User login

Improving Access of Personalized Care: Piloting a Telegenetic Program

Purpose: The New Mexico Veterans Affairs Health Care System (NMVAHCS) is striving to improve personalized cancer care and prevention through early identification of hereditary cancer syndromes. Detection of genetic syndromes remains vital for the implementation of precise therapeutic options and prevention measures offering improved veteran-centered care.

Background: Numerous genomic discoveries have provided personalized therapeutic options for improving clinical management of hereditary disease. However, the NMVAHCS lacks professionally trained genetic counselors to appropriately assess and address genetic testing. Primary care physicians lack specialized knowledge regarding appropriate use, application of genetic architectures, and an understanding of result interpretation. This lack of knowledge leaves providers reluctant to apply genomics in clinical practice or utilize testing on inappropriate patients, which remains costly and increases risk for litigation.

Methods: Increasing NMVAHCS access to appropriate genetic counseling involved initiating telehealth consults through the Veteran Affairs Genomic Medicine Service (VAGMS) in Salt Lake, Utah. After seeking stakeholder input and addressing availability of telehealth equipment, VAGMS was contacted. Telehealth service agreements, memorandum of understanding, and information security was obtained to allow offsite access into veterans’ charts. Clinics and consults were built into the computerized patient record system (CPRS), and staff training occurred to learn the intricacies of coordinating virtual appointments and awareness of available service. Initially, consults were limited for breast cancer risk evaluation (BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations), to establish process flow, before opening all genetic counseling consults.

Results: Five appropriately identified veterans received breast cancer risk consults within the first week with fee-based cost savings of over $25,000. Counseling empowered veterans and families with information providing personalized therapeutic options and improving satisfaction and overall outcomes. Although the cost of breast-conserving surgery vs mastectomy remains relatively equal, prophylactic therapies reduce overall associated costs and the psychosocial distress of treating breast cancer, which is estimated to be well over $100,000.

Implications: Increasing access to genetic counseling and testing through partnering with a proven VA genetic program provides veterans with personalized, proactive therapeutic options. The role of genetics will continue to evolve and require collaboration to insure optimal application of precision care for prevention and management of veterans and family members at risk for disease.

Purpose: The New Mexico Veterans Affairs Health Care System (NMVAHCS) is striving to improve personalized cancer care and prevention through early identification of hereditary cancer syndromes. Detection of genetic syndromes remains vital for the implementation of precise therapeutic options and prevention measures offering improved veteran-centered care.

Background: Numerous genomic discoveries have provided personalized therapeutic options for improving clinical management of hereditary disease. However, the NMVAHCS lacks professionally trained genetic counselors to appropriately assess and address genetic testing. Primary care physicians lack specialized knowledge regarding appropriate use, application of genetic architectures, and an understanding of result interpretation. This lack of knowledge leaves providers reluctant to apply genomics in clinical practice or utilize testing on inappropriate patients, which remains costly and increases risk for litigation.

Methods: Increasing NMVAHCS access to appropriate genetic counseling involved initiating telehealth consults through the Veteran Affairs Genomic Medicine Service (VAGMS) in Salt Lake, Utah. After seeking stakeholder input and addressing availability of telehealth equipment, VAGMS was contacted. Telehealth service agreements, memorandum of understanding, and information security was obtained to allow offsite access into veterans’ charts. Clinics and consults were built into the computerized patient record system (CPRS), and staff training occurred to learn the intricacies of coordinating virtual appointments and awareness of available service. Initially, consults were limited for breast cancer risk evaluation (BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations), to establish process flow, before opening all genetic counseling consults.

Results: Five appropriately identified veterans received breast cancer risk consults within the first week with fee-based cost savings of over $25,000. Counseling empowered veterans and families with information providing personalized therapeutic options and improving satisfaction and overall outcomes. Although the cost of breast-conserving surgery vs mastectomy remains relatively equal, prophylactic therapies reduce overall associated costs and the psychosocial distress of treating breast cancer, which is estimated to be well over $100,000.

Implications: Increasing access to genetic counseling and testing through partnering with a proven VA genetic program provides veterans with personalized, proactive therapeutic options. The role of genetics will continue to evolve and require collaboration to insure optimal application of precision care for prevention and management of veterans and family members at risk for disease.

Purpose: The New Mexico Veterans Affairs Health Care System (NMVAHCS) is striving to improve personalized cancer care and prevention through early identification of hereditary cancer syndromes. Detection of genetic syndromes remains vital for the implementation of precise therapeutic options and prevention measures offering improved veteran-centered care.

Background: Numerous genomic discoveries have provided personalized therapeutic options for improving clinical management of hereditary disease. However, the NMVAHCS lacks professionally trained genetic counselors to appropriately assess and address genetic testing. Primary care physicians lack specialized knowledge regarding appropriate use, application of genetic architectures, and an understanding of result interpretation. This lack of knowledge leaves providers reluctant to apply genomics in clinical practice or utilize testing on inappropriate patients, which remains costly and increases risk for litigation.

Methods: Increasing NMVAHCS access to appropriate genetic counseling involved initiating telehealth consults through the Veteran Affairs Genomic Medicine Service (VAGMS) in Salt Lake, Utah. After seeking stakeholder input and addressing availability of telehealth equipment, VAGMS was contacted. Telehealth service agreements, memorandum of understanding, and information security was obtained to allow offsite access into veterans’ charts. Clinics and consults were built into the computerized patient record system (CPRS), and staff training occurred to learn the intricacies of coordinating virtual appointments and awareness of available service. Initially, consults were limited for breast cancer risk evaluation (BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations), to establish process flow, before opening all genetic counseling consults.

Results: Five appropriately identified veterans received breast cancer risk consults within the first week with fee-based cost savings of over $25,000. Counseling empowered veterans and families with information providing personalized therapeutic options and improving satisfaction and overall outcomes. Although the cost of breast-conserving surgery vs mastectomy remains relatively equal, prophylactic therapies reduce overall associated costs and the psychosocial distress of treating breast cancer, which is estimated to be well over $100,000.

Implications: Increasing access to genetic counseling and testing through partnering with a proven VA genetic program provides veterans with personalized, proactive therapeutic options. The role of genetics will continue to evolve and require collaboration to insure optimal application of precision care for prevention and management of veterans and family members at risk for disease.

The Use of a Telehealth Clinic to Support Patients Receiving Radiation Therapy at a Site Distant From Their PCP

Purpose: To try to integrate primary care support from the “spoke” facility during the treatment of patients receiving radiation treatments at the “hub” facility.

Background: Twenty percent of the patients receiving radiation therapy at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center must relocate for up to several months in order to receive their daily treatments due to their distance from the tertiary radiation oncology unit. This makes it impossible for the patients to easily access their primary care provider (PCP) while they are out of town. Patients run out of routine medications, lose weight, have changes in renal function, and require changes in medication during this time; they must then access care via the hub emergency department (ED) or admission. In addition, the provider at the “spoke” is not necessarily in the loop regarding these patients.

Methods: We performed an analysis of the satisfaction with the current process, ED visits, and admissions of radiation oncology caregivers and patients using the Veterans House.

