User login

Multidisciplinary Amputation Prevention at the DeBakey VA Hospital: Our First Decade

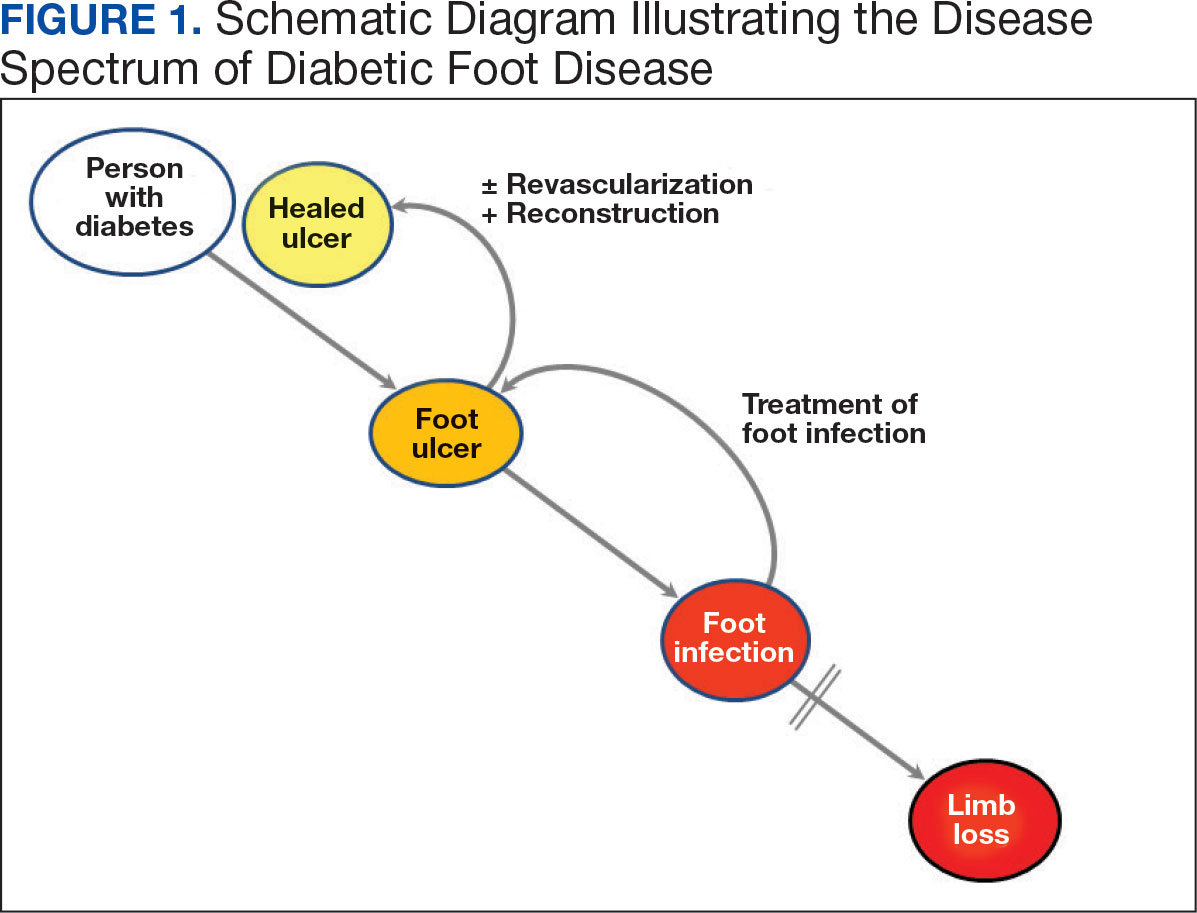

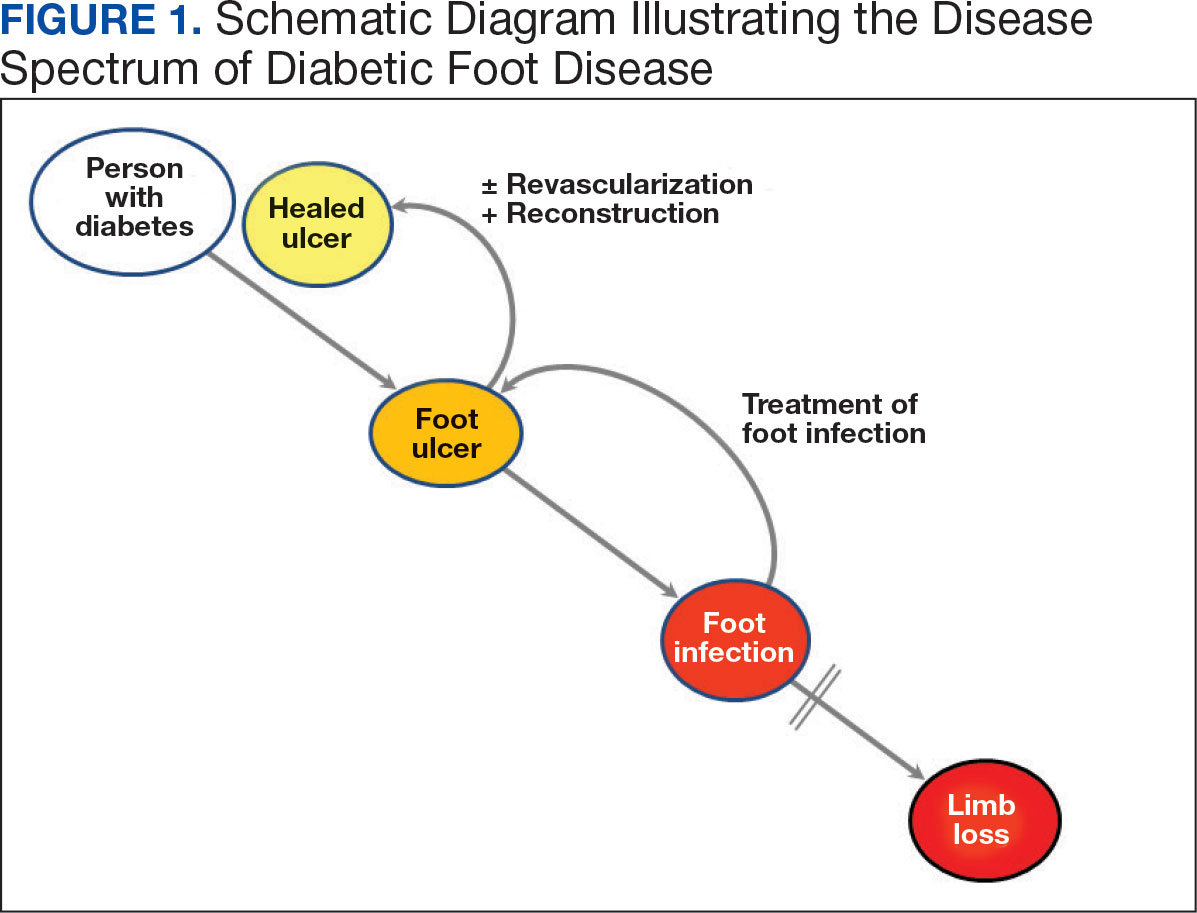

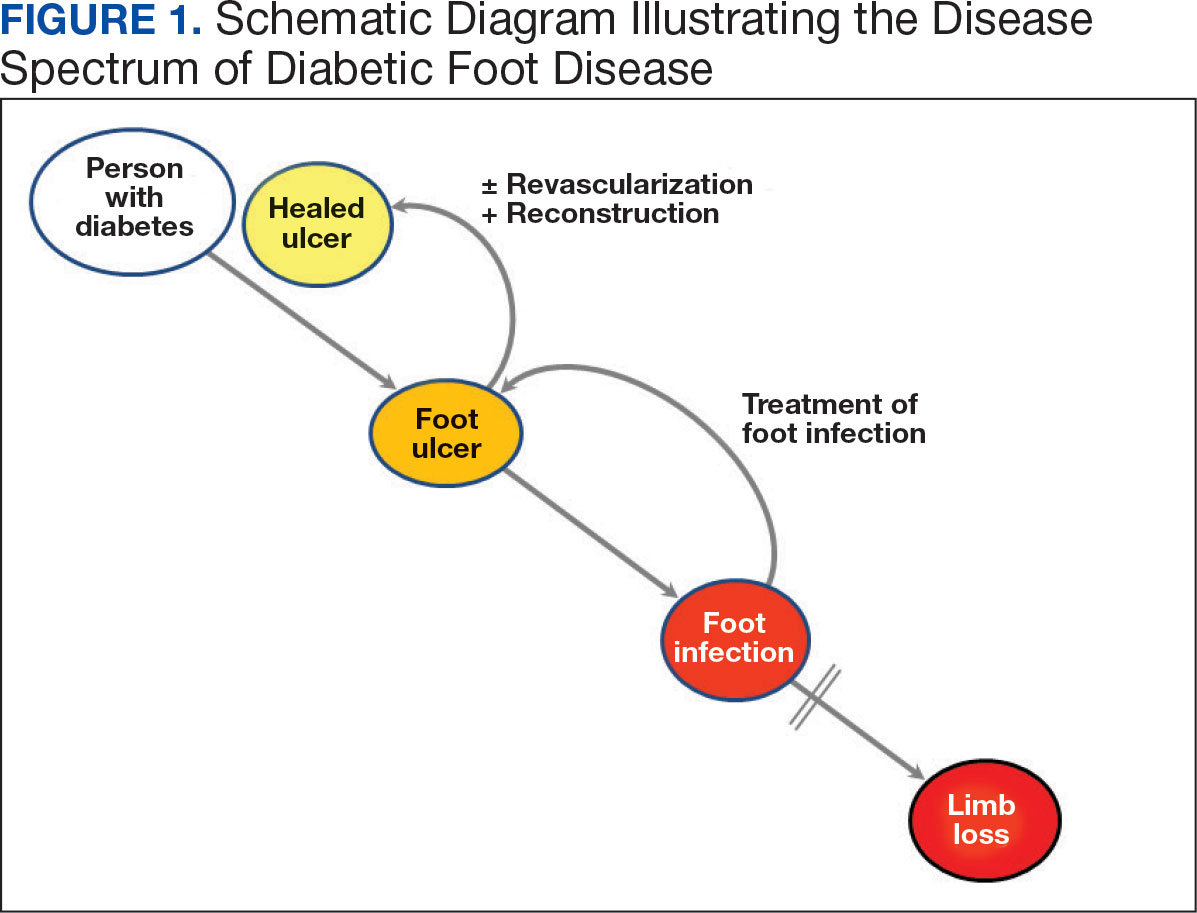

Individuals with diabetes are at risk for developing foot ulcers or full-thickness defects in the epithelium of the foot. These defects can lead to bacterial invasion and foot infection, potentially resulting in leg amputation (Figure 1). Effective treatment to prevent leg amputation, known as limb salvage, requires management across multiple medical specialties including podiatry, vascular surgery, and infectious diseases. The multidisciplinary team approach to limb salvage was introduced in Boston in 1928 and has been the prevailing approach to this cross-specialty medical problem for at least a decade.1,2

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) has established an inpatient limb salvage program—a group of dedicated clinicians working collaboratively to provide evidence-guided management of patients hospitalized with foot ulcers, foot gangrene or any superimposed infection with the goal of avoiding leg amputations. We have seen a significant and durable reduction in the incidence of leg amputations among veterans at MEDVAMC.

This article describes the evolution and outcomes of the MEDVAMC limb salvage program over more than a decade. It includes changes to team structure and workflow, as well as past and present successes and challenges. The eAppendix provides a narrative summary with examples of how our clinical practice and research efforts have informed one another and how these findings are applied to clinical management. This process is part of the larger efforts of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) to create a learning health system in which “internal data and experience are systematically integrated with external evidence, and that knowledge is put into practice.”3

Methods

Data from the VHA Support Service Center were used to obtain monthly major (leg) and minor (toe and partial foot) amputation records at MEDVAMC from October 2000 through May 2023. Yearly totals for the number of persons with diabetes and foot ulcers at MEDVAMC were also obtained from the support service center. Annual patient population sizes and number of persons with foot ulcers were converted to monthly estimates using cubic spline interpolation. Rates were calculated as 12-month rolling averages. Trend lines were created with locally weighted running line smoothing that used a span α of 0.1.

We characterized the patient population using data from cohorts of veterans treated for foot ulcers and foot infections at MEDVAMC. To compare the contemporary veteran population with nonveteran inpatients treated for foot ulcers and foot infections at other hospitals, we created a 2:1 nonveteran to veteran cohort matched by sex and zip code, using publicly available hospital admission data from the Texas Department of Health and State Health Services. Veterans used for this cohort comparison are consistent with the 100 consecutive patients who underwent angiography for limb salvage in 2022.

This research was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (protocol H-34858) and the MEDVAMC Research Committee (IRBNet protocol 15A12. HB). All analyses used deidentified data in the R programming language version 4.2.2 using RStudio version 2022.06.0 Build 421.

Program Description

MEDVAMC is a 350-bed teaching hospital located in central Houston. Its hospital system includes 11 outpatient clinics, ranging from 28 to 126 miles (eAppendix, Supplemental Figure A) from MEDVAMC. MEDVAMC provides vascular, orthopedic, and podiatric surgery services, as well as many other highly specialized services such as liver and heart transplants. The hospital’s risk-adjusted rates of operative morbidity and mortality (observed-to-expected ratios) are significantly lower than expected.

Despite this, the incidence rate of leg amputations at MEDVAMC in early 2011 was nearly 3-times higher than the VHA average. The inpatient management of veterans with infected foot ulcers was fragmented, with the general, orthopedic, and vascular surgery teams separately providing siloed care. Delays in treatment were common. There was much service- and practitioner-level practice heterogeneity. No diagnostic or treatment protocols were used, and standard treatment components were sporadically provided.

Patient Population

Compared to the matched non-VHA patient cohort (Supplemental Table 1), veterans treated at MEDVAMC for limb salvage are older. Nearly half (46%) identify as Black, which is associated with a 2-fold higher riskadjusted rate of leg amputations.4 MEDVAMC patients also have significantly higher rates of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and systolic heart failure. About 22% travel > 40 miles for treatment at MEDVAMC, double that of the matched cohort (10.7%). Additionally, 35% currently smoke and 37% have moderate to severe peripheral artery disease (PAD).5

Program Design

In late 2011, the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team led limb salvage efforts by implementing a single team model, which involved assuming the primary role of managing foot ulcers for all veterans, both infected and uninfected (eAppendix, Supplemental Figure B). Consultations were directed to a dedicated limb salvage pager. The vascular team provided interdisciplinary limb salvage management across the spectrum of disease, including the surgical treatment of infection, assessment for PAD, open surgical operations and endovascular interventions to treat PAD, and foot reconstruction (debridement, minor or partial foot amputations, and skin grafting). This care was complemented by frequent consultation with the infectious disease, vascular medicine, podiatry, and geriatric wound care teams. This approach streamlined the delivery of consistent multidisciplinary care.

This collaborative effort aimed to develop ideal multidisciplinary care plans through research spanning the spectrum of the diabetic foot infection disease process (eAppendix, Supplemental Table 1). Some of the most impactful practices were: (1) a proclivity towards surgical treatment of foot infections, especially osteomyelitis5; (2) improved identification of PAD6,7; (3) early surgical closure of foot wounds following revascularization8,9; and (4) palliative wound care as an alternative to leg amputation in veterans who are not candidates for revascularization and limb salvage.10 Initally, the vascular surgery team held monthly multidisciplinary limb salvage meetings to coordinate patient management, identify ways to streamline care and avoid waste, discuss research findings, and review the 12-month rolling average of the MEDVAMC leg amputation incidence rate.

During the study period, the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team consisted of 2 to 5 board certified vascular or general surgeons, 2 or 3 nurse practitioners, and 3 vascular ultrasound technologists. Associated specialists included 2 podiatrists, 3 geriatricians with wound care certification, as well as additional infectious diseases, vascular medicine, orthopedics, and general surgery specialists.

