomic status, and the specific type of diabetes or hypertension a patient had. “Even with these limitations, we were able to show that the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes is elevated in patients with COVID-19, that patients with diabetes have increased risk for both death and ICU admissions, and that there is the potential for reverse causality in the reporting of hypertension as a risk factor for COVID-19,” Dr. Hannah-Shmouni said in an interview. “We believe the explosion of data that associated hypertension and COVID-19 may be partially the result of reverse causality.”

One possible example of this reverse causality is the overlap between hypertension and age as potential risk factors for COVID-19 disease or increased infection severity. People “older than 80 frequently develop severe disease if infected with the novel coronavirus, and 80% of people older than 80 have hypertension, so it’s not surprising that hypertension is highly prevalent among hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” but this “does not imply a causal relationship between hypertension and severe COVID-19; the risk of hypertension probably depends on older age,” noted Ernesto L. Schiffrin, MD, a coauthor of the study, as well as professor of medicine at McGill University and director of the Hypertension and Vascular Research Unit at the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, both in Montreal. “My current opinion, on the basis of the totality of data, is that hypertension does not worsen [COVID-19] outcomes, but patients who are elderly, obese, diabetic, or immunocompromised are susceptible to more severe COVID-19 and worse outcomes,” said Dr. Schiffrin in an interview.

The new findings show “there is certainly an interplay between the virus, diabetes, and hypertension and other risk factors,” and while still limited by biases, the new findings “get closer” to correctly estimating the COVID-19 risks associated with these comorbidities,” Dr. Hannah-Shmouni said.

The connections identified between COVID-19, diabetes, and hypertension mean that patients with these chronic diseases should receive education about their COVID-19 risks and should have adequate access to the drugs and supplies they need to control blood pressure and hyperglycemia. Patients with diabetes also need to be current on vaccinations to reduce their risk for pneumonia. And recognition of the heightened COVID-19 risk for people with these comorbidities is important among people who work in relevant government agencies, health care workers, and patient advocacy groups, he added.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Hannah-Shmouni and Dr. Schiffrin had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Barrera FJ et al. J Endocn Soc. 2020 July 21. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa102.

Further refinement of data from patients hospitalized worldwide for COVID-19 disease showed a 12% prevalence rate of patients with diabetes in this population and a 17% prevalence rate for hypertension.

These are lower rates than previously reported for COVID-19 patients with either of these two comorbidities, yet the findings still document important epidemiologic links between diabetes, hypertension, and COVID-19, said the study’s authors.

A meta-analysis of data from 15,794 patients hospitalized because of COVID-19 disease that was drawn from 65 carefully curated reports published from December 1, 2019, to April 6, 2020, also showed that, among the hospitalized COVID-19 patients with diabetes (either type 1 or type 2), the rate of patients who required ICU admission was 96% higher than among those without diabetes and mortality was 2.78-fold higher, both statistically significant differences.

The rate of ICU admissions among those hospitalized with COVID-19 who also had hypertension was 2.95-fold above those without hypertension, and mortality was 2.39-fold higher, also statistically significant differences, reported a team of researchers in the recently published report.

The new meta-analysis was notable for the extra effort investigators employed to eliminate duplicated patients from their database of COVID-19 patients included in various published reports, a potential source of bias that likely introduced errors into prior meta-analyses that used similar data. “We found an overwhelming proportion of studies at high risk of data repetition,” the report said. Virtually all of the included studies were retrospective case studies, nearly two-thirds had data from a single center, and 71% of the studies included only patients in China.

“We developed a method to identify reports that had a high risk for repetitions” of included patients, said Fady Hannah-Shmouni, MD, a senior author of the study. “We also used methods to minimize bias, we excluded certain patients populations, and we applied a uniform definition of COVID-19 disease severity,” specifically patients who died or needed ICU admission, because the definitions used originally by many of the reports were very heterogeneous, said Dr. Hannah-Shmouni, principal investigator for Endocrine, Genetics, and Hypertension at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Despite the effort to eliminate case duplications, the analysis remains subject to additional confounders, in part because of a lack of comprehensive patient information on factors such as smoking, body mass index, socioeconomic status, and the specific type of diabetes or hypertension a patient had. “Even with these limitations, we were able to show that the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes is elevated in patients with COVID-19, that patients with diabetes have increased risk for both death and ICU admissions, and that there is the potential for reverse causality in the reporting of hypertension as a risk factor for COVID-19,” Dr. Hannah-Shmouni said in an interview. “We believe the explosion of data that associated hypertension and COVID-19 may be partially the result of reverse causality.”

One possible example of this reverse causality is the overlap between hypertension and age as potential risk factors for COVID-19 disease or increased infection severity. People “older than 80 frequently develop severe disease if infected with the novel coronavirus, and 80% of people older than 80 have hypertension, so it’s not surprising that hypertension is highly prevalent among hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” but this “does not imply a causal relationship between hypertension and severe COVID-19; the risk of hypertension probably depends on older age,” noted Ernesto L. Schiffrin, MD, a coauthor of the study, as well as professor of medicine at McGill University and director of the Hypertension and Vascular Research Unit at the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, both in Montreal. “My current opinion, on the basis of the totality of data, is that hypertension does not worsen [COVID-19] outcomes, but patients who are elderly, obese, diabetic, or immunocompromised are susceptible to more severe COVID-19 and worse outcomes,” said Dr. Schiffrin in an interview.