User login

VTEs tied to immune checkpoint inhibitor cancer treatment

Cancer patients who receive an immune checkpoint inhibitor have more than a doubled rate of venous thromboembolism during the subsequent 2 years, compared with their rate during the 2 years before treatment, according to a retrospective analysis of more than 2,800 patients treated at a single U.S. center.

The study focused on cancer patients treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. It showed that during the 2 years prior to treatment with any type of ICI, the incidence of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) was 4.85/100 patient-years that then jumped to 11.75/100 patient-years during the 2 years following treatment. This translated into an incidence rate ratio of 2.43 during posttreatment follow-up, compared with pretreatment, Jingyi Gong, MD, said at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The increased VTE rate resulted from rises in both the rate of deep vein thrombosis, which had an IRR of 3.23 during the posttreatment period, and for pulmonary embolism, which showed an IRR of 2.24, said Dr. Gong, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She hypothesized that this effect may result from a procoagulant effect of the immune activation and inflammation triggered by ICIs.

Hypothesis-generating results

Cardiologists cautioned that these findings should only be considered hypothesis generating, but raise an important alert for clinicians to have heightened awareness of the potential for VTE following ICI treatment.

“A clear message is to be aware that there is this signal, and be vigilant for patients who might present with VTE following ICI treatment,” commented Richard J. Kovacs, MD, a cardiologist and professor at Indiana University, Indianapolis. The data that Dr. Gong reported are “moderately convincing,” he added in an interview.

“Awareness that patients who receive ICI may be at increased VTE risk is very important,” agreed Umberto Campia, MD, a cardiologist, vascular specialist, and member of the cardio-oncology group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was not involved in the new study.

The potential impact of ICI treatment on VTE risk is slowly emerging, added Dr. Campia. Until recently, the literature primarily was case reports, but recently another retrospective, single-center study came out that reported a 13% incidence of VTE in cancer patients following ICI treatment. On the other hand, a recently published meta-analysis of more than 20,000 patients from 68 ICI studies failed to find a suggestion of increased VTE incidence following ICI interventions.

Attempting to assess the impact of treatment on VTE risk in cancer patients is challenging because cancer itself boosts the risk. Recommendations on the use of VTE prophylaxis in cancer patients most recently came out in 2014 from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which said that VTE prophylaxis for ambulatory cancer patients “may be considered for highly select high-risk patients.” The impact of cancer therapy on VTE risk and the need for prophylaxis is usually assessed by applying the Khorana score, Dr. Campia said in an interview.

VTE spikes acutely after ICI treatment

Dr. Gong analyzed VTE incidence rates by time during the total 4-year period studied, and found that the rate gradually and steadily rose with time throughout the 2 years preceding treatment, spiked immediately following ICI treatment, and then gradually and steadily fell back to roughly the rate seen just before treatment, reaching that level about a year after treatment. She ran a sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who died during the first year following their ICI treatment, and in this calculation an acute spike in VTE following ICI treatment still occurred but with reduced magnitude.

She also reported the results of several subgroup analyses. The IRRs remained consistent among women and men, among patients who were aged over or under 65 years, and regardless of cancer type or treatment with corticosteroids. But the subgroup analyses identified two parameters that seemed to clearly split VTE rates.

Among patients on treatment with an anticoagulant agent at the time of their ICI treatment, roughly 10% of the patients, the IRR was 0.56, compared with a ratio of 3.86 among the other patients, suggesting possible protection. A second factor that seemed linked with VTE incidence was the number of ICI treatment cycles a patient received. Those who received more than five cycles had a risk ratio of 3.95, while those who received five or fewer cycles had a RR of 1.66.

Her analysis included 2,842 cancer patients who received treatment with an ICI at Massachusetts General Hospital. Patients averaged 64 years of age, slightly more than half were men, and 13% had a prior history of VTE. Patients received an average of 5 ICI treatment cycles, but a quarter of the patients received more than 10 cycles.

During the 2-year follow-up, 244 patients (9%) developed VTE. The patients who developed VTE were significantly younger than those who did not, with an average age of 63 years, compared with 65. And the patients who eventually developed VTE had a significantly higher prevalence of prior VTE at 18%, compared with 12% among the patients who stayed VTE free.

The cancer types patients had were non–small cell lung, 29%; melanoma, 28%; head and neck, 12%; renal genitourinary, 6%; and other, 25%. ICIs have been available for routine U.S. practice since 2011. The class includes agents such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and durvalumab (Imfinzi).

Researchers would need to perform a prospective, randomized study to determine whether anticoagulant prophylaxis is clearly beneficial for patients receiving ICI treatment, Dr. Gong said. But both Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Campia said that more data on this topic are first needed.

“We need to confirm that treatment with ICI is associated with VTEs. Retrospective data are not definitive,” said Dr. Campia. “We would need to prospectively assess the impact of ICI,” which will not be easy, as it’s quickly become a cornerstone for treating many cancers. “We need to become more familiar with the adverse effects of these drugs. We are still learning about their toxicities.”

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Gong, Dr. Kovacs, and Dr. Campia had no disclosures.

Cancer patients who receive an immune checkpoint inhibitor have more than a doubled rate of venous thromboembolism during the subsequent 2 years, compared with their rate during the 2 years before treatment, according to a retrospective analysis of more than 2,800 patients treated at a single U.S. center.

The study focused on cancer patients treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. It showed that during the 2 years prior to treatment with any type of ICI, the incidence of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) was 4.85/100 patient-years that then jumped to 11.75/100 patient-years during the 2 years following treatment. This translated into an incidence rate ratio of 2.43 during posttreatment follow-up, compared with pretreatment, Jingyi Gong, MD, said at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The increased VTE rate resulted from rises in both the rate of deep vein thrombosis, which had an IRR of 3.23 during the posttreatment period, and for pulmonary embolism, which showed an IRR of 2.24, said Dr. Gong, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She hypothesized that this effect may result from a procoagulant effect of the immune activation and inflammation triggered by ICIs.

