User login

COVID-19: Managing resource crunch and ethical challenges

COVID-19 has been a watershed event in medical history of epic proportions. With this fast-spreading pandemic stretching resources at health care institutions, practical considerations for management of a disease about which we are still learning has been a huge challenge.

Although many guidelines have been made available by medical societies and experts worldwide, there appear to be very few which throw light on management in a resource-poor setup. The hospitalist, as a front-line provider, is likely expected to lead the planning and management of resources in order to deliver appropriate care.

As per American Hospital Association data, there are 2,704 community hospitals that can deliver ICU care in the United States. There are 534,964 acute care beds with 96,596 ICU beds. Additionally, there are 25,157 step-down beds and 1,183 burn unit beds. Of the 2,704 hospitals, 74% are in metropolitan areas (> 50,000 population), 17% (464) are in micropolitan areas (10,000-49,999 population), and the remaining 9% (244) are in rural areas. Only 7% (36,453) of hospital beds and 5% (4715) of ICU beds are in micropolitan areas. Two percent of acute care hospital beds and 1% of ICU beds are in rural areas. Although the US has the highest per capita number of ICU beds in the world, this may not be sufficient as these are concentrated in highly populated metropolitan areas.

Infrastructure and human power resource augmentation will be important. Infrastructure can be ramped up by:

- Canceling elective procedures

- Using the operating room and perioperative room ventilators and beds

- Servicing and using older functioning hospitals, medical wards, and ventilators.

As ventilators are expected to be in short supply, while far from ideal, other resources may include using ventilators from the Strategic National Stockpile, renting from vendors, and using state-owned stockpiles. Use of non-invasive ventilators, such as CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), BiPAP (bi-level positive airway pressure), and HFNC (high-flow nasal cannula) may be considered in addition to full-featured ventilators. Rapidly manufacturing new ventilators with government direction is also being undertaken.

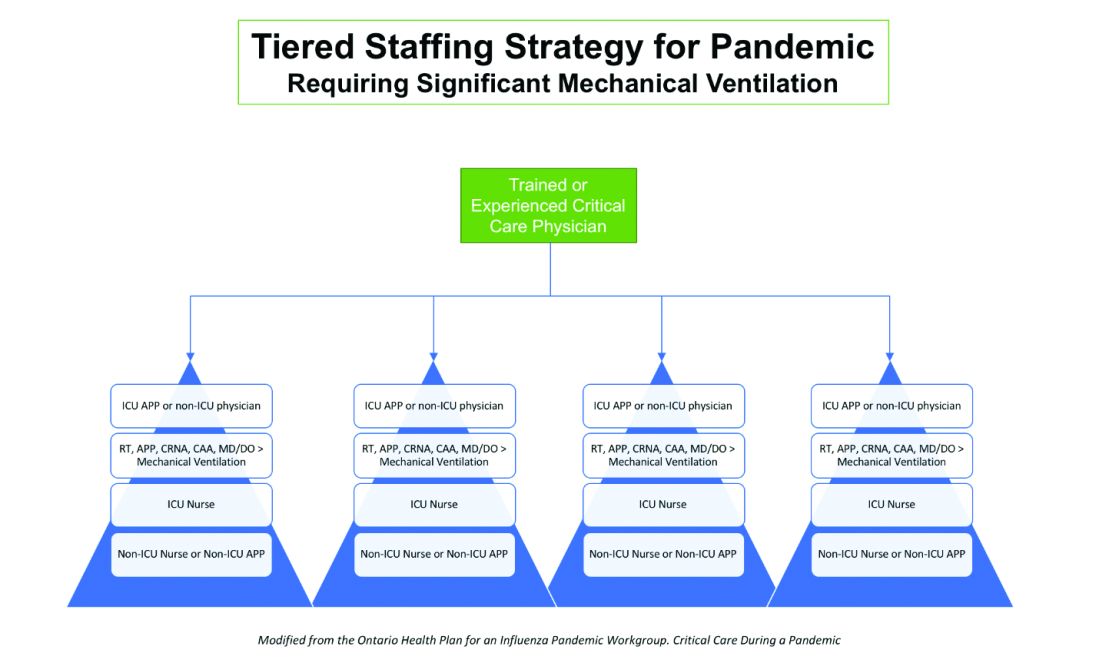

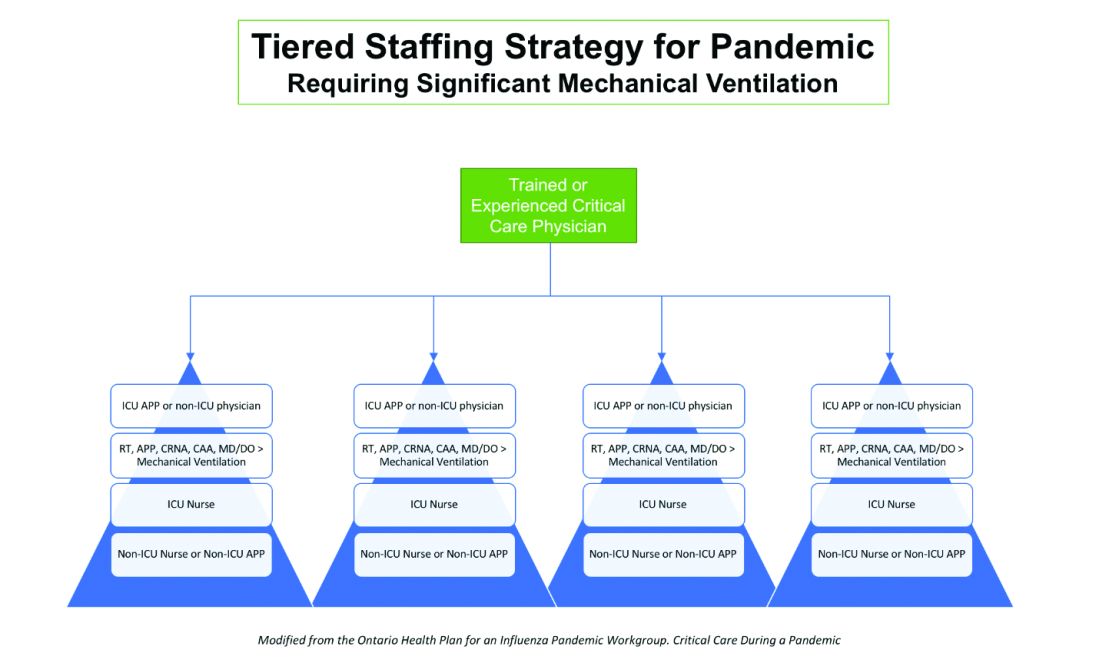

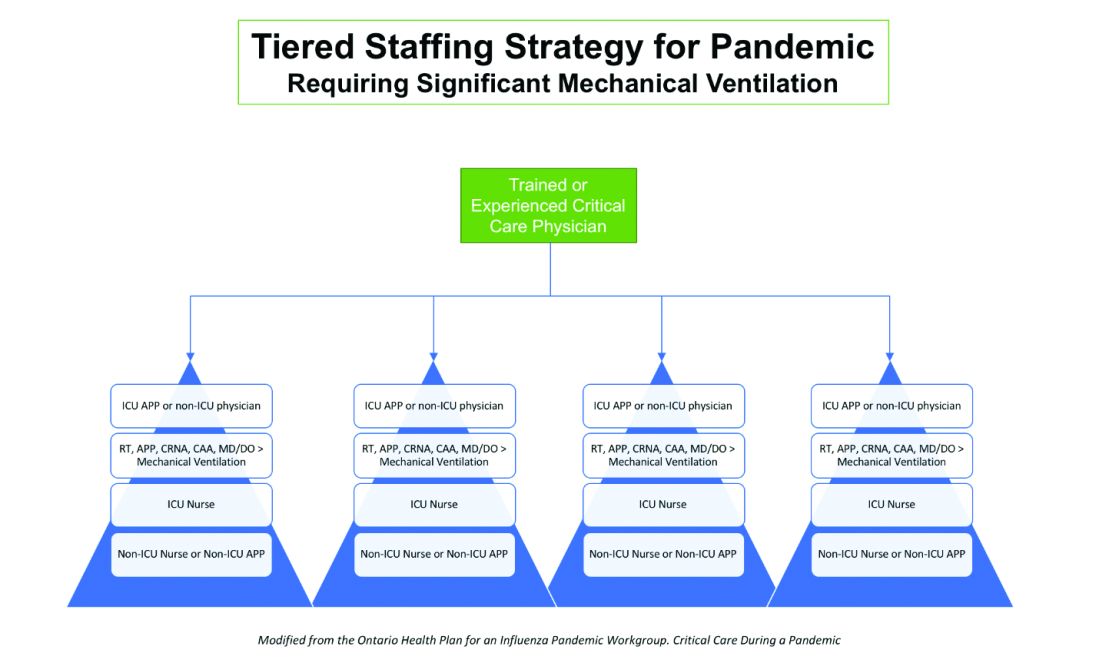

Although estimates vary based on the model used, about 1 million people are expected to need ventilatory support. However, in addition to infrastructural shortcomings, trained persons to care for these patients are lacking. Approximately 48% of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, and there are only 28,808 intensivists as per 2015 AHA data. In order to increase the amount of skilled manpower needed to staff ICUs, a model from the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Fundamental Disaster Management Program can be adopted. This involves an intensivist overseeing four different teams, with each team caring for 24 patients. Each team is led by a non-ICU physician or an ICU advanced practice provider (APP) who in turn cares for the patient with respiratory therapists, pharmacists, ICU nurses, and other non-ICU health professionals.

