User login

Conservatism spreads in prostate cancer

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

The Dyad Model for Interprofessional Academic Patient Aligned Care Teams

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). As part of VA’s New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs are using VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents and students, advanced practice nurses (APRNs), undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions trainees (such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants) for primary care practice. The CoEPCE sites are developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula to prepare learners from relevant professions to practice in patientcentered, interprofessional team-based primary care settings. Patient aligned care teams (PACTs) that have 2 or more health professions trainees engaged in learning, working, and teaching are known as interprofessional academic PACTs (iAPACTs), which is the preferred model for the VA.

The Cleveland Transforming Outpatient Care (TOPC)-CoEPCE was designed for collaborative learning among nurse practitioner (NP) students and physician residents. Its robust curriculum consists of a dedicated half-day of didactics for all learners, interprofessional quality improvement projects, panel management sessions, and primary care clinical sessions for nursing and physician learners that include the dyad workplace learning model.

In 2015, the OAA lead evaluator observed the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model process, reviewed background documents, and conducted 10 open-ended interviews with TOPC-CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, faculty, and affiliate leadership. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the TOPCCoEPC dyad model to participants, veterans, VA, and affiliates.

Lack of Interprofessional Learning Opportunities

Current health care professional education models typically do not have many workplace learning settings where physician and nursing trainees learn together and provide patient-centered care. Often in a shared clinical environment, trainees may engage in “parallel play,” which can result in physician trainees and NP students learning independently and being ill-prepared to practice effectively together.

Moreover, trainees from different professions have different learning needs. For example, less experienced NP students require greater time, supervision, and evaluation of their patient care skills. On the other hand, senior physician residents, who require less clinical instruction, need to be engaged in ways that provide opportunities to enhance their ambulatory teaching skills. Although enhancement of resident teaching skills occurs in the inpatient hospital setting, there have been limited teaching experiences for residents in a primary care setting where the instruction is traditionally faculty-based. The TOPCCoEPCE dyad model offers an opportunity to simultaneously provide trainees with a true interprofessional experience through advancement of skills in primary care, teamwork, and teaching, while addressing health care needs.

The Dyad Model

In 2011, the OAA directed COEPCE sites to develop innovative curriculum and workplace learning strategies to create more opportunities for physician and NP trainees to work as a team. There is evidence demonstrating that when students develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill set, care procedures, and values, patient care is improved.1 Further, training in pairs can be an effective strategy in education of preclerkship medical students.2 In April 2013, TOPC-CoEPCE staff asked representatives from the Student-Run Clinic at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, Ohio, to present their approach to pairing nursing and medical students in clinic under supervision by volunteer faculty. However, formal structure and curricular objectives were lacking. To address diverse TOPCCoEPCE trainee needs and create a team approach to patient care, the staff formalized and developed a workplace curriculum called the dyad model. Specifically, the model pairs 1 NP student with a senior (PGY2 or PGY3) physician resident to care for ambulatory patients as a dyad teaching/learning team. The dyad model has 3 goals: improving clinical performance, learning team dynamics, and improving the physician resident’s teaching skills in an ambulatory setting.

Planning and Implementation

Planning the dyad model took 4 months. Initial conceptualization of the model was discussed at TOPC-CoEPCE infrastructure meetings. Workgroups with representatives from medicine, nursing, evaluation and medical center administration were formed to finalize the model. The workgroups met weekly or biweekly to develop protocols for scheduling, ongoing monitoring and assessment, microteaching session curriculum development, and logistics. A pilot program was initiated for 1 month with 2 dyads to monitor learner progress and improve components, such as adjusting the patient exam start times and curriculum. In maintaining the program, the workgroups continue to meet monthly to check for areas for further improvement and maintain dissemination activities.

Curriculum

The dyad model is a novel opportunity to have trainees from different professions not only collaborate in the care of the same patient at the same time, but also negotiate their respective responsibilities preand postvisit. The experience focuses on interprofessional relationships and open communication. TOPC-CoEPCE used a modified version of the RIME (Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator) model called the O-RIME model (Table 1), which includes an observer (O) phase as the first component for clarification about a beginners’ role.3,4

Four dyad pairs provide collaborative clinical care for veterans during one halfday session per week. The dyad conducts 4 hour-long patient visits per session. To be a dyad participant, the physician residents must be at least a PGY2, and their schedule must align with the NP student clinic schedule. Participation is mandatory for both NP students and physician residents. TOPC staff assemble the pairs.

The dyad model requires knowledge of the clinical and curricular interface and when to block the dyad team members’ schedules for 4 patients instead of 6. Physician residents are in the TOPC-CoEPCE for 12 weeks and then on inpatient for 12 weeks. Depending on the nursing school affiliate, NP student trainees are scheduled for either a 6- or 12-month TOPC-CoEPCE experience. For the 12-month NP students, they are paired with up to 4 internal medicine residents over the course of their dyad participation so they can experience different teaching styles of each resident while developing more varied interprofessional communication skills.

Faculty Roles and Development

The dyad model also seeks to address the paucity of deliberate interprofessional precepting in academic primary care settings. The TOPC-CoEPCE staff decided to use the existing primary care clinic faculty development series bimonthly for 1 hour each. The dyad model team members presented sessions covering foundational material in interprofessional teaching and precepting skills, which prepare faculty to precept for different professions and the dyad teams. It is important for preceptors to develop awareness of learners from different professions and the corresponding educational trajectories, so they can communicate with paired trainees of differing professions and academic levels who may require different levels of discussion.

Resources

By utilizing advanced residents as teachers, faculty were able to increase the number of learners in the clinic without increasing the number preceptors. For example, precepting a student typically requires more preceptor time, especially when we consider that the preceptor must also see the patient. The TOPC-CoEPCE faculty run the microteaching sessions, and an evaluator monitors and evaluates the program. The microteaching sessions were derived from several teaching resources.

Monitoring and Assessment

The Cleveland TOPC administered 2 different surveys developed by the Dyad Model Infrastructure and Evaluation workgroup. A 7-item survey assesses dyad team communication and interprofessional team functioning, and an 8-item survey assesses the teaching/mentoring of the resident as teacher. Both were collected from all participants to evaluate the residents’ and students’ point of view. Surveys are collected in the first and last weeks of the dyad experience. Feedback from participants has been used to make improvements to the program (eg, monitoring how the dyad teams are functioning, coaching individual learners).

Partnerships

In addition to TOPC staff and faculty support and engagement, the initiative has benefited from partnerships with VA clinic staff and with the associated academic affiliates. In particular, the Associate Chief of General Internal Medicine at the Cleveland VA medical center and interim clinic director helped institute changes to the primary care clinic structure. Additionally, buy-in from the clinic nurse manager was needed to make adjustments with staff schedules and clinic resources. To implement the dyad model, the clinic director had to approve reductions in the residents’ clinic loads for the mornings when they participated.

The NP affiliates’ faculty at the schools of nursing are integral partners who assist with student recruitment and participate in the planning and refinement of TOPCCoEPCE components. The Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at CWRU and the Breen School of Nursing of Ursuline College in Pepper Pike, Ohio, were involved in the planning stages and continue to receive monthly updates from TOPC-CoEPCE. Similarly, the CWRU School of Medicine and Cleveland Clinic Foundation affiliates contribute on an ongoing basis to the improvement and implementation process.

