User login

Best Practice Implementation and Clinical Inertia

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

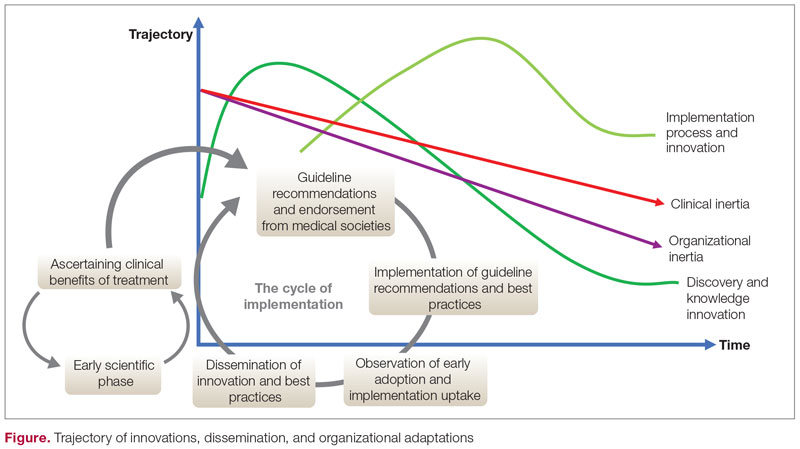

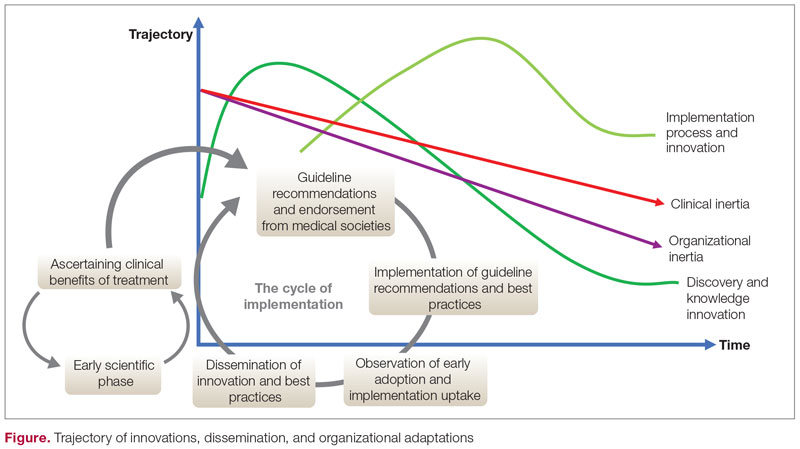

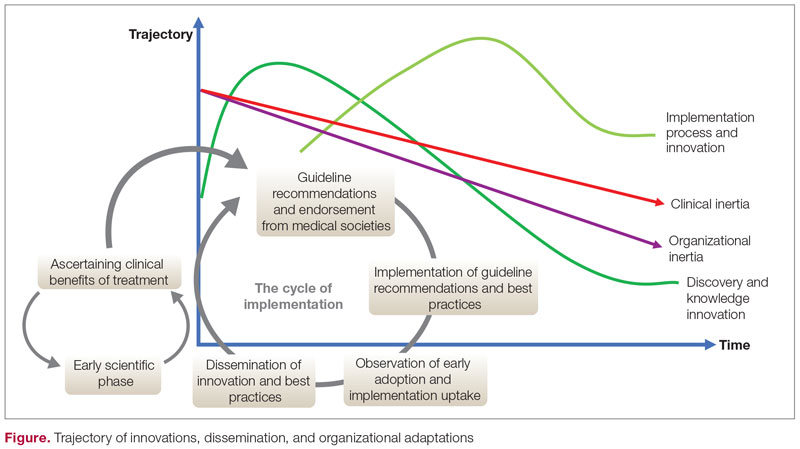

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

Effectiveness of Colonoscopy for Colorectal Cancer Screening in Reducing Cancer-Related Mortality: Interpreting the Results From Two Ongoing Randomized Trials

Study 1 Overview (Bretthauer et al)

Objective: To evaluate the impact of screening colonoscopy on colon cancer–related death.

Design: Randomized trial conducted in 4 European countries.

Setting and participants: Presumptively healthy men and women between the ages of 55 and 64 years were selected from population registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Eligible participants had not previously undergone screening. Patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer before trial entry were excluded.

Intervention: Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio to undergo colonoscopy screening by invitation or to no invitation and no screening. Participants were randomized using a computer-generated allocation algorithm. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and municipality.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the study was risk of colorectal cancer and related death after a median follow-up of 10 to 15 years. The main secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

Main results: The study reported follow-up data from 84,585 participants (89.1% of all participants originally included in the trial). The remaining participants were either excluded or data could not be included due to lack of follow-up data from the usual-care group. Men (50.1%) and women (49.9%) were equally represented. The median age at entry was 59 years. The median follow-up was 10 years. Characteristics were otherwise balanced. Good bowel preparation was reported in 91% of all participants. Cecal intubation was achieved in 96.8% of all participants. The percentage of patients who underwent screening was 42% for the group, but screening rates varied by country (33%-60%). Colorectal cancer was diagnosed at screening in 62 participants (0.5% of screening group). Adenomas were detected in 30.7% of participants; 15 patients had polypectomy-related major bleeding. There were no perforations.

The risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was 0.98% in the invited-to-screen group and 1.2% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.7-0.93). The reported number needed to invite to prevent 1 case of colon cancer in a 10-year period was 455. The risk of colorectal cancer–related death at 10 years was 0.28% in the invited-to-screen group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). An adjusted per-protocol analysis was performed to account for the estimated effect of screening if all participants assigned to the screening group underwent screening. In this analysis, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was decreased from 1.22% to 0.84% (risk ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.66-0.83).

