User login

Heart rate variability may help predict treatment response in chronic migraine

Key clinical point: Patients with chronic migraine have autonomic dysfunction, the extent of which is evaluated using heart rate variability (HRV) analysis, and a preserved function is associated with a superior response to flunarizine preventive treatment.

Major finding: Most heart-rate variability (HRV) parameters, except the ratios of low-frequency (LF) band and LF/high-frequency band, were significantly lower in patients with migraine vs control individuals (P < .001). The response to flunarizine treatment was superior in patients with normal HRV, as exemplified by higher reductions in monthly headache days after 3 months in those with normal vs lower HRV (─9.7 days vs ─6.2 days; P = .026).

Study details: This cross-sectional, prospective study included 81 prophylaxis-naive patients with chronic migraine and 58 age- and gender-matched control individuals. Patients with migraine initiated flunarizine as a preventive treatment for 12 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, and others. SJ Wang declared being a principal investigator and receiving personal fees as an advisor or speaker from various sources.

Source: Chuang CH et al. Abnormal heart rate variability and its application in predicting treatment efficacy in patients with chronic migraine: An exploratory study. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Oct 18). doi: 10.1177/03331024231206781

Key clinical point: Patients with chronic migraine have autonomic dysfunction, the extent of which is evaluated using heart rate variability (HRV) analysis, and a preserved function is associated with a superior response to flunarizine preventive treatment.

Major finding: Most heart-rate variability (HRV) parameters, except the ratios of low-frequency (LF) band and LF/high-frequency band, were significantly lower in patients with migraine vs control individuals (P < .001). The response to flunarizine treatment was superior in patients with normal HRV, as exemplified by higher reductions in monthly headache days after 3 months in those with normal vs lower HRV (─9.7 days vs ─6.2 days; P = .026).

Study details: This cross-sectional, prospective study included 81 prophylaxis-naive patients with chronic migraine and 58 age- and gender-matched control individuals. Patients with migraine initiated flunarizine as a preventive treatment for 12 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, and others. SJ Wang declared being a principal investigator and receiving personal fees as an advisor or speaker from various sources.

Source: Chuang CH et al. Abnormal heart rate variability and its application in predicting treatment efficacy in patients with chronic migraine: An exploratory study. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Oct 18). doi: 10.1177/03331024231206781

Key clinical point: Patients with chronic migraine have autonomic dysfunction, the extent of which is evaluated using heart rate variability (HRV) analysis, and a preserved function is associated with a superior response to flunarizine preventive treatment.

Major finding: Most heart-rate variability (HRV) parameters, except the ratios of low-frequency (LF) band and LF/high-frequency band, were significantly lower in patients with migraine vs control individuals (P < .001). The response to flunarizine treatment was superior in patients with normal HRV, as exemplified by higher reductions in monthly headache days after 3 months in those with normal vs lower HRV (─9.7 days vs ─6.2 days; P = .026).

Study details: This cross-sectional, prospective study included 81 prophylaxis-naive patients with chronic migraine and 58 age- and gender-matched control individuals. Patients with migraine initiated flunarizine as a preventive treatment for 12 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, and others. SJ Wang declared being a principal investigator and receiving personal fees as an advisor or speaker from various sources.

Source: Chuang CH et al. Abnormal heart rate variability and its application in predicting treatment efficacy in patients with chronic migraine: An exploratory study. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Oct 18). doi: 10.1177/03331024231206781

Remote electrical neuromodulation: A pill-free, needle-free option for long-term migraine management

Key clinical point: This real-world study confirms the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) for long-term management of acute migraine, thus establishing REN as a valuable comprehensive treatment for this chronic disease.

Major finding: Overall, 74.1% and 26.0% of patients achieved consistent pain relief and pain freedom with REN, respectively, and 70.2% and 33.7% achieved functional disability relief and functional disability freedom, respectively. The incidence of device-related adverse events (dAE) was low, ie, 1.96%, which included 0.49% negligible, 1.22% moderate, and 0.24% mild AE. No severe AE were reported, and all patients continued treatment despite dAE.

Study details: This real-world evidence study included 409 patients with migraine treated for 12 consecutive months with REN, a self-administered device used at the onset of migraine headache or aura for acute treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd. M Weinstein and A Synowiec declared serving as consultants for Theranica. A Stark-Inbar and A Ironi declared being employees of and hold stock options in Theranica. A Mauskop had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source: Synowiec A et al. One-year consistent safety, utilization, and efficacy assessment of remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) for migraine treatment. Adv Ther. 2023 (Oct 19). doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02697-6

Key clinical point: This real-world study confirms the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) for long-term management of acute migraine, thus establishing REN as a valuable comprehensive treatment for this chronic disease.

Major finding: Overall, 74.1% and 26.0% of patients achieved consistent pain relief and pain freedom with REN, respectively, and 70.2% and 33.7% achieved functional disability relief and functional disability freedom, respectively. The incidence of device-related adverse events (dAE) was low, ie, 1.96%, which included 0.49% negligible, 1.22% moderate, and 0.24% mild AE. No severe AE were reported, and all patients continued treatment despite dAE.

Study details: This real-world evidence study included 409 patients with migraine treated for 12 consecutive months with REN, a self-administered device used at the onset of migraine headache or aura for acute treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd. M Weinstein and A Synowiec declared serving as consultants for Theranica. A Stark-Inbar and A Ironi declared being employees of and hold stock options in Theranica. A Mauskop had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source: Synowiec A et al. One-year consistent safety, utilization, and efficacy assessment of remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) for migraine treatment. Adv Ther. 2023 (Oct 19). doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02697-6

Key clinical point: This real-world study confirms the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) for long-term management of acute migraine, thus establishing REN as a valuable comprehensive treatment for this chronic disease.

Major finding: Overall, 74.1% and 26.0% of patients achieved consistent pain relief and pain freedom with REN, respectively, and 70.2% and 33.7% achieved functional disability relief and functional disability freedom, respectively. The incidence of device-related adverse events (dAE) was low, ie, 1.96%, which included 0.49% negligible, 1.22% moderate, and 0.24% mild AE. No severe AE were reported, and all patients continued treatment despite dAE.

Study details: This real-world evidence study included 409 patients with migraine treated for 12 consecutive months with REN, a self-administered device used at the onset of migraine headache or aura for acute treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd. M Weinstein and A Synowiec declared serving as consultants for Theranica. A Stark-Inbar and A Ironi declared being employees of and hold stock options in Theranica. A Mauskop had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source: Synowiec A et al. One-year consistent safety, utilization, and efficacy assessment of remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) for migraine treatment. Adv Ther. 2023 (Oct 19). doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02697-6

Ubrogepant and anti-CGRP mAb combo is effective for acute treatment of migraine

Key clinical point: The use of ubrogepant in combination with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody (mAb) leads to meaningful pain relief (MPR), return to normal function (RNF), treatment satisfaction, and acute treatment optimization in patients with migraine.