It is essential that infrastructure and human power be augmented and optimized, as well as contingency plans, including triage based on ethical and legal considerations, put in place if demand overwhelms capacity.

Lack of PPE and fear among health care staff

There have been widespread reports in the media, and several anecdotal reports, about severe shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), and as a result, an increase in fear and anxiety among frontline health care workers.

In addition, there also have been reports about hospital administrators disciplining medical and nursing staff for voicing their concerns about PPE shortages to the general public and the media. This likely stems from the narrow “optics” and public relations concerns of health care facilities.

It is evident that the size and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic was grossly underestimated, and preparations were inadequate. But according to past surveys of health care workers, a good number of them believe that medical and nursing staff have a duty to deliver care to sick people even if it exposes them to personal danger.

Given the special skills and privileges that health care professionals possess, they do have a moral and ethical responsibility to take care of sick patients even if a danger to themselves exists. However, society also has a responsibility to provide for the safety of these health care workers by supplying them with appropriate safety gear. Given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic, it is obvious that federal and state governments, public health officials, and hospital administrators (along with health care professionals) are still learning how to appropriately respond to the challenge.

It would be reasonable and appropriate for everyone concerned to understand and acknowledge that there is a shortage of PPE, and while arranging for this to be replenished, undertake and implement measures that maximize the safety of all health care workers. An open forum, mutually agreed-upon policy and procedures, along with mechanisms to address concerns should be formulated.

In addition, health care workers who test positive for COVID-19 can be a source of infection for other health care workers and non-infected patients. Therefore, health care workers have the responsibility of reporting their symptoms, the right to have themselves tested, and they must follow agreed-upon procedures that would limit their ability to infect other people, including mandated absenteeism from work. Every individual has a right to safety at the workplace and this right cannot be compromised, as otherwise this will lead to a suboptimal response to the pandemic. The government, hospital administrators, and health care workers will need to come together and work cohesively.

Ethical issues surrounding resource allocation

At the time of hospital admission, any suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient should have his or her wishes recorded with the admitting team regarding the goals of care and code status. During any critical illness, goals evolve depending on discussions, reflections of the patient with family, and clinical response to therapy. A patient who does not want any kind of life support obviously should not be offered an ICU level of care.

On the other hand, in the event of resources becoming overwhelmed by demand as can be expected during this pandemic, careful ethical considerations will need to be applied.

A carefully crafted transparent ethical framework, with a clear understanding of the decision-making process, that involves all stakeholders – including government entities, public health officials, health care workers, ethics specialists, and members of the community – is essential. Ideally, allocation of resources should be made according to a well-written plan, by a triage team that can include a nontreating physician, bioethicists, legal personnel, and religious representatives. It should not be left to the front-line treating physician, who is unlikely to be trained to make these decisions and who has an ethical responsibility to advocate for the patient under his care.

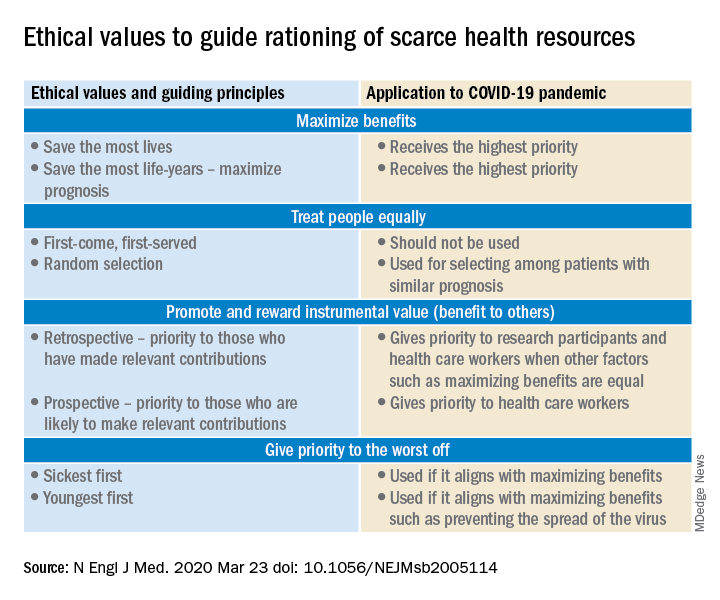

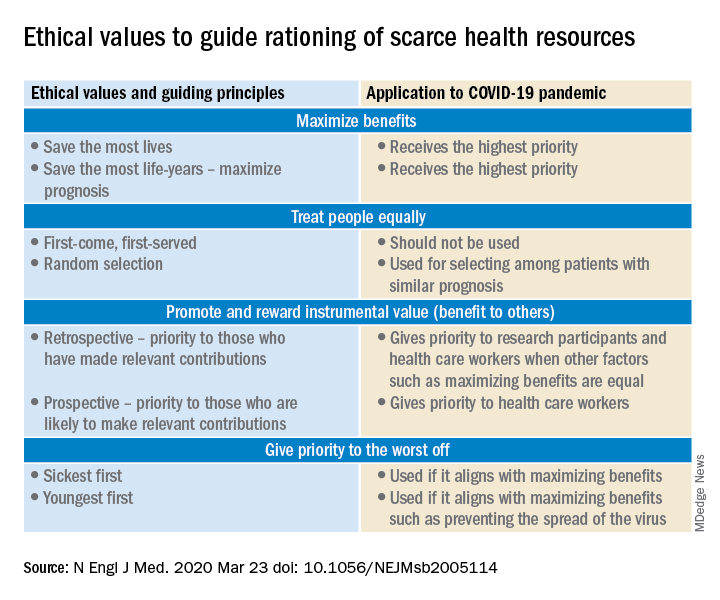

Ethical principles that deserve consideration

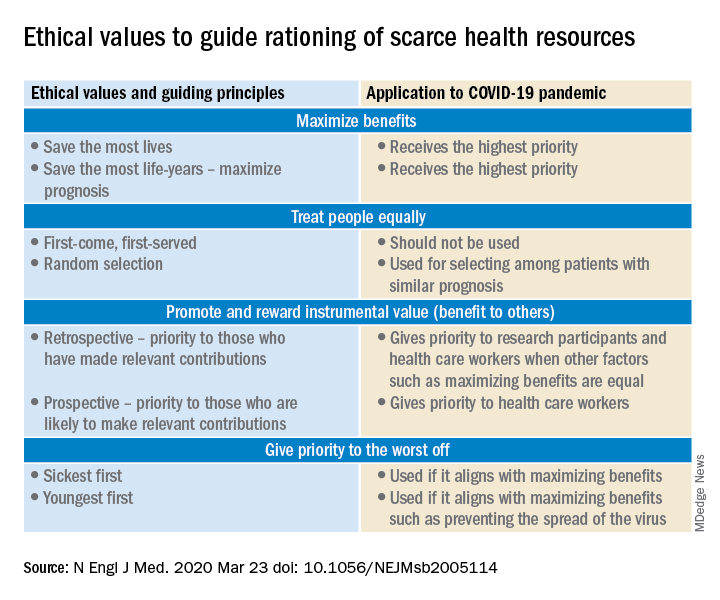

The “principle of utility” provides the maximum possible benefit to the maximum number of people. It should not only save the greatest number of lives but also maximize improvements in individuals’ posttreatment length of life.

The “principle of equity” requires that resources are allocated on a nondiscriminatory basis with a fair distribution of benefits and burdens. When conflicts arise between these two principles, a balanced approach likely will help when handled with a transparent decision-making process, with decisions to be applied consistently. Most experts would agree on not only saving more lives but also in preserving more years of life.

