User login

ESMO offers new clinical practice guideline for CLL

An updated European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines were released to provide key recommendations on the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The guidelines were developed by a multidisciplinary group of experts from different institutions and countries in Europe and provide levels of evidence and grades of recommendation where applicable for issues regarding prognosis and treatment decisions in CLL. Such decisions depend on genetic and clinical factors such as age, stage, and comorbidities. The guidelines also focus on new therapies targeting B-cell-receptor pathways or defect mechanism of apoptosis, which have been found to induce long-lasting remissions. The guidelines were endorsed by the European Hematology Association (EHA) through the Scientific Working Group on CLL/European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC), according to the report published online the Annals of Oncology.

These clinical practice guidelines were developed in accordance with the ESMO standard operating procedures for clinical practice guidelines development with use of relevant literature selected by the expert authors. Statements without grading were considered justified as standard clinical practice by the experts and the ESMO faculty.

Below are some highlights of the guidelines, which cover a wide array of topics regarding the diagnosis, staging, treatment, and progression of CLL disease.

Diagnosis

The guidelines indicate that CLL diagnosis is usually possible by immunophenotyping of peripheral blood only and that lymph node (LN) biopsy and/or bone marrow biopsy may be helpful if immunophenotyping is not conclusive for the diagnosis of CLL, according to Barbara Eichhorst, MD, of the University of Cologne (Germany) and colleagues on behalf of the ESMO guidelines committee.

Staging and risk assessment

Early asymptomatic-stage disease does not need further risk assessment, but after the first year, when all patients should be seen at 3-monthly intervals, patients can be followed every 3-12 months. The interval would depend on burden and dynamics of the disease obtained by the using history and physical examinations, including a careful palpation of all LN areas, spleen, and liver, as well as assessing complete blood cell count and differential count, according to the report.

Advanced- and symptomatic-stage disease requires a broader examination including imaging, history and status of relevant infections, and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) assays for the detection of deletion of the chromosome 17 (del[17p]) affecting the tumor protein p53 expression and, in the absence of del(17p), TP53 sequencing for detection of TP53 gene mutation, according to the authors.

Prognostication

Two clinical staging systems are typically used in CLL. Both Binet and Rai staging systems separate three groups of patients with different prognosis, although “as a consequence of more effective therapy, the overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced stage has improved and the relevance of the staging systems for prognostication has decreased,” according to the report.

The recent addition of genetic markers has also proved highly relevant to identifying patients with different prognoses and to guide treatment.

Therapy

Although CLL is an incurable disease, choice and application of treatment are strongly tied to the length of survival, according to the authors. The guidelines recommend Binet and Rai staging with clinical symptoms as relevant for treatment indication. In addition, the identification of del(17p), TP53 mutations, and IGHV status are relevant for choice of therapy and should be assessed prior to treatment.

The guidelines discuss specific treatment modalities for various stages of the disease, from early stages to relapse.

For frontline therapy, different treatment strategies are available including continuous treatment with Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK)–inhibitors, such as ibrutinib, until progression or time-limited therapy with ChT backbone and CD20 antibodies. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency have recently approved the combination of venetoclax plus obinutuzumab for first-line therapy of CLL.

Treatment decisions should include an assessment of IGHV and TP53 status, as well as patient-related factors such as comedication, comorbidities, preferences, drug availability, and potential of treatment adherence, according to the guidelines.

In case of symptomatic relapse within 3 years after fixed-duration therapy or nonresponse to therapy, the guidelines recommend that the therapeutic regimen should be changed, regardless of the type of first-line either to venetoclax plus rituximab for 24 months or to ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or other BTK inhibitors (if available) as continuous therapy.

The guidelines also discuss the possible roles for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies, as well as the treatment of the various complications that can arise in patients with CLL, and dealing with various aspects of disease progression.

No external funds were provided for the production of the guidelines. The authors of the report and members of the ESMO Guidelines Committee reported numerous disclosures regarding pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Eichhorst B et al. Ann Oncol. 2020 Oct 19. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.019.

An updated European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines were released to provide key recommendations on the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The guidelines were developed by a multidisciplinary group of experts from different institutions and countries in Europe and provide levels of evidence and grades of recommendation where applicable for issues regarding prognosis and treatment decisions in CLL. Such decisions depend on genetic and clinical factors such as age, stage, and comorbidities. The guidelines also focus on new therapies targeting B-cell-receptor pathways or defect mechanism of apoptosis, which have been found to induce long-lasting remissions. The guidelines were endorsed by the European Hematology Association (EHA) through the Scientific Working Group on CLL/European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC), according to the report published online the Annals of Oncology.

These clinical practice guidelines were developed in accordance with the ESMO standard operating procedures for clinical practice guidelines development with use of relevant literature selected by the expert authors. Statements without grading were considered justified as standard clinical practice by the experts and the ESMO faculty.

Below are some highlights of the guidelines, which cover a wide array of topics regarding the diagnosis, staging, treatment, and progression of CLL disease.

Diagnosis

The guidelines indicate that CLL diagnosis is usually possible by immunophenotyping of peripheral blood only and that lymph node (LN) biopsy and/or bone marrow biopsy may be helpful if immunophenotyping is not conclusive for the diagnosis of CLL, according to Barbara Eichhorst, MD, of the University of Cologne (Germany) and colleagues on behalf of the ESMO guidelines committee.

Staging and risk assessment

Early asymptomatic-stage disease does not need further risk assessment, but after the first year, when all patients should be seen at 3-monthly intervals, patients can be followed every 3-12 months. The interval would depend on burden and dynamics of the disease obtained by the using history and physical examinations, including a careful palpation of all LN areas, spleen, and liver, as well as assessing complete blood cell count and differential count, according to the report.

Advanced- and symptomatic-stage disease requires a broader examination including imaging, history and status of relevant infections, and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) assays for the detection of deletion of the chromosome 17 (del[17p]) affecting the tumor protein p53 expression and, in the absence of del(17p), TP53 sequencing for detection of TP53 gene mutation, according to the authors.

Prognostication

Two clinical staging systems are typically used in CLL. Both Binet and Rai staging systems separate three groups of patients with different prognosis, although “as a consequence of more effective therapy, the overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced stage has improved and the relevance of the staging systems for prognostication has decreased,” according to the report.

The recent addition of genetic markers has also proved highly relevant to identifying patients with different prognoses and to guide treatment.

Therapy

Although CLL is an incurable disease, choice and application of treatment are strongly tied to the length of survival, according to the authors. The guidelines recommend Binet and Rai staging with clinical symptoms as relevant for treatment indication. In addition, the identification of del(17p), TP53 mutations, and IGHV status are relevant for choice of therapy and should be assessed prior to treatment.

The guidelines discuss specific treatment modalities for various stages of the disease, from early stages to relapse.

For frontline therapy, different treatment strategies are available including continuous treatment with Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK)–inhibitors, such as ibrutinib, until progression or time-limited therapy with ChT backbone and CD20 antibodies. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency have recently approved the combination of venetoclax plus obinutuzumab for first-line therapy of CLL.

Treatment decisions should include an assessment of IGHV and TP53 status, as well as patient-related factors such as comedication, comorbidities, preferences, drug availability, and potential of treatment adherence, according to the guidelines.

In case of symptomatic relapse within 3 years after fixed-duration therapy or nonresponse to therapy, the guidelines recommend that the therapeutic regimen should be changed, regardless of the type of first-line either to venetoclax plus rituximab for 24 months or to ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or other BTK inhibitors (if available) as continuous therapy.

The guidelines also discuss the possible roles for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies, as well as the treatment of the various complications that can arise in patients with CLL, and dealing with various aspects of disease progression.

No external funds were provided for the production of the guidelines. The authors of the report and members of the ESMO Guidelines Committee reported numerous disclosures regarding pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Eichhorst B et al. Ann Oncol. 2020 Oct 19. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.019.

