User login

COVID-19 vaccine won’t be a slam dunk

A successful vaccine for prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection will probably need to incorporate T-cell epitopes to induce a long-term memory T-cell immune response to the virus, Mehrdad Matloubian, MD, PhD, predicted at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

Vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies may not be sufficient to reliably provide sustained protection against infection. In mouse studies, T-cell immunity has protected against reinfection with the novel coronaviruses. And in some but not all studies of patients infected with the SARS virus, which shares 80% genetic overlap with the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, neutralizing antibodies have waned over time.

“In one study, 20 of 26 patients with SARS had lost their antibody response by 6 years post infection. And they had no B-cell immunity against the SARS antigens. The good news is they did have T-cell memory against SARS virus, and people with more severe disease tended to have more T-cell memory against SARS. All of this has really important implications for vaccine development,” observed Dr. Matloubian, a rheumatologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Matloubian is among those who are convinced that the ongoing massive global accelerated effort to develop a safe and effective vaccine affords the best opportunity to gain the upper hand in the COVID-19 pandemic. A large array of vaccines are in development.

A key safety concern to watch for in the coming months is whether a vaccine candidate is able to sidestep the issue of antibody-dependent enhancement, whereby prior infection with a non-SARS coronavirus, such as those that cause the common cold, might result in creation of rogue subneutralizing coronavirus antibodies in response to vaccination. There is concern that these nonneutralizing antibodies could facilitate entry of the virus into monocytes and other cells lacking the ACE2 receptor, its usual portal of entry. This in turn could trigger expanded viral replication, a hyperinflammatory response, and viral spread to sites beyond the lung, such as the heart or kidneys.

Little optimism about antivirals’ impact

Dr. Matloubian predicted that antiviral medications, including the much-ballyhooed remdesivir, are unlikely to be a game changer in the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s because most patients who become symptomatic don’t do so until at least 2 days post infection. By that point, their viral load has already peaked and is waning and the B- and T-cell immune responses are starting to gear up.

“Timing seems to be everything when it comes to treatment with antivirals,” he observed. “The virus titer is usually declining by the time people present with severe COVID-19, suggesting that at this time antiviral therapy might be of little use to change the course of the disease, especially if it’s mainly immune-mediated by then. Even with influenza virus, there’s a really short window where Tamiflu [oseltamivir] is effective. It’s going to be the same case for antivirals used for treatment of COVID-19.”

He noted that in a placebo-controlled, randomized trial of remdesivir in 236 Chinese patients with severe COVID-19, intravenous remdesivir wasn’t associated with a significantly shorter time to clinical improvement, although there was a trend in that direction in the subgroup with symptom duration of 10 days or less at initiation of treatment.

A National Institutes of Health press release announcing that remdesivir had a positive impact on duration of hospitalization in a separate randomized trial drew enormous attention from a public desperate for good news. However, the full study has yet to be published, and it’s unclear when during the disease course the antiviral agent was started.

“We need a blockbuster antiviral that’s oral, highly effective, and doesn’t have any side effects to be used in prophylaxis of health care workers and for people who are exposed by family members being infected. And so far there is no such thing, even on the horizon,” according to the rheumatologist.

Fellow panelist Jinoos Yazdany, MD, concurred.

“As we talk to experts around the country, it seems like there isn’t very much optimism about such a blockbuster drug. Most people are actually putting their hope in a vaccine,” said Dr. Yazdany, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and chief of rheumatology at San Francisco General Hospital.

Another research priority is identification of biomarkers in blood or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid to identify early on the subgroup of infected patients who are likely to crash and develop severe disease. That would permit a targeted approach to inhibition of the inflammatory pathways contributing to development of acute respiratory distress syndrome before this full-blown cytokine storm-like syndrome can occur. There is great interest in trying to achieve this by repurposing many biologic agents widely used by rheumatologists, including the interleukin-1 blocker anakinra (Kineret) and the IL-6 blocker tocilizumab (Actemra).

Dr. Matloubian reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

A successful vaccine for prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection will probably need to incorporate T-cell epitopes to induce a long-term memory T-cell immune response to the virus, Mehrdad Matloubian, MD, PhD, predicted at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

Vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies may not be sufficient to reliably provide sustained protection against infection. In mouse studies, T-cell immunity has protected against reinfection with the novel coronaviruses. And in some but not all studies of patients infected with the SARS virus, which shares 80% genetic overlap with the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, neutralizing antibodies have waned over time.

“In one study, 20 of 26 patients with SARS had lost their antibody response by 6 years post infection. And they had no B-cell immunity against the SARS antigens. The good news is they did have T-cell memory against SARS virus, and people with more severe disease tended to have more T-cell memory against SARS. All of this has really important implications for vaccine development,” observed Dr. Matloubian, a rheumatologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Matloubian is among those who are convinced that the ongoing massive global accelerated effort to develop a safe and effective vaccine affords the best opportunity to gain the upper hand in the COVID-19 pandemic. A large array of vaccines are in development.

A key safety concern to watch for in the coming months is whether a vaccine candidate is able to sidestep the issue of antibody-dependent enhancement, whereby prior infection with a non-SARS coronavirus, such as those that cause the common cold, might result in creation of rogue subneutralizing coronavirus antibodies in response to vaccination. There is concern that these nonneutralizing antibodies could facilitate entry of the virus into monocytes and other cells lacking the ACE2 receptor, its usual portal of entry. This in turn could trigger expanded viral replication, a hyperinflammatory response, and viral spread to sites beyond the lung, such as the heart or kidneys.

Little optimism about antivirals’ impact

Dr. Matloubian predicted that antiviral medications, including the much-ballyhooed remdesivir, are unlikely to be a game changer in the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s because most patients who become symptomatic don’t do so until at least 2 days post infection. By that point, their viral load has already peaked and is waning and the B- and T-cell immune responses are starting to gear up.

“Timing seems to be everything when it comes to treatment with antivirals,” he observed. “The virus titer is usually declining by the time people present with severe COVID-19, suggesting that at this time antiviral therapy might be of little use to change the course of the disease, especially if it’s mainly immune-mediated by then. Even with influenza virus, there’s a really short window where Tamiflu [oseltamivir] is effective. It’s going to be the same case for antivirals used for treatment of COVID-19.”

He noted that in a placebo-controlled, randomized trial of remdesivir in 236 Chinese patients with severe COVID-19, intravenous remdesivir wasn’t associated with a significantly shorter time to clinical improvement, although there was a trend in that direction in the subgroup with symptom duration of 10 days or less at initiation of treatment.

A National Institutes of Health press release announcing that remdesivir had a positive impact on duration of hospitalization in a separate randomized trial drew enormous attention from a public desperate for good news. However, the full study has yet to be published, and it’s unclear when during the disease course the antiviral agent was started.

“We need a blockbuster antiviral that’s oral, highly effective, and doesn’t have any side effects to be used in prophylaxis of health care workers and for people who are exposed by family members being infected. And so far there is no such thing, even on the horizon,” according to the rheumatologist.

Fellow panelist Jinoos Yazdany, MD, concurred.

“As we talk to experts around the country, it seems like there isn’t very much optimism about such a blockbuster drug. Most people are actually putting their hope in a vaccine,” said Dr. Yazdany, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and chief of rheumatology at San Francisco General Hospital.

Another research priority is identification of biomarkers in blood or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid to identify early on the subgroup of infected patients who are likely to crash and develop severe disease. That would permit a targeted approach to inhibition of the inflammatory pathways contributing to development of acute respiratory distress syndrome before this full-blown cytokine storm-like syndrome can occur. There is great interest in trying to achieve this by repurposing many biologic agents widely used by rheumatologists, including the interleukin-1 blocker anakinra (Kineret) and the IL-6 blocker tocilizumab (Actemra).

