User login

Flu records most active December since 2003

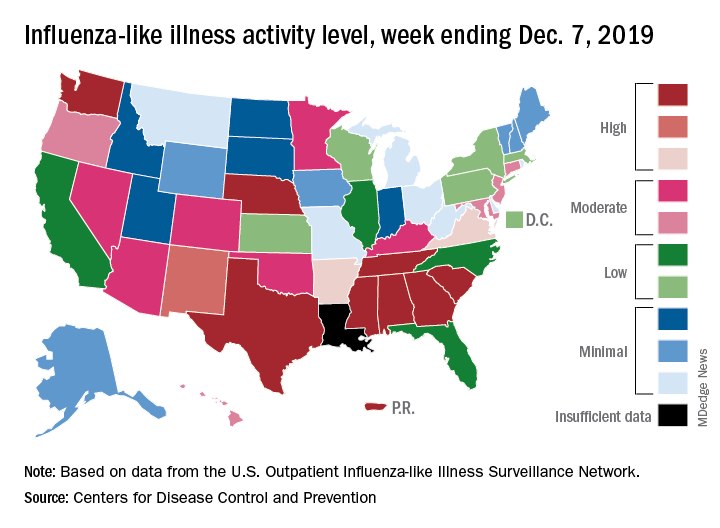

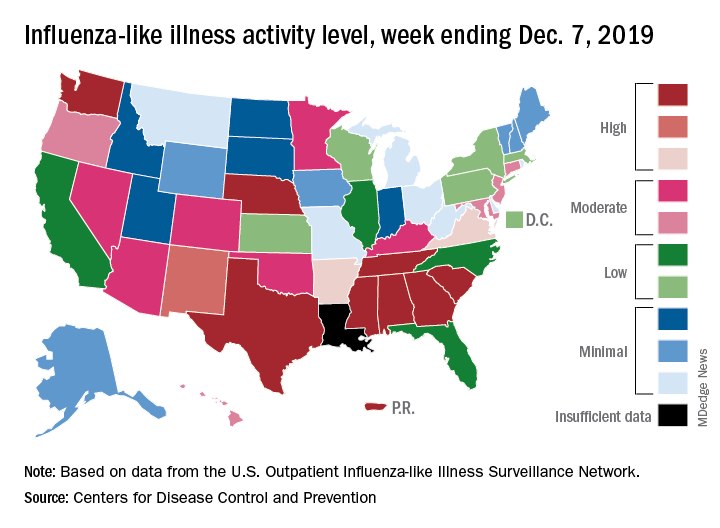

The 2019-2020 flu season took a big jump in severity during the last full week of 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

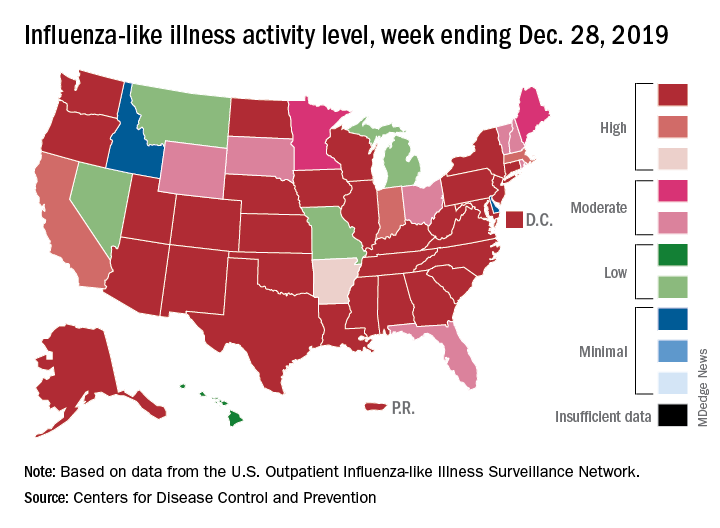

For the week ending Dec. 28, 6.9% of all outpatient visits to health care providers were for influenza-like illness (ILI), the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 3. That is up from 5.1% the previous week and is the highest rate recorded in December since 2003. During the flu pandemic season of 2009-2010, the rate peaked in October and dropped to relatively normal levels by the end of November, CDC data show.

This marks the eighth consecutive week that the outpatient visit rate has been at or above the nation’s baseline level of 2.4%, but the data for this week “may in part be influenced by changes in healthcare-seeking behavior that can occur during the holidays,” the CDC suggested.

