User login

New test edges closer to rapid, accurate ID of active TB

A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection, according to investigators.

, reported lead author Rushdy Ahmad, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues. When fully developed, such a test could improve interventions for the most vulnerable patients, such as those with HIV, among whom TB often goes undiagnosed.

“Rapid and accurate diagnosis of active TB with current sputum-based diagnostic tools remains challenging in high-burden, resource-limited settings,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

They went on to explain the gap that currently exists between microscopy, which is operator dependent and insensitive, and newer technologies, such as nucleic acid amplification, which are more sensitive but heavily resource dependent. “Furthermore, two of the most vulnerable and highly affected groups – young children and adults with HIV infection – are unlikely to be diagnosed using sputum because of difficulty obtaining sputum and low bacillary loads in the sample.”

To look for a more practical option, the investigators drew blood from 406 patients with chronic cough. Then, using a bead-based immunoassay with machine learning, the investigators identified four blood proteins associated with active TB infection: interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-18, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Blind validation of 317 samples from patients with chronic cough in Asia, Africa, and South America showed that the four biomarkers offered a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65%. By adding a fifth biomarker, an antibody against TB antigen Ag85B, the investigators were able to raise accuracy figures to 86% sensitivity and 69% specificity.

Adding even more biomarkers could theoretically raise accuracy even further, according to the investigators. The WHO minimal performance thresholds are 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity, with optimal targets slightly higher, at 95% sensitivity and 80% specificity. Although these standards have not yet been met, the investigators plan on testing the existing assay in real-world scenarios while simultaneously aiming to make it better.

“A near-term goal is ... to incrementally improve the marker panel up to an anticipated 6- to 10-plex assay,” the investigators wrote. “However, given the urgency of the problem, the possibility of incremental improvements will not delay platform refinement and field testing.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported additional relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

SOURCE: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection, according to investigators.

, reported lead author Rushdy Ahmad, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues. When fully developed, such a test could improve interventions for the most vulnerable patients, such as those with HIV, among whom TB often goes undiagnosed.

“Rapid and accurate diagnosis of active TB with current sputum-based diagnostic tools remains challenging in high-burden, resource-limited settings,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

They went on to explain the gap that currently exists between microscopy, which is operator dependent and insensitive, and newer technologies, such as nucleic acid amplification, which are more sensitive but heavily resource dependent. “Furthermore, two of the most vulnerable and highly affected groups – young children and adults with HIV infection – are unlikely to be diagnosed using sputum because of difficulty obtaining sputum and low bacillary loads in the sample.”

To look for a more practical option, the investigators drew blood from 406 patients with chronic cough. Then, using a bead-based immunoassay with machine learning, the investigators identified four blood proteins associated with active TB infection: interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-18, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Blind validation of 317 samples from patients with chronic cough in Asia, Africa, and South America showed that the four biomarkers offered a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65%. By adding a fifth biomarker, an antibody against TB antigen Ag85B, the investigators were able to raise accuracy figures to 86% sensitivity and 69% specificity.

Adding even more biomarkers could theoretically raise accuracy even further, according to the investigators. The WHO minimal performance thresholds are 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity, with optimal targets slightly higher, at 95% sensitivity and 80% specificity. Although these standards have not yet been met, the investigators plan on testing the existing assay in real-world scenarios while simultaneously aiming to make it better.

“A near-term goal is ... to incrementally improve the marker panel up to an anticipated 6- to 10-plex assay,” the investigators wrote. “However, given the urgency of the problem, the possibility of incremental improvements will not delay platform refinement and field testing.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported additional relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

SOURCE: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection, according to investigators.

, reported lead author Rushdy Ahmad, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass., and colleagues. When fully developed, such a test could improve interventions for the most vulnerable patients, such as those with HIV, among whom TB often goes undiagnosed.

“Rapid and accurate diagnosis of active TB with current sputum-based diagnostic tools remains challenging in high-burden, resource-limited settings,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Science Translational Medicine.

They went on to explain the gap that currently exists between microscopy, which is operator dependent and insensitive, and newer technologies, such as nucleic acid amplification, which are more sensitive but heavily resource dependent. “Furthermore, two of the most vulnerable and highly affected groups – young children and adults with HIV infection – are unlikely to be diagnosed using sputum because of difficulty obtaining sputum and low bacillary loads in the sample.”

To look for a more practical option, the investigators drew blood from 406 patients with chronic cough. Then, using a bead-based immunoassay with machine learning, the investigators identified four blood proteins associated with active TB infection: interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-18, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Blind validation of 317 samples from patients with chronic cough in Asia, Africa, and South America showed that the four biomarkers offered a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 65%. By adding a fifth biomarker, an antibody against TB antigen Ag85B, the investigators were able to raise accuracy figures to 86% sensitivity and 69% specificity.

Adding even more biomarkers could theoretically raise accuracy even further, according to the investigators. The WHO minimal performance thresholds are 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity, with optimal targets slightly higher, at 95% sensitivity and 80% specificity. Although these standards have not yet been met, the investigators plan on testing the existing assay in real-world scenarios while simultaneously aiming to make it better.

“A near-term goal is ... to incrementally improve the marker panel up to an anticipated 6- to 10-plex assay,” the investigators wrote. “However, given the urgency of the problem, the possibility of incremental improvements will not delay platform refinement and field testing.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported additional relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

SOURCE: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A new point-of-care assay designed with machine learning offers improved accuracy for rapid identification of active tuberculosis (TB) infection.

Major finding: The assay had a sensitivity of 86%.

Study details: A machine learning and validation study involving patients with chronic cough from multiple countries.

Disclosures: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported relationships with Quanterix Corporation and FIND.

Source: Ahmad et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8287.

Rare mixed HCV genotypes found in men who have sex with men

A low percentage of mixed genotypes of hepatitis C virus (HCV) was found in a small study of recently infected HIV+ and HIV– men who have sex with men (MSM) according to a report by Thuy Nguyen, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents.

The researchers assessed 58 HCV-infected individuals with a median age of 38.5 years, 50 of whom were HIV positive and 18 of whom were HIV negative. Most of the patients were MSM (85.3%), with the rest of unknown sexual orientation. HCV genotyping by Sanger found types GT1a, GT4d, GT3a, and GT2k infection in 47.1%, 41.2%, 8.8%, and 2.9% of the individuals.

After eliminating suspected contaminations, three patients (4.4%) were found with mixed GT infections All three patients were infected with HCV for the first time; two-thirds were coinfected with HIV. The mixed GTs comprised only GT4d and GT1a at different ratios. Mixed infections are potentially problematic when using direct-acting antiviral therapy without broad-spectrum activity, according to the researchers. In this case, however, all HCV patients achieved treatment success.

