User login

The role of repeat uterine curettage in postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

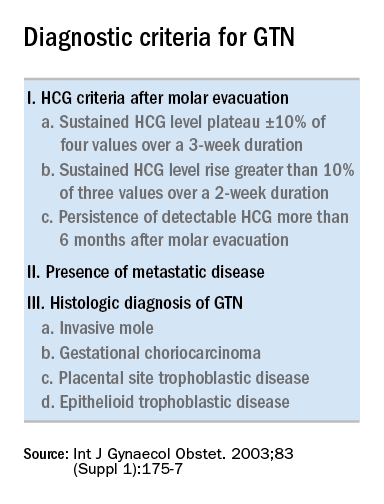

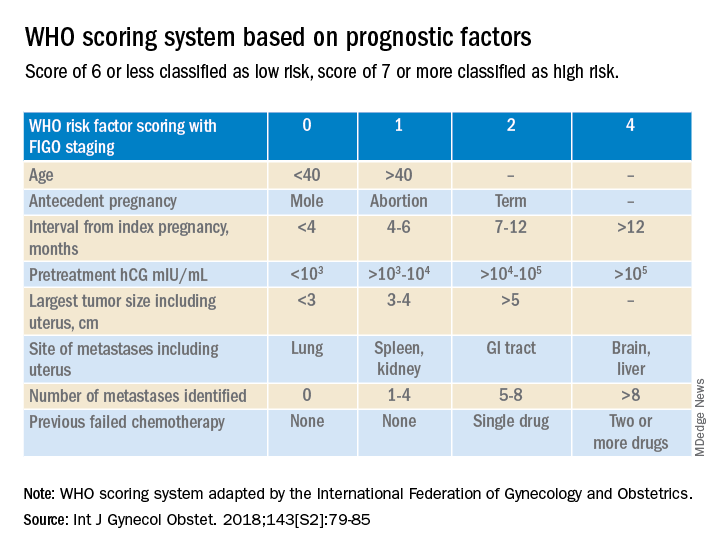

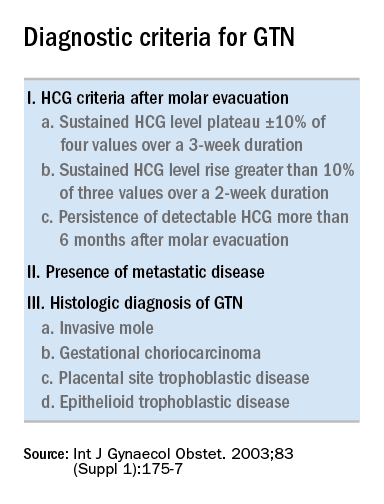

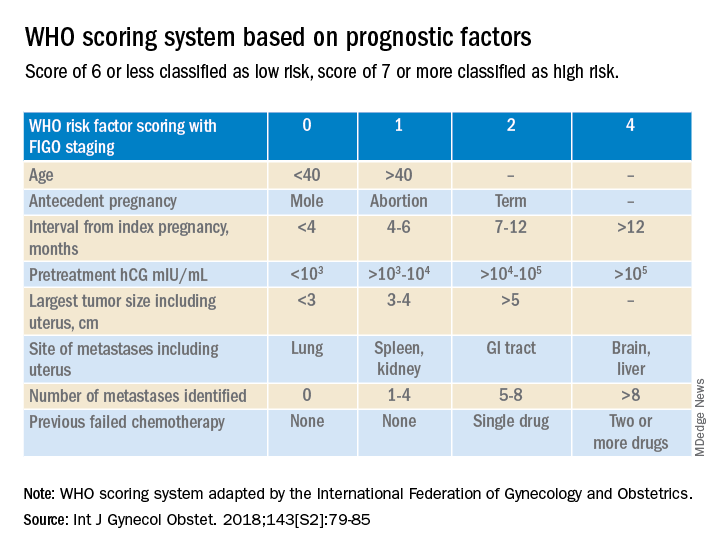

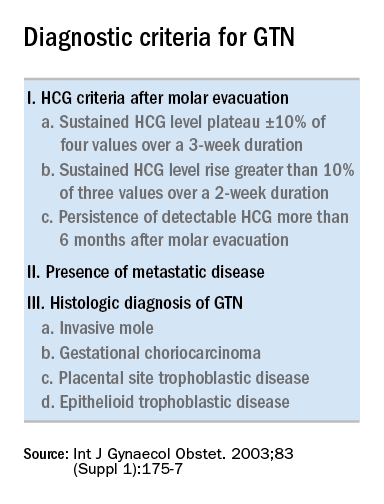

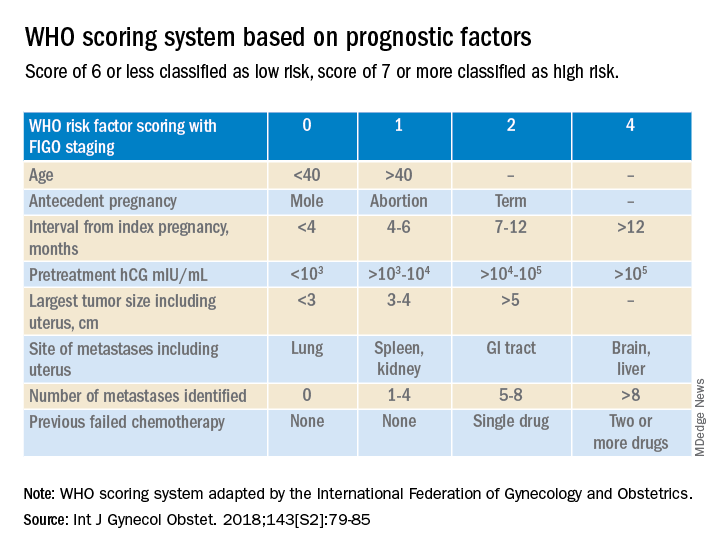

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

Trophoblastic tissue is responsible for formation of the placenta during pregnancy. Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), a group comprising benign (hydatidiform moles) and malignant tumors, occurs when gestational trophoblastic tissue behaves in an abnormal manner. Hydatidiform moles, which are thought to be caused by errors in fertilization, occur in approximately 1 in 1,200 pregnancies in the United States. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) refers to the subgroup of these trophoblastic or placental tumors with malignant behavior and includes postmolar GTN, invasive mole, gestational choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor (PSTT), and epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Postmolar GTN arises after evacuation of a molar pregnancy and is most frequently diagnosed by a plateau or increase in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).1 The risk of postmolar GTN is much higher after a complete mole (7%-30%) compared with a partial mole (2.5%-7.5%).2 Once postmolar GTN is diagnosed, a World Health Organization score is assigned to determine if patients have low- or high-risk disease.3 The primary treatment for most GTN is chemotherapy. A patient’s WHO score helps determine whether they would benefit from single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy. The standard of care for low-risk disease is single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin D.