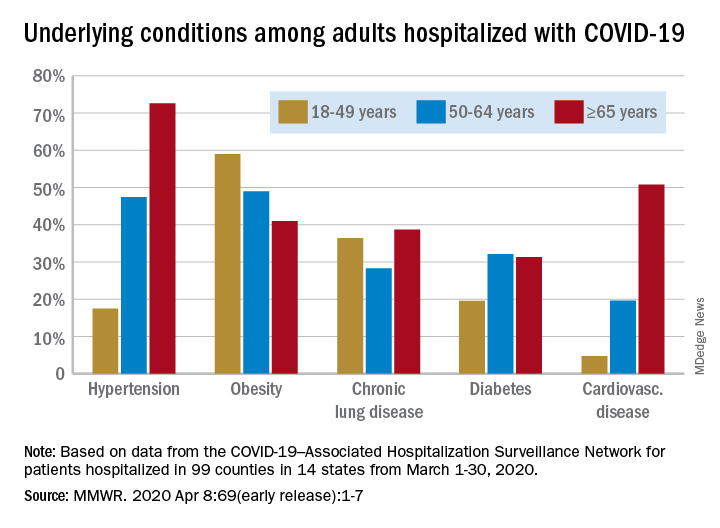

The distribution of medical resources should not be based on age or disability. Frailty and functional status are important considerations; however, priority is to be given to sicker patients who have lesser comorbidities and are also likely to survive longer. This could entail that younger, healthier patients will access scarce resources based on the principle of maximizing benefits.

Another consideration is “preservation of functioning of the society.” Those individuals who are important for providing important public services, health care services, and the functioning of other key aspects of society can be considered for prioritization of resources. While this may not satisfy the classic utilitarian principle of doing maximum good to the maximum number of people, it will help to continue augmenting the fight against the pandemic because of the critical role that such individuals play.

For patients with a similar prognosis, the principle of equality comes into play, and distribution should be done by way of random allocation, like a lottery. Distribution based on the principle of “first come, first served” is unlikely to be a fair process, as it would likely discriminate against patients based on their ability to access care.

Care should also be taken not to discriminate among people who have COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 health conditions that require medical care. Distribution should never be done based on an individual’s political influence, celebrity, or financial status, as occurred in the early days of the pandemic regarding access to testing.

Resuscitation or not?

Should a COVID-19 positive patient be offered CPR in case of cardiac arrest? The concern is that CPR is a high-level aerosolizing procedure and PPE is in short supply with the worsening of the pandemic. This will depend more on local policies and resource availability, along with goals of care that have to be determined at the time of admission and subsequent conversations.

The American Hospital Association has issued a general guideline and as more data become available, we can have more informed discussions with patients and families. At this point, all due precautions that prevent the infection of health care personnel are applicable.

Ethical considerations often do not have answers that are a universal fit, and the challenge is always to promote the best interest of the patient with a balance of judiciously utilizing scarce community resources.

Although many states have had discussions and some even have written policies, they have never been implemented. The organization and application of a judicious ethical “crisis level of care” is extremely challenging and likely to test the foundation and fabric of the society.

Dr. Jain is senior associate consultant, hospital & critical care medicine, at Mayo Clinic in Mankato, Minn. He is a board-certified internal medicine, pulmonary, and critical care physician, and has special interests in rural medicine and ethical issues involving critical care medicine. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of keystone infectious diseases/HIV in Chambersburg and is currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro Hospitals, all in Pennsylvania. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Sources

1. United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. SCCM Blog.

2. Intensive care medicine: Triage in case of bottlenecks. l

3. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 Outbreak.

4. Emanuel EJ et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020 Mar 23.doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

5. Devnani M et al. Planning and response to the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: Ethics, equity and justice. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Oct-Dec;8(4):237-40.

6. Alexander C and Wynia M. Ready and willing? Physicians’ sense of preparedness for bioterrorism. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):189-97.

7. Damery S et al. Healthcare workers’ perceptions of the duty to work during an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2010 Jan;36(1):12-8.

COVID-19 has been a watershed event in medical history of epic proportions. With this fast-spreading pandemic stretching resources at health care institutions, practical considerations for management of a disease about which we are still learning has been a huge challenge.

Although many guidelines have been made available by medical societies and experts worldwide, there appear to be very few which throw light on management in a resource-poor setup. The hospitalist, as a front-line provider, is likely expected to lead the planning and management of resources in order to deliver appropriate care.

As per American Hospital Association data, there are 2,704 community hospitals that can deliver ICU care in the United States. There are 534,964 acute care beds with 96,596 ICU beds. Additionally, there are 25,157 step-down beds and 1,183 burn unit beds. Of the 2,704 hospitals, 74% are in metropolitan areas (> 50,000 population), 17% (464) are in micropolitan areas (10,000-49,999 population), and the remaining 9% (244) are in rural areas. Only 7% (36,453) of hospital beds and 5% (4715) of ICU beds are in micropolitan areas. Two percent of acute care hospital beds and 1% of ICU beds are in rural areas. Although the US has the highest per capita number of ICU beds in the world, this may not be sufficient as these are concentrated in highly populated metropolitan areas.

Infrastructure and human power resource augmentation will be important. Infrastructure can be ramped up by:

- Canceling elective procedures

- Using the operating room and perioperative room ventilators and beds

- Servicing and using older functioning hospitals, medical wards, and ventilators.

As ventilators are expected to be in short supply, while far from ideal, other resources may include using ventilators from the Strategic National Stockpile, renting from vendors, and using state-owned stockpiles. Use of non-invasive ventilators, such as CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), BiPAP (bi-level positive airway pressure), and HFNC (high-flow nasal cannula) may be considered in addition to full-featured ventilators. Rapidly manufacturing new ventilators with government direction is also being undertaken.

Although estimates vary based on the model used, about 1 million people are expected to need ventilatory support. However, in addition to infrastructural shortcomings, trained persons to care for these patients are lacking. Approximately 48% of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, and there are only 28,808 intensivists as per 2015 AHA data. In order to increase the amount of skilled manpower needed to staff ICUs, a model from the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Fundamental Disaster Management Program can be adopted. This involves an intensivist overseeing four different teams, with each team caring for 24 patients. Each team is led by a non-ICU physician or an ICU advanced practice provider (APP) who in turn cares for the patient with respiratory therapists, pharmacists, ICU nurses, and other non-ICU health professionals.

It is essential that infrastructure and human power be augmented and optimized, as well as contingency plans, including triage based on ethical and legal considerations, put in place if demand overwhelms capacity.

Lack of PPE and fear among health care staff

There have been widespread reports in the media, and several anecdotal reports, about severe shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), and as a result, an increase in fear and anxiety among frontline health care workers.

In addition, there also have been reports about hospital administrators disciplining medical and nursing staff for voicing their concerns about PPE shortages to the general public and the media. This likely stems from the narrow “optics” and public relations concerns of health care facilities.

It is evident that the size and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic was grossly underestimated, and preparations were inadequate. But according to past surveys of health care workers, a good number of them believe that medical and nursing staff have a duty to deliver care to sick people even if it exposes them to personal danger.

Given the special skills and privileges that health care professionals possess, they do have a moral and ethical responsibility to take care of sick patients even if a danger to themselves exists. However, society also has a responsibility to provide for the safety of these health care workers by supplying them with appropriate safety gear. Given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic, it is obvious that federal and state governments, public health officials, and hospital administrators (along with health care professionals) are still learning how to appropriately respond to the challenge.

It would be reasonable and appropriate for everyone concerned to understand and acknowledge that there is a shortage of PPE, and while arranging for this to be replenished, undertake and implement measures that maximize the safety of all health care workers. An open forum, mutually agreed-upon policy and procedures, along with mechanisms to address concerns should be formulated.

In addition, health care workers who test positive for COVID-19 can be a source of infection for other health care workers and non-infected patients. Therefore, health care workers have the responsibility of reporting their symptoms, the right to have themselves tested, and they must follow agreed-upon procedures that would limit their ability to infect other people, including mandated absenteeism from work. Every individual has a right to safety at the workplace and this right cannot be compromised, as otherwise this will lead to a suboptimal response to the pandemic. The government, hospital administrators, and health care workers will need to come together and work cohesively.

Ethical issues surrounding resource allocation

At the time of hospital admission, any suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient should have his or her wishes recorded with the admitting team regarding the goals of care and code status. During any critical illness, goals evolve depending on discussions, reflections of the patient with family, and clinical response to therapy. A patient who does not want any kind of life support obviously should not be offered an ICU level of care.

On the other hand, in the event of resources becoming overwhelmed by demand as can be expected during this pandemic, careful ethical considerations will need to be applied.

A carefully crafted transparent ethical framework, with a clear understanding of the decision-making process, that involves all stakeholders – including government entities, public health officials, health care workers, ethics specialists, and members of the community – is essential. Ideally, allocation of resources should be made according to a well-written plan, by a triage team that can include a nontreating physician, bioethicists, legal personnel, and religious representatives. It should not be left to the front-line treating physician, who is unlikely to be trained to make these decisions and who has an ethical responsibility to advocate for the patient under his care.