Program Assessment

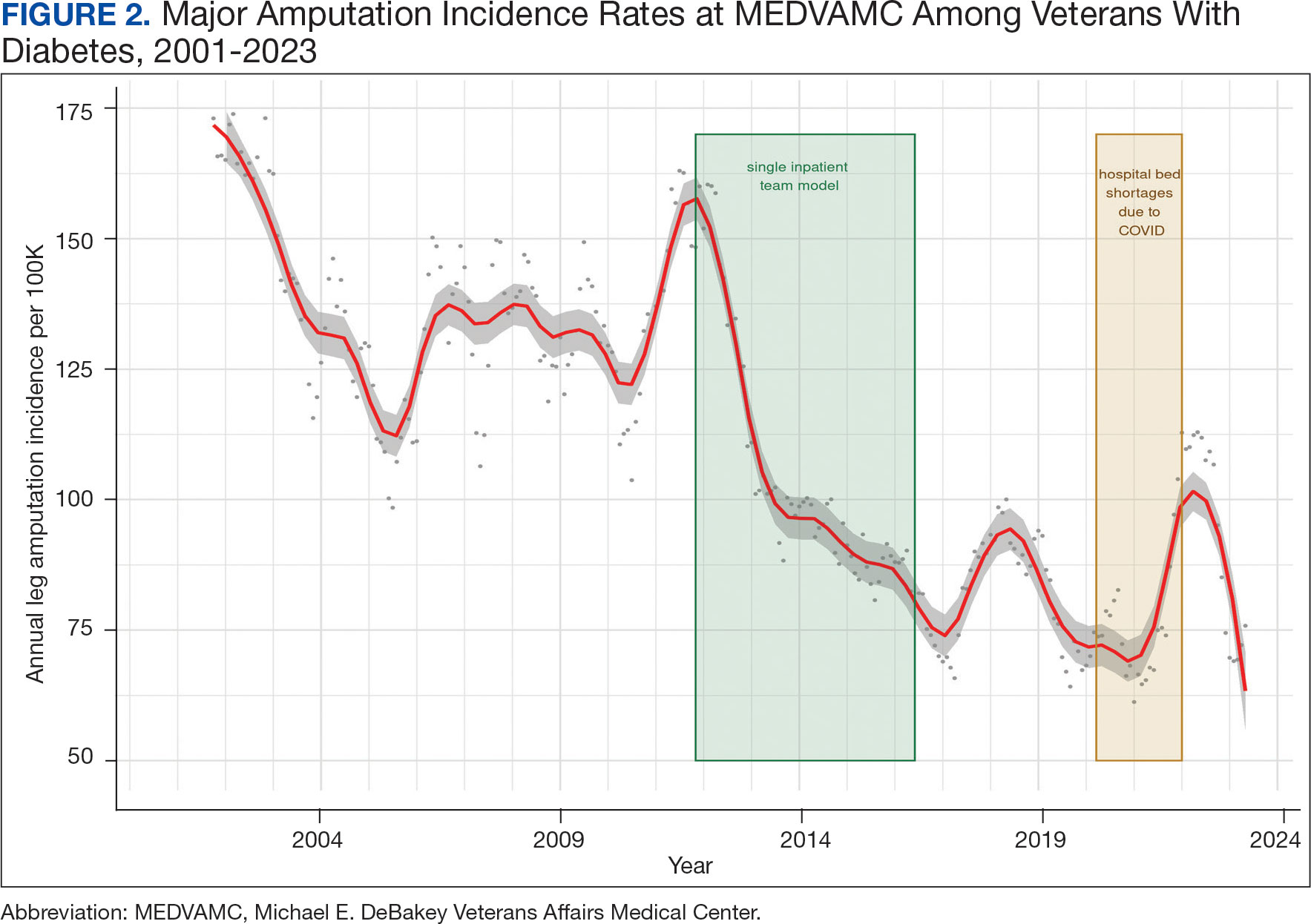

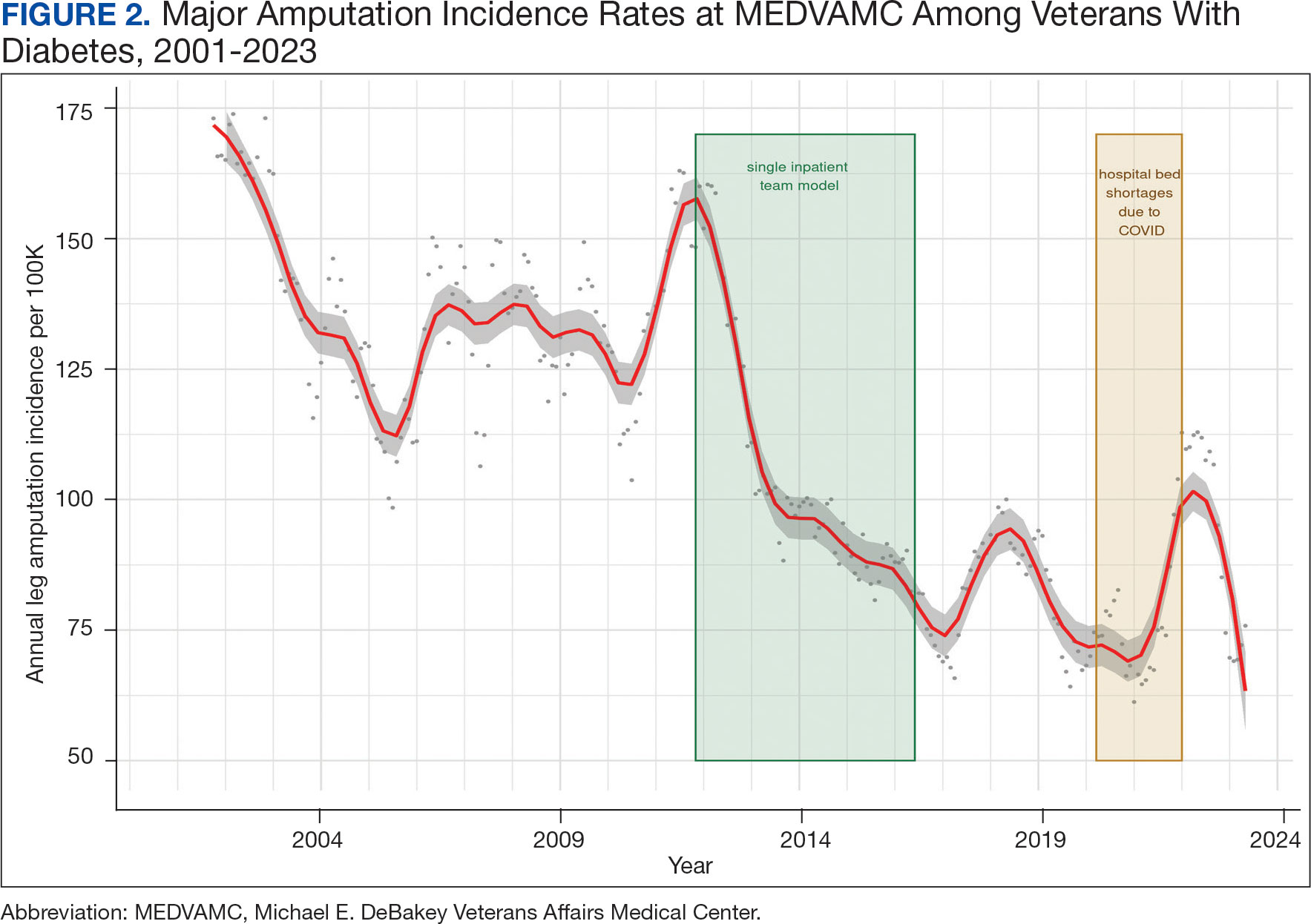

We noted a significant and sustained decrease in the MEDVAMC leg amputation rate after implementing multidisciplinary meetings and a single- team model from early 2012 through 2017 (Figure 2). The amputation incidence rate decreased steadily over the period from a maximum of 160 per 100,000 per year in February 2012 to a nadir of 66 per 100,000 per year in April 2017, an overall 60% decrease. Increases were noted in early 2018 after ceasing the single- team model, and in the summer of 2022, following periods of bed shortages after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tracking this metric allowed clinicians to make course corrections.

The decreased leg amputation rate at MEDVAMC does not seem to be mirroring national or regional trends. During this 10-year period, the VHA annualized amputation rate decreased minimally, from 58 to 54 per 100,000 (eAppendix Supplemental Figure C). Leg amputation incidence at non-VHA hospitals in Texas slightly increased over the same period.11

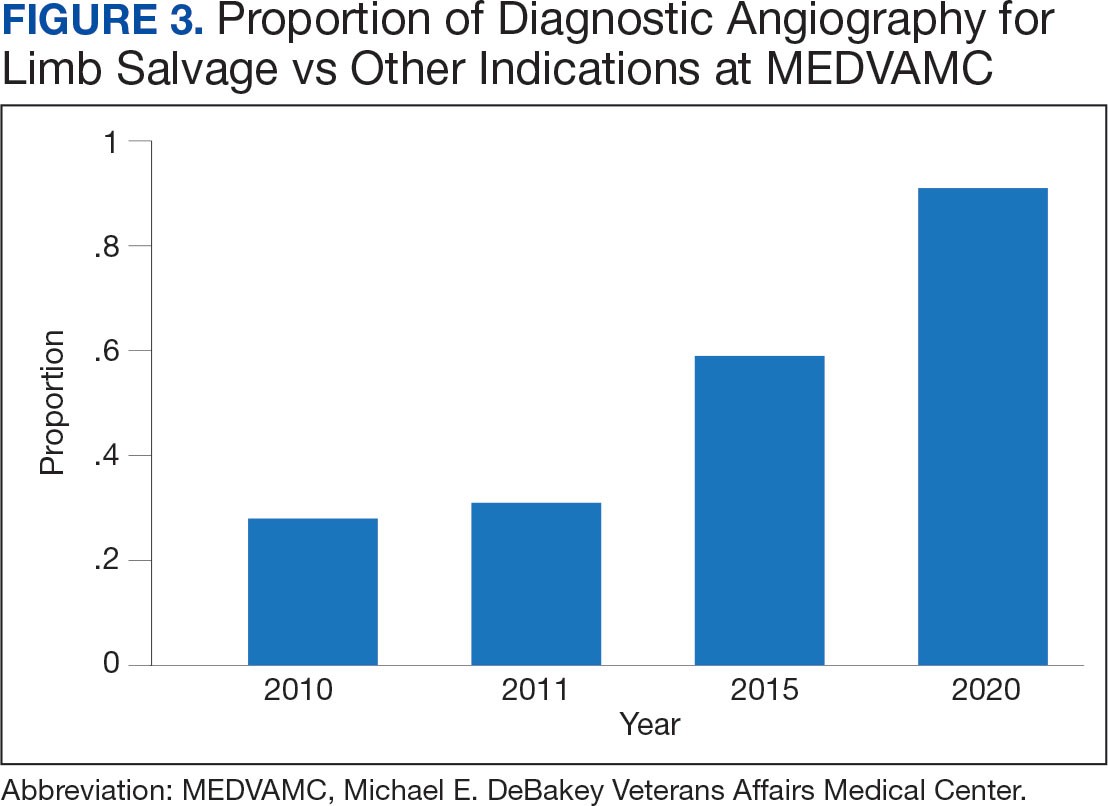

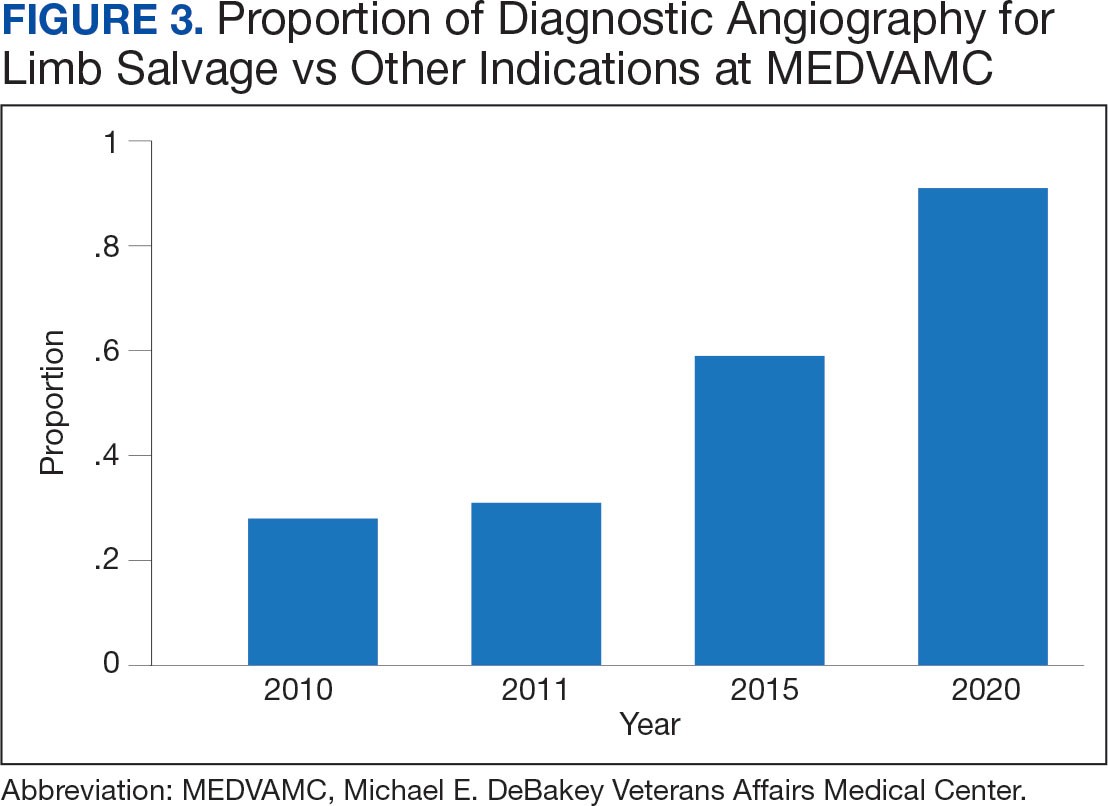

Value was also reflected in other metrics. MEDVAMC improved safety through a bundled strategy that reduced the risk-adjusted rate of surgical wound infections by 95%.12 MEDVAMC prioritized limb salvage when selecting patients for angiography and nearly eliminated using stent-grafts, cryopreserved allogeneic saphenous vein grafts, and expensive surgical and endovascular implants, which were identified as more expensive and less effective than other options (Figure 3).13-15 The MEDVAMC team achieved a > 90% patient trust rating on the Veterans Signals survey in fiscal years 2021 and 2022.

Challenges

A significant increase in the patient-physician ratio occurred 5 years into the program. In 2016, 2 vascular surgeons left MEDVAMC and a planned renovation of 1 of the 2 vascular surgery-assigned hybrid working facilities began even as the number of MEDVAMC patients with diabetes grew 120% (from 89,400 to 107,746 between 2010 and 2016), and the incidence rate of foot ulcers grew 300% (from 392 in 2010 to 1183 in 2016 per 100,000). The net result was a higher clinical workload among the remaining vascular surgeons with less operating room availability.

To stabilize surgeon retention, MEDVAMC reverted from the single team model back to inpatient care being distributed among general surgery, orthopedic surgery, and vascular surgery. After noting an increase in the leg amputation incidence rate, we adjusted the focus from multidisciplinary to interdisciplinary care (ie, majority of limb salvage clinical care can be provided by practitioners of any involved specialties). We worked to establish a local, written, interdisciplinary consensus on evaluating and managing veterans with nonhealing foot ulcers to mitigate the loss of a consolidated inpatient approach. Despite frequent staff turnover, ≥ 1 physician or surgeon from the core specialties of vascular surgery, podiatry, and infectious diseases remained throughout the study period.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a shortage of hospital beds. This was followed by more bed shortages due to decreased nursing staff. Our health care system also had a period of restricted outpatient encounters early in the pandemic. During this time, we noted a delayed presentation of veterans with advanced infections and another increase in leg amputation incidence rate.

Like many health systems, MEDVAMC pivoted to telephone- and video-based outpatient encounters. Our team also used publicly available Texas hospitalization data to identify zip codes with particularly high leg amputation incidence rates, and > 3500 educational mailings to veterans categorized as moderate and high risk for leg amputation in these zip codes. These mailings provided information on recognizing foot ulcers and infections, emphasized timely evaluation, and named the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team as a point-of-contact. More recently, we have seen a further decrease in the MEDVAMC incidences of leg amputation to its lowest rate in > 20 years.

