User login

Barriers to System Quality Improvement in Health Care

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

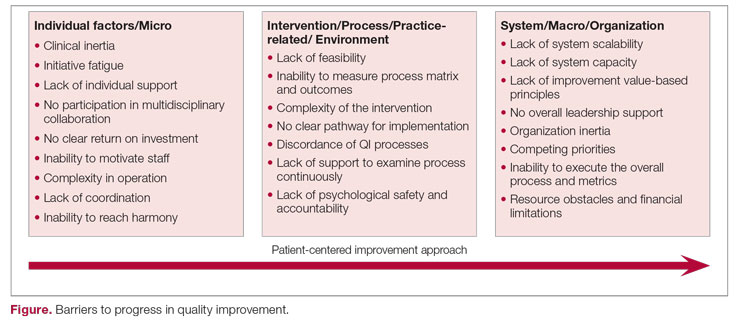

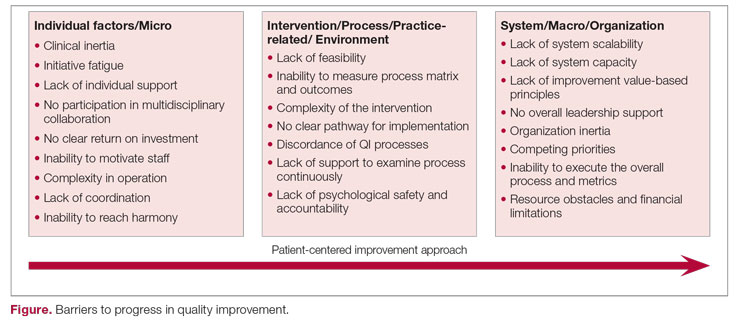

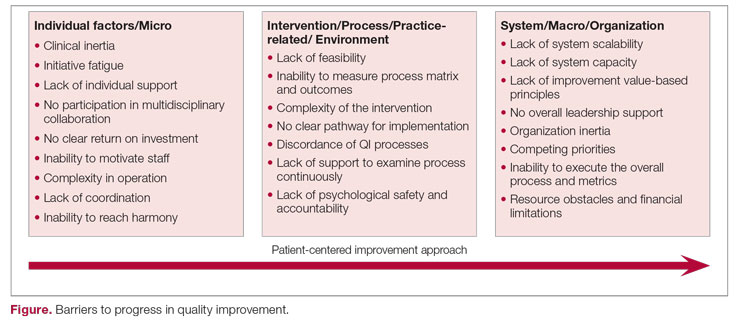

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21

9. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

10. Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth‐Rublee B, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):30-8. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

11. Huang HC, Lai MC, Lin LH, Chen CT. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J Organizational Change Manage. 2013;26(6):977-1002. doi:10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Process improvement in any industry sector aims to increase the efficiency of resource utilization and delivery methods (cost) and the quality of the product (outcomes), with the goal of ultimately achieving continuous development.1 In the health care industry, variation in processes and outcomes along with inefficiency in resource use that result in changes in value (the product of outcomes/costs) are the general targets of quality improvement (QI) efforts employing various implementation methodologies.2 When the ultimate aim is to serve the patient (customer), best clinical practice includes both maintaining high quality (individual care delivery) and controlling costs (efficient care system delivery), leading to optimal delivery (value-based care). High-quality individual care and efficient care delivery are not competing concepts, but when working to improve both health care outcomes and cost, traditional and nontraditional barriers to system QI often arise.3

The possible scenarios after a QI intervention include backsliding (regression to the mean over time), steady-state (minimal fixed improvement that could sustain), and continuous improvement (tangible enhancement after completing the intervention with legacy effect).4 The scalability of results can be considered during the process measurement and the intervention design phases of all QI projects; however, the complex nature of barriers in the health care environment during each level of implementation should be accounted for to prevent failure in the scalability phase.5

