User login

TDF preferred in PrEP for Blacks and women, studies indicate

Although the efficacy of two pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimens containing differing prodrug formulations of tenofovir are virtually identical, the balance between benefit and risk tips in favor of the combination using the older formulation, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), a pharmacology researcher said.

An analysis of the pharmacologic profiles of TDF plus emtricitabine (FTC; Truvada and generic) with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) plus FTC (Descovy) shows that the risk of decreased bone mineral density and renal toxicity with TDF are significantly lower than those of weight gain and related metabolic and cardiovascular problems associated with the newer tenofovir formulation TAF, according to pharmacology research fellow Andrew Hill, MD, PhD, from the University of Liverpool (England).

“I think when we’re comparing these two drugs overall, we have a clear benefit/risk, and we need to take both of these potential toxicities seriously, “ he said in an online presentation during IDWeek 2020, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases held virtually this year.

“But in my view, treating women – Black women – with TAF/FTC is a bad thing,” he continued. “I think it’s going lead to more harm, more myocardial infarctions, more cases of diabetes, and potentially more adverse birth outcomes, and I think that is a risk that is not worth taking, given that the apparent benefit in terms of bone mineral density and renal markers is a hypothesis at best, and is not translated into hard clinical endpoints.”

Adverse event profiles

Dr. Hill compared the side effect profiles of the two agents when used both in antiretroviral therapy (ART) in combination the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir (DTG; Tivicay), and in PrEP.

World Health Organization guidelines for first-line ART recommend the use of TDF/FTC/DTG, reserving TAF plus lamivudine (3TC) and DTG for use in special circumstances only, Dr. Hill noted.

He pointed to a pooled analysis of data from eight randomized, controlled trials of treatment-naive people living with HIV who started on ART from 2003 to 2015. The authors found that demographic factors associated with weight gain included lower CD4 cell counter, higher levels of HIV type 1 RNA, no injection drug use, female sex, and Black race.

They also found that, among nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, TAF was associated with more weight gain than TDF, abacavir, or zidovudine.

“This pattern is seen consistently across studies both of pre-exposure prophylaxis or treatment comparing tenofovir with either TAF or other nucleoside analogs,” he said.

The greater weight gain with TAF versus TDF was seen in both treatment trials and in the DISCOVER PrEP trial.

In addition, in a crossover trial conducted in Germany, patients who switched from TDF to TAF had an approximately 2 kg increase in body weight.

TAF has also been associated with higher grade 3 or 4 glucose and LDL cholesterol than TDF in clinical trials for the treatment of hepatitis B infections, and with higher LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol levels as well as diabetes in patients treated with the drugs in combination in the EMERALD HIV trial.

Clinical trials also tend to underestimate the real-world population of persons at highest risk for adverse events from TAF, Dr. Hill said, noting that the percentage of Black women in phase 3 trials for dolutegravir was 9%, compared with 42% among persons infected with HIV worldwide. The respective percentages for Black men are 16% versus 30%. These differences are similar across clinical trial programs for other ART agents.

“Generally, it’s women and Black people who seem to be at greatest risk for safety issues,” he said.

In the ADVANCE trial comparing TAF/FTC/DTG with TDF/FTC/DTG and a control arm of TDF, FTC and efavirenz, the mean change in weight among men after 3 years on the TAF-based regimen was a gain of 7.2 kg (15.9 lbs), compared with 5.5 kg (12 lbs) with TDF, and 2.6 kg (5.7 lbs) with the efavirenz-containing regimen.

In women enrolled in the same trial, the respective mean weight gains were 12.3 kg (27 lbs), 7.4 kg (16.3 lbs), and 5.5 kg (12 lbs).

“All of our analyses so far have shown that the weight continues to go up. We’re actually seeing people doubling in their body weight. We’ve seen some women come into clinic and their doctors don’t even recognize them because they’ve put on so much weight,” he said.

In women, most of the gain in weight occurs as limb or trunk fat, with a predominance of visceral fat.

People taking TAF in the trial were also at significantly greater risk for developing the metabolic syndrome, and at week 96, 27% of women on TAF/FTC/DTG had treatment-emergent obesity, compared with 17% for those on TDF/FTC/DTG and 11% for those on TDF/FTC/EFV. In men, the respective 96-week rates of treatment-emergent obesity were 7%, 3%, and 2%.

Clinical obesity itself is a risk factor for obstetric complications and birth outcomes, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and cancer, and an average 4-year reduction in life expectancy, Dr. Hill said. “I think it’s actually very unlikely that the [World Health Organization] guidelines will now change and allow the widespread use of TAF/FTC in combination with integrase inhibitors worldwide given these potential implications.”

Modern times

The bad rap that TDF gets for its alleged effects on bone mineral density and kidneys comes from studies where the drug was given in a boosted regimen that can amplify tenofovir toxicities, Dr. Hill said.

He noted that data from Gilead Sciences shows through 7 years of therapy in previously ART-naive patients, the combination of TDF/3TC/EFV showed sustained durable efficacy, no discontinuations to renal adverse effects, and no evidence of clinically relevant bone effects.

“I think we need to be very careful when we look at tenofovir and TAF. We need to look at the more modern way that these drugs are used, which is not with pharmacokinetic boosters anymore, and in that situation the toxicity profile of tenofovir/3TC – the original TDF – is very favorable,” he said.

Robert Goldstein, MD, PhD, an infectious disease specialist and medical director of the transgender health program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who comoderated the session where Dr. Hill presented his data, said that his clinical experience mirrors the pharmacokinetic findings.

“I certainly have strong feelings about the use of TDF in pre-exposure prophylaxis,” he said in an interview. “TDF is an effective and safe formulation of tenofovir to be used in pre-exposure prophylaxis, and one that we have more experience with. It’s the formulation of tenofovir that I use for all of my patients who are on pre-exposure prophylaxis, and I think it is the most cost-effective.’

No funding source was reported. Andrew Hill consults for Tibotec on clinical trial programs for darunavir, etravirine, and rilpivirine. Dr. Goldstein reported having no relevant disclosures.

Although the efficacy of two pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimens containing differing prodrug formulations of tenofovir are virtually identical, the balance between benefit and risk tips in favor of the combination using the older formulation, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), a pharmacology researcher said.

An analysis of the pharmacologic profiles of TDF plus emtricitabine (FTC; Truvada and generic) with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) plus FTC (Descovy) shows that the risk of decreased bone mineral density and renal toxicity with TDF are significantly lower than those of weight gain and related metabolic and cardiovascular problems associated with the newer tenofovir formulation TAF, according to pharmacology research fellow Andrew Hill, MD, PhD, from the University of Liverpool (England).

“I think when we’re comparing these two drugs overall, we have a clear benefit/risk, and we need to take both of these potential toxicities seriously, “ he said in an online presentation during IDWeek 2020, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases held virtually this year.

“But in my view, treating women – Black women – with TAF/FTC is a bad thing,” he continued. “I think it’s going lead to more harm, more myocardial infarctions, more cases of diabetes, and potentially more adverse birth outcomes, and I think that is a risk that is not worth taking, given that the apparent benefit in terms of bone mineral density and renal markers is a hypothesis at best, and is not translated into hard clinical endpoints.”

Adverse event profiles

Dr. Hill compared the side effect profiles of the two agents when used both in antiretroviral therapy (ART) in combination the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir (DTG; Tivicay), and in PrEP.

World Health Organization guidelines for first-line ART recommend the use of TDF/FTC/DTG, reserving TAF plus lamivudine (3TC) and DTG for use in special circumstances only, Dr. Hill noted.

He pointed to a pooled analysis of data from eight randomized, controlled trials of treatment-naive people living with HIV who started on ART from 2003 to 2015. The authors found that demographic factors associated with weight gain included lower CD4 cell counter, higher levels of HIV type 1 RNA, no injection drug use, female sex, and Black race.

They also found that, among nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, TAF was associated with more weight gain than TDF, abacavir, or zidovudine.

“This pattern is seen consistently across studies both of pre-exposure prophylaxis or treatment comparing tenofovir with either TAF or other nucleoside analogs,” he said.

The greater weight gain with TAF versus TDF was seen in both treatment trials and in the DISCOVER PrEP trial.

In addition, in a crossover trial conducted in Germany, patients who switched from TDF to TAF had an approximately 2 kg increase in body weight.

TAF has also been associated with higher grade 3 or 4 glucose and LDL cholesterol than TDF in clinical trials for the treatment of hepatitis B infections, and with higher LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol levels as well as diabetes in patients treated with the drugs in combination in the EMERALD HIV trial.

Clinical trials also tend to underestimate the real-world population of persons at highest risk for adverse events from TAF, Dr. Hill said, noting that the percentage of Black women in phase 3 trials for dolutegravir was 9%, compared with 42% among persons infected with HIV worldwide. The respective percentages for Black men are 16% versus 30%. These differences are similar across clinical trial programs for other ART agents.

“Generally, it’s women and Black people who seem to be at greatest risk for safety issues,” he said.

In the ADVANCE trial comparing TAF/FTC/DTG with TDF/FTC/DTG and a control arm of TDF, FTC and efavirenz, the mean change in weight among men after 3 years on the TAF-based regimen was a gain of 7.2 kg (15.9 lbs), compared with 5.5 kg (12 lbs) with TDF, and 2.6 kg (5.7 lbs) with the efavirenz-containing regimen.

In women enrolled in the same trial, the respective mean weight gains were 12.3 kg (27 lbs), 7.4 kg (16.3 lbs), and 5.5 kg (12 lbs).

“All of our analyses so far have shown that the weight continues to go up. We’re actually seeing people doubling in their body weight. We’ve seen some women come into clinic and their doctors don’t even recognize them because they’ve put on so much weight,” he said.

In women, most of the gain in weight occurs as limb or trunk fat, with a predominance of visceral fat.

People taking TAF in the trial were also at significantly greater risk for developing the metabolic syndrome, and at week 96, 27% of women on TAF/FTC/DTG had treatment-emergent obesity, compared with 17% for those on TDF/FTC/DTG and 11% for those on TDF/FTC/EFV. In men, the respective 96-week rates of treatment-emergent obesity were 7%, 3%, and 2%.