Dr. Matloubian reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

A successful vaccine for prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection will probably need to incorporate T-cell epitopes to induce a long-term memory T-cell immune response to the virus, Mehrdad Matloubian, MD, PhD, predicted at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

Vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies may not be sufficient to reliably provide sustained protection against infection. In mouse studies, T-cell immunity has protected against reinfection with the novel coronaviruses. And in some but not all studies of patients infected with the SARS virus, which shares 80% genetic overlap with the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, neutralizing antibodies have waned over time.

“In one study, 20 of 26 patients with SARS had lost their antibody response by 6 years post infection. And they had no B-cell immunity against the SARS antigens. The good news is they did have T-cell memory against SARS virus, and people with more severe disease tended to have more T-cell memory against SARS. All of this has really important implications for vaccine development,” observed Dr. Matloubian, a rheumatologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Matloubian is among those who are convinced that the ongoing massive global accelerated effort to develop a safe and effective vaccine affords the best opportunity to gain the upper hand in the COVID-19 pandemic. A large array of vaccines are in development.

A key safety concern to watch for in the coming months is whether a vaccine candidate is able to sidestep the issue of antibody-dependent enhancement, whereby prior infection with a non-SARS coronavirus, such as those that cause the common cold, might result in creation of rogue subneutralizing coronavirus antibodies in response to vaccination. There is concern that these nonneutralizing antibodies could facilitate entry of the virus into monocytes and other cells lacking the ACE2 receptor, its usual portal of entry. This in turn could trigger expanded viral replication, a hyperinflammatory response, and viral spread to sites beyond the lung, such as the heart or kidneys.

Little optimism about antivirals’ impact

Dr. Matloubian predicted that antiviral medications, including the much-ballyhooed remdesivir, are unlikely to be a game changer in the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s because most patients who become symptomatic don’t do so until at least 2 days post infection. By that point, their viral load has already peaked and is waning and the B- and T-cell immune responses are starting to gear up.

“Timing seems to be everything when it comes to treatment with antivirals,” he observed. “The virus titer is usually declining by the time people present with severe COVID-19, suggesting that at this time antiviral therapy might be of little use to change the course of the disease, especially if it’s mainly immune-mediated by then. Even with influenza virus, there’s a really short window where Tamiflu [oseltamivir] is effective. It’s going to be the same case for antivirals used for treatment of COVID-19.”

He noted that in a placebo-controlled, randomized trial of remdesivir in 236 Chinese patients with severe COVID-19, intravenous remdesivir wasn’t associated with a significantly shorter time to clinical improvement, although there was a trend in that direction in the subgroup with symptom duration of 10 days or less at initiation of treatment.

A National Institutes of Health press release announcing that remdesivir had a positive impact on duration of hospitalization in a separate randomized trial drew enormous attention from a public desperate for good news. However, the full study has yet to be published, and it’s unclear when during the disease course the antiviral agent was started.

“We need a blockbuster antiviral that’s oral, highly effective, and doesn’t have any side effects to be used in prophylaxis of health care workers and for people who are exposed by family members being infected. And so far there is no such thing, even on the horizon,” according to the rheumatologist.

Fellow panelist Jinoos Yazdany, MD, concurred.

“As we talk to experts around the country, it seems like there isn’t very much optimism about such a blockbuster drug. Most people are actually putting their hope in a vaccine,” said Dr. Yazdany, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and chief of rheumatology at San Francisco General Hospital.

Another research priority is identification of biomarkers in blood or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid to identify early on the subgroup of infected patients who are likely to crash and develop severe disease. That would permit a targeted approach to inhibition of the inflammatory pathways contributing to development of acute respiratory distress syndrome before this full-blown cytokine storm-like syndrome can occur. There is great interest in trying to achieve this by repurposing many biologic agents widely used by rheumatologists, including the interleukin-1 blocker anakinra (Kineret) and the IL-6 blocker tocilizumab (Actemra).

Dr. Matloubian reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

FROM SOTA 2020

Vaccination regimen effective in preventing pneumonia in MM patients

Patients with hematological malignancies are at high risk of invasive Staphylococcus pneumoniae. Multiple myeloma (MM) patients, in particular, have been found to have one of the highest incidences of invasive pneumococcal disease. However, researchers found that a full three-dose vaccination regimen by 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) vaccine was protective in MM patients when provided between treatment courses, according to a study reported in Vaccine.

The researchers performed a prospective study of 18 adult patients who were vaccinated with PCV13, compared with 18 control-matched patients from 2017 to 2020. The three-dose vaccination regimen was provided between treatment courses with novel target agents (bortezomib, lenalidomide, ixazomib) with a minimum of a 1-month interval. They used the incidence of pneumonias during the one-year observation period as the primary outcome.

Totally there were 12 cases (33.3%) of clinically and radiologically confirmed pneumonias in the entire study group (n = 36), with a distribution between the vaccinated and nonvaccinated groups of 3 (16.7%) and 9 (50%). respectively (P = .037).

The absolute risk reduction seen with vaccination was 33.3%, and the number needed to treat with PCV13 vaccination in MM patients receiving novel agents was 3.0; (95% confidence interval 1.61-22.1). In addition, there were no adverse effects seen from vaccination, according to the authors.

“Despite the expected decrease in immunological response to vaccination during the chemotherapy, we have shown the clinical effectiveness of a PCV13 vaccination schedule based on 3 doses given with a minimum 1 month interval between the courses of novel agents,” the investigators concluded.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Stoma I et al. Vaccine. 2020 May 14; doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.024.

Patients with hematological malignancies are at high risk of invasive Staphylococcus pneumoniae. Multiple myeloma (MM) patients, in particular, have been found to have one of the highest incidences of invasive pneumococcal disease. However, researchers found that a full three-dose vaccination regimen by 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) vaccine was protective in MM patients when provided between treatment courses, according to a study reported in Vaccine.

The researchers performed a prospective study of 18 adult patients who were vaccinated with PCV13, compared with 18 control-matched patients from 2017 to 2020. The three-dose vaccination regimen was provided between treatment courses with novel target agents (bortezomib, lenalidomide, ixazomib) with a minimum of a 1-month interval. They used the incidence of pneumonias during the one-year observation period as the primary outcome.

Totally there were 12 cases (33.3%) of clinically and radiologically confirmed pneumonias in the entire study group (n = 36), with a distribution between the vaccinated and nonvaccinated groups of 3 (16.7%) and 9 (50%). respectively (P = .037).

The absolute risk reduction seen with vaccination was 33.3%, and the number needed to treat with PCV13 vaccination in MM patients receiving novel agents was 3.0; (95% confidence interval 1.61-22.1). In addition, there were no adverse effects seen from vaccination, according to the authors.

“Despite the expected decrease in immunological response to vaccination during the chemotherapy, we have shown the clinical effectiveness of a PCV13 vaccination schedule based on 3 doses given with a minimum 1 month interval between the courses of novel agents,” the investigators concluded.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Stoma I et al. Vaccine. 2020 May 14; doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.024.

Patients with hematological malignancies are at high risk of invasive Staphylococcus pneumoniae. Multiple myeloma (MM) patients, in particular, have been found to have one of the highest incidences of invasive pneumococcal disease. However, researchers found that a full three-dose vaccination regimen by 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) vaccine was protective in MM patients when provided between treatment courses, according to a study reported in Vaccine.

