User login

Inflammation diminishes quality of life in NAFLD, not fibrosis

A variety of demographic and disease-related factors contribute to poorer quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), based on questionnaires involving 304 European patients.

In contrast with previous research, lobular inflammation, but not hepatic fibrosis, was associated with worse quality of life, reported to lead author Yvonne Huber, MD, of Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues. Women and those with advanced disease or comorbidities had the lowest health-related quality of life (HRQL) scores. The investigators suggested that these findings could be used for treatment planning at a population and patient level.

“With the emergence of medical therapy for [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)], it will be of importance to identify patients with the highest unmet need for treatment,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, emphasizing that therapies targeting inflammation could provide the greatest relief.

To determine which patients with NAFLD were most affected by their condition, the investigators used the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which assesses physical, mental, social, and emotional function, with lower scores indicating poorer health-related quality of life. “[The CLDQ] more specifically addresses symptoms of patients with chronic liver disease, including extrahepatic manifestations, compared with traditional HRQL measures such as the [Short Form–36 (SF-36)] Health Survey Questionnaire,” the investigators explained. Recent research has used the CLDQ to reveal a variety of findings, the investigators noted, such as a 2016 study by Alt and colleagues outlining the most common symptoms in noninfectious chronic liver disease (abdominal discomfort, fatigue, and anxiety), and two studies by Younossi and colleagues describing quality of life improvements after curing hepatitis C virus, and negative impacts of viremia and hepatic inflammation in patients with hepatitis B.

The current study involved 304 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD who were prospectively entered into the European NAFLD registry via centers in Germany (n = 133), the United Kingdom (n = 154), and Spain (n = 17). Patient data included demographic factors, laboratory findings, and histologic features. Within 6 months of liver biopsy, patients completed the CLDQ.

The mean patient age was 52.3 years, with slightly more men than women (53.3% vs. 46.7%). Most patients (75%) were obese, leading to a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2. More than two-thirds of patients (69.1%) had NASH, while approximately half of the population (51.4%) had moderate steatosis, no or low-grade fibrosis (F0-2, 58.2%), and no or low-grade lobular inflammation (grade 0 or 1, 54.7%). The three countries had significantly different population profiles; for example, the United Kingdom had an approximately 10% higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity compared with the entire cohort, but a decreased arterial hypertension rate of a similar magnitude. The United Kingdom also had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of the study population as a whole (4.73 vs. 4.99).

Analysis of the entire cohort revealed that a variety of demographic and disease-related factors negatively impacted health-related quality of life. Women had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of men (5.31 vs. 4.62; P less than .001), more often reporting abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, reduced activity, diminished emotional functioning, and worry. CLDQ overall score was negatively influenced by obesity (4.83 vs. 5.46), type 2 diabetes (4.74 vs. 5.25), and hyperlipidemia (4.84 vs. 5.24), but not hypertension. Laboratory findings that negatively correlated with CLDQ included aspartate transaminase (AST) and HbA1c, whereas ferritin was positively correlated.

Generally, patients with NASH reported worse quality of life than that of those with just NAFLD (4.85 vs. 5.31). Factors contributing most to this disparity were fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, and worry. On a histologic level, hepatic steatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation predicted poorer quality of life; although advanced fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis were associated with a trend toward reduced quality of life, this pattern lacked statistical significance. Multivariate analysis, which accounted for age, sex, body mass index, country, and type 2 diabetes, revealed independent associations between reduced quality of life and type 2 diabetes, sex, age, body mass index, and hepatic inflammation, but not fibrosis.

“The striking finding of the current analysis in this well-characterized European cohort was that, in contrast to the published data on predictors of overall and liver-specific mortality, lobular inflammation correlated independently with HRQL,” the investigators wrote. “These results differ from the NASH [Clinical Research Network] cohort, which found lower HRQL using the generic [SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire] in NASH compared with a healthy U.S. population and a significant effect in cirrhosis only.” The investigators suggested that mechanistic differences in disease progression could explain this discordance.

Although hepatic fibrosis has been tied with quality of life by some studies, the investigators pointed out that patients with chronic hepatitis B or C have reported improved quality of life after viral elimination or suppression, which reduce inflammation, but not fibrosis. “On the basis of the current analysis, it can be expected that improvement of steatohepatitis, and in particular lobular inflammation, will have measurable influence on HRQL even independently of fibrosis improvement,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by H2020. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Huber Y et al. CGH. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016.

A variety of demographic and disease-related factors contribute to poorer quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), based on questionnaires involving 304 European patients.

In contrast with previous research, lobular inflammation, but not hepatic fibrosis, was associated with worse quality of life, reported to lead author Yvonne Huber, MD, of Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues. Women and those with advanced disease or comorbidities had the lowest health-related quality of life (HRQL) scores. The investigators suggested that these findings could be used for treatment planning at a population and patient level.

“With the emergence of medical therapy for [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)], it will be of importance to identify patients with the highest unmet need for treatment,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, emphasizing that therapies targeting inflammation could provide the greatest relief.

To determine which patients with NAFLD were most affected by their condition, the investigators used the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which assesses physical, mental, social, and emotional function, with lower scores indicating poorer health-related quality of life. “[The CLDQ] more specifically addresses symptoms of patients with chronic liver disease, including extrahepatic manifestations, compared with traditional HRQL measures such as the [Short Form–36 (SF-36)] Health Survey Questionnaire,” the investigators explained. Recent research has used the CLDQ to reveal a variety of findings, the investigators noted, such as a 2016 study by Alt and colleagues outlining the most common symptoms in noninfectious chronic liver disease (abdominal discomfort, fatigue, and anxiety), and two studies by Younossi and colleagues describing quality of life improvements after curing hepatitis C virus, and negative impacts of viremia and hepatic inflammation in patients with hepatitis B.

The current study involved 304 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD who were prospectively entered into the European NAFLD registry via centers in Germany (n = 133), the United Kingdom (n = 154), and Spain (n = 17). Patient data included demographic factors, laboratory findings, and histologic features. Within 6 months of liver biopsy, patients completed the CLDQ.

The mean patient age was 52.3 years, with slightly more men than women (53.3% vs. 46.7%). Most patients (75%) were obese, leading to a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2. More than two-thirds of patients (69.1%) had NASH, while approximately half of the population (51.4%) had moderate steatosis, no or low-grade fibrosis (F0-2, 58.2%), and no or low-grade lobular inflammation (grade 0 or 1, 54.7%). The three countries had significantly different population profiles; for example, the United Kingdom had an approximately 10% higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity compared with the entire cohort, but a decreased arterial hypertension rate of a similar magnitude. The United Kingdom also had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of the study population as a whole (4.73 vs. 4.99).

Analysis of the entire cohort revealed that a variety of demographic and disease-related factors negatively impacted health-related quality of life. Women had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of men (5.31 vs. 4.62; P less than .001), more often reporting abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, reduced activity, diminished emotional functioning, and worry. CLDQ overall score was negatively influenced by obesity (4.83 vs. 5.46), type 2 diabetes (4.74 vs. 5.25), and hyperlipidemia (4.84 vs. 5.24), but not hypertension. Laboratory findings that negatively correlated with CLDQ included aspartate transaminase (AST) and HbA1c, whereas ferritin was positively correlated.

Generally, patients with NASH reported worse quality of life than that of those with just NAFLD (4.85 vs. 5.31). Factors contributing most to this disparity were fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, and worry. On a histologic level, hepatic steatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation predicted poorer quality of life; although advanced fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis were associated with a trend toward reduced quality of life, this pattern lacked statistical significance. Multivariate analysis, which accounted for age, sex, body mass index, country, and type 2 diabetes, revealed independent associations between reduced quality of life and type 2 diabetes, sex, age, body mass index, and hepatic inflammation, but not fibrosis.

