User login

One strikeout, one hit against low-grade serous carcinomas

Two MEK inhibitors were tested against recurrent low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum, but only one inhibitor offered clinical benefit over standard care, investigators from two randomized trials reported.

Trametinib improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with standard care, while binimetinib conferred no PFS benefit.

In a phase 2/3 trial, the median PFS was 13 months for patients treated with trametinib and 7.2 months for patients who received an aromatase inhibitor or chemotherapy (P < .0001).

“Our findings suggest that trametinib represents a new standard-of-care treatment option for women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma,” said investigator David M. Gershenson, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

In contrast, in the phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, there was no significant difference in PFS between patients treated with binimetinib and those who received physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median PFS was 11.2 months with binimetinib and 14.1 months with chemotherapy (P = .752).

“Although this study did not meet its primary endpoint, binimetinib showed activity in low-grade serous ovarian cancer across the efficacy endpoints evaluated, with a response rate of 24% and a median PFS of 11.2 months on updated analysis. Chemotherapy responses were better than predicted, based on historical retrospective data,” said investigator Rachel N. Grisham, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The binimetinib trial and the trametinib trial were both discussed during a webinar on rare tumors covering research slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chemoresistant cancers

Low-grade serous ovarian or peritoneal cancers are rare, accounting for only 5% to 10% of all serous cancers, Dr. Gershenson noted.

“[Low-grade serous cancers are] characterized by alterations in the MAP kinase pathway, as well as relative chemoresistance, and prolonged overall survival compared to high-grade serous cancers. Because of this subtype’s relative chemoresistance, the search for novel therapeutics has predominated over the last decade or so,” he said.

MEK inhibitors interfere with the MEK1 and MEK2 enzymes in the MAPK pathway. Alterations in MAPK, especially in KRAS and BRAF proteins, are found in 30%-60% of low-grade serous carcinomas, providing the rationale for MEK inhibitors in these rare malignancies.

Trametinib study

In a phase 2/3 study, Dr. Gershenson and colleagues enrolled 260 patients with recurrent, low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Patients were randomized to receive either trametinib at 2 mg daily continuously until progression (n = 130) or standard care (n = 130).

Standard care consisted of one of the following: letrozole at 2.5 mg daily; pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40-50 mg IV every 28 days; weekly paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 for 3 out of 4 weeks; tamoxifen at 20 mg twice daily; or topotecan at 4 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. Patients randomized to standard care could be crossed over to trametinib at progression.

All patients had at least one prior line of platinum-based chemotherapy, and nearly half had three or more prior lines of therapy. The median age was 56.6 years in the trametinib arm and 55.3 years in the control arm.

At a median follow-up of 31.4 months, median PFS, the primary endpoint, was 13 months with trametinib vs. 7.2 months with standard care. The hazard ratio (HR) for progression on trametinib was 0.48 (P < .0001).

The overall response rates were 26.2% in the trametinib arm and 6.2% in the standard care arm. The odds ratio for response on trametinib was 5.4 (P < .0001).

For 88 patients who crossed over to trametinib, the median PFS was 10.8 months, and the overall response rate was 15%.

Trametinib was also associated with a significantly longer response duration, at a median of 13.6 months, compared with 5.9 months for standard care (P value not shown).

The median overall survival was 37 months with trametinib and 29.2 months with standard care, with an HR favoring trametinib of 0.75, although this just missed statistical significance (P = .054). Dr. Gershenson pointed out that the overall survival in the standard care arm included patients who had been crossed over to trametinib.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events included hematologic toxicities in 13.4% of patients on trametinib and 9.4% on standard care; gastrointestinal toxicity in 27.6% and 29%, respectively; skin toxicities in 15% and 3.9%, respectively; and vascular toxicities in 18.9% and 8.6%, respectively.

Binimetinib study

The phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 study enrolled 341 patients with low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum. Patients were randomized on a 2:1 basis to receive either binimetinib at 45 mg twice daily (n = 228) or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (n = 113). Chemotherapy consisted of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40 mg/m2 on day 1 of each 28-day cycle; paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle; or topotecan at 1.25 mg/m2 IV on days 1-5 of each 21-day cycle.

The efficacy analysis included 227 patients assigned to binimetinib and 106 assigned to chemotherapy.

A planned interim analysis was performed in 2016 after the first 303 patients were enrolled. At that time, the median PFS by blinded central review was 9.1 months in the binimetinib arm and 10.6 months in the physician’s choice arm (HR, 1.21; P = .807), so the trial was halted early for futility. Patients on active treatment at the time could continue until progression and were followed by local radiology.

At the interim analysis, secondary endpoints were also similar between the arms. The overall response rate was 16% in the binimetinib arm and 13% in the chemotherapy arm.

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events with binimetinib were blood creatinine phosphokinase increase (26%) and vomiting (10%).

Dr. Grisham also reported updated follow-up results through January 2019.

The median PFS in the updated analysis was 11.2 months with the MEK inhibitor and 14.1 months with chemotherapy, a difference that was not statistically significant (HR, 1.12; P = .752). Updated overall response rates were the same in both arms, at 24%.

A post hoc molecular analysis of 215 patients suggested a possible association between KRAS mutation and response to binimetinib.

Two MEKs, one ‘meh’

Discussant Jubilee Brown, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that “with a 2% to 5% chance of response in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer, there is a low bar for any compound to demonstrate success.”

Regarding the MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, she noted that “this study did not meet its primary endpoint, but perhaps the endpoint is not reflective of the importance of the study.”

A different outcome might have occurred had investigators stratified patients by KRAS status upfront, comparing patients with KRAS mutations treated with binimetinib to KRAS wild-type patients treated with either a MEK inhibitor or physician’s choice of care, Dr. Brown said.