The researchers performed a prospective study of 18 adult patients who were vaccinated with PCV13, compared with 18 control-matched patients from 2017 to 2020. The three-dose vaccination regimen was provided between treatment courses with novel target agents (bortezomib, lenalidomide, ixazomib) with a minimum of a 1-month interval. They used the incidence of pneumonias during the one-year observation period as the primary outcome.

Totally there were 12 cases (33.3%) of clinically and radiologically confirmed pneumonias in the entire study group (n = 36), with a distribution between the vaccinated and nonvaccinated groups of 3 (16.7%) and 9 (50%). respectively (P = .037).

The absolute risk reduction seen with vaccination was 33.3%, and the number needed to treat with PCV13 vaccination in MM patients receiving novel agents was 3.0; (95% confidence interval 1.61-22.1). In addition, there were no adverse effects seen from vaccination, according to the authors.

“Despite the expected decrease in immunological response to vaccination during the chemotherapy, we have shown the clinical effectiveness of a PCV13 vaccination schedule based on 3 doses given with a minimum 1 month interval between the courses of novel agents,” the investigators concluded.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Stoma I et al. Vaccine. 2020 May 14; doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.024.

FROM VACCINE

Atypical Features of COVID-19: A Literature Review

From the University of Florida College of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To review current reports on atypical manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Evidence regarding atypical features of COVID-19 is accumulating. SARS-CoV-2 can infect human cells that express the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, which would allow for a broad spectrum of illnesses affecting the renal, cardiac, and gastrointestinal organ systems. Neurologic, cutaneous, and musculoskeletal manifestations have also been reported. The potential for SARS-CoV-2 to induce a hypercoagulable state provides another avenue for the virus to indirectly damage various organ systems, as evidenced by reports of cerebrovascular disease, myocardial injury, and a chilblain-like rash in patients with COVID-19.

- Conclusion: Because the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 may occur with varying frequency across populations, it is important to keep differentials broad when assessing patients with a clinical illness that may indeed be COVID-19.

Keywords: coronavirus; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; SARS-CoV-2; pandemic.

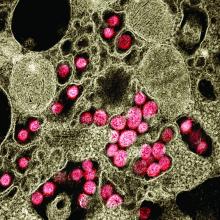

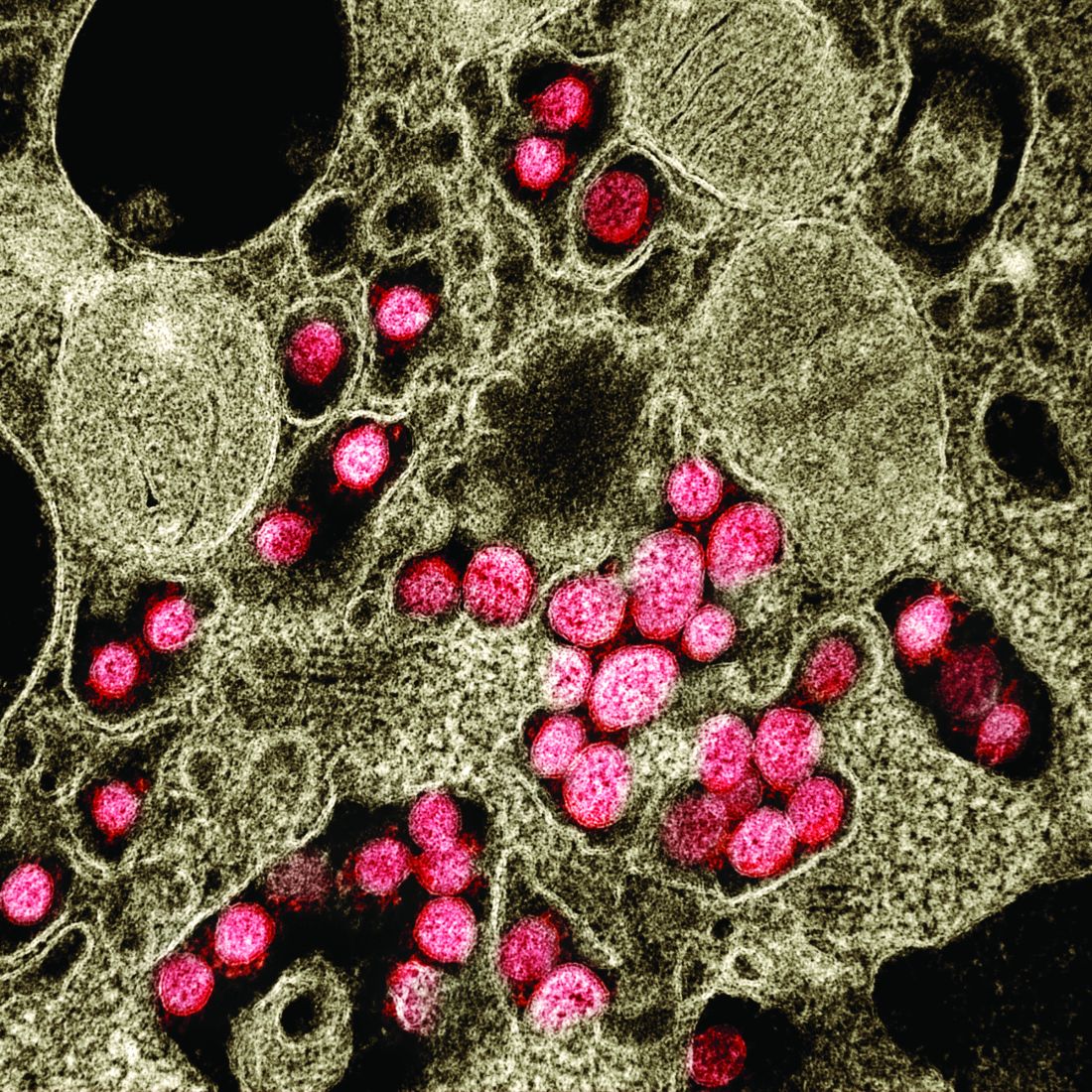

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the syndrome caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported in Wuhan, China, in early December 2019.1 Since then, the virus has spread quickly around the world, with the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic on March 11, 2020. As of May 21, 2020, more than 5,000,000 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, and more than 328,000 deaths related to COVID-19 have been reported globally.2 These numbers are expected to increase, due to the reproduction number (R0) of SARS-CoV-2. R0 represents the number of new infections generated by an infectious person in a totally naïve population.3 The WHO estimates that the R0 of SARS-CoV-2 is 1.95, with other estimates ranging from 1.4 to 6.49.3 To control the pathogen, the R0 needs to be brought under a value of 1.

A fundamental tool in lowering the R0 is prompt testing and isolation of those who display signs and symptoms of infection. SARS-CoV-2 is still a novel pathogen about which we know relatively little. The common symptoms of COVID-19 are now well known—including fever, fatigue, anorexia, cough, and shortness of breath—but atypical manifestations of this viral continue to be reported and described. To help clinicians across specialties and settings identify patients with possible infection, we have summarized findings from current reports on COVID-19 manifestations involving the renal, cardiac, gastrointestinal (GI), and other organ systems.