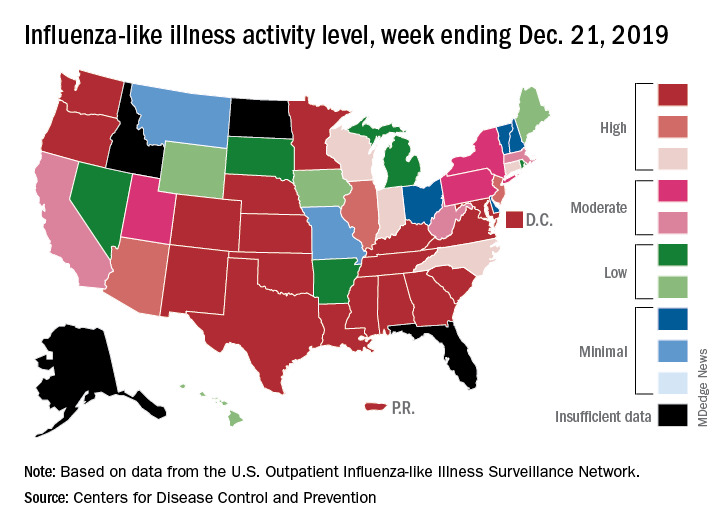

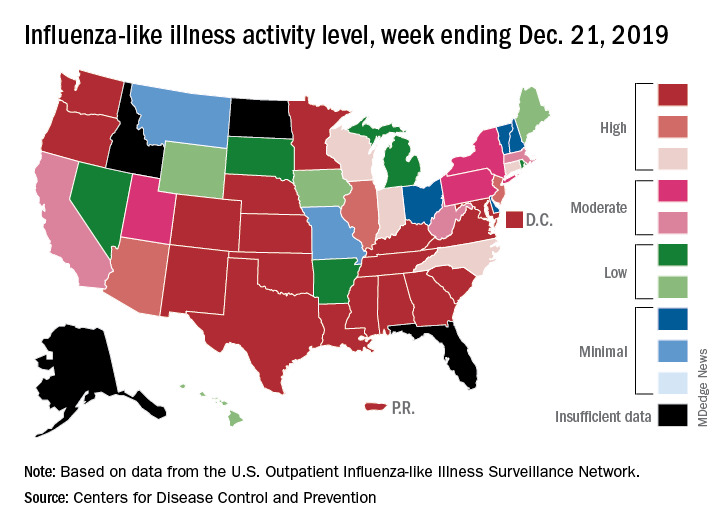

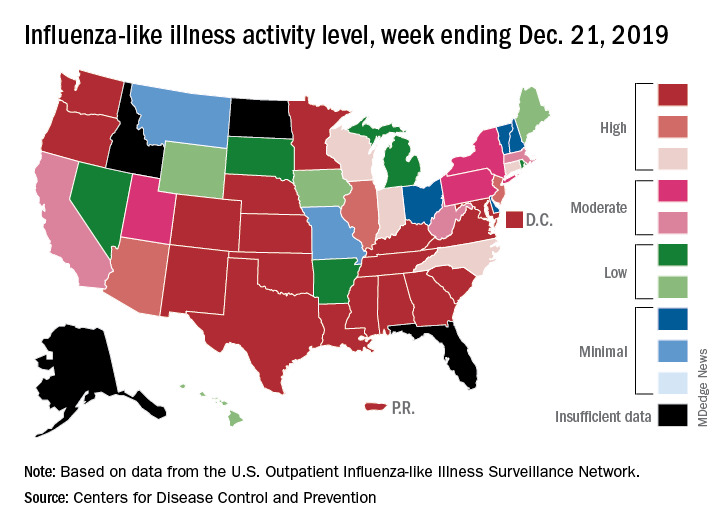

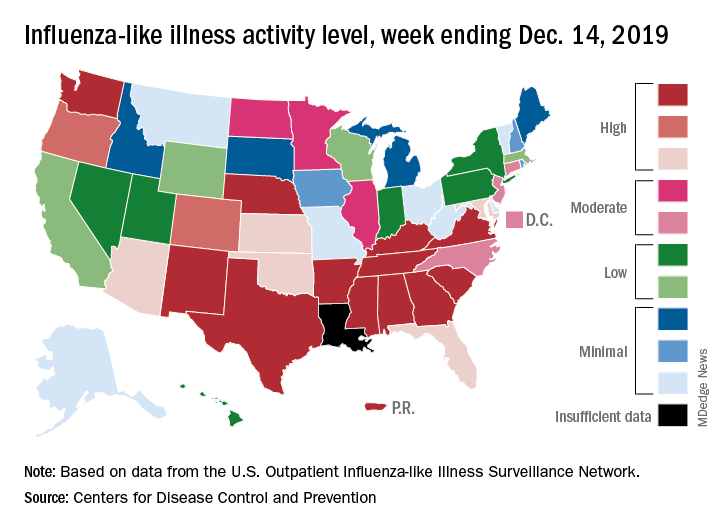

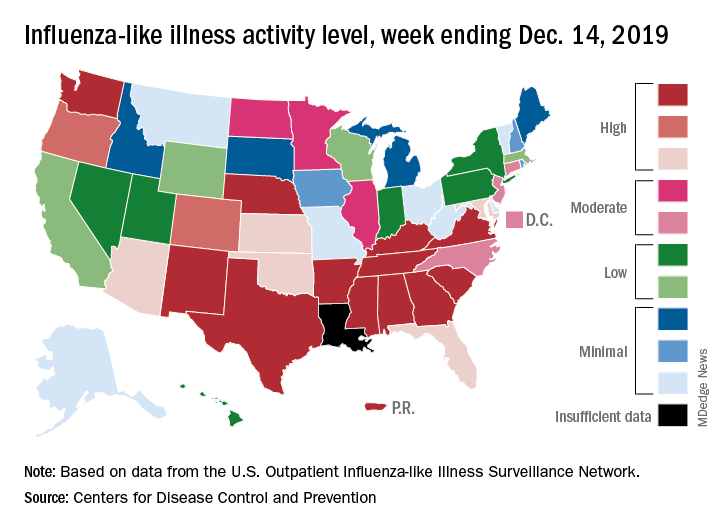

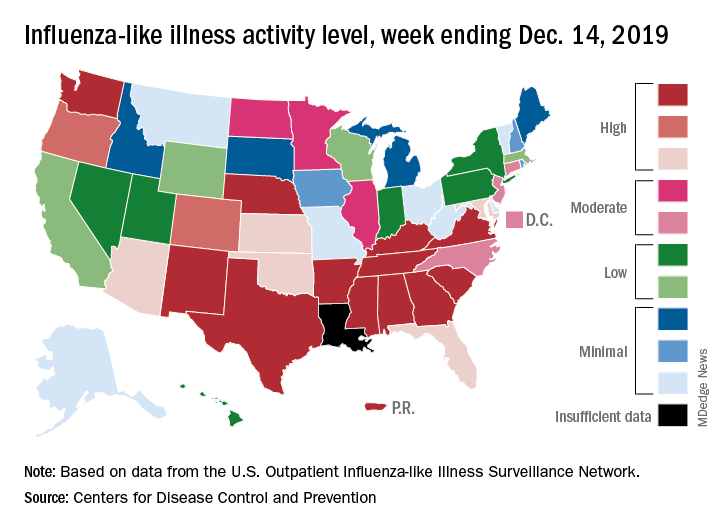

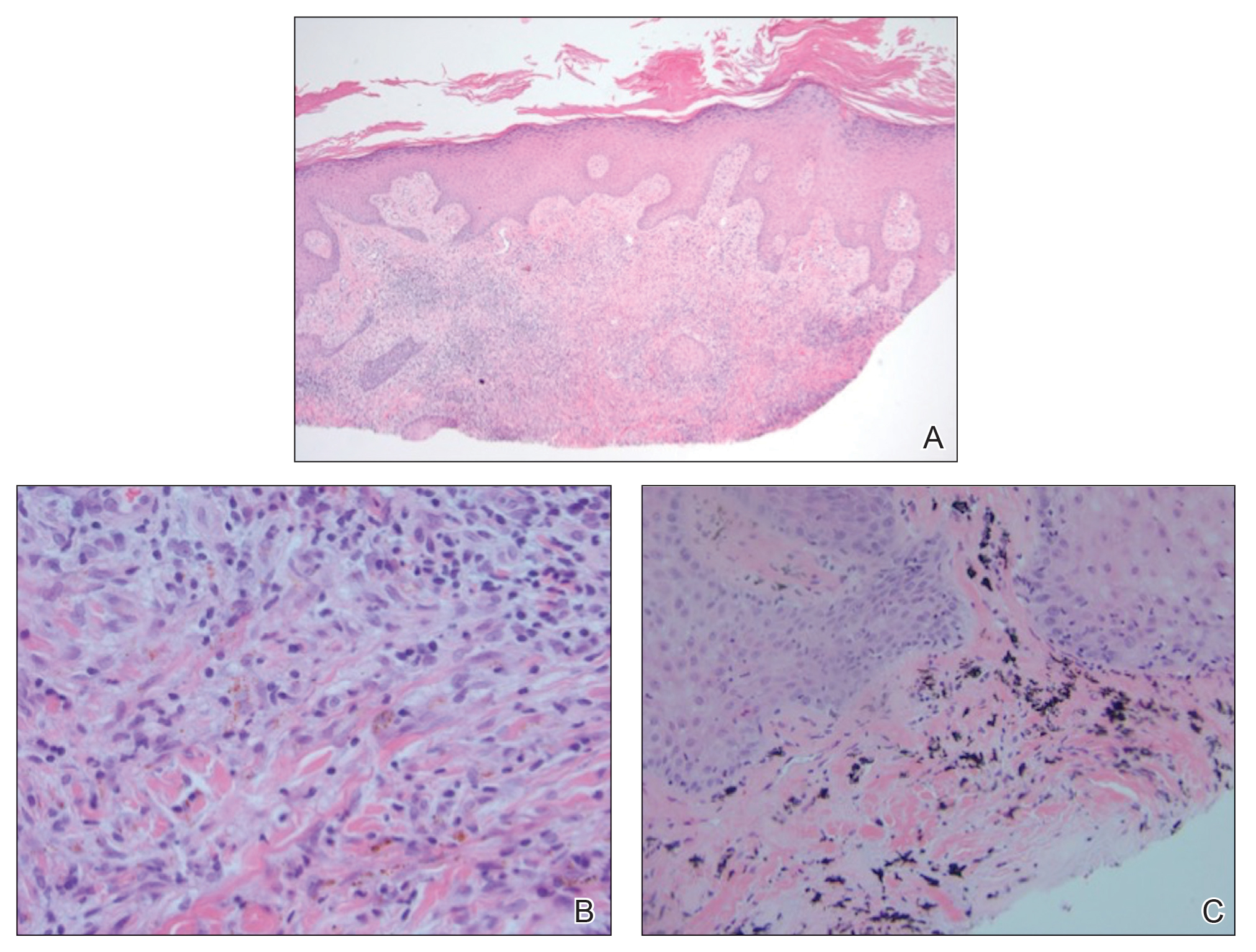

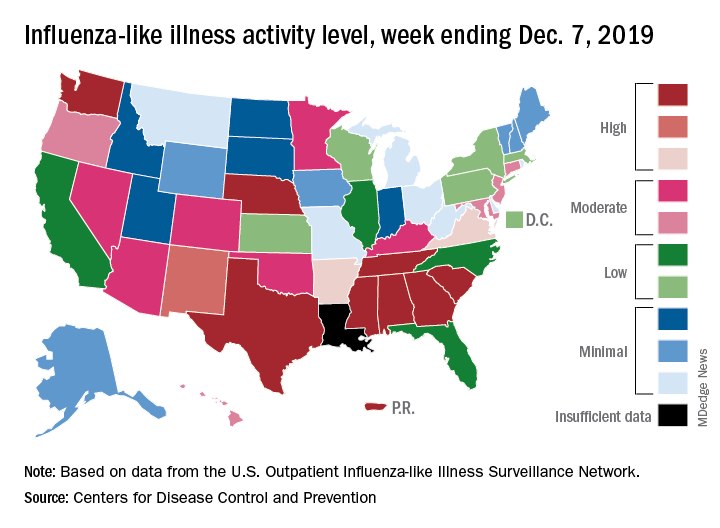

All those outpatient visits mean that the ILI activity map is getting quite red. Thirty states, as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were at the highest level on the CDC’s 1-10 activity scale during the week ending Dec. 28, compared with 20 the week before. Four states were categorized in the “high” range with activity levels of 8 and 9.

There have been approximately 6.4 million flu illnesses so far this season, the CDC estimated, along with 55,000 hospitalizations, although the ILI admission rate of 9.2 per 100,000 population is fairly typical for this time of year.

The week of Dec. 28 also brought reports of five more ILI-related pediatric deaths, which all occurred in the two previous weeks. A total of 27 children have died from the flu so far during the 2019-2020 season, the CDC said.

The 2019-2020 flu season took a big jump in severity during the last full week of 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Dec. 28, 6.9% of all outpatient visits to health care providers were for influenza-like illness (ILI), the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 3. That is up from 5.1% the previous week and is the highest rate recorded in December since 2003. During the flu pandemic season of 2009-2010, the rate peaked in October and dropped to relatively normal levels by the end of November, CDC data show.

This marks the eighth consecutive week that the outpatient visit rate has been at or above the nation’s baseline level of 2.4%, but the data for this week “may in part be influenced by changes in healthcare-seeking behavior that can occur during the holidays,” the CDC suggested.

All those outpatient visits mean that the ILI activity map is getting quite red. Thirty states, as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were at the highest level on the CDC’s 1-10 activity scale during the week ending Dec. 28, compared with 20 the week before. Four states were categorized in the “high” range with activity levels of 8 and 9.

There have been approximately 6.4 million flu illnesses so far this season, the CDC estimated, along with 55,000 hospitalizations, although the ILI admission rate of 9.2 per 100,000 population is fairly typical for this time of year.

The week of Dec. 28 also brought reports of five more ILI-related pediatric deaths, which all occurred in the two previous weeks. A total of 27 children have died from the flu so far during the 2019-2020 season, the CDC said.

The 2019-2020 flu season took a big jump in severity during the last full week of 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Dec. 28, 6.9% of all outpatient visits to health care providers were for influenza-like illness (ILI), the CDC’s influenza division reported Jan. 3. That is up from 5.1% the previous week and is the highest rate recorded in December since 2003. During the flu pandemic season of 2009-2010, the rate peaked in October and dropped to relatively normal levels by the end of November, CDC data show.

This marks the eighth consecutive week that the outpatient visit rate has been at or above the nation’s baseline level of 2.4%, but the data for this week “may in part be influenced by changes in healthcare-seeking behavior that can occur during the holidays,” the CDC suggested.

All those outpatient visits mean that the ILI activity map is getting quite red. Thirty states, as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were at the highest level on the CDC’s 1-10 activity scale during the week ending Dec. 28, compared with 20 the week before. Four states were categorized in the “high” range with activity levels of 8 and 9.

There have been approximately 6.4 million flu illnesses so far this season, the CDC estimated, along with 55,000 hospitalizations, although the ILI admission rate of 9.2 per 100,000 population is fairly typical for this time of year.

The week of Dec. 28 also brought reports of five more ILI-related pediatric deaths, which all occurred in the two previous weeks. A total of 27 children have died from the flu so far during the 2019-2020 season, the CDC said.

Despite PCV, pediatric asthma patients face pneumococcal risks

Even on-time pneumococcal vaccines don’t completely protect children with asthma from developing invasive pneumococcal disease, a meta-analysis has determined.

Despite receiving pneumococcal valent 7, 10, or 13, children with asthma were still almost twice as likely to develop the disease as were children without asthma, Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, PhD, and colleagues reported in Pediatrics (2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200). None of the studies included rates for those who received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

“For the first time, this meta-analysis reveals 90% increased odds of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among [vaccinated] children with asthma,” said Dr. Castro-Rodriguez, of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, and colleagues. “If confirmed, these findings will bear clinical and public health importance,” they noted, because guidelines now recommend PPSV23 after age 2 in children with asthma only if they’re treated with prolonged high-dose oral corticosteroids.

However, because the analysis comprised only four studies, the authors cautioned that the results aren’t enough to justify changes to practice recommendations.

Asthma treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) may be driving the increased risk, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his coauthors suggested. ICS deposition in the oropharynx could boost oropharyngeal candidiasis risk by weakening the mucosal immune response, the researchers noted. And that same process may be at work with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A prior study found that children with asthma who received ICS for at least 1 month were almost four times more likely to have oropharyngeal colonization by S. pneumoniae as were those who didn’t get the drugs. Thus, a higher carrier rate of S. pneumoniae in the oropharynx, along with asthma’s impaired airway clearance, might increase the risk of pneumococcal diseases, the investigators explained.

Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and colleagues analyzed four studies with more than 4,000 cases and controls, and about 26 million person-years of follow-up.

Rates and risks of IPD in the four studies were as follows:

- Among those with IPD, 27% had asthma, with 18% of those without, an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.8.

- In a European of patients who received at least 3 doses of PCV7, IPD rates per 100,000 person-years for 5-year-olds were 11.6 for children with asthma and 7.3 for those without. For 5- to 17-year-olds with and without asthma, the rates were 2.3 and 1.6, respectively.

- In 2001, a Korean found an aOR of 2.08 for IPD in children with asthma, compared with those without. In 2010, the aOR was 3.26. No vaccine types were reported in the study.