Ethical principles that deserve consideration

The “principle of utility” provides the maximum possible benefit to the maximum number of people. It should not only save the greatest number of lives but also maximize improvements in individuals’ posttreatment length of life.

The “principle of equity” requires that resources are allocated on a nondiscriminatory basis with a fair distribution of benefits and burdens. When conflicts arise between these two principles, a balanced approach likely will help when handled with a transparent decision-making process, with decisions to be applied consistently. Most experts would agree on not only saving more lives but also in preserving more years of life.

The distribution of medical resources should not be based on age or disability. Frailty and functional status are important considerations; however, priority is to be given to sicker patients who have lesser comorbidities and are also likely to survive longer. This could entail that younger, healthier patients will access scarce resources based on the principle of maximizing benefits.

Another consideration is “preservation of functioning of the society.” Those individuals who are important for providing important public services, health care services, and the functioning of other key aspects of society can be considered for prioritization of resources. While this may not satisfy the classic utilitarian principle of doing maximum good to the maximum number of people, it will help to continue augmenting the fight against the pandemic because of the critical role that such individuals play.

For patients with a similar prognosis, the principle of equality comes into play, and distribution should be done by way of random allocation, like a lottery. Distribution based on the principle of “first come, first served” is unlikely to be a fair process, as it would likely discriminate against patients based on their ability to access care.

Care should also be taken not to discriminate among people who have COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 health conditions that require medical care. Distribution should never be done based on an individual’s political influence, celebrity, or financial status, as occurred in the early days of the pandemic regarding access to testing.

Resuscitation or not?

Should a COVID-19 positive patient be offered CPR in case of cardiac arrest? The concern is that CPR is a high-level aerosolizing procedure and PPE is in short supply with the worsening of the pandemic. This will depend more on local policies and resource availability, along with goals of care that have to be determined at the time of admission and subsequent conversations.

The American Hospital Association has issued a general guideline and as more data become available, we can have more informed discussions with patients and families. At this point, all due precautions that prevent the infection of health care personnel are applicable.

Ethical considerations often do not have answers that are a universal fit, and the challenge is always to promote the best interest of the patient with a balance of judiciously utilizing scarce community resources.

Although many states have had discussions and some even have written policies, they have never been implemented. The organization and application of a judicious ethical “crisis level of care” is extremely challenging and likely to test the foundation and fabric of the society.

Dr. Jain is senior associate consultant, hospital & critical care medicine, at Mayo Clinic in Mankato, Minn. He is a board-certified internal medicine, pulmonary, and critical care physician, and has special interests in rural medicine and ethical issues involving critical care medicine. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of keystone infectious diseases/HIV in Chambersburg and is currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro Hospitals, all in Pennsylvania. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Sources

1. United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. SCCM Blog.

2. Intensive care medicine: Triage in case of bottlenecks. l

3. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 Outbreak.

4. Emanuel EJ et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020 Mar 23.doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

5. Devnani M et al. Planning and response to the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: Ethics, equity and justice. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Oct-Dec;8(4):237-40.

6. Alexander C and Wynia M. Ready and willing? Physicians’ sense of preparedness for bioterrorism. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):189-97.

7. Damery S et al. Healthcare workers’ perceptions of the duty to work during an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2010 Jan;36(1):12-8.

COVID-19 has been a watershed event in medical history of epic proportions. With this fast-spreading pandemic stretching resources at health care institutions, practical considerations for management of a disease about which we are still learning has been a huge challenge.

Although many guidelines have been made available by medical societies and experts worldwide, there appear to be very few which throw light on management in a resource-poor setup. The hospitalist, as a front-line provider, is likely expected to lead the planning and management of resources in order to deliver appropriate care.

As per American Hospital Association data, there are 2,704 community hospitals that can deliver ICU care in the United States. There are 534,964 acute care beds with 96,596 ICU beds. Additionally, there are 25,157 step-down beds and 1,183 burn unit beds. Of the 2,704 hospitals, 74% are in metropolitan areas (> 50,000 population), 17% (464) are in micropolitan areas (10,000-49,999 population), and the remaining 9% (244) are in rural areas. Only 7% (36,453) of hospital beds and 5% (4715) of ICU beds are in micropolitan areas. Two percent of acute care hospital beds and 1% of ICU beds are in rural areas. Although the US has the highest per capita number of ICU beds in the world, this may not be sufficient as these are concentrated in highly populated metropolitan areas.

Infrastructure and human power resource augmentation will be important. Infrastructure can be ramped up by:

- Canceling elective procedures

- Using the operating room and perioperative room ventilators and beds

- Servicing and using older functioning hospitals, medical wards, and ventilators.

As ventilators are expected to be in short supply, while far from ideal, other resources may include using ventilators from the Strategic National Stockpile, renting from vendors, and using state-owned stockpiles. Use of non-invasive ventilators, such as CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), BiPAP (bi-level positive airway pressure), and HFNC (high-flow nasal cannula) may be considered in addition to full-featured ventilators. Rapidly manufacturing new ventilators with government direction is also being undertaken.

Although estimates vary based on the model used, about 1 million people are expected to need ventilatory support. However, in addition to infrastructural shortcomings, trained persons to care for these patients are lacking. Approximately 48% of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, and there are only 28,808 intensivists as per 2015 AHA data. In order to increase the amount of skilled manpower needed to staff ICUs, a model from the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Fundamental Disaster Management Program can be adopted. This involves an intensivist overseeing four different teams, with each team caring for 24 patients. Each team is led by a non-ICU physician or an ICU advanced practice provider (APP) who in turn cares for the patient with respiratory therapists, pharmacists, ICU nurses, and other non-ICU health professionals.

It is essential that infrastructure and human power be augmented and optimized, as well as contingency plans, including triage based on ethical and legal considerations, put in place if demand overwhelms capacity.

Lack of PPE and fear among health care staff

There have been widespread reports in the media, and several anecdotal reports, about severe shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), and as a result, an increase in fear and anxiety among frontline health care workers.

In addition, there also have been reports about hospital administrators disciplining medical and nursing staff for voicing their concerns about PPE shortages to the general public and the media. This likely stems from the narrow “optics” and public relations concerns of health care facilities.

It is evident that the size and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic was grossly underestimated, and preparations were inadequate. But according to past surveys of health care workers, a good number of them believe that medical and nursing staff have a duty to deliver care to sick people even if it exposes them to personal danger.

Given the special skills and privileges that health care professionals possess, they do have a moral and ethical responsibility to take care of sick patients even if a danger to themselves exists. However, society also has a responsibility to provide for the safety of these health care workers by supplying them with appropriate safety gear. Given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic, it is obvious that federal and state governments, public health officials, and hospital administrators (along with health care professionals) are still learning how to appropriately respond to the challenge.

It would be reasonable and appropriate for everyone concerned to understand and acknowledge that there is a shortage of PPE, and while arranging for this to be replenished, undertake and implement measures that maximize the safety of all health care workers. An open forum, mutually agreed-upon policy and procedures, along with mechanisms to address concerns should be formulated.

In addition, health care workers who test positive for COVID-19 can be a source of infection for other health care workers and non-infected patients. Therefore, health care workers have the responsibility of reporting their symptoms, the right to have themselves tested, and they must follow agreed-upon procedures that would limit their ability to infect other people, including mandated absenteeism from work. Every individual has a right to safety at the workplace and this right cannot be compromised, as otherwise this will lead to a suboptimal response to the pandemic. The government, hospital administrators, and health care workers will need to come together and work cohesively.

Ethical issues surrounding resource allocation

At the time of hospital admission, any suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient should have his or her wishes recorded with the admitting team regarding the goals of care and code status. During any critical illness, goals evolve depending on discussions, reflections of the patient with family, and clinical response to therapy. A patient who does not want any kind of life support obviously should not be offered an ICU level of care.

On the other hand, in the event of resources becoming overwhelmed by demand as can be expected during this pandemic, careful ethical considerations will need to be applied.

A carefully crafted transparent ethical framework, with a clear understanding of the decision-making process, that involves all stakeholders – including government entities, public health officials, health care workers, ethics specialists, and members of the community – is essential. Ideally, allocation of resources should be made according to a well-written plan, by a triage team that can include a nontreating physician, bioethicists, legal personnel, and religious representatives. It should not be left to the front-line treating physician, who is unlikely to be trained to make these decisions and who has an ethical responsibility to advocate for the patient under his care.

Ethical principles that deserve consideration

The “principle of utility” provides the maximum possible benefit to the maximum number of people. It should not only save the greatest number of lives but also maximize improvements in individuals’ posttreatment length of life.