Renal

During the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak, acute kidney injury (AKI) was an uncommon complication of the infection, but early reports suggest that AKI may occur more commonly with COVID-19.4 In a study of 193 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 treated in 3 Chinese hospitals, 59% presented with proteinuria, 44% with hematuria, 14% with increased blood urea nitrogen, and 10% with increased levels of serum creatinine.4 These markers, indicative of AKI, may be associated with increased mortality. Among this cohort, those with AKI had a mortality risk 5.3 times higher than those who did not have AKI.4 The pathophysiology of renal disease in COVID-19 may be related to dehydration or inflammatory mediators, causing decreased renal perfusion and cytokine storm, but evidence also suggests that SARS-CoV-2 is able to directly infect kidney cells.5 The virus infects cells by using angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the cell membrane as a cell entry receptor; ACE2 is expressed on the kidney, heart, and GI cells, and this may allow SARS-CoV-2 to directly infect and damage these organs. Other potential mechanisms of renal injury include overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines and administration of nephrotoxic drugs. No matter the mechanism, however, increased serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen correlate with an increased likelihood of requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission.6 Therefore, clinicians should carefully monitor renal function in patients with COVID-19.

Cardiac

In a report of 138 Chinese patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 36 required ICU admission: 44.4% of these had arrhythmias and 22.2% had developed acute cardiac injury.6 In addition, the cardiac cell injury biomarker troponin I was more likely to be elevated in ICU patients.6 A study of 21 patients admitted to the ICU in Washington State found elevated levels of brain natriuretic peptide.7 These biomarkers reflect the presence of myocardial stress, but do not necessarily indicate direct myocardial infection. Case reports of fulminant myocarditis in those with COVID-19 have begun to surface, however.8,9 An examination of 68 deaths in persons with COVID-19 concluded that 7% were caused by myocarditis with circulatory failure.10

The pathophysiology of myocardial injury in COVID-19 is likely multifactorial. This includes increased inflammatory mediators, hypoxemia, and metabolic changes that can directly damage myocardial tissue. These factors can also exacerbate comorbid conditions, such as coronary artery disease, leading to ischemia and dysfunction of preexisting electrical conduction abnormalities. However, pathologic evidence of myocarditis and the presence of the ACE2 receptor, which may be a mediator of cardiac function, on cardiac muscle cells suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is capable of directly infecting and damaging myocardial cells. Other proposed mechanisms include infection-mediated downregulation of ACE2, causing cardiac dysfunction, or thrombus formation.11 Although respiratory failure is the most common source of advanced illness in COVID-19 patients, myocarditis and arrhythmias can be life-threatening manifestations of the disease.

Gastrointestinal

As noted, ACE2 is expressed in the GI tract. In 73 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 53.4% tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool, and 23.4% continued to have RNA-positive stool samples even after their respiratory samples tested negative.12 These findings suggest the potential for SARS-CoV-2 to spread through fecal-oral transmission in those who are asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic, or symptomatic. This mode of transmission has yet to be determined conclusively, and more research is needed. However, GI symptoms have been reported in persons with COVID-19. Among 138 hospitalized patients, 10.1% had complaints of diarrhea and nausea and 3.6% reported vomiting.6 Those who reported nausea and diarrhea noted that they developed these symptoms 1 to 2 days before they developed fever.6 Also, among a cohort of 1099 Chinese patients with COVID-19, 3.8% complained of diarrhea.13 Although diarrhea does not occur in a majority of patients, GI complaints, such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, should raise clinical suspicion for COVID-19, and in known areas of active transmission, testing of patients with GI symptoms is likely warranted.

Ocular

Ocular manifestations of COVID-19 are now being described, and should be taken into consideration when examining a patient. In a study of 38 patients with COVID-19 from Hubei province, China, 31.6% had ocular findings consistent with conjunctivitis, including conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, and increased ocular secretions.14 SARS-CoV-2 was detected in conjunctival and nasopharyngeal samples in 2 patients from this cohort. Conjunctival congestion was reported in a cohort of 1099 patients with COVID-19 treated at multiple centers throughout China, but at a much lower incidence, approximately 0.8%.13 Because SARS-CoV-2 can cause conjunctival disease and has been detected in samples from the external surface of the eye, it appears the virus is transmissible from tears or contact with the eye itself.

Neurologic

Common reported neurologic symptoms include dizziness, headache, impaired consciousness, ataxia, and cerebrovascular events. In a cohort of 214 patients from Wuhan, China, 36.4% had some form of neurological insult.15 These symptoms were more common in those with severe illness (P = 0.02).15 Two interesting neurologic symptoms that have been described are anosmia (loss of smell) and ageusia (loss of taste), which are being found primarily in tandem. It is still unclear how many people with COVID-19 are experiencing these symptoms, but a report from Italy estimates 19.4% of 320 patients examined had chemosensory dysfunction.16 The aforementioned report from Wuhan, China, found that 5.1% had anosmia and 5.6% had ageusia.15 The presence of anosmia/ageusia in some patients suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may enter the central nervous system (CNS) through a retrograde neuronal route.15 In addition, a case report from Japan described a 24-year-old man who presented with meningitis/encephalitis and had SARS-CoV-2 RNA present in his cerebrospinal fluid, showing that SARS-CoV-2 can penetrate into the CNS.17

SARS-CoV-2 may also have an association with Guillain–Barré syndrome, as this condition was reported in 5 patients from 3 hospitals in Northern Italy.18 The symptoms of Guillain–Barré syndrome presented 5 to 10 days after the typical COVID-19 symptoms, and evolved over 36 hours to 4 days afterwards. Four of the 5 patients experienced flaccid tetraparesis or tetraplegia, and 3 required mechanical ventilation.18

Another possible cause of neurologic injury in COVID-19 is damage to endothelial cells in cerebral blood vessels, causing thrombus formation and possibly increasing the risk of acute ischemic stroke.15,19 Supporting this mechanism of injury, significantly lower platelet counts were noted in patients with CNS symptoms (P = 0.005).15 Other hematological impacts of COVID-19 have been reported, particularly hypercoagulability, as evidenced by elevated D-dimer levels.13,20 This hypercoagulable state is linked to overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines (cytokine storm), leading to dysregulation of coagulation pathways and reduced concentrations of anticoagulants, such as protein C, antithrombin III, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor.21

Cutaneous

Cutaneous findings emerging in persons with COVID-19 demonstrate features of small-vessel and capillary occlusion, including erythematous skin eruptions and petechial rash. One report from Italy noted that 20.4% of patients with COVID-19 (n = 88) had a cutaneous finding, with a cutaneous manifestation developing in 8 at the onset of illness and in 10 following hospital admission.22 Fourteen patients had an erythematous rash, primarily on the trunk, with 3 patients having a diffuse urticarial appearing rash, and 1 patient developing vesicles.22 The severity of illness did not appear to correlate with the cutaneous manifestation, and the lesions healed within a few days.

One case report described a patient from Bangkok who was thought to be suffering from dengue fever, but was found to have SARS-CoV-2 infection. He initially presented with skin rash and petechiae, and later developed respiratory disease.23

Other dermatologic findings of COVID-19 resemble chilblains disease, colloquially referred to as “COVID toes.” Two women, 27 and 35 years old, presented to a dermatology clinic in Qatar with a chief complaint of skin rash, described as red-purple papules on the dorsal aspects of the fingers bilaterally.22 Both patients had an unremarkable medical and drug history, but recent travel to the United Kingdom dictated SARS-CoV-2 screening, which was positive.24 An Italian case report describes a 23-year-old man who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and had violaceous plaques on an erythematous background on his feet, without any lesions on his hands.25 Since chilblains is less common in the warmer months and these events correspond with the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 infection is the suspected etiology. The pathophysiology of these lesions is unclear, and more research is needed. As more data become available, we may see cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID-19 similar to those commonly reported with other viral infectious processes.

Musculoskeletal

Of 138 patients hospitalized in Wuhan, China, for COVID-19, 34.8% presented with myalgia; the presence of myalgia does not appear to be correlated with an increased likelihood of ICU admission.6 Myalgia or arthralgia was also reported in 14.9% among the cohort of 1099 COVID-19 patients in China.13 These musculoskeletal symptoms are described among large muscle groups found in the extremities, trunk, and back, and should raise suspicion in patients who present with other signs and symptoms concerning for COVID-19.

