User login

Ear tubes no better than antibiotics for otitis media in young kids

The debate over tympanostomy tubes versus antibiotics for recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) in young children is long-standing. Now, results of a randomized controlled trial show that tubes do not significantly lower the rate of episodes, compared with antibiotics, and medical management doesn’t increase antibiotic resistance.

“We found no evidence of microbial resistance from treating with antibiotics. If there’s not an impact on resistance, why take unnecessary chances on complications of surgery?” lead author Alejandro Hoberman, MD, from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The study by Dr. Hoberman and colleagues was published May 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

AOM is the most frequent condition diagnosed in children in the United States after the common cold, affecting five of six children younger than 3 years. It is the leading indication for antimicrobial treatment, and tympanostomy tube insertion is the most frequently performed pediatric operation after the newborn period.

Randomized controlled clinical trials were conducted in the 1980s, but by the 1990s, questions of overuse arose. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation published the first clinical practice guidelines in 2013.

Parents must weigh the pros and cons. The use of tubes may avoid or delay the next round of drugs, but tubes cost more and introduce small risks (anesthesia, refractory otorrhea, tube blockage, premature dislocation or extrusion, and mild conductive hearing loss).

“We addressed issues that plagued older studies – a longer-term follow-up of 2 years, validated diagnoses of infection to determine eligibility – and used rating scales to measure quality of life,” Dr. Hoberman said.

The researchers randomly assigned children to receive antibiotics or tubes. To be eligible, children had to be 6-35 months of age and have had at least three episodes of AOM within 6 months or at least four episodes within 12 months, including at least one within the preceding 6 months.

The primary outcome was the mean number of episodes of AOM per child-year. Children were assessed at 8-week intervals and within 48 hours of developing symptoms of ear infection. The medically treated children received oral amoxicillin or, if that was ineffective, intramuscular ceftriaxone.

Criteria for determining treatment failure included persistent otorrhea, tympanic membrane perforation, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, reaction to anesthesia, and recurrence of AOM at a frequency equal to the frequency before antibiotic treatment.

In comparing tympanostomy tubes with antibiotics, Dr. Hoberman said, “We were unable to show benefit in the rate of ear infections per child per year over a 2-year period.” As expected, the infection rate fell by about half from the first year to the second in all children.

Overall, the investigators found “no substantial differences between treatment groups” with regard to AOM frequency, percentage of severe episodes, extent of antimicrobial resistance, quality of life for the children, and parental stress.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, the rate of AOM episodes per child-year during the study was 1.48 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.56 ± 0.08 for antibiotics (P = .66).

However, randomization was not maintained in the intention-to-treat arm. Ten percent (13 of 129) of the children slated to receive tubes didn’t get them because of parental request. Conversely, 16% (54 of 121) of children in the antibiotic group received tubes, 35 (29%) of them in accordance with the trial protocol because of frequent recurrences, and 19 (16%) at parental request.

In a per-protocol analysis, rates of AOM episodes per child-year were 1.47 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.72 ± 0.11 for antibiotics.

Tubes were associated with longer time until the first ear infection post placement, at a median of 4.34 months, compared with 2.33 months for children who received antibiotics. A smaller percentage of children in the tube group had treatment failure than in the antibiotic group (45% vs. 62%). Children who received tubes also had fewer days per year with symptoms in comparison with the children in the antibiotic group (mean, 2.00 ± 0.29 days vs. 8.33 ± 0.59 days).

The frequency distribution of AOM episodes, the percentage of severe episodes, and antimicrobial resistance detected in respiratory specimens were the same for both groups.

“Hoberman and colleagues add to our knowledge of managing children with recurrent ear infections with a large and rigorous clinical trial showing comparable efficacy of tympanostomy tube insertion, with antibiotic eardrops for new infections versus watchful waiting, with intermittent oral antibiotics, if further ear infections occur,” said Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, MBA, distinguished professor and chairman, department of otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, New York.

However, in an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, pointed out that the sample size was smaller than desired, owing to participants switching groups.

In addition, Dr. Rosenfeld, who was the lead author of the 2013 guidelines, said the study likely underestimates the impact of tubes “because about two-thirds of the children who received them did not have persistent middle-ear fluid at baseline and would not have been candidates for tubes based on the current national guideline on tube indications.”

“Both tubes and intermittent antibiotic therapy are effective for managing recurrent AOM, and parents of children with persistent middle-ear effusion should engage in shared decision-making with their physician to decide on the best management option,” said Dr. Rosenfeld. “When in doubt, watchful waiting is appropriate because many children with recurrent AOM do better over time.”

Dr. Hoberman owns stock in Kaizen Bioscience and holds patents on devices to diagnose and treat AOM. One coauthor consults for Merck. Dr. Wald and Dr. Rosenfeld report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The debate over tympanostomy tubes versus antibiotics for recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) in young children is long-standing. Now, results of a randomized controlled trial show that tubes do not significantly lower the rate of episodes, compared with antibiotics, and medical management doesn’t increase antibiotic resistance.

“We found no evidence of microbial resistance from treating with antibiotics. If there’s not an impact on resistance, why take unnecessary chances on complications of surgery?” lead author Alejandro Hoberman, MD, from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The study by Dr. Hoberman and colleagues was published May 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

AOM is the most frequent condition diagnosed in children in the United States after the common cold, affecting five of six children younger than 3 years. It is the leading indication for antimicrobial treatment, and tympanostomy tube insertion is the most frequently performed pediatric operation after the newborn period.

Randomized controlled clinical trials were conducted in the 1980s, but by the 1990s, questions of overuse arose. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation published the first clinical practice guidelines in 2013.

Parents must weigh the pros and cons. The use of tubes may avoid or delay the next round of drugs, but tubes cost more and introduce small risks (anesthesia, refractory otorrhea, tube blockage, premature dislocation or extrusion, and mild conductive hearing loss).

“We addressed issues that plagued older studies – a longer-term follow-up of 2 years, validated diagnoses of infection to determine eligibility – and used rating scales to measure quality of life,” Dr. Hoberman said.

The researchers randomly assigned children to receive antibiotics or tubes. To be eligible, children had to be 6-35 months of age and have had at least three episodes of AOM within 6 months or at least four episodes within 12 months, including at least one within the preceding 6 months.

The primary outcome was the mean number of episodes of AOM per child-year. Children were assessed at 8-week intervals and within 48 hours of developing symptoms of ear infection. The medically treated children received oral amoxicillin or, if that was ineffective, intramuscular ceftriaxone.

Criteria for determining treatment failure included persistent otorrhea, tympanic membrane perforation, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, reaction to anesthesia, and recurrence of AOM at a frequency equal to the frequency before antibiotic treatment.

In comparing tympanostomy tubes with antibiotics, Dr. Hoberman said, “We were unable to show benefit in the rate of ear infections per child per year over a 2-year period.” As expected, the infection rate fell by about half from the first year to the second in all children.

Overall, the investigators found “no substantial differences between treatment groups” with regard to AOM frequency, percentage of severe episodes, extent of antimicrobial resistance, quality of life for the children, and parental stress.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, the rate of AOM episodes per child-year during the study was 1.48 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.56 ± 0.08 for antibiotics (P = .66).

However, randomization was not maintained in the intention-to-treat arm. Ten percent (13 of 129) of the children slated to receive tubes didn’t get them because of parental request. Conversely, 16% (54 of 121) of children in the antibiotic group received tubes, 35 (29%) of them in accordance with the trial protocol because of frequent recurrences, and 19 (16%) at parental request.

In a per-protocol analysis, rates of AOM episodes per child-year were 1.47 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.72 ± 0.11 for antibiotics.