Discussion

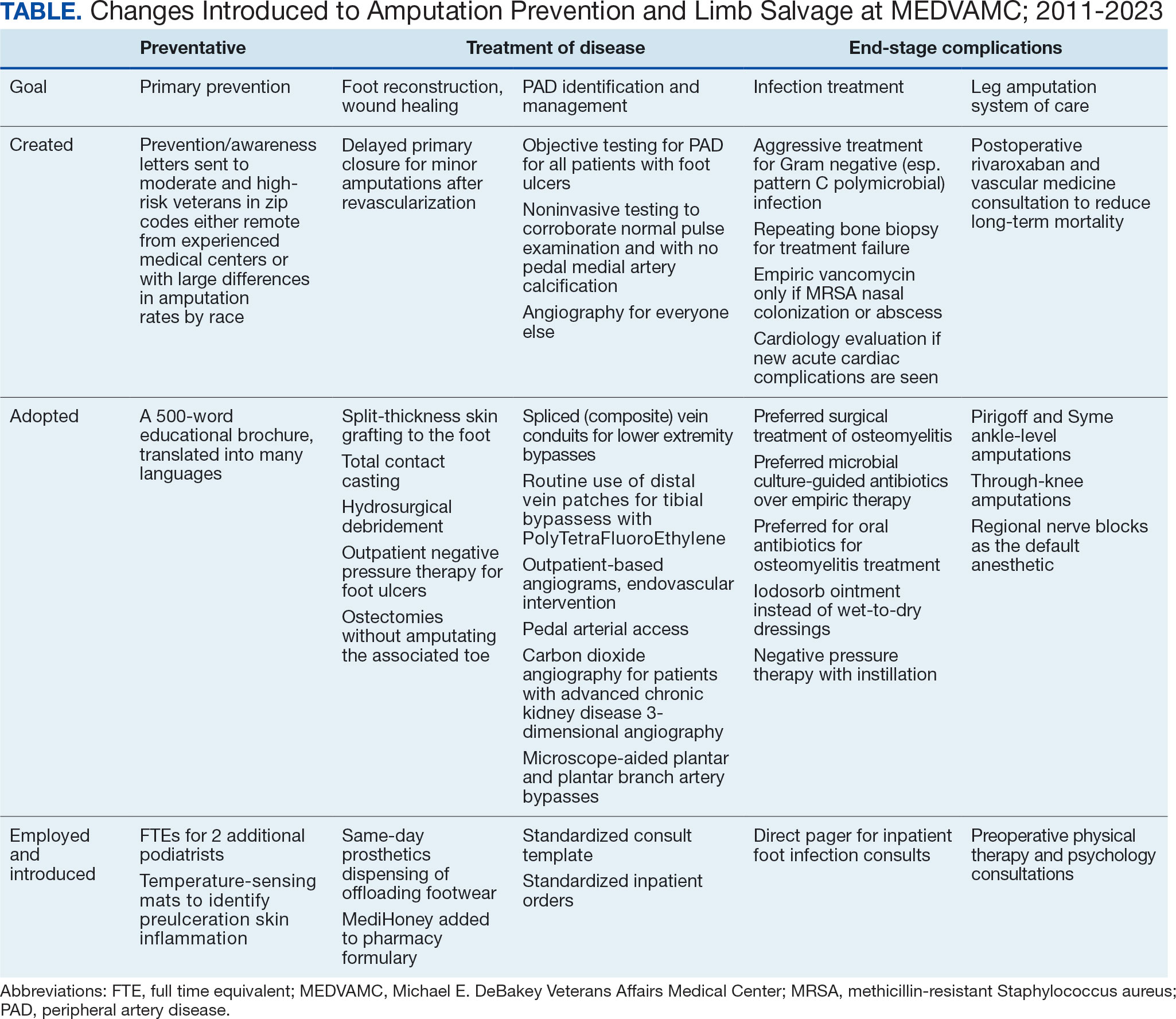

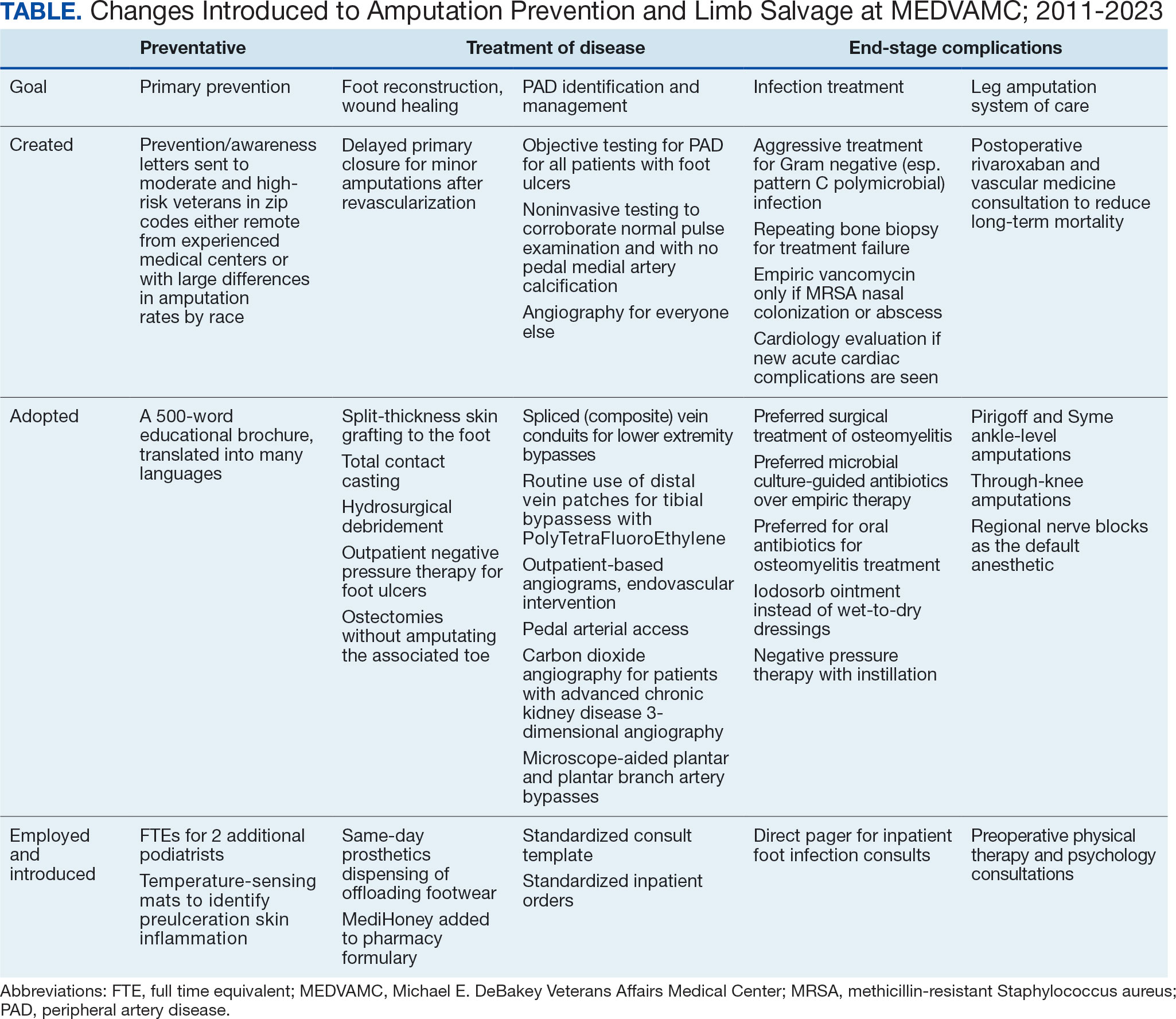

A learning organization that directs its research based on clinical observations and informs its clinical care with research findings can produce palpable improvements in outcomes. Understanding the disease process and trying to better understand management across the entire range of this disease process has allowed our team to make consistent and systematic changes in care (Table). Consolidating inpatient care in a single team model seems to have been effective in reducing amputation rates among veterans with diabetes. The role the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team served for limb salvage patients may have been particularly beneficial because of the large impact untreated or unidentified PAD can have and because of the high prevalence of PAD among the limb salvage population seen at MEDVAMC. To be sustainable, though, a single-team model needs resources. A multiteam model can also be effective if the degree of multidisciplinary involvement for any given veteran is appropriate to the individual's clinical needs, teams are engaged and willing to contribute in a defined role within their specialty, and lines of communication remain open.

The primary challenge at MEDVAMC has been, and will continue to be, the retention of physicians and surgeons. MEDVAMC has excellent leadership and a collegial working environment, but better access to operating rooms for elective and time-sensitive operations, additional clinical staff support, and higher salary at non-VA positions have been the basis for many of physicians— especially surgeons—leaving MEDVAMC. Despite high staff turnover and a constant flow of resident and fellow trainees, MEDVAMC has been able to keep the clinical approach relatively consistent due to the use of written protocols and continuity of care as ≥ 1 physician or surgeon from each of the 4 main teams remained engaged with limb salvage throughout the entire period.

Going forward, we will work to ensure that all requirements of the 2022 Prevention of Amputation in Veterans Everywhere directive are incorporated into care.8 We plan to standardize MEDVAMC management algorithms further, both to streamline care and reduce the opportunity for disparities in treatment. More prophylactic podiatric procedures, surgical forms of offloading, and a shared multidisciplinary clinic space may also further help patients.

Conclusions

The introduction of multidisciplinary limb salvage at MEDVAMC has led to significant and sustained reductions in leg amputation incidence. These reductions do not seem dependent upon a specific team structure for inpatient care. To improve patient outcomes, efforts should focus on making improvements across the entire disease spectrum. For limb salvage, this includes primary prevention of foot ulcers, the treatment of foot infections, identification and management of PAD, surgical reconstruction/optimal wound healing, and care for patients who undergo leg amputation.

- Sanders LJ, Robbins JM, Edmonds ME. History of the team approach to amputation prevention: pioneers and milestones. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100(5):317- 334. doi:10.7547/1000317

- Sumpio BE, Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Andros G. The role of interdisciplinary team approach in the management of the diabetic foot: a joint statement from the society for vascular surgery and the American podiatric medical association. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100(4):309-311. doi:10.7547/1000309

- About learning health systems. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published March 2019. Updated May 2019. Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html

- Barshes NR, Minc SD. Healthcare disparities in vascular surgery: a critical review. J Vasc Surg. 2021;74(2S):6S-14S.

- Barshes NR, Mindru C, Ashong C, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Trautner BW. Treatment failure and leg amputation among patients with foot osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15(4):303-312. doi:10.1177/1534734616661058

- Barshes NR, Flores E, Belkin M, Kougias P, Armstrong DG, Mills JL Sr. The accuracy and cost-effectiveness of strategies used to identify peripheral artery disease among patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(6):1682-1690.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.056 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2021.03.055

- Choi JC, Miranda J, Greenleaf E, et al. Lower-extremity pressure, staging, and grading thresholds to identify chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Vasc Med. 2023;28(1):45-53. doi:10.1177/1358863X221147945

- Barshes NR, Chambers JD, Cohen J, Belkin M; Model To Optimize Healthcare Value in Ischemic Extremities 1 (MOVIE) Study Collaborators. Cost-effectiveness in the contemporary management of critical limb ischemia with tissue loss. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):1015-24.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.069

- Barshes NR, Bechara CF, Pisimisis G, Kougias P. Preliminary experiences with early primary closure of foot wounds after lower extremity revascularization. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(1):48-52. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.06.012

- Barshes NR, Gold B, Garcia A, Bechara CF, Pisimisis G, Kougias P. Minor amputation and palliative wound care as a strategy to avoid major amputation in patients with foot infections and severe peripheral arterial disease. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2014;13(3):211-219. doi:10.1177/1534734614543663

- Garcia M, Hernandez B, Ellington TG, et al. A lack of decline in major nontraumatic amputations in Texas: contemporary trends, risk factor associations, and impact of revascularization. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(6):1061-1066. doi:10.2337/dc19-0078

- Zamani N, Sharath SE, Vo E, Awad SS, Kougias P, Barshes NR. A multi-component strategy to decrease wound complications after open infra-inguinal re-vascularization. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2018;19(1):87-94. doi:10.1089/sur.2017.193

- Barshes NR, Ozaki CK, Kougias P, Belkin M. A costeffectiveness analysis of infrainguinal bypass in the absence of great saphenous vein conduit. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(6):1466-1470. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.115

- Zamani N, Sharath S, Browder R, et al. PC158 longterm outcomes after endovascular stent placement for symptomatic, long-segment superficial femoral artery lesions. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(6):182S-183S. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2017.03.344

- Zamani N, Sharath SE, Browder RC, et al. Outcomes after endovascular stent placement for long-segment superficial femoral artery lesions. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;71:298-307. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2020.08.124

Individuals with diabetes are at risk for developing foot ulcers or full-thickness defects in the epithelium of the foot. These defects can lead to bacterial invasion and foot infection, potentially resulting in leg amputation (Figure 1). Effective treatment to prevent leg amputation, known as limb salvage, requires management across multiple medical specialties including podiatry, vascular surgery, and infectious diseases. The multidisciplinary team approach to limb salvage was introduced in Boston in 1928 and has been the prevailing approach to this cross-specialty medical problem for at least a decade.1,2

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) has established an inpatient limb salvage program—a group of dedicated clinicians working collaboratively to provide evidence-guided management of patients hospitalized with foot ulcers, foot gangrene or any superimposed infection with the goal of avoiding leg amputations. We have seen a significant and durable reduction in the incidence of leg amputations among veterans at MEDVAMC.

This article describes the evolution and outcomes of the MEDVAMC limb salvage program over more than a decade. It includes changes to team structure and workflow, as well as past and present successes and challenges. The eAppendix provides a narrative summary with examples of how our clinical practice and research efforts have informed one another and how these findings are applied to clinical management. This process is part of the larger efforts of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) to create a learning health system in which “internal data and experience are systematically integrated with external evidence, and that knowledge is put into practice.”3

Methods

Data from the VHA Support Service Center were used to obtain monthly major (leg) and minor (toe and partial foot) amputation records at MEDVAMC from October 2000 through May 2023. Yearly totals for the number of persons with diabetes and foot ulcers at MEDVAMC were also obtained from the support service center. Annual patient population sizes and number of persons with foot ulcers were converted to monthly estimates using cubic spline interpolation. Rates were calculated as 12-month rolling averages. Trend lines were created with locally weighted running line smoothing that used a span α of 0.1.

We characterized the patient population using data from cohorts of veterans treated for foot ulcers and foot infections at MEDVAMC. To compare the contemporary veteran population with nonveteran inpatients treated for foot ulcers and foot infections at other hospitals, we created a 2:1 nonveteran to veteran cohort matched by sex and zip code, using publicly available hospital admission data from the Texas Department of Health and State Health Services. Veterans used for this cohort comparison are consistent with the 100 consecutive patients who underwent angiography for limb salvage in 2022.

This research was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (protocol H-34858) and the MEDVAMC Research Committee (IRBNet protocol 15A12. HB). All analyses used deidentified data in the R programming language version 4.2.2 using RStudio version 2022.06.0 Build 421.

Program Description

MEDVAMC is a 350-bed teaching hospital located in central Houston. Its hospital system includes 11 outpatient clinics, ranging from 28 to 126 miles (eAppendix, Supplemental Figure A) from MEDVAMC. MEDVAMC provides vascular, orthopedic, and podiatric surgery services, as well as many other highly specialized services such as liver and heart transplants. The hospital’s risk-adjusted rates of operative morbidity and mortality (observed-to-expected ratios) are significantly lower than expected.

Despite this, the incidence rate of leg amputations at MEDVAMC in early 2011 was nearly 3-times higher than the VHA average. The inpatient management of veterans with infected foot ulcers was fragmented, with the general, orthopedic, and vascular surgery teams separately providing siloed care. Delays in treatment were common. There was much service- and practitioner-level practice heterogeneity. No diagnostic or treatment protocols were used, and standard treatment components were sporadically provided.