She agreed with the assertion by Dr. Gershenson and colleagues that improved PFS qualifies trametinib to be considered a new option for standard care, ”especially in a rare tumor setting with limited options. This is a huge win for patients.”

The trametinib study was sponsored by NRG Oncology and the UK National Cancer Research Institute. Dr. Gershenson disclosed relationships with NRG Oncology, Genentech, Novartis, Elsevier, and UpToDate, as well as stock in several companies.

The binimetinib study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Grisham disclosed relationships with Clovis, Regeneron, Mateon, Amgen, Abbvie, OncLive, PRIME, MCM, and Medscape. MDedge News and Medscape are owned by the same parent organization.

Dr. Brown disclosed consulting for Biodesix, Caris, Clovis, Genentech, Invitae, Janssen, Olympus, OncLive, and Tempus.

SOURCE: Gershenson DM et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 42; Grisham RN et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 41.

Two MEK inhibitors were tested against recurrent low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum, but only one inhibitor offered clinical benefit over standard care, investigators from two randomized trials reported.

Trametinib improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with standard care, while binimetinib conferred no PFS benefit.

In a phase 2/3 trial, the median PFS was 13 months for patients treated with trametinib and 7.2 months for patients who received an aromatase inhibitor or chemotherapy (P < .0001).

“Our findings suggest that trametinib represents a new standard-of-care treatment option for women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma,” said investigator David M. Gershenson, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

In contrast, in the phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, there was no significant difference in PFS between patients treated with binimetinib and those who received physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median PFS was 11.2 months with binimetinib and 14.1 months with chemotherapy (P = .752).

“Although this study did not meet its primary endpoint, binimetinib showed activity in low-grade serous ovarian cancer across the efficacy endpoints evaluated, with a response rate of 24% and a median PFS of 11.2 months on updated analysis. Chemotherapy responses were better than predicted, based on historical retrospective data,” said investigator Rachel N. Grisham, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The binimetinib trial and the trametinib trial were both discussed during a webinar on rare tumors covering research slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chemoresistant cancers

Low-grade serous ovarian or peritoneal cancers are rare, accounting for only 5% to 10% of all serous cancers, Dr. Gershenson noted.

“[Low-grade serous cancers are] characterized by alterations in the MAP kinase pathway, as well as relative chemoresistance, and prolonged overall survival compared to high-grade serous cancers. Because of this subtype’s relative chemoresistance, the search for novel therapeutics has predominated over the last decade or so,” he said.

MEK inhibitors interfere with the MEK1 and MEK2 enzymes in the MAPK pathway. Alterations in MAPK, especially in KRAS and BRAF proteins, are found in 30%-60% of low-grade serous carcinomas, providing the rationale for MEK inhibitors in these rare malignancies.

Trametinib study

In a phase 2/3 study, Dr. Gershenson and colleagues enrolled 260 patients with recurrent, low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Patients were randomized to receive either trametinib at 2 mg daily continuously until progression (n = 130) or standard care (n = 130).

Standard care consisted of one of the following: letrozole at 2.5 mg daily; pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40-50 mg IV every 28 days; weekly paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 for 3 out of 4 weeks; tamoxifen at 20 mg twice daily; or topotecan at 4 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. Patients randomized to standard care could be crossed over to trametinib at progression.

All patients had at least one prior line of platinum-based chemotherapy, and nearly half had three or more prior lines of therapy. The median age was 56.6 years in the trametinib arm and 55.3 years in the control arm.

At a median follow-up of 31.4 months, median PFS, the primary endpoint, was 13 months with trametinib vs. 7.2 months with standard care. The hazard ratio (HR) for progression on trametinib was 0.48 (P < .0001).

The overall response rates were 26.2% in the trametinib arm and 6.2% in the standard care arm. The odds ratio for response on trametinib was 5.4 (P < .0001).

For 88 patients who crossed over to trametinib, the median PFS was 10.8 months, and the overall response rate was 15%.

Trametinib was also associated with a significantly longer response duration, at a median of 13.6 months, compared with 5.9 months for standard care (P value not shown).

The median overall survival was 37 months with trametinib and 29.2 months with standard care, with an HR favoring trametinib of 0.75, although this just missed statistical significance (P = .054). Dr. Gershenson pointed out that the overall survival in the standard care arm included patients who had been crossed over to trametinib.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events included hematologic toxicities in 13.4% of patients on trametinib and 9.4% on standard care; gastrointestinal toxicity in 27.6% and 29%, respectively; skin toxicities in 15% and 3.9%, respectively; and vascular toxicities in 18.9% and 8.6%, respectively.

Binimetinib study

The phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 study enrolled 341 patients with low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum. Patients were randomized on a 2:1 basis to receive either binimetinib at 45 mg twice daily (n = 228) or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (n = 113). Chemotherapy consisted of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40 mg/m2 on day 1 of each 28-day cycle; paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle; or topotecan at 1.25 mg/m2 IV on days 1-5 of each 21-day cycle.

The efficacy analysis included 227 patients assigned to binimetinib and 106 assigned to chemotherapy.

A planned interim analysis was performed in 2016 after the first 303 patients were enrolled. At that time, the median PFS by blinded central review was 9.1 months in the binimetinib arm and 10.6 months in the physician’s choice arm (HR, 1.21; P = .807), so the trial was halted early for futility. Patients on active treatment at the time could continue until progression and were followed by local radiology.

At the interim analysis, secondary endpoints were also similar between the arms. The overall response rate was 16% in the binimetinib arm and 13% in the chemotherapy arm.

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events with binimetinib were blood creatinine phosphokinase increase (26%) and vomiting (10%).

