User login

California bans “Pay for Delay,” promotes black maternal health, PrEP access

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

Congenital syphilis continues to rise at an alarming rate

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

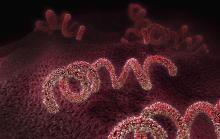

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

HCV+ kidney transplants: Similar outcomes to HCV- regardless of recipient serostatus

Kidneys from donors with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection function well despite adverse quality assessment and are a valuable resource for transplantation candidates independent of HCV status, according to the findings of a large U.S. registry study.

A total of 260 HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted in the first quarter of 2019, with 105 additional viremic kidneys being discarded, according to a report in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology by Vishnu S. Potluri, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Donor HCV viremia was defined as an HCV nucleic acid test–positive result reported to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Donors who were HCV negative in this test were labeled as HCV nonviremic. Kidney transplantation recipients were defined as either HCV seropositive or seronegative based on HCV antibody testing.

During the first quarter of 2019, 74% of HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted into seronegative recipients, which is a major change from how HCV-viremic kidneys were allocated a few years ago, according to the researchers. The results of small trials showing the benefits of such transplantations and the success of direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) on clearing HCV infections were indicated as likely responsible for the change.

HCV-viremic kidneys had similar function, compared with HCV-nonviremic kidneys, when matched on the donor elements included in the Kidney Profile Donor Index (KDPI), excluding HCV, they added. In addition, the 12-month estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was similar between the seropositive and seronegative recipients, respectively 65.4 and 71.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (P = .05), which suggests that recipient HCV serostatus does not negatively affect 1-year graft function using HCV-viremic kidneys in the era of DAA treatments, according to the authors.

Also, among HCV-seropositive recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys, seven (3.4%) died by 1 year post transplantation, while none of the HCV-seronegative recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys experienced graft failure or death.

“These striking results provide important additional evidence that the KDPI, with its current negative weighting for HCV status, does not accurately assess the quality of kidneys from HCV-viremic donors,” the authors wrote.

“HCV-viremic kidneys are a valuable resource for transplantation. Disincentives for accepting these organs should be addressed by the transplantation community,” Dr. Potluri and colleagues concluded.

This work was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The various authors reported grant funding and advisory board participation with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Potluri VS et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1939-51.

Kidneys from donors with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection function well despite adverse quality assessment and are a valuable resource for transplantation candidates independent of HCV status, according to the findings of a large U.S. registry study.

A total of 260 HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted in the first quarter of 2019, with 105 additional viremic kidneys being discarded, according to a report in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology by Vishnu S. Potluri, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Donor HCV viremia was defined as an HCV nucleic acid test–positive result reported to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Donors who were HCV negative in this test were labeled as HCV nonviremic. Kidney transplantation recipients were defined as either HCV seropositive or seronegative based on HCV antibody testing.

During the first quarter of 2019, 74% of HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted into seronegative recipients, which is a major change from how HCV-viremic kidneys were allocated a few years ago, according to the researchers. The results of small trials showing the benefits of such transplantations and the success of direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) on clearing HCV infections were indicated as likely responsible for the change.

HCV-viremic kidneys had similar function, compared with HCV-nonviremic kidneys, when matched on the donor elements included in the Kidney Profile Donor Index (KDPI), excluding HCV, they added. In addition, the 12-month estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was similar between the seropositive and seronegative recipients, respectively 65.4 and 71.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (P = .05), which suggests that recipient HCV serostatus does not negatively affect 1-year graft function using HCV-viremic kidneys in the era of DAA treatments, according to the authors.

Also, among HCV-seropositive recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys, seven (3.4%) died by 1 year post transplantation, while none of the HCV-seronegative recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys experienced graft failure or death.

“These striking results provide important additional evidence that the KDPI, with its current negative weighting for HCV status, does not accurately assess the quality of kidneys from HCV-viremic donors,” the authors wrote.

“HCV-viremic kidneys are a valuable resource for transplantation. Disincentives for accepting these organs should be addressed by the transplantation community,” Dr. Potluri and colleagues concluded.

This work was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The various authors reported grant funding and advisory board participation with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Potluri VS et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1939-51.

Kidneys from donors with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection function well despite adverse quality assessment and are a valuable resource for transplantation candidates independent of HCV status, according to the findings of a large U.S. registry study.

A total of 260 HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted in the first quarter of 2019, with 105 additional viremic kidneys being discarded, according to a report in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology by Vishnu S. Potluri, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Donor HCV viremia was defined as an HCV nucleic acid test–positive result reported to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Donors who were HCV negative in this test were labeled as HCV nonviremic. Kidney transplantation recipients were defined as either HCV seropositive or seronegative based on HCV antibody testing.

During the first quarter of 2019, 74% of HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted into seronegative recipients, which is a major change from how HCV-viremic kidneys were allocated a few years ago, according to the researchers. The results of small trials showing the benefits of such transplantations and the success of direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) on clearing HCV infections were indicated as likely responsible for the change.

HCV-viremic kidneys had similar function, compared with HCV-nonviremic kidneys, when matched on the donor elements included in the Kidney Profile Donor Index (KDPI), excluding HCV, they added. In addition, the 12-month estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was similar between the seropositive and seronegative recipients, respectively 65.4 and 71.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (P = .05), which suggests that recipient HCV serostatus does not negatively affect 1-year graft function using HCV-viremic kidneys in the era of DAA treatments, according to the authors.

Also, among HCV-seropositive recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys, seven (3.4%) died by 1 year post transplantation, while none of the HCV-seronegative recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys experienced graft failure or death.

“These striking results provide important additional evidence that the KDPI, with its current negative weighting for HCV status, does not accurately assess the quality of kidneys from HCV-viremic donors,” the authors wrote.

“HCV-viremic kidneys are a valuable resource for transplantation. Disincentives for accepting these organs should be addressed by the transplantation community,” Dr. Potluri and colleagues concluded.