Tubes were associated with longer time until the first ear infection post placement, at a median of 4.34 months, compared with 2.33 months for children who received antibiotics. A smaller percentage of children in the tube group had treatment failure than in the antibiotic group (45% vs. 62%). Children who received tubes also had fewer days per year with symptoms in comparison with the children in the antibiotic group (mean, 2.00 ± 0.29 days vs. 8.33 ± 0.59 days).

The frequency distribution of AOM episodes, the percentage of severe episodes, and antimicrobial resistance detected in respiratory specimens were the same for both groups.

“Hoberman and colleagues add to our knowledge of managing children with recurrent ear infections with a large and rigorous clinical trial showing comparable efficacy of tympanostomy tube insertion, with antibiotic eardrops for new infections versus watchful waiting, with intermittent oral antibiotics, if further ear infections occur,” said Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, MBA, distinguished professor and chairman, department of otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, New York.

However, in an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, pointed out that the sample size was smaller than desired, owing to participants switching groups.

In addition, Dr. Rosenfeld, who was the lead author of the 2013 guidelines, said the study likely underestimates the impact of tubes “because about two-thirds of the children who received them did not have persistent middle-ear fluid at baseline and would not have been candidates for tubes based on the current national guideline on tube indications.”

“Both tubes and intermittent antibiotic therapy are effective for managing recurrent AOM, and parents of children with persistent middle-ear effusion should engage in shared decision-making with their physician to decide on the best management option,” said Dr. Rosenfeld. “When in doubt, watchful waiting is appropriate because many children with recurrent AOM do better over time.”

Dr. Hoberman owns stock in Kaizen Bioscience and holds patents on devices to diagnose and treat AOM. One coauthor consults for Merck. Dr. Wald and Dr. Rosenfeld report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The debate over tympanostomy tubes versus antibiotics for recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) in young children is long-standing. Now, results of a randomized controlled trial show that tubes do not significantly lower the rate of episodes, compared with antibiotics, and medical management doesn’t increase antibiotic resistance.

“We found no evidence of microbial resistance from treating with antibiotics. If there’s not an impact on resistance, why take unnecessary chances on complications of surgery?” lead author Alejandro Hoberman, MD, from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The study by Dr. Hoberman and colleagues was published May 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

AOM is the most frequent condition diagnosed in children in the United States after the common cold, affecting five of six children younger than 3 years. It is the leading indication for antimicrobial treatment, and tympanostomy tube insertion is the most frequently performed pediatric operation after the newborn period.

Randomized controlled clinical trials were conducted in the 1980s, but by the 1990s, questions of overuse arose. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation published the first clinical practice guidelines in 2013.

Parents must weigh the pros and cons. The use of tubes may avoid or delay the next round of drugs, but tubes cost more and introduce small risks (anesthesia, refractory otorrhea, tube blockage, premature dislocation or extrusion, and mild conductive hearing loss).

“We addressed issues that plagued older studies – a longer-term follow-up of 2 years, validated diagnoses of infection to determine eligibility – and used rating scales to measure quality of life,” Dr. Hoberman said.

The researchers randomly assigned children to receive antibiotics or tubes. To be eligible, children had to be 6-35 months of age and have had at least three episodes of AOM within 6 months or at least four episodes within 12 months, including at least one within the preceding 6 months.

The primary outcome was the mean number of episodes of AOM per child-year. Children were assessed at 8-week intervals and within 48 hours of developing symptoms of ear infection. The medically treated children received oral amoxicillin or, if that was ineffective, intramuscular ceftriaxone.

Criteria for determining treatment failure included persistent otorrhea, tympanic membrane perforation, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, reaction to anesthesia, and recurrence of AOM at a frequency equal to the frequency before antibiotic treatment.

In comparing tympanostomy tubes with antibiotics, Dr. Hoberman said, “We were unable to show benefit in the rate of ear infections per child per year over a 2-year period.” As expected, the infection rate fell by about half from the first year to the second in all children.

Overall, the investigators found “no substantial differences between treatment groups” with regard to AOM frequency, percentage of severe episodes, extent of antimicrobial resistance, quality of life for the children, and parental stress.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, the rate of AOM episodes per child-year during the study was 1.48 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.56 ± 0.08 for antibiotics (P = .66).

However, randomization was not maintained in the intention-to-treat arm. Ten percent (13 of 129) of the children slated to receive tubes didn’t get them because of parental request. Conversely, 16% (54 of 121) of children in the antibiotic group received tubes, 35 (29%) of them in accordance with the trial protocol because of frequent recurrences, and 19 (16%) at parental request.

In a per-protocol analysis, rates of AOM episodes per child-year were 1.47 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.72 ± 0.11 for antibiotics.

Tubes were associated with longer time until the first ear infection post placement, at a median of 4.34 months, compared with 2.33 months for children who received antibiotics. A smaller percentage of children in the tube group had treatment failure than in the antibiotic group (45% vs. 62%). Children who received tubes also had fewer days per year with symptoms in comparison with the children in the antibiotic group (mean, 2.00 ± 0.29 days vs. 8.33 ± 0.59 days).

The frequency distribution of AOM episodes, the percentage of severe episodes, and antimicrobial resistance detected in respiratory specimens were the same for both groups.

“Hoberman and colleagues add to our knowledge of managing children with recurrent ear infections with a large and rigorous clinical trial showing comparable efficacy of tympanostomy tube insertion, with antibiotic eardrops for new infections versus watchful waiting, with intermittent oral antibiotics, if further ear infections occur,” said Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, MBA, distinguished professor and chairman, department of otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, New York.

However, in an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, pointed out that the sample size was smaller than desired, owing to participants switching groups.

In addition, Dr. Rosenfeld, who was the lead author of the 2013 guidelines, said the study likely underestimates the impact of tubes “because about two-thirds of the children who received them did not have persistent middle-ear fluid at baseline and would not have been candidates for tubes based on the current national guideline on tube indications.”

“Both tubes and intermittent antibiotic therapy are effective for managing recurrent AOM, and parents of children with persistent middle-ear effusion should engage in shared decision-making with their physician to decide on the best management option,” said Dr. Rosenfeld. “When in doubt, watchful waiting is appropriate because many children with recurrent AOM do better over time.”

Dr. Hoberman owns stock in Kaizen Bioscience and holds patents on devices to diagnose and treat AOM. One coauthor consults for Merck. Dr. Wald and Dr. Rosenfeld report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low-risk preterm infants may not need antibiotics

Selective use of antibiotics based on birth circumstances may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure for preterm infants at risk of early-onset sepsis, based on data from 340 preterm infants at a single center.

Preterm infants born because of preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and/or intraamniotic infection (IAI) are considered at increased risk for early-onset sepsis, and current management strategies include a blood culture and initiation of empirical antibiotics, said Kirtan Patel, MD, of Texas A&M University, Dallas, and colleagues in a poster (# 1720) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

However, this blanket approach “may increase the unnecessary early antibiotic exposure in preterm infants possibly leading to future adverse health outcomes,” and physicians are advised to review the risks and benefits, Dr. Patel said.

Data from previous studies suggest that preterm infants born as a result of preterm labor and/or premature rupture of membranes with adequate Group B Streptococcus (GBS) intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis and no indication of IAI may be managed without empiric antibiotics because the early-onset sepsis risk in these infants is much lower than the ones born through IAI and inadequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis.

To better identify preterm birth circumstances in which antibiotics might be avoided, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of preterm infants born at 28-34 weeks’ gestation during the period from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2018. These infants were in the low-risk category of preterm birth because of preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes, with no IAI and adequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and no signs of cardiovascular or respiratory instability after birth. Of these, 157 (46.2%) received empiric antibiotics soon after birth and 183 infants (53.8%) did not receive empiric antibiotics.

The mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the empiric antibiotic group, but after correcting for these variables, the factors with the greatest influence on the initiation of antibiotics were maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 3.13); premature rupture of membranes (OR, 3.75); use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the delivery room (OR, 1.84); CPAP on admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.94); drawing a blood culture (OR, 13.72); and a complete blood count with immature to total neutrophil ratio greater than 0.2 (OR, 3.84).

Three infants (2%) in the antibiotics group had culture-positive early-onset sepsis with Escherichia coli, compared with no infants in the no-antibiotics group. No differences in short-term hospital outcomes appeared between the two groups. The study was limited in part by the retrospective design and sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support a selective approach to antibiotics for preterm infants, taking various birth circumstances into account, they said.

Further risk factor identification could curb antibiotic use

In this study, empiric antibiotics were cast as a wide net to avoid missing serious infections in a few patients, said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“It is interesting in this retrospective review of 340 preterm infants that the three newborns that did have serious bacterial infection were correctly given empiric antibiotics from the start,” Dr. Joos noted. “The authors were very effective at elucidating the possible factors that go into starting or not starting empiric antibiotics, although there may be other factors in the clinician’s judgment that are being missed. … More studies are needed on this topic,” Dr. Joos said. “Further research examining how the septic newborns differ from the nonseptic ones could help to even further narrow the use of empiric antibiotics,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Selective use of antibiotics based on birth circumstances may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure for preterm infants at risk of early-onset sepsis, based on data from 340 preterm infants at a single center.

Preterm infants born because of preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and/or intraamniotic infection (IAI) are considered at increased risk for early-onset sepsis, and current management strategies include a blood culture and initiation of empirical antibiotics, said Kirtan Patel, MD, of Texas A&M University, Dallas, and colleagues in a poster (# 1720) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

However, this blanket approach “may increase the unnecessary early antibiotic exposure in preterm infants possibly leading to future adverse health outcomes,” and physicians are advised to review the risks and benefits, Dr. Patel said.

Data from previous studies suggest that preterm infants born as a result of preterm labor and/or premature rupture of membranes with adequate Group B Streptococcus (GBS) intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis and no indication of IAI may be managed without empiric antibiotics because the early-onset sepsis risk in these infants is much lower than the ones born through IAI and inadequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis.

To better identify preterm birth circumstances in which antibiotics might be avoided, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of preterm infants born at 28-34 weeks’ gestation during the period from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2018. These infants were in the low-risk category of preterm birth because of preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes, with no IAI and adequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and no signs of cardiovascular or respiratory instability after birth. Of these, 157 (46.2%) received empiric antibiotics soon after birth and 183 infants (53.8%) did not receive empiric antibiotics.

The mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the empiric antibiotic group, but after correcting for these variables, the factors with the greatest influence on the initiation of antibiotics were maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 3.13); premature rupture of membranes (OR, 3.75); use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the delivery room (OR, 1.84); CPAP on admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.94); drawing a blood culture (OR, 13.72); and a complete blood count with immature to total neutrophil ratio greater than 0.2 (OR, 3.84).

Three infants (2%) in the antibiotics group had culture-positive early-onset sepsis with Escherichia coli, compared with no infants in the no-antibiotics group. No differences in short-term hospital outcomes appeared between the two groups. The study was limited in part by the retrospective design and sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support a selective approach to antibiotics for preterm infants, taking various birth circumstances into account, they said.

Further risk factor identification could curb antibiotic use

In this study, empiric antibiotics were cast as a wide net to avoid missing serious infections in a few patients, said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“It is interesting in this retrospective review of 340 preterm infants that the three newborns that did have serious bacterial infection were correctly given empiric antibiotics from the start,” Dr. Joos noted. “The authors were very effective at elucidating the possible factors that go into starting or not starting empiric antibiotics, although there may be other factors in the clinician’s judgment that are being missed. … More studies are needed on this topic,” Dr. Joos said. “Further research examining how the septic newborns differ from the nonseptic ones could help to even further narrow the use of empiric antibiotics,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Selective use of antibiotics based on birth circumstances may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure for preterm infants at risk of early-onset sepsis, based on data from 340 preterm infants at a single center.

Preterm infants born because of preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and/or intraamniotic infection (IAI) are considered at increased risk for early-onset sepsis, and current management strategies include a blood culture and initiation of empirical antibiotics, said Kirtan Patel, MD, of Texas A&M University, Dallas, and colleagues in a poster (# 1720) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

However, this blanket approach “may increase the unnecessary early antibiotic exposure in preterm infants possibly leading to future adverse health outcomes,” and physicians are advised to review the risks and benefits, Dr. Patel said.

Data from previous studies suggest that preterm infants born as a result of preterm labor and/or premature rupture of membranes with adequate Group B Streptococcus (GBS) intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis and no indication of IAI may be managed without empiric antibiotics because the early-onset sepsis risk in these infants is much lower than the ones born through IAI and inadequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis.

To better identify preterm birth circumstances in which antibiotics might be avoided, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of preterm infants born at 28-34 weeks’ gestation during the period from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2018. These infants were in the low-risk category of preterm birth because of preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes, with no IAI and adequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and no signs of cardiovascular or respiratory instability after birth. Of these, 157 (46.2%) received empiric antibiotics soon after birth and 183 infants (53.8%) did not receive empiric antibiotics.

The mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the empiric antibiotic group, but after correcting for these variables, the factors with the greatest influence on the initiation of antibiotics were maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 3.13); premature rupture of membranes (OR, 3.75); use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the delivery room (OR, 1.84); CPAP on admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.94); drawing a blood culture (OR, 13.72); and a complete blood count with immature to total neutrophil ratio greater than 0.2 (OR, 3.84).

Three infants (2%) in the antibiotics group had culture-positive early-onset sepsis with Escherichia coli, compared with no infants in the no-antibiotics group. No differences in short-term hospital outcomes appeared between the two groups. The study was limited in part by the retrospective design and sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support a selective approach to antibiotics for preterm infants, taking various birth circumstances into account, they said.

Further risk factor identification could curb antibiotic use

In this study, empiric antibiotics were cast as a wide net to avoid missing serious infections in a few patients, said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“It is interesting in this retrospective review of 340 preterm infants that the three newborns that did have serious bacterial infection were correctly given empiric antibiotics from the start,” Dr. Joos noted. “The authors were very effective at elucidating the possible factors that go into starting or not starting empiric antibiotics, although there may be other factors in the clinician’s judgment that are being missed. … More studies are needed on this topic,” Dr. Joos said. “Further research examining how the septic newborns differ from the nonseptic ones could help to even further narrow the use of empiric antibiotics,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

FROM PAS 2021

Update in Hospital Medicine relays important findings

Two experts scoured the medical journals for the practice-changing research most relevant to hospital medicine in 2020 at a recent session at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The presenters chose findings they considered either practice changing or practice confirming, and in areas over which hospitalists have at least some control. Here is what they highlighted:

IV iron administration before hospital discharge

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial across 121 centers in Europe, South America, and Singapore, 1,108 patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and iron deficiency were randomized to receive intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or placebo, with a first dose before discharge and a second at 6 weeks.

Those in the intravenous iron group had a significant reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure up to 52 weeks after randomization, but there was no significant reduction in deaths because of heart failure. There was no difference in serious adverse events.

Anthony Breu, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said the findings should alter hospitalist practice.

“In patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%, check iron studies and start IV iron prior to discharge if they have iron deficiency, with or without anemia,” he said.

