User login

Bone Infections Increase After S. aureus Bacteremia in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis

TOPLINE:

After Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) face nearly double the risk for osteoarticular infections compared with those without RA, with similar mortality risks in both groups.

METHODOLOGY:

- The contraction of S aureus bacteremia is linked to poor clinical outcomes in patients with RA; however, no well-sized studies have evaluated the risk for osteoarticular infections and mortality outcomes in patients with RA following S aureus bacteremia.

- This Danish nationwide cohort study aimed to explore whether the cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections and death would be higher in patients with RA than in those without RA after contracting S aureus bacteremia.

- The study cohort included 18,274 patients with a first episode of S aureus bacteremia between 2006 and 2018, of whom 367 had been diagnosed with RA before contracting S aureus bacteremia.

- The RA cohort had more women (62%) and a higher median age of participants (73 years) than the non-RA cohort (37% women; median age of participants, 70 years).

TAKEAWAY:

- The 90-day cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections (septic arthritis, spondylitis, osteomyelitis, psoas muscle abscess, or prosthetic joint infection) was nearly double in patients with RA compared with in those without RA (23.1% vs 12.5%; hazard ratio [HR], 1.93; 95% CI, 1.54-2.41).

- In patients with RA, the risk for osteoarticular infections increased with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use (HR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.29-3.98) and orthopedic implants (HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.08-2.85).

- Moreover, 90-day all-cause mortality was comparable in the RA (35.4%) and non-RA cohorts (33.9%).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings stress the need for vigilance in patients with RA who present with S aureus bacteremia to ensure timely identification and treatment of osteoarticular infections, especially in current TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] users and patients with orthopedic implants,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Sabine S. Dieperink, MD, of the Centre of Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen University Rigshospitalet Glostrup, Denmark, was published online March 9 in Rheumatology (Oxford).

LIMITATIONS:

There might have been chances of misclassification of metastatic S aureus infections owing to the lack of specificity in diagnoses or procedure codes. This study relied on administrative data to record osteoarticular infections, which might have led investigators to underestimate the true cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections. Also, some patients might have passed away before being diagnosed with osteoarticular infection owing to the high mortality.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by grants from The Danish Rheumatism Association and Beckett Fonden. Some of the authors, including the lead author, declared receiving grants from various funding agencies and other sources, including pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

After Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) face nearly double the risk for osteoarticular infections compared with those without RA, with similar mortality risks in both groups.

METHODOLOGY:

- The contraction of S aureus bacteremia is linked to poor clinical outcomes in patients with RA; however, no well-sized studies have evaluated the risk for osteoarticular infections and mortality outcomes in patients with RA following S aureus bacteremia.

- This Danish nationwide cohort study aimed to explore whether the cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections and death would be higher in patients with RA than in those without RA after contracting S aureus bacteremia.

- The study cohort included 18,274 patients with a first episode of S aureus bacteremia between 2006 and 2018, of whom 367 had been diagnosed with RA before contracting S aureus bacteremia.

- The RA cohort had more women (62%) and a higher median age of participants (73 years) than the non-RA cohort (37% women; median age of participants, 70 years).

TAKEAWAY:

- The 90-day cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections (septic arthritis, spondylitis, osteomyelitis, psoas muscle abscess, or prosthetic joint infection) was nearly double in patients with RA compared with in those without RA (23.1% vs 12.5%; hazard ratio [HR], 1.93; 95% CI, 1.54-2.41).

- In patients with RA, the risk for osteoarticular infections increased with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use (HR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.29-3.98) and orthopedic implants (HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.08-2.85).

- Moreover, 90-day all-cause mortality was comparable in the RA (35.4%) and non-RA cohorts (33.9%).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings stress the need for vigilance in patients with RA who present with S aureus bacteremia to ensure timely identification and treatment of osteoarticular infections, especially in current TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] users and patients with orthopedic implants,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Sabine S. Dieperink, MD, of the Centre of Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen University Rigshospitalet Glostrup, Denmark, was published online March 9 in Rheumatology (Oxford).

LIMITATIONS:

There might have been chances of misclassification of metastatic S aureus infections owing to the lack of specificity in diagnoses or procedure codes. This study relied on administrative data to record osteoarticular infections, which might have led investigators to underestimate the true cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections. Also, some patients might have passed away before being diagnosed with osteoarticular infection owing to the high mortality.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by grants from The Danish Rheumatism Association and Beckett Fonden. Some of the authors, including the lead author, declared receiving grants from various funding agencies and other sources, including pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

After Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) face nearly double the risk for osteoarticular infections compared with those without RA, with similar mortality risks in both groups.

METHODOLOGY:

- The contraction of S aureus bacteremia is linked to poor clinical outcomes in patients with RA; however, no well-sized studies have evaluated the risk for osteoarticular infections and mortality outcomes in patients with RA following S aureus bacteremia.

- This Danish nationwide cohort study aimed to explore whether the cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections and death would be higher in patients with RA than in those without RA after contracting S aureus bacteremia.

- The study cohort included 18,274 patients with a first episode of S aureus bacteremia between 2006 and 2018, of whom 367 had been diagnosed with RA before contracting S aureus bacteremia.

- The RA cohort had more women (62%) and a higher median age of participants (73 years) than the non-RA cohort (37% women; median age of participants, 70 years).

TAKEAWAY:

- The 90-day cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections (septic arthritis, spondylitis, osteomyelitis, psoas muscle abscess, or prosthetic joint infection) was nearly double in patients with RA compared with in those without RA (23.1% vs 12.5%; hazard ratio [HR], 1.93; 95% CI, 1.54-2.41).

- In patients with RA, the risk for osteoarticular infections increased with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use (HR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.29-3.98) and orthopedic implants (HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.08-2.85).

- Moreover, 90-day all-cause mortality was comparable in the RA (35.4%) and non-RA cohorts (33.9%).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings stress the need for vigilance in patients with RA who present with S aureus bacteremia to ensure timely identification and treatment of osteoarticular infections, especially in current TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] users and patients with orthopedic implants,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Sabine S. Dieperink, MD, of the Centre of Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen University Rigshospitalet Glostrup, Denmark, was published online March 9 in Rheumatology (Oxford).

LIMITATIONS:

There might have been chances of misclassification of metastatic S aureus infections owing to the lack of specificity in diagnoses or procedure codes. This study relied on administrative data to record osteoarticular infections, which might have led investigators to underestimate the true cumulative incidence of osteoarticular infections. Also, some patients might have passed away before being diagnosed with osteoarticular infection owing to the high mortality.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by grants from The Danish Rheumatism Association and Beckett Fonden. Some of the authors, including the lead author, declared receiving grants from various funding agencies and other sources, including pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Study Shows Nirmatrelvir–Ritonavir No More Effective Than Placebo for COVID-19 Symptom Relief

Paxlovid does not significantly alleviate symptoms of COVID-19 compared with placebo among nonhospitalized adults, a new study published April 3 in The New England Journal of Medicine found.

The results suggest that the drug, a combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir, may not be particularly helpful for patients who are not at high risk for severe COVID-19. However, although the rate of hospitalization and death from any cause was low overall, the group that received Paxlovid had a reduced rate compared with people in the placebo group, according to the researchers.

“Clearly, the benefit observed among unvaccinated high-risk persons does not extend to those at lower risk for severe COVID-19,” Rajesh T. Gandhi, MD, and Martin Hirsch, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article. “This result supports guidelines that recommend nirmatrelvir–ritonavir only for persons who are at high risk for disease progression.”

The time from onset to relief of COVID-19 symptoms — including cough, shortness of breath, body aches, and chills — did not differ significantly between the two study groups, the researchers reported. The median time to sustained alleviation of symptoms was 12 days for the Paxlovid group compared with 13 days in the placebo group (P = .60).

However, the phase 2/3 trial found a 57.6% relative reduction in the risk for hospitalizations or death among people who took Paxlovid and were vaccinated but were at high risk for poor outcomes, according to Jennifer Hammond, PhD, head of antiviral development for Pfizer, which makes the drug, and the corresponding author on the study.

Paxlovid has “an increasing body of evidence supporting the strong clinical value of the treatment in preventing hospitalization and death among eligible patients across age groups, vaccination status, and predominant variants,” Dr. Hammond said.

She and her colleagues analyzed data from 1250 adults with symptomatic COVID-19. Participants were fully vaccinated and had a high risk for progression to severe disease or were never vaccinated or had not been in the previous year and had no risk factors for progression to severe disease.

More than half of participants were women, 78.5% were White and 41.4% identified as Hispanic or Latinx. Almost three quarters underwent randomization within 3 days of the start of symptoms, and a little over half had previously received a COVID-19 vaccination. Almost half had one risk factor for severe illness, the most common of these being hypertension (12.3%).

In a subgroup analysis of high-risk participants, hospitalization or death occurred in 0.9% of patients in the Paxlovid group and 2.2% in the placebo group (95% CI, -3.3 to 0.7).

The study’s limitations include that the statistical analysis of COVID-19–related hospitalizations or death from any cause was only descriptive, “because the results for the primary efficacy end point were not significant,” the authors wrote.

Participants who were vaccinated and at high risk were also enrolled regardless of when they had last had a vaccine dose. Furthermore, Paxlovid has a telltale taste, which may have affected the blinding. Finally, the trial was started when the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant was predominant.

Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Hirsch pointed out that only 5% of participants in the trial were older than 65 years and that other than risk factors such as obesity and smoking, just 2% of people had heart or lung disease.

“As with many medical interventions, there is likely to be a gradient of benefit for nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, with the patients at highest risk for progression most likely to derive the greatest benefit,” Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Hirsch wrote in the editorial. “Thus, it appears reasonable to recommend nirmatrelvir–ritonavir primarily for the treatment of COVID-19 in older patients (particularly those ≥ 65 years of age), those who are immunocompromised, and those who have conditions that substantially increase the risk of severe COVID-19, regardless of previous vaccination or infection status.”

The study was supported by Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Paxlovid does not significantly alleviate symptoms of COVID-19 compared with placebo among nonhospitalized adults, a new study published April 3 in The New England Journal of Medicine found.

The results suggest that the drug, a combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir, may not be particularly helpful for patients who are not at high risk for severe COVID-19. However, although the rate of hospitalization and death from any cause was low overall, the group that received Paxlovid had a reduced rate compared with people in the placebo group, according to the researchers.

“Clearly, the benefit observed among unvaccinated high-risk persons does not extend to those at lower risk for severe COVID-19,” Rajesh T. Gandhi, MD, and Martin Hirsch, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article. “This result supports guidelines that recommend nirmatrelvir–ritonavir only for persons who are at high risk for disease progression.”

The time from onset to relief of COVID-19 symptoms — including cough, shortness of breath, body aches, and chills — did not differ significantly between the two study groups, the researchers reported. The median time to sustained alleviation of symptoms was 12 days for the Paxlovid group compared with 13 days in the placebo group (P = .60).

However, the phase 2/3 trial found a 57.6% relative reduction in the risk for hospitalizations or death among people who took Paxlovid and were vaccinated but were at high risk for poor outcomes, according to Jennifer Hammond, PhD, head of antiviral development for Pfizer, which makes the drug, and the corresponding author on the study.

Paxlovid has “an increasing body of evidence supporting the strong clinical value of the treatment in preventing hospitalization and death among eligible patients across age groups, vaccination status, and predominant variants,” Dr. Hammond said.

She and her colleagues analyzed data from 1250 adults with symptomatic COVID-19. Participants were fully vaccinated and had a high risk for progression to severe disease or were never vaccinated or had not been in the previous year and had no risk factors for progression to severe disease.

More than half of participants were women, 78.5% were White and 41.4% identified as Hispanic or Latinx. Almost three quarters underwent randomization within 3 days of the start of symptoms, and a little over half had previously received a COVID-19 vaccination. Almost half had one risk factor for severe illness, the most common of these being hypertension (12.3%).

In a subgroup analysis of high-risk participants, hospitalization or death occurred in 0.9% of patients in the Paxlovid group and 2.2% in the placebo group (95% CI, -3.3 to 0.7).

The study’s limitations include that the statistical analysis of COVID-19–related hospitalizations or death from any cause was only descriptive, “because the results for the primary efficacy end point were not significant,” the authors wrote.

Participants who were vaccinated and at high risk were also enrolled regardless of when they had last had a vaccine dose. Furthermore, Paxlovid has a telltale taste, which may have affected the blinding. Finally, the trial was started when the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant was predominant.

Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Hirsch pointed out that only 5% of participants in the trial were older than 65 years and that other than risk factors such as obesity and smoking, just 2% of people had heart or lung disease.

“As with many medical interventions, there is likely to be a gradient of benefit for nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, with the patients at highest risk for progression most likely to derive the greatest benefit,” Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Hirsch wrote in the editorial. “Thus, it appears reasonable to recommend nirmatrelvir–ritonavir primarily for the treatment of COVID-19 in older patients (particularly those ≥ 65 years of age), those who are immunocompromised, and those who have conditions that substantially increase the risk of severe COVID-19, regardless of previous vaccination or infection status.”

The study was supported by Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Paxlovid does not significantly alleviate symptoms of COVID-19 compared with placebo among nonhospitalized adults, a new study published April 3 in The New England Journal of Medicine found.

The results suggest that the drug, a combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir, may not be particularly helpful for patients who are not at high risk for severe COVID-19. However, although the rate of hospitalization and death from any cause was low overall, the group that received Paxlovid had a reduced rate compared with people in the placebo group, according to the researchers.

“Clearly, the benefit observed among unvaccinated high-risk persons does not extend to those at lower risk for severe COVID-19,” Rajesh T. Gandhi, MD, and Martin Hirsch, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article. “This result supports guidelines that recommend nirmatrelvir–ritonavir only for persons who are at high risk for disease progression.”