The “principle of equity” requires that resources are allocated on a nondiscriminatory basis with a fair distribution of benefits and burdens. When conflicts arise between these two principles, a balanced approach likely will help when handled with a transparent decision-making process, with decisions to be applied consistently. Most experts would agree on not only saving more lives but also in preserving more years of life.

The distribution of medical resources should not be based on age or disability. Frailty and functional status are important considerations; however, priority is to be given to sicker patients who have lesser comorbidities and are also likely to survive longer. This could entail that younger, healthier patients will access scarce resources based on the principle of maximizing benefits.

Another consideration is “preservation of functioning of the society.” Those individuals who are important for providing important public services, health care services, and the functioning of other key aspects of society can be considered for prioritization of resources. While this may not satisfy the classic utilitarian principle of doing maximum good to the maximum number of people, it will help to continue augmenting the fight against the pandemic because of the critical role that such individuals play.

For patients with a similar prognosis, the principle of equality comes into play, and distribution should be done by way of random allocation, like a lottery. Distribution based on the principle of “first come, first served” is unlikely to be a fair process, as it would likely discriminate against patients based on their ability to access care.

Care should also be taken not to discriminate among people who have COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 health conditions that require medical care. Distribution should never be done based on an individual’s political influence, celebrity, or financial status, as occurred in the early days of the pandemic regarding access to testing.

Resuscitation or not?

Should a COVID-19 positive patient be offered CPR in case of cardiac arrest? The concern is that CPR is a high-level aerosolizing procedure and PPE is in short supply with the worsening of the pandemic. This will depend more on local policies and resource availability, along with goals of care that have to be determined at the time of admission and subsequent conversations.

The American Hospital Association has issued a general guideline and as more data become available, we can have more informed discussions with patients and families. At this point, all due precautions that prevent the infection of health care personnel are applicable.

Ethical considerations often do not have answers that are a universal fit, and the challenge is always to promote the best interest of the patient with a balance of judiciously utilizing scarce community resources.

Although many states have had discussions and some even have written policies, they have never been implemented. The organization and application of a judicious ethical “crisis level of care” is extremely challenging and likely to test the foundation and fabric of the society.

Dr. Jain is senior associate consultant, hospital & critical care medicine, at Mayo Clinic in Mankato, Minn. He is a board-certified internal medicine, pulmonary, and critical care physician, and has special interests in rural medicine and ethical issues involving critical care medicine. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of keystone infectious diseases/HIV in Chambersburg and is currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro Hospitals, all in Pennsylvania. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Sources

1. United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. SCCM Blog.

2. Intensive care medicine: Triage in case of bottlenecks. l

3. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 Outbreak.

4. Emanuel EJ et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020 Mar 23.doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

5. Devnani M et al. Planning and response to the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: Ethics, equity and justice. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Oct-Dec;8(4):237-40.

6. Alexander C and Wynia M. Ready and willing? Physicians’ sense of preparedness for bioterrorism. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):189-97.

7. Damery S et al. Healthcare workers’ perceptions of the duty to work during an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2010 Jan;36(1):12-8.

COVID 19: Confessions of an outpatient psychiatrist during the pandemic

It seems that some glitches would be inevitable. With a sudden shift to videoconferencing in private psychiatric practices, there were bound to be issues with both technology and privacy. One friend told me of such a glitch on the very first day she started telemental health: She was meeting with a patient who was sitting at her kitchen table. Unbeknownst to the patient, her husband walked into the kitchen behind her, fully naked, to get something from the refrigerator. “There was a full moon shot!” my friend said, initially quite shocked, and then eventually amused. As we all cope with a national tragedy and the total upheaval to our personal and professional lives, the stories just keep coming.

I left work on Friday, March 13, with plans to return on the following Monday to see patients. I had no idea that, by Sunday evening, I would be persuaded that for the safety of all I would need to shut down my real-life psychiatric practice and switch to a videoconferencing venue. I, along with many psychiatrists in Maryland, made this decision after Amy Huberman, MD, posted the following on the Maryland Psychiatric Society (MPS) listserv on Sunday, March 15:

“I want to make a case for starting video sessions with all your patients NOW. There is increasing evidence that the spread of coronavirus is driven primarily by asymptomatic or mildly ill people infected with the virus. Because of this, it’s not good enough to tell your patients not to come in if they have symptoms, or for you not to come into work if you have no symptoms. Even after I sent out a letter two weeks ago warning people not to come in if they had symptoms or had potentially come in contact with someone with COVID-19, several patients with coughs still came to my office, as well as several people who had just been on trips to New York City.

If we want to help slow the spread of this illness so that our health system has a better chance of being able to offer ventilators to the people who need them, we must limit all contacts as much as possible – even of asymptomatic people, given the emerging data.

I am planning to send out a message to all my patients today that they should do the same. Without the president or the media giving clear advice to people about what to do, it’s our job as physicians to do it.”

By that night, I had set up a home office with a blank wall behind me, windows in front of me, and books propping my computer at a height that would not have my patients looking up my nose. For the first time in over 20 years, I dusted my son’s Little League trophies, moved them and a 40,000 baseball card collection against the wall, carried a desk, chair, rug, houseplant, and a small Buddha into a room in which I would have some privacy, and my telepsychiatry practice found a home.

After some research, I registered for a free site called Doxy.me because it was HIPAA compliant and did not require patients to download an application; anyone with a camera on any Internet-enabled phone, computer, or tablet, could click on a link and enter my virtual waiting room. I soon discovered that images on the Doxy.me site are sometimes grainy and sometimes freeze up; in some sessions, we ended up switching to FaceTime, and as government mandates for HIPAA compliance relaxed, I offered to meet on any site that my patients might be comfortable with: if not Doxy.me (which remains my starting place for most sessions), Facetime, Skype, Zoom, or Whatsapp. I have not offered Bluejeans, Google Hangouts, or WebEx, and no one has requested those applications. I keep the phone next to the computer, and some sessions include a few minutes of tech support as I help patients (or they help me) navigate the various sites. In a few sessions, we could not get the audio to work and we used video on one venue while we talked on the phone. I haven’t figured out if the variations in the quality of the connection has to do with my Comcast connection, the fact that these websites are overloaded with users, or that my household now consists of three people, two large monitors, three laptops, two tablets, three cell phone lines (not to mention one dog and a transplanted cat), all going at the same time. The pets do not require any bandwidth, but all the people are talking to screens throughout the workday.

As my colleagues embarked on the same journey, the listserv questions and comments came quickly. What were the best platforms? Was it a good thing or a bad thing to suddenly be in people’s homes? Some felt the extraneous background to be helpful, others found it distracting and intrusive.

How do these sessions get coded for the purpose of billing? There was a tremendous amount of confusion over that, with the initial verdict being that Medicare wanted the place of service changed to “02” and that private insurers want one of two modifiers, and it was anyone’s guess which company wanted which modifier. Then there was the concern that Medicare was paying 25% less, until the MPS staff clarified that full fees would be paid, but the place of service should be filled in as “11” – not “02” – as with regular office visits, and the modifier “95” should be added on the Health Care Finance Administration claim form. We were left to wait and see what gets reimbursed and for what fees.

Could new patients be seen by videoconferencing? Could patients from other states be seen this way if the psychiatrist was not licensed in the state where the patient was calling from? One psychiatrist reported he had a patient in an adjacent state drive over the border into Maryland, but the patient brought her mother and the evaluation included unwanted input from the mom as the session consisted of the patient and her mother yelling at both each other in the car and at the psychiatrist on the screen!

Psychiatrists on the listserv began to comment that treatment sessions were intense and exhausting. I feel the literal face-to-face contact of another person’s head just inches from my own, with full eye contact, often gets to be a lot. No one asks why I’ve moved a trinket (ah, there are no trinkets) or gazes off around the room. I sometimes sit for long periods of time as I don’t even stand to see the patients to the door. Other patients move about or bounce their devices on their laps, and my stomach starts to feel queasy until I ask to have the device adjusted. In some sessions, I find I’m talking to partial heads, or that computer icons cover the patient’s mouth.

Being in people’s lives via screen has been interesting. Unlike my colleague, I have not had any streaking spouses, but I’ve greeted a few family members – often those serving as technical support – and I’ve toured part of a farm, met dogs, guinea pigs, and even a goat. I’ve made brief daily “visits” to a frightened patient in isolation on a COVID hospital unit and had the joy of celebrating the discharge to home. It’s odd to be in a bedroom with a patient, even virtually, and it is interesting to note where they choose to hold their sessions; I’ve had several patients hold sessions from their cars. Seeing my own image in the corner of the screen is also a bit distracting, and in one session, as I saw my own reaction, my patient said, “I knew you were going to make that face!”