Hypothesis-generating results

Cardiologists cautioned that these findings should only be considered hypothesis generating, but raise an important alert for clinicians to have heightened awareness of the potential for VTE following ICI treatment.

“A clear message is to be aware that there is this signal, and be vigilant for patients who might present with VTE following ICI treatment,” commented Richard J. Kovacs, MD, a cardiologist and professor at Indiana University, Indianapolis. The data that Dr. Gong reported are “moderately convincing,” he added in an interview.

“Awareness that patients who receive ICI may be at increased VTE risk is very important,” agreed Umberto Campia, MD, a cardiologist, vascular specialist, and member of the cardio-oncology group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was not involved in the new study.

The potential impact of ICI treatment on VTE risk is slowly emerging, added Dr. Campia. Until recently, the literature primarily was case reports, but recently another retrospective, single-center study came out that reported a 13% incidence of VTE in cancer patients following ICI treatment. On the other hand, a recently published meta-analysis of more than 20,000 patients from 68 ICI studies failed to find a suggestion of increased VTE incidence following ICI interventions.

Attempting to assess the impact of treatment on VTE risk in cancer patients is challenging because cancer itself boosts the risk. Recommendations on the use of VTE prophylaxis in cancer patients most recently came out in 2014 from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which said that VTE prophylaxis for ambulatory cancer patients “may be considered for highly select high-risk patients.” The impact of cancer therapy on VTE risk and the need for prophylaxis is usually assessed by applying the Khorana score, Dr. Campia said in an interview.

VTE spikes acutely after ICI treatment

Dr. Gong analyzed VTE incidence rates by time during the total 4-year period studied, and found that the rate gradually and steadily rose with time throughout the 2 years preceding treatment, spiked immediately following ICI treatment, and then gradually and steadily fell back to roughly the rate seen just before treatment, reaching that level about a year after treatment. She ran a sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who died during the first year following their ICI treatment, and in this calculation an acute spike in VTE following ICI treatment still occurred but with reduced magnitude.

She also reported the results of several subgroup analyses. The IRRs remained consistent among women and men, among patients who were aged over or under 65 years, and regardless of cancer type or treatment with corticosteroids. But the subgroup analyses identified two parameters that seemed to clearly split VTE rates.

Among patients on treatment with an anticoagulant agent at the time of their ICI treatment, roughly 10% of the patients, the IRR was 0.56, compared with a ratio of 3.86 among the other patients, suggesting possible protection. A second factor that seemed linked with VTE incidence was the number of ICI treatment cycles a patient received. Those who received more than five cycles had a risk ratio of 3.95, while those who received five or fewer cycles had a RR of 1.66.

Her analysis included 2,842 cancer patients who received treatment with an ICI at Massachusetts General Hospital. Patients averaged 64 years of age, slightly more than half were men, and 13% had a prior history of VTE. Patients received an average of 5 ICI treatment cycles, but a quarter of the patients received more than 10 cycles.

During the 2-year follow-up, 244 patients (9%) developed VTE. The patients who developed VTE were significantly younger than those who did not, with an average age of 63 years, compared with 65. And the patients who eventually developed VTE had a significantly higher prevalence of prior VTE at 18%, compared with 12% among the patients who stayed VTE free.

The cancer types patients had were non–small cell lung, 29%; melanoma, 28%; head and neck, 12%; renal genitourinary, 6%; and other, 25%. ICIs have been available for routine U.S. practice since 2011. The class includes agents such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and durvalumab (Imfinzi).

Researchers would need to perform a prospective, randomized study to determine whether anticoagulant prophylaxis is clearly beneficial for patients receiving ICI treatment, Dr. Gong said. But both Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Campia said that more data on this topic are first needed.

“We need to confirm that treatment with ICI is associated with VTEs. Retrospective data are not definitive,” said Dr. Campia. “We would need to prospectively assess the impact of ICI,” which will not be easy, as it’s quickly become a cornerstone for treating many cancers. “We need to become more familiar with the adverse effects of these drugs. We are still learning about their toxicities.”

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Gong, Dr. Kovacs, and Dr. Campia had no disclosures.

Cancer patients who receive an immune checkpoint inhibitor have more than a doubled rate of venous thromboembolism during the subsequent 2 years, compared with their rate during the 2 years before treatment, according to a retrospective analysis of more than 2,800 patients treated at a single U.S. center.

The study focused on cancer patients treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. It showed that during the 2 years prior to treatment with any type of ICI, the incidence of venous thromboembolic events (VTE) was 4.85/100 patient-years that then jumped to 11.75/100 patient-years during the 2 years following treatment. This translated into an incidence rate ratio of 2.43 during posttreatment follow-up, compared with pretreatment, Jingyi Gong, MD, said at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The increased VTE rate resulted from rises in both the rate of deep vein thrombosis, which had an IRR of 3.23 during the posttreatment period, and for pulmonary embolism, which showed an IRR of 2.24, said Dr. Gong, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She hypothesized that this effect may result from a procoagulant effect of the immune activation and inflammation triggered by ICIs.

Hypothesis-generating results

Cardiologists cautioned that these findings should only be considered hypothesis generating, but raise an important alert for clinicians to have heightened awareness of the potential for VTE following ICI treatment.

“A clear message is to be aware that there is this signal, and be vigilant for patients who might present with VTE following ICI treatment,” commented Richard J. Kovacs, MD, a cardiologist and professor at Indiana University, Indianapolis. The data that Dr. Gong reported are “moderately convincing,” he added in an interview.

“Awareness that patients who receive ICI may be at increased VTE risk is very important,” agreed Umberto Campia, MD, a cardiologist, vascular specialist, and member of the cardio-oncology group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was not involved in the new study.