Dr. Grisham also reported updated follow-up results through January 2019.

The median PFS in the updated analysis was 11.2 months with the MEK inhibitor and 14.1 months with chemotherapy, a difference that was not statistically significant (HR, 1.12; P = .752). Updated overall response rates were the same in both arms, at 24%.

A post hoc molecular analysis of 215 patients suggested a possible association between KRAS mutation and response to binimetinib.

Two MEKs, one ‘meh’

Discussant Jubilee Brown, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that “with a 2% to 5% chance of response in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer, there is a low bar for any compound to demonstrate success.”

Regarding the MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, she noted that “this study did not meet its primary endpoint, but perhaps the endpoint is not reflective of the importance of the study.”

A different outcome might have occurred had investigators stratified patients by KRAS status upfront, comparing patients with KRAS mutations treated with binimetinib to KRAS wild-type patients treated with either a MEK inhibitor or physician’s choice of care, Dr. Brown said.

She agreed with the assertion by Dr. Gershenson and colleagues that improved PFS qualifies trametinib to be considered a new option for standard care, ”especially in a rare tumor setting with limited options. This is a huge win for patients.”

The trametinib study was sponsored by NRG Oncology and the UK National Cancer Research Institute. Dr. Gershenson disclosed relationships with NRG Oncology, Genentech, Novartis, Elsevier, and UpToDate, as well as stock in several companies.

The binimetinib study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Grisham disclosed relationships with Clovis, Regeneron, Mateon, Amgen, Abbvie, OncLive, PRIME, MCM, and Medscape. MDedge News and Medscape are owned by the same parent organization.

Dr. Brown disclosed consulting for Biodesix, Caris, Clovis, Genentech, Invitae, Janssen, Olympus, OncLive, and Tempus.

SOURCE: Gershenson DM et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 42; Grisham RN et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 41.

Two MEK inhibitors were tested against recurrent low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum, but only one inhibitor offered clinical benefit over standard care, investigators from two randomized trials reported.

Trametinib improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with standard care, while binimetinib conferred no PFS benefit.

In a phase 2/3 trial, the median PFS was 13 months for patients treated with trametinib and 7.2 months for patients who received an aromatase inhibitor or chemotherapy (P < .0001).

“Our findings suggest that trametinib represents a new standard-of-care treatment option for women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma,” said investigator David M. Gershenson, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

In contrast, in the phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, there was no significant difference in PFS between patients treated with binimetinib and those who received physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median PFS was 11.2 months with binimetinib and 14.1 months with chemotherapy (P = .752).

“Although this study did not meet its primary endpoint, binimetinib showed activity in low-grade serous ovarian cancer across the efficacy endpoints evaluated, with a response rate of 24% and a median PFS of 11.2 months on updated analysis. Chemotherapy responses were better than predicted, based on historical retrospective data,” said investigator Rachel N. Grisham, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The binimetinib trial and the trametinib trial were both discussed during a webinar on rare tumors covering research slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chemoresistant cancers

Low-grade serous ovarian or peritoneal cancers are rare, accounting for only 5% to 10% of all serous cancers, Dr. Gershenson noted.

“[Low-grade serous cancers are] characterized by alterations in the MAP kinase pathway, as well as relative chemoresistance, and prolonged overall survival compared to high-grade serous cancers. Because of this subtype’s relative chemoresistance, the search for novel therapeutics has predominated over the last decade or so,” he said.

MEK inhibitors interfere with the MEK1 and MEK2 enzymes in the MAPK pathway. Alterations in MAPK, especially in KRAS and BRAF proteins, are found in 30%-60% of low-grade serous carcinomas, providing the rationale for MEK inhibitors in these rare malignancies.

Trametinib study

In a phase 2/3 study, Dr. Gershenson and colleagues enrolled 260 patients with recurrent, low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Patients were randomized to receive either trametinib at 2 mg daily continuously until progression (n = 130) or standard care (n = 130).

Standard care consisted of one of the following: letrozole at 2.5 mg daily; pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40-50 mg IV every 28 days; weekly paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 for 3 out of 4 weeks; tamoxifen at 20 mg twice daily; or topotecan at 4 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. Patients randomized to standard care could be crossed over to trametinib at progression.

All patients had at least one prior line of platinum-based chemotherapy, and nearly half had three or more prior lines of therapy. The median age was 56.6 years in the trametinib arm and 55.3 years in the control arm.

At a median follow-up of 31.4 months, median PFS, the primary endpoint, was 13 months with trametinib vs. 7.2 months with standard care. The hazard ratio (HR) for progression on trametinib was 0.48 (P < .0001).

The overall response rates were 26.2% in the trametinib arm and 6.2% in the standard care arm. The odds ratio for response on trametinib was 5.4 (P < .0001).

For 88 patients who crossed over to trametinib, the median PFS was 10.8 months, and the overall response rate was 15%.

Trametinib was also associated with a significantly longer response duration, at a median of 13.6 months, compared with 5.9 months for standard care (P value not shown).

The median overall survival was 37 months with trametinib and 29.2 months with standard care, with an HR favoring trametinib of 0.75, although this just missed statistical significance (P = .054). Dr. Gershenson pointed out that the overall survival in the standard care arm included patients who had been crossed over to trametinib.

Grade 3 or greater adverse events included hematologic toxicities in 13.4% of patients on trametinib and 9.4% on standard care; gastrointestinal toxicity in 27.6% and 29%, respectively; skin toxicities in 15% and 3.9%, respectively; and vascular toxicities in 18.9% and 8.6%, respectively.