The pandemic has usurped most of the activities of all of our lives, and without social interactions, travel, and work in the usual way, life does not hold its usual richness. In a few cases, I have ended the session after half the time as the patient insisted there was nothing to talk about. Many talk about the medical problems they can’t be seen for, what they are doing to keep safe (or not), how they are washing down their groceries, and who they are meeting with by Zoom. Of those who were terribly anxious before, some feel oddly calmer – the world has ramped up to meet their level of anxiety and they feel vindicated. No one thinks they are odd for worrying about germs on door knobs or elevator buttons. What were once neurotic fears are now our real-life reality. Others have been triggered by a paralyzing fear, often with panic attacks, and these sessions are certainly challenging as I figure out which medications will best help, while responding to requests for reassurance. And there is the troublesome aspect of trying to care for others who are fearful while living with the reality that these fears are not extraneous to our own lives: We, too, are scared for ourselves and our families.

For some people, stay-at-home mandates have been easier than for others. People who are naturally introverted, or those with social anxiety, have told me they find this time at home to be a relief. They no longer feel pressured to go out; there is permission to be alone, to read, or watch Netflix. No one is pressuring them to go to parties or look for a Tinder date. For others, the isolation and loneliness have been devastating, causing a range of emotions from being “stir crazy,” to triggering episodes of major depression and severe anxiety.

Health care workers in therapy talk about their fears of being contaminated with coronavirus, about the exposures they’ve had, their fears of bringing the virus home to family, and about the anger – sometimes rage – that their employers are not doing more to protect them.

Few people these past weeks are looking for insight into their patterns of behavior and emotion. Most of life has come to be about survival and not about personal striving. Students who are driven to excel are disappointed to have their scholastic worlds have switched to pass/fail. And for those struggling with milder forms of depression and anxiety, both the patients and I have all been a bit perplexed by losing the usual measures of what feelings are normal in a tragic world and we no longer use socializing as the hallmark that heralds a return to normalcy after a period of withdrawal.

In some aspects, it is not all been bad. I’ve enjoyed watching my neighbors walk by with their dogs through the window behind my computer screen and I’ve felt part of the daily evolution as the cherry tree outside that same window turns from dead brown wood to vibrant pink blossoms. I like the flexibility of my schedule and the sensation I always carry of being rushed has quelled. I take more walks and spend more time with the family members who are held captive with me. The dog, who no longer is left alone for hours each day, is certainly a winner.

Some of my colleagues tell me they are overwhelmed – patients they have not seen for years have returned, people are asking for more frequent sessions, and they are suddenly trying to work at home while homeschooling children. I have had only a few of those requests for crisis care, while new referrals are much quieter than normal. Some of my patients have even said that they simply aren’t comfortable meeting this way and they will see me at the other end of the pandemic. A few people I would have expected to hear from I have not, and I fear that those who have lost their jobs may avoiding the cost of treatment – this group I will reach out to in the coming weeks. A little extra time, however, has given me the opportunity to join the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health team. And my first attempt at teaching a resident seminar by Zoom has gone well.

For some in the medical field, this has been a horrible and traumatic time; they are worked to exhaustion, and surrounded by distress, death, and personal fear with every shift. For others, life has come to a standstill as the elective procedures that fill their days have virtually stopped. For outpatient psychiatry, it’s been a bit of an in-between, we may feel an odd mix of relevant and useless all at the same time, as our services are appreciated by our patients, but as actual soldiers caring for the ill COVID patients, we are leaving that to our colleagues in the EDs, COVID units, and ICUs. As a physician who has not treated a patient in an ICU for decades, I wish I had something more concrete to contribute to the effort, and at the same time, I’m relieved that I don’t.

And what about the patients? How are they doing with remote psychiatry? Some are clearly flustered or frustrated by the technology issues. Other times sessions go smoothly, and the fact that we are talking through screens gets forgotten. Some like the convenience of not having to drive a far distance and no one misses my crowded parking lot.

Kristen, another doctor’s patient in Illinois, commented: “I appreciate the continuity in care, especially if the alternative is delaying appointments. I think that’s most important. The interaction helps manage added anxiety from isolating as well. I don’t think it diminishes the care I receive; it makes me feel that my doctor is still accessible. One other point, since I have had both telemedicine and in-person appointments with my current psychiatrist, is that during in-person meetings, he is usually on his computer and rarely looks at me or makes eye contact. In virtual meetings, I feel he is much more engaged with me.”

In normal times, I spend a good deal of time encouraging patients to work on building their relationships and community – these connections lead people to healthy and fulfilling lives – and now we talk about how to best be socially distant. We see each other as vectors of disease and to greet a friend with a handshake, much less a hug, would be unthinkable. Will our collective psyches ever recover? For those of us who will survive, that remains to be seen. In the meantime, perhaps we are all being forced to be more flexible and innovative.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

It seems that some glitches would be inevitable. With a sudden shift to videoconferencing in private psychiatric practices, there were bound to be issues with both technology and privacy. One friend told me of such a glitch on the very first day she started telemental health: She was meeting with a patient who was sitting at her kitchen table. Unbeknownst to the patient, her husband walked into the kitchen behind her, fully naked, to get something from the refrigerator. “There was a full moon shot!” my friend said, initially quite shocked, and then eventually amused. As we all cope with a national tragedy and the total upheaval to our personal and professional lives, the stories just keep coming.

I left work on Friday, March 13, with plans to return on the following Monday to see patients. I had no idea that, by Sunday evening, I would be persuaded that for the safety of all I would need to shut down my real-life psychiatric practice and switch to a videoconferencing venue. I, along with many psychiatrists in Maryland, made this decision after Amy Huberman, MD, posted the following on the Maryland Psychiatric Society (MPS) listserv on Sunday, March 15:

“I want to make a case for starting video sessions with all your patients NOW. There is increasing evidence that the spread of coronavirus is driven primarily by asymptomatic or mildly ill people infected with the virus. Because of this, it’s not good enough to tell your patients not to come in if they have symptoms, or for you not to come into work if you have no symptoms. Even after I sent out a letter two weeks ago warning people not to come in if they had symptoms or had potentially come in contact with someone with COVID-19, several patients with coughs still came to my office, as well as several people who had just been on trips to New York City.

If we want to help slow the spread of this illness so that our health system has a better chance of being able to offer ventilators to the people who need them, we must limit all contacts as much as possible – even of asymptomatic people, given the emerging data.

I am planning to send out a message to all my patients today that they should do the same. Without the president or the media giving clear advice to people about what to do, it’s our job as physicians to do it.”

By that night, I had set up a home office with a blank wall behind me, windows in front of me, and books propping my computer at a height that would not have my patients looking up my nose. For the first time in over 20 years, I dusted my son’s Little League trophies, moved them and a 40,000 baseball card collection against the wall, carried a desk, chair, rug, houseplant, and a small Buddha into a room in which I would have some privacy, and my telepsychiatry practice found a home.

After some research, I registered for a free site called Doxy.me because it was HIPAA compliant and did not require patients to download an application; anyone with a camera on any Internet-enabled phone, computer, or tablet, could click on a link and enter my virtual waiting room. I soon discovered that images on the Doxy.me site are sometimes grainy and sometimes freeze up; in some sessions, we ended up switching to FaceTime, and as government mandates for HIPAA compliance relaxed, I offered to meet on any site that my patients might be comfortable with: if not Doxy.me (which remains my starting place for most sessions), Facetime, Skype, Zoom, or Whatsapp. I have not offered Bluejeans, Google Hangouts, or WebEx, and no one has requested those applications. I keep the phone next to the computer, and some sessions include a few minutes of tech support as I help patients (or they help me) navigate the various sites. In a few sessions, we could not get the audio to work and we used video on one venue while we talked on the phone. I haven’t figured out if the variations in the quality of the connection has to do with my Comcast connection, the fact that these websites are overloaded with users, or that my household now consists of three people, two large monitors, three laptops, two tablets, three cell phone lines (not to mention one dog and a transplanted cat), all going at the same time. The pets do not require any bandwidth, but all the people are talking to screens throughout the workday.

As my colleagues embarked on the same journey, the listserv questions and comments came quickly. What were the best platforms? Was it a good thing or a bad thing to suddenly be in people’s homes? Some felt the extraneous background to be helpful, others found it distracting and intrusive.

How do these sessions get coded for the purpose of billing? There was a tremendous amount of confusion over that, with the initial verdict being that Medicare wanted the place of service changed to “02” and that private insurers want one of two modifiers, and it was anyone’s guess which company wanted which modifier. Then there was the concern that Medicare was paying 25% less, until the MPS staff clarified that full fees would be paid, but the place of service should be filled in as “11” – not “02” – as with regular office visits, and the modifier “95” should be added on the Health Care Finance Administration claim form. We were left to wait and see what gets reimbursed and for what fees.