Major finding: Following the first treated attack, 61.6% and 80.4% of patients achieved MPR and 34.7% and 55.5% of patients achieved RNF at 2 hours and 4 hours post-dose, respectively, in the ubrogepant plus anti-CGRP mAb arm. Moreover, 72.7% of patients reported being satisfied with ubrogepant when used in combination with anti-CGRP mAb, and 79.7% of patients achieved acute treatment optimization at 30 days.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective, observational study that included 245 patients with migraine who were treated with ubrogepant combined with anti-CGRP mAb, onabotulinumtoxinA, or both, for migraine prevention.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie). RB Lipton declared receiving research support, honoraria, and royalties from, and serving as a consultant and advisory board member for various sources, including AbbVie or Allergan.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Real-world use of ubrogepant as acute treatment for migraine with an anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody: Results from COURAGE. Neurol Ther. 2023 (Nov 1). doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00556-8

Key clinical point: The use of ubrogepant in combination with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody (mAb) leads to meaningful pain relief (MPR), return to normal function (RNF), treatment satisfaction, and acute treatment optimization in patients with migraine.

Major finding: Following the first treated attack, 61.6% and 80.4% of patients achieved MPR and 34.7% and 55.5% of patients achieved RNF at 2 hours and 4 hours post-dose, respectively, in the ubrogepant plus anti-CGRP mAb arm. Moreover, 72.7% of patients reported being satisfied with ubrogepant when used in combination with anti-CGRP mAb, and 79.7% of patients achieved acute treatment optimization at 30 days.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective, observational study that included 245 patients with migraine who were treated with ubrogepant combined with anti-CGRP mAb, onabotulinumtoxinA, or both, for migraine prevention.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie). RB Lipton declared receiving research support, honoraria, and royalties from, and serving as a consultant and advisory board member for various sources, including AbbVie or Allergan.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Real-world use of ubrogepant as acute treatment for migraine with an anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody: Results from COURAGE. Neurol Ther. 2023 (Nov 1). doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00556-8

Key clinical point: The use of ubrogepant in combination with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody (mAb) leads to meaningful pain relief (MPR), return to normal function (RNF), treatment satisfaction, and acute treatment optimization in patients with migraine.

Major finding: Following the first treated attack, 61.6% and 80.4% of patients achieved MPR and 34.7% and 55.5% of patients achieved RNF at 2 hours and 4 hours post-dose, respectively, in the ubrogepant plus anti-CGRP mAb arm. Moreover, 72.7% of patients reported being satisfied with ubrogepant when used in combination with anti-CGRP mAb, and 79.7% of patients achieved acute treatment optimization at 30 days.

Study details: Findings are from a prospective, observational study that included 245 patients with migraine who were treated with ubrogepant combined with anti-CGRP mAb, onabotulinumtoxinA, or both, for migraine prevention.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie). RB Lipton declared receiving research support, honoraria, and royalties from, and serving as a consultant and advisory board member for various sources, including AbbVie or Allergan.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Real-world use of ubrogepant as acute treatment for migraine with an anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody: Results from COURAGE. Neurol Ther. 2023 (Nov 1). doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00556-8

Effect of CGRP mAb rollout on prescription patterns of other migraine preventive therapies

Key clinical point: The introduction of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) has led to a reduction in the prescription of other oral preventive therapies for chronic migraine, likely due to the similar efficacy and better safety profile of CGRP mAb.

Major finding: Overall, the percentage of commonly prescribed preventive medications reduced significantly from 46.3% before the introduction of CGRP mAb to 43.1% post introduction (P = .001), including a large decrease in the prescription of verapamil, tricyclic antidepressants, topiramate, onabotulinumtoxinA, valproate, duloxetine, memantine, and propranolol (all P < .05).

Study details: This retrospective cohort study compared the percentage of patients with chronic migraine who were prescribed oral preventive medications or onabotulinumtoxinA during the CGRP mAb pre-approval period (2015-2017; n = 3144) and post-approval period (2019-2021; n = 4629).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Moskatel LS et al. The introduction of the CGRP monoclonal antibodies and their effect on the prescription patterns of chronic migraine preventive medications in a tertiary headache center: A retrospective, observational analysis. Headache. 2023 (Oct 26). doi: 10.1111/head.14642

Key clinical point: The introduction of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) has led to a reduction in the prescription of other oral preventive therapies for chronic migraine, likely due to the similar efficacy and better safety profile of CGRP mAb.

Major finding: Overall, the percentage of commonly prescribed preventive medications reduced significantly from 46.3% before the introduction of CGRP mAb to 43.1% post introduction (P = .001), including a large decrease in the prescription of verapamil, tricyclic antidepressants, topiramate, onabotulinumtoxinA, valproate, duloxetine, memantine, and propranolol (all P < .05).

Study details: This retrospective cohort study compared the percentage of patients with chronic migraine who were prescribed oral preventive medications or onabotulinumtoxinA during the CGRP mAb pre-approval period (2015-2017; n = 3144) and post-approval period (2019-2021; n = 4629).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Moskatel LS et al. The introduction of the CGRP monoclonal antibodies and their effect on the prescription patterns of chronic migraine preventive medications in a tertiary headache center: A retrospective, observational analysis. Headache. 2023 (Oct 26). doi: 10.1111/head.14642

Key clinical point: The introduction of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) has led to a reduction in the prescription of other oral preventive therapies for chronic migraine, likely due to the similar efficacy and better safety profile of CGRP mAb.

Major finding: Overall, the percentage of commonly prescribed preventive medications reduced significantly from 46.3% before the introduction of CGRP mAb to 43.1% post introduction (P = .001), including a large decrease in the prescription of verapamil, tricyclic antidepressants, topiramate, onabotulinumtoxinA, valproate, duloxetine, memantine, and propranolol (all P < .05).

Study details: This retrospective cohort study compared the percentage of patients with chronic migraine who were prescribed oral preventive medications or onabotulinumtoxinA during the CGRP mAb pre-approval period (2015-2017; n = 3144) and post-approval period (2019-2021; n = 4629).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Moskatel LS et al. The introduction of the CGRP monoclonal antibodies and their effect on the prescription patterns of chronic migraine preventive medications in a tertiary headache center: A retrospective, observational analysis. Headache. 2023 (Oct 26). doi: 10.1111/head.14642

BMI and migraine risk in adolescents: What’s the link?

Key clinical point: Adolescents who are underweight or obese are at an increased risk for migraine, with the risk being more pronounced in case of women.

Major finding: Adolescent women who were underweight or obese had 12% (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.12; 95% CI 1.05-1.19) and 38% (aOR 1.38; 95% CI 1.31-1.46) higher risks for migraine, respectively, than women with low-normal body mass index (BMI) values. Men who were underweight or obese had 11% (aOR 1.11; 95% CI 1.06-1.16) and 24% (aOR 1,24; 95% CI 1.19-1.30) higher risks for migraine, respectively, than men with low-normal BMI values.

Study details: The data come from a retrospective cross-sectional study including 2,094,862 adolescents (age 16-19 years), of whom 57,385 had migraine.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zloof Y et al. Body mass index and migraine in adolescence: A nationwide study. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Oct 26). doi: 10.1177/03331024231209309

Key clinical point: Adolescents who are underweight or obese are at an increased risk for migraine, with the risk being more pronounced in case of women.

Major finding: Adolescent women who were underweight or obese had 12% (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.12; 95% CI 1.05-1.19) and 38% (aOR 1.38; 95% CI 1.31-1.46) higher risks for migraine, respectively, than women with low-normal body mass index (BMI) values. Men who were underweight or obese had 11% (aOR 1.11; 95% CI 1.06-1.16) and 24% (aOR 1,24; 95% CI 1.19-1.30) higher risks for migraine, respectively, than men with low-normal BMI values.