An updated European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines were released to provide key recommendations on the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The guidelines were developed by a multidisciplinary group of experts from different institutions and countries in Europe and provide levels of evidence and grades of recommendation where applicable for issues regarding prognosis and treatment decisions in CLL. Such decisions depend on genetic and clinical factors such as age, stage, and comorbidities. The guidelines also focus on new therapies targeting B-cell-receptor pathways or defect mechanism of apoptosis, which have been found to induce long-lasting remissions. The guidelines were endorsed by the European Hematology Association (EHA) through the Scientific Working Group on CLL/European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC), according to the report published online the Annals of Oncology.

These clinical practice guidelines were developed in accordance with the ESMO standard operating procedures for clinical practice guidelines development with use of relevant literature selected by the expert authors. Statements without grading were considered justified as standard clinical practice by the experts and the ESMO faculty.

Below are some highlights of the guidelines, which cover a wide array of topics regarding the diagnosis, staging, treatment, and progression of CLL disease.

Diagnosis

The guidelines indicate that CLL diagnosis is usually possible by immunophenotyping of peripheral blood only and that lymph node (LN) biopsy and/or bone marrow biopsy may be helpful if immunophenotyping is not conclusive for the diagnosis of CLL, according to Barbara Eichhorst, MD, of the University of Cologne (Germany) and colleagues on behalf of the ESMO guidelines committee.

Staging and risk assessment

Early asymptomatic-stage disease does not need further risk assessment, but after the first year, when all patients should be seen at 3-monthly intervals, patients can be followed every 3-12 months. The interval would depend on burden and dynamics of the disease obtained by the using history and physical examinations, including a careful palpation of all LN areas, spleen, and liver, as well as assessing complete blood cell count and differential count, according to the report.

Advanced- and symptomatic-stage disease requires a broader examination including imaging, history and status of relevant infections, and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) assays for the detection of deletion of the chromosome 17 (del[17p]) affecting the tumor protein p53 expression and, in the absence of del(17p), TP53 sequencing for detection of TP53 gene mutation, according to the authors.

Prognostication

Two clinical staging systems are typically used in CLL. Both Binet and Rai staging systems separate three groups of patients with different prognosis, although “as a consequence of more effective therapy, the overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced stage has improved and the relevance of the staging systems for prognostication has decreased,” according to the report.

The recent addition of genetic markers has also proved highly relevant to identifying patients with different prognoses and to guide treatment.

Therapy

Although CLL is an incurable disease, choice and application of treatment are strongly tied to the length of survival, according to the authors. The guidelines recommend Binet and Rai staging with clinical symptoms as relevant for treatment indication. In addition, the identification of del(17p), TP53 mutations, and IGHV status are relevant for choice of therapy and should be assessed prior to treatment.

The guidelines discuss specific treatment modalities for various stages of the disease, from early stages to relapse.

For frontline therapy, different treatment strategies are available including continuous treatment with Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK)–inhibitors, such as ibrutinib, until progression or time-limited therapy with ChT backbone and CD20 antibodies. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency have recently approved the combination of venetoclax plus obinutuzumab for first-line therapy of CLL.

Treatment decisions should include an assessment of IGHV and TP53 status, as well as patient-related factors such as comedication, comorbidities, preferences, drug availability, and potential of treatment adherence, according to the guidelines.

In case of symptomatic relapse within 3 years after fixed-duration therapy or nonresponse to therapy, the guidelines recommend that the therapeutic regimen should be changed, regardless of the type of first-line either to venetoclax plus rituximab for 24 months or to ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or other BTK inhibitors (if available) as continuous therapy.

The guidelines also discuss the possible roles for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies, as well as the treatment of the various complications that can arise in patients with CLL, and dealing with various aspects of disease progression.

No external funds were provided for the production of the guidelines. The authors of the report and members of the ESMO Guidelines Committee reported numerous disclosures regarding pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Eichhorst B et al. Ann Oncol. 2020 Oct 19. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.019.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY

Can AML patients be too old for cell transplantation?

How old is too old for a patient to undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)? That’s the wrong question to ask, a hematologist/oncologist told colleagues at the virtual Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus. Instead, he said, look at other factors such as disease status and genetics.

“Transplantation for older patients, even beyond the age of 70, is acceptable, as long as it’s done with caution, care, and wisdom. So we’re all not too old for transplantation, at least not today,” said Daniel Weisdorf, MD, professor of medicine and deputy director of the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

As he noted, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is often fatal. Among the general population, “the expected survival life expectancy at age 75 is 98% at 1 year, and most people living at 75 go on to live more than 10 years,” he said. “But if you have AML, at age 75, you have 20% survival at 1 year, 4% at 3 years. And since the median age of AML diagnosis is 68, and 75% of patients are diagnosed beyond the age of 55, this becomes relevant.”

Risk factors that affect survival after transplantation “certainly include age, but that interacts directly with the comorbidities people accumulate with age, their assessments of frailty, and their Karnofsky performance status, as well as the disease phenotype and molecular genetic markers,” Dr. Weisdorf said. “Perhaps most importantly, though not addressed very much, is patients’ willingness to undertake intensive therapy and their life outlook related to patient-reported outcomes when they get older.”

Despite the lack of indications that higher age by itself is an influential factor in survival after transplant, “we are generally reluctant to push the age of eligibility,” Dr. Weisdorf said. He noted that recently published American Society of Hematology guidelines for treatment of AML over the age of 55 “don’t discuss anything about transplantation fitness because they didn’t want to tackle that.”

Overall survival (OS) at 1 year after allogenic transplants only dipped slightly from ages 51-60 to 71 and above, according to Dr. Weisdorf’s analysis of U.S. data collected by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research for the time period 2005-2019.

OS was 67.6% (66.8%-68.3%) for the 41-50 age group (n = 9,287) and 57.9% (56.1%-59.8%) for the 71 and older group, Dr. Weisdorf found. Overall, OS dropped by about 4 percentage points per decade of age, he said, revealing a “modest influence” of advancing years.

His analysis of autologous transplant data from the same source, also for 2005-2019, revealed “essentially no age influence.” OS was 90.8% (90.3%-91.2%) for the 41-50 age group (n = 15,075) and 86.6% (85.9%-87.3%) for the 71 and older group (n = 7,247).

Dr. Weisdorf also highlighted unpublished research that suggests that cord-blood transplant recipients older than 70 face a significantly higher risk of death than that of younger patients in the same category. Cord blood “may be option of last resort” because of a lack of other options, he explained. “And it may be part of the learning curve of cord blood transplantation, which grew a little bit in the early 2000s, and maybe past 2010, and then fell off as everybody got enamored with the haploidentical transplant option.”

How can physicians make decisions about transplants in older patients? “The transplant comorbidity index, the specific comorbidities themselves, performance score, and frailty are all measures of somebody’s fitness to be a good candidate for transplant, really at any age,” Dr. Weisdorf said. “But we also have to recognize that disease status, genetics, and the risk phenotype remain critical and should influence decision making.”

However, even as transplant survival improves overall, “very few people are incorporating any very specific biological markers” in decision-making, he said. “We’ve gotten to measures of frailty, but we haven’t gotten to any biologic measures of cytokines or other things that would predict poor chances for doing well. So I’m afraid we’re still standing at the foot of the bed saying: ‘You look okay.’ Or we’re measuring their comorbidity index. But it is disappointing that we’re using mostly very simple clinical measures to decide if somebody is sturdy enough to proceed, and we perhaps need something better. But I don’t have a great suggestion what it should be.”

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

Dr. Weisdorf disclosed consulting fees from Fate Therapeutics and Incyte Corp.

SOURCE: “The Ever-Increasing Upper Age for Transplant: Is This Evidence-Based?” Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus, Oct. 15, 2020.

How old is too old for a patient to undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)? That’s the wrong question to ask, a hematologist/oncologist told colleagues at the virtual Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus. Instead, he said, look at other factors such as disease status and genetics.