Discussion

One challenge has been advancing aspects of a nonhierarchical team approach while it is a teacher-student relationship. The dyad model is viewed as an opportunity to recognize nonhierarchical structures and teach negotiation and communication skills as well as increase interprofessional understanding of each other’s education, expertise, and scope of practice.

Another challenge is accommodating the diversity in NP training and clinical expertise. The NP student participants are in either the first or second year of their academic program. This is a challenge since both physician residents and physician faculty preceptors need to assess the NP students’ skills before providing opportunities to build on their skill level. Staff members have learned the value of checking in weekly on this issue.

Factors for Success

VA facility support and TOPC-CoEPCE leadership with the operations/academic partnership remain critical to integrating and sustaining the model into the Cleveland primary care clinic. The expertise of TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model faculty who serve as facilitators has been crucial, as they oversee team development concepts such as developing problem solving and negotiation skills. The workgroups ensured that faculty were skilled in understanding the different types of learners and provided guidance to dyad teams. Another success factor was the continual monitoring of the process and real-time evaluation of the program to adapt the model as needed.

Accomplishments and Benefits

There is evidence that the dyad model is achieving its goals: Trainees are using team skills during and outside formal dyad pairs; NP students report improvements in skill levels and comfort; and physician residents feel the teaching role in the dyad pair is an opportunity for them to improve their practice.

Interprofessional Educational Capacity

The dyad model complements the curriculum components and advances trainee understanding of 4 core domains: shared decision-making (SDM), sustained relationships (SR), interprofessional collaboration (IPC), and performance improvement (PI) (Table 2). The dyad model supports the other CoEPCE interprofessional education activities and is reinforced by these activities. The model is a learning laboratory for studying team dynamics and developing a curriculum that strengthens a team approach to patient-centered care.

Participants’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills, and Competencies

As of May 2015, 35 trainees (21 internal medicine physician residents and 14 NP students) have participated in dyads. Because physician residents participate over 2 years and may partner with more than 1 NP student, this has resulted in 27 dyad pairs in this time frame. Findings from an analysis of evaluations suggest that the dyad pair trainees learn from one another, and the model provides a safe space where trainees can practice and increase their confidence.1,6,7 The NP students seem to increase clinical skills quickly—expanding physical exam skills, building a differential diagnosis, and formulating therapeutic plans—and progressing to the Interpreter and Manager levels in the O-RIME model. The physician resident achieves the Educator level.

As of September 2015, the results from the pairs who completed beginning and end evaluations show that the physician residents increased the amount of feedback they provided about performance to the student, and likewise the student NPs also felt they received an increased amount of feedback about performance from the physician resident. In addition, physician residents reported improving the most in the following areas: allowing the student to make commitments in diagnoses and treatment plans and asking the student to provide supporting evidence for their commitment to the diagnoses. NP students reported the largest increases in receiving weekly feedback about their performance from the physician and their ability to listen to the patient.1,6,7

Interprofessional Collaboration

The TOPC-CoEPCE staff observed strengthened dyad pair relationships and mutual respect between the dyad partners. Trainees communicate with each other and work together to provide care of the patient. Second, dyad pair partners are learning about the other profession—their trajectory, their education model, and their differences. The physician resident develops an awareness of the partner NP student’s knowledge and expertise, such as their experience of social and psychological factors to become a more effective teacher, contributing to patient-centered care. The evaluation results illustrate increased ability of trainees to give and receive feedback and the change in roles for providing diagnosis and providing supporting evidence within the TOPCCoEPCE dyad team.6-8

The Future

The model has broad applicability for interprofessional education in the VA since it enhances skills that providers need to work in a PACT/PCMH model. Additionally, the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model has proven to be an effective interprofessional training experience for its affiliates and may have applicability in other VA/affiliate training programs. The dyad model can be adapted to different trainee types in the ambulatory care setting. The TOPCCoEPCE is piloting a version of the dyad with NP residents (postgraduate) and first-year medical students. Additionally, the TOPCCoEPCE is paving the way for integrating improvement of physician resident teaching skills into the primary care setting and facilitating bidirectional teaching among different professions. TOPC-CoEPCE intends to develop additional resources to facilitate use of the model application in other settings such as the dyad implementation template.

1. Billett SR. Securing intersubjectivity through interprofessional workplace learning experiences. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(3):206-211.

2. Tolsgaard MG, Bjørck S, Rasmussen MB, Gustafsson A, Ringsted C. Improving efficiency of clinical skills training: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8);1072-1077.

3. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203-1207.

4. Tham KY. Observer-Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator (O-RIME) framework to guide formative assessment of medical students. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42(11):603-607.

6. Clementz L, Dolansky MA, Lawrence RH, et al. Dyad teams: interprofessional collaboration and learning in ambulatory setting. Poster session presented: 38th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine; April 2015:Toronto, Canada. www.pcori.org/sites/default/files /SGIM-Conference-Program-2015.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2018.

7. Singh M, Clementz L, Dolansky MA, et al. MD-NP learning dyad model: an innovative approach to interprofessional teaching and learning. Workshop presented at: Annual Meeting of the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine; August 27, 2015: Cleveland, Ohio.

8. Lawrence RH, Dolansky MA, Clementz L, et al. Dyad teams: collaboration and learning in the ambulatory care setting. Poster session presented at: AAMC meeting, Innovations in Academic Medicine; November 7-11, 2014: Chicago, IL.

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). As part of VA’s New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs are using VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents and students, advanced practice nurses (APRNs), undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions trainees (such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants) for primary care practice. The CoEPCE sites are developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula to prepare learners from relevant professions to practice in patientcentered, interprofessional team-based primary care settings. Patient aligned care teams (PACTs) that have 2 or more health professions trainees engaged in learning, working, and teaching are known as interprofessional academic PACTs (iAPACTs), which is the preferred model for the VA.

The Cleveland Transforming Outpatient Care (TOPC)-CoEPCE was designed for collaborative learning among nurse practitioner (NP) students and physician residents. Its robust curriculum consists of a dedicated half-day of didactics for all learners, interprofessional quality improvement projects, panel management sessions, and primary care clinical sessions for nursing and physician learners that include the dyad workplace learning model.

In 2015, the OAA lead evaluator observed the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model process, reviewed background documents, and conducted 10 open-ended interviews with TOPC-CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, faculty, and affiliate leadership. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the TOPCCoEPC dyad model to participants, veterans, VA, and affiliates.

Lack of Interprofessional Learning Opportunities

Current health care professional education models typically do not have many workplace learning settings where physician and nursing trainees learn together and provide patient-centered care. Often in a shared clinical environment, trainees may engage in “parallel play,” which can result in physician trainees and NP students learning independently and being ill-prepared to practice effectively together.

Moreover, trainees from different professions have different learning needs. For example, less experienced NP students require greater time, supervision, and evaluation of their patient care skills. On the other hand, senior physician residents, who require less clinical instruction, need to be engaged in ways that provide opportunities to enhance their ambulatory teaching skills. Although enhancement of resident teaching skills occurs in the inpatient hospital setting, there have been limited teaching experiences for residents in a primary care setting where the instruction is traditionally faculty-based. The TOPCCoEPCE dyad model offers an opportunity to simultaneously provide trainees with a true interprofessional experience through advancement of skills in primary care, teamwork, and teaching, while addressing health care needs.