Binimetinib study

The phase 3 MILO/ENGOT-ov11 study enrolled 341 patients with low-grade serous carcinomas of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum. Patients were randomized on a 2:1 basis to receive either binimetinib at 45 mg twice daily (n = 228) or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (n = 113). Chemotherapy consisted of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin at 40 mg/m2 on day 1 of each 28-day cycle; paclitaxel at 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle; or topotecan at 1.25 mg/m2 IV on days 1-5 of each 21-day cycle.

The efficacy analysis included 227 patients assigned to binimetinib and 106 assigned to chemotherapy.

A planned interim analysis was performed in 2016 after the first 303 patients were enrolled. At that time, the median PFS by blinded central review was 9.1 months in the binimetinib arm and 10.6 months in the physician’s choice arm (HR, 1.21; P = .807), so the trial was halted early for futility. Patients on active treatment at the time could continue until progression and were followed by local radiology.

At the interim analysis, secondary endpoints were also similar between the arms. The overall response rate was 16% in the binimetinib arm and 13% in the chemotherapy arm.

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events with binimetinib were blood creatinine phosphokinase increase (26%) and vomiting (10%).

Dr. Grisham also reported updated follow-up results through January 2019.

The median PFS in the updated analysis was 11.2 months with the MEK inhibitor and 14.1 months with chemotherapy, a difference that was not statistically significant (HR, 1.12; P = .752). Updated overall response rates were the same in both arms, at 24%.

A post hoc molecular analysis of 215 patients suggested a possible association between KRAS mutation and response to binimetinib.

Two MEKs, one ‘meh’

Discussant Jubilee Brown, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that “with a 2% to 5% chance of response in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer, there is a low bar for any compound to demonstrate success.”

Regarding the MILO/ENGOT-ov11 trial, she noted that “this study did not meet its primary endpoint, but perhaps the endpoint is not reflective of the importance of the study.”

A different outcome might have occurred had investigators stratified patients by KRAS status upfront, comparing patients with KRAS mutations treated with binimetinib to KRAS wild-type patients treated with either a MEK inhibitor or physician’s choice of care, Dr. Brown said.

She agreed with the assertion by Dr. Gershenson and colleagues that improved PFS qualifies trametinib to be considered a new option for standard care, ”especially in a rare tumor setting with limited options. This is a huge win for patients.”

The trametinib study was sponsored by NRG Oncology and the UK National Cancer Research Institute. Dr. Gershenson disclosed relationships with NRG Oncology, Genentech, Novartis, Elsevier, and UpToDate, as well as stock in several companies.

The binimetinib study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Grisham disclosed relationships with Clovis, Regeneron, Mateon, Amgen, Abbvie, OncLive, PRIME, MCM, and Medscape. MDedge News and Medscape are owned by the same parent organization.

Dr. Brown disclosed consulting for Biodesix, Caris, Clovis, Genentech, Invitae, Janssen, Olympus, OncLive, and Tempus.

SOURCE: Gershenson DM et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 42; Grisham RN et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 41.

FROM SGO 2020

FDA approves olaparib/bevacizumab maintenance

The Food and Drug Administration has announced a new approved indication for olaparib (Lynparza) in adults with advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.

Olaparib is now FDA-approved for use in combination with bevacizumab as maintenance therapy in patients who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and whose cancer is homologous recombination deficiency positive, as defined by a deleterious or suspected deleterious BRCA mutation and/or genomic instability.

The FDA also approved the Myriad myChoice CDx test as a companion diagnostic for olaparib.

Trial results

The efficacy of olaparib and the myChoice CDx test were assessed in patients in the phase 3 PAOLA-1 trial (NCT02477644). The study enrolled patients with advanced high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who had received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab.

Patients were stratified by first-line treatment outcome and BRCA mutation status, as determined by prospective local testing. All available clinical samples were retrospectively tested with the Myriad myChoice CDx test.

The patients were randomized to receive olaparib at 300 mg orally twice daily in combination with bevacizumab at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks (n = 537) or placebo plus bevacizumab (n = 269). Patients continued bevacizumab in the maintenance setting and started olaparib 3-9 weeks after their last chemotherapy dose. Olaparib could be continued for up to 2 years or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The median progression-free survival among the 387 patients with homologous recombination deficiency-positive tumors was 37.2 months in the olaparib arm and 17.7 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.33), according to the prescribing information for olaparib.

Serious adverse events occurred in 31% of patients in the olaparib arm. The most common were hypertension (19%) and anemia (17%).

Dose interruptions from adverse events occurred in 54% of patients in the olaparib arm, and dose reductions from adverse events occurred in 41%.

The Food and Drug Administration has announced a new approved indication for olaparib (Lynparza) in adults with advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.

Olaparib is now FDA-approved for use in combination with bevacizumab as maintenance therapy in patients who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and whose cancer is homologous recombination deficiency positive, as defined by a deleterious or suspected deleterious BRCA mutation and/or genomic instability.

The FDA also approved the Myriad myChoice CDx test as a companion diagnostic for olaparib.

Trial results

The efficacy of olaparib and the myChoice CDx test were assessed in patients in the phase 3 PAOLA-1 trial (NCT02477644). The study enrolled patients with advanced high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who had received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab.

Patients were stratified by first-line treatment outcome and BRCA mutation status, as determined by prospective local testing. All available clinical samples were retrospectively tested with the Myriad myChoice CDx test.

The patients were randomized to receive olaparib at 300 mg orally twice daily in combination with bevacizumab at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks (n = 537) or placebo plus bevacizumab (n = 269). Patients continued bevacizumab in the maintenance setting and started olaparib 3-9 weeks after their last chemotherapy dose. Olaparib could be continued for up to 2 years or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The median progression-free survival among the 387 patients with homologous recombination deficiency-positive tumors was 37.2 months in the olaparib arm and 17.7 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.33), according to the prescribing information for olaparib.

