User login

Worried parents scramble to vaccinate kids despite FDA guidance

One week after reporting promising results from the trial of their COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 5-11, Pfizer and BioNTech announced they’d submitted the data to the Food and Drug Administration. But that hasn’t stopped some parents from discreetly getting their children under age 12 vaccinated.

“The FDA, you never want to get ahead of their judgment,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC on Sept. 28. “But I would imagine in the next few weeks, they will examine that data and hopefully they’ll give the okay so that we can start vaccinating children, hopefully before the end of October.”

Lying to vaccinate now

More than half of all parents with children under 12 say they plan to get their kids vaccinated, according to a Gallup poll.

And although the FDA and the American Academy of Pediatrics have warned against it, some parents whose children can pass for 12 have lied to get them vaccinated already.

Dawn G. is a mom of two in southwest Missouri, where less than 45% of the population has been fully vaccinated. Her son turns 12 in early October, but in-person school started in mid-August.

“It was scary, thinking of him going to school for even 2 months,” she said. “Some parents thought their kid had a low chance of getting COVID, and their kid died. Nobody expects it to be them.”

In July, she and her husband took their son to a walk-in clinic and lied about his age.

“So many things can happen, from bullying to school shootings, and now this added pandemic risk,” she said. “I’ll do anything I can to protect my child, and a birthdate seems so arbitrary. He’ll be 12 in a matter of weeks. It seems ridiculous that that date would stop me from protecting him.”

In northern California, Carrie S. had a similar thought. When the vaccine was authorized for children ages 12-15 in May, the older of her two children got the shot right away. But her youngest doesn’t turn 12 until November.

“We were tempted to get the younger one vaccinated in May, but it didn’t seem like a rush. We were willing to wait to get the dosage right,” she ssaid. “But as Delta came through, there were no options for online school, the CDC was dropping mask expectations –it seemed like the world was ready to forget the pandemic was happening. It seemed like the least-bad option to get her vaccinated so she could go back to school, and we could find some balance of risk in our lives.”

Adult vs. pediatric doses

For now, experts advise against getting younger children vaccinated, even those who are the size of an adult, because of the way the human immune system develops.

“It’s not really about size,” said Anne Liu, MD, an immunologist and pediatrics professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The immune system behaves differently at different ages. Younger kids tend to have a more exuberant innate immune system, which is the part of the immune system that senses danger, even before it has developed a memory response.”

The adult Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine contains 30 mcg of mRNA, while the pediatric dose is just 10 mcg. That smaller dose produces an immune response similar to what’s seen in adults who receive 30 mcg, according to Pfizer.

“We were one of the sites that was involved in the phase 1 trial, a lot of times that’s called a dose-finding trial,” said Michael Smith, MD, a coinvestigator for the COVID vaccine trials done at Duke University. “And basically, if younger kids got a higher dose, they had more of a reaction, so it hurt more. They had fever, they had more redness and swelling at the site of the injection, and they just felt lousy, more than at the lower doses.”

At this point, with Pfizer’s data showing that younger children need a smaller dose, it doesn’t make sense to lie about your child’s age, said Dr. Smith.

“If my two options were having my child get the infection versus getting the vaccine, I’d get the vaccine. But we’re a few weeks away from getting the lower dose approved in kids,” he said. “It’s certainly safer. I don’t expect major, lifelong side effects from the higher dose, but it’s going to hurt, your kid’s going to have a fever, they’re going to feel lousy for a couple days, and they just don’t need that much antigen.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

One week after reporting promising results from the trial of their COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 5-11, Pfizer and BioNTech announced they’d submitted the data to the Food and Drug Administration. But that hasn’t stopped some parents from discreetly getting their children under age 12 vaccinated.

“The FDA, you never want to get ahead of their judgment,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC on Sept. 28. “But I would imagine in the next few weeks, they will examine that data and hopefully they’ll give the okay so that we can start vaccinating children, hopefully before the end of October.”

Lying to vaccinate now

More than half of all parents with children under 12 say they plan to get their kids vaccinated, according to a Gallup poll.

And although the FDA and the American Academy of Pediatrics have warned against it, some parents whose children can pass for 12 have lied to get them vaccinated already.

Dawn G. is a mom of two in southwest Missouri, where less than 45% of the population has been fully vaccinated. Her son turns 12 in early October, but in-person school started in mid-August.

“It was scary, thinking of him going to school for even 2 months,” she said. “Some parents thought their kid had a low chance of getting COVID, and their kid died. Nobody expects it to be them.”

In July, she and her husband took their son to a walk-in clinic and lied about his age.

“So many things can happen, from bullying to school shootings, and now this added pandemic risk,” she said. “I’ll do anything I can to protect my child, and a birthdate seems so arbitrary. He’ll be 12 in a matter of weeks. It seems ridiculous that that date would stop me from protecting him.”

In northern California, Carrie S. had a similar thought. When the vaccine was authorized for children ages 12-15 in May, the older of her two children got the shot right away. But her youngest doesn’t turn 12 until November.

“We were tempted to get the younger one vaccinated in May, but it didn’t seem like a rush. We were willing to wait to get the dosage right,” she ssaid. “But as Delta came through, there were no options for online school, the CDC was dropping mask expectations –it seemed like the world was ready to forget the pandemic was happening. It seemed like the least-bad option to get her vaccinated so she could go back to school, and we could find some balance of risk in our lives.”

Adult vs. pediatric doses

For now, experts advise against getting younger children vaccinated, even those who are the size of an adult, because of the way the human immune system develops.

“It’s not really about size,” said Anne Liu, MD, an immunologist and pediatrics professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The immune system behaves differently at different ages. Younger kids tend to have a more exuberant innate immune system, which is the part of the immune system that senses danger, even before it has developed a memory response.”

The adult Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine contains 30 mcg of mRNA, while the pediatric dose is just 10 mcg. That smaller dose produces an immune response similar to what’s seen in adults who receive 30 mcg, according to Pfizer.

“We were one of the sites that was involved in the phase 1 trial, a lot of times that’s called a dose-finding trial,” said Michael Smith, MD, a coinvestigator for the COVID vaccine trials done at Duke University. “And basically, if younger kids got a higher dose, they had more of a reaction, so it hurt more. They had fever, they had more redness and swelling at the site of the injection, and they just felt lousy, more than at the lower doses.”

At this point, with Pfizer’s data showing that younger children need a smaller dose, it doesn’t make sense to lie about your child’s age, said Dr. Smith.

“If my two options were having my child get the infection versus getting the vaccine, I’d get the vaccine. But we’re a few weeks away from getting the lower dose approved in kids,” he said. “It’s certainly safer. I don’t expect major, lifelong side effects from the higher dose, but it’s going to hurt, your kid’s going to have a fever, they’re going to feel lousy for a couple days, and they just don’t need that much antigen.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

One week after reporting promising results from the trial of their COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 5-11, Pfizer and BioNTech announced they’d submitted the data to the Food and Drug Administration. But that hasn’t stopped some parents from discreetly getting their children under age 12 vaccinated.

“The FDA, you never want to get ahead of their judgment,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told MSNBC on Sept. 28. “But I would imagine in the next few weeks, they will examine that data and hopefully they’ll give the okay so that we can start vaccinating children, hopefully before the end of October.”

Lying to vaccinate now

More than half of all parents with children under 12 say they plan to get their kids vaccinated, according to a Gallup poll.

And although the FDA and the American Academy of Pediatrics have warned against it, some parents whose children can pass for 12 have lied to get them vaccinated already.

Dawn G. is a mom of two in southwest Missouri, where less than 45% of the population has been fully vaccinated. Her son turns 12 in early October, but in-person school started in mid-August.

“It was scary, thinking of him going to school for even 2 months,” she said. “Some parents thought their kid had a low chance of getting COVID, and their kid died. Nobody expects it to be them.”

In July, she and her husband took their son to a walk-in clinic and lied about his age.

“So many things can happen, from bullying to school shootings, and now this added pandemic risk,” she said. “I’ll do anything I can to protect my child, and a birthdate seems so arbitrary. He’ll be 12 in a matter of weeks. It seems ridiculous that that date would stop me from protecting him.”

In northern California, Carrie S. had a similar thought. When the vaccine was authorized for children ages 12-15 in May, the older of her two children got the shot right away. But her youngest doesn’t turn 12 until November.

“We were tempted to get the younger one vaccinated in May, but it didn’t seem like a rush. We were willing to wait to get the dosage right,” she ssaid. “But as Delta came through, there were no options for online school, the CDC was dropping mask expectations –it seemed like the world was ready to forget the pandemic was happening. It seemed like the least-bad option to get her vaccinated so she could go back to school, and we could find some balance of risk in our lives.”

Adult vs. pediatric doses

For now, experts advise against getting younger children vaccinated, even those who are the size of an adult, because of the way the human immune system develops.

“It’s not really about size,” said Anne Liu, MD, an immunologist and pediatrics professor at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The immune system behaves differently at different ages. Younger kids tend to have a more exuberant innate immune system, which is the part of the immune system that senses danger, even before it has developed a memory response.”

The adult Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine contains 30 mcg of mRNA, while the pediatric dose is just 10 mcg. That smaller dose produces an immune response similar to what’s seen in adults who receive 30 mcg, according to Pfizer.

“We were one of the sites that was involved in the phase 1 trial, a lot of times that’s called a dose-finding trial,” said Michael Smith, MD, a coinvestigator for the COVID vaccine trials done at Duke University. “And basically, if younger kids got a higher dose, they had more of a reaction, so it hurt more. They had fever, they had more redness and swelling at the site of the injection, and they just felt lousy, more than at the lower doses.”

At this point, with Pfizer’s data showing that younger children need a smaller dose, it doesn’t make sense to lie about your child’s age, said Dr. Smith.

“If my two options were having my child get the infection versus getting the vaccine, I’d get the vaccine. But we’re a few weeks away from getting the lower dose approved in kids,” he said. “It’s certainly safer. I don’t expect major, lifelong side effects from the higher dose, but it’s going to hurt, your kid’s going to have a fever, they’re going to feel lousy for a couple days, and they just don’t need that much antigen.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

