User login

First protocol on how to use lung ultrasound to triage COVID-19

The first protocol for the use of lung ultrasound to quantitatively and reproducibly assess the degree of lung involvement in patients suspected of having COVID-19 infection has been published by a team of Italian experts with experience using the technology on the front line.

Particularly in Spain and Italy — where the pandemic has struck hardest in Europe — hard-pressed clinicians seeking to quickly understand whether patients with seemingly mild disease could be harboring more serious lung involvement have increasingly relied upon lung ultrasound in the emergency room.

Now Libertario Demi, PhD, head of the ultrasound laboratory, University of Trento, Italy, and colleagues have developed a protocol, published online March 30 in the Journal of Ultrasound Medicine, to standardize practice.

Their research, which builds on previous work by the team, offers broad agreement with industry-led algorithms and emphasizes the use of wireless, handheld ultrasound devices, ideally consisting of a separate probe and tablet, to make sterilization easy.

Firms such as the Butterfly Network, Phillips, Clarius, GE Healthcare, and Siemens are among numerous companies that produce one or more such devices, including some that are completely integrated.

Not Universally Accepted

However, lung ultrasound is not yet universally accepted as a tool for diagnosing pneumonia in the context of COVID-19 and triaging patients.

The National Health Service in England does not even mention lung ultrasound in its radiology decision tool for suspected COVID-19, specifying instead chest X-ray as the first-line diagnostic imaging tool, with CT scanning in equivocal cases.

But Giovanni Volpicelli, MD, University Hospital San Luigi Gonzaga, Turin, Italy, who has previously described his experience to Medscape Medical News, says many patients with COVID-19 in his hospital presented with a negative chest X-ray but were found to have interstitial pneumonia on lung ultrasound.

Moreover, while CT scan remains the gold standard, the risk of nosocomial infection is more easily controlled if patients do not have to be transported to the radiology department but remain in the emergency room and instead undergo lung ultrasound there, he stressed.

Experts Share Experience of Lung Ultrasound in COVID-19

In developing and publishing their protocol, Demi, senior author of the article, and other colleagues from the heavily affected cities of Northern Italy, say their aim is “to share our experience and to propose a standardization with respect to the use of lung ultrasound in the management of COVID-19 patients.”

They reviewed an anonymized database of around 60,000 ultrasound images of confirmed COVID-19 cases and reviewers were blinded to patients’ clinical backgrounds.

For image acquisition, the authors recommend scanning 14 areas in each patient for 10 seconds, making the scans intercostal to cover the widest possible surface area.

They advise the use of a single focal point on the pleural line, which they write, optimizes the beam shape for observing the lung surface.

The authors also urge that the mechanical index (MI) be kept low because high MIs sustained for long periods “may result in damaging the lung.”

They also stress that cosmetic filters and modalities such as harmonic imaging, contrast, doppler, and compounding should be avoided, alongside saturation phenomena.

What Constitutes Intermediate Disease?

Once the images have been taken, they are scored on a 0-3 scale for each of the 14 areas, with no weighting on any individual area.

A score of 0 is given when the pleural line is continuous and regular, with the presence of A-lines, denoting that the lungs are unaffected.

An area is given a score of 3 when the scan shows dense and largely extended white lung tissue, with or without consolidations, indicating severe disease.

At both ends of this spectrum, there is agreement between the Italian protocol and an algorithm developed by the Butterfly Network.

However, the two differ when it comes to scoring intermediate cases. On the Butterfly algorithm, the suggestion is to look for B-lines, caused by fluid and cellular infiltration into the interstitium, and to weigh that against the need for supplementary oxygen.

The Italian team, in contrast, says a score of 1 is given when the pleural line is indented, with vertical areas of white visible below.

A score of 2 is given when the pleural line is broken, with small to large areas of consolidation and associated areas of white below.

Demi told Medscape Medical News that they did not refer to B-lines in their protocol as their visibility depends entirely on the imaging frequency and the probe used.

“This means that scoring on B-lines, people with different machines would give completely different scores for the same patient.”

He continued: “We prefer to refer to horizontal and vertical artifacts, and provide an analysis of the patterns, which is related to the physics of the interactions between the ultrasound waves and lung surface.”

In response, Mike Stone, MD, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, Portland, Oregon, and director of education at Butterfly, said there appears to be wide variation in lung findings that “may or may not correlate with the severity of symptoms.”

He told Medscape Medical News it is “hard to know exactly if someone with pure B-lines will progress to serious illness or if someone with some subpleural consolidations will do well.”

A Negative Ultrasound Is the Most Useful

Volpicelli believes that, in any case, any patient with an intermediate pattern will require further diagnosis, such as other imaging modalities and blood exams, and the real role of lung ultrasound is in assessing patients at either end of the spectrum.

“In other words, there are situations where lung ultrasound can be considered definitive,” he told Medscape Medical News. “For instance, if I see a patient with mild signs of the disease, just fever, and I perform lung ultrasound and see nothing, lung ultrasound rules out pneumonia.”

“This patient may have COVID-19 of course, but they do not have pneumonia, and they can be treated at home, awaiting the result of the swab test. And this is useful because you can reduce the burden in the emergency department.”

Volpicelli continued: “On the other hand, there are patients with acute respiratory failure in respiratory distress. If the lung ultrasound is normal, you can rule out COVID-19 and you need to use other diagnostic procedures to understand the problem.”

“This is also very important for us because it’s crucial to be able to remove the patient from the isolation area and perform CT scan, chest radiography, and all the other diagnostic tools that we need.”

Are Wireless Machines Needed? Not Necessarily

With regard to the use of wireless technology, the Italian team says that “in the setting of COVID-19, wireless probes and tablets represent the most appropriate ultrasound equipment” because they can “easily be wrapped in single-use plastic covers, reducing the risk of contamination,” and making sterilization easy.

Stone suggests that integrated portable devices, however, are no more likely to cause cross-contamination than separate probes and tablets, as they can fit within a sterile sheath as a single unit.

Volpicelli, for his part, doesn’t like what he sees as undue focus on wireless devices for lung ultrasound in the COVID-19 protocols.

He is concerned that recommending them as the best approach may be sending out the wrong message, which could be very “dangerous” as people may then think they cannot perform this screening with standard ultrasound machines.