Patient Population

Compared to the matched non-VHA patient cohort (Supplemental Table 1), veterans treated at MEDVAMC for limb salvage are older. Nearly half (46%) identify as Black, which is associated with a 2-fold higher riskadjusted rate of leg amputations.4 MEDVAMC patients also have significantly higher rates of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and systolic heart failure. About 22% travel > 40 miles for treatment at MEDVAMC, double that of the matched cohort (10.7%). Additionally, 35% currently smoke and 37% have moderate to severe peripheral artery disease (PAD).5

Program Design

In late 2011, the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team led limb salvage efforts by implementing a single team model, which involved assuming the primary role of managing foot ulcers for all veterans, both infected and uninfected (eAppendix, Supplemental Figure B). Consultations were directed to a dedicated limb salvage pager. The vascular team provided interdisciplinary limb salvage management across the spectrum of disease, including the surgical treatment of infection, assessment for PAD, open surgical operations and endovascular interventions to treat PAD, and foot reconstruction (debridement, minor or partial foot amputations, and skin grafting). This care was complemented by frequent consultation with the infectious disease, vascular medicine, podiatry, and geriatric wound care teams. This approach streamlined the delivery of consistent multidisciplinary care.

This collaborative effort aimed to develop ideal multidisciplinary care plans through research spanning the spectrum of the diabetic foot infection disease process (eAppendix, Supplemental Table 1). Some of the most impactful practices were: (1) a proclivity towards surgical treatment of foot infections, especially osteomyelitis5; (2) improved identification of PAD6,7; (3) early surgical closure of foot wounds following revascularization8,9; and (4) palliative wound care as an alternative to leg amputation in veterans who are not candidates for revascularization and limb salvage.10 Initally, the vascular surgery team held monthly multidisciplinary limb salvage meetings to coordinate patient management, identify ways to streamline care and avoid waste, discuss research findings, and review the 12-month rolling average of the MEDVAMC leg amputation incidence rate.

During the study period, the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team consisted of 2 to 5 board certified vascular or general surgeons, 2 or 3 nurse practitioners, and 3 vascular ultrasound technologists. Associated specialists included 2 podiatrists, 3 geriatricians with wound care certification, as well as additional infectious diseases, vascular medicine, orthopedics, and general surgery specialists.

Program Assessment

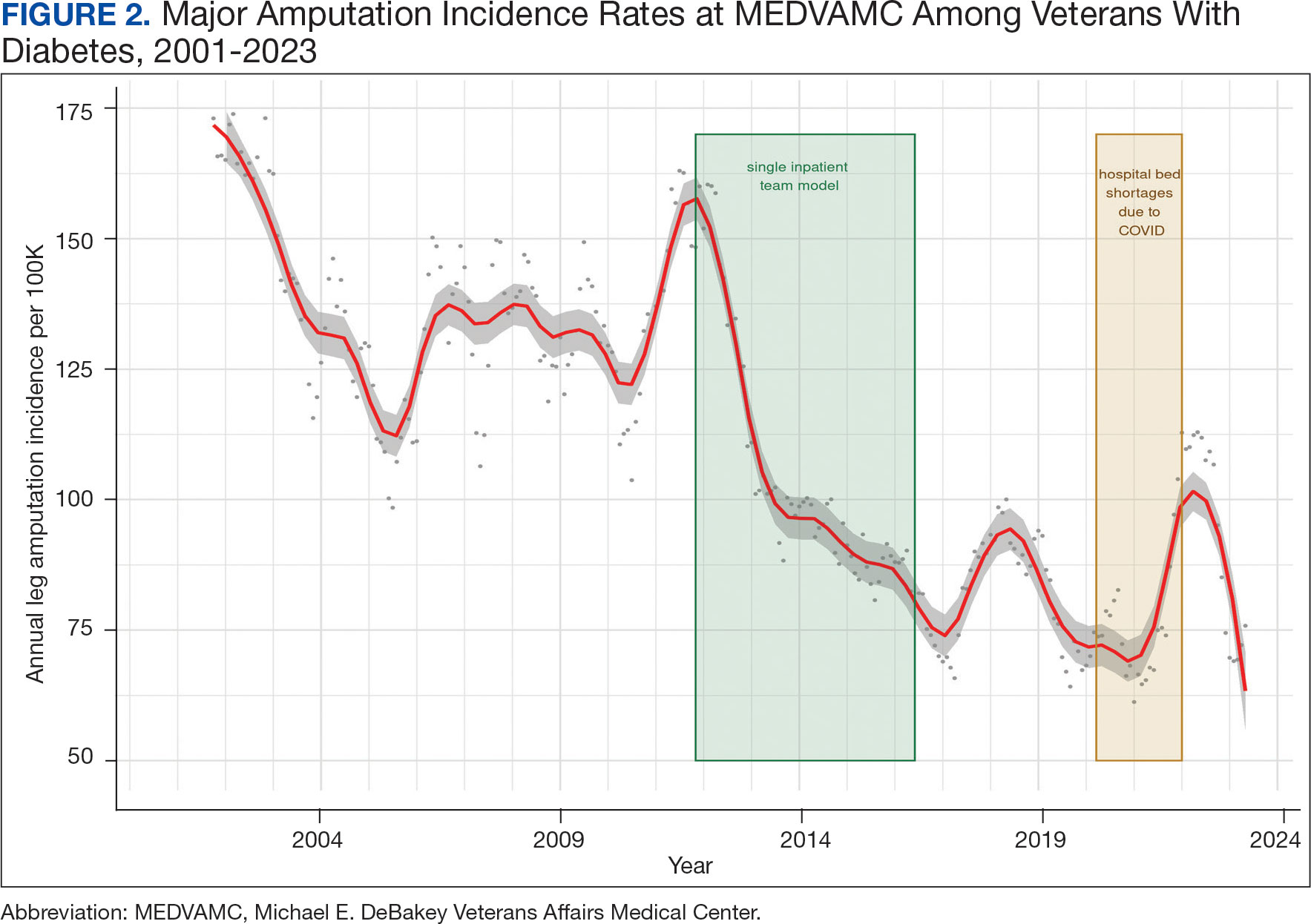

We noted a significant and sustained decrease in the MEDVAMC leg amputation rate after implementing multidisciplinary meetings and a single- team model from early 2012 through 2017 (Figure 2). The amputation incidence rate decreased steadily over the period from a maximum of 160 per 100,000 per year in February 2012 to a nadir of 66 per 100,000 per year in April 2017, an overall 60% decrease. Increases were noted in early 2018 after ceasing the single- team model, and in the summer of 2022, following periods of bed shortages after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tracking this metric allowed clinicians to make course corrections.

The decreased leg amputation rate at MEDVAMC does not seem to be mirroring national or regional trends. During this 10-year period, the VHA annualized amputation rate decreased minimally, from 58 to 54 per 100,000 (eAppendix Supplemental Figure C). Leg amputation incidence at non-VHA hospitals in Texas slightly increased over the same period.11

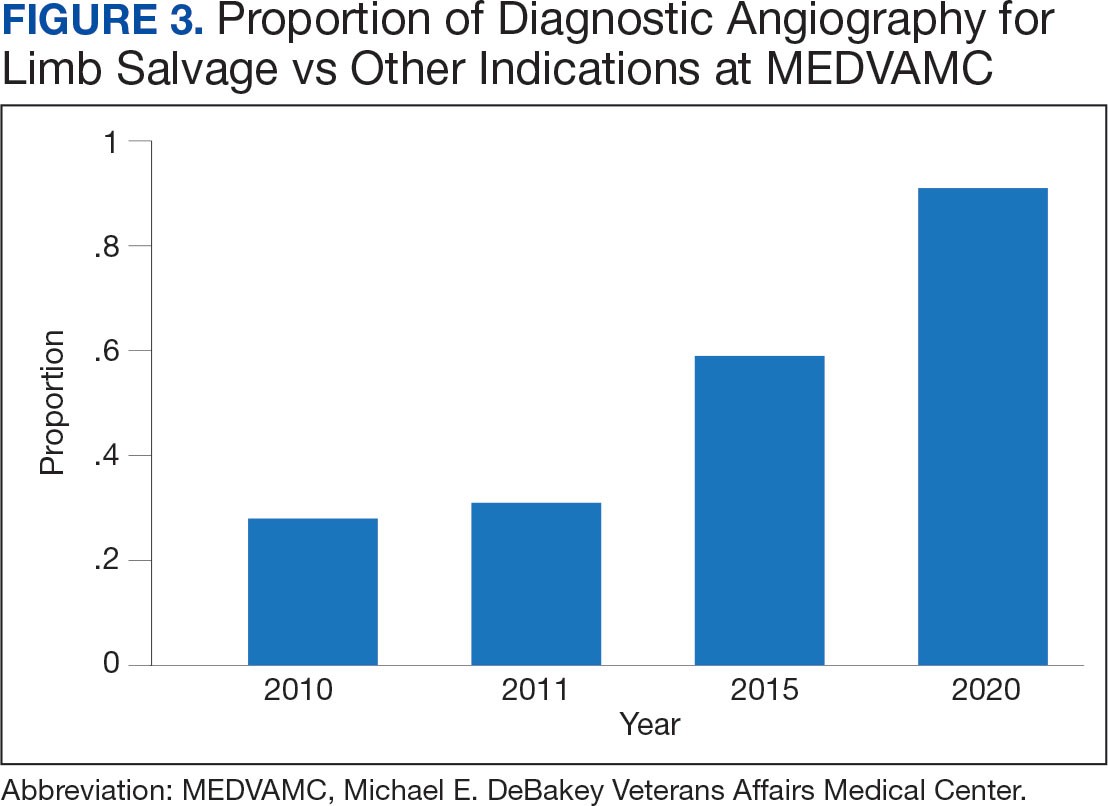

Value was also reflected in other metrics. MEDVAMC improved safety through a bundled strategy that reduced the risk-adjusted rate of surgical wound infections by 95%.12 MEDVAMC prioritized limb salvage when selecting patients for angiography and nearly eliminated using stent-grafts, cryopreserved allogeneic saphenous vein grafts, and expensive surgical and endovascular implants, which were identified as more expensive and less effective than other options (Figure 3).13-15 The MEDVAMC team achieved a > 90% patient trust rating on the Veterans Signals survey in fiscal years 2021 and 2022.

Challenges

A significant increase in the patient-physician ratio occurred 5 years into the program. In 2016, 2 vascular surgeons left MEDVAMC and a planned renovation of 1 of the 2 vascular surgery-assigned hybrid working facilities began even as the number of MEDVAMC patients with diabetes grew 120% (from 89,400 to 107,746 between 2010 and 2016), and the incidence rate of foot ulcers grew 300% (from 392 in 2010 to 1183 in 2016 per 100,000). The net result was a higher clinical workload among the remaining vascular surgeons with less operating room availability.

To stabilize surgeon retention, MEDVAMC reverted from the single team model back to inpatient care being distributed among general surgery, orthopedic surgery, and vascular surgery. After noting an increase in the leg amputation incidence rate, we adjusted the focus from multidisciplinary to interdisciplinary care (ie, majority of limb salvage clinical care can be provided by practitioners of any involved specialties). We worked to establish a local, written, interdisciplinary consensus on evaluating and managing veterans with nonhealing foot ulcers to mitigate the loss of a consolidated inpatient approach. Despite frequent staff turnover, ≥ 1 physician or surgeon from the core specialties of vascular surgery, podiatry, and infectious diseases remained throughout the study period.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a shortage of hospital beds. This was followed by more bed shortages due to decreased nursing staff. Our health care system also had a period of restricted outpatient encounters early in the pandemic. During this time, we noted a delayed presentation of veterans with advanced infections and another increase in leg amputation incidence rate.

Like many health systems, MEDVAMC pivoted to telephone- and video-based outpatient encounters. Our team also used publicly available Texas hospitalization data to identify zip codes with particularly high leg amputation incidence rates, and > 3500 educational mailings to veterans categorized as moderate and high risk for leg amputation in these zip codes. These mailings provided information on recognizing foot ulcers and infections, emphasized timely evaluation, and named the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team as a point-of-contact. More recently, we have seen a further decrease in the MEDVAMC incidences of leg amputation to its lowest rate in > 20 years.

Discussion

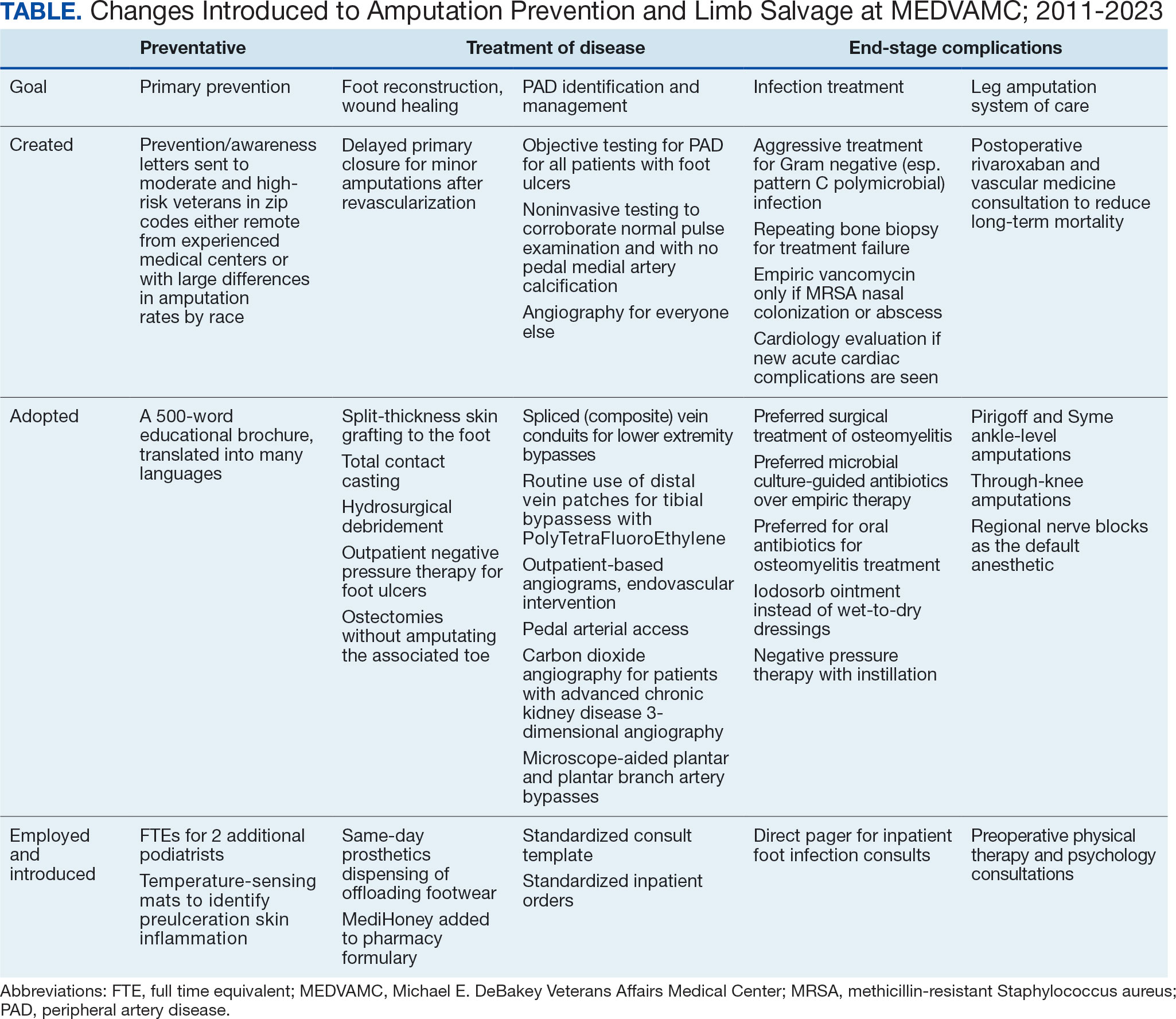

A learning organization that directs its research based on clinical observations and informs its clinical care with research findings can produce palpable improvements in outcomes. Understanding the disease process and trying to better understand management across the entire range of this disease process has allowed our team to make consistent and systematic changes in care (Table). Consolidating inpatient care in a single team model seems to have been effective in reducing amputation rates among veterans with diabetes. The role the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team served for limb salvage patients may have been particularly beneficial because of the large impact untreated or unidentified PAD can have and because of the high prevalence of PAD among the limb salvage population seen at MEDVAMC. To be sustainable, though, a single-team model needs resources. A multiteam model can also be effective if the degree of multidisciplinary involvement for any given veteran is appropriate to the individual's clinical needs, teams are engaged and willing to contribute in a defined role within their specialty, and lines of communication remain open.