Clinical obesity itself is a risk factor for obstetric complications and birth outcomes, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and cancer, and an average 4-year reduction in life expectancy, Dr. Hill said. “I think it’s actually very unlikely that the [World Health Organization] guidelines will now change and allow the widespread use of TAF/FTC in combination with integrase inhibitors worldwide given these potential implications.”

Modern times

The bad rap that TDF gets for its alleged effects on bone mineral density and kidneys comes from studies where the drug was given in a boosted regimen that can amplify tenofovir toxicities, Dr. Hill said.

He noted that data from Gilead Sciences shows through 7 years of therapy in previously ART-naive patients, the combination of TDF/3TC/EFV showed sustained durable efficacy, no discontinuations to renal adverse effects, and no evidence of clinically relevant bone effects.

“I think we need to be very careful when we look at tenofovir and TAF. We need to look at the more modern way that these drugs are used, which is not with pharmacokinetic boosters anymore, and in that situation the toxicity profile of tenofovir/3TC – the original TDF – is very favorable,” he said.

Robert Goldstein, MD, PhD, an infectious disease specialist and medical director of the transgender health program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who comoderated the session where Dr. Hill presented his data, said that his clinical experience mirrors the pharmacokinetic findings.

“I certainly have strong feelings about the use of TDF in pre-exposure prophylaxis,” he said in an interview. “TDF is an effective and safe formulation of tenofovir to be used in pre-exposure prophylaxis, and one that we have more experience with. It’s the formulation of tenofovir that I use for all of my patients who are on pre-exposure prophylaxis, and I think it is the most cost-effective.’

No funding source was reported. Andrew Hill consults for Tibotec on clinical trial programs for darunavir, etravirine, and rilpivirine. Dr. Goldstein reported having no relevant disclosures.

Although the efficacy of two pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimens containing differing prodrug formulations of tenofovir are virtually identical, the balance between benefit and risk tips in favor of the combination using the older formulation, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), a pharmacology researcher said.

An analysis of the pharmacologic profiles of TDF plus emtricitabine (FTC; Truvada and generic) with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) plus FTC (Descovy) shows that the risk of decreased bone mineral density and renal toxicity with TDF are significantly lower than those of weight gain and related metabolic and cardiovascular problems associated with the newer tenofovir formulation TAF, according to pharmacology research fellow Andrew Hill, MD, PhD, from the University of Liverpool (England).

“I think when we’re comparing these two drugs overall, we have a clear benefit/risk, and we need to take both of these potential toxicities seriously, “ he said in an online presentation during IDWeek 2020, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases held virtually this year.

“But in my view, treating women – Black women – with TAF/FTC is a bad thing,” he continued. “I think it’s going lead to more harm, more myocardial infarctions, more cases of diabetes, and potentially more adverse birth outcomes, and I think that is a risk that is not worth taking, given that the apparent benefit in terms of bone mineral density and renal markers is a hypothesis at best, and is not translated into hard clinical endpoints.”

Adverse event profiles

Dr. Hill compared the side effect profiles of the two agents when used both in antiretroviral therapy (ART) in combination the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir (DTG; Tivicay), and in PrEP.

World Health Organization guidelines for first-line ART recommend the use of TDF/FTC/DTG, reserving TAF plus lamivudine (3TC) and DTG for use in special circumstances only, Dr. Hill noted.

He pointed to a pooled analysis of data from eight randomized, controlled trials of treatment-naive people living with HIV who started on ART from 2003 to 2015. The authors found that demographic factors associated with weight gain included lower CD4 cell counter, higher levels of HIV type 1 RNA, no injection drug use, female sex, and Black race.

They also found that, among nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, TAF was associated with more weight gain than TDF, abacavir, or zidovudine.

“This pattern is seen consistently across studies both of pre-exposure prophylaxis or treatment comparing tenofovir with either TAF or other nucleoside analogs,” he said.

The greater weight gain with TAF versus TDF was seen in both treatment trials and in the DISCOVER PrEP trial.

In addition, in a crossover trial conducted in Germany, patients who switched from TDF to TAF had an approximately 2 kg increase in body weight.

TAF has also been associated with higher grade 3 or 4 glucose and LDL cholesterol than TDF in clinical trials for the treatment of hepatitis B infections, and with higher LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol levels as well as diabetes in patients treated with the drugs in combination in the EMERALD HIV trial.

Clinical trials also tend to underestimate the real-world population of persons at highest risk for adverse events from TAF, Dr. Hill said, noting that the percentage of Black women in phase 3 trials for dolutegravir was 9%, compared with 42% among persons infected with HIV worldwide. The respective percentages for Black men are 16% versus 30%. These differences are similar across clinical trial programs for other ART agents.

“Generally, it’s women and Black people who seem to be at greatest risk for safety issues,” he said.

In the ADVANCE trial comparing TAF/FTC/DTG with TDF/FTC/DTG and a control arm of TDF, FTC and efavirenz, the mean change in weight among men after 3 years on the TAF-based regimen was a gain of 7.2 kg (15.9 lbs), compared with 5.5 kg (12 lbs) with TDF, and 2.6 kg (5.7 lbs) with the efavirenz-containing regimen.

In women enrolled in the same trial, the respective mean weight gains were 12.3 kg (27 lbs), 7.4 kg (16.3 lbs), and 5.5 kg (12 lbs).

“All of our analyses so far have shown that the weight continues to go up. We’re actually seeing people doubling in their body weight. We’ve seen some women come into clinic and their doctors don’t even recognize them because they’ve put on so much weight,” he said.

In women, most of the gain in weight occurs as limb or trunk fat, with a predominance of visceral fat.

People taking TAF in the trial were also at significantly greater risk for developing the metabolic syndrome, and at week 96, 27% of women on TAF/FTC/DTG had treatment-emergent obesity, compared with 17% for those on TDF/FTC/DTG and 11% for those on TDF/FTC/EFV. In men, the respective 96-week rates of treatment-emergent obesity were 7%, 3%, and 2%.

Clinical obesity itself is a risk factor for obstetric complications and birth outcomes, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and cancer, and an average 4-year reduction in life expectancy, Dr. Hill said. “I think it’s actually very unlikely that the [World Health Organization] guidelines will now change and allow the widespread use of TAF/FTC in combination with integrase inhibitors worldwide given these potential implications.”

Modern times

The bad rap that TDF gets for its alleged effects on bone mineral density and kidneys comes from studies where the drug was given in a boosted regimen that can amplify tenofovir toxicities, Dr. Hill said.

He noted that data from Gilead Sciences shows through 7 years of therapy in previously ART-naive patients, the combination of TDF/3TC/EFV showed sustained durable efficacy, no discontinuations to renal adverse effects, and no evidence of clinically relevant bone effects.

“I think we need to be very careful when we look at tenofovir and TAF. We need to look at the more modern way that these drugs are used, which is not with pharmacokinetic boosters anymore, and in that situation the toxicity profile of tenofovir/3TC – the original TDF – is very favorable,” he said.

Robert Goldstein, MD, PhD, an infectious disease specialist and medical director of the transgender health program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who comoderated the session where Dr. Hill presented his data, said that his clinical experience mirrors the pharmacokinetic findings.

“I certainly have strong feelings about the use of TDF in pre-exposure prophylaxis,” he said in an interview. “TDF is an effective and safe formulation of tenofovir to be used in pre-exposure prophylaxis, and one that we have more experience with. It’s the formulation of tenofovir that I use for all of my patients who are on pre-exposure prophylaxis, and I think it is the most cost-effective.’

No funding source was reported. Andrew Hill consults for Tibotec on clinical trial programs for darunavir, etravirine, and rilpivirine. Dr. Goldstein reported having no relevant disclosures.

FROM IDWEEK 2020

Cutaneous Filariasis in an American Traveler

To the Editor:

Cutaneous filariasis is a group of infectious diseases caused by more than 60 different nematode species and endemic to approximately 83 countries.1,2 These infections are transmitted to humans by vectors such as mosquitoes, blackflies, biting midges, or Tabanid flies.1 The blood meal taken by vectors allow microfilariae to enter the skin and develop into adult worms.1-3 It is postulated that filarial infections were first described in 2000

Filarial parasites have been categorized into groups based on the site of adult worm stage habitat. The cutaneous group includes Loa loa, Onchocerca volvulus, Mansonella perstans, and Dipetalonema streptocerca. The lymphatic group includes Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. Lastly, the body cavity group includes Mansonella ozzardi. Because humidity is required for survival of the infective larval stage, individuals from tropical countries in Africa, Central America, and South America most commonly are affected.1 These diseases also are related to poor housing quality and inadequate sanitation.1,3,4 Travel for business, medical missions, pleasure, or emigration has caused increased filarial infections globally. In fact, dermatologic disorders with infectious etiologies cause approximately 17% of travelers to seek medical attention.3

Dermatologic manifestations indicative of a potential cutaneous filarial infection include papules, nodules, excoriations with secondary xerosis, lichenification, skin pigment changes, and/or severe pruritus. However, individuals from filarial endemic regions may not demonstrate any clinical signs or symptoms, despite having microfilariae in their blood,1 which enables the disease to propagate and poses a major public health concern. In fact, patients with chronic filarial infections are at increased risk for developing lymphedema, elephantiasis, or blindness, which are hypothesized to be the second largest cause of permanent disability worldwide.1 Although rarely seen in US citizens, cutaneous filariasis should always be a diagnostic consideration in patients who present with a pruritic eruption and have a travel history to tropical countries. We report a case of cutaneous onchocerciasis in a US citizen who developed a pruritic eczematous eruption on the right upper arm following an arthropod assault while working in an Onchocerca endemic region approximately 1.5 years prior.