“The striking finding of the current analysis in this well-characterized European cohort was that, in contrast to the published data on predictors of overall and liver-specific mortality, lobular inflammation correlated independently with HRQL,” the investigators wrote. “These results differ from the NASH [Clinical Research Network] cohort, which found lower HRQL using the generic [SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire] in NASH compared with a healthy U.S. population and a significant effect in cirrhosis only.” The investigators suggested that mechanistic differences in disease progression could explain this discordance.

Although hepatic fibrosis has been tied with quality of life by some studies, the investigators pointed out that patients with chronic hepatitis B or C have reported improved quality of life after viral elimination or suppression, which reduce inflammation, but not fibrosis. “On the basis of the current analysis, it can be expected that improvement of steatohepatitis, and in particular lobular inflammation, will have measurable influence on HRQL even independently of fibrosis improvement,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by H2020. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Huber Y et al. CGH. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016.

A variety of demographic and disease-related factors contribute to poorer quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), based on questionnaires involving 304 European patients.

In contrast with previous research, lobular inflammation, but not hepatic fibrosis, was associated with worse quality of life, reported to lead author Yvonne Huber, MD, of Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues. Women and those with advanced disease or comorbidities had the lowest health-related quality of life (HRQL) scores. The investigators suggested that these findings could be used for treatment planning at a population and patient level.

“With the emergence of medical therapy for [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)], it will be of importance to identify patients with the highest unmet need for treatment,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, emphasizing that therapies targeting inflammation could provide the greatest relief.

To determine which patients with NAFLD were most affected by their condition, the investigators used the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which assesses physical, mental, social, and emotional function, with lower scores indicating poorer health-related quality of life. “[The CLDQ] more specifically addresses symptoms of patients with chronic liver disease, including extrahepatic manifestations, compared with traditional HRQL measures such as the [Short Form–36 (SF-36)] Health Survey Questionnaire,” the investigators explained. Recent research has used the CLDQ to reveal a variety of findings, the investigators noted, such as a 2016 study by Alt and colleagues outlining the most common symptoms in noninfectious chronic liver disease (abdominal discomfort, fatigue, and anxiety), and two studies by Younossi and colleagues describing quality of life improvements after curing hepatitis C virus, and negative impacts of viremia and hepatic inflammation in patients with hepatitis B.

The current study involved 304 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD who were prospectively entered into the European NAFLD registry via centers in Germany (n = 133), the United Kingdom (n = 154), and Spain (n = 17). Patient data included demographic factors, laboratory findings, and histologic features. Within 6 months of liver biopsy, patients completed the CLDQ.

The mean patient age was 52.3 years, with slightly more men than women (53.3% vs. 46.7%). Most patients (75%) were obese, leading to a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2. More than two-thirds of patients (69.1%) had NASH, while approximately half of the population (51.4%) had moderate steatosis, no or low-grade fibrosis (F0-2, 58.2%), and no or low-grade lobular inflammation (grade 0 or 1, 54.7%). The three countries had significantly different population profiles; for example, the United Kingdom had an approximately 10% higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity compared with the entire cohort, but a decreased arterial hypertension rate of a similar magnitude. The United Kingdom also had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of the study population as a whole (4.73 vs. 4.99).

Analysis of the entire cohort revealed that a variety of demographic and disease-related factors negatively impacted health-related quality of life. Women had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of men (5.31 vs. 4.62; P less than .001), more often reporting abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, reduced activity, diminished emotional functioning, and worry. CLDQ overall score was negatively influenced by obesity (4.83 vs. 5.46), type 2 diabetes (4.74 vs. 5.25), and hyperlipidemia (4.84 vs. 5.24), but not hypertension. Laboratory findings that negatively correlated with CLDQ included aspartate transaminase (AST) and HbA1c, whereas ferritin was positively correlated.

Generally, patients with NASH reported worse quality of life than that of those with just NAFLD (4.85 vs. 5.31). Factors contributing most to this disparity were fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, and worry. On a histologic level, hepatic steatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation predicted poorer quality of life; although advanced fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis were associated with a trend toward reduced quality of life, this pattern lacked statistical significance. Multivariate analysis, which accounted for age, sex, body mass index, country, and type 2 diabetes, revealed independent associations between reduced quality of life and type 2 diabetes, sex, age, body mass index, and hepatic inflammation, but not fibrosis.

“The striking finding of the current analysis in this well-characterized European cohort was that, in contrast to the published data on predictors of overall and liver-specific mortality, lobular inflammation correlated independently with HRQL,” the investigators wrote. “These results differ from the NASH [Clinical Research Network] cohort, which found lower HRQL using the generic [SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire] in NASH compared with a healthy U.S. population and a significant effect in cirrhosis only.” The investigators suggested that mechanistic differences in disease progression could explain this discordance.

Although hepatic fibrosis has been tied with quality of life by some studies, the investigators pointed out that patients with chronic hepatitis B or C have reported improved quality of life after viral elimination or suppression, which reduce inflammation, but not fibrosis. “On the basis of the current analysis, it can be expected that improvement of steatohepatitis, and in particular lobular inflammation, will have measurable influence on HRQL even independently of fibrosis improvement,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by H2020. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Huber Y et al. CGH. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Spleen/liver stiffness ratio differentiates HCV, ALD

The spleen stiffness (SS) to liver stiffness (LS) ratio was significantly higher in patients with hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) than in patients with alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), according to the results of a multicenter prospective study. In addition, long-term outcome and complications differed dramatically between HCV and ALD. Variceal bleeding was the most common sign of decompensation and cause of death in patients with HCV, while jaundice was the most common sign of decompensation in patients with ALD.

Omar Elshaarawy, MSc, of the University of Heidelberg (Germany) and colleagues reported on their prospective study of 411 patients with HCV (220 patients) or ALD (191 patients) that were assessed for both LS and SS using the Fibroscan device. They also discussed their retrospective analysis of LS and spleen length (SL) from a separate, retrospective cohort of 449 patients (267 with HCV, 182 with ALD) for whom long-term data on decompensation/death were available.

The researchers found that SS was significantly higher in HCV patients, compared with those with ALD (42.0 vs. 32.6 kPa; P less than .0001), as was SL (15.6 vs. 11.9 cm, P less than .0001); this was despite a lower mean LS in HCV. As a result, the SS/LS ratio and the SL/LS ratio were both significantly higher in HCV (3.8 vs. 1.72 and 1.46 vs. 0.86, P less than .0001) through all fibrosis stages.

They also found that patients with ALD had higher LS values (30.5 vs. 21.3 kPa) and predominantly presented with jaundice (65.2%), with liver failure as the major cause of death (P less than .01). In contrast, in HCV, spleens were larger (17.6 vs. 12.1 cm) while variceal bleeding was the major cause of decompensation (73.2%) and death (P less than .001).

“We have demonstrated the disease-specific differences in SS/LS and SL/LS ratio between HCV and ALD. They underscore the role of the intrahepatic histological site of inflammation/fibrosis. We suggest that the SS/LS ratio could be used to confirm the disease etiology and predict disease-specific complications,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the Dietmar Hopp Foundation. The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Elshaarawy O et al. J Hepatol Reports. 2019 Jun 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.05.003.

The spleen stiffness (SS) to liver stiffness (LS) ratio was significantly higher in patients with hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) than in patients with alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), according to the results of a multicenter prospective study. In addition, long-term outcome and complications differed dramatically between HCV and ALD. Variceal bleeding was the most common sign of decompensation and cause of death in patients with HCV, while jaundice was the most common sign of decompensation in patients with ALD.