The role of a second uterine curettage, after the diagnosis of low-risk postmolar GTN, has been controversial because of the limited data and disparate outcomes reported. In older retrospective series, a second curettage affected treatment or produced remission in only 9%-20% of patients and caused uterine perforation or major hemorrhage in 5%-8% of patients.4,5 Given relatively high rates of major complications compared with surgical cure or decreased chemotherapy cycles needed, only a limited number of patients seemed to benefit from a second procedure. On the other hand, an observational study of 544 patients who underwent second uterine evacuation after a presumed diagnosis of persistent GTD found that up to 60% of patients did not require chemotherapy afterward.6 Those with hCG levels greater than 1,500 IU/L or histologic evidence of GTD were less likely to have a surgical cure after second curettage. The indications for uterine evacuations were varied across these studies and make it nearly impossible to compare their results.

More recently, there have been two prospective trials that have tackled the question of the utility of second uterine evacuation in low-risk, nonmetastatic GTN. The Gynecologic Oncology Group performed a single-arm prospective study in the United States that enrolled patients with postmolar GTN to undergo second curettage as initial treatment of their disease.7 Of 60 eligible patients, 40% had a surgical cure (defined as normalization of hCG followed by at least 6 months of subsequent normal hCG values). Overall, 47% of patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. All surgical cures were seen in patients with WHO scores between 0 and 4. Importantly, three women were diagnosed with PSTT, which tends to be resistant to methotrexate and actinomycin D (treatment for nonmetastatic PSTT is definitive surgery with hysterectomy). The study found that hCG was a poor discriminator for achieving surgical cure. While age appeared to have an association with surgical cure (cure less likely for younger and older ages, younger than 19 and older than 40), patient numbers were too small to make a statistical conclusion. There were no uterine perforations and one patient had a grade 3 hemorrhage (requiring transfusion).

In the second prospective trial, performed in Iran, 62 patients were randomized to either second uterine evacuation or standard treatment after diagnosis of postmolar GTN.8 All patients in the surgical arm received a cervical ripening agent prior to their procedure, had their procedure under ultrasound guidance, and received misoprostol afterward to prevent uterine bleeding. Among those undergoing second uterine evacuation, 50% were cured (no need for chemotherapy). Among those needing chemotherapy after surgery, the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy needed (3.07 vs. 6.69) and the time it took to achieve negative hCG (3.23 vs. 9.19 weeks) were significantly less compared with patients who did not undergo surgery. hCG prior to second uterine evacuation could distinguish response to surgery compared with those needing chemotherapy (hCG of 1,983 IU/L or less was the level determined to best predict response). No complications related to surgery were reported.

Given prospective data available, second uterine evacuation for treatment of nonmetastatic, low-risk postmolar GTN is a reasonable treatment option and one that should be considered and discussed with patients given the potential to avoid chemotherapy or decrease the number of cycles needed. It may be prudent to limit the procedure to patients with an hCG less than 1,500-2,000 IU/L and to those between the ages of 20 and 40. While uterine hemorrhage and perforation have been reported in the literature, more recent data suggest low rates of these complications. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease and the historically controversial use of second curettage, little is known about the effects on future fertility that this procedure may have, including the development of uterine synechiae.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Ngan HY et al, FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Oct;83 Suppl 1:175-7. Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Dec;155(3):563.

2. Soper JT. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb.;137(2):355-70.

3. Ngan HY et al. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:79-85.

4. Schlaerth JB et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jun;162(6):1465-70.

5. van Trommel NE et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Oct;99(1):6-13.

6. Pezeshki M et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Dec;95(3):423-9.

7. Osborne RJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128(3):535-42.

8. Ayatollahi H et al. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Sep 21;9:665-71.

High BMI linked to better survival for cancer patients treated with ICI, but for men only

That is the conclusion of a new retrospective analysis presented during a poster session given at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology. The study sought to better understand ICI outcomes. “These are complex new treatments and, because they harness the immune system, no two patients are likely to respond in the same way. BMI has previously been associated with improved survival in patients with advanced lung cancer treated with immunotherapy. However, the reasons behind this observation, and the implications for treatment are unknown, as is whether this observation is specific for patients with only certain types of cancers,” study author Dwight Owen, MD, said in an email.

He pointed out that the retrospective nature of the findings means that they have no immediate clinical implications. “The reason for the discrepancy in males remains unclear. Although our study included a relatively large number of patients, it is a heterogenous cohort and there may be confounding factors that we haven’t recognized, so these findings need to be replicated in larger cohorts,” said Dr. Owen, a medical oncologist with The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus.

Asked if there is a potential biological explanation for a difference between males and females, Dr. Owen said that this is an area of intense research. One recent study examined whether androgen could help explain why men are more likely than women to both develop and have more aggressive nonreproductive cancers. They concluded that androgen receptor signaling may be leading to loss of effector and proliferative potential of CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Once exhausted, these cells do not respond well to stimulation that can occur after ICI treatment.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, cancer cachexia is also a key subject of study. It is characterized by weight loss and is associated with worse clinical outcomes. A cachexia mouse model found that weight loss can lead to more clearance of immune checkpoint antibodies.

Still, much more work needs to be done. “For now, how BMI, obesity, and cachexia relate to other factors, for instance the microbiome and tumor immunogenicity, are still not fully understood,” Dr. Owen said.

The study data

The researchers analyzed data from 688 patients with metastatic cancer treated at their center between 2011 and 2017. 94% were White and 5% were Black. 41% were female and the mean age was 61.9 years. The mean BMI was 28.8 kg/m2; 40% of patients had melanoma, 23% had non–small cell lung cancer, 10% had renal cancer, and 27% had another form of cancer.

For every unit decrease in BMI, the researchers observed a 1.8% decrease in mortality (hazard ratio, 0.982; P = .007). Patients with a BMI of 40 or above had better survival than all other patients grouped by 5 BMI increments (that is, 35-40, 30-35, etc.). When separated by sex, males had a significant decrease in mortality for every increase in BMI unit (HR, 0.964; P = .004), but there was no significant difference among women (HR, 1.003; P = .706). The relationship in men held up after adjustment for Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score, line of therapy, and cancer type (HR, 0.979; P = .0308). The researchers also looked at a separate cohort of 185 normal weight and 15 obese (BMI ≥ 40) NSCLC patients. Median survival was 27.5 months in the obese group and 9.1 months in the normal weight group (HR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.232-0.969).

Dr. Owen has received research funding through his institution from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Pfizer, Palobiofarma, and Onc.AI.

That is the conclusion of a new retrospective analysis presented during a poster session given at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology. The study sought to better understand ICI outcomes. “These are complex new treatments and, because they harness the immune system, no two patients are likely to respond in the same way. BMI has previously been associated with improved survival in patients with advanced lung cancer treated with immunotherapy. However, the reasons behind this observation, and the implications for treatment are unknown, as is whether this observation is specific for patients with only certain types of cancers,” study author Dwight Owen, MD, said in an email.

He pointed out that the retrospective nature of the findings means that they have no immediate clinical implications. “The reason for the discrepancy in males remains unclear. Although our study included a relatively large number of patients, it is a heterogenous cohort and there may be confounding factors that we haven’t recognized, so these findings need to be replicated in larger cohorts,” said Dr. Owen, a medical oncologist with The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus.