The primary challenge at MEDVAMC has been, and will continue to be, the retention of physicians and surgeons. MEDVAMC has excellent leadership and a collegial working environment, but better access to operating rooms for elective and time-sensitive operations, additional clinical staff support, and higher salary at non-VA positions have been the basis for many of physicians— especially surgeons—leaving MEDVAMC. Despite high staff turnover and a constant flow of resident and fellow trainees, MEDVAMC has been able to keep the clinical approach relatively consistent due to the use of written protocols and continuity of care as ≥ 1 physician or surgeon from each of the 4 main teams remained engaged with limb salvage throughout the entire period.

Going forward, we will work to ensure that all requirements of the 2022 Prevention of Amputation in Veterans Everywhere directive are incorporated into care.8 We plan to standardize MEDVAMC management algorithms further, both to streamline care and reduce the opportunity for disparities in treatment. More prophylactic podiatric procedures, surgical forms of offloading, and a shared multidisciplinary clinic space may also further help patients.

Conclusions

The introduction of multidisciplinary limb salvage at MEDVAMC has led to significant and sustained reductions in leg amputation incidence. These reductions do not seem dependent upon a specific team structure for inpatient care. To improve patient outcomes, efforts should focus on making improvements across the entire disease spectrum. For limb salvage, this includes primary prevention of foot ulcers, the treatment of foot infections, identification and management of PAD, surgical reconstruction/optimal wound healing, and care for patients who undergo leg amputation.

Individuals with diabetes are at risk for developing foot ulcers or full-thickness defects in the epithelium of the foot. These defects can lead to bacterial invasion and foot infection, potentially resulting in leg amputation (Figure 1). Effective treatment to prevent leg amputation, known as limb salvage, requires management across multiple medical specialties including podiatry, vascular surgery, and infectious diseases. The multidisciplinary team approach to limb salvage was introduced in Boston in 1928 and has been the prevailing approach to this cross-specialty medical problem for at least a decade.1,2

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) has established an inpatient limb salvage program—a group of dedicated clinicians working collaboratively to provide evidence-guided management of patients hospitalized with foot ulcers, foot gangrene or any superimposed infection with the goal of avoiding leg amputations. We have seen a significant and durable reduction in the incidence of leg amputations among veterans at MEDVAMC.

This article describes the evolution and outcomes of the MEDVAMC limb salvage program over more than a decade. It includes changes to team structure and workflow, as well as past and present successes and challenges. The eAppendix provides a narrative summary with examples of how our clinical practice and research efforts have informed one another and how these findings are applied to clinical management. This process is part of the larger efforts of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) to create a learning health system in which “internal data and experience are systematically integrated with external evidence, and that knowledge is put into practice.”3

Methods

Data from the VHA Support Service Center were used to obtain monthly major (leg) and minor (toe and partial foot) amputation records at MEDVAMC from October 2000 through May 2023. Yearly totals for the number of persons with diabetes and foot ulcers at MEDVAMC were also obtained from the support service center. Annual patient population sizes and number of persons with foot ulcers were converted to monthly estimates using cubic spline interpolation. Rates were calculated as 12-month rolling averages. Trend lines were created with locally weighted running line smoothing that used a span α of 0.1.

We characterized the patient population using data from cohorts of veterans treated for foot ulcers and foot infections at MEDVAMC. To compare the contemporary veteran population with nonveteran inpatients treated for foot ulcers and foot infections at other hospitals, we created a 2:1 nonveteran to veteran cohort matched by sex and zip code, using publicly available hospital admission data from the Texas Department of Health and State Health Services. Veterans used for this cohort comparison are consistent with the 100 consecutive patients who underwent angiography for limb salvage in 2022.

This research was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (protocol H-34858) and the MEDVAMC Research Committee (IRBNet protocol 15A12. HB). All analyses used deidentified data in the R programming language version 4.2.2 using RStudio version 2022.06.0 Build 421.

Program Description

MEDVAMC is a 350-bed teaching hospital located in central Houston. Its hospital system includes 11 outpatient clinics, ranging from 28 to 126 miles (eAppendix, Supplemental Figure A) from MEDVAMC. MEDVAMC provides vascular, orthopedic, and podiatric surgery services, as well as many other highly specialized services such as liver and heart transplants. The hospital’s risk-adjusted rates of operative morbidity and mortality (observed-to-expected ratios) are significantly lower than expected.

Despite this, the incidence rate of leg amputations at MEDVAMC in early 2011 was nearly 3-times higher than the VHA average. The inpatient management of veterans with infected foot ulcers was fragmented, with the general, orthopedic, and vascular surgery teams separately providing siloed care. Delays in treatment were common. There was much service- and practitioner-level practice heterogeneity. No diagnostic or treatment protocols were used, and standard treatment components were sporadically provided.

Patient Population

Compared to the matched non-VHA patient cohort (Supplemental Table 1), veterans treated at MEDVAMC for limb salvage are older. Nearly half (46%) identify as Black, which is associated with a 2-fold higher riskadjusted rate of leg amputations.4 MEDVAMC patients also have significantly higher rates of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and systolic heart failure. About 22% travel > 40 miles for treatment at MEDVAMC, double that of the matched cohort (10.7%). Additionally, 35% currently smoke and 37% have moderate to severe peripheral artery disease (PAD).5

Program Design

In late 2011, the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team led limb salvage efforts by implementing a single team model, which involved assuming the primary role of managing foot ulcers for all veterans, both infected and uninfected (eAppendix, Supplemental Figure B). Consultations were directed to a dedicated limb salvage pager. The vascular team provided interdisciplinary limb salvage management across the spectrum of disease, including the surgical treatment of infection, assessment for PAD, open surgical operations and endovascular interventions to treat PAD, and foot reconstruction (debridement, minor or partial foot amputations, and skin grafting). This care was complemented by frequent consultation with the infectious disease, vascular medicine, podiatry, and geriatric wound care teams. This approach streamlined the delivery of consistent multidisciplinary care.

This collaborative effort aimed to develop ideal multidisciplinary care plans through research spanning the spectrum of the diabetic foot infection disease process (eAppendix, Supplemental Table 1). Some of the most impactful practices were: (1) a proclivity towards surgical treatment of foot infections, especially osteomyelitis5; (2) improved identification of PAD6,7; (3) early surgical closure of foot wounds following revascularization8,9; and (4) palliative wound care as an alternative to leg amputation in veterans who are not candidates for revascularization and limb salvage.10 Initally, the vascular surgery team held monthly multidisciplinary limb salvage meetings to coordinate patient management, identify ways to streamline care and avoid waste, discuss research findings, and review the 12-month rolling average of the MEDVAMC leg amputation incidence rate.

During the study period, the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team consisted of 2 to 5 board certified vascular or general surgeons, 2 or 3 nurse practitioners, and 3 vascular ultrasound technologists. Associated specialists included 2 podiatrists, 3 geriatricians with wound care certification, as well as additional infectious diseases, vascular medicine, orthopedics, and general surgery specialists.

Program Assessment

We noted a significant and sustained decrease in the MEDVAMC leg amputation rate after implementing multidisciplinary meetings and a single- team model from early 2012 through 2017 (Figure 2). The amputation incidence rate decreased steadily over the period from a maximum of 160 per 100,000 per year in February 2012 to a nadir of 66 per 100,000 per year in April 2017, an overall 60% decrease. Increases were noted in early 2018 after ceasing the single- team model, and in the summer of 2022, following periods of bed shortages after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tracking this metric allowed clinicians to make course corrections.

The decreased leg amputation rate at MEDVAMC does not seem to be mirroring national or regional trends. During this 10-year period, the VHA annualized amputation rate decreased minimally, from 58 to 54 per 100,000 (eAppendix Supplemental Figure C). Leg amputation incidence at non-VHA hospitals in Texas slightly increased over the same period.11

Value was also reflected in other metrics. MEDVAMC improved safety through a bundled strategy that reduced the risk-adjusted rate of surgical wound infections by 95%.12 MEDVAMC prioritized limb salvage when selecting patients for angiography and nearly eliminated using stent-grafts, cryopreserved allogeneic saphenous vein grafts, and expensive surgical and endovascular implants, which were identified as more expensive and less effective than other options (Figure 3).13-15 The MEDVAMC team achieved a > 90% patient trust rating on the Veterans Signals survey in fiscal years 2021 and 2022.

Challenges

A significant increase in the patient-physician ratio occurred 5 years into the program. In 2016, 2 vascular surgeons left MEDVAMC and a planned renovation of 1 of the 2 vascular surgery-assigned hybrid working facilities began even as the number of MEDVAMC patients with diabetes grew 120% (from 89,400 to 107,746 between 2010 and 2016), and the incidence rate of foot ulcers grew 300% (from 392 in 2010 to 1183 in 2016 per 100,000). The net result was a higher clinical workload among the remaining vascular surgeons with less operating room availability.

To stabilize surgeon retention, MEDVAMC reverted from the single team model back to inpatient care being distributed among general surgery, orthopedic surgery, and vascular surgery. After noting an increase in the leg amputation incidence rate, we adjusted the focus from multidisciplinary to interdisciplinary care (ie, majority of limb salvage clinical care can be provided by practitioners of any involved specialties). We worked to establish a local, written, interdisciplinary consensus on evaluating and managing veterans with nonhealing foot ulcers to mitigate the loss of a consolidated inpatient approach. Despite frequent staff turnover, ≥ 1 physician or surgeon from the core specialties of vascular surgery, podiatry, and infectious diseases remained throughout the study period.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a shortage of hospital beds. This was followed by more bed shortages due to decreased nursing staff. Our health care system also had a period of restricted outpatient encounters early in the pandemic. During this time, we noted a delayed presentation of veterans with advanced infections and another increase in leg amputation incidence rate.

Like many health systems, MEDVAMC pivoted to telephone- and video-based outpatient encounters. Our team also used publicly available Texas hospitalization data to identify zip codes with particularly high leg amputation incidence rates, and > 3500 educational mailings to veterans categorized as moderate and high risk for leg amputation in these zip codes. These mailings provided information on recognizing foot ulcers and infections, emphasized timely evaluation, and named the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team as a point-of-contact. More recently, we have seen a further decrease in the MEDVAMC incidences of leg amputation to its lowest rate in > 20 years.

Discussion

A learning organization that directs its research based on clinical observations and informs its clinical care with research findings can produce palpable improvements in outcomes. Understanding the disease process and trying to better understand management across the entire range of this disease process has allowed our team to make consistent and systematic changes in care (Table). Consolidating inpatient care in a single team model seems to have been effective in reducing amputation rates among veterans with diabetes. The role the MEDVAMC vascular surgery team served for limb salvage patients may have been particularly beneficial because of the large impact untreated or unidentified PAD can have and because of the high prevalence of PAD among the limb salvage population seen at MEDVAMC. To be sustainable, though, a single-team model needs resources. A multiteam model can also be effective if the degree of multidisciplinary involvement for any given veteran is appropriate to the individual's clinical needs, teams are engaged and willing to contribute in a defined role within their specialty, and lines of communication remain open.

The primary challenge at MEDVAMC has been, and will continue to be, the retention of physicians and surgeons. MEDVAMC has excellent leadership and a collegial working environment, but better access to operating rooms for elective and time-sensitive operations, additional clinical staff support, and higher salary at non-VA positions have been the basis for many of physicians— especially surgeons—leaving MEDVAMC. Despite high staff turnover and a constant flow of resident and fellow trainees, MEDVAMC has been able to keep the clinical approach relatively consistent due to the use of written protocols and continuity of care as ≥ 1 physician or surgeon from each of the 4 main teams remained engaged with limb salvage throughout the entire period.

Going forward, we will work to ensure that all requirements of the 2022 Prevention of Amputation in Veterans Everywhere directive are incorporated into care.8 We plan to standardize MEDVAMC management algorithms further, both to streamline care and reduce the opportunity for disparities in treatment. More prophylactic podiatric procedures, surgical forms of offloading, and a shared multidisciplinary clinic space may also further help patients.

Conclusions

The introduction of multidisciplinary limb salvage at MEDVAMC has led to significant and sustained reductions in leg amputation incidence. These reductions do not seem dependent upon a specific team structure for inpatient care. To improve patient outcomes, efforts should focus on making improvements across the entire disease spectrum. For limb salvage, this includes primary prevention of foot ulcers, the treatment of foot infections, identification and management of PAD, surgical reconstruction/optimal wound healing, and care for patients who undergo leg amputation.

- Sanders LJ, Robbins JM, Edmonds ME. History of the team approach to amputation prevention: pioneers and milestones. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100(5):317- 334. doi:10.7547/1000317

- Sumpio BE, Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Andros G. The role of interdisciplinary team approach in the management of the diabetic foot: a joint statement from the society for vascular surgery and the American podiatric medical association. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100(4):309-311. doi:10.7547/1000309

- About learning health systems. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published March 2019. Updated May 2019. Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html

- Barshes NR, Minc SD. Healthcare disparities in vascular surgery: a critical review. J Vasc Surg. 2021;74(2S):6S-14S.

- Barshes NR, Mindru C, Ashong C, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Trautner BW. Treatment failure and leg amputation among patients with foot osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15(4):303-312. doi:10.1177/1534734616661058

- Barshes NR, Flores E, Belkin M, Kougias P, Armstrong DG, Mills JL Sr. The accuracy and cost-effectiveness of strategies used to identify peripheral artery disease among patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(6):1682-1690.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.056 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2021.03.055

- Choi JC, Miranda J, Greenleaf E, et al. Lower-extremity pressure, staging, and grading thresholds to identify chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Vasc Med. 2023;28(1):45-53. doi:10.1177/1358863X221147945

- Barshes NR, Chambers JD, Cohen J, Belkin M; Model To Optimize Healthcare Value in Ischemic Extremities 1 (MOVIE) Study Collaborators. Cost-effectiveness in the contemporary management of critical limb ischemia with tissue loss. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):1015-24.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.069

- Barshes NR, Bechara CF, Pisimisis G, Kougias P. Preliminary experiences with early primary closure of foot wounds after lower extremity revascularization. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(1):48-52. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.06.012

- Barshes NR, Gold B, Garcia A, Bechara CF, Pisimisis G, Kougias P. Minor amputation and palliative wound care as a strategy to avoid major amputation in patients with foot infections and severe peripheral arterial disease. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2014;13(3):211-219. doi:10.1177/1534734614543663

- Garcia M, Hernandez B, Ellington TG, et al. A lack of decline in major nontraumatic amputations in Texas: contemporary trends, risk factor associations, and impact of revascularization. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(6):1061-1066. doi:10.2337/dc19-0078

- Zamani N, Sharath SE, Vo E, Awad SS, Kougias P, Barshes NR. A multi-component strategy to decrease wound complications after open infra-inguinal re-vascularization. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2018;19(1):87-94. doi:10.1089/sur.2017.193

- Barshes NR, Ozaki CK, Kougias P, Belkin M. A costeffectiveness analysis of infrainguinal bypass in the absence of great saphenous vein conduit. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(6):1466-1470. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.115

- Zamani N, Sharath S, Browder R, et al. PC158 longterm outcomes after endovascular stent placement for symptomatic, long-segment superficial femoral artery lesions. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(6):182S-183S. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2017.03.344

- Zamani N, Sharath SE, Browder RC, et al. Outcomes after endovascular stent placement for long-segment superficial femoral artery lesions. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;71:298-307. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2020.08.124

- Sanders LJ, Robbins JM, Edmonds ME. History of the team approach to amputation prevention: pioneers and milestones. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100(5):317- 334. doi:10.7547/1000317

- Sumpio BE, Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Andros G. The role of interdisciplinary team approach in the management of the diabetic foot: a joint statement from the society for vascular surgery and the American podiatric medical association. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100(4):309-311. doi:10.7547/1000309

- About learning health systems. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published March 2019. Updated May 2019. Accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html

- Barshes NR, Minc SD. Healthcare disparities in vascular surgery: a critical review. J Vasc Surg. 2021;74(2S):6S-14S.