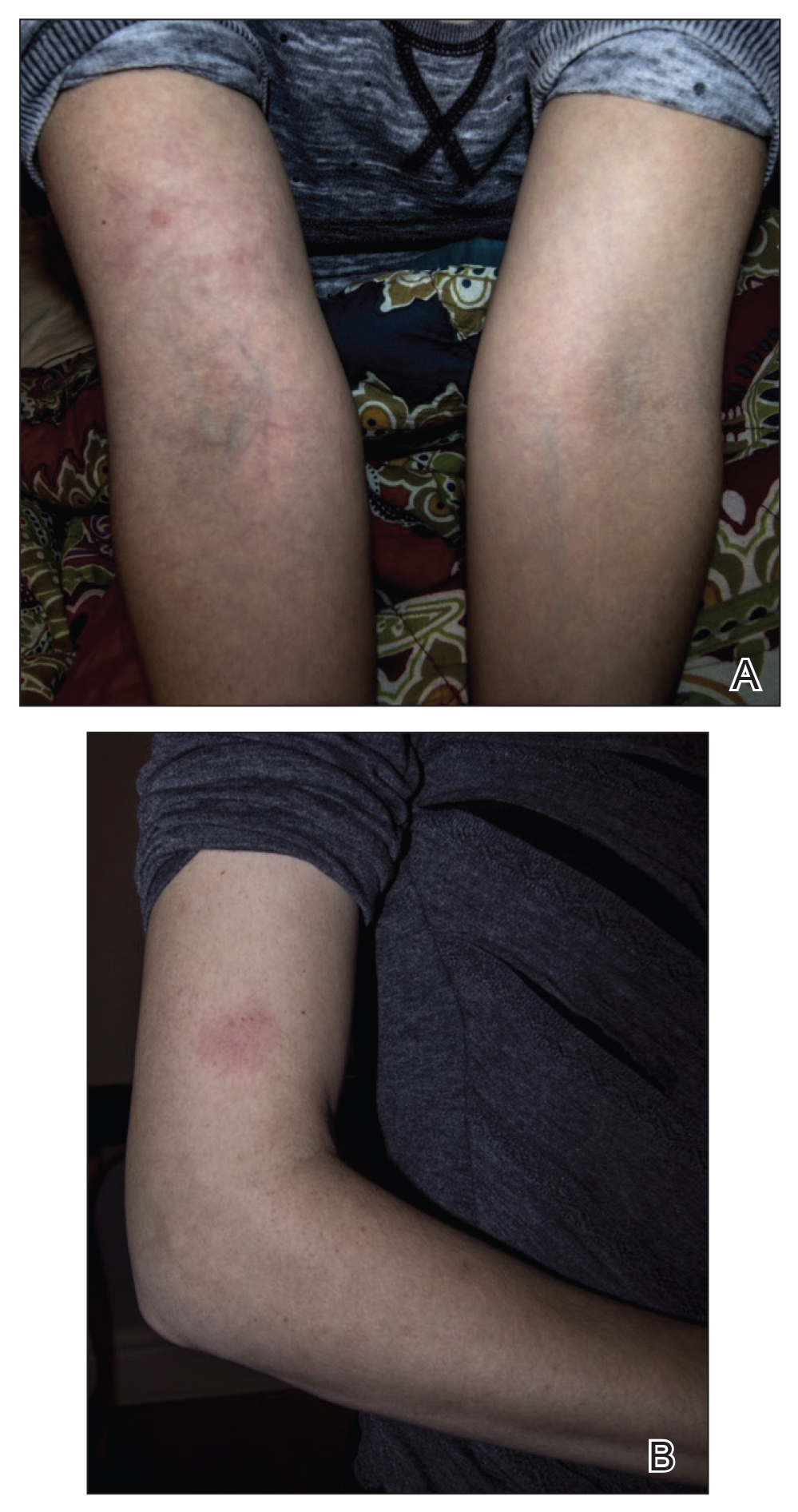

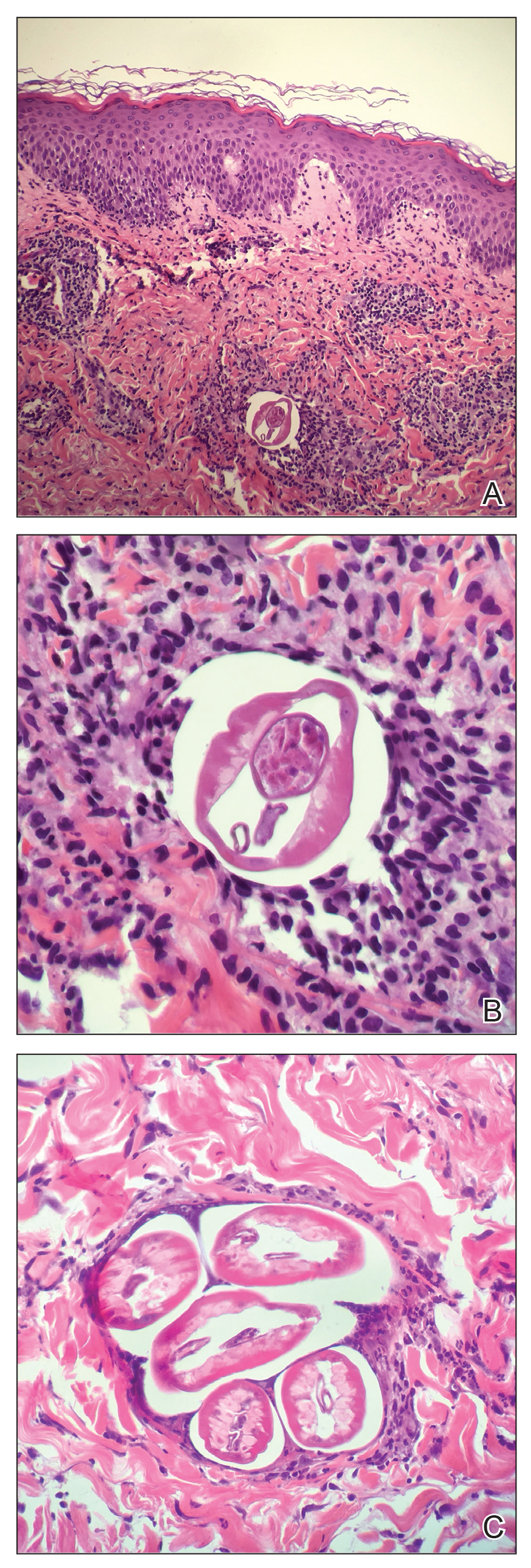

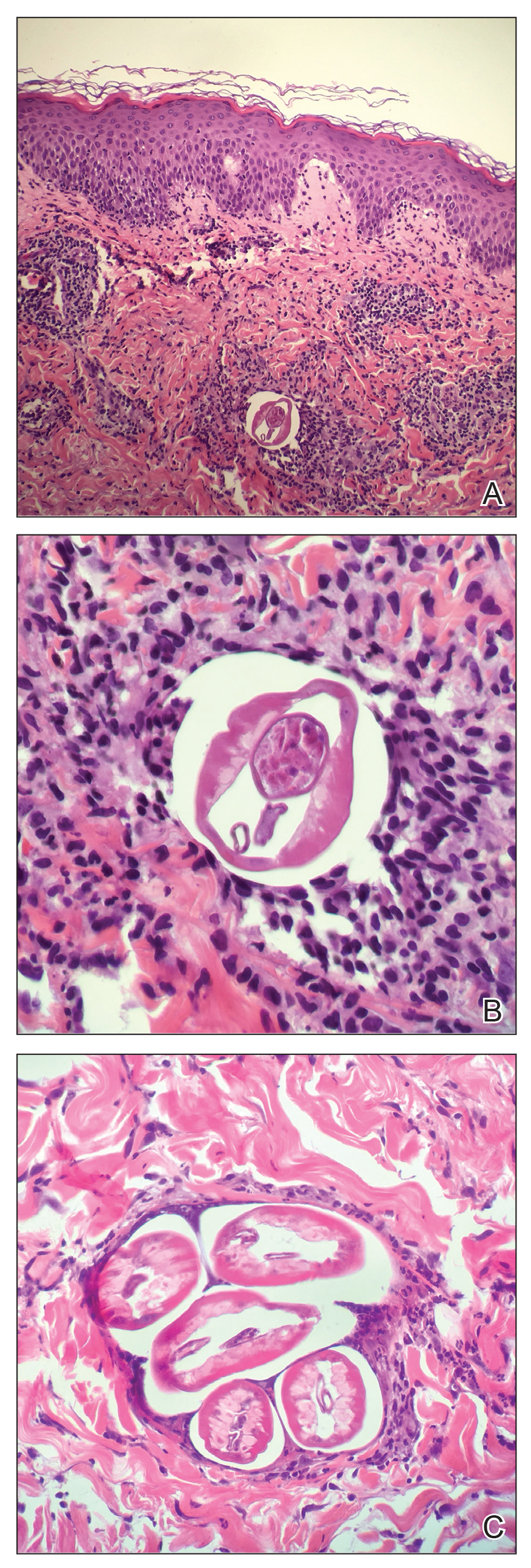

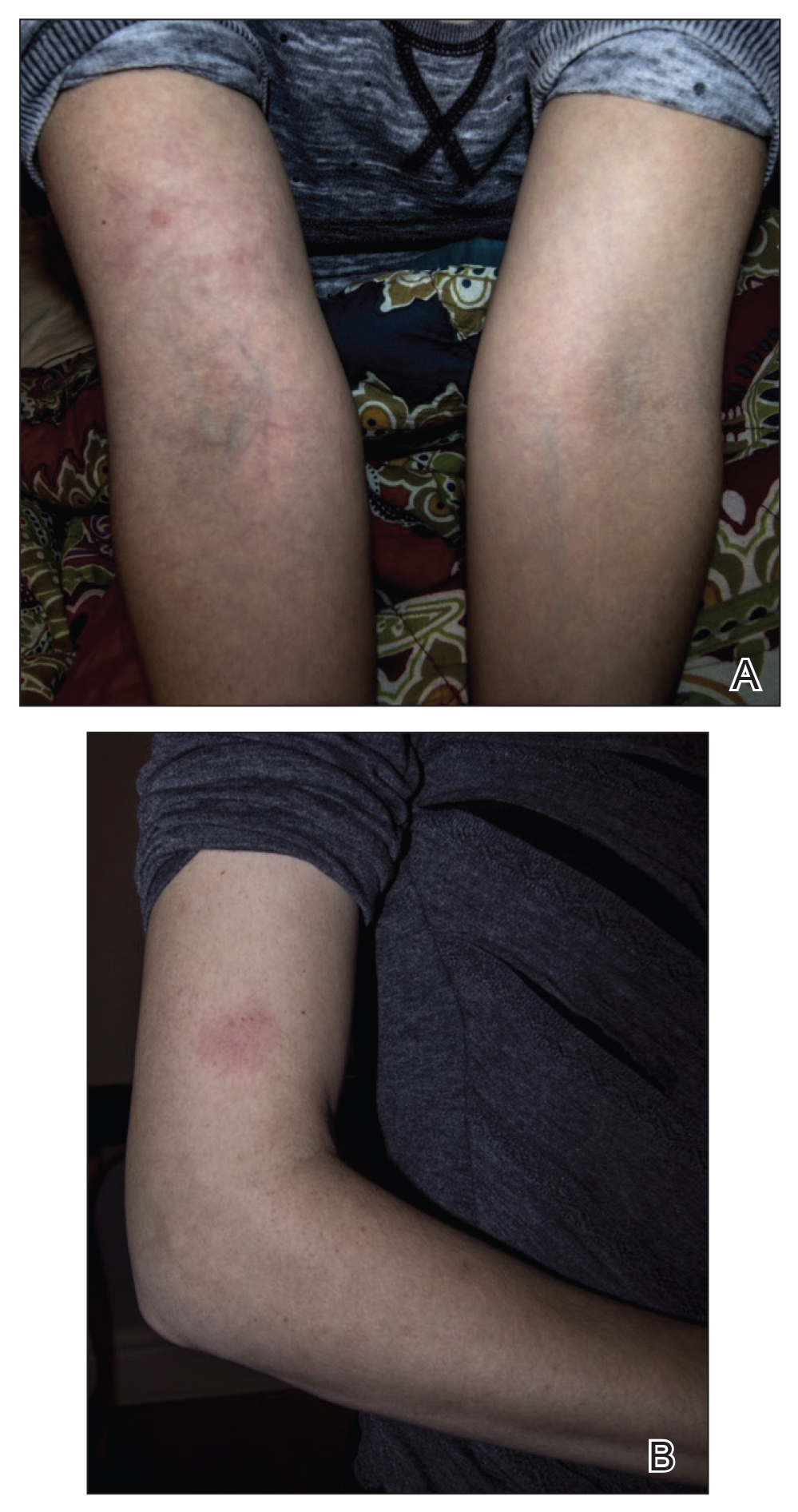

A 33-year-old woman presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic with the chief concern of a pruritic rash on the right arm (Figure 1). She revealed a history of travel to Peru, associated symptoms, prior diagnoses, and attempted treatment regimens. Over a 1.5-year period, the patient traveled for work-related reasons to Madre de Dios, Peru. During that time, the patient experienced 2 bouts of severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that she attributed to poor food and water quality. She did not immediately seek medical attention. She also developed skin manifestations that began as a pruritic and irritating pinpoint-sized red papule on the right eyelid, possibly a site of an arthropod assault. She then experienced episodic eyelash loss (Figure 2) and subsequent vision changes, including blurry vision, halos around lights, and dimming around the periphery. When the patient developed circular, pink, pruritic plaques on the right upper extremity, she sought medical attention in Lima, Peru. She was diagnosed with tinea corporis and prescribed an oral antibiotic and topical antifungal.

This treatment regimen did not result in improvement. In the following months, the patient noticed worsening of the ocular symptoms, and she developed a dry cough with occasional dyspnea. She again sought medical attention in Peru and was referred to an ophthalmologist who suspected Demodex mite or fungal infection; however, workup for those pathologies was negative. The respiratory symptoms continued to worsen, particularly at night, and she began to experience palpitations.

Upon returning to the United States, the patient was evaluated by her primary care physician who ordered the following laboratory tests: a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, vitamin D level, blood culture, lipid panel, ferritin level, and thyroid function. An electrocardiogram, throat culture, and stool culture for ova and parasites also were obtained. The electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia, and the stool culture revealed blastocystis, for which she was prescribed oral metronidazole and tinidazole. The other results were within reference range, and the throat culture showed normal oropharyngeal microbes.

A few days after the treatment for the blastocystis, the gastrointestinal tract symptoms improved, but dermatologic, ocular, pulmonary, and cardiac symptoms persisted. She also began experiencing night sweats and hot flashes. In between visits to the primary care physician, she sought medical attention at an urgent care clinic for worsening pulmonary and cardiac symptoms. At that time, results of a chest radiograph were normal.

The primary care physician referred her to infectious disease and dermatology for further evaluation within a few weeks of returning to the United States. Upon presentation to dermatology, the patient described a waxing and waning nature to the rash on the arm with associated intermittent pain. Physical examination revealed several erythematous patches on the triceps and a 1-cm subcutaneous nodule on the right elbow with overlying skin discoloration. The patient stated that she first noticed the inflamed painful nodule when she returned to the United States. Since its discovery, the nodule increased in size and became firm. The patient also described occasional limited range of motion of the right arm due to the discomfort of the rash and inflamed nodule. Interestingly, the patient’s partner who accompanied her to Peru also developed a similar pruritic rash on the chest. He was evaluated by dermatology and infectious disease; however, biopsies of his rash performed at a different practice revealed nonspecific results. Due to her partner’s inconclusive results, our patient initially refused a biopsy; however, she returned to the office after 1 week with worsening symptoms, and a 4-mm punch biopsy of the right arm was obtained in addition to rapid plasma reagin and QuantiFERON-TB Gold test.