This work was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The various authors reported grant funding and advisory board participation with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Potluri VS et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1939-51.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEPHROLOGY

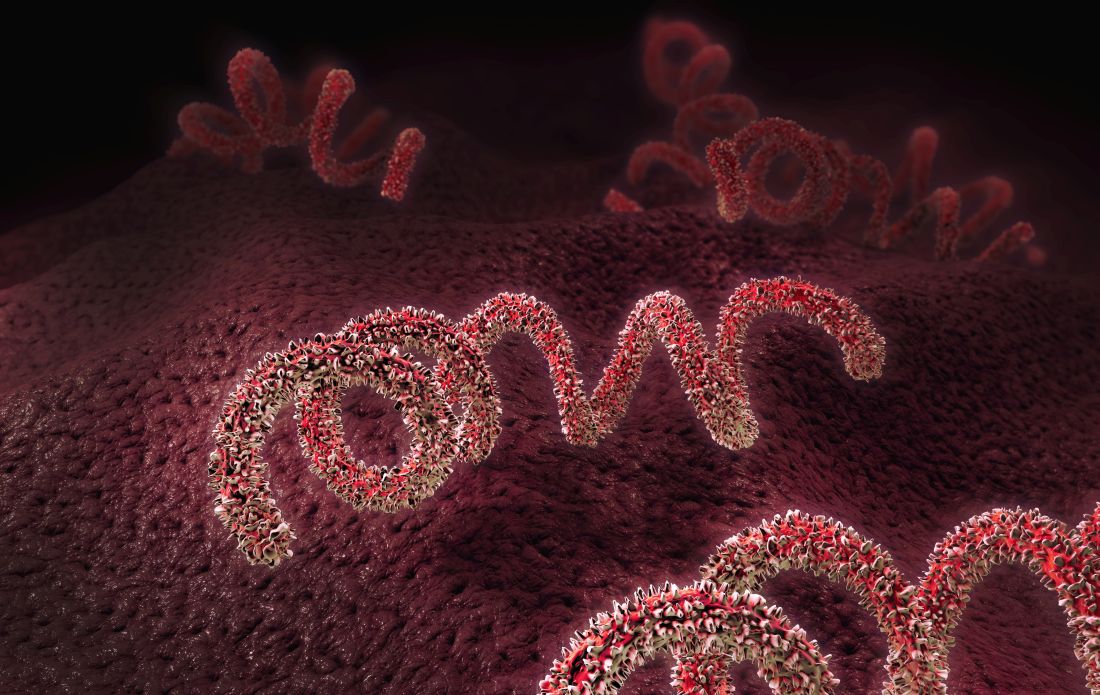

Too few pregnant women receive both influenza and Tdap vaccines

according to a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC recommends that all pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation. The flu vaccine is recommended for all women at any point in pregnancy if the pregnancy falls within flu season. Women do not need a second flu shot if they received the vaccine before pregnancy in the same influenza season. Both vaccines provide protection to infants after birth.

“Clinicians caring for women who are pregnant have a huge role in helping women understand risks and benefits and the value of vaccines,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, Atlanta, said in a telebriefing about the new report. “A lot of women are worried about taking any extra medicine or getting shots during pregnancy, and clinicians can let them know about the large data available showing the safety of the vaccine as well as the effectiveness. We also think it’s important to let people know about the risk of not vaccinating.”

Pregnant women are at higher risk for influenza complications and represent a disproportionate number of flu-related hospitalizations. From the 2010-2011 to 2017-2018 influenza seasons, 24%-34% of influenza hospitalizations each season were pregnant women aged 15-44, yet only 9% of women in this age group are pregnant at any point each year, according to the report.

Similarly, infants under 6 months have the greatest risk of hospitalization from influenza, and half of pertussis hospitalizations and 69% of pertussis deaths occur in infants under 2 months old. But a fetus receives protective maternal antibodies from flu and pertussis vaccines about 2 weeks after the mother is vaccinated.

Influenza hospitalization is 40% lower among pregnant women vaccinated against flu and 72% lower in infants under 6 months who received maternal influenza antibodies during gestation. Similarly, Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy reduces pertussis infection risk by 78% and pertussis hospitalization by 91% in infants under 2 months.

“Infant protection can motivate pregnant women to receive recommended vaccines, and intention to vaccinate is higher among women who perceive more serious consequences of influenza or pertussis disease for their own or their infant’s health,” Megan C. Lindley, MPH, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division, and colleagues wrote in the MMWR report.

In March-April 2019, Ms. Lindley and associates conducted an Internet survey about flu and Tdap immunizations among women aged 18-49 who had been pregnant at any point since August 1, 2018. A total of 2,626 women completed the survey of 2,762 invitations (95% response rate).

Among 817 women who knew their Tdap status during pregnancy, 55% received the Tdap vaccine. Among 2,097 women who reported a pregnancy between October 2018 and January 2019, 54% received the flu vaccine before or during pregnancy.

But many women received one vaccine without the other: 65% of women surveyed had not received both vaccines during pregnancy. Higher immunization rates occurred among women whose clinicians recommended the vaccines: 66% received a flu shot and 71% received Tdap.

“We’re learning a lot about improved communication between clinicians and patients. One thing we suggest is to begin the conversations early.” Dr Schuchat said. “If you begin talking early in the pregnancy about the things you’ll be looking forward to and provide information, by the time it is flu season or it is that third trimester, they’re prepared to make a good choice.”

Most women surveyed (75%) said their providers did offer a flu or Tdap vaccine in the office or a referral for one. Yet more than 30% of these women did not get the recommended vaccine.

The most common reason for not getting the Tdap during pregnancy, cited by 38% of women who didn’t receive it, was not knowing about the recommendation. Those who did not receive flu vaccination, however, cited concerns about effectiveness (18%) or safety for the baby (16%). A similar proportion of women cited safety concerns for not getting the Tdap (17%).

Sharing information early and engaging respectfully with patients are key to successful provider recommendations, Dr Schuchat said.

“It’s really important for clinicians to begin by listening to women, asking, ‘Can I answer your questions? What are the concerns that you have?’ ” she said. “We find that, when a clinician validates a patient’s concerns and really shows that they’re listening, they can build trust and respect.”

Providers’ sharing their personal experience can help as well, Dr Schuchat added. Clinicians can let patients know if they themselves, or their partner, received the vaccines during pregnancy.