The barriers to optimal QI outcomes leading to continuous improvement are multifactorial and are related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.6 These factors include 3 fundamental levels: (1) individual level inertia/beliefs, prior personal knowledge, and team-related factors7,8; (2) intervention-related and process-specific barriers and clinical practice obstacles; and (3) organizational level challenges and macro-level and population-level barriers (Figure). The obstacles faced during the implementation phase will likely include 2 of these levels simultaneously, which could add complexity and hinder or prevent the implementation of a tangible successful QI process and eventually lead to backsliding or minimal fixed improvement rather than continuous improvement. Furthermore, a patient-centered approach to QI would contribute to further complexity in design and execution, given the importance of reaching sustainable, meaningful improvement by adding elements of patient’s preferences, caregiver engagement, and the shared decision-making processes.9

Overcoming these multidomain barriers and reaching resilience and sustainability requires thoughtful planning and execution through a multifaceted approach.10 A meaningful start could include addressing the clinical inertia for the individual and the team by promoting open innovation and allowing outside institutional collaborations and ideas through networks.11 On the individual level, encouraging participation and motivating health care workers in QI to reach a multidisciplinary operation approach will lead to harmony in collaboration. Concurrently, the organization should support the QI capability and scalability by removing competing priorities and establishing effective leadership that ensures resource allocation, communicates clear value-based principles, and engenders a psychological safety environment.

A continuous improvement state is the optimal QI target, a target that can be attained by removing obstacles and paving a clear pathway to implementation. Focusing on the 3 levels of barriers will position the organization for meaningful and successful QI phases to achieve continuous improvement.

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21

9. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

10. Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth‐Rublee B, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):30-8. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

11. Huang HC, Lai MC, Lin LH, Chen CT. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J Organizational Change Manage. 2013;26(6):977-1002. doi:10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

1. Adesola S, Baines T. Developing and evaluating a methodology for business process improvement. Business Process Manage J. 2005;11(1):37-46. doi:10.1108/14637150510578719

2. Gershon M. Choosing which process improvement methodology to implement. J Appl Business & Economics. 2010;10(5):61-69.

3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business Press; 2006.

4. Holweg M, Davies J, De Meyer A, Lawson B, Schmenner RW. Process Theory: The Principles of Operations Management. Oxford University Press; 2018.

5. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00107

6. Solomons NM, Spross JA. Evidence‐based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. J Nurs Manage. 2011;19(1):109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01144.x

7. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

8. Stevenson K, Baker R, Farooqi A, Sorrie R, Khunti K. Features of primary health care teams associated with successful quality improvement of diabetes care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):21-26. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.1.21

9. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. January 1, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

10. Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth‐Rublee B, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):30-8. doi:10.1002/wps.20482

11. Huang HC, Lai MC, Lin LH, Chen CT. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J Organizational Change Manage. 2013;26(6):977-1002. doi:10.1108/JOCM-04-2012-0047

When the public misplaces their trust

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

Not long ago, the grandmother of my son’s friend died of COVID-19 infection. She was elderly and unvaccinated. Her grandson had no regrets over her unvaccinated status. “Why would she inject poison into her body?” he said, and then expressed a strong opinion that she had died because the hospital physicians refused to give her ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. My son, wisely, did not push the issue.

Soon thereafter, my personal family physician emailed a newsletter to his patients (me included) with 3 important messages: (1) COVID vaccines were available in the office; (2) He was not going to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, no matter how adamantly it was requested; and (3) He warned against threatening him or his staff with lawsuits or violence over refusal to prescribe any unproven medication.

How, as a country, have we come to this? A sizeable portion of the public trusts the advice of quacks, hacks, and political opportunists over that of the nation’s most expert scientists and physicians. The National Institutes of Health maintains a website with up-to-date recommendations on the use of treatments for COVID-19. They assess the existing evidence and make recommendations for or against a wide array of interventions. (They recommend against the use of both ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention publishes extensively about the current knowledge on the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Neither agency is part of a “deep state” or conspiracy. They are comprised of some of the nation’s leading scientists, including physicians, trying to protect the public from disease and foster good health.