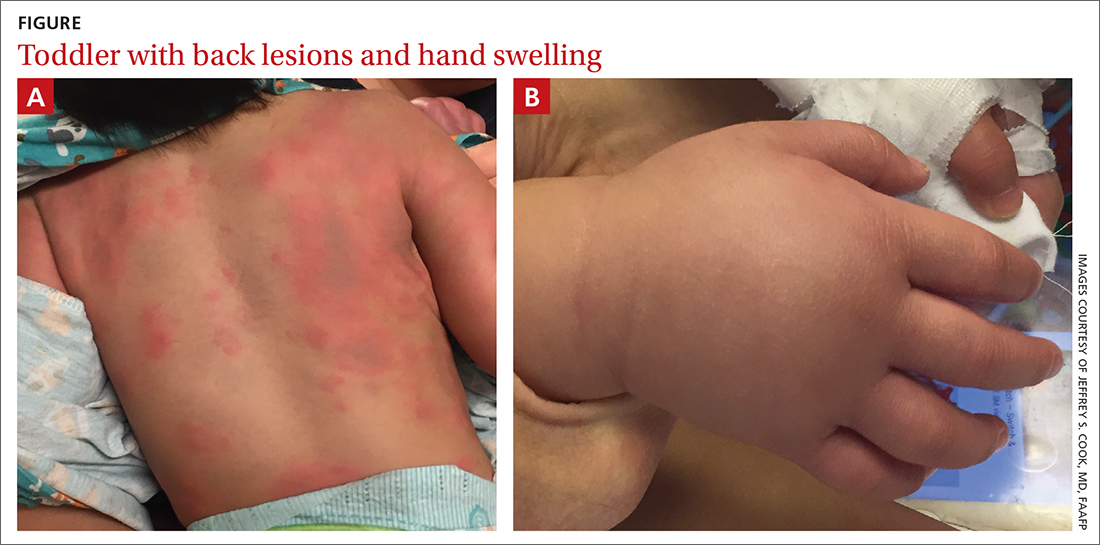

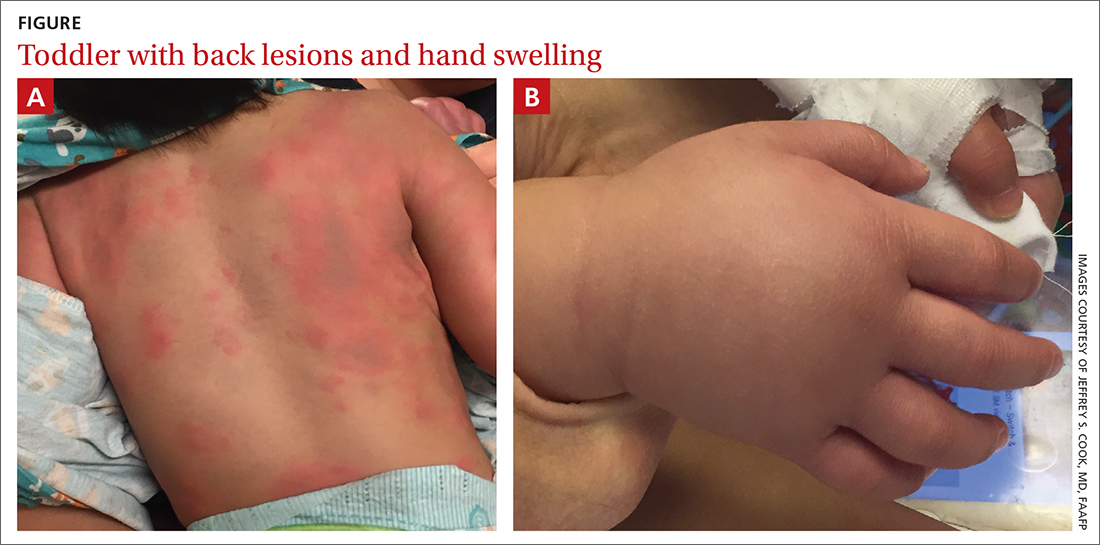

Urticaria and edema in a 2-year-old boy

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the emergency room with a 1-day history of a diffuse, mildly pruritic rash and swelling of his knees, ankles, and feet following treatment of acute otitis media with amoxicillin for the previous 8 days. He was mildly febrile and consolable, but he was refusing to walk. His medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed erythematous annular wheals on his chest, face, back, and extremities. Lymphadenopathy and mucous membrane involvement were not present. A complete blood count (CBC) with differential, inflammatory marker tests, and a comprehensive metabolic panel were ordered. Given the joint swelling and rash, the patient was admitted for observation.

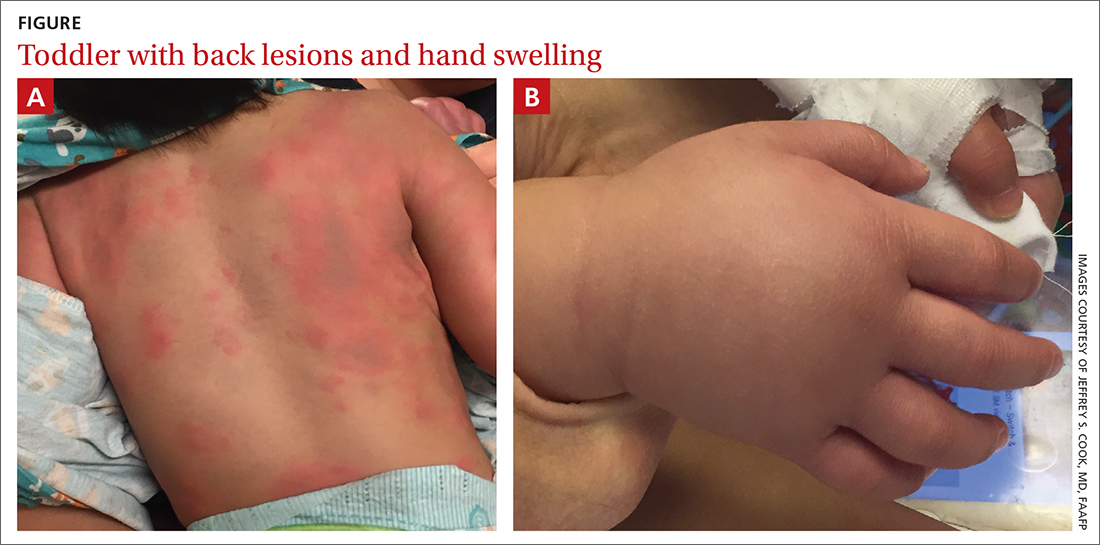

During his second day in the hospital, his skin lesions enlarged and several formed dusky blue centers (FIGURE 1A). He also developed swelling of his hands (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

The patient’s lab work came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. The incidence and prevalence are not known. Urticaria multiforme is considered common, but it is frequently misdiagnosed.1 It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 Individual lesions last less than 24 hours, but new ones may appear. The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Dermatographism due to mast cell–mediated cutaneous hypersensitivity at sites of minor skin trauma is common (44%).

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing.When performed, laboratory studies, including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis are routinely normal.

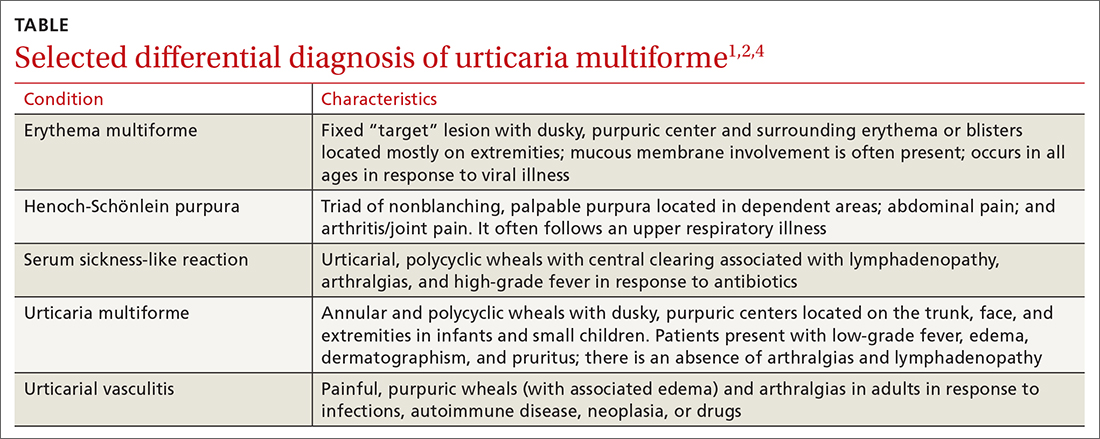

Erythema multiforme and urticarial vasculitis are part of the differential

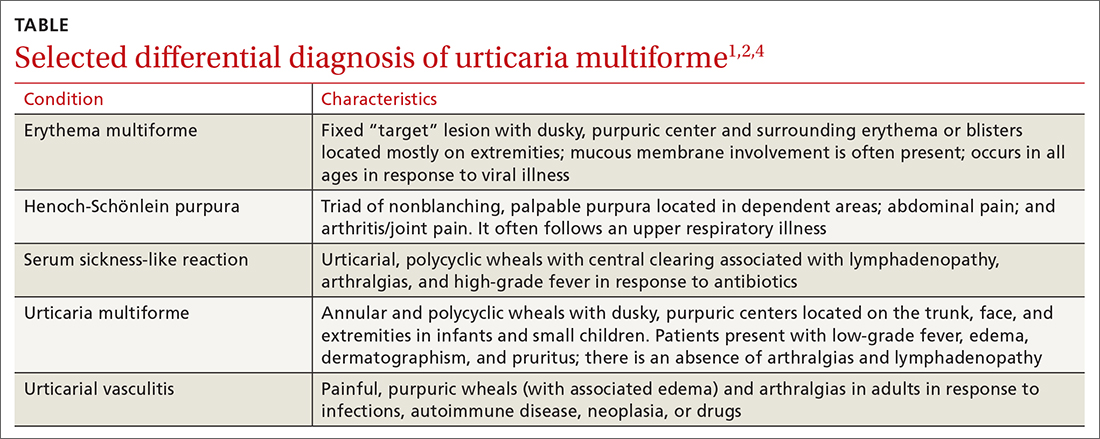

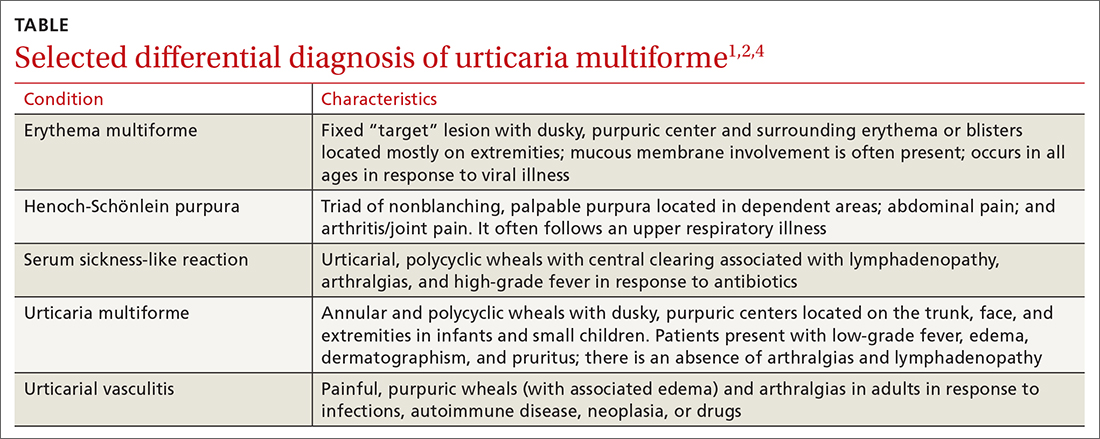

The differential diagnosis in this case includes erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis (TABLE1,2,4).

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a common misdiagnosis in patients with urticaria multiforme.1,2 The erythema multiforme rash has a “target” lesion with outer erythema and central ecchymosis, which may develop blisters or necrosis. Lesions are fixed and last 2 to 3 weeks. Unlike urticaria multiforme, patients with erythema multiforme commonly have mucous membrane erosions and occasionally ulcerations. Facial and acral edema is rare. Treatment is largely symptomatic and can include glucocorticoids. Antiviral medications may be used to treat recurrences.1,2

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an immunoglobulin A–mediated vasculitis that affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and joints.4,5 Patients often present with arthralgias, gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain and bleeding, and a nonpruritic, erythematous rash that progresses to palpable purpura in dependent areas of the body. Treatment is generally symptomatic, but steroids may be used in severe cases.4,5

Serum sickness-like reaction can manifest with angioedema and a similar urticarial rash (with central clearing) that lasts 1 to 6 weeks.1,2,6,7 However, patients tend to have a high-grade fever, arthralgias, myalgias, and lymphadenopathy while dermatographism is absent. Treatment includes discontinuing the offending agent and the use of H1 and H2 antihistamines and steroids, in severe cases.