The potential impact of ICI treatment on VTE risk is slowly emerging, added Dr. Campia. Until recently, the literature primarily was case reports, but recently another retrospective, single-center study came out that reported a 13% incidence of VTE in cancer patients following ICI treatment. On the other hand, a recently published meta-analysis of more than 20,000 patients from 68 ICI studies failed to find a suggestion of increased VTE incidence following ICI interventions.

Attempting to assess the impact of treatment on VTE risk in cancer patients is challenging because cancer itself boosts the risk. Recommendations on the use of VTE prophylaxis in cancer patients most recently came out in 2014 from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which said that VTE prophylaxis for ambulatory cancer patients “may be considered for highly select high-risk patients.” The impact of cancer therapy on VTE risk and the need for prophylaxis is usually assessed by applying the Khorana score, Dr. Campia said in an interview.

VTE spikes acutely after ICI treatment

Dr. Gong analyzed VTE incidence rates by time during the total 4-year period studied, and found that the rate gradually and steadily rose with time throughout the 2 years preceding treatment, spiked immediately following ICI treatment, and then gradually and steadily fell back to roughly the rate seen just before treatment, reaching that level about a year after treatment. She ran a sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who died during the first year following their ICI treatment, and in this calculation an acute spike in VTE following ICI treatment still occurred but with reduced magnitude.

She also reported the results of several subgroup analyses. The IRRs remained consistent among women and men, among patients who were aged over or under 65 years, and regardless of cancer type or treatment with corticosteroids. But the subgroup analyses identified two parameters that seemed to clearly split VTE rates.

Among patients on treatment with an anticoagulant agent at the time of their ICI treatment, roughly 10% of the patients, the IRR was 0.56, compared with a ratio of 3.86 among the other patients, suggesting possible protection. A second factor that seemed linked with VTE incidence was the number of ICI treatment cycles a patient received. Those who received more than five cycles had a risk ratio of 3.95, while those who received five or fewer cycles had a RR of 1.66.

Her analysis included 2,842 cancer patients who received treatment with an ICI at Massachusetts General Hospital. Patients averaged 64 years of age, slightly more than half were men, and 13% had a prior history of VTE. Patients received an average of 5 ICI treatment cycles, but a quarter of the patients received more than 10 cycles.

During the 2-year follow-up, 244 patients (9%) developed VTE. The patients who developed VTE were significantly younger than those who did not, with an average age of 63 years, compared with 65. And the patients who eventually developed VTE had a significantly higher prevalence of prior VTE at 18%, compared with 12% among the patients who stayed VTE free.

The cancer types patients had were non–small cell lung, 29%; melanoma, 28%; head and neck, 12%; renal genitourinary, 6%; and other, 25%. ICIs have been available for routine U.S. practice since 2011. The class includes agents such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and durvalumab (Imfinzi).

Researchers would need to perform a prospective, randomized study to determine whether anticoagulant prophylaxis is clearly beneficial for patients receiving ICI treatment, Dr. Gong said. But both Dr. Kovacs and Dr. Campia said that more data on this topic are first needed.

“We need to confirm that treatment with ICI is associated with VTEs. Retrospective data are not definitive,” said Dr. Campia. “We would need to prospectively assess the impact of ICI,” which will not be easy, as it’s quickly become a cornerstone for treating many cancers. “We need to become more familiar with the adverse effects of these drugs. We are still learning about their toxicities.”

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Gong, Dr. Kovacs, and Dr. Campia had no disclosures.

FROM AHA 2020

Using telehealth to deliver palliative care to cancer patients

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM ASCO QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM 2020

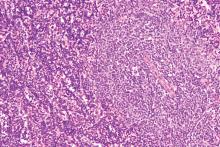

Home care for bortezomib safe and reduces hospital visits in myeloma patients

Home administration of bortezomib (Velcade), as a once or twice-weekly subcutaneous self-injection is safe in patients with myeloma, significantly reducing hospital visits, and likely improving quality of life, a study shows.

The majority (43 of 52 patients) successfully self-administered bortezomib and completed the course. Also, hospital visits for those on the so-called Homecare programme reduced by 50%, with most visits comprising a fortnightly drug pickup from the drive-through pharmacy.

The work was presented as a poster by lead author and researcher, Kanchana De Abrew, hematology consultant at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, at this year’s virtual British Society of Haematology (BSH) meeting. De Abrew conducted the study while at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth.

“We wanted to minimize patient visits to hospital because with travel time and waiting time, patients can easily find a visit takes up a whole morning, so this relates to their quality of life as well as having financial implications for patients,” Dr. De Abrew said in an interview. It also reduced the impact on day units and improved capacity for other services.

Dr. De Abrew noted that the study was conducted in the pre-COVID-19 era, but that the current enhanced threat of infection only served to reinforce the benefits of self-administration at home and avoiding unnecessary hospital visits.

“This project could easily be set up in other hospitals and some other centers have already contacted us about this. It might suit rural areas,” she added.

‘Safe and effective’

Dr. Matthew Jenner, consultant hematologist for University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, who was not involved in the study, remarked that the study demonstrated another way to deliver bortezomib outside of hospital in addition to home care services that require trained nurses to administer treatment. “With a modest amount of training of the patient and family, it is both a safe and effective way of delivering treatment. This reduces hospital visits for the patient and frees up much needed capacity for heavily stretched chemotherapy units, creating space for other newer treatments that require hospital attendance.

“It is of benefit all round to both the patients undertaking self-administration and those who benefit from improved capacity,” added Dr. Jenner.

Avoiding hospital visits

Myeloma patients are already immunosuppressed prior to treatment and then this worsens once on treatment. Once they are sitting in a clinic environment they are surrounded by similarly immunosuppressed patients, so their risk is heightened further.

Figures suggest myeloma cases are on the increase. Annually, the United Kingdom sees around 5,800 new cases of myeloma and incidence increased by a significant 32% between the periods of 1993-1995 and 2015-2017. These figures were reflected in the patient numbers at the Queen Alexandra Hospital where the study was carried out. Many patients receive bortezomib, which forms the backbone of four National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved regimens.

