User login

Valacyclovir safely cut vertical CMV transmission

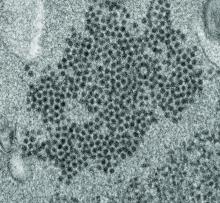

WASHINGTON – Daily treatment with valacyclovir for at least 6 weeks safely cut the cytomegalovirus (CMV) vertical transmission rate from mothers to fetuses in women with a primary CMV infection during the three weeks before conception through their first trimester. That finding emerged from a randomized, controlled, single-center Israeli study with 92 women.

The rate of congenital fetal infection with CMV was 11% among neonates born to 45 women treated with 8 g/day of valacyclovir, compared with a 30% rate among the infants born to 47 women who received placebo, a statistically significant difference, Keren Shahar-Nissan, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. The results also showed that the valacyclovir regimen was well tolerated, with no increase compared with placebo in adverse events and with no need for dosage adjustment regardless of a 16 pill/day regimen to deliver the 8 g/day of valacyclovir or placebo that participants received.

Dr. Shahar-Nissan said that she and her associates felt comfortable administering this amount of valacyclovir to pregnant woman given previous reports of the safety of this dosage for both women and their fetuses. These reports included 20 pregnant women safely treated for 7 weeks with 8 g/day during the late second or early third trimester (BJOG. 2007 Sept;114[9]:1113-21); more than 600 women in a Danish nationwide study treated with any dosage of valacyclovir during preconception, the first trimester, or the second or third trimesters with a prevalence of births defects not significantly different from unexposed pregnancies (JAMA. 2010 Aug 25;304[8]:859-66); and a prospective, open-label study of 8 g/day valacyclovir to treat 43 women carrying CMV-infected fetuses starting at a median 26 weeks gestation and continuing through delivery (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Oct;215[4]:462.e1-462.e10).

The study she ran enrolled women seen at Helen Schneider Hospital for Women in Petah Tikva, Israel, during November 2015-October 2018 who had a serologically-proven primary CMV infection that began at any time from 3 weeks before conception through the first trimester, excluding patients with renal dysfunction, liver disease, bone-marrow suppression, or acyclovir sensitivity. Screening for active CMV infection is common among newly-pregnant Israeli women, usually at the time of their first obstetrical consultation for a suspected pregnancy, noted Dr. Shahar-Nissan, a pediatrician at Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel in Petah Tikva. About a quarter of the enrolled women became infected during the 3 weeks prior to conception, and nearly two-thirds became infected during the first 8 weeks of pregnancy.

The valacyclovir intervention appeared to be effective specifically for preventing vertical transmission of infection acquired early during pregnancy. In this subgroup the transmission rate was 11% with valacyclovir treatment and 48% on placebo. Valacyclovir seemed to have no effect on vertical transmission of infections that began before conception, likely because treatment began too late to prevent transmission.

“I think this study is enough” to convince the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to add this treatment indication to the labeling of valacyclovir, a drug that has been available in generic formulations for many years, Dr. Shahar-Nissan said in an interview. Before approaching the FDA, her first goal is publishing the findings, she added.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

This small Israeli study is very important. The powerful finding of the study was buttressed by its placebo-controlled design and by its follow-up. The findings need replication in a larger study, but despite the small size of the current study the findings are noteworthy because of the desperate need for a safe and effective intervention to reduce the risk for maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus (CMV) when a woman has a first infection just before conception or early during pregnancy. Several years ago, the Institute of Medicine made prevention of prenatal CMV transmission (by vaccination) a major health priority based on the high estimated burden of congenital CMV infection, Addressing this still unmet need remains an important goal given the substantial disability that congenital CMV causes for thousands of infants born each year.

Janet A. Englund, MD, is a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Washington in Seattle and at Seattle Children’s Hospital. She had no relevant disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

This small Israeli study is very important. The powerful finding of the study was buttressed by its placebo-controlled design and by its follow-up. The findings need replication in a larger study, but despite the small size of the current study the findings are noteworthy because of the desperate need for a safe and effective intervention to reduce the risk for maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus (CMV) when a woman has a first infection just before conception or early during pregnancy. Several years ago, the Institute of Medicine made prevention of prenatal CMV transmission (by vaccination) a major health priority based on the high estimated burden of congenital CMV infection, Addressing this still unmet need remains an important goal given the substantial disability that congenital CMV causes for thousands of infants born each year.

Janet A. Englund, MD, is a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Washington in Seattle and at Seattle Children’s Hospital. She had no relevant disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

This small Israeli study is very important. The powerful finding of the study was buttressed by its placebo-controlled design and by its follow-up. The findings need replication in a larger study, but despite the small size of the current study the findings are noteworthy because of the desperate need for a safe and effective intervention to reduce the risk for maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus (CMV) when a woman has a first infection just before conception or early during pregnancy. Several years ago, the Institute of Medicine made prevention of prenatal CMV transmission (by vaccination) a major health priority based on the high estimated burden of congenital CMV infection, Addressing this still unmet need remains an important goal given the substantial disability that congenital CMV causes for thousands of infants born each year.

Janet A. Englund, MD, is a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Washington in Seattle and at Seattle Children’s Hospital. She had no relevant disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

WASHINGTON – Daily treatment with valacyclovir for at least 6 weeks safely cut the cytomegalovirus (CMV) vertical transmission rate from mothers to fetuses in women with a primary CMV infection during the three weeks before conception through their first trimester. That finding emerged from a randomized, controlled, single-center Israeli study with 92 women.

The rate of congenital fetal infection with CMV was 11% among neonates born to 45 women treated with 8 g/day of valacyclovir, compared with a 30% rate among the infants born to 47 women who received placebo, a statistically significant difference, Keren Shahar-Nissan, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. The results also showed that the valacyclovir regimen was well tolerated, with no increase compared with placebo in adverse events and with no need for dosage adjustment regardless of a 16 pill/day regimen to deliver the 8 g/day of valacyclovir or placebo that participants received.

Dr. Shahar-Nissan said that she and her associates felt comfortable administering this amount of valacyclovir to pregnant woman given previous reports of the safety of this dosage for both women and their fetuses. These reports included 20 pregnant women safely treated for 7 weeks with 8 g/day during the late second or early third trimester (BJOG. 2007 Sept;114[9]:1113-21); more than 600 women in a Danish nationwide study treated with any dosage of valacyclovir during preconception, the first trimester, or the second or third trimesters with a prevalence of births defects not significantly different from unexposed pregnancies (JAMA. 2010 Aug 25;304[8]:859-66); and a prospective, open-label study of 8 g/day valacyclovir to treat 43 women carrying CMV-infected fetuses starting at a median 26 weeks gestation and continuing through delivery (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Oct;215[4]:462.e1-462.e10).