Urticarial vasculitis manifests as plaques or wheals lasting 1 to 7 days that may cause burning and pain but not pruritis.2,5 Purpura or hypopigmentation may develop as the hives resolve. Angioedema and arthralgias are common, but dermatographism is not present. Triggers include infections, autoimmune disease, malignancy, and the use of certain medications. H1 and H2 blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are first-line therapy.2

Step 1: Discontinue offending agents; Step 2: Recommend antihistamines

Treatment consists of discontinuing any offending agent (if suspected) and using systemic H1 or H2 antihistamines for symptom relief. Systemic steroids should only be given in refractory cases.

Continue to: Our patient's amoxicillin

Our patient’s amoxicillin was discontinued, and he was started on a 14-day course of cetirizine 5 mg bid and hydroxyzine 10 mg at bedtime. He was also started on triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily for 1 week. During his 3-day hospital stay, his fever resolved and his rash and edema improved.

During an outpatient follow-up visit with a pediatric dermatologist 2 weeks after discharge, the patient’s rash was still present and dermatographism was noted. In light of this, his parents were instructed to continue giving the cetirizine and hydroxyzine once daily for an additional 2 weeks and to return as needed.

1. Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. “Urticaria multiforme”: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1553

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Starnes L, Patel T, Skinner RB. Urticaria multiforme – a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:436-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01311.x

4. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

5. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby, Elsevier Inc; 2016.

6. King BA, Geelhoed GC. Adverse skin and joint reactions associated with oral antibiotics in children: the role of cefaclor in serum sickness-like reactions. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:677-681. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00267.x

7. Misirlioglu ED, Duman H, Ozmen S, et al. Serum sickness-like reaction in children due to cefditoren. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;29:327-328. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01539.x

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the emergency room with a 1-day history of a diffuse, mildly pruritic rash and swelling of his knees, ankles, and feet following treatment of acute otitis media with amoxicillin for the previous 8 days. He was mildly febrile and consolable, but he was refusing to walk. His medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed erythematous annular wheals on his chest, face, back, and extremities. Lymphadenopathy and mucous membrane involvement were not present. A complete blood count (CBC) with differential, inflammatory marker tests, and a comprehensive metabolic panel were ordered. Given the joint swelling and rash, the patient was admitted for observation.

During his second day in the hospital, his skin lesions enlarged and several formed dusky blue centers (FIGURE 1A). He also developed swelling of his hands (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

The patient’s lab work came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. The incidence and prevalence are not known. Urticaria multiforme is considered common, but it is frequently misdiagnosed.1 It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 Individual lesions last less than 24 hours, but new ones may appear. The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Dermatographism due to mast cell–mediated cutaneous hypersensitivity at sites of minor skin trauma is common (44%).

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing.When performed, laboratory studies, including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis are routinely normal.

Erythema multiforme and urticarial vasculitis are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis (TABLE1,2,4).

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a common misdiagnosis in patients with urticaria multiforme.1,2 The erythema multiforme rash has a “target” lesion with outer erythema and central ecchymosis, which may develop blisters or necrosis. Lesions are fixed and last 2 to 3 weeks. Unlike urticaria multiforme, patients with erythema multiforme commonly have mucous membrane erosions and occasionally ulcerations. Facial and acral edema is rare. Treatment is largely symptomatic and can include glucocorticoids. Antiviral medications may be used to treat recurrences.1,2

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an immunoglobulin A–mediated vasculitis that affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and joints.4,5 Patients often present with arthralgias, gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain and bleeding, and a nonpruritic, erythematous rash that progresses to palpable purpura in dependent areas of the body. Treatment is generally symptomatic, but steroids may be used in severe cases.4,5

Serum sickness-like reaction can manifest with angioedema and a similar urticarial rash (with central clearing) that lasts 1 to 6 weeks.1,2,6,7 However, patients tend to have a high-grade fever, arthralgias, myalgias, and lymphadenopathy while dermatographism is absent. Treatment includes discontinuing the offending agent and the use of H1 and H2 antihistamines and steroids, in severe cases.

Urticarial vasculitis manifests as plaques or wheals lasting 1 to 7 days that may cause burning and pain but not pruritis.2,5 Purpura or hypopigmentation may develop as the hives resolve. Angioedema and arthralgias are common, but dermatographism is not present. Triggers include infections, autoimmune disease, malignancy, and the use of certain medications. H1 and H2 blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are first-line therapy.2

Step 1: Discontinue offending agents; Step 2: Recommend antihistamines

Treatment consists of discontinuing any offending agent (if suspected) and using systemic H1 or H2 antihistamines for symptom relief. Systemic steroids should only be given in refractory cases.

Continue to: Our patient's amoxicillin

Our patient’s amoxicillin was discontinued, and he was started on a 14-day course of cetirizine 5 mg bid and hydroxyzine 10 mg at bedtime. He was also started on triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily for 1 week. During his 3-day hospital stay, his fever resolved and his rash and edema improved.

During an outpatient follow-up visit with a pediatric dermatologist 2 weeks after discharge, the patient’s rash was still present and dermatographism was noted. In light of this, his parents were instructed to continue giving the cetirizine and hydroxyzine once daily for an additional 2 weeks and to return as needed.

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the emergency room with a 1-day history of a diffuse, mildly pruritic rash and swelling of his knees, ankles, and feet following treatment of acute otitis media with amoxicillin for the previous 8 days. He was mildly febrile and consolable, but he was refusing to walk. His medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed erythematous annular wheals on his chest, face, back, and extremities. Lymphadenopathy and mucous membrane involvement were not present. A complete blood count (CBC) with differential, inflammatory marker tests, and a comprehensive metabolic panel were ordered. Given the joint swelling and rash, the patient was admitted for observation.

During his second day in the hospital, his skin lesions enlarged and several formed dusky blue centers (FIGURE 1A). He also developed swelling of his hands (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

The patient’s lab work came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. The incidence and prevalence are not known. Urticaria multiforme is considered common, but it is frequently misdiagnosed.1 It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 Individual lesions last less than 24 hours, but new ones may appear. The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Dermatographism due to mast cell–mediated cutaneous hypersensitivity at sites of minor skin trauma is common (44%).

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing.When performed, laboratory studies, including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis are routinely normal.

Erythema multiforme and urticarial vasculitis are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis (TABLE1,2,4).

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a common misdiagnosis in patients with urticaria multiforme.1,2 The erythema multiforme rash has a “target” lesion with outer erythema and central ecchymosis, which may develop blisters or necrosis. Lesions are fixed and last 2 to 3 weeks. Unlike urticaria multiforme, patients with erythema multiforme commonly have mucous membrane erosions and occasionally ulcerations. Facial and acral edema is rare. Treatment is largely symptomatic and can include glucocorticoids. Antiviral medications may be used to treat recurrences.1,2

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an immunoglobulin A–mediated vasculitis that affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and joints.4,5 Patients often present with arthralgias, gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain and bleeding, and a nonpruritic, erythematous rash that progresses to palpable purpura in dependent areas of the body. Treatment is generally symptomatic, but steroids may be used in severe cases.4,5

Serum sickness-like reaction can manifest with angioedema and a similar urticarial rash (with central clearing) that lasts 1 to 6 weeks.1,2,6,7 However, patients tend to have a high-grade fever, arthralgias, myalgias, and lymphadenopathy while dermatographism is absent. Treatment includes discontinuing the offending agent and the use of H1 and H2 antihistamines and steroids, in severe cases.

Urticarial vasculitis manifests as plaques or wheals lasting 1 to 7 days that may cause burning and pain but not pruritis.2,5 Purpura or hypopigmentation may develop as the hives resolve. Angioedema and arthralgias are common, but dermatographism is not present. Triggers include infections, autoimmune disease, malignancy, and the use of certain medications. H1 and H2 blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are first-line therapy.2

Step 1: Discontinue offending agents; Step 2: Recommend antihistamines

Treatment consists of discontinuing any offending agent (if suspected) and using systemic H1 or H2 antihistamines for symptom relief. Systemic steroids should only be given in refractory cases.

Continue to: Our patient's amoxicillin

Our patient’s amoxicillin was discontinued, and he was started on a 14-day course of cetirizine 5 mg bid and hydroxyzine 10 mg at bedtime. He was also started on triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily for 1 week. During his 3-day hospital stay, his fever resolved and his rash and edema improved.

During an outpatient follow-up visit with a pediatric dermatologist 2 weeks after discharge, the patient’s rash was still present and dermatographism was noted. In light of this, his parents were instructed to continue giving the cetirizine and hydroxyzine once daily for an additional 2 weeks and to return as needed.

1. Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. “Urticaria multiforme”: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1553

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Starnes L, Patel T, Skinner RB. Urticaria multiforme – a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:436-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01311.x

4. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

5. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby, Elsevier Inc; 2016.

6. King BA, Geelhoed GC. Adverse skin and joint reactions associated with oral antibiotics in children: the role of cefaclor in serum sickness-like reactions. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:677-681. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00267.x

7. Misirlioglu ED, Duman H, Ozmen S, et al. Serum sickness-like reaction in children due to cefditoren. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;29:327-328. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01539.x

1. Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. “Urticaria multiforme”: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1553

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Starnes L, Patel T, Skinner RB. Urticaria multiforme – a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:436-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01311.x

4. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

5. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby, Elsevier Inc; 2016.

6. King BA, Geelhoed GC. Adverse skin and joint reactions associated with oral antibiotics in children: the role of cefaclor in serum sickness-like reactions. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:677-681. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00267.x

7. Misirlioglu ED, Duman H, Ozmen S, et al. Serum sickness-like reaction in children due to cefditoren. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;29:327-328. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01539.x

Strategies to identify and prevent penicillin allergy mislabeling and appropriately de-label patients

In North America and Europe, penicillin allergy is the most common drug-allergy label.1 Carrying a penicillin-allergy label, which has recently gained more attention in health care systems, leads to suboptimal outcomes, increased use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, increased risk of adverse reactions, and increased cost of care.2,3 Despite the high rate of reported reactions, clinically significant immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated and T cell–mediated hypersensitivity reactions to penicillins are uncommon.2

Through the Choosing Wisely initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology has issued a recommendation: “Don’t overuse non-beta lactam antibiotics in patients with a history of penicillin allergy without an appropriate evaluation.”4 The primary care physician (PCP) plays a critical role in the appropriate evaluation and accurate initial labeling of penicillin allergy. Furthermore, the PCP plays an integral part, in conjunction with the allergist, in removing the “penicillin allergy” label from a patient’s chart when feasible.

The history of penicillin and prevalence of allergy

History. Penicillin, the first antibiotic, was discovered in 1928 by physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming when he observed that a mold of the Penicillium genus inhibited growth of gram-positive pathogens.5 Along with pharmacologist Howard Florey and chemist Ernst Chain, both of whom assisted in the large-scale isolation and production of the antibiotic, Fleming won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 for this discovery.5

Antibiotics transformed the practice of medicine across a spectrum, including safer childbirth, surgical procedures, and transplantation.6 Penicillin remains first-line therapy for many infections, such as streptococcal pharyngitis,7 and is the only recommended medication for treating syphilis during pregnancy.8 Continued effectiveness of penicillin in these cases allows broad-spectrum antibiotics to be reserved for more severe infections. Regrettably, incorrect antibiotic allergy labeling poses a significant risk to the patient and health care system.