The Dyad Model

In 2011, the OAA directed COEPCE sites to develop innovative curriculum and workplace learning strategies to create more opportunities for physician and NP trainees to work as a team. There is evidence demonstrating that when students develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill set, care procedures, and values, patient care is improved.1 Further, training in pairs can be an effective strategy in education of preclerkship medical students.2 In April 2013, TOPC-CoEPCE staff asked representatives from the Student-Run Clinic at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, Ohio, to present their approach to pairing nursing and medical students in clinic under supervision by volunteer faculty. However, formal structure and curricular objectives were lacking. To address diverse TOPCCoEPCE trainee needs and create a team approach to patient care, the staff formalized and developed a workplace curriculum called the dyad model. Specifically, the model pairs 1 NP student with a senior (PGY2 or PGY3) physician resident to care for ambulatory patients as a dyad teaching/learning team. The dyad model has 3 goals: improving clinical performance, learning team dynamics, and improving the physician resident’s teaching skills in an ambulatory setting.

Planning and Implementation

Planning the dyad model took 4 months. Initial conceptualization of the model was discussed at TOPC-CoEPCE infrastructure meetings. Workgroups with representatives from medicine, nursing, evaluation and medical center administration were formed to finalize the model. The workgroups met weekly or biweekly to develop protocols for scheduling, ongoing monitoring and assessment, microteaching session curriculum development, and logistics. A pilot program was initiated for 1 month with 2 dyads to monitor learner progress and improve components, such as adjusting the patient exam start times and curriculum. In maintaining the program, the workgroups continue to meet monthly to check for areas for further improvement and maintain dissemination activities.

Curriculum

The dyad model is a novel opportunity to have trainees from different professions not only collaborate in the care of the same patient at the same time, but also negotiate their respective responsibilities preand postvisit. The experience focuses on interprofessional relationships and open communication. TOPC-CoEPCE used a modified version of the RIME (Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator) model called the O-RIME model (Table 1), which includes an observer (O) phase as the first component for clarification about a beginners’ role.3,4

Four dyad pairs provide collaborative clinical care for veterans during one halfday session per week. The dyad conducts 4 hour-long patient visits per session. To be a dyad participant, the physician residents must be at least a PGY2, and their schedule must align with the NP student clinic schedule. Participation is mandatory for both NP students and physician residents. TOPC staff assemble the pairs.

The dyad model requires knowledge of the clinical and curricular interface and when to block the dyad team members’ schedules for 4 patients instead of 6. Physician residents are in the TOPC-CoEPCE for 12 weeks and then on inpatient for 12 weeks. Depending on the nursing school affiliate, NP student trainees are scheduled for either a 6- or 12-month TOPC-CoEPCE experience. For the 12-month NP students, they are paired with up to 4 internal medicine residents over the course of their dyad participation so they can experience different teaching styles of each resident while developing more varied interprofessional communication skills.

Faculty Roles and Development

The dyad model also seeks to address the paucity of deliberate interprofessional precepting in academic primary care settings. The TOPC-CoEPCE staff decided to use the existing primary care clinic faculty development series bimonthly for 1 hour each. The dyad model team members presented sessions covering foundational material in interprofessional teaching and precepting skills, which prepare faculty to precept for different professions and the dyad teams. It is important for preceptors to develop awareness of learners from different professions and the corresponding educational trajectories, so they can communicate with paired trainees of differing professions and academic levels who may require different levels of discussion.

Resources

By utilizing advanced residents as teachers, faculty were able to increase the number of learners in the clinic without increasing the number preceptors. For example, precepting a student typically requires more preceptor time, especially when we consider that the preceptor must also see the patient. The TOPC-CoEPCE faculty run the microteaching sessions, and an evaluator monitors and evaluates the program. The microteaching sessions were derived from several teaching resources.

Monitoring and Assessment

The Cleveland TOPC administered 2 different surveys developed by the Dyad Model Infrastructure and Evaluation workgroup. A 7-item survey assesses dyad team communication and interprofessional team functioning, and an 8-item survey assesses the teaching/mentoring of the resident as teacher. Both were collected from all participants to evaluate the residents’ and students’ point of view. Surveys are collected in the first and last weeks of the dyad experience. Feedback from participants has been used to make improvements to the program (eg, monitoring how the dyad teams are functioning, coaching individual learners).

Partnerships

In addition to TOPC staff and faculty support and engagement, the initiative has benefited from partnerships with VA clinic staff and with the associated academic affiliates. In particular, the Associate Chief of General Internal Medicine at the Cleveland VA medical center and interim clinic director helped institute changes to the primary care clinic structure. Additionally, buy-in from the clinic nurse manager was needed to make adjustments with staff schedules and clinic resources. To implement the dyad model, the clinic director had to approve reductions in the residents’ clinic loads for the mornings when they participated.

The NP affiliates’ faculty at the schools of nursing are integral partners who assist with student recruitment and participate in the planning and refinement of TOPCCoEPCE components. The Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at CWRU and the Breen School of Nursing of Ursuline College in Pepper Pike, Ohio, were involved in the planning stages and continue to receive monthly updates from TOPC-CoEPCE. Similarly, the CWRU School of Medicine and Cleveland Clinic Foundation affiliates contribute on an ongoing basis to the improvement and implementation process.

Discussion

One challenge has been advancing aspects of a nonhierarchical team approach while it is a teacher-student relationship. The dyad model is viewed as an opportunity to recognize nonhierarchical structures and teach negotiation and communication skills as well as increase interprofessional understanding of each other’s education, expertise, and scope of practice.

Another challenge is accommodating the diversity in NP training and clinical expertise. The NP student participants are in either the first or second year of their academic program. This is a challenge since both physician residents and physician faculty preceptors need to assess the NP students’ skills before providing opportunities to build on their skill level. Staff members have learned the value of checking in weekly on this issue.

Factors for Success

VA facility support and TOPC-CoEPCE leadership with the operations/academic partnership remain critical to integrating and sustaining the model into the Cleveland primary care clinic. The expertise of TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model faculty who serve as facilitators has been crucial, as they oversee team development concepts such as developing problem solving and negotiation skills. The workgroups ensured that faculty were skilled in understanding the different types of learners and provided guidance to dyad teams. Another success factor was the continual monitoring of the process and real-time evaluation of the program to adapt the model as needed.

Accomplishments and Benefits

There is evidence that the dyad model is achieving its goals: Trainees are using team skills during and outside formal dyad pairs; NP students report improvements in skill levels and comfort; and physician residents feel the teaching role in the dyad pair is an opportunity for them to improve their practice.

Interprofessional Educational Capacity

The dyad model complements the curriculum components and advances trainee understanding of 4 core domains: shared decision-making (SDM), sustained relationships (SR), interprofessional collaboration (IPC), and performance improvement (PI) (Table 2). The dyad model supports the other CoEPCE interprofessional education activities and is reinforced by these activities. The model is a learning laboratory for studying team dynamics and developing a curriculum that strengthens a team approach to patient-centered care.

Participants’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills, and Competencies

As of May 2015, 35 trainees (21 internal medicine physician residents and 14 NP students) have participated in dyads. Because physician residents participate over 2 years and may partner with more than 1 NP student, this has resulted in 27 dyad pairs in this time frame. Findings from an analysis of evaluations suggest that the dyad pair trainees learn from one another, and the model provides a safe space where trainees can practice and increase their confidence.1,6,7 The NP students seem to increase clinical skills quickly—expanding physical exam skills, building a differential diagnosis, and formulating therapeutic plans—and progressing to the Interpreter and Manager levels in the O-RIME model. The physician resident achieves the Educator level.