- Barshes NR, Mindru C, Ashong C, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Trautner BW. Treatment failure and leg amputation among patients with foot osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15(4):303-312. doi:10.1177/1534734616661058

- Barshes NR, Flores E, Belkin M, Kougias P, Armstrong DG, Mills JL Sr. The accuracy and cost-effectiveness of strategies used to identify peripheral artery disease among patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(6):1682-1690.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.056 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2021.03.055

- Choi JC, Miranda J, Greenleaf E, et al. Lower-extremity pressure, staging, and grading thresholds to identify chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Vasc Med. 2023;28(1):45-53. doi:10.1177/1358863X221147945

- Barshes NR, Chambers JD, Cohen J, Belkin M; Model To Optimize Healthcare Value in Ischemic Extremities 1 (MOVIE) Study Collaborators. Cost-effectiveness in the contemporary management of critical limb ischemia with tissue loss. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):1015-24.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.069

- Barshes NR, Bechara CF, Pisimisis G, Kougias P. Preliminary experiences with early primary closure of foot wounds after lower extremity revascularization. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(1):48-52. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.06.012

- Barshes NR, Gold B, Garcia A, Bechara CF, Pisimisis G, Kougias P. Minor amputation and palliative wound care as a strategy to avoid major amputation in patients with foot infections and severe peripheral arterial disease. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2014;13(3):211-219. doi:10.1177/1534734614543663

- Garcia M, Hernandez B, Ellington TG, et al. A lack of decline in major nontraumatic amputations in Texas: contemporary trends, risk factor associations, and impact of revascularization. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(6):1061-1066. doi:10.2337/dc19-0078

- Zamani N, Sharath SE, Vo E, Awad SS, Kougias P, Barshes NR. A multi-component strategy to decrease wound complications after open infra-inguinal re-vascularization. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2018;19(1):87-94. doi:10.1089/sur.2017.193

- Barshes NR, Ozaki CK, Kougias P, Belkin M. A costeffectiveness analysis of infrainguinal bypass in the absence of great saphenous vein conduit. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(6):1466-1470. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.115

- Zamani N, Sharath S, Browder R, et al. PC158 longterm outcomes after endovascular stent placement for symptomatic, long-segment superficial femoral artery lesions. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(6):182S-183S. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2017.03.344

- Zamani N, Sharath SE, Browder RC, et al. Outcomes after endovascular stent placement for long-segment superficial femoral artery lesions. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;71:298-307. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2020.08.124

Evaluating Use of Empagliflozin for Diabetes Management in Veterans With Chronic Kidney Disease

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes mellitus (DM), and approximately 90% have type 2 DM (T2DM), including about 25% of veterans.1,2 The current guidelines suggest that therapy depends on a patient's comorbidities, management needs, and patient-centered treatment factors.3 About 1 in 3 adults with DM have chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as the presence of kidney damage or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, persisting for ≥ 3 months.4

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors are a class of antihyperglycemic agents acting on the SGLT-2 proteins expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubules. They exert their effects by preventing the reabsorption of filtered glucose from the tubular lumen. There are 4 SGLT-2 inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin. Empagliflozin is currently the preferred SGLT-2 inhibitor on the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary.

According to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, empagliflozin is considered when an individual has or is at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and CKD.3 SGLT-2 inhibitors are a favorable option due to their low risk for hypoglycemia while also promoting weight loss. The EMPEROR-Reduced trial demonstrated that, in addition to benefits for patients with heart failure, empagliflozin also slowed the progressive decline in kidney function in those with and without DM.5 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of empagliflozin on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with CKD at the Hershel “Woody” Williams VA Medical Center (HWWVAMC) in Huntington, West Virginia, along with other laboratory test markers.

Methods

The Marshall University Institutional Review Board #1 (Medical) and the HWWVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee each reviewed and approved this study. A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients diagnosed with T2DM and stage 3 CKD who were prescribed empagliflozin for DM management between January 1, 2015, and October 1, 2022, yielding 1771 patients. Data were obtained through the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and stored on the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) research server.

Patients were included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed empagliflozin by a VA clinician for the treatment of T2DM, had an eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, and had an initial HbA1c between 7% and 10%. Using further random sampling, patients were either excluded or divided into, those with stage 3a CKD and those with stage 3b CKD. The primary endpoint of this study was the change in HbA1c levels in patients with stage 3b CKD (eGFR 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m2) compared with stage 3a (eGFR 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) after 12 months. The secondary endpoints included effects on renal function, weight, blood pressure, incidence of adverse drug events, and cardiovascular events. Of the excluded, 38 had HbA1c < 7%, 30 had HbA1c ≥ 10%, 21 did not have data at 1-year mark, 15 had the medication discontinued due to decline in renal function, 14 discontinued their medication without documented reason, 10 discontinued their medication due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs), 12 had eGFR > 60 mL/ min/1.73 m2, 9 died within 1 year of initiation, 4 had eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 1 had no baseline eGFR, and 1 was the spouse of a veteran.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. We used t tests to examine changes within each group, along with paired t tests to compare the 2 groups. Two-sample t tests were used to analyze the continuous data at both the primary and secondary endpoints.

Results

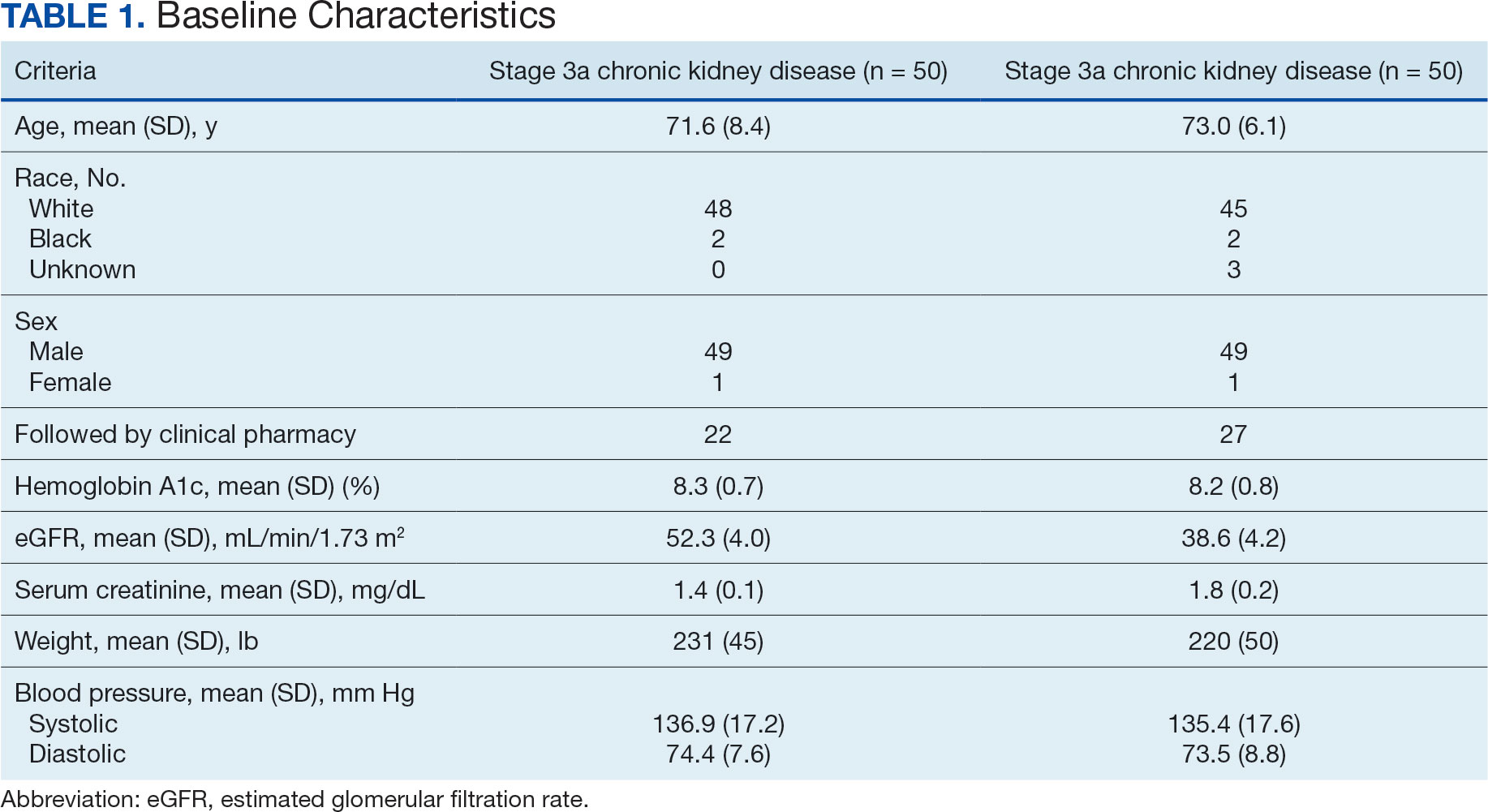

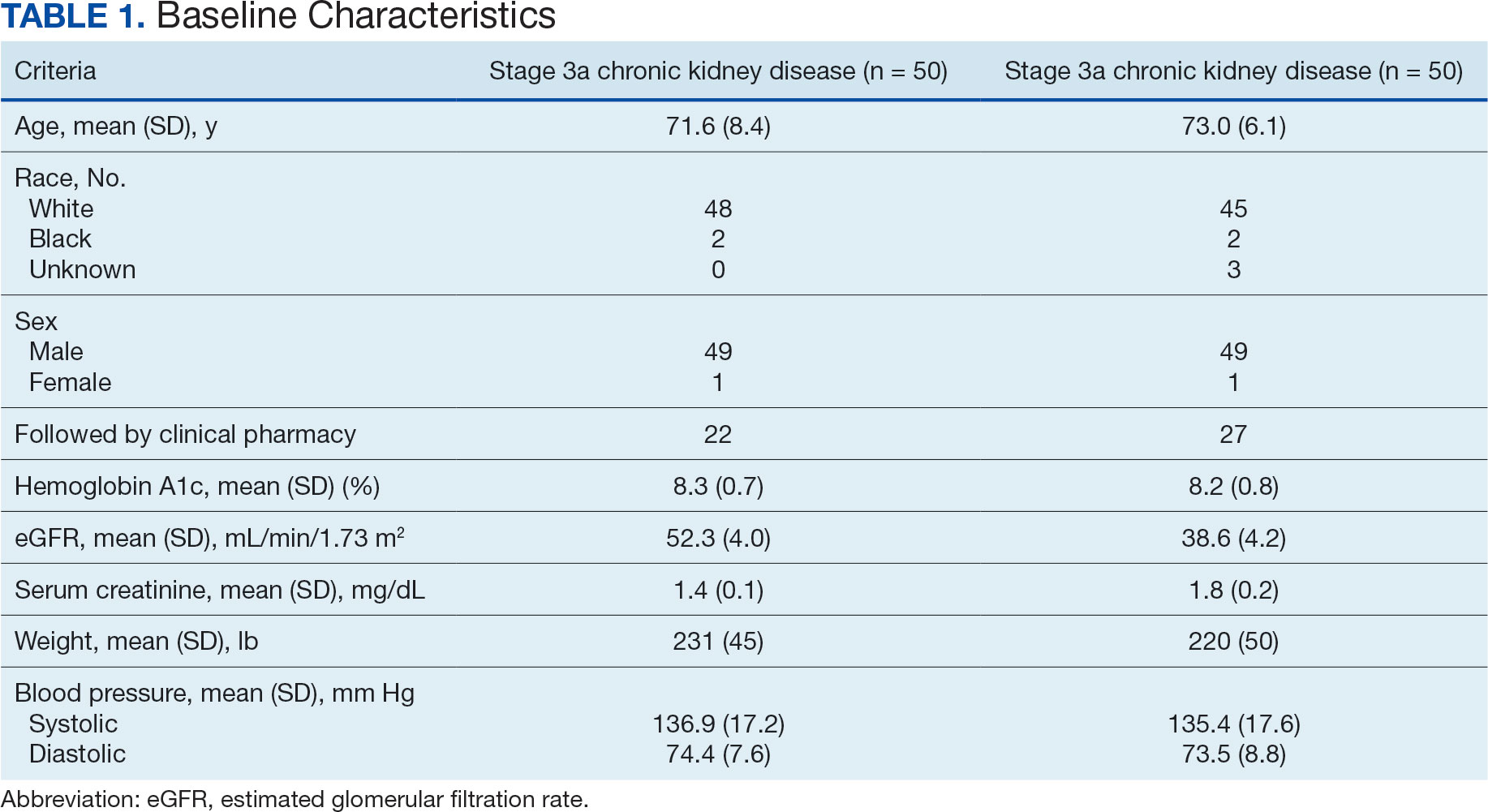

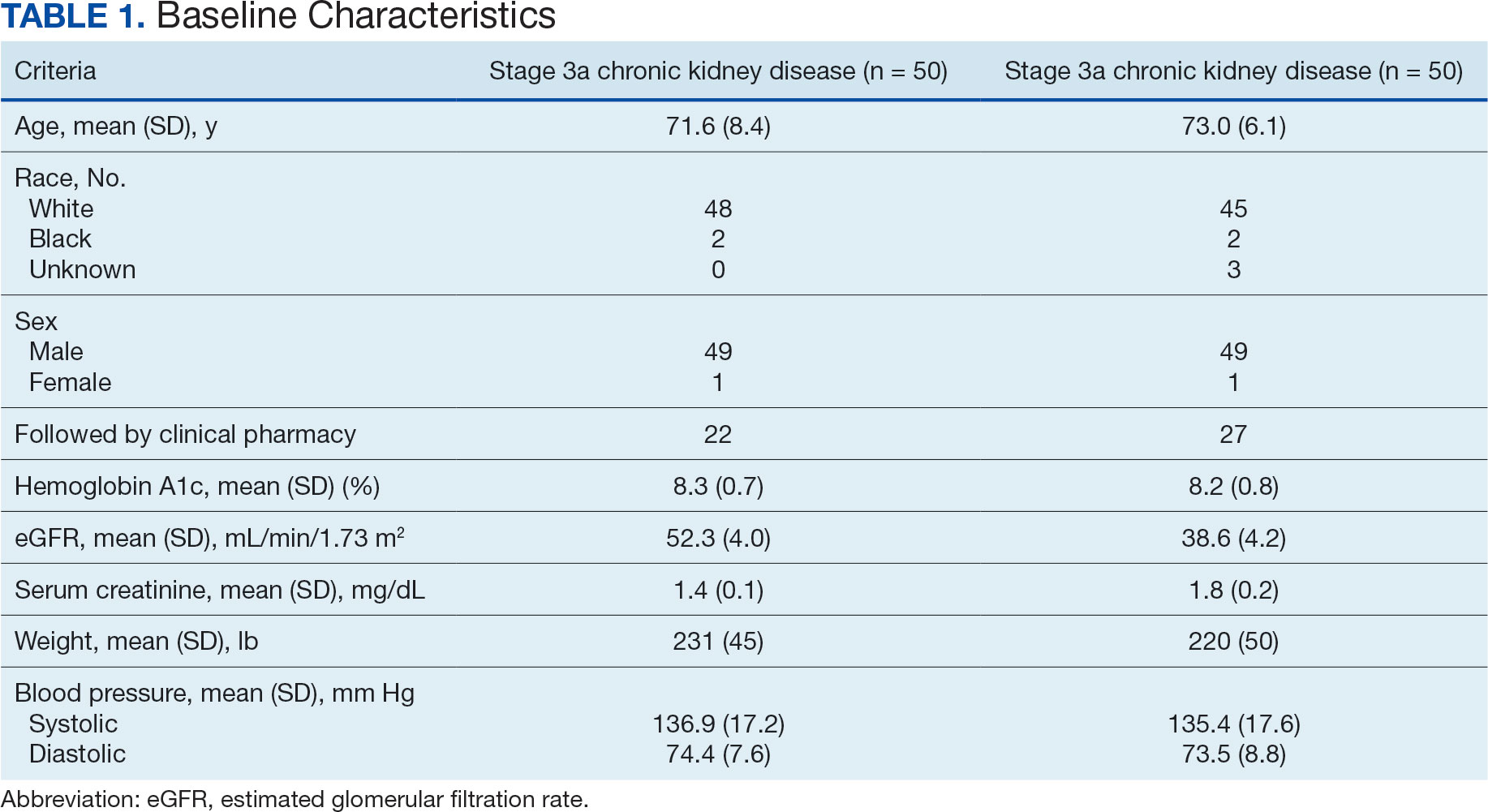

Of the 1771 patients included in the initial data set, a randomized sample of 255 charts were reviewed, 155 were excluded, and 100 were included. Fifty patients, had stage 3a CKD and 50 had stage 3b CKD. Baseline demographics were similar between the stage 3a and 3b groups (Table 1). Both groups were predominantly White and male, with mean age > 70 years.