Results: Of patients treated with radiotherapy from April 1,2013, to April 1, 2014, 106 veterans stayed in the Veterans House. Patients who received palliative care with local PCPs were currently being treated at the time of the analysis or declined radiotherapy prior to starting treatment were excluded, leaving 61 patients. Of the 61 patients, there were a total of 48 ED visits and 24 admissions accounting for 168 patient-days in the hospital. A root cause analysis was performed on these48 ED visits; 56% of those were felt to be preventable.

Discussion: After several PDSA (plan-do-study-act) cycles which did not work (involving hub PCPs, involving the ED), we were successful in setting up routine weekly telehealth visits between the patient in Indianapolis at the radiation oncology unit hub and the PCP in the distant facilities in Danville and Peoria, Illinois. This allowed the PCP to manage antihypertensives, diabetic medications, and so on, as the patient moved through the radiation process.

Implications: This pilot process should decrease ED visits and admissions during radiation therapy and also serve to tighten the relationship between the hub and spoke facilities during subspecialist treatment.

Purpose: To try to integrate primary care support from the “spoke” facility during the treatment of patients receiving radiation treatments at the “hub” facility.

Background: Twenty percent of the patients receiving radiation therapy at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center must relocate for up to several months in order to receive their daily treatments due to their distance from the tertiary radiation oncology unit. This makes it impossible for the patients to easily access their primary care provider (PCP) while they are out of town. Patients run out of routine medications, lose weight, have changes in renal function, and require changes in medication during this time; they must then access care via the hub emergency department (ED) or admission. In addition, the provider at the “spoke” is not necessarily in the loop regarding these patients.

Methods: We performed an analysis of the satisfaction with the current process, ED visits, and admissions of radiation oncology caregivers and patients using the Veterans House.

Results: Of patients treated with radiotherapy from April 1,2013, to April 1, 2014, 106 veterans stayed in the Veterans House. Patients who received palliative care with local PCPs were currently being treated at the time of the analysis or declined radiotherapy prior to starting treatment were excluded, leaving 61 patients. Of the 61 patients, there were a total of 48 ED visits and 24 admissions accounting for 168 patient-days in the hospital. A root cause analysis was performed on these48 ED visits; 56% of those were felt to be preventable.

Discussion: After several PDSA (plan-do-study-act) cycles which did not work (involving hub PCPs, involving the ED), we were successful in setting up routine weekly telehealth visits between the patient in Indianapolis at the radiation oncology unit hub and the PCP in the distant facilities in Danville and Peoria, Illinois. This allowed the PCP to manage antihypertensives, diabetic medications, and so on, as the patient moved through the radiation process.

Implications: This pilot process should decrease ED visits and admissions during radiation therapy and also serve to tighten the relationship between the hub and spoke facilities during subspecialist treatment.

Purpose: To try to integrate primary care support from the “spoke” facility during the treatment of patients receiving radiation treatments at the “hub” facility.

Background: Twenty percent of the patients receiving radiation therapy at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center must relocate for up to several months in order to receive their daily treatments due to their distance from the tertiary radiation oncology unit. This makes it impossible for the patients to easily access their primary care provider (PCP) while they are out of town. Patients run out of routine medications, lose weight, have changes in renal function, and require changes in medication during this time; they must then access care via the hub emergency department (ED) or admission. In addition, the provider at the “spoke” is not necessarily in the loop regarding these patients.

Methods: We performed an analysis of the satisfaction with the current process, ED visits, and admissions of radiation oncology caregivers and patients using the Veterans House.

Results: Of patients treated with radiotherapy from April 1,2013, to April 1, 2014, 106 veterans stayed in the Veterans House. Patients who received palliative care with local PCPs were currently being treated at the time of the analysis or declined radiotherapy prior to starting treatment were excluded, leaving 61 patients. Of the 61 patients, there were a total of 48 ED visits and 24 admissions accounting for 168 patient-days in the hospital. A root cause analysis was performed on these48 ED visits; 56% of those were felt to be preventable.

Discussion: After several PDSA (plan-do-study-act) cycles which did not work (involving hub PCPs, involving the ED), we were successful in setting up routine weekly telehealth visits between the patient in Indianapolis at the radiation oncology unit hub and the PCP in the distant facilities in Danville and Peoria, Illinois. This allowed the PCP to manage antihypertensives, diabetic medications, and so on, as the patient moved through the radiation process.

Implications: This pilot process should decrease ED visits and admissions during radiation therapy and also serve to tighten the relationship between the hub and spoke facilities during subspecialist treatment.

Split-Course Palliative Radiotherapy for Advanced Lung Cancer, Using Modern CT-Based Planning

Purpose: Palliative radiotherapy for metastatic and locally advanced lung cancer is commonly used among veterans. We report our institutional experience using a split-course radiotherapy schedule, utilizing modern planning techniques.

Methods: All patients diagnosed with carcinoma of the lung between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2012, were identified in our database. Of these, 35 patients received palliative radiation for stage IV and advanced stage IIIB disease, using a split-course treatment delivery with 3D planning and repeat CT simulation prior to the second half of their treatment course. Radiation was commonly delivered in 25 to 30 Gy in 10 fractions, followed by a 2- to 3-week break with an additional 25 to 30 Gy delivered in10 fractions delivered after a repeat 3D CT simulation.

Results: There was at least a 50% reduction in tumor volume at the time of second simulation (initial tumor volume range: 47 cm3-301 cm3) in 15/35 patients. These were designated as responders and the rest as nonresponders. The median survival in the responder group was 332 days and 340 days in the nonrapid responder group (P = .94). The local failure on imaging was seen in 47% of the responder population and 45% of the nonresponders. The overall 1-year survival for both groups was 34%.

Conclusions: Split-course palliative radiation is a reasonable option for veterans with metastatic and locally advanced lung cancer. Our retrospective review suggests that tumor shrinkage between courses of palliative radiation in a split-course model does not predict survival or local control. A prospective, randomized study would be needed to confirm our findings and make definitive recommendations.

Purpose: Palliative radiotherapy for metastatic and locally advanced lung cancer is commonly used among veterans. We report our institutional experience using a split-course radiotherapy schedule, utilizing modern planning techniques.

Methods: All patients diagnosed with carcinoma of the lung between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2012, were identified in our database. Of these, 35 patients received palliative radiation for stage IV and advanced stage IIIB disease, using a split-course treatment delivery with 3D planning and repeat CT simulation prior to the second half of their treatment course. Radiation was commonly delivered in 25 to 30 Gy in 10 fractions, followed by a 2- to 3-week break with an additional 25 to 30 Gy delivered in10 fractions delivered after a repeat 3D CT simulation.

Results: There was at least a 50% reduction in tumor volume at the time of second simulation (initial tumor volume range: 47 cm3-301 cm3) in 15/35 patients. These were designated as responders and the rest as nonresponders. The median survival in the responder group was 332 days and 340 days in the nonrapid responder group (P = .94). The local failure on imaging was seen in 47% of the responder population and 45% of the nonresponders. The overall 1-year survival for both groups was 34%.

Conclusions: Split-course palliative radiation is a reasonable option for veterans with metastatic and locally advanced lung cancer. Our retrospective review suggests that tumor shrinkage between courses of palliative radiation in a split-course model does not predict survival or local control. A prospective, randomized study would be needed to confirm our findings and make definitive recommendations.