Sadly, some physicians have been a source of inaccurate vaccine information; some even prescribe ineffective treatments despite the evidence. These physicians are either letting their politics override their good sense or are improperly assessing the scientific literature, or both. Medical licensing agencies, and specialty certification boards, need to find ways to prevent this—ways that can survive judicial scrutiny and allow for legitimate scientific debate.

I have been tempted to just accept the current situation as the inevitable outcome of social media–fueled tribalism. But when we know that the COVID death rate among the unvaccinated is 9 times that of people who have received a booster dose,1 I can’t sit idly and watch the Internet pundits prevail. Instead, I continue to advise and teach my students to have confidence in trustworthy authorities and websites. Mistakes will be made; corrections will be issued. However, this is not evidence of malintent or incompetence, but rather, the scientific process in action.

I tell my students that one of the biggest challenges facing them and society is to figure out how to stop, or at least minimize the effects of, incorrect information, misleading statements, and outright lies in a society that values free speech. Physicians—young and old alike—must remain committed to communicating factual information to a not-always-receptive audience. And I wish my young colleagues luck; I hope that their passion for family medicine and their insights into social media may be just the combination that’s needed to redirect the public’s trust back to where it belongs during a health care crisis.

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

1. Fleming-Dutra KE. COVID-19 Epidemiology and Vaccination Rates in the United States. Presented to the Authorization Committee on Immunization Practices, July 19, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-07-19/02-COVID-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

How docs in firearm-friendly states talk gun safety

Samuel Mathis, MD, tries to cover a lot of ground during a wellness exam for his patients. Nutrition, immunizations, dental hygiene, and staying safe at school are a few of the topics on his list. And the Texas pediatrician asks one more question of children and their parents: “Are there any firearms in the house?”

If the answer is “yes,” Dr. Mathis discusses safety courses and other ideas with the families. “Rather than ask a bunch of questions, often I will say it’s recommended to keep them locked up and don’t forget toddlers can climb heights that you never would have envisioned,” said Dr. Mathis, an assistant professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

Dr. Mathis said some of his physician colleagues are wary of bringing up the topic of guns in a state that leads the nation with more than 1 million registered firearms. “My discussion is more on firearm responsibility and just making sure they are taking extra steps to keep themselves and everyone around them safe. That works much better in these discussions.”

Gun safety: Public health concern, not politics

The statistics tell why:

- Unintentional shooting deaths by children rose by nearly one third in a 3-month period in 2020, compared with the same period in 2019.

- Of every 10 gun deaths in the United States, 6 are by suicide.

- As of July 28, 372 mass shootings have occured.

- Firearms now represent the leading cause of death among the nation’s youth.

In 2018, the editors of Annals of Internal Medicine urged physicians in the United States to sign a pledge to talk with their patients about guns in the home. To date, at least 3,664 have done so.

In 2019, the American Academy of Family Medicine, with other leading physician and public health organizations, issued a “call to action,” recommending ways to reduce firearm-related injury and death in the United States. Physicians can and should address the issue, it said, by counseling patients about firearm safety.

“This is just another part of healthcare,” said Sarah C. Nosal, MD, a member of the board of directors of the AAFP, who practices at the Urban Horizons Family Health Center, New York.

Dr. Nosal said she asks about firearms during every well-child visit. She also focuses on patients with a history of depression or suicide attempts and those who have experienced domestic violence.

Are physicians counseling patients about gun safety?

A 2018 survey of physicians found that 73% of the 71 who responded agreed to discuss gun safety with at-risk patients. But just 5% said they always talk to those at-risk patients, according to Melanie G. Hagen, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Florida, Gainesville, who led the study. While the overwhelming majority agreed that gun safety is a public health issue, only 55% said they felt comfortable initiating conversations about firearms with their patients.

Have things changed since then? “Probably not,” Dr. Hagen said in an interview. She cited some reasons, at least in her state.

One obstacle is that many people, including physicians, believe that Florida’s physician gag law, which prohibited physicians from asking about a patient’s firearm ownership, was still in effect. The law, passed in 2011, was overturned in 2017. In her survey, 76% said they were aware it had been overturned. But that awareness appears not to be universal, she said.