For him, the issue of cross contamination with standard lung ultrasound machines is “nonexistent. Cleaning the machine is quite easy and I do it hundreds of times per week.”

He does acknowledge, however, that if the lung ultrasound is performed under certain circumstances, for example when a patient is using a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine, “the risk of having the machine contaminated is a little bit higher.”

“In these situations...we have a more intensive cleaning procedure to avoid cross-contamination.”

He stressed: “Not all centers have wireless machines, whereas a normal machine is usually in all hospitals.”

“The advantages of using lung ultrasound [in COVID-19] are too great to be limited by something that is not important in my opinion,” he concluded.

Stone is director of education at the Butterfly Network. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first protocol for the use of lung ultrasound to quantitatively and reproducibly assess the degree of lung involvement in patients suspected of having COVID-19 infection has been published by a team of Italian experts with experience using the technology on the front line.

Particularly in Spain and Italy — where the pandemic has struck hardest in Europe — hard-pressed clinicians seeking to quickly understand whether patients with seemingly mild disease could be harboring more serious lung involvement have increasingly relied upon lung ultrasound in the emergency room.

Now Libertario Demi, PhD, head of the ultrasound laboratory, University of Trento, Italy, and colleagues have developed a protocol, published online March 30 in the Journal of Ultrasound Medicine, to standardize practice.

Their research, which builds on previous work by the team, offers broad agreement with industry-led algorithms and emphasizes the use of wireless, handheld ultrasound devices, ideally consisting of a separate probe and tablet, to make sterilization easy.

Firms such as the Butterfly Network, Phillips, Clarius, GE Healthcare, and Siemens are among numerous companies that produce one or more such devices, including some that are completely integrated.

Not Universally Accepted

However, lung ultrasound is not yet universally accepted as a tool for diagnosing pneumonia in the context of COVID-19 and triaging patients.

The National Health Service in England does not even mention lung ultrasound in its radiology decision tool for suspected COVID-19, specifying instead chest X-ray as the first-line diagnostic imaging tool, with CT scanning in equivocal cases.

But Giovanni Volpicelli, MD, University Hospital San Luigi Gonzaga, Turin, Italy, who has previously described his experience to Medscape Medical News, says many patients with COVID-19 in his hospital presented with a negative chest X-ray but were found to have interstitial pneumonia on lung ultrasound.

Moreover, while CT scan remains the gold standard, the risk of nosocomial infection is more easily controlled if patients do not have to be transported to the radiology department but remain in the emergency room and instead undergo lung ultrasound there, he stressed.

Experts Share Experience of Lung Ultrasound in COVID-19

In developing and publishing their protocol, Demi, senior author of the article, and other colleagues from the heavily affected cities of Northern Italy, say their aim is “to share our experience and to propose a standardization with respect to the use of lung ultrasound in the management of COVID-19 patients.”

They reviewed an anonymized database of around 60,000 ultrasound images of confirmed COVID-19 cases and reviewers were blinded to patients’ clinical backgrounds.

For image acquisition, the authors recommend scanning 14 areas in each patient for 10 seconds, making the scans intercostal to cover the widest possible surface area.

They advise the use of a single focal point on the pleural line, which they write, optimizes the beam shape for observing the lung surface.

The authors also urge that the mechanical index (MI) be kept low because high MIs sustained for long periods “may result in damaging the lung.”

They also stress that cosmetic filters and modalities such as harmonic imaging, contrast, doppler, and compounding should be avoided, alongside saturation phenomena.

What Constitutes Intermediate Disease?

Once the images have been taken, they are scored on a 0-3 scale for each of the 14 areas, with no weighting on any individual area.

A score of 0 is given when the pleural line is continuous and regular, with the presence of A-lines, denoting that the lungs are unaffected.

An area is given a score of 3 when the scan shows dense and largely extended white lung tissue, with or without consolidations, indicating severe disease.

At both ends of this spectrum, there is agreement between the Italian protocol and an algorithm developed by the Butterfly Network.

However, the two differ when it comes to scoring intermediate cases. On the Butterfly algorithm, the suggestion is to look for B-lines, caused by fluid and cellular infiltration into the interstitium, and to weigh that against the need for supplementary oxygen.

The Italian team, in contrast, says a score of 1 is given when the pleural line is indented, with vertical areas of white visible below.

A score of 2 is given when the pleural line is broken, with small to large areas of consolidation and associated areas of white below.

Demi told Medscape Medical News that they did not refer to B-lines in their protocol as their visibility depends entirely on the imaging frequency and the probe used.

“This means that scoring on B-lines, people with different machines would give completely different scores for the same patient.”

He continued: “We prefer to refer to horizontal and vertical artifacts, and provide an analysis of the patterns, which is related to the physics of the interactions between the ultrasound waves and lung surface.”

In response, Mike Stone, MD, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, Portland, Oregon, and director of education at Butterfly, said there appears to be wide variation in lung findings that “may or may not correlate with the severity of symptoms.”

He told Medscape Medical News it is “hard to know exactly if someone with pure B-lines will progress to serious illness or if someone with some subpleural consolidations will do well.”

A Negative Ultrasound Is the Most Useful

Volpicelli believes that, in any case, any patient with an intermediate pattern will require further diagnosis, such as other imaging modalities and blood exams, and the real role of lung ultrasound is in assessing patients at either end of the spectrum.

“In other words, there are situations where lung ultrasound can be considered definitive,” he told Medscape Medical News. “For instance, if I see a patient with mild signs of the disease, just fever, and I perform lung ultrasound and see nothing, lung ultrasound rules out pneumonia.”

“This patient may have COVID-19 of course, but they do not have pneumonia, and they can be treated at home, awaiting the result of the swab test. And this is useful because you can reduce the burden in the emergency department.”

Volpicelli continued: “On the other hand, there are patients with acute respiratory failure in respiratory distress. If the lung ultrasound is normal, you can rule out COVID-19 and you need to use other diagnostic procedures to understand the problem.”

“This is also very important for us because it’s crucial to be able to remove the patient from the isolation area and perform CT scan, chest radiography, and all the other diagnostic tools that we need.”