- of IPD were 3.7 per 100,000 person-years for children with asthma, compared with 2.5 for healthy controls – an adjusted relative risk of 1.5.

The pooled estimate of the four studies revealed an aOR of 1.9 for IPD among children with asthma, compared with those without, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his team concluded.

None of the studies reported hospital admissions, mortality, length of hospital stay, intensive care admission, invasive respiratory support, or additional medication use.

One, however, did find asthma severity was significantly associated with increasing IPD treatment costs per 100,000 person-years: $72,581 for healthy controls, compared with $100,020 for children with mild asthma, $172,002 for moderate asthma, and $638,452 for severe asthma.

In addition, treating all-cause pneumonia was more expensive in children with asthma. For all-cause pneumonia, the researchers found that estimated costs per 100,000 person-years for mild, moderate, and severe asthma were $7.5 million, $14.6 million, and $46.8 million, respectively, compared with $1.7 million for healthy controls.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Castro-Rodriguez J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200.

The meta-analysis contains some important lessons for pediatricians, Tina Q. Tan, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“First, asthma remains a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal pneumonia, even in the era of widespread use of PCV,” Dr. Tan noted. “Second, it is important that all patients, especially those with asthma, are receiving their vaccinations on time and, most notably, are up to date on their pneumococcal vaccinations. This will provide the best protection against pneumococcal infections and their complications for pediatric patients with asthma.”

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) have impressively decreased rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and pneumonia in children in the United States, Dr. Tan explained. Overall, incidence dropped from 95 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1998 to only 9 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

In addition, the incidence of IPD caused by 13-valent PCV serotypes fell, from 88 cases per 100,000 in 1998 to 2 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

The threat is not over, however.

“IPD still remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide,” Dr. Tan cautioned. “In 2017, the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance network reported that there were 31,000 cases of IPD (meningitis, bacteremia, and bacteremic pneumonia) and 3,590 deaths, of which 147 cases and 9 deaths occurred in children younger than 5 years of age.”

Dr. Tan is a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. Her comments appear in Pediatrics 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3360 .

The meta-analysis contains some important lessons for pediatricians, Tina Q. Tan, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“First, asthma remains a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal pneumonia, even in the era of widespread use of PCV,” Dr. Tan noted. “Second, it is important that all patients, especially those with asthma, are receiving their vaccinations on time and, most notably, are up to date on their pneumococcal vaccinations. This will provide the best protection against pneumococcal infections and their complications for pediatric patients with asthma.”

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) have impressively decreased rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and pneumonia in children in the United States, Dr. Tan explained. Overall, incidence dropped from 95 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1998 to only 9 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

In addition, the incidence of IPD caused by 13-valent PCV serotypes fell, from 88 cases per 100,000 in 1998 to 2 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

The threat is not over, however.

“IPD still remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide,” Dr. Tan cautioned. “In 2017, the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance network reported that there were 31,000 cases of IPD (meningitis, bacteremia, and bacteremic pneumonia) and 3,590 deaths, of which 147 cases and 9 deaths occurred in children younger than 5 years of age.”

Dr. Tan is a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. Her comments appear in Pediatrics 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3360 .

The meta-analysis contains some important lessons for pediatricians, Tina Q. Tan, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“First, asthma remains a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal pneumonia, even in the era of widespread use of PCV,” Dr. Tan noted. “Second, it is important that all patients, especially those with asthma, are receiving their vaccinations on time and, most notably, are up to date on their pneumococcal vaccinations. This will provide the best protection against pneumococcal infections and their complications for pediatric patients with asthma.”

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) have impressively decreased rates of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and pneumonia in children in the United States, Dr. Tan explained. Overall, incidence dropped from 95 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1998 to only 9 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

In addition, the incidence of IPD caused by 13-valent PCV serotypes fell, from 88 cases per 100,000 in 1998 to 2 cases per 100,000 in 2016.

The threat is not over, however.

“IPD still remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide,” Dr. Tan cautioned. “In 2017, the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance network reported that there were 31,000 cases of IPD (meningitis, bacteremia, and bacteremic pneumonia) and 3,590 deaths, of which 147 cases and 9 deaths occurred in children younger than 5 years of age.”

Dr. Tan is a professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. Her comments appear in Pediatrics 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3360 .

Even on-time pneumococcal vaccines don’t completely protect children with asthma from developing invasive pneumococcal disease, a meta-analysis has determined.

Despite receiving pneumococcal valent 7, 10, or 13, children with asthma were still almost twice as likely to develop the disease as were children without asthma, Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, PhD, and colleagues reported in Pediatrics (2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200). None of the studies included rates for those who received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

“For the first time, this meta-analysis reveals 90% increased odds of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among [vaccinated] children with asthma,” said Dr. Castro-Rodriguez, of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, and colleagues. “If confirmed, these findings will bear clinical and public health importance,” they noted, because guidelines now recommend PPSV23 after age 2 in children with asthma only if they’re treated with prolonged high-dose oral corticosteroids.

However, because the analysis comprised only four studies, the authors cautioned that the results aren’t enough to justify changes to practice recommendations.

Asthma treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) may be driving the increased risk, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his coauthors suggested. ICS deposition in the oropharynx could boost oropharyngeal candidiasis risk by weakening the mucosal immune response, the researchers noted. And that same process may be at work with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A prior study found that children with asthma who received ICS for at least 1 month were almost four times more likely to have oropharyngeal colonization by S. pneumoniae as were those who didn’t get the drugs. Thus, a higher carrier rate of S. pneumoniae in the oropharynx, along with asthma’s impaired airway clearance, might increase the risk of pneumococcal diseases, the investigators explained.

Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and colleagues analyzed four studies with more than 4,000 cases and controls, and about 26 million person-years of follow-up.

Rates and risks of IPD in the four studies were as follows:

- Among those with IPD, 27% had asthma, with 18% of those without, an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.8.

- In a European of patients who received at least 3 doses of PCV7, IPD rates per 100,000 person-years for 5-year-olds were 11.6 for children with asthma and 7.3 for those without. For 5- to 17-year-olds with and without asthma, the rates were 2.3 and 1.6, respectively.

- In 2001, a Korean found an aOR of 2.08 for IPD in children with asthma, compared with those without. In 2010, the aOR was 3.26. No vaccine types were reported in the study.

- of IPD were 3.7 per 100,000 person-years for children with asthma, compared with 2.5 for healthy controls – an adjusted relative risk of 1.5.

The pooled estimate of the four studies revealed an aOR of 1.9 for IPD among children with asthma, compared with those without, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his team concluded.

None of the studies reported hospital admissions, mortality, length of hospital stay, intensive care admission, invasive respiratory support, or additional medication use.

One, however, did find asthma severity was significantly associated with increasing IPD treatment costs per 100,000 person-years: $72,581 for healthy controls, compared with $100,020 for children with mild asthma, $172,002 for moderate asthma, and $638,452 for severe asthma.

In addition, treating all-cause pneumonia was more expensive in children with asthma. For all-cause pneumonia, the researchers found that estimated costs per 100,000 person-years for mild, moderate, and severe asthma were $7.5 million, $14.6 million, and $46.8 million, respectively, compared with $1.7 million for healthy controls.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Castro-Rodriguez J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200.

Even on-time pneumococcal vaccines don’t completely protect children with asthma from developing invasive pneumococcal disease, a meta-analysis has determined.

Despite receiving pneumococcal valent 7, 10, or 13, children with asthma were still almost twice as likely to develop the disease as were children without asthma, Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, PhD, and colleagues reported in Pediatrics (2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200). None of the studies included rates for those who received the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

“For the first time, this meta-analysis reveals 90% increased odds of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among [vaccinated] children with asthma,” said Dr. Castro-Rodriguez, of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, and colleagues. “If confirmed, these findings will bear clinical and public health importance,” they noted, because guidelines now recommend PPSV23 after age 2 in children with asthma only if they’re treated with prolonged high-dose oral corticosteroids.

However, because the analysis comprised only four studies, the authors cautioned that the results aren’t enough to justify changes to practice recommendations.

Asthma treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) may be driving the increased risk, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his coauthors suggested. ICS deposition in the oropharynx could boost oropharyngeal candidiasis risk by weakening the mucosal immune response, the researchers noted. And that same process may be at work with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

A prior study found that children with asthma who received ICS for at least 1 month were almost four times more likely to have oropharyngeal colonization by S. pneumoniae as were those who didn’t get the drugs. Thus, a higher carrier rate of S. pneumoniae in the oropharynx, along with asthma’s impaired airway clearance, might increase the risk of pneumococcal diseases, the investigators explained.

Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and colleagues analyzed four studies with more than 4,000 cases and controls, and about 26 million person-years of follow-up.

Rates and risks of IPD in the four studies were as follows:

- Among those with IPD, 27% had asthma, with 18% of those without, an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.8.

- In a European of patients who received at least 3 doses of PCV7, IPD rates per 100,000 person-years for 5-year-olds were 11.6 for children with asthma and 7.3 for those without. For 5- to 17-year-olds with and without asthma, the rates were 2.3 and 1.6, respectively.

- In 2001, a Korean found an aOR of 2.08 for IPD in children with asthma, compared with those without. In 2010, the aOR was 3.26. No vaccine types were reported in the study.

- of IPD were 3.7 per 100,000 person-years for children with asthma, compared with 2.5 for healthy controls – an adjusted relative risk of 1.5.

The pooled estimate of the four studies revealed an aOR of 1.9 for IPD among children with asthma, compared with those without, Dr. Castro-Rodriguez and his team concluded.

None of the studies reported hospital admissions, mortality, length of hospital stay, intensive care admission, invasive respiratory support, or additional medication use.

One, however, did find asthma severity was significantly associated with increasing IPD treatment costs per 100,000 person-years: $72,581 for healthy controls, compared with $100,020 for children with mild asthma, $172,002 for moderate asthma, and $638,452 for severe asthma.

In addition, treating all-cause pneumonia was more expensive in children with asthma. For all-cause pneumonia, the researchers found that estimated costs per 100,000 person-years for mild, moderate, and severe asthma were $7.5 million, $14.6 million, and $46.8 million, respectively, compared with $1.7 million for healthy controls.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Castro-Rodriguez J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1200.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Early increase in flu activity shows no signs of slowing

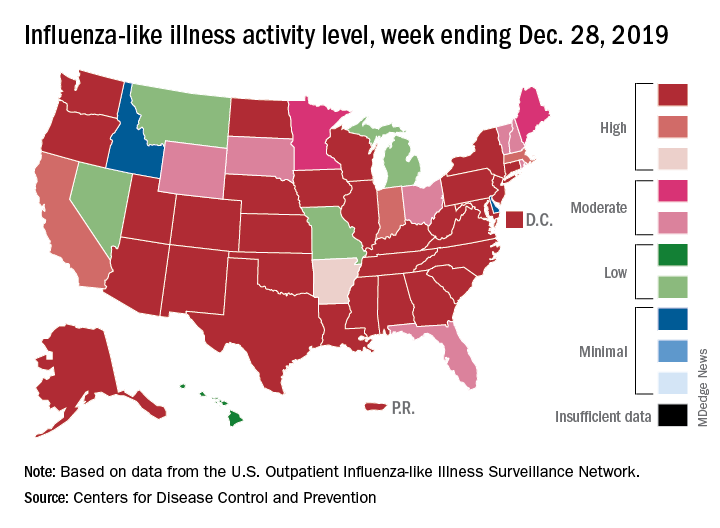

An important measure of U.S. flu activity for the 2019-2020 season has already surpassed last season’s high, and more than half the states are experiencing high levels of activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

reported Dec. 27.