Rates for turning down vaccines were higher for black women: 47% received the flu vaccine after a recommendation, compared with 69% of white women. Among those receiving a Tdap recommendation, 53% of black women accepted it, compared with 77% of white women and 66% of Latina women. The authors noted a past study showing black adults had a higher distrust of flu vaccination, their doctor, and CDC information than white adults.

“Differential effects of provider vaccination offers or referrals might also be explained by less patient-centered provider communication with black patients,” Ms. Lindley and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Lindley MC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Oct 8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6840e1.

according to a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC recommends that all pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation. The flu vaccine is recommended for all women at any point in pregnancy if the pregnancy falls within flu season. Women do not need a second flu shot if they received the vaccine before pregnancy in the same influenza season. Both vaccines provide protection to infants after birth.

“Clinicians caring for women who are pregnant have a huge role in helping women understand risks and benefits and the value of vaccines,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, Atlanta, said in a telebriefing about the new report. “A lot of women are worried about taking any extra medicine or getting shots during pregnancy, and clinicians can let them know about the large data available showing the safety of the vaccine as well as the effectiveness. We also think it’s important to let people know about the risk of not vaccinating.”

Pregnant women are at higher risk for influenza complications and represent a disproportionate number of flu-related hospitalizations. From the 2010-2011 to 2017-2018 influenza seasons, 24%-34% of influenza hospitalizations each season were pregnant women aged 15-44, yet only 9% of women in this age group are pregnant at any point each year, according to the report.

Similarly, infants under 6 months have the greatest risk of hospitalization from influenza, and half of pertussis hospitalizations and 69% of pertussis deaths occur in infants under 2 months old. But a fetus receives protective maternal antibodies from flu and pertussis vaccines about 2 weeks after the mother is vaccinated.

Influenza hospitalization is 40% lower among pregnant women vaccinated against flu and 72% lower in infants under 6 months who received maternal influenza antibodies during gestation. Similarly, Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy reduces pertussis infection risk by 78% and pertussis hospitalization by 91% in infants under 2 months.

“Infant protection can motivate pregnant women to receive recommended vaccines, and intention to vaccinate is higher among women who perceive more serious consequences of influenza or pertussis disease for their own or their infant’s health,” Megan C. Lindley, MPH, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division, and colleagues wrote in the MMWR report.

In March-April 2019, Ms. Lindley and associates conducted an Internet survey about flu and Tdap immunizations among women aged 18-49 who had been pregnant at any point since August 1, 2018. A total of 2,626 women completed the survey of 2,762 invitations (95% response rate).

Among 817 women who knew their Tdap status during pregnancy, 55% received the Tdap vaccine. Among 2,097 women who reported a pregnancy between October 2018 and January 2019, 54% received the flu vaccine before or during pregnancy.

But many women received one vaccine without the other: 65% of women surveyed had not received both vaccines during pregnancy. Higher immunization rates occurred among women whose clinicians recommended the vaccines: 66% received a flu shot and 71% received Tdap.

“We’re learning a lot about improved communication between clinicians and patients. One thing we suggest is to begin the conversations early.” Dr Schuchat said. “If you begin talking early in the pregnancy about the things you’ll be looking forward to and provide information, by the time it is flu season or it is that third trimester, they’re prepared to make a good choice.”

Most women surveyed (75%) said their providers did offer a flu or Tdap vaccine in the office or a referral for one. Yet more than 30% of these women did not get the recommended vaccine.

The most common reason for not getting the Tdap during pregnancy, cited by 38% of women who didn’t receive it, was not knowing about the recommendation. Those who did not receive flu vaccination, however, cited concerns about effectiveness (18%) or safety for the baby (16%). A similar proportion of women cited safety concerns for not getting the Tdap (17%).

Sharing information early and engaging respectfully with patients are key to successful provider recommendations, Dr Schuchat said.

“It’s really important for clinicians to begin by listening to women, asking, ‘Can I answer your questions? What are the concerns that you have?’ ” she said. “We find that, when a clinician validates a patient’s concerns and really shows that they’re listening, they can build trust and respect.”

Providers’ sharing their personal experience can help as well, Dr Schuchat added. Clinicians can let patients know if they themselves, or their partner, received the vaccines during pregnancy.

Rates for turning down vaccines were higher for black women: 47% received the flu vaccine after a recommendation, compared with 69% of white women. Among those receiving a Tdap recommendation, 53% of black women accepted it, compared with 77% of white women and 66% of Latina women. The authors noted a past study showing black adults had a higher distrust of flu vaccination, their doctor, and CDC information than white adults.

“Differential effects of provider vaccination offers or referrals might also be explained by less patient-centered provider communication with black patients,” Ms. Lindley and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Lindley MC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Oct 8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6840e1.

according to a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC recommends that all pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation. The flu vaccine is recommended for all women at any point in pregnancy if the pregnancy falls within flu season. Women do not need a second flu shot if they received the vaccine before pregnancy in the same influenza season. Both vaccines provide protection to infants after birth.

“Clinicians caring for women who are pregnant have a huge role in helping women understand risks and benefits and the value of vaccines,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, Atlanta, said in a telebriefing about the new report. “A lot of women are worried about taking any extra medicine or getting shots during pregnancy, and clinicians can let them know about the large data available showing the safety of the vaccine as well as the effectiveness. We also think it’s important to let people know about the risk of not vaccinating.”

Pregnant women are at higher risk for influenza complications and represent a disproportionate number of flu-related hospitalizations. From the 2010-2011 to 2017-2018 influenza seasons, 24%-34% of influenza hospitalizations each season were pregnant women aged 15-44, yet only 9% of women in this age group are pregnant at any point each year, according to the report.

Similarly, infants under 6 months have the greatest risk of hospitalization from influenza, and half of pertussis hospitalizations and 69% of pertussis deaths occur in infants under 2 months old. But a fetus receives protective maternal antibodies from flu and pertussis vaccines about 2 weeks after the mother is vaccinated.

Influenza hospitalization is 40% lower among pregnant women vaccinated against flu and 72% lower in infants under 6 months who received maternal influenza antibodies during gestation. Similarly, Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy reduces pertussis infection risk by 78% and pertussis hospitalization by 91% in infants under 2 months.