Study details: The data come from a retrospective cross-sectional study including 2,094,862 adolescents (age 16-19 years), of whom 57,385 had migraine.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zloof Y et al. Body mass index and migraine in adolescence: A nationwide study. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Oct 26). doi: 10.1177/03331024231209309

Key clinical point: Adolescents who are underweight or obese are at an increased risk for migraine, with the risk being more pronounced in case of women.

Major finding: Adolescent women who were underweight or obese had 12% (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.12; 95% CI 1.05-1.19) and 38% (aOR 1.38; 95% CI 1.31-1.46) higher risks for migraine, respectively, than women with low-normal body mass index (BMI) values. Men who were underweight or obese had 11% (aOR 1.11; 95% CI 1.06-1.16) and 24% (aOR 1,24; 95% CI 1.19-1.30) higher risks for migraine, respectively, than men with low-normal BMI values.

Study details: The data come from a retrospective cross-sectional study including 2,094,862 adolescents (age 16-19 years), of whom 57,385 had migraine.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zloof Y et al. Body mass index and migraine in adolescence: A nationwide study. Cephalalgia. 2023 (Oct 26). doi: 10.1177/03331024231209309

Anti-CGRP antibodies improve depressive symptoms in migraine

Key clinical point: Treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antibodies for 3 months significantly improved depressive symptoms in patients with migraine, independent of the reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD).

Major finding: The proportion of patients with active depression reduced significantly after 3 months of treatment with erenumab and fremanezumab (both P < .001) but not in the group receiving no active treatment. Anti-CGRP medication vs no active medication led to additional reduction in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores (β 1.65; P = .01), independent of the reduction in MMD.

Study details: This prospective study included patients with migraine who received erenumab (n = 110), fremanezumab (n = 117), or no active medication (n = 68).

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding sources. Three authors declared receiving consultancy support, industry grant, or independent support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S, van der Arend BWH, et al. Depression and treatment with anti-calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) (ligand or receptor) antibodies for migraine. Eur J Neurol. 2023 (Oct 17). doi: 10.1111/ene.16106

Key clinical point: Treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antibodies for 3 months significantly improved depressive symptoms in patients with migraine, independent of the reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD).

Major finding: The proportion of patients with active depression reduced significantly after 3 months of treatment with erenumab and fremanezumab (both P < .001) but not in the group receiving no active treatment. Anti-CGRP medication vs no active medication led to additional reduction in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores (β 1.65; P = .01), independent of the reduction in MMD.

Study details: This prospective study included patients with migraine who received erenumab (n = 110), fremanezumab (n = 117), or no active medication (n = 68).

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding sources. Three authors declared receiving consultancy support, industry grant, or independent support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S, van der Arend BWH, et al. Depression and treatment with anti-calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) (ligand or receptor) antibodies for migraine. Eur J Neurol. 2023 (Oct 17). doi: 10.1111/ene.16106

Key clinical point: Treatment with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antibodies for 3 months significantly improved depressive symptoms in patients with migraine, independent of the reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD).

Major finding: The proportion of patients with active depression reduced significantly after 3 months of treatment with erenumab and fremanezumab (both P < .001) but not in the group receiving no active treatment. Anti-CGRP medication vs no active medication led to additional reduction in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores (β 1.65; P = .01), independent of the reduction in MMD.

Study details: This prospective study included patients with migraine who received erenumab (n = 110), fremanezumab (n = 117), or no active medication (n = 68).

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding sources. Three authors declared receiving consultancy support, industry grant, or independent support from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Vries Lentsch S, van der Arend BWH, et al. Depression and treatment with anti-calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) (ligand or receptor) antibodies for migraine. Eur J Neurol. 2023 (Oct 17). doi: 10.1111/ene.16106

Real-world evidence on efficacy of anti-CGRP mAbs in elderly patients with migraine

Key clinical point: This study provides class-III real-world evidence that anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are efficacious and safe in patients with migraine age > 65 years but may take more time to show effect in these patients vs those age < 55 years.

Major finding: A similar proportion of patients age > 65 years vs < 55 years achieved a 50% response rate at 20-24 weeks of initiating anti-CGRP mAb (P = .811). Patients age > 65 years vs < 55 years showed lesser reduction in mean monthly headache days at 10-12 weeks (P = .001) and higher reduction in mean monthly migraine days at 20-24 weeks (P = .04). Both groups had similar incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events.

Study details: This multicenter observational case-control study included 114 patients age > 65 years and 114 sex-matched patients age < 55 years with episodic or chronic migraine who received anti-CGRP mAb.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Several authors declared receiving research support, speaker honoraria, or lecture honoraria from or serving on the advisory boards of various sources.

Source: Gonzalez-Martinez A et al. Effectiveness, tolerability and response predictors of preventive anti-CGRP mAbs for migraine in patients over 65 years old: A multicenter real-world case-control study. Pain Med. 2023 (Oct 17). doi: 10.1093/pm/pnad141

Key clinical point: This study provides class-III real-world evidence that anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are efficacious and safe in patients with migraine age > 65 years but may take more time to show effect in these patients vs those age < 55 years.

Major finding: A similar proportion of patients age > 65 years vs < 55 years achieved a 50% response rate at 20-24 weeks of initiating anti-CGRP mAb (P = .811). Patients age > 65 years vs < 55 years showed lesser reduction in mean monthly headache days at 10-12 weeks (P = .001) and higher reduction in mean monthly migraine days at 20-24 weeks (P = .04). Both groups had similar incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events.

Study details: This multicenter observational case-control study included 114 patients age > 65 years and 114 sex-matched patients age < 55 years with episodic or chronic migraine who received anti-CGRP mAb.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Several authors declared receiving research support, speaker honoraria, or lecture honoraria from or serving on the advisory boards of various sources.

Source: Gonzalez-Martinez A et al. Effectiveness, tolerability and response predictors of preventive anti-CGRP mAbs for migraine in patients over 65 years old: A multicenter real-world case-control study. Pain Med. 2023 (Oct 17). doi: 10.1093/pm/pnad141

Key clinical point: This study provides class-III real-world evidence that anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (anti-CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are efficacious and safe in patients with migraine age > 65 years but may take more time to show effect in these patients vs those age < 55 years.

Major finding: A similar proportion of patients age > 65 years vs < 55 years achieved a 50% response rate at 20-24 weeks of initiating anti-CGRP mAb (P = .811). Patients age > 65 years vs < 55 years showed lesser reduction in mean monthly headache days at 10-12 weeks (P = .001) and higher reduction in mean monthly migraine days at 20-24 weeks (P = .04). Both groups had similar incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events.

Study details: This multicenter observational case-control study included 114 patients age > 65 years and 114 sex-matched patients age < 55 years with episodic or chronic migraine who received anti-CGRP mAb.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Several authors declared receiving research support, speaker honoraria, or lecture honoraria from or serving on the advisory boards of various sources.

Source: Gonzalez-Martinez A et al. Effectiveness, tolerability and response predictors of preventive anti-CGRP mAbs for migraine in patients over 65 years old: A multicenter real-world case-control study. Pain Med. 2023 (Oct 17). doi: 10.1093/pm/pnad141

Ketogenic diets improve symptoms and fatigue in chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine

Key clinical point: Three different ketogenic diets (KD)—very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD), low-glycemic-index diet (LGID), and 2:1 KD—improved migraine frequency, migraine intensity, and fatigue in patients with chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine.