The study she ran enrolled women seen at Helen Schneider Hospital for Women in Petah Tikva, Israel, during November 2015-October 2018 who had a serologically-proven primary CMV infection that began at any time from 3 weeks before conception through the first trimester, excluding patients with renal dysfunction, liver disease, bone-marrow suppression, or acyclovir sensitivity. Screening for active CMV infection is common among newly-pregnant Israeli women, usually at the time of their first obstetrical consultation for a suspected pregnancy, noted Dr. Shahar-Nissan, a pediatrician at Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel in Petah Tikva. About a quarter of the enrolled women became infected during the 3 weeks prior to conception, and nearly two-thirds became infected during the first 8 weeks of pregnancy.

The valacyclovir intervention appeared to be effective specifically for preventing vertical transmission of infection acquired early during pregnancy. In this subgroup the transmission rate was 11% with valacyclovir treatment and 48% on placebo. Valacyclovir seemed to have no effect on vertical transmission of infections that began before conception, likely because treatment began too late to prevent transmission.

“I think this study is enough” to convince the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to add this treatment indication to the labeling of valacyclovir, a drug that has been available in generic formulations for many years, Dr. Shahar-Nissan said in an interview. Before approaching the FDA, her first goal is publishing the findings, she added.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

WASHINGTON – Daily treatment with valacyclovir for at least 6 weeks safely cut the cytomegalovirus (CMV) vertical transmission rate from mothers to fetuses in women with a primary CMV infection during the three weeks before conception through their first trimester. That finding emerged from a randomized, controlled, single-center Israeli study with 92 women.

The rate of congenital fetal infection with CMV was 11% among neonates born to 45 women treated with 8 g/day of valacyclovir, compared with a 30% rate among the infants born to 47 women who received placebo, a statistically significant difference, Keren Shahar-Nissan, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. The results also showed that the valacyclovir regimen was well tolerated, with no increase compared with placebo in adverse events and with no need for dosage adjustment regardless of a 16 pill/day regimen to deliver the 8 g/day of valacyclovir or placebo that participants received.

Dr. Shahar-Nissan said that she and her associates felt comfortable administering this amount of valacyclovir to pregnant woman given previous reports of the safety of this dosage for both women and their fetuses. These reports included 20 pregnant women safely treated for 7 weeks with 8 g/day during the late second or early third trimester (BJOG. 2007 Sept;114[9]:1113-21); more than 600 women in a Danish nationwide study treated with any dosage of valacyclovir during preconception, the first trimester, or the second or third trimesters with a prevalence of births defects not significantly different from unexposed pregnancies (JAMA. 2010 Aug 25;304[8]:859-66); and a prospective, open-label study of 8 g/day valacyclovir to treat 43 women carrying CMV-infected fetuses starting at a median 26 weeks gestation and continuing through delivery (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Oct;215[4]:462.e1-462.e10).

The study she ran enrolled women seen at Helen Schneider Hospital for Women in Petah Tikva, Israel, during November 2015-October 2018 who had a serologically-proven primary CMV infection that began at any time from 3 weeks before conception through the first trimester, excluding patients with renal dysfunction, liver disease, bone-marrow suppression, or acyclovir sensitivity. Screening for active CMV infection is common among newly-pregnant Israeli women, usually at the time of their first obstetrical consultation for a suspected pregnancy, noted Dr. Shahar-Nissan, a pediatrician at Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel in Petah Tikva. About a quarter of the enrolled women became infected during the 3 weeks prior to conception, and nearly two-thirds became infected during the first 8 weeks of pregnancy.

The valacyclovir intervention appeared to be effective specifically for preventing vertical transmission of infection acquired early during pregnancy. In this subgroup the transmission rate was 11% with valacyclovir treatment and 48% on placebo. Valacyclovir seemed to have no effect on vertical transmission of infections that began before conception, likely because treatment began too late to prevent transmission.

“I think this study is enough” to convince the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to add this treatment indication to the labeling of valacyclovir, a drug that has been available in generic formulations for many years, Dr. Shahar-Nissan said in an interview. Before approaching the FDA, her first goal is publishing the findings, she added.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2019

New genotype of S. pyrogenes found in rise of scarlet fever in U.K.

A new Streptococcus pyogenes genotype (designated M1UK) emerged in 2014 in England causing an increase in scarlet fever “unprecedented in modern times.” Researchers discovered that this new genotype became dominant during this increased period of scarlet fever. This new genotype was characterized by an increased production of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (SpeA, also known as scarlet fever or erythrogenic toxin A) compared to previous isolates, according to a report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The researchers analyzed changes in S. pyogenes emm1 genotypes sampled from scarlet fever and invasive disease cases in 2014-2016. The emm1 gene encodes the cell surface M virulence protein and is used for serotyping S. pyogenes isolates. Using regional (northwest London) and national (England and Wales) data, they compared genomes of 135 noninvasive and 552 invasive emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 with 2,800 global emm1 sequences.

During the increase in scarlet fever and invasive disease, emm1 S. pyogenes upper respiratory tract isolates increased significantly in northwest London during the March to May periods over 3 years from 5% of isolates in 2014 to 19% isolates in 2015 to 33% isolates in 2016. Similarly, invasive emm1 isolates collected nationally in the same period increased from 31% of isolates in 2015 to 42% in 2016 (P less than .0001). Sequences of emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 showed emergence of a new emm1 lineage (designated M1UK), which could be genotypically distinguished from pandemic emm1 isolates (M1global) by 27 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. In addition, the median SpeA protein concentration was 9 times greater among M1UK isolates than among M1global isolates. By 2016, M1UK expanded nationally to comprise 84% of all emm1 genomes tested. Dataset analysis also identified single M1UK isolates present in Denmark and the United States.

“The expansion of such a lineage within the community reservoir of S. pyogenes might be sufficient to explain England’s recent increase in invasive infection. Further research to assess the likely effects of M1UK on infection transmissibility, treatment response, disease burden, and severity is required, coupled with consideration of public health interventions to limit transmission where appropriate,” Dr. Lynskey and colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Linskey NN et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30446-3.

A new Streptococcus pyogenes genotype (designated M1UK) emerged in 2014 in England causing an increase in scarlet fever “unprecedented in modern times.” Researchers discovered that this new genotype became dominant during this increased period of scarlet fever. This new genotype was characterized by an increased production of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (SpeA, also known as scarlet fever or erythrogenic toxin A) compared to previous isolates, according to a report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The researchers analyzed changes in S. pyogenes emm1 genotypes sampled from scarlet fever and invasive disease cases in 2014-2016. The emm1 gene encodes the cell surface M virulence protein and is used for serotyping S. pyogenes isolates. Using regional (northwest London) and national (England and Wales) data, they compared genomes of 135 noninvasive and 552 invasive emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 with 2,800 global emm1 sequences.

During the increase in scarlet fever and invasive disease, emm1 S. pyogenes upper respiratory tract isolates increased significantly in northwest London during the March to May periods over 3 years from 5% of isolates in 2014 to 19% isolates in 2015 to 33% isolates in 2016. Similarly, invasive emm1 isolates collected nationally in the same period increased from 31% of isolates in 2015 to 42% in 2016 (P less than .0001). Sequences of emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 showed emergence of a new emm1 lineage (designated M1UK), which could be genotypically distinguished from pandemic emm1 isolates (M1global) by 27 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. In addition, the median SpeA protein concentration was 9 times greater among M1UK isolates than among M1global isolates. By 2016, M1UK expanded nationally to comprise 84% of all emm1 genomes tested. Dataset analysis also identified single M1UK isolates present in Denmark and the United States.