“Patients are living longer so in the early 2000s patients had a life expectancy of 2-3 years, whereas now patients live for around 5 years. Also, the scope and lines of treatments have increased a lot. Over 50% of patients are likely to have bortezomib at some point in their management,” explained Dr. De Abrew.

Bortezomib is given once or twice weekly as a subcutaneous injection, and this usually continues for approximately 6-8 months with four to six cycles. Administering the drug in hospital requires around a half-hour slot placing considerable burden on the hematology day unit resources, and this can adversely affect the patient experience with waiting times and the need for frequent hospital visits.

Patient or relatives taught to self-administer at home

In 2017, clinical nurse specialists taught suitable patients to self-administer bortezomib in the Homecare protocol. Patients collected a 2-week supply of the drug. The protocol aimed to improve patient quality of life by reducing hospital visits, and increasing capacity in the hematology day unit. Since the start of the programme in 2017, the majority (71) of myeloma patients at Portsmouth have been treated through the Homecare program.

Dr. De Abrew conducted a retrospective review of patients who received bortezomib between January and October 2019 aimed at determining the effectiveness of the Homecare programme. To this end, she measured the proportion able to commence the Homecare protocol; the proportion successful in completing treatment on the Homecare protocol; the amount of additional clinical nurse specialist time required to support the Homecare protocol; and the number of associated adverse incidents.

A total of 52 bortezomib-treated patients were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they were on a different combination of drugs that required hospital visits, or inpatient care for other reasons. Three patients ceased the drug – two because of toxicity, and one because of rapid progression. The average age of patients was 74 years, and 55.8% were using bortezomib as first-line, 36.5% second-line, and the remainder third-line or more.

The vast majority started the Homecare protocol (45/52), and 25 self-administered and 17 received a relative’s help. A total of 43 completed the self-administration protocol with two reverting to hospital assistance. Bortezomib was given for four to six cycles lasting around 6-8 months.

Clinical nurse specialists trained 38 patients for home care, with an average training time of 43 minutes. Two of these patients were considered unsuitable for self-administration. The remainder were trained by ward nurses or did not require training having received bortezomib previously.

A total of 20 patients required additional clinical nurse specialist time requiring an average of 55 minutes. Of those requiring additional support: Seven needed retraining; two needed the first dose delivered by a nurse specialist; two requested help from the hematology unit; and nine wanted general extra support – for example, help with injection site queries (usually administered to the abdominal area), reassurance during administration, syringe queries, administrative queries, and queries around spillages.

“Importantly, patients always have the phone number of the nurse specialist at hand. But most people managed okay, and even if they needed additional support they still got there,” remarked Dr. De Abrew.

In terms of adverse events, there were six in total. These included three reported spillages (with no harm caused), and three experienced injection site incidents (rash, pain). “We found a low number of reported adverse events,” she said.

Dr. De Abrew added that generally, many more medications were being converted to subcutaneous formulations in myeloma and other hematology conditions. “Perhaps these results could inform self-administration of other drugs. In hematology, we get so many new drugs come through every year, but we don’t get the increased resources to manage this in the day units. Broadening self-administration could really help with capacity as well as improve quality of life for the patients.

“These results show that it can be done!” she said.

Dr. De Abrew declared no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Jenner declared receiving honoraria from Janssen, which manufactures branded Velcade (bortezomib).

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Home administration of bortezomib (Velcade), as a once or twice-weekly subcutaneous self-injection is safe in patients with myeloma, significantly reducing hospital visits, and likely improving quality of life, a study shows.

The majority (43 of 52 patients) successfully self-administered bortezomib and completed the course. Also, hospital visits for those on the so-called Homecare programme reduced by 50%, with most visits comprising a fortnightly drug pickup from the drive-through pharmacy.

The work was presented as a poster by lead author and researcher, Kanchana De Abrew, hematology consultant at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, at this year’s virtual British Society of Haematology (BSH) meeting. De Abrew conducted the study while at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth.

“We wanted to minimize patient visits to hospital because with travel time and waiting time, patients can easily find a visit takes up a whole morning, so this relates to their quality of life as well as having financial implications for patients,” Dr. De Abrew said in an interview. It also reduced the impact on day units and improved capacity for other services.

Dr. De Abrew noted that the study was conducted in the pre-COVID-19 era, but that the current enhanced threat of infection only served to reinforce the benefits of self-administration at home and avoiding unnecessary hospital visits.

“This project could easily be set up in other hospitals and some other centers have already contacted us about this. It might suit rural areas,” she added.

‘Safe and effective’

Dr. Matthew Jenner, consultant hematologist for University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, who was not involved in the study, remarked that the study demonstrated another way to deliver bortezomib outside of hospital in addition to home care services that require trained nurses to administer treatment. “With a modest amount of training of the patient and family, it is both a safe and effective way of delivering treatment. This reduces hospital visits for the patient and frees up much needed capacity for heavily stretched chemotherapy units, creating space for other newer treatments that require hospital attendance.

“It is of benefit all round to both the patients undertaking self-administration and those who benefit from improved capacity,” added Dr. Jenner.

Avoiding hospital visits

Myeloma patients are already immunosuppressed prior to treatment and then this worsens once on treatment. Once they are sitting in a clinic environment they are surrounded by similarly immunosuppressed patients, so their risk is heightened further.

Figures suggest myeloma cases are on the increase. Annually, the United Kingdom sees around 5,800 new cases of myeloma and incidence increased by a significant 32% between the periods of 1993-1995 and 2015-2017. These figures were reflected in the patient numbers at the Queen Alexandra Hospital where the study was carried out. Many patients receive bortezomib, which forms the backbone of four National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved regimens.

“Patients are living longer so in the early 2000s patients had a life expectancy of 2-3 years, whereas now patients live for around 5 years. Also, the scope and lines of treatments have increased a lot. Over 50% of patients are likely to have bortezomib at some point in their management,” explained Dr. De Abrew.