As of September 2015, the results from the pairs who completed beginning and end evaluations show that the physician residents increased the amount of feedback they provided about performance to the student, and likewise the student NPs also felt they received an increased amount of feedback about performance from the physician resident. In addition, physician residents reported improving the most in the following areas: allowing the student to make commitments in diagnoses and treatment plans and asking the student to provide supporting evidence for their commitment to the diagnoses. NP students reported the largest increases in receiving weekly feedback about their performance from the physician and their ability to listen to the patient.1,6,7

Interprofessional Collaboration

The TOPC-CoEPCE staff observed strengthened dyad pair relationships and mutual respect between the dyad partners. Trainees communicate with each other and work together to provide care of the patient. Second, dyad pair partners are learning about the other profession—their trajectory, their education model, and their differences. The physician resident develops an awareness of the partner NP student’s knowledge and expertise, such as their experience of social and psychological factors to become a more effective teacher, contributing to patient-centered care. The evaluation results illustrate increased ability of trainees to give and receive feedback and the change in roles for providing diagnosis and providing supporting evidence within the TOPCCoEPCE dyad team.6-8

The Future

The model has broad applicability for interprofessional education in the VA since it enhances skills that providers need to work in a PACT/PCMH model. Additionally, the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model has proven to be an effective interprofessional training experience for its affiliates and may have applicability in other VA/affiliate training programs. The dyad model can be adapted to different trainee types in the ambulatory care setting. The TOPCCoEPCE is piloting a version of the dyad with NP residents (postgraduate) and first-year medical students. Additionally, the TOPCCoEPCE is paving the way for integrating improvement of physician resident teaching skills into the primary care setting and facilitating bidirectional teaching among different professions. TOPC-CoEPCE intends to develop additional resources to facilitate use of the model application in other settings such as the dyad implementation template.

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). As part of VA’s New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs are using VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents and students, advanced practice nurses (APRNs), undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions trainees (such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants) for primary care practice. The CoEPCE sites are developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula to prepare learners from relevant professions to practice in patientcentered, interprofessional team-based primary care settings. Patient aligned care teams (PACTs) that have 2 or more health professions trainees engaged in learning, working, and teaching are known as interprofessional academic PACTs (iAPACTs), which is the preferred model for the VA.

The Cleveland Transforming Outpatient Care (TOPC)-CoEPCE was designed for collaborative learning among nurse practitioner (NP) students and physician residents. Its robust curriculum consists of a dedicated half-day of didactics for all learners, interprofessional quality improvement projects, panel management sessions, and primary care clinical sessions for nursing and physician learners that include the dyad workplace learning model.

In 2015, the OAA lead evaluator observed the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model process, reviewed background documents, and conducted 10 open-ended interviews with TOPC-CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, faculty, and affiliate leadership. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the TOPCCoEPC dyad model to participants, veterans, VA, and affiliates.

Lack of Interprofessional Learning Opportunities

Current health care professional education models typically do not have many workplace learning settings where physician and nursing trainees learn together and provide patient-centered care. Often in a shared clinical environment, trainees may engage in “parallel play,” which can result in physician trainees and NP students learning independently and being ill-prepared to practice effectively together.

Moreover, trainees from different professions have different learning needs. For example, less experienced NP students require greater time, supervision, and evaluation of their patient care skills. On the other hand, senior physician residents, who require less clinical instruction, need to be engaged in ways that provide opportunities to enhance their ambulatory teaching skills. Although enhancement of resident teaching skills occurs in the inpatient hospital setting, there have been limited teaching experiences for residents in a primary care setting where the instruction is traditionally faculty-based. The TOPCCoEPCE dyad model offers an opportunity to simultaneously provide trainees with a true interprofessional experience through advancement of skills in primary care, teamwork, and teaching, while addressing health care needs.

The Dyad Model

In 2011, the OAA directed COEPCE sites to develop innovative curriculum and workplace learning strategies to create more opportunities for physician and NP trainees to work as a team. There is evidence demonstrating that when students develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill set, care procedures, and values, patient care is improved.1 Further, training in pairs can be an effective strategy in education of preclerkship medical students.2 In April 2013, TOPC-CoEPCE staff asked representatives from the Student-Run Clinic at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, Ohio, to present their approach to pairing nursing and medical students in clinic under supervision by volunteer faculty. However, formal structure and curricular objectives were lacking. To address diverse TOPCCoEPCE trainee needs and create a team approach to patient care, the staff formalized and developed a workplace curriculum called the dyad model. Specifically, the model pairs 1 NP student with a senior (PGY2 or PGY3) physician resident to care for ambulatory patients as a dyad teaching/learning team. The dyad model has 3 goals: improving clinical performance, learning team dynamics, and improving the physician resident’s teaching skills in an ambulatory setting.

Planning and Implementation

Planning the dyad model took 4 months. Initial conceptualization of the model was discussed at TOPC-CoEPCE infrastructure meetings. Workgroups with representatives from medicine, nursing, evaluation and medical center administration were formed to finalize the model. The workgroups met weekly or biweekly to develop protocols for scheduling, ongoing monitoring and assessment, microteaching session curriculum development, and logistics. A pilot program was initiated for 1 month with 2 dyads to monitor learner progress and improve components, such as adjusting the patient exam start times and curriculum. In maintaining the program, the workgroups continue to meet monthly to check for areas for further improvement and maintain dissemination activities.

Curriculum

The dyad model is a novel opportunity to have trainees from different professions not only collaborate in the care of the same patient at the same time, but also negotiate their respective responsibilities preand postvisit. The experience focuses on interprofessional relationships and open communication. TOPC-CoEPCE used a modified version of the RIME (Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator) model called the O-RIME model (Table 1), which includes an observer (O) phase as the first component for clarification about a beginners’ role.3,4

Four dyad pairs provide collaborative clinical care for veterans during one halfday session per week. The dyad conducts 4 hour-long patient visits per session. To be a dyad participant, the physician residents must be at least a PGY2, and their schedule must align with the NP student clinic schedule. Participation is mandatory for both NP students and physician residents. TOPC staff assemble the pairs.

The dyad model requires knowledge of the clinical and curricular interface and when to block the dyad team members’ schedules for 4 patients instead of 6. Physician residents are in the TOPC-CoEPCE for 12 weeks and then on inpatient for 12 weeks. Depending on the nursing school affiliate, NP student trainees are scheduled for either a 6- or 12-month TOPC-CoEPCE experience. For the 12-month NP students, they are paired with up to 4 internal medicine residents over the course of their dyad participation so they can experience different teaching styles of each resident while developing more varied interprofessional communication skills.

Faculty Roles and Development

The dyad model also seeks to address the paucity of deliberate interprofessional precepting in academic primary care settings. The TOPC-CoEPCE staff decided to use the existing primary care clinic faculty development series bimonthly for 1 hour each. The dyad model team members presented sessions covering foundational material in interprofessional teaching and precepting skills, which prepare faculty to precept for different professions and the dyad teams. It is important for preceptors to develop awareness of learners from different professions and the corresponding educational trajectories, so they can communicate with paired trainees of differing professions and academic levels who may require different levels of discussion.