The time from onset to relief of COVID-19 symptoms — including cough, shortness of breath, body aches, and chills — did not differ significantly between the two study groups, the researchers reported. The median time to sustained alleviation of symptoms was 12 days for the Paxlovid group compared with 13 days in the placebo group (P = .60).

However, the phase 2/3 trial found a 57.6% relative reduction in the risk for hospitalizations or death among people who took Paxlovid and were vaccinated but were at high risk for poor outcomes, according to Jennifer Hammond, PhD, head of antiviral development for Pfizer, which makes the drug, and the corresponding author on the study.

Paxlovid has “an increasing body of evidence supporting the strong clinical value of the treatment in preventing hospitalization and death among eligible patients across age groups, vaccination status, and predominant variants,” Dr. Hammond said.

She and her colleagues analyzed data from 1250 adults with symptomatic COVID-19. Participants were fully vaccinated and had a high risk for progression to severe disease or were never vaccinated or had not been in the previous year and had no risk factors for progression to severe disease.

More than half of participants were women, 78.5% were White and 41.4% identified as Hispanic or Latinx. Almost three quarters underwent randomization within 3 days of the start of symptoms, and a little over half had previously received a COVID-19 vaccination. Almost half had one risk factor for severe illness, the most common of these being hypertension (12.3%).

In a subgroup analysis of high-risk participants, hospitalization or death occurred in 0.9% of patients in the Paxlovid group and 2.2% in the placebo group (95% CI, -3.3 to 0.7).

The study’s limitations include that the statistical analysis of COVID-19–related hospitalizations or death from any cause was only descriptive, “because the results for the primary efficacy end point were not significant,” the authors wrote.

Participants who were vaccinated and at high risk were also enrolled regardless of when they had last had a vaccine dose. Furthermore, Paxlovid has a telltale taste, which may have affected the blinding. Finally, the trial was started when the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant was predominant.

Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Hirsch pointed out that only 5% of participants in the trial were older than 65 years and that other than risk factors such as obesity and smoking, just 2% of people had heart or lung disease.

“As with many medical interventions, there is likely to be a gradient of benefit for nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, with the patients at highest risk for progression most likely to derive the greatest benefit,” Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Hirsch wrote in the editorial. “Thus, it appears reasonable to recommend nirmatrelvir–ritonavir primarily for the treatment of COVID-19 in older patients (particularly those ≥ 65 years of age), those who are immunocompromised, and those who have conditions that substantially increase the risk of severe COVID-19, regardless of previous vaccination or infection status.”

The study was supported by Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Can VAP be prevented? New data suggest so

Chest Infections and Disaster Response Network

Chest Infections Section

The efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of VAP has been the subject of several studies in recent years. Three large randomized controlled trials, all published since late 2022, have investigated whether antibiotics can prevent VAP and the optimal method of antibiotic administration.

In the AMIKINHAL trial, patients intubated for at least 72 hours in 19 ICUs in France received inhaled amikacin at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day for 3 days.1 Compared with placebo, there was a statistically significant, 7% absolute risk reduction in rate of VAP at 28 days.

In the SUDDICU trial, patients suspected to be intubated for at least 48 hours in 19 ICUs in Australia received a combination of oral paste and gastric suspension containing colistin, tobramycin, and nystatin every 6 hours along with 4 days of intravenous antibiotics.2 There was no difference in the primary outcome of 90-day all-cause mortality; however, there was a statistically significant, 12% reduction in the isolation of antibiotic-resistant organisms in cultures.

In the PROPHY-VAP trial, patients with acute brain injury (Glasgow Coma Scale score [GCS ] ≤12) intubated for at least 48 hours in 9 ICUs in France received a single dose of intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g) within 12 hours of intubation.3 There was an 18% absolute risk reduction in VAP from days 2 to 7 post-ventilation.

These trials, involving distinct patient populations and interventions, indicate that antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce VAP risk under specific circumstances, but its effect on overall outcomes is still uncertain. The understanding of prophylactic antibiotics in VAP prevention is rapidly evolving.

References

1. Ehrmann S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(22):2052-2062.

2. Myburgh JA, et al. JAMA. 2022;328(19):1911-1921.

3. Dahyot-Fizelier C, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;S2213-2600(23):00471-X.

Chest Infections and Disaster Response Network

Chest Infections Section

The efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of VAP has been the subject of several studies in recent years. Three large randomized controlled trials, all published since late 2022, have investigated whether antibiotics can prevent VAP and the optimal method of antibiotic administration.

In the AMIKINHAL trial, patients intubated for at least 72 hours in 19 ICUs in France received inhaled amikacin at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day for 3 days.1 Compared with placebo, there was a statistically significant, 7% absolute risk reduction in rate of VAP at 28 days.

In the SUDDICU trial, patients suspected to be intubated for at least 48 hours in 19 ICUs in Australia received a combination of oral paste and gastric suspension containing colistin, tobramycin, and nystatin every 6 hours along with 4 days of intravenous antibiotics.2 There was no difference in the primary outcome of 90-day all-cause mortality; however, there was a statistically significant, 12% reduction in the isolation of antibiotic-resistant organisms in cultures.

In the PROPHY-VAP trial, patients with acute brain injury (Glasgow Coma Scale score [GCS ] ≤12) intubated for at least 48 hours in 9 ICUs in France received a single dose of intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g) within 12 hours of intubation.3 There was an 18% absolute risk reduction in VAP from days 2 to 7 post-ventilation.

These trials, involving distinct patient populations and interventions, indicate that antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce VAP risk under specific circumstances, but its effect on overall outcomes is still uncertain. The understanding of prophylactic antibiotics in VAP prevention is rapidly evolving.

References

1. Ehrmann S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(22):2052-2062.

2. Myburgh JA, et al. JAMA. 2022;328(19):1911-1921.

3. Dahyot-Fizelier C, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;S2213-2600(23):00471-X.

Chest Infections and Disaster Response Network

Chest Infections Section

The efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics in the prevention of VAP has been the subject of several studies in recent years. Three large randomized controlled trials, all published since late 2022, have investigated whether antibiotics can prevent VAP and the optimal method of antibiotic administration.

In the AMIKINHAL trial, patients intubated for at least 72 hours in 19 ICUs in France received inhaled amikacin at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day for 3 days.1 Compared with placebo, there was a statistically significant, 7% absolute risk reduction in rate of VAP at 28 days.

In the SUDDICU trial, patients suspected to be intubated for at least 48 hours in 19 ICUs in Australia received a combination of oral paste and gastric suspension containing colistin, tobramycin, and nystatin every 6 hours along with 4 days of intravenous antibiotics.2 There was no difference in the primary outcome of 90-day all-cause mortality; however, there was a statistically significant, 12% reduction in the isolation of antibiotic-resistant organisms in cultures.

In the PROPHY-VAP trial, patients with acute brain injury (Glasgow Coma Scale score [GCS ] ≤12) intubated for at least 48 hours in 9 ICUs in France received a single dose of intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g) within 12 hours of intubation.3 There was an 18% absolute risk reduction in VAP from days 2 to 7 post-ventilation.

These trials, involving distinct patient populations and interventions, indicate that antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce VAP risk under specific circumstances, but its effect on overall outcomes is still uncertain. The understanding of prophylactic antibiotics in VAP prevention is rapidly evolving.

References

1. Ehrmann S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(22):2052-2062.

2. Myburgh JA, et al. JAMA. 2022;328(19):1911-1921.

3. Dahyot-Fizelier C, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;S2213-2600(23):00471-X.

Isoniazid Resistance Linked With Tuberculosis Deaths

In 2022, more than 78,000 new cases of tuberculosis (TB) were reported in Brazil, with an incidence of 36.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. According to researchers from the Regional Prospective Observational Research for Tuberculosis (RePORT)-Brazil consortium, the country could improve the control of this infection if all patients were subjected to a sensitivity test capable of early detection of resistance not only to rifampicin, but also to isoniazid, before starting treatment. A study by the consortium published this year in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found that monoresistance to isoniazid predicted unfavorable outcomes at the national level.

Isoniazid is part of the first-choice therapeutic regimen for patients with pulmonary TB. The regimen also includes rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. According to Bruno Andrade, MD, PhD, Afrânio Kritski, MD, PhD, and biotechnologist Mariana Araújo Pereira, PhD, researchers from RePORT International and RePORT-Brazil, this regimen is used during the intensive phase of treatment, which usually lasts for 2 months. It is followed by a maintenance phase of another 4 months, during which isoniazid and rifampicin continue to be administered. When monoresistance to isoniazid is detected, however, the recommendation is to use a regimen containing a quinolone instead of isoniazid.

Suboptimal Sensitivity Testing

Since 2015, Brazil’s Ministry of Health has recommended sensitivity testing for all suspected TB cases. In practice, however, this approach is not carried out in the ideal manner. The three researchers told the Medscape Portuguese edition that, according to data from the National Notifiable Diseases Information System (Sinan) of the Ministry of Health, culture testing is conducted in about 30% of cases. Sensitivity testing to identify resistance to first-line drugs (rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide) and second-line drugs (quinolone and amikacin) is performed in only 12% of cases.

The initiative of the RePORT-Brazil group analyzed 21,197 TB cases registered in Sinan between June 2015 and June 2019 and identified a rate of monoresistance to isoniazid of 1.4%.

For the researchers, the problem of monoresistance to isoniazid in Brazil is still underestimated. This underestimation results from the infrequent performance of culture and sensitivity testing to detect resistance to first- and second-line drugs and because the XPERT MTB RIF test, which detects only rifampicin resistance, is still used.

Resistance and Worse Outcomes

The study also showed that the frequency of unfavorable outcomes in antituberculosis treatment (death or therapeutic failure) was significantly higher among patients with monoresistance to isoniazid (9.1% vs 3.05%).

The finding serves as a warning about the importance of increasing the administration of sensitivity tests to detect resistance to drugs used in tuberculosis treatment, including isoniazid.

Testing sensitivity to rifampicin and isoniazid before starting treatment could transform tuberculosis control in Brazil, allowing for more targeted and effective treatments from the outset, said the researchers. “This not only increases the chances of successful individual treatment but also helps prevent the transmission of resistant strains and develop a more accurate understanding of drug resistance trends,” they emphasized.

They pointed out, however, that implementing this testing in the Unified Health System depends on improvements in resource allocation, coordination between the national TB program and state and municipal programs, and improvements in infrastructure and the technical staff of the Central Public Health Laboratories.

“Although the initial cost is considerable, these investments can be offset by long-term savings resulting from the reduction in the use of more expensive and prolonged treatments for resistant tuberculosis,” said the researchers.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2022, more than 78,000 new cases of tuberculosis (TB) were reported in Brazil, with an incidence of 36.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. According to researchers from the Regional Prospective Observational Research for Tuberculosis (RePORT)-Brazil consortium, the country could improve the control of this infection if all patients were subjected to a sensitivity test capable of early detection of resistance not only to rifampicin, but also to isoniazid, before starting treatment. A study by the consortium published this year in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found that monoresistance to isoniazid predicted unfavorable outcomes at the national level.

Isoniazid is part of the first-choice therapeutic regimen for patients with pulmonary TB. The regimen also includes rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. According to Bruno Andrade, MD, PhD, Afrânio Kritski, MD, PhD, and biotechnologist Mariana Araújo Pereira, PhD, researchers from RePORT International and RePORT-Brazil, this regimen is used during the intensive phase of treatment, which usually lasts for 2 months. It is followed by a maintenance phase of another 4 months, during which isoniazid and rifampicin continue to be administered. When monoresistance to isoniazid is detected, however, the recommendation is to use a regimen containing a quinolone instead of isoniazid.

Suboptimal Sensitivity Testing

Since 2015, Brazil’s Ministry of Health has recommended sensitivity testing for all suspected TB cases. In practice, however, this approach is not carried out in the ideal manner. The three researchers told the Medscape Portuguese edition that, according to data from the National Notifiable Diseases Information System (Sinan) of the Ministry of Health, culture testing is conducted in about 30% of cases. Sensitivity testing to identify resistance to first-line drugs (rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide) and second-line drugs (quinolone and amikacin) is performed in only 12% of cases.

The initiative of the RePORT-Brazil group analyzed 21,197 TB cases registered in Sinan between June 2015 and June 2019 and identified a rate of monoresistance to isoniazid of 1.4%.

For the researchers, the problem of monoresistance to isoniazid in Brazil is still underestimated. This underestimation results from the infrequent performance of culture and sensitivity testing to detect resistance to first- and second-line drugs and because the XPERT MTB RIF test, which detects only rifampicin resistance, is still used.

Resistance and Worse Outcomes

The study also showed that the frequency of unfavorable outcomes in antituberculosis treatment (death or therapeutic failure) was significantly higher among patients with monoresistance to isoniazid (9.1% vs 3.05%).

The finding serves as a warning about the importance of increasing the administration of sensitivity tests to detect resistance to drugs used in tuberculosis treatment, including isoniazid.

Testing sensitivity to rifampicin and isoniazid before starting treatment could transform tuberculosis control in Brazil, allowing for more targeted and effective treatments from the outset, said the researchers. “This not only increases the chances of successful individual treatment but also helps prevent the transmission of resistant strains and develop a more accurate understanding of drug resistance trends,” they emphasized.

They pointed out, however, that implementing this testing in the Unified Health System depends on improvements in resource allocation, coordination between the national TB program and state and municipal programs, and improvements in infrastructure and the technical staff of the Central Public Health Laboratories.