Omar Elshaarawy, MSc, of the University of Heidelberg (Germany) and colleagues reported on their prospective study of 411 patients with HCV (220 patients) or ALD (191 patients) that were assessed for both LS and SS using the Fibroscan device. They also discussed their retrospective analysis of LS and spleen length (SL) from a separate, retrospective cohort of 449 patients (267 with HCV, 182 with ALD) for whom long-term data on decompensation/death were available.

The researchers found that SS was significantly higher in HCV patients, compared with those with ALD (42.0 vs. 32.6 kPa; P less than .0001), as was SL (15.6 vs. 11.9 cm, P less than .0001); this was despite a lower mean LS in HCV. As a result, the SS/LS ratio and the SL/LS ratio were both significantly higher in HCV (3.8 vs. 1.72 and 1.46 vs. 0.86, P less than .0001) through all fibrosis stages.

They also found that patients with ALD had higher LS values (30.5 vs. 21.3 kPa) and predominantly presented with jaundice (65.2%), with liver failure as the major cause of death (P less than .01). In contrast, in HCV, spleens were larger (17.6 vs. 12.1 cm) while variceal bleeding was the major cause of decompensation (73.2%) and death (P less than .001).

“We have demonstrated the disease-specific differences in SS/LS and SL/LS ratio between HCV and ALD. They underscore the role of the intrahepatic histological site of inflammation/fibrosis. We suggest that the SS/LS ratio could be used to confirm the disease etiology and predict disease-specific complications,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the Dietmar Hopp Foundation. The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Elshaarawy O et al. J Hepatol Reports. 2019 Jun 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.05.003.

The spleen stiffness (SS) to liver stiffness (LS) ratio was significantly higher in patients with hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) than in patients with alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), according to the results of a multicenter prospective study. In addition, long-term outcome and complications differed dramatically between HCV and ALD. Variceal bleeding was the most common sign of decompensation and cause of death in patients with HCV, while jaundice was the most common sign of decompensation in patients with ALD.

Omar Elshaarawy, MSc, of the University of Heidelberg (Germany) and colleagues reported on their prospective study of 411 patients with HCV (220 patients) or ALD (191 patients) that were assessed for both LS and SS using the Fibroscan device. They also discussed their retrospective analysis of LS and spleen length (SL) from a separate, retrospective cohort of 449 patients (267 with HCV, 182 with ALD) for whom long-term data on decompensation/death were available.

The researchers found that SS was significantly higher in HCV patients, compared with those with ALD (42.0 vs. 32.6 kPa; P less than .0001), as was SL (15.6 vs. 11.9 cm, P less than .0001); this was despite a lower mean LS in HCV. As a result, the SS/LS ratio and the SL/LS ratio were both significantly higher in HCV (3.8 vs. 1.72 and 1.46 vs. 0.86, P less than .0001) through all fibrosis stages.

They also found that patients with ALD had higher LS values (30.5 vs. 21.3 kPa) and predominantly presented with jaundice (65.2%), with liver failure as the major cause of death (P less than .01). In contrast, in HCV, spleens were larger (17.6 vs. 12.1 cm) while variceal bleeding was the major cause of decompensation (73.2%) and death (P less than .001).

“We have demonstrated the disease-specific differences in SS/LS and SL/LS ratio between HCV and ALD. They underscore the role of the intrahepatic histological site of inflammation/fibrosis. We suggest that the SS/LS ratio could be used to confirm the disease etiology and predict disease-specific complications,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the Dietmar Hopp Foundation. The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Elshaarawy O et al. J Hepatol Reports. 2019 Jun 20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.05.003.

FROM JHEP REPORTS

HCC surveillance after anti-HCV therapy cost effective only for patients with cirrhosis

For patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)–related cirrhosis (F4), but not those with advanced fibrosis (F3), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance after a sustained virologic response (SVR) is cost effective, according to investigators.

Current international guidelines call for HCC surveillance among all patients with advanced fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis (F4) who have achieved SVR, but this is “very unlikely to be cost effective,” reported lead author Hooman Farhang Zangneh, MD, of Toronto General Hospital and colleagues. “HCV-related HCC rarely occurs in patients without cirrhosis,” the investigators explained in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “With cirrhosis present, HCC incidence is 1.4% to 4.9% per year. If found early, options for curative therapy include radiofrequency ablation (RFA), surgical resection, and liver transplantation.”

The investigators developed a Markov model to determine which at-risk patients could undergo surveillance while remaining below willingness-to-pay thresholds. Specifically, cost-effectiveness was assessed for ultrasound screenings annually (every year) or biannually (twice a year) among patients with advanced fibrosis (F3) or compensated cirrhosis (F4) who were aged 50 years and had an SVR. Relevant data were drawn from expert opinions, medical literature, and Canada Life Tables. Various HCC incidence rates were tested, including a constant annual rate, rates based on type of antiviral treatment (direct-acting and interferon-based therapies), others based on stage of fibrosis, and another that increased with age. The model was validated by applying it to patients with F3 or F4 fibrosis who had not yet achieved an SVR. All monetary values were reported in 2015 Canadian dollars.

Representative of current guidelines, the investigators first tested costs when conducting surveillance among all patients with F3 or F4 fibrosis with an assumed constant HCC annual incidence rate of 0.5%. Biannual ultrasound surveillance after SVR caught more cases of HCC still in a curable stage (78%) than no surveillance (29%); however, false-positives were relatively common at 21.8% and 15.7% for biannual and annual surveillance, respectively. The investigators noted that in the real world, some of these false-positives are not detected by more advanced imaging, so patients go on to receive unnecessary RFA, which incurs additional costs. Partly for this reason, while biannual surveillance was more effective, it was also more expensive, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $106,792 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), compared with $72,105 per QALY for annual surveillance.

Including only patients with F3 fibrosis after interferon-based therapy, using an HCC incidence of 0.23%, biannual and annual ICERs rose to $484,160 and $204,708 per QALY, respectively, both of which exceed standard willingness-to-pay thresholds. In comparison, annual and biannual ICERs were at most $55,850 and $42,305 per QALY, respectively, among patients with cirrhosis before interferon-induced SVR, using an HCC incidence rate of up to 1.39% per year.

“These results suggest that biannual (or annual) HCC surveillance is likely to be cost effective for patients with cirrhosis, but not for patients with F3 fibrosis before SVR,” the investigators wrote.

Costs for HCC surveillance among cirrhosis patients after direct-acting antiviral-induced SVR were still lower, at $43,229 and $34,307 per QALY, which were far lower than costs for patients with F3 fibrosis, which were $188,157 and $111,667 per QALY.

Focusing on the evident savings associated with surveillance of patients with cirrhosis, the investigators tested two diagnostic thresholds within this population with the aim of reducing costs further. They found that surveillance of patients with a pretreatment aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) greater than 2.0 (HCC incidence, 0.89%) was associated with biannual and annual ICERs of $48,729 and $37,806 per QALY, respectively, but when APRI was less than 2.0 (HCC incidence, 0.093%), surveillance was less effective and more expensive than no surveillance at all. A similar trend was found for an FIB-4 threshold of 3.25.

Employment of age-stratified risk of HCC also reduced costs of screening for patients with cirrhosis. With this strategy, ICER was $48,432 per QALY for biannual surveillance and $37,201 per QALY for annual surveillance.

“These data suggest that, if we assume HCC incidence increases with age, biannual or annual surveillance will be cost effective for the vast majority, if not all, patients with cirrhosis before SVR,” the investigators wrote.

“Our analysis suggests that HCC surveillance is very unlikely to be cost effective in patients with F3 fibrosis, whereas both annual and biannual modalities are likely to be cost effective at standard willingness-to-pay thresholds for patients with cirrhosis compared with no surveillance,” the investigators wrote.