Are Wireless Machines Needed? Not Necessarily

With regard to the use of wireless technology, the Italian team says that “in the setting of COVID-19, wireless probes and tablets represent the most appropriate ultrasound equipment” because they can “easily be wrapped in single-use plastic covers, reducing the risk of contamination,” and making sterilization easy.

Stone suggests that integrated portable devices, however, are no more likely to cause cross-contamination than separate probes and tablets, as they can fit within a sterile sheath as a single unit.

Volpicelli, for his part, doesn’t like what he sees as undue focus on wireless devices for lung ultrasound in the COVID-19 protocols.

He is concerned that recommending them as the best approach may be sending out the wrong message, which could be very “dangerous” as people may then think they cannot perform this screening with standard ultrasound machines.

For him, the issue of cross contamination with standard lung ultrasound machines is “nonexistent. Cleaning the machine is quite easy and I do it hundreds of times per week.”

He does acknowledge, however, that if the lung ultrasound is performed under certain circumstances, for example when a patient is using a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine, “the risk of having the machine contaminated is a little bit higher.”

“In these situations...we have a more intensive cleaning procedure to avoid cross-contamination.”

He stressed: “Not all centers have wireless machines, whereas a normal machine is usually in all hospitals.”

“The advantages of using lung ultrasound [in COVID-19] are too great to be limited by something that is not important in my opinion,” he concluded.

Stone is director of education at the Butterfly Network. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first protocol for the use of lung ultrasound to quantitatively and reproducibly assess the degree of lung involvement in patients suspected of having COVID-19 infection has been published by a team of Italian experts with experience using the technology on the front line.

Particularly in Spain and Italy — where the pandemic has struck hardest in Europe — hard-pressed clinicians seeking to quickly understand whether patients with seemingly mild disease could be harboring more serious lung involvement have increasingly relied upon lung ultrasound in the emergency room.

Now Libertario Demi, PhD, head of the ultrasound laboratory, University of Trento, Italy, and colleagues have developed a protocol, published online March 30 in the Journal of Ultrasound Medicine, to standardize practice.

Their research, which builds on previous work by the team, offers broad agreement with industry-led algorithms and emphasizes the use of wireless, handheld ultrasound devices, ideally consisting of a separate probe and tablet, to make sterilization easy.

Firms such as the Butterfly Network, Phillips, Clarius, GE Healthcare, and Siemens are among numerous companies that produce one or more such devices, including some that are completely integrated.

Not Universally Accepted

However, lung ultrasound is not yet universally accepted as a tool for diagnosing pneumonia in the context of COVID-19 and triaging patients.

The National Health Service in England does not even mention lung ultrasound in its radiology decision tool for suspected COVID-19, specifying instead chest X-ray as the first-line diagnostic imaging tool, with CT scanning in equivocal cases.

But Giovanni Volpicelli, MD, University Hospital San Luigi Gonzaga, Turin, Italy, who has previously described his experience to Medscape Medical News, says many patients with COVID-19 in his hospital presented with a negative chest X-ray but were found to have interstitial pneumonia on lung ultrasound.

Moreover, while CT scan remains the gold standard, the risk of nosocomial infection is more easily controlled if patients do not have to be transported to the radiology department but remain in the emergency room and instead undergo lung ultrasound there, he stressed.

Experts Share Experience of Lung Ultrasound in COVID-19

In developing and publishing their protocol, Demi, senior author of the article, and other colleagues from the heavily affected cities of Northern Italy, say their aim is “to share our experience and to propose a standardization with respect to the use of lung ultrasound in the management of COVID-19 patients.”

They reviewed an anonymized database of around 60,000 ultrasound images of confirmed COVID-19 cases and reviewers were blinded to patients’ clinical backgrounds.

For image acquisition, the authors recommend scanning 14 areas in each patient for 10 seconds, making the scans intercostal to cover the widest possible surface area.

They advise the use of a single focal point on the pleural line, which they write, optimizes the beam shape for observing the lung surface.

The authors also urge that the mechanical index (MI) be kept low because high MIs sustained for long periods “may result in damaging the lung.”

They also stress that cosmetic filters and modalities such as harmonic imaging, contrast, doppler, and compounding should be avoided, alongside saturation phenomena.

What Constitutes Intermediate Disease?

Once the images have been taken, they are scored on a 0-3 scale for each of the 14 areas, with no weighting on any individual area.

A score of 0 is given when the pleural line is continuous and regular, with the presence of A-lines, denoting that the lungs are unaffected.

An area is given a score of 3 when the scan shows dense and largely extended white lung tissue, with or without consolidations, indicating severe disease.

At both ends of this spectrum, there is agreement between the Italian protocol and an algorithm developed by the Butterfly Network.

However, the two differ when it comes to scoring intermediate cases. On the Butterfly algorithm, the suggestion is to look for B-lines, caused by fluid and cellular infiltration into the interstitium, and to weigh that against the need for supplementary oxygen.

The Italian team, in contrast, says a score of 1 is given when the pleural line is indented, with vertical areas of white visible below.

A score of 2 is given when the pleural line is broken, with small to large areas of consolidation and associated areas of white below.

Demi told Medscape Medical News that they did not refer to B-lines in their protocol as their visibility depends entirely on the imaging frequency and the probe used.

“This means that scoring on B-lines, people with different machines would give completely different scores for the same patient.”

He continued: “We prefer to refer to horizontal and vertical artifacts, and provide an analysis of the patterns, which is related to the physics of the interactions between the ultrasound waves and lung surface.”

In response, Mike Stone, MD, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, Portland, Oregon, and director of education at Butterfly, said there appears to be wide variation in lung findings that “may or may not correlate with the severity of symptoms.”

He told Medscape Medical News it is “hard to know exactly if someone with pure B-lines will progress to serious illness or if someone with some subpleural consolidations will do well.”

A Negative Ultrasound Is the Most Useful

Volpicelli believes that, in any case, any patient with an intermediate pattern will require further diagnosis, such as other imaging modalities and blood exams, and the real role of lung ultrasound is in assessing patients at either end of the spectrum.

“In other words, there are situations where lung ultrasound can be considered definitive,” he told Medscape Medical News. “For instance, if I see a patient with mild signs of the disease, just fever, and I perform lung ultrasound and see nothing, lung ultrasound rules out pneumonia.”