“Although the initial cost is considerable, these investments can be offset by long-term savings resulting from the reduction in the use of more expensive and prolonged treatments for resistant tuberculosis,” said the researchers.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2022, more than 78,000 new cases of tuberculosis (TB) were reported in Brazil, with an incidence of 36.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. According to researchers from the Regional Prospective Observational Research for Tuberculosis (RePORT)-Brazil consortium, the country could improve the control of this infection if all patients were subjected to a sensitivity test capable of early detection of resistance not only to rifampicin, but also to isoniazid, before starting treatment. A study by the consortium published this year in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found that monoresistance to isoniazid predicted unfavorable outcomes at the national level.

Isoniazid is part of the first-choice therapeutic regimen for patients with pulmonary TB. The regimen also includes rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. According to Bruno Andrade, MD, PhD, Afrânio Kritski, MD, PhD, and biotechnologist Mariana Araújo Pereira, PhD, researchers from RePORT International and RePORT-Brazil, this regimen is used during the intensive phase of treatment, which usually lasts for 2 months. It is followed by a maintenance phase of another 4 months, during which isoniazid and rifampicin continue to be administered. When monoresistance to isoniazid is detected, however, the recommendation is to use a regimen containing a quinolone instead of isoniazid.

Suboptimal Sensitivity Testing

Since 2015, Brazil’s Ministry of Health has recommended sensitivity testing for all suspected TB cases. In practice, however, this approach is not carried out in the ideal manner. The three researchers told the Medscape Portuguese edition that, according to data from the National Notifiable Diseases Information System (Sinan) of the Ministry of Health, culture testing is conducted in about 30% of cases. Sensitivity testing to identify resistance to first-line drugs (rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide) and second-line drugs (quinolone and amikacin) is performed in only 12% of cases.

The initiative of the RePORT-Brazil group analyzed 21,197 TB cases registered in Sinan between June 2015 and June 2019 and identified a rate of monoresistance to isoniazid of 1.4%.

For the researchers, the problem of monoresistance to isoniazid in Brazil is still underestimated. This underestimation results from the infrequent performance of culture and sensitivity testing to detect resistance to first- and second-line drugs and because the XPERT MTB RIF test, which detects only rifampicin resistance, is still used.

Resistance and Worse Outcomes

The study also showed that the frequency of unfavorable outcomes in antituberculosis treatment (death or therapeutic failure) was significantly higher among patients with monoresistance to isoniazid (9.1% vs 3.05%).

The finding serves as a warning about the importance of increasing the administration of sensitivity tests to detect resistance to drugs used in tuberculosis treatment, including isoniazid.

Testing sensitivity to rifampicin and isoniazid before starting treatment could transform tuberculosis control in Brazil, allowing for more targeted and effective treatments from the outset, said the researchers. “This not only increases the chances of successful individual treatment but also helps prevent the transmission of resistant strains and develop a more accurate understanding of drug resistance trends,” they emphasized.

They pointed out, however, that implementing this testing in the Unified Health System depends on improvements in resource allocation, coordination between the national TB program and state and municipal programs, and improvements in infrastructure and the technical staff of the Central Public Health Laboratories.

“Although the initial cost is considerable, these investments can be offset by long-term savings resulting from the reduction in the use of more expensive and prolonged treatments for resistant tuberculosis,” said the researchers.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Eradicating uncertainty: A review of Pseudomonas aeruginosa eradication in bronchiectasis

Airways Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis patients have dilated airways that are often colonized with bacteria, resulting in a vicious cycle of airway inflammation and progressive dilation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a frequent airway colonizer and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB).1

Optimal NCFB eradication regimens remain unknown, though recent studies demonstrated inhaled tobramycin is safe and effective for chronic P. aeruginosa infections in NCFB.4

The 2024 meta-analysis by Conceiçã et al. revealed that P. aeruginosa eradication endures more than 12 months in only 40% of NCFB cases, but that patients who received combined therapy—both systemic and inhaled therapies—had a higher eradication rate at 48% compared with 27% in those receiving only systemic antibiotics.5 They found that successful eradication reduced exacerbation rate by 0.91 exacerbations per year without changing hospitalization rate. They were unable to comment on optimal antibiotic selection or duration.

A take-home point from Conceiçã et al. suggests trying to eradicate P. aeruginosa with combined systemic and inhaled antibiotics if possible, but other clinical questions remain around initial antibiotic selection and how to treat persistent P. aeruginosa.

References

1. Finch, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1602-1611.

2. Polverino, et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629.

3. Mogayzel, et al. Ann ATS. 2014;11(10):1511-1761.

4. Guan, et al. CHEST. 2023;163(1):64-76.

5. Conceiçã, et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33:230178.

Airways Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis patients have dilated airways that are often colonized with bacteria, resulting in a vicious cycle of airway inflammation and progressive dilation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a frequent airway colonizer and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB).1

Optimal NCFB eradication regimens remain unknown, though recent studies demonstrated inhaled tobramycin is safe and effective for chronic P. aeruginosa infections in NCFB.4

The 2024 meta-analysis by Conceiçã et al. revealed that P. aeruginosa eradication endures more than 12 months in only 40% of NCFB cases, but that patients who received combined therapy—both systemic and inhaled therapies—had a higher eradication rate at 48% compared with 27% in those receiving only systemic antibiotics.5 They found that successful eradication reduced exacerbation rate by 0.91 exacerbations per year without changing hospitalization rate. They were unable to comment on optimal antibiotic selection or duration.

A take-home point from Conceiçã et al. suggests trying to eradicate P. aeruginosa with combined systemic and inhaled antibiotics if possible, but other clinical questions remain around initial antibiotic selection and how to treat persistent P. aeruginosa.

References

1. Finch, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1602-1611.

2. Polverino, et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629.

3. Mogayzel, et al. Ann ATS. 2014;11(10):1511-1761.

4. Guan, et al. CHEST. 2023;163(1):64-76.

5. Conceiçã, et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33:230178.

Airways Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis patients have dilated airways that are often colonized with bacteria, resulting in a vicious cycle of airway inflammation and progressive dilation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a frequent airway colonizer and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB).1

Optimal NCFB eradication regimens remain unknown, though recent studies demonstrated inhaled tobramycin is safe and effective for chronic P. aeruginosa infections in NCFB.4

The 2024 meta-analysis by Conceiçã et al. revealed that P. aeruginosa eradication endures more than 12 months in only 40% of NCFB cases, but that patients who received combined therapy—both systemic and inhaled therapies—had a higher eradication rate at 48% compared with 27% in those receiving only systemic antibiotics.5 They found that successful eradication reduced exacerbation rate by 0.91 exacerbations per year without changing hospitalization rate. They were unable to comment on optimal antibiotic selection or duration.

A take-home point from Conceiçã et al. suggests trying to eradicate P. aeruginosa with combined systemic and inhaled antibiotics if possible, but other clinical questions remain around initial antibiotic selection and how to treat persistent P. aeruginosa.

References

1. Finch, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1602-1611.

2. Polverino, et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629.

3. Mogayzel, et al. Ann ATS. 2014;11(10):1511-1761.

4. Guan, et al. CHEST. 2023;163(1):64-76.

5. Conceiçã, et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33:230178.

Centrifugally Spreading Lymphocutaneous Sporotrichosis: A Rare Cutaneous Manifestation

To the Editor:

Sporotrichosis refers to a subacute to chronic fungal infection that usually involves the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues and is caused by the introduction of Sporothrix, a dimorphic fungus, through the skin. We present a case of chronic atypical lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.

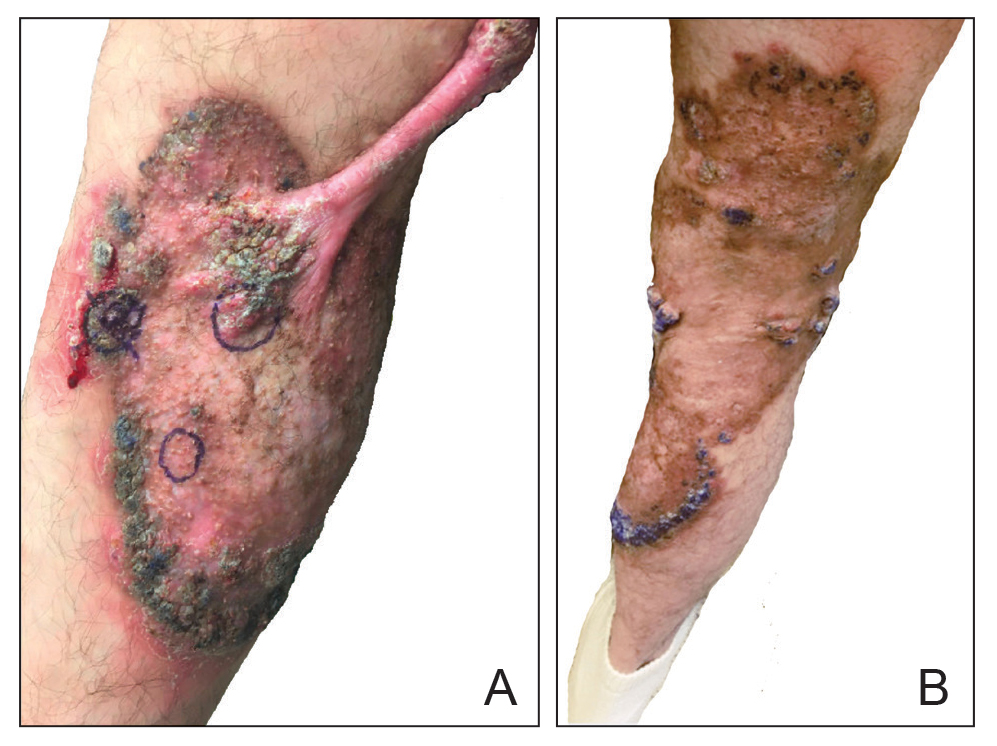

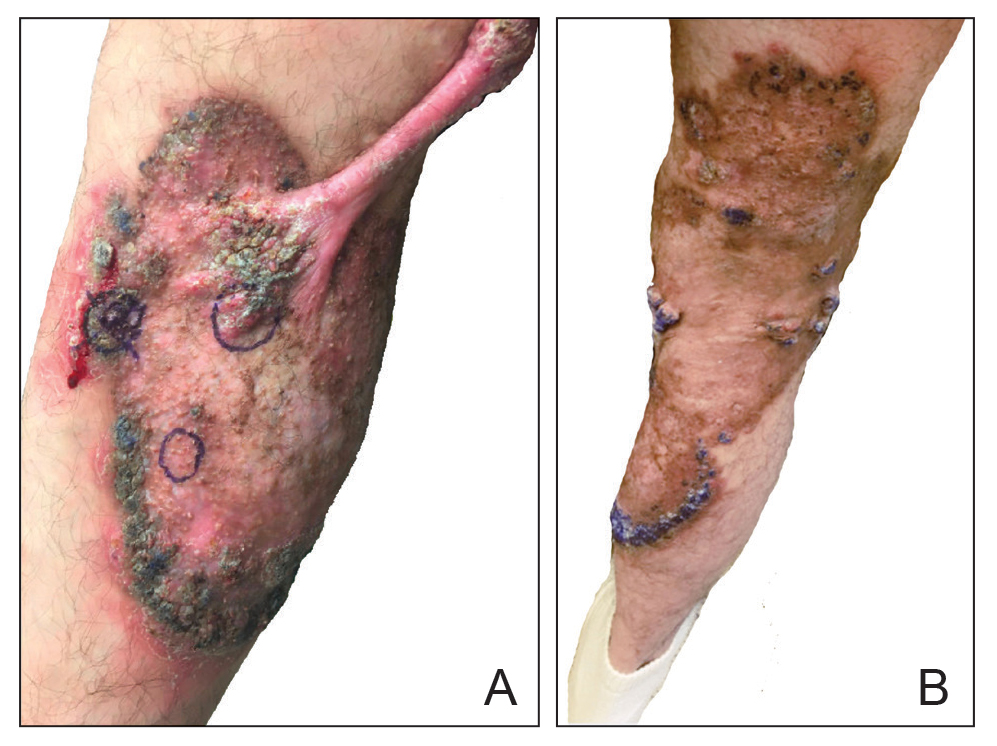

A 46-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic for follow-up for a rash on the right leg that spread to the thigh and became painful and pruritic. It initially developed 8 years prior to the current presentation after he sustained trauma to the leg from an electroshock weapon. One year prior to the current presentation, he had presented to the emergency department and was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days as well as bacitracin ointment. He also was instructed to follow up with dermatology, but a lack of health insurance and other socioeconomic barriers prevented him from seeking dermatologic care. Nine months later, he again presented to the emergency department due to a motor vehicle accident. Computed tomography (CT) of the right leg revealed exophytic dermal masses, inflammatory stranding of the subcutaneous tissue, and right inguinal lymph nodes measuring up to 1.4 cm; there was no osteoarticular involvement. At that time, the patient was applying gentian violet to the skin lesions and taking hydroxyzine 50 mg 3 times daily as needed for pruritus with minimal relief. Financial support was provided for follow-up with dermatology, which occurred almost 5 months later.