Epidemiology. As with all medications, the potential for anaphylaxis exists after administration of penicillin. Because its use is widespread, penicillin is the most common cause of drug-induced anaphylaxis. However, the incidence of penicillin-induced anaphylaxis is low9: A 1968 World Health Organization report stated that the rate of penicillin anaphylaxis was between 0.015% and 0.04%.10 A more recent study reported an incidence of 1 in 207,191 patients after an oral dose and 1 in 95,298 after a parenteral dose.11 The most common reactions to penicillins are urticaria and delayed maculopapular rash.8

In the United States, the prevalence of reported penicillin allergy is approximately 10% (estimated range, 8% to 12%)3,12-15; among hospitalized patients, that prevalence is estimated to be as high as 15%.13,15 However, the prevalence of confirmed penicillin allergy is low and has decreased over time—demonstrated in a longitudinal study in which the rate of a positive skin test fell from 15% in 1995 to 0.8% in 2013.16,17

Studies have confirmed that as many as 90% of patients who report penicillin allergy are, in fact, able to tolerate penicillins.14,18-20 This finding might be a consequence of initial mislabeling of penicillin allergy; often, adverse reactions are documented as “allergy” when no risk of anaphylaxis exists. Furthermore, patients can outgrow IgE-mediated penicillin allergy because the presence of penicillin IgE antibodies wanes over time.14,15

Continue to: Consequences of mislabeling

Consequences of mislabeling

Clinical consequences. A multitude of clinical consequences result from carrying a “penicillin allergy” label.

Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics leads to increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection and to development of resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus.2,15

Alternative antibiotics used in the setting of a “penicillin allergy” label might be less efficacious and result in suboptimal outcomes. For example, vancomycin is less effective against methicillin-sensitive S aureus bacteremia than nafcillin or cefazolin.2,21 Beta-lactam antibiotics—in particular, cefazolin—are often first-line for perioperative prophylaxis; patients with reported penicillin allergy often receive a less-optimal alternative, such as clindamycin, vancomycin, or gentamicin.22 These patients are at increased risk of surgical site infection.2,22

In addition, using penicillin alternatives can result in greater risk of drug reactions and adverse effects.2

Increased health care costs. Primarily through observational studies, penicillin allergy has been associated with higher health care costs.23 Patients with reported penicillin allergy had, on average, a longer inpatient stay than patients without penicillin allergy, at a 3-year total estimated additional cost of $64.6 million.24 Inpatients with a listed penicillin allergy had direct drug costs ranging from “no difference” to $609 per patient more than patients without a listed penicillin allergy. Outpatient prescription costs were $14 to $193 higher per patient for patients with a listed penicillin allergy.23

Continue to: Considerations in special populations

Considerations in special populations. Evaluating penicillin allergy during routine care is key to decreasing the necessity for urgent penicillin evaluation and possible desensitization at the time of serious infection. Certain patient populations pose specific challenges:

- Pregnant patients. Unverified penicillin allergy during pregnancy is associated with an increased rate of cesarean section and longer postpartum hospitalization.25 Additionally, group B streptococcus-positive women have increased exposure to alternative antibiotics and an increased incidence of adverse drug reactions.25

- Elderly patients. Drug allergy increases with aging.1 Elderly patients in a long-term care facility are more likely to experience adverse drug effects or drug–drug interactions from the use of penicillin alternatives, such as clindamycin, vancomycin, and fluoroquinolones.2

- Oncology patients often require antibiotic prophylaxis as well as treatment for illnesses, such as neutropenic fever, for which beta-lactam antibiotics are often used as initial treatment.2,26

- Other important populations that present specific challenges include hospitalized patients, pediatric patients, and patients with a sexually transmitted infection.2

Active management of a penicillin-allergy label

Greater recognition of the consequences of penicillin allergy in recent years has led to efforts by hospitals and other health care organizations to develop processes by which patients can be successfully de-labeled as part of antibiotic stewardship programs9 and other initiatives. Ideally, every patient who has a “penicillin allergy” label would be referred to an allergist for evaluation; however, the number of allergy specialists is limited, and access to such specialists might be restricted in some areas, making this approach impracticable. Active management of penicillin allergy requires strategies to both test and de-label patients, as well as proactive approaches to prevent incorrect labeling. These proactive approaches require involvement of all members of the health care team—especially PCPs.

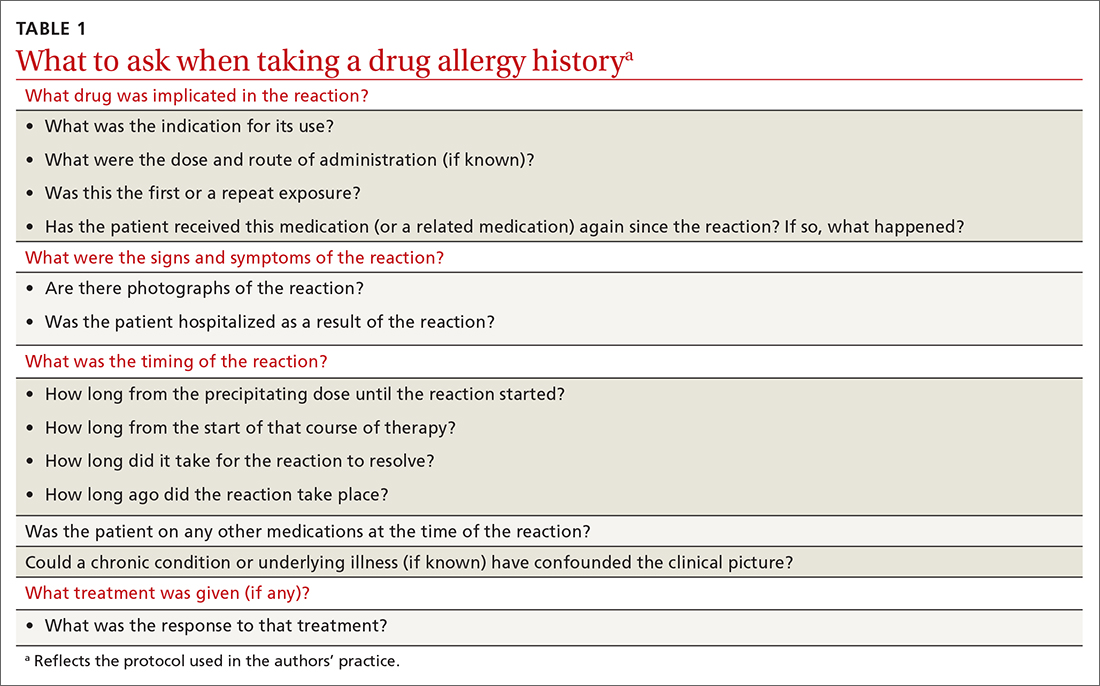

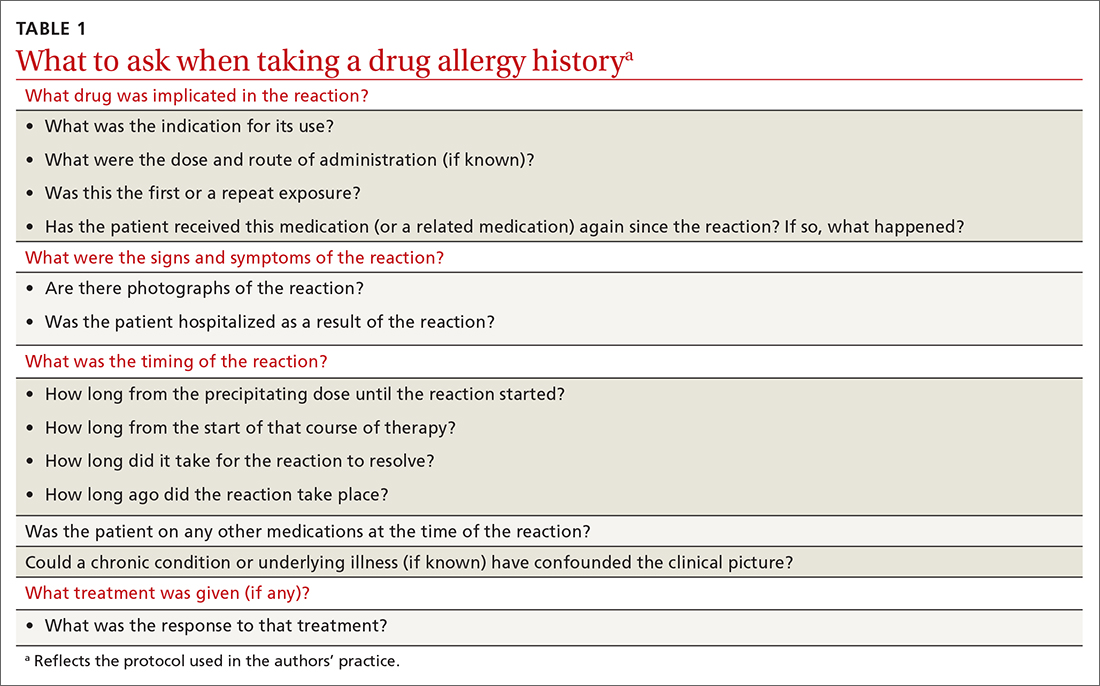

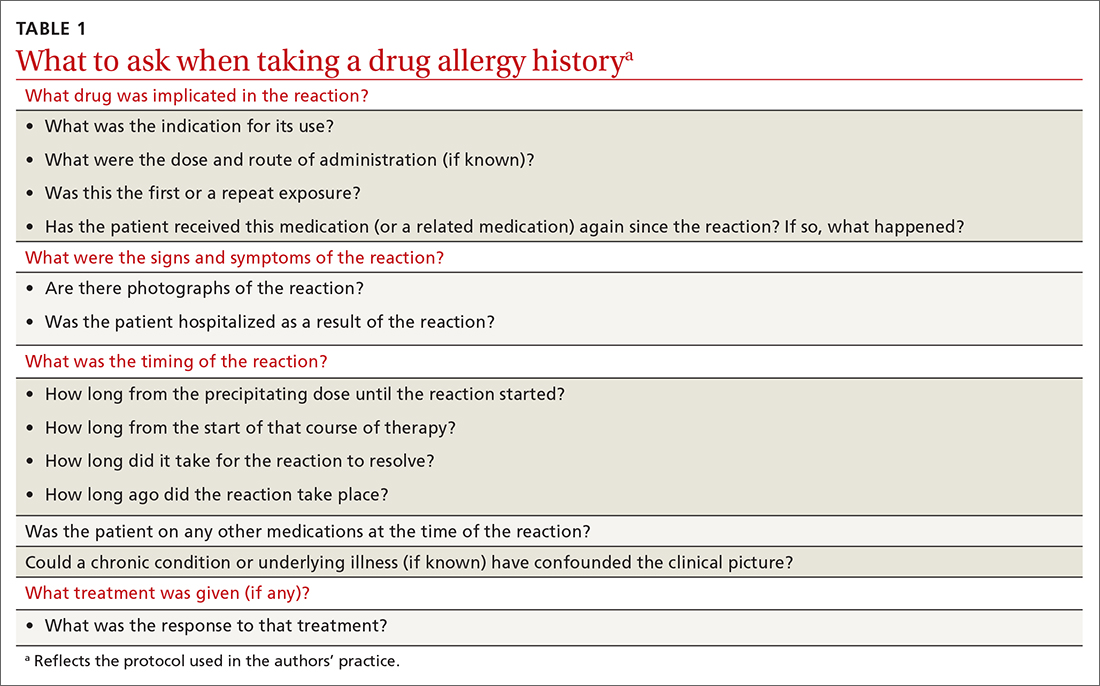

Preventing incorrect labeling. PCPs are the most likely to initially label a patient as allergic to penicillin.27 Most physicians rely on a reported history of allergy alone when selecting medication12; once a patient has been labeled “penicillin allergic,” they often retain that mislabel through adulthood.27,28 A qualitative study of PCPs’ views on prescribing penicillin found that many were aware that documented allergies were incorrect but were uncomfortable using their clinical judgment to prescribe a penicillin or change the record, for fear of a future anaphylactic reaction.29 The first step in the case of any reported reaction should be for you to elicit an accurate drug allergy history (TABLE 1).