Major finding: At 3 months, all three KD led to a significant reduction in the fatigue severity scale (FSS) scores, along with reductions in the frequency and intensity of migraine attacks, Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS) scores, and Headache Impact Test 6 (HIT-6) scores (all P < .001). The mean reduction in FSS had positive correlation with the mean reduction in MIDAS (r = 0.361; P = .002) and HIT-6 (r = 0.344; P = .001) scores.

Study details: This retrospective single-center pilot study included 76 patients with chronic or high-frequency episodic migraine who followed three different KD (VLCKD, LGID, or 2:1 KD) for ≥3 months.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Tereshko Y, Dal Bello S, et al. The effect of three different ketogenic diet protocols on migraine and fatigue in chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine: A pilot study. Nutrients. 2023;15(20):4334 (Oct 11). doi: 10.3390/nu15204334

Key clinical point: Three different ketogenic diets (KD)—very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD), low-glycemic-index diet (LGID), and 2:1 KD—improved migraine frequency, migraine intensity, and fatigue in patients with chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine.

Major finding: At 3 months, all three KD led to a significant reduction in the fatigue severity scale (FSS) scores, along with reductions in the frequency and intensity of migraine attacks, Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS) scores, and Headache Impact Test 6 (HIT-6) scores (all P < .001). The mean reduction in FSS had positive correlation with the mean reduction in MIDAS (r = 0.361; P = .002) and HIT-6 (r = 0.344; P = .001) scores.

Study details: This retrospective single-center pilot study included 76 patients with chronic or high-frequency episodic migraine who followed three different KD (VLCKD, LGID, or 2:1 KD) for ≥3 months.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Tereshko Y, Dal Bello S, et al. The effect of three different ketogenic diet protocols on migraine and fatigue in chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine: A pilot study. Nutrients. 2023;15(20):4334 (Oct 11). doi: 10.3390/nu15204334

Key clinical point: Three different ketogenic diets (KD)—very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD), low-glycemic-index diet (LGID), and 2:1 KD—improved migraine frequency, migraine intensity, and fatigue in patients with chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine.

Major finding: At 3 months, all three KD led to a significant reduction in the fatigue severity scale (FSS) scores, along with reductions in the frequency and intensity of migraine attacks, Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS) scores, and Headache Impact Test 6 (HIT-6) scores (all P < .001). The mean reduction in FSS had positive correlation with the mean reduction in MIDAS (r = 0.361; P = .002) and HIT-6 (r = 0.344; P = .001) scores.

Study details: This retrospective single-center pilot study included 76 patients with chronic or high-frequency episodic migraine who followed three different KD (VLCKD, LGID, or 2:1 KD) for ≥3 months.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Tereshko Y, Dal Bello S, et al. The effect of three different ketogenic diet protocols on migraine and fatigue in chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine: A pilot study. Nutrients. 2023;15(20):4334 (Oct 11). doi: 10.3390/nu15204334

Headache after drinking red wine? This could be why

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert Louis Stevenson famously said, “Wine is bottled poetry.” And I think it works quite well. I’ve had wines that are simple, elegant, and unpretentious like Emily Dickinson, and passionate and mysterious like Pablo Neruda. And I’ve had wines that are more analogous to the limerick you might read scrawled on a rest-stop bathroom wall. Those ones give me headaches.

– and apparently it’s not just the alcohol.

Headaches are common, and headaches after drinking alcohol are particularly common. An interesting epidemiologic phenomenon, not yet adequately explained, is why red wine is associated with more headache than other forms of alcohol. There have been many studies fingering many suspects, from sulfites to tannins to various phenolic compounds, but none have really provided a concrete explanation for what might be going on.

A new hypothesis came to the fore on Nov. 20 in the journal Scientific Reports:

To understand the idea, first a reminder of what happens when you drink alcohol, physiologically.

Alcohol is metabolized by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase in the gut and then in the liver. That turns it into acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite. In most of us, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) quickly metabolizes acetaldehyde to the inert acetate, which can be safely excreted.

I say “most of us” because some populations, particularly those with East Asian ancestry, have a mutation in the ALDH gene which can lead to accumulation of toxic acetaldehyde with alcohol consumption – leading to facial flushing, nausea, and headache.

We can also inhibit the enzyme medically. That’s what the drug disulfiram, also known as Antabuse, does. It doesn’t prevent you from wanting to drink; it makes the consequences of drinking incredibly aversive.

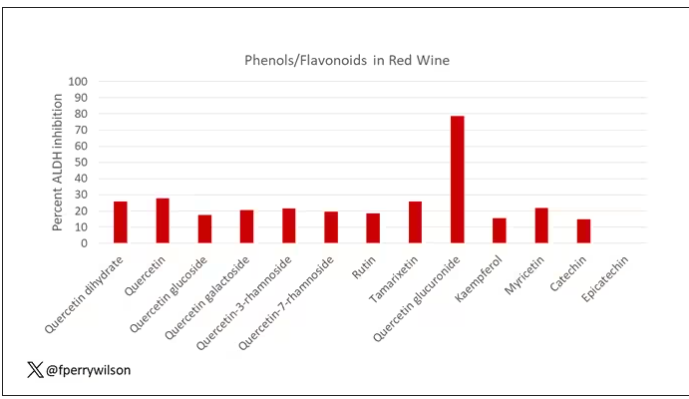

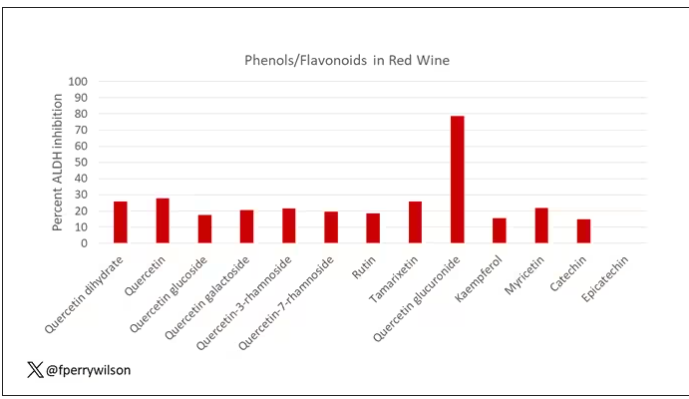

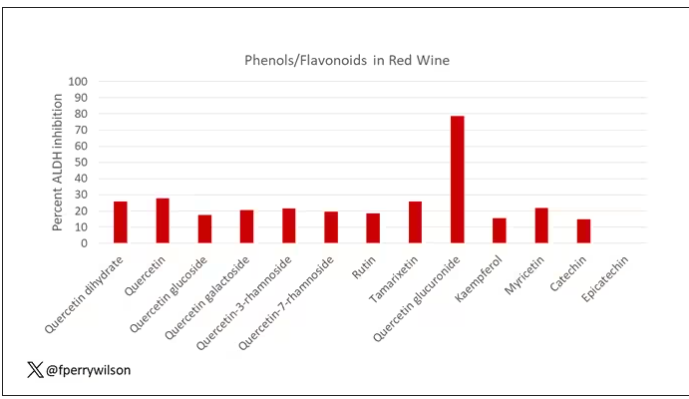

The researchers focused in on the aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme and conducted a screening study. Are there any compounds in red wine that naturally inhibit ALDH?