“Transplantation for older patients, even beyond the age of 70, is acceptable, as long as it’s done with caution, care, and wisdom. So we’re all not too old for transplantation, at least not today,” said Daniel Weisdorf, MD, professor of medicine and deputy director of the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

As he noted, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is often fatal. Among the general population, “the expected survival life expectancy at age 75 is 98% at 1 year, and most people living at 75 go on to live more than 10 years,” he said. “But if you have AML, at age 75, you have 20% survival at 1 year, 4% at 3 years. And since the median age of AML diagnosis is 68, and 75% of patients are diagnosed beyond the age of 55, this becomes relevant.”

Risk factors that affect survival after transplantation “certainly include age, but that interacts directly with the comorbidities people accumulate with age, their assessments of frailty, and their Karnofsky performance status, as well as the disease phenotype and molecular genetic markers,” Dr. Weisdorf said. “Perhaps most importantly, though not addressed very much, is patients’ willingness to undertake intensive therapy and their life outlook related to patient-reported outcomes when they get older.”

Despite the lack of indications that higher age by itself is an influential factor in survival after transplant, “we are generally reluctant to push the age of eligibility,” Dr. Weisdorf said. He noted that recently published American Society of Hematology guidelines for treatment of AML over the age of 55 “don’t discuss anything about transplantation fitness because they didn’t want to tackle that.”

Overall survival (OS) at 1 year after allogenic transplants only dipped slightly from ages 51-60 to 71 and above, according to Dr. Weisdorf’s analysis of U.S. data collected by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research for the time period 2005-2019.

OS was 67.6% (66.8%-68.3%) for the 41-50 age group (n = 9,287) and 57.9% (56.1%-59.8%) for the 71 and older group, Dr. Weisdorf found. Overall, OS dropped by about 4 percentage points per decade of age, he said, revealing a “modest influence” of advancing years.

His analysis of autologous transplant data from the same source, also for 2005-2019, revealed “essentially no age influence.” OS was 90.8% (90.3%-91.2%) for the 41-50 age group (n = 15,075) and 86.6% (85.9%-87.3%) for the 71 and older group (n = 7,247).

Dr. Weisdorf also highlighted unpublished research that suggests that cord-blood transplant recipients older than 70 face a significantly higher risk of death than that of younger patients in the same category. Cord blood “may be option of last resort” because of a lack of other options, he explained. “And it may be part of the learning curve of cord blood transplantation, which grew a little bit in the early 2000s, and maybe past 2010, and then fell off as everybody got enamored with the haploidentical transplant option.”

How can physicians make decisions about transplants in older patients? “The transplant comorbidity index, the specific comorbidities themselves, performance score, and frailty are all measures of somebody’s fitness to be a good candidate for transplant, really at any age,” Dr. Weisdorf said. “But we also have to recognize that disease status, genetics, and the risk phenotype remain critical and should influence decision making.”

However, even as transplant survival improves overall, “very few people are incorporating any very specific biological markers” in decision-making, he said. “We’ve gotten to measures of frailty, but we haven’t gotten to any biologic measures of cytokines or other things that would predict poor chances for doing well. So I’m afraid we’re still standing at the foot of the bed saying: ‘You look okay.’ Or we’re measuring their comorbidity index. But it is disappointing that we’re using mostly very simple clinical measures to decide if somebody is sturdy enough to proceed, and we perhaps need something better. But I don’t have a great suggestion what it should be.”

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

Dr. Weisdorf disclosed consulting fees from Fate Therapeutics and Incyte Corp.

SOURCE: “The Ever-Increasing Upper Age for Transplant: Is This Evidence-Based?” Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus, Oct. 15, 2020.

How old is too old for a patient to undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)? That’s the wrong question to ask, a hematologist/oncologist told colleagues at the virtual Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus. Instead, he said, look at other factors such as disease status and genetics.

“Transplantation for older patients, even beyond the age of 70, is acceptable, as long as it’s done with caution, care, and wisdom. So we’re all not too old for transplantation, at least not today,” said Daniel Weisdorf, MD, professor of medicine and deputy director of the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

As he noted, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is often fatal. Among the general population, “the expected survival life expectancy at age 75 is 98% at 1 year, and most people living at 75 go on to live more than 10 years,” he said. “But if you have AML, at age 75, you have 20% survival at 1 year, 4% at 3 years. And since the median age of AML diagnosis is 68, and 75% of patients are diagnosed beyond the age of 55, this becomes relevant.”

Risk factors that affect survival after transplantation “certainly include age, but that interacts directly with the comorbidities people accumulate with age, their assessments of frailty, and their Karnofsky performance status, as well as the disease phenotype and molecular genetic markers,” Dr. Weisdorf said. “Perhaps most importantly, though not addressed very much, is patients’ willingness to undertake intensive therapy and their life outlook related to patient-reported outcomes when they get older.”

Despite the lack of indications that higher age by itself is an influential factor in survival after transplant, “we are generally reluctant to push the age of eligibility,” Dr. Weisdorf said. He noted that recently published American Society of Hematology guidelines for treatment of AML over the age of 55 “don’t discuss anything about transplantation fitness because they didn’t want to tackle that.”

Overall survival (OS) at 1 year after allogenic transplants only dipped slightly from ages 51-60 to 71 and above, according to Dr. Weisdorf’s analysis of U.S. data collected by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research for the time period 2005-2019.

OS was 67.6% (66.8%-68.3%) for the 41-50 age group (n = 9,287) and 57.9% (56.1%-59.8%) for the 71 and older group, Dr. Weisdorf found. Overall, OS dropped by about 4 percentage points per decade of age, he said, revealing a “modest influence” of advancing years.

His analysis of autologous transplant data from the same source, also for 2005-2019, revealed “essentially no age influence.” OS was 90.8% (90.3%-91.2%) for the 41-50 age group (n = 15,075) and 86.6% (85.9%-87.3%) for the 71 and older group (n = 7,247).

Dr. Weisdorf also highlighted unpublished research that suggests that cord-blood transplant recipients older than 70 face a significantly higher risk of death than that of younger patients in the same category. Cord blood “may be option of last resort” because of a lack of other options, he explained. “And it may be part of the learning curve of cord blood transplantation, which grew a little bit in the early 2000s, and maybe past 2010, and then fell off as everybody got enamored with the haploidentical transplant option.”

How can physicians make decisions about transplants in older patients? “The transplant comorbidity index, the specific comorbidities themselves, performance score, and frailty are all measures of somebody’s fitness to be a good candidate for transplant, really at any age,” Dr. Weisdorf said. “But we also have to recognize that disease status, genetics, and the risk phenotype remain critical and should influence decision making.”

However, even as transplant survival improves overall, “very few people are incorporating any very specific biological markers” in decision-making, he said. “We’ve gotten to measures of frailty, but we haven’t gotten to any biologic measures of cytokines or other things that would predict poor chances for doing well. So I’m afraid we’re still standing at the foot of the bed saying: ‘You look okay.’ Or we’re measuring their comorbidity index. But it is disappointing that we’re using mostly very simple clinical measures to decide if somebody is sturdy enough to proceed, and we perhaps need something better. But I don’t have a great suggestion what it should be.”

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

Dr. Weisdorf disclosed consulting fees from Fate Therapeutics and Incyte Corp.

SOURCE: “The Ever-Increasing Upper Age for Transplant: Is This Evidence-Based?” Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus, Oct. 15, 2020.

FROM ALF 2020

Older age, r/r disease in lymphoma patients tied to increased COVID-19 death rate

Patients with B-cell lymphoma are immunocompromised because of the disease and its treatments. This presents the question of their outcomes upon infection with SARS-CoV-2. Researchers assessed the characteristics of patients with lymphoma hospitalized for COVID-19 and analyzed determinants of mortality in a retrospective database study. The investigators looked at data from adult patients with lymphoma who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020 in three French regions.

Older age and relapsed/refractory (r/r) disease in B-cell lymphoma patients were both found to be independent risk factors of increased death rate from COVID-19, according to the online report in EClinicalMedicine, published by The Lancet.