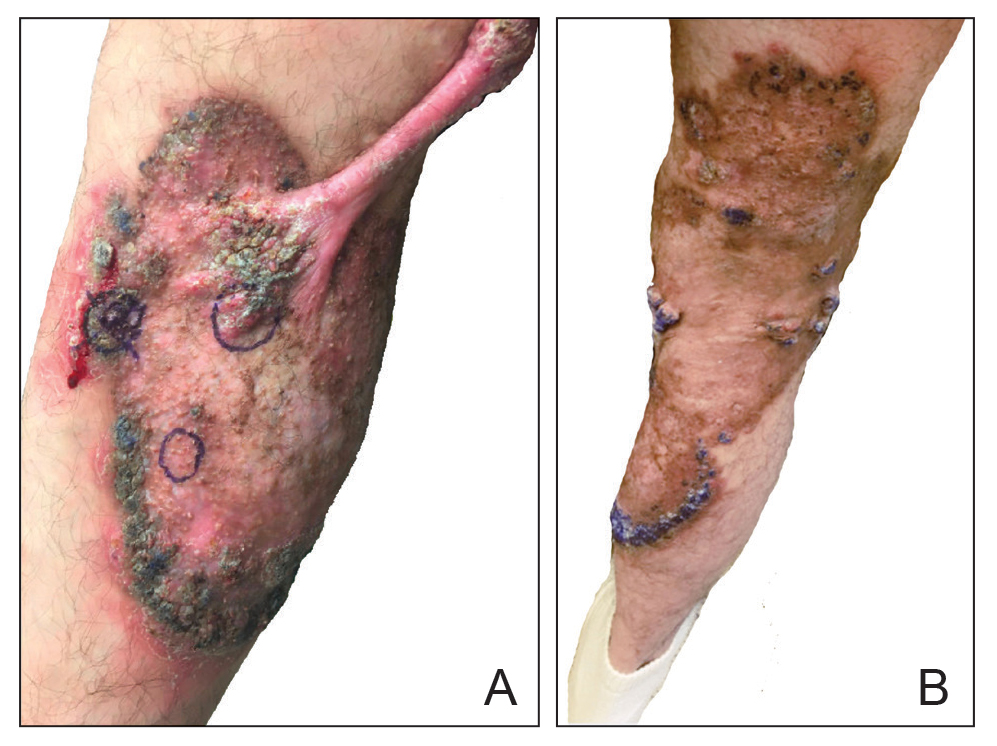

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed a large annular plaque with verrucous, scaly, erythematous borders and a hypopigmented atrophic center extending from the medial aspect of the right leg to the posterior thigh. Numerous pink, scaly, crusted nodules were scattered primarily along the periphery, with some evidence of draining sinus tracts. In addition, a fibrotic pink linear plaque extended from the medial right leg to the popliteal fossa, consistent with a keloid. Violet staining along the periphery of the lesion also was appreciated secondary to the application of topical gentian violet (Figure 1).

Based on the chronic history and morphology, a diagnosis of a chronic fungal or atypical mycobacterial infection was favored. In particular, chromoblastomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis (eg, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis), and atypical mycobacterial infection were highest on the differential, as these conditions often exhibit annular, nodular, verrucous, and/or atrophic lesions. The nodularity, crusting, and draining sinus tracts also raised the possibility of mycetoma. Given the extension of the lesion from the lower to upper leg, a sporotrichoid infection also was considered but was thought to be less likely based on the annular configuration.