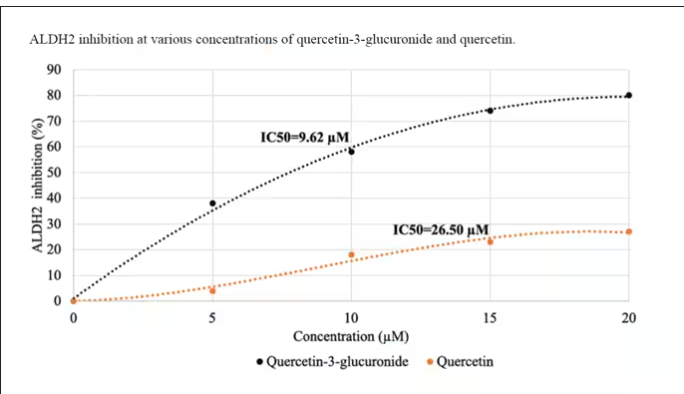

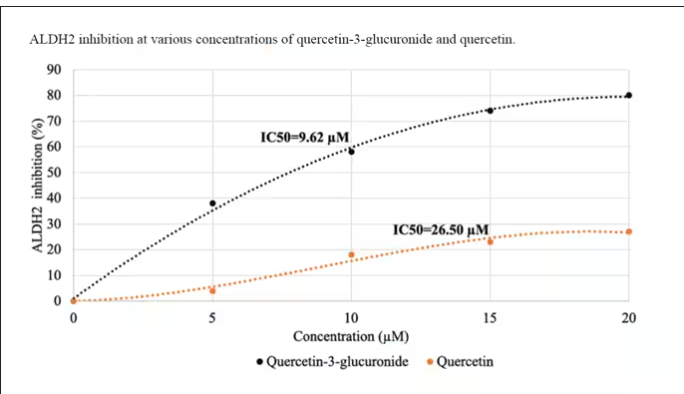

The results pointed squarely at quercetin, and particularly its metabolite quercetin glucuronide, which, at 20 micromolar concentrations, inhibited about 80% of ALDH activity.

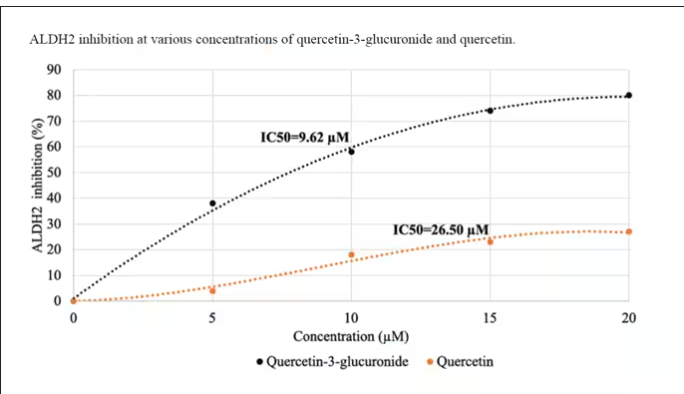

Quercetin is a flavonoid – a compound that gives color to a variety of vegetables and fruits, including grapes. In a test tube, it is an antioxidant, which is enough evidence to spawn a small quercetin-as-supplement industry, but there is no convincing evidence that it is medically useful. The authors then examined the concentration of quercetin glucuronide to achieve various inhibitions of ALDH, as you can see in this graph here.

By about 10 micromolar, we see a decent amount of inhibition. Disulfiram is about 10 times more potent than that, but then again, you don’t drink three glasses of disulfiram with Thanksgiving dinner.

This is where this study stops. But it obviously tells us very little about what might be happening in the human body. For that, we need to ask the question: Can we get our quercetin levels to 10 micromolar? Is that remotely achievable?

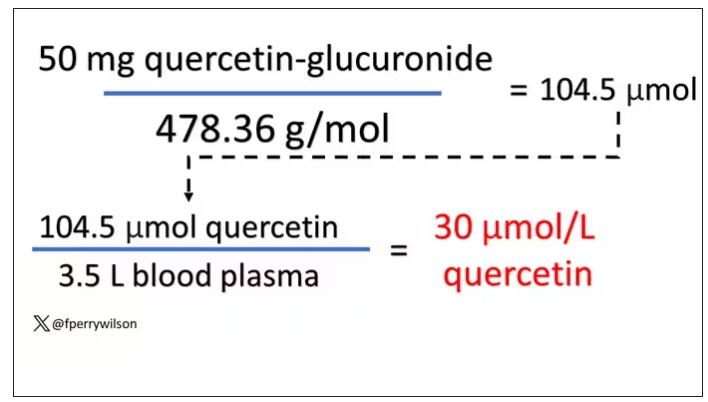

Let’s start with how much quercetin there is in red wine. Like all things wine, it varies, but this study examining Australian wines found mean concentrations of 11 mg/L. The highest value I saw was close to 50 mg/L.

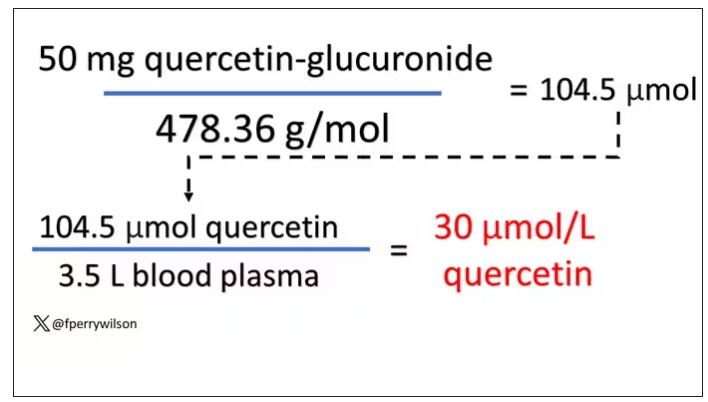

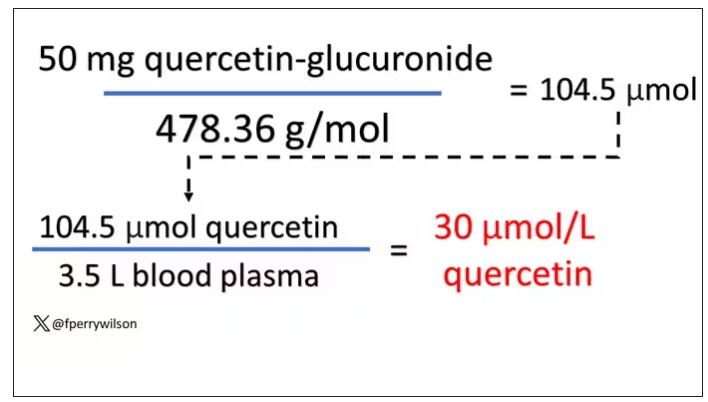

So let’s do some math. To make the numbers easy, let’s say you drank a liter of Australian wine, taking in 50 mg of quercetin glucuronide.

How much of that gets into your bloodstream? Some studies suggest a bioavailability of less than 1%, which basically means none and should probably put the quercetin hypothesis to bed. But there is some variation here too; it seems to depend on the form of quercetin you ingest.