Conclusion: Based on the results of this European randomized trial, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was lower among those who were invited to undergo screening.

Study 2 Overview (Forsberg et al)

Objective: To investigate the effect of colorectal cancer screening with once-only colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence.

Design: Randomized controlled trial in Sweden utilizing a population registry.

Setting and participants: Patients aged 60 years at the time of entry were identified from a population-based registry from the Swedish Tax Agency.

Intervention: Individuals were assigned by an independent statistician to once-only colonoscopy, 2 rounds of FIT 2 years apart, or a control group in which no intervention was performed. Patients were assigned in a 1:6 ratio for colonoscopy vs control and a 1:2 ratio for FIT vs control.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the trial was colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Main results: A total of 278,280 participants were included in the study from March 1, 2014, through December 31, 2020 (31,140 in the colonoscopy group, 60,300 in the FIT group, and 186,840 in the control group). Of those in the colonoscopy group, 35% underwent colonoscopy, and 55% of those in the FIT group participated in testing. Colorectal cancer was detected in 0.16% (49) of people in the colonoscopy group and 0.2% (121) of people in the FIT test group (relative risk, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.56-1.09). The advanced adenoma detection rate was 2.05% in the colonoscopy group and 1.61% in the FIT group (relative risk, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.15-1.41). There were 2 perforations noted in the colonoscopy group and 15 major bleeding events. More right-sided adenomas were detected in the colonoscopy group.

Conclusion: The results of the current study highlight similar detection rates in the colonoscopy and FIT group. Should further follow-up show a benefit in disease-specific mortality, such screening strategies could be translated into population-based screening programs.

Commentary

The first colonoscopy screening recommendations were established in the mid 1990s in the United States, and over the subsequent 2 decades colonoscopy has been the recommended method and main modality for colorectal cancer screening in this country. The advantage of colonoscopy over other screening modalities (sigmoidoscopy and fecal-based testing) is that it can examine the entire large bowel and allow for removal of potential precancerous lesions. However, data to support colonoscopy as a screening modality for colorectal cancer are largely based on cohort studies.1,2 These studies have reported a significant reduction in the incidence of colon cancer. Additionally, colorectal cancer mortality was notably lower in the screened populations. For example, one study among health professionals found a nearly 70% reduction in colorectal cancer mortality in those who underwent at least 1 screening colonoscopy.3

There has been a lack of randomized clinical data to validate the efficacy of colonoscopy screening for reducing colorectal cancer–related deaths. The current study by Bretthauer et al addresses an important need and enhances our understanding of the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. In this randomized trial involving more than 84,000 participants from Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, there was a noted 18% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer over a 10-year period in the intention-to-screen population. The reduction in the risk of death from colorectal cancer was not statistically significant (risk ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). These results are surprising and certainly raise the question as to whether previous studies overestimated the effectiveness of colonoscopy in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer–related deaths. There are several limitations to the Bretthauer et al study, however.

Perhaps the most important limitation is the fact that only 42% of participants in the invited-to-screen cohort underwent screening colonoscopy. Therefore, this raises the question of whether the efficacy noted is simply due to a lack of participation in the screening protocol. In the adjusted per-protocol analysis, colonoscopy was estimated to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by 31% and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death by around 50%. These findings are more in line with prior published studies regarding the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening. The authors plan to repeat this analysis at 15 years, and it is possible that the risk of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death can be reduced on subsequent follow-up.

While the results of the Bretthauer et al trial are important, randomized trials that directly compare the effectiveness of different colorectal cancer screening strategies are lacking. The Forsberg et al trial, also an ongoing study, seeks to address this vitally important gap in our current data. The SCREESCO trial is a study that compares the efficacy of colonoscopy with FIT every 2 years or no screening. The currently reported data are preliminary but show a similarly low rate of colonoscopy screening in those invited to do so (35%). This is a similar limitation to that noted in the Bretthauer et al study. Furthermore, there is some question regarding colonoscopy quality in this study, which had a very low reported adenoma detection rate.

While the current studies are important and provide quality randomized data on the effect of colorectal cancer screening, there remain many unanswered questions. Should the results presented by Bretthauer et al represent the current real-world scenario, then colonoscopy screening may not be viewed as an effective screening tool compared to simpler, less-invasive modalities (ie, FIT). Further follow-up from the SCREESCO trial will help shed light on this question. However, there are concerns with this study, including a very low participation rate, which could greatly underestimate the effectiveness of screening. Additional analysis and longer follow-up will be vital to fully understand the benefits of screening colonoscopy. In the meantime, screening remains an important tool for early detection of colorectal cancer and remains a category A recommendation by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.4

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colorectal cancer for persons between 45 and 75 years of age (category B recommendation for those aged 45 to 49 years per the United States Preventive Services Task Force). Stool-based tests and direct visualization tests are both endorsed as screening options. Further follow-up from the presented studies is needed to help shed light on the magnitude of benefit of these modalities.

Practice Points

- Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colon cancer in those aged 45 to 75 years.

- The optimal modality for screening and the impact of screening on cancer-related mortality requires longer- term follow-up from these ongoing studies.

–Daniel Isaac, DO, MS

1. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 May. Report No.: 20-05271-EF-1.

2. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1978-1998. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4417

3. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301969

4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal cancer: screening. Published May 18, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

Study 1 Overview (Bretthauer et al)

Objective: To evaluate the impact of screening colonoscopy on colon cancer–related death.

Design: Randomized trial conducted in 4 European countries.

Setting and participants: Presumptively healthy men and women between the ages of 55 and 64 years were selected from population registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Eligible participants had not previously undergone screening. Patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer before trial entry were excluded.

