User login

Bundled payment for OA surgery linked to more emergency department visits

And therein lies a key lesson for health policy makers who have embraced bundled payments to reduce rising health care costs, Mayilee Canizares, PhD, observed at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

In Ontario, with patients discharged sooner and directly to home, there was the negative impact of increased emergency department visits after surgery, Dr. Canizares, of the University Health Network in Toronto, said at OARSI 2019 World Congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. “Our findings highlight the importance of coordinating the appropriate support services as well as the need to continue assessing the optimal discharge care plan for osteoarthritis patients undergoing surgery.”

Dr. Canizares’ study of the Ontario-wide experience with orthopedic surgery for osteoarthritis during 2004-2016 received the OARSI 2019 award for the meeting’s top-rated study in clinical epidemiology/health services research.

Using administrative data from Canada’s national health care system, Dr. Canizares and her coinvestigators found that the number of individuals undergoing elective orthopedic surgery for osteoarthritis ballooned from 22,700 in 2004 to 41,900 in 2016, representing an increase from 246 to 381 procedures per 100,000 people. During this time, the mean length of stay declined from about 5 days to just under 3 days, the 30-day readmission rate dropped from 4.2% to 3.4%, and the rate of emergency department visits within 30 days post discharge rose steadily from 8.7% in 2004 to 14.1% in 2016.

Roughly half of the operations were total knee replacements and one-third were hip replacements. The profile of patients undergoing surgery changed little over the course of the 12-year study with the exception that in more recent years patients presented with more comorbidities: Indeed, three or more comorbid conditions were present in 2.9% of the surgical patients in 2004 compared to 4.2% in 2016.

In multivariate logistic regression analyses, patient characteristics didn’t explain the change over time in early readmission or unplanned emergency department visit rates. However, discharge disposition did: By 2014, more patients were being discharged home, and in nearly half of cases that was being done without support.

Dr. Canizares reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, funded by the Toronto General and Western Hospital Foundation.

SOURCE: Canizares M. OARSI, Abstract 16.

And therein lies a key lesson for health policy makers who have embraced bundled payments to reduce rising health care costs, Mayilee Canizares, PhD, observed at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

In Ontario, with patients discharged sooner and directly to home, there was the negative impact of increased emergency department visits after surgery, Dr. Canizares, of the University Health Network in Toronto, said at OARSI 2019 World Congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. “Our findings highlight the importance of coordinating the appropriate support services as well as the need to continue assessing the optimal discharge care plan for osteoarthritis patients undergoing surgery.”

Dr. Canizares’ study of the Ontario-wide experience with orthopedic surgery for osteoarthritis during 2004-2016 received the OARSI 2019 award for the meeting’s top-rated study in clinical epidemiology/health services research.

Using administrative data from Canada’s national health care system, Dr. Canizares and her coinvestigators found that the number of individuals undergoing elective orthopedic surgery for osteoarthritis ballooned from 22,700 in 2004 to 41,900 in 2016, representing an increase from 246 to 381 procedures per 100,000 people. During this time, the mean length of stay declined from about 5 days to just under 3 days, the 30-day readmission rate dropped from 4.2% to 3.4%, and the rate of emergency department visits within 30 days post discharge rose steadily from 8.7% in 2004 to 14.1% in 2016.

Roughly half of the operations were total knee replacements and one-third were hip replacements. The profile of patients undergoing surgery changed little over the course of the 12-year study with the exception that in more recent years patients presented with more comorbidities: Indeed, three or more comorbid conditions were present in 2.9% of the surgical patients in 2004 compared to 4.2% in 2016.

In multivariate logistic regression analyses, patient characteristics didn’t explain the change over time in early readmission or unplanned emergency department visit rates. However, discharge disposition did: By 2014, more patients were being discharged home, and in nearly half of cases that was being done without support.

Dr. Canizares reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, funded by the Toronto General and Western Hospital Foundation.

SOURCE: Canizares M. OARSI, Abstract 16.

And therein lies a key lesson for health policy makers who have embraced bundled payments to reduce rising health care costs, Mayilee Canizares, PhD, observed at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

In Ontario, with patients discharged sooner and directly to home, there was the negative impact of increased emergency department visits after surgery, Dr. Canizares, of the University Health Network in Toronto, said at OARSI 2019 World Congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. “Our findings highlight the importance of coordinating the appropriate support services as well as the need to continue assessing the optimal discharge care plan for osteoarthritis patients undergoing surgery.”