Purpose: Palliative radiotherapy for metastatic and locally advanced lung cancer is commonly used among veterans. We report our institutional experience using a split-course radiotherapy schedule, utilizing modern planning techniques.

Methods: All patients diagnosed with carcinoma of the lung between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2012, were identified in our database. Of these, 35 patients received palliative radiation for stage IV and advanced stage IIIB disease, using a split-course treatment delivery with 3D planning and repeat CT simulation prior to the second half of their treatment course. Radiation was commonly delivered in 25 to 30 Gy in 10 fractions, followed by a 2- to 3-week break with an additional 25 to 30 Gy delivered in10 fractions delivered after a repeat 3D CT simulation.

Results: There was at least a 50% reduction in tumor volume at the time of second simulation (initial tumor volume range: 47 cm3-301 cm3) in 15/35 patients. These were designated as responders and the rest as nonresponders. The median survival in the responder group was 332 days and 340 days in the nonrapid responder group (P = .94). The local failure on imaging was seen in 47% of the responder population and 45% of the nonresponders. The overall 1-year survival for both groups was 34%.

Conclusions: Split-course palliative radiation is a reasonable option for veterans with metastatic and locally advanced lung cancer. Our retrospective review suggests that tumor shrinkage between courses of palliative radiation in a split-course model does not predict survival or local control. A prospective, randomized study would be needed to confirm our findings and make definitive recommendations.

Palliative Care, Advance Care Planning Conversations Needed Between Patients, Hospitalists

Last week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the nation’s largest payer of healthcare services and the 800-pound gorilla in setting medical necessity and coverage policies, announced a proposal to begin paying for goals of care and advance care planning (ACP) discussions between medical providers and patients. Sound familiar? It should. This is the same, seemingly no-brainer proposal that in 2009 was stricken from the eventually approved Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, aka the ACA, aka “Obamacare”) in response to the intentional and patently false accusations of government-run “death panels,” in the hopes of salvaging some measure of bipartisan support. As we all know, the bill eventually passed the following year without a single Republican voting in favor in either the House or Senate, and without funding for ACP sessions!

The need for ACP and access to primary and specialty palliative care is so great and accepted in the healthcare community. In their Choosing Wisely recommendations, numerous medical specialty societies, including ACEP [American College of Emergency Physicians], AAHPM [American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine], AGS [American Geriatrics Society], and AMDA [The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine], have included early and reliable access to palliative care and avoidance of non-value added care, such as placement of feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia, calling out the gap between quality, evidence-based, patient and family-centered care, and “usual care” (e.g. medical and disease-focused care) that patients receive too often near the end of life.

So where is the disconnect between what people want and what actually happens to them at end of life?

The answer is clear: We’re not having “The Conversation.”

And, though our primary care and even specialty care colleagues are involved regularly in the care of these patients, they may be inclined to postpone or avoid ACP with patients and families in the outpatient setting due to lack of comfort [or] skill or even recognizing that the person they’ve been trying valiantly to cure or at least prolong the inevitable [for] is on that downslope of life we all eventually experience—it’s called dying.

Our current reimbursement system throws another barrier in front of providers. Like many other “nonprocedural” activities, ACP is not only undervalued; there is currently a lack of value assigned to this important cognitive, empathic, and communication-based “procedure.” And I refer to it as a procedure because, like a surgical or invasive vascular procedure, when it goes badly, the consequences and sequelae can be just as damaging, and even irreparable.

Thus, intentionally or not, the can is kicked further down the proverbial road until the patient reaches the hospital in a state of crisis—sometimes in extremis—and the hospitalist is left to make sense of all the clinical, emotional, psychological, spiritual, and frequently familial history (baggage?) leading up to that hospital admission. We are expected to develop instant rapport and trust while simultaneously attempting to develop (in collaboration with our specialty care providers and, preferably, the patient’s primary care provider) a plan of care that takes into account the personal values and treatment preferences for that individual within the clinical realities of the patient’s illness and disease trajectory as they lie before us.

Sound familiar?

For the full blog post, including Dr. Epstein’s recommendations for what hospitalists can do to support the CMS proposal, visit Hospital Leader.

Last week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the nation’s largest payer of healthcare services and the 800-pound gorilla in setting medical necessity and coverage policies, announced a proposal to begin paying for goals of care and advance care planning (ACP) discussions between medical providers and patients. Sound familiar? It should. This is the same, seemingly no-brainer proposal that in 2009 was stricken from the eventually approved Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, aka the ACA, aka “Obamacare”) in response to the intentional and patently false accusations of government-run “death panels,” in the hopes of salvaging some measure of bipartisan support. As we all know, the bill eventually passed the following year without a single Republican voting in favor in either the House or Senate, and without funding for ACP sessions!

The need for ACP and access to primary and specialty palliative care is so great and accepted in the healthcare community. In their Choosing Wisely recommendations, numerous medical specialty societies, including ACEP [American College of Emergency Physicians], AAHPM [American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine], AGS [American Geriatrics Society], and AMDA [The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine], have included early and reliable access to palliative care and avoidance of non-value added care, such as placement of feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia, calling out the gap between quality, evidence-based, patient and family-centered care, and “usual care” (e.g. medical and disease-focused care) that patients receive too often near the end of life.

So where is the disconnect between what people want and what actually happens to them at end of life?

The answer is clear: We’re not having “The Conversation.”

And, though our primary care and even specialty care colleagues are involved regularly in the care of these patients, they may be inclined to postpone or avoid ACP with patients and families in the outpatient setting due to lack of comfort [or] skill or even recognizing that the person they’ve been trying valiantly to cure or at least prolong the inevitable [for] is on that downslope of life we all eventually experience—it’s called dying.

Our current reimbursement system throws another barrier in front of providers. Like many other “nonprocedural” activities, ACP is not only undervalued; there is currently a lack of value assigned to this important cognitive, empathic, and communication-based “procedure.” And I refer to it as a procedure because, like a surgical or invasive vascular procedure, when it goes badly, the consequences and sequelae can be just as damaging, and even irreparable.

Thus, intentionally or not, the can is kicked further down the proverbial road until the patient reaches the hospital in a state of crisis—sometimes in extremis—and the hospitalist is left to make sense of all the clinical, emotional, psychological, spiritual, and frequently familial history (baggage?) leading up to that hospital admission. We are expected to develop instant rapport and trust while simultaneously attempting to develop (in collaboration with our specialty care providers and, preferably, the patient’s primary care provider) a plan of care that takes into account the personal values and treatment preferences for that individual within the clinical realities of the patient’s illness and disease trajectory as they lie before us.

Sound familiar?

For the full blog post, including Dr. Epstein’s recommendations for what hospitalists can do to support the CMS proposal, visit Hospital Leader.

