User login

Complete resection tied to improved survival in low-grade serous ovarian cancer

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Surgical resection to the point of no residual macroscopic disease significantly improved survival among patients with low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, based on the findings of a large multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Adjuvant platinum-based therapy, however, did not appear to boost survival in the analysis, Tamayaa May, MD, MSc, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “Genotyping and targeted sequencing of low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma often identifies actionable mutations, and treatment with MEK-based combination therapy might be a viable therapeutic strategy in patients with KRAS or NRAS mutations,” added Dr. May of Princess Margaret Cancer Center at the University of Toronto. She and her associates plan to examine more subgroups to determine if genomic alterations predict systemic response, she said.

Low-grade (Silverberg grade 1) serous ovarian tumors are slow growing but tend to resist chemotherapy, making optimal debulking a crucial part of treatment. In past studies, debulking that eliminated macroscopic evidence of disease was associated with a median survival time of about 115 months, compared with about 43 months if patients had residual disease, Dr. May noted.

To further explore outcomes after surgical resection, and to help clarify the role of systemic platinum-based therapy in low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, she and her associates analyzed clinical data from 714 patients with low-grade serous ovarian carcinomas, including 40 from her institution and 674 from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium Registry. Most (60%) patients had stage III disease at diagnosis.

Complete data on surgical outcomes were available for 382 patients, of whom 202 (53%) had residual macroscopic disease and 43% did not. Among 439 patients with complete treatment data, 170 (39%) received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. For the 391 patients with complete data on progression-free survival (PFS), the median follow-up was 4.9 years and median PFS was 3.1 years (95% confidence interval, 2.6-4.5 years). Residual macroscopic disease correlated with shorter PFS (P less than .001), as did higher tumor stage and baseline CA125 (P less than .001), but platinum-based therapy did not (P = .1).

A multivariable analysis of 333 patients confirmed these findings, Dr. May said. Independent correlates of death or disease progression included residual macroscopic disease (hazard ratio, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.68-3.37; P less than .001), older age (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.30; P = .02), and stage III (HR, 3.28; 95% CI, 1.87-5.76; P less than .001) or stage IV disease (HR, 5.68; 95% CI, 2.73-11.83; P less than .001), compared with stage I disease. In contrast, platinum-based therapy did not correlate with survival (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69-1.28; P = .69).

The overall survival analysis also linked mortality with higher tumor stage, increased baseline CA125, and residual disease (P less than .001 for each association), but not with platinum-based therapy (P = .2). The multivariable analysis independently tied mortality to older age (HR, 1.25; P less than .001), stage III (HR, 2.31; P = .006) or IV disease (HR, 3.86; P less than .001), and residual disease (HR, 2.53; P less than .001), but not to platinum-based therapy (HR, 1.05; P = .77).

Data consistency and completeness were issues in this study: most notably, 45% of patients had no PFS data, Dr. May commented. Nonetheless, this type of large retrospective multicenter analysis is one of the best ways to study rare tumors, including low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, she said.

The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund provides financial support for OCAC. Dr. May reported having no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Surgical resection to the point of no residual macroscopic disease significantly improved survival among patients with low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, based on the findings of a large multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Adjuvant platinum-based therapy, however, did not appear to boost survival in the analysis, Tamayaa May, MD, MSc, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “Genotyping and targeted sequencing of low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma often identifies actionable mutations, and treatment with MEK-based combination therapy might be a viable therapeutic strategy in patients with KRAS or NRAS mutations,” added Dr. May of Princess Margaret Cancer Center at the University of Toronto. She and her associates plan to examine more subgroups to determine if genomic alterations predict systemic response, she said.

Low-grade (Silverberg grade 1) serous ovarian tumors are slow growing but tend to resist chemotherapy, making optimal debulking a crucial part of treatment. In past studies, debulking that eliminated macroscopic evidence of disease was associated with a median survival time of about 115 months, compared with about 43 months if patients had residual disease, Dr. May noted.

To further explore outcomes after surgical resection, and to help clarify the role of systemic platinum-based therapy in low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, she and her associates analyzed clinical data from 714 patients with low-grade serous ovarian carcinomas, including 40 from her institution and 674 from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium Registry. Most (60%) patients had stage III disease at diagnosis.

Complete data on surgical outcomes were available for 382 patients, of whom 202 (53%) had residual macroscopic disease and 43% did not. Among 439 patients with complete treatment data, 170 (39%) received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. For the 391 patients with complete data on progression-free survival (PFS), the median follow-up was 4.9 years and median PFS was 3.1 years (95% confidence interval, 2.6-4.5 years). Residual macroscopic disease correlated with shorter PFS (P less than .001), as did higher tumor stage and baseline CA125 (P less than .001), but platinum-based therapy did not (P = .1).

A multivariable analysis of 333 patients confirmed these findings, Dr. May said. Independent correlates of death or disease progression included residual macroscopic disease (hazard ratio, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.68-3.37; P less than .001), older age (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.30; P = .02), and stage III (HR, 3.28; 95% CI, 1.87-5.76; P less than .001) or stage IV disease (HR, 5.68; 95% CI, 2.73-11.83; P less than .001), compared with stage I disease. In contrast, platinum-based therapy did not correlate with survival (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69-1.28; P = .69).

The overall survival analysis also linked mortality with higher tumor stage, increased baseline CA125, and residual disease (P less than .001 for each association), but not with platinum-based therapy (P = .2). The multivariable analysis independently tied mortality to older age (HR, 1.25; P less than .001), stage III (HR, 2.31; P = .006) or IV disease (HR, 3.86; P less than .001), and residual disease (HR, 2.53; P less than .001), but not to platinum-based therapy (HR, 1.05; P = .77).

Data consistency and completeness were issues in this study: most notably, 45% of patients had no PFS data, Dr. May commented. Nonetheless, this type of large retrospective multicenter analysis is one of the best ways to study rare tumors, including low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, she said.

The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund provides financial support for OCAC. Dr. May reported having no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Surgical resection to the point of no residual macroscopic disease significantly improved survival among patients with low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, based on the findings of a large multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Adjuvant platinum-based therapy, however, did not appear to boost survival in the analysis, Tamayaa May, MD, MSc, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “Genotyping and targeted sequencing of low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma often identifies actionable mutations, and treatment with MEK-based combination therapy might be a viable therapeutic strategy in patients with KRAS or NRAS mutations,” added Dr. May of Princess Margaret Cancer Center at the University of Toronto. She and her associates plan to examine more subgroups to determine if genomic alterations predict systemic response, she said.

Low-grade (Silverberg grade 1) serous ovarian tumors are slow growing but tend to resist chemotherapy, making optimal debulking a crucial part of treatment. In past studies, debulking that eliminated macroscopic evidence of disease was associated with a median survival time of about 115 months, compared with about 43 months if patients had residual disease, Dr. May noted.

To further explore outcomes after surgical resection, and to help clarify the role of systemic platinum-based therapy in low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, she and her associates analyzed clinical data from 714 patients with low-grade serous ovarian carcinomas, including 40 from her institution and 674 from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium Registry. Most (60%) patients had stage III disease at diagnosis.