“Additional long-term follow-up data are required to help identify patients at highest risk of HCC after SVR to tailor surveillance guidelines,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

This story was updated on 7/12/2019.

SOURCE: Zangneh et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.018.

For patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)–related cirrhosis (F4), but not those with advanced fibrosis (F3), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance after a sustained virologic response (SVR) is cost effective, according to investigators.

Current international guidelines call for HCC surveillance among all patients with advanced fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis (F4) who have achieved SVR, but this is “very unlikely to be cost effective,” reported lead author Hooman Farhang Zangneh, MD, of Toronto General Hospital and colleagues. “HCV-related HCC rarely occurs in patients without cirrhosis,” the investigators explained in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “With cirrhosis present, HCC incidence is 1.4% to 4.9% per year. If found early, options for curative therapy include radiofrequency ablation (RFA), surgical resection, and liver transplantation.”

The investigators developed a Markov model to determine which at-risk patients could undergo surveillance while remaining below willingness-to-pay thresholds. Specifically, cost-effectiveness was assessed for ultrasound screenings annually (every year) or biannually (twice a year) among patients with advanced fibrosis (F3) or compensated cirrhosis (F4) who were aged 50 years and had an SVR. Relevant data were drawn from expert opinions, medical literature, and Canada Life Tables. Various HCC incidence rates were tested, including a constant annual rate, rates based on type of antiviral treatment (direct-acting and interferon-based therapies), others based on stage of fibrosis, and another that increased with age. The model was validated by applying it to patients with F3 or F4 fibrosis who had not yet achieved an SVR. All monetary values were reported in 2015 Canadian dollars.

Representative of current guidelines, the investigators first tested costs when conducting surveillance among all patients with F3 or F4 fibrosis with an assumed constant HCC annual incidence rate of 0.5%. Biannual ultrasound surveillance after SVR caught more cases of HCC still in a curable stage (78%) than no surveillance (29%); however, false-positives were relatively common at 21.8% and 15.7% for biannual and annual surveillance, respectively. The investigators noted that in the real world, some of these false-positives are not detected by more advanced imaging, so patients go on to receive unnecessary RFA, which incurs additional costs. Partly for this reason, while biannual surveillance was more effective, it was also more expensive, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $106,792 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), compared with $72,105 per QALY for annual surveillance.

Including only patients with F3 fibrosis after interferon-based therapy, using an HCC incidence of 0.23%, biannual and annual ICERs rose to $484,160 and $204,708 per QALY, respectively, both of which exceed standard willingness-to-pay thresholds. In comparison, annual and biannual ICERs were at most $55,850 and $42,305 per QALY, respectively, among patients with cirrhosis before interferon-induced SVR, using an HCC incidence rate of up to 1.39% per year.

“These results suggest that biannual (or annual) HCC surveillance is likely to be cost effective for patients with cirrhosis, but not for patients with F3 fibrosis before SVR,” the investigators wrote.

Costs for HCC surveillance among cirrhosis patients after direct-acting antiviral-induced SVR were still lower, at $43,229 and $34,307 per QALY, which were far lower than costs for patients with F3 fibrosis, which were $188,157 and $111,667 per QALY.

Focusing on the evident savings associated with surveillance of patients with cirrhosis, the investigators tested two diagnostic thresholds within this population with the aim of reducing costs further. They found that surveillance of patients with a pretreatment aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) greater than 2.0 (HCC incidence, 0.89%) was associated with biannual and annual ICERs of $48,729 and $37,806 per QALY, respectively, but when APRI was less than 2.0 (HCC incidence, 0.093%), surveillance was less effective and more expensive than no surveillance at all. A similar trend was found for an FIB-4 threshold of 3.25.

Employment of age-stratified risk of HCC also reduced costs of screening for patients with cirrhosis. With this strategy, ICER was $48,432 per QALY for biannual surveillance and $37,201 per QALY for annual surveillance.

“These data suggest that, if we assume HCC incidence increases with age, biannual or annual surveillance will be cost effective for the vast majority, if not all, patients with cirrhosis before SVR,” the investigators wrote.

“Our analysis suggests that HCC surveillance is very unlikely to be cost effective in patients with F3 fibrosis, whereas both annual and biannual modalities are likely to be cost effective at standard willingness-to-pay thresholds for patients with cirrhosis compared with no surveillance,” the investigators wrote.

“Additional long-term follow-up data are required to help identify patients at highest risk of HCC after SVR to tailor surveillance guidelines,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

This story was updated on 7/12/2019.

SOURCE: Zangneh et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.018.

For patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)–related cirrhosis (F4), but not those with advanced fibrosis (F3), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance after a sustained virologic response (SVR) is cost effective, according to investigators.

Current international guidelines call for HCC surveillance among all patients with advanced fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis (F4) who have achieved SVR, but this is “very unlikely to be cost effective,” reported lead author Hooman Farhang Zangneh, MD, of Toronto General Hospital and colleagues. “HCV-related HCC rarely occurs in patients without cirrhosis,” the investigators explained in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “With cirrhosis present, HCC incidence is 1.4% to 4.9% per year. If found early, options for curative therapy include radiofrequency ablation (RFA), surgical resection, and liver transplantation.”

The investigators developed a Markov model to determine which at-risk patients could undergo surveillance while remaining below willingness-to-pay thresholds. Specifically, cost-effectiveness was assessed for ultrasound screenings annually (every year) or biannually (twice a year) among patients with advanced fibrosis (F3) or compensated cirrhosis (F4) who were aged 50 years and had an SVR. Relevant data were drawn from expert opinions, medical literature, and Canada Life Tables. Various HCC incidence rates were tested, including a constant annual rate, rates based on type of antiviral treatment (direct-acting and interferon-based therapies), others based on stage of fibrosis, and another that increased with age. The model was validated by applying it to patients with F3 or F4 fibrosis who had not yet achieved an SVR. All monetary values were reported in 2015 Canadian dollars.

Representative of current guidelines, the investigators first tested costs when conducting surveillance among all patients with F3 or F4 fibrosis with an assumed constant HCC annual incidence rate of 0.5%. Biannual ultrasound surveillance after SVR caught more cases of HCC still in a curable stage (78%) than no surveillance (29%); however, false-positives were relatively common at 21.8% and 15.7% for biannual and annual surveillance, respectively. The investigators noted that in the real world, some of these false-positives are not detected by more advanced imaging, so patients go on to receive unnecessary RFA, which incurs additional costs. Partly for this reason, while biannual surveillance was more effective, it was also more expensive, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $106,792 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), compared with $72,105 per QALY for annual surveillance.

Including only patients with F3 fibrosis after interferon-based therapy, using an HCC incidence of 0.23%, biannual and annual ICERs rose to $484,160 and $204,708 per QALY, respectively, both of which exceed standard willingness-to-pay thresholds. In comparison, annual and biannual ICERs were at most $55,850 and $42,305 per QALY, respectively, among patients with cirrhosis before interferon-induced SVR, using an HCC incidence rate of up to 1.39% per year.

“These results suggest that biannual (or annual) HCC surveillance is likely to be cost effective for patients with cirrhosis, but not for patients with F3 fibrosis before SVR,” the investigators wrote.

Costs for HCC surveillance among cirrhosis patients after direct-acting antiviral-induced SVR were still lower, at $43,229 and $34,307 per QALY, which were far lower than costs for patients with F3 fibrosis, which were $188,157 and $111,667 per QALY.