Apixaban versus dalteparin for venous thromboembolism in cancer

This noninferiority trial involved 1,155 adults with cancer who had symptomatic or incidental acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The patients were randomized to receive oral apixaban or subcutaneous dalteparin for 6 months.

Patients in the apixaban group had a significantly lower rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism (P = .09), with no increase in major bleeds, Dr. Breu said. He noted that those with brain cancer and leukemia were excluded.

“In patients with cancer and acute venous thromboembolism, consider apixaban as your first-line treatment, with some caveats,” he said.

Clinical decision rule for penicillin allergy

With fewer than 10% of patients who report a penicillin allergy actually testing positive on a standard allergy test, a simpler way to predict an allergy would help clinicians, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

A 622-patient cohort that had undergone penicillin allergy testing was used to identify factors that could help predict an allergy. A scoring system called PEN-FAST was developed based on five factors – a penicillin allergy reported by the patient, 5 years or less since the last reaction (2 points); anaphylaxis or angioedema, or severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2 points); and treatment being required for the reaction (1 point).

Researchers, after validation at three sites, found that a score below a threshold identified a group that had a 96% negative predictive value for penicillin allergy skin testing.

“A PEN-FAST score of less than 3 can be used to identify patients with reported penicillin allergy who can likely proceed safely to oral challenge,” Dr. Herzig said. She said the findings would benefit from validation in an inpatient setting.

Prehydration before contrast-enhanced computed tomography in CKD

Previous studies have found that omitting prehydration was noninferior to volume expansion with isotonic saline, and this trial looked at omission versus sodium bicarbonate hydration.

Participants were 523 adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease who were getting elective outpatient CT with contrast. They were randomized to either no prehydration or prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate an hour before CT.

Researchers found that postcontrast acute kidney injury was rare even in this high-risk patient population overall, and that withholding prehydration was noninferior to prehydration with sodium bicarbonate, Dr. Herzig said.

Gabapentin for alcohol use disorder in those with alcohol withdrawal symptoms

Dr. Breu noted that only about one in five patients with alcohol use disorder receive medications to help preserve abstinence or to reduce drinking, and many medications target cravings but not symptoms of withdrawal.

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial at a single academic outpatient medical center in South Carolina, 90 patients were randomized to receive titrated gabapentin or placebo for 16 weeks.

Researchers found that, among those with abstinence of at least 2 days, gabapentin reduced the number of days of heavy drinking and the days of any drinking, especially in those with high symptoms of withdrawal.

“In patients with alcohol use disorder and high alcohol withdrawal symptoms, consider gabapentin to help reduce heavy drinking or maintain abstinence,” Dr. Breu said.

Hospitalist continuity of care and patient outcomes

In a retrospective study examining all medical admissions of Medicare patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay, and in which all general medical care was provided by hospitalists, researchers examined the effects of continuity of care. Nearly 115,000 patient stays were included in the study, which covered 229 Texas hospitals.

The stays were grouped into quartiles of continuity of care, based on the number of hospitalists involved in a patient’s stay. Greater continuity was associated with lower 30-day mortality, with a linear relationship between the two. Researchers also found costs to be lower as continuity increased.

“Efforts by hospitals and hospitalist groups to promote working schedules with more continuity,” Dr. Herzig said, “could lead to improved postdischarge outcomes.”

Two experts scoured the medical journals for the practice-changing research most relevant to hospital medicine in 2020 at a recent session at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The presenters chose findings they considered either practice changing or practice confirming, and in areas over which hospitalists have at least some control. Here is what they highlighted:

IV iron administration before hospital discharge

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial across 121 centers in Europe, South America, and Singapore, 1,108 patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and iron deficiency were randomized to receive intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or placebo, with a first dose before discharge and a second at 6 weeks.

Those in the intravenous iron group had a significant reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure up to 52 weeks after randomization, but there was no significant reduction in deaths because of heart failure. There was no difference in serious adverse events.

Anthony Breu, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said the findings should alter hospitalist practice.

“In patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%, check iron studies and start IV iron prior to discharge if they have iron deficiency, with or without anemia,” he said.

Apixaban versus dalteparin for venous thromboembolism in cancer

This noninferiority trial involved 1,155 adults with cancer who had symptomatic or incidental acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The patients were randomized to receive oral apixaban or subcutaneous dalteparin for 6 months.

Patients in the apixaban group had a significantly lower rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism (P = .09), with no increase in major bleeds, Dr. Breu said. He noted that those with brain cancer and leukemia were excluded.

“In patients with cancer and acute venous thromboembolism, consider apixaban as your first-line treatment, with some caveats,” he said.

Clinical decision rule for penicillin allergy

With fewer than 10% of patients who report a penicillin allergy actually testing positive on a standard allergy test, a simpler way to predict an allergy would help clinicians, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

A 622-patient cohort that had undergone penicillin allergy testing was used to identify factors that could help predict an allergy. A scoring system called PEN-FAST was developed based on five factors – a penicillin allergy reported by the patient, 5 years or less since the last reaction (2 points); anaphylaxis or angioedema, or severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2 points); and treatment being required for the reaction (1 point).

Researchers, after validation at three sites, found that a score below a threshold identified a group that had a 96% negative predictive value for penicillin allergy skin testing.

“A PEN-FAST score of less than 3 can be used to identify patients with reported penicillin allergy who can likely proceed safely to oral challenge,” Dr. Herzig said. She said the findings would benefit from validation in an inpatient setting.

Prehydration before contrast-enhanced computed tomography in CKD

Previous studies have found that omitting prehydration was noninferior to volume expansion with isotonic saline, and this trial looked at omission versus sodium bicarbonate hydration.

Participants were 523 adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease who were getting elective outpatient CT with contrast. They were randomized to either no prehydration or prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate an hour before CT.

Researchers found that postcontrast acute kidney injury was rare even in this high-risk patient population overall, and that withholding prehydration was noninferior to prehydration with sodium bicarbonate, Dr. Herzig said.

Gabapentin for alcohol use disorder in those with alcohol withdrawal symptoms

Dr. Breu noted that only about one in five patients with alcohol use disorder receive medications to help preserve abstinence or to reduce drinking, and many medications target cravings but not symptoms of withdrawal.

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial at a single academic outpatient medical center in South Carolina, 90 patients were randomized to receive titrated gabapentin or placebo for 16 weeks.

Researchers found that, among those with abstinence of at least 2 days, gabapentin reduced the number of days of heavy drinking and the days of any drinking, especially in those with high symptoms of withdrawal.

“In patients with alcohol use disorder and high alcohol withdrawal symptoms, consider gabapentin to help reduce heavy drinking or maintain abstinence,” Dr. Breu said.

Hospitalist continuity of care and patient outcomes

In a retrospective study examining all medical admissions of Medicare patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay, and in which all general medical care was provided by hospitalists, researchers examined the effects of continuity of care. Nearly 115,000 patient stays were included in the study, which covered 229 Texas hospitals.

The stays were grouped into quartiles of continuity of care, based on the number of hospitalists involved in a patient’s stay. Greater continuity was associated with lower 30-day mortality, with a linear relationship between the two. Researchers also found costs to be lower as continuity increased.

“Efforts by hospitals and hospitalist groups to promote working schedules with more continuity,” Dr. Herzig said, “could lead to improved postdischarge outcomes.”

Two experts scoured the medical journals for the practice-changing research most relevant to hospital medicine in 2020 at a recent session at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The presenters chose findings they considered either practice changing or practice confirming, and in areas over which hospitalists have at least some control. Here is what they highlighted:

IV iron administration before hospital discharge

In a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial across 121 centers in Europe, South America, and Singapore, 1,108 patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and iron deficiency were randomized to receive intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or placebo, with a first dose before discharge and a second at 6 weeks.