Complete data on surgical outcomes were available for 382 patients, of whom 202 (53%) had residual macroscopic disease and 43% did not. Among 439 patients with complete treatment data, 170 (39%) received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. For the 391 patients with complete data on progression-free survival (PFS), the median follow-up was 4.9 years and median PFS was 3.1 years (95% confidence interval, 2.6-4.5 years). Residual macroscopic disease correlated with shorter PFS (P less than .001), as did higher tumor stage and baseline CA125 (P less than .001), but platinum-based therapy did not (P = .1).

A multivariable analysis of 333 patients confirmed these findings, Dr. May said. Independent correlates of death or disease progression included residual macroscopic disease (hazard ratio, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.68-3.37; P less than .001), older age (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.30; P = .02), and stage III (HR, 3.28; 95% CI, 1.87-5.76; P less than .001) or stage IV disease (HR, 5.68; 95% CI, 2.73-11.83; P less than .001), compared with stage I disease. In contrast, platinum-based therapy did not correlate with survival (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.69-1.28; P = .69).

The overall survival analysis also linked mortality with higher tumor stage, increased baseline CA125, and residual disease (P less than .001 for each association), but not with platinum-based therapy (P = .2). The multivariable analysis independently tied mortality to older age (HR, 1.25; P less than .001), stage III (HR, 2.31; P = .006) or IV disease (HR, 3.86; P less than .001), and residual disease (HR, 2.53; P less than .001), but not to platinum-based therapy (HR, 1.05; P = .77).

Data consistency and completeness were issues in this study: most notably, 45% of patients had no PFS data, Dr. May commented. Nonetheless, this type of large retrospective multicenter analysis is one of the best ways to study rare tumors, including low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, she said.

The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund provides financial support for OCAC. Dr. May reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Key clinical point: Unlike platinum-based chemotherapy, resection to the point of no residual disease was associated with improved survival among patients with low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma.

Major finding: Independent correlates of death or disease progression included residual macroscopic disease (hazard ratio, 2.38; P less than .001), older age (HR, 1.15; P = .02), and stage III (HR, 3.28; P less than .001) or stage IV (HR, 5.68; P less than .001) disease, compared with stage I disease. Platinum-based therapy was not associated with improved survival (HR, 0.94; P = 69).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 714 patients with low-grade (Silverberg grade 1) serous tumors from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium Registry.

Disclosures: The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund provides financial support for OCAC. Dr. May reported having no conflicts of interest.

VIDEO: Pain and impaired QOL persist after open endometrial cancer surgery

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Patient-reported outcomes from a prospective cohort study of minimally invasive versus open surgery for women with endometrial cancer showed that the disability from open surgery persisted for longer than had previously been recognized. Further, for a subset of patients, impairment in sexual functioning was significant, and persistent, regardless of the type of surgery.

At 3 weeks after surgery, patients who had open surgery had greater pain as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory (minimally important difference greater than 1, P = .0004). By 3 months post surgery, responses on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General were still significantly lower for the open-surgery group, compared with the minimally invasive group (P = .0011).

Although patients’ pain and overall state of health were better at 3 weeks post surgery, regardless of whether women had open, laparoscopic, or robotic surgery, the reduced overall quality of life experienced by patients who had open surgery persisted.

“What was a bit different from other studies … is that we found that this is maintained even at 3 months, and it was clinically and statistically different,” Sarah Ferguson, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “So that was really, I think, an interesting finding, that this doesn’t just impact the very short term. Three months is a fairly long time after a primary surgery, and [it’s] important for women to know this.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Patients in the eight-center study had histologically confirmed clinical stage I or II endometrial cancer. The open-surgery arm of the study involved 106 patients, and 414 had minimally invasive surgery (168 laparascopic, 246 robotic).

The robotic and laparoscopic arms showed no statistically significant differences for any patient-reported outcome, even after adjusting for potentially confounding variables, said Dr. Ferguson of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre at the University of Toronto. Accordingly, investigators compared both minimally invasive arms grouped together against open surgery.

Overall, about 80% of patients completed the quality-of-life questionnaires. The response rate for the sexual-functioning questionnaires, however, was much lower, ranging from about a quarter to a half of the participants.

When Dr. Ferguson and her colleagues examined the characteristics of the patients who did complete the sexual-functioning questionnaires, they found that these women were more likely to be younger, partnered, premenopausal and sexually active at the time of diagnosis. Both of the surgical groups “met the clinical cutoff for sexual dysfunction” on the Female Sexual Function Index questionnaire, she said.

For the sexual function questionnaires, differences between the open and minimally invasive groups were not significant at any time point throughout the 26 weeks that patients were studied. “Though it’s a small population, I think these results are important,” said Dr. Ferguson. “These variables may be helpful for us to target patients in our practice, or in future studies, who require intervention.”

Though the study was not randomized, Dr. Ferguson said that the baseline characteristics were similar between groups, and the investigators’ intention-to-treat analysis used a statistical model that adjusted for many potential confounding variables.

Dr. Ferguson reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Patient-reported outcomes from a prospective cohort study of minimally invasive versus open surgery for women with endometrial cancer showed that the disability from open surgery persisted for longer than had previously been recognized. Further, for a subset of patients, impairment in sexual functioning was significant, and persistent, regardless of the type of surgery.

At 3 weeks after surgery, patients who had open surgery had greater pain as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory (minimally important difference greater than 1, P = .0004). By 3 months post surgery, responses on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General were still significantly lower for the open-surgery group, compared with the minimally invasive group (P = .0011).

Although patients’ pain and overall state of health were better at 3 weeks post surgery, regardless of whether women had open, laparoscopic, or robotic surgery, the reduced overall quality of life experienced by patients who had open surgery persisted.

“What was a bit different from other studies … is that we found that this is maintained even at 3 months, and it was clinically and statistically different,” Sarah Ferguson, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “So that was really, I think, an interesting finding, that this doesn’t just impact the very short term. Three months is a fairly long time after a primary surgery, and [it’s] important for women to know this.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Patients in the eight-center study had histologically confirmed clinical stage I or II endometrial cancer. The open-surgery arm of the study involved 106 patients, and 414 had minimally invasive surgery (168 laparascopic, 246 robotic).

The robotic and laparoscopic arms showed no statistically significant differences for any patient-reported outcome, even after adjusting for potentially confounding variables, said Dr. Ferguson of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre at the University of Toronto. Accordingly, investigators compared both minimally invasive arms grouped together against open surgery.

Overall, about 80% of patients completed the quality-of-life questionnaires. The response rate for the sexual-functioning questionnaires, however, was much lower, ranging from about a quarter to a half of the participants.

When Dr. Ferguson and her colleagues examined the characteristics of the patients who did complete the sexual-functioning questionnaires, they found that these women were more likely to be younger, partnered, premenopausal and sexually active at the time of diagnosis. Both of the surgical groups “met the clinical cutoff for sexual dysfunction” on the Female Sexual Function Index questionnaire, she said.