“From a public health perspective, the MSM population engaging in high-risk behaviors still requires special attention in terms of mixed infections compared with the general HCV-infected population with a regular monitoring of anti-HCV treatment response, particularly when pangenotypic treatment is not used,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the French government; the authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Nguyen T et al. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 2019. 54[4]:523-7.

A low percentage of mixed genotypes of hepatitis C virus (HCV) was found in a small study of recently infected HIV+ and HIV– men who have sex with men (MSM) according to a report by Thuy Nguyen, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents.

The researchers assessed 58 HCV-infected individuals with a median age of 38.5 years, 50 of whom were HIV positive and 18 of whom were HIV negative. Most of the patients were MSM (85.3%), with the rest of unknown sexual orientation. HCV genotyping by Sanger found types GT1a, GT4d, GT3a, and GT2k infection in 47.1%, 41.2%, 8.8%, and 2.9% of the individuals.

After eliminating suspected contaminations, three patients (4.4%) were found with mixed GT infections All three patients were infected with HCV for the first time; two-thirds were coinfected with HIV. The mixed GTs comprised only GT4d and GT1a at different ratios. Mixed infections are potentially problematic when using direct-acting antiviral therapy without broad-spectrum activity, according to the researchers. In this case, however, all HCV patients achieved treatment success.

“From a public health perspective, the MSM population engaging in high-risk behaviors still requires special attention in terms of mixed infections compared with the general HCV-infected population with a regular monitoring of anti-HCV treatment response, particularly when pangenotypic treatment is not used,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the French government; the authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Nguyen T et al. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 2019. 54[4]:523-7.

A low percentage of mixed genotypes of hepatitis C virus (HCV) was found in a small study of recently infected HIV+ and HIV– men who have sex with men (MSM) according to a report by Thuy Nguyen, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents.

The researchers assessed 58 HCV-infected individuals with a median age of 38.5 years, 50 of whom were HIV positive and 18 of whom were HIV negative. Most of the patients were MSM (85.3%), with the rest of unknown sexual orientation. HCV genotyping by Sanger found types GT1a, GT4d, GT3a, and GT2k infection in 47.1%, 41.2%, 8.8%, and 2.9% of the individuals.

After eliminating suspected contaminations, three patients (4.4%) were found with mixed GT infections All three patients were infected with HCV for the first time; two-thirds were coinfected with HIV. The mixed GTs comprised only GT4d and GT1a at different ratios. Mixed infections are potentially problematic when using direct-acting antiviral therapy without broad-spectrum activity, according to the researchers. In this case, however, all HCV patients achieved treatment success.

“From a public health perspective, the MSM population engaging in high-risk behaviors still requires special attention in terms of mixed infections compared with the general HCV-infected population with a regular monitoring of anti-HCV treatment response, particularly when pangenotypic treatment is not used,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the French government; the authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Nguyen T et al. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 2019. 54[4]:523-7.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS

Vitamin C–based regimens in sepsis plausible, need more data, expert says

NEW ORLEANS – While further data are awaited on the role of vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids in sepsis, there is at least biologic plausibility for using the combination, and clinical equipoise that supports continued enrollment of patients in the ongoing randomized, controlled VICTAS trial, according to that study’s principal investigator.

“There is tremendous biologic plausibility for giving vitamin C in sepsis,” said Jon Sevransky, MD, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. But until more data are available on vitamin C–based regimens, those who choose to use vitamin C with thiamine and steroids in this setting need to ensure that glucose is being measured appropriately, he warned.

“If you decide that vitamin C is right for your patient, prior to having enough data – so if you’re doing a Hail Mary, or a ‘this patient is sick, and it’s probably not going to hurt them’ – please make sure that you measure your glucose with something that uses whole blood, which is either a blood gas or sending it down to the core lab, because otherwise, you might get an inaccurate result,” Dr. Sevransky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Results from the randomized, placebo-controlled Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Steroids in Sepsis (VICTAS) trial may be available within the next few months, according to Dr. Sevransky, who noted that the trial was funded for 500 patients, which provides an 80% probability of showing an absolute risk reduction of 10% in mortality.

The primary endpoint of the phase 3 trial is vasopressor and ventilator-free days at 30 days after randomization, while 30-day mortality has been described as “the key secondary outcome” by Dr. Sevransky and colleagues in a recent report on the trial design.

Clinicians have been “captivated” by the potential benefit of vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, as published in CHEST in June 2017, Dr. Sevransky said. In that study, reported by Paul E. Marik, MD, and colleagues, hospital mortality was 8.5% for the treatment group, versus 40.4% in the control group, a significant difference.

That retrospective, single-center study had a number of limitations, however, including its before-and-after design and the use of steroids in the comparator arm. In addition, little information was available on antibiotics or fluids given at the time of the intervention, according to Dr. Sevransky.

In results of the CITRIS-ALI randomized clinical trial, just published in JAMA, intravenous administration of high-dose vitamin C in patients with sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) failed to significantly reduce organ failure scores or biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury.

In an exploratory analysis of CITRIS-ALI, mortality at day 28 was 29.8% for the treatment group and 46.3% for placebo, with a statistically significant difference between Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the two arms, according to the investigators.

That exploratory result from CITRIS-ALI, however, is indicative of “something that needs further study,” Dr. Sevransky cautioned. “In summary, I hope I told you that biologic plausibility is present for vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids. I think that, and this is my own personal opinion, that evidence to date allows for randomization of patients, that there’s current equipoise.”

Dr. Sevransky disclosed current grant support from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the Marcus Foundation, as well as a stipend from Critical Care Medicine related to work as an associate editor. He is also a medical advisor to Project Hope and ARDS Foundation and a member of the Surviving Sepsis guideline committees.

SOURCE: Sevransky J et al. Chest 2019.

NEW ORLEANS – While further data are awaited on the role of vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids in sepsis, there is at least biologic plausibility for using the combination, and clinical equipoise that supports continued enrollment of patients in the ongoing randomized, controlled VICTAS trial, according to that study’s principal investigator.

“There is tremendous biologic plausibility for giving vitamin C in sepsis,” said Jon Sevransky, MD, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. But until more data are available on vitamin C–based regimens, those who choose to use vitamin C with thiamine and steroids in this setting need to ensure that glucose is being measured appropriately, he warned.

“If you decide that vitamin C is right for your patient, prior to having enough data – so if you’re doing a Hail Mary, or a ‘this patient is sick, and it’s probably not going to hurt them’ – please make sure that you measure your glucose with something that uses whole blood, which is either a blood gas or sending it down to the core lab, because otherwise, you might get an inaccurate result,” Dr. Sevransky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Results from the randomized, placebo-controlled Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Steroids in Sepsis (VICTAS) trial may be available within the next few months, according to Dr. Sevransky, who noted that the trial was funded for 500 patients, which provides an 80% probability of showing an absolute risk reduction of 10% in mortality.