“The expansion of such a lineage within the community reservoir of S. pyogenes might be sufficient to explain England’s recent increase in invasive infection. Further research to assess the likely effects of M1UK on infection transmissibility, treatment response, disease burden, and severity is required, coupled with consideration of public health interventions to limit transmission where appropriate,” Dr. Lynskey and colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Linskey NN et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30446-3.

A new Streptococcus pyogenes genotype (designated M1UK) emerged in 2014 in England causing an increase in scarlet fever “unprecedented in modern times.” Researchers discovered that this new genotype became dominant during this increased period of scarlet fever. This new genotype was characterized by an increased production of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (SpeA, also known as scarlet fever or erythrogenic toxin A) compared to previous isolates, according to a report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The researchers analyzed changes in S. pyogenes emm1 genotypes sampled from scarlet fever and invasive disease cases in 2014-2016. The emm1 gene encodes the cell surface M virulence protein and is used for serotyping S. pyogenes isolates. Using regional (northwest London) and national (England and Wales) data, they compared genomes of 135 noninvasive and 552 invasive emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 with 2,800 global emm1 sequences.

During the increase in scarlet fever and invasive disease, emm1 S. pyogenes upper respiratory tract isolates increased significantly in northwest London during the March to May periods over 3 years from 5% of isolates in 2014 to 19% isolates in 2015 to 33% isolates in 2016. Similarly, invasive emm1 isolates collected nationally in the same period increased from 31% of isolates in 2015 to 42% in 2016 (P less than .0001). Sequences of emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 showed emergence of a new emm1 lineage (designated M1UK), which could be genotypically distinguished from pandemic emm1 isolates (M1global) by 27 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. In addition, the median SpeA protein concentration was 9 times greater among M1UK isolates than among M1global isolates. By 2016, M1UK expanded nationally to comprise 84% of all emm1 genomes tested. Dataset analysis also identified single M1UK isolates present in Denmark and the United States.

“The expansion of such a lineage within the community reservoir of S. pyogenes might be sufficient to explain England’s recent increase in invasive infection. Further research to assess the likely effects of M1UK on infection transmissibility, treatment response, disease burden, and severity is required, coupled with consideration of public health interventions to limit transmission where appropriate,” Dr. Lynskey and colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Linskey NN et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30446-3.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: An Streptococcus pyrogenes isolate with increased scarlet fever toxin production has become dominant.

Major finding: By 2016, M1UK expanded nationally to constitute 84% of all emm1 genomes tested.

Study details: Genomic comparison of 135 noninvasive and 552 invasive emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 with 2,800 global emm1 sequences.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Source: Linskey NN et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30446-3.

Post-Ebola mortality five times higher than general population

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Survivors of the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa had lingering health effects of the disease. These patients had a much greater mortality in the first year after discharge, compared with the general population. Among those survivors who died, the majority appear to have expired because of renal failure, according to the results of an assessment the by the Guinean national survivors’ monitoring program.

The Surveillance Active en Ceinture obtained data on 1,130 (89%) of survivors of Ebola virus disease who were discharged from Ebola treatment units in Guinea. Compared with the general Guinean population, survivors of Ebola virus showed a five times increased risk of mortality within a year of follow-up after discharge, according to a survey of patients’ medical records and patients’ relatives, reported researchers Mory Keita, MD, and colleagues.

After 1 year, the difference in mortality between Ebola survivors and the general population had disappeared, according to the study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 59 deaths were reported among the discharged survivors available for follow-up. Renal failure was the assumed cause in 37 (63%) of these patients based on a description of reported anuria. The exact date of death was unknown for 43 of the 59 deaths. Of the 16 initial survivors for whom an exact date of death was available, 5 died within a month of discharge from Ebola treatment units, an additional 3 died within 3 months of discharge, 4 died 3-12 months after discharge, and 4 died more than a year after discharge (up to 21 months).

Age and area of residence (urban vs. nonurban area) were independently and significantly associated with mortality, with patients of older age (55 years or greater) and those from nonurban areas being at greater risk. Patient sex was not associated with survival.

Those survivors who were hospitalized for 12 days or more had more than double the risk of death than did those hospitalized less than 12 days, which was a statistically significant association.

“Survivors’ monitoring programs should be strengthened and should not focus exclusively on testing of bodily fluids,” the authors advised. “Furthermore, our study provides preliminary evidence that survivors hospitalized for longer than 12 days with Ebola virus disease could be at particularly high risk of mortality and should be specifically targeted, and perhaps also evidence that renal function should be monitored,” Dr. Keita and colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts

SOURCE: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Renal failure was the assumed cause of death in 63% of the survivors based on reported anuria.

Major finding:

Study details: A postdischarge survey of 1,130 (89%) of the Ebola survivors and their relations in Guinea.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the World Health Organization, International Medical Corps, and the Guinean Red Cross. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Keita M et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Sept 4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30313-5.

Impact of climate change on mortality underlined by global study

Regardless of where people live in the world, air pollution is linked to increased rates of cardiovascular disease, respiratory problems, and all-cause mortality, according to one of the largest studies ever to assess the effects of inhalable particulate matter (PM), published Aug. 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“These data reinforce the evidence of a link between mortality and PM concentration established in regional and local studies,” reported Cong Liu of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China, and an international team of researchers.

“Many people are experiencing worse allergy and asthma symptoms in the setting of increased heat and worse air quality,” Caren G. Solomon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “It is often not appreciated that these are complications of climate change.”

Other such complications include heat-related illnesses and severe weather events, as well as the less visible manifestations, such as shifts in the epidemiology of vector-borne infectious disease, Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote in an editorial accompanying Mr. Liu’s study.

“The stark reality is that high levels of greenhouse gases caused by the combustion of fossil fuels – and the resulting rise in temperature and sea levels and intensification of extreme weather – are having profound consequences for human health and health systems,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote (N Engl J Med. 2019;381:773-4.).

In the new air pollution study, Mr. Liu and colleagues analyzed 59.6 million deaths from 652 cities across 24 countries, “thereby greatly increasing the generalizability of the association and decreasing the likelihood that the reported associations are subject to confounding bias,” wrote John R. Balmes, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of California, Berkeley, in an editorial about the study (N Engl J Med. 2019;381:774-6).

The researchers compared air pollution data from 1986-2015 from the Multi-City Multi-Country (MCC) Collaborative Research Network to mortality data reported from individual countries. They assessed PM with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 mcg or less (PM10; n = 598 cities) and PM with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 mcg or less (PM2.5; n=499 cities).

Mr. Liu’s team used a time-series analysis – a standard upon which the majority of air pollution research relies. These studies “include daily measures of health events (e.g., daily mortality), regressed against concentrations of PM (e.g., 24-hour average PM2.5) and weather variables (e.g., daily average temperature) for a given geographic area,” Dr. Balmes wrote. “The population serves as its own control, and confounding by population characteristics is negligible because these are stable over short time frames.”