“This patient may have COVID-19 of course, but they do not have pneumonia, and they can be treated at home, awaiting the result of the swab test. And this is useful because you can reduce the burden in the emergency department.”

Volpicelli continued: “On the other hand, there are patients with acute respiratory failure in respiratory distress. If the lung ultrasound is normal, you can rule out COVID-19 and you need to use other diagnostic procedures to understand the problem.”

“This is also very important for us because it’s crucial to be able to remove the patient from the isolation area and perform CT scan, chest radiography, and all the other diagnostic tools that we need.”

Are Wireless Machines Needed? Not Necessarily

With regard to the use of wireless technology, the Italian team says that “in the setting of COVID-19, wireless probes and tablets represent the most appropriate ultrasound equipment” because they can “easily be wrapped in single-use plastic covers, reducing the risk of contamination,” and making sterilization easy.

Stone suggests that integrated portable devices, however, are no more likely to cause cross-contamination than separate probes and tablets, as they can fit within a sterile sheath as a single unit.

Volpicelli, for his part, doesn’t like what he sees as undue focus on wireless devices for lung ultrasound in the COVID-19 protocols.

He is concerned that recommending them as the best approach may be sending out the wrong message, which could be very “dangerous” as people may then think they cannot perform this screening with standard ultrasound machines.

For him, the issue of cross contamination with standard lung ultrasound machines is “nonexistent. Cleaning the machine is quite easy and I do it hundreds of times per week.”

He does acknowledge, however, that if the lung ultrasound is performed under certain circumstances, for example when a patient is using a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine, “the risk of having the machine contaminated is a little bit higher.”

“In these situations...we have a more intensive cleaning procedure to avoid cross-contamination.”

He stressed: “Not all centers have wireless machines, whereas a normal machine is usually in all hospitals.”

“The advantages of using lung ultrasound [in COVID-19] are too great to be limited by something that is not important in my opinion,” he concluded.

Stone is director of education at the Butterfly Network. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Crisis counseling, not therapy, is what’s needed in the wake of COVID-19

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 and surge capacity in U.S. hospitals

Background

As of April 2020, the United States is faced with the early stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Experts predict up to 60% of the population will become infected with a fatality rate of 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%. Efforts to suppress viral spread have been unsuccessful as cases are reported in all 50 states, and fatalities are rising. Currently many American hospitals are ill-prepared for a significant increase in their census of critically ill and contagious patients, i.e., hospitals lack adequate surge capacity to safely handle a nationwide outbreak of COVID-19. As seen in other nations such as Italy, China, and Iran, this leads to rationing of life-saving health care and potentially preventable morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Hospitals will be unable to provide the current standard of care to patients as the rate of infection with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) escalates. As of April 9, the World Health Organization has confirmed 1,539,118 cases and 89,998 deaths globally; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has confirmed 435,941 cases and 14,865 deaths in the United States.1,2 Experts predict up to 60% of the population will eventually become infected with a fatality rate of about 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%.3,4

In the United States, with a population of 300 million people, this represents up to 180 million infected, 36 million requiring hospitalization, 11 million requiring intensive care, and 2 million fatalities over the duration of the pandemic. On March 13, President Donald Trump declared a state of national emergency, authorizing $50 billion dollars in emergency health care spending as well as asking every hospital in the country to immediately activate its emergency response plan. The use of isolation and quarantine may space out casualties over time, however high rates and volumes of hospitalizations are still expected.4,5

As the influx of patients afflicted with COVID-19 grows, needs will outstrip hospital resources forcing clinicians to ration beds and supplies. In Italy, China, and Iran, physicians are already faced with these difficult decisions. Antonio Pesenti, head of the Italian Lombardy regional crisis response unit, characterized the change in health care delivery: “We’re now being forced to set up intensive care treatment in corridors, in operating theaters, in recovery rooms. We’ve emptied entire hospital sections to make space for seriously sick people.”6

Surge capacity

Surge capacity is a hospital’s ability to adequately care for a significant influx of patients.7 Since 2011, the American College of Emergency Physicians has published guidelines calling for hospitals to have a surge capacity accounting for infectious disease outbreaks, and demands on supplies, personnel, and physical space.7 Even prior to the development of COVID-19, many hospitals faced emergency department crowding and strains on hospital capacity.8 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants at 2.77 for the USA, 3.18 for Italy, 4.34 for China, and 13.05 for Japan.9 Before COVID-19 many American hospitals had an insufficient number of beds. Now, in the initial phase of the pandemic, it is even more important to optimize surge capacity across the American health care system.