Serious adverse events occurred in 31% of patients in the olaparib arm. The most common were hypertension (19%) and anemia (17%).

Dose interruptions from adverse events occurred in 54% of patients in the olaparib arm, and dose reductions from adverse events occurred in 41%.

The Food and Drug Administration has announced a new approved indication for olaparib (Lynparza) in adults with advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.

Olaparib is now FDA-approved for use in combination with bevacizumab as maintenance therapy in patients who responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and whose cancer is homologous recombination deficiency positive, as defined by a deleterious or suspected deleterious BRCA mutation and/or genomic instability.

The FDA also approved the Myriad myChoice CDx test as a companion diagnostic for olaparib.

Trial results

The efficacy of olaparib and the myChoice CDx test were assessed in patients in the phase 3 PAOLA-1 trial (NCT02477644). The study enrolled patients with advanced high-grade epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who had received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab.

Patients were stratified by first-line treatment outcome and BRCA mutation status, as determined by prospective local testing. All available clinical samples were retrospectively tested with the Myriad myChoice CDx test.

The patients were randomized to receive olaparib at 300 mg orally twice daily in combination with bevacizumab at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks (n = 537) or placebo plus bevacizumab (n = 269). Patients continued bevacizumab in the maintenance setting and started olaparib 3-9 weeks after their last chemotherapy dose. Olaparib could be continued for up to 2 years or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The median progression-free survival among the 387 patients with homologous recombination deficiency-positive tumors was 37.2 months in the olaparib arm and 17.7 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.33), according to the prescribing information for olaparib.

Serious adverse events occurred in 31% of patients in the olaparib arm. The most common were hypertension (19%) and anemia (17%).

Dose interruptions from adverse events occurred in 54% of patients in the olaparib arm, and dose reductions from adverse events occurred in 41%.

ASCO goes ahead online, as conference center is used as hospital

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaccine maintenance improves relapse-free survival in BRCA wild-type ovarian cancer

The autologous tumor cell vaccine gemogenovatucel-T (Vigil Ovarian) is well tolerated as maintenance therapy in stage III-IV ovarian cancer patients and may improve relapse-free survival, particularly in BRCA wild-type disease, according to findings from the ongoing VITAL study.

In patients with and without BRCA1/2 mutations, the median relapse-free survival was longer with gemogenovatucel-T maintenance than with placebo, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .065).

However, among patients with wild-type BRCA, the median relapse-free survival was significantly longer with gemogenovatucel-T (P = .0007).

Rodney P. Rocconi, MD, of the Mitchell Cancer Institute at University of South Alabama, Mobile, reported these results in an abstract that was slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancers. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some data have been updated from the abstract.

Study rationale

Gemogenovatucel-T (formerly called FANG) is an autologous tumor cell vaccine transfected with a plasmid encoding granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor and a novel bifunctional short hairpin interfering RNA targeting furin convertase.

“In the era of personalized, targeted medicine, I think this is about as personalized as you can get, this type of vaccine,” Dr. Rocconi said. “Essentially, we harvest patients’ own cancer cells and create a vaccine that is targeted to the antigens on their cells so that it recognizes only that patient’s cancer.”

The vaccine also helps recruit immune cells to the area and has a very limited off-target effect, Dr. Rocconi added.

He noted that gemogenovatucel-T previously demonstrated promising efficacy and limited side effects in a phase 1 study that included patients with advanced ovarian cancer (Mol Ther. 2012 Mar;20[3]:679-86).

“So we thought that, in ovarian cancer, as a maintenance therapy, it made a lot of sense,” Dr. Rocconi said, noting that the overall prognosis for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer remains limited.

Treatment and toxicity

Dr. Rocconi and colleagues reported data on 91 patients in the VITAL study. The patients had achieved a complete response after frontline surgery and chemotherapy, and they were randomized to maintenance with gemogenovatucel-T or placebo.

Patients had a median time from surgery to randomization of 208.5 days in the gemogenovatucel-T group and 200 days in the control group. The patients were treated with 1 x 107 cells/mL of gemogenovatucel-T or placebo intradermally once a month for up to 12 doses.

Gemogenovatucel-T was well tolerated. No added overall toxicity was noted in the gemogenovatucel-T group versus the control group, and no grade 4/5 toxicities were observed, Dr. Rocconi said. Grade 2/3 toxic events were observed in 8% of patients in the gemogenovatucel-T group, compared with 18% in the control group. The most common events were nausea and musculoskeletal pain in the gemogenovatucel-T group, and were bone pain and fatigue in the control group.

Relapse-free and overall survival

In the entire cohort, the median relapse-free survival was longer with gemogenovatucel-T maintenance – 12.6 months versus 8.4 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.69) – but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .065).

However, in the 67 patients with wild-type BRCA, the median relapse-free survival was 19.4 months with gemogenovatucel-T and 14.8 months with placebo, a statistically significant difference (HR, 0.459; P = .0007).

The median overall survival was not reached in the BRCA wild-type patients treated with gemogenovatucel-T, and it was 41.4 months from the time of randomization in those who received placebo (HR, 0.417; P = .02).

No benefit was seen with gemogenovatucel-T in patients with known BRCA1/2 mutations, Dr. Rocconi said.

‘Encouraging’ results

The overall improvement in the gemogenovatucel-T group was encouraging, particularly in a maintenance-type trial, Dr. Rocconi said. He noted that prior treatments for maintenance have received approval based on shorter survival gains, and the finding of particular benefit in BRCA wild-type disease could have important implications for a population that usually has lesser benefit from treatments, compared with patients who have BRCA mutations.