Focusing on the evident savings associated with surveillance of patients with cirrhosis, the investigators tested two diagnostic thresholds within this population with the aim of reducing costs further. They found that surveillance of patients with a pretreatment aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) greater than 2.0 (HCC incidence, 0.89%) was associated with biannual and annual ICERs of $48,729 and $37,806 per QALY, respectively, but when APRI was less than 2.0 (HCC incidence, 0.093%), surveillance was less effective and more expensive than no surveillance at all. A similar trend was found for an FIB-4 threshold of 3.25.

Employment of age-stratified risk of HCC also reduced costs of screening for patients with cirrhosis. With this strategy, ICER was $48,432 per QALY for biannual surveillance and $37,201 per QALY for annual surveillance.

“These data suggest that, if we assume HCC incidence increases with age, biannual or annual surveillance will be cost effective for the vast majority, if not all, patients with cirrhosis before SVR,” the investigators wrote.

“Our analysis suggests that HCC surveillance is very unlikely to be cost effective in patients with F3 fibrosis, whereas both annual and biannual modalities are likely to be cost effective at standard willingness-to-pay thresholds for patients with cirrhosis compared with no surveillance,” the investigators wrote.

“Additional long-term follow-up data are required to help identify patients at highest risk of HCC after SVR to tailor surveillance guidelines,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

This story was updated on 7/12/2019.

SOURCE: Zangneh et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.018.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Louisiana HCV program cuts costs – and hassles

Beginning July 15, physicians will no longer have to seek prior authorization or preauthorization to prescribe the authorized generic version of Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) to any Medicaid patient with hepatitis C. There will be no forms to file.

The change comes as part of a supplemental rebate agreement approved June 26 by CMS. That same day, Louisiana announced a deal with Asegua Therapeutics, a wholly owned subsidiary of Epclusa maker Gilead, that essentially caps the annual cost to the state for treating hepatitis C in incarcerated patients and Medicaid recipients.

State officials estimate about 39,000 Louisianans fit those criteria; the goal of the program is to cure at least 31,000 of them by the time the 5-year agreement expires.

“This new model has the potential to save many lives and improve the health of our citizens,” Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) said in a statement. “Asegua was willing to come to the table to work with us to help Louisiana residents and we are pleased to initiate this 5-year partnership. Ultimately our goal is to eliminate this disease in Louisiana, and we have taken a big step forward in that effort.”

The agreement was designed to change very little in terms of the mechanics of how Medicaid managed care organizations, which cover most of the state’s Medicaid population and handle coverage and claims. The biggest change is that, when a spending cap is reached, Asegua will rebate 100% excess costs to the state. Louisiana officials did not disclose what the annual financial caps were as part of the agreement.

“We really thought it was important to leave the system – as much as possible – intact because we think that is going to make us most successful,” Alex Billioux, MD, of the Louisiana Department of Health said in an interview. “We think it leverages existing patient relationships and existing [Medicaid managed care organization] care management responsibilities.”

He added that, by keeping current processes unchanged, “it takes what is an otherwise very complicated arrangement with the state and makes it a little simpler.”

Patients will see no change in terms of copayments for the approved generic topping out at $3 depending on income level as they would have prior to the agreement. The biggest difference for them is that “people who couldn’t be treated are now going to have access to those prescriptions,” Dr. Billioux said.

Some cautious optimism surrounds this kind of arrangement and the potential effect it can have on the affected population.

“Innovation geared to improve access to hepatitis C treatment is critical, particularly in areas like Louisiana where treatment rates for Medicaid patients have been very low,” Robert Brown, MD, member of the American Liver Foundation’s National Medical Advisory Committee and hepatologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said. “If we can enhance patient access to treatment, we know we will improve health outcomes. However, it is too early to tell if this innovation will be a success. At the end of the day, the number of additional patients cured will determine if this was the right approach.”

Beginning July 15, physicians will no longer have to seek prior authorization or preauthorization to prescribe the authorized generic version of Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) to any Medicaid patient with hepatitis C. There will be no forms to file.

The change comes as part of a supplemental rebate agreement approved June 26 by CMS. That same day, Louisiana announced a deal with Asegua Therapeutics, a wholly owned subsidiary of Epclusa maker Gilead, that essentially caps the annual cost to the state for treating hepatitis C in incarcerated patients and Medicaid recipients.

State officials estimate about 39,000 Louisianans fit those criteria; the goal of the program is to cure at least 31,000 of them by the time the 5-year agreement expires.

“This new model has the potential to save many lives and improve the health of our citizens,” Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) said in a statement. “Asegua was willing to come to the table to work with us to help Louisiana residents and we are pleased to initiate this 5-year partnership. Ultimately our goal is to eliminate this disease in Louisiana, and we have taken a big step forward in that effort.”

The agreement was designed to change very little in terms of the mechanics of how Medicaid managed care organizations, which cover most of the state’s Medicaid population and handle coverage and claims. The biggest change is that, when a spending cap is reached, Asegua will rebate 100% excess costs to the state. Louisiana officials did not disclose what the annual financial caps were as part of the agreement.

“We really thought it was important to leave the system – as much as possible – intact because we think that is going to make us most successful,” Alex Billioux, MD, of the Louisiana Department of Health said in an interview. “We think it leverages existing patient relationships and existing [Medicaid managed care organization] care management responsibilities.”

He added that, by keeping current processes unchanged, “it takes what is an otherwise very complicated arrangement with the state and makes it a little simpler.”

Patients will see no change in terms of copayments for the approved generic topping out at $3 depending on income level as they would have prior to the agreement. The biggest difference for them is that “people who couldn’t be treated are now going to have access to those prescriptions,” Dr. Billioux said.

Some cautious optimism surrounds this kind of arrangement and the potential effect it can have on the affected population.

“Innovation geared to improve access to hepatitis C treatment is critical, particularly in areas like Louisiana where treatment rates for Medicaid patients have been very low,” Robert Brown, MD, member of the American Liver Foundation’s National Medical Advisory Committee and hepatologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said. “If we can enhance patient access to treatment, we know we will improve health outcomes. However, it is too early to tell if this innovation will be a success. At the end of the day, the number of additional patients cured will determine if this was the right approach.”

Beginning July 15, physicians will no longer have to seek prior authorization or preauthorization to prescribe the authorized generic version of Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) to any Medicaid patient with hepatitis C. There will be no forms to file.

The change comes as part of a supplemental rebate agreement approved June 26 by CMS. That same day, Louisiana announced a deal with Asegua Therapeutics, a wholly owned subsidiary of Epclusa maker Gilead, that essentially caps the annual cost to the state for treating hepatitis C in incarcerated patients and Medicaid recipients.

State officials estimate about 39,000 Louisianans fit those criteria; the goal of the program is to cure at least 31,000 of them by the time the 5-year agreement expires.

“This new model has the potential to save many lives and improve the health of our citizens,” Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) said in a statement. “Asegua was willing to come to the table to work with us to help Louisiana residents and we are pleased to initiate this 5-year partnership. Ultimately our goal is to eliminate this disease in Louisiana, and we have taken a big step forward in that effort.”

The agreement was designed to change very little in terms of the mechanics of how Medicaid managed care organizations, which cover most of the state’s Medicaid population and handle coverage and claims. The biggest change is that, when a spending cap is reached, Asegua will rebate 100% excess costs to the state. Louisiana officials did not disclose what the annual financial caps were as part of the agreement.

“We really thought it was important to leave the system – as much as possible – intact because we think that is going to make us most successful,” Alex Billioux, MD, of the Louisiana Department of Health said in an interview. “We think it leverages existing patient relationships and existing [Medicaid managed care organization] care management responsibilities.”

He added that, by keeping current processes unchanged, “it takes what is an otherwise very complicated arrangement with the state and makes it a little simpler.”