The last time the outpatient visit rate was higher than that was in February of the 2017-2018 season, when it peaked at 7.5%. The peak month of flu activity occurs most often – about once every 3 years – in February, and the odds of a December peak are about one in five, the CDC has said.

Outpatient illness activity also increased at the state level during the week ending Dec. 21. There were 20 jurisdictions – 18 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity, compared with 13 the previous week, and the number of jurisdictions in the “high” range (levels 8-10) jumped from 21 to 28, the CDC data show.

The influenza division estimated that there have been 4.6 million flu illnesses so far this season, nearly a million more than the total after last week, along with 39,000 hospitalizations. The overall hospitalization rate for the season is up to 6.6 per 100,000 population, which is about average at this point. The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza increased to 5.7%, which is below the epidemic threshold, the CDC said.

Three pediatric deaths related to influenza-like illness were reported during the week ending Dec. 21, two of which occurred in an earlier week. For the 2019-2020 season so far, a total of 22 pediatric deaths have been reported to the CDC.

An important measure of U.S. flu activity for the 2019-2020 season has already surpassed last season’s high, and more than half the states are experiencing high levels of activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

reported Dec. 27.

The last time the outpatient visit rate was higher than that was in February of the 2017-2018 season, when it peaked at 7.5%. The peak month of flu activity occurs most often – about once every 3 years – in February, and the odds of a December peak are about one in five, the CDC has said.

Outpatient illness activity also increased at the state level during the week ending Dec. 21. There were 20 jurisdictions – 18 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity, compared with 13 the previous week, and the number of jurisdictions in the “high” range (levels 8-10) jumped from 21 to 28, the CDC data show.

The influenza division estimated that there have been 4.6 million flu illnesses so far this season, nearly a million more than the total after last week, along with 39,000 hospitalizations. The overall hospitalization rate for the season is up to 6.6 per 100,000 population, which is about average at this point. The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza increased to 5.7%, which is below the epidemic threshold, the CDC said.

Three pediatric deaths related to influenza-like illness were reported during the week ending Dec. 21, two of which occurred in an earlier week. For the 2019-2020 season so far, a total of 22 pediatric deaths have been reported to the CDC.

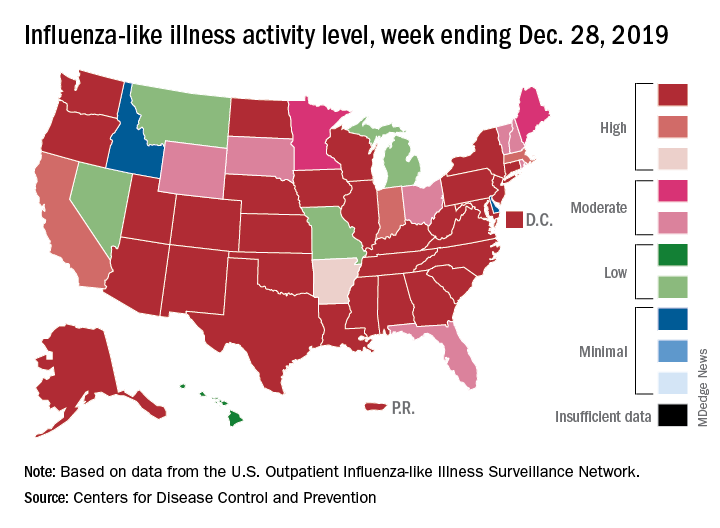

An important measure of U.S. flu activity for the 2019-2020 season has already surpassed last season’s high, and more than half the states are experiencing high levels of activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

reported Dec. 27.

The last time the outpatient visit rate was higher than that was in February of the 2017-2018 season, when it peaked at 7.5%. The peak month of flu activity occurs most often – about once every 3 years – in February, and the odds of a December peak are about one in five, the CDC has said.

Outpatient illness activity also increased at the state level during the week ending Dec. 21. There were 20 jurisdictions – 18 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity, compared with 13 the previous week, and the number of jurisdictions in the “high” range (levels 8-10) jumped from 21 to 28, the CDC data show.

The influenza division estimated that there have been 4.6 million flu illnesses so far this season, nearly a million more than the total after last week, along with 39,000 hospitalizations. The overall hospitalization rate for the season is up to 6.6 per 100,000 population, which is about average at this point. The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza increased to 5.7%, which is below the epidemic threshold, the CDC said.

Three pediatric deaths related to influenza-like illness were reported during the week ending Dec. 21, two of which occurred in an earlier week. For the 2019-2020 season so far, a total of 22 pediatric deaths have been reported to the CDC.

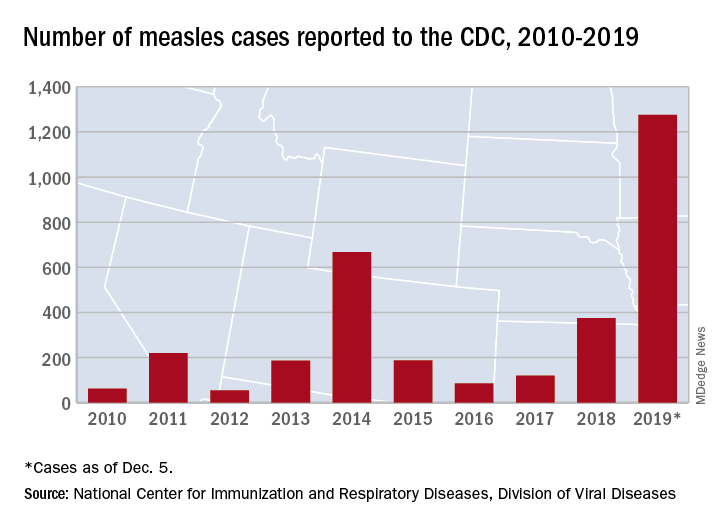

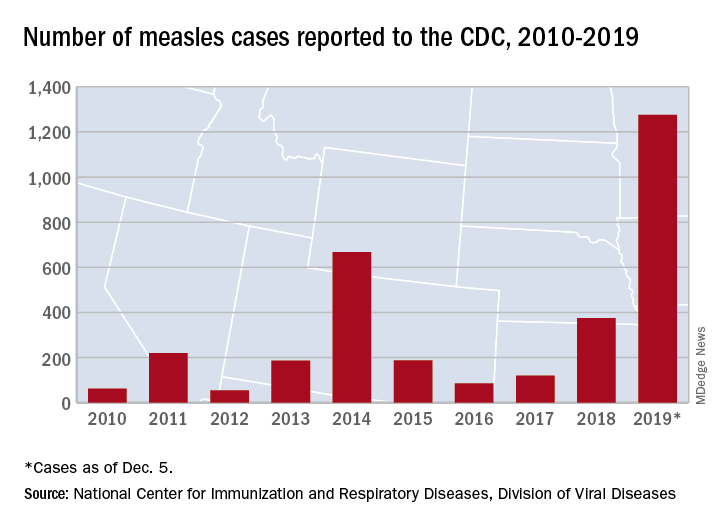

The measles comeback of 2019

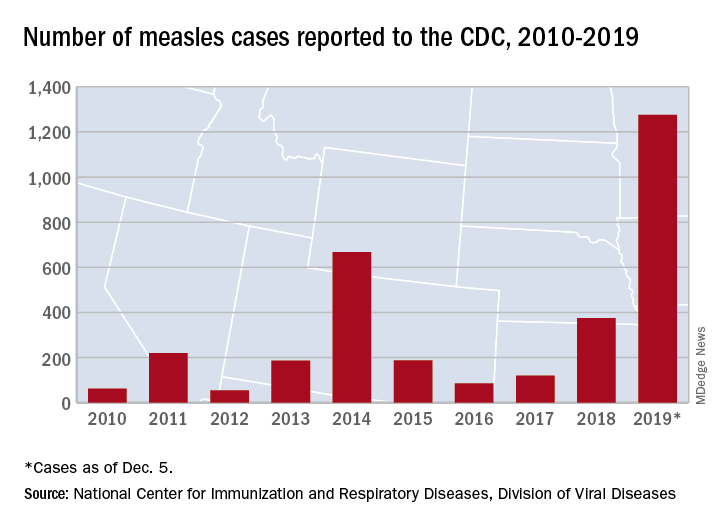

Measles made a comeback in 2019.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, as of Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles of measles were confirmed in 31 states, the largest number since 1992. This number is a major uptick in cases, compared with previous years since 2000 when the CDC declared measles eliminated from the United States. No deaths have been reported for 2019.

Three-quarters of these cases in 2019 were linked to recent outbreaks in New York and occurred in primarily in underimmunized, close-knit communities and in patients with links to international travel. A total of 124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 61 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis. The overall median patient age was 6 years (31% aged 1-4 years, 27% aged 5-17 years, and 29% aged at least 18 years).

The good news is that most of these cases occurred in unvaccinated patients. The national vaccination rate for the almost 4 million kindergartners reported as enrolled in 2018-2019 was 94.7% for two doses of the MMR vaccine, falling just short of the CDC recommended 95% vaccination rate threshold. The CDC reported an approximate 2.5% rate of vaccination exemptions among school-age children.

The bad news is that, despite the high rate of MMR vaccination rates among U.S. children, there are gaps in measles protection in the U.S. population because of factors leaving patients immunocompromised and antivaccination sentiment that has led some parents to defer or refuse the MMR.

In addition, adults who were vaccinated prior to 1968 with either inactivated measles vaccine or measles vaccine of unknown type may have limited immunity. The inactivated measles vaccine, which was available in 1963-1967, did not achieve effective measles protection.

A global measles surge

While antivaccination sentiment contributed to the 2019 measles cases, a more significant factor may be the global surge of measles. More than 140,000 people worldwide died from measles in 2018, according to the World Health Organization and the CDC.

“[Recent data on measles] indicates that during the first 6 months of the year there have been more measles cases reported worldwide than in any year since 2006. From Jan. 1 to July 31, 2019, 182 countries reported 364,808 measles cases to the WHO. This surpasses the 129,239 reported during the same time period in 2018. WHO regions with the biggest increases in cases include the African region (900%), the Western Pacific region (230%), and the European region (150%),” according to a CDC report.

Studies on hospitalization and complications linked to measles in the United States are scarce, but two outbreaks in Minnesota (2011 and 2017) provided some data on what to expect if the measles surge continues into 2020. The investigators found that poor feeding was a primary reason for admission (97%); additional complications included otitis media (42%), pneumonia (30%), and tracheitis (6%). Three-quarters received antibiotics, 30% required oxygen, and 21% received vitamin A. Median length of stay was 3.7 days (range, 1.1-26.2 days) (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Jun;38[6]:547-52. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002221).