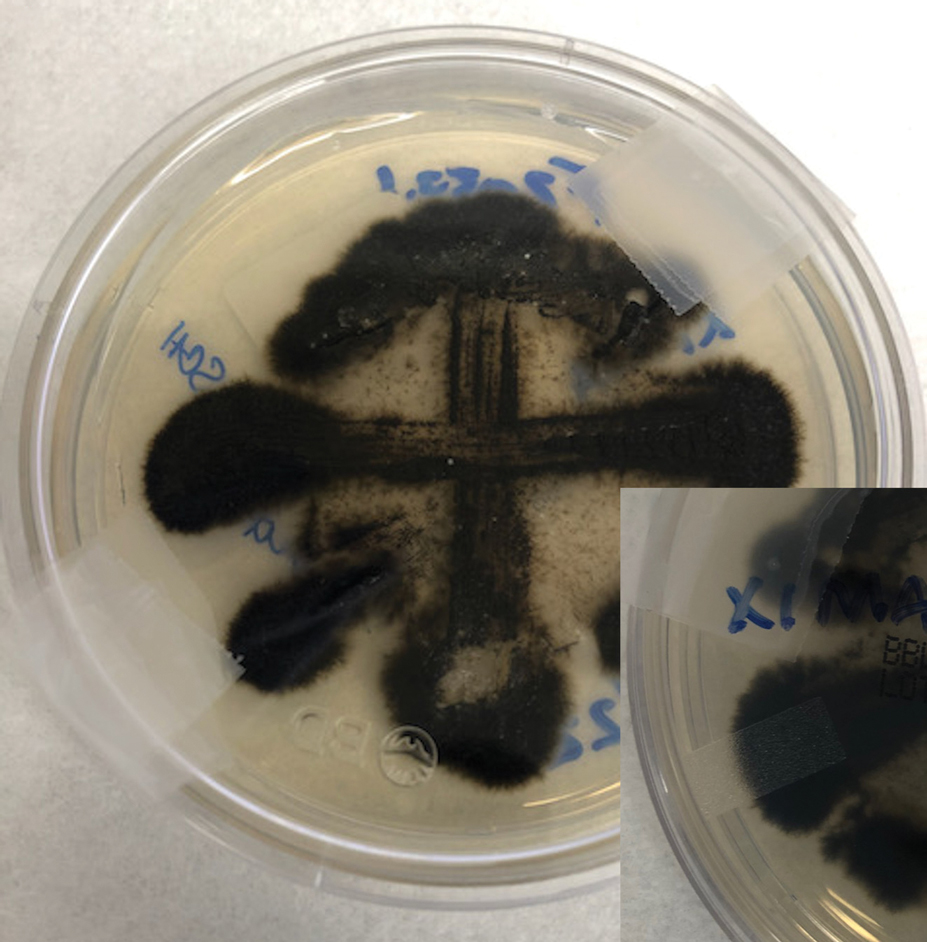

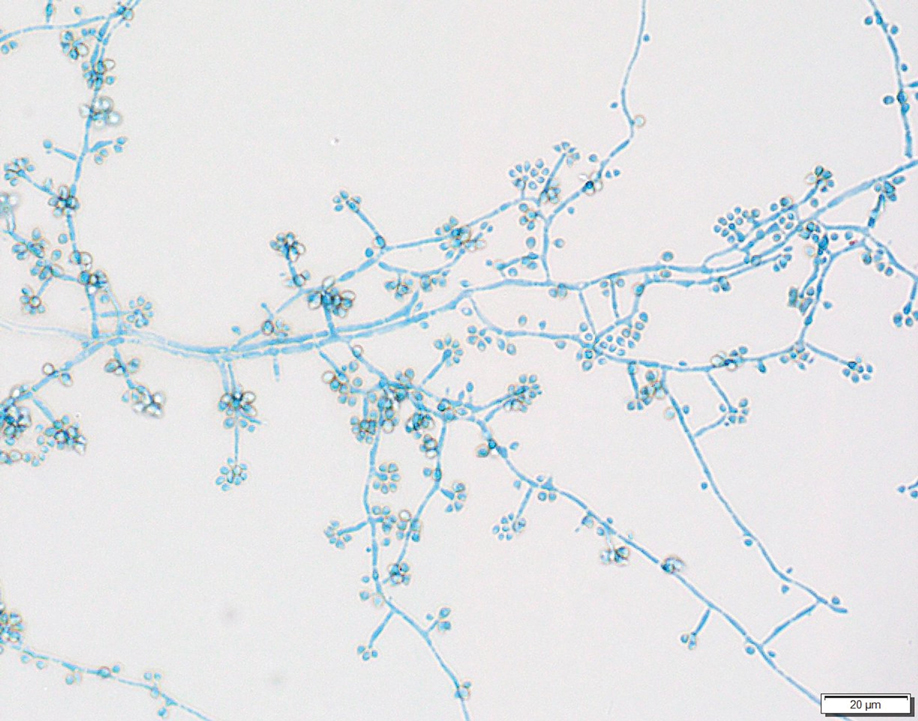

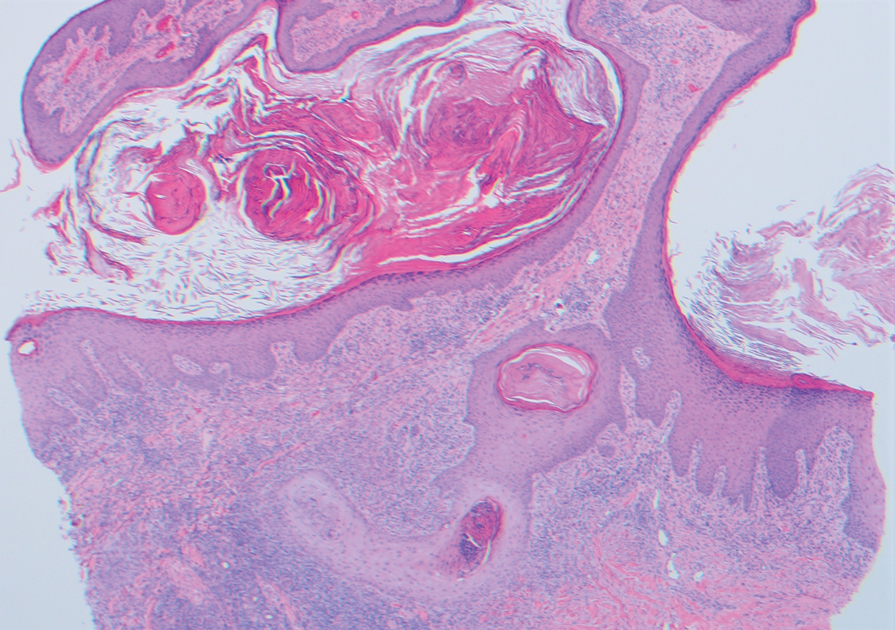

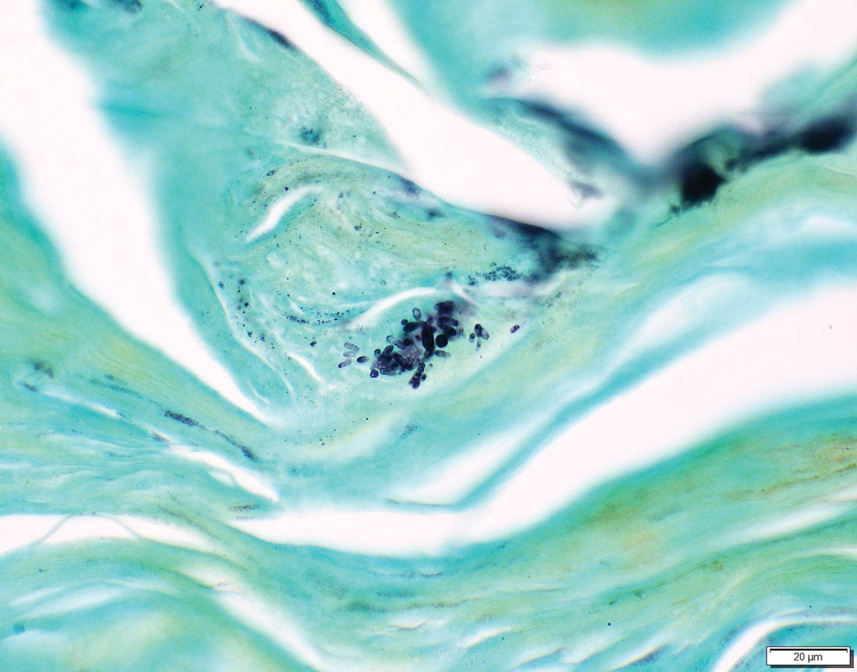

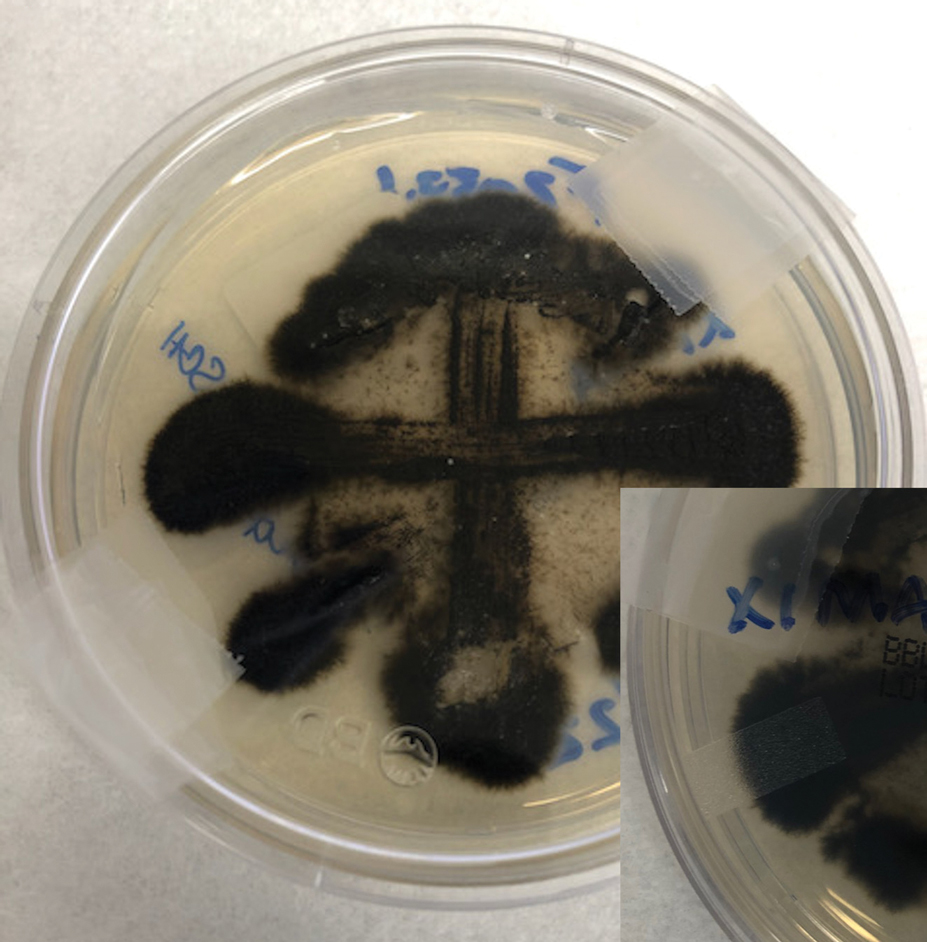

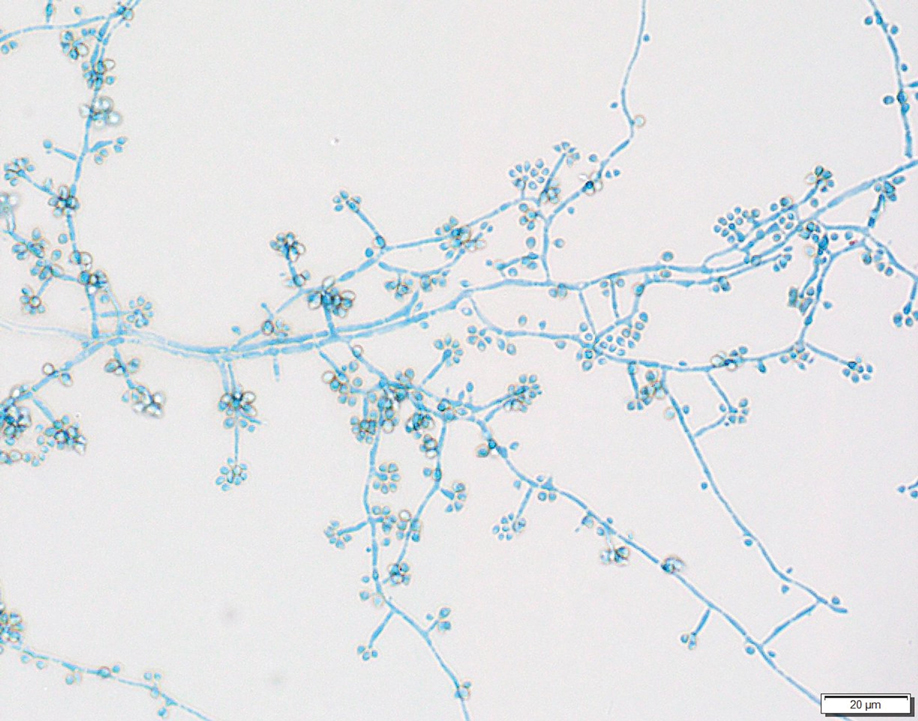

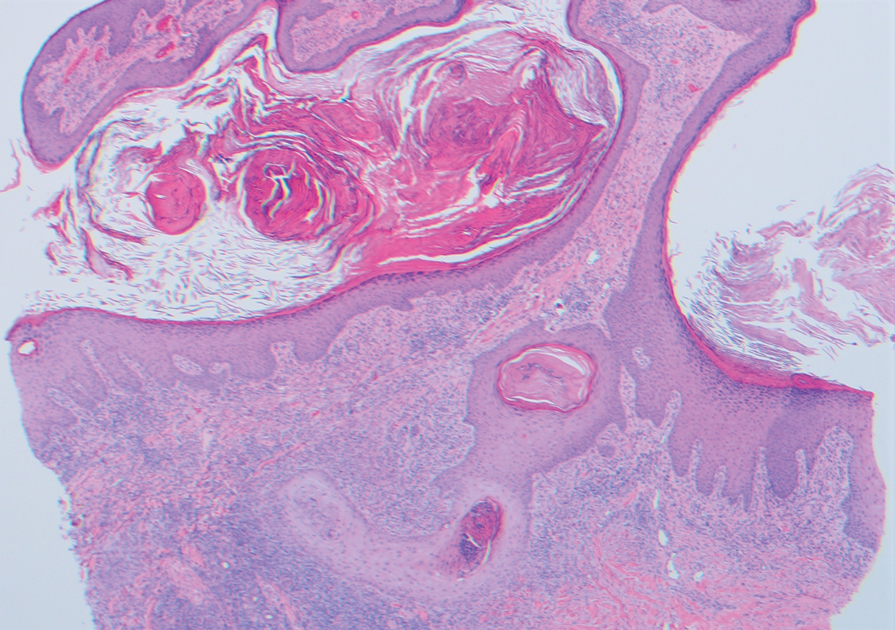

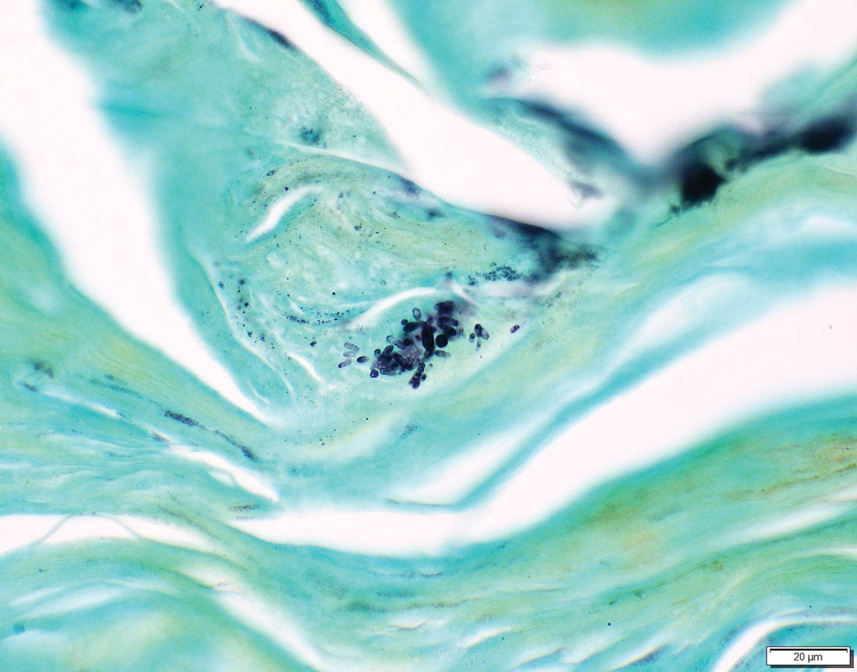

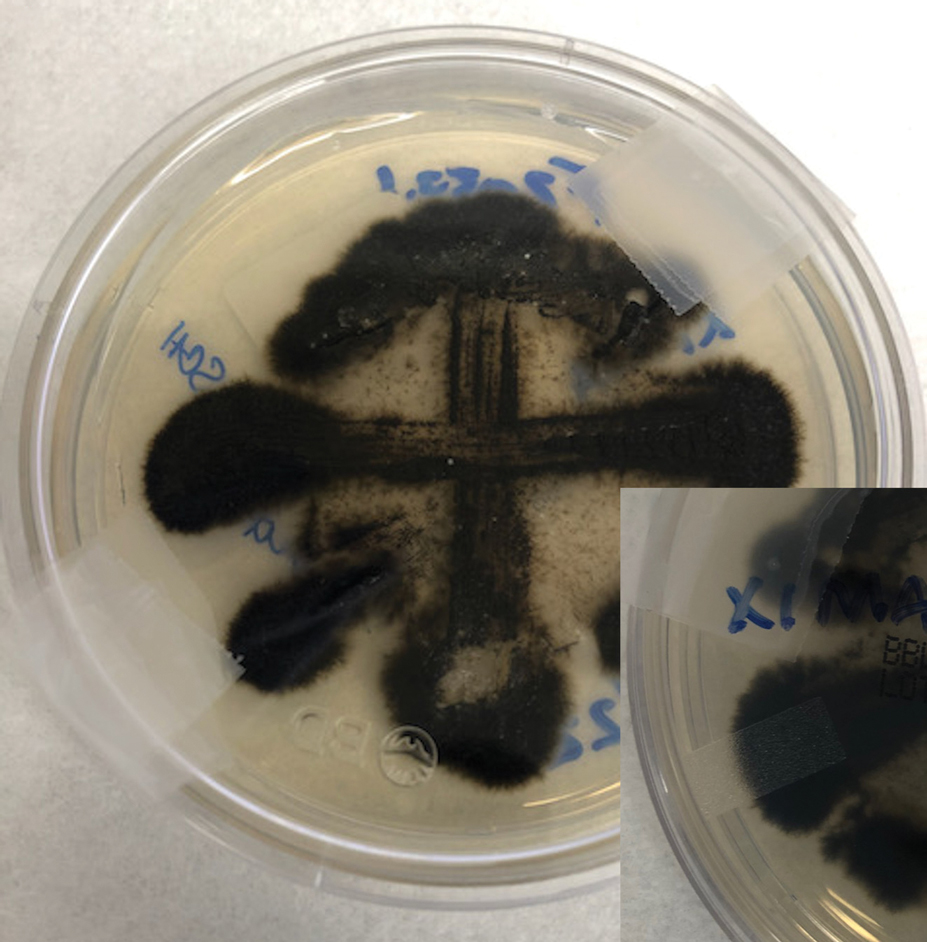

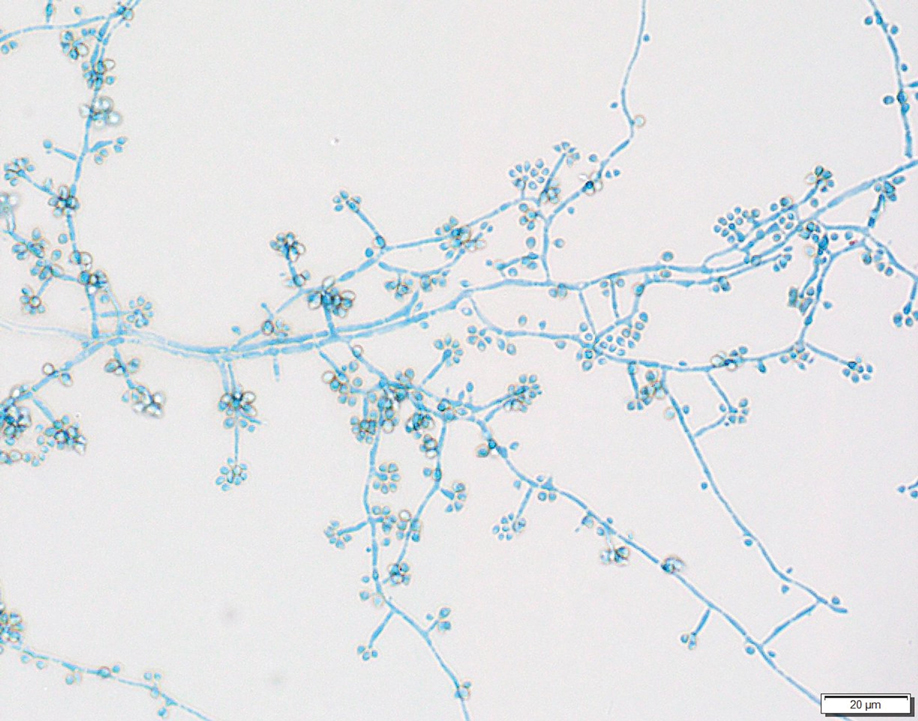

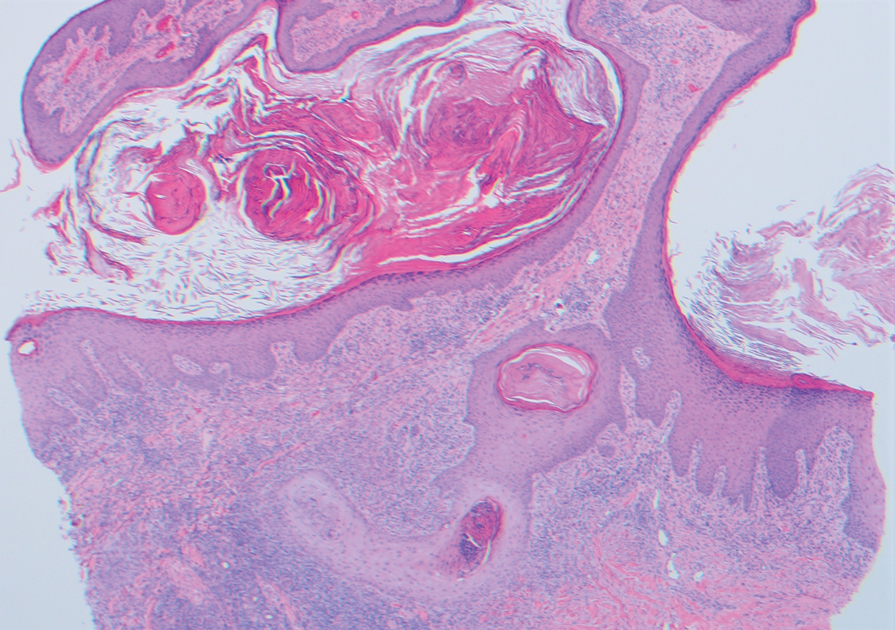

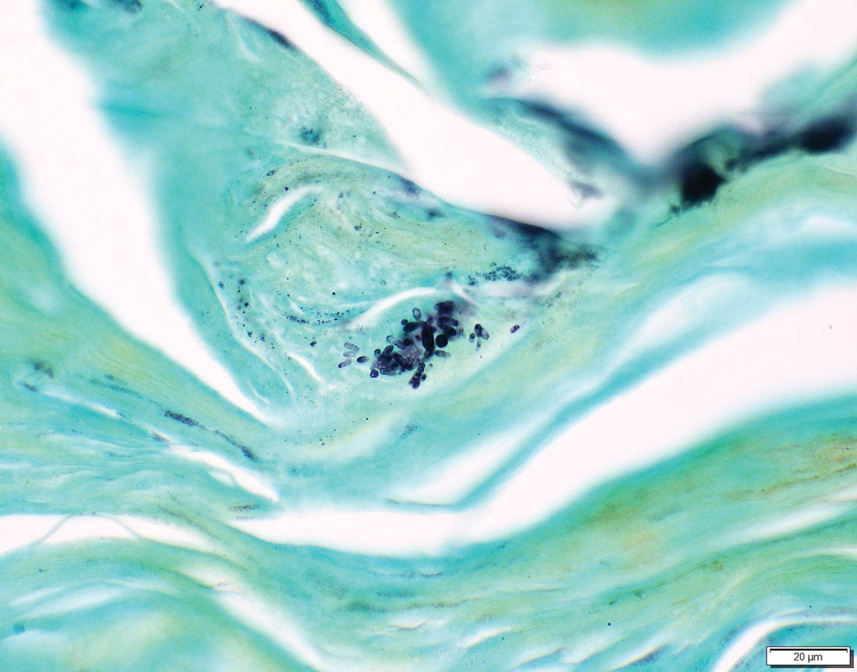

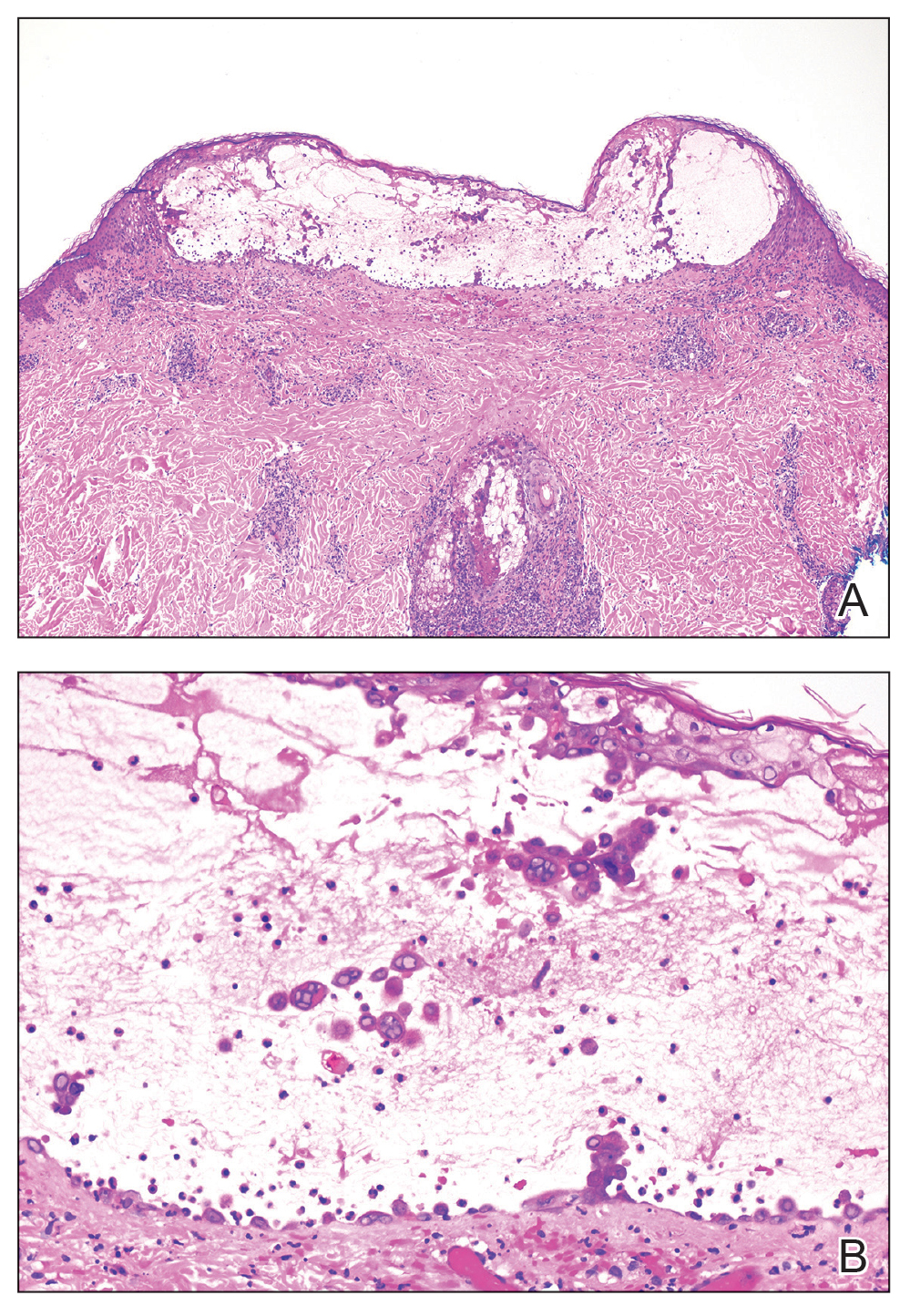

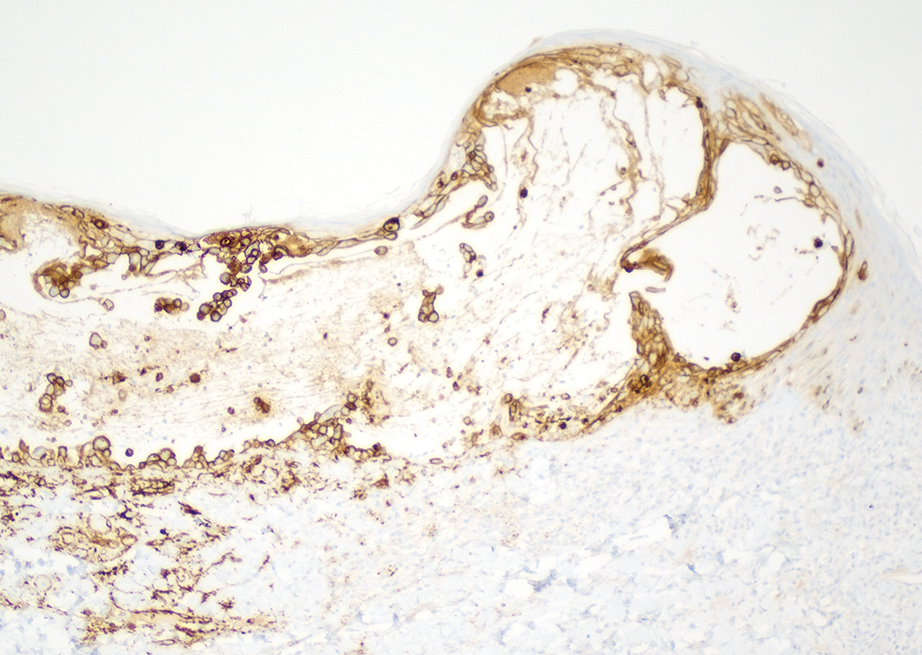

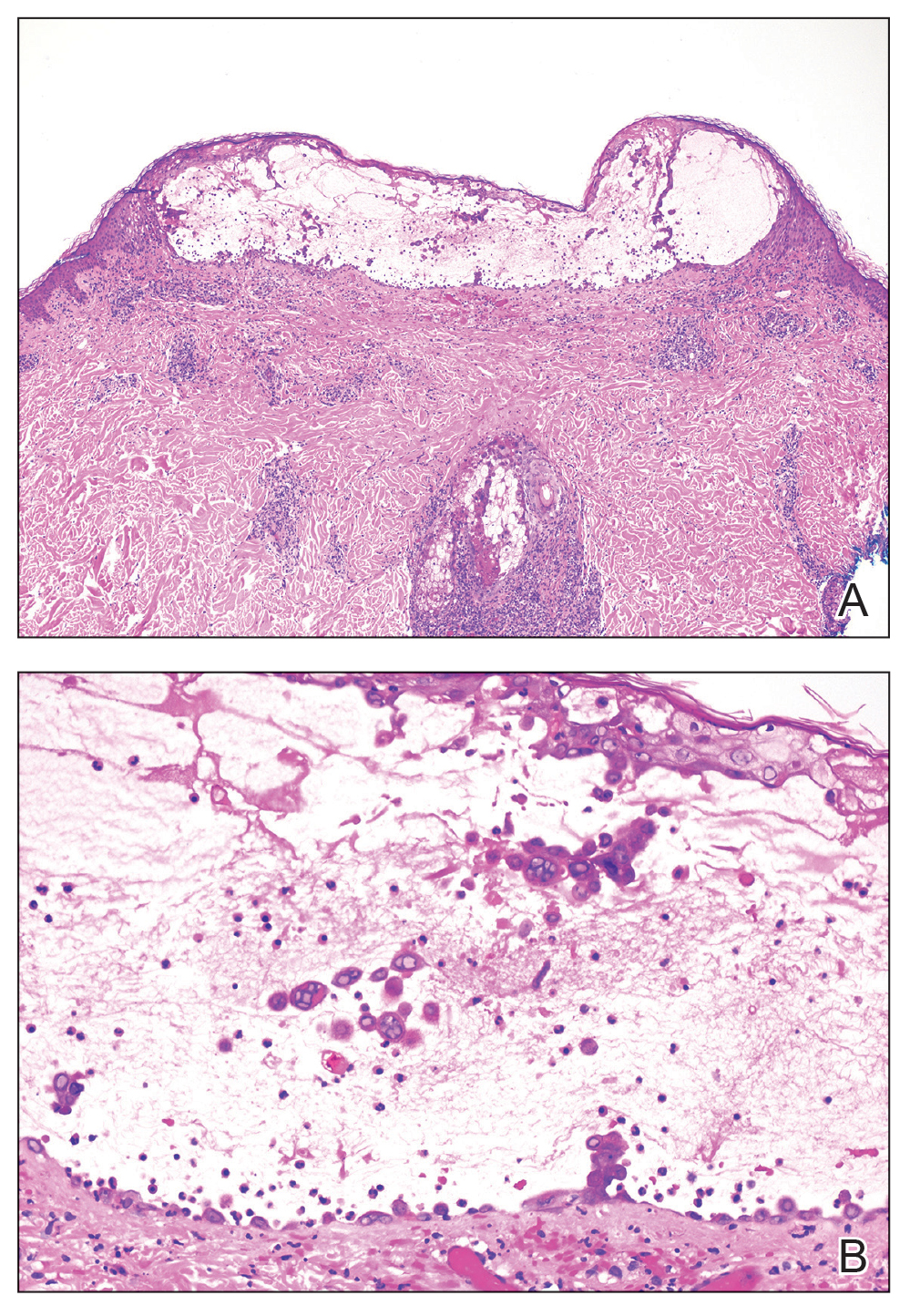

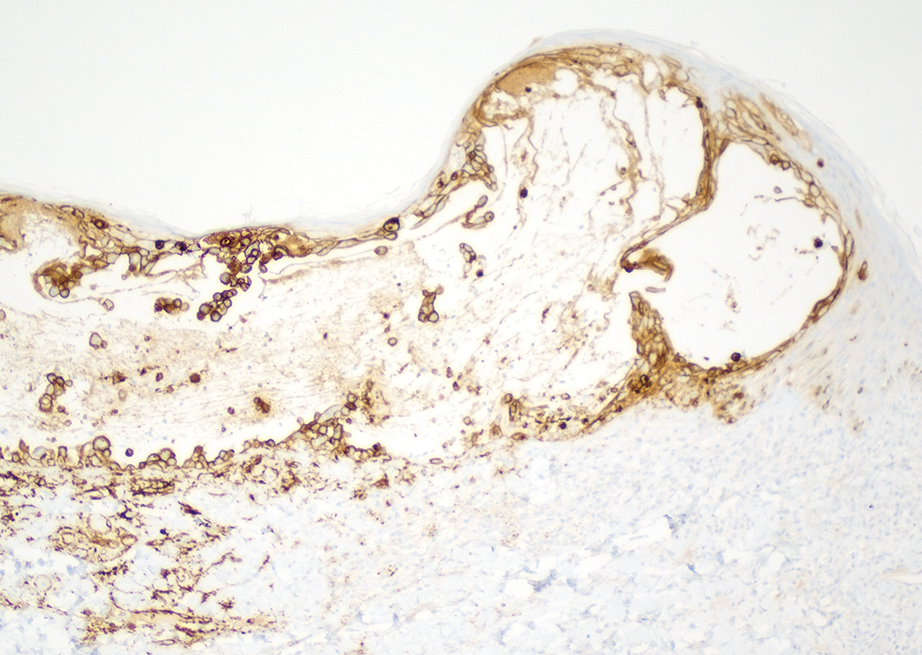

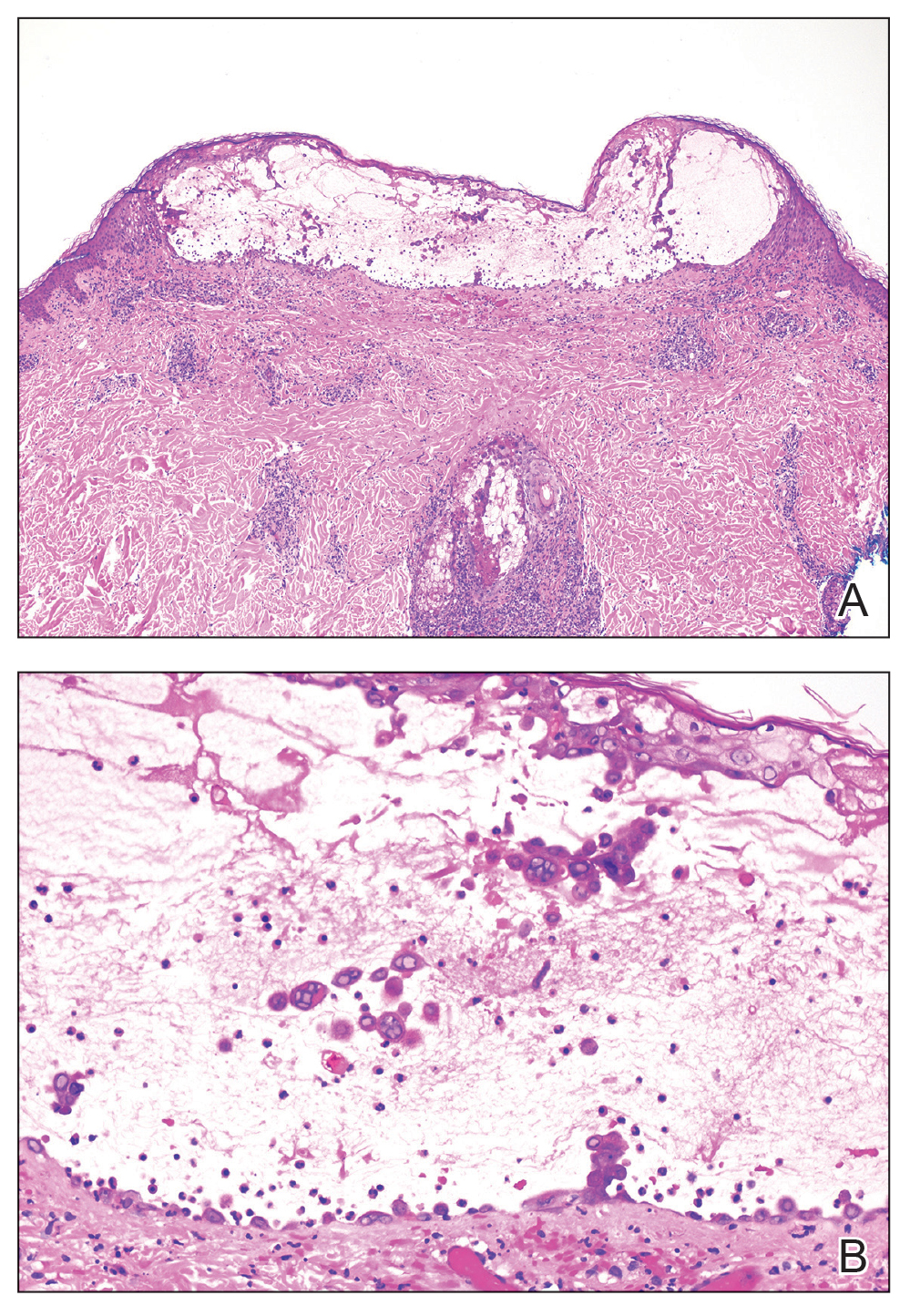

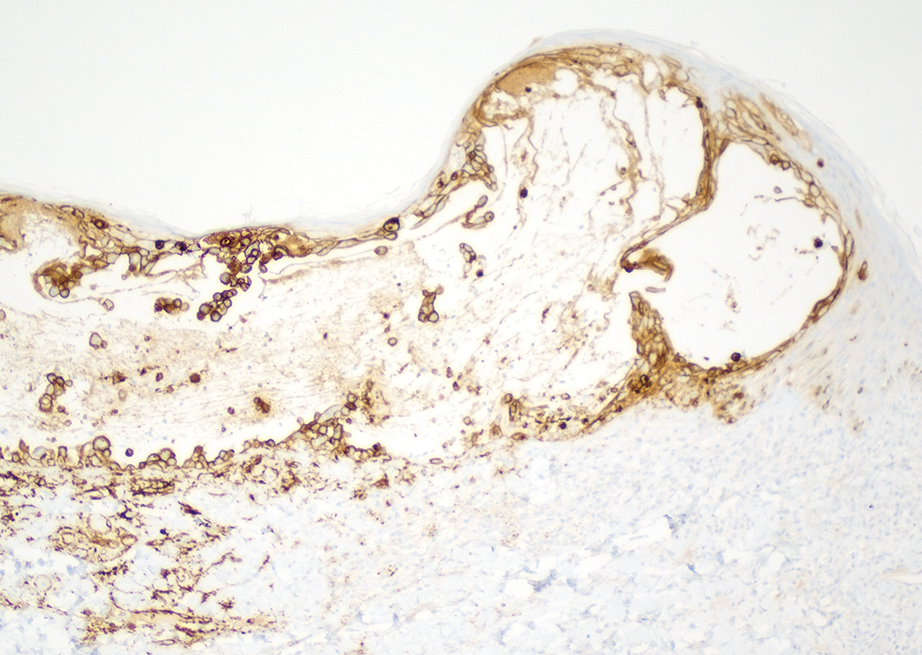

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were taken from a peripheral nodule—one for routine histology and another for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. An interferon-gamma release assay also was ordered to evaluate for immune responses indicative of prior Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, but the patient did not obtain this for unknown reasons. Histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and necrotizing granulomas, which suggested an infectious etiology, but no organisms were identified on tissue staining and all cultures were negative for growth at 6 weeks. The patient was asked to return at that point, and 4 additional scouting biopsies were performed and sent for routine histology, M tuberculosis nucleic acid amplification testing, and microbiologic cultures (ie, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, nocardia, actinomycetes). Within 1 week, a filamentous organism with pigmentation visible on the front and back of a Sabouraud dextrose agar plate was identified on fungal culture (Figure 2). Microscopic evaluation of this mold with lactophenol blue stain revealed thin septate hyphae with conidiophores arising at right angles that bore clusters of microconidia (Figure 3). Sequencing analysis ultimately identified this organism as Sporothrix schenckii. Routine histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with scattered intraepidermal collections of neutrophils (Figure 4). The dermis showed a dense, superficial, and deep infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells with occasional neutrophils and eosinophils. A Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain revealed a cluster of ovoid yeast forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 5). The patient was referred to infectious disease for follow-up and treatment.

The patient later visited a community clinic providing dermatologic care for patients without insurance. He was started on itraconazole 200 mg daily for a total of 6 months until dermatologic clearance of the cutaneous lesions was observed. He was followed by the clinic with laboratory tests including a liver function test. At follow-up 8 months later, a repeat biopsy was performed to ensure histologic clearance of the sporotrichosis, which revealed a dermal scar and no evidence of residual infection.

Sporothrix schenckii was first isolated in 1898 by Benjamin Schenck, a student at Johns Hopkins Medicine (Baltimore, Maryland), and identified by a mycologist as sporotricha.1 Species within the genus Sporothrix are unique in that the fungi are both dimorphic (growing as a mold at 25 °C but as a yeast at 37 °C) and dematiaceous (dark pigmentation from melanin is visible on inspection of the anterior and reverse sides of culture plates). Infection usually occurs when cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues are exposed to the fungus via microabrasions; activities thought to contribute to exposure include gardening, agricultural work, animal husbandry, and feline scratches.2 Although skin trauma frequently is considered the primary route of infection, patient recall is variable, with one study noting that only 37.7% of patients recalled trauma and another study similarly demonstrating a patient recall rate of 25%.3,4