“Infant protection can motivate pregnant women to receive recommended vaccines, and intention to vaccinate is higher among women who perceive more serious consequences of influenza or pertussis disease for their own or their infant’s health,” Megan C. Lindley, MPH, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division, and colleagues wrote in the MMWR report.

In March-April 2019, Ms. Lindley and associates conducted an Internet survey about flu and Tdap immunizations among women aged 18-49 who had been pregnant at any point since August 1, 2018. A total of 2,626 women completed the survey of 2,762 invitations (95% response rate).

Among 817 women who knew their Tdap status during pregnancy, 55% received the Tdap vaccine. Among 2,097 women who reported a pregnancy between October 2018 and January 2019, 54% received the flu vaccine before or during pregnancy.

But many women received one vaccine without the other: 65% of women surveyed had not received both vaccines during pregnancy. Higher immunization rates occurred among women whose clinicians recommended the vaccines: 66% received a flu shot and 71% received Tdap.

“We’re learning a lot about improved communication between clinicians and patients. One thing we suggest is to begin the conversations early.” Dr Schuchat said. “If you begin talking early in the pregnancy about the things you’ll be looking forward to and provide information, by the time it is flu season or it is that third trimester, they’re prepared to make a good choice.”

Most women surveyed (75%) said their providers did offer a flu or Tdap vaccine in the office or a referral for one. Yet more than 30% of these women did not get the recommended vaccine.

The most common reason for not getting the Tdap during pregnancy, cited by 38% of women who didn’t receive it, was not knowing about the recommendation. Those who did not receive flu vaccination, however, cited concerns about effectiveness (18%) or safety for the baby (16%). A similar proportion of women cited safety concerns for not getting the Tdap (17%).

Sharing information early and engaging respectfully with patients are key to successful provider recommendations, Dr Schuchat said.

“It’s really important for clinicians to begin by listening to women, asking, ‘Can I answer your questions? What are the concerns that you have?’ ” she said. “We find that, when a clinician validates a patient’s concerns and really shows that they’re listening, they can build trust and respect.”

Providers’ sharing their personal experience can help as well, Dr Schuchat added. Clinicians can let patients know if they themselves, or their partner, received the vaccines during pregnancy.

Rates for turning down vaccines were higher for black women: 47% received the flu vaccine after a recommendation, compared with 69% of white women. Among those receiving a Tdap recommendation, 53% of black women accepted it, compared with 77% of white women and 66% of Latina women. The authors noted a past study showing black adults had a higher distrust of flu vaccination, their doctor, and CDC information than white adults.

“Differential effects of provider vaccination offers or referrals might also be explained by less patient-centered provider communication with black patients,” Ms. Lindley and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Lindley MC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Oct 8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6840e1.