“So this result is very unique,” Dr. Rocconi said, explaining that about 85% of ovarian cancer patients have BRCA wild-type disease; with this treatment, patients with wild-type BRCA may achieve similar survival rates as those seen in BRCA-mutant disease.

“I think, in general, immunotherapy has been somewhat disappointing in ovarian cancer, so to have a targeted vaccine work in ovarian cancer, just broadly ... is pretty noteworthy,” he said. “We’re really excited, obviously, about the overall success we’ve seen for all patients, but most importantly in those with BRCA wild type. This is a pretty marked significance in recurrence-free intervals and overall survival, and we’re definitely pleased with that.”

Next steps

The findings from this trial have been submitted for publication, and efforts are underway to determine next steps through communication with the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Rocconi said.

Additionally, other studies are underway to assess gemogenovatucel-T in patients who fall in “the middle ground” – that is, patients who have BRCA wild-type disease but have “some homologous recombination deficiency where the tumor itself might be BRCA deficient or have some other type of deficiency,” Dr. Rocconi explained.

“So we’re trying to tease out specifically what is going on across all the different variations of ovarian cancer patients, and also looking for potential biomarkers for predicting response,” he said. “What we would like to see is a companion test where we’re able to predict which patients can really respond and do best with this technology, and, that way, we know how to stratify patients most appropriately.”

The current trial was sponsored by Gradalis. Dr. Rocconi disclosed relationships with Gradalis, Genentech, Clovis, and Johnson & Johnson.

SOURCE: Rocconi RP et al. SGO 2020, Abstract LBA7.

The autologous tumor cell vaccine gemogenovatucel-T (Vigil Ovarian) is well tolerated as maintenance therapy in stage III-IV ovarian cancer patients and may improve relapse-free survival, particularly in BRCA wild-type disease, according to findings from the ongoing VITAL study.

In patients with and without BRCA1/2 mutations, the median relapse-free survival was longer with gemogenovatucel-T maintenance than with placebo, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .065).

However, among patients with wild-type BRCA, the median relapse-free survival was significantly longer with gemogenovatucel-T (P = .0007).

Rodney P. Rocconi, MD, of the Mitchell Cancer Institute at University of South Alabama, Mobile, reported these results in an abstract that was slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancers. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some data have been updated from the abstract.

Study rationale

Gemogenovatucel-T (formerly called FANG) is an autologous tumor cell vaccine transfected with a plasmid encoding granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor and a novel bifunctional short hairpin interfering RNA targeting furin convertase.

“In the era of personalized, targeted medicine, I think this is about as personalized as you can get, this type of vaccine,” Dr. Rocconi said. “Essentially, we harvest patients’ own cancer cells and create a vaccine that is targeted to the antigens on their cells so that it recognizes only that patient’s cancer.”

The vaccine also helps recruit immune cells to the area and has a very limited off-target effect, Dr. Rocconi added.

He noted that gemogenovatucel-T previously demonstrated promising efficacy and limited side effects in a phase 1 study that included patients with advanced ovarian cancer (Mol Ther. 2012 Mar;20[3]:679-86).

“So we thought that, in ovarian cancer, as a maintenance therapy, it made a lot of sense,” Dr. Rocconi said, noting that the overall prognosis for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer remains limited.

Treatment and toxicity

Dr. Rocconi and colleagues reported data on 91 patients in the VITAL study. The patients had achieved a complete response after frontline surgery and chemotherapy, and they were randomized to maintenance with gemogenovatucel-T or placebo.

Patients had a median time from surgery to randomization of 208.5 days in the gemogenovatucel-T group and 200 days in the control group. The patients were treated with 1 x 107 cells/mL of gemogenovatucel-T or placebo intradermally once a month for up to 12 doses.

Gemogenovatucel-T was well tolerated. No added overall toxicity was noted in the gemogenovatucel-T group versus the control group, and no grade 4/5 toxicities were observed, Dr. Rocconi said. Grade 2/3 toxic events were observed in 8% of patients in the gemogenovatucel-T group, compared with 18% in the control group. The most common events were nausea and musculoskeletal pain in the gemogenovatucel-T group, and were bone pain and fatigue in the control group.

Relapse-free and overall survival

In the entire cohort, the median relapse-free survival was longer with gemogenovatucel-T maintenance – 12.6 months versus 8.4 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.69) – but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .065).

However, in the 67 patients with wild-type BRCA, the median relapse-free survival was 19.4 months with gemogenovatucel-T and 14.8 months with placebo, a statistically significant difference (HR, 0.459; P = .0007).

The median overall survival was not reached in the BRCA wild-type patients treated with gemogenovatucel-T, and it was 41.4 months from the time of randomization in those who received placebo (HR, 0.417; P = .02).

No benefit was seen with gemogenovatucel-T in patients with known BRCA1/2 mutations, Dr. Rocconi said.

‘Encouraging’ results

The overall improvement in the gemogenovatucel-T group was encouraging, particularly in a maintenance-type trial, Dr. Rocconi said. He noted that prior treatments for maintenance have received approval based on shorter survival gains, and the finding of particular benefit in BRCA wild-type disease could have important implications for a population that usually has lesser benefit from treatments, compared with patients who have BRCA mutations.

“So this result is very unique,” Dr. Rocconi said, explaining that about 85% of ovarian cancer patients have BRCA wild-type disease; with this treatment, patients with wild-type BRCA may achieve similar survival rates as those seen in BRCA-mutant disease.

“I think, in general, immunotherapy has been somewhat disappointing in ovarian cancer, so to have a targeted vaccine work in ovarian cancer, just broadly ... is pretty noteworthy,” he said. “We’re really excited, obviously, about the overall success we’ve seen for all patients, but most importantly in those with BRCA wild type. This is a pretty marked significance in recurrence-free intervals and overall survival, and we’re definitely pleased with that.”