The researchers found a 0.44% increase in daily all-cause mortality for each 10-mcg/m3 increase in the 2-day moving average (current and previous day) of PM10. The same increase was linked to a 0.36% increase in daily cardiovascular mortality and a 0.47% increase in daily respiratory mortality. Similarly, a 10-mcg/m3 increase in the PM2.5 average was linked to 0.68% increase in all-cause mortality, a 0.55% increase in cardiovascular mortality, and 0.74% increase in respiratory mortality.

Locations with higher annual mean temperatures showed stronger associations, and all these associations remained statistically significant after the researchers adjusted for gaseous pollutants.

Although the majority of countries and cities included in the study came from the northern hemisphere, the researchers noted that the magnitude of effect they found, particularly for PM10 concentrations, matched up with that seen in previous studies of multiple cities or countries.

Still, they found “significant evidence of spatial heterogeneity in the associations between PM concentration and daily mortality across countries and regions.” Among the factors that could contribute to those variations are “different PM components, long-term air pollution levels, population susceptibility, and different lengths of study periods,” they speculated.

What makes this study remarkable – despite decades of previous similar studies – is its size and the implications of a curvilinear shape in its concentration-response relation, according to Dr. Balmes.

“The current study of PM data from many regions around the world provides the strongest evidence to date that higher levels of exposure may be associated with a lower per-unit risk,” Dr. Balmes wrote. “Regions that have lower exposures had a higher per-unit risk. This finding has profound policy implications, especially given that no threshold of effect was found. Even high-income countries, such as the United States, with relatively good air quality could still see public health benefits from further reduction of ambient PM concentrations.”

The policy implications, however, extend well beyond clean air regulations because the findings represent just one aspect of climate change’s negative effects on health, which are “frighteningly broad,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote.

“As climate change continues to alter disease patterns and disrupt health systems, its effects on human health will become harder to ignore,” they wrote. “We, as a medical community, have the responsibility and the opportunity to mobilize the urgent, large-scale climate action required to protect health – as well as the ingenuity to develop novel and bold interventions to avert the most catastrophic outcomes.”

The new research and associated commentary marked the introduction of a new NEJM topic on climate change effects on health and health systems.

SOURCE: Liu C et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:705-15.

This article was updated 8/22/19.

The negative effects of climate change on global public health are already playing out around us, but scientific research shows that they will only get worse – unless we begin addressing the issue in earnest now.

At the macro level nationally, effective policy is actually being stripped away right now. “[While] scientists tell us we have little time to wait if we hope to avoid the most devastating effects of climate change, leaders in Washington, D.C., are attacking science and rolling back Obama-era rules from the Environmental Protection Agency,” such as working to weaken vehicle fuel-efficiency standards, relaxing methane emissions rules, ending mercury emissions regulation and taking other actions that will only increase air pollution.

“If these EPA rollbacks are successful, they will diminish our ability to mitigate health effects and diseases related to the burning of fossil fuels and the immense toll they take on our families. ... If we stop supporting and listening to the best available science, if we allow more pollution to be emitted, and if we start limiting the EPA’s ability to monitor and enforce pollution standards, then we put at risk everyone’s health – and especially the health and future of our children.”

Engaging in advocacy and communicating to our representatives that we want stronger regulations is one way people can personally take action, but we can take immediate actions in our everyday lives too. Rather than dwelling on the despair of helplessness and hopelessness that grips many people when it comes to climate change, this moment can be reframed as an opportunity for people to make decisions that immediately begin improving their health — and also happen to be good for the planet.

“To me, the most urgent challenge when it comes to health and climate change is the reality that, when climate change comes up, in the U.S. audience, the first thing that should come into people’s minds is that we need to do this now because we need to protect our children’s health. ... Too many people either don’t get that it matters to health at all, or they don’t get that the actions we need to take are exactly what we need to do to address the health problems that have been nearly impossible to deal with.”

For example, problems like rising child obesity and type 2 diabetes rates have plagued public health, yet people can make changes that reduce obesity and diabetes risk that also decrease their carbon footprints, he said. “One of the best ways to deal with obesity is to eat more plants, and it turns out that’s really good for the climate” Additionally, getting people out of cars and walking and cycling can reduce individuals’ risk of diabetes – while simultaneously decreasing air pollution. “We need to be doing these things regardless of climate change, and if parents and children understood that the pathway to a healthier future was through tackling climate change, we would see a transformation.”

The value of local policy actions should be emphasized, such as ones that call for a reduction in a city’s use of concrete – which increases localized heat – and constructing more efficient buildings. Healthcare providers have an opportunity – and responsibility – not only to recognize this reality but to help their patients recognize it too.

“We can also use our roles as trusted advisers to inform and motivate actions that are increasingly necessary to protect the health of the communities we serve.” They also need to be vigilant about conditions that will worsen as the planet heats up: For example, medications such as diuretics carry more risks in higher temperatures, and patients taking them need to know that.

The need to address climate change matters because we face the challenge of protecting the world’s most vulnerable people.

“One of the great things about climate change is if it causes us to rethink about what we need to do to protect the future, it’s going to help our health today. ... If we can use that as the motivator, then maybe we can stop arguing and start thinking about climate as a positive issue, as a more personal issue we can all participate in and be willing to invest in.”

Gina McCarthy, MS, was administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency during 2013-2017, and Aaron Bernstein, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital. Both are from the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment (Harvard C-CHANGE) at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston. Their comments came from their perspective (N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1909643) published in NEJM along with this article and editorial and a phone interview. They reported not having any disclosures.

The negative effects of climate change on global public health are already playing out around us, but scientific research shows that they will only get worse – unless we begin addressing the issue in earnest now.

At the macro level nationally, effective policy is actually being stripped away right now. “[While] scientists tell us we have little time to wait if we hope to avoid the most devastating effects of climate change, leaders in Washington, D.C., are attacking science and rolling back Obama-era rules from the Environmental Protection Agency,” such as working to weaken vehicle fuel-efficiency standards, relaxing methane emissions rules, ending mercury emissions regulation and taking other actions that will only increase air pollution.

“If these EPA rollbacks are successful, they will diminish our ability to mitigate health effects and diseases related to the burning of fossil fuels and the immense toll they take on our families. ... If we stop supporting and listening to the best available science, if we allow more pollution to be emitted, and if we start limiting the EPA’s ability to monitor and enforce pollution standards, then we put at risk everyone’s health – and especially the health and future of our children.”

Engaging in advocacy and communicating to our representatives that we want stronger regulations is one way people can personally take action, but we can take immediate actions in our everyday lives too. Rather than dwelling on the despair of helplessness and hopelessness that grips many people when it comes to climate change, this moment can be reframed as an opportunity for people to make decisions that immediately begin improving their health — and also happen to be good for the planet.