These results encourage “the application of standard Covid-19 treatment, including intubation, for lymphoma patients with Covid-19 lymphoma diagnosis, under first- or second-line chemotherapy, or in remission,” according to Sylvain Lamure, MD, of Montellier (France) University, and colleagues.

The study examined a series of 89 consecutive patients from three French regions who had lymphoma and were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020. The population was homogeneous; most patients were diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and had been treated for their lymphoma within 1 year.

Promising results for many

There were a significant associations between 30-day mortality and increasing age (over age 70 years) and r/r lymphoma. However, in the absence of those factors, mortality of the lymphoma patients with COVID-19 was comparable with that of the reference French COVID-19 population. In addition, there was no significant impact of active lymphoma treatment that had been given within 1 year, except for those patients who received bendamustine, which was associated with greater mortality, according to the researchers.

With a median follow-up of 33 days from admission, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 30-day overall survival was 71% (95% confidence interval, 62%-81%). According to histological type of the lymphoma, 30-day overall survival rates were 80% (95% CI, 45%-100%) for Hodgkin lymphoma, 71% (95% CI, 61%-82%) for B-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and 71% (95% CI, 38%-100%) for T-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

The main factors associated with mortality were age 70 years and older (hazard ratio, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.73-8.25; P = .0009), hypertension (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.06-4.59; P = .03), previous cancer (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.90-4.92; P = .08), use of bendamustine within 12 months before admission to hospital (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.31-7.11; P = .01), and r/r lymphoma (HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.20-5.72; P = .02).

Overall, the Kaplan-Meier estimates of 30-day overall survival were 61% for patients with r/r lymphoma, 52% in patients age 70 years with non–r/r lymphoma, and 88% for patients younger than 70 years with non–r/r, which was comparable with general population survival data among French populations, according to the researchers.

“Longer term clinical follow-up and biological monitoring of immune responses is warranted to explore the impact of lymphoma and its treatment on the immunity and prolonged outcome of Covid-19 patients,” they concluded.

The study was unsponsored. Several of the authors reported financial relationships with a number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lamure S et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100549.

Patients with B-cell lymphoma are immunocompromised because of the disease and its treatments. This presents the question of their outcomes upon infection with SARS-CoV-2. Researchers assessed the characteristics of patients with lymphoma hospitalized for COVID-19 and analyzed determinants of mortality in a retrospective database study. The investigators looked at data from adult patients with lymphoma who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020 in three French regions.

Older age and relapsed/refractory (r/r) disease in B-cell lymphoma patients were both found to be independent risk factors of increased death rate from COVID-19, according to the online report in EClinicalMedicine, published by The Lancet.

These results encourage “the application of standard Covid-19 treatment, including intubation, for lymphoma patients with Covid-19 lymphoma diagnosis, under first- or second-line chemotherapy, or in remission,” according to Sylvain Lamure, MD, of Montellier (France) University, and colleagues.

The study examined a series of 89 consecutive patients from three French regions who had lymphoma and were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020. The population was homogeneous; most patients were diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and had been treated for their lymphoma within 1 year.

Promising results for many

There were a significant associations between 30-day mortality and increasing age (over age 70 years) and r/r lymphoma. However, in the absence of those factors, mortality of the lymphoma patients with COVID-19 was comparable with that of the reference French COVID-19 population. In addition, there was no significant impact of active lymphoma treatment that had been given within 1 year, except for those patients who received bendamustine, which was associated with greater mortality, according to the researchers.

With a median follow-up of 33 days from admission, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 30-day overall survival was 71% (95% confidence interval, 62%-81%). According to histological type of the lymphoma, 30-day overall survival rates were 80% (95% CI, 45%-100%) for Hodgkin lymphoma, 71% (95% CI, 61%-82%) for B-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and 71% (95% CI, 38%-100%) for T-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

The main factors associated with mortality were age 70 years and older (hazard ratio, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.73-8.25; P = .0009), hypertension (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.06-4.59; P = .03), previous cancer (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.90-4.92; P = .08), use of bendamustine within 12 months before admission to hospital (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.31-7.11; P = .01), and r/r lymphoma (HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.20-5.72; P = .02).

Overall, the Kaplan-Meier estimates of 30-day overall survival were 61% for patients with r/r lymphoma, 52% in patients age 70 years with non–r/r lymphoma, and 88% for patients younger than 70 years with non–r/r, which was comparable with general population survival data among French populations, according to the researchers.

“Longer term clinical follow-up and biological monitoring of immune responses is warranted to explore the impact of lymphoma and its treatment on the immunity and prolonged outcome of Covid-19 patients,” they concluded.

The study was unsponsored. Several of the authors reported financial relationships with a number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lamure S et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100549.

Patients with B-cell lymphoma are immunocompromised because of the disease and its treatments. This presents the question of their outcomes upon infection with SARS-CoV-2. Researchers assessed the characteristics of patients with lymphoma hospitalized for COVID-19 and analyzed determinants of mortality in a retrospective database study. The investigators looked at data from adult patients with lymphoma who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020 in three French regions.

Older age and relapsed/refractory (r/r) disease in B-cell lymphoma patients were both found to be independent risk factors of increased death rate from COVID-19, according to the online report in EClinicalMedicine, published by The Lancet.

These results encourage “the application of standard Covid-19 treatment, including intubation, for lymphoma patients with Covid-19 lymphoma diagnosis, under first- or second-line chemotherapy, or in remission,” according to Sylvain Lamure, MD, of Montellier (France) University, and colleagues.

The study examined a series of 89 consecutive patients from three French regions who had lymphoma and were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020. The population was homogeneous; most patients were diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and had been treated for their lymphoma within 1 year.

Promising results for many

There were a significant associations between 30-day mortality and increasing age (over age 70 years) and r/r lymphoma. However, in the absence of those factors, mortality of the lymphoma patients with COVID-19 was comparable with that of the reference French COVID-19 population. In addition, there was no significant impact of active lymphoma treatment that had been given within 1 year, except for those patients who received bendamustine, which was associated with greater mortality, according to the researchers.

With a median follow-up of 33 days from admission, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 30-day overall survival was 71% (95% confidence interval, 62%-81%). According to histological type of the lymphoma, 30-day overall survival rates were 80% (95% CI, 45%-100%) for Hodgkin lymphoma, 71% (95% CI, 61%-82%) for B-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and 71% (95% CI, 38%-100%) for T-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

The main factors associated with mortality were age 70 years and older (hazard ratio, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.73-8.25; P = .0009), hypertension (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.06-4.59; P = .03), previous cancer (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.90-4.92; P = .08), use of bendamustine within 12 months before admission to hospital (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.31-7.11; P = .01), and r/r lymphoma (HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.20-5.72; P = .02).

Overall, the Kaplan-Meier estimates of 30-day overall survival were 61% for patients with r/r lymphoma, 52% in patients age 70 years with non–r/r lymphoma, and 88% for patients younger than 70 years with non–r/r, which was comparable with general population survival data among French populations, according to the researchers.

“Longer term clinical follow-up and biological monitoring of immune responses is warranted to explore the impact of lymphoma and its treatment on the immunity and prolonged outcome of Covid-19 patients,” they concluded.

The study was unsponsored. Several of the authors reported financial relationships with a number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lamure S et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100549.

FROM ECLINICALMEDICINE

Efforts to close the ‘AYA gap’ in lymphoma

In the 1970s, cancer survival was poor for young children and older adults in the United States, as shown by data published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Great progress has been made since the 1970s, but improvements in outcome have been less impressive for cancer patients aged 15-39 years, as shown by research published in Cancer.

Patients aged 15-39 years have been designated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as “adolescents and young adults (AYAs),” and the lag in survival benefit has been termed “the AYA gap.”

The AYA gap persists in lymphoma patients, and an expert panel recently outlined differences between lymphoma in AYAs and lymphoma in other age groups.

The experts spoke at a special session of the AACR Virtual Meeting: Advances in Malignant Lymphoma moderated by Somali M. Smith, MD, of the University of Chicago.