In a 2020 report about physician involvement in promoting gun safety, researchers noted four main challenges: lingering fears about the overturned law and potential liability from violating it, feeling unprepared, worry that patients don’t want to discuss the topic, and lack of time to talk about it during a rushed office visit.

But recent research suggests that patients are often open to talking about gun safety, and another study found that if physicians are given educational materials on firearm safety, more will counsel patients about gun safety.

Are patients and parents receptive?

Parents welcome discussion from health care providers about gun safety, according to a study from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers asked roughly 100 parents to watch a short video about a firearm safety program designed to prevent accidents and suicides from guns. The program, still under study, involves a discussion between a parent and a pediatrician, with information given on secure storage of guns and the offering of a free cable lock.

The parents, about equally divided between gun owners and non–gun owners, said they were open to discussion about firearm safety, especially when the conversation involves their child’s pediatrician. Among the gun owners, only one in three said all their firearms were locked, unloaded, and stored properly. But after getting the safety information, 64% said they would change the way they stored their firearms.

A different program that offered pediatricians educational materials on firearm safety, as well as free firearm locks for distribution, increased the likelihood that the physicians would counsel patients on gun safety, other researchers reported.

Getting the conversation started

Some patients “bristle” when they’re asked about guns, Dr. Hagen said. Focusing on the “why” of the question can soften their response. One of her patients, a man in his 80s, had worked as a prison guard. After he was diagnosed with clinical depression, she asked him if he ever thought about ending his life. He said yes.

“And in Florida, I know a lot of people have guns,” she said. The state ranks second in the nation, with more than a half million registered weapons.

When Dr. Hagen asked him if he had firearms at home, he balked. Why did she need to know? “People do get defensive,” she said. “Luckily, I had a good relationship with this man, and he was willing to listen to me. If it’s someone I have a good relationship with, and I have this initial bristling, if I say: ‘I’m worried about you, I’m worried about your safety,’ that changes the entire conversation.”

She talked through the best plan for this patient, and he agreed to give his weapons to his son to keep.

Likewise, she talks with family members of dementia patients, urging them to be sure the weapons are stored and locked to prevent tragic accidents.

Dr. Nosal said reading the room is key. “Often, we are having the conversation with a parent with a child present,” she said. “Perhaps that is not the conversation the parent or guardian wanted to have with the child present.” In such a situation, she suggests asking the parent if they would talk about it solo.

“It can be a challenge to know the appropriate way to start the conversation,” Dr. Mathis said. The topic is not taught in medical school, although many experts think it should be. Dr. Hagen recently delivered a lecture to medical students about how to broach the topic with patients. She said she hopes it will become a regular event.

“It really comes down to being willing to be open and just ask that first question in a nonjudgmental way,” Dr. Mathis said. It helps, too, he said, for physicians to remember what he always tries to keep in mind: “My job isn’t politics, my job is health.”

Among the points Dr. Hagen makes in her lecture about talking to patients about guns are the following:

- Every day, more than 110 Americans are killed with guns.

- Gun violence accounts for just 1%-2% of those deaths, but mass shootings serve to shine a light on the issue of gun safety.

- 110,000 firearm injuries a year require medical or legal attention. Each year, more than 1,200 children in this country die from gun-related injuries.

- More than 33,000 people, on average, die in the United States each year from gun violence, including more than 21,000 from suicide.

- About 31% of all U.S. households have firearms; 22% of U.S. adults own one or more.

- Guns are 70% less likely to be stored locked and unloaded in homes where suicides or unintentional gun injuries occur.

- Action points: Identify risk, counsel patients at risk, act when someone is in imminent danger (such as unsafe practices or suicide threats).

- Focus on identifying adults who have a risk of inflicting violence on self or others.

- Focus on health and well-being with all; be conversational and educational.