Those in the intravenous iron group had a significant reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure up to 52 weeks after randomization, but there was no significant reduction in deaths because of heart failure. There was no difference in serious adverse events.

Anthony Breu, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said the findings should alter hospitalist practice.

“In patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%, check iron studies and start IV iron prior to discharge if they have iron deficiency, with or without anemia,” he said.

Apixaban versus dalteparin for venous thromboembolism in cancer

This noninferiority trial involved 1,155 adults with cancer who had symptomatic or incidental acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The patients were randomized to receive oral apixaban or subcutaneous dalteparin for 6 months.

Patients in the apixaban group had a significantly lower rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism (P = .09), with no increase in major bleeds, Dr. Breu said. He noted that those with brain cancer and leukemia were excluded.

“In patients with cancer and acute venous thromboembolism, consider apixaban as your first-line treatment, with some caveats,” he said.

Clinical decision rule for penicillin allergy

With fewer than 10% of patients who report a penicillin allergy actually testing positive on a standard allergy test, a simpler way to predict an allergy would help clinicians, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

A 622-patient cohort that had undergone penicillin allergy testing was used to identify factors that could help predict an allergy. A scoring system called PEN-FAST was developed based on five factors – a penicillin allergy reported by the patient, 5 years or less since the last reaction (2 points); anaphylaxis or angioedema, or severe cutaneous adverse reaction (2 points); and treatment being required for the reaction (1 point).

Researchers, after validation at three sites, found that a score below a threshold identified a group that had a 96% negative predictive value for penicillin allergy skin testing.

“A PEN-FAST score of less than 3 can be used to identify patients with reported penicillin allergy who can likely proceed safely to oral challenge,” Dr. Herzig said. She said the findings would benefit from validation in an inpatient setting.

Prehydration before contrast-enhanced computed tomography in CKD

Previous studies have found that omitting prehydration was noninferior to volume expansion with isotonic saline, and this trial looked at omission versus sodium bicarbonate hydration.

Participants were 523 adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease who were getting elective outpatient CT with contrast. They were randomized to either no prehydration or prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate an hour before CT.

Researchers found that postcontrast acute kidney injury was rare even in this high-risk patient population overall, and that withholding prehydration was noninferior to prehydration with sodium bicarbonate, Dr. Herzig said.

Gabapentin for alcohol use disorder in those with alcohol withdrawal symptoms

Dr. Breu noted that only about one in five patients with alcohol use disorder receive medications to help preserve abstinence or to reduce drinking, and many medications target cravings but not symptoms of withdrawal.

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial at a single academic outpatient medical center in South Carolina, 90 patients were randomized to receive titrated gabapentin or placebo for 16 weeks.

Researchers found that, among those with abstinence of at least 2 days, gabapentin reduced the number of days of heavy drinking and the days of any drinking, especially in those with high symptoms of withdrawal.

“In patients with alcohol use disorder and high alcohol withdrawal symptoms, consider gabapentin to help reduce heavy drinking or maintain abstinence,” Dr. Breu said.

Hospitalist continuity of care and patient outcomes

In a retrospective study examining all medical admissions of Medicare patients with a 3- to 6-day length of stay, and in which all general medical care was provided by hospitalists, researchers examined the effects of continuity of care. Nearly 115,000 patient stays were included in the study, which covered 229 Texas hospitals.

The stays were grouped into quartiles of continuity of care, based on the number of hospitalists involved in a patient’s stay. Greater continuity was associated with lower 30-day mortality, with a linear relationship between the two. Researchers also found costs to be lower as continuity increased.

“Efforts by hospitals and hospitalist groups to promote working schedules with more continuity,” Dr. Herzig said, “could lead to improved postdischarge outcomes.”

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

COVID-19 in children and adolescents: Disease burden and severity

My first thought on this column was maybe Pediatric News has written sufficiently about SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it is time to move on. However, the agenda for the May 12th Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice includes a review of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine safety and immunogenicity data for the 12- to 15-year-old age cohort that suggests the potential for vaccine availability and roll out for early adolescents in the near future and the need for up-to-date knowledge about the incidence, severity, and long-term outcome of COVID-19 in the pediatric population.

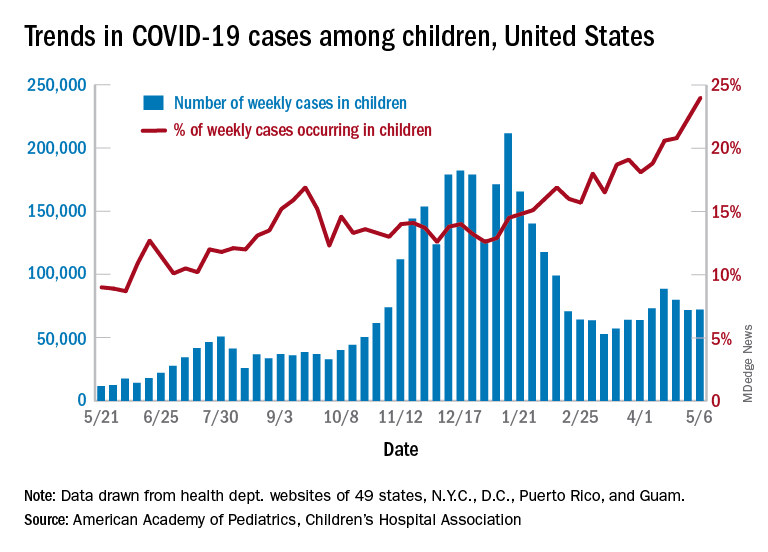

Updating and summarizing the pediatric experience for the pediatric community on what children and adolescents have experienced because of SARS-CoV-2 infection is critical to address the myriad of questions that will come from colleagues, parents, and adolescents themselves. A great resource, published weekly, is the joint report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.1 As of April 29, 2021, 3,782,724 total child COVID-19 cases have been reported from 49 states, New York City (NYC), the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Children represent approximately 14% of cases in the United States and not surprisingly are an increasing proportion of total cases as vaccine impact reduces cases among older age groups. Nearly 5% of the pediatric population has already been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Fortunately, compared with adults, hospitalization, severe disease, and mortality remain far lower both in number and proportion than in the adult population. Cumulative hospitalizations from 24 states and NYC total 15,456 (0.8%) among those infected, with 303 deaths reported (from 43 states, NYC, Guam, and Puerto Rico). Case fatality rate approximates 0.01% in the most recent summary of state reports. One of the limitations of this report is that each state decides how to report the age distribution of COVID-19 cases resulting in variation in age range; another is the data are limited to those details individual states chose to make publicly available.

Although children do not commonly develop severe disease, and the case fatality is low, there are still insights to be learned from understanding risk features for severe disease. Preston et al. reviewed discharge data from 869 medical facilities to describe patients 18 years or younger who had an inpatient or emergency department encounter with a primary or secondary COVID-19 discharge diagnosis from March 1 through October 31, 2020.2 They reported that approximately 2,430 (11.7%) children were hospitalized and 746, nearly 31% of those hospitalized, had severe COVID disease. Those at greatest risk for severe disease were children with comorbid conditions and those less than 12 years, compared with the 12- to 18-year age group. They did not identify race as a risk for severe disease in this study. Moreira et al. described risk factors for morbidity and death from COVID in children less than 18 years of age3 using CDC COVID-NET, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19–associated hospitalization surveillance network. They reported a hospitalization rate of 4.7% among 27,045 cases. They identified three risk factors for hospitalization – age, race/ethnicity, and comorbid conditions. Thirty-nine children (0.19%) died; children who were black, non-Hispanic, and those with an underlying medical condition had a significantly increased risk of death. Thirty-three (85%) children who died had a comorbidity, and 27 (69%) were African American or Hispanic/Latino. The U.S. experience in children is also consistent with reports from the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Germany, France, and South Korea.4 Deaths from COVID-19 were uncommon but relatively more frequent in older children, compared with younger age groups among children less than 18 years of age in these countries.