Patients will see no change in terms of copayments for the approved generic topping out at $3 depending on income level as they would have prior to the agreement. The biggest difference for them is that “people who couldn’t be treated are now going to have access to those prescriptions,” Dr. Billioux said.

Some cautious optimism surrounds this kind of arrangement and the potential effect it can have on the affected population.

“Innovation geared to improve access to hepatitis C treatment is critical, particularly in areas like Louisiana where treatment rates for Medicaid patients have been very low,” Robert Brown, MD, member of the American Liver Foundation’s National Medical Advisory Committee and hepatologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, said. “If we can enhance patient access to treatment, we know we will improve health outcomes. However, it is too early to tell if this innovation will be a success. At the end of the day, the number of additional patients cured will determine if this was the right approach.”

Formal weight loss programs improve NAFLD

For patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), formal weight loss programs lead to statistically and clinically significant improvements in biomarkers of liver disease, based on a recent meta-analysis.

The findings support changing NAFLD guidelines to recommend weight loss interventions, according to lead author Dimitrios A. Koutoukidis, PhD, of the University of Oxford, UK, and colleagues. “Clinical guidelines around the world recommend physicians offer advice on lifestyle modification, which mostly includes weight loss through hypoenergetic diets and increased physical activity,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine. “However, whether clinicians provide advice and the type of advice they give vary greatly, and guidelines rarely specifically recommend treatment programs to support weight loss,” they added.

To investigate associations between methods of weight loss and improvements in NAFLD, the investigators screened for studies involving behavioral weight loss programs, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery, alone or in combination. To limit confounding, studies combining weight loss with other potential treatments, such as medications, were excluded. Weight loss interventions were compared to liver disease outcomes associated with lower-intensity weight loss intervention or none or minimal weight loss support, using at least 1 reported biomarker of liver disease. The literature search returned 22 eligible studies involving 2,588 patients.

The investigators found that more intensive weight loss programs were associated with greater weight loss than lower intensity methods (-3.61 kg; I2 = 95%). Multiple biomarkers of liver disease showed significant improvements in association with formal weight loss programs, including histologically or radiologically measured liver steatosis (standardized mean difference: -1.48; I2 = 94%), histologic NAFLD activity score (-0.92; I2= 95%), presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (OR, 0.14; I2 =0%), alanine aminotransferase (-9.81 U/L; I2= 97%), aspartate transaminase (-4.84 U/L; I2 = 96%), alkaline phosphatase (-5.53 U/L; I2 = 96%), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (-4.35 U/L; I2 = 92%). Weight loss interventions were not significantly associated with histologic liver fibrosis or inflammation, the investigators noted.

“The advantages [of weight loss interventions] seem to be greater in people who are overweight and with NAFLD, but our exploratory results suggest that weight loss interventions might still be beneficial in the minority of people with healthy weight and NAFLD,” the investigators wrote. “Clinicians may use these findings to counsel people with NAFLD on the expected clinically significant improvements in liver biomarkers after weight loss and direct the patients toward valuable interventions.”

“The accumulated evidence supports changing the clinical guidelines and routine practice to recommend formal weight loss programs to treat people with NAFLD,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and the Oxford NIHR Collaboration and Leadership in Applied Health Research. The investigators reported grants for other research from Cambridge Weight Plan.

SOURCE: Koutoukidis et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2248.

Past studies have attempted to investigate the relationship between weight loss and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), but they did so with various interventions and outcomes measures. Fortunately, the study by Dr. Koutoukidis and colleagues helps clear up this variability with a well-conducted systematic review. The results offer a convincing case that formal weight loss programs should be a cornerstone of NALFD treatment, based on improvements in blood, histologic, and radiologic biomarkers of liver disease. Since pharmacologic options for NAFLD are limited, these findings are particularly important.

Although the study did not reveal improvements in fibrosis or inflammation with weight loss, this is likely due to the scarcity of trials with histologic measures or long-term follow-up. Where long-term follow-up was available, weight loss was not maintained, disallowing clear conclusions. Still, other studies have shown that sustained weight loss is associated with improvements in fibrosis and mortality, so clinicians should feel encouraged that formal weight loss programs for patients with NAFLD likely have life-saving consequences.

Elizabeth Adler, MD and Danielle Brandman, MD , are with the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Brandman reported financial affiliations with Conatus, Gilead, and Allergan. Their remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2244 ).

Past studies have attempted to investigate the relationship between weight loss and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), but they did so with various interventions and outcomes measures. Fortunately, the study by Dr. Koutoukidis and colleagues helps clear up this variability with a well-conducted systematic review. The results offer a convincing case that formal weight loss programs should be a cornerstone of NALFD treatment, based on improvements in blood, histologic, and radiologic biomarkers of liver disease. Since pharmacologic options for NAFLD are limited, these findings are particularly important.

Although the study did not reveal improvements in fibrosis or inflammation with weight loss, this is likely due to the scarcity of trials with histologic measures or long-term follow-up. Where long-term follow-up was available, weight loss was not maintained, disallowing clear conclusions. Still, other studies have shown that sustained weight loss is associated with improvements in fibrosis and mortality, so clinicians should feel encouraged that formal weight loss programs for patients with NAFLD likely have life-saving consequences.

Elizabeth Adler, MD and Danielle Brandman, MD , are with the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Brandman reported financial affiliations with Conatus, Gilead, and Allergan. Their remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2244 ).

Past studies have attempted to investigate the relationship between weight loss and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), but they did so with various interventions and outcomes measures. Fortunately, the study by Dr. Koutoukidis and colleagues helps clear up this variability with a well-conducted systematic review. The results offer a convincing case that formal weight loss programs should be a cornerstone of NALFD treatment, based on improvements in blood, histologic, and radiologic biomarkers of liver disease. Since pharmacologic options for NAFLD are limited, these findings are particularly important.

Although the study did not reveal improvements in fibrosis or inflammation with weight loss, this is likely due to the scarcity of trials with histologic measures or long-term follow-up. Where long-term follow-up was available, weight loss was not maintained, disallowing clear conclusions. Still, other studies have shown that sustained weight loss is associated with improvements in fibrosis and mortality, so clinicians should feel encouraged that formal weight loss programs for patients with NAFLD likely have life-saving consequences.

Elizabeth Adler, MD and Danielle Brandman, MD , are with the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Brandman reported financial affiliations with Conatus, Gilead, and Allergan. Their remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2244 ).

For patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), formal weight loss programs lead to statistically and clinically significant improvements in biomarkers of liver disease, based on a recent meta-analysis.

The findings support changing NAFLD guidelines to recommend weight loss interventions, according to lead author Dimitrios A. Koutoukidis, PhD, of the University of Oxford, UK, and colleagues. “Clinical guidelines around the world recommend physicians offer advice on lifestyle modification, which mostly includes weight loss through hypoenergetic diets and increased physical activity,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine. “However, whether clinicians provide advice and the type of advice they give vary greatly, and guidelines rarely specifically recommend treatment programs to support weight loss,” they added.

To investigate associations between methods of weight loss and improvements in NAFLD, the investigators screened for studies involving behavioral weight loss programs, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery, alone or in combination. To limit confounding, studies combining weight loss with other potential treatments, such as medications, were excluded. Weight loss interventions were compared to liver disease outcomes associated with lower-intensity weight loss intervention or none or minimal weight loss support, using at least 1 reported biomarker of liver disease. The literature search returned 22 eligible studies involving 2,588 patients.