‘Immunological amnesia’

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science (2019 Nov 1;366[6465]599-606).

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

Maternal-acquired immunity fades

In another study of measles immunity, maternal antibodies were found to be insufficient to provide immunity to infants after 6 months.

The study of 196 infants showed that maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics (2019 Dec 1. doi 10.1542/peds.2019-0630).

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days), 2 months (61-89 days), 3 months (90-119 days), 4 months, 5 months, 6-9 months, and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL), and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Huong Q. McLean, PhD, of Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, noted in an editorial.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Bianca Nogrady and Tara Haelle contributed to this story.

Measles made a comeback in 2019.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, as of Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles of measles were confirmed in 31 states, the largest number since 1992. This number is a major uptick in cases, compared with previous years since 2000 when the CDC declared measles eliminated from the United States. No deaths have been reported for 2019.

Three-quarters of these cases in 2019 were linked to recent outbreaks in New York and occurred in primarily in underimmunized, close-knit communities and in patients with links to international travel. A total of 124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 61 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis. The overall median patient age was 6 years (31% aged 1-4 years, 27% aged 5-17 years, and 29% aged at least 18 years).

The good news is that most of these cases occurred in unvaccinated patients. The national vaccination rate for the almost 4 million kindergartners reported as enrolled in 2018-2019 was 94.7% for two doses of the MMR vaccine, falling just short of the CDC recommended 95% vaccination rate threshold. The CDC reported an approximate 2.5% rate of vaccination exemptions among school-age children.

The bad news is that, despite the high rate of MMR vaccination rates among U.S. children, there are gaps in measles protection in the U.S. population because of factors leaving patients immunocompromised and antivaccination sentiment that has led some parents to defer or refuse the MMR.

In addition, adults who were vaccinated prior to 1968 with either inactivated measles vaccine or measles vaccine of unknown type may have limited immunity. The inactivated measles vaccine, which was available in 1963-1967, did not achieve effective measles protection.

A global measles surge

While antivaccination sentiment contributed to the 2019 measles cases, a more significant factor may be the global surge of measles. More than 140,000 people worldwide died from measles in 2018, according to the World Health Organization and the CDC.

“[Recent data on measles] indicates that during the first 6 months of the year there have been more measles cases reported worldwide than in any year since 2006. From Jan. 1 to July 31, 2019, 182 countries reported 364,808 measles cases to the WHO. This surpasses the 129,239 reported during the same time period in 2018. WHO regions with the biggest increases in cases include the African region (900%), the Western Pacific region (230%), and the European region (150%),” according to a CDC report.

Studies on hospitalization and complications linked to measles in the United States are scarce, but two outbreaks in Minnesota (2011 and 2017) provided some data on what to expect if the measles surge continues into 2020. The investigators found that poor feeding was a primary reason for admission (97%); additional complications included otitis media (42%), pneumonia (30%), and tracheitis (6%). Three-quarters received antibiotics, 30% required oxygen, and 21% received vitamin A. Median length of stay was 3.7 days (range, 1.1-26.2 days) (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Jun;38[6]:547-52. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002221).

‘Immunological amnesia’

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science (2019 Nov 1;366[6465]599-606).

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

Maternal-acquired immunity fades

In another study of measles immunity, maternal antibodies were found to be insufficient to provide immunity to infants after 6 months.

The study of 196 infants showed that maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics (2019 Dec 1. doi 10.1542/peds.2019-0630).

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days), 2 months (61-89 days), 3 months (90-119 days), 4 months, 5 months, 6-9 months, and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL), and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Huong Q. McLean, PhD, of Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, noted in an editorial.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Bianca Nogrady and Tara Haelle contributed to this story.

Measles made a comeback in 2019.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, as of Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles of measles were confirmed in 31 states, the largest number since 1992. This number is a major uptick in cases, compared with previous years since 2000 when the CDC declared measles eliminated from the United States. No deaths have been reported for 2019.

Three-quarters of these cases in 2019 were linked to recent outbreaks in New York and occurred in primarily in underimmunized, close-knit communities and in patients with links to international travel. A total of 124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 61 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis. The overall median patient age was 6 years (31% aged 1-4 years, 27% aged 5-17 years, and 29% aged at least 18 years).

The good news is that most of these cases occurred in unvaccinated patients. The national vaccination rate for the almost 4 million kindergartners reported as enrolled in 2018-2019 was 94.7% for two doses of the MMR vaccine, falling just short of the CDC recommended 95% vaccination rate threshold. The CDC reported an approximate 2.5% rate of vaccination exemptions among school-age children.

The bad news is that, despite the high rate of MMR vaccination rates among U.S. children, there are gaps in measles protection in the U.S. population because of factors leaving patients immunocompromised and antivaccination sentiment that has led some parents to defer or refuse the MMR.

In addition, adults who were vaccinated prior to 1968 with either inactivated measles vaccine or measles vaccine of unknown type may have limited immunity. The inactivated measles vaccine, which was available in 1963-1967, did not achieve effective measles protection.

A global measles surge

While antivaccination sentiment contributed to the 2019 measles cases, a more significant factor may be the global surge of measles. More than 140,000 people worldwide died from measles in 2018, according to the World Health Organization and the CDC.

“[Recent data on measles] indicates that during the first 6 months of the year there have been more measles cases reported worldwide than in any year since 2006. From Jan. 1 to July 31, 2019, 182 countries reported 364,808 measles cases to the WHO. This surpasses the 129,239 reported during the same time period in 2018. WHO regions with the biggest increases in cases include the African region (900%), the Western Pacific region (230%), and the European region (150%),” according to a CDC report.

Studies on hospitalization and complications linked to measles in the United States are scarce, but two outbreaks in Minnesota (2011 and 2017) provided some data on what to expect if the measles surge continues into 2020. The investigators found that poor feeding was a primary reason for admission (97%); additional complications included otitis media (42%), pneumonia (30%), and tracheitis (6%). Three-quarters received antibiotics, 30% required oxygen, and 21% received vitamin A. Median length of stay was 3.7 days (range, 1.1-26.2 days) (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Jun;38[6]:547-52. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002221).

‘Immunological amnesia’

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science (2019 Nov 1;366[6465]599-606).

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

Maternal-acquired immunity fades

In another study of measles immunity, maternal antibodies were found to be insufficient to provide immunity to infants after 6 months.

The study of 196 infants showed that maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics (2019 Dec 1. doi 10.1542/peds.2019-0630).

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days), 2 months (61-89 days), 3 months (90-119 days), 4 months, 5 months, 6-9 months, and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL), and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Huong Q. McLean, PhD, of Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, noted in an editorial.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Bianca Nogrady and Tara Haelle contributed to this story.

North American Blastomycosis in an Immunocompromised Patient

Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal infection that is endemic in the South Central, Midwest, and southeastern regions of the United States, as well as in provinces of Canada bordering the Great Lakes. After inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis spores, which are taken up by bronchopulmonary macrophages, there is an approximate 30- to 45-day incubation period. The initial response at the infected site is suppurative, which progresses to granuloma formation. Blastomyces dermatitidis most commonly infects the lungs, followed by the skin, bones, prostate, and central nervous system (CNS). Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent.

We present the case of a 38-year-old man with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS who reported a 3- to 4-week history of respiratory and cutaneous symptoms. Initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis; however, after laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment for syphilis, further investigation revealed a diagnosis of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis.

Case Report

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of HIV infection and AIDS presented to the emergency department at a medical center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with a cough; chest discomfort; and concomitant nonpainful, mildly pruritic papules and plaques of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration that initially appeared on the face and ears and spread to the trunk, arms, palms, legs, and feet. He had a nonpainful ulcer on the glans penis. Symptoms began while he was living in Atlanta, Georgia, before relocating to Minneapolis. A chest radiograph was negative.

The initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis. Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million U) weekly for 3 weeks was initiated by the primary care team based on clinical suspicion alone without laboratory evidence of a positive rapid plasma reagin or VDRL test. Because laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment did not support syphilis, dermatology consultation was requested.

The patient had a history of crack cocaine abuse. He reported sexual activity with a single female partner while living in a halfway house in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. Physical examination showed an age-appropriate man in no acute distress who was alert and oriented. He had well-demarcated papules and plaques on the forehead, ears, nose, cutaneous and mucosal lips, chest, back, arms, legs, palms, and soles. Many of the facial papules were pink, nonscaly, and concentrated around the nose and mouth; some were umbilicated (Figure 1). Trunk and extensor papules and plaques were well demarcated, oval, and scaly; some had erosions centrally and were excoriated. Palmar papules were round and had peripheral brown hyperpigmentation and central scale (Figure 2). A 1-cm, shallow, nontender, oval ulceration withraised borders was located on the glans penis under the foreskin (Figure 3).

A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive; a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test was negative. Chest radiograph, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalogram were normal. In addition, spinal fluid drawn from a tap was negative on India ink and Gram stain preparations and was negative for cryptococcal antigen. In addition, spinal fluid was negative for fungal and bacterial growth, as were blood cultures.

Abnormal tests included a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot test for HIV, with an absolute CD4 count of 6 cells/mL and a viral load more than 100,000 copies/mL. Urine histoplasmosis antigen was markedly elevated. A potassium hydroxide preparation was performed on the skin of the right forearm, revealing broad-based budding yeast, later confirmed on skin and sputum cultures to be B dermatitidis.