Next steps

The findings from this trial have been submitted for publication, and efforts are underway to determine next steps through communication with the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Rocconi said.

Additionally, other studies are underway to assess gemogenovatucel-T in patients who fall in “the middle ground” – that is, patients who have BRCA wild-type disease but have “some homologous recombination deficiency where the tumor itself might be BRCA deficient or have some other type of deficiency,” Dr. Rocconi explained.

“So we’re trying to tease out specifically what is going on across all the different variations of ovarian cancer patients, and also looking for potential biomarkers for predicting response,” he said. “What we would like to see is a companion test where we’re able to predict which patients can really respond and do best with this technology, and, that way, we know how to stratify patients most appropriately.”

The current trial was sponsored by Gradalis. Dr. Rocconi disclosed relationships with Gradalis, Genentech, Clovis, and Johnson & Johnson.

SOURCE: Rocconi RP et al. SGO 2020, Abstract LBA7.

The autologous tumor cell vaccine gemogenovatucel-T (Vigil Ovarian) is well tolerated as maintenance therapy in stage III-IV ovarian cancer patients and may improve relapse-free survival, particularly in BRCA wild-type disease, according to findings from the ongoing VITAL study.

In patients with and without BRCA1/2 mutations, the median relapse-free survival was longer with gemogenovatucel-T maintenance than with placebo, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .065).

However, among patients with wild-type BRCA, the median relapse-free survival was significantly longer with gemogenovatucel-T (P = .0007).

Rodney P. Rocconi, MD, of the Mitchell Cancer Institute at University of South Alabama, Mobile, reported these results in an abstract that was slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancers. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some data have been updated from the abstract.

Study rationale

Gemogenovatucel-T (formerly called FANG) is an autologous tumor cell vaccine transfected with a plasmid encoding granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor and a novel bifunctional short hairpin interfering RNA targeting furin convertase.

“In the era of personalized, targeted medicine, I think this is about as personalized as you can get, this type of vaccine,” Dr. Rocconi said. “Essentially, we harvest patients’ own cancer cells and create a vaccine that is targeted to the antigens on their cells so that it recognizes only that patient’s cancer.”

The vaccine also helps recruit immune cells to the area and has a very limited off-target effect, Dr. Rocconi added.

He noted that gemogenovatucel-T previously demonstrated promising efficacy and limited side effects in a phase 1 study that included patients with advanced ovarian cancer (Mol Ther. 2012 Mar;20[3]:679-86).

“So we thought that, in ovarian cancer, as a maintenance therapy, it made a lot of sense,” Dr. Rocconi said, noting that the overall prognosis for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer remains limited.

Treatment and toxicity

Dr. Rocconi and colleagues reported data on 91 patients in the VITAL study. The patients had achieved a complete response after frontline surgery and chemotherapy, and they were randomized to maintenance with gemogenovatucel-T or placebo.

Patients had a median time from surgery to randomization of 208.5 days in the gemogenovatucel-T group and 200 days in the control group. The patients were treated with 1 x 107 cells/mL of gemogenovatucel-T or placebo intradermally once a month for up to 12 doses.

Gemogenovatucel-T was well tolerated. No added overall toxicity was noted in the gemogenovatucel-T group versus the control group, and no grade 4/5 toxicities were observed, Dr. Rocconi said. Grade 2/3 toxic events were observed in 8% of patients in the gemogenovatucel-T group, compared with 18% in the control group. The most common events were nausea and musculoskeletal pain in the gemogenovatucel-T group, and were bone pain and fatigue in the control group.

Relapse-free and overall survival

In the entire cohort, the median relapse-free survival was longer with gemogenovatucel-T maintenance – 12.6 months versus 8.4 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.69) – but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .065).

However, in the 67 patients with wild-type BRCA, the median relapse-free survival was 19.4 months with gemogenovatucel-T and 14.8 months with placebo, a statistically significant difference (HR, 0.459; P = .0007).

The median overall survival was not reached in the BRCA wild-type patients treated with gemogenovatucel-T, and it was 41.4 months from the time of randomization in those who received placebo (HR, 0.417; P = .02).

No benefit was seen with gemogenovatucel-T in patients with known BRCA1/2 mutations, Dr. Rocconi said.

‘Encouraging’ results

The overall improvement in the gemogenovatucel-T group was encouraging, particularly in a maintenance-type trial, Dr. Rocconi said. He noted that prior treatments for maintenance have received approval based on shorter survival gains, and the finding of particular benefit in BRCA wild-type disease could have important implications for a population that usually has lesser benefit from treatments, compared with patients who have BRCA mutations.

“So this result is very unique,” Dr. Rocconi said, explaining that about 85% of ovarian cancer patients have BRCA wild-type disease; with this treatment, patients with wild-type BRCA may achieve similar survival rates as those seen in BRCA-mutant disease.

“I think, in general, immunotherapy has been somewhat disappointing in ovarian cancer, so to have a targeted vaccine work in ovarian cancer, just broadly ... is pretty noteworthy,” he said. “We’re really excited, obviously, about the overall success we’ve seen for all patients, but most importantly in those with BRCA wild type. This is a pretty marked significance in recurrence-free intervals and overall survival, and we’re definitely pleased with that.”

Next steps

The findings from this trial have been submitted for publication, and efforts are underway to determine next steps through communication with the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Rocconi said.

Additionally, other studies are underway to assess gemogenovatucel-T in patients who fall in “the middle ground” – that is, patients who have BRCA wild-type disease but have “some homologous recombination deficiency where the tumor itself might be BRCA deficient or have some other type of deficiency,” Dr. Rocconi explained.