The primary endpoint of the phase 3 trial is vasopressor and ventilator-free days at 30 days after randomization, while 30-day mortality has been described as “the key secondary outcome” by Dr. Sevransky and colleagues in a recent report on the trial design.

Clinicians have been “captivated” by the potential benefit of vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, as published in CHEST in June 2017, Dr. Sevransky said. In that study, reported by Paul E. Marik, MD, and colleagues, hospital mortality was 8.5% for the treatment group, versus 40.4% in the control group, a significant difference.

That retrospective, single-center study had a number of limitations, however, including its before-and-after design and the use of steroids in the comparator arm. In addition, little information was available on antibiotics or fluids given at the time of the intervention, according to Dr. Sevransky.

In results of the CITRIS-ALI randomized clinical trial, just published in JAMA, intravenous administration of high-dose vitamin C in patients with sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) failed to significantly reduce organ failure scores or biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury.

In an exploratory analysis of CITRIS-ALI, mortality at day 28 was 29.8% for the treatment group and 46.3% for placebo, with a statistically significant difference between Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the two arms, according to the investigators.

That exploratory result from CITRIS-ALI, however, is indicative of “something that needs further study,” Dr. Sevransky cautioned. “In summary, I hope I told you that biologic plausibility is present for vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids. I think that, and this is my own personal opinion, that evidence to date allows for randomization of patients, that there’s current equipoise.”

Dr. Sevransky disclosed current grant support from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the Marcus Foundation, as well as a stipend from Critical Care Medicine related to work as an associate editor. He is also a medical advisor to Project Hope and ARDS Foundation and a member of the Surviving Sepsis guideline committees.

SOURCE: Sevransky J et al. Chest 2019.

NEW ORLEANS – While further data are awaited on the role of vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids in sepsis, there is at least biologic plausibility for using the combination, and clinical equipoise that supports continued enrollment of patients in the ongoing randomized, controlled VICTAS trial, according to that study’s principal investigator.

“There is tremendous biologic plausibility for giving vitamin C in sepsis,” said Jon Sevransky, MD, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. But until more data are available on vitamin C–based regimens, those who choose to use vitamin C with thiamine and steroids in this setting need to ensure that glucose is being measured appropriately, he warned.

“If you decide that vitamin C is right for your patient, prior to having enough data – so if you’re doing a Hail Mary, or a ‘this patient is sick, and it’s probably not going to hurt them’ – please make sure that you measure your glucose with something that uses whole blood, which is either a blood gas or sending it down to the core lab, because otherwise, you might get an inaccurate result,” Dr. Sevransky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Results from the randomized, placebo-controlled Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Steroids in Sepsis (VICTAS) trial may be available within the next few months, according to Dr. Sevransky, who noted that the trial was funded for 500 patients, which provides an 80% probability of showing an absolute risk reduction of 10% in mortality.

The primary endpoint of the phase 3 trial is vasopressor and ventilator-free days at 30 days after randomization, while 30-day mortality has been described as “the key secondary outcome” by Dr. Sevransky and colleagues in a recent report on the trial design.

Clinicians have been “captivated” by the potential benefit of vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, as published in CHEST in June 2017, Dr. Sevransky said. In that study, reported by Paul E. Marik, MD, and colleagues, hospital mortality was 8.5% for the treatment group, versus 40.4% in the control group, a significant difference.

That retrospective, single-center study had a number of limitations, however, including its before-and-after design and the use of steroids in the comparator arm. In addition, little information was available on antibiotics or fluids given at the time of the intervention, according to Dr. Sevransky.

In results of the CITRIS-ALI randomized clinical trial, just published in JAMA, intravenous administration of high-dose vitamin C in patients with sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) failed to significantly reduce organ failure scores or biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury.

In an exploratory analysis of CITRIS-ALI, mortality at day 28 was 29.8% for the treatment group and 46.3% for placebo, with a statistically significant difference between Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the two arms, according to the investigators.

That exploratory result from CITRIS-ALI, however, is indicative of “something that needs further study,” Dr. Sevransky cautioned. “In summary, I hope I told you that biologic plausibility is present for vitamin C, thiamine, and steroids. I think that, and this is my own personal opinion, that evidence to date allows for randomization of patients, that there’s current equipoise.”

Dr. Sevransky disclosed current grant support from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the Marcus Foundation, as well as a stipend from Critical Care Medicine related to work as an associate editor. He is also a medical advisor to Project Hope and ARDS Foundation and a member of the Surviving Sepsis guideline committees.

SOURCE: Sevransky J et al. Chest 2019.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CHEST 2019

In-hospital flu shot reduced readmissions in pneumonia patients

NEW ORLEANS – In-hospital flu shots were rare, yet linked to a lower readmission rate for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia in a recent retrospective study, suggesting a “missed opportunity” to improve outcomes for these patients, an investigator said.

Less than 2% of patients admitted for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) received in-hospital influenza vaccination, yet receiving it was linked to a 20% reduction in readmissions, according to investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, a resident at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, New York.

Those patients who were readmitted had a significantly higher death rate vs. index admissions, Dr. Ho said in a poster discussion session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“I know (vaccines) are pretty much pushed out to the outpatient setting, but given what we showed here in this abstract, I think there’s a role for influenza vaccines to be a discussion in the hospital,” Dr. Ho said in his presentation.

The retrospective analysis was based on 825,906 adult hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of CAP in data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Of that large cohort, just 14,047 (1.91%) received in-hospital influenza vaccination, according to Dr. Ho.

In-hospital influenza vaccination independently predicted a lower risk of readmission (hazard ratio, 0.821; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.98; P less than .02) in a propensity score matching analysis that included 9,777 CAP patients who received the vaccination and 9,777 with similar demographic and clinical characteristics.

Private insurance and high-income status also predicted lower risk of readmission in the analysis, while by contrast, factors associated with higher risk of readmission included advanced age, Medicare insurance, and respiratory failure, among other factors, Dr. Ho reported.

The overall 30-day rate of readmission in the study was 11.9%, and of those readmissions, the great majority (about 80%) were due to pneumonia, he said.

The rate of death in the hospital was 2.96% for CAP patients who were readmitted, versus 1.11% for the index admissions (P less than .001), Dr. Ho reported. Moreover, readmissions were associated with nearly half a million hospital days and $1 billion in costs and $3.67 billion in charges.

Based on these findings, Dr. Ho and colleagues hope to incorporate routine influenza vaccination for all adults hospitalized with CAP.

“We’re always under pressure to do so much for patients that we can’t comprehensively do everything. But the 20% reduction in the risk of coming back, I think that’s significant,” Dr. Ho said in an interview.

The authors reported having no disclosures related to this research.

This article was updated 10/23/2019.

SOURCE: Ho KS, et al. CHEST 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.450.

NEW ORLEANS – In-hospital flu shots were rare, yet linked to a lower readmission rate for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia in a recent retrospective study, suggesting a “missed opportunity” to improve outcomes for these patients, an investigator said.