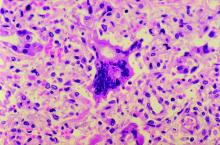

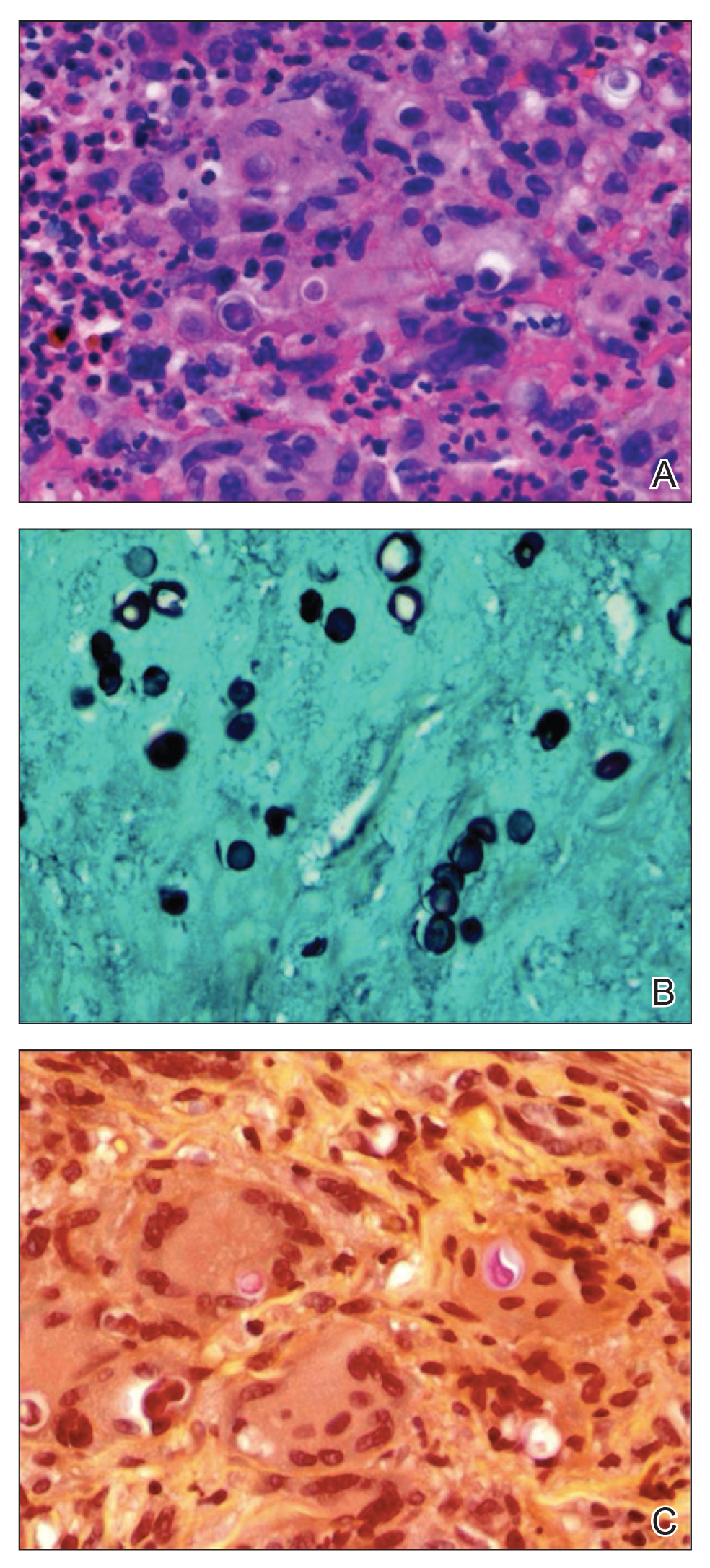

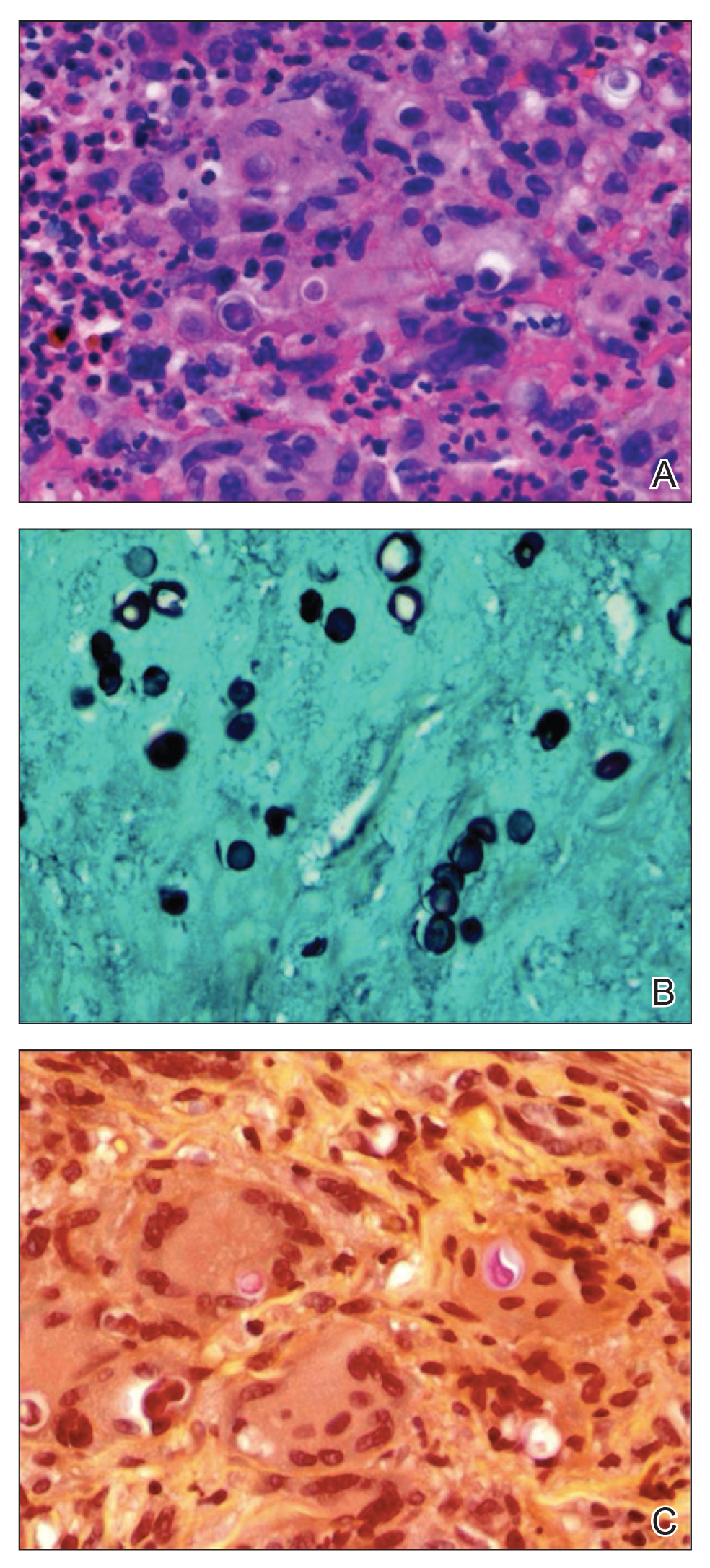

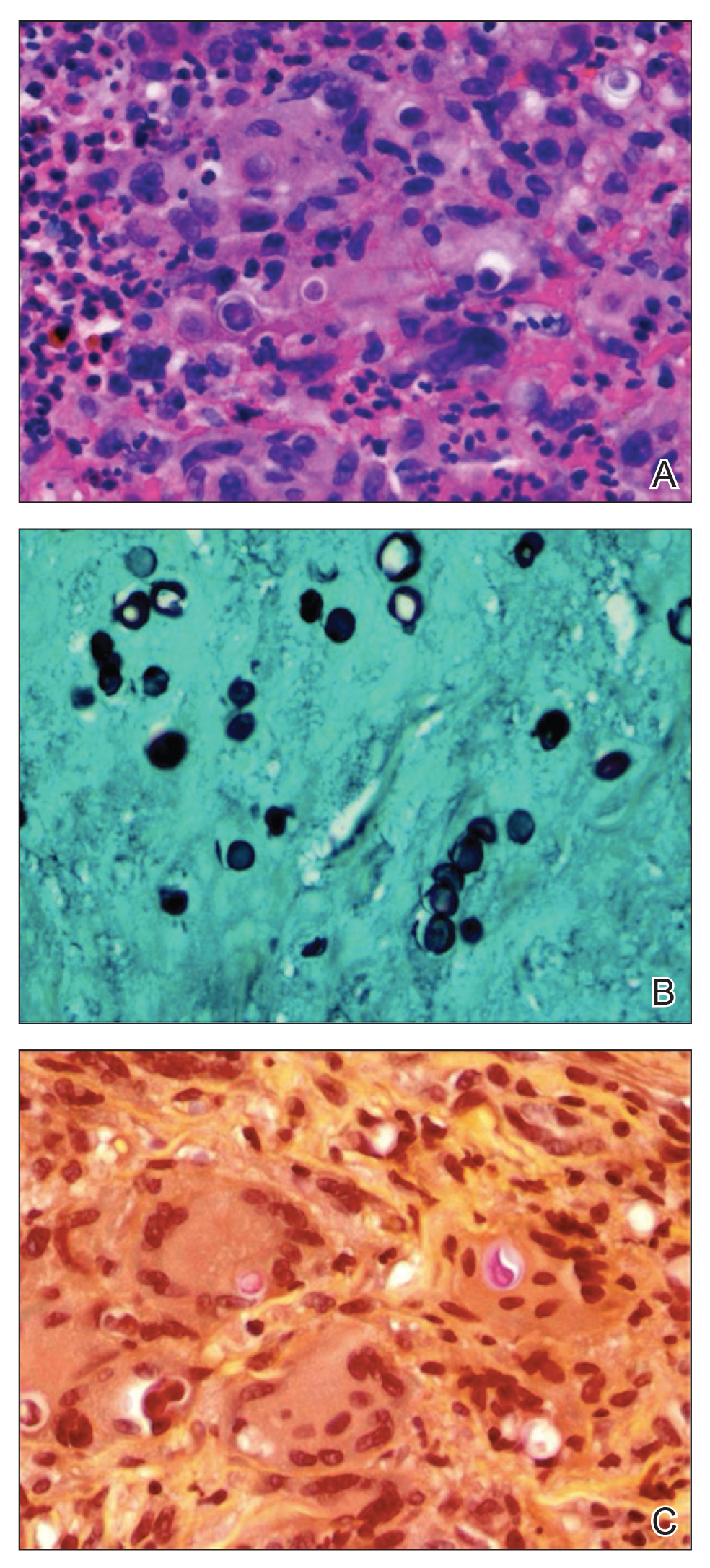

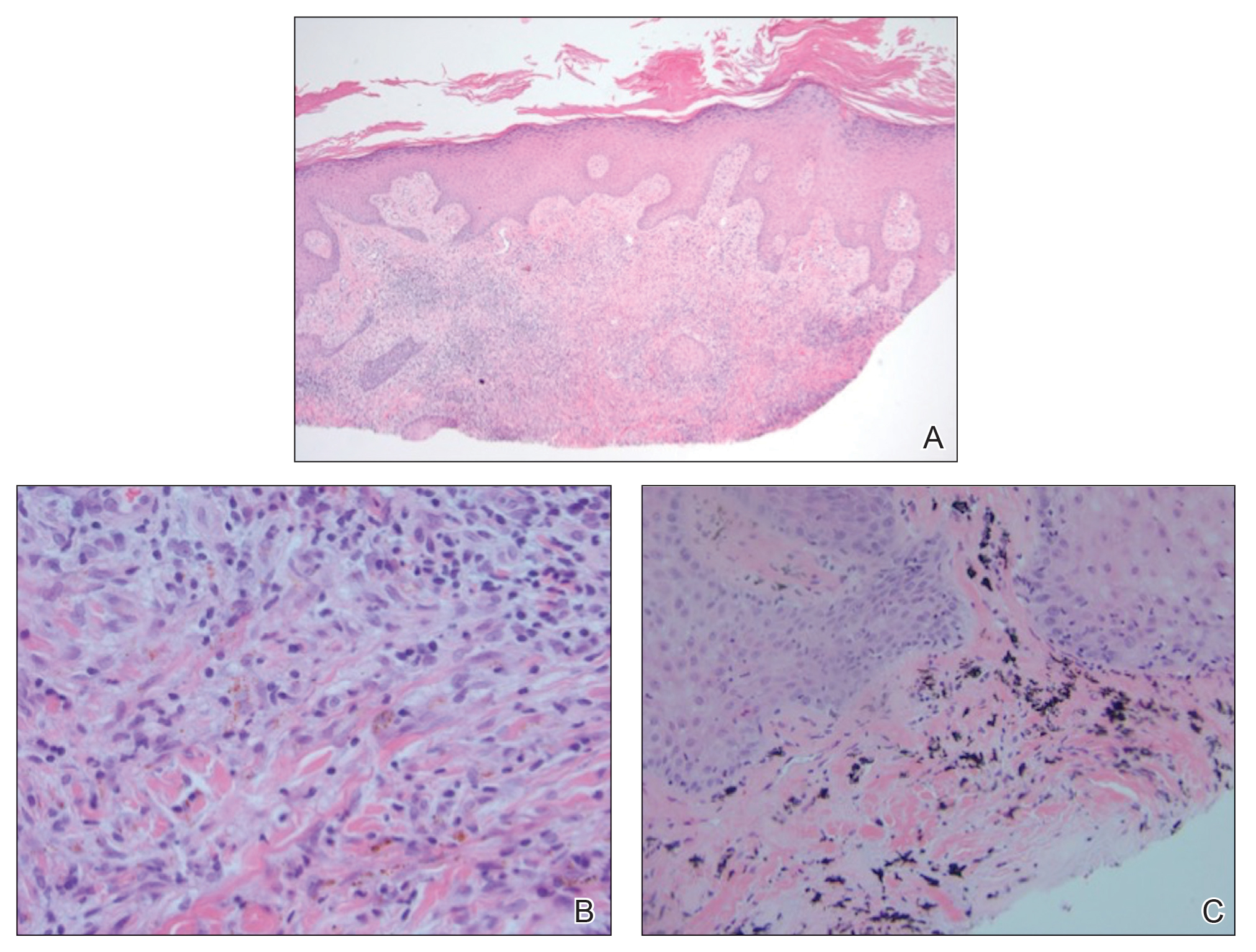

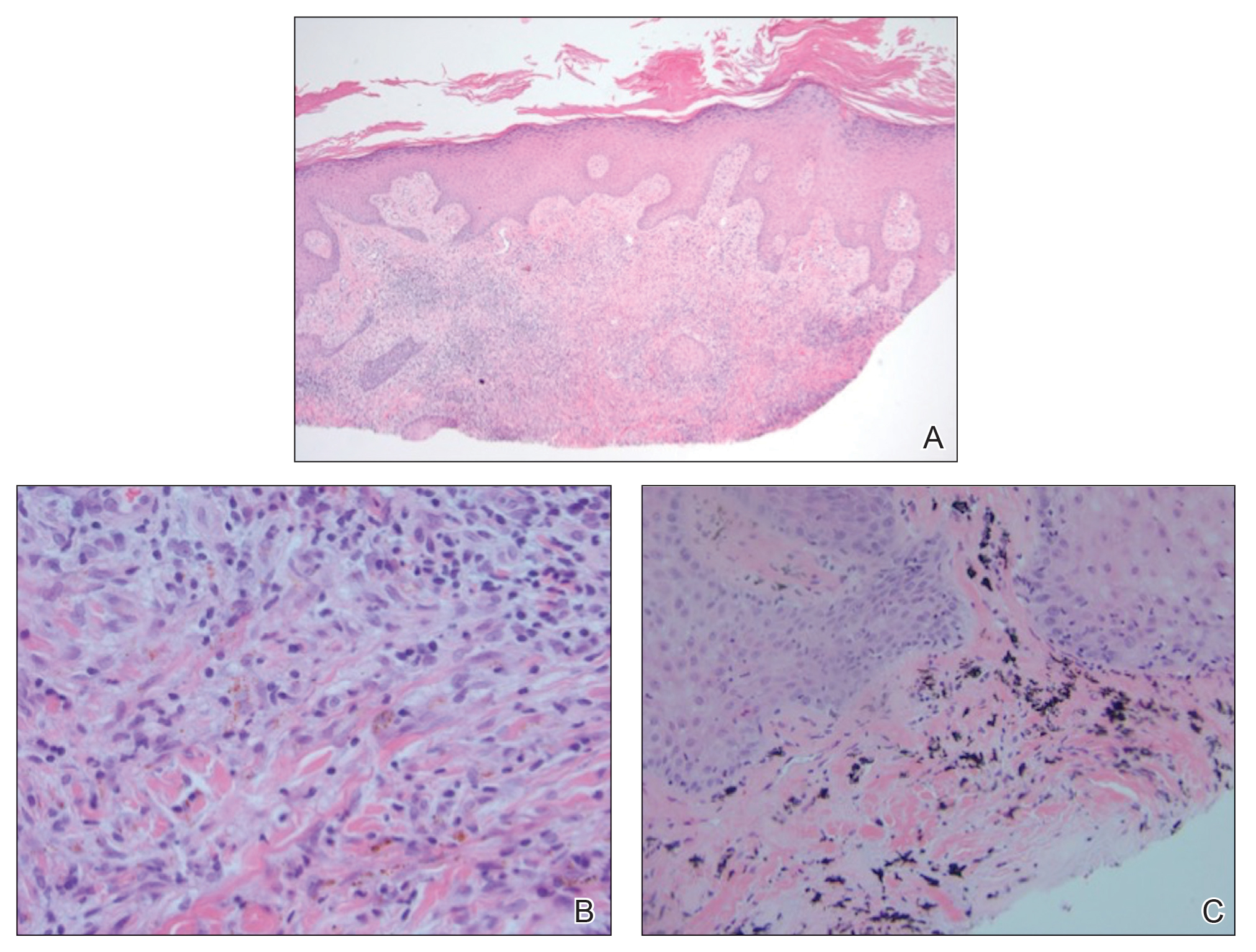

Punch biopsy from the upper back revealed a mixed acute and granulomatous infiltrate with numerous yeast forms (Figure 4A) that were highlighted by Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (Figure 4B) and periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 4C) stains.

The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin with improvement in skin lesions. A healing ointment and occlusive dressing were used on eroded skin lesions. The patient was discharged on oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6 months (for blastomycosis); oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 15 mg/kg/d every 8 hours for 21 days (for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis); oral azithromycin 500 mg daily (for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare prophylaxis); oral levetiracetam 500 mg every 12 hours (as an antiseizure agent); albuterol 90 µg per actuation; and healing ointment. He continues his chemical dependency program and is being followed by the neurology seizure clinic as well as the outpatient HIV infectious disease clinic for planned reinitiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Comment

Diagnosis

Our patient had an interesting and dramatic presentation of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis that was initially considered to be secondary syphilis because of involvement of the palms and soles and the presence of the painless penile ulcer. In addition, the initial skin biopsy finding was considered morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans based on positive Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains and an equivocal mucicarmine stain. However, the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin and positive urine histoplasmosis antigen strongly suggested blastomycosis, which was confirmed by culture of B dermatitidis. The urine histoplasmosis antigen can cross-react with B dermatitidis and other mycoses (eg, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Penicillium marneffei); however, because the treatment of either of these mycoses is similar, the value of the test remains high.1

Skin tests and serologic markers are useful epidemiologic tools but are of inadequate sensitivity and specificity to be diagnostic for B dermatitidis. Diagnosis depends on direct examination of tissue or isolation of the fungus in culture.2

Source of Infection

The probable occult source of cutaneous infection was the lungs, given the natural history of disseminated blastomycosis; the history of cough and chest discomfort; the widespread nature of skin lesions; and the ultimate growth of rare yeast forms in sputum. Cutaneous infection generally is from disseminated disease and rarely from direct inoculation.

Unlike many other systemic dimorphic mycoses, blastomycosis usually occurs in healthy hosts and is frequently associated with point-source outbreak. Immunosuppressed patients typically develop infection following exposure to the organism, but reactivation also can occur. Blastomycosis is uncommon among HIV-infected individuals and is not recognized as an AIDS-defining illness.