Requirements for COVID-19 preparation

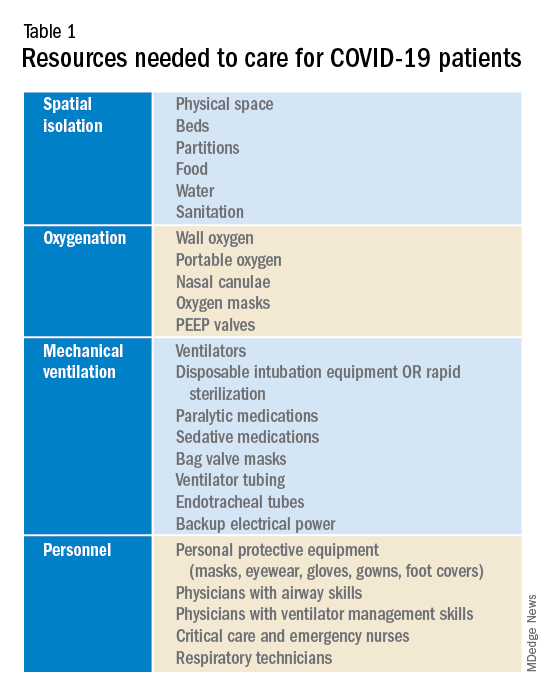

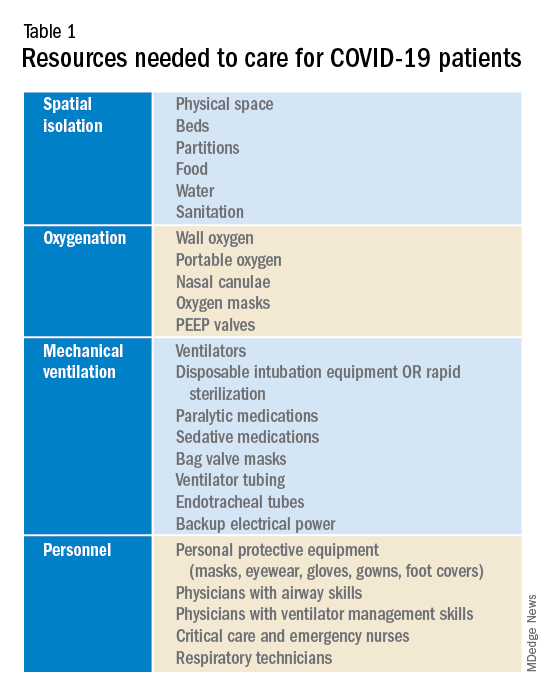

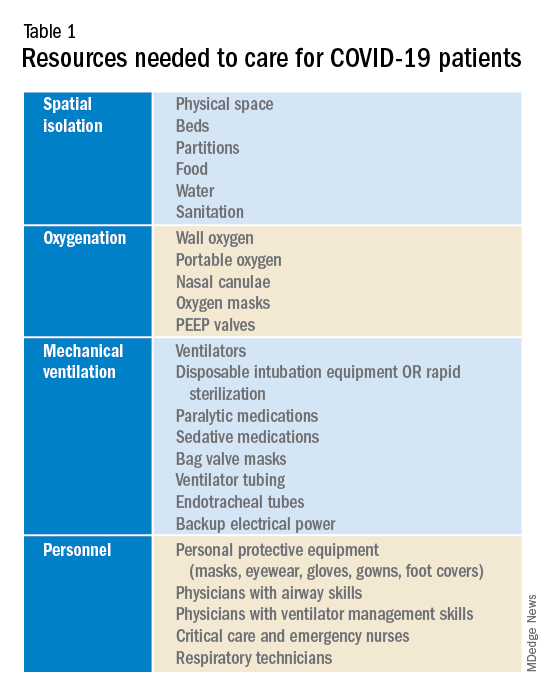

To prepare for the increased number of seriously and critically ill patients, individual hospitals and regions must perform a needs assessment. The fundamental disease process of COVID-19 is a contagious viral pneumonia; treatment hinges on four major categories of intervention: spatial isolation (including physical space, beds, partitions, droplet precautions, food, water, and sanitation), oxygenation (including wall and portable oxygen, nasal canulae, and masks), mechanical ventilation (including ventilator machines, tubing, anesthetics, and reliable electrical power) and personnel (including physicians, nurses, technicians, and adequate personal protective equipment).10 In special circumstances and where available, extra corporeal membrane oxygenation may be considered.10 The necessary interventions are summarized in Table 1.

Emergency, critical care, nursing, and medical leadership should consider what sort of space, personnel, and supplies will be needed to care for a large volume of patients with contagious viral pneumonia at the same time as other hospital patients. Attention should also be given to potential need for morgue expansion. Hospitals must be proactive in procuring supplies and preparing for demands on beds and physical space. Specifically, logistics coordinators should start stockpiling ventilators, oxygen, respiratory equipment, and personal protective equipment. Reallocating supplies from other regions of the hospital such as operating rooms and ambulatory surgery centers may be considered. These resources, particularly ventilators and ventilator supplies, are already in disturbingly limited supply, and they are likely to be single most important limiting factor for survival rates. To prevent regional shortages, stockpiling efforts should ideally be aided by state and federal governments. The production and acquisition of ventilators should be immediately and significantly increased.

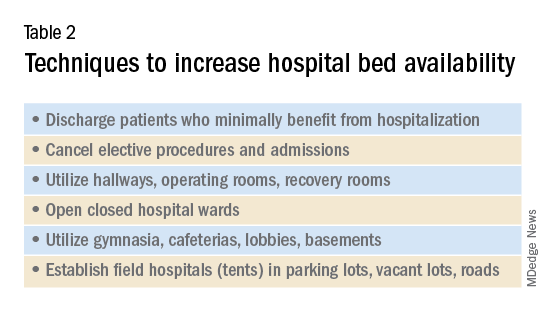

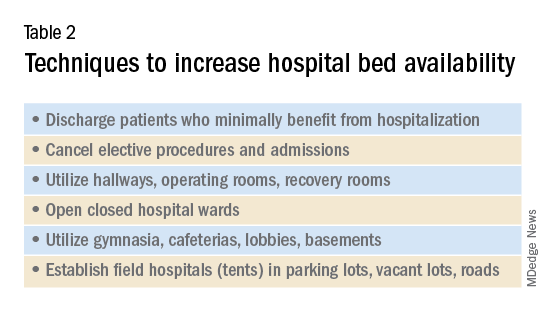

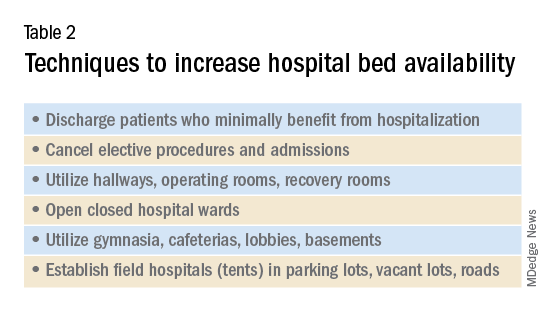

Hospitals must additionally prepare for demands for physical space and beds. Techniques to maximize space and bed availability (see Table 2) include discharging patients who do not require hospitalization, and canceling elective procedures and admissions. Additional methods would be to utilize unconventional preexisting spaces such as hallways, operating rooms, recovery rooms, hallways, closed hospital wards, basements, lobbies, cafeterias, and parking lots. Administrators should also consider establishing field hospitals or field wards, such as tents in open spaces and nearby roads. Medical care performed in unconventional environments will need to account for electricity, temperature control, oxygen delivery, and sanitation.