Let’s say all 50 mg gets into your bloodstream. What blood concentration would that lead to? Well, I’ll keep the stoichiometry in the graphics and just say that if we assume that the volume of distribution of the compound is restricted to plasma alone, then you could achieve similar concentrations to what was done in petri dishes during this study.

Of course, if quercetin is really the culprit behind red wine headache, I have some questions: Why aren’t the Amazon reviews of quercetin supplements chock full of warnings not to take them with alcohol? And other foods have way higher quercetin concentration than wine, but you don’t hear people warning not to take your red onions with alcohol, or your capers, or lingonberries.

There’s some more work to be done here – most importantly, some human studies. Let’s give people wine with different amounts of quercetin and see what happens. Sign me up. Seriously.

As for Thanksgiving, it’s worth noting that cranberries have a lot of quercetin in them. So between the cranberry sauce, the Beaujolais, and your uncle ranting about the contrails again, the probability of headache is pretty darn high. Stay safe out there, and Happy Thanksgiving.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert Louis Stevenson famously said, “Wine is bottled poetry.” And I think it works quite well. I’ve had wines that are simple, elegant, and unpretentious like Emily Dickinson, and passionate and mysterious like Pablo Neruda. And I’ve had wines that are more analogous to the limerick you might read scrawled on a rest-stop bathroom wall. Those ones give me headaches.

– and apparently it’s not just the alcohol.

Headaches are common, and headaches after drinking alcohol are particularly common. An interesting epidemiologic phenomenon, not yet adequately explained, is why red wine is associated with more headache than other forms of alcohol. There have been many studies fingering many suspects, from sulfites to tannins to various phenolic compounds, but none have really provided a concrete explanation for what might be going on.

A new hypothesis came to the fore on Nov. 20 in the journal Scientific Reports:

To understand the idea, first a reminder of what happens when you drink alcohol, physiologically.

Alcohol is metabolized by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase in the gut and then in the liver. That turns it into acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite. In most of us, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) quickly metabolizes acetaldehyde to the inert acetate, which can be safely excreted.

I say “most of us” because some populations, particularly those with East Asian ancestry, have a mutation in the ALDH gene which can lead to accumulation of toxic acetaldehyde with alcohol consumption – leading to facial flushing, nausea, and headache.

We can also inhibit the enzyme medically. That’s what the drug disulfiram, also known as Antabuse, does. It doesn’t prevent you from wanting to drink; it makes the consequences of drinking incredibly aversive.

The researchers focused in on the aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme and conducted a screening study. Are there any compounds in red wine that naturally inhibit ALDH?

The results pointed squarely at quercetin, and particularly its metabolite quercetin glucuronide, which, at 20 micromolar concentrations, inhibited about 80% of ALDH activity.

Quercetin is a flavonoid – a compound that gives color to a variety of vegetables and fruits, including grapes. In a test tube, it is an antioxidant, which is enough evidence to spawn a small quercetin-as-supplement industry, but there is no convincing evidence that it is medically useful. The authors then examined the concentration of quercetin glucuronide to achieve various inhibitions of ALDH, as you can see in this graph here.

By about 10 micromolar, we see a decent amount of inhibition. Disulfiram is about 10 times more potent than that, but then again, you don’t drink three glasses of disulfiram with Thanksgiving dinner.

This is where this study stops. But it obviously tells us very little about what might be happening in the human body. For that, we need to ask the question: Can we get our quercetin levels to 10 micromolar? Is that remotely achievable?

Let’s start with how much quercetin there is in red wine. Like all things wine, it varies, but this study examining Australian wines found mean concentrations of 11 mg/L. The highest value I saw was close to 50 mg/L.

So let’s do some math. To make the numbers easy, let’s say you drank a liter of Australian wine, taking in 50 mg of quercetin glucuronide.

How much of that gets into your bloodstream? Some studies suggest a bioavailability of less than 1%, which basically means none and should probably put the quercetin hypothesis to bed. But there is some variation here too; it seems to depend on the form of quercetin you ingest.

Let’s say all 50 mg gets into your bloodstream. What blood concentration would that lead to? Well, I’ll keep the stoichiometry in the graphics and just say that if we assume that the volume of distribution of the compound is restricted to plasma alone, then you could achieve similar concentrations to what was done in petri dishes during this study.

Of course, if quercetin is really the culprit behind red wine headache, I have some questions: Why aren’t the Amazon reviews of quercetin supplements chock full of warnings not to take them with alcohol? And other foods have way higher quercetin concentration than wine, but you don’t hear people warning not to take your red onions with alcohol, or your capers, or lingonberries.

There’s some more work to be done here – most importantly, some human studies. Let’s give people wine with different amounts of quercetin and see what happens. Sign me up. Seriously.

As for Thanksgiving, it’s worth noting that cranberries have a lot of quercetin in them. So between the cranberry sauce, the Beaujolais, and your uncle ranting about the contrails again, the probability of headache is pretty darn high. Stay safe out there, and Happy Thanksgiving.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert Louis Stevenson famously said, “Wine is bottled poetry.” And I think it works quite well. I’ve had wines that are simple, elegant, and unpretentious like Emily Dickinson, and passionate and mysterious like Pablo Neruda. And I’ve had wines that are more analogous to the limerick you might read scrawled on a rest-stop bathroom wall. Those ones give me headaches.

– and apparently it’s not just the alcohol.

Headaches are common, and headaches after drinking alcohol are particularly common. An interesting epidemiologic phenomenon, not yet adequately explained, is why red wine is associated with more headache than other forms of alcohol. There have been many studies fingering many suspects, from sulfites to tannins to various phenolic compounds, but none have really provided a concrete explanation for what might be going on.

A new hypothesis came to the fore on Nov. 20 in the journal Scientific Reports:

To understand the idea, first a reminder of what happens when you drink alcohol, physiologically.

Alcohol is metabolized by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase in the gut and then in the liver. That turns it into acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite. In most of us, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) quickly metabolizes acetaldehyde to the inert acetate, which can be safely excreted.

I say “most of us” because some populations, particularly those with East Asian ancestry, have a mutation in the ALDH gene which can lead to accumulation of toxic acetaldehyde with alcohol consumption – leading to facial flushing, nausea, and headache.

We can also inhibit the enzyme medically. That’s what the drug disulfiram, also known as Antabuse, does. It doesn’t prevent you from wanting to drink; it makes the consequences of drinking incredibly aversive.

The researchers focused in on the aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme and conducted a screening study. Are there any compounds in red wine that naturally inhibit ALDH?

The results pointed squarely at quercetin, and particularly its metabolite quercetin glucuronide, which, at 20 micromolar concentrations, inhibited about 80% of ALDH activity.

Quercetin is a flavonoid – a compound that gives color to a variety of vegetables and fruits, including grapes. In a test tube, it is an antioxidant, which is enough evidence to spawn a small quercetin-as-supplement industry, but there is no convincing evidence that it is medically useful. The authors then examined the concentration of quercetin glucuronide to achieve various inhibitions of ALDH, as you can see in this graph here.

By about 10 micromolar, we see a decent amount of inhibition. Disulfiram is about 10 times more potent than that, but then again, you don’t drink three glasses of disulfiram with Thanksgiving dinner.