For the sexual function questionnaires, differences between the open and minimally invasive groups were not significant at any time point throughout the 26 weeks that patients were studied. “Though it’s a small population, I think these results are important,” said Dr. Ferguson. “These variables may be helpful for us to target patients in our practice, or in future studies, who require intervention.”

Though the study was not randomized, Dr. Ferguson said that the baseline characteristics were similar between groups, and the investigators’ intention-to-treat analysis used a statistical model that adjusted for many potential confounding variables.

Dr. Ferguson reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Patient-reported outcomes from a prospective cohort study of minimally invasive versus open surgery for women with endometrial cancer showed that the disability from open surgery persisted for longer than had previously been recognized. Further, for a subset of patients, impairment in sexual functioning was significant, and persistent, regardless of the type of surgery.

At 3 weeks after surgery, patients who had open surgery had greater pain as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory (minimally important difference greater than 1, P = .0004). By 3 months post surgery, responses on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General were still significantly lower for the open-surgery group, compared with the minimally invasive group (P = .0011).

Although patients’ pain and overall state of health were better at 3 weeks post surgery, regardless of whether women had open, laparoscopic, or robotic surgery, the reduced overall quality of life experienced by patients who had open surgery persisted.

“What was a bit different from other studies … is that we found that this is maintained even at 3 months, and it was clinically and statistically different,” Sarah Ferguson, MD, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “So that was really, I think, an interesting finding, that this doesn’t just impact the very short term. Three months is a fairly long time after a primary surgery, and [it’s] important for women to know this.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Patients in the eight-center study had histologically confirmed clinical stage I or II endometrial cancer. The open-surgery arm of the study involved 106 patients, and 414 had minimally invasive surgery (168 laparascopic, 246 robotic).

The robotic and laparoscopic arms showed no statistically significant differences for any patient-reported outcome, even after adjusting for potentially confounding variables, said Dr. Ferguson of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre at the University of Toronto. Accordingly, investigators compared both minimally invasive arms grouped together against open surgery.

Overall, about 80% of patients completed the quality-of-life questionnaires. The response rate for the sexual-functioning questionnaires, however, was much lower, ranging from about a quarter to a half of the participants.

When Dr. Ferguson and her colleagues examined the characteristics of the patients who did complete the sexual-functioning questionnaires, they found that these women were more likely to be younger, partnered, premenopausal and sexually active at the time of diagnosis. Both of the surgical groups “met the clinical cutoff for sexual dysfunction” on the Female Sexual Function Index questionnaire, she said.

For the sexual function questionnaires, differences between the open and minimally invasive groups were not significant at any time point throughout the 26 weeks that patients were studied. “Though it’s a small population, I think these results are important,” said Dr. Ferguson. “These variables may be helpful for us to target patients in our practice, or in future studies, who require intervention.”

Though the study was not randomized, Dr. Ferguson said that the baseline characteristics were similar between groups, and the investigators’ intention-to-treat analysis used a statistical model that adjusted for many potential confounding variables.

Dr. Ferguson reported having no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN'S CANCER

Isolated tumor cells did not predict progression in endometrial cancer

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Patients with endometrial cancer should not receive adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy solely because they have isolated tumor cells in their sentinel lymph nodes, Marie Plante, MD, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

In a single-center prospective cohort study, about 96% of patients with endometrial cancer were alive and progression free at 3 years, a rate which resembles those reported for node-negative patients, said Dr. Plante of Laval University, Quebec City. Moreover, all 10 patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy remained alive and progression free during follow-up, she said. “Patients with isolated tumor cells carry an excellent prognosis,” she added. “Adjuvant treatment should be tailored based on uterine factors and histology and not solely on the presence of isolated tumor cells in sentinel lymph nodes.”

Pathologic ultrastaging has boosted the detection of low-volume metastases, which comprise anywhere from 35% to 63% of nodal metastases in patients with endometrial cancer. Clinicians continue to debate management when this low-volume disease consists of isolated tumor cells (ITC), defined as fewer than 200 carcinoma cells found singly or in small clusters. Finding ITC in endometrial cancer is uncommon, and few studies have examined this subgroup, Dr. Plante noted.

She and her associates evaluated 519 patients who underwent hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, lymphadenectomy, or sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer at their center between 2010 and 2015. Pathologic ultrastaging identified 31 patients with ITC (6%), of whom 11 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, 14 received pelvic radiation therapy, and 10 underwent only brachytherapy or observation, with some patients receiving more than one treatment. Another 54 patients in the cohort had metastatic disease, including 43 patients with macrometastasis and 11 with micrometastasis.

Stage, not treatment, predicted progression-free survival (PFS), Dr. Plante emphasized. After a median follow-up period of 29 months, the estimated 3-year rate of PFS was significantly better among patients with ITC (96%), node-negative disease (88%), or micrometastasis (86%) than among those with macrometastasis (59%; P = .001), even though macrometastasis patients received significantly more chemotherapy (P = .0001).

Rates of PFS did not statistically differ between the ITC and node-negative groups, Dr. Plante noted. The single recurrence in an ITC patient involved a 7 cm carcinosarcoma that recurred despite adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. There were no recurrences among patients with endometrioid histology.

Among ITC patients who received no adjuvant treatment, half had stage IA endometrial cancer and half were stage IB, half were grade 1 and half were grade 2, all had endometrioid histology, and seven (70%) had evidence of lymphovascular space invasion, Dr. Plante said. All remained alive and progression free at follow-up.

Ultrastaging should only be performed if a sentinel lymph node is negative on initial hematoxylin and eosin stain and if there is myoinvasion, commented Nadeem R. Abu-Rustum, MD, chief of the gynecology service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who was not involved in the study. “Ultrastaging increases positive-node detection by about 8%,” he said during the scientific plenary session at the conference. “Finding positive nodes can change management, and we have to be careful not to overtreat.”

Ongoing research is examining the topography and anatomic location of ITC in sentinel lymph nodes, Dr. Abu-Rustum said. In the meantime, he advised clinicians to consider any ultrastaging result of ITC in context. “When modeling the risk of ITCs, don’t look at them in isolation. Don’t be ‘node-centric,’ ” he advised. “Look at the uterine factors and the overall bigger picture.”

Dr. Plante did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Plante and Dr. Abu-Rustum reported having no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Patients with endometrial cancer should not receive adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy solely because they have isolated tumor cells in their sentinel lymph nodes, Marie Plante, MD, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

In a single-center prospective cohort study, about 96% of patients with endometrial cancer were alive and progression free at 3 years, a rate which resembles those reported for node-negative patients, said Dr. Plante of Laval University, Quebec City. Moreover, all 10 patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy remained alive and progression free during follow-up, she said. “Patients with isolated tumor cells carry an excellent prognosis,” she added. “Adjuvant treatment should be tailored based on uterine factors and histology and not solely on the presence of isolated tumor cells in sentinel lymph nodes.”