Conclusion

Evidence regarding atypical features of COVID-19 is accumulating. SARS-CoV-2 can infect a human cells that express the ACE2 receptor, which would allow for a broad spectrum of illnesses. The potential for SARS-CoV-2 to induce a hypercoagulable state allows it to indirectly damage various organ systems,20 leading to cerebrovascular disease, myocardial injury, and a chilblain-like rash. Clinicians must be aware of these unique features, as early recognition of persons who present with COVID-19 will allow for prompt testing, institution of infection control and isolation practices, and treatment, as needed, among those infected. Also, this is a pandemic involving a novel virus affecting different populations throughout the world, and these signs and symptoms may occur with varying frequency across populations. Therefore, it is important to keep differentials broad when assessing patients with a clinical illness that may indeed be COVID-19.

Corresponding author: Norman L. Beatty, MD, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [press release]. World Health Organization; March 11, 2020.

2. Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins CSSE. https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 Accessed May 15, 2020.

3. Liu Y, Gayle AA, Wilder-Smith A, Rocklöv J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2):taaa021. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa021

4. Li Z, Wu M, Guo J, et al. Caution on kidney dysfunctions of 2019-nCoV patients. medRxiv preprint. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.08.20021212

5. Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450-454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145.

6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

7. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612‐1614. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4326

8. Chen C, Zhou Y, Wang DW. SARS-CoV-2: a potential novel etiology of fulminant myocarditis. Herz. 2020;45:230-232. doi: 10.1007/s00059-020-04909-z

9. Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2020 Mar 16;ehaa190. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190

10. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:846-848. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x

11. Akhmerov A, Marban E. COVID-19 and the heart. Circ Res. 2020;126:1443-1455. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317055

12. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831-1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055

13. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1078-1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

14. Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, et al. Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar 31;e201291. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291

15. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127

16. Vaira LA, Salzano G, Deiana G, De Riu G. Anosmia and ageusia: common findings in COVID-19 patients. Laryngoscope. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1002/lary.28692

17. Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55-58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062

18. Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 17;NEJMc2009191. doi:10.1056/nejmc2009191

19. Dafer RM, Osteraas ND, Biller J. Acute stroke care in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Stroke Cerebrovascular Dis. 2020 Apr 17:104881. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104881

20. Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020;10.1002/ajh.25829. doi:10.1002/ajh.25829

21. Jose RJ, Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;S2213-2600(20)30216-2. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2

22. Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387

23. Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):e177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036

24. Alramthan A, Aldaraji W. A Case of COVID‐19 presenting in clinical picture resembling chilblains disease. First report from the Middle East. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020 Apr 17. doi: 10.1111/ced.14243

25. Kolivras A, Dehavay F, Delplace D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection–induced chilblains: a case report with histopathologic findings. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Apr 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.011

From the University of Florida College of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To review current reports on atypical manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Evidence regarding atypical features of COVID-19 is accumulating. SARS-CoV-2 can infect human cells that express the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, which would allow for a broad spectrum of illnesses affecting the renal, cardiac, and gastrointestinal organ systems. Neurologic, cutaneous, and musculoskeletal manifestations have also been reported. The potential for SARS-CoV-2 to induce a hypercoagulable state provides another avenue for the virus to indirectly damage various organ systems, as evidenced by reports of cerebrovascular disease, myocardial injury, and a chilblain-like rash in patients with COVID-19.

- Conclusion: Because the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 may occur with varying frequency across populations, it is important to keep differentials broad when assessing patients with a clinical illness that may indeed be COVID-19.

Keywords: coronavirus; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; SARS-CoV-2; pandemic.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the syndrome caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported in Wuhan, China, in early December 2019.1 Since then, the virus has spread quickly around the world, with the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic on March 11, 2020. As of May 21, 2020, more than 5,000,000 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, and more than 328,000 deaths related to COVID-19 have been reported globally.2 These numbers are expected to increase, due to the reproduction number (R0) of SARS-CoV-2. R0 represents the number of new infections generated by an infectious person in a totally naïve population.3 The WHO estimates that the R0 of SARS-CoV-2 is 1.95, with other estimates ranging from 1.4 to 6.49.3 To control the pathogen, the R0 needs to be brought under a value of 1.

A fundamental tool in lowering the R0 is prompt testing and isolation of those who display signs and symptoms of infection. SARS-CoV-2 is still a novel pathogen about which we know relatively little. The common symptoms of COVID-19 are now well known—including fever, fatigue, anorexia, cough, and shortness of breath—but atypical manifestations of this viral continue to be reported and described. To help clinicians across specialties and settings identify patients with possible infection, we have summarized findings from current reports on COVID-19 manifestations involving the renal, cardiac, gastrointestinal (GI), and other organ systems.

Renal

During the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak, acute kidney injury (AKI) was an uncommon complication of the infection, but early reports suggest that AKI may occur more commonly with COVID-19.4 In a study of 193 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 treated in 3 Chinese hospitals, 59% presented with proteinuria, 44% with hematuria, 14% with increased blood urea nitrogen, and 10% with increased levels of serum creatinine.4 These markers, indicative of AKI, may be associated with increased mortality. Among this cohort, those with AKI had a mortality risk 5.3 times higher than those who did not have AKI.4 The pathophysiology of renal disease in COVID-19 may be related to dehydration or inflammatory mediators, causing decreased renal perfusion and cytokine storm, but evidence also suggests that SARS-CoV-2 is able to directly infect kidney cells.5 The virus infects cells by using angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the cell membrane as a cell entry receptor; ACE2 is expressed on the kidney, heart, and GI cells, and this may allow SARS-CoV-2 to directly infect and damage these organs. Other potential mechanisms of renal injury include overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines and administration of nephrotoxic drugs. No matter the mechanism, however, increased serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen correlate with an increased likelihood of requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission.6 Therefore, clinicians should carefully monitor renal function in patients with COVID-19.

Cardiac

In a report of 138 Chinese patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 36 required ICU admission: 44.4% of these had arrhythmias and 22.2% had developed acute cardiac injury.6 In addition, the cardiac cell injury biomarker troponin I was more likely to be elevated in ICU patients.6 A study of 21 patients admitted to the ICU in Washington State found elevated levels of brain natriuretic peptide.7 These biomarkers reflect the presence of myocardial stress, but do not necessarily indicate direct myocardial infection. Case reports of fulminant myocarditis in those with COVID-19 have begun to surface, however.8,9 An examination of 68 deaths in persons with COVID-19 concluded that 7% were caused by myocarditis with circulatory failure.10

The pathophysiology of myocardial injury in COVID-19 is likely multifactorial. This includes increased inflammatory mediators, hypoxemia, and metabolic changes that can directly damage myocardial tissue. These factors can also exacerbate comorbid conditions, such as coronary artery disease, leading to ischemia and dysfunction of preexisting electrical conduction abnormalities. However, pathologic evidence of myocarditis and the presence of the ACE2 receptor, which may be a mediator of cardiac function, on cardiac muscle cells suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is capable of directly infecting and damaging myocardial cells. Other proposed mechanisms include infection-mediated downregulation of ACE2, causing cardiac dysfunction, or thrombus formation.11 Although respiratory failure is the most common source of advanced illness in COVID-19 patients, myocarditis and arrhythmias can be life-threatening manifestations of the disease.