Bortezomib is given once or twice weekly as a subcutaneous injection, and this usually continues for approximately 6-8 months with four to six cycles. Administering the drug in hospital requires around a half-hour slot placing considerable burden on the hematology day unit resources, and this can adversely affect the patient experience with waiting times and the need for frequent hospital visits.

Patient or relatives taught to self-administer at home

In 2017, clinical nurse specialists taught suitable patients to self-administer bortezomib in the Homecare protocol. Patients collected a 2-week supply of the drug. The protocol aimed to improve patient quality of life by reducing hospital visits, and increasing capacity in the hematology day unit. Since the start of the programme in 2017, the majority (71) of myeloma patients at Portsmouth have been treated through the Homecare program.

Dr. De Abrew conducted a retrospective review of patients who received bortezomib between January and October 2019 aimed at determining the effectiveness of the Homecare programme. To this end, she measured the proportion able to commence the Homecare protocol; the proportion successful in completing treatment on the Homecare protocol; the amount of additional clinical nurse specialist time required to support the Homecare protocol; and the number of associated adverse incidents.

A total of 52 bortezomib-treated patients were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they were on a different combination of drugs that required hospital visits, or inpatient care for other reasons. Three patients ceased the drug – two because of toxicity, and one because of rapid progression. The average age of patients was 74 years, and 55.8% were using bortezomib as first-line, 36.5% second-line, and the remainder third-line or more.

The vast majority started the Homecare protocol (45/52), and 25 self-administered and 17 received a relative’s help. A total of 43 completed the self-administration protocol with two reverting to hospital assistance. Bortezomib was given for four to six cycles lasting around 6-8 months.

Clinical nurse specialists trained 38 patients for home care, with an average training time of 43 minutes. Two of these patients were considered unsuitable for self-administration. The remainder were trained by ward nurses or did not require training having received bortezomib previously.

A total of 20 patients required additional clinical nurse specialist time requiring an average of 55 minutes. Of those requiring additional support: Seven needed retraining; two needed the first dose delivered by a nurse specialist; two requested help from the hematology unit; and nine wanted general extra support – for example, help with injection site queries (usually administered to the abdominal area), reassurance during administration, syringe queries, administrative queries, and queries around spillages.

“Importantly, patients always have the phone number of the nurse specialist at hand. But most people managed okay, and even if they needed additional support they still got there,” remarked Dr. De Abrew.

In terms of adverse events, there were six in total. These included three reported spillages (with no harm caused), and three experienced injection site incidents (rash, pain). “We found a low number of reported adverse events,” she said.

Dr. De Abrew added that generally, many more medications were being converted to subcutaneous formulations in myeloma and other hematology conditions. “Perhaps these results could inform self-administration of other drugs. In hematology, we get so many new drugs come through every year, but we don’t get the increased resources to manage this in the day units. Broadening self-administration could really help with capacity as well as improve quality of life for the patients.

“These results show that it can be done!” she said.

Dr. De Abrew declared no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Jenner declared receiving honoraria from Janssen, which manufactures branded Velcade (bortezomib).

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Home administration of bortezomib (Velcade), as a once or twice-weekly subcutaneous self-injection is safe in patients with myeloma, significantly reducing hospital visits, and likely improving quality of life, a study shows.

The majority (43 of 52 patients) successfully self-administered bortezomib and completed the course. Also, hospital visits for those on the so-called Homecare programme reduced by 50%, with most visits comprising a fortnightly drug pickup from the drive-through pharmacy.

The work was presented as a poster by lead author and researcher, Kanchana De Abrew, hematology consultant at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, at this year’s virtual British Society of Haematology (BSH) meeting. De Abrew conducted the study while at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth.

“We wanted to minimize patient visits to hospital because with travel time and waiting time, patients can easily find a visit takes up a whole morning, so this relates to their quality of life as well as having financial implications for patients,” Dr. De Abrew said in an interview. It also reduced the impact on day units and improved capacity for other services.

Dr. De Abrew noted that the study was conducted in the pre-COVID-19 era, but that the current enhanced threat of infection only served to reinforce the benefits of self-administration at home and avoiding unnecessary hospital visits.

“This project could easily be set up in other hospitals and some other centers have already contacted us about this. It might suit rural areas,” she added.

‘Safe and effective’

Dr. Matthew Jenner, consultant hematologist for University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, who was not involved in the study, remarked that the study demonstrated another way to deliver bortezomib outside of hospital in addition to home care services that require trained nurses to administer treatment. “With a modest amount of training of the patient and family, it is both a safe and effective way of delivering treatment. This reduces hospital visits for the patient and frees up much needed capacity for heavily stretched chemotherapy units, creating space for other newer treatments that require hospital attendance.

“It is of benefit all round to both the patients undertaking self-administration and those who benefit from improved capacity,” added Dr. Jenner.

Avoiding hospital visits

Myeloma patients are already immunosuppressed prior to treatment and then this worsens once on treatment. Once they are sitting in a clinic environment they are surrounded by similarly immunosuppressed patients, so their risk is heightened further.

Figures suggest myeloma cases are on the increase. Annually, the United Kingdom sees around 5,800 new cases of myeloma and incidence increased by a significant 32% between the periods of 1993-1995 and 2015-2017. These figures were reflected in the patient numbers at the Queen Alexandra Hospital where the study was carried out. Many patients receive bortezomib, which forms the backbone of four National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved regimens.

“Patients are living longer so in the early 2000s patients had a life expectancy of 2-3 years, whereas now patients live for around 5 years. Also, the scope and lines of treatments have increased a lot. Over 50% of patients are likely to have bortezomib at some point in their management,” explained Dr. De Abrew.

Bortezomib is given once or twice weekly as a subcutaneous injection, and this usually continues for approximately 6-8 months with four to six cycles. Administering the drug in hospital requires around a half-hour slot placing considerable burden on the hematology day unit resources, and this can adversely affect the patient experience with waiting times and the need for frequent hospital visits.