Pathologic ultrastaging has boosted the detection of low-volume metastases, which comprise anywhere from 35% to 63% of nodal metastases in patients with endometrial cancer. Clinicians continue to debate management when this low-volume disease consists of isolated tumor cells (ITC), defined as fewer than 200 carcinoma cells found singly or in small clusters. Finding ITC in endometrial cancer is uncommon, and few studies have examined this subgroup, Dr. Plante noted.

She and her associates evaluated 519 patients who underwent hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, lymphadenectomy, or sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer at their center between 2010 and 2015. Pathologic ultrastaging identified 31 patients with ITC (6%), of whom 11 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, 14 received pelvic radiation therapy, and 10 underwent only brachytherapy or observation, with some patients receiving more than one treatment. Another 54 patients in the cohort had metastatic disease, including 43 patients with macrometastasis and 11 with micrometastasis.

Stage, not treatment, predicted progression-free survival (PFS), Dr. Plante emphasized. After a median follow-up period of 29 months, the estimated 3-year rate of PFS was significantly better among patients with ITC (96%), node-negative disease (88%), or micrometastasis (86%) than among those with macrometastasis (59%; P = .001), even though macrometastasis patients received significantly more chemotherapy (P = .0001).

Rates of PFS did not statistically differ between the ITC and node-negative groups, Dr. Plante noted. The single recurrence in an ITC patient involved a 7 cm carcinosarcoma that recurred despite adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. There were no recurrences among patients with endometrioid histology.

Among ITC patients who received no adjuvant treatment, half had stage IA endometrial cancer and half were stage IB, half were grade 1 and half were grade 2, all had endometrioid histology, and seven (70%) had evidence of lymphovascular space invasion, Dr. Plante said. All remained alive and progression free at follow-up.

Ultrastaging should only be performed if a sentinel lymph node is negative on initial hematoxylin and eosin stain and if there is myoinvasion, commented Nadeem R. Abu-Rustum, MD, chief of the gynecology service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who was not involved in the study. “Ultrastaging increases positive-node detection by about 8%,” he said during the scientific plenary session at the conference. “Finding positive nodes can change management, and we have to be careful not to overtreat.”

Ongoing research is examining the topography and anatomic location of ITC in sentinel lymph nodes, Dr. Abu-Rustum said. In the meantime, he advised clinicians to consider any ultrastaging result of ITC in context. “When modeling the risk of ITCs, don’t look at them in isolation. Don’t be ‘node-centric,’ ” he advised. “Look at the uterine factors and the overall bigger picture.”

Dr. Plante did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Plante and Dr. Abu-Rustum reported having no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Patients with endometrial cancer should not receive adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy solely because they have isolated tumor cells in their sentinel lymph nodes, Marie Plante, MD, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

In a single-center prospective cohort study, about 96% of patients with endometrial cancer were alive and progression free at 3 years, a rate which resembles those reported for node-negative patients, said Dr. Plante of Laval University, Quebec City. Moreover, all 10 patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy remained alive and progression free during follow-up, she said. “Patients with isolated tumor cells carry an excellent prognosis,” she added. “Adjuvant treatment should be tailored based on uterine factors and histology and not solely on the presence of isolated tumor cells in sentinel lymph nodes.”

Pathologic ultrastaging has boosted the detection of low-volume metastases, which comprise anywhere from 35% to 63% of nodal metastases in patients with endometrial cancer. Clinicians continue to debate management when this low-volume disease consists of isolated tumor cells (ITC), defined as fewer than 200 carcinoma cells found singly or in small clusters. Finding ITC in endometrial cancer is uncommon, and few studies have examined this subgroup, Dr. Plante noted.

She and her associates evaluated 519 patients who underwent hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, lymphadenectomy, or sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer at their center between 2010 and 2015. Pathologic ultrastaging identified 31 patients with ITC (6%), of whom 11 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, 14 received pelvic radiation therapy, and 10 underwent only brachytherapy or observation, with some patients receiving more than one treatment. Another 54 patients in the cohort had metastatic disease, including 43 patients with macrometastasis and 11 with micrometastasis.

Stage, not treatment, predicted progression-free survival (PFS), Dr. Plante emphasized. After a median follow-up period of 29 months, the estimated 3-year rate of PFS was significantly better among patients with ITC (96%), node-negative disease (88%), or micrometastasis (86%) than among those with macrometastasis (59%; P = .001), even though macrometastasis patients received significantly more chemotherapy (P = .0001).

Rates of PFS did not statistically differ between the ITC and node-negative groups, Dr. Plante noted. The single recurrence in an ITC patient involved a 7 cm carcinosarcoma that recurred despite adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. There were no recurrences among patients with endometrioid histology.

Among ITC patients who received no adjuvant treatment, half had stage IA endometrial cancer and half were stage IB, half were grade 1 and half were grade 2, all had endometrioid histology, and seven (70%) had evidence of lymphovascular space invasion, Dr. Plante said. All remained alive and progression free at follow-up.

Ultrastaging should only be performed if a sentinel lymph node is negative on initial hematoxylin and eosin stain and if there is myoinvasion, commented Nadeem R. Abu-Rustum, MD, chief of the gynecology service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who was not involved in the study. “Ultrastaging increases positive-node detection by about 8%,” he said during the scientific plenary session at the conference. “Finding positive nodes can change management, and we have to be careful not to overtreat.”

Ongoing research is examining the topography and anatomic location of ITC in sentinel lymph nodes, Dr. Abu-Rustum said. In the meantime, he advised clinicians to consider any ultrastaging result of ITC in context. “When modeling the risk of ITCs, don’t look at them in isolation. Don’t be ‘node-centric,’ ” he advised. “Look at the uterine factors and the overall bigger picture.”

Dr. Plante did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Plante and Dr. Abu-Rustum reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Key clinical point: For patients with endometrial cancer, isolated tumor cells in sentinel lymph nodes did not lead to disease progression and were not an indication for adjuvant treatments.

Major finding: At 3 years, the estimated rate of progression-free survival was 100% among patients who underwent only pelvic brachytherapy or observation.

Data source: A single-center prospective study of 519 patients undergoing hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, lymphadenectomy, and sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer, including 31 patients with isolated tumor cells identified in sentinel lymph nodes.

Disclosures: Dr. Plante did not report having external funding sources. Dr. Plante and Dr. Abu-Rustum had no disclosures.