The investigators found that more intensive weight loss programs were associated with greater weight loss than lower intensity methods (-3.61 kg; I2 = 95%). Multiple biomarkers of liver disease showed significant improvements in association with formal weight loss programs, including histologically or radiologically measured liver steatosis (standardized mean difference: -1.48; I2 = 94%), histologic NAFLD activity score (-0.92; I2= 95%), presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (OR, 0.14; I2 =0%), alanine aminotransferase (-9.81 U/L; I2= 97%), aspartate transaminase (-4.84 U/L; I2 = 96%), alkaline phosphatase (-5.53 U/L; I2 = 96%), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (-4.35 U/L; I2 = 92%). Weight loss interventions were not significantly associated with histologic liver fibrosis or inflammation, the investigators noted.

“The advantages [of weight loss interventions] seem to be greater in people who are overweight and with NAFLD, but our exploratory results suggest that weight loss interventions might still be beneficial in the minority of people with healthy weight and NAFLD,” the investigators wrote. “Clinicians may use these findings to counsel people with NAFLD on the expected clinically significant improvements in liver biomarkers after weight loss and direct the patients toward valuable interventions.”

“The accumulated evidence supports changing the clinical guidelines and routine practice to recommend formal weight loss programs to treat people with NAFLD,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and the Oxford NIHR Collaboration and Leadership in Applied Health Research. The investigators reported grants for other research from Cambridge Weight Plan.

SOURCE: Koutoukidis et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2248.

For patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), formal weight loss programs lead to statistically and clinically significant improvements in biomarkers of liver disease, based on a recent meta-analysis.

The findings support changing NAFLD guidelines to recommend weight loss interventions, according to lead author Dimitrios A. Koutoukidis, PhD, of the University of Oxford, UK, and colleagues. “Clinical guidelines around the world recommend physicians offer advice on lifestyle modification, which mostly includes weight loss through hypoenergetic diets and increased physical activity,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine. “However, whether clinicians provide advice and the type of advice they give vary greatly, and guidelines rarely specifically recommend treatment programs to support weight loss,” they added.

To investigate associations between methods of weight loss and improvements in NAFLD, the investigators screened for studies involving behavioral weight loss programs, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery, alone or in combination. To limit confounding, studies combining weight loss with other potential treatments, such as medications, were excluded. Weight loss interventions were compared to liver disease outcomes associated with lower-intensity weight loss intervention or none or minimal weight loss support, using at least 1 reported biomarker of liver disease. The literature search returned 22 eligible studies involving 2,588 patients.

The investigators found that more intensive weight loss programs were associated with greater weight loss than lower intensity methods (-3.61 kg; I2 = 95%). Multiple biomarkers of liver disease showed significant improvements in association with formal weight loss programs, including histologically or radiologically measured liver steatosis (standardized mean difference: -1.48; I2 = 94%), histologic NAFLD activity score (-0.92; I2= 95%), presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (OR, 0.14; I2 =0%), alanine aminotransferase (-9.81 U/L; I2= 97%), aspartate transaminase (-4.84 U/L; I2 = 96%), alkaline phosphatase (-5.53 U/L; I2 = 96%), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (-4.35 U/L; I2 = 92%). Weight loss interventions were not significantly associated with histologic liver fibrosis or inflammation, the investigators noted.

“The advantages [of weight loss interventions] seem to be greater in people who are overweight and with NAFLD, but our exploratory results suggest that weight loss interventions might still be beneficial in the minority of people with healthy weight and NAFLD,” the investigators wrote. “Clinicians may use these findings to counsel people with NAFLD on the expected clinically significant improvements in liver biomarkers after weight loss and direct the patients toward valuable interventions.”

“The accumulated evidence supports changing the clinical guidelines and routine practice to recommend formal weight loss programs to treat people with NAFLD,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and the Oxford NIHR Collaboration and Leadership in Applied Health Research. The investigators reported grants for other research from Cambridge Weight Plan.

SOURCE: Koutoukidis et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2248.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Weight loss interventions were associated with significantly decreased alanine aminotransferase (-9.81 U/L; I2 = 97%).

Study details: A meta-analysis of randomized clinicals involving weight loss interventions for patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and the Oxford NIHR Collaboration and Leadership in Applied Health Research. The investigators reported grants for other research from Cambridge Weight Plan.

Source: Koutoukidis et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2248.

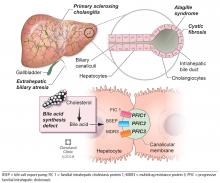

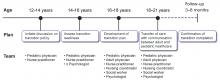

Pediatric cholestatic liver disease: Successful transition of care

Thanks to advances in medical science and our understanding of inherited and acquired liver disease, many more children with acquired or congenital liver disease survive into adulthood than they did 2 decades ago. Improvements in immunosuppression and surgery have increased the chances of pediatric liver transplant recipients reaching adulthood, with a survival rate of 75% at 15 to 20 years.1

With the growing number of adult patients with pediatric-onset liver disease, internists and adult hepatologists need to be aware of these liver diseases and develop expertise to manage this challenging group of patients. Moreover, young adults with pediatric-onset chronic liver disease pose distinct challenges such as pregnancy, adherence to medical regimens, and psychosocial changes in life.

These patients need a “transition of care” rather than a “transfer of care.” Transition of care is a multifaceted process that takes the medical, educational, and psychosocial needs of the patient into consideration before switching their care to adult care physicians, whereas transfer of care is simply an administrative process of change to adult care without previous knowledge of the patients.2

BILIARY ATRESIA

Biliary atresia is a progressive inflammatory fibrosclerosing cholangiopathy of unknown cause. Its prevalence varies with geographic location, ranging from 1 in 6,000 to 1 in 19,000, with the highest prevalence in Taiwan.3

Biliary atresia usually presents within the first few weeks of life, with progressive cholestasis leading to failure to thrive and to fat-soluble vitamin deficiency. Approximately 20% of patients have congenital splenic, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, cardiac, and venous malformations.4,5 Untreated, biliary atresia progresses to end-stage liver disease and death within 2 years.

The first-line treatment for biliary atresia is to establish biliary outflow with the Kasai procedure (hepatic portoenterostomy), in which a jejunal limb is anastomosed in a Roux-en-Y with the liver. The outcomes of the Kasai procedure depend on the timing of surgery, so timely diagnosis of biliary atresia is crucial. When the Kasai procedure is performed within 60 days of birth, biliary flow is achieved in up to 70% of patients; but if performed after 90 days, biliary flow is achieved in fewer than 25%.6

Long-term outcomes of biliary atresia in patients with their native liver have been reported in a few studies.

In a French study,7 743 patients with biliary atresia underwent the Kasai procedure at a median age of 60 days. Survival rates were 57.1% at 2 years, 37.9% at 5 years, 32.4% at 10 years, and 28.5% at 15 years. In other studies,4–9 the 20-year transplant-free survival rate ranged from 23% to 46%. Therefore, at least one-third of children with biliary atresia survive to adulthood with their native liver.

Implications of biliary atresia in adulthood

Although the Kasai procedure improves biliary outflow, up to 70% of patients develop complications of biliary atresia such as progressive fibrosis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, cholangitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, even after a successful Kasai procedure.10

Portal hypertension with evidence of splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, or ascites is found in two-thirds of long-term survivors of biliary atresia with a native liver, with variceal hemorrhage occurring in 30%.11 Therefore, patients with biliary atresia who have evidence of portal hypertension should be screened for varices with upper endoscopy on an annual basis. Management of variceal hemorrhage in these patients includes the use of octreotide, antibiotics, variceal ligation, and sclerotherapy; primary prophylaxis can be achieved with beta-blockers and endoscopic variceal ligation.12

Cholangitis is frequent, occurring in 40% to 60% of biliary atresia patients after the Kasai procedure, and about one-fourth of these patients have multiple episodes.13 The number of episodes of cholangitis negatively affects transplant-free survival.14 Patients with cholangitis should be adequately treated with oral or intravenous antibiotics depending on the severity of presentation. The role of prophylaxis with antibiotics remains unclear.15

Pulmonary complications such as hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension can also occur in biliary atresia patients with a native liver. It is important for physicians to be aware of these complications and to screen for them, for example, with agitated saline echocardiography for hepatopulmonary syndrome and with echocardiography for portopulmonary hypertension. Timely screening is crucial, as the outcome of liver transplant depends on the severity at the time of transplant in these conditions, especially portopulmonary hypertension.