As with other drug reactions, you should consider the context surrounding the reaction to a penicillin. Take care to review signs and symptoms of the reaction to look for clues that make a true allergic reaction more, or less, likely.

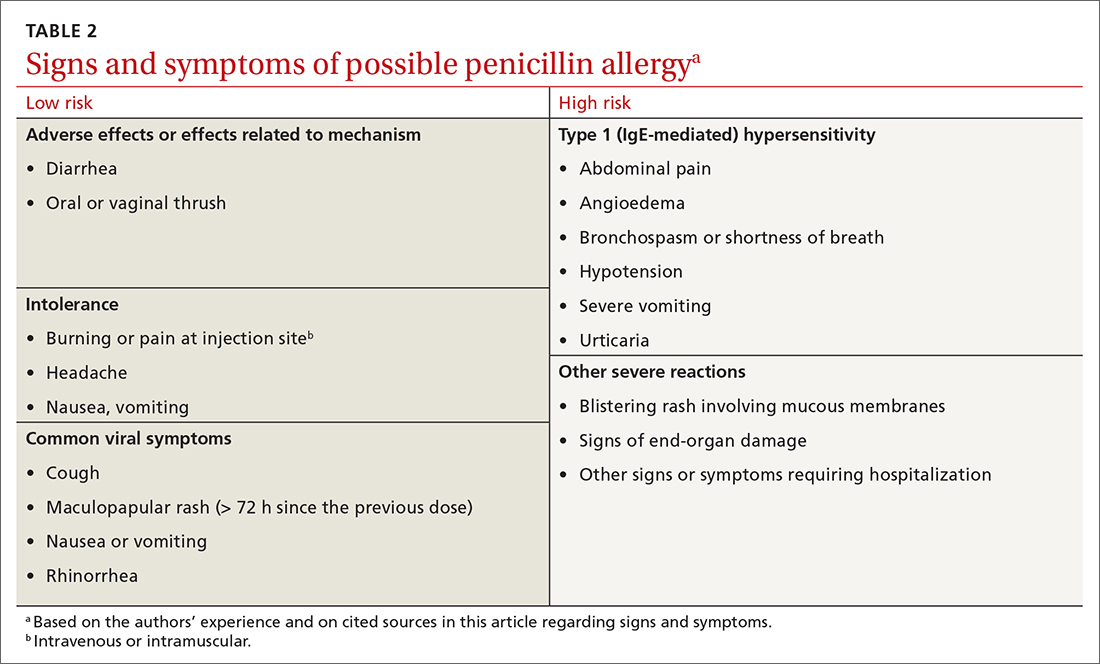

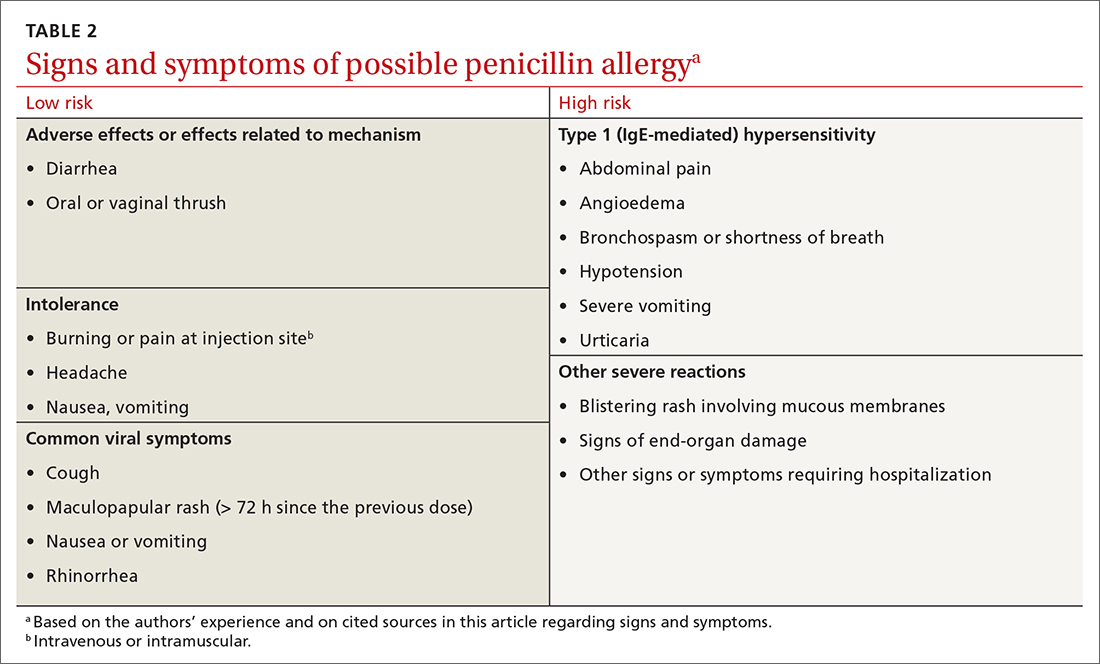

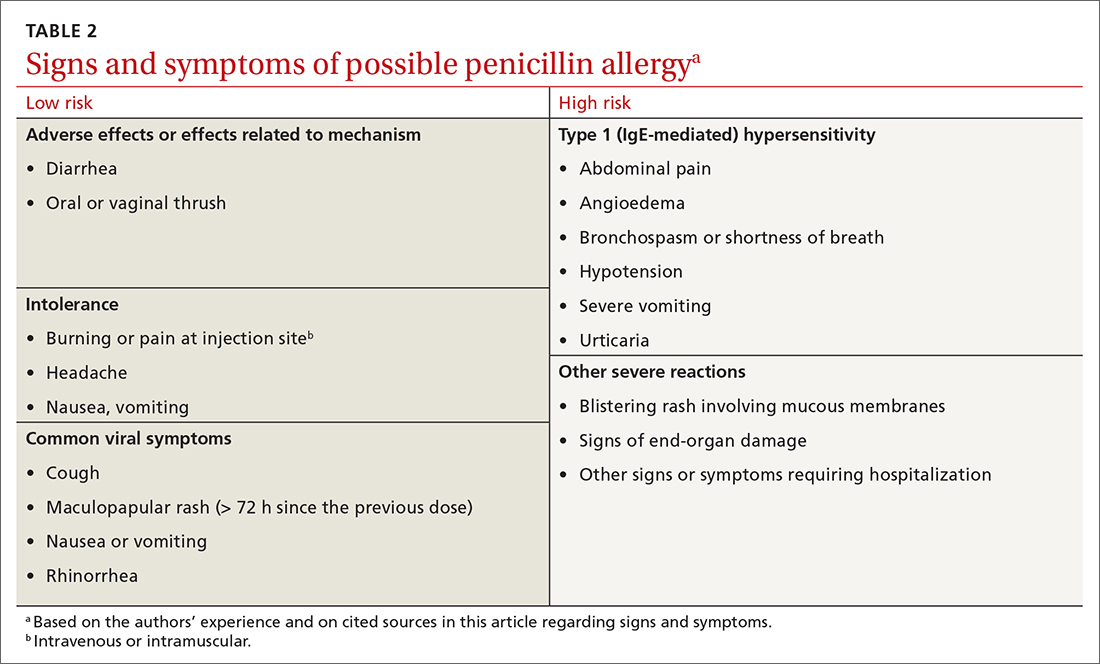

Symptoms can generally be divided into low-risk and high-risk categories27 (TABLE 2). An example of a commonly reported low-risk symptom is diarrhea that develops after several doses of a penicillin. In the absence of other symptoms, this finding is most likely due to elimination of normal gut flora,30 not to an allergic reaction to the medication. Symptoms of intolerance to the medication, such as headache and nausea, are also low risk.27,31 In contrast, immediate onset of abdominal pain after a dose of penicillin and lip or throat swelling are considered high risk.

Continue to: Patients presenting with urticaria...

Patients presenting with urticaria or maculopapular rash after taking penicillin are particularly challenging.30 A study of patients in a primary care pediatrics practice found that 7.4% of children receiving a prescription for a penicillin reported a rash.32 Here, timing of onset of symptoms provides some clarity about the likelihood of true allergy. Rashes that manifest during the first hours after exposure are more likely to be IgE mediated, particularly when accompanied by other systemic symptoms; they should be considered high risk. Delayed-onset rashes (> 72 hours after exposure) are usually non-IgE mediated and therefore are generally lower risk,8,30,33 except when associated with certain features, such as mucosal involvement and skin peeling.

Despite acknowledging viral exanthems in the differential, many physicians still label patients presenting with any rash as “allergic.”28 Take care to look for other potential causes of a rash; for example, patients taking amoxicillin who have concurrent Epstein-Barr virus infection frequently develop a maculopapular rash.34 Caubet and colleagues found that 56% of pediatric patients with a history of nonimmediate rash and a negative oral challenge to amoxicillin tested positive for viral infection.28

A family history of penicillin allergy alone should not preclude the use of penicillin.8,27,31 Similarly, if a patient has already received and tolerated a subsequent course of the same penicillin derivative after the initial reaction, the “penicillin allergy” label can be removed. If the reaction history is unknown, refer the patient to an allergist for further evaluation.

Accurate charting is key. With most hospital systems and physician practices now documenting in an electronic health record, there exists the ability to document, in great detail, patients’ reactions to medications. Previous studies have found, however, that such documentation is often done poorly, or not done at all. One such study found that (1) > 20% of patients with a “penicillin allergy” label did not have reaction details listed and (2) when reactions were listed, many were incorrectly labeled as “allergy,” not “intolerance.”35

Many electronic health record systems lump drug allergies, adverse effects, and food and environmental allergies into a single section, leading to a lack of distinction between adverse reactions and true allergy.31 Although many PCPs report that it is easy to change a patient’s allergy label in the record,29 more often, a nurse, resident, or consultant actually documents the reaction.35

Continue to: Documentation at the time of the reaction...

Documentation at the time of the reaction, within the encounter note and the allergy tab, is essential, so that other physicians caring for the patient, in the future, will be knowledgeable about the details of the reaction. Make it your responsibility to accurately document penicillin allergy in patients’ charts, including removing the “penicillin allergy” label from the chart of patients whose history is inconsistent with allergy, who have tolerated subsequent courses of the same penicillin derivative, or who have passed testing in an allergist’s office. In a study of 639 patients who tested negative for penicillin allergy, 51% still had a “penicillin allergy” label in their chart more than 4 years later.36

Penicillin allergy evaluation. When a patient cannot be cleared of a “penicillin allergy” label by history alone, and in the absence of severe features such as mucous membrane involvement, they should be further evaluated through objective testing for potential IgE-mediated allergy. This assessment includes penicillin skin testing or an oral challenge, or both.