Patient or relatives taught to self-administer at home

In 2017, clinical nurse specialists taught suitable patients to self-administer bortezomib in the Homecare protocol. Patients collected a 2-week supply of the drug. The protocol aimed to improve patient quality of life by reducing hospital visits, and increasing capacity in the hematology day unit. Since the start of the programme in 2017, the majority (71) of myeloma patients at Portsmouth have been treated through the Homecare program.

Dr. De Abrew conducted a retrospective review of patients who received bortezomib between January and October 2019 aimed at determining the effectiveness of the Homecare programme. To this end, she measured the proportion able to commence the Homecare protocol; the proportion successful in completing treatment on the Homecare protocol; the amount of additional clinical nurse specialist time required to support the Homecare protocol; and the number of associated adverse incidents.

A total of 52 bortezomib-treated patients were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they were on a different combination of drugs that required hospital visits, or inpatient care for other reasons. Three patients ceased the drug – two because of toxicity, and one because of rapid progression. The average age of patients was 74 years, and 55.8% were using bortezomib as first-line, 36.5% second-line, and the remainder third-line or more.

The vast majority started the Homecare protocol (45/52), and 25 self-administered and 17 received a relative’s help. A total of 43 completed the self-administration protocol with two reverting to hospital assistance. Bortezomib was given for four to six cycles lasting around 6-8 months.

Clinical nurse specialists trained 38 patients for home care, with an average training time of 43 minutes. Two of these patients were considered unsuitable for self-administration. The remainder were trained by ward nurses or did not require training having received bortezomib previously.

A total of 20 patients required additional clinical nurse specialist time requiring an average of 55 minutes. Of those requiring additional support: Seven needed retraining; two needed the first dose delivered by a nurse specialist; two requested help from the hematology unit; and nine wanted general extra support – for example, help with injection site queries (usually administered to the abdominal area), reassurance during administration, syringe queries, administrative queries, and queries around spillages.

“Importantly, patients always have the phone number of the nurse specialist at hand. But most people managed okay, and even if they needed additional support they still got there,” remarked Dr. De Abrew.

In terms of adverse events, there were six in total. These included three reported spillages (with no harm caused), and three experienced injection site incidents (rash, pain). “We found a low number of reported adverse events,” she said.

Dr. De Abrew added that generally, many more medications were being converted to subcutaneous formulations in myeloma and other hematology conditions. “Perhaps these results could inform self-administration of other drugs. In hematology, we get so many new drugs come through every year, but we don’t get the increased resources to manage this in the day units. Broadening self-administration could really help with capacity as well as improve quality of life for the patients.

“These results show that it can be done!” she said.

Dr. De Abrew declared no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Jenner declared receiving honoraria from Janssen, which manufactures branded Velcade (bortezomib).

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

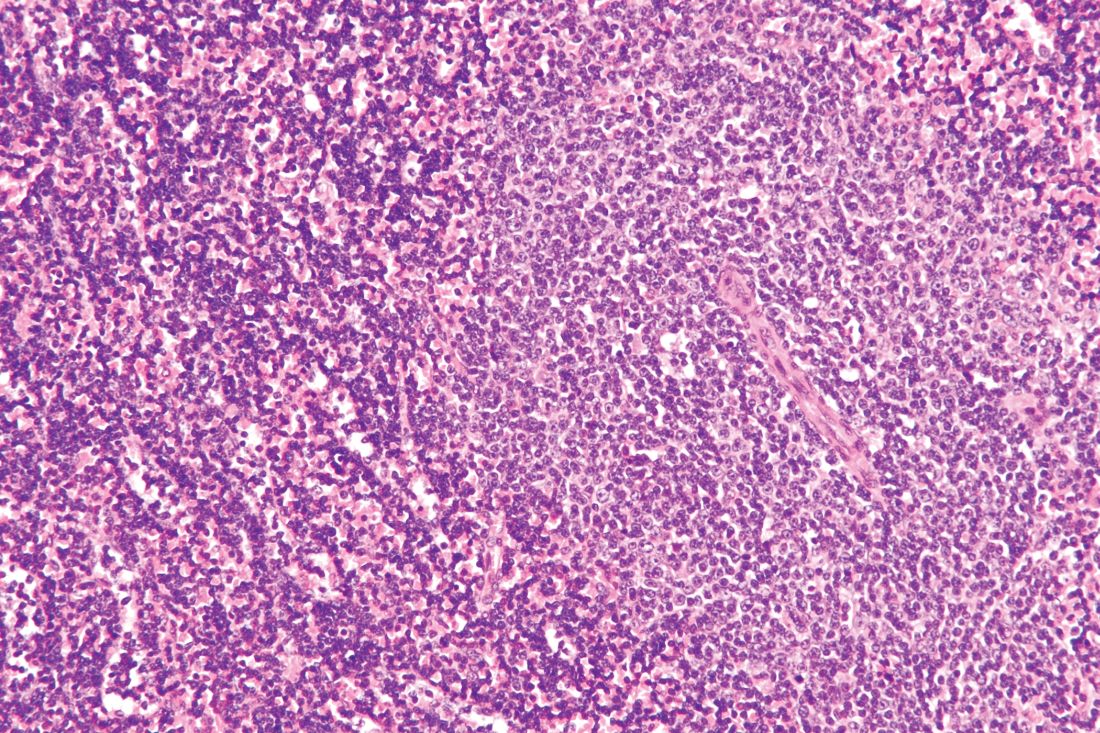

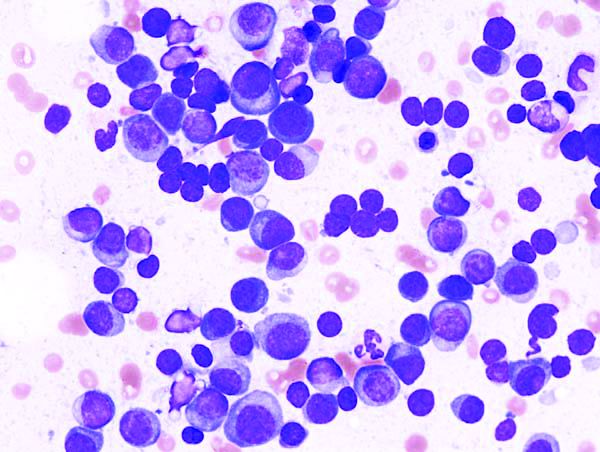

Ibrutinib associated with decreased circulating malignant cells and restored T-cell function in CLL patients

Ibrutinib showed significant impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and was found to restore healthy T-cell function in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to the results of a comparative study of CLL patients and healthy controls.