Factors that contribute to the AYA gap

About 89,000 AYAs are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States, according to data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Lymphomas and thyroid cancer are the most common cancers among younger AYAs, aged 15-24 years.

In a report commissioned by the NIH in 2006, many factors contributing to the AYA gap were identified. Chief among them were:

- Limitations in access to care.

- Delayed diagnosis.

- Inconsistency in treatment and follow-up.

- Long-term toxicity (fertility, second malignancies, and cardiovascular disease).

These factors compromise health-related survival, even when cancer-specific survival is improved.

Panelist Kara Kelly, MD, of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, N.Y., noted that there are additional unique challenges for AYAs with cancer. These include:

- Pubertal changes.

- Developmental transition to independence.

- Societal impediments such as insurance coverage and disparities in access to specialized centers.

- Psychosocial factors such as health literacy and adherence to treatment and follow-up.

Focusing on lymphoma specifically, Dr. Kelly noted that lymphoma biology differs across the age spectrum and by race and ethnicity. Both tumor and host factors require further study, she said.

Clinical trial access for AYAs

Dr. Kelly emphasized that, unfortunately, clinical research participation is low among AYAs. A major impediment is that adult clinical trials historically required participants to be at least 18 years old.

In addition, there has not been a focused effort to educate AYAs about regulatory safeguards to ensure safety and the promise of enhanced benefit to them in NCI Cancer Trials Network (NCTN) trials. As a result, the refusal rate is high.

A multi-stakeholder workshop, convened in May 2016 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research, outlined opportunities for expanding trial eligibility to include children younger than 18 years in first-in-human and other adult cancer clinical trials, enhancing their access to new agents, without compromising safety.

Recently, collaborative efforts between the adult and children’s NCTN research groups have included AYAs in studies addressing cancers that span the age spectrum, including lymphoma.

However, as Dr. Kelly noted, there are differences in AYA lymphoid malignancy types with a transition from more pediatric to more adult types.

Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma

Panelist Lisa G. Roth, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, reviewed the genomic landscape of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL).

Dr. Roth explained that both HL and PMBCL are derived from thymic B cells, predominantly affect the mediastinum, and are CD30-positive lymphomas. Both are characterized by upregulation of JAK/STAT and NF-kappaB as well as overexpression of PD-L1.

Dr. Roth noted that HL is challenging to sequence by standard methods because Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells represent less than 1% of the cellular infiltrate. Recurrently mutated genes in HL cluster by histologic subtype.

Whole-exome sequencing of HRS cells show loss of beta-2 microglobulin and MHC-1 expression, HLA-B, NF-kappaB signaling, and JAK-STAT signaling, according to data published in Blood Advances in 2019.

Dr. Roth’s lab performed immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays in 145 cases of HL (unpublished data). Results showed that loss of beta-2 microglobulin is more common in younger HL patients. For other alterations, there were too few cases to know.

Dr. Roth’s lab is a member of a pediatric/AYA HL sequencing multi-institutional consortium that has been able to extract DNA and RNA from samples submitted for whole-exome sequencing. The consortium’s goal is to shed light on implications of other genomic alterations that may differ by age in HL patients.

Dr. Roth cited research showing that PMBCL shares molecular alterations similar to those of HL. Alterations in PMBCL suggest dysregulated cellular signaling and immune evasion mechanisms (e.g., deletions in MHC type 1 and 2, beta-2 microglobulin, JAK-STAT, and NF-kappaB mutations) that provide opportunities to study novel agents, according to data published in Blood in 2019.

By early 2021, the S1826 and ANHL1931 studies, which have no age restriction, will be available to AYA lymphoma patients with HL and PMBCL, respectively, Dr. Roth said.

Follicular lymphoma: Clinical features by age

Panelist Abner Louissaint Jr, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed age-related differences in follicular lymphoma (FL).

He noted that FL typically presents at an advanced stage, with low- or high-grade histology. It is increasingly common in adults in their 50s and 60s, representing 20% of all lymphomas. FL is rare in children and AYAs.

Dr. Louissaint explained that the typical flow cytometric findings in FL are BCL2 translocations, occurring in up to 85%-90% of low-grade and 50% of high-grade cases. The t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation juxtaposes BCL2 on 18q21 to regulatory sequences and enhances the expression of elements of the Ig heavy chain.

Malignant cells in FL patients express CD20, CD10, CD21, and BCL2 (in contrast to normal germinal centers) and overexpress BCL6 (in contrast to normal follicles), Dr. Louissaint noted. He said the Ki-67 proliferative index of the malignant cells is typically low.

Pediatric-type FL is rare, but case series show clinical, pathologic, and molecular features that are distinctive from adult FL, Dr. Louissaint explained.

He then discussed the features of pediatric-type FL in multiple domains. In the clinical domain, there is a male predilection, and stage tends to be low. There is frequent involvement of nodes of the head and neck region and rare involvement of internal lymph node chains.

Pathologically, the malignant cells appear high grade, with architectural effacement, expansile follicular pattern, large lymphocyte size, and an elevated proliferation index. In contrast to adult FL, malignant cells in pediatric-type FL lack aberrant BCL2 expression.

Most importantly, for pediatric-type FL, the prognosis is excellent with durable remissions after surgical excision, Dr. Louissaint said.

Follicular lymphoma: Molecular features by age

Because of the excellent prognosis in pediatric-type FL, it is important to assess whether young adults with FL have adult-type or pediatric-type lesions, Dr. Louissaint said.

He cited many studies showing differences in adult and pediatric-type FL. In adult FL, the mutational landscape is characterized by frequent chromatin-modifying mutations in genes such as CREBBP, KM22D, and EP300.

In contrast, in pediatric-type FL, there are frequent activating MAPK pathway mutations, including mutations in the negative regulatory domain of MAP2K1. These mutations are not seen in adult FL.

Dr. Louissaint noted that there may be mutations in epigenetic modifiers (CREBBP, TNFRSF14) in both adult and pediatric-type FL. However, CREBBP is very unusual in pediatric-type FL and common in adult FL. This suggests the alterations in pediatric-type FL do not simply represent an early stage of the same disease as adult FL.

Despite a high proliferating fraction and absence of BCL2/BCL6/IRF4 rearrangements in pediatric-type FL, the presence of these features was associated with dramatic difference in progression-free survival, according to research published in Blood in 2012.

A distinct entity

In 2016, the World Health Organization recognized pediatric-type FL as a distinct entity, with the following diagnostic criteria (published in Blood):

- At least partial effacement of nodal architecture, expansile follicles, intermediate-size blastoid cells, and no component of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- Immunohistochemistry showing BCL6 positivity, BCL2 negativity or weak positivity, and a high proliferative fraction.

- Genomic studies showing no BCL2 amplification.

- Clinical features of nodal disease in the head and neck region, early clinical stage, age younger than 40 years, typically in a male with no internal nodes involved.

When FL occurs in AYAs, the diagnostic findings of pediatric-type FL suggest the patient will do well with conservative management (e.g., excision alone), Dr. Louissaint noted.

Two sizes do not fit all

The strategies that have improved cancer outcomes since the 1970s for children and older adults have been much less successful for AYAs with cancer.

As an oncologic community, we should not allow the AYA gap to persist. As always, the solutions are likely to involve focused clinical research, education, and communication. Effort will need to be targeted specifically to the AYA population.

Since health-related mortality is high even when cancer-specific outcomes improve, adopting and maintaining a healthy lifestyle must be a key part of the discussion with these young patients.

The biologic differences associated with AYA lymphomas demand participation in clinical trials.

Oncologists should vigorously support removing impediments to the participation of AYAs in prospective clinical trials, stratified (but unrestricted) by age, with careful analysis of patient-reported outcomes, late adverse effects, and biospecimen collection.

As Dr. Kelly noted in the question-and-answer period, the Children’s Oncology Group has an existing biobank of paraffin-embedded tumor samples, DNA from lymphoma specimens, plasma, and sera with clinically annotated data that can be given to investigators upon request and justification.