FROM MMWR TELEBRIEFING

Larval Tick Infestation Causing an Eruption of Pruritic Papules and Pustules

Case Reports

Patient 1

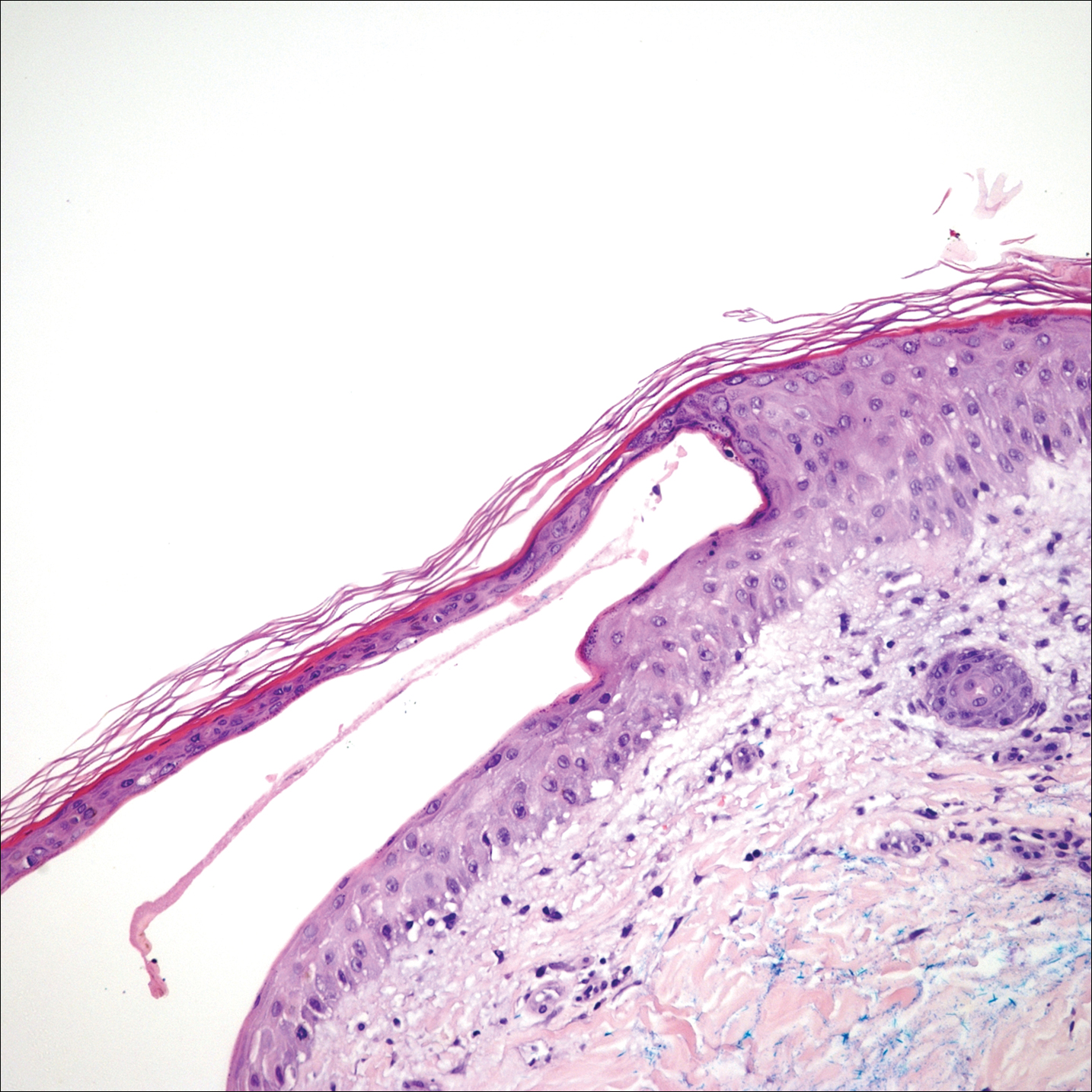

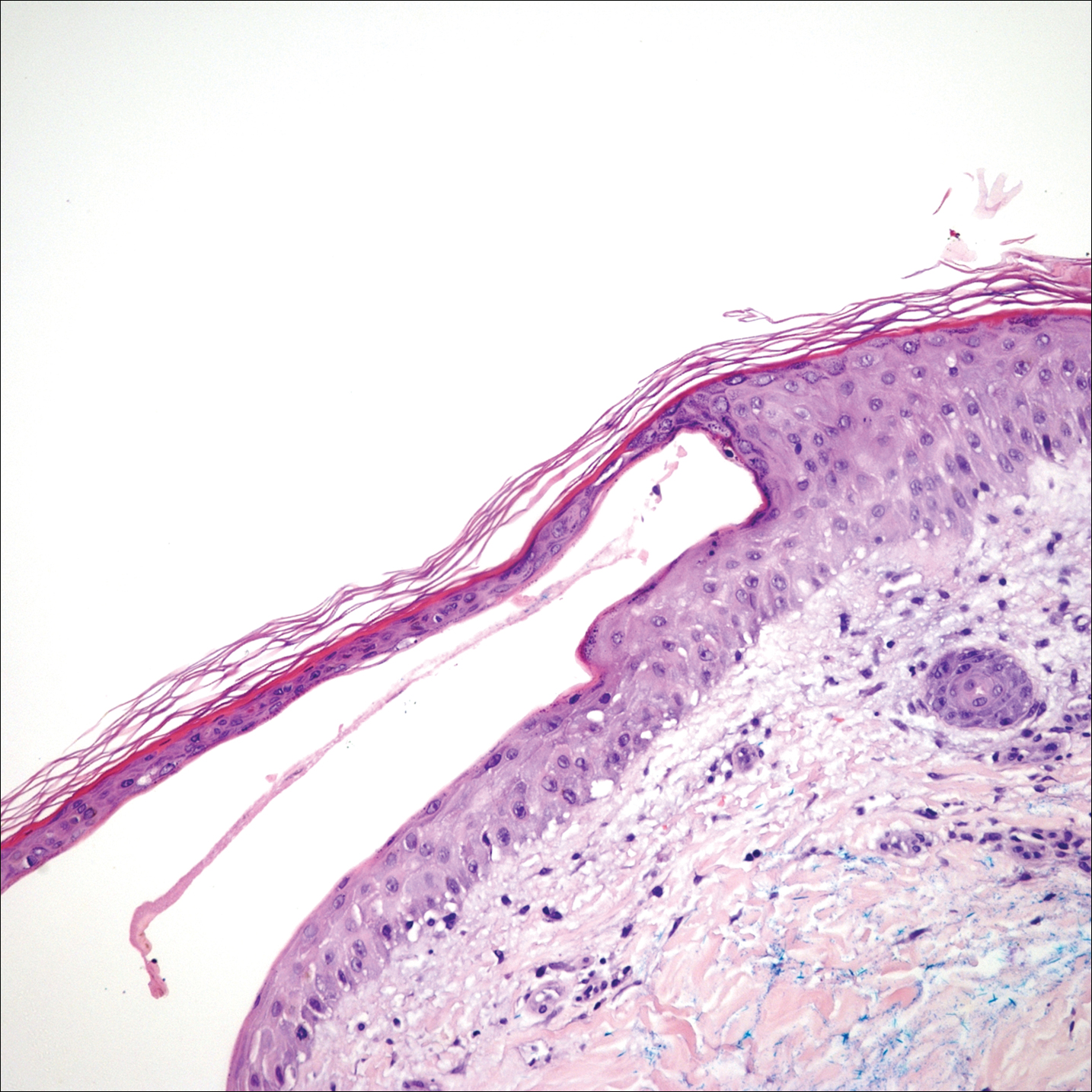

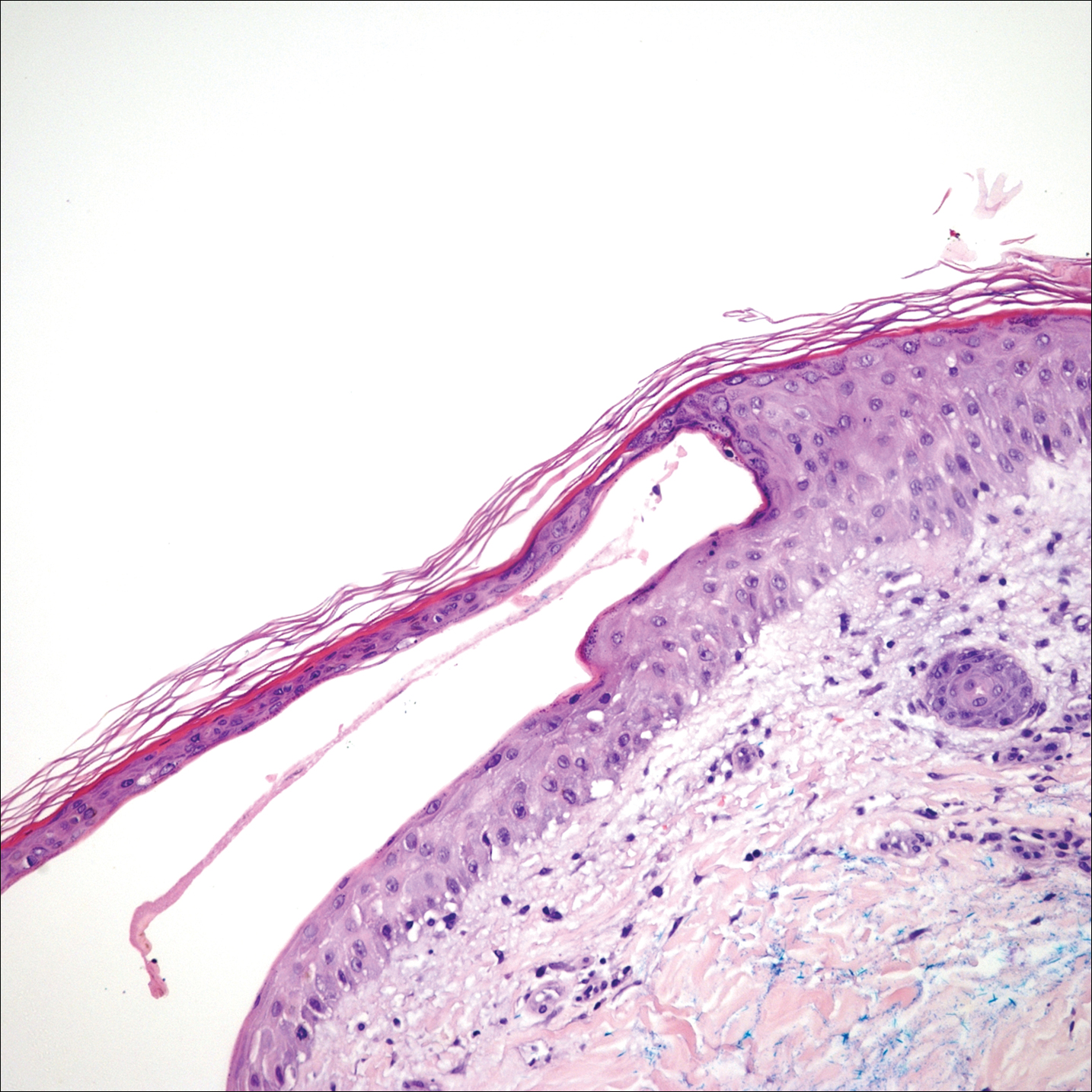

A 65-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic in July with a pruritic rash of 2 days’ duration that started on the back and spread diffusely. The patient gardened regularly. Physical examination showed inflammatory papules and pustules on the back (Figure 1), as well as the groin, breasts, and ears. There was a punctate black dot in the center of some papules, and dermoscopy revealed ticks (Figure 2). Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage lone star ticks (Figure 3). The patient was prescribed topical steroids for pruritus as well as oral doxycycline for prophylaxis against tick-borne illnesses.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man presented to the same clinic in July with pruritic lesions on the back, legs, ankles, and scrotum of 3 days’ duration that first appeared 24 hours after performing yardwork. Physical examination revealed diffusely distributed papules, pustules, and vesicles on the back (Figure 4). Some papules featured a punctate black dot in the center (similar to patient 1), and dermoscopy again revealed ticks. Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage ticks. The patient was treated with topical steroids and oral antihistamines for pruritus as well as prophylactic oral doxycycline.

Comment

Ticks are well-known human parasites, representing the second most common vector of human infectious disease.1 Ticks have 3 motile stages: larva (or “seed”), nymph, and adult. They can bite humans during all stages. Larval ticks, distinguished by having 6 legs rather than 8 legs in nymphs and adults, can attack in droves and cause an infestation that presents as diffuse, pruritic, erythematous papules and pustules.2-4 The first report of larval tick infestation in humans may have been in 1728 by William Byrd who described finding ticks on the skin that were too small to see without a microscope.5

Identification

The ticks in both of our cases were lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). The larval stage of A americanum is a proven cause of cutaneous reaction.6,7 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the terms tick, seed tick, or tick bite in combination with rash, eruption, infestation, papule, pustule, or pruritic revealed 6 reported cases of larval tick infestation in the literature (including our case); 5 were caused by A americanum and 1 by Ixodes dammini (now known as Ixodes scapularis); all occurred in July or August.3,7-10 This time frame is consistent with the general tick life cycle across species: Adults feed from April to June, then lay eggs that hatch into larval ticks within 4 to 6 weeks. After hatching, larval ticks climb grass and weeds awaiting a passing host.4