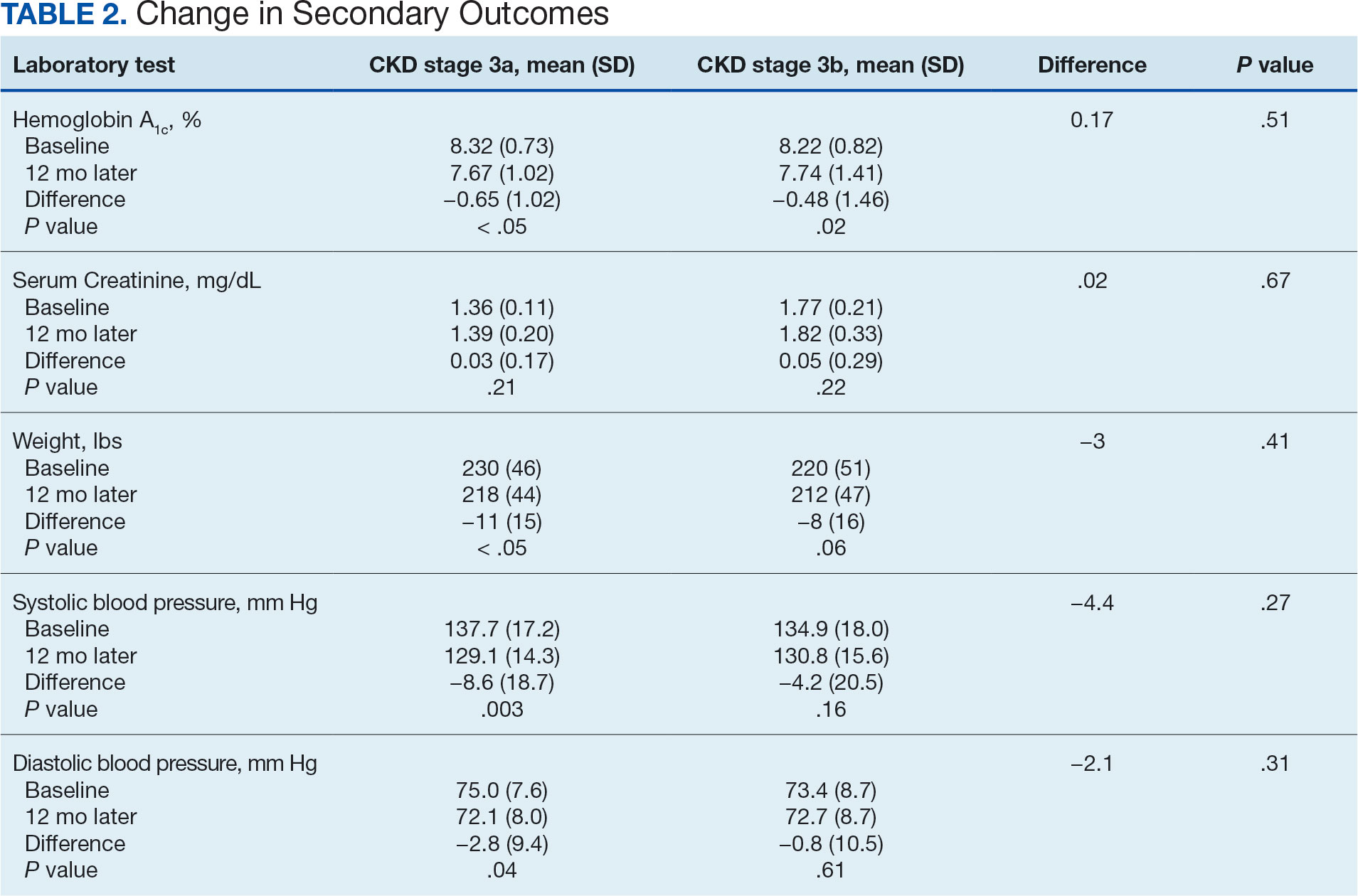

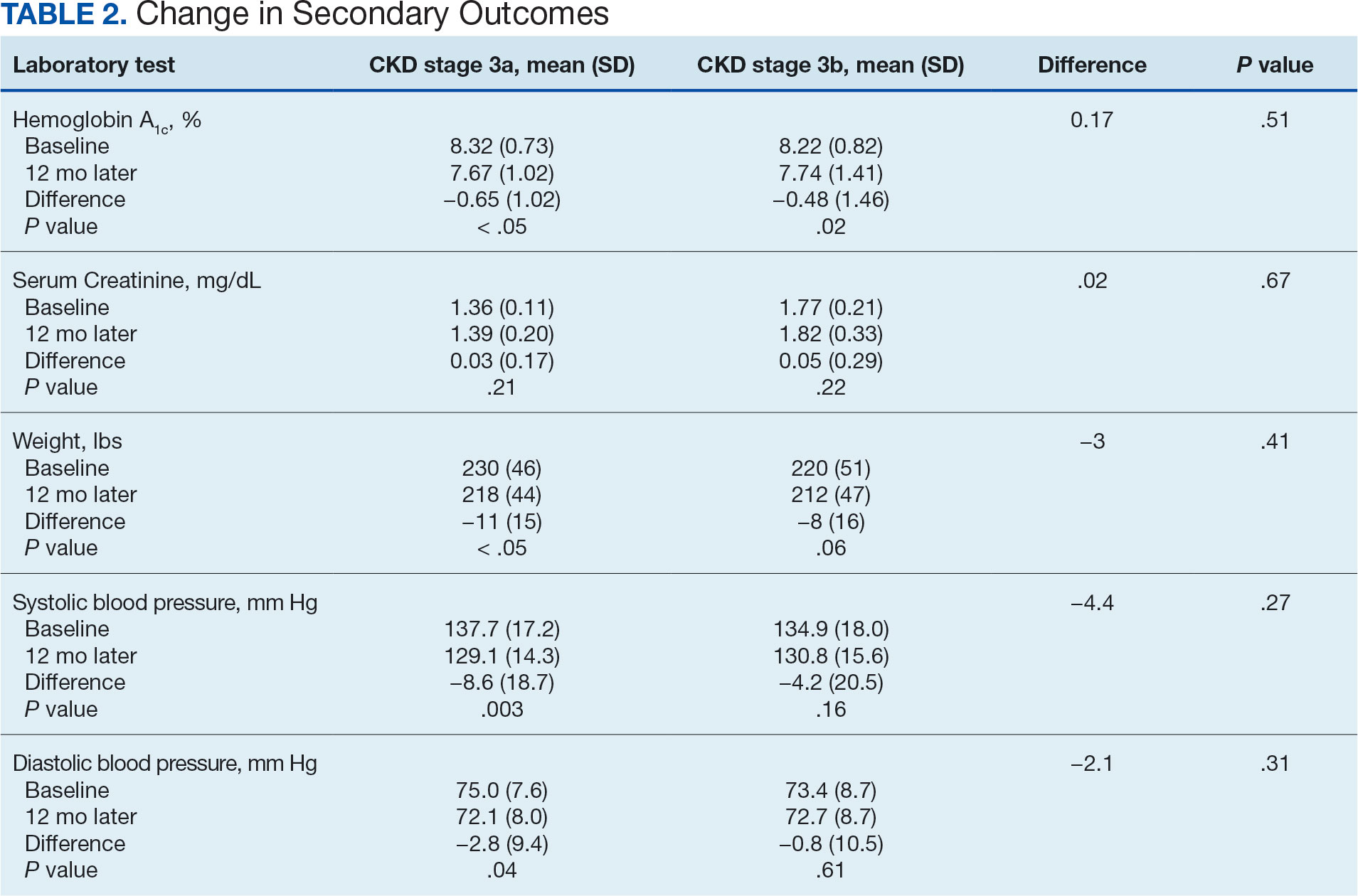

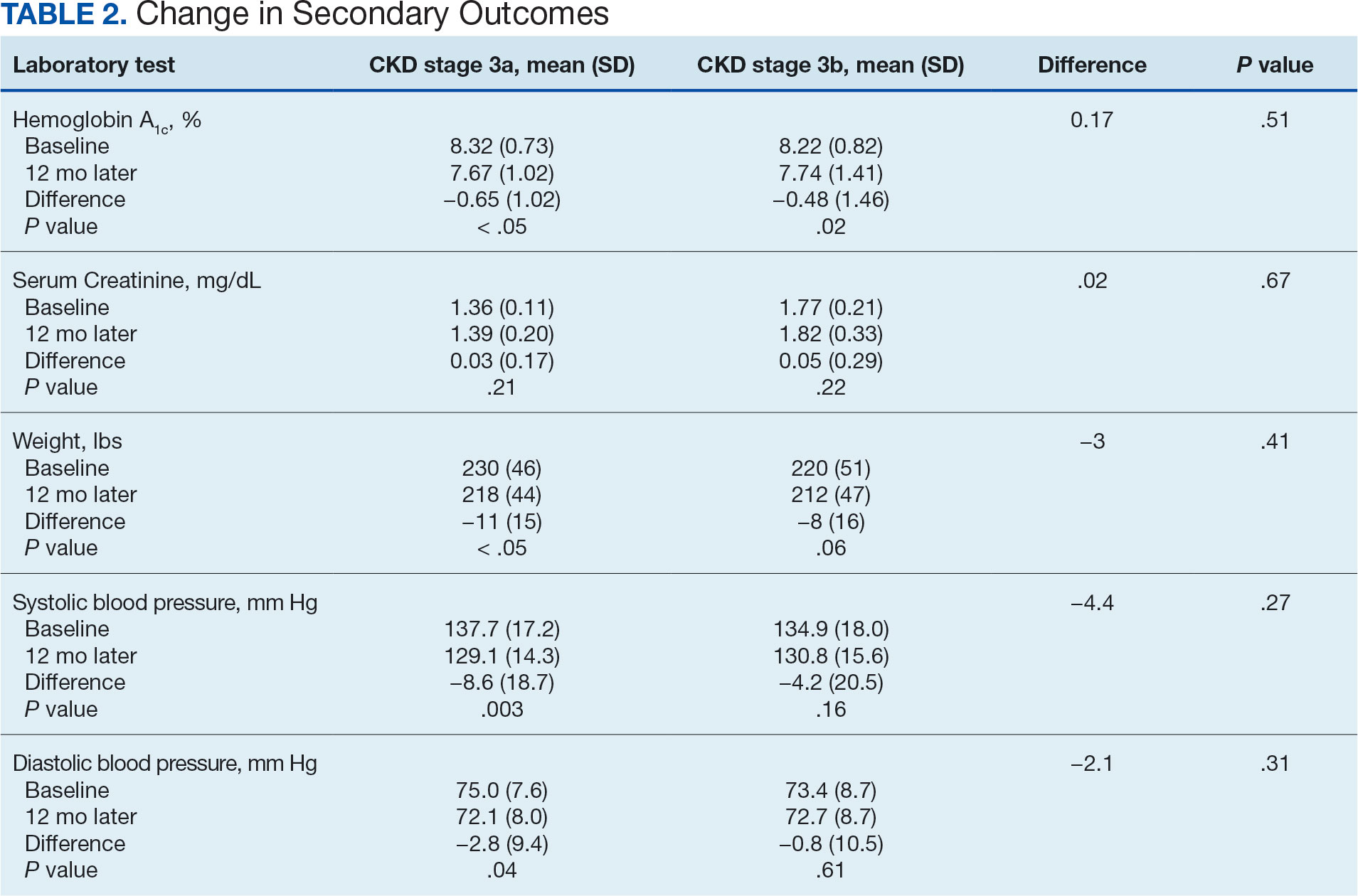

The primary endpoint was the differences in HbA1c levels over time and between groups for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD 1 year after initiation of empagliflozin. The starting doses of empagliflozin were either 12.5 mg or 25.0 mg. For both groups, the changes in HbA1c levels were statistically significant (Table 2). HbA1c levels dropped 0.65% for the stage 3a group and 0.48% for the 3b group. When compared to one another, the results were not statistically significant (P = .51).

Secondary Endpoint

There was no statistically significant difference in serum creatinine levels within each group between baselines and 1 year later for the stage 3a (P = .21) and stage 3b (P = .22) groups, or when compared to each other (P = .67). There were statistically significant changes in weight for patients in the stage 3a group (P < .05), but not for stage 3b group (P = .06) or when compared to each other (P = .41). A statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure was observed for the stage 3a group (P = .003), but not the stage 3b group (P = .16) or when compared to each other (P = .27). There were statistically significant changes in diastolic blood pressure within the stage 3a group (P = .04), but not within the stage 3b group (P = .61) or when compared to each other (P = .31).