Resources

By utilizing advanced residents as teachers, faculty were able to increase the number of learners in the clinic without increasing the number preceptors. For example, precepting a student typically requires more preceptor time, especially when we consider that the preceptor must also see the patient. The TOPC-CoEPCE faculty run the microteaching sessions, and an evaluator monitors and evaluates the program. The microteaching sessions were derived from several teaching resources.

Monitoring and Assessment

The Cleveland TOPC administered 2 different surveys developed by the Dyad Model Infrastructure and Evaluation workgroup. A 7-item survey assesses dyad team communication and interprofessional team functioning, and an 8-item survey assesses the teaching/mentoring of the resident as teacher. Both were collected from all participants to evaluate the residents’ and students’ point of view. Surveys are collected in the first and last weeks of the dyad experience. Feedback from participants has been used to make improvements to the program (eg, monitoring how the dyad teams are functioning, coaching individual learners).

Partnerships

In addition to TOPC staff and faculty support and engagement, the initiative has benefited from partnerships with VA clinic staff and with the associated academic affiliates. In particular, the Associate Chief of General Internal Medicine at the Cleveland VA medical center and interim clinic director helped institute changes to the primary care clinic structure. Additionally, buy-in from the clinic nurse manager was needed to make adjustments with staff schedules and clinic resources. To implement the dyad model, the clinic director had to approve reductions in the residents’ clinic loads for the mornings when they participated.

The NP affiliates’ faculty at the schools of nursing are integral partners who assist with student recruitment and participate in the planning and refinement of TOPCCoEPCE components. The Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at CWRU and the Breen School of Nursing of Ursuline College in Pepper Pike, Ohio, were involved in the planning stages and continue to receive monthly updates from TOPC-CoEPCE. Similarly, the CWRU School of Medicine and Cleveland Clinic Foundation affiliates contribute on an ongoing basis to the improvement and implementation process.

Discussion

One challenge has been advancing aspects of a nonhierarchical team approach while it is a teacher-student relationship. The dyad model is viewed as an opportunity to recognize nonhierarchical structures and teach negotiation and communication skills as well as increase interprofessional understanding of each other’s education, expertise, and scope of practice.

Another challenge is accommodating the diversity in NP training and clinical expertise. The NP student participants are in either the first or second year of their academic program. This is a challenge since both physician residents and physician faculty preceptors need to assess the NP students’ skills before providing opportunities to build on their skill level. Staff members have learned the value of checking in weekly on this issue.

Factors for Success

VA facility support and TOPC-CoEPCE leadership with the operations/academic partnership remain critical to integrating and sustaining the model into the Cleveland primary care clinic. The expertise of TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model faculty who serve as facilitators has been crucial, as they oversee team development concepts such as developing problem solving and negotiation skills. The workgroups ensured that faculty were skilled in understanding the different types of learners and provided guidance to dyad teams. Another success factor was the continual monitoring of the process and real-time evaluation of the program to adapt the model as needed.

Accomplishments and Benefits

There is evidence that the dyad model is achieving its goals: Trainees are using team skills during and outside formal dyad pairs; NP students report improvements in skill levels and comfort; and physician residents feel the teaching role in the dyad pair is an opportunity for them to improve their practice.

Interprofessional Educational Capacity

The dyad model complements the curriculum components and advances trainee understanding of 4 core domains: shared decision-making (SDM), sustained relationships (SR), interprofessional collaboration (IPC), and performance improvement (PI) (Table 2). The dyad model supports the other CoEPCE interprofessional education activities and is reinforced by these activities. The model is a learning laboratory for studying team dynamics and developing a curriculum that strengthens a team approach to patient-centered care.

Participants’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills, and Competencies

As of May 2015, 35 trainees (21 internal medicine physician residents and 14 NP students) have participated in dyads. Because physician residents participate over 2 years and may partner with more than 1 NP student, this has resulted in 27 dyad pairs in this time frame. Findings from an analysis of evaluations suggest that the dyad pair trainees learn from one another, and the model provides a safe space where trainees can practice and increase their confidence.1,6,7 The NP students seem to increase clinical skills quickly—expanding physical exam skills, building a differential diagnosis, and formulating therapeutic plans—and progressing to the Interpreter and Manager levels in the O-RIME model. The physician resident achieves the Educator level.

As of September 2015, the results from the pairs who completed beginning and end evaluations show that the physician residents increased the amount of feedback they provided about performance to the student, and likewise the student NPs also felt they received an increased amount of feedback about performance from the physician resident. In addition, physician residents reported improving the most in the following areas: allowing the student to make commitments in diagnoses and treatment plans and asking the student to provide supporting evidence for their commitment to the diagnoses. NP students reported the largest increases in receiving weekly feedback about their performance from the physician and their ability to listen to the patient.1,6,7

Interprofessional Collaboration

The TOPC-CoEPCE staff observed strengthened dyad pair relationships and mutual respect between the dyad partners. Trainees communicate with each other and work together to provide care of the patient. Second, dyad pair partners are learning about the other profession—their trajectory, their education model, and their differences. The physician resident develops an awareness of the partner NP student’s knowledge and expertise, such as their experience of social and psychological factors to become a more effective teacher, contributing to patient-centered care. The evaluation results illustrate increased ability of trainees to give and receive feedback and the change in roles for providing diagnosis and providing supporting evidence within the TOPCCoEPCE dyad team.6-8

The Future

The model has broad applicability for interprofessional education in the VA since it enhances skills that providers need to work in a PACT/PCMH model. Additionally, the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model has proven to be an effective interprofessional training experience for its affiliates and may have applicability in other VA/affiliate training programs. The dyad model can be adapted to different trainee types in the ambulatory care setting. The TOPCCoEPCE is piloting a version of the dyad with NP residents (postgraduate) and first-year medical students. Additionally, the TOPCCoEPCE is paving the way for integrating improvement of physician resident teaching skills into the primary care setting and facilitating bidirectional teaching among different professions. TOPC-CoEPCE intends to develop additional resources to facilitate use of the model application in other settings such as the dyad implementation template.

1. Billett SR. Securing intersubjectivity through interprofessional workplace learning experiences. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(3):206-211.

2. Tolsgaard MG, Bjørck S, Rasmussen MB, Gustafsson A, Ringsted C. Improving efficiency of clinical skills training: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8);1072-1077.

3. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203-1207.

4. Tham KY. Observer-Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator (O-RIME) framework to guide formative assessment of medical students. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42(11):603-607.

6. Clementz L, Dolansky MA, Lawrence RH, et al. Dyad teams: interprofessional collaboration and learning in ambulatory setting. Poster session presented: 38th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine; April 2015:Toronto, Canada. www.pcori.org/sites/default/files /SGIM-Conference-Program-2015.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2018.

7. Singh M, Clementz L, Dolansky MA, et al. MD-NP learning dyad model: an innovative approach to interprofessional teaching and learning. Workshop presented at: Annual Meeting of the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine; August 27, 2015: Cleveland, Ohio.

8. Lawrence RH, Dolansky MA, Clementz L, et al. Dyad teams: collaboration and learning in the ambulatory care setting. Poster session presented at: AAMC meeting, Innovations in Academic Medicine; November 7-11, 2014: Chicago, IL.

1. Billett SR. Securing intersubjectivity through interprofessional workplace learning experiences. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(3):206-211.

2. Tolsgaard MG, Bjørck S, Rasmussen MB, Gustafsson A, Ringsted C. Improving efficiency of clinical skills training: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8);1072-1077.

3. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203-1207.