Diagnosis

Larval tick infestation remains a frequently misdiagnosed etiology of diffuse pruritic papules and pustules, especially in urban settings where physicians are less likely to be familiar with this type of manifestation.3,9-11 Larval ticks are submillimeter in size and difficult to appreciate with the naked eye, contributing to misdiagnosis. A punctate black dot may sometimes be seen in papules; however, dermoscopy is critical for accurate diagnosis, as hemorrhagic crust is a frequent misdiagnosis.

Management

In addition to symptomatic therapy, both of our patients received doxycycline as antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illnesses given that a high number of ticks had been attached for more than 2 days.12,13 Antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illness is controversial. The exception is Lyme disease transmitted by nymphal or adult I scapularis when specific conditions are met: the bite must have occurred in an endemic area, doxycycline cannot be contraindicated, estimated duration of attachment is at least 36 hours, and prophylaxis must be started within 72 hours of tick removal.13 There are no official recommendations for the A americanum species or for larval-stage ticks of any species. Larval-stage ticks acting as vectors for disease transmission is not well documented in recent literature, and there currently is limited evidence supporting prophylactic antibiotics for larval tick bites. The presence of spotted fever rickettsioses has been reported (with the exception of Rickettsia rickettsii and Ehrlichia chaffeensis) in larval A americanum ticks, suggesting a theoretical possibility that they could act as disease vectors.3,8,11,14-17 At a minimum, both prompt tick removal and close patient follow-up is warranted.

Conclusion

Human infestation with larval ticks is a common occurrence but can present a diagnostic challenge to an unfamiliar physician. We encourage consideration of larval tick infestation as the etiology of multiple or diffuse pruritic papules with a history of outdoor exposure.

- Sonenshine DE. Biology of Ticks. New York, NY: Oxford University; 1991.

- Alexander JOD. The effects of tick bites. In: Alexander JOD. Arthropods and Human Skin. London, England: Springer London; 1984:363-382.

- Duckworth PF Jr, Hayden GF, Reed CN. Human infestation by Amblyomma americanum larvae (“seed ticks”). South Med J. 1985;78:751-753.

- Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897-928.