Postoperative pain in women with preexisting chronic pain

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

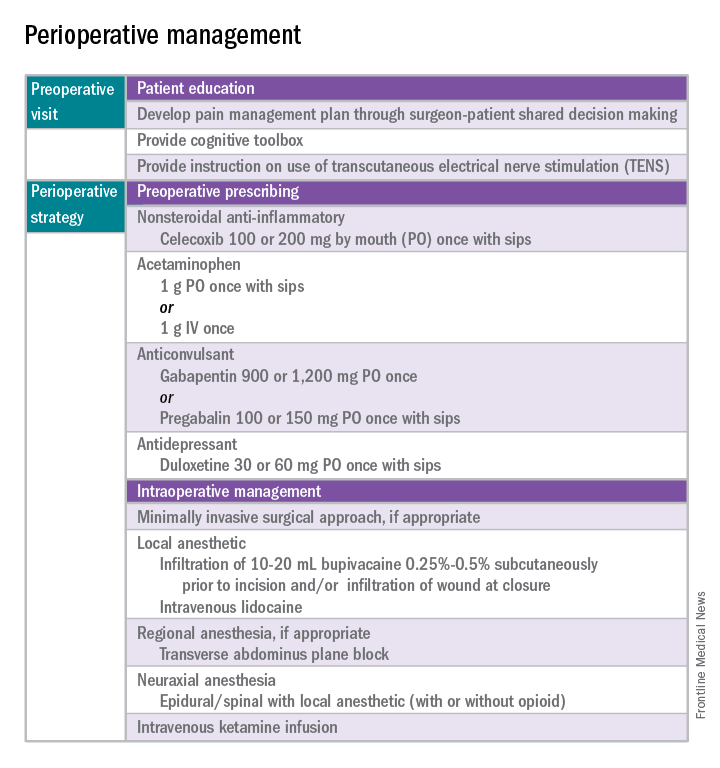

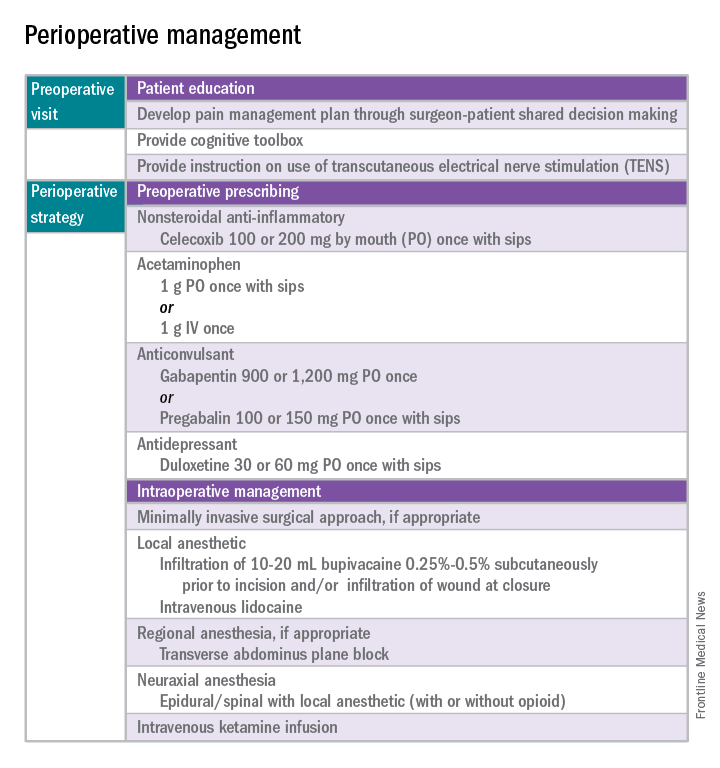

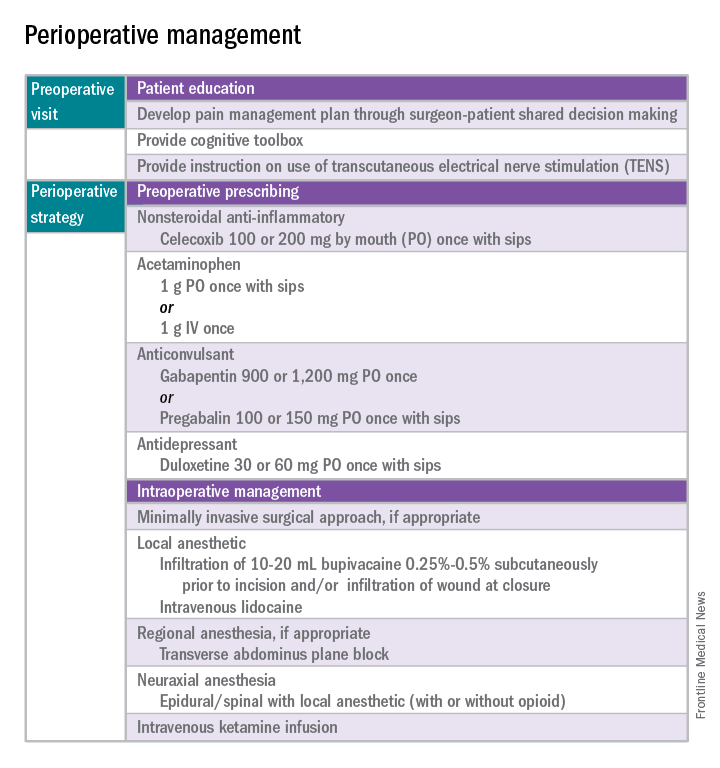

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

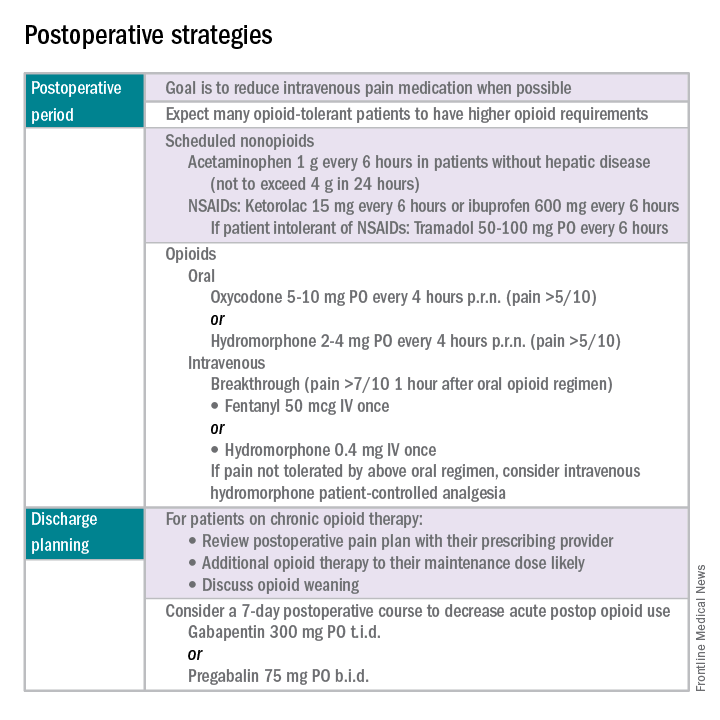

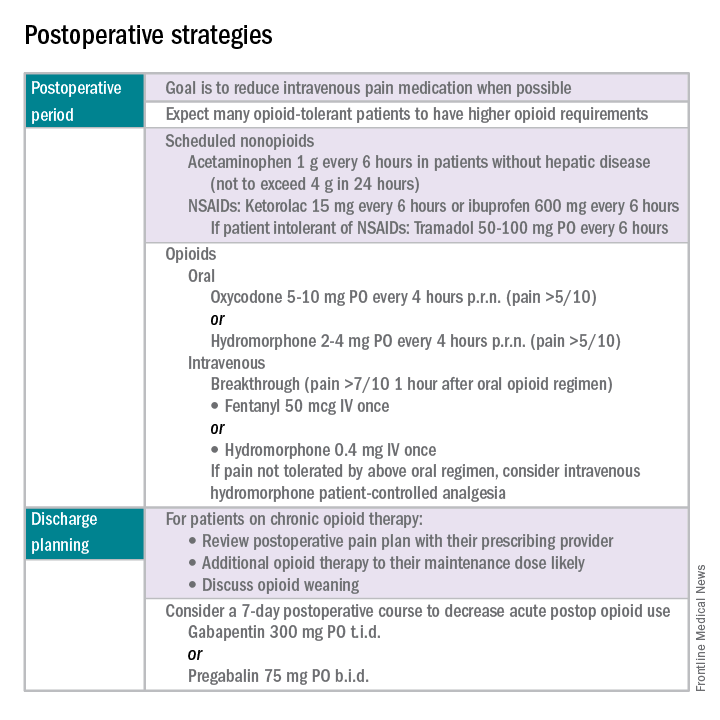

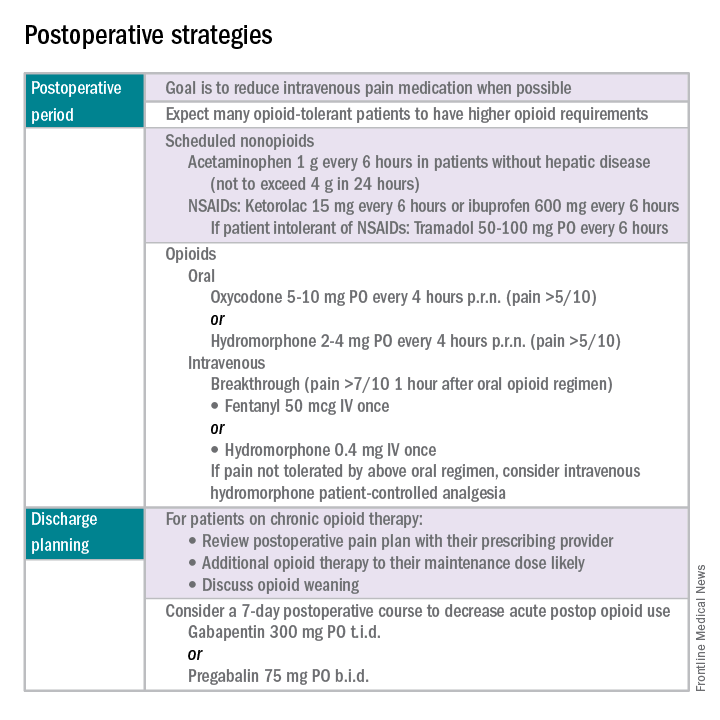

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Vascular surgeons underutilize palliative care planning

Investment in advanced palliative care planning has the potential to improve the quality of care for vascular surgery patients, according to investigators from Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Dale G. Wilson, MD, and his colleagues performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records for 111 patients, who died while on the vascular surgery service at the OHSU Hospital during 2005-2014.

Almost three-quarters (73%) of patients were transitioned to palliative care; of those, 14% presented with an advanced directive, and 28% received a palliative care consultation (JAMA Surg. 2017;152[2]:183-90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3970).

While palliative care services are increasing in hospitals, accounting for 4% of annual hospital admissions in 2012 according to the study, they are not implemented consistently. “Many teams from various specialties care for patients at end of life; however, we still do not know what prompts end-of-life discussions,” Dr. Wilson said. “There is still no consensus on when to involve palliative services in the care of critically ill patients.”

While the decision to advise a consultation is “variable and physician dependent,” the type of treatment required may help identify when consultations are appropriate.

Of the 14 patients who did not choose comfort care, 11 (79%) required CPR. Additionally, all had to be taken to the operating room and required mechanical ventilation.

Of 81 patients who chose palliative care, 31 did so despite potential medical options. These patients were older – average age, 77 years, as compared with 68 years for patients who did not choose comfort care – with 8 of the 31 (26%) presenting an advanced directive, compared with only 7 of 83 patients (8%) for those who did not receive palliative care.

Dr. Wilson and his colleagues found that patients who chose palliative care were more likely to have received a palliative care consultation, as well: 10 of 31 patients who chose comfort care received a consultation, as opposed to 1 of 83 who chose comfort care but did not receive a consultation.

The nature of the vascular surgery service calls for early efforts to gather information regarding patients’ views on end-of-life care, Dr. Wilson said, noting that 73% of patients studied were admitted emergently and 87% underwent surgery, leaving little time for patients to express their wishes.

“Because the events associated with withdrawal of care are often not anticipated, we argue that all vascular surgical patients should have an advance directive, and perhaps, those at particular high risk should have a preoperative palliative care consultation,” Dr. Wilson wrote.