Less than 2% of patients admitted for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) received in-hospital influenza vaccination, yet receiving it was linked to a 20% reduction in readmissions, according to investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, a resident at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, New York.

Those patients who were readmitted had a significantly higher death rate vs. index admissions, Dr. Ho said in a poster discussion session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“I know (vaccines) are pretty much pushed out to the outpatient setting, but given what we showed here in this abstract, I think there’s a role for influenza vaccines to be a discussion in the hospital,” Dr. Ho said in his presentation.

The retrospective analysis was based on 825,906 adult hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of CAP in data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Of that large cohort, just 14,047 (1.91%) received in-hospital influenza vaccination, according to Dr. Ho.

In-hospital influenza vaccination independently predicted a lower risk of readmission (hazard ratio, 0.821; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.98; P less than .02) in a propensity score matching analysis that included 9,777 CAP patients who received the vaccination and 9,777 with similar demographic and clinical characteristics.

Private insurance and high-income status also predicted lower risk of readmission in the analysis, while by contrast, factors associated with higher risk of readmission included advanced age, Medicare insurance, and respiratory failure, among other factors, Dr. Ho reported.

The overall 30-day rate of readmission in the study was 11.9%, and of those readmissions, the great majority (about 80%) were due to pneumonia, he said.

The rate of death in the hospital was 2.96% for CAP patients who were readmitted, versus 1.11% for the index admissions (P less than .001), Dr. Ho reported. Moreover, readmissions were associated with nearly half a million hospital days and $1 billion in costs and $3.67 billion in charges.

Based on these findings, Dr. Ho and colleagues hope to incorporate routine influenza vaccination for all adults hospitalized with CAP.

“We’re always under pressure to do so much for patients that we can’t comprehensively do everything. But the 20% reduction in the risk of coming back, I think that’s significant,” Dr. Ho said in an interview.

The authors reported having no disclosures related to this research.

This article was updated 10/23/2019.

SOURCE: Ho KS, et al. CHEST 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.450.

NEW ORLEANS – In-hospital flu shots were rare, yet linked to a lower readmission rate for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia in a recent retrospective study, suggesting a “missed opportunity” to improve outcomes for these patients, an investigator said.

Less than 2% of patients admitted for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) received in-hospital influenza vaccination, yet receiving it was linked to a 20% reduction in readmissions, according to investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, a resident at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, New York.

Those patients who were readmitted had a significantly higher death rate vs. index admissions, Dr. Ho said in a poster discussion session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“I know (vaccines) are pretty much pushed out to the outpatient setting, but given what we showed here in this abstract, I think there’s a role for influenza vaccines to be a discussion in the hospital,” Dr. Ho said in his presentation.

The retrospective analysis was based on 825,906 adult hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of CAP in data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Of that large cohort, just 14,047 (1.91%) received in-hospital influenza vaccination, according to Dr. Ho.

In-hospital influenza vaccination independently predicted a lower risk of readmission (hazard ratio, 0.821; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.98; P less than .02) in a propensity score matching analysis that included 9,777 CAP patients who received the vaccination and 9,777 with similar demographic and clinical characteristics.

Private insurance and high-income status also predicted lower risk of readmission in the analysis, while by contrast, factors associated with higher risk of readmission included advanced age, Medicare insurance, and respiratory failure, among other factors, Dr. Ho reported.

The overall 30-day rate of readmission in the study was 11.9%, and of those readmissions, the great majority (about 80%) were due to pneumonia, he said.

The rate of death in the hospital was 2.96% for CAP patients who were readmitted, versus 1.11% for the index admissions (P less than .001), Dr. Ho reported. Moreover, readmissions were associated with nearly half a million hospital days and $1 billion in costs and $3.67 billion in charges.

Based on these findings, Dr. Ho and colleagues hope to incorporate routine influenza vaccination for all adults hospitalized with CAP.

“We’re always under pressure to do so much for patients that we can’t comprehensively do everything. But the 20% reduction in the risk of coming back, I think that’s significant,” Dr. Ho said in an interview.

The authors reported having no disclosures related to this research.

This article was updated 10/23/2019.

SOURCE: Ho KS, et al. CHEST 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.450.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Pulmonary Hemorrhage as the Initial Presentation of AIDS-Related Kaposi Sarcoma