Last week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the nation’s largest payer of healthcare services and the 800-pound gorilla in setting medical necessity and coverage policies, announced a proposal to begin paying for goals of care and advance care planning (ACP) discussions between medical providers and patients. Sound familiar? It should. This is the same, seemingly no-brainer proposal that in 2009 was stricken from the eventually approved Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, aka the ACA, aka “Obamacare”) in response to the intentional and patently false accusations of government-run “death panels,” in the hopes of salvaging some measure of bipartisan support. As we all know, the bill eventually passed the following year without a single Republican voting in favor in either the House or Senate, and without funding for ACP sessions!

The need for ACP and access to primary and specialty palliative care is so great and accepted in the healthcare community. In their Choosing Wisely recommendations, numerous medical specialty societies, including ACEP [American College of Emergency Physicians], AAHPM [American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine], AGS [American Geriatrics Society], and AMDA [The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine], have included early and reliable access to palliative care and avoidance of non-value added care, such as placement of feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia, calling out the gap between quality, evidence-based, patient and family-centered care, and “usual care” (e.g. medical and disease-focused care) that patients receive too often near the end of life.

So where is the disconnect between what people want and what actually happens to them at end of life?

The answer is clear: We’re not having “The Conversation.”

And, though our primary care and even specialty care colleagues are involved regularly in the care of these patients, they may be inclined to postpone or avoid ACP with patients and families in the outpatient setting due to lack of comfort [or] skill or even recognizing that the person they’ve been trying valiantly to cure or at least prolong the inevitable [for] is on that downslope of life we all eventually experience—it’s called dying.

Our current reimbursement system throws another barrier in front of providers. Like many other “nonprocedural” activities, ACP is not only undervalued; there is currently a lack of value assigned to this important cognitive, empathic, and communication-based “procedure.” And I refer to it as a procedure because, like a surgical or invasive vascular procedure, when it goes badly, the consequences and sequelae can be just as damaging, and even irreparable.

Thus, intentionally or not, the can is kicked further down the proverbial road until the patient reaches the hospital in a state of crisis—sometimes in extremis—and the hospitalist is left to make sense of all the clinical, emotional, psychological, spiritual, and frequently familial history (baggage?) leading up to that hospital admission. We are expected to develop instant rapport and trust while simultaneously attempting to develop (in collaboration with our specialty care providers and, preferably, the patient’s primary care provider) a plan of care that takes into account the personal values and treatment preferences for that individual within the clinical realities of the patient’s illness and disease trajectory as they lie before us.

Sound familiar?

For the full blog post, including Dr. Epstein’s recommendations for what hospitalists can do to support the CMS proposal, visit Hospital Leader.

VIDEO: Consistency is key to monitoring patients on opioids

ORLANDO – Take a consistent approach with all patients on opioid therapy, regardless of a patient’s perceived potential for abuse, Dr. Melissa B. Weimer advised.

“This is an area of medicine where I feel we need to apply universal precautions to all patients,” noted Dr. Weimer, assistant professor of medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. “We’re treating all patients as at some level of potential harm from this medication.”

In an interview at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Weimer outlined a strategy that employs the same protocol to monitor therapy, even when the abuse potential is considered to be low.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Weimer reported no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – Take a consistent approach with all patients on opioid therapy, regardless of a patient’s perceived potential for abuse, Dr. Melissa B. Weimer advised.

“This is an area of medicine where I feel we need to apply universal precautions to all patients,” noted Dr. Weimer, assistant professor of medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. “We’re treating all patients as at some level of potential harm from this medication.”

In an interview at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Weimer outlined a strategy that employs the same protocol to monitor therapy, even when the abuse potential is considered to be low.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Weimer reported no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – Take a consistent approach with all patients on opioid therapy, regardless of a patient’s perceived potential for abuse, Dr. Melissa B. Weimer advised.

“This is an area of medicine where I feel we need to apply universal precautions to all patients,” noted Dr. Weimer, assistant professor of medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. “We’re treating all patients as at some level of potential harm from this medication.”

In an interview at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Weimer outlined a strategy that employs the same protocol to monitor therapy, even when the abuse potential is considered to be low.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Weimer reported no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE

VIDEO: Use fiduciary duty to set pain medication boundaries

ORLANDO – Physicians should use the concept of fiduciary duty to set appropriate boundaries with patients taking pain medications, explained Dr. Louis Kuritzky.

Often, patients want treatments that are not in their best interests, noted Dr. Kuritzky of the department of community health and family medicine at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In an interview at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Kuritzky outlined how physicians can take a fiduciary duty approach to set boundaries with patients in a dispassionate manner.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Kuritzky reported a financial relationship with Lilly.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – Physicians should use the concept of fiduciary duty to set appropriate boundaries with patients taking pain medications, explained Dr. Louis Kuritzky.

Often, patients want treatments that are not in their best interests, noted Dr. Kuritzky of the department of community health and family medicine at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In an interview at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Kuritzky outlined how physicians can take a fiduciary duty approach to set boundaries with patients in a dispassionate manner.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Kuritzky reported a financial relationship with Lilly.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – Physicians should use the concept of fiduciary duty to set appropriate boundaries with patients taking pain medications, explained Dr. Louis Kuritzky.

Often, patients want treatments that are not in their best interests, noted Dr. Kuritzky of the department of community health and family medicine at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In an interview at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Kuritzky outlined how physicians can take a fiduciary duty approach to set boundaries with patients in a dispassionate manner.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Kuritzky reported a financial relationship with Lilly.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE

Updates on Cancer Survivorship Care Planning

With advances in treatment, supportive care, and early diagnosis, the prevalence of cancer is increasing. An individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis to the end of his or her life.1 Although many patients with cancer are cured, they experience various short-term and long-term effects of cancer treatment, a high risk of recurrence and second cancer, anxiety, chronic pain, fatigue, depression, sexual dysfunction, and infertility.1

As of January 1, 2014, there were about 14.5 million cancer survivors in the U.S. The most common cancers in this population include prostate (43%), colon and rectal (9%), and melanoma (8%) in males; breast (41%), uterine corpus (8%), and colon and rectal (8%) in females.2 This estimate does not include noninvasive cancers, but does include bladder, basal cell, and squamous cell skin cancers. By January 1, 2024, the population of cancer survivors is predicted to increase to almost 19 million: 9.3 million males and 9.6 million females.1 Most of the cancer survivors (64%) were diagnosed 5 or more years ago, and 15% were diagnosed 20 or more years ago. Nearly half (46%) of cancer survivors are aged ≥ 70 years, and only 5% are aged < 40 years.2

Moye and colleagues reported that 524,052 (11%) of veterans treated in 2007 were cancer survivors.3 The most common types of cancers among these veterans were prostate, skin (nonmelanoma), and colorectal cancers. Compared with the general population of cancer survivors in the SEER database, veteran survivors were older.3 Because of the increasing prevalence of cancer survivors, greater attention is focused on long-term complications of cancer treatment. Recent studies have demonstrated that cancer survivors are less likely to receive general preventive care and care associated with noncancer-related medical conditions than are individuals without cancer.4

Survivorship Care Components

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost to Transition.5 The report addresses 4 essential components of survivorship care: (1) prevention of recurrence, new cancers, and other late effects; (2) surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, second cancers, and medical and psychosocial adverse events (AEs); (3) interventions for consequences of cancer and its treatment (medical problems, symptoms, psychological distress experienced by cancer survivors and their caregivers, and concerns related to employment, insurance, and disability); and (4) coordination between the specialist and primary care providers (PCPs) to ensure that all the survivors’ health needs are met.5