Intervention: Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio to undergo colonoscopy screening by invitation or to no invitation and no screening. Participants were randomized using a computer-generated allocation algorithm. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and municipality.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the study was risk of colorectal cancer and related death after a median follow-up of 10 to 15 years. The main secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

Main results: The study reported follow-up data from 84,585 participants (89.1% of all participants originally included in the trial). The remaining participants were either excluded or data could not be included due to lack of follow-up data from the usual-care group. Men (50.1%) and women (49.9%) were equally represented. The median age at entry was 59 years. The median follow-up was 10 years. Characteristics were otherwise balanced. Good bowel preparation was reported in 91% of all participants. Cecal intubation was achieved in 96.8% of all participants. The percentage of patients who underwent screening was 42% for the group, but screening rates varied by country (33%-60%). Colorectal cancer was diagnosed at screening in 62 participants (0.5% of screening group). Adenomas were detected in 30.7% of participants; 15 patients had polypectomy-related major bleeding. There were no perforations.

The risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was 0.98% in the invited-to-screen group and 1.2% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.7-0.93). The reported number needed to invite to prevent 1 case of colon cancer in a 10-year period was 455. The risk of colorectal cancer–related death at 10 years was 0.28% in the invited-to-screen group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). An adjusted per-protocol analysis was performed to account for the estimated effect of screening if all participants assigned to the screening group underwent screening. In this analysis, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was decreased from 1.22% to 0.84% (risk ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.66-0.83).

Conclusion: Based on the results of this European randomized trial, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was lower among those who were invited to undergo screening.

Study 2 Overview (Forsberg et al)

Objective: To investigate the effect of colorectal cancer screening with once-only colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence.

Design: Randomized controlled trial in Sweden utilizing a population registry.

Setting and participants: Patients aged 60 years at the time of entry were identified from a population-based registry from the Swedish Tax Agency.

Intervention: Individuals were assigned by an independent statistician to once-only colonoscopy, 2 rounds of FIT 2 years apart, or a control group in which no intervention was performed. Patients were assigned in a 1:6 ratio for colonoscopy vs control and a 1:2 ratio for FIT vs control.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the trial was colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Main results: A total of 278,280 participants were included in the study from March 1, 2014, through December 31, 2020 (31,140 in the colonoscopy group, 60,300 in the FIT group, and 186,840 in the control group). Of those in the colonoscopy group, 35% underwent colonoscopy, and 55% of those in the FIT group participated in testing. Colorectal cancer was detected in 0.16% (49) of people in the colonoscopy group and 0.2% (121) of people in the FIT test group (relative risk, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.56-1.09). The advanced adenoma detection rate was 2.05% in the colonoscopy group and 1.61% in the FIT group (relative risk, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.15-1.41). There were 2 perforations noted in the colonoscopy group and 15 major bleeding events. More right-sided adenomas were detected in the colonoscopy group.

Conclusion: The results of the current study highlight similar detection rates in the colonoscopy and FIT group. Should further follow-up show a benefit in disease-specific mortality, such screening strategies could be translated into population-based screening programs.

Commentary

The first colonoscopy screening recommendations were established in the mid 1990s in the United States, and over the subsequent 2 decades colonoscopy has been the recommended method and main modality for colorectal cancer screening in this country. The advantage of colonoscopy over other screening modalities (sigmoidoscopy and fecal-based testing) is that it can examine the entire large bowel and allow for removal of potential precancerous lesions. However, data to support colonoscopy as a screening modality for colorectal cancer are largely based on cohort studies.1,2 These studies have reported a significant reduction in the incidence of colon cancer. Additionally, colorectal cancer mortality was notably lower in the screened populations. For example, one study among health professionals found a nearly 70% reduction in colorectal cancer mortality in those who underwent at least 1 screening colonoscopy.3

There has been a lack of randomized clinical data to validate the efficacy of colonoscopy screening for reducing colorectal cancer–related deaths. The current study by Bretthauer et al addresses an important need and enhances our understanding of the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. In this randomized trial involving more than 84,000 participants from Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, there was a noted 18% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer over a 10-year period in the intention-to-screen population. The reduction in the risk of death from colorectal cancer was not statistically significant (risk ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). These results are surprising and certainly raise the question as to whether previous studies overestimated the effectiveness of colonoscopy in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer–related deaths. There are several limitations to the Bretthauer et al study, however.

Perhaps the most important limitation is the fact that only 42% of participants in the invited-to-screen cohort underwent screening colonoscopy. Therefore, this raises the question of whether the efficacy noted is simply due to a lack of participation in the screening protocol. In the adjusted per-protocol analysis, colonoscopy was estimated to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by 31% and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death by around 50%. These findings are more in line with prior published studies regarding the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening. The authors plan to repeat this analysis at 15 years, and it is possible that the risk of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death can be reduced on subsequent follow-up.

While the results of the Bretthauer et al trial are important, randomized trials that directly compare the effectiveness of different colorectal cancer screening strategies are lacking. The Forsberg et al trial, also an ongoing study, seeks to address this vitally important gap in our current data. The SCREESCO trial is a study that compares the efficacy of colonoscopy with FIT every 2 years or no screening. The currently reported data are preliminary but show a similarly low rate of colonoscopy screening in those invited to do so (35%). This is a similar limitation to that noted in the Bretthauer et al study. Furthermore, there is some question regarding colonoscopy quality in this study, which had a very low reported adenoma detection rate.