“So we’re trying to tease out specifically what is going on across all the different variations of ovarian cancer patients, and also looking for potential biomarkers for predicting response,” he said. “What we would like to see is a companion test where we’re able to predict which patients can really respond and do best with this technology, and, that way, we know how to stratify patients most appropriately.”

The current trial was sponsored by Gradalis. Dr. Rocconi disclosed relationships with Gradalis, Genentech, Clovis, and Johnson & Johnson.

SOURCE: Rocconi RP et al. SGO 2020, Abstract LBA7.

FROM SGO 2020

COVID-19 death rate was twice as high in cancer patients in NYC study

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

FROM CANCER DISCOVERY

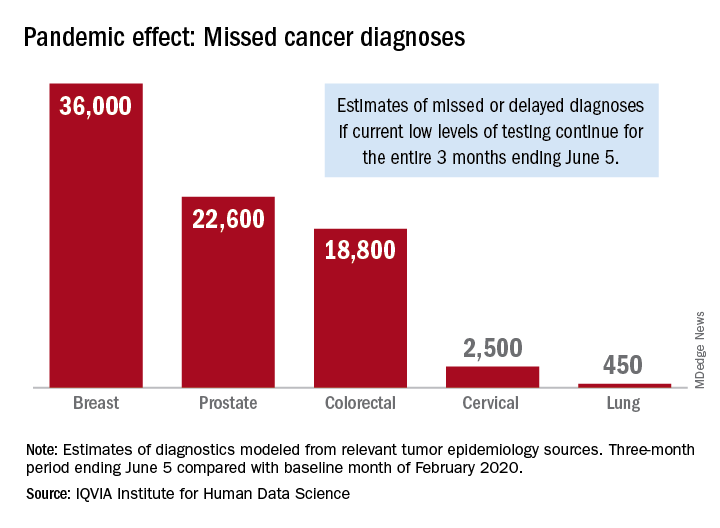

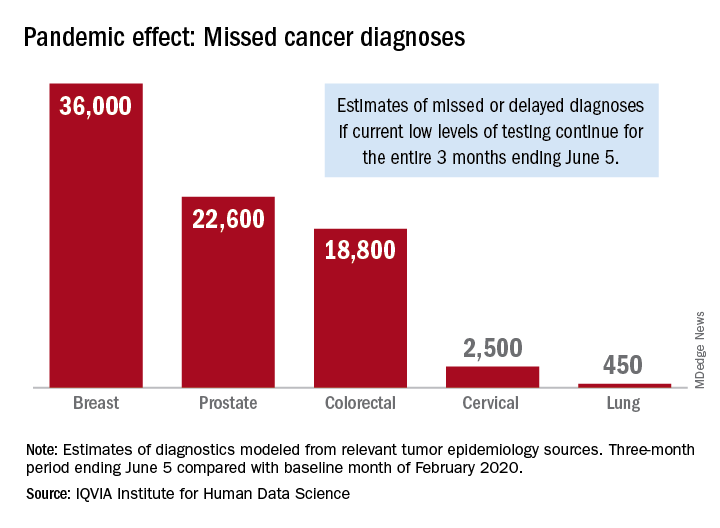

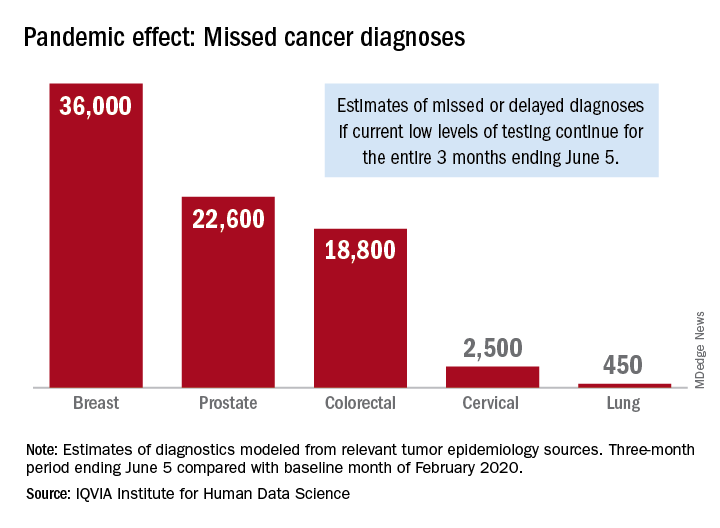

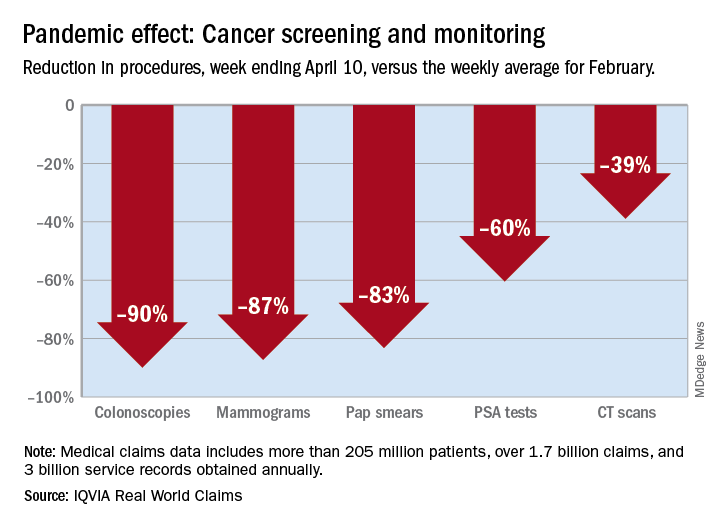

Three months of COVID-19 may mean 80,000 missed cancer diagnoses

, according to a report by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science looking at trends in the United States.