Cancer Treatment Summary

To ensure better transition, the IOM recommended that survivorship plans be made with a summary of treatment provided by the primary oncologist who treated the patient, to improve communication among all health care providers and between the providers and the patient.5 The summary should include the date of diagnosis; diagnostic tests; stage of diagnosis; a medical, surgical, and radiation treatment summary; and a detailed follow-up care plan. The IOM also recommends preventive practices to maintain health and well-being; information on legal protection regarding employment and health insurance; the availability of psychosocial services in the community; and screening for psychosocial distress in cancer survivors.3,6 However, studies have shown that gaps in adherence with IOM recommendations exist even in dedicated survivorship centers.7,8

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and organizations such as Livestrong also have developed templates for survivorship care plans (SCPs). But there has been limited success in implementing SCPs.7,8 The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) Standard 3.3 is scheduled to be implemented in 2015.9 The standard is expected to require that a cancer care committee develop and implement a process to disseminate a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan for cancer survivors.9 To address this need, ASCO has formed a joint work group for improving cancer survivorship and a new version of an SCP template. This group recommended including contact information for the oncology providers who administered the treatment; basic diagnostic and staging information; and information on surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy (both chemotherapy and biologic therapy), and ongoing significant toxicities, including dates (Table 1).10

The ASCO also developed a follow-up care plan that includes a surveillance plan to detect recurrence and late AEs; interventions to manage ongoing problems resulting from cancer and its treatment; and age- and sex-appropriate health care, including cancer screening and general health promotion. It also recommended that the follow-up care plan should include a schedule of clinic visits in a table format, surveillance care testing to detect recurrence and second primary cancers, such as early breast cancer screening for women who underwent chest radiation for Hodgkin lymphoma. The person responsible for ordering these screening test should be included in the follow-up care plan.10 In addition, ASCO developed a cancer survivorship compendium, which included not only tools and resources, but also different models for cancer survivorship care.11 In addition, ASCO developed a Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) to assess the quality of survivorship programs.9

The Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) adopted National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), ASCO, and National Cancer Institute (NCI) guidelines and developed a template for a cancer treatment summary that includes the cancer type; grade; staging; and date of diagnosis and duration of treatment, including chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation with a disease-specific follow-up care plan for each type of cancer. The treatment summary is a useful tool to communicate a patient’s treatment and disease status to PCPs and patients.

Models of Care

Eight models for delivering survivorship care have been developed by ASCO11:

- Oncologist Specialist Care: Care occurs as a continuation in the oncology setting

- Multidisciplinary Survivor Clinic: Different specialists provide care

- General Survivorship Clinic: Care is provided by a physician or advanced care provider (APN) and implemented at a cancer center or private practice

- Consultative Survivorship Clinic: Initial follow-up is provided in an oncology setting with an eventual transition to a PCP; patients may be directed to the cancer center for needed services

- Integrated Survivorship Clinic: Care is provided by a physician or APN, and the care is coordinated with the PCP and other specialists as needed

- Community Generalist Model: The PCP, APN, or internist within the community provides care

- Shared-Care of Survivor: Care is coordinated and provided by any combination of specialists, PCPs, and nurses and is patient directed

Depending on the patients and the setting, practices can adopt various models to deliver survivorship care.

At CAVHS, cancer survivors are followed by an oncologist for their yearly examinations. This model is an illness model rather than a wellness model. A multidisciplinary clinic model can be initiated at CAVHS with the help of palliative care; complementary and alternative medicine for pain management; psychologists, chaplain services, and social workers for distress management; and coordination of survivorship care.

Implementation Barriers

There are many barriers to implementing SCPs, including time required by the providers to complete SCPs, inadequate reimbursement for the time and resources required to complete SCPs, challenges in coordinating care between survivors and providers, and lack of compatibility of the existing template with the electronic health record (EHR).7-10 A study regarding the barriers to implementation of SCPs, conducted at 14 NCI community cancer centers, demonstrated that the most common barrier is lack of personnel and time required to complete SCPs. The most widely used strategies was the use of a template with prespecified fields and delegating the completion of SCPs to one individual.12

Long-Term Complications for Survivors

Cancer survivors experience the physical and psychosocial effects of cancer treatment and have a very high risk of recurrence and second primary cancers. Common chronic AEs include fatigue, pain, neuropathy, infertility, sexual dysfunction, hypothyroidism, organ dysfunction, and urinary and bowel incontinence. In addition, patients also experience psychological AEs, including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and sleep disturbances. Because of the AEs, cancer survivors have difficulty obtaining employment and insurance.1,5

Fatigue

Fatigue is the most common AE in cancer survivors.1 It may develop during treatment and persist for years. It is related to chemotherapy, radiation, surgical complications, depression, and insomnia.1 It is underrecognized and often untreated. It is important to assess and treat underlying comorbidities such as anemia, hypothyroidism, pain, depression and insomnia.13,14 Pharmacologic therapy with central nervous system stimulants and antidepressants have not shown any benefit.15 Studies on modafinil and armodafinil are ongoing.15 Exercise, treating underlying depression, sleep hygiene, behavioral and cognitive therapy, and yoga and mindfulness management of distress can help in treating fatigue.13 Meta-analyses showed that physical exercise helped reduce cancerrelated fatigue.15 A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that yoga led to significant improvement in fatigue in breast cancer survivors.16 Hence, it is important for providers to recognize and treat cancer-related fatigue and encourage patients to exercise.17

Psychological Adverse Effects

Cancer survivors also experience psychological AEs such as anxiety and depression because of the cancer diagnosis and the uncertainty of the outcome and the fear of relapse. Veterans may be at a higher risk of psychological AEs because of underlying mental illnesses. Counseling about the disease, psychotherapy interventions, and a mindfulness approach are recommended to treat anxiety and depression.14 The CAVHS cancer program has developed a mindfulness program as a multidisciplinary approach to manage psychological AEs.18

Sexual Dysfunction

Many patients may experience sexual dysfunction and infertility as a result of endocrine treatments, chemotherapy, radiation, and urologic and gynecologic surgeries.1 Over half of prostate cancer and breast cancer survivors report sexual dysfunction. Despite its high prevalence, sexual dysfunction often is not discussed with patients due to reluctance to discuss, lack of training, and lack of a standardized sexuality questionnaire.19 A brief sexual symptom checklist for women can be used as a primary screening tool. It is also recommended to screen for treatment-related infertility. Patients with sexual dysfunction should undergo screening for psychosocial problems such as anxiety, depression, and drug and alcohol use and treatment as these can contribute to sexual dysfunction.1

Vaginal lubricants are recommended to treat vaginal dryness. Vaginal estrogen creams are effective in patients with nonhormone-dependent gynecologic cancer without risk of breast cancer. The FDA approved the selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene for treating dyspareunia in postmenopausal women without risk of breast cancer.1 Oral phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil, vacuum erection devices, penile prosthesis, and intracavernous injections, have shown to be effective in treating male erectile dysfunction (ED).19

Cardiovascular risk should be estimated in all patients with ED, because most of these patients will have common risk factors and need to be referred to a cardiologist before treating ED.1

Chronic Pain

Patients may also experience chronic pain as a late complication of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.1 More than one-third of cancer survivors experience pain, and it is often ineffectively managed due to lack of training, fear of AEs, and addiction.20 The goals of pain management are to increase comfort and improve quality of life. Short-acting and long-acting opioids remain an important treatment for cancer pain. Drug selection should be guided by previous exposure and comorbidities.15 Opioid therapy AEs, such as constipation, sleep apnea, and hypogonadism, should be recognized and treated. Antidepressants and anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, may be used to manage neuropathic pain. A multidisciplinary approach using pharmacologic therapy, psychosocial therapy, behavioral interventions, exercise, and physical therapy is recommended.15 Patients with refractory pain are treated with interventional approaches, such as a neuronal blockade.