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is the most common presentation of the fungal infection,5 and clinical cases may be classified into 1 of 4 categories: (1) lymphangitic lesions—papules at the site of inoculation with spread along the lymphatic channels; (2) localized (fixed) cutaneous lesions—1 or 2 lesions at the inoculation site; (3) disseminated (multifocal) cutaneous lesions; and (4) extracutaneous lesions.6 Extracutaneous manifestations of this infection most notably have been reported as pulmonary disease through inhalation of conidia or through dissemination in immunocompromised hosts.7 Our patient’s infection was categorized as lymphangitic lesions due to spread from the lower to upper leg, albeit in a highly atypical, annular fashion. A review of systems was otherwise negative, and CT ruled out osteoarticular involvement.

In addition to socioeconomic barriers, several factors contributed to a delayed diagnosis in this patient including the annular presentation with central hypopigmentation and atrophy, negative initial microbiological cultures and lack of visualization of organisms on histopathology, and the consequent need for repeat biopsies. For lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the typical presentation consists of a papule or ulcerated nodule at the site of inoculation with subsequent linear spread along lymphatic channels. This classic sporotrichoid pattern is a key diagnostic clue for identifying sporotrichosis but was absent at the time our patient presented for medical care. Rather, the sporotrichoid spread seemed to have occurred in a centrifugal fashion up the leg. Few case reports have documented an annular presentation of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis,8-13 and one report described central atrophy and hypopigmentation.10 Pain and pruritus, which were present in our patient, rarely are documented.9 Finally, the diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infections may require multiple biopsies due to the variable abundance of viable organisms in tissue specimens as well as the fastidious growth characteristics of these organisms. Furthermore, sensitivity often is low for both fungal and mycobacterial cultures, and cultures may take days to weeks to yield growth.14,15 For these reasons, empiric therapy and repeat biopsies often are pursued if clinical suspicion is high enough.16 Our patient returned for multiple scouting biopsies after the initial tissue culture was negative and was even considered for empiric treatment against Mycobacterium prior to positive fungal cultures.

Another unique aspect of our case was the presence of a keloid. It is difficult to know if this keloid was secondary to the trauma the patient sustained in the inciting incident or formed from the fungal infection. Interestingly, it has been hypothesized that fungal infections may contribute to keloid and hypertrophic scar formation.17 In a case series of 3 patients with either keloids or hypertrophic scars and concomitant tinea infection, there was notable improvement in the appearance of the scars 2 weeks after beginning itraconazole therapy.17 However, it is not yet known if a fungal infection can contribute to the pathogenesis of keloid formation.

As with other aspects of this case, the length of time the patient went without diagnosis and treatment was unusual and may help explain the atypical presentation. Although the incubation period for S schenckii can vary, most reports identify patients as seeking medical attention within 1 year of rash onset.18-20 In our case, the patient was not diagnosed until 8 years after his symptoms began, requiring multiple referrals, multiple health system touchpoints, and an institution-specific financial aid program. As such, this case also highlights the potential need for a multidisciplinary team approach when caring for patients with poor access to health care.

In conclusion, this case illustrates a unique presentation of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis that may mimic other chronic infections and result in delayed diagnosis. Although lymphangitic sporotrichosis generally is recognized as having a linear distribution, mounting evidence from this report and others suggests an annular presentation also is possible. Pruritus or pain is rare but should not preclude a diagnosis of sporotrichosis if present. For patients with limited access to health care resources, it is especially important to involve multiple members of the health care team, including social workers and specialists, to prevent a protracted and severe course of disease.