Skin testing involves skin-prick testing of major and minor determinants of penicillin; when skin-prick testing is negative, intradermal testing of major and minor determinants should follow. The negative predictive value of penicillin skin testing is high: In a prospective, multicenter investigation, researchers demonstrated that, when both the major penicillin determinant and a minor determinant mixture were used, negative predictive value was 97.9%.37

However, a minor determinant mixture is not commercially available in the United States; therefore, penicillin G is often used alone as the minor determinant. Typically, if a patient passes skin testing, a challenge dose of penicillin or amoxicillin is administered, followed by an observation period. The risk of re-sensitization after oral penicillin is thought to be low and does not preclude future use.38

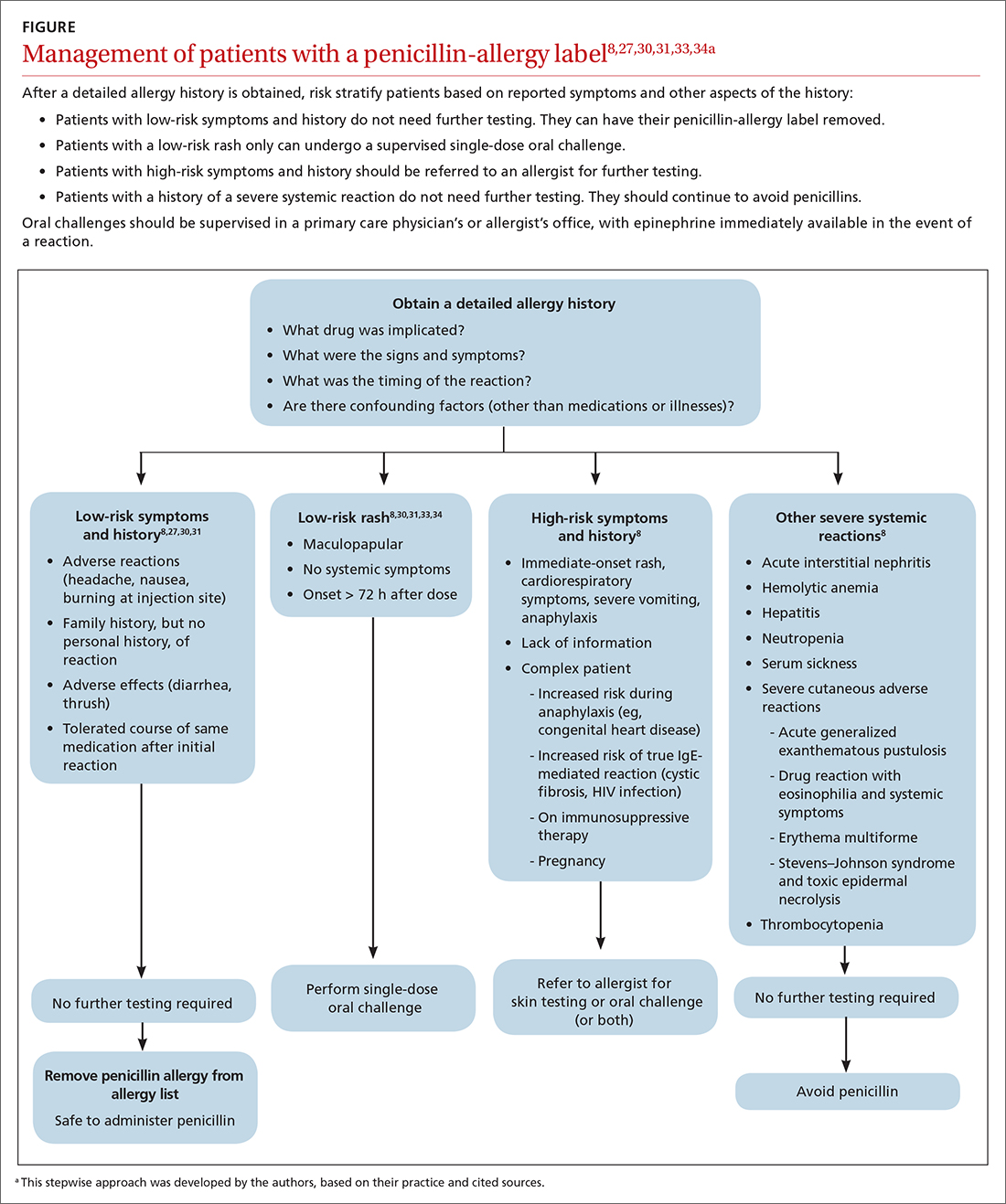

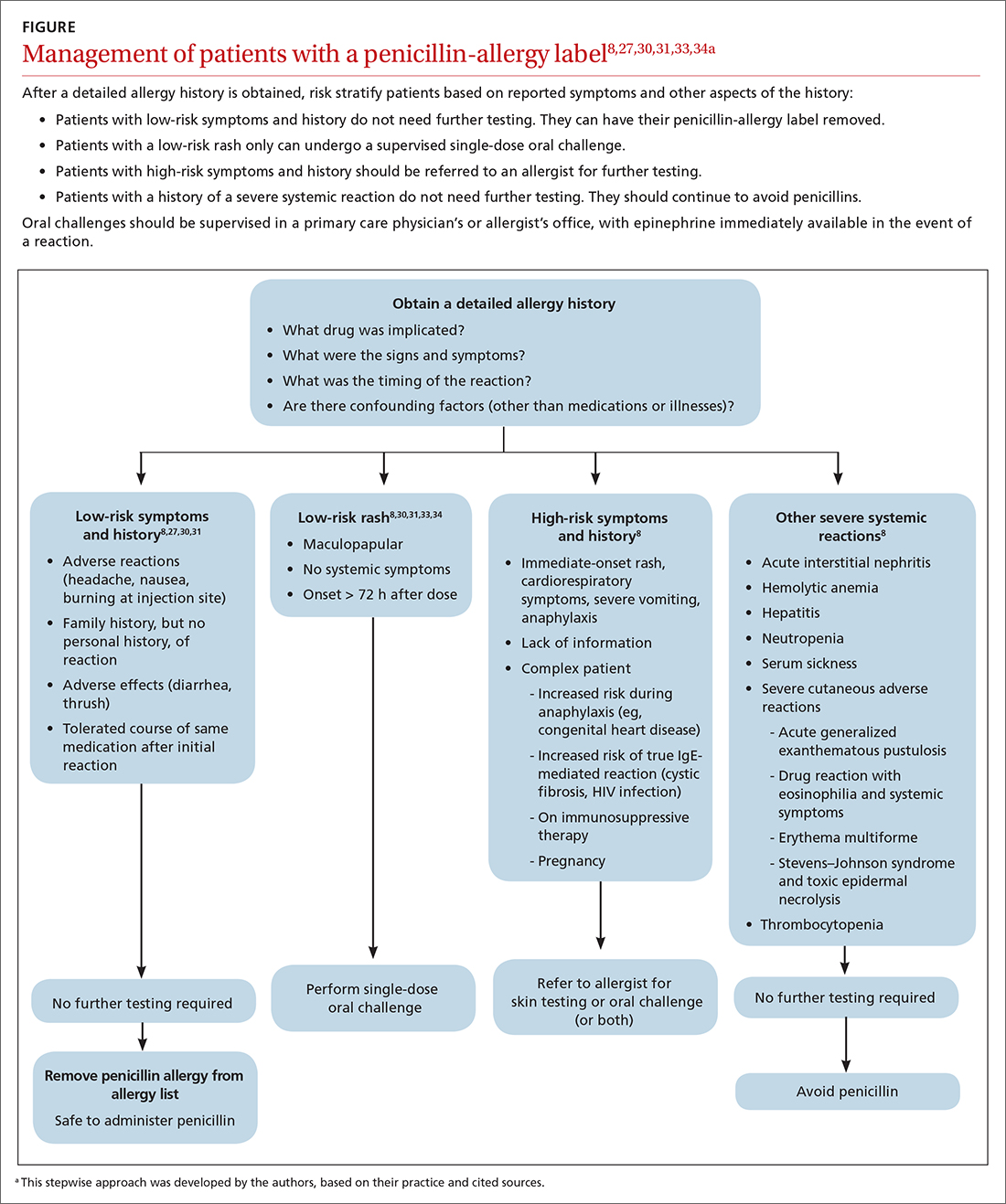

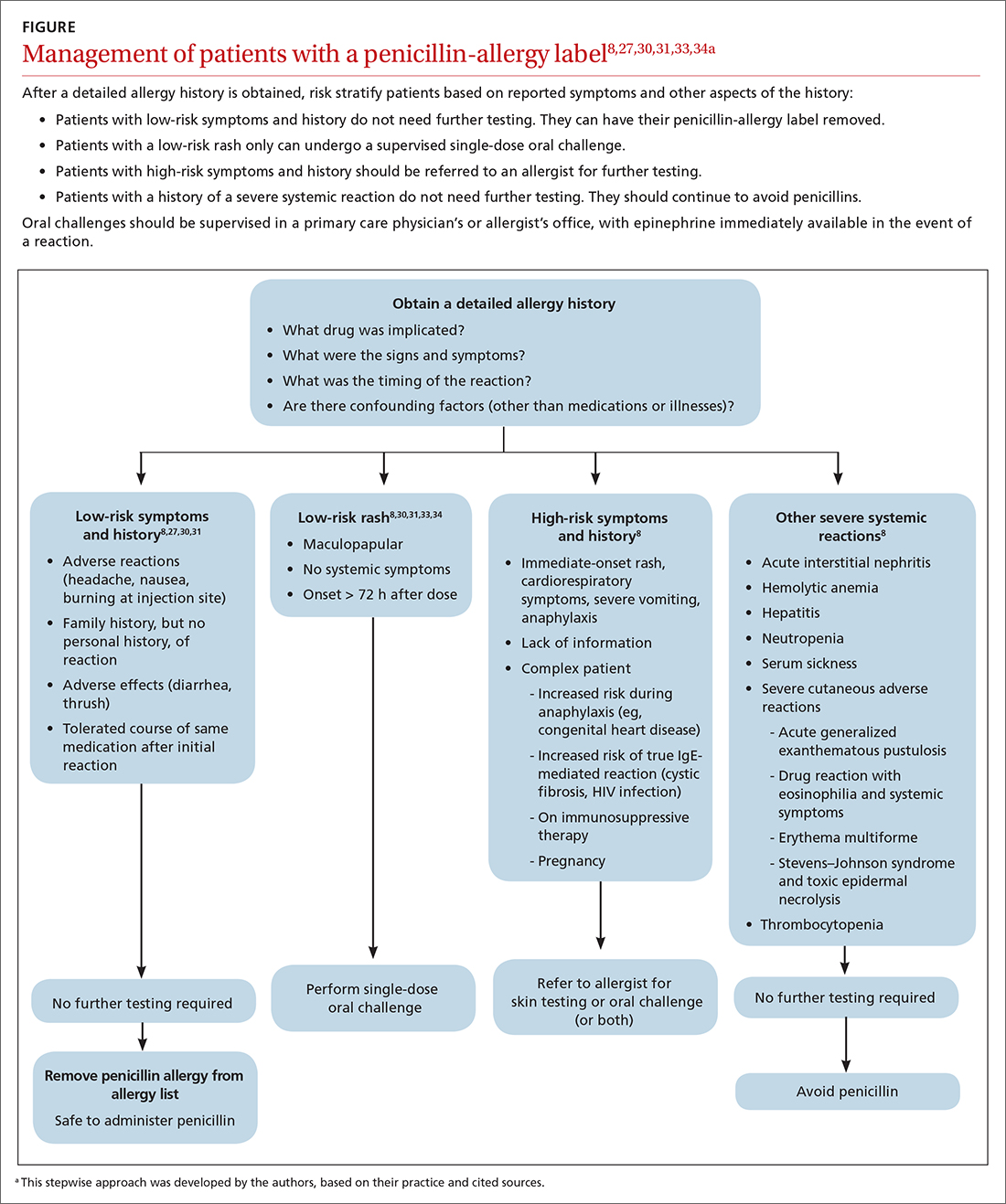

Although drug testing is most often performed in an allergist’s office, several groups have developed protocols that allow for limited testing of low-risk patients in a primary care setting.8,31 For example, several studies have demonstrated that patients presenting with low-risk skin rash can be safely tested with a supervised oral challenge alone.18,28 The FIGURE8,27,30,31,33,34 outlines our proposed workflow for risk stratification and subsequent management of patients with a “penicillin allergy” label.