Conclusion

To minimize unnecessary loss of life and suffering, hospitals must expand their surge capacities in preparation for the predictable rise in demand for health care resources related to COVID-19. Numerous hospitals, particularly those that serve low-income and underserved communities, operate with a narrow financial margin.11 Independently preparing for the surge capacity needed to face COVID-19 may be infeasible for several hospitals. As a result, many health care systems will rely on government aid during this period for financial and material support. To maximize preparedness and response, hospitals should ask for and receive aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), American Red Cross, state governments, and the military; these resources should be mobilized now.

Dr. Blumenberg, Dr. Noble, and Dr. Hendrickson are based in the department of emergency medicine & toxicology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

References

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 60. 2020 Mar 19.

2. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cases in the U.S. CDC. 2020 Apr 8.

3. Li Q et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

4. Anderson RM et al. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5.

5. Fraser C et al. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6146-51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307506101.

6. Mackenzie J and Balmer C. Italy locks down millions as its coronavirus deaths jump. Reuters. 2020 Mar 9.

7. Health care system surge capacity recognition, preparedness, and response. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(3):240-1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.030.

8. Pitts SR et al. A cross-sectional study of emergency department boarding practices in the United States. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):497-503. doi: 10.1111/acem.12375.

9. Health at a Glance 2019. OECD; 2019. doi: 10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

10. Murthy S et al. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633.

11. Ly DP et al. The association between hospital margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1291-6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1815-5.

Background

As of April 2020, the United States is faced with the early stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Experts predict up to 60% of the population will become infected with a fatality rate of 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%. Efforts to suppress viral spread have been unsuccessful as cases are reported in all 50 states, and fatalities are rising. Currently many American hospitals are ill-prepared for a significant increase in their census of critically ill and contagious patients, i.e., hospitals lack adequate surge capacity to safely handle a nationwide outbreak of COVID-19. As seen in other nations such as Italy, China, and Iran, this leads to rationing of life-saving health care and potentially preventable morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Hospitals will be unable to provide the current standard of care to patients as the rate of infection with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) escalates. As of April 9, the World Health Organization has confirmed 1,539,118 cases and 89,998 deaths globally; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has confirmed 435,941 cases and 14,865 deaths in the United States.1,2 Experts predict up to 60% of the population will eventually become infected with a fatality rate of about 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%.3,4

In the United States, with a population of 300 million people, this represents up to 180 million infected, 36 million requiring hospitalization, 11 million requiring intensive care, and 2 million fatalities over the duration of the pandemic. On March 13, President Donald Trump declared a state of national emergency, authorizing $50 billion dollars in emergency health care spending as well as asking every hospital in the country to immediately activate its emergency response plan. The use of isolation and quarantine may space out casualties over time, however high rates and volumes of hospitalizations are still expected.4,5

As the influx of patients afflicted with COVID-19 grows, needs will outstrip hospital resources forcing clinicians to ration beds and supplies. In Italy, China, and Iran, physicians are already faced with these difficult decisions. Antonio Pesenti, head of the Italian Lombardy regional crisis response unit, characterized the change in health care delivery: “We’re now being forced to set up intensive care treatment in corridors, in operating theaters, in recovery rooms. We’ve emptied entire hospital sections to make space for seriously sick people.”6

Surge capacity

Surge capacity is a hospital’s ability to adequately care for a significant influx of patients.7 Since 2011, the American College of Emergency Physicians has published guidelines calling for hospitals to have a surge capacity accounting for infectious disease outbreaks, and demands on supplies, personnel, and physical space.7 Even prior to the development of COVID-19, many hospitals faced emergency department crowding and strains on hospital capacity.8 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants at 2.77 for the USA, 3.18 for Italy, 4.34 for China, and 13.05 for Japan.9 Before COVID-19 many American hospitals had an insufficient number of beds. Now, in the initial phase of the pandemic, it is even more important to optimize surge capacity across the American health care system.

Requirements for COVID-19 preparation

To prepare for the increased number of seriously and critically ill patients, individual hospitals and regions must perform a needs assessment. The fundamental disease process of COVID-19 is a contagious viral pneumonia; treatment hinges on four major categories of intervention: spatial isolation (including physical space, beds, partitions, droplet precautions, food, water, and sanitation), oxygenation (including wall and portable oxygen, nasal canulae, and masks), mechanical ventilation (including ventilator machines, tubing, anesthetics, and reliable electrical power) and personnel (including physicians, nurses, technicians, and adequate personal protective equipment).10 In special circumstances and where available, extra corporeal membrane oxygenation may be considered.10 The necessary interventions are summarized in Table 1.

Emergency, critical care, nursing, and medical leadership should consider what sort of space, personnel, and supplies will be needed to care for a large volume of patients with contagious viral pneumonia at the same time as other hospital patients. Attention should also be given to potential need for morgue expansion. Hospitals must be proactive in procuring supplies and preparing for demands on beds and physical space. Specifically, logistics coordinators should start stockpiling ventilators, oxygen, respiratory equipment, and personal protective equipment. Reallocating supplies from other regions of the hospital such as operating rooms and ambulatory surgery centers may be considered. These resources, particularly ventilators and ventilator supplies, are already in disturbingly limited supply, and they are likely to be single most important limiting factor for survival rates. To prevent regional shortages, stockpiling efforts should ideally be aided by state and federal governments. The production and acquisition of ventilators should be immediately and significantly increased.

Hospitals must additionally prepare for demands for physical space and beds. Techniques to maximize space and bed availability (see Table 2) include discharging patients who do not require hospitalization, and canceling elective procedures and admissions. Additional methods would be to utilize unconventional preexisting spaces such as hallways, operating rooms, recovery rooms, hallways, closed hospital wards, basements, lobbies, cafeterias, and parking lots. Administrators should also consider establishing field hospitals or field wards, such as tents in open spaces and nearby roads. Medical care performed in unconventional environments will need to account for electricity, temperature control, oxygen delivery, and sanitation.

Conclusion

To minimize unnecessary loss of life and suffering, hospitals must expand their surge capacities in preparation for the predictable rise in demand for health care resources related to COVID-19. Numerous hospitals, particularly those that serve low-income and underserved communities, operate with a narrow financial margin.11 Independently preparing for the surge capacity needed to face COVID-19 may be infeasible for several hospitals. As a result, many health care systems will rely on government aid during this period for financial and material support. To maximize preparedness and response, hospitals should ask for and receive aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), American Red Cross, state governments, and the military; these resources should be mobilized now.