Acute COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) do not predominantly target the neurologic systems; however, neurologic complications have been reported, some of which appear to result in long-lasting disability. LaRovere et al. identified 354 (22%) of 1,695 patients less than 21 years of age with acute COVID or MIS-C who had neurologic signs or symptoms during their illness. Among those with neurologic involvement, most children had prior neurologic deficits, mild symptoms, that resolved by the time of discharge. Forty-three (12%) were considered life threatening and included severe encephalopathy, stroke, central nervous system infection/demyelination, Guillain-Barre syndrome or variant, or acute cerebral edema. Several children, including some who were previously healthy prior to COVID, had persistent neurologic deficits at discharge. In addition to neurologic morbidity, long COVID – a syndrome of persistent symptoms following acute COVID that lasts for more than 12 weeks without alternative diagnosis – has also been described in children. Buonsenso et al. assessed 129 children diagnosed with COVID-19 between March and November 2020 in Rome, Italy.5 Persisting symptoms after 120 days were reported by more than 50%. Symptoms like fatigue, muscle and joint pain, headache, insomnia, respiratory problems, and palpitations were most common. Clearly, further follow-up of the long-term outcomes is necessary to understand the full spectrum of morbidity resulting from COVID-19 disease in children and its natural history.

The current picture of COVID infection in children younger than 18 reinforces that children are part of the pandemic. Although deaths in children have now exceeded 300 cases, severe disease remains uncommon in both the United States and western Europe. Risk factors for severe disease include comorbid illness and race/ethnicity with a disproportionate number of severe cases in children with underlying comorbidity and in African American and Hispanic/Latino children. Ongoing surveillance is critical as changes are likely to be observed over time as viral evolution affects disease burden and characteristics.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University schools of medicine and public health and senior attending physician in pediatric infectious diseases, Boston Medical Center. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. Services AAP.org.

2. Preston LE et al. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(4):e215298. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5298

3. Moreira A et al. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1659-63.

4. SS Bhopal et al. Lancet 2021. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-4642(21)00066-3.

5. Buonsenso D et al. medRxiv preprint. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.23.21250375.

My first thought on this column was maybe Pediatric News has written sufficiently about SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it is time to move on. However, the agenda for the May 12th Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice includes a review of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine safety and immunogenicity data for the 12- to 15-year-old age cohort that suggests the potential for vaccine availability and roll out for early adolescents in the near future and the need for up-to-date knowledge about the incidence, severity, and long-term outcome of COVID-19 in the pediatric population.

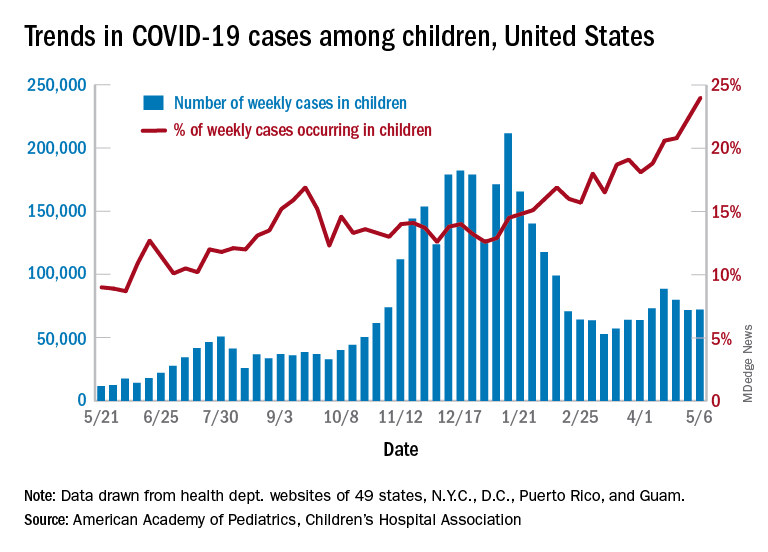

Updating and summarizing the pediatric experience for the pediatric community on what children and adolescents have experienced because of SARS-CoV-2 infection is critical to address the myriad of questions that will come from colleagues, parents, and adolescents themselves. A great resource, published weekly, is the joint report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.1 As of April 29, 2021, 3,782,724 total child COVID-19 cases have been reported from 49 states, New York City (NYC), the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Children represent approximately 14% of cases in the United States and not surprisingly are an increasing proportion of total cases as vaccine impact reduces cases among older age groups. Nearly 5% of the pediatric population has already been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Fortunately, compared with adults, hospitalization, severe disease, and mortality remain far lower both in number and proportion than in the adult population. Cumulative hospitalizations from 24 states and NYC total 15,456 (0.8%) among those infected, with 303 deaths reported (from 43 states, NYC, Guam, and Puerto Rico). Case fatality rate approximates 0.01% in the most recent summary of state reports. One of the limitations of this report is that each state decides how to report the age distribution of COVID-19 cases resulting in variation in age range; another is the data are limited to those details individual states chose to make publicly available.

Although children do not commonly develop severe disease, and the case fatality is low, there are still insights to be learned from understanding risk features for severe disease. Preston et al. reviewed discharge data from 869 medical facilities to describe patients 18 years or younger who had an inpatient or emergency department encounter with a primary or secondary COVID-19 discharge diagnosis from March 1 through October 31, 2020.2 They reported that approximately 2,430 (11.7%) children were hospitalized and 746, nearly 31% of those hospitalized, had severe COVID disease. Those at greatest risk for severe disease were children with comorbid conditions and those less than 12 years, compared with the 12- to 18-year age group. They did not identify race as a risk for severe disease in this study. Moreira et al. described risk factors for morbidity and death from COVID in children less than 18 years of age3 using CDC COVID-NET, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19–associated hospitalization surveillance network. They reported a hospitalization rate of 4.7% among 27,045 cases. They identified three risk factors for hospitalization – age, race/ethnicity, and comorbid conditions. Thirty-nine children (0.19%) died; children who were black, non-Hispanic, and those with an underlying medical condition had a significantly increased risk of death. Thirty-three (85%) children who died had a comorbidity, and 27 (69%) were African American or Hispanic/Latino. The U.S. experience in children is also consistent with reports from the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Germany, France, and South Korea.4 Deaths from COVID-19 were uncommon but relatively more frequent in older children, compared with younger age groups among children less than 18 years of age in these countries.

Acute COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) do not predominantly target the neurologic systems; however, neurologic complications have been reported, some of which appear to result in long-lasting disability. LaRovere et al. identified 354 (22%) of 1,695 patients less than 21 years of age with acute COVID or MIS-C who had neurologic signs or symptoms during their illness. Among those with neurologic involvement, most children had prior neurologic deficits, mild symptoms, that resolved by the time of discharge. Forty-three (12%) were considered life threatening and included severe encephalopathy, stroke, central nervous system infection/demyelination, Guillain-Barre syndrome or variant, or acute cerebral edema. Several children, including some who were previously healthy prior to COVID, had persistent neurologic deficits at discharge. In addition to neurologic morbidity, long COVID – a syndrome of persistent symptoms following acute COVID that lasts for more than 12 weeks without alternative diagnosis – has also been described in children. Buonsenso et al. assessed 129 children diagnosed with COVID-19 between March and November 2020 in Rome, Italy.5 Persisting symptoms after 120 days were reported by more than 50%. Symptoms like fatigue, muscle and joint pain, headache, insomnia, respiratory problems, and palpitations were most common. Clearly, further follow-up of the long-term outcomes is necessary to understand the full spectrum of morbidity resulting from COVID-19 disease in children and its natural history.