Continue to: De-labeling requires a systems approach

De-labeling requires a systems approach. Given the mismatch between the large number of patients labeled “penicillin allergic” and the few allergy specialists, referral alone is not enough to solve the problem of mislabeling. Targeting specific populations for testing, such as patients presenting to an inner-city sexually transmitted infection clinic19 or preoperative patients, as is done at the Mayo Clinic,9 has been successful. Skin testing in an inpatient setting has also been shown to be safe and effective,13 allowing for protocol-driven testing under the supervision of trained pharmacists (and others), to relieve the burden on allergy specialists.9

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrew Lutzkanin, MD, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Macy E. The clinical evaluation of penicillin allergy: what is necessary, sufficient and safe given the materials currently available? Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1498-1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03837.x

2. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, et al. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321:188-199. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19283

3. Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Banerji A, et al. The cost of penicillin allergy evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1019-1027.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.006

4. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: Ten things physicians and patients should question. American Board of Medicine Foundation Choosing Wisely website. 2018. Accessed July 7, 2021. www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-academy-of-allergy-asthma-immunology

5. Tan SY, Tatsumura Y. Alexander Fleming (1881-1955): discoverer of penicillin. Singapore Med J. 2015;56:366-367. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015105

6. Marston HD, Dixon DM, Knisely JM, et al. Antimicrobial resistance. JAMA. 2016;316:1193-1204. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11764

7. Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD000023. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub4

8. Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2338-2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1807761

9. Khan DA. Proactive management of penicillin and other antibiotic allergies. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2020;41:82-89. doi: 10.2500/aap.2020.41.190024

10. Idsoe O, Guthe T, Willcox RR, et al. Nature and extent of penicillin side-reactions, with particular reference to fatalities from anaphylactic shock. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;38:159-188.

11. Chiriac AM, Macy E. Large health system databases and drug hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2125-2131. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.014

12. Albin S, Agarwal S. Prevalence and characteristics of reported penicillin allergy in an urban outpatient adult population. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:489-494. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3791

13. Sacco KA, Bates A, Brigham TJ, et al. Clinical outcomes following inpatient penicillin allergy testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2017;72:1288-1296. doi: 10.1111/all.13168

14. Khan DA, Solensky R. Drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 suppl 2):S126-S137. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.028

15. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, et al. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:294-300.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011

16. Macy E, Schatz M, Lin C, et al. The falling rate of positive penicillin skin tests from 1995 to 2007. Perm J. 2009;13:12-18. doi: 10.7812/tpp/08-073

17. Macy E, Ngor EW. Safely diagnosing clinically significant penicillin allergy using only penicilloyl-poly-lysine, penicillin, and oral amoxicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:258-263. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.02.002

18. Bourke J, Pavlos R, James I, et al. Improving the effectiveness of penicillin allergy de-labeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3:365-374.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.11.002

19. Gadde J, Spence M, Wheeler B, et al. Clinical experience with penicillin skin testing in a large inner-city STD clinic. JAMA. 1993;270:2456-2463.

20. Klaustermeyer WB, Gowda VC. Penicillin skin testing: a 20-year study at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Mil Med. 2005;170:701-704. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.8.701.

21. McDanel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:361-367. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ308

22. Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, et al. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:329-336. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix794

23. Mattingly TJ 2nd, Fulton A, Lumish RA, et al. The cost of self-reported penicillin allergy: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1649-1654.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033

24. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:790-796. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

25. Desai SH, Kaplan MS, Chen Q, et al. Morbidity in pregnant women associated with unverified penicillin allergies, antibiotic use, and group B streptococcus infections. Perm J. 2017;21:16-80. doi: 10.7812/TPP/16-080

26. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e56-e93. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir073

27. Vyles D, Mistry RD, Heffner V, et al. Reported knowledge and management of potential penicillin allergy in children. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19:684-690. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.01.002

28. Caubet J-C, Kaiser L, Lemaître B, et al. The role of penicillin in benign skin rashes in childhood: a prospective study based on drug rechallenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:218-222. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.025

29. Wanat M, Anthierens S, Butler CC, et al. Patient and primary care physician perceptions of penicillin allergy testing and subsequent use of penicillin-containing antibiotics: a qualitative study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1888-1893.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.036

30. Norton AE, Konvinse K, Phillips EJ, et al. Antibiotic allergy in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2018;141: e20172497. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2497

31. Collins C. The low risks and high rewards of penicillin allergy delabeling: an algorithm to expedite the evaluation. J Pediatr. 2019;212:216-223. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.05.060

32. Ibia EO, Schwartz RH, Wiedermann BL. Antibiotic rashes in children: a survey in a private practice setting. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:849-854. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.7.849

33. Salkind AR, Cuddy PG, Foxworth JW. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient allergic to penicillin? An evidence-based analysis of the likelihood of penicillin allergy. JAMA. 2001;285:2498-2505. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2498

34. Patel BM. Skin rash with infectious mononucleosis and ampicillin. Pediatrics. 1967;40:910-911.

35. Inglis JM, Caughey GE, Smith W, et al. Documentation of penicillin adverse drug reactions in electronic health records: inconsistent use of allergy and intolerance labels. Intern Med J. 2017;47:1292-1297. doi: 10.1111/imj.13558

36. Lachover-Roth I, Sharon S, Rosman Y, et al. Long-term follow-up after penicillin allergy delabeling in ambulatory patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:231-235.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.04.042

37. Solensky R, Jacobs J, Lester M, et al. Penicillin allergy evaluation: a prospective, multicenter, open-label evaluation of a comprehensive penicillin skin test kit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1876-1885.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.040

38. A; ; . Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259-273. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.08.002

In North America and Europe, penicillin allergy is the most common drug-allergy label.1 Carrying a penicillin-allergy label, which has recently gained more attention in health care systems, leads to suboptimal outcomes, increased use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, increased risk of adverse reactions, and increased cost of care.2,3 Despite the high rate of reported reactions, clinically significant immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated and T cell–mediated hypersensitivity reactions to penicillins are uncommon.2

Through the Choosing Wisely initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology has issued a recommendation: “Don’t overuse non-beta lactam antibiotics in patients with a history of penicillin allergy without an appropriate evaluation.”4 The primary care physician (PCP) plays a critical role in the appropriate evaluation and accurate initial labeling of penicillin allergy. Furthermore, the PCP plays an integral part, in conjunction with the allergist, in removing the “penicillin allergy” label from a patient’s chart when feasible.

The history of penicillin and prevalence of allergy

History. Penicillin, the first antibiotic, was discovered in 1928 by physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming when he observed that a mold of the Penicillium genus inhibited growth of gram-positive pathogens.5 Along with pharmacologist Howard Florey and chemist Ernst Chain, both of whom assisted in the large-scale isolation and production of the antibiotic, Fleming won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 for this discovery.5

Antibiotics transformed the practice of medicine across a spectrum, including safer childbirth, surgical procedures, and transplantation.6 Penicillin remains first-line therapy for many infections, such as streptococcal pharyngitis,7 and is the only recommended medication for treating syphilis during pregnancy.8 Continued effectiveness of penicillin in these cases allows broad-spectrum antibiotics to be reserved for more severe infections. Regrettably, incorrect antibiotic allergy labeling poses a significant risk to the patient and health care system.

Epidemiology. As with all medications, the potential for anaphylaxis exists after administration of penicillin. Because its use is widespread, penicillin is the most common cause of drug-induced anaphylaxis. However, the incidence of penicillin-induced anaphylaxis is low9: A 1968 World Health Organization report stated that the rate of penicillin anaphylaxis was between 0.015% and 0.04%.10 A more recent study reported an incidence of 1 in 207,191 patients after an oral dose and 1 in 95,298 after a parenteral dose.11 The most common reactions to penicillins are urticaria and delayed maculopapular rash.8

In the United States, the prevalence of reported penicillin allergy is approximately 10% (estimated range, 8% to 12%)3,12-15; among hospitalized patients, that prevalence is estimated to be as high as 15%.13,15 However, the prevalence of confirmed penicillin allergy is low and has decreased over time—demonstrated in a longitudinal study in which the rate of a positive skin test fell from 15% in 1995 to 0.8% in 2013.16,17

Studies have confirmed that as many as 90% of patients who report penicillin allergy are, in fact, able to tolerate penicillins.14,18-20 This finding might be a consequence of initial mislabeling of penicillin allergy; often, adverse reactions are documented as “allergy” when no risk of anaphylaxis exists. Furthermore, patients can outgrow IgE-mediated penicillin allergy because the presence of penicillin IgE antibodies wanes over time.14,15

Continue to: Consequences of mislabeling

Consequences of mislabeling

Clinical consequences. A multitude of clinical consequences result from carrying a “penicillin allergy” label.

Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics leads to increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection and to development of resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus.2,15

Alternative antibiotics used in the setting of a “penicillin allergy” label might be less efficacious and result in suboptimal outcomes. For example, vancomycin is less effective against methicillin-sensitive S aureus bacteremia than nafcillin or cefazolin.2,21 Beta-lactam antibiotics—in particular, cefazolin—are often first-line for perioperative prophylaxis; patients with reported penicillin allergy often receive a less-optimal alternative, such as clindamycin, vancomycin, or gentamicin.22 These patients are at increased risk of surgical site infection.2,22

In addition, using penicillin alternatives can result in greater risk of drug reactions and adverse effects.2

Increased health care costs. Primarily through observational studies, penicillin allergy has been associated with higher health care costs.23 Patients with reported penicillin allergy had, on average, a longer inpatient stay than patients without penicillin allergy, at a 3-year total estimated additional cost of $64.6 million.24 Inpatients with a listed penicillin allergy had direct drug costs ranging from “no difference” to $609 per patient more than patients without a listed penicillin allergy. Outpatient prescription costs were $14 to $193 higher per patient for patients with a listed penicillin allergy.23

Continue to: Considerations in special populations

Considerations in special populations. Evaluating penicillin allergy during routine care is key to decreasing the necessity for urgent penicillin evaluation and possible desensitization at the time of serious infection. Certain patient populations pose specific challenges:

- Pregnant patients. Unverified penicillin allergy during pregnancy is associated with an increased rate of cesarean section and longer postpartum hospitalization.25 Additionally, group B streptococcus-positive women have increased exposure to alternative antibiotics and an increased incidence of adverse drug reactions.25

- Elderly patients. Drug allergy increases with aging.1 Elderly patients in a long-term care facility are more likely to experience adverse drug effects or drug–drug interactions from the use of penicillin alternatives, such as clindamycin, vancomycin, and fluoroquinolones.2

- Oncology patients often require antibiotic prophylaxis as well as treatment for illnesses, such as neutropenic fever, for which beta-lactam antibiotics are often used as initial treatment.2,26

- Other important populations that present specific challenges include hospitalized patients, pediatric patients, and patients with a sexually transmitted infection.2

Active management of a penicillin-allergy label

Greater recognition of the consequences of penicillin allergy in recent years has led to efforts by hospitals and other health care organizations to develop processes by which patients can be successfully de-labeled as part of antibiotic stewardship programs9 and other initiatives. Ideally, every patient who has a “penicillin allergy” label would be referred to an allergist for evaluation; however, the number of allergy specialists is limited, and access to such specialists might be restricted in some areas, making this approach impracticable. Active management of penicillin allergy requires strategies to both test and de-label patients, as well as proactive approaches to prevent incorrect labeling. These proactive approaches require involvement of all members of the health care team—especially PCPs.