Researchers compared circulating counts of 21 immune blood cell subsets throughout the first year of treatment in 55 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL from the RESONATE trial and 50 previously untreated CLL patients from the RESONATE-2 trial with 20 untreated age-matched healthy donors, according to a report published online in Leukemia Research.

In addition, T-cell function was assessed in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation in 21 patients with R/R CLL, compared with 18 age-matched healthy donors, according to Isabelle G. Solman, MS, an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. and colleagues.

Positive indicators

Ibrutinib significantly decreased pathologically high circulating B cells, regulatory T cells, effector/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including exhausted and chronically activated T cells), natural killer (NK) T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; preserved naive T cells and NK cells; and increased circulating classical monocytes, according to the researchers.

Ibrutinib also significantly restored T-cell proliferative ability, degranulation, and cytokine secretion. Over the same period, ofatumumab or chlorambucil did not confer the same spectrum of normalization as ibrutinib in multiple immune subsets that were examined, they added.

“These results establish that ibrutinib has a significant and likely positive impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and restores healthy T-cell function,” the researchers indicated.

“Ibrutinib has a significant, progressively positive impact on both malignant and nonmalignant immune cells in CLL. These positive effects on circulating nonmalignant immune cells may contribute to long-term CLL disease control, overall health status, and decreased susceptibility to infection,” they concluded.

The study was funded by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie Company. Ms. Solman is an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. as were several other authors.

SOURCE: Solman IG et al. Leuk Res. 2020;97. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106432.

Ibrutinib showed significant impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and was found to restore healthy T-cell function in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to the results of a comparative study of CLL patients and healthy controls.

Researchers compared circulating counts of 21 immune blood cell subsets throughout the first year of treatment in 55 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL from the RESONATE trial and 50 previously untreated CLL patients from the RESONATE-2 trial with 20 untreated age-matched healthy donors, according to a report published online in Leukemia Research.

In addition, T-cell function was assessed in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation in 21 patients with R/R CLL, compared with 18 age-matched healthy donors, according to Isabelle G. Solman, MS, an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. and colleagues.

Positive indicators

Ibrutinib significantly decreased pathologically high circulating B cells, regulatory T cells, effector/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including exhausted and chronically activated T cells), natural killer (NK) T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; preserved naive T cells and NK cells; and increased circulating classical monocytes, according to the researchers.

Ibrutinib also significantly restored T-cell proliferative ability, degranulation, and cytokine secretion. Over the same period, ofatumumab or chlorambucil did not confer the same spectrum of normalization as ibrutinib in multiple immune subsets that were examined, they added.

“These results establish that ibrutinib has a significant and likely positive impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and restores healthy T-cell function,” the researchers indicated.

“Ibrutinib has a significant, progressively positive impact on both malignant and nonmalignant immune cells in CLL. These positive effects on circulating nonmalignant immune cells may contribute to long-term CLL disease control, overall health status, and decreased susceptibility to infection,” they concluded.

The study was funded by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie Company. Ms. Solman is an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. as were several other authors.

SOURCE: Solman IG et al. Leuk Res. 2020;97. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106432.

Ibrutinib showed significant impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and was found to restore healthy T-cell function in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to the results of a comparative study of CLL patients and healthy controls.

Researchers compared circulating counts of 21 immune blood cell subsets throughout the first year of treatment in 55 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL from the RESONATE trial and 50 previously untreated CLL patients from the RESONATE-2 trial with 20 untreated age-matched healthy donors, according to a report published online in Leukemia Research.

In addition, T-cell function was assessed in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation in 21 patients with R/R CLL, compared with 18 age-matched healthy donors, according to Isabelle G. Solman, MS, an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. and colleagues.

Positive indicators

Ibrutinib significantly decreased pathologically high circulating B cells, regulatory T cells, effector/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including exhausted and chronically activated T cells), natural killer (NK) T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; preserved naive T cells and NK cells; and increased circulating classical monocytes, according to the researchers.

Ibrutinib also significantly restored T-cell proliferative ability, degranulation, and cytokine secretion. Over the same period, ofatumumab or chlorambucil did not confer the same spectrum of normalization as ibrutinib in multiple immune subsets that were examined, they added.

“These results establish that ibrutinib has a significant and likely positive impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and restores healthy T-cell function,” the researchers indicated.

“Ibrutinib has a significant, progressively positive impact on both malignant and nonmalignant immune cells in CLL. These positive effects on circulating nonmalignant immune cells may contribute to long-term CLL disease control, overall health status, and decreased susceptibility to infection,” they concluded.

The study was funded by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie Company. Ms. Solman is an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. as were several other authors.

SOURCE: Solman IG et al. Leuk Res. 2020;97. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106432.

FROM LEUKEMIA RESEARCH

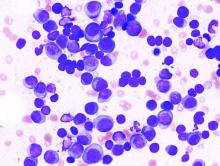

Beat AML: Precision medicine strategy feasible, superior to SOC for AML

The 30-day mortality rates were 3.7% versus 20.4% in 224 patients who enrolled in the Beat AML trial precision medicine substudies within 7 days of prospective genomic profiling and 103 who elected SOC chemotherapy, respectively, Amy Burd, PhD, vice president of research strategy for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Rye Brook, N.Y. and her colleagues reported online in Nature Medicine.