- Schenck BR. On refractory subcutaneous abscesses caused by a fungus possibly related to the sporotricha. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1898;93:286-290.

- de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:633-654. doi:10.1128/CMR.00007-11

- Crevasse L, Ellner PD. An outbreak of sporotrichosis in florida. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;173:29-33. doi:10.1001/jama.1960.03020190031006

- Mayorga R, Cáceres A, Toriello C, et al. An endemic area of sporotrichosis in Guatemala [in French]. Sabouraudia. 1978;16:185-198.

- Morris-Jones R. Sporotrichosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:427-431. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01087.x

- Sampaio SA, Da Lacaz CS. Clinical and statistical studies on sporotrichosis in Sao Paulo (Brazil). Article in German. Hautarzt. 1959;10:490-493.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Vasconcelos C, Carneiro S, et al. Sporotrichosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:181-187. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.006

- Williams BA, Jennings TA, Rushing EC, et al. Sporotrichosis on the face of a 7-year-old boy following a bicycle accident. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E246-E247. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01696.x

- Vaishampayan SS, Borde P. An unusual presentation of sporotrichosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.117350

- Qin J, Zhang J. Sporotrichosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:771. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1809179

- Patel A, Mudenda V, Lakhi S, et al. A 27-year-old severely immunosuppressed female with misleading clinical features of disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:1-4. doi:10.1155/2016/9403690

- de Oliveira-Esteves ICMR, Almeida Rosa da Silva G, Eyer-Silva WA, et al. Rapidly progressive disseminated sporotrichosis as the first presentation of HIV infection in a patient with a very low CD4 cell count. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2017;2017:4713140. doi:10.1155/2017/4713140

- Singh S, Bachaspatimayum R, Meetei U, et al. Terbinafine in fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis: a case series. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2018;12:FR01-FR03. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2018/25315.12223

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280. doi:10.1128/CMR.00053-10

- Peters F, Batinica M, Plum G, et al. Bug or no bug: challenges in diagnosing cutaneous mycobacterial infections. J Ger Soc Dermatol. 2016;14:1227-1236. doi:10.1111/ddg.13001

- Khadka P, Koirala S, Thapaliya J. Cutaneous tuberculosis: clinicopathologic arrays and diagnostic challenges. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:7201973. doi:10.1155/2018/7201973

- Okada E, Maruyama Y. Are keloids and hypertrophic scars caused by fungal infection? . Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:814-815. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000278813.23244.3f

- Pappas PG, Tellez I, Deep AE, et al. Sporotrichosis in Peru: description of an area of hyperendemicity. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:65-70. doi:10.1086/313607

- McGuinness SL, Boyd R, Kidd S, et al. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of cutaneous sporotrichosis, Northern Territory, Australia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:1-7. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1338-0

- Rojas FD, Fernández MS, Lucchelli JM, et al. Cavitary pulmonary sporotrichosis: case report and literature review. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:1119-1123. doi:10.1007/s11046-017-0197-6

To the Editor:

Sporotrichosis refers to a subacute to chronic fungal infection that usually involves the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues and is caused by the introduction of Sporothrix, a dimorphic fungus, through the skin. We present a case of chronic atypical lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.