Asked if there is a potential biological explanation for a difference between males and females, Dr. Owen said that this is an area of intense research. One recent study examined whether androgen could help explain why men are more likely than women to both develop and have more aggressive nonreproductive cancers. They concluded that androgen receptor signaling may be leading to loss of effector and proliferative potential of CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Once exhausted, these cells do not respond well to stimulation that can occur after ICI treatment.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, cancer cachexia is also a key subject of study. It is characterized by weight loss and is associated with worse clinical outcomes. A cachexia mouse model found that weight loss can lead to more clearance of immune checkpoint antibodies.

Still, much more work needs to be done. “For now, how BMI, obesity, and cachexia relate to other factors, for instance the microbiome and tumor immunogenicity, are still not fully understood,” Dr. Owen said.

The study data

The researchers analyzed data from 688 patients with metastatic cancer treated at their center between 2011 and 2017. 94% were White and 5% were Black. 41% were female and the mean age was 61.9 years. The mean BMI was 28.8 kg/m2; 40% of patients had melanoma, 23% had non–small cell lung cancer, 10% had renal cancer, and 27% had another form of cancer.

For every unit decrease in BMI, the researchers observed a 1.8% decrease in mortality (hazard ratio, 0.982; P = .007). Patients with a BMI of 40 or above had better survival than all other patients grouped by 5 BMI increments (that is, 35-40, 30-35, etc.). When separated by sex, males had a significant decrease in mortality for every increase in BMI unit (HR, 0.964; P = .004), but there was no significant difference among women (HR, 1.003; P = .706). The relationship in men held up after adjustment for Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score, line of therapy, and cancer type (HR, 0.979; P = .0308). The researchers also looked at a separate cohort of 185 normal weight and 15 obese (BMI ≥ 40) NSCLC patients. Median survival was 27.5 months in the obese group and 9.1 months in the normal weight group (HR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.232-0.969).

Dr. Owen has received research funding through his institution from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Pfizer, Palobiofarma, and Onc.AI.

That is the conclusion of a new retrospective analysis presented during a poster session given at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology. The study sought to better understand ICI outcomes. “These are complex new treatments and, because they harness the immune system, no two patients are likely to respond in the same way. BMI has previously been associated with improved survival in patients with advanced lung cancer treated with immunotherapy. However, the reasons behind this observation, and the implications for treatment are unknown, as is whether this observation is specific for patients with only certain types of cancers,” study author Dwight Owen, MD, said in an email.

He pointed out that the retrospective nature of the findings means that they have no immediate clinical implications. “The reason for the discrepancy in males remains unclear. Although our study included a relatively large number of patients, it is a heterogenous cohort and there may be confounding factors that we haven’t recognized, so these findings need to be replicated in larger cohorts,” said Dr. Owen, a medical oncologist with The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus.

Asked if there is a potential biological explanation for a difference between males and females, Dr. Owen said that this is an area of intense research. One recent study examined whether androgen could help explain why men are more likely than women to both develop and have more aggressive nonreproductive cancers. They concluded that androgen receptor signaling may be leading to loss of effector and proliferative potential of CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Once exhausted, these cells do not respond well to stimulation that can occur after ICI treatment.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, cancer cachexia is also a key subject of study. It is characterized by weight loss and is associated with worse clinical outcomes. A cachexia mouse model found that weight loss can lead to more clearance of immune checkpoint antibodies.

Still, much more work needs to be done. “For now, how BMI, obesity, and cachexia relate to other factors, for instance the microbiome and tumor immunogenicity, are still not fully understood,” Dr. Owen said.

The study data

The researchers analyzed data from 688 patients with metastatic cancer treated at their center between 2011 and 2017. 94% were White and 5% were Black. 41% were female and the mean age was 61.9 years. The mean BMI was 28.8 kg/m2; 40% of patients had melanoma, 23% had non–small cell lung cancer, 10% had renal cancer, and 27% had another form of cancer.

For every unit decrease in BMI, the researchers observed a 1.8% decrease in mortality (hazard ratio, 0.982; P = .007). Patients with a BMI of 40 or above had better survival than all other patients grouped by 5 BMI increments (that is, 35-40, 30-35, etc.). When separated by sex, males had a significant decrease in mortality for every increase in BMI unit (HR, 0.964; P = .004), but there was no significant difference among women (HR, 1.003; P = .706). The relationship in men held up after adjustment for Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score, line of therapy, and cancer type (HR, 0.979; P = .0308). The researchers also looked at a separate cohort of 185 normal weight and 15 obese (BMI ≥ 40) NSCLC patients. Median survival was 27.5 months in the obese group and 9.1 months in the normal weight group (HR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.232-0.969).

Dr. Owen has received research funding through his institution from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Pfizer, Palobiofarma, and Onc.AI.

FROM ESMO CONGRESS 2022

Early trial supports hypofractionated radiotherapy in uterine cancer

Postoperative radiotherapy is a mainstay in the treatment of uterine cancer, but the typical 5-week regimen can be time-consuming and expensive. A pilot study found that delivery of approximately the same dose over just 2.5 weeks, known as hypofractionation, had good short-term toxicity outcomes.

Nevertheless, shortening the duration of radiotherapy could have benefits, especially in advanced uterine cancer, where chemotherapy is employed against distant metastases. Following surgery, there is a risk of both local recurrence and distant metastasis, complicating the choice of initial treatment. “Chemo can be several months long and radiation is typically several weeks. Therefore a shortened radiation schedule may have potential benefits, especially if there is an opportunity for this to be delivered earlier without delaying or interrupting chemotherapy, for example,” said lead study author Eric Leung, MD, who is an associate professor of radiation oncology at the University of Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

The research was published in JAMA Oncology.

Delivery of hypofractionation is tricky, according to Dr. Leung. “Gynecological cancer patients were treated with hypofractionation radiation to the pelvis which included the vagina, paravaginal tissues, and pelvic lymph nodes. With this relatively large pelvic volume with surrounding normal tissues, this requires a highly focused radiation treatment with advanced technology,” said Dr. Leung. The study protocol employed stereotactic technique to deliver 30 Gy in 5 fractions.

Hypofractionation could be beneficial in reduction of travel time and time spent in the hospital, as well as reducing financial burden and increasing quality of life. These benefits have taken on a larger role in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the findings are encouraging, they are preliminary, according to Vonetta Williams, MD, PhD, who wrote an accompanying editorial. “I would caution that all they’ve done is presented preliminary toxicity data, so we don’t have any proof yet that it is equally effective [compared to standard protocol], and their study cannot answer that at any rate because it was not designed to answer that question,” said Dr. Williams in an interview. She also noted that long-term follow-up is needed to measure bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, vaginal stenosis, and other side effects.

It is also uncertain whether hypofractionated doses are actually equivalent to the standard dose. “We know that they’re roughly equivalent, but that is very much a question if they are equivalent in terms of efficacy. I don’t know that I would be confident that they are. That’s probably what would give most radiation oncologists pause, because we don’t have any data to say that it is [equivalent]. Although it would be nice to shorten treatment, and I think it would certainly be better for patients, I want to caution that we want to do so once we know what the toxicity and the outcomes really are,” Dr. Williams said.