“To me, the most urgent challenge when it comes to health and climate change is the reality that, when climate change comes up, in the U.S. audience, the first thing that should come into people’s minds is that we need to do this now because we need to protect our children’s health. ... Too many people either don’t get that it matters to health at all, or they don’t get that the actions we need to take are exactly what we need to do to address the health problems that have been nearly impossible to deal with.”

For example, problems like rising child obesity and type 2 diabetes rates have plagued public health, yet people can make changes that reduce obesity and diabetes risk that also decrease their carbon footprints, he said. “One of the best ways to deal with obesity is to eat more plants, and it turns out that’s really good for the climate” Additionally, getting people out of cars and walking and cycling can reduce individuals’ risk of diabetes – while simultaneously decreasing air pollution. “We need to be doing these things regardless of climate change, and if parents and children understood that the pathway to a healthier future was through tackling climate change, we would see a transformation.”

The value of local policy actions should be emphasized, such as ones that call for a reduction in a city’s use of concrete – which increases localized heat – and constructing more efficient buildings. Healthcare providers have an opportunity – and responsibility – not only to recognize this reality but to help their patients recognize it too.

“We can also use our roles as trusted advisers to inform and motivate actions that are increasingly necessary to protect the health of the communities we serve.” They also need to be vigilant about conditions that will worsen as the planet heats up: For example, medications such as diuretics carry more risks in higher temperatures, and patients taking them need to know that.

The need to address climate change matters because we face the challenge of protecting the world’s most vulnerable people.

“One of the great things about climate change is if it causes us to rethink about what we need to do to protect the future, it’s going to help our health today. ... If we can use that as the motivator, then maybe we can stop arguing and start thinking about climate as a positive issue, as a more personal issue we can all participate in and be willing to invest in.”

Gina McCarthy, MS, was administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency during 2013-2017, and Aaron Bernstein, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital. Both are from the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment (Harvard C-CHANGE) at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston. Their comments came from their perspective (N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1909643) published in NEJM along with this article and editorial and a phone interview. They reported not having any disclosures.

The negative effects of climate change on global public health are already playing out around us, but scientific research shows that they will only get worse – unless we begin addressing the issue in earnest now.

At the macro level nationally, effective policy is actually being stripped away right now. “[While] scientists tell us we have little time to wait if we hope to avoid the most devastating effects of climate change, leaders in Washington, D.C., are attacking science and rolling back Obama-era rules from the Environmental Protection Agency,” such as working to weaken vehicle fuel-efficiency standards, relaxing methane emissions rules, ending mercury emissions regulation and taking other actions that will only increase air pollution.

“If these EPA rollbacks are successful, they will diminish our ability to mitigate health effects and diseases related to the burning of fossil fuels and the immense toll they take on our families. ... If we stop supporting and listening to the best available science, if we allow more pollution to be emitted, and if we start limiting the EPA’s ability to monitor and enforce pollution standards, then we put at risk everyone’s health – and especially the health and future of our children.”

Engaging in advocacy and communicating to our representatives that we want stronger regulations is one way people can personally take action, but we can take immediate actions in our everyday lives too. Rather than dwelling on the despair of helplessness and hopelessness that grips many people when it comes to climate change, this moment can be reframed as an opportunity for people to make decisions that immediately begin improving their health — and also happen to be good for the planet.

“To me, the most urgent challenge when it comes to health and climate change is the reality that, when climate change comes up, in the U.S. audience, the first thing that should come into people’s minds is that we need to do this now because we need to protect our children’s health. ... Too many people either don’t get that it matters to health at all, or they don’t get that the actions we need to take are exactly what we need to do to address the health problems that have been nearly impossible to deal with.”

For example, problems like rising child obesity and type 2 diabetes rates have plagued public health, yet people can make changes that reduce obesity and diabetes risk that also decrease their carbon footprints, he said. “One of the best ways to deal with obesity is to eat more plants, and it turns out that’s really good for the climate” Additionally, getting people out of cars and walking and cycling can reduce individuals’ risk of diabetes – while simultaneously decreasing air pollution. “We need to be doing these things regardless of climate change, and if parents and children understood that the pathway to a healthier future was through tackling climate change, we would see a transformation.”

The value of local policy actions should be emphasized, such as ones that call for a reduction in a city’s use of concrete – which increases localized heat – and constructing more efficient buildings. Healthcare providers have an opportunity – and responsibility – not only to recognize this reality but to help their patients recognize it too.

“We can also use our roles as trusted advisers to inform and motivate actions that are increasingly necessary to protect the health of the communities we serve.” They also need to be vigilant about conditions that will worsen as the planet heats up: For example, medications such as diuretics carry more risks in higher temperatures, and patients taking them need to know that.

The need to address climate change matters because we face the challenge of protecting the world’s most vulnerable people.

“One of the great things about climate change is if it causes us to rethink about what we need to do to protect the future, it’s going to help our health today. ... If we can use that as the motivator, then maybe we can stop arguing and start thinking about climate as a positive issue, as a more personal issue we can all participate in and be willing to invest in.”

Gina McCarthy, MS, was administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency during 2013-2017, and Aaron Bernstein, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital. Both are from the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment (Harvard C-CHANGE) at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston. Their comments came from their perspective (N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1909643) published in NEJM along with this article and editorial and a phone interview. They reported not having any disclosures.

Regardless of where people live in the world, air pollution is linked to increased rates of cardiovascular disease, respiratory problems, and all-cause mortality, according to one of the largest studies ever to assess the effects of inhalable particulate matter (PM), published Aug. 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“These data reinforce the evidence of a link between mortality and PM concentration established in regional and local studies,” reported Cong Liu of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China, and an international team of researchers.

“Many people are experiencing worse allergy and asthma symptoms in the setting of increased heat and worse air quality,” Caren G. Solomon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “It is often not appreciated that these are complications of climate change.”

Other such complications include heat-related illnesses and severe weather events, as well as the less visible manifestations, such as shifts in the epidemiology of vector-borne infectious disease, Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote in an editorial accompanying Mr. Liu’s study.

“The stark reality is that high levels of greenhouse gases caused by the combustion of fossil fuels – and the resulting rise in temperature and sea levels and intensification of extreme weather – are having profound consequences for human health and health systems,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote (N Engl J Med. 2019;381:773-4.).

In the new air pollution study, Mr. Liu and colleagues analyzed 59.6 million deaths from 652 cities across 24 countries, “thereby greatly increasing the generalizability of the association and decreasing the likelihood that the reported associations are subject to confounding bias,” wrote John R. Balmes, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of California, Berkeley, in an editorial about the study (N Engl J Med. 2019;381:774-6).

The researchers compared air pollution data from 1986-2015 from the Multi-City Multi-Country (MCC) Collaborative Research Network to mortality data reported from individual countries. They assessed PM with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 mcg or less (PM10; n = 598 cities) and PM with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 mcg or less (PM2.5; n=499 cities).

Mr. Liu’s team used a time-series analysis – a standard upon which the majority of air pollution research relies. These studies “include daily measures of health events (e.g., daily mortality), regressed against concentrations of PM (e.g., 24-hour average PM2.5) and weather variables (e.g., daily average temperature) for a given geographic area,” Dr. Balmes wrote. “The population serves as its own control, and confounding by population characteristics is negligible because these are stable over short time frames.”