Limitations to the study included the data abstraction, which was performed by a single unblinded physician. Researchers also gathered patients’ reasons for transitioning to comfort care retrospectively.

The low rate of palliative care consultations found in this study mirrors my own experience, as does the feeling of urgency to shed more light on the issue. The biggest hurdle surgeons face when it comes to palliative care consultations is that, in their minds, seeking these meetings is associated with immediate death care. Many surgeons are shy about bringing palliative care specialists on board because approaching families can be daunting.

Family members who do not know enough about comfort care can be upset by the idea. Addressing this misunderstanding is crucial. Consultations are not just conversations about hospice care but can be emotional and spiritual experiences that prepare both the family and the patient for alternative options when surgical intervention cannot guarantee a good quality of life. I would encourage surgeons to be more proactive and less defensive about comfort care . Luckily, understanding the importance of this issue among professionals is growing.

When I approach these situations, it’s important for me to have a full understanding of what families and patients usually expect. Decisions should not be based on how bad things are now but on the future. What was the patient’s last year like? What is the best-case scenario for moving forward on a proposed intervention? What will the patient’s quality of life be? Answering these questions helps the patient understand his or her situation, without diminishing a surgeon’s ability. If you are honest, the family will usually come to the conclusion that they do not want to subject the patient to ultimately unnecessary treatment.

Palliative care services help patients and their families deal with pain beyond the physical symptoms. Dealing with pain, depression, or delirium is only a part of comfort care – coping with a sense of hopelessness, family disruption, or feelings of guilt also can be a part and, significantly, a part that surgeons are not trained to diagnose or treat.

With more than 70 surgeons certified in hospice care and a growing number of fellowships in palliative care, I am extremely optimistic in the progress we have made and will continue to make.

Geoffrey Dunn, MD, FACS, is the medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at UPMC Hamot Medical Center, Erie, Penn. He currently is Community Editor for the Pain and Palliative Care Community for the ACS’s web portal.

The low rate of palliative care consultations found in this study mirrors my own experience, as does the feeling of urgency to shed more light on the issue. The biggest hurdle surgeons face when it comes to palliative care consultations is that, in their minds, seeking these meetings is associated with immediate death care. Many surgeons are shy about bringing palliative care specialists on board because approaching families can be daunting.