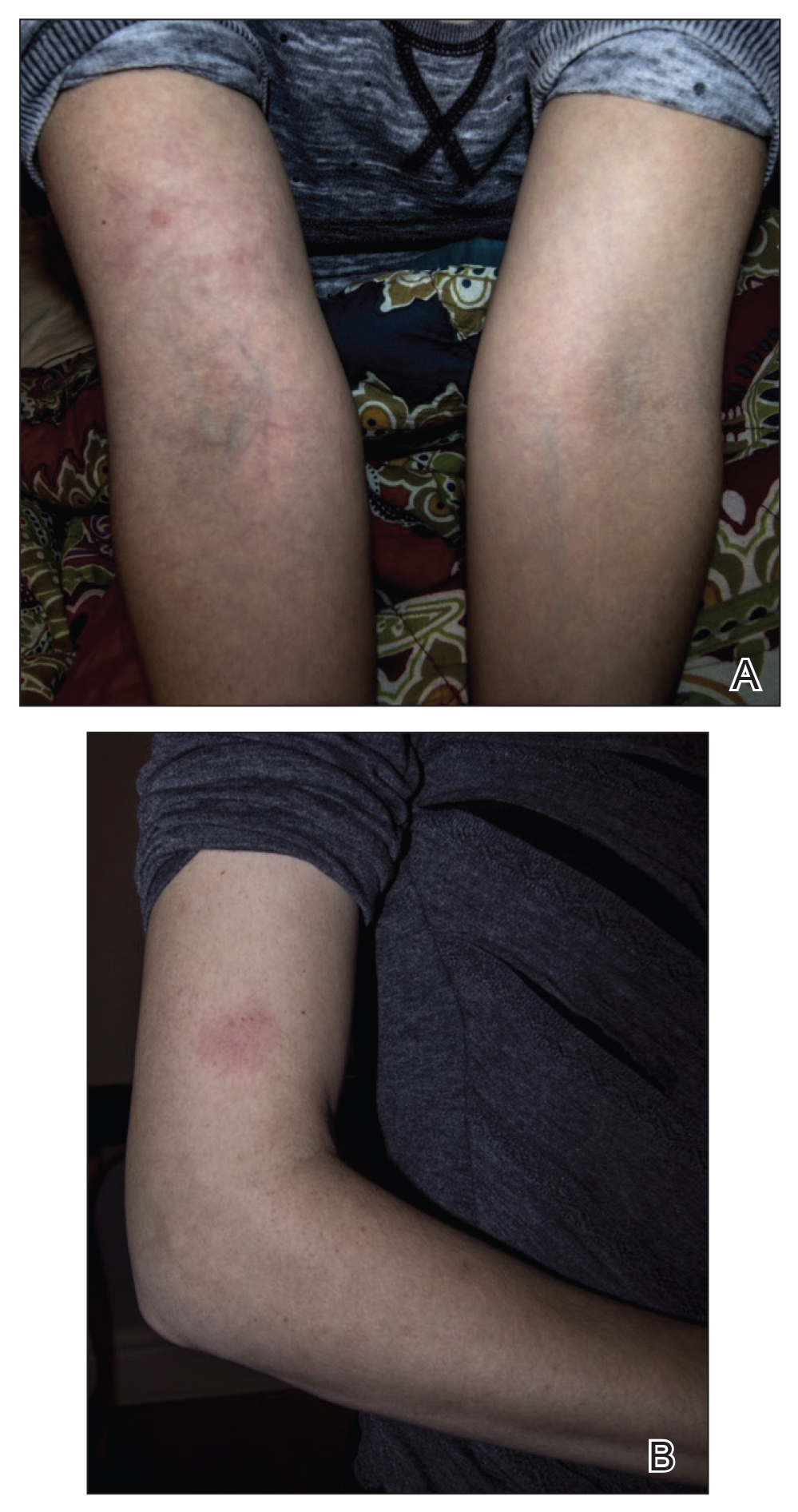

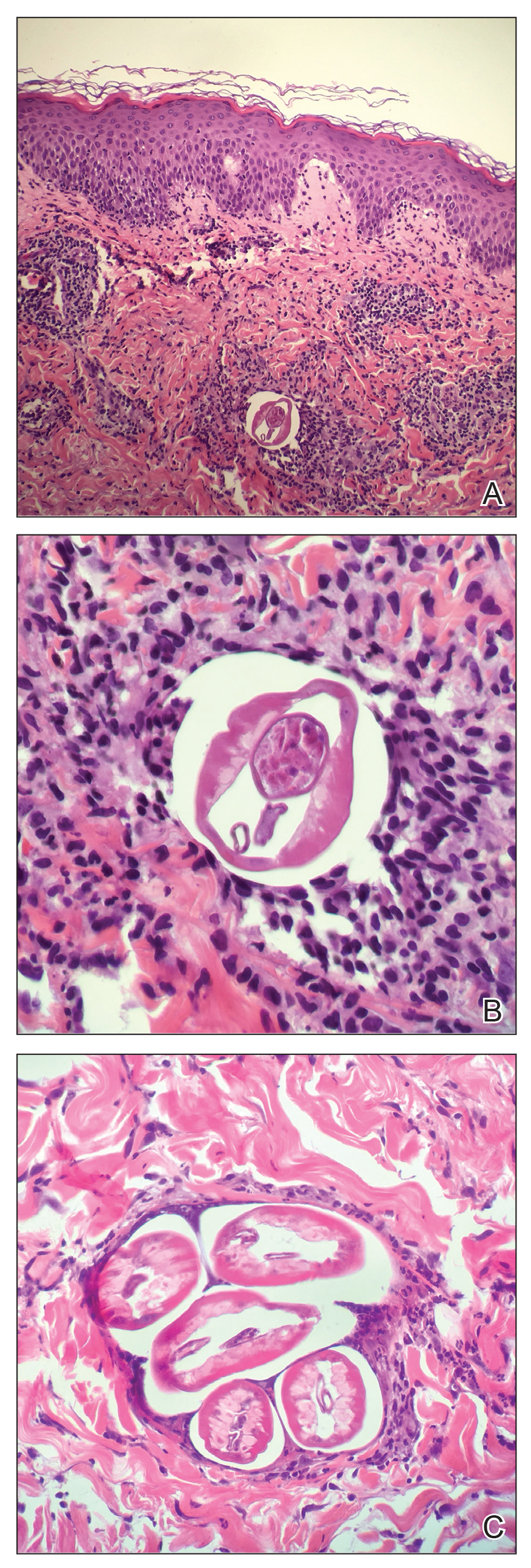

Based on the patient’s travel history, clinical course, and physical examination, the clinical differential diagnosis included nummular dermatitis, panniculitis/nodular vasculitis, tinea corporis, secondary syphilis, pinta, tuberculosis, or cutaneous filariasis. Rapid plasma reagin and QuantiFERON-TB Gold test results were negative, and a periodic acid–Schiff stain of the biopsy was negative for fungal elements. Dermatopathology revealed intradermal filarial nematodes of 120 to 150 µm in diameter and 1-to 2-mm cuticles eliciting a predominantly superficial and deep lymphohistiocytic reaction (Figure 3). The histopathologic differential diagnosis based on the diameter of the nematode included M perstans, W bancrofti, and O volvulus. Clinical correlation was highly recommended to obtain a final diagnosis and management plan. A portion of the biopsy was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which confirmed the presence of a filarial nematode consistent with a zoonotic Brugia but also with zoonotic Onchocerca as a possible differential. Therefore, considering the history, clinical course, and histopathologic analysis, the final diagnosis of cutaneous onchocerciasis was made.

The patient was referred back to infectious disease and started on combination therapy of ivermectin (25.5 mg) plus albendazole (800 mg) taken at once followed by doxycycline (200 mg) for 6 weeks. The symptoms initially worsened, then she experienced near-complete resolution of dermatologic, pulmonary, and ocular symptoms after approximately 2 weeks of treatment. She continued to report fatigue and palpitations, for she continued to see a cardiologist. We highly encouraged her to continue following up with infectious disease to ensure complete eradication of the infection.

Onchocerciasis is common in individuals who live or work in equatorial Africa, Central America, and South America. The disease process has dermatologic, ocular, and other systemic manifestations if the infection continues long-term without treatment.2,5 Although rare, this infection has been observed in US citizens who have traveled to filarial endemic regions for a period of time ranging from 2 weeks to 39 years.2,6,7

Blackflies (genus Simulium), the intermediate host of O volvulus, breed in areas close to freely flowing water. The blackfly bites a human host, and within 7 days the microfilariae undergo 2 molts to reach the infective stage. The larvae remain in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue for 2 additional molts until they develop into adult worms. Then, adult worms may become encapsulated, eliciting and forming subcutaneous nodules, also known as onchocercomas.2,3

A fertilized female in the subcutaneous tissue releases microfilariae that may remain in the skin or travel to the eyes of the host.3 The host may demonstrate signs of infection within 3 to 15 months.2 Most commonly, patients report localized or generalized pruritus, and one extremity develops swelling, papules, lymphadenopathy, and alterations of skin pigment (hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation).5-8 Our patient developed a pruritic eczematous eruption that only affected her right arm with an inflamed firm nodule overlying the elbow, a suspected onchocercoma. Onchocercomas are the direct result of adult worms coiled in the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and deep fascia. These commonly are found in close proximity to bony prominences with the specific location pending the geographic area of infection.8 For example, onchocercomas more commonly are found over bony prominences in the head and upper body region in patients who acquired the disease from Central or South America, whereas individuals infected in Africa more commonly develop onchocercomas near the femoral, coccyx, or sacral regions.2

The immune response mounted by the infected host is responsible for the ocular signs and symptoms.2 Specifically, the inflammatory reaction may impact the patient’s cornea, anterior uveal tract, chorioretinal zone, or optic nerve. In fact, onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is the leading cause of blindness in the world.2 The host immune response also is responsible for the dermatologic manifestations of this disease. In addition to the dermatologic manifestations already mentioned, others include epidermal atrophy, ulcerations, femoral or inguinal lymphadenitis, lymphedema, and/or general wasting in more severe long-standing infections. Additionally, patients may experience systemic signs resulting from an underlying O volvulus infection.8 Our patient demonstrated a subjectively remarkable systemic response manifested by shortness of breath, dyspnea, cough, and palpitations, likely the result of her existing filarial infection.

Diagnosis of onchocerciasis is made by identification of microfilariae or adult worms in skin snips or punch biopsies. Histopathologic analysis of onchocerciasis has been described as several adult worms in the subcutaneous tissue surrounded by a granulomatous, fibrotic, calcified, or sometimes ossified inflammatory reaction.8 Microfilariae may migrate to the upper dermis and typically are surrounded by lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils with an absence of neutrophils,5,8 which directly causes the overlying epidermis to undergo reactive changes. Measurement of filarial nematodes often helps differentiate species. For example, O volvulus typically measures 230 to 500 mm in length for females and 16 to 42 mm in length for males.8 The thickness of cuticles typically measures 4 to 8 µm for females and 3 to 5 µm for males. Microfilariae of O volvulus also have been identified in patient’s sputum, urine, blood, and spinal fluid.8 An alternative diagnostic method described by Stingl et al9 is a diethylcarbamazine (DEC) patch test that was 92% accurate in onchocerciasis cases diagnosed by skin snip analysis.9 Therefore, this test may be a practical alternative when skin specimens are inconclusive.