Could new patients be seen by videoconferencing? Could patients from other states be seen this way if the psychiatrist was not licensed in the state where the patient was calling from? One psychiatrist reported he had a patient in an adjacent state drive over the border into Maryland, but the patient brought her mother and the evaluation included unwanted input from the mom as the session consisted of the patient and her mother yelling at both each other in the car and at the psychiatrist on the screen!

Psychiatrists on the listserv began to comment that treatment sessions were intense and exhausting. I feel the literal face-to-face contact of another person’s head just inches from my own, with full eye contact, often gets to be a lot. No one asks why I’ve moved a trinket (ah, there are no trinkets) or gazes off around the room. I sometimes sit for long periods of time as I don’t even stand to see the patients to the door. Other patients move about or bounce their devices on their laps, and my stomach starts to feel queasy until I ask to have the device adjusted. In some sessions, I find I’m talking to partial heads, or that computer icons cover the patient’s mouth.

Being in people’s lives via screen has been interesting. Unlike my colleague, I have not had any streaking spouses, but I’ve greeted a few family members – often those serving as technical support – and I’ve toured part of a farm, met dogs, guinea pigs, and even a goat. I’ve made brief daily “visits” to a frightened patient in isolation on a COVID hospital unit and had the joy of celebrating the discharge to home. It’s odd to be in a bedroom with a patient, even virtually, and it is interesting to note where they choose to hold their sessions; I’ve had several patients hold sessions from their cars. Seeing my own image in the corner of the screen is also a bit distracting, and in one session, as I saw my own reaction, my patient said, “I knew you were going to make that face!”

The pandemic has usurped most of the activities of all of our lives, and without social interactions, travel, and work in the usual way, life does not hold its usual richness. In a few cases, I have ended the session after half the time as the patient insisted there was nothing to talk about. Many talk about the medical problems they can’t be seen for, what they are doing to keep safe (or not), how they are washing down their groceries, and who they are meeting with by Zoom. Of those who were terribly anxious before, some feel oddly calmer – the world has ramped up to meet their level of anxiety and they feel vindicated. No one thinks they are odd for worrying about germs on door knobs or elevator buttons. What were once neurotic fears are now our real-life reality. Others have been triggered by a paralyzing fear, often with panic attacks, and these sessions are certainly challenging as I figure out which medications will best help, while responding to requests for reassurance. And there is the troublesome aspect of trying to care for others who are fearful while living with the reality that these fears are not extraneous to our own lives: We, too, are scared for ourselves and our families.

For some people, stay-at-home mandates have been easier than for others. People who are naturally introverted, or those with social anxiety, have told me they find this time at home to be a relief. They no longer feel pressured to go out; there is permission to be alone, to read, or watch Netflix. No one is pressuring them to go to parties or look for a Tinder date. For others, the isolation and loneliness have been devastating, causing a range of emotions from being “stir crazy,” to triggering episodes of major depression and severe anxiety.

Health care workers in therapy talk about their fears of being contaminated with coronavirus, about the exposures they’ve had, their fears of bringing the virus home to family, and about the anger – sometimes rage – that their employers are not doing more to protect them.

Few people these past weeks are looking for insight into their patterns of behavior and emotion. Most of life has come to be about survival and not about personal striving. Students who are driven to excel are disappointed to have their scholastic worlds have switched to pass/fail. And for those struggling with milder forms of depression and anxiety, both the patients and I have all been a bit perplexed by losing the usual measures of what feelings are normal in a tragic world and we no longer use socializing as the hallmark that heralds a return to normalcy after a period of withdrawal.

In some aspects, it is not all been bad. I’ve enjoyed watching my neighbors walk by with their dogs through the window behind my computer screen and I’ve felt part of the daily evolution as the cherry tree outside that same window turns from dead brown wood to vibrant pink blossoms. I like the flexibility of my schedule and the sensation I always carry of being rushed has quelled. I take more walks and spend more time with the family members who are held captive with me. The dog, who no longer is left alone for hours each day, is certainly a winner.

Some of my colleagues tell me they are overwhelmed – patients they have not seen for years have returned, people are asking for more frequent sessions, and they are suddenly trying to work at home while homeschooling children. I have had only a few of those requests for crisis care, while new referrals are much quieter than normal. Some of my patients have even said that they simply aren’t comfortable meeting this way and they will see me at the other end of the pandemic. A few people I would have expected to hear from I have not, and I fear that those who have lost their jobs may avoiding the cost of treatment – this group I will reach out to in the coming weeks. A little extra time, however, has given me the opportunity to join the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health team. And my first attempt at teaching a resident seminar by Zoom has gone well.

For some in the medical field, this has been a horrible and traumatic time; they are worked to exhaustion, and surrounded by distress, death, and personal fear with every shift. For others, life has come to a standstill as the elective procedures that fill their days have virtually stopped. For outpatient psychiatry, it’s been a bit of an in-between, we may feel an odd mix of relevant and useless all at the same time, as our services are appreciated by our patients, but as actual soldiers caring for the ill COVID patients, we are leaving that to our colleagues in the EDs, COVID units, and ICUs. As a physician who has not treated a patient in an ICU for decades, I wish I had something more concrete to contribute to the effort, and at the same time, I’m relieved that I don’t.

And what about the patients? How are they doing with remote psychiatry? Some are clearly flustered or frustrated by the technology issues. Other times sessions go smoothly, and the fact that we are talking through screens gets forgotten. Some like the convenience of not having to drive a far distance and no one misses my crowded parking lot.

Kristen, another doctor’s patient in Illinois, commented: “I appreciate the continuity in care, especially if the alternative is delaying appointments. I think that’s most important. The interaction helps manage added anxiety from isolating as well. I don’t think it diminishes the care I receive; it makes me feel that my doctor is still accessible. One other point, since I have had both telemedicine and in-person appointments with my current psychiatrist, is that during in-person meetings, he is usually on his computer and rarely looks at me or makes eye contact. In virtual meetings, I feel he is much more engaged with me.”

In normal times, I spend a good deal of time encouraging patients to work on building their relationships and community – these connections lead people to healthy and fulfilling lives – and now we talk about how to best be socially distant. We see each other as vectors of disease and to greet a friend with a handshake, much less a hug, would be unthinkable. Will our collective psyches ever recover? For those of us who will survive, that remains to be seen. In the meantime, perhaps we are all being forced to be more flexible and innovative.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

It seems that some glitches would be inevitable. With a sudden shift to videoconferencing in private psychiatric practices, there were bound to be issues with both technology and privacy. One friend told me of such a glitch on the very first day she started telemental health: She was meeting with a patient who was sitting at her kitchen table. Unbeknownst to the patient, her husband walked into the kitchen behind her, fully naked, to get something from the refrigerator. “There was a full moon shot!” my friend said, initially quite shocked, and then eventually amused. As we all cope with a national tragedy and the total upheaval to our personal and professional lives, the stories just keep coming.

I left work on Friday, March 13, with plans to return on the following Monday to see patients. I had no idea that, by Sunday evening, I would be persuaded that for the safety of all I would need to shut down my real-life psychiatric practice and switch to a videoconferencing venue. I, along with many psychiatrists in Maryland, made this decision after Amy Huberman, MD, posted the following on the Maryland Psychiatric Society (MPS) listserv on Sunday, March 15:

“I want to make a case for starting video sessions with all your patients NOW. There is increasing evidence that the spread of coronavirus is driven primarily by asymptomatic or mildly ill people infected with the virus. Because of this, it’s not good enough to tell your patients not to come in if they have symptoms, or for you not to come into work if you have no symptoms. Even after I sent out a letter two weeks ago warning people not to come in if they had symptoms or had potentially come in contact with someone with COVID-19, several patients with coughs still came to my office, as well as several people who had just been on trips to New York City.

If we want to help slow the spread of this illness so that our health system has a better chance of being able to offer ventilators to the people who need them, we must limit all contacts as much as possible – even of asymptomatic people, given the emerging data.

I am planning to send out a message to all my patients today that they should do the same. Without the president or the media giving clear advice to people about what to do, it’s our job as physicians to do it.”

By that night, I had set up a home office with a blank wall behind me, windows in front of me, and books propping my computer at a height that would not have my patients looking up my nose. For the first time in over 20 years, I dusted my son’s Little League trophies, moved them and a 40,000 baseball card collection against the wall, carried a desk, chair, rug, houseplant, and a small Buddha into a room in which I would have some privacy, and my telepsychiatry practice found a home.