- Cropley TG. William Byrd on ticks, 1728. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:187.

- Goddard J. A ten-year study of tick biting in Mississippi: implications for human disease transmission. J Agromedicine. 2002;8:25-32.

- Goddard J, Portugal JS. Cutaneous lesions due to bites by larval Amblyomma americanum ticks. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1373-1375.

- Fibeger EA, Erickson QL, Weintraub BD, et al. Larval tick infestation: a case report and review of tick-borne disease. Cutis. 2008;82:38-46.

- Jones BE. Human ‘seed tick’ infestation: Amblyomma americanum larvae. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:812-814.

- Fisher EJ, Mo J, Lucky AW. Multiple pruritic papules from lone star tick larvae bites. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:491-494.

- Culp JS. Seed ticks. Am Fam Physician. 1987;36:121-123.

- Perea AE, Hinckley AF, Mead PS. Tick bite prophylaxis: results from a 2012 survey of healthcare providers. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:388-392.

- Tick bites/prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/tick-bites-prevention.html. Revised January 10, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

- Moncayo AC, Cohen SB, Fritzen CM, et al. Absence of Rickettsia rickettsii and occurrence of other spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from Tennessee. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:653-657.

- Castellaw AH, Showers J, Goddard J, et al. Detection of vector-borne agents in lone star ticks, Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae), from Mississippi. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:473-476.

- Stromdahl EY, Vince MA, Billingsley PM, et al. Rickettsia amblyommii infecting Amblyomma americanum larvae. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:15-24.

- Long SW, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2003;40:1000-1004.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 65-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic in July with a pruritic rash of 2 days’ duration that started on the back and spread diffusely. The patient gardened regularly. Physical examination showed inflammatory papules and pustules on the back (Figure 1), as well as the groin, breasts, and ears. There was a punctate black dot in the center of some papules, and dermoscopy revealed ticks (Figure 2). Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage lone star ticks (Figure 3). The patient was prescribed topical steroids for pruritus as well as oral doxycycline for prophylaxis against tick-borne illnesses.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man presented to the same clinic in July with pruritic lesions on the back, legs, ankles, and scrotum of 3 days’ duration that first appeared 24 hours after performing yardwork. Physical examination revealed diffusely distributed papules, pustules, and vesicles on the back (Figure 4). Some papules featured a punctate black dot in the center (similar to patient 1), and dermoscopy again revealed ticks. Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage ticks. The patient was treated with topical steroids and oral antihistamines for pruritus as well as prophylactic oral doxycycline.

Comment

Ticks are well-known human parasites, representing the second most common vector of human infectious disease.1 Ticks have 3 motile stages: larva (or “seed”), nymph, and adult. They can bite humans during all stages. Larval ticks, distinguished by having 6 legs rather than 8 legs in nymphs and adults, can attack in droves and cause an infestation that presents as diffuse, pruritic, erythematous papules and pustules.2-4 The first report of larval tick infestation in humans may have been in 1728 by William Byrd who described finding ticks on the skin that were too small to see without a microscope.5

Identification

The ticks in both of our cases were lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). The larval stage of A americanum is a proven cause of cutaneous reaction.6,7 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the terms tick, seed tick, or tick bite in combination with rash, eruption, infestation, papule, pustule, or pruritic revealed 6 reported cases of larval tick infestation in the literature (including our case); 5 were caused by A americanum and 1 by Ixodes dammini (now known as Ixodes scapularis); all occurred in July or August.3,7-10 This time frame is consistent with the general tick life cycle across species: Adults feed from April to June, then lay eggs that hatch into larval ticks within 4 to 6 weeks. After hatching, larval ticks climb grass and weeds awaiting a passing host.4

Diagnosis

Larval tick infestation remains a frequently misdiagnosed etiology of diffuse pruritic papules and pustules, especially in urban settings where physicians are less likely to be familiar with this type of manifestation.3,9-11 Larval ticks are submillimeter in size and difficult to appreciate with the naked eye, contributing to misdiagnosis. A punctate black dot may sometimes be seen in papules; however, dermoscopy is critical for accurate diagnosis, as hemorrhagic crust is a frequent misdiagnosis.

Management

In addition to symptomatic therapy, both of our patients received doxycycline as antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illnesses given that a high number of ticks had been attached for more than 2 days.12,13 Antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illness is controversial. The exception is Lyme disease transmitted by nymphal or adult I scapularis when specific conditions are met: the bite must have occurred in an endemic area, doxycycline cannot be contraindicated, estimated duration of attachment is at least 36 hours, and prophylaxis must be started within 72 hours of tick removal.13 There are no official recommendations for the A americanum species or for larval-stage ticks of any species. Larval-stage ticks acting as vectors for disease transmission is not well documented in recent literature, and there currently is limited evidence supporting prophylactic antibiotics for larval tick bites. The presence of spotted fever rickettsioses has been reported (with the exception of Rickettsia rickettsii and Ehrlichia chaffeensis) in larval A americanum ticks, suggesting a theoretical possibility that they could act as disease vectors.3,8,11,14-17 At a minimum, both prompt tick removal and close patient follow-up is warranted.

Conclusion

Human infestation with larval ticks is a common occurrence but can present a diagnostic challenge to an unfamiliar physician. We encourage consideration of larval tick infestation as the etiology of multiple or diffuse pruritic papules with a history of outdoor exposure.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 65-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic in July with a pruritic rash of 2 days’ duration that started on the back and spread diffusely. The patient gardened regularly. Physical examination showed inflammatory papules and pustules on the back (Figure 1), as well as the groin, breasts, and ears. There was a punctate black dot in the center of some papules, and dermoscopy revealed ticks (Figure 2). Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage lone star ticks (Figure 3). The patient was prescribed topical steroids for pruritus as well as oral doxycycline for prophylaxis against tick-borne illnesses.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man presented to the same clinic in July with pruritic lesions on the back, legs, ankles, and scrotum of 3 days’ duration that first appeared 24 hours after performing yardwork. Physical examination revealed diffusely distributed papules, pustules, and vesicles on the back (Figure 4). Some papules featured a punctate black dot in the center (similar to patient 1), and dermoscopy again revealed ticks. Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage ticks. The patient was treated with topical steroids and oral antihistamines for pruritus as well as prophylactic oral doxycycline.