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

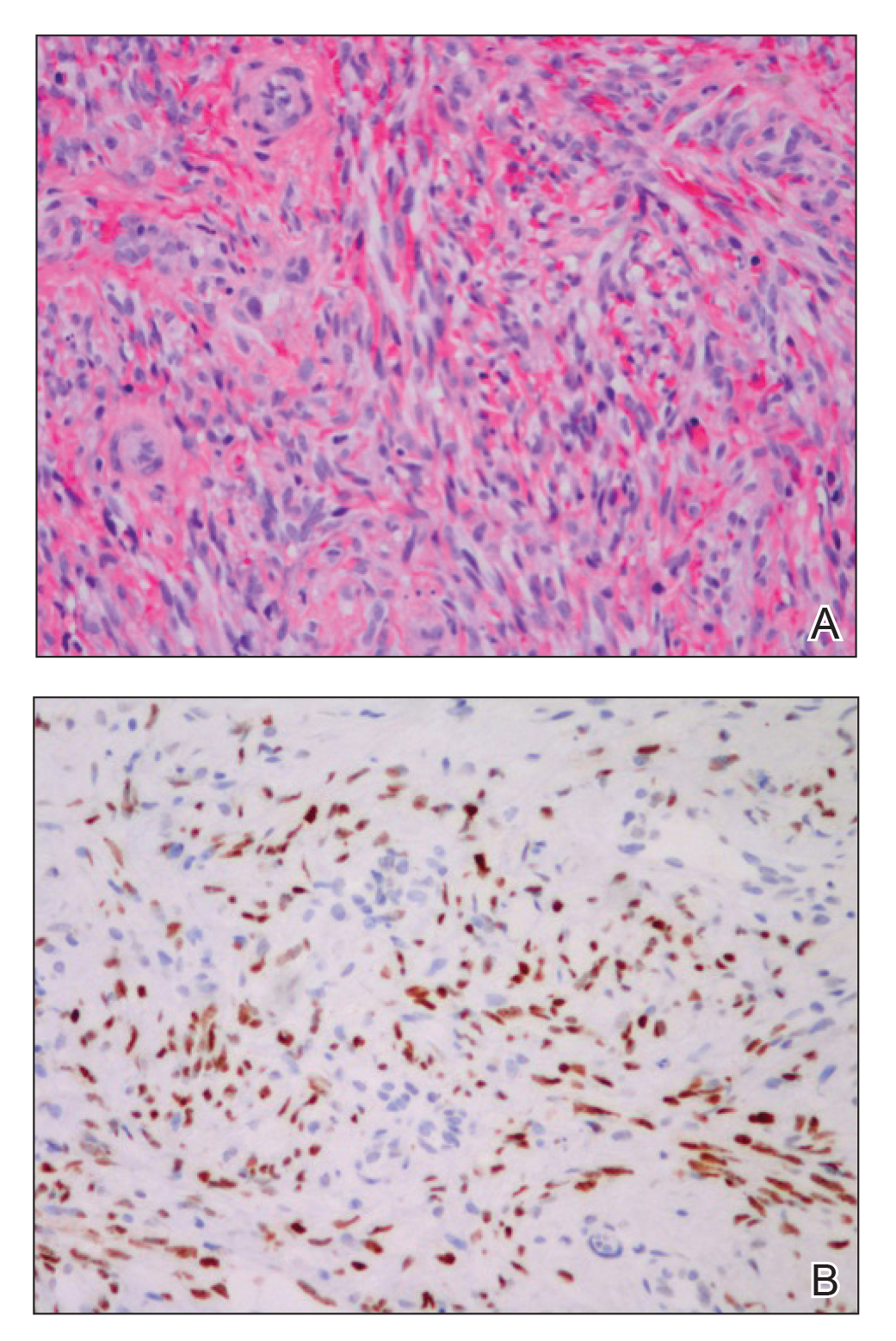

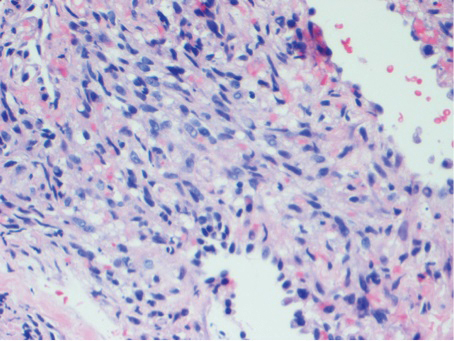

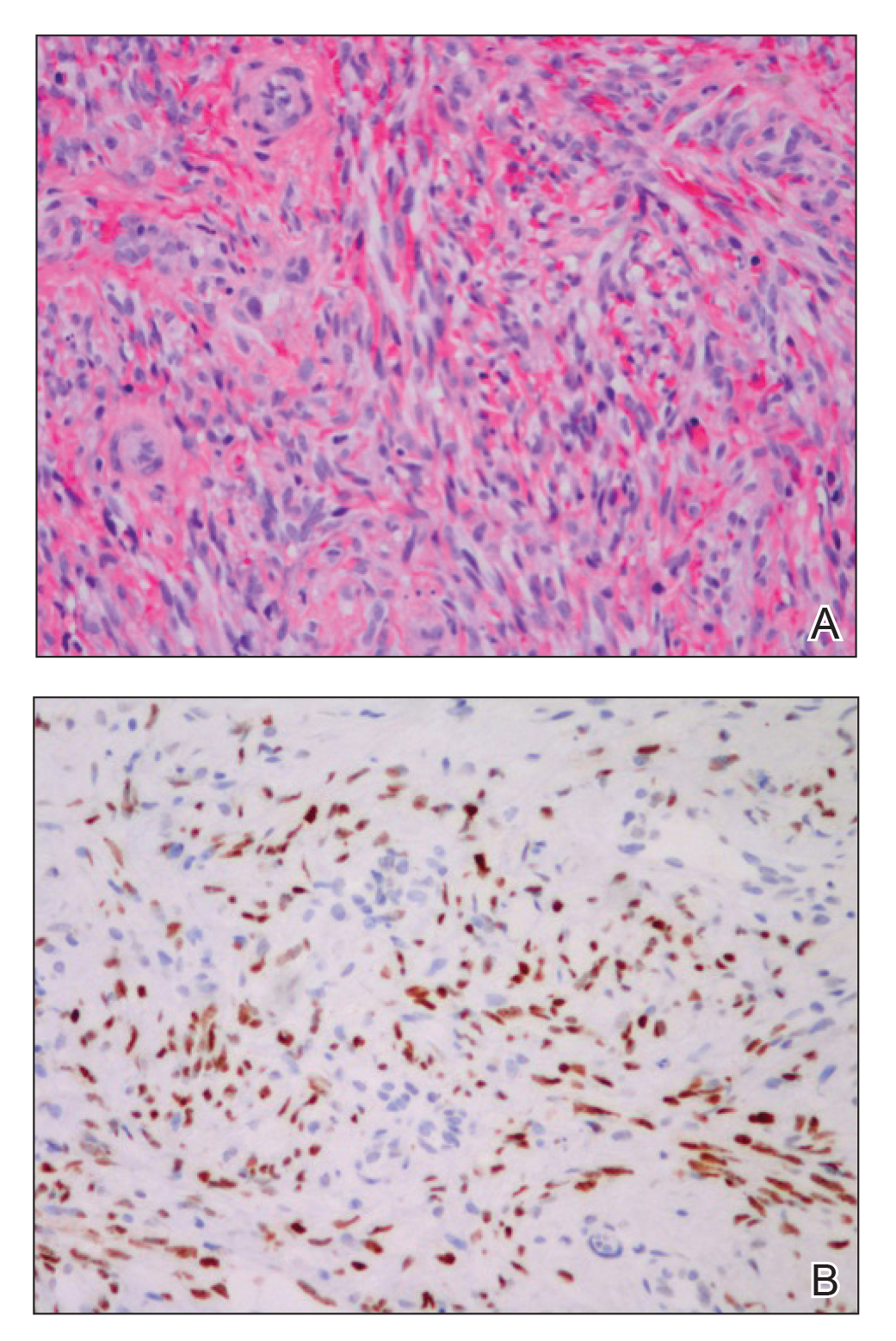

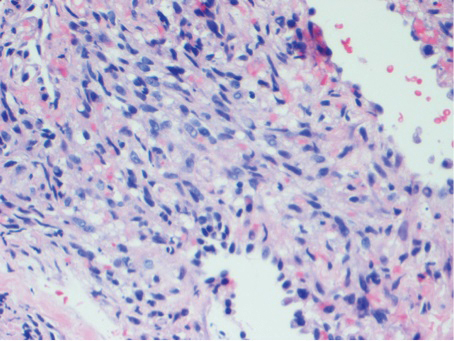

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an angioproliferative tumor of endothelial origin associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection. It is one of the most prevalent opportunistic infections associated with AIDS and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. In the general population, the incidence of KS is 1 in 100,000 worldwide.1 At the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the early 1980s, 25% of individuals with AIDS were found to have KS at the time of AIDS diagnosis. Beginning in the mid-1980s and early 1990s with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS declined to 2% to 4%,2 likely secondary to restoration of immune response.3