The current picture of COVID infection in children younger than 18 reinforces that children are part of the pandemic. Although deaths in children have now exceeded 300 cases, severe disease remains uncommon in both the United States and western Europe. Risk factors for severe disease include comorbid illness and race/ethnicity with a disproportionate number of severe cases in children with underlying comorbidity and in African American and Hispanic/Latino children. Ongoing surveillance is critical as changes are likely to be observed over time as viral evolution affects disease burden and characteristics.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University schools of medicine and public health and senior attending physician in pediatric infectious diseases, Boston Medical Center. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. Services AAP.org.

2. Preston LE et al. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(4):e215298. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5298

3. Moreira A et al. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1659-63.

4. SS Bhopal et al. Lancet 2021. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-4642(21)00066-3.

5. Buonsenso D et al. medRxiv preprint. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.23.21250375.

My first thought on this column was maybe Pediatric News has written sufficiently about SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it is time to move on. However, the agenda for the May 12th Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice includes a review of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine safety and immunogenicity data for the 12- to 15-year-old age cohort that suggests the potential for vaccine availability and roll out for early adolescents in the near future and the need for up-to-date knowledge about the incidence, severity, and long-term outcome of COVID-19 in the pediatric population.

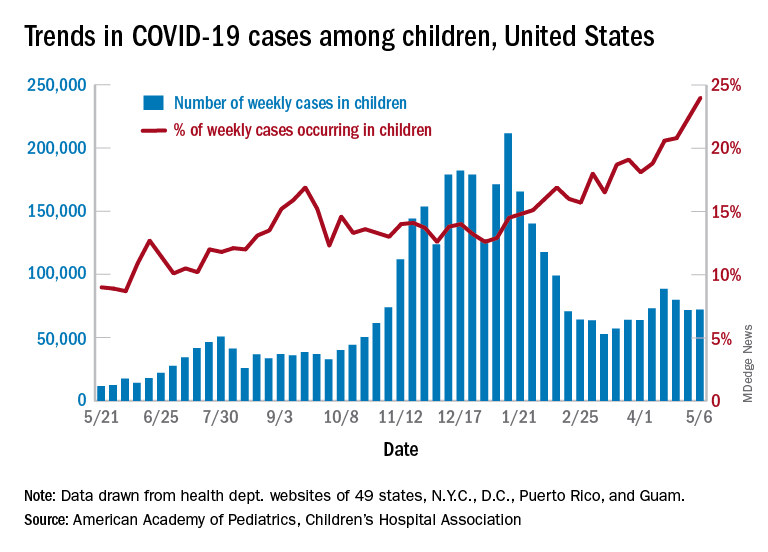

Updating and summarizing the pediatric experience for the pediatric community on what children and adolescents have experienced because of SARS-CoV-2 infection is critical to address the myriad of questions that will come from colleagues, parents, and adolescents themselves. A great resource, published weekly, is the joint report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.1 As of April 29, 2021, 3,782,724 total child COVID-19 cases have been reported from 49 states, New York City (NYC), the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Children represent approximately 14% of cases in the United States and not surprisingly are an increasing proportion of total cases as vaccine impact reduces cases among older age groups. Nearly 5% of the pediatric population has already been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Fortunately, compared with adults, hospitalization, severe disease, and mortality remain far lower both in number and proportion than in the adult population. Cumulative hospitalizations from 24 states and NYC total 15,456 (0.8%) among those infected, with 303 deaths reported (from 43 states, NYC, Guam, and Puerto Rico). Case fatality rate approximates 0.01% in the most recent summary of state reports. One of the limitations of this report is that each state decides how to report the age distribution of COVID-19 cases resulting in variation in age range; another is the data are limited to those details individual states chose to make publicly available.

Although children do not commonly develop severe disease, and the case fatality is low, there are still insights to be learned from understanding risk features for severe disease. Preston et al. reviewed discharge data from 869 medical facilities to describe patients 18 years or younger who had an inpatient or emergency department encounter with a primary or secondary COVID-19 discharge diagnosis from March 1 through October 31, 2020.2 They reported that approximately 2,430 (11.7%) children were hospitalized and 746, nearly 31% of those hospitalized, had severe COVID disease. Those at greatest risk for severe disease were children with comorbid conditions and those less than 12 years, compared with the 12- to 18-year age group. They did not identify race as a risk for severe disease in this study. Moreira et al. described risk factors for morbidity and death from COVID in children less than 18 years of age3 using CDC COVID-NET, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19–associated hospitalization surveillance network. They reported a hospitalization rate of 4.7% among 27,045 cases. They identified three risk factors for hospitalization – age, race/ethnicity, and comorbid conditions. Thirty-nine children (0.19%) died; children who were black, non-Hispanic, and those with an underlying medical condition had a significantly increased risk of death. Thirty-three (85%) children who died had a comorbidity, and 27 (69%) were African American or Hispanic/Latino. The U.S. experience in children is also consistent with reports from the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Germany, France, and South Korea.4 Deaths from COVID-19 were uncommon but relatively more frequent in older children, compared with younger age groups among children less than 18 years of age in these countries.

Acute COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) do not predominantly target the neurologic systems; however, neurologic complications have been reported, some of which appear to result in long-lasting disability. LaRovere et al. identified 354 (22%) of 1,695 patients less than 21 years of age with acute COVID or MIS-C who had neurologic signs or symptoms during their illness. Among those with neurologic involvement, most children had prior neurologic deficits, mild symptoms, that resolved by the time of discharge. Forty-three (12%) were considered life threatening and included severe encephalopathy, stroke, central nervous system infection/demyelination, Guillain-Barre syndrome or variant, or acute cerebral edema. Several children, including some who were previously healthy prior to COVID, had persistent neurologic deficits at discharge. In addition to neurologic morbidity, long COVID – a syndrome of persistent symptoms following acute COVID that lasts for more than 12 weeks without alternative diagnosis – has also been described in children. Buonsenso et al. assessed 129 children diagnosed with COVID-19 between March and November 2020 in Rome, Italy.5 Persisting symptoms after 120 days were reported by more than 50%. Symptoms like fatigue, muscle and joint pain, headache, insomnia, respiratory problems, and palpitations were most common. Clearly, further follow-up of the long-term outcomes is necessary to understand the full spectrum of morbidity resulting from COVID-19 disease in children and its natural history.

The current picture of COVID infection in children younger than 18 reinforces that children are part of the pandemic. Although deaths in children have now exceeded 300 cases, severe disease remains uncommon in both the United States and western Europe. Risk factors for severe disease include comorbid illness and race/ethnicity with a disproportionate number of severe cases in children with underlying comorbidity and in African American and Hispanic/Latino children. Ongoing surveillance is critical as changes are likely to be observed over time as viral evolution affects disease burden and characteristics.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University schools of medicine and public health and senior attending physician in pediatric infectious diseases, Boston Medical Center. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. Services AAP.org.

2. Preston LE et al. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(4):e215298. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5298

3. Moreira A et al. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1659-63.

4. SS Bhopal et al. Lancet 2021. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-4642(21)00066-3.

5. Buonsenso D et al. medRxiv preprint. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.23.21250375.

Smart prescribing strategies improve antibiotic stewardship

“Antibiotic stewardship is never easy, and sometimes it is very difficult to differentiate what is going on with a patient in the clinical setting,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We know from studies that 20% of hospitalized patients who receive an antibiotic have an adverse drug event from that antibiotic within 30 days,” said Dr. Vaughn.