The researchers found a 0.44% increase in daily all-cause mortality for each 10-mcg/m3 increase in the 2-day moving average (current and previous day) of PM10. The same increase was linked to a 0.36% increase in daily cardiovascular mortality and a 0.47% increase in daily respiratory mortality. Similarly, a 10-mcg/m3 increase in the PM2.5 average was linked to 0.68% increase in all-cause mortality, a 0.55% increase in cardiovascular mortality, and 0.74% increase in respiratory mortality.

Locations with higher annual mean temperatures showed stronger associations, and all these associations remained statistically significant after the researchers adjusted for gaseous pollutants.

Although the majority of countries and cities included in the study came from the northern hemisphere, the researchers noted that the magnitude of effect they found, particularly for PM10 concentrations, matched up with that seen in previous studies of multiple cities or countries.

Still, they found “significant evidence of spatial heterogeneity in the associations between PM concentration and daily mortality across countries and regions.” Among the factors that could contribute to those variations are “different PM components, long-term air pollution levels, population susceptibility, and different lengths of study periods,” they speculated.

What makes this study remarkable – despite decades of previous similar studies – is its size and the implications of a curvilinear shape in its concentration-response relation, according to Dr. Balmes.

“The current study of PM data from many regions around the world provides the strongest evidence to date that higher levels of exposure may be associated with a lower per-unit risk,” Dr. Balmes wrote. “Regions that have lower exposures had a higher per-unit risk. This finding has profound policy implications, especially given that no threshold of effect was found. Even high-income countries, such as the United States, with relatively good air quality could still see public health benefits from further reduction of ambient PM concentrations.”

The policy implications, however, extend well beyond clean air regulations because the findings represent just one aspect of climate change’s negative effects on health, which are “frighteningly broad,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote.

“As climate change continues to alter disease patterns and disrupt health systems, its effects on human health will become harder to ignore,” they wrote. “We, as a medical community, have the responsibility and the opportunity to mobilize the urgent, large-scale climate action required to protect health – as well as the ingenuity to develop novel and bold interventions to avert the most catastrophic outcomes.”

The new research and associated commentary marked the introduction of a new NEJM topic on climate change effects on health and health systems.

SOURCE: Liu C et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:705-15.

This article was updated 8/22/19.

Regardless of where people live in the world, air pollution is linked to increased rates of cardiovascular disease, respiratory problems, and all-cause mortality, according to one of the largest studies ever to assess the effects of inhalable particulate matter (PM), published Aug. 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“These data reinforce the evidence of a link between mortality and PM concentration established in regional and local studies,” reported Cong Liu of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China, and an international team of researchers.

“Many people are experiencing worse allergy and asthma symptoms in the setting of increased heat and worse air quality,” Caren G. Solomon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “It is often not appreciated that these are complications of climate change.”

Other such complications include heat-related illnesses and severe weather events, as well as the less visible manifestations, such as shifts in the epidemiology of vector-borne infectious disease, Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote in an editorial accompanying Mr. Liu’s study.

“The stark reality is that high levels of greenhouse gases caused by the combustion of fossil fuels – and the resulting rise in temperature and sea levels and intensification of extreme weather – are having profound consequences for human health and health systems,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote (N Engl J Med. 2019;381:773-4.).

In the new air pollution study, Mr. Liu and colleagues analyzed 59.6 million deaths from 652 cities across 24 countries, “thereby greatly increasing the generalizability of the association and decreasing the likelihood that the reported associations are subject to confounding bias,” wrote John R. Balmes, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of California, Berkeley, in an editorial about the study (N Engl J Med. 2019;381:774-6).

The researchers compared air pollution data from 1986-2015 from the Multi-City Multi-Country (MCC) Collaborative Research Network to mortality data reported from individual countries. They assessed PM with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 mcg or less (PM10; n = 598 cities) and PM with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 mcg or less (PM2.5; n=499 cities).

Mr. Liu’s team used a time-series analysis – a standard upon which the majority of air pollution research relies. These studies “include daily measures of health events (e.g., daily mortality), regressed against concentrations of PM (e.g., 24-hour average PM2.5) and weather variables (e.g., daily average temperature) for a given geographic area,” Dr. Balmes wrote. “The population serves as its own control, and confounding by population characteristics is negligible because these are stable over short time frames.”

The researchers found a 0.44% increase in daily all-cause mortality for each 10-mcg/m3 increase in the 2-day moving average (current and previous day) of PM10. The same increase was linked to a 0.36% increase in daily cardiovascular mortality and a 0.47% increase in daily respiratory mortality. Similarly, a 10-mcg/m3 increase in the PM2.5 average was linked to 0.68% increase in all-cause mortality, a 0.55% increase in cardiovascular mortality, and 0.74% increase in respiratory mortality.

Locations with higher annual mean temperatures showed stronger associations, and all these associations remained statistically significant after the researchers adjusted for gaseous pollutants.

Although the majority of countries and cities included in the study came from the northern hemisphere, the researchers noted that the magnitude of effect they found, particularly for PM10 concentrations, matched up with that seen in previous studies of multiple cities or countries.

Still, they found “significant evidence of spatial heterogeneity in the associations between PM concentration and daily mortality across countries and regions.” Among the factors that could contribute to those variations are “different PM components, long-term air pollution levels, population susceptibility, and different lengths of study periods,” they speculated.

What makes this study remarkable – despite decades of previous similar studies – is its size and the implications of a curvilinear shape in its concentration-response relation, according to Dr. Balmes.

“The current study of PM data from many regions around the world provides the strongest evidence to date that higher levels of exposure may be associated with a lower per-unit risk,” Dr. Balmes wrote. “Regions that have lower exposures had a higher per-unit risk. This finding has profound policy implications, especially given that no threshold of effect was found. Even high-income countries, such as the United States, with relatively good air quality could still see public health benefits from further reduction of ambient PM concentrations.”

The policy implications, however, extend well beyond clean air regulations because the findings represent just one aspect of climate change’s negative effects on health, which are “frighteningly broad,” Dr. Solomon and colleagues wrote.

“As climate change continues to alter disease patterns and disrupt health systems, its effects on human health will become harder to ignore,” they wrote. “We, as a medical community, have the responsibility and the opportunity to mobilize the urgent, large-scale climate action required to protect health – as well as the ingenuity to develop novel and bold interventions to avert the most catastrophic outcomes.”

The new research and associated commentary marked the introduction of a new NEJM topic on climate change effects on health and health systems.

SOURCE: Liu C et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:705-15.

This article was updated 8/22/19.