4. Tham KY. Observer-Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator (O-RIME) framework to guide formative assessment of medical students. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42(11):603-607.

6. Clementz L, Dolansky MA, Lawrence RH, et al. Dyad teams: interprofessional collaboration and learning in ambulatory setting. Poster session presented: 38th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine; April 2015:Toronto, Canada. www.pcori.org/sites/default/files /SGIM-Conference-Program-2015.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2018.

7. Singh M, Clementz L, Dolansky MA, et al. MD-NP learning dyad model: an innovative approach to interprofessional teaching and learning. Workshop presented at: Annual Meeting of the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine; August 27, 2015: Cleveland, Ohio.

8. Lawrence RH, Dolansky MA, Clementz L, et al. Dyad teams: collaboration and learning in the ambulatory care setting. Poster session presented at: AAMC meeting, Innovations in Academic Medicine; November 7-11, 2014: Chicago, IL.

Population Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an umbrella term that covers a spectrum of phenotypes ranging from nonalcoholic fatty liver or simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) defined by histologic findings of steatosis, lobular inflammation, cytologic ballooning, and some degree of fibrosis.1 While frequently observed in patients with at least 1 risk factor (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus [DM], dyslipidemia, hypertension), NAFLD also is an independent risk factor for type 2 DM (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease.2 At early disease stages with absence of liver fibrosis, mortality is linked to cardiovascular and not liver disease. However, in the presence of NASH, fibrosis progression to liver cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represent the most important liver-related outcomes that determine morbidity and mortality.3 Mirroring the obesity and T2DM epidemics, the health care burden is projected to dramatically rise.

In the following article, we will discuss how the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is well positioned to implement an organizational strategy of comprehensive care for veterans with NAFLD. This comprehensive care strategy should include the development of a NAFLD clinic offering care for comorbid conditions frequently present in these patients, point-of-care testing, access to clinical trials, and outcomes monitoring as a key performance target for providers and the respective facility.

NAFLD disease burden

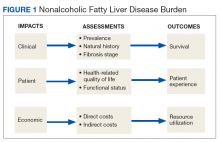

To fully appreciate the burden of a chronic disease like NAFLD, it is important to assess its long- and short-term consequences in a comprehensive manner with regard to its clinical impact, impact on the patient, and economic impact (Figure 1).

Clinical Impact

Clinical impact is assessed based on the prevalence and natural history of NAFLD and the liver fibrosis stage and determines patient survival. Coinciding with the epidemic of obesity and T2DM, the prevalence of NAFLD in the general population in North America is 24% and even higher with older age and higher body mass index (BMI).4,5 The prevalence for NAFLD is particularly high in patients with T2DM (47%). Of patients with T2DM and NAFLD, 65% have biopsy-proven NASH of which 15% have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis.6

NAFLD is the fastest growing cause of cirrhosis in the US with a forecasted NAFLD population of 101 million by 2030.7 At the same time, the number of patients with NASH will rise to 27 million of which > 7 million will have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis; hepatic decompensation events are estimated to occur in 105,430 patients with liver cirrhosis, posing a major public health threat related to organ availability for liver transplantation.8 Since 2013, NAFLD has been the second leading cause for liver transplantation and the top reason for transplantation in patients aged < 50 years.9,10 As many patients with NAFLD are diagnosed with HCC at stages where liver transplantation is not an option, mortality from HCC in NAFLD patients is higher than with other etiologies as treatment options are restricted.11,12

Compared with that of the general population, veterans seeking care are older and sicker with 43% of veterans taking > 5 prescribed medications.13 Of those receiving VHA care, 6.6 million veterans are either overweight or obese; 165,000 are morbidly obese with a BMI > 40.14 In addition, veterans are 2.5 times more likely to have T2DM compared with that of nonveterans. Because T2DM and obesity are the most common risk factors for NAFLD, it is not surprising that NAFLD prevalence among veterans rose 3-fold from 2003 to 2011.15 It is now estimated that 540,000 veterans will progress to NASH and 108,000 will develop bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis by 2030.8 Similar to that of the general population, liver cirrhosis is attributed to NAFLD in 15% of veterans.15,16 NAFLD is the third most common cause of cirrhosis and HCC, occurring at an average age of 66 years and 70 years, respectively.16,17 Shockingly, 20% of HCCs were not linked to liver cirrhosis and escaped recommended HCC screening for patients with cirrhosis.18,19

Patient Impact

Assessment of disease burden should not be restricted to clinical outcomes as patients can experience a range of symptoms that may have significant impact on their health-related quality of life (QOL) and functional status.20 Using general but not disease-specific instruments, NAFLD patients reported outcomes score low regarding fatigue, activity, and emotions.21 More disease-specific questionnaires may provide better and disease-specific insights as how NASH impacts patients’ QOL.22-24

Economic Impact

There is mounting evidence that the clinical implications of NAFLD directly influence the economic burden of NAFLD.25 The annual burden associated with all incident and prevalent NAFLD cases in the US has been estimated at $103 billion, and projections suggest that the expected 10-year burden of NAFLD may increase to $1.005 trillion.26 It is anticipated that increased NAFLD costs will affect the VHA with billions of dollars in annual expenditures in addition to the $1.5 billion already spent annually for T2DM care (4% of the VA pharmacy budget is spent on T2DM treatment).27-29

Current Patient Care

Obesity, DM, and dyslipidemia are common conditions managed by primary care providers (PCPs). Given the close association of these conditions with NAFLD, the PCP is often the first point of medical contact for patients with or at risk for NAFLD.30 For that reason, PCP awareness of NAFLD is critical for effective management of these patients. PCPs should be actively involved in the management of patients with NAFLD with pathways in place for identifying patients at high risk of liver disease for timely referral to a specialist and adequate education on the follow-up and treatment of low-risk patients. Instead, diagnosis of NAFLD is primarily triggered by either abnormal aminotransferases or detection of steatosis on imaging performed for other indications.

Barriers to optimal management of NAFLD by PCPs have been identified and occur at different levels of patient care. In the absence of clinical practice guidelines by the American Association of Family Practice covering NAFLD and a substantial latency period without signs of symptoms, NAFLD may not be perceived as a potentially serious condition by PCPs and their patients; interestingly this holds true even for some medical specialties.31-39 More than half of PCPs do not test their patients at highest risk for NAFLD (eg, patients with obesity or T2DM) and may be unaware of practice guidelines.40-42

Guidelines from Europe and the US are not completely in accordance. The US guidelines are vague regarding screening and are supported by only 1 medical society, due to the lack of NASH-specific drug therapies. The European guidelines are built on the support of 3 different stakeholders covering liver diseases, obesity, and DM and the experience using noninvasive liver fibrosis assessments for patients with NAFLD. To overcome this apparent conflict, a more practical and risk-stratified approach is warranted.41,42

Making the diagnosis can be challenging in cases with competing etiologies, such as T2DM and alcohol misuse. There also is an overreliance on aminotransferase levels to diagnose NAFLD. Significant liver disease can exist in the presence of normal aminotransferases, and this may be attributed to either spontaneous aminotransferase fluctuations or upper limits of normal that have been chosen too high.43-47 Often additional workup by PCPs depends on the magnitude of aminotransferase abnormalities.