- Clinicians should ask five crucial questions, all with an “L,” if firearms are in the home: Is it Loaded? Locked? Are Little children present? Is the owner feeling Low? Are they Learned [educated] in gun safety?

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Samuel Mathis, MD, tries to cover a lot of ground during a wellness exam for his patients. Nutrition, immunizations, dental hygiene, and staying safe at school are a few of the topics on his list. And the Texas pediatrician asks one more question of children and their parents: “Are there any firearms in the house?”

If the answer is “yes,” Dr. Mathis discusses safety courses and other ideas with the families. “Rather than ask a bunch of questions, often I will say it’s recommended to keep them locked up and don’t forget toddlers can climb heights that you never would have envisioned,” said Dr. Mathis, an assistant professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

Dr. Mathis said some of his physician colleagues are wary of bringing up the topic of guns in a state that leads the nation with more than 1 million registered firearms. “My discussion is more on firearm responsibility and just making sure they are taking extra steps to keep themselves and everyone around them safe. That works much better in these discussions.”

Gun safety: Public health concern, not politics

The statistics tell why:

- Unintentional shooting deaths by children rose by nearly one third in a 3-month period in 2020, compared with the same period in 2019.

- Of every 10 gun deaths in the United States, 6 are by suicide.

- As of July 28, 372 mass shootings have occured.

- Firearms now represent the leading cause of death among the nation’s youth.

In 2018, the editors of Annals of Internal Medicine urged physicians in the United States to sign a pledge to talk with their patients about guns in the home. To date, at least 3,664 have done so.

In 2019, the American Academy of Family Medicine, with other leading physician and public health organizations, issued a “call to action,” recommending ways to reduce firearm-related injury and death in the United States. Physicians can and should address the issue, it said, by counseling patients about firearm safety.

“This is just another part of healthcare,” said Sarah C. Nosal, MD, a member of the board of directors of the AAFP, who practices at the Urban Horizons Family Health Center, New York.

Dr. Nosal said she asks about firearms during every well-child visit. She also focuses on patients with a history of depression or suicide attempts and those who have experienced domestic violence.

Are physicians counseling patients about gun safety?

A 2018 survey of physicians found that 73% of the 71 who responded agreed to discuss gun safety with at-risk patients. But just 5% said they always talk to those at-risk patients, according to Melanie G. Hagen, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Florida, Gainesville, who led the study. While the overwhelming majority agreed that gun safety is a public health issue, only 55% said they felt comfortable initiating conversations about firearms with their patients.

Have things changed since then? “Probably not,” Dr. Hagen said in an interview. She cited some reasons, at least in her state.

One obstacle is that many people, including physicians, believe that Florida’s physician gag law, which prohibited physicians from asking about a patient’s firearm ownership, was still in effect. The law, passed in 2011, was overturned in 2017. In her survey, 76% said they were aware it had been overturned. But that awareness appears not to be universal, she said.

In a 2020 report about physician involvement in promoting gun safety, researchers noted four main challenges: lingering fears about the overturned law and potential liability from violating it, feeling unprepared, worry that patients don’t want to discuss the topic, and lack of time to talk about it during a rushed office visit.

But recent research suggests that patients are often open to talking about gun safety, and another study found that if physicians are given educational materials on firearm safety, more will counsel patients about gun safety.

Are patients and parents receptive?

Parents welcome discussion from health care providers about gun safety, according to a study from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers asked roughly 100 parents to watch a short video about a firearm safety program designed to prevent accidents and suicides from guns. The program, still under study, involves a discussion between a parent and a pediatrician, with information given on secure storage of guns and the offering of a free cable lock.

The parents, about equally divided between gun owners and non–gun owners, said they were open to discussion about firearm safety, especially when the conversation involves their child’s pediatrician. Among the gun owners, only one in three said all their firearms were locked, unloaded, and stored properly. But after getting the safety information, 64% said they would change the way they stored their firearms.

A different program that offered pediatricians educational materials on firearm safety, as well as free firearm locks for distribution, increased the likelihood that the physicians would counsel patients on gun safety, other researchers reported.