Management of onchocerciasis should include excision of subcutaneous nodules to remove adult worms. In the past, DEC with suramin was prescribed and kills both microfilariae and adult worms.8 However, DEC may induce pruritus, chorioretinal damage, and optic neuritis and suramin is nephrotoxic.2 Therefore, oral ivermectin (0.15–0.20 mg/kg one-time dose, may be repeated in 3–12 months) is supported to be a less harmful option. Patients treated with ivermectin have a decreased risk for transmitting infection to the blackfly vector for up to 6 months after treatment, and it is a more effective microfilaricidal agent than DEC.2,3 Oral doxycycline (100 mg/d for 6 weeks) commonly is added as adjuvant therapy because it kills Wolbachia species, a bacterium that is needed for O volvulus reproduction.3

Although rare in the United States, cutaneous filariasis has become a prevalent public health concern, especially in tropical countries. Individuals with chronic cutaneous filarial infections are at increased risk for debilitating complications that negatively affect their quality of life and productivity. Although the World Health Organization has attempted to eradicate cutaneous filarial infections by mass drug administration, transmission of these diseases remains a challenge. Further research on treatment and methods to prevent transmission by controlling arthropod vectors is required to avoid short-term and long-term health consequences caused by cutaneous filariasis.

Parasitic infections should always be a diagnostic consideration in individuals who present with a pruritic eruption and a history of travel to foreign countries located in Africa, Central America, and South America. Dermatologists in the United States should increase familiarity with these infections because of increased travel, economic globalization, and the impact of global climate change on the geographic distribution of vector arthropods. To control these infections, research efforts should focus on improved sanitation; drug treatment; transmission prevention; and improved education of their clinical manifestations, especially mucocutaneous signs.

- Mendoza N, Li A, Gill A, et al. Filariasis: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:475-490.

- Maso MJ, Kapila R, Schwartz RA, et al. Cutaneous onchocerciasis. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:593-596.

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- Bolivar-Meija A, Alarcon-Olave C, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Skin manifestations of arthropod-borne infection in Latin America. Curr Opin. 2014;27:288-294.

- Okulicz JF, Stibich AS, Elston DM, et al. Cutaneous onchocercoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:170-172.

- Nguyen JC, Murphy ME, Nutman TB, et al. Cutaneous onchocerciasis in an American traveler. Int Soc Dermatol. 2005;44:125-128.

- Toovey S, Moerman F, van Gompel A. Special infectious disease risks of expatriates and long-term travelers in tropical countries part II: infections other than malaria. J Travel Med. 2007;14:50-60.

- Meyers WM, Neafie RC, Connor DH. Bancroftian and malayan filariasis. In Binford CH, ed. Pathology of Tropical and Extraordinary Diseases. Vol 2. Fort Sam Houston, TX: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1976:340-355.

- Stingl P, Ross M, Gibson DW, et al. A diagnostic “patch-test” for onchocerciasis using topical diethylcarbamazine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous filariasis is a group of infectious diseases caused by more than 60 different nematode species and endemic to approximately 83 countries.1,2 These infections are transmitted to humans by vectors such as mosquitoes, blackflies, biting midges, or Tabanid flies.1 The blood meal taken by vectors allow microfilariae to enter the skin and develop into adult worms.1-3 It is postulated that filarial infections were first described in 2000

Filarial parasites have been categorized into groups based on the site of adult worm stage habitat. The cutaneous group includes Loa loa, Onchocerca volvulus, Mansonella perstans, and Dipetalonema streptocerca. The lymphatic group includes Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. Lastly, the body cavity group includes Mansonella ozzardi. Because humidity is required for survival of the infective larval stage, individuals from tropical countries in Africa, Central America, and South America most commonly are affected.1 These diseases also are related to poor housing quality and inadequate sanitation.1,3,4 Travel for business, medical missions, pleasure, or emigration has caused increased filarial infections globally. In fact, dermatologic disorders with infectious etiologies cause approximately 17% of travelers to seek medical attention.3

Dermatologic manifestations indicative of a potential cutaneous filarial infection include papules, nodules, excoriations with secondary xerosis, lichenification, skin pigment changes, and/or severe pruritus. However, individuals from filarial endemic regions may not demonstrate any clinical signs or symptoms, despite having microfilariae in their blood,1 which enables the disease to propagate and poses a major public health concern. In fact, patients with chronic filarial infections are at increased risk for developing lymphedema, elephantiasis, or blindness, which are hypothesized to be the second largest cause of permanent disability worldwide.1 Although rarely seen in US citizens, cutaneous filariasis should always be a diagnostic consideration in patients who present with a pruritic eruption and have a travel history to tropical countries. We report a case of cutaneous onchocerciasis in a US citizen who developed a pruritic eczematous eruption on the right upper arm following an arthropod assault while working in an Onchocerca endemic region approximately 1.5 years prior.