Preventing incorrect labeling. PCPs are the most likely to initially label a patient as allergic to penicillin.27 Most physicians rely on a reported history of allergy alone when selecting medication12; once a patient has been labeled “penicillin allergic,” they often retain that mislabel through adulthood.27,28 A qualitative study of PCPs’ views on prescribing penicillin found that many were aware that documented allergies were incorrect but were uncomfortable using their clinical judgment to prescribe a penicillin or change the record, for fear of a future anaphylactic reaction.29 The first step in the case of any reported reaction should be for you to elicit an accurate drug allergy history (TABLE 1).

As with other drug reactions, you should consider the context surrounding the reaction to a penicillin. Take care to review signs and symptoms of the reaction to look for clues that make a true allergic reaction more, or less, likely.

Symptoms can generally be divided into low-risk and high-risk categories27 (TABLE 2). An example of a commonly reported low-risk symptom is diarrhea that develops after several doses of a penicillin. In the absence of other symptoms, this finding is most likely due to elimination of normal gut flora,30 not to an allergic reaction to the medication. Symptoms of intolerance to the medication, such as headache and nausea, are also low risk.27,31 In contrast, immediate onset of abdominal pain after a dose of penicillin and lip or throat swelling are considered high risk.

Continue to: Patients presenting with urticaria...

Patients presenting with urticaria or maculopapular rash after taking penicillin are particularly challenging.30 A study of patients in a primary care pediatrics practice found that 7.4% of children receiving a prescription for a penicillin reported a rash.32 Here, timing of onset of symptoms provides some clarity about the likelihood of true allergy. Rashes that manifest during the first hours after exposure are more likely to be IgE mediated, particularly when accompanied by other systemic symptoms; they should be considered high risk. Delayed-onset rashes (> 72 hours after exposure) are usually non-IgE mediated and therefore are generally lower risk,8,30,33 except when associated with certain features, such as mucosal involvement and skin peeling.

Despite acknowledging viral exanthems in the differential, many physicians still label patients presenting with any rash as “allergic.”28 Take care to look for other potential causes of a rash; for example, patients taking amoxicillin who have concurrent Epstein-Barr virus infection frequently develop a maculopapular rash.34 Caubet and colleagues found that 56% of pediatric patients with a history of nonimmediate rash and a negative oral challenge to amoxicillin tested positive for viral infection.28

A family history of penicillin allergy alone should not preclude the use of penicillin.8,27,31 Similarly, if a patient has already received and tolerated a subsequent course of the same penicillin derivative after the initial reaction, the “penicillin allergy” label can be removed. If the reaction history is unknown, refer the patient to an allergist for further evaluation.

Accurate charting is key. With most hospital systems and physician practices now documenting in an electronic health record, there exists the ability to document, in great detail, patients’ reactions to medications. Previous studies have found, however, that such documentation is often done poorly, or not done at all. One such study found that (1) > 20% of patients with a “penicillin allergy” label did not have reaction details listed and (2) when reactions were listed, many were incorrectly labeled as “allergy,” not “intolerance.”35

Many electronic health record systems lump drug allergies, adverse effects, and food and environmental allergies into a single section, leading to a lack of distinction between adverse reactions and true allergy.31 Although many PCPs report that it is easy to change a patient’s allergy label in the record,29 more often, a nurse, resident, or consultant actually documents the reaction.35

Continue to: Documentation at the time of the reaction...

Documentation at the time of the reaction, within the encounter note and the allergy tab, is essential, so that other physicians caring for the patient, in the future, will be knowledgeable about the details of the reaction. Make it your responsibility to accurately document penicillin allergy in patients’ charts, including removing the “penicillin allergy” label from the chart of patients whose history is inconsistent with allergy, who have tolerated subsequent courses of the same penicillin derivative, or who have passed testing in an allergist’s office. In a study of 639 patients who tested negative for penicillin allergy, 51% still had a “penicillin allergy” label in their chart more than 4 years later.36

Penicillin allergy evaluation. When a patient cannot be cleared of a “penicillin allergy” label by history alone, and in the absence of severe features such as mucous membrane involvement, they should be further evaluated through objective testing for potential IgE-mediated allergy. This assessment includes penicillin skin testing or an oral challenge, or both.

Skin testing involves skin-prick testing of major and minor determinants of penicillin; when skin-prick testing is negative, intradermal testing of major and minor determinants should follow. The negative predictive value of penicillin skin testing is high: In a prospective, multicenter investigation, researchers demonstrated that, when both the major penicillin determinant and a minor determinant mixture were used, negative predictive value was 97.9%.37

However, a minor determinant mixture is not commercially available in the United States; therefore, penicillin G is often used alone as the minor determinant. Typically, if a patient passes skin testing, a challenge dose of penicillin or amoxicillin is administered, followed by an observation period. The risk of re-sensitization after oral penicillin is thought to be low and does not preclude future use.38

Although drug testing is most often performed in an allergist’s office, several groups have developed protocols that allow for limited testing of low-risk patients in a primary care setting.8,31 For example, several studies have demonstrated that patients presenting with low-risk skin rash can be safely tested with a supervised oral challenge alone.18,28 The FIGURE8,27,30,31,33,34 outlines our proposed workflow for risk stratification and subsequent management of patients with a “penicillin allergy” label.

Continue to: De-labeling requires a systems approach

De-labeling requires a systems approach. Given the mismatch between the large number of patients labeled “penicillin allergic” and the few allergy specialists, referral alone is not enough to solve the problem of mislabeling. Targeting specific populations for testing, such as patients presenting to an inner-city sexually transmitted infection clinic19 or preoperative patients, as is done at the Mayo Clinic,9 has been successful. Skin testing in an inpatient setting has also been shown to be safe and effective,13 allowing for protocol-driven testing under the supervision of trained pharmacists (and others), to relieve the burden on allergy specialists.9

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrew Lutzkanin, MD, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

In North America and Europe, penicillin allergy is the most common drug-allergy label.1 Carrying a penicillin-allergy label, which has recently gained more attention in health care systems, leads to suboptimal outcomes, increased use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, increased risk of adverse reactions, and increased cost of care.2,3 Despite the high rate of reported reactions, clinically significant immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated and T cell–mediated hypersensitivity reactions to penicillins are uncommon.2

Through the Choosing Wisely initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology has issued a recommendation: “Don’t overuse non-beta lactam antibiotics in patients with a history of penicillin allergy without an appropriate evaluation.”4 The primary care physician (PCP) plays a critical role in the appropriate evaluation and accurate initial labeling of penicillin allergy. Furthermore, the PCP plays an integral part, in conjunction with the allergist, in removing the “penicillin allergy” label from a patient’s chart when feasible.

The history of penicillin and prevalence of allergy

History. Penicillin, the first antibiotic, was discovered in 1928 by physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming when he observed that a mold of the Penicillium genus inhibited growth of gram-positive pathogens.5 Along with pharmacologist Howard Florey and chemist Ernst Chain, both of whom assisted in the large-scale isolation and production of the antibiotic, Fleming won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 for this discovery.5

Antibiotics transformed the practice of medicine across a spectrum, including safer childbirth, surgical procedures, and transplantation.6 Penicillin remains first-line therapy for many infections, such as streptococcal pharyngitis,7 and is the only recommended medication for treating syphilis during pregnancy.8 Continued effectiveness of penicillin in these cases allows broad-spectrum antibiotics to be reserved for more severe infections. Regrettably, incorrect antibiotic allergy labeling poses a significant risk to the patient and health care system.

Epidemiology. As with all medications, the potential for anaphylaxis exists after administration of penicillin. Because its use is widespread, penicillin is the most common cause of drug-induced anaphylaxis. However, the incidence of penicillin-induced anaphylaxis is low9: A 1968 World Health Organization report stated that the rate of penicillin anaphylaxis was between 0.015% and 0.04%.10 A more recent study reported an incidence of 1 in 207,191 patients after an oral dose and 1 in 95,298 after a parenteral dose.11 The most common reactions to penicillins are urticaria and delayed maculopapular rash.8

In the United States, the prevalence of reported penicillin allergy is approximately 10% (estimated range, 8% to 12%)3,12-15; among hospitalized patients, that prevalence is estimated to be as high as 15%.13,15 However, the prevalence of confirmed penicillin allergy is low and has decreased over time—demonstrated in a longitudinal study in which the rate of a positive skin test fell from 15% in 1995 to 0.8% in 2013.16,17

Studies have confirmed that as many as 90% of patients who report penicillin allergy are, in fact, able to tolerate penicillins.14,18-20 This finding might be a consequence of initial mislabeling of penicillin allergy; often, adverse reactions are documented as “allergy” when no risk of anaphylaxis exists. Furthermore, patients can outgrow IgE-mediated penicillin allergy because the presence of penicillin IgE antibodies wanes over time.14,15

Continue to: Consequences of mislabeling

Consequences of mislabeling

Clinical consequences. A multitude of clinical consequences result from carrying a “penicillin allergy” label.

Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics leads to increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection and to development of resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus.2,15

Alternative antibiotics used in the setting of a “penicillin allergy” label might be less efficacious and result in suboptimal outcomes. For example, vancomycin is less effective against methicillin-sensitive S aureus bacteremia than nafcillin or cefazolin.2,21 Beta-lactam antibiotics—in particular, cefazolin—are often first-line for perioperative prophylaxis; patients with reported penicillin allergy often receive a less-optimal alternative, such as clindamycin, vancomycin, or gentamicin.22 These patients are at increased risk of surgical site infection.2,22

In addition, using penicillin alternatives can result in greater risk of drug reactions and adverse effects.2

Increased health care costs. Primarily through observational studies, penicillin allergy has been associated with higher health care costs.23 Patients with reported penicillin allergy had, on average, a longer inpatient stay than patients without penicillin allergy, at a 3-year total estimated additional cost of $64.6 million.24 Inpatients with a listed penicillin allergy had direct drug costs ranging from “no difference” to $609 per patient more than patients without a listed penicillin allergy. Outpatient prescription costs were $14 to $193 higher per patient for patients with a listed penicillin allergy.23

Continue to: Considerations in special populations

Considerations in special populations. Evaluating penicillin allergy during routine care is key to decreasing the necessity for urgent penicillin evaluation and possible desensitization at the time of serious infection. Certain patient populations pose specific challenges:

- Pregnant patients. Unverified penicillin allergy during pregnancy is associated with an increased rate of cesarean section and longer postpartum hospitalization.25 Additionally, group B streptococcus-positive women have increased exposure to alternative antibiotics and an increased incidence of adverse drug reactions.25

- Elderly patients. Drug allergy increases with aging.1 Elderly patients in a long-term care facility are more likely to experience adverse drug effects or drug–drug interactions from the use of penicillin alternatives, such as clindamycin, vancomycin, and fluoroquinolones.2

- Oncology patients often require antibiotic prophylaxis as well as treatment for illnesses, such as neutropenic fever, for which beta-lactam antibiotics are often used as initial treatment.2,26

- Other important populations that present specific challenges include hospitalized patients, pediatric patients, and patients with a sexually transmitted infection.2

Active management of a penicillin-allergy label

Greater recognition of the consequences of penicillin allergy in recent years has led to efforts by hospitals and other health care organizations to develop processes by which patients can be successfully de-labeled as part of antibiotic stewardship programs9 and other initiatives. Ideally, every patient who has a “penicillin allergy” label would be referred to an allergist for evaluation; however, the number of allergy specialists is limited, and access to such specialists might be restricted in some areas, making this approach impracticable. Active management of penicillin allergy requires strategies to both test and de-label patients, as well as proactive approaches to prevent incorrect labeling. These proactive approaches require involvement of all members of the health care team—especially PCPs.