Getting the conversation started

Some patients “bristle” when they’re asked about guns, Dr. Hagen said. Focusing on the “why” of the question can soften their response. One of her patients, a man in his 80s, had worked as a prison guard. After he was diagnosed with clinical depression, she asked him if he ever thought about ending his life. He said yes.

“And in Florida, I know a lot of people have guns,” she said. The state ranks second in the nation, with more than a half million registered weapons.

When Dr. Hagen asked him if he had firearms at home, he balked. Why did she need to know? “People do get defensive,” she said. “Luckily, I had a good relationship with this man, and he was willing to listen to me. If it’s someone I have a good relationship with, and I have this initial bristling, if I say: ‘I’m worried about you, I’m worried about your safety,’ that changes the entire conversation.”

She talked through the best plan for this patient, and he agreed to give his weapons to his son to keep.

Likewise, she talks with family members of dementia patients, urging them to be sure the weapons are stored and locked to prevent tragic accidents.

Dr. Nosal said reading the room is key. “Often, we are having the conversation with a parent with a child present,” she said. “Perhaps that is not the conversation the parent or guardian wanted to have with the child present.” In such a situation, she suggests asking the parent if they would talk about it solo.

“It can be a challenge to know the appropriate way to start the conversation,” Dr. Mathis said. The topic is not taught in medical school, although many experts think it should be. Dr. Hagen recently delivered a lecture to medical students about how to broach the topic with patients. She said she hopes it will become a regular event.

“It really comes down to being willing to be open and just ask that first question in a nonjudgmental way,” Dr. Mathis said. It helps, too, he said, for physicians to remember what he always tries to keep in mind: “My job isn’t politics, my job is health.”

Among the points Dr. Hagen makes in her lecture about talking to patients about guns are the following:

- Every day, more than 110 Americans are killed with guns.

- Gun violence accounts for just 1%-2% of those deaths, but mass shootings serve to shine a light on the issue of gun safety.

- 110,000 firearm injuries a year require medical or legal attention. Each year, more than 1,200 children in this country die from gun-related injuries.

- More than 33,000 people, on average, die in the United States each year from gun violence, including more than 21,000 from suicide.

- About 31% of all U.S. households have firearms; 22% of U.S. adults own one or more.

- Guns are 70% less likely to be stored locked and unloaded in homes where suicides or unintentional gun injuries occur.

- Action points: Identify risk, counsel patients at risk, act when someone is in imminent danger (such as unsafe practices or suicide threats).

- Focus on identifying adults who have a risk of inflicting violence on self or others.

- Focus on health and well-being with all; be conversational and educational.

- Clinicians should ask five crucial questions, all with an “L,” if firearms are in the home: Is it Loaded? Locked? Are Little children present? Is the owner feeling Low? Are they Learned [educated] in gun safety?

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Samuel Mathis, MD, tries to cover a lot of ground during a wellness exam for his patients. Nutrition, immunizations, dental hygiene, and staying safe at school are a few of the topics on his list. And the Texas pediatrician asks one more question of children and their parents: “Are there any firearms in the house?”

If the answer is “yes,” Dr. Mathis discusses safety courses and other ideas with the families. “Rather than ask a bunch of questions, often I will say it’s recommended to keep them locked up and don’t forget toddlers can climb heights that you never would have envisioned,” said Dr. Mathis, an assistant professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

Dr. Mathis said some of his physician colleagues are wary of bringing up the topic of guns in a state that leads the nation with more than 1 million registered firearms. “My discussion is more on firearm responsibility and just making sure they are taking extra steps to keep themselves and everyone around them safe. That works much better in these discussions.”

Gun safety: Public health concern, not politics

The statistics tell why:

- Unintentional shooting deaths by children rose by nearly one third in a 3-month period in 2020, compared with the same period in 2019.

- Of every 10 gun deaths in the United States, 6 are by suicide.

- As of July 28, 372 mass shootings have occured.

- Firearms now represent the leading cause of death among the nation’s youth.