A 33-year-old woman presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic with the chief concern of a pruritic rash on the right arm (Figure 1). She revealed a history of travel to Peru, associated symptoms, prior diagnoses, and attempted treatment regimens. Over a 1.5-year period, the patient traveled for work-related reasons to Madre de Dios, Peru. During that time, the patient experienced 2 bouts of severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that she attributed to poor food and water quality. She did not immediately seek medical attention. She also developed skin manifestations that began as a pruritic and irritating pinpoint-sized red papule on the right eyelid, possibly a site of an arthropod assault. She then experienced episodic eyelash loss (Figure 2) and subsequent vision changes, including blurry vision, halos around lights, and dimming around the periphery. When the patient developed circular, pink, pruritic plaques on the right upper extremity, she sought medical attention in Lima, Peru. She was diagnosed with tinea corporis and prescribed an oral antibiotic and topical antifungal.

This treatment regimen did not result in improvement. In the following months, the patient noticed worsening of the ocular symptoms, and she developed a dry cough with occasional dyspnea. She again sought medical attention in Peru and was referred to an ophthalmologist who suspected Demodex mite or fungal infection; however, workup for those pathologies was negative. The respiratory symptoms continued to worsen, particularly at night, and she began to experience palpitations.

Upon returning to the United States, the patient was evaluated by her primary care physician who ordered the following laboratory tests: a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, vitamin D level, blood culture, lipid panel, ferritin level, and thyroid function. An electrocardiogram, throat culture, and stool culture for ova and parasites also were obtained. The electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia, and the stool culture revealed blastocystis, for which she was prescribed oral metronidazole and tinidazole. The other results were within reference range, and the throat culture showed normal oropharyngeal microbes.

A few days after the treatment for the blastocystis, the gastrointestinal tract symptoms improved, but dermatologic, ocular, pulmonary, and cardiac symptoms persisted. She also began experiencing night sweats and hot flashes. In between visits to the primary care physician, she sought medical attention at an urgent care clinic for worsening pulmonary and cardiac symptoms. At that time, results of a chest radiograph were normal.

The primary care physician referred her to infectious disease and dermatology for further evaluation within a few weeks of returning to the United States. Upon presentation to dermatology, the patient described a waxing and waning nature to the rash on the arm with associated intermittent pain. Physical examination revealed several erythematous patches on the triceps and a 1-cm subcutaneous nodule on the right elbow with overlying skin discoloration. The patient stated that she first noticed the inflamed painful nodule when she returned to the United States. Since its discovery, the nodule increased in size and became firm. The patient also described occasional limited range of motion of the right arm due to the discomfort of the rash and inflamed nodule. Interestingly, the patient’s partner who accompanied her to Peru also developed a similar pruritic rash on the chest. He was evaluated by dermatology and infectious disease; however, biopsies of his rash performed at a different practice revealed nonspecific results. Due to her partner’s inconclusive results, our patient initially refused a biopsy; however, she returned to the office after 1 week with worsening symptoms, and a 4-mm punch biopsy of the right arm was obtained in addition to rapid plasma reagin and QuantiFERON-TB Gold test.

Based on the patient’s travel history, clinical course, and physical examination, the clinical differential diagnosis included nummular dermatitis, panniculitis/nodular vasculitis, tinea corporis, secondary syphilis, pinta, tuberculosis, or cutaneous filariasis. Rapid plasma reagin and QuantiFERON-TB Gold test results were negative, and a periodic acid–Schiff stain of the biopsy was negative for fungal elements. Dermatopathology revealed intradermal filarial nematodes of 120 to 150 µm in diameter and 1-to 2-mm cuticles eliciting a predominantly superficial and deep lymphohistiocytic reaction (Figure 3). The histopathologic differential diagnosis based on the diameter of the nematode included M perstans, W bancrofti, and O volvulus. Clinical correlation was highly recommended to obtain a final diagnosis and management plan. A portion of the biopsy was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which confirmed the presence of a filarial nematode consistent with a zoonotic Brugia but also with zoonotic Onchocerca as a possible differential. Therefore, considering the history, clinical course, and histopathologic analysis, the final diagnosis of cutaneous onchocerciasis was made.

The patient was referred back to infectious disease and started on combination therapy of ivermectin (25.5 mg) plus albendazole (800 mg) taken at once followed by doxycycline (200 mg) for 6 weeks. The symptoms initially worsened, then she experienced near-complete resolution of dermatologic, pulmonary, and ocular symptoms after approximately 2 weeks of treatment. She continued to report fatigue and palpitations, for she continued to see a cardiologist. We highly encouraged her to continue following up with infectious disease to ensure complete eradication of the infection.

Onchocerciasis is common in individuals who live or work in equatorial Africa, Central America, and South America. The disease process has dermatologic, ocular, and other systemic manifestations if the infection continues long-term without treatment.2,5 Although rare, this infection has been observed in US citizens who have traveled to filarial endemic regions for a period of time ranging from 2 weeks to 39 years.2,6,7

Blackflies (genus Simulium), the intermediate host of O volvulus, breed in areas close to freely flowing water. The blackfly bites a human host, and within 7 days the microfilariae undergo 2 molts to reach the infective stage. The larvae remain in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue for 2 additional molts until they develop into adult worms. Then, adult worms may become encapsulated, eliciting and forming subcutaneous nodules, also known as onchocercomas.2,3

A fertilized female in the subcutaneous tissue releases microfilariae that may remain in the skin or travel to the eyes of the host.3 The host may demonstrate signs of infection within 3 to 15 months.2 Most commonly, patients report localized or generalized pruritus, and one extremity develops swelling, papules, lymphadenopathy, and alterations of skin pigment (hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation).5-8 Our patient developed a pruritic eczematous eruption that only affected her right arm with an inflamed firm nodule overlying the elbow, a suspected onchocercoma. Onchocercomas are the direct result of adult worms coiled in the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and deep fascia. These commonly are found in close proximity to bony prominences with the specific location pending the geographic area of infection.8 For example, onchocercomas more commonly are found over bony prominences in the head and upper body region in patients who acquired the disease from Central or South America, whereas individuals infected in Africa more commonly develop onchocercomas near the femoral, coccyx, or sacral regions.2

The immune response mounted by the infected host is responsible for the ocular signs and symptoms.2 Specifically, the inflammatory reaction may impact the patient’s cornea, anterior uveal tract, chorioretinal zone, or optic nerve. In fact, onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is the leading cause of blindness in the world.2 The host immune response also is responsible for the dermatologic manifestations of this disease. In addition to the dermatologic manifestations already mentioned, others include epidermal atrophy, ulcerations, femoral or inguinal lymphadenitis, lymphedema, and/or general wasting in more severe long-standing infections. Additionally, patients may experience systemic signs resulting from an underlying O volvulus infection.8 Our patient demonstrated a subjectively remarkable systemic response manifested by shortness of breath, dyspnea, cough, and palpitations, likely the result of her existing filarial infection.

Diagnosis of onchocerciasis is made by identification of microfilariae or adult worms in skin snips or punch biopsies. Histopathologic analysis of onchocerciasis has been described as several adult worms in the subcutaneous tissue surrounded by a granulomatous, fibrotic, calcified, or sometimes ossified inflammatory reaction.8 Microfilariae may migrate to the upper dermis and typically are surrounded by lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils with an absence of neutrophils,5,8 which directly causes the overlying epidermis to undergo reactive changes. Measurement of filarial nematodes often helps differentiate species. For example, O volvulus typically measures 230 to 500 mm in length for females and 16 to 42 mm in length for males.8 The thickness of cuticles typically measures 4 to 8 µm for females and 3 to 5 µm for males. Microfilariae of O volvulus also have been identified in patient’s sputum, urine, blood, and spinal fluid.8 An alternative diagnostic method described by Stingl et al9 is a diethylcarbamazine (DEC) patch test that was 92% accurate in onchocerciasis cases diagnosed by skin snip analysis.9 Therefore, this test may be a practical alternative when skin specimens are inconclusive.

Management of onchocerciasis should include excision of subcutaneous nodules to remove adult worms. In the past, DEC with suramin was prescribed and kills both microfilariae and adult worms.8 However, DEC may induce pruritus, chorioretinal damage, and optic neuritis and suramin is nephrotoxic.2 Therefore, oral ivermectin (0.15–0.20 mg/kg one-time dose, may be repeated in 3–12 months) is supported to be a less harmful option. Patients treated with ivermectin have a decreased risk for transmitting infection to the blackfly vector for up to 6 months after treatment, and it is a more effective microfilaricidal agent than DEC.2,3 Oral doxycycline (100 mg/d for 6 weeks) commonly is added as adjuvant therapy because it kills Wolbachia species, a bacterium that is needed for O volvulus reproduction.3

Although rare in the United States, cutaneous filariasis has become a prevalent public health concern, especially in tropical countries. Individuals with chronic cutaneous filarial infections are at increased risk for debilitating complications that negatively affect their quality of life and productivity. Although the World Health Organization has attempted to eradicate cutaneous filarial infections by mass drug administration, transmission of these diseases remains a challenge. Further research on treatment and methods to prevent transmission by controlling arthropod vectors is required to avoid short-term and long-term health consequences caused by cutaneous filariasis.