A 46-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic for follow-up for a rash on the right leg that spread to the thigh and became painful and pruritic. It initially developed 8 years prior to the current presentation after he sustained trauma to the leg from an electroshock weapon. One year prior to the current presentation, he had presented to the emergency department and was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days as well as bacitracin ointment. He also was instructed to follow up with dermatology, but a lack of health insurance and other socioeconomic barriers prevented him from seeking dermatologic care. Nine months later, he again presented to the emergency department due to a motor vehicle accident. Computed tomography (CT) of the right leg revealed exophytic dermal masses, inflammatory stranding of the subcutaneous tissue, and right inguinal lymph nodes measuring up to 1.4 cm; there was no osteoarticular involvement. At that time, the patient was applying gentian violet to the skin lesions and taking hydroxyzine 50 mg 3 times daily as needed for pruritus with minimal relief. Financial support was provided for follow-up with dermatology, which occurred almost 5 months later.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed a large annular plaque with verrucous, scaly, erythematous borders and a hypopigmented atrophic center extending from the medial aspect of the right leg to the posterior thigh. Numerous pink, scaly, crusted nodules were scattered primarily along the periphery, with some evidence of draining sinus tracts. In addition, a fibrotic pink linear plaque extended from the medial right leg to the popliteal fossa, consistent with a keloid. Violet staining along the periphery of the lesion also was appreciated secondary to the application of topical gentian violet (Figure 1).

Based on the chronic history and morphology, a diagnosis of a chronic fungal or atypical mycobacterial infection was favored. In particular, chromoblastomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis (eg, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis), and atypical mycobacterial infection were highest on the differential, as these conditions often exhibit annular, nodular, verrucous, and/or atrophic lesions. The nodularity, crusting, and draining sinus tracts also raised the possibility of mycetoma. Given the extension of the lesion from the lower to upper leg, a sporotrichoid infection also was considered but was thought to be less likely based on the annular configuration.

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were taken from a peripheral nodule—one for routine histology and another for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. An interferon-gamma release assay also was ordered to evaluate for immune responses indicative of prior Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, but the patient did not obtain this for unknown reasons. Histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and necrotizing granulomas, which suggested an infectious etiology, but no organisms were identified on tissue staining and all cultures were negative for growth at 6 weeks. The patient was asked to return at that point, and 4 additional scouting biopsies were performed and sent for routine histology, M tuberculosis nucleic acid amplification testing, and microbiologic cultures (ie, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, nocardia, actinomycetes). Within 1 week, a filamentous organism with pigmentation visible on the front and back of a Sabouraud dextrose agar plate was identified on fungal culture (Figure 2). Microscopic evaluation of this mold with lactophenol blue stain revealed thin septate hyphae with conidiophores arising at right angles that bore clusters of microconidia (Figure 3). Sequencing analysis ultimately identified this organism as Sporothrix schenckii. Routine histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with scattered intraepidermal collections of neutrophils (Figure 4). The dermis showed a dense, superficial, and deep infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells with occasional neutrophils and eosinophils. A Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain revealed a cluster of ovoid yeast forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 5). The patient was referred to infectious disease for follow-up and treatment.

The patient later visited a community clinic providing dermatologic care for patients without insurance. He was started on itraconazole 200 mg daily for a total of 6 months until dermatologic clearance of the cutaneous lesions was observed. He was followed by the clinic with laboratory tests including a liver function test. At follow-up 8 months later, a repeat biopsy was performed to ensure histologic clearance of the sporotrichosis, which revealed a dermal scar and no evidence of residual infection.

Sporothrix schenckii was first isolated in 1898 by Benjamin Schenck, a student at Johns Hopkins Medicine (Baltimore, Maryland), and identified by a mycologist as sporotricha.1 Species within the genus Sporothrix are unique in that the fungi are both dimorphic (growing as a mold at 25 °C but as a yeast at 37 °C) and dematiaceous (dark pigmentation from melanin is visible on inspection of the anterior and reverse sides of culture plates). Infection usually occurs when cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues are exposed to the fungus via microabrasions; activities thought to contribute to exposure include gardening, agricultural work, animal husbandry, and feline scratches.2 Although skin trauma frequently is considered the primary route of infection, patient recall is variable, with one study noting that only 37.7% of patients recalled trauma and another study similarly demonstrating a patient recall rate of 25%.3,4

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is the most common presentation of the fungal infection,5 and clinical cases may be classified into 1 of 4 categories: (1) lymphangitic lesions—papules at the site of inoculation with spread along the lymphatic channels; (2) localized (fixed) cutaneous lesions—1 or 2 lesions at the inoculation site; (3) disseminated (multifocal) cutaneous lesions; and (4) extracutaneous lesions.6 Extracutaneous manifestations of this infection most notably have been reported as pulmonary disease through inhalation of conidia or through dissemination in immunocompromised hosts.7 Our patient’s infection was categorized as lymphangitic lesions due to spread from the lower to upper leg, albeit in a highly atypical, annular fashion. A review of systems was otherwise negative, and CT ruled out osteoarticular involvement.

In addition to socioeconomic barriers, several factors contributed to a delayed diagnosis in this patient including the annular presentation with central hypopigmentation and atrophy, negative initial microbiological cultures and lack of visualization of organisms on histopathology, and the consequent need for repeat biopsies. For lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the typical presentation consists of a papule or ulcerated nodule at the site of inoculation with subsequent linear spread along lymphatic channels. This classic sporotrichoid pattern is a key diagnostic clue for identifying sporotrichosis but was absent at the time our patient presented for medical care. Rather, the sporotrichoid spread seemed to have occurred in a centrifugal fashion up the leg. Few case reports have documented an annular presentation of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis,8-13 and one report described central atrophy and hypopigmentation.10 Pain and pruritus, which were present in our patient, rarely are documented.9 Finally, the diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infections may require multiple biopsies due to the variable abundance of viable organisms in tissue specimens as well as the fastidious growth characteristics of these organisms. Furthermore, sensitivity often is low for both fungal and mycobacterial cultures, and cultures may take days to weeks to yield growth.14,15 For these reasons, empiric therapy and repeat biopsies often are pursued if clinical suspicion is high enough.16 Our patient returned for multiple scouting biopsies after the initial tissue culture was negative and was even considered for empiric treatment against Mycobacterium prior to positive fungal cultures.

Another unique aspect of our case was the presence of a keloid. It is difficult to know if this keloid was secondary to the trauma the patient sustained in the inciting incident or formed from the fungal infection. Interestingly, it has been hypothesized that fungal infections may contribute to keloid and hypertrophic scar formation.17 In a case series of 3 patients with either keloids or hypertrophic scars and concomitant tinea infection, there was notable improvement in the appearance of the scars 2 weeks after beginning itraconazole therapy.17 However, it is not yet known if a fungal infection can contribute to the pathogenesis of keloid formation.

As with other aspects of this case, the length of time the patient went without diagnosis and treatment was unusual and may help explain the atypical presentation. Although the incubation period for S schenckii can vary, most reports identify patients as seeking medical attention within 1 year of rash onset.18-20 In our case, the patient was not diagnosed until 8 years after his symptoms began, requiring multiple referrals, multiple health system touchpoints, and an institution-specific financial aid program. As such, this case also highlights the potential need for a multidisciplinary team approach when caring for patients with poor access to health care.

In conclusion, this case illustrates a unique presentation of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis that may mimic other chronic infections and result in delayed diagnosis. Although lymphangitic sporotrichosis generally is recognized as having a linear distribution, mounting evidence from this report and others suggests an annular presentation also is possible. Pruritus or pain is rare but should not preclude a diagnosis of sporotrichosis if present. For patients with limited access to health care resources, it is especially important to involve multiple members of the health care team, including social workers and specialists, to prevent a protracted and severe course of disease.

To the Editor:

Sporotrichosis refers to a subacute to chronic fungal infection that usually involves the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues and is caused by the introduction of Sporothrix, a dimorphic fungus, through the skin. We present a case of chronic atypical lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.

A 46-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic for follow-up for a rash on the right leg that spread to the thigh and became painful and pruritic. It initially developed 8 years prior to the current presentation after he sustained trauma to the leg from an electroshock weapon. One year prior to the current presentation, he had presented to the emergency department and was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days as well as bacitracin ointment. He also was instructed to follow up with dermatology, but a lack of health insurance and other socioeconomic barriers prevented him from seeking dermatologic care. Nine months later, he again presented to the emergency department due to a motor vehicle accident. Computed tomography (CT) of the right leg revealed exophytic dermal masses, inflammatory stranding of the subcutaneous tissue, and right inguinal lymph nodes measuring up to 1.4 cm; there was no osteoarticular involvement. At that time, the patient was applying gentian violet to the skin lesions and taking hydroxyzine 50 mg 3 times daily as needed for pruritus with minimal relief. Financial support was provided for follow-up with dermatology, which occurred almost 5 months later.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed a large annular plaque with verrucous, scaly, erythematous borders and a hypopigmented atrophic center extending from the medial aspect of the right leg to the posterior thigh. Numerous pink, scaly, crusted nodules were scattered primarily along the periphery, with some evidence of draining sinus tracts. In addition, a fibrotic pink linear plaque extended from the medial right leg to the popliteal fossa, consistent with a keloid. Violet staining along the periphery of the lesion also was appreciated secondary to the application of topical gentian violet (Figure 1).

Based on the chronic history and morphology, a diagnosis of a chronic fungal or atypical mycobacterial infection was favored. In particular, chromoblastomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis (eg, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis), and atypical mycobacterial infection were highest on the differential, as these conditions often exhibit annular, nodular, verrucous, and/or atrophic lesions. The nodularity, crusting, and draining sinus tracts also raised the possibility of mycetoma. Given the extension of the lesion from the lower to upper leg, a sporotrichoid infection also was considered but was thought to be less likely based on the annular configuration.

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were taken from a peripheral nodule—one for routine histology and another for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. An interferon-gamma release assay also was ordered to evaluate for immune responses indicative of prior Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, but the patient did not obtain this for unknown reasons. Histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and necrotizing granulomas, which suggested an infectious etiology, but no organisms were identified on tissue staining and all cultures were negative for growth at 6 weeks. The patient was asked to return at that point, and 4 additional scouting biopsies were performed and sent for routine histology, M tuberculosis nucleic acid amplification testing, and microbiologic cultures (ie, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, nocardia, actinomycetes). Within 1 week, a filamentous organism with pigmentation visible on the front and back of a Sabouraud dextrose agar plate was identified on fungal culture (Figure 2). Microscopic evaluation of this mold with lactophenol blue stain revealed thin septate hyphae with conidiophores arising at right angles that bore clusters of microconidia (Figure 3). Sequencing analysis ultimately identified this organism as Sporothrix schenckii. Routine histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with scattered intraepidermal collections of neutrophils (Figure 4). The dermis showed a dense, superficial, and deep infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells with occasional neutrophils and eosinophils. A Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain revealed a cluster of ovoid yeast forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 5). The patient was referred to infectious disease for follow-up and treatment.

The patient later visited a community clinic providing dermatologic care for patients without insurance. He was started on itraconazole 200 mg daily for a total of 6 months until dermatologic clearance of the cutaneous lesions was observed. He was followed by the clinic with laboratory tests including a liver function test. At follow-up 8 months later, a repeat biopsy was performed to ensure histologic clearance of the sporotrichosis, which revealed a dermal scar and no evidence of residual infection.

Sporothrix schenckii was first isolated in 1898 by Benjamin Schenck, a student at Johns Hopkins Medicine (Baltimore, Maryland), and identified by a mycologist as sporotricha.1 Species within the genus Sporothrix are unique in that the fungi are both dimorphic (growing as a mold at 25 °C but as a yeast at 37 °C) and dematiaceous (dark pigmentation from melanin is visible on inspection of the anterior and reverse sides of culture plates). Infection usually occurs when cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues are exposed to the fungus via microabrasions; activities thought to contribute to exposure include gardening, agricultural work, animal husbandry, and feline scratches.2 Although skin trauma frequently is considered the primary route of infection, patient recall is variable, with one study noting that only 37.7% of patients recalled trauma and another study similarly demonstrating a patient recall rate of 25%.3,4

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is the most common presentation of the fungal infection,5 and clinical cases may be classified into 1 of 4 categories: (1) lymphangitic lesions—papules at the site of inoculation with spread along the lymphatic channels; (2) localized (fixed) cutaneous lesions—1 or 2 lesions at the inoculation site; (3) disseminated (multifocal) cutaneous lesions; and (4) extracutaneous lesions.6 Extracutaneous manifestations of this infection most notably have been reported as pulmonary disease through inhalation of conidia or through dissemination in immunocompromised hosts.7 Our patient’s infection was categorized as lymphangitic lesions due to spread from the lower to upper leg, albeit in a highly atypical, annular fashion. A review of systems was otherwise negative, and CT ruled out osteoarticular involvement.

In addition to socioeconomic barriers, several factors contributed to a delayed diagnosis in this patient including the annular presentation with central hypopigmentation and atrophy, negative initial microbiological cultures and lack of visualization of organisms on histopathology, and the consequent need for repeat biopsies. For lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the typical presentation consists of a papule or ulcerated nodule at the site of inoculation with subsequent linear spread along lymphatic channels. This classic sporotrichoid pattern is a key diagnostic clue for identifying sporotrichosis but was absent at the time our patient presented for medical care. Rather, the sporotrichoid spread seemed to have occurred in a centrifugal fashion up the leg. Few case reports have documented an annular presentation of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis,8-13 and one report described central atrophy and hypopigmentation.10 Pain and pruritus, which were present in our patient, rarely are documented.9 Finally, the diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infections may require multiple biopsies due to the variable abundance of viable organisms in tissue specimens as well as the fastidious growth characteristics of these organisms. Furthermore, sensitivity often is low for both fungal and mycobacterial cultures, and cultures may take days to weeks to yield growth.14,15 For these reasons, empiric therapy and repeat biopsies often are pursued if clinical suspicion is high enough.16 Our patient returned for multiple scouting biopsies after the initial tissue culture was negative and was even considered for empiric treatment against Mycobacterium prior to positive fungal cultures.