This is where this study stops. But it obviously tells us very little about what might be happening in the human body. For that, we need to ask the question: Can we get our quercetin levels to 10 micromolar? Is that remotely achievable?

Let’s start with how much quercetin there is in red wine. Like all things wine, it varies, but this study examining Australian wines found mean concentrations of 11 mg/L. The highest value I saw was close to 50 mg/L.

So let’s do some math. To make the numbers easy, let’s say you drank a liter of Australian wine, taking in 50 mg of quercetin glucuronide.

How much of that gets into your bloodstream? Some studies suggest a bioavailability of less than 1%, which basically means none and should probably put the quercetin hypothesis to bed. But there is some variation here too; it seems to depend on the form of quercetin you ingest.

Let’s say all 50 mg gets into your bloodstream. What blood concentration would that lead to? Well, I’ll keep the stoichiometry in the graphics and just say that if we assume that the volume of distribution of the compound is restricted to plasma alone, then you could achieve similar concentrations to what was done in petri dishes during this study.

Of course, if quercetin is really the culprit behind red wine headache, I have some questions: Why aren’t the Amazon reviews of quercetin supplements chock full of warnings not to take them with alcohol? And other foods have way higher quercetin concentration than wine, but you don’t hear people warning not to take your red onions with alcohol, or your capers, or lingonberries.

There’s some more work to be done here – most importantly, some human studies. Let’s give people wine with different amounts of quercetin and see what happens. Sign me up. Seriously.

As for Thanksgiving, it’s worth noting that cranberries have a lot of quercetin in them. So between the cranberry sauce, the Beaujolais, and your uncle ranting about the contrails again, the probability of headache is pretty darn high. Stay safe out there, and Happy Thanksgiving.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescents with migraine need smooth handoff to adult care

, according to a headache specialist who treats adults and children and spoke at the 2023 Scottsdale Headache Symposium.

“I would start at about the age of 15 or 16,” said Hope L. O’Brien, MD, Headache Center of Hope, University of Cincinnati.

Describing the steps that she thinks should be included in an effective transition, Dr. O’Brien maintained, “you will have a greater chance of successful transition and lessen the likelihood of the chronicity and the poor outcomes that we see in adults.”

Dr. O’Brien, who developed a headache clinic that serves individuals between the ages of 15 and 27, has substantial experience with headache patients in this age range. She acknowledged that there are no guideline recommendations for how best to guide the transition from pediatric to adult care, but she has developed some strategies at her own institution, including a tool for determining when the transition should be considered.

“Transition readiness is something that you need to think about,” she said. “You don’t just do it [automatically] at the age of 18.”

TRAQ questionnaire is helpful

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) is one tool that can be helpful, according to Dr. O’Brien, This tool, which can be used to evaluate whether young patients feel prepared to describe their own health status and needs and advocate on their own behalf, is not specific to headache, but the principle is particularly important in headache because of the importance of the patient’s history. Dr. O’Brien said that a fellow in her program, Allyson Bazarsky, MD, who is now affiliated with the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, validated TRAQ for headache about 6 years ago.

“TRAQ is available online. It’s free. You can download it as a PDF,” Dr. O’Brien said. In fact, several age-specific versions can now be found readily on a web search for TRAQ questionnaire.

Ultimately, TRAQ helps the clinician to gauge what patients know about their disease, the medications they are taking, and the relevance of any comorbidities, such as mood disorders. It also provides insight about the ability to understand their health issues and to communicate well with caregivers.

Dr. O’Brien sees this as a process over time, rather than something to be implemented a few months before the transition.

“It is important to start making the shift during childhood and talking directly to the child,” Dr. O’Brien said. If education about the disease and its triggers are started relatively early in adolescence, the transition will not only be easier, but patients might have a chance to understand and control their disease at an earlier age.

With this kind of approach, most children are at least in the preparation stage by age 18 years. However, the age at which patients are suitable for transition varies substantially. Many patients 18 years of age or older are in the “action phase,” meaning it is time to take steps to transition.

Again, based on the interrelationship between headache and comorbidities, particularly mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, the goal should not be limited to headache. Young adults should be educated about taking responsibility for their overall health.

In addition to educating the patient, Dr. O’Brien recommended preparing a transfer packet, such as the one described in an article published in Headache. Geared for communicating with the clinician who will take over care, the contents should include a detailed medical history along with the current treatment plan and list of medications that have been effective and those that have failed, according to Dr. O’Brien.

“An emergency plan in the form of an emergency department letter in case the patient needs to seek emergent care at an outside facility” is also appropriate, Dr. O’Brien said.

The patient should be aware of what is in the transfer pack in order to participate in an informed discussion of health care with the adult neurologist.

Poor transition linked to poor outcomes

A substantial proportion of adolescents with migraine continue to experience episodes as an adult, particularly those with a delayed diagnosis of migraine, those with a first degree relative who has migraine, and those with poor health habits, but this is not inevitable. Dr. O’Brien noted that “unsuccessful transition of care” into adulthood is a factor associated with poorer outcomes, making it an appropriate target for optimizing outcomes.

“Have that discussion on transfer of care with an action plan and do that early, especially in those with chronic or persistent disability headaches,” Dr. O’Brien emphasized.

This is pertinent advice, according to Amy A. Gelfand, MD, director of the child and adolescent headache program at Benioff Children’s Hospitals, University of California, San Francisco. Senior author of a comprehensive review article on pediatric migraine in Neurologic Clinics, Dr. Gelfand said the practical value of young adults learning what medications they are taking, and why, can place them in a better position to monitor their disease and to understand when a clinical visit is appropriate.

“I agree that it is important to help young adults (i.e., 18- or 19-year-olds) to prepare for the transition from the pediatric health care environment to the adult one,” said Dr. Gelfand, who has written frequently on this and related topics, such as the impact of comorbidities on outcome.

Dr. O’Brien reports financial relationships with AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Guidepoint, Pfizer, and Vector Psychometric Group. Dr. Gelfand reports financial relationships with Allergan, Eli Lilly, EMKinetics, eNeura, Teva and Zosano.

, according to a headache specialist who treats adults and children and spoke at the 2023 Scottsdale Headache Symposium.

“I would start at about the age of 15 or 16,” said Hope L. O’Brien, MD, Headache Center of Hope, University of Cincinnati.

Describing the steps that she thinks should be included in an effective transition, Dr. O’Brien maintained, “you will have a greater chance of successful transition and lessen the likelihood of the chronicity and the poor outcomes that we see in adults.”

Dr. O’Brien, who developed a headache clinic that serves individuals between the ages of 15 and 27, has substantial experience with headache patients in this age range. She acknowledged that there are no guideline recommendations for how best to guide the transition from pediatric to adult care, but she has developed some strategies at her own institution, including a tool for determining when the transition should be considered.

“Transition readiness is something that you need to think about,” she said. “You don’t just do it [automatically] at the age of 18.”

TRAQ questionnaire is helpful

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) is one tool that can be helpful, according to Dr. O’Brien, This tool, which can be used to evaluate whether young patients feel prepared to describe their own health status and needs and advocate on their own behalf, is not specific to headache, but the principle is particularly important in headache because of the importance of the patient’s history. Dr. O’Brien said that a fellow in her program, Allyson Bazarsky, MD, who is now affiliated with the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, validated TRAQ for headache about 6 years ago.