Family members who do not know enough about comfort care can be upset by the idea. Addressing this misunderstanding is crucial. Consultations are not just conversations about hospice care but can be emotional and spiritual experiences that prepare both the family and the patient for alternative options when surgical intervention cannot guarantee a good quality of life. I would encourage surgeons to be more proactive and less defensive about comfort care . Luckily, understanding the importance of this issue among professionals is growing.

When I approach these situations, it’s important for me to have a full understanding of what families and patients usually expect. Decisions should not be based on how bad things are now but on the future. What was the patient’s last year like? What is the best-case scenario for moving forward on a proposed intervention? What will the patient’s quality of life be? Answering these questions helps the patient understand his or her situation, without diminishing a surgeon’s ability. If you are honest, the family will usually come to the conclusion that they do not want to subject the patient to ultimately unnecessary treatment.

Palliative care services help patients and their families deal with pain beyond the physical symptoms. Dealing with pain, depression, or delirium is only a part of comfort care – coping with a sense of hopelessness, family disruption, or feelings of guilt also can be a part and, significantly, a part that surgeons are not trained to diagnose or treat.

With more than 70 surgeons certified in hospice care and a growing number of fellowships in palliative care, I am extremely optimistic in the progress we have made and will continue to make.

Geoffrey Dunn, MD, FACS, is the medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at UPMC Hamot Medical Center, Erie, Penn. He currently is Community Editor for the Pain and Palliative Care Community for the ACS’s web portal.

The low rate of palliative care consultations found in this study mirrors my own experience, as does the feeling of urgency to shed more light on the issue. The biggest hurdle surgeons face when it comes to palliative care consultations is that, in their minds, seeking these meetings is associated with immediate death care. Many surgeons are shy about bringing palliative care specialists on board because approaching families can be daunting.

Family members who do not know enough about comfort care can be upset by the idea. Addressing this misunderstanding is crucial. Consultations are not just conversations about hospice care but can be emotional and spiritual experiences that prepare both the family and the patient for alternative options when surgical intervention cannot guarantee a good quality of life. I would encourage surgeons to be more proactive and less defensive about comfort care . Luckily, understanding the importance of this issue among professionals is growing.

When I approach these situations, it’s important for me to have a full understanding of what families and patients usually expect. Decisions should not be based on how bad things are now but on the future. What was the patient’s last year like? What is the best-case scenario for moving forward on a proposed intervention? What will the patient’s quality of life be? Answering these questions helps the patient understand his or her situation, without diminishing a surgeon’s ability. If you are honest, the family will usually come to the conclusion that they do not want to subject the patient to ultimately unnecessary treatment.

Palliative care services help patients and their families deal with pain beyond the physical symptoms. Dealing with pain, depression, or delirium is only a part of comfort care – coping with a sense of hopelessness, family disruption, or feelings of guilt also can be a part and, significantly, a part that surgeons are not trained to diagnose or treat.

With more than 70 surgeons certified in hospice care and a growing number of fellowships in palliative care, I am extremely optimistic in the progress we have made and will continue to make.

Geoffrey Dunn, MD, FACS, is the medical director of the Palliative Care Consultation Service at UPMC Hamot Medical Center, Erie, Penn. He currently is Community Editor for the Pain and Palliative Care Community for the ACS’s web portal.

Investment in advanced palliative care planning has the potential to improve the quality of care for vascular surgery patients, according to investigators from Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Dale G. Wilson, MD, and his colleagues performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records for 111 patients, who died while on the vascular surgery service at the OHSU Hospital during 2005-2014.

Almost three-quarters (73%) of patients were transitioned to palliative care; of those, 14% presented with an advanced directive, and 28% received a palliative care consultation (JAMA Surg. 2017;152[2]:183-90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3970).

While palliative care services are increasing in hospitals, accounting for 4% of annual hospital admissions in 2012 according to the study, they are not implemented consistently. “Many teams from various specialties care for patients at end of life; however, we still do not know what prompts end-of-life discussions,” Dr. Wilson said. “There is still no consensus on when to involve palliative services in the care of critically ill patients.”

While the decision to advise a consultation is “variable and physician dependent,” the type of treatment required may help identify when consultations are appropriate.

Of the 14 patients who did not choose comfort care, 11 (79%) required CPR. Additionally, all had to be taken to the operating room and required mechanical ventilation.

Of 81 patients who chose palliative care, 31 did so despite potential medical options. These patients were older – average age, 77 years, as compared with 68 years for patients who did not choose comfort care – with 8 of the 31 (26%) presenting an advanced directive, compared with only 7 of 83 patients (8%) for those who did not receive palliative care.

Dr. Wilson and his colleagues found that patients who chose palliative care were more likely to have received a palliative care consultation, as well: 10 of 31 patients who chose comfort care received a consultation, as opposed to 1 of 83 who chose comfort care but did not receive a consultation.

The nature of the vascular surgery service calls for early efforts to gather information regarding patients’ views on end-of-life care, Dr. Wilson said, noting that 73% of patients studied were admitted emergently and 87% underwent surgery, leaving little time for patients to express their wishes.

“Because the events associated with withdrawal of care are often not anticipated, we argue that all vascular surgical patients should have an advance directive, and perhaps, those at particular high risk should have a preoperative palliative care consultation,” Dr. Wilson wrote.

Limitations to the study included the data abstraction, which was performed by a single unblinded physician. Researchers also gathered patients’ reasons for transitioning to comfort care retrospectively.

Investment in advanced palliative care planning has the potential to improve the quality of care for vascular surgery patients, according to investigators from Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Dale G. Wilson, MD, and his colleagues performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records for 111 patients, who died while on the vascular surgery service at the OHSU Hospital during 2005-2014.

Almost three-quarters (73%) of patients were transitioned to palliative care; of those, 14% presented with an advanced directive, and 28% received a palliative care consultation (JAMA Surg. 2017;152[2]:183-90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3970).

While palliative care services are increasing in hospitals, accounting for 4% of annual hospital admissions in 2012 according to the study, they are not implemented consistently. “Many teams from various specialties care for patients at end of life; however, we still do not know what prompts end-of-life discussions,” Dr. Wilson said. “There is still no consensus on when to involve palliative services in the care of critically ill patients.”

While the decision to advise a consultation is “variable and physician dependent,” the type of treatment required may help identify when consultations are appropriate.

Of the 14 patients who did not choose comfort care, 11 (79%) required CPR. Additionally, all had to be taken to the operating room and required mechanical ventilation.

Of 81 patients who chose palliative care, 31 did so despite potential medical options. These patients were older – average age, 77 years, as compared with 68 years for patients who did not choose comfort care – with 8 of the 31 (26%) presenting an advanced directive, compared with only 7 of 83 patients (8%) for those who did not receive palliative care.

Dr. Wilson and his colleagues found that patients who chose palliative care were more likely to have received a palliative care consultation, as well: 10 of 31 patients who chose comfort care received a consultation, as opposed to 1 of 83 who chose comfort care but did not receive a consultation.