Survivorship Resources

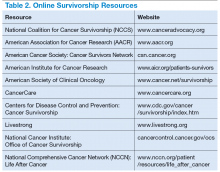

Survivorship resources were developed by various cancer societies, such as NCCN, ASCO, Livestrong, and the Children’s Oncology Group. These resources help providers develop and deliver a quality survivorship care program (Table 2).5 The NCCN provides a template to help create cancer treatment summaries; guidelines for follow-up care for different cancers; and information for patients on legal and employment issues, smoking cessation, nutrition, and weight loss. In addition, the NCCN provides tools to assess anthracyclineinduced cardiac toxicity, anxiety, depression, cognitive dysfunction, pain, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue.

The CAVHS has several resources to develop a survivor ship progr am: It offers complementary and alternative therapy (a multidisciplinary approach) to help veterans with chronic pain and psychological distress. This resource incorporates acupuncture, yoga, hypnotherapy, biofeedback, mind-body approaches, stress management, nutritional counseling, physical therapy, and other mental and behavioral health support.

In addition, VA is implementing a patient-centered care and cultural transformation program to help veterans establish a relationship with their health care providers.21 The patient-centered approach along with the complementary and alternative therapy program, mindfulness program, and telehealth exercise motivation program can be incorporated to develop a multidisciplinary survivorship program.

Survivorship Research

Survivorship is an emerging field, and there is need for research to improve the implementation of quality survivorship care. Cancer survivorship research encompasses the physical, psychosocial, and economic sequelae of cancer diagnosis and its treatment among both pediatric and adult survivors of cancer. It also includes issues related to health care delivery, access, and follow-up care.

Mayer and colleagues reported that there were 42 published studies of SCPs in adult cancer survivors.22 Eleven studies reported that SCP use was limited and that < 25% of oncology providers never used an SCP. Research also showed that oncologists who have had training in long-term AEs of cancer and those who have used the EHRs were more likely to use SCPs.23 An integrated review of studies of SCPs recommended areas of research for survivorship. Thus the quality and quantity of SCP research are limited, and there is more need for quality research in survivorship to endorse the effective use of SCPs.

Conclusion

Cancer patients experience various AEs of cancer treatment, psychosocial distress, and can be lost to follow-up. It is important for health care providers to recognize and screen for the complications and provide SCPs, which includes a treatment summary and follow-up care to communicate and coordinate quality cancer survivorship care. Providers can use tools and resources developed by various organizations to develop and implement SCPs. The CoC surveys and accredits the cancer programs for quality measures, and has developed a new standard to provide SCPs for all patients effective 2015.

The CAVHS has already adopted this standard and has developed a template to complete a treatment summary and follow-up care planning in the EHR. The cancer treatment summary is given to the patient and is available to the PCP for review. There is also a need for more quality research in survivorship.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to continue reading.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: survivorship. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf. Updated February 27, 2015. Accessed July 20, 2015.

2. American Cancer Society. Cancer treatment and survivorship facts and figures 2014-2015. American Cancer Society Website. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042801.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2015.

3. Moye J, Schuster J, Latini D, Naik A. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Fed Pract. 2010;27(3):36-43.

4. Snyder CF, Frick KD, Kantisiper ME, et al. Prevention, screening, and surveillance care for breast cancer survivors compared with controls: changes from 1998 to 2002. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1054-1061.

5. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds; Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life, Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

6. Adler NE, Page AEK, eds; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK4015/. Accessed July 10, 2015.

7. Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Risendal B, et al. Survivorship care planning after the institute of medicine recommendations: how are we faring? J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):358-370.

8. Salz T, McCabe MS, Onstad EE, et al. Survivorship care plans: is there buy-in from community oncology providers? Cancer. 2014;120(5):722-730.

9. American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care.V1.2.1. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons;2012. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer

/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Accessed July 8, 2015.

10. Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, Merill JK, Wollins DS, Shulman LN. American Society of Clinical Oncology expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(6):345-351.

11. American Society of Clinical Oncology. ASCO cancer survivorship compendium. American Society of Clinical Oncology Website. http://www.asco.org/practice-research/asco-cancer-survivorship-compendium. Accessed July 10, 2015.

12. Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Leach CR, Ganz PA, Stefanek ME, Rowland JH. Who provides psychosocial follow-up care for post-treatment cancer survivors? A survey of medical oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(23):2897-2905.

13. Mitchell SA, Hoffman AJ, Clark JC, et al. Putting evidence into practice: an update of evidence-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue during and following

treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(suppl):38-58.

14. Partridge AH, Jacobsen PB, Andersen BL. Challenges to standardizing the care for

adult cancer survivors: highlighing ASCO’s fatigue and anxiety and depression guidelines. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015;35:188-194.

15. Pachman DR, Barton DL, Swetz KM, Loprinzi CL. Troublesome symptoms in cancer survivors: fatigue, insomnia, neuropathy, and pain. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3687-3696.

16. Cramp F, Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer–related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(2):CD006145.

17. Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2011;118(15):3766-3775.

18. Mesidor M, Kunthur A, Mehta P, et al. Mindfulness and cancer. Paper presented at: Annual meeting of Association of VA Hematologists/Oncologists; October 2015; Washington, DC.

19. Goncalves P, Groninger H. Sexual dysfunction in cancer patients and survivors #293. J Palliat Med. 2015 [Epub ahead of print].

20. Pargeon KL, Hailey BJ. Barriers to effective pain management: a review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18(5):358-368.

21. Heneghan C. The future of veteran care? Health Care Journal of Little Rock. May/June. http://www.healthcarejournallr.com/the-journal/contents-index/features/567-integrative-medicine.html. Accessed July 10, 2015.

22. Mayer DK, Birken SA, Check DK, Chen RC. Summing it up: an integrated

review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006-2013). Cancer. 2015;121(7):978-996.

23. Blanch-Hartigan D, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, et al. Provision and discussion of survivorship care plans among cancer survivors: results of a nationally representative survey of oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1578-1585.