In 2018, the editors of Annals of Internal Medicine urged physicians in the United States to sign a pledge to talk with their patients about guns in the home. To date, at least 3,664 have done so.

In 2019, the American Academy of Family Medicine, with other leading physician and public health organizations, issued a “call to action,” recommending ways to reduce firearm-related injury and death in the United States. Physicians can and should address the issue, it said, by counseling patients about firearm safety.

“This is just another part of healthcare,” said Sarah C. Nosal, MD, a member of the board of directors of the AAFP, who practices at the Urban Horizons Family Health Center, New York.

Dr. Nosal said she asks about firearms during every well-child visit. She also focuses on patients with a history of depression or suicide attempts and those who have experienced domestic violence.

Are physicians counseling patients about gun safety?

A 2018 survey of physicians found that 73% of the 71 who responded agreed to discuss gun safety with at-risk patients. But just 5% said they always talk to those at-risk patients, according to Melanie G. Hagen, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Florida, Gainesville, who led the study. While the overwhelming majority agreed that gun safety is a public health issue, only 55% said they felt comfortable initiating conversations about firearms with their patients.

Have things changed since then? “Probably not,” Dr. Hagen said in an interview. She cited some reasons, at least in her state.

One obstacle is that many people, including physicians, believe that Florida’s physician gag law, which prohibited physicians from asking about a patient’s firearm ownership, was still in effect. The law, passed in 2011, was overturned in 2017. In her survey, 76% said they were aware it had been overturned. But that awareness appears not to be universal, she said.

In a 2020 report about physician involvement in promoting gun safety, researchers noted four main challenges: lingering fears about the overturned law and potential liability from violating it, feeling unprepared, worry that patients don’t want to discuss the topic, and lack of time to talk about it during a rushed office visit.

But recent research suggests that patients are often open to talking about gun safety, and another study found that if physicians are given educational materials on firearm safety, more will counsel patients about gun safety.

Are patients and parents receptive?

Parents welcome discussion from health care providers about gun safety, according to a study from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers asked roughly 100 parents to watch a short video about a firearm safety program designed to prevent accidents and suicides from guns. The program, still under study, involves a discussion between a parent and a pediatrician, with information given on secure storage of guns and the offering of a free cable lock.

The parents, about equally divided between gun owners and non–gun owners, said they were open to discussion about firearm safety, especially when the conversation involves their child’s pediatrician. Among the gun owners, only one in three said all their firearms were locked, unloaded, and stored properly. But after getting the safety information, 64% said they would change the way they stored their firearms.

A different program that offered pediatricians educational materials on firearm safety, as well as free firearm locks for distribution, increased the likelihood that the physicians would counsel patients on gun safety, other researchers reported.

Getting the conversation started

Some patients “bristle” when they’re asked about guns, Dr. Hagen said. Focusing on the “why” of the question can soften their response. One of her patients, a man in his 80s, had worked as a prison guard. After he was diagnosed with clinical depression, she asked him if he ever thought about ending his life. He said yes.

“And in Florida, I know a lot of people have guns,” she said. The state ranks second in the nation, with more than a half million registered weapons.

When Dr. Hagen asked him if he had firearms at home, he balked. Why did she need to know? “People do get defensive,” she said. “Luckily, I had a good relationship with this man, and he was willing to listen to me. If it’s someone I have a good relationship with, and I have this initial bristling, if I say: ‘I’m worried about you, I’m worried about your safety,’ that changes the entire conversation.”

She talked through the best plan for this patient, and he agreed to give his weapons to his son to keep.

Likewise, she talks with family members of dementia patients, urging them to be sure the weapons are stored and locked to prevent tragic accidents.

Dr. Nosal said reading the room is key. “Often, we are having the conversation with a parent with a child present,” she said. “Perhaps that is not the conversation the parent or guardian wanted to have with the child present.” In such a situation, she suggests asking the parent if they would talk about it solo.