Parasitic infections should always be a diagnostic consideration in individuals who present with a pruritic eruption and a history of travel to foreign countries located in Africa, Central America, and South America. Dermatologists in the United States should increase familiarity with these infections because of increased travel, economic globalization, and the impact of global climate change on the geographic distribution of vector arthropods. To control these infections, research efforts should focus on improved sanitation; drug treatment; transmission prevention; and improved education of their clinical manifestations, especially mucocutaneous signs.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous filariasis is a group of infectious diseases caused by more than 60 different nematode species and endemic to approximately 83 countries.1,2 These infections are transmitted to humans by vectors such as mosquitoes, blackflies, biting midges, or Tabanid flies.1 The blood meal taken by vectors allow microfilariae to enter the skin and develop into adult worms.1-3 It is postulated that filarial infections were first described in 2000

Filarial parasites have been categorized into groups based on the site of adult worm stage habitat. The cutaneous group includes Loa loa, Onchocerca volvulus, Mansonella perstans, and Dipetalonema streptocerca. The lymphatic group includes Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. Lastly, the body cavity group includes Mansonella ozzardi. Because humidity is required for survival of the infective larval stage, individuals from tropical countries in Africa, Central America, and South America most commonly are affected.1 These diseases also are related to poor housing quality and inadequate sanitation.1,3,4 Travel for business, medical missions, pleasure, or emigration has caused increased filarial infections globally. In fact, dermatologic disorders with infectious etiologies cause approximately 17% of travelers to seek medical attention.3

Dermatologic manifestations indicative of a potential cutaneous filarial infection include papules, nodules, excoriations with secondary xerosis, lichenification, skin pigment changes, and/or severe pruritus. However, individuals from filarial endemic regions may not demonstrate any clinical signs or symptoms, despite having microfilariae in their blood,1 which enables the disease to propagate and poses a major public health concern. In fact, patients with chronic filarial infections are at increased risk for developing lymphedema, elephantiasis, or blindness, which are hypothesized to be the second largest cause of permanent disability worldwide.1 Although rarely seen in US citizens, cutaneous filariasis should always be a diagnostic consideration in patients who present with a pruritic eruption and have a travel history to tropical countries. We report a case of cutaneous onchocerciasis in a US citizen who developed a pruritic eczematous eruption on the right upper arm following an arthropod assault while working in an Onchocerca endemic region approximately 1.5 years prior.

A 33-year-old woman presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic with the chief concern of a pruritic rash on the right arm (Figure 1). She revealed a history of travel to Peru, associated symptoms, prior diagnoses, and attempted treatment regimens. Over a 1.5-year period, the patient traveled for work-related reasons to Madre de Dios, Peru. During that time, the patient experienced 2 bouts of severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that she attributed to poor food and water quality. She did not immediately seek medical attention. She also developed skin manifestations that began as a pruritic and irritating pinpoint-sized red papule on the right eyelid, possibly a site of an arthropod assault. She then experienced episodic eyelash loss (Figure 2) and subsequent vision changes, including blurry vision, halos around lights, and dimming around the periphery. When the patient developed circular, pink, pruritic plaques on the right upper extremity, she sought medical attention in Lima, Peru. She was diagnosed with tinea corporis and prescribed an oral antibiotic and topical antifungal.

This treatment regimen did not result in improvement. In the following months, the patient noticed worsening of the ocular symptoms, and she developed a dry cough with occasional dyspnea. She again sought medical attention in Peru and was referred to an ophthalmologist who suspected Demodex mite or fungal infection; however, workup for those pathologies was negative. The respiratory symptoms continued to worsen, particularly at night, and she began to experience palpitations.

Upon returning to the United States, the patient was evaluated by her primary care physician who ordered the following laboratory tests: a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, vitamin D level, blood culture, lipid panel, ferritin level, and thyroid function. An electrocardiogram, throat culture, and stool culture for ova and parasites also were obtained. The electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia, and the stool culture revealed blastocystis, for which she was prescribed oral metronidazole and tinidazole. The other results were within reference range, and the throat culture showed normal oropharyngeal microbes.

A few days after the treatment for the blastocystis, the gastrointestinal tract symptoms improved, but dermatologic, ocular, pulmonary, and cardiac symptoms persisted. She also began experiencing night sweats and hot flashes. In between visits to the primary care physician, she sought medical attention at an urgent care clinic for worsening pulmonary and cardiac symptoms. At that time, results of a chest radiograph were normal.

The primary care physician referred her to infectious disease and dermatology for further evaluation within a few weeks of returning to the United States. Upon presentation to dermatology, the patient described a waxing and waning nature to the rash on the arm with associated intermittent pain. Physical examination revealed several erythematous patches on the triceps and a 1-cm subcutaneous nodule on the right elbow with overlying skin discoloration. The patient stated that she first noticed the inflamed painful nodule when she returned to the United States. Since its discovery, the nodule increased in size and became firm. The patient also described occasional limited range of motion of the right arm due to the discomfort of the rash and inflamed nodule. Interestingly, the patient’s partner who accompanied her to Peru also developed a similar pruritic rash on the chest. He was evaluated by dermatology and infectious disease; however, biopsies of his rash performed at a different practice revealed nonspecific results. Due to her partner’s inconclusive results, our patient initially refused a biopsy; however, she returned to the office after 1 week with worsening symptoms, and a 4-mm punch biopsy of the right arm was obtained in addition to rapid plasma reagin and QuantiFERON-TB Gold test.

Based on the patient’s travel history, clinical course, and physical examination, the clinical differential diagnosis included nummular dermatitis, panniculitis/nodular vasculitis, tinea corporis, secondary syphilis, pinta, tuberculosis, or cutaneous filariasis. Rapid plasma reagin and QuantiFERON-TB Gold test results were negative, and a periodic acid–Schiff stain of the biopsy was negative for fungal elements. Dermatopathology revealed intradermal filarial nematodes of 120 to 150 µm in diameter and 1-to 2-mm cuticles eliciting a predominantly superficial and deep lymphohistiocytic reaction (Figure 3). The histopathologic differential diagnosis based on the diameter of the nematode included M perstans, W bancrofti, and O volvulus. Clinical correlation was highly recommended to obtain a final diagnosis and management plan. A portion of the biopsy was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which confirmed the presence of a filarial nematode consistent with a zoonotic Brugia but also with zoonotic Onchocerca as a possible differential. Therefore, considering the history, clinical course, and histopathologic analysis, the final diagnosis of cutaneous onchocerciasis was made.

The patient was referred back to infectious disease and started on combination therapy of ivermectin (25.5 mg) plus albendazole (800 mg) taken at once followed by doxycycline (200 mg) for 6 weeks. The symptoms initially worsened, then she experienced near-complete resolution of dermatologic, pulmonary, and ocular symptoms after approximately 2 weeks of treatment. She continued to report fatigue and palpitations, for she continued to see a cardiologist. We highly encouraged her to continue following up with infectious disease to ensure complete eradication of the infection.

Onchocerciasis is common in individuals who live or work in equatorial Africa, Central America, and South America. The disease process has dermatologic, ocular, and other systemic manifestations if the infection continues long-term without treatment.2,5 Although rare, this infection has been observed in US citizens who have traveled to filarial endemic regions for a period of time ranging from 2 weeks to 39 years.2,6,7

Blackflies (genus Simulium), the intermediate host of O volvulus, breed in areas close to freely flowing water. The blackfly bites a human host, and within 7 days the microfilariae undergo 2 molts to reach the infective stage. The larvae remain in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue for 2 additional molts until they develop into adult worms. Then, adult worms may become encapsulated, eliciting and forming subcutaneous nodules, also known as onchocercomas.2,3

A fertilized female in the subcutaneous tissue releases microfilariae that may remain in the skin or travel to the eyes of the host.3 The host may demonstrate signs of infection within 3 to 15 months.2 Most commonly, patients report localized or generalized pruritus, and one extremity develops swelling, papules, lymphadenopathy, and alterations of skin pigment (hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation).5-8 Our patient developed a pruritic eczematous eruption that only affected her right arm with an inflamed firm nodule overlying the elbow, a suspected onchocercoma. Onchocercomas are the direct result of adult worms coiled in the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and deep fascia. These commonly are found in close proximity to bony prominences with the specific location pending the geographic area of infection.8 For example, onchocercomas more commonly are found over bony prominences in the head and upper body region in patients who acquired the disease from Central or South America, whereas individuals infected in Africa more commonly develop onchocercomas near the femoral, coccyx, or sacral regions.2

The immune response mounted by the infected host is responsible for the ocular signs and symptoms.2 Specifically, the inflammatory reaction may impact the patient’s cornea, anterior uveal tract, chorioretinal zone, or optic nerve. In fact, onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is the leading cause of blindness in the world.2 The host immune response also is responsible for the dermatologic manifestations of this disease. In addition to the dermatologic manifestations already mentioned, others include epidermal atrophy, ulcerations, femoral or inguinal lymphadenitis, lymphedema, and/or general wasting in more severe long-standing infections. Additionally, patients may experience systemic signs resulting from an underlying O volvulus infection.8 Our patient demonstrated a subjectively remarkable systemic response manifested by shortness of breath, dyspnea, cough, and palpitations, likely the result of her existing filarial infection.

Diagnosis of onchocerciasis is made by identification of microfilariae or adult worms in skin snips or punch biopsies. Histopathologic analysis of onchocerciasis has been described as several adult worms in the subcutaneous tissue surrounded by a granulomatous, fibrotic, calcified, or sometimes ossified inflammatory reaction.8 Microfilariae may migrate to the upper dermis and typically are surrounded by lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils with an absence of neutrophils,5,8 which directly causes the overlying epidermis to undergo reactive changes. Measurement of filarial nematodes often helps differentiate species. For example, O volvulus typically measures 230 to 500 mm in length for females and 16 to 42 mm in length for males.8 The thickness of cuticles typically measures 4 to 8 µm for females and 3 to 5 µm for males. Microfilariae of O volvulus also have been identified in patient’s sputum, urine, blood, and spinal fluid.8 An alternative diagnostic method described by Stingl et al9 is a diethylcarbamazine (DEC) patch test that was 92% accurate in onchocerciasis cases diagnosed by skin snip analysis.9 Therefore, this test may be a practical alternative when skin specimens are inconclusive.