After some research, I registered for a free site called Doxy.me because it was HIPAA compliant and did not require patients to download an application; anyone with a camera on any Internet-enabled phone, computer, or tablet, could click on a link and enter my virtual waiting room. I soon discovered that images on the Doxy.me site are sometimes grainy and sometimes freeze up; in some sessions, we ended up switching to FaceTime, and as government mandates for HIPAA compliance relaxed, I offered to meet on any site that my patients might be comfortable with: if not Doxy.me (which remains my starting place for most sessions), Facetime, Skype, Zoom, or Whatsapp. I have not offered Bluejeans, Google Hangouts, or WebEx, and no one has requested those applications. I keep the phone next to the computer, and some sessions include a few minutes of tech support as I help patients (or they help me) navigate the various sites. In a few sessions, we could not get the audio to work and we used video on one venue while we talked on the phone. I haven’t figured out if the variations in the quality of the connection has to do with my Comcast connection, the fact that these websites are overloaded with users, or that my household now consists of three people, two large monitors, three laptops, two tablets, three cell phone lines (not to mention one dog and a transplanted cat), all going at the same time. The pets do not require any bandwidth, but all the people are talking to screens throughout the workday.

As my colleagues embarked on the same journey, the listserv questions and comments came quickly. What were the best platforms? Was it a good thing or a bad thing to suddenly be in people’s homes? Some felt the extraneous background to be helpful, others found it distracting and intrusive.

How do these sessions get coded for the purpose of billing? There was a tremendous amount of confusion over that, with the initial verdict being that Medicare wanted the place of service changed to “02” and that private insurers want one of two modifiers, and it was anyone’s guess which company wanted which modifier. Then there was the concern that Medicare was paying 25% less, until the MPS staff clarified that full fees would be paid, but the place of service should be filled in as “11” – not “02” – as with regular office visits, and the modifier “95” should be added on the Health Care Finance Administration claim form. We were left to wait and see what gets reimbursed and for what fees.

Could new patients be seen by videoconferencing? Could patients from other states be seen this way if the psychiatrist was not licensed in the state where the patient was calling from? One psychiatrist reported he had a patient in an adjacent state drive over the border into Maryland, but the patient brought her mother and the evaluation included unwanted input from the mom as the session consisted of the patient and her mother yelling at both each other in the car and at the psychiatrist on the screen!

Psychiatrists on the listserv began to comment that treatment sessions were intense and exhausting. I feel the literal face-to-face contact of another person’s head just inches from my own, with full eye contact, often gets to be a lot. No one asks why I’ve moved a trinket (ah, there are no trinkets) or gazes off around the room. I sometimes sit for long periods of time as I don’t even stand to see the patients to the door. Other patients move about or bounce their devices on their laps, and my stomach starts to feel queasy until I ask to have the device adjusted. In some sessions, I find I’m talking to partial heads, or that computer icons cover the patient’s mouth.

Being in people’s lives via screen has been interesting. Unlike my colleague, I have not had any streaking spouses, but I’ve greeted a few family members – often those serving as technical support – and I’ve toured part of a farm, met dogs, guinea pigs, and even a goat. I’ve made brief daily “visits” to a frightened patient in isolation on a COVID hospital unit and had the joy of celebrating the discharge to home. It’s odd to be in a bedroom with a patient, even virtually, and it is interesting to note where they choose to hold their sessions; I’ve had several patients hold sessions from their cars. Seeing my own image in the corner of the screen is also a bit distracting, and in one session, as I saw my own reaction, my patient said, “I knew you were going to make that face!”

The pandemic has usurped most of the activities of all of our lives, and without social interactions, travel, and work in the usual way, life does not hold its usual richness. In a few cases, I have ended the session after half the time as the patient insisted there was nothing to talk about. Many talk about the medical problems they can’t be seen for, what they are doing to keep safe (or not), how they are washing down their groceries, and who they are meeting with by Zoom. Of those who were terribly anxious before, some feel oddly calmer – the world has ramped up to meet their level of anxiety and they feel vindicated. No one thinks they are odd for worrying about germs on door knobs or elevator buttons. What were once neurotic fears are now our real-life reality. Others have been triggered by a paralyzing fear, often with panic attacks, and these sessions are certainly challenging as I figure out which medications will best help, while responding to requests for reassurance. And there is the troublesome aspect of trying to care for others who are fearful while living with the reality that these fears are not extraneous to our own lives: We, too, are scared for ourselves and our families.

For some people, stay-at-home mandates have been easier than for others. People who are naturally introverted, or those with social anxiety, have told me they find this time at home to be a relief. They no longer feel pressured to go out; there is permission to be alone, to read, or watch Netflix. No one is pressuring them to go to parties or look for a Tinder date. For others, the isolation and loneliness have been devastating, causing a range of emotions from being “stir crazy,” to triggering episodes of major depression and severe anxiety.

Health care workers in therapy talk about their fears of being contaminated with coronavirus, about the exposures they’ve had, their fears of bringing the virus home to family, and about the anger – sometimes rage – that their employers are not doing more to protect them.

Few people these past weeks are looking for insight into their patterns of behavior and emotion. Most of life has come to be about survival and not about personal striving. Students who are driven to excel are disappointed to have their scholastic worlds have switched to pass/fail. And for those struggling with milder forms of depression and anxiety, both the patients and I have all been a bit perplexed by losing the usual measures of what feelings are normal in a tragic world and we no longer use socializing as the hallmark that heralds a return to normalcy after a period of withdrawal.

In some aspects, it is not all been bad. I’ve enjoyed watching my neighbors walk by with their dogs through the window behind my computer screen and I’ve felt part of the daily evolution as the cherry tree outside that same window turns from dead brown wood to vibrant pink blossoms. I like the flexibility of my schedule and the sensation I always carry of being rushed has quelled. I take more walks and spend more time with the family members who are held captive with me. The dog, who no longer is left alone for hours each day, is certainly a winner.

Some of my colleagues tell me they are overwhelmed – patients they have not seen for years have returned, people are asking for more frequent sessions, and they are suddenly trying to work at home while homeschooling children. I have had only a few of those requests for crisis care, while new referrals are much quieter than normal. Some of my patients have even said that they simply aren’t comfortable meeting this way and they will see me at the other end of the pandemic. A few people I would have expected to hear from I have not, and I fear that those who have lost their jobs may avoiding the cost of treatment – this group I will reach out to in the coming weeks. A little extra time, however, has given me the opportunity to join the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Mental Health team. And my first attempt at teaching a resident seminar by Zoom has gone well.

For some in the medical field, this has been a horrible and traumatic time; they are worked to exhaustion, and surrounded by distress, death, and personal fear with every shift. For others, life has come to a standstill as the elective procedures that fill their days have virtually stopped. For outpatient psychiatry, it’s been a bit of an in-between, we may feel an odd mix of relevant and useless all at the same time, as our services are appreciated by our patients, but as actual soldiers caring for the ill COVID patients, we are leaving that to our colleagues in the EDs, COVID units, and ICUs. As a physician who has not treated a patient in an ICU for decades, I wish I had something more concrete to contribute to the effort, and at the same time, I’m relieved that I don’t.

And what about the patients? How are they doing with remote psychiatry? Some are clearly flustered or frustrated by the technology issues. Other times sessions go smoothly, and the fact that we are talking through screens gets forgotten. Some like the convenience of not having to drive a far distance and no one misses my crowded parking lot.

Kristen, another doctor’s patient in Illinois, commented: “I appreciate the continuity in care, especially if the alternative is delaying appointments. I think that’s most important. The interaction helps manage added anxiety from isolating as well. I don’t think it diminishes the care I receive; it makes me feel that my doctor is still accessible. One other point, since I have had both telemedicine and in-person appointments with my current psychiatrist, is that during in-person meetings, he is usually on his computer and rarely looks at me or makes eye contact. In virtual meetings, I feel he is much more engaged with me.”

In normal times, I spend a good deal of time encouraging patients to work on building their relationships and community – these connections lead people to healthy and fulfilling lives – and now we talk about how to best be socially distant. We see each other as vectors of disease and to greet a friend with a handshake, much less a hug, would be unthinkable. Will our collective psyches ever recover? For those of us who will survive, that remains to be seen. In the meantime, perhaps we are all being forced to be more flexible and innovative.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Presymptomatic or asymptomatic? ID experts on shifting terminology

They also addressed racial disparities surrounding COVID-19, and announced new IDSA guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of the illness.

Regarding the shifting thinking on symptoms and transmission of the novel coronavirus, when it comes to presymptomatic or asymptomatic, “pre” is really the right terminology, Carlos del Rio, MD, professor of medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, said during the briefing, because it’s not that people are asymptomatic but that they develop symptoms later and start transmitting the virus 24 to 48 hours before they develop symptoms.