The study’s findings

The researchers enrolled 61 patients with a median age of 66 years. Thirty-nine had endometrioid adenocarcinoma, 15 serous or clear cell, 3 carcinosarcoma, and 4 had dedifferentiated disease. Sixteen patients underwent sequential chemotherapy, and 9 underwent additional vault brachytherapy. Over a median follow-up of 9 months, 54% had a worst gastrointestinal side effect of grade 1, while 13% had a worst side effect of grade 2. Among worst genitourinary side effects, 41% had grade 1 and 3% had grade 2. One patient had acute grade 3 diarrhea at fraction 5, but this resolved at follow-up. One patient had diarrhea scores that were both clinically and statistically significantly worse than baseline at fraction 5, and this improved at follow-up.

Patient-reported quality of life outcomes were generally good. Of all measures, only diarrhea was clinically and statistically worse by fraction 5, and improvement was seen at 6 weeks and 3 months. Global health status was consistent throughout treatment and follow-up. There was no change in sexual and vaginal symptoms.

Postoperative radiotherapy is a mainstay in the treatment of uterine cancer, but the typical 5-week regimen can be time-consuming and expensive. A pilot study found that delivery of approximately the same dose over just 2.5 weeks, known as hypofractionation, had good short-term toxicity outcomes.

Nevertheless, shortening the duration of radiotherapy could have benefits, especially in advanced uterine cancer, where chemotherapy is employed against distant metastases. Following surgery, there is a risk of both local recurrence and distant metastasis, complicating the choice of initial treatment. “Chemo can be several months long and radiation is typically several weeks. Therefore a shortened radiation schedule may have potential benefits, especially if there is an opportunity for this to be delivered earlier without delaying or interrupting chemotherapy, for example,” said lead study author Eric Leung, MD, who is an associate professor of radiation oncology at the University of Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

The research was published in JAMA Oncology.

Delivery of hypofractionation is tricky, according to Dr. Leung. “Gynecological cancer patients were treated with hypofractionation radiation to the pelvis which included the vagina, paravaginal tissues, and pelvic lymph nodes. With this relatively large pelvic volume with surrounding normal tissues, this requires a highly focused radiation treatment with advanced technology,” said Dr. Leung. The study protocol employed stereotactic technique to deliver 30 Gy in 5 fractions.

Hypofractionation could be beneficial in reduction of travel time and time spent in the hospital, as well as reducing financial burden and increasing quality of life. These benefits have taken on a larger role in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the findings are encouraging, they are preliminary, according to Vonetta Williams, MD, PhD, who wrote an accompanying editorial. “I would caution that all they’ve done is presented preliminary toxicity data, so we don’t have any proof yet that it is equally effective [compared to standard protocol], and their study cannot answer that at any rate because it was not designed to answer that question,” said Dr. Williams in an interview. She also noted that long-term follow-up is needed to measure bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, vaginal stenosis, and other side effects.

It is also uncertain whether hypofractionated doses are actually equivalent to the standard dose. “We know that they’re roughly equivalent, but that is very much a question if they are equivalent in terms of efficacy. I don’t know that I would be confident that they are. That’s probably what would give most radiation oncologists pause, because we don’t have any data to say that it is [equivalent]. Although it would be nice to shorten treatment, and I think it would certainly be better for patients, I want to caution that we want to do so once we know what the toxicity and the outcomes really are,” Dr. Williams said.

The study’s findings

The researchers enrolled 61 patients with a median age of 66 years. Thirty-nine had endometrioid adenocarcinoma, 15 serous or clear cell, 3 carcinosarcoma, and 4 had dedifferentiated disease. Sixteen patients underwent sequential chemotherapy, and 9 underwent additional vault brachytherapy. Over a median follow-up of 9 months, 54% had a worst gastrointestinal side effect of grade 1, while 13% had a worst side effect of grade 2. Among worst genitourinary side effects, 41% had grade 1 and 3% had grade 2. One patient had acute grade 3 diarrhea at fraction 5, but this resolved at follow-up. One patient had diarrhea scores that were both clinically and statistically significantly worse than baseline at fraction 5, and this improved at follow-up.

Patient-reported quality of life outcomes were generally good. Of all measures, only diarrhea was clinically and statistically worse by fraction 5, and improvement was seen at 6 weeks and 3 months. Global health status was consistent throughout treatment and follow-up. There was no change in sexual and vaginal symptoms.

Postoperative radiotherapy is a mainstay in the treatment of uterine cancer, but the typical 5-week regimen can be time-consuming and expensive. A pilot study found that delivery of approximately the same dose over just 2.5 weeks, known as hypofractionation, had good short-term toxicity outcomes.

Nevertheless, shortening the duration of radiotherapy could have benefits, especially in advanced uterine cancer, where chemotherapy is employed against distant metastases. Following surgery, there is a risk of both local recurrence and distant metastasis, complicating the choice of initial treatment. “Chemo can be several months long and radiation is typically several weeks. Therefore a shortened radiation schedule may have potential benefits, especially if there is an opportunity for this to be delivered earlier without delaying or interrupting chemotherapy, for example,” said lead study author Eric Leung, MD, who is an associate professor of radiation oncology at the University of Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

The research was published in JAMA Oncology.

Delivery of hypofractionation is tricky, according to Dr. Leung. “Gynecological cancer patients were treated with hypofractionation radiation to the pelvis which included the vagina, paravaginal tissues, and pelvic lymph nodes. With this relatively large pelvic volume with surrounding normal tissues, this requires a highly focused radiation treatment with advanced technology,” said Dr. Leung. The study protocol employed stereotactic technique to deliver 30 Gy in 5 fractions.

Hypofractionation could be beneficial in reduction of travel time and time spent in the hospital, as well as reducing financial burden and increasing quality of life. These benefits have taken on a larger role in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the findings are encouraging, they are preliminary, according to Vonetta Williams, MD, PhD, who wrote an accompanying editorial. “I would caution that all they’ve done is presented preliminary toxicity data, so we don’t have any proof yet that it is equally effective [compared to standard protocol], and their study cannot answer that at any rate because it was not designed to answer that question,” said Dr. Williams in an interview. She also noted that long-term follow-up is needed to measure bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, vaginal stenosis, and other side effects.

It is also uncertain whether hypofractionated doses are actually equivalent to the standard dose. “We know that they’re roughly equivalent, but that is very much a question if they are equivalent in terms of efficacy. I don’t know that I would be confident that they are. That’s probably what would give most radiation oncologists pause, because we don’t have any data to say that it is [equivalent]. Although it would be nice to shorten treatment, and I think it would certainly be better for patients, I want to caution that we want to do so once we know what the toxicity and the outcomes really are,” Dr. Williams said.

The study’s findings

The researchers enrolled 61 patients with a median age of 66 years. Thirty-nine had endometrioid adenocarcinoma, 15 serous or clear cell, 3 carcinosarcoma, and 4 had dedifferentiated disease. Sixteen patients underwent sequential chemotherapy, and 9 underwent additional vault brachytherapy. Over a median follow-up of 9 months, 54% had a worst gastrointestinal side effect of grade 1, while 13% had a worst side effect of grade 2. Among worst genitourinary side effects, 41% had grade 1 and 3% had grade 2. One patient had acute grade 3 diarrhea at fraction 5, but this resolved at follow-up. One patient had diarrhea scores that were both clinically and statistically significantly worse than baseline at fraction 5, and this improved at follow-up.