Going beyond eligibility for clinical trials

Unfortunately, we will likely find that broadening eligibility criteria is the “low-hanging fruit.” There are protocol-, patient-, and physician-related obstacles, according to a review published in Cancer in 2019.

Patient-related obstacles include fear of toxicity, uncertainty about placebos, a steep learning curve for health literacy, insurance-related impediments, and other access-related issues.

Discussions will need to be tailored to the AYA population. Frank, early conversations about fertility, sexuality, financial hardship, career advancement, work-life balance, and cognitive risks may not only facilitate treatment planning but also encourage the trust that is essential for patients to enroll in trials.

The investment in time, multidisciplinary staff and physician involvement, and potential delays in treatment initiation may be painful and inconvenient, but the benefits for long-term health outcomes and personal-professional relationships will be gratifying beyond measure.

Dr. Smith disclosed relationships with Genentech/Roche, Celgene, TGTX, Karyopharm, Janssen, and Bantem. Dr. Roth disclosed relationships with Janssen, ADC Therapeutics, and Celgene. Dr. Kelly and Dr. Louissaint had no financial relationships to disclose.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

In the 1970s, cancer survival was poor for young children and older adults in the United States, as shown by data published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Great progress has been made since the 1970s, but improvements in outcome have been less impressive for cancer patients aged 15-39 years, as shown by research published in Cancer.

Patients aged 15-39 years have been designated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as “adolescents and young adults (AYAs),” and the lag in survival benefit has been termed “the AYA gap.”

The AYA gap persists in lymphoma patients, and an expert panel recently outlined differences between lymphoma in AYAs and lymphoma in other age groups.

The experts spoke at a special session of the AACR Virtual Meeting: Advances in Malignant Lymphoma moderated by Somali M. Smith, MD, of the University of Chicago.

Factors that contribute to the AYA gap

About 89,000 AYAs are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States, according to data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Lymphomas and thyroid cancer are the most common cancers among younger AYAs, aged 15-24 years.

In a report commissioned by the NIH in 2006, many factors contributing to the AYA gap were identified. Chief among them were:

- Limitations in access to care.

- Delayed diagnosis.

- Inconsistency in treatment and follow-up.

- Long-term toxicity (fertility, second malignancies, and cardiovascular disease).

These factors compromise health-related survival, even when cancer-specific survival is improved.

Panelist Kara Kelly, MD, of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, N.Y., noted that there are additional unique challenges for AYAs with cancer. These include:

- Pubertal changes.

- Developmental transition to independence.

- Societal impediments such as insurance coverage and disparities in access to specialized centers.

- Psychosocial factors such as health literacy and adherence to treatment and follow-up.

Focusing on lymphoma specifically, Dr. Kelly noted that lymphoma biology differs across the age spectrum and by race and ethnicity. Both tumor and host factors require further study, she said.

Clinical trial access for AYAs

Dr. Kelly emphasized that, unfortunately, clinical research participation is low among AYAs. A major impediment is that adult clinical trials historically required participants to be at least 18 years old.

In addition, there has not been a focused effort to educate AYAs about regulatory safeguards to ensure safety and the promise of enhanced benefit to them in NCI Cancer Trials Network (NCTN) trials. As a result, the refusal rate is high.

A multi-stakeholder workshop, convened in May 2016 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research, outlined opportunities for expanding trial eligibility to include children younger than 18 years in first-in-human and other adult cancer clinical trials, enhancing their access to new agents, without compromising safety.

Recently, collaborative efforts between the adult and children’s NCTN research groups have included AYAs in studies addressing cancers that span the age spectrum, including lymphoma.

However, as Dr. Kelly noted, there are differences in AYA lymphoid malignancy types with a transition from more pediatric to more adult types.

Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma

Panelist Lisa G. Roth, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, reviewed the genomic landscape of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL).

Dr. Roth explained that both HL and PMBCL are derived from thymic B cells, predominantly affect the mediastinum, and are CD30-positive lymphomas. Both are characterized by upregulation of JAK/STAT and NF-kappaB as well as overexpression of PD-L1.

Dr. Roth noted that HL is challenging to sequence by standard methods because Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells represent less than 1% of the cellular infiltrate. Recurrently mutated genes in HL cluster by histologic subtype.

Whole-exome sequencing of HRS cells show loss of beta-2 microglobulin and MHC-1 expression, HLA-B, NF-kappaB signaling, and JAK-STAT signaling, according to data published in Blood Advances in 2019.

Dr. Roth’s lab performed immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays in 145 cases of HL (unpublished data). Results showed that loss of beta-2 microglobulin is more common in younger HL patients. For other alterations, there were too few cases to know.

Dr. Roth’s lab is a member of a pediatric/AYA HL sequencing multi-institutional consortium that has been able to extract DNA and RNA from samples submitted for whole-exome sequencing. The consortium’s goal is to shed light on implications of other genomic alterations that may differ by age in HL patients.

Dr. Roth cited research showing that PMBCL shares molecular alterations similar to those of HL. Alterations in PMBCL suggest dysregulated cellular signaling and immune evasion mechanisms (e.g., deletions in MHC type 1 and 2, beta-2 microglobulin, JAK-STAT, and NF-kappaB mutations) that provide opportunities to study novel agents, according to data published in Blood in 2019.

By early 2021, the S1826 and ANHL1931 studies, which have no age restriction, will be available to AYA lymphoma patients with HL and PMBCL, respectively, Dr. Roth said.

Follicular lymphoma: Clinical features by age

Panelist Abner Louissaint Jr, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed age-related differences in follicular lymphoma (FL).

He noted that FL typically presents at an advanced stage, with low- or high-grade histology. It is increasingly common in adults in their 50s and 60s, representing 20% of all lymphomas. FL is rare in children and AYAs.

Dr. Louissaint explained that the typical flow cytometric findings in FL are BCL2 translocations, occurring in up to 85%-90% of low-grade and 50% of high-grade cases. The t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation juxtaposes BCL2 on 18q21 to regulatory sequences and enhances the expression of elements of the Ig heavy chain.

Malignant cells in FL patients express CD20, CD10, CD21, and BCL2 (in contrast to normal germinal centers) and overexpress BCL6 (in contrast to normal follicles), Dr. Louissaint noted. He said the Ki-67 proliferative index of the malignant cells is typically low.