Comment

Ticks are well-known human parasites, representing the second most common vector of human infectious disease.1 Ticks have 3 motile stages: larva (or “seed”), nymph, and adult. They can bite humans during all stages. Larval ticks, distinguished by having 6 legs rather than 8 legs in nymphs and adults, can attack in droves and cause an infestation that presents as diffuse, pruritic, erythematous papules and pustules.2-4 The first report of larval tick infestation in humans may have been in 1728 by William Byrd who described finding ticks on the skin that were too small to see without a microscope.5

Identification

The ticks in both of our cases were lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). The larval stage of A americanum is a proven cause of cutaneous reaction.6,7 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the terms tick, seed tick, or tick bite in combination with rash, eruption, infestation, papule, pustule, or pruritic revealed 6 reported cases of larval tick infestation in the literature (including our case); 5 were caused by A americanum and 1 by Ixodes dammini (now known as Ixodes scapularis); all occurred in July or August.3,7-10 This time frame is consistent with the general tick life cycle across species: Adults feed from April to June, then lay eggs that hatch into larval ticks within 4 to 6 weeks. After hatching, larval ticks climb grass and weeds awaiting a passing host.4

Diagnosis

Larval tick infestation remains a frequently misdiagnosed etiology of diffuse pruritic papules and pustules, especially in urban settings where physicians are less likely to be familiar with this type of manifestation.3,9-11 Larval ticks are submillimeter in size and difficult to appreciate with the naked eye, contributing to misdiagnosis. A punctate black dot may sometimes be seen in papules; however, dermoscopy is critical for accurate diagnosis, as hemorrhagic crust is a frequent misdiagnosis.

Management

In addition to symptomatic therapy, both of our patients received doxycycline as antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illnesses given that a high number of ticks had been attached for more than 2 days.12,13 Antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illness is controversial. The exception is Lyme disease transmitted by nymphal or adult I scapularis when specific conditions are met: the bite must have occurred in an endemic area, doxycycline cannot be contraindicated, estimated duration of attachment is at least 36 hours, and prophylaxis must be started within 72 hours of tick removal.13 There are no official recommendations for the A americanum species or for larval-stage ticks of any species. Larval-stage ticks acting as vectors for disease transmission is not well documented in recent literature, and there currently is limited evidence supporting prophylactic antibiotics for larval tick bites. The presence of spotted fever rickettsioses has been reported (with the exception of Rickettsia rickettsii and Ehrlichia chaffeensis) in larval A americanum ticks, suggesting a theoretical possibility that they could act as disease vectors.3,8,11,14-17 At a minimum, both prompt tick removal and close patient follow-up is warranted.

Conclusion

Human infestation with larval ticks is a common occurrence but can present a diagnostic challenge to an unfamiliar physician. We encourage consideration of larval tick infestation as the etiology of multiple or diffuse pruritic papules with a history of outdoor exposure.

- Sonenshine DE. Biology of Ticks. New York, NY: Oxford University; 1991.

- Alexander JOD. The effects of tick bites. In: Alexander JOD. Arthropods and Human Skin. London, England: Springer London; 1984:363-382.

- Duckworth PF Jr, Hayden GF, Reed CN. Human infestation by Amblyomma americanum larvae (“seed ticks”). South Med J. 1985;78:751-753.

- Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897-928.

- Cropley TG. William Byrd on ticks, 1728. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:187.

- Goddard J. A ten-year study of tick biting in Mississippi: implications for human disease transmission. J Agromedicine. 2002;8:25-32.

- Goddard J, Portugal JS. Cutaneous lesions due to bites by larval Amblyomma americanum ticks. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1373-1375.

- Fibeger EA, Erickson QL, Weintraub BD, et al. Larval tick infestation: a case report and review of tick-borne disease. Cutis. 2008;82:38-46.

- Jones BE. Human ‘seed tick’ infestation: Amblyomma americanum larvae. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:812-814.

- Fisher EJ, Mo J, Lucky AW. Multiple pruritic papules from lone star tick larvae bites. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:491-494.

- Culp JS. Seed ticks. Am Fam Physician. 1987;36:121-123.

- Perea AE, Hinckley AF, Mead PS. Tick bite prophylaxis: results from a 2012 survey of healthcare providers. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:388-392.

- Tick bites/prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/tick-bites-prevention.html. Revised January 10, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

- Moncayo AC, Cohen SB, Fritzen CM, et al. Absence of Rickettsia rickettsii and occurrence of other spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from Tennessee. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:653-657.

- Castellaw AH, Showers J, Goddard J, et al. Detection of vector-borne agents in lone star ticks, Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae), from Mississippi. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:473-476.

- Stromdahl EY, Vince MA, Billingsley PM, et al. Rickettsia amblyommii infecting Amblyomma americanum larvae. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:15-24.

- Long SW, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2003;40:1000-1004.

- Sonenshine DE. Biology of Ticks. New York, NY: Oxford University; 1991.

- Alexander JOD. The effects of tick bites. In: Alexander JOD. Arthropods and Human Skin. London, England: Springer London; 1984:363-382.

- Duckworth PF Jr, Hayden GF, Reed CN. Human infestation by Amblyomma americanum larvae (“seed ticks”). South Med J. 1985;78:751-753.

- Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897-928.

- Cropley TG. William Byrd on ticks, 1728. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:187.

- Goddard J. A ten-year study of tick biting in Mississippi: implications for human disease transmission. J Agromedicine. 2002;8:25-32.

- Goddard J, Portugal JS. Cutaneous lesions due to bites by larval Amblyomma americanum ticks. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1373-1375.

- Fibeger EA, Erickson QL, Weintraub BD, et al. Larval tick infestation: a case report and review of tick-borne disease. Cutis. 2008;82:38-46.

- Jones BE. Human ‘seed tick’ infestation: Amblyomma americanum larvae. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:812-814.

- Fisher EJ, Mo J, Lucky AW. Multiple pruritic papules from lone star tick larvae bites. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:491-494.

- Culp JS. Seed ticks. Am Fam Physician. 1987;36:121-123.