Even if NAFLD has been diagnosed by PCPs, identifying those with NASH is hindered by the absence of an accurate noninvasive diagnostic method and the need to perform a liver biopsy. Liver biopsy is often not considered or delayed to monitor patients with serial aminotransferases, regardless of the patient’s metabolic comorbidity profile or baseline aminotransferases.32 As a result, referral to a specialist often depends on the magnitude of the aminotransferase abnormality,30,48 and often occurs when advanced liver disease is already present.49 Finally, providers may not be aware of beneficial effects of lifestyle interventions and certain medications, including statins on NASH and liver fibrosis.50-53 As NAFLD is associated with excess cardiovascular- and cancer-related morbidity and mortality, it is possible that regression of NAFLD may improve associated risk for these outcomes as well.

Framework for Comprehensive NAFLD Care

Chronic liver diseases and associated comorbidities have long been addressed by PCPs and specialty providers working in isolation and within the narrow focus of each discipline. Contrary to working in silos of the past, a coordinated management strategy with other disciplines that cover these comorbidities needs to be established, or alternatively the PCP must be aware of the management of comorbidities to execute them independently. Integration of hepatology-driven NAFLD care with other specialties involves communication, collaboration, and sharing of resources and expertise that will address patient care needs. Obviously, this cannot be undertaken in a single outpatient visit and requires vertical and longitudinal follow-up over time. One important aspect of comprehensive NAFLD care is the targeting of a particular patient population rather than being seen as a panacea for all; cost-utility analysis is hampered by uncertainties around accuracy of noninvasive biomarkers reflecting liver injury and a lack of effectiveness data for treatment. However, it seems reasonable to screen patients at high risk for NASH and adverse clinical outcomes. Such a risk stratification approach should be cost-effective.

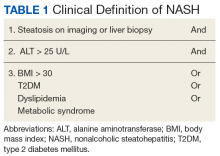

A first key step by the PCP is to identify whether a patient is at risk, especially patients with NASH. The majority of patients at risk are already seen by PCPs. While there is no consensus on ideal screening for NAFLD by PCPs, the use of ultrasound in the at-risk population is recommended in Europe.42 Although NASH remains a histopathologic diagnosis, a reasonable approach is to define NASH based on clinical criteria as done similarly in a real-world observational NAFLD cohort study.54 In the absence of chronic alcohol consumption and viral hepatitis and in a real-world scenario, NASH can be defined as steatosis shown on liver imaging or biopsy and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of > 25 U/L. In addition, ≥ 1 of the following criteria must be met: BMI > 30, T2DM, dyslipidemia, or metabolic syndrome (Table 1).

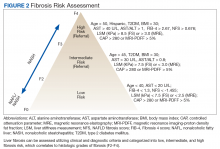

In the absence of easy-to-use validated tests, all patients with NAFLD need to be assessed with simple, noninvasive scores for the presence of clinically relevant liver fibrosis (F2-portal fibrosis with septa; F3-bridging fibrosis; F4-liver cirrhosis); those that meet the fibrosis criteria should receive further assessment usually only offered in a comprehensive NAFLD clinic.1 PCPs should focus on addressing 2 aspects related to NAFLD: (1) Does my patient have NASH based on clinical criteria; and (2) Is my patient at risk for clinically relevant liver fibrosis? PCPs are integral in optimal management of comorbidities and metabolic syndrome abnormalities with lifestyle and exercise interventions.

The care needs of a typical patient with NAFLD can be classified into 3 categories: liver disease (NAFLD) management, addressing NAFLD associated comorbidities, and attending to the personal care needs of the patient. With considerable interactions between these categories, interventions done within the framework of 1 category can influence the needs pertaining to another, requiring closer monitoring of the patient and potentially modifying care. For example, initiating a low carbohydrate diet in a patient with DM and NAFLD who is on antidiabetic medication may require adjusting the medication; disease progression or failure to achieve treatment goals may affect the emotional state of the patient, which can affect adherence.

Referrals to a comprehensive NAFLD clinic need to be standardized. Clearly, the referral process depends in part on local resources, comprehensiveness of available services, and patient characteristics, among others. Most often, PCPs refer patients with suspected diagnosis of NAFLD, with or without abnormal aminotransferases, to a hepatologist to confirm the diagnosis and for disease staging and liver disease management. This may have the advantage of greatest extent of access and should limit the number of patients with advanced liver fibrosis who otherwise may have been missed. On the other hand, different thresholds of PCPs for referrals may delay the patient’s access to comprehensive NAFLD care. Of those referred by primary care, the hepatologist identifies patients with NAFLD who benefit most from a comprehensive care approach. This automated referral process without predefined criteria remains more a vision than reality as it would require an infrastructure and resources that no health care system can provide currently.

The alternative approach of automatic referral may use predefined criteria related to patients’ diagnoses and prognoses (Figure 2).

Patient-Centered Care

At present the narrow focus of VHA specialty outpatient clinics associated with time constraints of providers and gaps in NAFLD awareness clearly does not address the complex metabolic needs of veterans with NAFLD. This is in striking contrast to the comprehensive care offered to patients with cancer. To overcome these limitations, new care delivery models need to be explored. At first it seems attractive to embed NAFLD patient care geographically into a hepatology clinic with the potential advantages of improving volume and timeliness of referral and reinforcing communication among specialty providers while maximizing convenience for patients. However, this is resource intensive not only concerning clinic space, but also in terms of staffing clinics with specialty providers.

Patient-centered care for veterans with NAFLD seems to be best organized around a comprehensive NAFLD clinic with access to specialized diagnostics and knowledge in day-to-day NAFLD management. This evolving care concept has been developed already for patients with liver cirrhosis and inflammatory bowel disease and considers NAFLD a chronic disease that cannot be addressed sufficiently by providing episodic care.55,56 The development of comprehensive NAFLD care can build on the great success of the Hepatitis Innovation Team Collaborative that employed lean management strategies with local and regional teams to facilitate efforts to make chronic hepatitis C virus a rare disease in the VHA.57

NAFLD Care Team

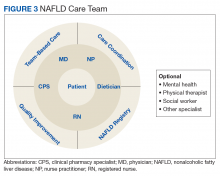

Given the central role of the liver and gastrointestinal tract in the field of nutrition, knowledge of the pathophysiology of the liver and digestive tract as well as emerging therapeutic options offered via metabolic endoscopy uniquely positions the hepatologist/gastroenterologist to take the lead in managing NAFLD. Treating NAFLD is best accomplished when the specialist partners with other health care providers who have expertise in the nutritional, behavioral, and physical activity aspects of treatment. The composition of the NAFLD care team and the roles that different providers fulfill can vary depending on the clinical setting; however, the hepatologist/gastroenterologist is best suited to lead the team, or alternatively, this role can be fulfilled by a provider with liver disease expertise.

Based on experiences from the United Kingdom, the minimum staffing of a NAFLD clinic should include a physician and nurse practitioner who has expertise in managing patients with chronic liver disease, a registered nurse, a dietitian, and a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS).58 With coexistent diseases common and many veterans who have > 5 prescribed medications, risk of polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions are a concern, particularly since adherence in patients with chronic diseases has been reported to be as low as 43%.59-61 Risk of medication errors and serious adverse effects are magnified by difficulties with patient adherence, medication interactions, and potential need for frequent dose adjustments, particularly when on a weight-loss diet.

Without doubt, comprehensive medication management, offered by a highly trained CPS with independent prescriptive authority occurring while the veteran is in the NAFLD clinic, is highly desirable. Establishing a functional statement and care coordination agreement could describe the role of the CPS as a member of the NAFLD provider team.