Patient-reported quality of life outcomes were generally good. Of all measures, only diarrhea was clinically and statistically worse by fraction 5, and improvement was seen at 6 weeks and 3 months. Global health status was consistent throughout treatment and follow-up. There was no change in sexual and vaginal symptoms.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

A farewell to arms? Drug approvals based on single-arm trials can be flawed

PARIS – with results that should only be used, under certain conditions, for accelerated approvals that should then be followed by confirmatory studies.

In fact, many drugs approved over the last decade based solely on data from single-arm trials have been subsequently withdrawn when put through the rigors of a head-to-head randomized controlled trial, according to Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from the department of oncology at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont.

“Single-arm trials are not meant to provide confirmatory evidence sufficient for approval; However, that ship has sailed, and we have several drugs that are approved on the basis of single-arm trials, but we need to make sure that those approvals are accelerated or conditional approvals, not regular approval,” he said in a presentation included in a special session on drug approvals at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

“We should not allow premature regular approval based on single-arm trials, because once a drug gets conditional approval, access is not an issue. Patients will have access to the drug anyway, but we should ensure that robust evidence follows, and long-term follow-up data are needed to develop confidence in the efficacy outcomes that are seen in single-arm trials,” he said.

In many cases, single-arm trials are large enough or of long enough duration that investigators could have reasonably performed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in the first place, Dr. Gyawali added.

Why do single-arm trials?

The term “single-arm registration trial” is something of an oxymoron, he said, noting that the purpose of such trials should be whether to take the drug to a phase 3, randomized trial. But as authors of a 2019 study in JAMA Network Open showed, of a sample of phase 3 RCTs, 42% did not have a prior phase 2 trial, and 28% had a negative phase 2 trial. Single-arm trials may be acceptable for conditional drug approvals if all of the following conditions are met:

- A RCT is not possible because the disease is rare or randomization would be unethical.

- The safety of the drug is established and its potential benefits outweigh its risks.

- The drug is associated with a high and durable overall or objective response rate.

- The mechanism of action is supported by a strong scientific rationale, and if the drug may meet an unmet medical need.

Survival endpoints won’t do

Efficacy endpoints typically used in RCTs, such as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) can be misleading because they may be a result of the natural history of the disease and not the drug being tested, whereas ORRs are almost certainly reflective of the action of the drug itself, because spontaneous tumor regression is a rare phenomenon, Dr. Gyawali said.

He cautioned, however, that the ORR of placebo is not zero percent. For example in a 2018 study of sorafenib (Nexavar) versus placebo for advanced or refractory desmoid tumors, the ORR with the active drug was 33%, and the ORR for placebo was 20%.

It’s also open to question, he said, what constitutes an acceptably high ORR and duration of response, pointing to Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval of an indication for nivolumab (Opdivo) for treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) that had progressed on sorafenib. In the single-arm trial used as the basis for approval, the ORRs as assessed by an independent central review committee blinded to the results was 14.3%.

“So, nivolumab in hepatocellular cancer was approved on the basis of a response rate lower than that of placebo, albeit in a different tumor. But the point I’m trying to show here is we don’t have a good definition of what is a good response rate,” he said.

In July 2021, Bristol-Myers Squibb voluntarily withdrew the HCC indication for nivolumab, following negative results of the CheckMate 459 trial and a 5-4 vote against continuing the accelerated approval.

On second thought ...

Citing data compiled by Nathan I. Cherny, MD, from Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem, Dr. Gyawali noted that 58 of 161 FDA approvals from 2017 to 2021 of drugs for adult solid tumors were based on single-arm trials. Of the 58 drugs, 39 received accelerated approvals, and 19 received regular approvals; of the 39 that received accelerated approvals, 4 were subsequently withdrawn, 8 were converted to regular approvals, and the remainder continued as accelerated approvals.

Interestingly, the median response rate among all the drugs was 40%, and did not differ between the type of approval received, suggesting that response rates are not predictive of whether a drug will receive a conditional or full-fledged go-ahead.

What’s rare and safe?

The definition of a rare disease in the United States is one that affects fewer than 40,000 per year, and in Europe it’s an incidence rate of less than 6 per 100,000 population, Dr. Gyawali noted. But he argued that even non–small cell lung cancer, the most common form of cancer in the world, could be considered rare if it is broken down into subtypes that are treated according to specific mutations that may occur in a relatively small number of patients.

He also noted that a specific drug’s safety, one of the most important criteria for granting approval to a drug based on a single-arm trial, can be difficult to judge without adequate controls for comparison.

Cherry-picking patients

Winette van der Graaf, MD, president of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer, who attended the session where Dr. Gyawali’s presentation was played, said in an interview that clinicians should cast a critical eye on how trials are designed and conducted, including patient selection and choice of endpoints.

“One of the most obvious things to be concerned about is that we’re still having patients with good performance status enrolled, mostly PS 0 or 1, so how representative are these clinical trials for the patients we see in front of us on a daily basis?” she said.

“The other question is radiological endpoints, which we focus on with OS and PFS are most important for patients, especially if you consider that if patients may have asymptomatic disease, and we are only treating them with potentially toxic medication, what are we doing for them? Median overall survival when you look at all of these trials is only 4 months, so we really need to take into account how we affect patients in clinical trials,” she added.

Dr. van der Graaf emphasized that clinical trial investigators need to more routinely incorporate quality of life measures and other patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial results to help regulators and clinicians in practice get a better sense of the true clinical benefit of a new drug.

Dr. Gyawali did not disclose a funding source for his presentation. He reported consulting fees from Vivio Health and research grants from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Dr. van der Graaf reported no conflicts of interest.

PARIS – with results that should only be used, under certain conditions, for accelerated approvals that should then be followed by confirmatory studies.

In fact, many drugs approved over the last decade based solely on data from single-arm trials have been subsequently withdrawn when put through the rigors of a head-to-head randomized controlled trial, according to Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from the department of oncology at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont.

“Single-arm trials are not meant to provide confirmatory evidence sufficient for approval; However, that ship has sailed, and we have several drugs that are approved on the basis of single-arm trials, but we need to make sure that those approvals are accelerated or conditional approvals, not regular approval,” he said in a presentation included in a special session on drug approvals at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

“We should not allow premature regular approval based on single-arm trials, because once a drug gets conditional approval, access is not an issue. Patients will have access to the drug anyway, but we should ensure that robust evidence follows, and long-term follow-up data are needed to develop confidence in the efficacy outcomes that are seen in single-arm trials,” he said.

In many cases, single-arm trials are large enough or of long enough duration that investigators could have reasonably performed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in the first place, Dr. Gyawali added.

Why do single-arm trials?

The term “single-arm registration trial” is something of an oxymoron, he said, noting that the purpose of such trials should be whether to take the drug to a phase 3, randomized trial. But as authors of a 2019 study in JAMA Network Open showed, of a sample of phase 3 RCTs, 42% did not have a prior phase 2 trial, and 28% had a negative phase 2 trial. Single-arm trials may be acceptable for conditional drug approvals if all of the following conditions are met:

- A RCT is not possible because the disease is rare or randomization would be unethical.

- The safety of the drug is established and its potential benefits outweigh its risks.