While the current studies are important and provide quality randomized data on the effect of colorectal cancer screening, there remain many unanswered questions. Should the results presented by Bretthauer et al represent the current real-world scenario, then colonoscopy screening may not be viewed as an effective screening tool compared to simpler, less-invasive modalities (ie, FIT). Further follow-up from the SCREESCO trial will help shed light on this question. However, there are concerns with this study, including a very low participation rate, which could greatly underestimate the effectiveness of screening. Additional analysis and longer follow-up will be vital to fully understand the benefits of screening colonoscopy. In the meantime, screening remains an important tool for early detection of colorectal cancer and remains a category A recommendation by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.4

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colorectal cancer for persons between 45 and 75 years of age (category B recommendation for those aged 45 to 49 years per the United States Preventive Services Task Force). Stool-based tests and direct visualization tests are both endorsed as screening options. Further follow-up from the presented studies is needed to help shed light on the magnitude of benefit of these modalities.

Practice Points

- Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colon cancer in those aged 45 to 75 years.

- The optimal modality for screening and the impact of screening on cancer-related mortality requires longer- term follow-up from these ongoing studies.

–Daniel Isaac, DO, MS

Study 1 Overview (Bretthauer et al)

Objective: To evaluate the impact of screening colonoscopy on colon cancer–related death.

Design: Randomized trial conducted in 4 European countries.

Setting and participants: Presumptively healthy men and women between the ages of 55 and 64 years were selected from population registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Eligible participants had not previously undergone screening. Patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer before trial entry were excluded.

Intervention: Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio to undergo colonoscopy screening by invitation or to no invitation and no screening. Participants were randomized using a computer-generated allocation algorithm. Patients were stratified by age, sex, and municipality.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the study was risk of colorectal cancer and related death after a median follow-up of 10 to 15 years. The main secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

Main results: The study reported follow-up data from 84,585 participants (89.1% of all participants originally included in the trial). The remaining participants were either excluded or data could not be included due to lack of follow-up data from the usual-care group. Men (50.1%) and women (49.9%) were equally represented. The median age at entry was 59 years. The median follow-up was 10 years. Characteristics were otherwise balanced. Good bowel preparation was reported in 91% of all participants. Cecal intubation was achieved in 96.8% of all participants. The percentage of patients who underwent screening was 42% for the group, but screening rates varied by country (33%-60%). Colorectal cancer was diagnosed at screening in 62 participants (0.5% of screening group). Adenomas were detected in 30.7% of participants; 15 patients had polypectomy-related major bleeding. There were no perforations.

The risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was 0.98% in the invited-to-screen group and 1.2% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.7-0.93). The reported number needed to invite to prevent 1 case of colon cancer in a 10-year period was 455. The risk of colorectal cancer–related death at 10 years was 0.28% in the invited-to-screen group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). An adjusted per-protocol analysis was performed to account for the estimated effect of screening if all participants assigned to the screening group underwent screening. In this analysis, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was decreased from 1.22% to 0.84% (risk ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.66-0.83).

Conclusion: Based on the results of this European randomized trial, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was lower among those who were invited to undergo screening.

Study 2 Overview (Forsberg et al)

Objective: To investigate the effect of colorectal cancer screening with once-only colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence.

Design: Randomized controlled trial in Sweden utilizing a population registry.

Setting and participants: Patients aged 60 years at the time of entry were identified from a population-based registry from the Swedish Tax Agency.

Intervention: Individuals were assigned by an independent statistician to once-only colonoscopy, 2 rounds of FIT 2 years apart, or a control group in which no intervention was performed. Patients were assigned in a 1:6 ratio for colonoscopy vs control and a 1:2 ratio for FIT vs control.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint of the trial was colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Main results: A total of 278,280 participants were included in the study from March 1, 2014, through December 31, 2020 (31,140 in the colonoscopy group, 60,300 in the FIT group, and 186,840 in the control group). Of those in the colonoscopy group, 35% underwent colonoscopy, and 55% of those in the FIT group participated in testing. Colorectal cancer was detected in 0.16% (49) of people in the colonoscopy group and 0.2% (121) of people in the FIT test group (relative risk, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.56-1.09). The advanced adenoma detection rate was 2.05% in the colonoscopy group and 1.61% in the FIT group (relative risk, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.15-1.41). There were 2 perforations noted in the colonoscopy group and 15 major bleeding events. More right-sided adenomas were detected in the colonoscopy group.

Conclusion: The results of the current study highlight similar detection rates in the colonoscopy and FIT group. Should further follow-up show a benefit in disease-specific mortality, such screening strategies could be translated into population-based screening programs.

Commentary

The first colonoscopy screening recommendations were established in the mid 1990s in the United States, and over the subsequent 2 decades colonoscopy has been the recommended method and main modality for colorectal cancer screening in this country. The advantage of colonoscopy over other screening modalities (sigmoidoscopy and fecal-based testing) is that it can examine the entire large bowel and allow for removal of potential precancerous lesions. However, data to support colonoscopy as a screening modality for colorectal cancer are largely based on cohort studies.1,2 These studies have reported a significant reduction in the incidence of colon cancer. Additionally, colorectal cancer mortality was notably lower in the screened populations. For example, one study among health professionals found a nearly 70% reduction in colorectal cancer mortality in those who underwent at least 1 screening colonoscopy.3

There has been a lack of randomized clinical data to validate the efficacy of colonoscopy screening for reducing colorectal cancer–related deaths. The current study by Bretthauer et al addresses an important need and enhances our understanding of the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. In this randomized trial involving more than 84,000 participants from Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, there was a noted 18% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer over a 10-year period in the intention-to-screen population. The reduction in the risk of death from colorectal cancer was not statistically significant (risk ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). These results are surprising and certainly raise the question as to whether previous studies overestimated the effectiveness of colonoscopy in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer–related deaths. There are several limitations to the Bretthauer et al study, however.