Overall survival (OS) at a median of 7.1 months was also significantly longer with precision medicine than with SOC chemotherapy (median, 12.8 vs. 3.9 months), the investigators found.

In an additional 28 patients who selected an investigational therapy rather than a precision medicine strategy or SOC chemotherapy, median OS was not reached, and in 38 who chose palliative care, median OS was 0.6 months, they noted. Care type was unknown in two patients.

The results were similar after controlling for demographic, clinical, and molecular variables and did not change when patients with adverse events of special interest were excluded from the analysis or when only those with survival greater than 2 weeks were included in the analysis.

AML confers an adverse outcome in older adults and therefore is typically treated rapidly after diagnosis. This has precluded consideration of patients’ mutational profile for treatment decisions.

Beat AML, however, sought to prospectively assess the feasibility of quickly ascertaining cytogenetic and mutational data for the purpose of improving outcomes through targeted treatment.

“The study shows that delaying treatment up to 7 days is feasible and safe, and that patients who opted for the precision medicine approach experienced a lower early death rate and superior overall survival, compared with patients who opted for standard of care,” lead study author John C. Byrd, MD, the D. Warren Brown Chair of Leukemia Research of the Ohio State University, Columbus, noted in a press statement from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which conducted the trial. “This patient-centric study shows that we can move away from chemotherapy treatment for patients who won’t respond or can’t withstand the harsh effects of the same chemotherapies we’ve been using for 40 years and match them with a treatment better suited for their individual cases.”

The ongoing Beat AML trial was launched by LLS in 2016 to assess various novel targeted therapies in newly diagnosed AML patients aged 60 years and older. Participants underwent next-generation genomic sequencing, were matched to the appropriate targeted therapy, and were given the option of enrolling on the relevant substudy or selecting an alternate treatment strategy. There are currently 11 substudies assessing novel therapies that have emerged in the wake of “significant progress in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of AML.”

The current findings represent outcomes in patients enrolled between Nov. 2016 and Jan. 2018. The patients had a mean age of 72 years, and those selecting precision medicine vs. SOC had similar demographic and genetic features, the authors noted.

LLS president and chief executive officer Louis J. DeGennaro, PhD, said the findings are practice changing and provide a template for studying precision medicine in other cancers.

“The study is changing significantly the way we look at treating patients with AML, showing that precision medicine ... can improve short- and long-term outcomes for patients with this deadly blood cancer,” he said in the LLS statement. “Further, BEAT AML has proven to be a viable model for other cancer clinical trials to emulate.”

In fact, the model has been applied to the recently launched Beat COVID trial, which looks at acalabrutinib in patients with hematologic cancers and COVID-19 infection, and other trials, including the LLS PedAL global precision medicine trial for children with relapsed acute leukemia, are planned.

“This study sets the path to establish the safety of precision medicine in AML and sets the stage to extend this same approach to younger patients with this disease and other cancers that are urgently treated as a single disease despite recognition of multiple subtypes, the authors concluded.

Dr. Burd is an employee of LLS, which received funding from AbbVie, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and a variety of other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Dr. Byrd has received research support from Acerta Pharma, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pharmacyclics and has served on the advisory board of Syndax Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Burd A et al. Nature Medicine 2020 Oct 26. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1089-8.

The 30-day mortality rates were 3.7% versus 20.4% in 224 patients who enrolled in the Beat AML trial precision medicine substudies within 7 days of prospective genomic profiling and 103 who elected SOC chemotherapy, respectively, Amy Burd, PhD, vice president of research strategy for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Rye Brook, N.Y. and her colleagues reported online in Nature Medicine.

Overall survival (OS) at a median of 7.1 months was also significantly longer with precision medicine than with SOC chemotherapy (median, 12.8 vs. 3.9 months), the investigators found.

In an additional 28 patients who selected an investigational therapy rather than a precision medicine strategy or SOC chemotherapy, median OS was not reached, and in 38 who chose palliative care, median OS was 0.6 months, they noted. Care type was unknown in two patients.

The results were similar after controlling for demographic, clinical, and molecular variables and did not change when patients with adverse events of special interest were excluded from the analysis or when only those with survival greater than 2 weeks were included in the analysis.

AML confers an adverse outcome in older adults and therefore is typically treated rapidly after diagnosis. This has precluded consideration of patients’ mutational profile for treatment decisions.

Beat AML, however, sought to prospectively assess the feasibility of quickly ascertaining cytogenetic and mutational data for the purpose of improving outcomes through targeted treatment.

“The study shows that delaying treatment up to 7 days is feasible and safe, and that patients who opted for the precision medicine approach experienced a lower early death rate and superior overall survival, compared with patients who opted for standard of care,” lead study author John C. Byrd, MD, the D. Warren Brown Chair of Leukemia Research of the Ohio State University, Columbus, noted in a press statement from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which conducted the trial. “This patient-centric study shows that we can move away from chemotherapy treatment for patients who won’t respond or can’t withstand the harsh effects of the same chemotherapies we’ve been using for 40 years and match them with a treatment better suited for their individual cases.”

The ongoing Beat AML trial was launched by LLS in 2016 to assess various novel targeted therapies in newly diagnosed AML patients aged 60 years and older. Participants underwent next-generation genomic sequencing, were matched to the appropriate targeted therapy, and were given the option of enrolling on the relevant substudy or selecting an alternate treatment strategy. There are currently 11 substudies assessing novel therapies that have emerged in the wake of “significant progress in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of AML.”

The current findings represent outcomes in patients enrolled between Nov. 2016 and Jan. 2018. The patients had a mean age of 72 years, and those selecting precision medicine vs. SOC had similar demographic and genetic features, the authors noted.