Management of onchocerciasis should include excision of subcutaneous nodules to remove adult worms. In the past, DEC with suramin was prescribed and kills both microfilariae and adult worms.8 However, DEC may induce pruritus, chorioretinal damage, and optic neuritis and suramin is nephrotoxic.2 Therefore, oral ivermectin (0.15–0.20 mg/kg one-time dose, may be repeated in 3–12 months) is supported to be a less harmful option. Patients treated with ivermectin have a decreased risk for transmitting infection to the blackfly vector for up to 6 months after treatment, and it is a more effective microfilaricidal agent than DEC.2,3 Oral doxycycline (100 mg/d for 6 weeks) commonly is added as adjuvant therapy because it kills Wolbachia species, a bacterium that is needed for O volvulus reproduction.3

Although rare in the United States, cutaneous filariasis has become a prevalent public health concern, especially in tropical countries. Individuals with chronic cutaneous filarial infections are at increased risk for debilitating complications that negatively affect their quality of life and productivity. Although the World Health Organization has attempted to eradicate cutaneous filarial infections by mass drug administration, transmission of these diseases remains a challenge. Further research on treatment and methods to prevent transmission by controlling arthropod vectors is required to avoid short-term and long-term health consequences caused by cutaneous filariasis.

Parasitic infections should always be a diagnostic consideration in individuals who present with a pruritic eruption and a history of travel to foreign countries located in Africa, Central America, and South America. Dermatologists in the United States should increase familiarity with these infections because of increased travel, economic globalization, and the impact of global climate change on the geographic distribution of vector arthropods. To control these infections, research efforts should focus on improved sanitation; drug treatment; transmission prevention; and improved education of their clinical manifestations, especially mucocutaneous signs.

- Mendoza N, Li A, Gill A, et al. Filariasis: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:475-490.

- Maso MJ, Kapila R, Schwartz RA, et al. Cutaneous onchocerciasis. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:593-596.

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- Bolivar-Meija A, Alarcon-Olave C, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Skin manifestations of arthropod-borne infection in Latin America. Curr Opin. 2014;27:288-294.

- Okulicz JF, Stibich AS, Elston DM, et al. Cutaneous onchocercoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:170-172.

- Nguyen JC, Murphy ME, Nutman TB, et al. Cutaneous onchocerciasis in an American traveler. Int Soc Dermatol. 2005;44:125-128.

- Toovey S, Moerman F, van Gompel A. Special infectious disease risks of expatriates and long-term travelers in tropical countries part II: infections other than malaria. J Travel Med. 2007;14:50-60.

- Meyers WM, Neafie RC, Connor DH. Bancroftian and malayan filariasis. In Binford CH, ed. Pathology of Tropical and Extraordinary Diseases. Vol 2. Fort Sam Houston, TX: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1976:340-355.

- Stingl P, Ross M, Gibson DW, et al. A diagnostic “patch-test” for onchocerciasis using topical diethylcarbamazine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.

- Mendoza N, Li A, Gill A, et al. Filariasis: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:475-490.

- Maso MJ, Kapila R, Schwartz RA, et al. Cutaneous onchocerciasis. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:593-596.

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- Bolivar-Meija A, Alarcon-Olave C, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Skin manifestations of arthropod-borne infection in Latin America. Curr Opin. 2014;27:288-294.

- Okulicz JF, Stibich AS, Elston DM, et al. Cutaneous onchocercoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:170-172.

- Nguyen JC, Murphy ME, Nutman TB, et al. Cutaneous onchocerciasis in an American traveler. Int Soc Dermatol. 2005;44:125-128.

- Toovey S, Moerman F, van Gompel A. Special infectious disease risks of expatriates and long-term travelers in tropical countries part II: infections other than malaria. J Travel Med. 2007;14:50-60.

- Meyers WM, Neafie RC, Connor DH. Bancroftian and malayan filariasis. In Binford CH, ed. Pathology of Tropical and Extraordinary Diseases. Vol 2. Fort Sam Houston, TX: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1976:340-355.

- Stingl P, Ross M, Gibson DW, et al. A diagnostic “patch-test” for onchocerciasis using topical diethylcarbamazine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.

Practice Points

- Parasitic infections should always be a diagnostic consideration in individuals who present with a pruritic eruption and a history of travel.

- To control parasitic infections, research efforts should focus on improved sanitation, drug treatment, transmission prevention, and improved education of clinical manifestations to increase early detection.

The Dermatologist Nose Best: Correlation of Nose-Picking Habits and <i>Staphylococcus aureus</i>–Related Dermatologic Disease

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.

Staphylococcus aureus colonizes the anterior nares of 20% to 80% of humans; nasal colonization can begin during the first days of life.2 The anterior nares are noted as the main reservoir of chronic carriage of S aureus, but carriage can occur at various body sites, including the rectum, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and axilla, as well as other cutaneous sites. Hands are noted as the main vector of S aureus transmission from source to nose; a positive correlation between nose-picking habits and nasal carriage of S aureus has been noted.2

The percentage of S aureus–colonized humans who harbor MRSA is unknown, but it is a topic of concern with the rise of MRSA-related infection. Multisite MRSA carriage increases the risk for nasal MRSA colonization, and nasal MRSA has been noted to be more difficult to decolonize than nonresistant strains. Health care workers carrying S aureus can trigger a potential hospital outbreak of MRSA. Studies have shown that bacterial transmission is increased 40-fold when the nasal host is co-infected by rhinovirus.2 Health care workers can be a source of MRSA during outbreaks, but they have not been shown to be more likely to carry MRSA than the general population.2 Understanding which patients might be at risk for S aureus–associated disease in dermatology can lead clinicians to consider decolonization strategies.

Nasal colonization has been noted more frequently in patients with predisposing risk factors, including human immunodeficiency virus infection, obesity, diabetes mellitus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HLA-DR3 phenotype, skin and soft-tissue infections, atopic dermatitis, impetigo, and recurrent furunculosis.2Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently noted pathogen in diabetic foot infection. A study found that 36% of sampled diabetic foot-infection patients also had S aureus isolated from both nares and the foot wound, with 65% of isolated strains being identical.2 Although there are clear data on decolonization of patients prior to heart and orthopedic surgery, more data are needed to determine the benefit of screening and treating nasal carriers in populations with diabetic foot ulcers.

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization also has been shown in approximately 60% of patients with recurrent furunculosis and impetigo.2 Although it is clear that there is a correlation between S aureus–related skin infection and nasal colonization, it is unclear what role nose-picking might have in perpetuating these complications.

There are multiple approaches to S aureus decolonization, including intranasal mupirocin, chlorhexidine body wipes, bleach baths, and even oral antibiotics (eg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin). The Infectious Diseases Society of America has published guidelines for treating recurrent MRSA infection, including 5 to 10 days of intranasal mupirocin plus either body decolonization with a daily chlorhexidine wash for 5 to 14 days or a 15-minute dilute bleach bath twice weekly for 3 months.3,4

There are ample meta-analyses and systematic reviews regarding S aureus decolonization and management in patients undergoing dialysis or surgery but limited data when it comes to this topic in dermatology. Those limited studies do show a benefit to decolonization in several diseases, including atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, recurrent skin and soft-tissue infections, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and surgical infection following Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Typically, it also is necessary to treat those who might come in contact with the patient or caregiver; in theory, treating contacts helps reduce the chance that the patient will become recolonized shortly afterward, but the data are limited regarding long-term colonization status following treatment. Contact surfaces, especially cell phones, are noted to be a contributing factor to nares colonization; therefore, it also may be necessary to educate patients on surface-cleaning techniques.5 Because there are multiple sources of S aureus that patients can come in contact with after decolonization attempts, a nose-picking habit might play a vital role in recolonization.

Due to rising bacterial resistance to mupirocin and chlorhexidine decolonization strategies, there is a growing need for more effective, long-term decolonization strategies.4 These strategies must address patients’ environmental exposure and nasal-touching habits. Overcoming the habit of nose-picking might aid S aureus decolonization strategies and thus aid in preventing future antimicrobial resistance.

But are at-risk patients receiving sufficient screening and education on the dangers of a nose-picking habit? Effective strategies to assess these practices and recommend the discontinuation of the habit could have positive effects in maintaining long-term decolonization. Potential euphemistic ways to approach this somewhat taboo topic include questions that elicit information on whether the patient ever touches the inside of his/her nose, washes his/her hands before and after touching the inside of the nose, knows about transfer of bacteria from hand to nose, or understands what decolonization is doing for them. The patient might be inclined to deny such activity, but education on nasal hygiene should be provided regardless, especially in pediatric patients.

Staphylococcus aureus might be a normal human nasal inhabitant, but it can cause a range of problems for dermatologic disease. Although pharmacotherapeutic decolonization strategies can have a positive effect on dermatologic disease, growing antibiotic resistance calls for health care providers to assess patients’ nose picking-habits and educate them on effective ways to prevent finger-to-nose practices.

- Andrade C, Srihari BS. A preliminary survey of rhinotillexomania in an adolescent sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:426-431.

- Sakr A, Brégeon F, Mège J-L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2419.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

- Kuraitis D, Williams L. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in healthcare: a dermatology perspective. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:2382050.

- Creech CB, Al-Zubeidi DN, Fritz SA. Prevention of recurrent staphylococcal kin infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:429-464.

Primitive human habits have withstood the test of time but can pose health risks. Exploring a nasal cavity with a finger might have first occurred shortly after whichever species first developed a nasal opening and a digit able to reach it. Humans have been keen on continuing the long-standing yet taboo habit of nose-picking (rhinotillexis).

Even though nose-picking is stigmatized, anonymous surveys show that almost all adolescents and adults do it.1 People are typically unaware of the risks of regular rhinotillexis. Studies exploring the intranasal human microbiome have elicited asymptomatic yet potential disease-causing microbes, including the notorious bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. As many as 30% of humans are asymptomatically permanently colonized with S aureus in their anterior nares.2 These natural reservoirs can be the source of opportunistic infection that increases morbidity, mortality, and overall health care costs.

With the rise of antimicrobial resistance, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), a more direct approach might be necessary to curb nasally sourced cutaneous infection. Since dermatology patients deal with a wide array of skin barrier defects that put them at risk for S aureus–related infection, a medical provider’s understanding about the role of nasal colonization and transmission is important. Addressing the awkward question of “Do you pick your nose?” and providing education on the topic might be uncomfortable, but it might be necessary for dermatology patients at risk for S aureus–related cutaneous disease.