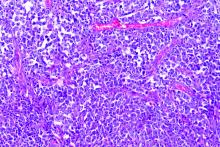

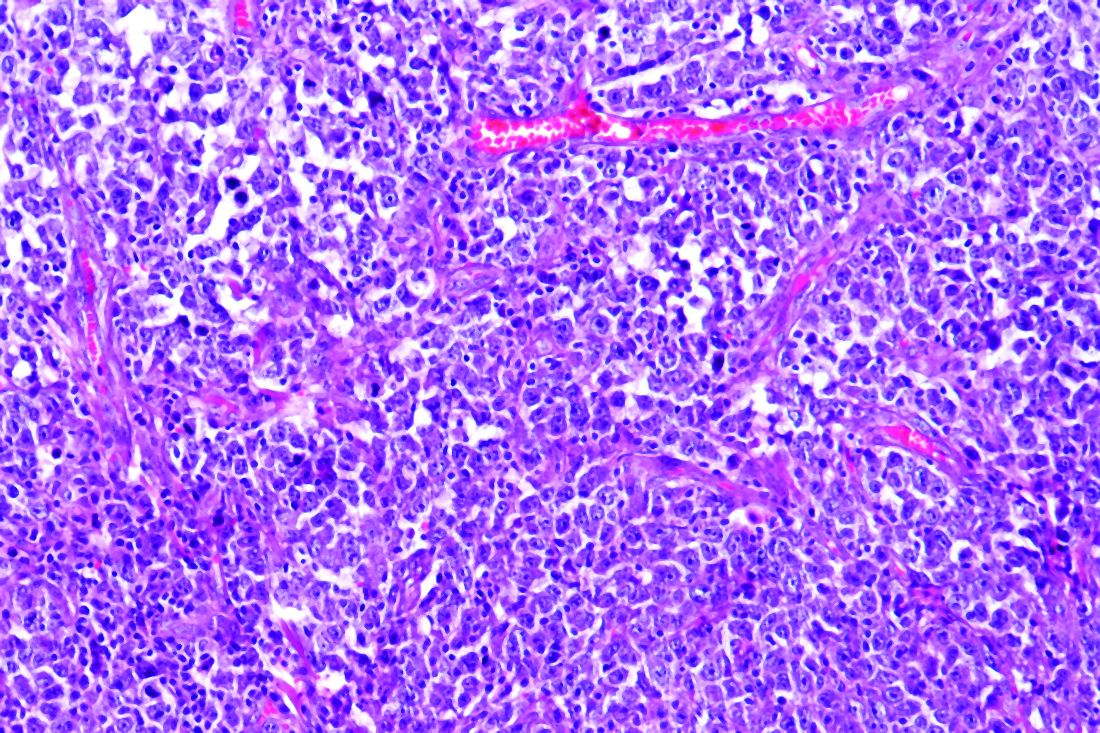

Pediatric-type FL is rare, but case series show clinical, pathologic, and molecular features that are distinctive from adult FL, Dr. Louissaint explained.

He then discussed the features of pediatric-type FL in multiple domains. In the clinical domain, there is a male predilection, and stage tends to be low. There is frequent involvement of nodes of the head and neck region and rare involvement of internal lymph node chains.

Pathologically, the malignant cells appear high grade, with architectural effacement, expansile follicular pattern, large lymphocyte size, and an elevated proliferation index. In contrast to adult FL, malignant cells in pediatric-type FL lack aberrant BCL2 expression.

Most importantly, for pediatric-type FL, the prognosis is excellent with durable remissions after surgical excision, Dr. Louissaint said.

Follicular lymphoma: Molecular features by age

Because of the excellent prognosis in pediatric-type FL, it is important to assess whether young adults with FL have adult-type or pediatric-type lesions, Dr. Louissaint said.

He cited many studies showing differences in adult and pediatric-type FL. In adult FL, the mutational landscape is characterized by frequent chromatin-modifying mutations in genes such as CREBBP, KM22D, and EP300.

In contrast, in pediatric-type FL, there are frequent activating MAPK pathway mutations, including mutations in the negative regulatory domain of MAP2K1. These mutations are not seen in adult FL.

Dr. Louissaint noted that there may be mutations in epigenetic modifiers (CREBBP, TNFRSF14) in both adult and pediatric-type FL. However, CREBBP is very unusual in pediatric-type FL and common in adult FL. This suggests the alterations in pediatric-type FL do not simply represent an early stage of the same disease as adult FL.

Despite a high proliferating fraction and absence of BCL2/BCL6/IRF4 rearrangements in pediatric-type FL, the presence of these features was associated with dramatic difference in progression-free survival, according to research published in Blood in 2012.

A distinct entity

In 2016, the World Health Organization recognized pediatric-type FL as a distinct entity, with the following diagnostic criteria (published in Blood):

- At least partial effacement of nodal architecture, expansile follicles, intermediate-size blastoid cells, and no component of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- Immunohistochemistry showing BCL6 positivity, BCL2 negativity or weak positivity, and a high proliferative fraction.

- Genomic studies showing no BCL2 amplification.

- Clinical features of nodal disease in the head and neck region, early clinical stage, age younger than 40 years, typically in a male with no internal nodes involved.

When FL occurs in AYAs, the diagnostic findings of pediatric-type FL suggest the patient will do well with conservative management (e.g., excision alone), Dr. Louissaint noted.

Two sizes do not fit all

The strategies that have improved cancer outcomes since the 1970s for children and older adults have been much less successful for AYAs with cancer.

As an oncologic community, we should not allow the AYA gap to persist. As always, the solutions are likely to involve focused clinical research, education, and communication. Effort will need to be targeted specifically to the AYA population.

Since health-related mortality is high even when cancer-specific outcomes improve, adopting and maintaining a healthy lifestyle must be a key part of the discussion with these young patients.

The biologic differences associated with AYA lymphomas demand participation in clinical trials.

Oncologists should vigorously support removing impediments to the participation of AYAs in prospective clinical trials, stratified (but unrestricted) by age, with careful analysis of patient-reported outcomes, late adverse effects, and biospecimen collection.

As Dr. Kelly noted in the question-and-answer period, the Children’s Oncology Group has an existing biobank of paraffin-embedded tumor samples, DNA from lymphoma specimens, plasma, and sera with clinically annotated data that can be given to investigators upon request and justification.

Going beyond eligibility for clinical trials

Unfortunately, we will likely find that broadening eligibility criteria is the “low-hanging fruit.” There are protocol-, patient-, and physician-related obstacles, according to a review published in Cancer in 2019.

Patient-related obstacles include fear of toxicity, uncertainty about placebos, a steep learning curve for health literacy, insurance-related impediments, and other access-related issues.

Discussions will need to be tailored to the AYA population. Frank, early conversations about fertility, sexuality, financial hardship, career advancement, work-life balance, and cognitive risks may not only facilitate treatment planning but also encourage the trust that is essential for patients to enroll in trials.

The investment in time, multidisciplinary staff and physician involvement, and potential delays in treatment initiation may be painful and inconvenient, but the benefits for long-term health outcomes and personal-professional relationships will be gratifying beyond measure.

Dr. Smith disclosed relationships with Genentech/Roche, Celgene, TGTX, Karyopharm, Janssen, and Bantem. Dr. Roth disclosed relationships with Janssen, ADC Therapeutics, and Celgene. Dr. Kelly and Dr. Louissaint had no financial relationships to disclose.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

In the 1970s, cancer survival was poor for young children and older adults in the United States, as shown by data published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Great progress has been made since the 1970s, but improvements in outcome have been less impressive for cancer patients aged 15-39 years, as shown by research published in Cancer.

Patients aged 15-39 years have been designated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as “adolescents and young adults (AYAs),” and the lag in survival benefit has been termed “the AYA gap.”

The AYA gap persists in lymphoma patients, and an expert panel recently outlined differences between lymphoma in AYAs and lymphoma in other age groups.

The experts spoke at a special session of the AACR Virtual Meeting: Advances in Malignant Lymphoma moderated by Somali M. Smith, MD, of the University of Chicago.

Factors that contribute to the AYA gap

About 89,000 AYAs are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States, according to data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Lymphomas and thyroid cancer are the most common cancers among younger AYAs, aged 15-24 years.

In a report commissioned by the NIH in 2006, many factors contributing to the AYA gap were identified. Chief among them were:

- Limitations in access to care.

- Delayed diagnosis.

- Inconsistency in treatment and follow-up.

- Long-term toxicity (fertility, second malignancies, and cardiovascular disease).

These factors compromise health-related survival, even when cancer-specific survival is improved.

Panelist Kara Kelly, MD, of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, N.Y., noted that there are additional unique challenges for AYAs with cancer. These include:

- Pubertal changes.

- Developmental transition to independence.

- Societal impediments such as insurance coverage and disparities in access to specialized centers.

- Psychosocial factors such as health literacy and adherence to treatment and follow-up.

Focusing on lymphoma specifically, Dr. Kelly noted that lymphoma biology differs across the age spectrum and by race and ethnicity. Both tumor and host factors require further study, she said.

Clinical trial access for AYAs

Dr. Kelly emphasized that, unfortunately, clinical research participation is low among AYAs. A major impediment is that adult clinical trials historically required participants to be at least 18 years old.

In addition, there has not been a focused effort to educate AYAs about regulatory safeguards to ensure safety and the promise of enhanced benefit to them in NCI Cancer Trials Network (NCTN) trials. As a result, the refusal rate is high.

A multi-stakeholder workshop, convened in May 2016 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research, outlined opportunities for expanding trial eligibility to include children younger than 18 years in first-in-human and other adult cancer clinical trials, enhancing their access to new agents, without compromising safety.