In a review from Canada of 133 patients with blastomycosis, nearly half had an underlying medical condition but not one typically associated with marked immunosuppression.3 Only 2 of 133 patients had HIV infection. Overall mortality was 6.3%, and the average duration of symptoms before diagnosis was less in those who died vs those who survived the disease.3 In the setting of AIDS or other marked immunosuppression, disease usually is more severe, with multiple-system involvement, including the CNS, and can progress rapidly to death.2

Treatment

Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent. There are no randomized, blinded trials comparing antifungal agents, and data on the treatment of blastomycosis in patients infected with HIV are limited. Amphotericin B 3 mg/kg every 24 hours is recommended in life-threatening systemic disease and CNS disease as well as in patients with immune suppression, including AIDS.4 In a retrospective study of 326 patients with blastomycosis, those receiving amphotericin B had a cure rate of 86.5% with a relapse rate of 3.9%; patients receiving ketoconazole had a cure rate of 81.7% with a relapse rate of 14%.4 Although data are limited, chronic suppressive therapy generally is recommended in patients with HIV who have been treated for blastomycosis. Fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole are all used as chronic suppressive therapy; however, given the higher relapse rate observed with ketoconazole, itraconazole is preferred. Because neither ketoconazole nor itraconazole penetrates the blood-brain barrier, these drugs are not recommended in cases of CNS involvement. Patients with CNS disease or intolerance to itraconazole should be treated with fluconazole for chronic suppression.3

- Wheat J, Wheat H, Connolly P, et al. Cross-reactivity in Histoplasma capsulatum variety capsulatum antigen assays of urine samples from patients with endemic mycoses. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1169-1171.

- Pappas PG, Pottage JC, Powderly WG, et al. Blastomycosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:847-853.

- Crampton TL, Light RB, Berg GM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1310-1316. Cited by: Aberg JA. Blastomycosis and HIV. HIV In Site Knowledge Base Chapter. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-05-02-09#SIX. Published April 2003. Updated January 2006. Accessed December 16, 2019.

- Chapman SW, Bradsher RW Jr, Campbell GD Jr, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:679-683.

Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal infection that is endemic in the South Central, Midwest, and southeastern regions of the United States, as well as in provinces of Canada bordering the Great Lakes. After inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis spores, which are taken up by bronchopulmonary macrophages, there is an approximate 30- to 45-day incubation period. The initial response at the infected site is suppurative, which progresses to granuloma formation. Blastomyces dermatitidis most commonly infects the lungs, followed by the skin, bones, prostate, and central nervous system (CNS). Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent.

We present the case of a 38-year-old man with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS who reported a 3- to 4-week history of respiratory and cutaneous symptoms. Initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis; however, after laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment for syphilis, further investigation revealed a diagnosis of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis.