Hepatocellular carcinoma has been rarely reported in children with biliary atresia,16 so well-defined guidelines for screening in young adults with biliary atresia are lacking. Most centers recommend screening with ultrasonography of the abdomen and alpha-fetoprotein measurement every 6 months or annually starting soon after the Kasai procedure, since hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported in children as young as age 2.16

Transplant. Adult hepatologists are faced with the challenging task of deciding when it is time for transplant, balancing the long-term complications of biliary atresia with the risk of long-term immunosuppression after transplant. In addition, young adults with these complications may have preserved synthetic function, resulting in low Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores, which may complicate the process of listing for transplant.

Neurocognitive deficits are reported in children with biliary atresia,17 but young adults with biliary atresia generally have reasonable cognitive function and prospects for education and employment.

Pregnancy with successful outcomes has been reported.8

ALAGILLE SYNDROME

Alagille syndrome is an autosomal-dominant multisystemic disease caused by mutations in the JAG1 gene (accounting for > 95% of cases) and the NOTCH2 gene, with highly variable expression.18

Extrahepatic manifestations include butterfly vertebral defects, facial dysmorphism (eg, deep-set and low-set eyes, with characteristic “triangular” facies), posterior embryotoxon (a congenital defect of the eye characterized by an opaque ring around the margin of the cornea), peripheral pulmonary stenosis, renal abnormalities, and vascular malformations.

Hepatic manifestations vary from asymptomatic laboratory abnormalities to progressive cholestasis starting in early infancy with intractable pruritus, xanthomas, failure to thrive, and end-stage liver disease requiring liver transplant in childhood in 15% to 20% of patients.19

Implications of Alagille syndrome in adulthood

Transplant. Interestingly, the phenotype of hepatic disease is already established in childhood, with minimal or no progression in adulthood. Most children with minimal liver disease experience spontaneous resolution, whereas those with significant cholestasis might ultimately develop progressive liver fibrosis or cirrhosis requiring liver transplant in childhood. Only a small subset of children with minimal cholestasis progress to end-stage liver disease in late childhood or early adulthood.20 Therefore, liver transplant for progressive liver disease from significant cholestasis almost always occurs in childhood, usually between ages 1 and 4.21

In a retrospective study comparing posttransplant outcomes in children with Alagille syndrome and biliary atresia, 1-year patient survival was excellent overall in children with Alagille syndrome, although slightly lower than in children with biliary atresia, most likely owing to extrahepatic morbidities of Alagille syndrome and especially the use of immunosuppression in those with renal disease.21 Similarly, 1- and 5-year patient and graft survival outcomes of liver transplant in adults with Alagille syndrome were also excellent compared with those who received a liver transplant in childhood for Alagille syndrome or in adulthood for biliary atresia.22

Hepatocellular carcinoma has occurred in these patients in the absence of cirrhosis, which makes implementation of prognostic and surveillance strategies almost impossible to design for them. Annual ultrasonography with alpha-fetoprotein testing might be applicable in Alagille syndrome patients. However, deciding which patients should undergo this testing and when it should start will be challenging, given the paucity of data.

Cardiovascular disease. Cardiac phenotype is also mostly established in childhood, with the pulmonary vasculature being most commonly involved.19 In contrast, renal and other vascular abnormalities can manifest in adulthood. Renal manifestations vary and include structural anomalies such as hyperechoic kidneys or renal cysts, which can manifest in childhood, and some abnormalities such as hypertension and renal artery stenosis that can manifest in adulthood.23,24

Vasculopathy is reported to involve the intracranial, renal, and intra-abdominal blood vessels.25 Neurovascular accidents such as stroke and intracranial hemorrhage can occur at any age, with significant rates of morbidity and death.26 Therefore, some experts recommend magnetic resonance angiography every 5 years and before any major intervention to prevent these devastating complications.20

Pregnancy. Successful pregnancies have been reported. Preexisting cardiac and hepatic disease can complicate pregnancy depending on the severity of the disease. Because of the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance, infants have a 50% risk of the disease, so genetic counseling should be seriously considered before conception.27 Prenatal diagnosis is possible, but the lack of genotype-phenotype correlation precludes its use in clinical practice.

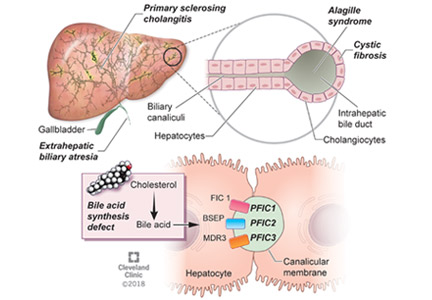

PROGRESSIVE FAMILIAL INTRAHEPATIC CHOLESTASIS

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) is a heterogeneous group of autosomal-recessive conditions associated with disruption of bile formation causing cholestatic liver disease in infants and young children. Three types have been described, depending on the genetic mutation in the hepatobiliary transport pathway:

- PFIC 1 (Byler disease) is caused by impaired bile salt secretion due to mutations in the ATP8B1 gene encoding for the familial intrahepatic cholestasis 1 (FIC 1) protein

- PFIC 2 is caused by impaired bile salt secretion due to mutations in the ABCB11 gene encoding for the bile salt export pump (BSEP) protein

- PFIC 3 is caused by impaired biliary phospholipid secretion due to a defect in ABCB4 encoding for multidrug resistance 3 (MDR3) protein.28

PFIC 1 and 2 manifest with low gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) cholestasis, whereas PFIC 3 presents with high GGT cholestasis.

PFIC 1 and PFIC 2 usually cause cholestasis in early infancy, but PFIC 3 can cause cholestasis in late infancy, childhood, and even adulthood.

Because ATP8B1 is expressed in other tissues, PFIC 1 is characterized by extrahepatic manifestations such as sensorineural hearing loss, growth failure, severe diarrhea, and pancreatic insufficiency.

Implications of PFIC in adulthood

PFIC 1 and 2 (low-GGT cholestasis) are usually progressive and often lead to end-stage liver disease and cirrhosis before adulthood. Therefore, almost all patients with PFIC 1 and 2 undergo liver transplant or at least a biliary diversion procedure before reaching adulthood. Intractable pruritus is one of the most challenging clinical manifestations in patients with PFIC.

First-line management is pharmacologic and includes ursodeoxycholic acid, antihistamines (eg, hydroxyzine), bile acid sequestrants (eg, cholestyramine, colestipol), naltrexone, and rifampin, but these have limited efficacy.10

Most patients, especially those with PFIC 1 and 2, undergo a biliary diversion procedure such as partial external biliary diversion (cholecystojejunocutaneostomy), ileal exclusion, or partial internal biliary diversion (cholecystojejunocolic anastomosis) to decrease enterohepatic circulation of bile salts. The efficacy of these procedures is very limited in patients with established cirrhosis. Excessive losses of bile can occur through the biliary stoma, leading to dehydration in patients with external biliary diversion. In patients who are not candidates for biliary diversion, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage of pancreatobiliary secretions could be achieved by placing a catheter in the common bile duct; this has been reported to be effective in relieving cholestasis in a few cases.29