- The drug is associated with a high and durable overall or objective response rate.

- The mechanism of action is supported by a strong scientific rationale, and if the drug may meet an unmet medical need.

Survival endpoints won’t do

Efficacy endpoints typically used in RCTs, such as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) can be misleading because they may be a result of the natural history of the disease and not the drug being tested, whereas ORRs are almost certainly reflective of the action of the drug itself, because spontaneous tumor regression is a rare phenomenon, Dr. Gyawali said.

He cautioned, however, that the ORR of placebo is not zero percent. For example in a 2018 study of sorafenib (Nexavar) versus placebo for advanced or refractory desmoid tumors, the ORR with the active drug was 33%, and the ORR for placebo was 20%.

It’s also open to question, he said, what constitutes an acceptably high ORR and duration of response, pointing to Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval of an indication for nivolumab (Opdivo) for treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) that had progressed on sorafenib. In the single-arm trial used as the basis for approval, the ORRs as assessed by an independent central review committee blinded to the results was 14.3%.

“So, nivolumab in hepatocellular cancer was approved on the basis of a response rate lower than that of placebo, albeit in a different tumor. But the point I’m trying to show here is we don’t have a good definition of what is a good response rate,” he said.

In July 2021, Bristol-Myers Squibb voluntarily withdrew the HCC indication for nivolumab, following negative results of the CheckMate 459 trial and a 5-4 vote against continuing the accelerated approval.

On second thought ...

Citing data compiled by Nathan I. Cherny, MD, from Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem, Dr. Gyawali noted that 58 of 161 FDA approvals from 2017 to 2021 of drugs for adult solid tumors were based on single-arm trials. Of the 58 drugs, 39 received accelerated approvals, and 19 received regular approvals; of the 39 that received accelerated approvals, 4 were subsequently withdrawn, 8 were converted to regular approvals, and the remainder continued as accelerated approvals.

Interestingly, the median response rate among all the drugs was 40%, and did not differ between the type of approval received, suggesting that response rates are not predictive of whether a drug will receive a conditional or full-fledged go-ahead.

What’s rare and safe?

The definition of a rare disease in the United States is one that affects fewer than 40,000 per year, and in Europe it’s an incidence rate of less than 6 per 100,000 population, Dr. Gyawali noted. But he argued that even non–small cell lung cancer, the most common form of cancer in the world, could be considered rare if it is broken down into subtypes that are treated according to specific mutations that may occur in a relatively small number of patients.

He also noted that a specific drug’s safety, one of the most important criteria for granting approval to a drug based on a single-arm trial, can be difficult to judge without adequate controls for comparison.

Cherry-picking patients

Winette van der Graaf, MD, president of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer, who attended the session where Dr. Gyawali’s presentation was played, said in an interview that clinicians should cast a critical eye on how trials are designed and conducted, including patient selection and choice of endpoints.

“One of the most obvious things to be concerned about is that we’re still having patients with good performance status enrolled, mostly PS 0 or 1, so how representative are these clinical trials for the patients we see in front of us on a daily basis?” she said.

“The other question is radiological endpoints, which we focus on with OS and PFS are most important for patients, especially if you consider that if patients may have asymptomatic disease, and we are only treating them with potentially toxic medication, what are we doing for them? Median overall survival when you look at all of these trials is only 4 months, so we really need to take into account how we affect patients in clinical trials,” she added.

Dr. van der Graaf emphasized that clinical trial investigators need to more routinely incorporate quality of life measures and other patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial results to help regulators and clinicians in practice get a better sense of the true clinical benefit of a new drug.

Dr. Gyawali did not disclose a funding source for his presentation. He reported consulting fees from Vivio Health and research grants from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Dr. van der Graaf reported no conflicts of interest.

PARIS – with results that should only be used, under certain conditions, for accelerated approvals that should then be followed by confirmatory studies.

In fact, many drugs approved over the last decade based solely on data from single-arm trials have been subsequently withdrawn when put through the rigors of a head-to-head randomized controlled trial, according to Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from the department of oncology at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont.

“Single-arm trials are not meant to provide confirmatory evidence sufficient for approval; However, that ship has sailed, and we have several drugs that are approved on the basis of single-arm trials, but we need to make sure that those approvals are accelerated or conditional approvals, not regular approval,” he said in a presentation included in a special session on drug approvals at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

“We should not allow premature regular approval based on single-arm trials, because once a drug gets conditional approval, access is not an issue. Patients will have access to the drug anyway, but we should ensure that robust evidence follows, and long-term follow-up data are needed to develop confidence in the efficacy outcomes that are seen in single-arm trials,” he said.

In many cases, single-arm trials are large enough or of long enough duration that investigators could have reasonably performed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in the first place, Dr. Gyawali added.

Why do single-arm trials?

The term “single-arm registration trial” is something of an oxymoron, he said, noting that the purpose of such trials should be whether to take the drug to a phase 3, randomized trial. But as authors of a 2019 study in JAMA Network Open showed, of a sample of phase 3 RCTs, 42% did not have a prior phase 2 trial, and 28% had a negative phase 2 trial. Single-arm trials may be acceptable for conditional drug approvals if all of the following conditions are met:

- A RCT is not possible because the disease is rare or randomization would be unethical.

- The safety of the drug is established and its potential benefits outweigh its risks.

- The drug is associated with a high and durable overall or objective response rate.

- The mechanism of action is supported by a strong scientific rationale, and if the drug may meet an unmet medical need.

Survival endpoints won’t do

Efficacy endpoints typically used in RCTs, such as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) can be misleading because they may be a result of the natural history of the disease and not the drug being tested, whereas ORRs are almost certainly reflective of the action of the drug itself, because spontaneous tumor regression is a rare phenomenon, Dr. Gyawali said.

He cautioned, however, that the ORR of placebo is not zero percent. For example in a 2018 study of sorafenib (Nexavar) versus placebo for advanced or refractory desmoid tumors, the ORR with the active drug was 33%, and the ORR for placebo was 20%.

It’s also open to question, he said, what constitutes an acceptably high ORR and duration of response, pointing to Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval of an indication for nivolumab (Opdivo) for treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) that had progressed on sorafenib. In the single-arm trial used as the basis for approval, the ORRs as assessed by an independent central review committee blinded to the results was 14.3%.

“So, nivolumab in hepatocellular cancer was approved on the basis of a response rate lower than that of placebo, albeit in a different tumor. But the point I’m trying to show here is we don’t have a good definition of what is a good response rate,” he said.

In July 2021, Bristol-Myers Squibb voluntarily withdrew the HCC indication for nivolumab, following negative results of the CheckMate 459 trial and a 5-4 vote against continuing the accelerated approval.

On second thought ...

Citing data compiled by Nathan I. Cherny, MD, from Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem, Dr. Gyawali noted that 58 of 161 FDA approvals from 2017 to 2021 of drugs for adult solid tumors were based on single-arm trials. Of the 58 drugs, 39 received accelerated approvals, and 19 received regular approvals; of the 39 that received accelerated approvals, 4 were subsequently withdrawn, 8 were converted to regular approvals, and the remainder continued as accelerated approvals.