Perhaps the most important limitation is the fact that only 42% of participants in the invited-to-screen cohort underwent screening colonoscopy. Therefore, this raises the question of whether the efficacy noted is simply due to a lack of participation in the screening protocol. In the adjusted per-protocol analysis, colonoscopy was estimated to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by 31% and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death by around 50%. These findings are more in line with prior published studies regarding the efficacy of colorectal cancer screening. The authors plan to repeat this analysis at 15 years, and it is possible that the risk of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death can be reduced on subsequent follow-up.

While the results of the Bretthauer et al trial are important, randomized trials that directly compare the effectiveness of different colorectal cancer screening strategies are lacking. The Forsberg et al trial, also an ongoing study, seeks to address this vitally important gap in our current data. The SCREESCO trial is a study that compares the efficacy of colonoscopy with FIT every 2 years or no screening. The currently reported data are preliminary but show a similarly low rate of colonoscopy screening in those invited to do so (35%). This is a similar limitation to that noted in the Bretthauer et al study. Furthermore, there is some question regarding colonoscopy quality in this study, which had a very low reported adenoma detection rate.

While the current studies are important and provide quality randomized data on the effect of colorectal cancer screening, there remain many unanswered questions. Should the results presented by Bretthauer et al represent the current real-world scenario, then colonoscopy screening may not be viewed as an effective screening tool compared to simpler, less-invasive modalities (ie, FIT). Further follow-up from the SCREESCO trial will help shed light on this question. However, there are concerns with this study, including a very low participation rate, which could greatly underestimate the effectiveness of screening. Additional analysis and longer follow-up will be vital to fully understand the benefits of screening colonoscopy. In the meantime, screening remains an important tool for early detection of colorectal cancer and remains a category A recommendation by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.4

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colorectal cancer for persons between 45 and 75 years of age (category B recommendation for those aged 45 to 49 years per the United States Preventive Services Task Force). Stool-based tests and direct visualization tests are both endorsed as screening options. Further follow-up from the presented studies is needed to help shed light on the magnitude of benefit of these modalities.

Practice Points

- Current guidelines continue to strongly recommend screening for colon cancer in those aged 45 to 75 years.

- The optimal modality for screening and the impact of screening on cancer-related mortality requires longer- term follow-up from these ongoing studies.

–Daniel Isaac, DO, MS

1. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 May. Report No.: 20-05271-EF-1.

2. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1978-1998. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4417

3. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301969

4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal cancer: screening. Published May 18, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

1. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 May. Report No.: 20-05271-EF-1.

2. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1978-1998. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4417

3. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095-1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301969

4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal cancer: screening. Published May 18, 2021. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

The Long Arc of Justice for Veteran Benefits

This Veterans Day we honor the passing of the largest expansion of veterans benefits and services in history. On August 10, 2022, President Biden signed the Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act. This act was named for a combat medic who died of a rare form of lung cancer believed to be the result of a toxic military exposure. His widow was present during the President's State of the Union address that urged Congress to pass the legislation.2

Like all other congressional bills and government regulations, the PACT Act is complex in its details and still a work in progress. Simply put, the PACT Act expands and/or extends enrollment for a group of previously ineligible veterans. Eligibility will no longer require that veterans demonstrate a service-connected disability due to toxic exposure, including those from burn pits. This has long been a barrier for many veterans seeking benefits and not just related to toxic exposures. Logistical barriers and documentary losses have prevented many service members from establishing a clean chain of evidence for the injuries or illnesses they sustained while in uniform.

The new process is a massive step forward by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to establish high standards of procedural justice for settling beneficiary claims. The PACT Act removes the burden from the shoulders of the veteran and places it squarely on the VA to demonstrate that > 20 different medical conditions--primarily cancers and respiratory illnesses--are linked to toxic exposure. The VA must establish that exposure occurred to cohorts of service members in specific theaters and time frames. A veteran who served in that area and period and has one of the indexed illnesses is presumed to have been exposed in the line of duty.3,4

As a result, the VA instituted a new screening process to determine that toxic military exposures (a) led to illness; and (b) both exposure and illness are connected to service. According to the VA, the new process is evidence based, transparent, and allows the VA to fast-track policy decisions related to exposures. The PACT Act includes a provision intended to promote sustained implementation and prevent the program from succumbing as so many new initiatives have to inadequate adoption. VA is required to deploy its considerable internal research capacity to collaborate with external partners in and outside government to study military members with toxic exposures.4

Congress had initially proposed that the provisions of the PACT ACT would take effect in 2026, providing time to ramp up the process. The White House and VA telescoped that time line so veterans can begin now to apply for benefits that they could foreseeably receive in 2023. However, a long-standing problem for the VA has been unfunded agency or congressional mandates. These have often end in undermining the legislative intention or policy purpose of the program undermining their legislative intention or policy purpose through staffing shortages, leading to lack of or delayed access. The PACT Act promises to eschew the infamous Phoenix problem by providing increased personnel, training infrastructure, and technology resources for both the Veterans Benefit Administration and the Veterans Health Administration. Ironically, many seasoned VA observers expect the PACT expansion will lead to even larger backlogs of claims as hundreds of newly eligible veterans are added to the extant rolls of those seeking benefits.5

An estimated 1 in 5 veterans may be entitled to PACT benefits. The PACT Act is the latest of a long uneven movement toward distributive justice for veteran benefits and services. It is fitting in the month of Veterans Day 2022 to trace that trajectory. Congress first passed veteran benefits legislation in 1917, focused on soldiers with disabilities. This resulted in a massive investment in building hospitals. Ironically, part of the impetus for VA health care was an earlier toxic military exposure. World War I service members suffered from the detrimental effects of mustard gas among other chemical byproducts. In 1924, VA benefits and services underwent a momentous opening to include individuals with non-service-connected disabilities. Four years later, the VA tent became even bigger, welcoming women, National Guard, and militia members to receive care under its auspices.6

The PACT Act is a fitting memorial for Veterans Day as an increasingly divided country presents a unified response to veterans and their survivors exposed to a variety of toxins across multiple wars. The PACT Act was hard won with veterans and their advocates having to fight years of political bickering, government abdication of accountability, and scientific sparring before this bipartisan legislation passed.7 It covers Vietnam War veterans with several conditions due to Agent Orange exposure; Gulf War and post-9/11 veterans with cancer and respiratory conditions; and the service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq afflicted with illnesses due to the smoke of burn pits and other toxins.