FROM NEJM

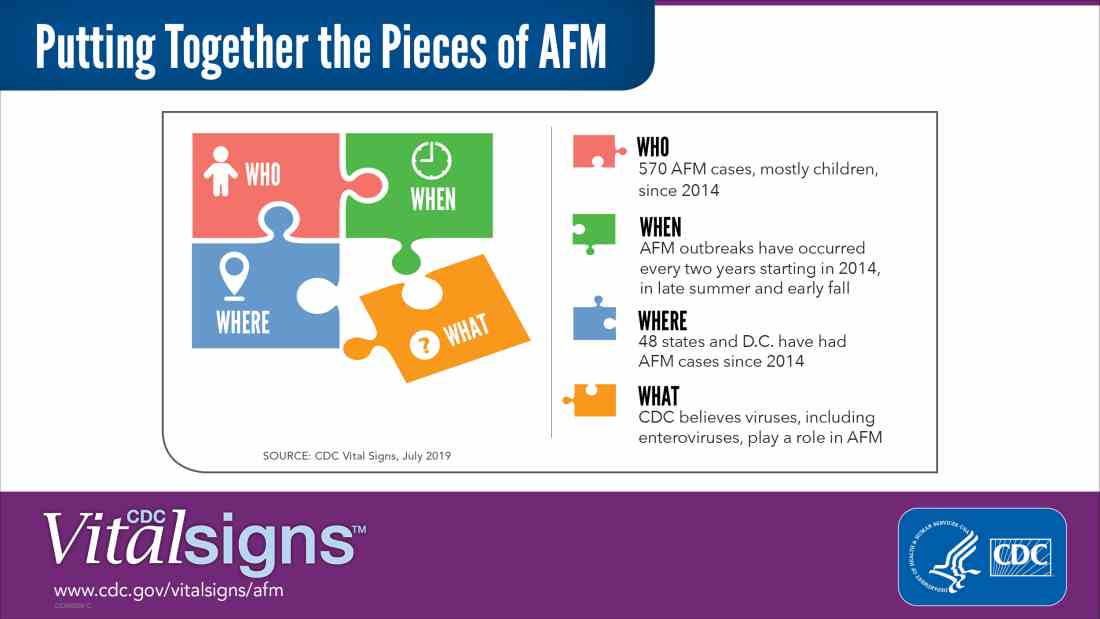

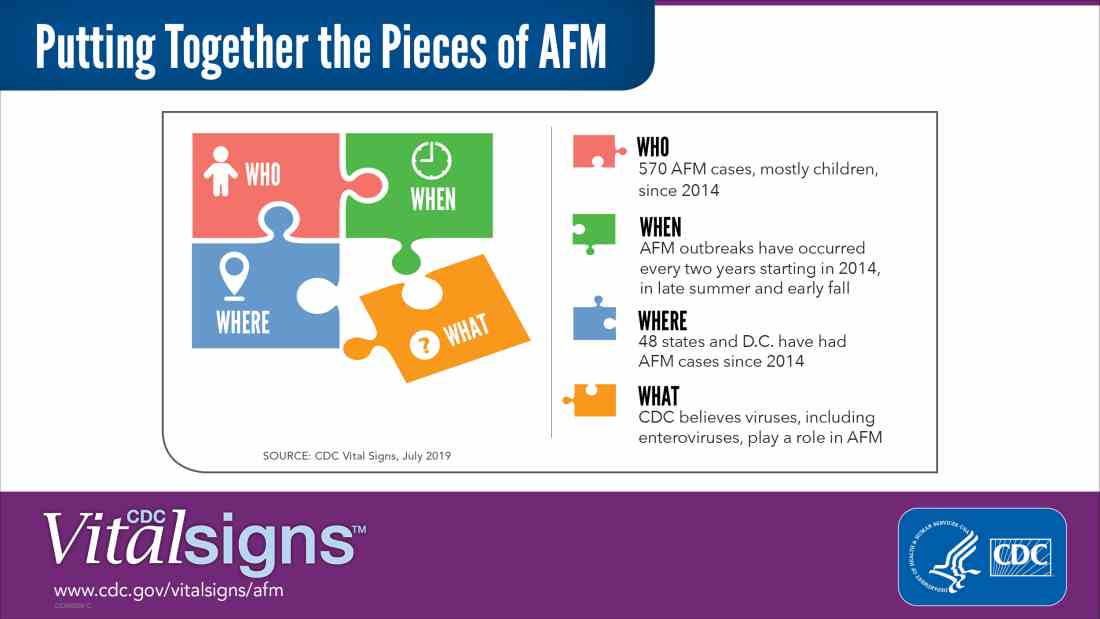

Possible role of enterovirus infection in acute flaccid myelitis cases detected

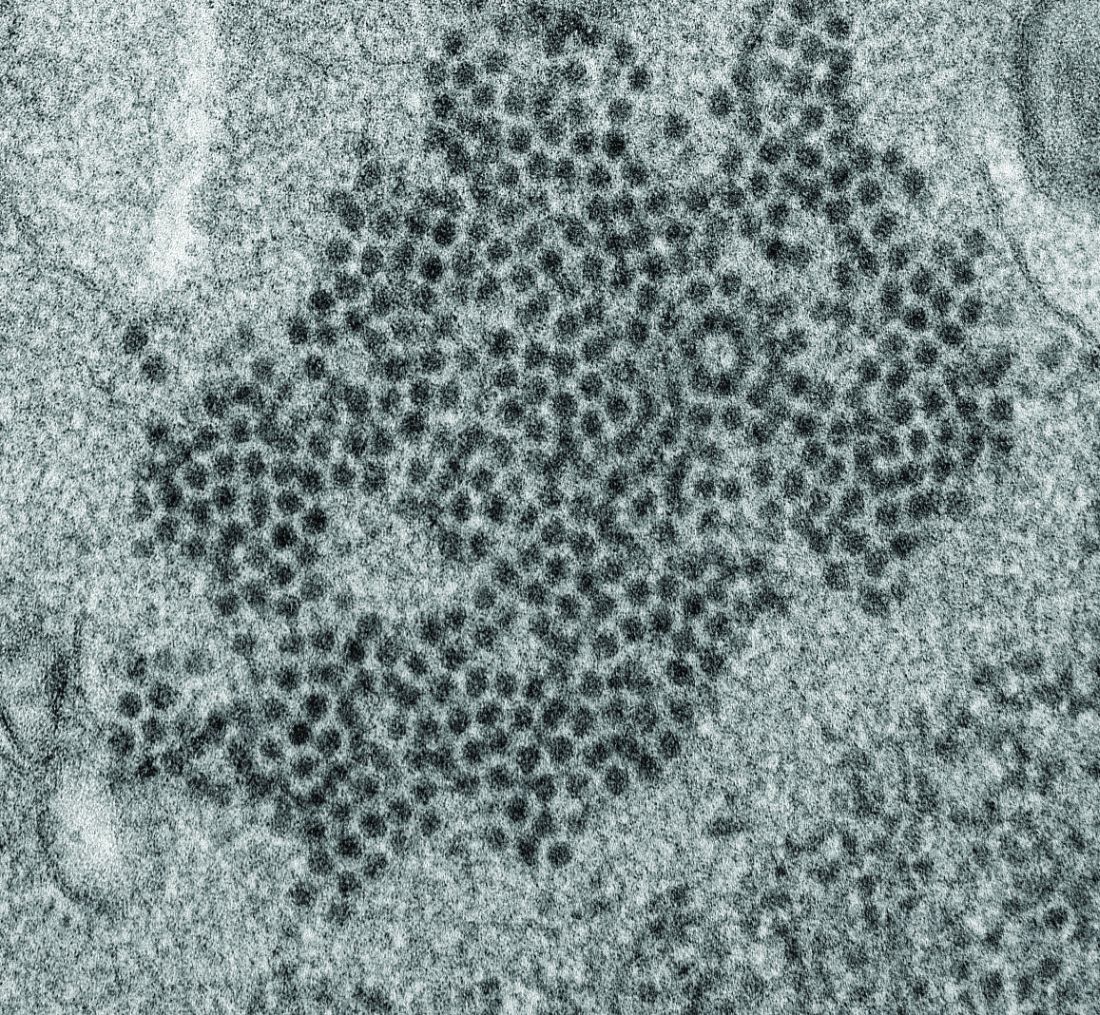

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

FROM MBIO

Key clinical point:

Major finding: EV peptide antibodies were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), significantly higher than in controls.

Study details: A peptide microarray analysis was performed on CSF and sera from 14 AFM patients, as well as three control groups of 5 pediatric and adult patients with a non-AFM CNS diseases, 10 children with Kawasaki disease, and 10 adult patients with non-AFM CNS diseases.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

Favorable Ebola results lead to drug trial termination, new focus

An investigational agent known as REGN-EB3 has met an early stopping criterion in the protocol of an Ebola therapeutics trial, according to a National Institutes of Health media advisory.

Preliminary results in 499 study participants showed that individuals receiving either of two treatments, REGN-EB3 or mAb114, had a greater chance of survival, compared with participants in the other two study arms.

The randomized, controlled Pamoja Tulinde Maisha (PALM) study, which began Nov. 20, 2018, was designed to evaluate four investigational agents (ZMapp, remdesivir, mAb114, and REGN-EB3) for the treatment of patients with Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as part of the emergency response to an ongoing outbreak in the North Kivu and Ituri provinces.

As of Aug. 9, 2019, the trial had enrolled 681 patients at four Ebola treatment centers in live outbreak regions of the DRC, with the goal of enrolling 725 patients in total.

The trial investigators and study cosponsors accepted the recommendation for early termination, and staff at the trial sites in the DRC were promptly informed, according to the media advisory. Additional patient randomizations in the now-revised trial will be limited to treatment either with REGN-EB3 or mAb114. Patients randomized to the ZMapp or remdesivir arms in the last 10 days of the original trial will be given the option, at the discretion of their treating physician, to receive either of the two more effective treatments, according to the NIH.

“While the final analysis of the data can occur only after all the data are generated and collected (likely late September/early October 2019), the DSMB [Data and Safety Monitoring Board] and the study leadership felt the preliminary analysis of the existing data was compelling enough to recommend and implement these changes in the trial immediately. The complete results will be submitted for publication in the peer-reviewed medical literature as soon as possible,” the NIH stated.

The study is cosponsored and funded by the NIH, carried out by an international research consortium coordinated by the World Health Organization, and supported by four pharmaceutical companies (MappBio, Gilead, Regeneron, and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics).

An investigational agent known as REGN-EB3 has met an early stopping criterion in the protocol of an Ebola therapeutics trial, according to a National Institutes of Health media advisory.

Preliminary results in 499 study participants showed that individuals receiving either of two treatments, REGN-EB3 or mAb114, had a greater chance of survival, compared with participants in the other two study arms.

The randomized, controlled Pamoja Tulinde Maisha (PALM) study, which began Nov. 20, 2018, was designed to evaluate four investigational agents (ZMapp, remdesivir, mAb114, and REGN-EB3) for the treatment of patients with Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as part of the emergency response to an ongoing outbreak in the North Kivu and Ituri provinces.

As of Aug. 9, 2019, the trial had enrolled 681 patients at four Ebola treatment centers in live outbreak regions of the DRC, with the goal of enrolling 725 patients in total.