The clinical course of KS ranges from benign to severe, involving both cutaneous and visceral forms of disease. Cutaneous KS is the most common form of disease and typically characterizes the initial presentation. It is classically described as violaceous patches, papules, or plaques that can become confluent, forming larger tumors over time. Biopsy of cutaneous lesions may vary based on the clinical morphology. The patch stage typically is characterized by abnormal proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic vessels.4 Vascular spaces are more jagged and lined by thin endothelial cells extending into the dermis, forming the classic promontory sign.5 In the plaque stage, the vascular infiltrate becomes more diffuse, involving the dermis and subcutis, and there is proliferation of spindle cells.4 In the nodular stage, spindle-shaped tumor cells form fascicles and vascular spaces become more dilated.4,5 Advanced lesions are further associated with hyaline globules staining positive with periodic acid–Schiff.4 Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are admixed within this pathologic architecture.4,5

Visceral KS most commonly occurs in the oropharynx, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, and rarely is the initial presentation of disease. Classically, visceral KS is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening form of disease and has been found to have a much worse prognosis than cutaneous KS alone. Pulmonary involvement is the second most common site of extracutaneous KS and is known as the most severely life-threatening form of disease.1 Interestingly, since the advent of HAART, the incidence of KS with involvement of the visceral organs has declined at a more dramatic rate than cutaneous KS alone.3 Therefore, although more aggressive in nature, KS with visceral features has become increasingly rare and should be largely preventable given advances in AIDS therapy. We present a case of advanced AIDS-related KS with pulmonary involvement that is rarely seen after the advent of HAART.

A 39-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 8 years prior presented with fever, chest pain, progressive dyspnea, and hemoptysis of 5 months’ duration. At the time, he was nonadherent to medications and had poor follow-up with primary care physicians. At presentation he was tachycardic (149 beats per minute), tachypneic (26 breaths per minute), and his oxygen saturation was 80% on room air. Physical examination of the skin revealed asymptomatic violaceous penile lesions that the patient reported had been present for the last 8 months (Figure 1). Pertinent laboratory values included an HIV-1 viral load of 480,135 copies/mL (reference range, <20 copies/mL) and CD4 count of 14 cells/mm3 (reference range, 480–1700 cells/mm3). A chest radiograph was obtained and revealed bibasilar opacities compatible with a pleural and/or parenchymal process. Bronchoscopy was then performed and revealed bloody secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree.

Histologic examination of biopsies of the penile lesions revealed spindle cell proliferation with hemorrhage (Figure 2A) that stained positively for HHV-8 (Figure 2B), consistent with KS. Biopsies taken during bronchoscopy similarly revealed spindle cells with hemorrhage (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with AIDS-related KS with visceral involvement of the lung parenchyma and tracheobronchial tree. The patient was then admitted to the medical intensive care unit and intubated. Therapy with HAART and paclitaxel was initiated. After 7 days of poor response to therapy, the family opted for terminal extubation and comfort care measures. The patient died hours later.

This case report describes the classic phenomenon of AIDS-related KS in a patient with a long-standing history of immunocompromise. Even in the era of HAART, this patient developed a severe form of visceral KS with involvement of the respiratory tract and lung parenchyma.

Since the advent of HAART for the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of KS, both visceral and cutaneous forms, has dramatically declined; the risk for visceral KS declined by more than 50% but less than 30% for cutaneous KS, supporting the observation that although visceral involvement has classically been noted as the more aggressive and life-threatening form of disease, HAART appears to have a stronger effect on visceral disease than cutaneous disease.3 Although the overall impact of AIDS-defining illnesses has substantially improved over the years, those with AIDS infection remain at risk for opportunistic illness.2

It has been shown that HAART therapy leads to response in more than 50% of cases of KS.5 The administration of HAART in KS patients is associated with improved survival and an 80% reduced risk of death, even when started after KS is diagnosed.6 In a comparison of the differences in clinical manifestations of KS between patients who were already receiving HAART at the time of KS diagnosis to those who were not on HAART, it was shown that patients already on therapy presented with less aggressive clinical features. A smaller percentage of patients who were already on HAART at KS diagnosis presented with visceral disease compared to those who were not on therapy.7

It is evident that treatment of AIDS patients with HAART is not only first-line therapy for the disease but also the best preventative measure against development of KS. Management of KS also centers around the initiation of HAART if the patient is not already maintained on the proper therapy.8 In addition to HAART, treatment options for visceral KS include a variety of chemotherapeutic agents, including but not limited to the use of single-agent adriamycin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and thalidomide, or combination therapies.

Although notable advances have been made in the management of AIDS patients, this case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of the risk for KS in the context of immunocompromise. Specifically, patients with advanced AIDS who are not adherent to HAART or who have a poor response to therapy have an amplified risk for developing KS in general as well as an increased risk for developing more severe visceral KS. Maintenance of patients with HAART is shown to greatly reduce the risk for both cutaneous and visceral KS; therefore, patient adherence with therapy is of utmost importance in preventing the occurrence of this deadly disease and its complications. Appropriate follow-up should be made, ensuring that these patients at high risk are adherent to therapy and have proper access to medical care to allow for prevention and early identification of potential complications.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

- La Ferla L, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-positive patients: the state of art in the HARRT-era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2354-2365.

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al; HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654.

- Grabar S, Abraham B, Mahamat A, et al. Differential impact of combination antiretroviral therapy in preventing Kaposi’s sarcoma with and without visceral involvement. JCO. 2006;24:3408-3414.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [published online July 25, 2008]. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Tam HK, Zhang ZF, Jacobson LP, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival among HIV-infected men with Kaposi sarcoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:916-922.

- Nasti G, Martellotta F, Berretta M, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the presenting features and outcome of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2440-2446.

- Dupont C, Vasseur E, Beauchet A, et al. Long-term efficacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antriretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 2000;14:987-993.

Practice Points

- Visceral Kaposi sarcoma (KS) should be considered in patients with unexplained systemic symptoms in the setting of poorly controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- If cutaneous KS is diagnosed in an HIV patient, a detailed history and physical examination should be undertaken to evaluate for signs of systemic disease.

Crusted Demodicosis in an Immunocompetent Patient

To the Editor:

Demodicosis is an infection of humans caused by species of the genus of saprophytic mites Demodex (most commonly Demodex brevis and Demodex folliculorum) that feed on the pilosebaceous unit.1Demodex mites are believed to be a commensal species in humans; an increase in mite concentration or mite penetration of the dermis, however, can cause a shift from a commensal to a pathologic form.2 Demodicosis manifests in a variety of forms, including pityriasis folliculorum, rosacealike demodicosis, and demodicosis gravis. The likelihood of colonization increases with age; the mite rarely is observed in children but is found at a rate approaching 100% in the elderly population.3 It is hypothesized that manifestation of disease might be due to a decrease in immune function or an inherited HLA antigen that causes local immunosuppression.4

A 51-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented to our clinic with a crusting rash on the face of 9 weeks’ duration. The rash began a few days after he demolished a rotting wooden shed in his backyard. Lesions began as pustules on the left cheek, which then developed notable crusting over the next 5 to 7 days and spread to involve the forehead, nose, and right cheek (Figure 1A).