Patient Evaluation

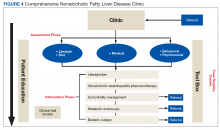

After being referred to the NAFLD clinic, the veteran should have a thorough assessment, including medical, nutritional, physical activity, exercise, and psychosocial evaluations (Figure 4).

The assessment also should include patient education to ensure that the patient has sufficient knowledge and skills to achieve the treatment goals. Educating on NAFLD is critical as most patients with NAFLD do not think of themselves as sick and have limited readiness for lifestyle changes.63,64 A better understanding of NAFLD combined with a higher self-efficacy seems to be positively linked to better nutritional habits.65

An online patient-reported outcomes measurement information system for a patient with NAFLD (eg, assessmentcenter.net) may be beneficial and can be applied within a routine NAFLD clinic visit because of its multidimensionality and compatibility with other chronic diseases.66-68 Other tools to assess health-related QOL include questionnaires, such as the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue, work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire: specific health problem, Short Form-36, and chronic liver disease questionnaire-NAFLD.23,69

The medical evaluation includes assessment of secondary causes of NAFLD and identification of NAFLD-related comorbidities. Weight, height, blood pressure, waist circumference, and BMI should be recorded. The physical exam should focus on signs of chronic liver disease and include inspection for acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, and large neck circumference, which are associated with insulin resistance, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea, respectively. NAFLD-associated comorbidities may contribute to frailty or physical limitations that affect treatment with diet and exercise and need to be assessed. A thorough medication reconciliation will reveal whether the patient is prescribed obesogenic medications and whether comorbidities (eg, DM and dyslipidemia) are being treated optimally and according to current society guidelines.

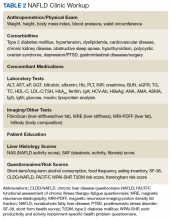

Making the diagnosis of NAFLD requires excluding other (concomitant) chronic liver diseases. While often this is done indirectly using order sets with a panoply of available serologic tests without accounting for risks for rare causes of liver injury, a more focused and cost-effective approach is warranted. As most patients will already have had imaging studies that show fatty liver, assessment of liver fibrosis is an important step for risk stratification. Noninvasive scores (eg, FIB-4) can be used by the PCP to identify high-risk patients requiring further workup and referral.1,70 More sophisticated tools, including transient elastography and/or magnetic resonance elastography are applied for more sophisticated risk stratification and liver disease management (Table 2).71

A nutritional evaluation includes information about eating behavior and food choices, body composition analysis, and an assessment of short- and long-term alcohol consumption. Presence of bilateral muscle wasting, subcutaneous fat loss, and signs of micronutrient deficiencies also should be explored. The lifestyle evaluation should include the patient’s typical physical activity and exercise as well as limiting factors.

Finally, and equally important, the patient’s psychosocial situation should be assessed, as motivation and accountability are key to success and may require behavioral modification. Assessing readiness is done best with motivational interviewing, the 5As counseling framework (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) or using open-ended questions, affirmation, reflections, and summaries.72,73 Even if not personally delivering behavioral treatment, such an approach also can help move patients toward addressing important health-related behaviors.

Personalized Interventions

If available, patients should be offered participation in NAFLD clinical trials. A personalized treatment plan should be developed for each patient with input from all NAFLD care team members. The patient and providers should work together to make important decisions about the treatment plan and goals of care. Making the patient an active participant in their treatment rather than the passive recipient will lead to improvement in adherence and outcomes. Patients will engage when they are comfortable speaking with providers and are sufficiently educated about their disease.

Personalized interventions may be built by combining different strategies, such as lifestyle and dietary interventions, NASH-specific pharmacotherapy, comorbidity management, metabolic endoscopy, and bariatric surgery. Although NASH-specific medications are not currently available, approved medications, including pioglitazone or liraglutide, can be considered for therapy.74,75 Ideally, the NAFLD team CPS would manage comorbidities, such as T2DM and dyslipidemia, but this also can be done by a hepatologist or other specialist. Metabolic endoscopy (eg, intragastric balloons) or bariatric surgery would be done by referral.

Resource-Limited Settings

Although the VHA offers care at > 150 medical centers and > 1,000 outpatient clinics, specialty care such as hepatology and sophisticated and novel testing modalities are not available at many facilities. In 2011 VHA launched the Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes to bring hepatitis C therapy and liver transplantation evaluations to rural areas without specialists.76-78 It is logical to explore how telehealth can be used for NAFLD care that requires complex management using new treatments and has a high societal impact, particularly when left untreated.

Telehealth must be easy to use and integrated into everyday routines to be useful for NAFLD management by addressing different aspects of promoting self-management, optimizing therapy, and care coordination. Participation in a structured face-to-face or group-based lifestyle program is often jeopardized by time and job constraints but can be successfully overcome using online approaches.79 The Internet-based VA Video Connect videoconferencing, which incorporates cell phone, laptop, or tablet use could help expand lifestyle interventions to a much larger community of patients with NAFLD and overcome local resource constraints. Finally, e-consultation also can be used in circumstances where synchronous communication with specialists may not be necessary.

Patient Monitoring and Quality Metrics

Monitoring of the patient after initiation of an intervention is variable but occurs more frequently at the beginning. For high-intensity dietary interventions, weekly monitoring for the first several weeks can ensure ongoing motivation, and accountability may increase the patient’s confidence and provide encouragement for further weight loss. It also is an opportunity to reestablish goals with patients with declining motivation. Long-term monitoring of patients may occur in 6- to 12-month intervals to document patient-reported outcomes, liver-related mortality, cardiovascular events, malignancies, and disease progression or regression.

While quality indicators have been proposed for cirrhosis care, such indicators have yet to be defined for NALD care.80 Such quality indicators assessed with validated questionnaires should include knowledge about NAFLD, satisfaction with care, perception of quality of care, and patient-reported outcomes. Other indicators may include use of therapies to treat dyslipidemia and T2DM. Last and likely the most important indicator of improved liver health in NAFLD will be either histologic improvement of NASH or improvement of the fibrosis risk category.

Outlook

With the enormous burden of NAFLD on the rise for many more years to come, quality care delivered to patients with NAFLD warrants resource-adaptive population health management strategies. With a limited number of providers specialized in liver disease, provider education assisted by clinical guidelines and decision support tools, development of referral and access to care mechanisms through integrated care, remote monitoring strategies as well as development of patient self-management and community resources will become more important. We have outlined essential components of an effective population health management strategy for NAFLD and actionable items for the VHA to consider when implementing these strategies. This is the time for the VHA to invest in efforts for NAFLD population care. Clearly, consideration must be given to local needs and resources and integration of technology platforms. Addressing NAFLD at a population level will provide yet another opportunity to demonstrate that VHA performs better on quality when compared with care systems in the private sector.81

1. Hunt CM, Turner MJ, Gifford EJ, Britt RB, Su GL. Identifying and treating nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Fed Pract. 2019;36(1):20-29.

2. Glass LM, Hunt CM, Fuchs M, Su GL. Comorbidities and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the chicken, the egg, or both? Fed Pract. 2019;36(2):64-71.

3. Vilar-Gomez E, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Wai-Sun Wong V, et al. Fibrosis severity as a determinant of cause-specific mortality in patients with advanced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a multi-national cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):443-457.e17.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73-84.

5. Yki-Järvinen H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(11):901-910.