With advances in treatment, supportive care, and early diagnosis, the prevalence of cancer is increasing. An individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis to the end of his or her life.1 Although many patients with cancer are cured, they experience various short-term and long-term effects of cancer treatment, a high risk of recurrence and second cancer, anxiety, chronic pain, fatigue, depression, sexual dysfunction, and infertility.1

As of January 1, 2014, there were about 14.5 million cancer survivors in the U.S. The most common cancers in this population include prostate (43%), colon and rectal (9%), and melanoma (8%) in males; breast (41%), uterine corpus (8%), and colon and rectal (8%) in females.2 This estimate does not include noninvasive cancers, but does include bladder, basal cell, and squamous cell skin cancers. By January 1, 2024, the population of cancer survivors is predicted to increase to almost 19 million: 9.3 million males and 9.6 million females.1 Most of the cancer survivors (64%) were diagnosed 5 or more years ago, and 15% were diagnosed 20 or more years ago. Nearly half (46%) of cancer survivors are aged ≥ 70 years, and only 5% are aged < 40 years.2

Moye and colleagues reported that 524,052 (11%) of veterans treated in 2007 were cancer survivors.3 The most common types of cancers among these veterans were prostate, skin (nonmelanoma), and colorectal cancers. Compared with the general population of cancer survivors in the SEER database, veteran survivors were older.3 Because of the increasing prevalence of cancer survivors, greater attention is focused on long-term complications of cancer treatment. Recent studies have demonstrated that cancer survivors are less likely to receive general preventive care and care associated with noncancer-related medical conditions than are individuals without cancer.4

Survivorship Care Components

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost to Transition.5 The report addresses 4 essential components of survivorship care: (1) prevention of recurrence, new cancers, and other late effects; (2) surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, second cancers, and medical and psychosocial adverse events (AEs); (3) interventions for consequences of cancer and its treatment (medical problems, symptoms, psychological distress experienced by cancer survivors and their caregivers, and concerns related to employment, insurance, and disability); and (4) coordination between the specialist and primary care providers (PCPs) to ensure that all the survivors’ health needs are met.5

Cancer Treatment Summary

To ensure better transition, the IOM recommended that survivorship plans be made with a summary of treatment provided by the primary oncologist who treated the patient, to improve communication among all health care providers and between the providers and the patient.5 The summary should include the date of diagnosis; diagnostic tests; stage of diagnosis; a medical, surgical, and radiation treatment summary; and a detailed follow-up care plan. The IOM also recommends preventive practices to maintain health and well-being; information on legal protection regarding employment and health insurance; the availability of psychosocial services in the community; and screening for psychosocial distress in cancer survivors.3,6 However, studies have shown that gaps in adherence with IOM recommendations exist even in dedicated survivorship centers.7,8

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and organizations such as Livestrong also have developed templates for survivorship care plans (SCPs). But there has been limited success in implementing SCPs.7,8 The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) Standard 3.3 is scheduled to be implemented in 2015.9 The standard is expected to require that a cancer care committee develop and implement a process to disseminate a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan for cancer survivors.9 To address this need, ASCO has formed a joint work group for improving cancer survivorship and a new version of an SCP template. This group recommended including contact information for the oncology providers who administered the treatment; basic diagnostic and staging information; and information on surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy (both chemotherapy and biologic therapy), and ongoing significant toxicities, including dates (Table 1).10

The ASCO also developed a follow-up care plan that includes a surveillance plan to detect recurrence and late AEs; interventions to manage ongoing problems resulting from cancer and its treatment; and age- and sex-appropriate health care, including cancer screening and general health promotion. It also recommended that the follow-up care plan should include a schedule of clinic visits in a table format, surveillance care testing to detect recurrence and second primary cancers, such as early breast cancer screening for women who underwent chest radiation for Hodgkin lymphoma. The person responsible for ordering these screening test should be included in the follow-up care plan.10 In addition, ASCO developed a cancer survivorship compendium, which included not only tools and resources, but also different models for cancer survivorship care.11 In addition, ASCO developed a Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) to assess the quality of survivorship programs.9

The Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) adopted National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), ASCO, and National Cancer Institute (NCI) guidelines and developed a template for a cancer treatment summary that includes the cancer type; grade; staging; and date of diagnosis and duration of treatment, including chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation with a disease-specific follow-up care plan for each type of cancer. The treatment summary is a useful tool to communicate a patient’s treatment and disease status to PCPs and patients.

Models of Care

Eight models for delivering survivorship care have been developed by ASCO11:

- Oncologist Specialist Care: Care occurs as a continuation in the oncology setting

- Multidisciplinary Survivor Clinic: Different specialists provide care

- General Survivorship Clinic: Care is provided by a physician or advanced care provider (APN) and implemented at a cancer center or private practice

- Consultative Survivorship Clinic: Initial follow-up is provided in an oncology setting with an eventual transition to a PCP; patients may be directed to the cancer center for needed services

- Integrated Survivorship Clinic: Care is provided by a physician or APN, and the care is coordinated with the PCP and other specialists as needed

- Community Generalist Model: The PCP, APN, or internist within the community provides care

- Shared-Care of Survivor: Care is coordinated and provided by any combination of specialists, PCPs, and nurses and is patient directed

Depending on the patients and the setting, practices can adopt various models to deliver survivorship care.

At CAVHS, cancer survivors are followed by an oncologist for their yearly examinations. This model is an illness model rather than a wellness model. A multidisciplinary clinic model can be initiated at CAVHS with the help of palliative care; complementary and alternative medicine for pain management; psychologists, chaplain services, and social workers for distress management; and coordination of survivorship care.

Implementation Barriers

There are many barriers to implementing SCPs, including time required by the providers to complete SCPs, inadequate reimbursement for the time and resources required to complete SCPs, challenges in coordinating care between survivors and providers, and lack of compatibility of the existing template with the electronic health record (EHR).7-10 A study regarding the barriers to implementation of SCPs, conducted at 14 NCI community cancer centers, demonstrated that the most common barrier is lack of personnel and time required to complete SCPs. The most widely used strategies was the use of a template with prespecified fields and delegating the completion of SCPs to one individual.12

Long-Term Complications for Survivors

Cancer survivors experience the physical and psychosocial effects of cancer treatment and have a very high risk of recurrence and second primary cancers. Common chronic AEs include fatigue, pain, neuropathy, infertility, sexual dysfunction, hypothyroidism, organ dysfunction, and urinary and bowel incontinence. In addition, patients also experience psychological AEs, including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and sleep disturbances. Because of the AEs, cancer survivors have difficulty obtaining employment and insurance.1,5

Fatigue

Fatigue is the most common AE in cancer survivors.1 It may develop during treatment and persist for years. It is related to chemotherapy, radiation, surgical complications, depression, and insomnia.1 It is underrecognized and often untreated. It is important to assess and treat underlying comorbidities such as anemia, hypothyroidism, pain, depression and insomnia.13,14 Pharmacologic therapy with central nervous system stimulants and antidepressants have not shown any benefit.15 Studies on modafinil and armodafinil are ongoing.15 Exercise, treating underlying depression, sleep hygiene, behavioral and cognitive therapy, and yoga and mindfulness management of distress can help in treating fatigue.13 Meta-analyses showed that physical exercise helped reduce cancerrelated fatigue.15 A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that yoga led to significant improvement in fatigue in breast cancer survivors.16 Hence, it is important for providers to recognize and treat cancer-related fatigue and encourage patients to exercise.17