The patient had no underlying immunosuppressive disease; a human immunodeficiency virus screen, complete blood cell count, and tests of hepatic function were all unremarkable. He denied a history of frequent or recurrent sinopulmonary infections, skin infections, or infectious diarrheal illnesses. He had been seen by his primary care physician who had treated him for herpes zoster without improvement.

At our initial evaluation, biopsy was performed; specimens were sent for histopathologic analysis and culture. Findings included a dermal neutrophilic inflammation, a dense perivascular and perifollicular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with foci of neutrophilic pustules within the follicles (Figure 2), numerous intrafollicular Demodex mites (Figure 3), perifollicular vague noncaseating granuloma, and mild sebaceous hyperplasia. Grocott methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli stain were negative.

Review of clinical and pathological data yielded a final diagnosis of crusted demodicosis with a background of rosacea. The patient was ultimately treated with a single dose of oral ivermectin 15 mg with a second dose 7 days later in addition to daily application of ivermectin cream 1% to affected areas of his rash. He had notable improvement with this regimen, with complete resolution within 6 weeks (Figure 1B). The patient noted mild recurrence 14 to 21 days after discontinuing topical ivermectin.

The 2 species of Demodex that cause disease in humans each behave distinctively: D folliculorum, with a cigar-shaped body, favors superficial hair follicles; D brevis, a smaller form, burrows deeper into skin where it feeds on the pilosebaceous unit.1 Colonization occurs through direct skin-skin contact that begins as early as infancy and becomes more common with age due to development of sebaceous glands, the main source of nourishment for the mites.2

Demodicosis is classified as primary and secondary. In a prospective study of patients with clinical findings of demodicosis, Akilov et al1 discovered that the 2 forms can be differentiated by skin distribution, seasonality, mite species, and preexisting dermatoses. Primary demodicosis is categorized by sudden onset of symptoms on healthy skin, usually the face. Secondary demodicosis develops progressively in patients with preexisting skin disease, such as rosacea, and can have a broader distribution, involving the face and trunk.2 Clinical manifestations of demodicosis are broad and include pruritic papulopustular, nodulocystic, crusted, and abscesslike lesions.5

Most cases of demodicosis reported in the literature are associated with either local or systemic immunosuppression.6-8 In a case report, an otherwise immunocompetent child developed facial demodicosis after local immunosuppression from chronic use of 2 topical steroid agents.9

Demodex infestation can be diagnosed using a variety of methods, including standardized skin surface biopsy, punch biopsy, and potassium hydroxide analysis. Standardized skin surface biopsy is the preferred method to diagnose demodicosis because it is noninvasive and samples the superficial follicle where Demodex mites typically reside. Diagnosis is made by identifying 5 or more Demodex mites in a low-power field or more than 5 mites per square centimeter in standardized skin surface biopsy.2 Other potential diagnostic tools reported in the literature include dermoscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy.10,11

There is no standard therapeutic regimen for demodicosis because evidence-based trials regarding the efficacy of treatments are lacking. Oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg in a single dose is considered the preferred treatment; it can be combined with oral erythromycin, topical permethrin, or topical metronidazole.5-7,9

Our case is unique, as crusted demodicosis developed in an immunocompetent adult. Demodicosis usually causes severe eruptions in immunocompromised persons, with only 1 case report detailing a papulopustular rash in an immunocompetent adult.12,13

The pathogenesis of demodicosis remains unclear. Many mechanisms have been hypothesized to play a role in its pathogenesis, including mechanical obstruction of hair follicles, hypersensitivity reaction to Demodex mites, immune dysregulation, and a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to the skeleton of the mite.2,3 Our patient’s particular infestation could have been caused by an exuberant reaction to Demodex; however, it is likely that many factors played a role in his disease process to cause an increase in mite density and subsequent manifestations of disease.

- Akilov OE, Butov YS, Mumcuoglu KY. A clinico-pathological approach to the classification of human demodicosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:607-614.

- Karincaoglu Y, Bayram N, Aycan O, et al. The clinical importance of Demodex folliculorum presenting with nonspecific facial signs and symptoms. J Dermatol. 2004;31:618-626.

- Baima B, Sticherling M. Demodicidosis revisited. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:3-6.

- Noy ML, Hughes S, Bunker CB. Another face of demodicosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:958-959.

- Chen W, Plewig G. Human demodicosis: revisit and a proposed classification. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1219-1225.

- Morrás PG, Santos SP, Imedio IL, et al. Rosacea-like demodicidosis in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:28-30.

- Damian D, Rogers M. Demodex infestation in a child with leukaemia: treatment with ivermectin and permethrin. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:724-726.

- Clyti E, Nacher M, Sainte-Marie D, et al. Ivermectin treatment of three cases of demodecidosis during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1066-1068.

- Guerrero-González GA, Herz-Ruelas ME, Gómez-Flores M, et al. Crusted demodicosis in an immunocompetent pediatric patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:458046.

- Friedman P, Sabban EC, Cabo H. Usefulness of dermoscopy in the diagnosis and monitoring treatment of demodicidosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:35-38.

- Harmelin Y, Delaunay P, Erfan N, et al. Interest of confocal laser scanning microscopy for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of demodicosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:255-257.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Kaur T, Jindal N, Bansal R, et al. Facial demodicidosis: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:72-73.

To the Editor:

Demodicosis is an infection of humans caused by species of the genus of saprophytic mites Demodex (most commonly Demodex brevis and Demodex folliculorum) that feed on the pilosebaceous unit.1Demodex mites are believed to be a commensal species in humans; an increase in mite concentration or mite penetration of the dermis, however, can cause a shift from a commensal to a pathologic form.2 Demodicosis manifests in a variety of forms, including pityriasis folliculorum, rosacealike demodicosis, and demodicosis gravis. The likelihood of colonization increases with age; the mite rarely is observed in children but is found at a rate approaching 100% in the elderly population.3 It is hypothesized that manifestation of disease might be due to a decrease in immune function or an inherited HLA antigen that causes local immunosuppression.4

A 51-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented to our clinic with a crusting rash on the face of 9 weeks’ duration. The rash began a few days after he demolished a rotting wooden shed in his backyard. Lesions began as pustules on the left cheek, which then developed notable crusting over the next 5 to 7 days and spread to involve the forehead, nose, and right cheek (Figure 1A).

The patient had no underlying immunosuppressive disease; a human immunodeficiency virus screen, complete blood cell count, and tests of hepatic function were all unremarkable. He denied a history of frequent or recurrent sinopulmonary infections, skin infections, or infectious diarrheal illnesses. He had been seen by his primary care physician who had treated him for herpes zoster without improvement.