“It can be a challenge to know the appropriate way to start the conversation,” Dr. Mathis said. The topic is not taught in medical school, although many experts think it should be. Dr. Hagen recently delivered a lecture to medical students about how to broach the topic with patients. She said she hopes it will become a regular event.

“It really comes down to being willing to be open and just ask that first question in a nonjudgmental way,” Dr. Mathis said. It helps, too, he said, for physicians to remember what he always tries to keep in mind: “My job isn’t politics, my job is health.”

Among the points Dr. Hagen makes in her lecture about talking to patients about guns are the following:

- Every day, more than 110 Americans are killed with guns.

- Gun violence accounts for just 1%-2% of those deaths, but mass shootings serve to shine a light on the issue of gun safety.

- 110,000 firearm injuries a year require medical or legal attention. Each year, more than 1,200 children in this country die from gun-related injuries.

- More than 33,000 people, on average, die in the United States each year from gun violence, including more than 21,000 from suicide.

- About 31% of all U.S. households have firearms; 22% of U.S. adults own one or more.

- Guns are 70% less likely to be stored locked and unloaded in homes where suicides or unintentional gun injuries occur.

- Action points: Identify risk, counsel patients at risk, act when someone is in imminent danger (such as unsafe practices or suicide threats).

- Focus on identifying adults who have a risk of inflicting violence on self or others.

- Focus on health and well-being with all; be conversational and educational.

- Clinicians should ask five crucial questions, all with an “L,” if firearms are in the home: Is it Loaded? Locked? Are Little children present? Is the owner feeling Low? Are they Learned [educated] in gun safety?

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts: EPA should assess risk of sunscreens’ UV filters

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

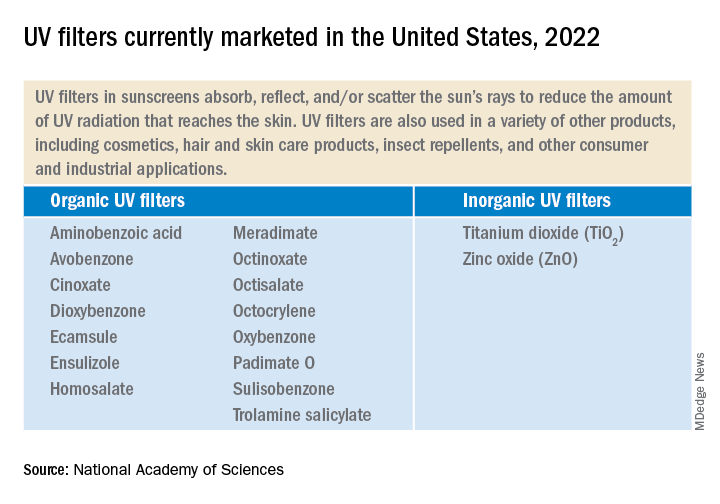

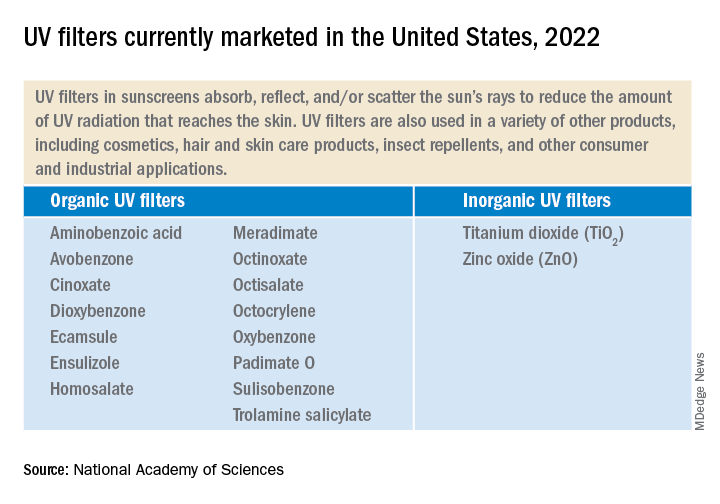

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA acts against sales of unapproved mole and skin tag products on Amazon, other sites

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.