As many areas of the country roll back LGBTQ+ rights to health care and social services, the VA has emerged as a leader in the movement for diversity and inclusion. VA Secretary McDonough provided a pathway to VA eligibility for other than honorably discharged veterans, including those LGBTQ+ persons discharged under Don't Ask, Don't Tell.8 Lest we take this new inclusivity for granted, we should never forget that this journey toward equity for the military and VA has been long, slow, and uneven. There are many difficult miles yet to travel if we are to achieve liberty and justice for veteran members of racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations. Even the PACT Act does not cover all putative exposures to toxins.9 Yet it is a significant step closer to fulfilling the motto of the VA LGBTQ+ program: to serve all who served.10

- Parker T. Of justice and the conscience. In: Ten Sermons of Religion. Crosby, Nichols and Company; 1853:66-85.

- The White House. Fact sheet: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America's veterans. August 9, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans

- Shane L. Vets can apply for all PACT benefits now after VA speeds up law. Military Times. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/burn-pits/2022/09/01/vets-can-apply-for-all-pact-act-benefits-now-after-va-speeds-up-law

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The PACT Act and your VA benefits. Updated September 28, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/resources/the-pact-act-and-your-va-benefits

- Wentling N. Discharged LGBTQ+ veterans now eligible for benefits under new guidance issued by VA. Stars & Stripes. September 20, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2021-09-20/veterans-affairs-dont-ask-dont-tell-benefits-lgbt-discharges-2956761.html

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA History Office. History--Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Updated May 27, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HISTORY/VA_History/Overview.asp

- Atkins D, Kilbourne A, Lipson L. Health equity research in the Veterans Health Administration: we've come far but aren't there yet. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 4):S525-S526. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302216

- Stack MK. The soldiers came home sick. The government denied it was responsible. New York Times. Updated January 16, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/11/magazine/military-burn-pits.html

- Namaz A, Sagalyn D. VA secretary discusses health care overhaul helping veterans exposed to toxic burn pits. PBS NewsHour. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/va-secretary-discusses-health-care-overhaul-helping-veterans-exposed-to-toxic-burn-pits

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Patient Care Services. VHA LGBTQ+ health program. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/lgbt

This Veterans Day we honor the passing of the largest expansion of veterans benefits and services in history. On August 10, 2022, President Biden signed the Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act. This act was named for a combat medic who died of a rare form of lung cancer believed to be the result of a toxic military exposure. His widow was present during the President's State of the Union address that urged Congress to pass the legislation.2

Like all other congressional bills and government regulations, the PACT Act is complex in its details and still a work in progress. Simply put, the PACT Act expands and/or extends enrollment for a group of previously ineligible veterans. Eligibility will no longer require that veterans demonstrate a service-connected disability due to toxic exposure, including those from burn pits. This has long been a barrier for many veterans seeking benefits and not just related to toxic exposures. Logistical barriers and documentary losses have prevented many service members from establishing a clean chain of evidence for the injuries or illnesses they sustained while in uniform.

The new process is a massive step forward by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to establish high standards of procedural justice for settling beneficiary claims. The PACT Act removes the burden from the shoulders of the veteran and places it squarely on the VA to demonstrate that > 20 different medical conditions--primarily cancers and respiratory illnesses--are linked to toxic exposure. The VA must establish that exposure occurred to cohorts of service members in specific theaters and time frames. A veteran who served in that area and period and has one of the indexed illnesses is presumed to have been exposed in the line of duty.3,4

As a result, the VA instituted a new screening process to determine that toxic military exposures (a) led to illness; and (b) both exposure and illness are connected to service. According to the VA, the new process is evidence based, transparent, and allows the VA to fast-track policy decisions related to exposures. The PACT Act includes a provision intended to promote sustained implementation and prevent the program from succumbing as so many new initiatives have to inadequate adoption. VA is required to deploy its considerable internal research capacity to collaborate with external partners in and outside government to study military members with toxic exposures.4

Congress had initially proposed that the provisions of the PACT ACT would take effect in 2026, providing time to ramp up the process. The White House and VA telescoped that time line so veterans can begin now to apply for benefits that they could foreseeably receive in 2023. However, a long-standing problem for the VA has been unfunded agency or congressional mandates. These have often end in undermining the legislative intention or policy purpose of the program undermining their legislative intention or policy purpose through staffing shortages, leading to lack of or delayed access. The PACT Act promises to eschew the infamous Phoenix problem by providing increased personnel, training infrastructure, and technology resources for both the Veterans Benefit Administration and the Veterans Health Administration. Ironically, many seasoned VA observers expect the PACT expansion will lead to even larger backlogs of claims as hundreds of newly eligible veterans are added to the extant rolls of those seeking benefits.5

An estimated 1 in 5 veterans may be entitled to PACT benefits. The PACT Act is the latest of a long uneven movement toward distributive justice for veteran benefits and services. It is fitting in the month of Veterans Day 2022 to trace that trajectory. Congress first passed veteran benefits legislation in 1917, focused on soldiers with disabilities. This resulted in a massive investment in building hospitals. Ironically, part of the impetus for VA health care was an earlier toxic military exposure. World War I service members suffered from the detrimental effects of mustard gas among other chemical byproducts. In 1924, VA benefits and services underwent a momentous opening to include individuals with non-service-connected disabilities. Four years later, the VA tent became even bigger, welcoming women, National Guard, and militia members to receive care under its auspices.6

The PACT Act is a fitting memorial for Veterans Day as an increasingly divided country presents a unified response to veterans and their survivors exposed to a variety of toxins across multiple wars. The PACT Act was hard won with veterans and their advocates having to fight years of political bickering, government abdication of accountability, and scientific sparring before this bipartisan legislation passed.7 It covers Vietnam War veterans with several conditions due to Agent Orange exposure; Gulf War and post-9/11 veterans with cancer and respiratory conditions; and the service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq afflicted with illnesses due to the smoke of burn pits and other toxins.