At our initial evaluation, biopsy was performed; specimens were sent for histopathologic analysis and culture. Findings included a dermal neutrophilic inflammation, a dense perivascular and perifollicular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with foci of neutrophilic pustules within the follicles (Figure 2), numerous intrafollicular Demodex mites (Figure 3), perifollicular vague noncaseating granuloma, and mild sebaceous hyperplasia. Grocott methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli stain were negative.

Review of clinical and pathological data yielded a final diagnosis of crusted demodicosis with a background of rosacea. The patient was ultimately treated with a single dose of oral ivermectin 15 mg with a second dose 7 days later in addition to daily application of ivermectin cream 1% to affected areas of his rash. He had notable improvement with this regimen, with complete resolution within 6 weeks (Figure 1B). The patient noted mild recurrence 14 to 21 days after discontinuing topical ivermectin.

The 2 species of Demodex that cause disease in humans each behave distinctively: D folliculorum, with a cigar-shaped body, favors superficial hair follicles; D brevis, a smaller form, burrows deeper into skin where it feeds on the pilosebaceous unit.1 Colonization occurs through direct skin-skin contact that begins as early as infancy and becomes more common with age due to development of sebaceous glands, the main source of nourishment for the mites.2

Demodicosis is classified as primary and secondary. In a prospective study of patients with clinical findings of demodicosis, Akilov et al1 discovered that the 2 forms can be differentiated by skin distribution, seasonality, mite species, and preexisting dermatoses. Primary demodicosis is categorized by sudden onset of symptoms on healthy skin, usually the face. Secondary demodicosis develops progressively in patients with preexisting skin disease, such as rosacea, and can have a broader distribution, involving the face and trunk.2 Clinical manifestations of demodicosis are broad and include pruritic papulopustular, nodulocystic, crusted, and abscesslike lesions.5

Most cases of demodicosis reported in the literature are associated with either local or systemic immunosuppression.6-8 In a case report, an otherwise immunocompetent child developed facial demodicosis after local immunosuppression from chronic use of 2 topical steroid agents.9

Demodex infestation can be diagnosed using a variety of methods, including standardized skin surface biopsy, punch biopsy, and potassium hydroxide analysis. Standardized skin surface biopsy is the preferred method to diagnose demodicosis because it is noninvasive and samples the superficial follicle where Demodex mites typically reside. Diagnosis is made by identifying 5 or more Demodex mites in a low-power field or more than 5 mites per square centimeter in standardized skin surface biopsy.2 Other potential diagnostic tools reported in the literature include dermoscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy.10,11

There is no standard therapeutic regimen for demodicosis because evidence-based trials regarding the efficacy of treatments are lacking. Oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg in a single dose is considered the preferred treatment; it can be combined with oral erythromycin, topical permethrin, or topical metronidazole.5-7,9

Our case is unique, as crusted demodicosis developed in an immunocompetent adult. Demodicosis usually causes severe eruptions in immunocompromised persons, with only 1 case report detailing a papulopustular rash in an immunocompetent adult.12,13

The pathogenesis of demodicosis remains unclear. Many mechanisms have been hypothesized to play a role in its pathogenesis, including mechanical obstruction of hair follicles, hypersensitivity reaction to Demodex mites, immune dysregulation, and a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to the skeleton of the mite.2,3 Our patient’s particular infestation could have been caused by an exuberant reaction to Demodex; however, it is likely that many factors played a role in his disease process to cause an increase in mite density and subsequent manifestations of disease.

To the Editor:

Demodicosis is an infection of humans caused by species of the genus of saprophytic mites Demodex (most commonly Demodex brevis and Demodex folliculorum) that feed on the pilosebaceous unit.1Demodex mites are believed to be a commensal species in humans; an increase in mite concentration or mite penetration of the dermis, however, can cause a shift from a commensal to a pathologic form.2 Demodicosis manifests in a variety of forms, including pityriasis folliculorum, rosacealike demodicosis, and demodicosis gravis. The likelihood of colonization increases with age; the mite rarely is observed in children but is found at a rate approaching 100% in the elderly population.3 It is hypothesized that manifestation of disease might be due to a decrease in immune function or an inherited HLA antigen that causes local immunosuppression.4

A 51-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented to our clinic with a crusting rash on the face of 9 weeks’ duration. The rash began a few days after he demolished a rotting wooden shed in his backyard. Lesions began as pustules on the left cheek, which then developed notable crusting over the next 5 to 7 days and spread to involve the forehead, nose, and right cheek (Figure 1A).

The patient had no underlying immunosuppressive disease; a human immunodeficiency virus screen, complete blood cell count, and tests of hepatic function were all unremarkable. He denied a history of frequent or recurrent sinopulmonary infections, skin infections, or infectious diarrheal illnesses. He had been seen by his primary care physician who had treated him for herpes zoster without improvement.

At our initial evaluation, biopsy was performed; specimens were sent for histopathologic analysis and culture. Findings included a dermal neutrophilic inflammation, a dense perivascular and perifollicular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with foci of neutrophilic pustules within the follicles (Figure 2), numerous intrafollicular Demodex mites (Figure 3), perifollicular vague noncaseating granuloma, and mild sebaceous hyperplasia. Grocott methenamine-silver stain and acid-fast bacilli stain were negative.

Review of clinical and pathological data yielded a final diagnosis of crusted demodicosis with a background of rosacea. The patient was ultimately treated with a single dose of oral ivermectin 15 mg with a second dose 7 days later in addition to daily application of ivermectin cream 1% to affected areas of his rash. He had notable improvement with this regimen, with complete resolution within 6 weeks (Figure 1B). The patient noted mild recurrence 14 to 21 days after discontinuing topical ivermectin.

The 2 species of Demodex that cause disease in humans each behave distinctively: D folliculorum, with a cigar-shaped body, favors superficial hair follicles; D brevis, a smaller form, burrows deeper into skin where it feeds on the pilosebaceous unit.1 Colonization occurs through direct skin-skin contact that begins as early as infancy and becomes more common with age due to development of sebaceous glands, the main source of nourishment for the mites.2

Demodicosis is classified as primary and secondary. In a prospective study of patients with clinical findings of demodicosis, Akilov et al1 discovered that the 2 forms can be differentiated by skin distribution, seasonality, mite species, and preexisting dermatoses. Primary demodicosis is categorized by sudden onset of symptoms on healthy skin, usually the face. Secondary demodicosis develops progressively in patients with preexisting skin disease, such as rosacea, and can have a broader distribution, involving the face and trunk.2 Clinical manifestations of demodicosis are broad and include pruritic papulopustular, nodulocystic, crusted, and abscesslike lesions.5

Most cases of demodicosis reported in the literature are associated with either local or systemic immunosuppression.6-8 In a case report, an otherwise immunocompetent child developed facial demodicosis after local immunosuppression from chronic use of 2 topical steroid agents.9