Dr. Blumenberg, Dr. Noble, and Dr. Hendrickson are based in the department of emergency medicine & toxicology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

References

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 60. 2020 Mar 19.

2. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cases in the U.S. CDC. 2020 Apr 8.

3. Li Q et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

4. Anderson RM et al. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5.

5. Fraser C et al. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6146-51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307506101.

6. Mackenzie J and Balmer C. Italy locks down millions as its coronavirus deaths jump. Reuters. 2020 Mar 9.

7. Health care system surge capacity recognition, preparedness, and response. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(3):240-1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.030.

8. Pitts SR et al. A cross-sectional study of emergency department boarding practices in the United States. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):497-503. doi: 10.1111/acem.12375.

9. Health at a Glance 2019. OECD; 2019. doi: 10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

10. Murthy S et al. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633.

11. Ly DP et al. The association between hospital margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1291-6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1815-5.

Background

As of April 2020, the United States is faced with the early stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Experts predict up to 60% of the population will become infected with a fatality rate of 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%. Efforts to suppress viral spread have been unsuccessful as cases are reported in all 50 states, and fatalities are rising. Currently many American hospitals are ill-prepared for a significant increase in their census of critically ill and contagious patients, i.e., hospitals lack adequate surge capacity to safely handle a nationwide outbreak of COVID-19. As seen in other nations such as Italy, China, and Iran, this leads to rationing of life-saving health care and potentially preventable morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Hospitals will be unable to provide the current standard of care to patients as the rate of infection with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) escalates. As of April 9, the World Health Organization has confirmed 1,539,118 cases and 89,998 deaths globally; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has confirmed 435,941 cases and 14,865 deaths in the United States.1,2 Experts predict up to 60% of the population will eventually become infected with a fatality rate of about 1% and a hospitalization rate of approximately 20%.3,4

In the United States, with a population of 300 million people, this represents up to 180 million infected, 36 million requiring hospitalization, 11 million requiring intensive care, and 2 million fatalities over the duration of the pandemic. On March 13, President Donald Trump declared a state of national emergency, authorizing $50 billion dollars in emergency health care spending as well as asking every hospital in the country to immediately activate its emergency response plan. The use of isolation and quarantine may space out casualties over time, however high rates and volumes of hospitalizations are still expected.4,5

As the influx of patients afflicted with COVID-19 grows, needs will outstrip hospital resources forcing clinicians to ration beds and supplies. In Italy, China, and Iran, physicians are already faced with these difficult decisions. Antonio Pesenti, head of the Italian Lombardy regional crisis response unit, characterized the change in health care delivery: “We’re now being forced to set up intensive care treatment in corridors, in operating theaters, in recovery rooms. We’ve emptied entire hospital sections to make space for seriously sick people.”6

Surge capacity

Surge capacity is a hospital’s ability to adequately care for a significant influx of patients.7 Since 2011, the American College of Emergency Physicians has published guidelines calling for hospitals to have a surge capacity accounting for infectious disease outbreaks, and demands on supplies, personnel, and physical space.7 Even prior to the development of COVID-19, many hospitals faced emergency department crowding and strains on hospital capacity.8 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants at 2.77 for the USA, 3.18 for Italy, 4.34 for China, and 13.05 for Japan.9 Before COVID-19 many American hospitals had an insufficient number of beds. Now, in the initial phase of the pandemic, it is even more important to optimize surge capacity across the American health care system.

Requirements for COVID-19 preparation

To prepare for the increased number of seriously and critically ill patients, individual hospitals and regions must perform a needs assessment. The fundamental disease process of COVID-19 is a contagious viral pneumonia; treatment hinges on four major categories of intervention: spatial isolation (including physical space, beds, partitions, droplet precautions, food, water, and sanitation), oxygenation (including wall and portable oxygen, nasal canulae, and masks), mechanical ventilation (including ventilator machines, tubing, anesthetics, and reliable electrical power) and personnel (including physicians, nurses, technicians, and adequate personal protective equipment).10 In special circumstances and where available, extra corporeal membrane oxygenation may be considered.10 The necessary interventions are summarized in Table 1.

Emergency, critical care, nursing, and medical leadership should consider what sort of space, personnel, and supplies will be needed to care for a large volume of patients with contagious viral pneumonia at the same time as other hospital patients. Attention should also be given to potential need for morgue expansion. Hospitals must be proactive in procuring supplies and preparing for demands on beds and physical space. Specifically, logistics coordinators should start stockpiling ventilators, oxygen, respiratory equipment, and personal protective equipment. Reallocating supplies from other regions of the hospital such as operating rooms and ambulatory surgery centers may be considered. These resources, particularly ventilators and ventilator supplies, are already in disturbingly limited supply, and they are likely to be single most important limiting factor for survival rates. To prevent regional shortages, stockpiling efforts should ideally be aided by state and federal governments. The production and acquisition of ventilators should be immediately and significantly increased.

Hospitals must additionally prepare for demands for physical space and beds. Techniques to maximize space and bed availability (see Table 2) include discharging patients who do not require hospitalization, and canceling elective procedures and admissions. Additional methods would be to utilize unconventional preexisting spaces such as hallways, operating rooms, recovery rooms, hallways, closed hospital wards, basements, lobbies, cafeterias, and parking lots. Administrators should also consider establishing field hospitals or field wards, such as tents in open spaces and nearby roads. Medical care performed in unconventional environments will need to account for electricity, temperature control, oxygen delivery, and sanitation.

Conclusion

To minimize unnecessary loss of life and suffering, hospitals must expand their surge capacities in preparation for the predictable rise in demand for health care resources related to COVID-19. Numerous hospitals, particularly those that serve low-income and underserved communities, operate with a narrow financial margin.11 Independently preparing for the surge capacity needed to face COVID-19 may be infeasible for several hospitals. As a result, many health care systems will rely on government aid during this period for financial and material support. To maximize preparedness and response, hospitals should ask for and receive aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), American Red Cross, state governments, and the military; these resources should be mobilized now.

Dr. Blumenberg, Dr. Noble, and Dr. Hendrickson are based in the department of emergency medicine & toxicology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

References

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 60. 2020 Mar 19.

2. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cases in the U.S. CDC. 2020 Apr 8.

3. Li Q et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

4. Anderson RM et al. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5.

5. Fraser C et al. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6146-51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307506101.

6. Mackenzie J and Balmer C. Italy locks down millions as its coronavirus deaths jump. Reuters. 2020 Mar 9.

7. Health care system surge capacity recognition, preparedness, and response. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(3):240-1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.030.

8. Pitts SR et al. A cross-sectional study of emergency department boarding practices in the United States. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):497-503. doi: 10.1111/acem.12375.

9. Health at a Glance 2019. OECD; 2019. doi: 10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

10. Murthy S et al. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633.

11. Ly DP et al. The association between hospital margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1291-6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1815-5.

See acute hepatitis? Consider COVID-19, N.Y. case suggests

A woman presented to the emergency department with high liver enzyme levels and dark urine. She developed fever on day 2 of care, and then tested positive for the new coronavirus, researchers at Northwell Health, in Hempstead, New York, report.

The authors say the case, published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, is the first documented instance of a patient with COVID-19 presenting with acute hepatitis as the primary symptom before developing respiratory symptoms.

Prior data show that the most common early indications of COVID-19 are respiratory symptoms with fever, shortness of breath, sore throat, and cough, and with imaging results consistent with pneumonia. However, liver enzyme abnormalities are not uncommon in the disease course.

“In patients who are now presenting with acute hepatitis, people need to think of COVID,” senior author David Bernstein, MD, chief of the Division of Hepatology at Northwell Health, told Medscape Medical News.

In addition to Bernstein, Praneet Wander, MD, also in Northwell’s hepatology division, and Marcia Epstein, MD, with Northwell’s Department of Infectious Disease, authored the case report.

Bernstein said Northwell currently has the largest number of COVID-19 cases in the nation and that many patients are presenting with abnormal liver test results and COVID-19 symptoms.

He said that anecdotally, colleagues elsewhere in the United States are also reporting the connection.

“It seems to be that the liver enzyme elevations are part and parcel of this disease,” he said.

Case Details

According to the case report, the 59-year-old woman, who lives alone, came to the emergency department with a chief complaint of dark urine. She was given a face mask and was isolated, per protocol.

“She denied cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain,” the authors wrote. She denied having been in contact with someone who was sick.

She had well-controlled HIV, and recent outpatient liver test results were normal. Eighteen hours after she came to the ED, she was admitted, owing to concern regarding rising liver enzyme levels in conjunction with her being HIV positive.

On presentation, her temperature was 98.9° F. There were no skin indications, lungs were normal, and “there was no jaundice, right upper quadrant tenderness, hepatomegaly or splenomegaly.”

Liver enzyme levels were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 1230 (IU/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 697 IU/L (normal for both is < 50 IU/L); alkaline phosphatase, 141 IU/L (normal, < 125 IU/L).

The patient tested negative for hepatitis A, B, C, E, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus. A respiratory viral panel and autoimmune markers were normal.

Fever Appeared on Day 2

She was admitted, and 18 hours after she came to the ED, she developed a fever of 102.2° F. A chest x-ray showed interstitial opacities in both lungs.

Nasopharyngeal samples were taken, and polymerase chain reaction test results were positive for the novel coronavirus. The patient was placed on 3 L of oxygen.

On post admission day 4, a 5-day course of hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice a day) was initiated.

The patient was discharged to home on hospital day 8. The serum bilirubin level was 0.6 mg/dL; AST, 114 IU/L; ALT, 227 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase, 259 IU/L.

According to Bernstein, it’s hard to tell in what order COVID-19 symptoms occur because people are staying home with other complaints. They may only present to the emergency department after they develop more typical COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath.

In this case, the patient noticed a darkening of her urine, “but if she had come the next day, she would have had fever. I think we just happened to catch it early,” Bernstein said.

He added that he saw no connection between the underlying HIV and her liver abnormalities or COVID-19 diagnosis.

Bernstein notes that most COVID-19 patients are not admitted, and he said he worries that a COVID-19 test might not be on the radar of providers in the outpatient setting when a patient presents with elevated liver enzymes levels.

If elevated liver enzyme levels can predict disease course, the information could alter how and where the disease is treated, Bernstein said.

“This is a first report. We’re really right now in the beginning of learning,” he said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A woman presented to the emergency department with high liver enzyme levels and dark urine. She developed fever on day 2 of care, and then tested positive for the new coronavirus, researchers at Northwell Health, in Hempstead, New York, report.

The authors say the case, published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, is the first documented instance of a patient with COVID-19 presenting with acute hepatitis as the primary symptom before developing respiratory symptoms.

Prior data show that the most common early indications of COVID-19 are respiratory symptoms with fever, shortness of breath, sore throat, and cough, and with imaging results consistent with pneumonia. However, liver enzyme abnormalities are not uncommon in the disease course.

“In patients who are now presenting with acute hepatitis, people need to think of COVID,” senior author David Bernstein, MD, chief of the Division of Hepatology at Northwell Health, told Medscape Medical News.

In addition to Bernstein, Praneet Wander, MD, also in Northwell’s hepatology division, and Marcia Epstein, MD, with Northwell’s Department of Infectious Disease, authored the case report.

Bernstein said Northwell currently has the largest number of COVID-19 cases in the nation and that many patients are presenting with abnormal liver test results and COVID-19 symptoms.

He said that anecdotally, colleagues elsewhere in the United States are also reporting the connection.

“It seems to be that the liver enzyme elevations are part and parcel of this disease,” he said.

Case Details

According to the case report, the 59-year-old woman, who lives alone, came to the emergency department with a chief complaint of dark urine. She was given a face mask and was isolated, per protocol.

“She denied cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain,” the authors wrote. She denied having been in contact with someone who was sick.

She had well-controlled HIV, and recent outpatient liver test results were normal. Eighteen hours after she came to the ED, she was admitted, owing to concern regarding rising liver enzyme levels in conjunction with her being HIV positive.

On presentation, her temperature was 98.9° F. There were no skin indications, lungs were normal, and “there was no jaundice, right upper quadrant tenderness, hepatomegaly or splenomegaly.”