As many areas of the country roll back LGBTQ+ rights to health care and social services, the VA has emerged as a leader in the movement for diversity and inclusion. VA Secretary McDonough provided a pathway to VA eligibility for other than honorably discharged veterans, including those LGBTQ+ persons discharged under Don't Ask, Don't Tell.8 Lest we take this new inclusivity for granted, we should never forget that this journey toward equity for the military and VA has been long, slow, and uneven. There are many difficult miles yet to travel if we are to achieve liberty and justice for veteran members of racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations. Even the PACT Act does not cover all putative exposures to toxins.9 Yet it is a significant step closer to fulfilling the motto of the VA LGBTQ+ program: to serve all who served.10

This Veterans Day we honor the passing of the largest expansion of veterans benefits and services in history. On August 10, 2022, President Biden signed the Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act. This act was named for a combat medic who died of a rare form of lung cancer believed to be the result of a toxic military exposure. His widow was present during the President's State of the Union address that urged Congress to pass the legislation.2

Like all other congressional bills and government regulations, the PACT Act is complex in its details and still a work in progress. Simply put, the PACT Act expands and/or extends enrollment for a group of previously ineligible veterans. Eligibility will no longer require that veterans demonstrate a service-connected disability due to toxic exposure, including those from burn pits. This has long been a barrier for many veterans seeking benefits and not just related to toxic exposures. Logistical barriers and documentary losses have prevented many service members from establishing a clean chain of evidence for the injuries or illnesses they sustained while in uniform.

The new process is a massive step forward by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to establish high standards of procedural justice for settling beneficiary claims. The PACT Act removes the burden from the shoulders of the veteran and places it squarely on the VA to demonstrate that > 20 different medical conditions--primarily cancers and respiratory illnesses--are linked to toxic exposure. The VA must establish that exposure occurred to cohorts of service members in specific theaters and time frames. A veteran who served in that area and period and has one of the indexed illnesses is presumed to have been exposed in the line of duty.3,4

As a result, the VA instituted a new screening process to determine that toxic military exposures (a) led to illness; and (b) both exposure and illness are connected to service. According to the VA, the new process is evidence based, transparent, and allows the VA to fast-track policy decisions related to exposures. The PACT Act includes a provision intended to promote sustained implementation and prevent the program from succumbing as so many new initiatives have to inadequate adoption. VA is required to deploy its considerable internal research capacity to collaborate with external partners in and outside government to study military members with toxic exposures.4

Congress had initially proposed that the provisions of the PACT ACT would take effect in 2026, providing time to ramp up the process. The White House and VA telescoped that time line so veterans can begin now to apply for benefits that they could foreseeably receive in 2023. However, a long-standing problem for the VA has been unfunded agency or congressional mandates. These have often end in undermining the legislative intention or policy purpose of the program undermining their legislative intention or policy purpose through staffing shortages, leading to lack of or delayed access. The PACT Act promises to eschew the infamous Phoenix problem by providing increased personnel, training infrastructure, and technology resources for both the Veterans Benefit Administration and the Veterans Health Administration. Ironically, many seasoned VA observers expect the PACT expansion will lead to even larger backlogs of claims as hundreds of newly eligible veterans are added to the extant rolls of those seeking benefits.5

An estimated 1 in 5 veterans may be entitled to PACT benefits. The PACT Act is the latest of a long uneven movement toward distributive justice for veteran benefits and services. It is fitting in the month of Veterans Day 2022 to trace that trajectory. Congress first passed veteran benefits legislation in 1917, focused on soldiers with disabilities. This resulted in a massive investment in building hospitals. Ironically, part of the impetus for VA health care was an earlier toxic military exposure. World War I service members suffered from the detrimental effects of mustard gas among other chemical byproducts. In 1924, VA benefits and services underwent a momentous opening to include individuals with non-service-connected disabilities. Four years later, the VA tent became even bigger, welcoming women, National Guard, and militia members to receive care under its auspices.6

The PACT Act is a fitting memorial for Veterans Day as an increasingly divided country presents a unified response to veterans and their survivors exposed to a variety of toxins across multiple wars. The PACT Act was hard won with veterans and their advocates having to fight years of political bickering, government abdication of accountability, and scientific sparring before this bipartisan legislation passed.7 It covers Vietnam War veterans with several conditions due to Agent Orange exposure; Gulf War and post-9/11 veterans with cancer and respiratory conditions; and the service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq afflicted with illnesses due to the smoke of burn pits and other toxins.

As many areas of the country roll back LGBTQ+ rights to health care and social services, the VA has emerged as a leader in the movement for diversity and inclusion. VA Secretary McDonough provided a pathway to VA eligibility for other than honorably discharged veterans, including those LGBTQ+ persons discharged under Don't Ask, Don't Tell.8 Lest we take this new inclusivity for granted, we should never forget that this journey toward equity for the military and VA has been long, slow, and uneven. There are many difficult miles yet to travel if we are to achieve liberty and justice for veteran members of racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations. Even the PACT Act does not cover all putative exposures to toxins.9 Yet it is a significant step closer to fulfilling the motto of the VA LGBTQ+ program: to serve all who served.10

- Parker T. Of justice and the conscience. In: Ten Sermons of Religion. Crosby, Nichols and Company; 1853:66-85.