Gastrointestinal

As noted, ACE2 is expressed in the GI tract. In 73 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 53.4% tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool, and 23.4% continued to have RNA-positive stool samples even after their respiratory samples tested negative.12 These findings suggest the potential for SARS-CoV-2 to spread through fecal-oral transmission in those who are asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic, or symptomatic. This mode of transmission has yet to be determined conclusively, and more research is needed. However, GI symptoms have been reported in persons with COVID-19. Among 138 hospitalized patients, 10.1% had complaints of diarrhea and nausea and 3.6% reported vomiting.6 Those who reported nausea and diarrhea noted that they developed these symptoms 1 to 2 days before they developed fever.6 Also, among a cohort of 1099 Chinese patients with COVID-19, 3.8% complained of diarrhea.13 Although diarrhea does not occur in a majority of patients, GI complaints, such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, should raise clinical suspicion for COVID-19, and in known areas of active transmission, testing of patients with GI symptoms is likely warranted.

Ocular

Ocular manifestations of COVID-19 are now being described, and should be taken into consideration when examining a patient. In a study of 38 patients with COVID-19 from Hubei province, China, 31.6% had ocular findings consistent with conjunctivitis, including conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, and increased ocular secretions.14 SARS-CoV-2 was detected in conjunctival and nasopharyngeal samples in 2 patients from this cohort. Conjunctival congestion was reported in a cohort of 1099 patients with COVID-19 treated at multiple centers throughout China, but at a much lower incidence, approximately 0.8%.13 Because SARS-CoV-2 can cause conjunctival disease and has been detected in samples from the external surface of the eye, it appears the virus is transmissible from tears or contact with the eye itself.

Neurologic

Common reported neurologic symptoms include dizziness, headache, impaired consciousness, ataxia, and cerebrovascular events. In a cohort of 214 patients from Wuhan, China, 36.4% had some form of neurological insult.15 These symptoms were more common in those with severe illness (P = 0.02).15 Two interesting neurologic symptoms that have been described are anosmia (loss of smell) and ageusia (loss of taste), which are being found primarily in tandem. It is still unclear how many people with COVID-19 are experiencing these symptoms, but a report from Italy estimates 19.4% of 320 patients examined had chemosensory dysfunction.16 The aforementioned report from Wuhan, China, found that 5.1% had anosmia and 5.6% had ageusia.15 The presence of anosmia/ageusia in some patients suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may enter the central nervous system (CNS) through a retrograde neuronal route.15 In addition, a case report from Japan described a 24-year-old man who presented with meningitis/encephalitis and had SARS-CoV-2 RNA present in his cerebrospinal fluid, showing that SARS-CoV-2 can penetrate into the CNS.17

SARS-CoV-2 may also have an association with Guillain–Barré syndrome, as this condition was reported in 5 patients from 3 hospitals in Northern Italy.18 The symptoms of Guillain–Barré syndrome presented 5 to 10 days after the typical COVID-19 symptoms, and evolved over 36 hours to 4 days afterwards. Four of the 5 patients experienced flaccid tetraparesis or tetraplegia, and 3 required mechanical ventilation.18

Another possible cause of neurologic injury in COVID-19 is damage to endothelial cells in cerebral blood vessels, causing thrombus formation and possibly increasing the risk of acute ischemic stroke.15,19 Supporting this mechanism of injury, significantly lower platelet counts were noted in patients with CNS symptoms (P = 0.005).15 Other hematological impacts of COVID-19 have been reported, particularly hypercoagulability, as evidenced by elevated D-dimer levels.13,20 This hypercoagulable state is linked to overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines (cytokine storm), leading to dysregulation of coagulation pathways and reduced concentrations of anticoagulants, such as protein C, antithrombin III, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor.21

Cutaneous

Cutaneous findings emerging in persons with COVID-19 demonstrate features of small-vessel and capillary occlusion, including erythematous skin eruptions and petechial rash. One report from Italy noted that 20.4% of patients with COVID-19 (n = 88) had a cutaneous finding, with a cutaneous manifestation developing in 8 at the onset of illness and in 10 following hospital admission.22 Fourteen patients had an erythematous rash, primarily on the trunk, with 3 patients having a diffuse urticarial appearing rash, and 1 patient developing vesicles.22 The severity of illness did not appear to correlate with the cutaneous manifestation, and the lesions healed within a few days.

One case report described a patient from Bangkok who was thought to be suffering from dengue fever, but was found to have SARS-CoV-2 infection. He initially presented with skin rash and petechiae, and later developed respiratory disease.23

Other dermatologic findings of COVID-19 resemble chilblains disease, colloquially referred to as “COVID toes.” Two women, 27 and 35 years old, presented to a dermatology clinic in Qatar with a chief complaint of skin rash, described as red-purple papules on the dorsal aspects of the fingers bilaterally.22 Both patients had an unremarkable medical and drug history, but recent travel to the United Kingdom dictated SARS-CoV-2 screening, which was positive.24 An Italian case report describes a 23-year-old man who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and had violaceous plaques on an erythematous background on his feet, without any lesions on his hands.25 Since chilblains is less common in the warmer months and these events correspond with the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 infection is the suspected etiology. The pathophysiology of these lesions is unclear, and more research is needed. As more data become available, we may see cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID-19 similar to those commonly reported with other viral infectious processes.

Musculoskeletal

Of 138 patients hospitalized in Wuhan, China, for COVID-19, 34.8% presented with myalgia; the presence of myalgia does not appear to be correlated with an increased likelihood of ICU admission.6 Myalgia or arthralgia was also reported in 14.9% among the cohort of 1099 COVID-19 patients in China.13 These musculoskeletal symptoms are described among large muscle groups found in the extremities, trunk, and back, and should raise suspicion in patients who present with other signs and symptoms concerning for COVID-19.

Conclusion

Evidence regarding atypical features of COVID-19 is accumulating. SARS-CoV-2 can infect a human cells that express the ACE2 receptor, which would allow for a broad spectrum of illnesses. The potential for SARS-CoV-2 to induce a hypercoagulable state allows it to indirectly damage various organ systems,20 leading to cerebrovascular disease, myocardial injury, and a chilblain-like rash. Clinicians must be aware of these unique features, as early recognition of persons who present with COVID-19 will allow for prompt testing, institution of infection control and isolation practices, and treatment, as needed, among those infected. Also, this is a pandemic involving a novel virus affecting different populations throughout the world, and these signs and symptoms may occur with varying frequency across populations. Therefore, it is important to keep differentials broad when assessing patients with a clinical illness that may indeed be COVID-19.

Corresponding author: Norman L. Beatty, MD, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the University of Florida College of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To review current reports on atypical manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Evidence regarding atypical features of COVID-19 is accumulating. SARS-CoV-2 can infect human cells that express the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, which would allow for a broad spectrum of illnesses affecting the renal, cardiac, and gastrointestinal organ systems. Neurologic, cutaneous, and musculoskeletal manifestations have also been reported. The potential for SARS-CoV-2 to induce a hypercoagulable state provides another avenue for the virus to indirectly damage various organ systems, as evidenced by reports of cerebrovascular disease, myocardial injury, and a chilblain-like rash in patients with COVID-19.

- Conclusion: Because the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 may occur with varying frequency across populations, it is important to keep differentials broad when assessing patients with a clinical illness that may indeed be COVID-19.

Keywords: coronavirus; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; SARS-CoV-2; pandemic.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the syndrome caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported in Wuhan, China, in early December 2019.1 Since then, the virus has spread quickly around the world, with the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic on March 11, 2020. As of May 21, 2020, more than 5,000,000 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, and more than 328,000 deaths related to COVID-19 have been reported globally.2 These numbers are expected to increase, due to the reproduction number (R0) of SARS-CoV-2. R0 represents the number of new infections generated by an infectious person in a totally naïve population.3 The WHO estimates that the R0 of SARS-CoV-2 is 1.95, with other estimates ranging from 1.4 to 6.49.3 To control the pathogen, the R0 needs to be brought under a value of 1.