The nature of the vascular surgery service calls for early efforts to gather information regarding patients’ views on end-of-life care, Dr. Wilson said, noting that 73% of patients studied were admitted emergently and 87% underwent surgery, leaving little time for patients to express their wishes.

“Because the events associated with withdrawal of care are often not anticipated, we argue that all vascular surgical patients should have an advance directive, and perhaps, those at particular high risk should have a preoperative palliative care consultation,” Dr. Wilson wrote.

Limitations to the study included the data abstraction, which was performed by a single unblinded physician. Researchers also gathered patients’ reasons for transitioning to comfort care retrospectively.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the 111 patients studied, 81 died on palliative care, but only 15 presented an advanced directive.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of the records of patients aged 18-99 years who died in the vascular surgery service at Oregon Health and Science University Hospital from 2005-2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no financial disclosures.

Diagnostic laparoscopy identifies ovarian cancers amenable to PCS

For women with suspected advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, diagnostic laparoscopy can help to distinguish between patients who could benefit from primary cytoreductive surgery (PCS) and those who might have better outcomes with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval cytoreductive surgery, according to investigators in the Netherlands.

In a randomized controlled trial exploring whether initial diagnostic laparoscopy could spare some patients from undergoing futile PCS, the investigators found that only 10% of patients assigned to diagnostic laparoscopy prior to PCS underwent a subsequent futile laparotomy, defined as residual disease greater than 1 cm following surgery. In contrast, 39% of women assigned to primary PCS had disease that might have been better treated by chemotherapy and interval surgery,

“In women with a plan for PCS, these data suggest that performance of diagnostic laparoscopy first is reasonable and that if cytoreduction to [less than] 1 cm of residual disease seems feasible, to proceed with PCS,” wrote Marrije R. Buist, MD of Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, and colleagues.

Among women with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IIIC to IV epithelial ovarian cancer, survival depends largely on the ability of surgery to either completely remove disease, or to leave at best less than 1 cm of residual disease. However, aggressive surgery in patients with more extensive disease is associated with significant morbidities, the authors noted.

“If at PCS, extensive disease is present, surgery could be ceased, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy with interval surgery could be a good alternative treatment. Therefore, the identification of patients with extensive disease who are likely to have [more than] 1 cm of residual tumor after PCS, defined as a futile laparotomy, is important,” they wrote.

To test this idea, the investigators, from eight cancer centers in the Netherlands, enrolled 201 patients with suspected FIGO stage IIB ovarian cancer or higher, and randomly assigned them to undergo either initial diagnostic laparoscopy or PCS.

They found that 10 of the 102 patients (10%) assigned to diagnostic laparoscopy went on to undergo PCS that revealed residual disease greater than 1 cm, compared with 39 of the 99 patients (39%) assigned to PCS. This difference translated into a relative risk for futile laparotomy of 0.25 for diagnostic laparoscopy compared with PCS (P less than .001).

Only 3 (3%) patients in the diagnostic laparoscopy group went on to have both PCS and interval surgery, compared with 28 (28%) patients initially assigned to PCS (P less than .001).

The Dutch Organization for Health Research and Development supported the study. All but one coauthor reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

For women with suspected advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, diagnostic laparoscopy can help to distinguish between patients who could benefit from primary cytoreductive surgery (PCS) and those who might have better outcomes with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval cytoreductive surgery, according to investigators in the Netherlands.

In a randomized controlled trial exploring whether initial diagnostic laparoscopy could spare some patients from undergoing futile PCS, the investigators found that only 10% of patients assigned to diagnostic laparoscopy prior to PCS underwent a subsequent futile laparotomy, defined as residual disease greater than 1 cm following surgery. In contrast, 39% of women assigned to primary PCS had disease that might have been better treated by chemotherapy and interval surgery,

“In women with a plan for PCS, these data suggest that performance of diagnostic laparoscopy first is reasonable and that if cytoreduction to [less than] 1 cm of residual disease seems feasible, to proceed with PCS,” wrote Marrije R. Buist, MD of Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, and colleagues.

Among women with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IIIC to IV epithelial ovarian cancer, survival depends largely on the ability of surgery to either completely remove disease, or to leave at best less than 1 cm of residual disease. However, aggressive surgery in patients with more extensive disease is associated with significant morbidities, the authors noted.

“If at PCS, extensive disease is present, surgery could be ceased, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy with interval surgery could be a good alternative treatment. Therefore, the identification of patients with extensive disease who are likely to have [more than] 1 cm of residual tumor after PCS, defined as a futile laparotomy, is important,” they wrote.

To test this idea, the investigators, from eight cancer centers in the Netherlands, enrolled 201 patients with suspected FIGO stage IIB ovarian cancer or higher, and randomly assigned them to undergo either initial diagnostic laparoscopy or PCS.

They found that 10 of the 102 patients (10%) assigned to diagnostic laparoscopy went on to undergo PCS that revealed residual disease greater than 1 cm, compared with 39 of the 99 patients (39%) assigned to PCS. This difference translated into a relative risk for futile laparotomy of 0.25 for diagnostic laparoscopy compared with PCS (P less than .001).

Only 3 (3%) patients in the diagnostic laparoscopy group went on to have both PCS and interval surgery, compared with 28 (28%) patients initially assigned to PCS (P less than .001).

The Dutch Organization for Health Research and Development supported the study. All but one coauthor reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

For women with suspected advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, diagnostic laparoscopy can help to distinguish between patients who could benefit from primary cytoreductive surgery (PCS) and those who might have better outcomes with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and interval cytoreductive surgery, according to investigators in the Netherlands.

In a randomized controlled trial exploring whether initial diagnostic laparoscopy could spare some patients from undergoing futile PCS, the investigators found that only 10% of patients assigned to diagnostic laparoscopy prior to PCS underwent a subsequent futile laparotomy, defined as residual disease greater than 1 cm following surgery. In contrast, 39% of women assigned to primary PCS had disease that might have been better treated by chemotherapy and interval surgery,

“In women with a plan for PCS, these data suggest that performance of diagnostic laparoscopy first is reasonable and that if cytoreduction to [less than] 1 cm of residual disease seems feasible, to proceed with PCS,” wrote Marrije R. Buist, MD of Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, and colleagues.

Among women with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IIIC to IV epithelial ovarian cancer, survival depends largely on the ability of surgery to either completely remove disease, or to leave at best less than 1 cm of residual disease. However, aggressive surgery in patients with more extensive disease is associated with significant morbidities, the authors noted.

“If at PCS, extensive disease is present, surgery could be ceased, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy with interval surgery could be a good alternative treatment. Therefore, the identification of patients with extensive disease who are likely to have [more than] 1 cm of residual tumor after PCS, defined as a futile laparotomy, is important,” they wrote.

To test this idea, the investigators, from eight cancer centers in the Netherlands, enrolled 201 patients with suspected FIGO stage IIB ovarian cancer or higher, and randomly assigned them to undergo either initial diagnostic laparoscopy or PCS.