Interestingly, the median response rate among all the drugs was 40%, and did not differ between the type of approval received, suggesting that response rates are not predictive of whether a drug will receive a conditional or full-fledged go-ahead.

What’s rare and safe?

The definition of a rare disease in the United States is one that affects fewer than 40,000 per year, and in Europe it’s an incidence rate of less than 6 per 100,000 population, Dr. Gyawali noted. But he argued that even non–small cell lung cancer, the most common form of cancer in the world, could be considered rare if it is broken down into subtypes that are treated according to specific mutations that may occur in a relatively small number of patients.

He also noted that a specific drug’s safety, one of the most important criteria for granting approval to a drug based on a single-arm trial, can be difficult to judge without adequate controls for comparison.

Cherry-picking patients

Winette van der Graaf, MD, president of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer, who attended the session where Dr. Gyawali’s presentation was played, said in an interview that clinicians should cast a critical eye on how trials are designed and conducted, including patient selection and choice of endpoints.

“One of the most obvious things to be concerned about is that we’re still having patients with good performance status enrolled, mostly PS 0 or 1, so how representative are these clinical trials for the patients we see in front of us on a daily basis?” she said.

“The other question is radiological endpoints, which we focus on with OS and PFS are most important for patients, especially if you consider that if patients may have asymptomatic disease, and we are only treating them with potentially toxic medication, what are we doing for them? Median overall survival when you look at all of these trials is only 4 months, so we really need to take into account how we affect patients in clinical trials,” she added.

Dr. van der Graaf emphasized that clinical trial investigators need to more routinely incorporate quality of life measures and other patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial results to help regulators and clinicians in practice get a better sense of the true clinical benefit of a new drug.

Dr. Gyawali did not disclose a funding source for his presentation. He reported consulting fees from Vivio Health and research grants from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Dr. van der Graaf reported no conflicts of interest.

AT ESMO CONGRESS 2022

Time to cancer diagnoses in U.S. averages 5 months

Time to diagnosis is a crucial factor in cancer. Delays can lead to diagnosis at later stages and prevent optimal therapeutic strategies, both of which have the potential to reduce survival. An estimated 63%-82% of cancers get diagnosed as a result of symptom presentation, and delays in diagnosis can hamper treatment efforts. Diagnosis can be challenging because common symptoms – such as weight loss, weakness, poor appetite, and shortness of breath – are nonspecific.

A new analysis of U.S.-based data shows that the average time to diagnosis is 5.2 months for patients with solid tumors. The authors of the study call for better cancer diagnosis pathways in the U.S.

“Several countries, including the UK, Denmark, Sweden, Canada and Australia, have identified the importance and potential impact of more timely diagnosis by establishing national guidelines, special programs, and treatment pathways. However, in the U.S., there’s relatively little research and effort focused on streamlining the diagnostic pathway. Currently, the U.S. does not have established cancer diagnostic pathways that are used consistently,” Matthew Gitlin, PharmD, said during a presentation at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“That is often associated with worse clinical outcomes, increased economic burden, and decreased health related quality of life,” said Dr. Gitlin, founder and managing director of the health economics consulting firm BluePath Solutions, which conducted the analysis.

The study retrospectively examined administrative billing data drawn from the Clinformatics for Managed Markets longitudinal database. The data represent individuals in Medicare Advantage and a large, U.S.-based private insurance plan. Between 2018 and 2019, there were 458,818 cancer diagnoses. The mean age was 70.6 years and 49.6% of the patients were female. Sixty-five percent were White, 11.1% Black, 8.3% Hispanic, and 2.5% Asian. No race data were available for 13.2%. Medicare Advantage was the primary insurance carrier for 74.0%, and 24.0% had a commercial plan.

The mean time to diagnosis across all tumors was 5.2 months (standard deviation, 5.5 months). There was significant variation across different tumor types, as well as within the same tumor type. The median value was 3.9 months (interquartile range, 1.1-7.2 months).

Mean time to diagnosis ranged from 121.6 days for bladder cancer to as high as 229 days for multiple myeloma. Standard deviations were nearly as large or even larger than the mean values. The study showed that 15.8% of patients waited 6 months or longer for a diagnosis. Delays were most common in kidney cancer, colorectal cancer, gallbladder cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma: More than 25% of patients had a time to diagnosis of at least 6 months in these tumors.

“Although there is limited research in the published literature, our findings are consistent with that literature that does exist. Development or modification of policies, guidelines or medical interventions that streamline the diagnostic pathway are needed to optimize patient outcomes and reduce resource burden and cost to the health care system,” Dr. Gitlin said.

Previous literature on this topic has seen wide variation in how time to diagnosis is defined, and most research is conducted in high-income countries, according to Felipe Roitberg, PhD, who served as a discussant during the session. “Most of the countries and patients in need are localized in low- and middle-income countries, so that is a call to action (for more research),” said Dr. Roitberg, a clinical oncologist at Hospital Sírio Libanês in São Paulo, Brazil.

The study did not look at the associations between race and time to diagnosis. “This is a source of analysis could further be explored,” said Dr. Roitberg.

He noted that the ABC-DO prospective cohort study in sub-Saharan Africa found large variations in breast cancer survival by country, and its authors predicted that downstaging and improvements in treatment could prevent up to one-third of projected breast cancer deaths over the next decade. “So these are the drivers of populational gain in terms of overall survival – not more drugs, not more services available, but coordination of services and making sure the patient has a right pathway (to diagnosis and treatment),” Dr. Roitberg said.

Dr. Gitlin has received consulting fees from GRAIL LLC, which is a subsidiary of Illumina. Dr. Roitberg has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Roche, MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, Nestle Health Science, Dr Reddy’s, and Oncologia Brazil. He has consulted for MSD Oncology. He has received research funding from Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Bayer, AstraZeneca, and Takeda.

Time to diagnosis is a crucial factor in cancer. Delays can lead to diagnosis at later stages and prevent optimal therapeutic strategies, both of which have the potential to reduce survival. An estimated 63%-82% of cancers get diagnosed as a result of symptom presentation, and delays in diagnosis can hamper treatment efforts. Diagnosis can be challenging because common symptoms – such as weight loss, weakness, poor appetite, and shortness of breath – are nonspecific.

A new analysis of U.S.-based data shows that the average time to diagnosis is 5.2 months for patients with solid tumors. The authors of the study call for better cancer diagnosis pathways in the U.S.

“Several countries, including the UK, Denmark, Sweden, Canada and Australia, have identified the importance and potential impact of more timely diagnosis by establishing national guidelines, special programs, and treatment pathways. However, in the U.S., there’s relatively little research and effort focused on streamlining the diagnostic pathway. Currently, the U.S. does not have established cancer diagnostic pathways that are used consistently,” Matthew Gitlin, PharmD, said during a presentation at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“That is often associated with worse clinical outcomes, increased economic burden, and decreased health related quality of life,” said Dr. Gitlin, founder and managing director of the health economics consulting firm BluePath Solutions, which conducted the analysis.