Recently, collaborative efforts between the adult and children’s NCTN research groups have included AYAs in studies addressing cancers that span the age spectrum, including lymphoma.

However, as Dr. Kelly noted, there are differences in AYA lymphoid malignancy types with a transition from more pediatric to more adult types.

Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma

Panelist Lisa G. Roth, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, reviewed the genomic landscape of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL).

Dr. Roth explained that both HL and PMBCL are derived from thymic B cells, predominantly affect the mediastinum, and are CD30-positive lymphomas. Both are characterized by upregulation of JAK/STAT and NF-kappaB as well as overexpression of PD-L1.

Dr. Roth noted that HL is challenging to sequence by standard methods because Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells represent less than 1% of the cellular infiltrate. Recurrently mutated genes in HL cluster by histologic subtype.

Whole-exome sequencing of HRS cells show loss of beta-2 microglobulin and MHC-1 expression, HLA-B, NF-kappaB signaling, and JAK-STAT signaling, according to data published in Blood Advances in 2019.

Dr. Roth’s lab performed immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays in 145 cases of HL (unpublished data). Results showed that loss of beta-2 microglobulin is more common in younger HL patients. For other alterations, there were too few cases to know.

Dr. Roth’s lab is a member of a pediatric/AYA HL sequencing multi-institutional consortium that has been able to extract DNA and RNA from samples submitted for whole-exome sequencing. The consortium’s goal is to shed light on implications of other genomic alterations that may differ by age in HL patients.

Dr. Roth cited research showing that PMBCL shares molecular alterations similar to those of HL. Alterations in PMBCL suggest dysregulated cellular signaling and immune evasion mechanisms (e.g., deletions in MHC type 1 and 2, beta-2 microglobulin, JAK-STAT, and NF-kappaB mutations) that provide opportunities to study novel agents, according to data published in Blood in 2019.

By early 2021, the S1826 and ANHL1931 studies, which have no age restriction, will be available to AYA lymphoma patients with HL and PMBCL, respectively, Dr. Roth said.

Follicular lymphoma: Clinical features by age

Panelist Abner Louissaint Jr, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed age-related differences in follicular lymphoma (FL).

He noted that FL typically presents at an advanced stage, with low- or high-grade histology. It is increasingly common in adults in their 50s and 60s, representing 20% of all lymphomas. FL is rare in children and AYAs.

Dr. Louissaint explained that the typical flow cytometric findings in FL are BCL2 translocations, occurring in up to 85%-90% of low-grade and 50% of high-grade cases. The t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation juxtaposes BCL2 on 18q21 to regulatory sequences and enhances the expression of elements of the Ig heavy chain.

Malignant cells in FL patients express CD20, CD10, CD21, and BCL2 (in contrast to normal germinal centers) and overexpress BCL6 (in contrast to normal follicles), Dr. Louissaint noted. He said the Ki-67 proliferative index of the malignant cells is typically low.

Pediatric-type FL is rare, but case series show clinical, pathologic, and molecular features that are distinctive from adult FL, Dr. Louissaint explained.

He then discussed the features of pediatric-type FL in multiple domains. In the clinical domain, there is a male predilection, and stage tends to be low. There is frequent involvement of nodes of the head and neck region and rare involvement of internal lymph node chains.

Pathologically, the malignant cells appear high grade, with architectural effacement, expansile follicular pattern, large lymphocyte size, and an elevated proliferation index. In contrast to adult FL, malignant cells in pediatric-type FL lack aberrant BCL2 expression.

Most importantly, for pediatric-type FL, the prognosis is excellent with durable remissions after surgical excision, Dr. Louissaint said.

Follicular lymphoma: Molecular features by age

Because of the excellent prognosis in pediatric-type FL, it is important to assess whether young adults with FL have adult-type or pediatric-type lesions, Dr. Louissaint said.

He cited many studies showing differences in adult and pediatric-type FL. In adult FL, the mutational landscape is characterized by frequent chromatin-modifying mutations in genes such as CREBBP, KM22D, and EP300.

In contrast, in pediatric-type FL, there are frequent activating MAPK pathway mutations, including mutations in the negative regulatory domain of MAP2K1. These mutations are not seen in adult FL.

Dr. Louissaint noted that there may be mutations in epigenetic modifiers (CREBBP, TNFRSF14) in both adult and pediatric-type FL. However, CREBBP is very unusual in pediatric-type FL and common in adult FL. This suggests the alterations in pediatric-type FL do not simply represent an early stage of the same disease as adult FL.

Despite a high proliferating fraction and absence of BCL2/BCL6/IRF4 rearrangements in pediatric-type FL, the presence of these features was associated with dramatic difference in progression-free survival, according to research published in Blood in 2012.

A distinct entity

In 2016, the World Health Organization recognized pediatric-type FL as a distinct entity, with the following diagnostic criteria (published in Blood):

- At least partial effacement of nodal architecture, expansile follicles, intermediate-size blastoid cells, and no component of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- Immunohistochemistry showing BCL6 positivity, BCL2 negativity or weak positivity, and a high proliferative fraction.

- Genomic studies showing no BCL2 amplification.

- Clinical features of nodal disease in the head and neck region, early clinical stage, age younger than 40 years, typically in a male with no internal nodes involved.

When FL occurs in AYAs, the diagnostic findings of pediatric-type FL suggest the patient will do well with conservative management (e.g., excision alone), Dr. Louissaint noted.

Two sizes do not fit all

The strategies that have improved cancer outcomes since the 1970s for children and older adults have been much less successful for AYAs with cancer.

As an oncologic community, we should not allow the AYA gap to persist. As always, the solutions are likely to involve focused clinical research, education, and communication. Effort will need to be targeted specifically to the AYA population.

Since health-related mortality is high even when cancer-specific outcomes improve, adopting and maintaining a healthy lifestyle must be a key part of the discussion with these young patients.

The biologic differences associated with AYA lymphomas demand participation in clinical trials.

Oncologists should vigorously support removing impediments to the participation of AYAs in prospective clinical trials, stratified (but unrestricted) by age, with careful analysis of patient-reported outcomes, late adverse effects, and biospecimen collection.

As Dr. Kelly noted in the question-and-answer period, the Children’s Oncology Group has an existing biobank of paraffin-embedded tumor samples, DNA from lymphoma specimens, plasma, and sera with clinically annotated data that can be given to investigators upon request and justification.

Going beyond eligibility for clinical trials

Unfortunately, we will likely find that broadening eligibility criteria is the “low-hanging fruit.” There are protocol-, patient-, and physician-related obstacles, according to a review published in Cancer in 2019.

Patient-related obstacles include fear of toxicity, uncertainty about placebos, a steep learning curve for health literacy, insurance-related impediments, and other access-related issues.

Discussions will need to be tailored to the AYA population. Frank, early conversations about fertility, sexuality, financial hardship, career advancement, work-life balance, and cognitive risks may not only facilitate treatment planning but also encourage the trust that is essential for patients to enroll in trials.

The investment in time, multidisciplinary staff and physician involvement, and potential delays in treatment initiation may be painful and inconvenient, but the benefits for long-term health outcomes and personal-professional relationships will be gratifying beyond measure.

Dr. Smith disclosed relationships with Genentech/Roche, Celgene, TGTX, Karyopharm, Janssen, and Bantem. Dr. Roth disclosed relationships with Janssen, ADC Therapeutics, and Celgene. Dr. Kelly and Dr. Louissaint had no financial relationships to disclose.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM AACR ADVANCES IN MALIGNANT LYMPHOMA 2020

Cancer researchers cross over to COVID-19 clinical trials

When the first reports emerged of “cytokine storm” in patients with severe COVID-19, all eyes turned to cancer research. Oncologists have years of experience reigning in “cytokine release syndrome” (CRS) in patients treated with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) therapies for advanced blood cancers.

There was hope that drugs used to quell CRS in patients with cancer would be effective in patients with severe COVID. But the promise of a quick fix with oncology medications has yet to be fully realized.