The trial investigators and study cosponsors accepted the recommendation for early termination, and staff at the trial sites in the DRC were promptly informed, according to the media advisory. Additional patient randomizations in the now-revised trial will be limited to treatment either with REGN-EB3 or mAb114. Patients randomized to the ZMapp or remdesivir arms in the last 10 days of the original trial will be given the option, at the discretion of their treating physician, to receive either of the two more effective treatments, according to the NIH.

“While the final analysis of the data can occur only after all the data are generated and collected (likely late September/early October 2019), the DSMB [Data and Safety Monitoring Board] and the study leadership felt the preliminary analysis of the existing data was compelling enough to recommend and implement these changes in the trial immediately. The complete results will be submitted for publication in the peer-reviewed medical literature as soon as possible,” the NIH stated.

The study is cosponsored and funded by the NIH, carried out by an international research consortium coordinated by the World Health Organization, and supported by four pharmaceutical companies (MappBio, Gilead, Regeneron, and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics).

An investigational agent known as REGN-EB3 has met an early stopping criterion in the protocol of an Ebola therapeutics trial, according to a National Institutes of Health media advisory.

Preliminary results in 499 study participants showed that individuals receiving either of two treatments, REGN-EB3 or mAb114, had a greater chance of survival, compared with participants in the other two study arms.

The randomized, controlled Pamoja Tulinde Maisha (PALM) study, which began Nov. 20, 2018, was designed to evaluate four investigational agents (ZMapp, remdesivir, mAb114, and REGN-EB3) for the treatment of patients with Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as part of the emergency response to an ongoing outbreak in the North Kivu and Ituri provinces.

As of Aug. 9, 2019, the trial had enrolled 681 patients at four Ebola treatment centers in live outbreak regions of the DRC, with the goal of enrolling 725 patients in total.

The trial investigators and study cosponsors accepted the recommendation for early termination, and staff at the trial sites in the DRC were promptly informed, according to the media advisory. Additional patient randomizations in the now-revised trial will be limited to treatment either with REGN-EB3 or mAb114. Patients randomized to the ZMapp or remdesivir arms in the last 10 days of the original trial will be given the option, at the discretion of their treating physician, to receive either of the two more effective treatments, according to the NIH.

“While the final analysis of the data can occur only after all the data are generated and collected (likely late September/early October 2019), the DSMB [Data and Safety Monitoring Board] and the study leadership felt the preliminary analysis of the existing data was compelling enough to recommend and implement these changes in the trial immediately. The complete results will be submitted for publication in the peer-reviewed medical literature as soon as possible,” the NIH stated.

The study is cosponsored and funded by the NIH, carried out by an international research consortium coordinated by the World Health Organization, and supported by four pharmaceutical companies (MappBio, Gilead, Regeneron, and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics).

DRC Ebola epidemic continues unabated despite international response

, “currently the outbreak continues at the same pace, so we don’t see evidence of slowing,” according to Henry Walke, MD, director of the Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections and Incident Manager, 2018 CDC Ebola Response, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.