The study retrospectively examined administrative billing data drawn from the Clinformatics for Managed Markets longitudinal database. The data represent individuals in Medicare Advantage and a large, U.S.-based private insurance plan. Between 2018 and 2019, there were 458,818 cancer diagnoses. The mean age was 70.6 years and 49.6% of the patients were female. Sixty-five percent were White, 11.1% Black, 8.3% Hispanic, and 2.5% Asian. No race data were available for 13.2%. Medicare Advantage was the primary insurance carrier for 74.0%, and 24.0% had a commercial plan.

The mean time to diagnosis across all tumors was 5.2 months (standard deviation, 5.5 months). There was significant variation across different tumor types, as well as within the same tumor type. The median value was 3.9 months (interquartile range, 1.1-7.2 months).

Mean time to diagnosis ranged from 121.6 days for bladder cancer to as high as 229 days for multiple myeloma. Standard deviations were nearly as large or even larger than the mean values. The study showed that 15.8% of patients waited 6 months or longer for a diagnosis. Delays were most common in kidney cancer, colorectal cancer, gallbladder cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma: More than 25% of patients had a time to diagnosis of at least 6 months in these tumors.

“Although there is limited research in the published literature, our findings are consistent with that literature that does exist. Development or modification of policies, guidelines or medical interventions that streamline the diagnostic pathway are needed to optimize patient outcomes and reduce resource burden and cost to the health care system,” Dr. Gitlin said.

Previous literature on this topic has seen wide variation in how time to diagnosis is defined, and most research is conducted in high-income countries, according to Felipe Roitberg, PhD, who served as a discussant during the session. “Most of the countries and patients in need are localized in low- and middle-income countries, so that is a call to action (for more research),” said Dr. Roitberg, a clinical oncologist at Hospital Sírio Libanês in São Paulo, Brazil.

The study did not look at the associations between race and time to diagnosis. “This is a source of analysis could further be explored,” said Dr. Roitberg.

He noted that the ABC-DO prospective cohort study in sub-Saharan Africa found large variations in breast cancer survival by country, and its authors predicted that downstaging and improvements in treatment could prevent up to one-third of projected breast cancer deaths over the next decade. “So these are the drivers of populational gain in terms of overall survival – not more drugs, not more services available, but coordination of services and making sure the patient has a right pathway (to diagnosis and treatment),” Dr. Roitberg said.

Dr. Gitlin has received consulting fees from GRAIL LLC, which is a subsidiary of Illumina. Dr. Roitberg has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Roche, MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, Nestle Health Science, Dr Reddy’s, and Oncologia Brazil. He has consulted for MSD Oncology. He has received research funding from Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Bayer, AstraZeneca, and Takeda.

Time to diagnosis is a crucial factor in cancer. Delays can lead to diagnosis at later stages and prevent optimal therapeutic strategies, both of which have the potential to reduce survival. An estimated 63%-82% of cancers get diagnosed as a result of symptom presentation, and delays in diagnosis can hamper treatment efforts. Diagnosis can be challenging because common symptoms – such as weight loss, weakness, poor appetite, and shortness of breath – are nonspecific.

A new analysis of U.S.-based data shows that the average time to diagnosis is 5.2 months for patients with solid tumors. The authors of the study call for better cancer diagnosis pathways in the U.S.

“Several countries, including the UK, Denmark, Sweden, Canada and Australia, have identified the importance and potential impact of more timely diagnosis by establishing national guidelines, special programs, and treatment pathways. However, in the U.S., there’s relatively little research and effort focused on streamlining the diagnostic pathway. Currently, the U.S. does not have established cancer diagnostic pathways that are used consistently,” Matthew Gitlin, PharmD, said during a presentation at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“That is often associated with worse clinical outcomes, increased economic burden, and decreased health related quality of life,” said Dr. Gitlin, founder and managing director of the health economics consulting firm BluePath Solutions, which conducted the analysis.

The study retrospectively examined administrative billing data drawn from the Clinformatics for Managed Markets longitudinal database. The data represent individuals in Medicare Advantage and a large, U.S.-based private insurance plan. Between 2018 and 2019, there were 458,818 cancer diagnoses. The mean age was 70.6 years and 49.6% of the patients were female. Sixty-five percent were White, 11.1% Black, 8.3% Hispanic, and 2.5% Asian. No race data were available for 13.2%. Medicare Advantage was the primary insurance carrier for 74.0%, and 24.0% had a commercial plan.

The mean time to diagnosis across all tumors was 5.2 months (standard deviation, 5.5 months). There was significant variation across different tumor types, as well as within the same tumor type. The median value was 3.9 months (interquartile range, 1.1-7.2 months).

Mean time to diagnosis ranged from 121.6 days for bladder cancer to as high as 229 days for multiple myeloma. Standard deviations were nearly as large or even larger than the mean values. The study showed that 15.8% of patients waited 6 months or longer for a diagnosis. Delays were most common in kidney cancer, colorectal cancer, gallbladder cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma: More than 25% of patients had a time to diagnosis of at least 6 months in these tumors.

“Although there is limited research in the published literature, our findings are consistent with that literature that does exist. Development or modification of policies, guidelines or medical interventions that streamline the diagnostic pathway are needed to optimize patient outcomes and reduce resource burden and cost to the health care system,” Dr. Gitlin said.

Previous literature on this topic has seen wide variation in how time to diagnosis is defined, and most research is conducted in high-income countries, according to Felipe Roitberg, PhD, who served as a discussant during the session. “Most of the countries and patients in need are localized in low- and middle-income countries, so that is a call to action (for more research),” said Dr. Roitberg, a clinical oncologist at Hospital Sírio Libanês in São Paulo, Brazil.

The study did not look at the associations between race and time to diagnosis. “This is a source of analysis could further be explored,” said Dr. Roitberg.

He noted that the ABC-DO prospective cohort study in sub-Saharan Africa found large variations in breast cancer survival by country, and its authors predicted that downstaging and improvements in treatment could prevent up to one-third of projected breast cancer deaths over the next decade. “So these are the drivers of populational gain in terms of overall survival – not more drugs, not more services available, but coordination of services and making sure the patient has a right pathway (to diagnosis and treatment),” Dr. Roitberg said.

Dr. Gitlin has received consulting fees from GRAIL LLC, which is a subsidiary of Illumina. Dr. Roitberg has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Roche, MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, Nestle Health Science, Dr Reddy’s, and Oncologia Brazil. He has consulted for MSD Oncology. He has received research funding from Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Bayer, AstraZeneca, and Takeda.

FROM ESMO CONGRESS 2022

Shortened radiotherapy for endometrial cancer looks safe, questions remain

Postoperative radiotherapy is a mainstay in the treatment of endometrial cancer, but the typical 5-week regimen can be time consuming and expensive. A pilot study found that delivery of approximately the same dose over just two and a half weeks, known as hypofractionation, had good short-term toxicity outcomes.

Nevertheless, shortening the duration of radiotherapy could have benefits, especially in advanced uterine cancer, where chemotherapy is employed against distant metastases. Following surgery, there is a risk of both local recurrence and distant metastasis, complicating the choice of initial treatment. “Chemo can be several months long and radiation is typically several weeks. Therefore a shortened radiation schedule may have potential benefits, especially if there is an opportunity for this to be delivered earlier without delaying or interrupting chemotherapy, for example,” said lead study author Eric Leung, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at the University of Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

The research was published in JAMA Oncology.