A fundamental tool in lowering the R0 is prompt testing and isolation of those who display signs and symptoms of infection. SARS-CoV-2 is still a novel pathogen about which we know relatively little. The common symptoms of COVID-19 are now well known—including fever, fatigue, anorexia, cough, and shortness of breath—but atypical manifestations of this viral continue to be reported and described. To help clinicians across specialties and settings identify patients with possible infection, we have summarized findings from current reports on COVID-19 manifestations involving the renal, cardiac, gastrointestinal (GI), and other organ systems.

Renal

During the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak, acute kidney injury (AKI) was an uncommon complication of the infection, but early reports suggest that AKI may occur more commonly with COVID-19.4 In a study of 193 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 treated in 3 Chinese hospitals, 59% presented with proteinuria, 44% with hematuria, 14% with increased blood urea nitrogen, and 10% with increased levels of serum creatinine.4 These markers, indicative of AKI, may be associated with increased mortality. Among this cohort, those with AKI had a mortality risk 5.3 times higher than those who did not have AKI.4 The pathophysiology of renal disease in COVID-19 may be related to dehydration or inflammatory mediators, causing decreased renal perfusion and cytokine storm, but evidence also suggests that SARS-CoV-2 is able to directly infect kidney cells.5 The virus infects cells by using angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the cell membrane as a cell entry receptor; ACE2 is expressed on the kidney, heart, and GI cells, and this may allow SARS-CoV-2 to directly infect and damage these organs. Other potential mechanisms of renal injury include overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines and administration of nephrotoxic drugs. No matter the mechanism, however, increased serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen correlate with an increased likelihood of requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission.6 Therefore, clinicians should carefully monitor renal function in patients with COVID-19.

Cardiac

In a report of 138 Chinese patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 36 required ICU admission: 44.4% of these had arrhythmias and 22.2% had developed acute cardiac injury.6 In addition, the cardiac cell injury biomarker troponin I was more likely to be elevated in ICU patients.6 A study of 21 patients admitted to the ICU in Washington State found elevated levels of brain natriuretic peptide.7 These biomarkers reflect the presence of myocardial stress, but do not necessarily indicate direct myocardial infection. Case reports of fulminant myocarditis in those with COVID-19 have begun to surface, however.8,9 An examination of 68 deaths in persons with COVID-19 concluded that 7% were caused by myocarditis with circulatory failure.10

The pathophysiology of myocardial injury in COVID-19 is likely multifactorial. This includes increased inflammatory mediators, hypoxemia, and metabolic changes that can directly damage myocardial tissue. These factors can also exacerbate comorbid conditions, such as coronary artery disease, leading to ischemia and dysfunction of preexisting electrical conduction abnormalities. However, pathologic evidence of myocarditis and the presence of the ACE2 receptor, which may be a mediator of cardiac function, on cardiac muscle cells suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is capable of directly infecting and damaging myocardial cells. Other proposed mechanisms include infection-mediated downregulation of ACE2, causing cardiac dysfunction, or thrombus formation.11 Although respiratory failure is the most common source of advanced illness in COVID-19 patients, myocarditis and arrhythmias can be life-threatening manifestations of the disease.

Gastrointestinal

As noted, ACE2 is expressed in the GI tract. In 73 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 53.4% tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool, and 23.4% continued to have RNA-positive stool samples even after their respiratory samples tested negative.12 These findings suggest the potential for SARS-CoV-2 to spread through fecal-oral transmission in those who are asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic, or symptomatic. This mode of transmission has yet to be determined conclusively, and more research is needed. However, GI symptoms have been reported in persons with COVID-19. Among 138 hospitalized patients, 10.1% had complaints of diarrhea and nausea and 3.6% reported vomiting.6 Those who reported nausea and diarrhea noted that they developed these symptoms 1 to 2 days before they developed fever.6 Also, among a cohort of 1099 Chinese patients with COVID-19, 3.8% complained of diarrhea.13 Although diarrhea does not occur in a majority of patients, GI complaints, such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, should raise clinical suspicion for COVID-19, and in known areas of active transmission, testing of patients with GI symptoms is likely warranted.

Ocular

Ocular manifestations of COVID-19 are now being described, and should be taken into consideration when examining a patient. In a study of 38 patients with COVID-19 from Hubei province, China, 31.6% had ocular findings consistent with conjunctivitis, including conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, and increased ocular secretions.14 SARS-CoV-2 was detected in conjunctival and nasopharyngeal samples in 2 patients from this cohort. Conjunctival congestion was reported in a cohort of 1099 patients with COVID-19 treated at multiple centers throughout China, but at a much lower incidence, approximately 0.8%.13 Because SARS-CoV-2 can cause conjunctival disease and has been detected in samples from the external surface of the eye, it appears the virus is transmissible from tears or contact with the eye itself.

Neurologic

Common reported neurologic symptoms include dizziness, headache, impaired consciousness, ataxia, and cerebrovascular events. In a cohort of 214 patients from Wuhan, China, 36.4% had some form of neurological insult.15 These symptoms were more common in those with severe illness (P = 0.02).15 Two interesting neurologic symptoms that have been described are anosmia (loss of smell) and ageusia (loss of taste), which are being found primarily in tandem. It is still unclear how many people with COVID-19 are experiencing these symptoms, but a report from Italy estimates 19.4% of 320 patients examined had chemosensory dysfunction.16 The aforementioned report from Wuhan, China, found that 5.1% had anosmia and 5.6% had ageusia.15 The presence of anosmia/ageusia in some patients suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may enter the central nervous system (CNS) through a retrograde neuronal route.15 In addition, a case report from Japan described a 24-year-old man who presented with meningitis/encephalitis and had SARS-CoV-2 RNA present in his cerebrospinal fluid, showing that SARS-CoV-2 can penetrate into the CNS.17

SARS-CoV-2 may also have an association with Guillain–Barré syndrome, as this condition was reported in 5 patients from 3 hospitals in Northern Italy.18 The symptoms of Guillain–Barré syndrome presented 5 to 10 days after the typical COVID-19 symptoms, and evolved over 36 hours to 4 days afterwards. Four of the 5 patients experienced flaccid tetraparesis or tetraplegia, and 3 required mechanical ventilation.18

Another possible cause of neurologic injury in COVID-19 is damage to endothelial cells in cerebral blood vessels, causing thrombus formation and possibly increasing the risk of acute ischemic stroke.15,19 Supporting this mechanism of injury, significantly lower platelet counts were noted in patients with CNS symptoms (P = 0.005).15 Other hematological impacts of COVID-19 have been reported, particularly hypercoagulability, as evidenced by elevated D-dimer levels.13,20 This hypercoagulable state is linked to overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines (cytokine storm), leading to dysregulation of coagulation pathways and reduced concentrations of anticoagulants, such as protein C, antithrombin III, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor.21

Cutaneous

Cutaneous findings emerging in persons with COVID-19 demonstrate features of small-vessel and capillary occlusion, including erythematous skin eruptions and petechial rash. One report from Italy noted that 20.4% of patients with COVID-19 (n = 88) had a cutaneous finding, with a cutaneous manifestation developing in 8 at the onset of illness and in 10 following hospital admission.22 Fourteen patients had an erythematous rash, primarily on the trunk, with 3 patients having a diffuse urticarial appearing rash, and 1 patient developing vesicles.22 The severity of illness did not appear to correlate with the cutaneous manifestation, and the lesions healed within a few days.