“TRAQ is available online. It’s free. You can download it as a PDF,” Dr. O’Brien said. In fact, several age-specific versions can now be found readily on a web search for TRAQ questionnaire.

Ultimately, TRAQ helps the clinician to gauge what patients know about their disease, the medications they are taking, and the relevance of any comorbidities, such as mood disorders. It also provides insight about the ability to understand their health issues and to communicate well with caregivers.

Dr. O’Brien sees this as a process over time, rather than something to be implemented a few months before the transition.

“It is important to start making the shift during childhood and talking directly to the child,” Dr. O’Brien said. If education about the disease and its triggers are started relatively early in adolescence, the transition will not only be easier, but patients might have a chance to understand and control their disease at an earlier age.

With this kind of approach, most children are at least in the preparation stage by age 18 years. However, the age at which patients are suitable for transition varies substantially. Many patients 18 years of age or older are in the “action phase,” meaning it is time to take steps to transition.

Again, based on the interrelationship between headache and comorbidities, particularly mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, the goal should not be limited to headache. Young adults should be educated about taking responsibility for their overall health.

In addition to educating the patient, Dr. O’Brien recommended preparing a transfer packet, such as the one described in an article published in Headache. Geared for communicating with the clinician who will take over care, the contents should include a detailed medical history along with the current treatment plan and list of medications that have been effective and those that have failed, according to Dr. O’Brien.

“An emergency plan in the form of an emergency department letter in case the patient needs to seek emergent care at an outside facility” is also appropriate, Dr. O’Brien said.

The patient should be aware of what is in the transfer pack in order to participate in an informed discussion of health care with the adult neurologist.

Poor transition linked to poor outcomes

A substantial proportion of adolescents with migraine continue to experience episodes as an adult, particularly those with a delayed diagnosis of migraine, those with a first degree relative who has migraine, and those with poor health habits, but this is not inevitable. Dr. O’Brien noted that “unsuccessful transition of care” into adulthood is a factor associated with poorer outcomes, making it an appropriate target for optimizing outcomes.

“Have that discussion on transfer of care with an action plan and do that early, especially in those with chronic or persistent disability headaches,” Dr. O’Brien emphasized.

This is pertinent advice, according to Amy A. Gelfand, MD, director of the child and adolescent headache program at Benioff Children’s Hospitals, University of California, San Francisco. Senior author of a comprehensive review article on pediatric migraine in Neurologic Clinics, Dr. Gelfand said the practical value of young adults learning what medications they are taking, and why, can place them in a better position to monitor their disease and to understand when a clinical visit is appropriate.

“I agree that it is important to help young adults (i.e., 18- or 19-year-olds) to prepare for the transition from the pediatric health care environment to the adult one,” said Dr. Gelfand, who has written frequently on this and related topics, such as the impact of comorbidities on outcome.

Dr. O’Brien reports financial relationships with AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Guidepoint, Pfizer, and Vector Psychometric Group. Dr. Gelfand reports financial relationships with Allergan, Eli Lilly, EMKinetics, eNeura, Teva and Zosano.

, according to a headache specialist who treats adults and children and spoke at the 2023 Scottsdale Headache Symposium.

“I would start at about the age of 15 or 16,” said Hope L. O’Brien, MD, Headache Center of Hope, University of Cincinnati.

Describing the steps that she thinks should be included in an effective transition, Dr. O’Brien maintained, “you will have a greater chance of successful transition and lessen the likelihood of the chronicity and the poor outcomes that we see in adults.”

Dr. O’Brien, who developed a headache clinic that serves individuals between the ages of 15 and 27, has substantial experience with headache patients in this age range. She acknowledged that there are no guideline recommendations for how best to guide the transition from pediatric to adult care, but she has developed some strategies at her own institution, including a tool for determining when the transition should be considered.

“Transition readiness is something that you need to think about,” she said. “You don’t just do it [automatically] at the age of 18.”

TRAQ questionnaire is helpful

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) is one tool that can be helpful, according to Dr. O’Brien, This tool, which can be used to evaluate whether young patients feel prepared to describe their own health status and needs and advocate on their own behalf, is not specific to headache, but the principle is particularly important in headache because of the importance of the patient’s history. Dr. O’Brien said that a fellow in her program, Allyson Bazarsky, MD, who is now affiliated with the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, validated TRAQ for headache about 6 years ago.

“TRAQ is available online. It’s free. You can download it as a PDF,” Dr. O’Brien said. In fact, several age-specific versions can now be found readily on a web search for TRAQ questionnaire.

Ultimately, TRAQ helps the clinician to gauge what patients know about their disease, the medications they are taking, and the relevance of any comorbidities, such as mood disorders. It also provides insight about the ability to understand their health issues and to communicate well with caregivers.

Dr. O’Brien sees this as a process over time, rather than something to be implemented a few months before the transition.

“It is important to start making the shift during childhood and talking directly to the child,” Dr. O’Brien said. If education about the disease and its triggers are started relatively early in adolescence, the transition will not only be easier, but patients might have a chance to understand and control their disease at an earlier age.

With this kind of approach, most children are at least in the preparation stage by age 18 years. However, the age at which patients are suitable for transition varies substantially. Many patients 18 years of age or older are in the “action phase,” meaning it is time to take steps to transition.

Again, based on the interrelationship between headache and comorbidities, particularly mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, the goal should not be limited to headache. Young adults should be educated about taking responsibility for their overall health.

In addition to educating the patient, Dr. O’Brien recommended preparing a transfer packet, such as the one described in an article published in Headache. Geared for communicating with the clinician who will take over care, the contents should include a detailed medical history along with the current treatment plan and list of medications that have been effective and those that have failed, according to Dr. O’Brien.

“An emergency plan in the form of an emergency department letter in case the patient needs to seek emergent care at an outside facility” is also appropriate, Dr. O’Brien said.

The patient should be aware of what is in the transfer pack in order to participate in an informed discussion of health care with the adult neurologist.

Poor transition linked to poor outcomes

A substantial proportion of adolescents with migraine continue to experience episodes as an adult, particularly those with a delayed diagnosis of migraine, those with a first degree relative who has migraine, and those with poor health habits, but this is not inevitable. Dr. O’Brien noted that “unsuccessful transition of care” into adulthood is a factor associated with poorer outcomes, making it an appropriate target for optimizing outcomes.

“Have that discussion on transfer of care with an action plan and do that early, especially in those with chronic or persistent disability headaches,” Dr. O’Brien emphasized.

This is pertinent advice, according to Amy A. Gelfand, MD, director of the child and adolescent headache program at Benioff Children’s Hospitals, University of California, San Francisco. Senior author of a comprehensive review article on pediatric migraine in Neurologic Clinics, Dr. Gelfand said the practical value of young adults learning what medications they are taking, and why, can place them in a better position to monitor their disease and to understand when a clinical visit is appropriate.

“I agree that it is important to help young adults (i.e., 18- or 19-year-olds) to prepare for the transition from the pediatric health care environment to the adult one,” said Dr. Gelfand, who has written frequently on this and related topics, such as the impact of comorbidities on outcome.

Dr. O’Brien reports financial relationships with AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Guidepoint, Pfizer, and Vector Psychometric Group. Dr. Gelfand reports financial relationships with Allergan, Eli Lilly, EMKinetics, eNeura, Teva and Zosano.

FROM THE 2023 SCOTTSDALE HEADACHE SYMPOSIUM