Psychological Adverse Effects

Cancer survivors also experience psychological AEs such as anxiety and depression because of the cancer diagnosis and the uncertainty of the outcome and the fear of relapse. Veterans may be at a higher risk of psychological AEs because of underlying mental illnesses. Counseling about the disease, psychotherapy interventions, and a mindfulness approach are recommended to treat anxiety and depression.14 The CAVHS cancer program has developed a mindfulness program as a multidisciplinary approach to manage psychological AEs.18

Sexual Dysfunction

Many patients may experience sexual dysfunction and infertility as a result of endocrine treatments, chemotherapy, radiation, and urologic and gynecologic surgeries.1 Over half of prostate cancer and breast cancer survivors report sexual dysfunction. Despite its high prevalence, sexual dysfunction often is not discussed with patients due to reluctance to discuss, lack of training, and lack of a standardized sexuality questionnaire.19 A brief sexual symptom checklist for women can be used as a primary screening tool. It is also recommended to screen for treatment-related infertility. Patients with sexual dysfunction should undergo screening for psychosocial problems such as anxiety, depression, and drug and alcohol use and treatment as these can contribute to sexual dysfunction.1

Vaginal lubricants are recommended to treat vaginal dryness. Vaginal estrogen creams are effective in patients with nonhormone-dependent gynecologic cancer without risk of breast cancer. The FDA approved the selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene for treating dyspareunia in postmenopausal women without risk of breast cancer.1 Oral phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil, vacuum erection devices, penile prosthesis, and intracavernous injections, have shown to be effective in treating male erectile dysfunction (ED).19

Cardiovascular risk should be estimated in all patients with ED, because most of these patients will have common risk factors and need to be referred to a cardiologist before treating ED.1

Chronic Pain

Patients may also experience chronic pain as a late complication of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.1 More than one-third of cancer survivors experience pain, and it is often ineffectively managed due to lack of training, fear of AEs, and addiction.20 The goals of pain management are to increase comfort and improve quality of life. Short-acting and long-acting opioids remain an important treatment for cancer pain. Drug selection should be guided by previous exposure and comorbidities.15 Opioid therapy AEs, such as constipation, sleep apnea, and hypogonadism, should be recognized and treated. Antidepressants and anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, may be used to manage neuropathic pain. A multidisciplinary approach using pharmacologic therapy, psychosocial therapy, behavioral interventions, exercise, and physical therapy is recommended.15 Patients with refractory pain are treated with interventional approaches, such as a neuronal blockade.

Survivorship Resources

Survivorship resources were developed by various cancer societies, such as NCCN, ASCO, Livestrong, and the Children’s Oncology Group. These resources help providers develop and deliver a quality survivorship care program (Table 2).5 The NCCN provides a template to help create cancer treatment summaries; guidelines for follow-up care for different cancers; and information for patients on legal and employment issues, smoking cessation, nutrition, and weight loss. In addition, the NCCN provides tools to assess anthracyclineinduced cardiac toxicity, anxiety, depression, cognitive dysfunction, pain, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue.

The CAVHS has several resources to develop a survivor ship progr am: It offers complementary and alternative therapy (a multidisciplinary approach) to help veterans with chronic pain and psychological distress. This resource incorporates acupuncture, yoga, hypnotherapy, biofeedback, mind-body approaches, stress management, nutritional counseling, physical therapy, and other mental and behavioral health support.

In addition, VA is implementing a patient-centered care and cultural transformation program to help veterans establish a relationship with their health care providers.21 The patient-centered approach along with the complementary and alternative therapy program, mindfulness program, and telehealth exercise motivation program can be incorporated to develop a multidisciplinary survivorship program.

Survivorship Research

Survivorship is an emerging field, and there is need for research to improve the implementation of quality survivorship care. Cancer survivorship research encompasses the physical, psychosocial, and economic sequelae of cancer diagnosis and its treatment among both pediatric and adult survivors of cancer. It also includes issues related to health care delivery, access, and follow-up care.

Mayer and colleagues reported that there were 42 published studies of SCPs in adult cancer survivors.22 Eleven studies reported that SCP use was limited and that < 25% of oncology providers never used an SCP. Research also showed that oncologists who have had training in long-term AEs of cancer and those who have used the EHRs were more likely to use SCPs.23 An integrated review of studies of SCPs recommended areas of research for survivorship. Thus the quality and quantity of SCP research are limited, and there is more need for quality research in survivorship to endorse the effective use of SCPs.

Conclusion

Cancer patients experience various AEs of cancer treatment, psychosocial distress, and can be lost to follow-up. It is important for health care providers to recognize and screen for the complications and provide SCPs, which includes a treatment summary and follow-up care to communicate and coordinate quality cancer survivorship care. Providers can use tools and resources developed by various organizations to develop and implement SCPs. The CoC surveys and accredits the cancer programs for quality measures, and has developed a new standard to provide SCPs for all patients effective 2015.

The CAVHS has already adopted this standard and has developed a template to complete a treatment summary and follow-up care planning in the EHR. The cancer treatment summary is given to the patient and is available to the PCP for review. There is also a need for more quality research in survivorship.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to continue reading.

With advances in treatment, supportive care, and early diagnosis, the prevalence of cancer is increasing. An individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis to the end of his or her life.1 Although many patients with cancer are cured, they experience various short-term and long-term effects of cancer treatment, a high risk of recurrence and second cancer, anxiety, chronic pain, fatigue, depression, sexual dysfunction, and infertility.1

As of January 1, 2014, there were about 14.5 million cancer survivors in the U.S. The most common cancers in this population include prostate (43%), colon and rectal (9%), and melanoma (8%) in males; breast (41%), uterine corpus (8%), and colon and rectal (8%) in females.2 This estimate does not include noninvasive cancers, but does include bladder, basal cell, and squamous cell skin cancers. By January 1, 2024, the population of cancer survivors is predicted to increase to almost 19 million: 9.3 million males and 9.6 million females.1 Most of the cancer survivors (64%) were diagnosed 5 or more years ago, and 15% were diagnosed 20 or more years ago. Nearly half (46%) of cancer survivors are aged ≥ 70 years, and only 5% are aged < 40 years.2

Moye and colleagues reported that 524,052 (11%) of veterans treated in 2007 were cancer survivors.3 The most common types of cancers among these veterans were prostate, skin (nonmelanoma), and colorectal cancers. Compared with the general population of cancer survivors in the SEER database, veteran survivors were older.3 Because of the increasing prevalence of cancer survivors, greater attention is focused on long-term complications of cancer treatment. Recent studies have demonstrated that cancer survivors are less likely to receive general preventive care and care associated with noncancer-related medical conditions than are individuals without cancer.4

Survivorship Care Components

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost to Transition.5 The report addresses 4 essential components of survivorship care: (1) prevention of recurrence, new cancers, and other late effects; (2) surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, second cancers, and medical and psychosocial adverse events (AEs); (3) interventions for consequences of cancer and its treatment (medical problems, symptoms, psychological distress experienced by cancer survivors and their caregivers, and concerns related to employment, insurance, and disability); and (4) coordination between the specialist and primary care providers (PCPs) to ensure that all the survivors’ health needs are met.5

Cancer Treatment Summary