One case report described a patient from Bangkok who was thought to be suffering from dengue fever, but was found to have SARS-CoV-2 infection. He initially presented with skin rash and petechiae, and later developed respiratory disease.23

Other dermatologic findings of COVID-19 resemble chilblains disease, colloquially referred to as “COVID toes.” Two women, 27 and 35 years old, presented to a dermatology clinic in Qatar with a chief complaint of skin rash, described as red-purple papules on the dorsal aspects of the fingers bilaterally.22 Both patients had an unremarkable medical and drug history, but recent travel to the United Kingdom dictated SARS-CoV-2 screening, which was positive.24 An Italian case report describes a 23-year-old man who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and had violaceous plaques on an erythematous background on his feet, without any lesions on his hands.25 Since chilblains is less common in the warmer months and these events correspond with the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 infection is the suspected etiology. The pathophysiology of these lesions is unclear, and more research is needed. As more data become available, we may see cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID-19 similar to those commonly reported with other viral infectious processes.

Musculoskeletal

Of 138 patients hospitalized in Wuhan, China, for COVID-19, 34.8% presented with myalgia; the presence of myalgia does not appear to be correlated with an increased likelihood of ICU admission.6 Myalgia or arthralgia was also reported in 14.9% among the cohort of 1099 COVID-19 patients in China.13 These musculoskeletal symptoms are described among large muscle groups found in the extremities, trunk, and back, and should raise suspicion in patients who present with other signs and symptoms concerning for COVID-19.

Conclusion

Evidence regarding atypical features of COVID-19 is accumulating. SARS-CoV-2 can infect a human cells that express the ACE2 receptor, which would allow for a broad spectrum of illnesses. The potential for SARS-CoV-2 to induce a hypercoagulable state allows it to indirectly damage various organ systems,20 leading to cerebrovascular disease, myocardial injury, and a chilblain-like rash. Clinicians must be aware of these unique features, as early recognition of persons who present with COVID-19 will allow for prompt testing, institution of infection control and isolation practices, and treatment, as needed, among those infected. Also, this is a pandemic involving a novel virus affecting different populations throughout the world, and these signs and symptoms may occur with varying frequency across populations. Therefore, it is important to keep differentials broad when assessing patients with a clinical illness that may indeed be COVID-19.

Corresponding author: Norman L. Beatty, MD, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [press release]. World Health Organization; March 11, 2020.

2. Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins CSSE. https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 Accessed May 15, 2020.

3. Liu Y, Gayle AA, Wilder-Smith A, Rocklöv J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2):taaa021. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa021

4. Li Z, Wu M, Guo J, et al. Caution on kidney dysfunctions of 2019-nCoV patients. medRxiv preprint. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.08.20021212

5. Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450-454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145.

6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

7. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612‐1614. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4326

8. Chen C, Zhou Y, Wang DW. SARS-CoV-2: a potential novel etiology of fulminant myocarditis. Herz. 2020;45:230-232. doi: 10.1007/s00059-020-04909-z

9. Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2020 Mar 16;ehaa190. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190

10. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:846-848. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x

11. Akhmerov A, Marban E. COVID-19 and the heart. Circ Res. 2020;126:1443-1455. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317055

12. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831-1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055

13. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1078-1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

14. Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, et al. Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar 31;e201291. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291

15. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127

16. Vaira LA, Salzano G, Deiana G, De Riu G. Anosmia and ageusia: common findings in COVID-19 patients. Laryngoscope. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1002/lary.28692

17. Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55-58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062

18. Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 17;NEJMc2009191. doi:10.1056/nejmc2009191

19. Dafer RM, Osteraas ND, Biller J. Acute stroke care in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Stroke Cerebrovascular Dis. 2020 Apr 17:104881. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104881

20. Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020;10.1002/ajh.25829. doi:10.1002/ajh.25829

21. Jose RJ, Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;S2213-2600(20)30216-2. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2

22. Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387

23. Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):e177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036

24. Alramthan A, Aldaraji W. A Case of COVID‐19 presenting in clinical picture resembling chilblains disease. First report from the Middle East. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020 Apr 17. doi: 10.1111/ced.14243

25. Kolivras A, Dehavay F, Delplace D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection–induced chilblains: a case report with histopathologic findings. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Apr 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.011

1. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [press release]. World Health Organization; March 11, 2020.

2. Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins CSSE. https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 Accessed May 15, 2020.

3. Liu Y, Gayle AA, Wilder-Smith A, Rocklöv J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2):taaa021. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa021

4. Li Z, Wu M, Guo J, et al. Caution on kidney dysfunctions of 2019-nCoV patients. medRxiv preprint. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.08.20021212

5. Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450-454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145.

6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

7. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612‐1614. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4326

8. Chen C, Zhou Y, Wang DW. SARS-CoV-2: a potential novel etiology of fulminant myocarditis. Herz. 2020;45:230-232. doi: 10.1007/s00059-020-04909-z

9. Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2020 Mar 16;ehaa190. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190

10. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:846-848. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x

11. Akhmerov A, Marban E. COVID-19 and the heart. Circ Res. 2020;126:1443-1455. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317055

12. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831-1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055

13. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1078-1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

14. Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, et al. Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar 31;e201291. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291

15. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127

16. Vaira LA, Salzano G, Deiana G, De Riu G. Anosmia and ageusia: common findings in COVID-19 patients. Laryngoscope. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1002/lary.28692

17. Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55-58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062

18. Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 17;NEJMc2009191. doi:10.1056/nejmc2009191

19. Dafer RM, Osteraas ND, Biller J. Acute stroke care in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Stroke Cerebrovascular Dis. 2020 Apr 17:104881. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104881

20. Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020;10.1002/ajh.25829. doi:10.1002/ajh.25829

21. Jose RJ, Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;S2213-2600(20)30216-2. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2

22. Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387

23. Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):e177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036

24. Alramthan A, Aldaraji W. A Case of COVID‐19 presenting in clinical picture resembling chilblains disease. First report from the Middle East. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020 Apr 17. doi: 10.1111/ced.14243

25. Kolivras A, Dehavay F, Delplace D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection–induced chilblains: a case report with histopathologic findings. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Apr 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.011

Remdesivir in Hospitalized Adults With Severe COVID-19: Lessons Learned From the First Randomized Trial

Study Overview

Objective. To assess the efficacy, safety, and clinical benefit of remdesivir in hospitalized adults with confirmed pneumonia due to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Design. Randomized, investigator-initiated, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial.

Setting and participants. The trial took place between February 6, 2020 and March 12, 2020, at 10 hospitals in Wuhan, China. Study participants included adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) admitted to hospital who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay and had the following clinical characteristics: radiographic evidence of pneumonia; hypoxia with oxygen saturation ≤ 94% on room air or a ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen ≤ 300 mm Hg; and symptom onset to enrollment ≤ 12 days. Some of the exclusion criteria for participation in the study were pregnancy or breast feeding, liver cirrhosis, abnormal liver enzymes ≥ 5 times the upper limit of normal, severe renal impairment or receipt of renal replacement therapy, plan for transfer to a non-study hospital, and enrollment in a trial for COVID-19 within the previous month.

Intervention. Participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to the remdesivir group or the placebo group and were administered either intravenous infusions of remdesivir (200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg daily on days 2-10) or the same volume of placebo for 10 days. Clinical and safety data assessed included laboratory testing, electrocardiogram, and medication adverse effects. Testing of oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal swab samples, anal swab samples, sputum, and stool was performed for viral RNA detection and quantification on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28.