Case Report

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of HIV infection and AIDS presented to the emergency department at a medical center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with a cough; chest discomfort; and concomitant nonpainful, mildly pruritic papules and plaques of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration that initially appeared on the face and ears and spread to the trunk, arms, palms, legs, and feet. He had a nonpainful ulcer on the glans penis. Symptoms began while he was living in Atlanta, Georgia, before relocating to Minneapolis. A chest radiograph was negative.

The initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis. Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million U) weekly for 3 weeks was initiated by the primary care team based on clinical suspicion alone without laboratory evidence of a positive rapid plasma reagin or VDRL test. Because laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment did not support syphilis, dermatology consultation was requested.

The patient had a history of crack cocaine abuse. He reported sexual activity with a single female partner while living in a halfway house in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. Physical examination showed an age-appropriate man in no acute distress who was alert and oriented. He had well-demarcated papules and plaques on the forehead, ears, nose, cutaneous and mucosal lips, chest, back, arms, legs, palms, and soles. Many of the facial papules were pink, nonscaly, and concentrated around the nose and mouth; some were umbilicated (Figure 1). Trunk and extensor papules and plaques were well demarcated, oval, and scaly; some had erosions centrally and were excoriated. Palmar papules were round and had peripheral brown hyperpigmentation and central scale (Figure 2). A 1-cm, shallow, nontender, oval ulceration withraised borders was located on the glans penis under the foreskin (Figure 3).

A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive; a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test was negative. Chest radiograph, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalogram were normal. In addition, spinal fluid drawn from a tap was negative on India ink and Gram stain preparations and was negative for cryptococcal antigen. In addition, spinal fluid was negative for fungal and bacterial growth, as were blood cultures.

Abnormal tests included a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot test for HIV, with an absolute CD4 count of 6 cells/mL and a viral load more than 100,000 copies/mL. Urine histoplasmosis antigen was markedly elevated. A potassium hydroxide preparation was performed on the skin of the right forearm, revealing broad-based budding yeast, later confirmed on skin and sputum cultures to be B dermatitidis.

Punch biopsy from the upper back revealed a mixed acute and granulomatous infiltrate with numerous yeast forms (Figure 4A) that were highlighted by Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (Figure 4B) and periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 4C) stains.

The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin with improvement in skin lesions. A healing ointment and occlusive dressing were used on eroded skin lesions. The patient was discharged on oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6 months (for blastomycosis); oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 15 mg/kg/d every 8 hours for 21 days (for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis); oral azithromycin 500 mg daily (for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare prophylaxis); oral levetiracetam 500 mg every 12 hours (as an antiseizure agent); albuterol 90 µg per actuation; and healing ointment. He continues his chemical dependency program and is being followed by the neurology seizure clinic as well as the outpatient HIV infectious disease clinic for planned reinitiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Comment

Diagnosis

Our patient had an interesting and dramatic presentation of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis that was initially considered to be secondary syphilis because of involvement of the palms and soles and the presence of the painless penile ulcer. In addition, the initial skin biopsy finding was considered morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans based on positive Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains and an equivocal mucicarmine stain. However, the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin and positive urine histoplasmosis antigen strongly suggested blastomycosis, which was confirmed by culture of B dermatitidis. The urine histoplasmosis antigen can cross-react with B dermatitidis and other mycoses (eg, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Penicillium marneffei); however, because the treatment of either of these mycoses is similar, the value of the test remains high.1

Skin tests and serologic markers are useful epidemiologic tools but are of inadequate sensitivity and specificity to be diagnostic for B dermatitidis. Diagnosis depends on direct examination of tissue or isolation of the fungus in culture.2

Source of Infection

The probable occult source of cutaneous infection was the lungs, given the natural history of disseminated blastomycosis; the history of cough and chest discomfort; the widespread nature of skin lesions; and the ultimate growth of rare yeast forms in sputum. Cutaneous infection generally is from disseminated disease and rarely from direct inoculation.

Unlike many other systemic dimorphic mycoses, blastomycosis usually occurs in healthy hosts and is frequently associated with point-source outbreak. Immunosuppressed patients typically develop infection following exposure to the organism, but reactivation also can occur. Blastomycosis is uncommon among HIV-infected individuals and is not recognized as an AIDS-defining illness.

In a review from Canada of 133 patients with blastomycosis, nearly half had an underlying medical condition but not one typically associated with marked immunosuppression.3 Only 2 of 133 patients had HIV infection. Overall mortality was 6.3%, and the average duration of symptoms before diagnosis was less in those who died vs those who survived the disease.3 In the setting of AIDS or other marked immunosuppression, disease usually is more severe, with multiple-system involvement, including the CNS, and can progress rapidly to death.2

Treatment

Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent. There are no randomized, blinded trials comparing antifungal agents, and data on the treatment of blastomycosis in patients infected with HIV are limited. Amphotericin B 3 mg/kg every 24 hours is recommended in life-threatening systemic disease and CNS disease as well as in patients with immune suppression, including AIDS.4 In a retrospective study of 326 patients with blastomycosis, those receiving amphotericin B had a cure rate of 86.5% with a relapse rate of 3.9%; patients receiving ketoconazole had a cure rate of 81.7% with a relapse rate of 14%.4 Although data are limited, chronic suppressive therapy generally is recommended in patients with HIV who have been treated for blastomycosis. Fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole are all used as chronic suppressive therapy; however, given the higher relapse rate observed with ketoconazole, itraconazole is preferred. Because neither ketoconazole nor itraconazole penetrates the blood-brain barrier, these drugs are not recommended in cases of CNS involvement. Patients with CNS disease or intolerance to itraconazole should be treated with fluconazole for chronic suppression.3

Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal infection that is endemic in the South Central, Midwest, and southeastern regions of the United States, as well as in provinces of Canada bordering the Great Lakes. After inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis spores, which are taken up by bronchopulmonary macrophages, there is an approximate 30- to 45-day incubation period. The initial response at the infected site is suppurative, which progresses to granuloma formation. Blastomyces dermatitidis most commonly infects the lungs, followed by the skin, bones, prostate, and central nervous system (CNS). Therapy for blastomycosis is determined by the severity of the clinical presentation and consideration of the toxicities of the antifungal agent.

We present the case of a 38-year-old man with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS who reported a 3- to 4-week history of respiratory and cutaneous symptoms. Initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis; however, after laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment for syphilis, further investigation revealed a diagnosis of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis.

Case Report

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of HIV infection and AIDS presented to the emergency department at a medical center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, with a cough; chest discomfort; and concomitant nonpainful, mildly pruritic papules and plaques of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration that initially appeared on the face and ears and spread to the trunk, arms, palms, legs, and feet. He had a nonpainful ulcer on the glans penis. Symptoms began while he was living in Atlanta, Georgia, before relocating to Minneapolis. A chest radiograph was negative.

The initial clinical impression favored secondary syphilis. Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million U) weekly for 3 weeks was initiated by the primary care team based on clinical suspicion alone without laboratory evidence of a positive rapid plasma reagin or VDRL test. Because laboratory evaluation and lack of response to treatment did not support syphilis, dermatology consultation was requested.

The patient had a history of crack cocaine abuse. He reported sexual activity with a single female partner while living in a halfway house in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. Physical examination showed an age-appropriate man in no acute distress who was alert and oriented. He had well-demarcated papules and plaques on the forehead, ears, nose, cutaneous and mucosal lips, chest, back, arms, legs, palms, and soles. Many of the facial papules were pink, nonscaly, and concentrated around the nose and mouth; some were umbilicated (Figure 1). Trunk and extensor papules and plaques were well demarcated, oval, and scaly; some had erosions centrally and were excoriated. Palmar papules were round and had peripheral brown hyperpigmentation and central scale (Figure 2). A 1-cm, shallow, nontender, oval ulceration withraised borders was located on the glans penis under the foreskin (Figure 3).

A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive; a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test was negative. Chest radiograph, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalogram were normal. In addition, spinal fluid drawn from a tap was negative on India ink and Gram stain preparations and was negative for cryptococcal antigen. In addition, spinal fluid was negative for fungal and bacterial growth, as were blood cultures.

Abnormal tests included a positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot test for HIV, with an absolute CD4 count of 6 cells/mL and a viral load more than 100,000 copies/mL. Urine histoplasmosis antigen was markedly elevated. A potassium hydroxide preparation was performed on the skin of the right forearm, revealing broad-based budding yeast, later confirmed on skin and sputum cultures to be B dermatitidis.

Punch biopsy from the upper back revealed a mixed acute and granulomatous infiltrate with numerous yeast forms (Figure 4A) that were highlighted by Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver (Figure 4B) and periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 4C) stains.

The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin with improvement in skin lesions. A healing ointment and occlusive dressing were used on eroded skin lesions. The patient was discharged on oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6 months (for blastomycosis); oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 15 mg/kg/d every 8 hours for 21 days (for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis); oral azithromycin 500 mg daily (for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare prophylaxis); oral levetiracetam 500 mg every 12 hours (as an antiseizure agent); albuterol 90 µg per actuation; and healing ointment. He continues his chemical dependency program and is being followed by the neurology seizure clinic as well as the outpatient HIV infectious disease clinic for planned reinitiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Comment

Diagnosis

Our patient had an interesting and dramatic presentation of widespread cutaneous North American blastomycosis that was initially considered to be secondary syphilis because of involvement of the palms and soles and the presence of the painless penile ulcer. In addition, the initial skin biopsy finding was considered morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans based on positive Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains and an equivocal mucicarmine stain. However, the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin and positive urine histoplasmosis antigen strongly suggested blastomycosis, which was confirmed by culture of B dermatitidis. The urine histoplasmosis antigen can cross-react with B dermatitidis and other mycoses (eg, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Penicillium marneffei); however, because the treatment of either of these mycoses is similar, the value of the test remains high.1

Skin tests and serologic markers are useful epidemiologic tools but are of inadequate sensitivity and specificity to be diagnostic for B dermatitidis. Diagnosis depends on direct examination of tissue or isolation of the fungus in culture.2

Source of Infection

The probable occult source of cutaneous infection was the lungs, given the natural history of disseminated blastomycosis; the history of cough and chest discomfort; the widespread nature of skin lesions; and the ultimate growth of rare yeast forms in sputum. Cutaneous infection generally is from disseminated disease and rarely from direct inoculation.

Unlike many other systemic dimorphic mycoses, blastomycosis usually occurs in healthy hosts and is frequently associated with point-source outbreak. Immunosuppressed patients typically develop infection following exposure to the organism, but reactivation also can occur. Blastomycosis is uncommon among HIV-infected individuals and is not recognized as an AIDS-defining illness.

In a review from Canada of 133 patients with blastomycosis, nearly half had an underlying medical condition but not one typically associated with marked immunosuppression.3 Only 2 of 133 patients had HIV infection. Overall mortality was 6.3%, and the average duration of symptoms before diagnosis was less in those who died vs those who survived the disease.3 In the setting of AIDS or other marked immunosuppression, disease usually is more severe, with multiple-system involvement, including the CNS, and can progress rapidly to death.2