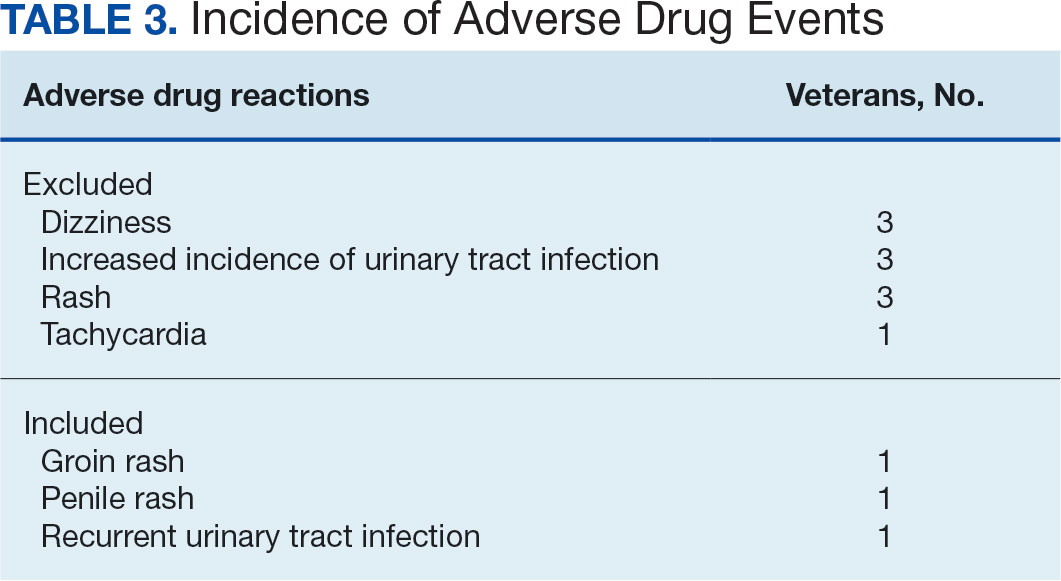

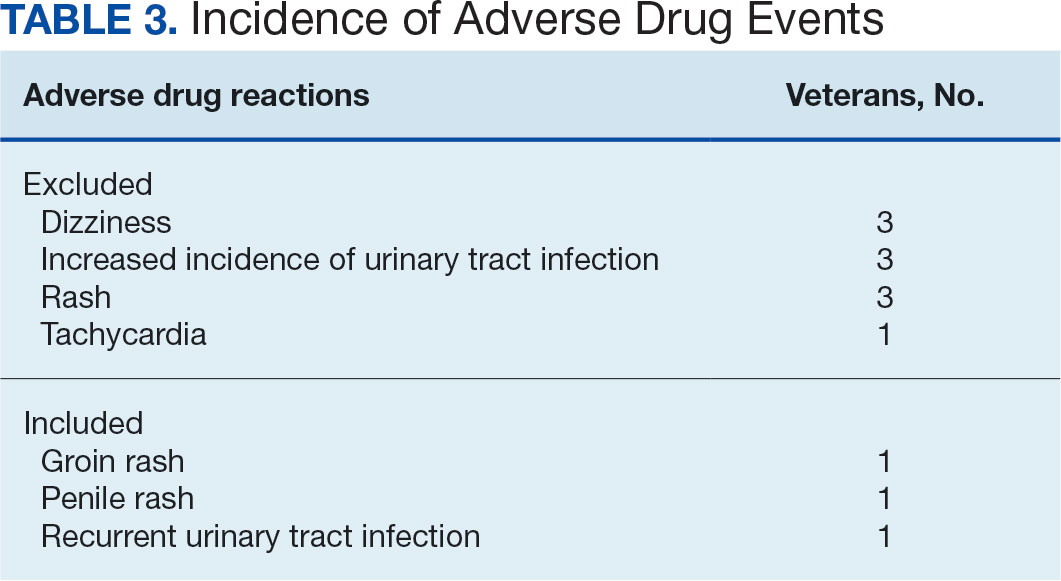

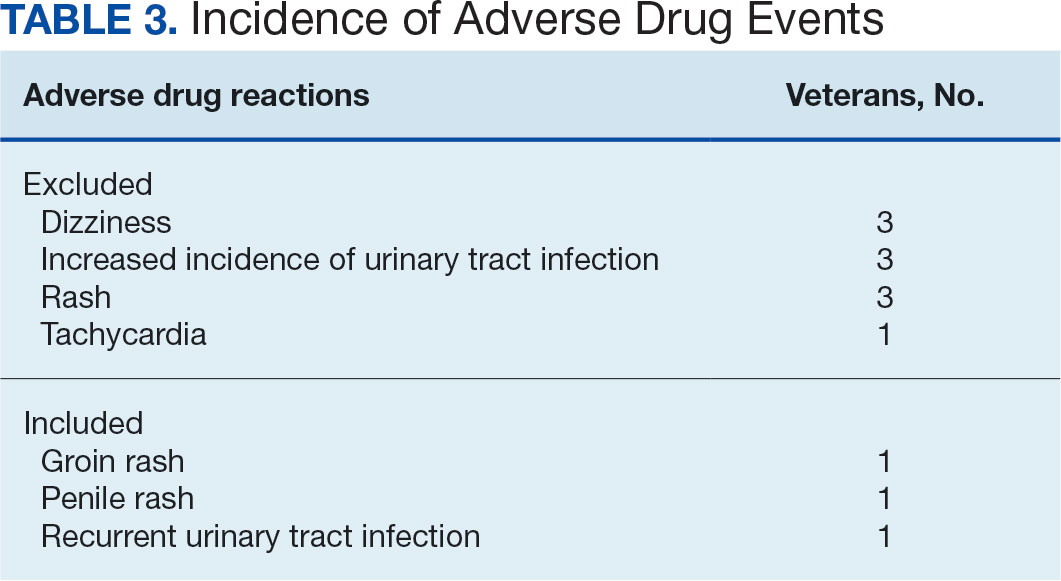

Ten patients discontinued empagliflozin before the 1-year mark due to ADRs, including dizziness, increased incidence of urinary tract infections, rash, and tachycardia (Table 3). Additionally, 3 ADRs resulted in the empagliflozin discontinuation after 1 year (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c levels for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD. With eGFR levels in these 2 groups > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients were able to achieve glycemic benefits. There were no significant changes to the serum creatinine levels. Both groups saw statistically significant changes in weight loss within their own group; however, there were no statistically significant changes when compared to each other. With both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the stage 3a group had statistically significant changes.

The EMPA-REG BP study demonstrated that empagliflozin was associated with significant and clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure and HbA1c levels compared with placebo and was well tolerated in patients with T2DM and hypertension.6,7,8

Limitations

This study had a retrospective study design, which resulted in missing information for many patients and higher rates of exclusion. The population was predominantly older, White, and male and may not reflect other populations. The starting doses of empagliflozin varied between the groups. The VA employs tablet splitting for some patients, and the available doses were either 10.0 mg, 12.5 mg, or 25.0 mg. Some prescribers start veterans at lower doses and gradually increase to the higher dose of 25.0 mg, adding to the variability in starting doses.

Patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 make it difficult to determine any potential benefit in this population. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial demonstrated that the benefits of empagliflozin treatment were consistent among patients with or without DM and regardless of eGFR at randomization.9 Furthermore, many veterans had an initial HbA1c levels outside the inclusion criteria range, which was a factor in the smaller sample size.

Conclusions

While the reduction in HbA1c levels was less in patients with stage 3b CKD compared to patients stage 3a CKD, all patients experienced a benefit. The overall incidence of ADRs was low in the study population, showing empagliflozin as a favorable choice for those with T2DM and CKD. Based on the findings of this study, empagliflozin is a potentially beneficial option for reducing HbA1c levels in patients with CKD.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 diabetes. Updated May 25, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/about-type-2-diabetes.html?CDC_AAref_Val

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA research on diabetes. Updated September 2019. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/Diabetes.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2022;40(1):10-38. doi:10.2337/cd22-as01

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes, chronic kidney disease. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/diabetes-complications/diabetes-and-chronic-kidney-disease.html

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413-1424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022190

- Tikkanen I, Narko K, Zeller C, et al. Empagliflozin reduces blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(3):420-428. doi:10.2337/dc14-1096

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504720

- Chilton R, Tikkanen I, Cannon CP, et al. Effects of empagliflozin on blood pressure and markers of arterial stiffness and vascular resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(12):1180-1193. doi:10.1111/dom.12572

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group, Herrington WG, Staplin N, et al. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):117-127. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2204233

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes mellitus (DM), and approximately 90% have type 2 DM (T2DM), including about 25% of veterans.1,2 The current guidelines suggest that therapy depends on a patient's comorbidities, management needs, and patient-centered treatment factors.3 About 1 in 3 adults with DM have chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as the presence of kidney damage or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, persisting for ≥ 3 months.4

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors are a class of antihyperglycemic agents acting on the SGLT-2 proteins expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubules. They exert their effects by preventing the reabsorption of filtered glucose from the tubular lumen. There are 4 SGLT-2 inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin. Empagliflozin is currently the preferred SGLT-2 inhibitor on the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary.

According to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, empagliflozin is considered when an individual has or is at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and CKD.3 SGLT-2 inhibitors are a favorable option due to their low risk for hypoglycemia while also promoting weight loss. The EMPEROR-Reduced trial demonstrated that, in addition to benefits for patients with heart failure, empagliflozin also slowed the progressive decline in kidney function in those with and without DM.5 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of empagliflozin on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with CKD at the Hershel “Woody” Williams VA Medical Center (HWWVAMC) in Huntington, West Virginia, along with other laboratory test markers.

Methods

The Marshall University Institutional Review Board #1 (Medical) and the HWWVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee each reviewed and approved this study. A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients diagnosed with T2DM and stage 3 CKD who were prescribed empagliflozin for DM management between January 1, 2015, and October 1, 2022, yielding 1771 patients. Data were obtained through the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and stored on the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) research server.

Patients were included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed empagliflozin by a VA clinician for the treatment of T2DM, had an eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, and had an initial HbA1c between 7% and 10%. Using further random sampling, patients were either excluded or divided into, those with stage 3a CKD and those with stage 3b CKD. The primary endpoint of this study was the change in HbA1c levels in patients with stage 3b CKD (eGFR 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m2) compared with stage 3a (eGFR 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) after 12 months. The secondary endpoints included effects on renal function, weight, blood pressure, incidence of adverse drug events, and cardiovascular events. Of the excluded, 38 had HbA1c < 7%, 30 had HbA1c ≥ 10%, 21 did not have data at 1-year mark, 15 had the medication discontinued due to decline in renal function, 14 discontinued their medication without documented reason, 10 discontinued their medication due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs), 12 had eGFR > 60 mL/ min/1.73 m2, 9 died within 1 year of initiation, 4 had eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 1 had no baseline eGFR, and 1 was the spouse of a veteran.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. We used t tests to examine changes within each group, along with paired t tests to compare the 2 groups. Two-sample t tests were used to analyze the continuous data at both the primary and secondary endpoints.

Results

Of the 1771 patients included in the initial data set, a randomized sample of 255 charts were reviewed, 155 were excluded, and 100 were included. Fifty patients, had stage 3a CKD and 50 had stage 3b CKD. Baseline demographics were similar between the stage 3a and 3b groups (Table 1). Both groups were predominantly White and male, with mean age > 70 years.

The primary endpoint was the differences in HbA1c levels over time and between groups for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD 1 year after initiation of empagliflozin. The starting doses of empagliflozin were either 12.5 mg or 25.0 mg. For both groups, the changes in HbA1c levels were statistically significant (Table 2). HbA1c levels dropped 0.65% for the stage 3a group and 0.48% for the 3b group. When compared to one another, the results were not statistically significant (P = .51).

Secondary Endpoint

There was no statistically significant difference in serum creatinine levels within each group between baselines and 1 year later for the stage 3a (P = .21) and stage 3b (P = .22) groups, or when compared to each other (P = .67). There were statistically significant changes in weight for patients in the stage 3a group (P < .05), but not for stage 3b group (P = .06) or when compared to each other (P = .41). A statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure was observed for the stage 3a group (P = .003), but not the stage 3b group (P = .16) or when compared to each other (P = .27). There were statistically significant changes in diastolic blood pressure within the stage 3a group (P = .04), but not within the stage 3b group (P = .61) or when compared to each other (P = .31).

Ten patients discontinued empagliflozin before the 1-year mark due to ADRs, including dizziness, increased incidence of urinary tract infections, rash, and tachycardia (Table 3). Additionally, 3 ADRs resulted in the empagliflozin discontinuation after 1 year (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c levels for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD. With eGFR levels in these 2 groups > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients were able to achieve glycemic benefits. There were no significant changes to the serum creatinine levels. Both groups saw statistically significant changes in weight loss within their own group; however, there were no statistically significant changes when compared to each other. With both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the stage 3a group had statistically significant changes.

The EMPA-REG BP study demonstrated that empagliflozin was associated with significant and clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure and HbA1c levels compared with placebo and was well tolerated in patients with T2DM and hypertension.6,7,8

Limitations

This study had a retrospective study design, which resulted in missing information for many patients and higher rates of exclusion. The population was predominantly older, White, and male and may not reflect other populations. The starting doses of empagliflozin varied between the groups. The VA employs tablet splitting for some patients, and the available doses were either 10.0 mg, 12.5 mg, or 25.0 mg. Some prescribers start veterans at lower doses and gradually increase to the higher dose of 25.0 mg, adding to the variability in starting doses.

Patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 make it difficult to determine any potential benefit in this population. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial demonstrated that the benefits of empagliflozin treatment were consistent among patients with or without DM and regardless of eGFR at randomization.9 Furthermore, many veterans had an initial HbA1c levels outside the inclusion criteria range, which was a factor in the smaller sample size.

Conclusions

While the reduction in HbA1c levels was less in patients with stage 3b CKD compared to patients stage 3a CKD, all patients experienced a benefit. The overall incidence of ADRs was low in the study population, showing empagliflozin as a favorable choice for those with T2DM and CKD. Based on the findings of this study, empagliflozin is a potentially beneficial option for reducing HbA1c levels in patients with CKD.

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes mellitus (DM), and approximately 90% have type 2 DM (T2DM), including about 25% of veterans.1,2 The current guidelines suggest that therapy depends on a patient's comorbidities, management needs, and patient-centered treatment factors.3 About 1 in 3 adults with DM have chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as the presence of kidney damage or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, persisting for ≥ 3 months.4

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors are a class of antihyperglycemic agents acting on the SGLT-2 proteins expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubules. They exert their effects by preventing the reabsorption of filtered glucose from the tubular lumen. There are 4 SGLT-2 inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin. Empagliflozin is currently the preferred SGLT-2 inhibitor on the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary.

According to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, empagliflozin is considered when an individual has or is at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and CKD.3 SGLT-2 inhibitors are a favorable option due to their low risk for hypoglycemia while also promoting weight loss. The EMPEROR-Reduced trial demonstrated that, in addition to benefits for patients with heart failure, empagliflozin also slowed the progressive decline in kidney function in those with and without DM.5 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of empagliflozin on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with CKD at the Hershel “Woody” Williams VA Medical Center (HWWVAMC) in Huntington, West Virginia, along with other laboratory test markers.

Methods

The Marshall University Institutional Review Board #1 (Medical) and the HWWVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee each reviewed and approved this study. A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients diagnosed with T2DM and stage 3 CKD who were prescribed empagliflozin for DM management between January 1, 2015, and October 1, 2022, yielding 1771 patients. Data were obtained through the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and stored on the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) research server.

Patients were included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed empagliflozin by a VA clinician for the treatment of T2DM, had an eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, and had an initial HbA1c between 7% and 10%. Using further random sampling, patients were either excluded or divided into, those with stage 3a CKD and those with stage 3b CKD. The primary endpoint of this study was the change in HbA1c levels in patients with stage 3b CKD (eGFR 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m2) compared with stage 3a (eGFR 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) after 12 months. The secondary endpoints included effects on renal function, weight, blood pressure, incidence of adverse drug events, and cardiovascular events. Of the excluded, 38 had HbA1c < 7%, 30 had HbA1c ≥ 10%, 21 did not have data at 1-year mark, 15 had the medication discontinued due to decline in renal function, 14 discontinued their medication without documented reason, 10 discontinued their medication due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs), 12 had eGFR > 60 mL/ min/1.73 m2, 9 died within 1 year of initiation, 4 had eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 1 had no baseline eGFR, and 1 was the spouse of a veteran.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. We used t tests to examine changes within each group, along with paired t tests to compare the 2 groups. Two-sample t tests were used to analyze the continuous data at both the primary and secondary endpoints.

Results

Of the 1771 patients included in the initial data set, a randomized sample of 255 charts were reviewed, 155 were excluded, and 100 were included. Fifty patients, had stage 3a CKD and 50 had stage 3b CKD. Baseline demographics were similar between the stage 3a and 3b groups (Table 1). Both groups were predominantly White and male, with mean age > 70 years.

The primary endpoint was the differences in HbA1c levels over time and between groups for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD 1 year after initiation of empagliflozin. The starting doses of empagliflozin were either 12.5 mg or 25.0 mg. For both groups, the changes in HbA1c levels were statistically significant (Table 2). HbA1c levels dropped 0.65% for the stage 3a group and 0.48% for the 3b group. When compared to one another, the results were not statistically significant (P = .51).

Secondary Endpoint

There was no statistically significant difference in serum creatinine levels within each group between baselines and 1 year later for the stage 3a (P = .21) and stage 3b (P = .22) groups, or when compared to each other (P = .67). There were statistically significant changes in weight for patients in the stage 3a group (P < .05), but not for stage 3b group (P = .06) or when compared to each other (P = .41). A statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure was observed for the stage 3a group (P = .003), but not the stage 3b group (P = .16) or when compared to each other (P = .27). There were statistically significant changes in diastolic blood pressure within the stage 3a group (P = .04), but not within the stage 3b group (P = .61) or when compared to each other (P = .31).

Ten patients discontinued empagliflozin before the 1-year mark due to ADRs, including dizziness, increased incidence of urinary tract infections, rash, and tachycardia (Table 3). Additionally, 3 ADRs resulted in the empagliflozin discontinuation after 1 year (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c levels for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD. With eGFR levels in these 2 groups > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients were able to achieve glycemic benefits. There were no significant changes to the serum creatinine levels. Both groups saw statistically significant changes in weight loss within their own group; however, there were no statistically significant changes when compared to each other. With both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the stage 3a group had statistically significant changes.

The EMPA-REG BP study demonstrated that empagliflozin was associated with significant and clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure and HbA1c levels compared with placebo and was well tolerated in patients with T2DM and hypertension.6,7,8

Limitations

This study had a retrospective study design, which resulted in missing information for many patients and higher rates of exclusion. The population was predominantly older, White, and male and may not reflect other populations. The starting doses of empagliflozin varied between the groups. The VA employs tablet splitting for some patients, and the available doses were either 10.0 mg, 12.5 mg, or 25.0 mg. Some prescribers start veterans at lower doses and gradually increase to the higher dose of 25.0 mg, adding to the variability in starting doses.

Patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 make it difficult to determine any potential benefit in this population. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial demonstrated that the benefits of empagliflozin treatment were consistent among patients with or without DM and regardless of eGFR at randomization.9 Furthermore, many veterans had an initial HbA1c levels outside the inclusion criteria range, which was a factor in the smaller sample size.

Conclusions

While the reduction in HbA1c levels was less in patients with stage 3b CKD compared to patients stage 3a CKD, all patients experienced a benefit. The overall incidence of ADRs was low in the study population, showing empagliflozin as a favorable choice for those with T2DM and CKD. Based on the findings of this study, empagliflozin is a potentially beneficial option for reducing HbA1c levels in patients with CKD.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 diabetes. Updated May 25, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/about-type-2-diabetes.html?CDC_AAref_Val

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA research on diabetes. Updated September 2019. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/Diabetes.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2022;40(1):10-38. doi:10.2337/cd22-as01