Dr. Vaughn identified several practical ways in which hospitalists can reduce antibiotic overuse, including in the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Identify asymptomatic bacteriuria

One key area in which hospitalists can improve antibiotic stewardship is in recognizing asymptomatic bacteriuria and the harms associated with treatment, Dr. Vaughn said. For example, a common scenario for hospitalists might involve and 80-year-old woman with dementia, who can provide little in the way of history, and whose chest x-ray can’t rule out an underlying infection. This patient might have a positive urine culture, but no other signs of a urinary tract infection. “We know that asymptomatic bacteriuria is very common in hospitalized patients,” especially elderly women living in nursing home settings, she noted.

In cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria, data show that antibiotic treatment does not improve outcomes, and in fact may increase the risk of subsequent UTI, said Dr. Vaughn. Elderly patients also are at increased risk for developing antibiotic-related adverse events, especially Clostridioides difficile. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is any bacteria in the urine in the absence of signs or symptoms of a UTI, even if lab tests show pyuria, nitrates, and resistant bacteria. These lab results are often associated with inappropriate antibiotic use. “The laboratory tests can’t distinguish between asymptomatic bacteriuria and a UTI, only the symptoms can,” she emphasized.

Contain treatment of community-acquired pneumonia

Another practical point for reducing antibiotics in the hospital setting is to limit treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) to 5 days when possible. Duration matters because for many diseases, shorter durations of antibiotic treatments are just as effective as longer durations based on the latest evidence. “This is a change in dogma,” from previous thinking that patients must complete a full course, and that anything less might promote antibiotic resistance, she said.

“In fact, longer antibiotic durations kill off more healthy, normal flora, select for resistant pathogens, increase the risk of C. difficile, and increase the risk of side effects,” she said.

Ultimately, the right treatment duration for pneumonia depends on several factors including patient factors, disease, clinical stability, and rate of improvement. However, a good rule of thumb is that approximately 89% of CAP patients need only 5 days of antibiotics as long as they are afebrile for 48 hours and have 1 or fewer vital sign abnormalities by day 5 of treatment. “We do need to prescribe longer durations for patients with complications,” she emphasized.

Revisit need for antibiotics at discharge

Hospitalists also can practice antibiotic stewardship by considering four points at patient discharge, said Dr. Vaughn.

First, consider whether antibiotics can be stopped. For example, antibiotics are not needed on discharge if infection is no longer the most likely diagnosis, or if the course of antibiotics has been completed, as is often the case for patients hospitalized with CAP, she noted.

Second, if the antibiotics can’t be stopped at the time of discharge, consider whether the preferred agent is being used. Third, be sure the patient is receiving the minimum duration of antibiotics, and fourth, be sure that the dose, indication, and total planned duration with start and stop dates is written in the discharge summary, said Dr. Vaughn. “This helps with communication to our outpatient providers as well as with education to the patients themselves.”

Bacterial coinfections rare in COVID-19

Dr. Vaughn concluded the session with data from a study she conducted with colleagues on the use of empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial coinfection in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The study included 1,667 patients at 32 hospitals in Michigan. The number of patients treated with antibiotics varied widely among hospitals, from 30% to as much as 90%, Dr. Vaughn said.

“What we found was that more than half of hospitalized patients with COVID (57%) received empiric antibiotic therapy in the first few days of hospitalization,” she said.

However, “despite all the antibiotic use, community-onset bacterial coinfections were rare,” and occurred in only 3.5% of the patients, meaning that the number needed to treat with antibiotics to prevent a single case was about 20.

Predictors of community-onset co-infections in the patients included older age, more severe disease, patients coming from nursing homes, and those with lower BMI or kidney disease, said Dr. Vaughn. She and her team also found that procalcitonin’s positive predictive value was 9.3%, but the negative predictive value was 98.3%, so these patients were extremely likely to have no coinfection.

Dr. Vaughn said that in her practice she might order procalcitonin when considering stopping antibiotics in a patient with COVID-19 and make a decision based on the negative predictive value, but she emphasized that she does not use it in the converse situation to rely on a positive value when deciding whether to start antibiotics in these patients.

Dr. Vaughn had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Antibiotic stewardship is never easy, and sometimes it is very difficult to differentiate what is going on with a patient in the clinical setting,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We know from studies that 20% of hospitalized patients who receive an antibiotic have an adverse drug event from that antibiotic within 30 days,” said Dr. Vaughn.

Dr. Vaughn identified several practical ways in which hospitalists can reduce antibiotic overuse, including in the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Identify asymptomatic bacteriuria

One key area in which hospitalists can improve antibiotic stewardship is in recognizing asymptomatic bacteriuria and the harms associated with treatment, Dr. Vaughn said. For example, a common scenario for hospitalists might involve and 80-year-old woman with dementia, who can provide little in the way of history, and whose chest x-ray can’t rule out an underlying infection. This patient might have a positive urine culture, but no other signs of a urinary tract infection. “We know that asymptomatic bacteriuria is very common in hospitalized patients,” especially elderly women living in nursing home settings, she noted.

In cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria, data show that antibiotic treatment does not improve outcomes, and in fact may increase the risk of subsequent UTI, said Dr. Vaughn. Elderly patients also are at increased risk for developing antibiotic-related adverse events, especially Clostridioides difficile. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is any bacteria in the urine in the absence of signs or symptoms of a UTI, even if lab tests show pyuria, nitrates, and resistant bacteria. These lab results are often associated with inappropriate antibiotic use. “The laboratory tests can’t distinguish between asymptomatic bacteriuria and a UTI, only the symptoms can,” she emphasized.

Contain treatment of community-acquired pneumonia

Another practical point for reducing antibiotics in the hospital setting is to limit treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) to 5 days when possible. Duration matters because for many diseases, shorter durations of antibiotic treatments are just as effective as longer durations based on the latest evidence. “This is a change in dogma,” from previous thinking that patients must complete a full course, and that anything less might promote antibiotic resistance, she said.

“In fact, longer antibiotic durations kill off more healthy, normal flora, select for resistant pathogens, increase the risk of C. difficile, and increase the risk of side effects,” she said.

Ultimately, the right treatment duration for pneumonia depends on several factors including patient factors, disease, clinical stability, and rate of improvement. However, a good rule of thumb is that approximately 89% of CAP patients need only 5 days of antibiotics as long as they are afebrile for 48 hours and have 1 or fewer vital sign abnormalities by day 5 of treatment. “We do need to prescribe longer durations for patients with complications,” she emphasized.

Revisit need for antibiotics at discharge

Hospitalists also can practice antibiotic stewardship by considering four points at patient discharge, said Dr. Vaughn.

First, consider whether antibiotics can be stopped. For example, antibiotics are not needed on discharge if infection is no longer the most likely diagnosis, or if the course of antibiotics has been completed, as is often the case for patients hospitalized with CAP, she noted.

Second, if the antibiotics can’t be stopped at the time of discharge, consider whether the preferred agent is being used. Third, be sure the patient is receiving the minimum duration of antibiotics, and fourth, be sure that the dose, indication, and total planned duration with start and stop dates is written in the discharge summary, said Dr. Vaughn. “This helps with communication to our outpatient providers as well as with education to the patients themselves.”

Bacterial coinfections rare in COVID-19

Dr. Vaughn concluded the session with data from a study she conducted with colleagues on the use of empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial coinfection in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The study included 1,667 patients at 32 hospitals in Michigan. The number of patients treated with antibiotics varied widely among hospitals, from 30% to as much as 90%, Dr. Vaughn said.