- The White House. Fact sheet: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America's veterans. August 9, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans

- Shane L. Vets can apply for all PACT benefits now after VA speeds up law. Military Times. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/burn-pits/2022/09/01/vets-can-apply-for-all-pact-act-benefits-now-after-va-speeds-up-law

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The PACT Act and your VA benefits. Updated September 28, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/resources/the-pact-act-and-your-va-benefits

- Wentling N. Discharged LGBTQ+ veterans now eligible for benefits under new guidance issued by VA. Stars & Stripes. September 20, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2021-09-20/veterans-affairs-dont-ask-dont-tell-benefits-lgbt-discharges-2956761.html

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA History Office. History--Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Updated May 27, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HISTORY/VA_History/Overview.asp

- Atkins D, Kilbourne A, Lipson L. Health equity research in the Veterans Health Administration: we've come far but aren't there yet. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 4):S525-S526. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302216

- Stack MK. The soldiers came home sick. The government denied it was responsible. New York Times. Updated January 16, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/11/magazine/military-burn-pits.html

- Namaz A, Sagalyn D. VA secretary discusses health care overhaul helping veterans exposed to toxic burn pits. PBS NewsHour. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/va-secretary-discusses-health-care-overhaul-helping-veterans-exposed-to-toxic-burn-pits

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Patient Care Services. VHA LGBTQ+ health program. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/lgbt

- Parker T. Of justice and the conscience. In: Ten Sermons of Religion. Crosby, Nichols and Company; 1853:66-85.

- The White House. Fact sheet: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America's veterans. August 9, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans

- Shane L. Vets can apply for all PACT benefits now after VA speeds up law. Military Times. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/burn-pits/2022/09/01/vets-can-apply-for-all-pact-act-benefits-now-after-va-speeds-up-law

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The PACT Act and your VA benefits. Updated September 28, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/resources/the-pact-act-and-your-va-benefits

- Wentling N. Discharged LGBTQ+ veterans now eligible for benefits under new guidance issued by VA. Stars & Stripes. September 20, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2021-09-20/veterans-affairs-dont-ask-dont-tell-benefits-lgbt-discharges-2956761.html

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA History Office. History--Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Updated May 27, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HISTORY/VA_History/Overview.asp

- Atkins D, Kilbourne A, Lipson L. Health equity research in the Veterans Health Administration: we've come far but aren't there yet. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 4):S525-S526. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302216

- Stack MK. The soldiers came home sick. The government denied it was responsible. New York Times. Updated January 16, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/11/magazine/military-burn-pits.html

- Namaz A, Sagalyn D. VA secretary discusses health care overhaul helping veterans exposed to toxic burn pits. PBS NewsHour. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/va-secretary-discusses-health-care-overhaul-helping-veterans-exposed-to-toxic-burn-pits

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Patient Care Services. VHA LGBTQ+ health program. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/lgbt

Medicaid Expansion and Veterans’ Reliance on the VA for Depression Care

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing care for more than 9 million veterans.1 With veterans experiencing mental health conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and other serious mental illnesses (SMI) at higher rates compared with the general population, the VA plays an important role in the provision of mental health services.2-5 Since the implementation of its Mental Health Strategic Plan in 2004, the VA has overseen the development of a wide array of mental health programs geared toward the complex needs of veterans. Research has demonstrated VA care outperforming Medicaid-reimbursed services in terms of the percentage of veterans filling antidepressants for at least 12 weeks after initiation of treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD), as well as posthospitalization follow-up.6

Eligible veterans enrolled in the VA often also seek non-VA care. Medicaid covers nearly 10% of all nonelderly veterans, and of these veterans, 39% rely solely on Medicaid for health care access.7 Today, Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the US, providing coverage for approximately 27% of Americans who have SMI and helping fulfill unmet mental health needs.8,9 Understanding which of these systems veterans choose to use, and under which circumstances, is essential in guiding the allocation of limited health care resources.10

Beyond Medicaid, alternatives to VA care may include TRICARE, Medicare, Indian Health Services, and employer-based or self-purchased private insurance. While these options potentially increase convenience, choice, and access to health care practitioners (HCPs) and services not available at local VA systems, cross-system utilization with poor integration may cause care coordination and continuity problems, such as medication mismanagement and opioid overdose, unnecessary duplicate utilization, and possible increased mortality.11-15 As recent national legislative changes, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, and the VA MISSION Act, continue to shift the health care landscape for veterans, questions surrounding how veterans are changing their health care use become significant.16,17

Here, we approach the impacts of Medicaid expansion on veterans’ reliance on the VA for mental health services with a unique lens. We leverage a difference-in-difference design to study 2 historical Medicaid expansions in Arizona (AZ) and New York (NY), which extended eligibility to childless adults in 2001. Prior Medicaid dual-eligible mental health research investigated reliance shifts during the immediate postenrollment year in a subset of veterans newly enrolled in Medicaid.18 However, this study took place in a period of relative policy stability. In contrast, we investigate the potential effects of a broad policy shift by analyzing state-level changes in veterans’ reliance over 6 years after a statewide Medicaid expansion. We match expansion states with demographically similar nonexpansion states to account for unobserved trends and confounding effects. Prior studies have used this method to evaluate post-Medicaid expansion mortality changes and changes in veteran dual enrollment and hospitalizations.10,19 While a study of ACA Medicaid expansion states would be ideal, Medicaid data from most states were only available through 2014 at the time of this analysis. Our study offers a quasi-experimental framework leveraging longitudinal data that can be applied as more post-ACA data become available.