Dr. Canizares’ study of the Ontario-wide experience with orthopedic surgery for osteoarthritis during 2004-2016 received the OARSI 2019 award for the meeting’s top-rated study in clinical epidemiology/health services research.

Using administrative data from Canada’s national health care system, Dr. Canizares and her coinvestigators found that the number of individuals undergoing elective orthopedic surgery for osteoarthritis ballooned from 22,700 in 2004 to 41,900 in 2016, representing an increase from 246 to 381 procedures per 100,000 people. During this time, the mean length of stay declined from about 5 days to just under 3 days, the 30-day readmission rate dropped from 4.2% to 3.4%, and the rate of emergency department visits within 30 days post discharge rose steadily from 8.7% in 2004 to 14.1% in 2016.

Roughly half of the operations were total knee replacements and one-third were hip replacements. The profile of patients undergoing surgery changed little over the course of the 12-year study with the exception that in more recent years patients presented with more comorbidities: Indeed, three or more comorbid conditions were present in 2.9% of the surgical patients in 2004 compared to 4.2% in 2016.

In multivariate logistic regression analyses, patient characteristics didn’t explain the change over time in early readmission or unplanned emergency department visit rates. However, discharge disposition did: By 2014, more patients were being discharged home, and in nearly half of cases that was being done without support.

Dr. Canizares reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, funded by the Toronto General and Western Hospital Foundation.

SOURCE: Canizares M. OARSI, Abstract 16.

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

PT beats steroid injections for knee OA

TORONTO – Eight physical therapy sessions spread over 4-6 weeks in patients with knee osteoarthritis provided significantly greater and longer-lasting improvements in both pain and function than an intra-articular corticosteroid injection in a randomized, multicenter trial with 12 months of prospective, blinded follow-up, Daniel I. Rhon, DPT, DSc, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

“Considering the very low utilization rate of physical therapy prior to arthroplasty, perhaps we should more often give it a try before declaring that conservative care has failed and moving on to surgical management,” concluded Dr. Rhon, director of the primary care musculoskeletal research center at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio.

Various studies have shown that close to 50% of patients with knee OA receive one or more intra-articular corticosteroid injections within 5 years prior to undergoing total knee arthroplasty, compared with physical therapy in only about 10% of patients, even though most guidelines rate both as first-line therapies, he noted at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

He presented a randomized trial of 156 patients who sought treatment for pain caused by knee OA at army medical center primary care clinics. To his knowledge, this was the first-ever randomized, head-to-head comparison of the effectiveness of a physical therapy regimen versus corticosteroid injections for knee OA. Because he and his coinvestigators wanted a pragmatic study giving each treatment strategy its due, booster therapy was available to patients who requested it. Patients in the corticosteroid arm were able to receive up to two additional spaced intra-articular injections as needed, while those assigned to the individualized manual physical therapy intervention, which utilized exercises targeting the typical strength and movement deficits found in patients with knee OA, could have up to three additional sessions. At the outset, all participants received education about the benefits of regular low-impact physical activity, weight reduction, and strength and flexibility exercises.

The two treatment groups were comparable except that the physical therapy group had a longer disease duration – a mean of 123 months as compared with 89 in the corticosteroid group – and more radiographically severe disease. Indeed, 60% of patients randomized to physical therapy were Kellgren-Lawrence scale grade III-IV, versus 45% of those assigned to intra-articular corticosteroid injection.

The primary outcome in the study was change in Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score at 12 months. As early as 4 weeks into the study, the physical therapy group showed significantly greater improvement than in the comparison arm: from a mean baseline WOMAC score of 115 to 42.9 at 4 weeks, 42.5 at 6 months, and 38.4 at 1 year. The comparable figures in the intra-articular corticosteroid group were 113.3 at baseline, 53.3 at 4 weeks, 57.9 at 6 months, and 53.8 at 1 year.

“Physical therapy provided clinically important benefit that was superior to corticosteroid injection out to 1 year, while also providing the short-term benefit typically sought from corticosteroid injection,” Dr. Rhon observed.

The median improvement in WOMAC score at 1 year was 52% in the corticosteroid group and 71% in the physical therapy arm. About 59% of the physical therapy group experienced at least a 50% reduction in WOMAC score at 12 months, as did 38% of intra-articular injection recipients. The number needed to treat with physical therapy instead of intra-articular corticosteroids in order for one additional patient to achieve at least a 50% improvement in WOMAC score through 1 year of follow-up was four.

“We were a little bit surprised that there was such a large effect size in the study. The effect size in the injection group was bigger than reported in some other trials,” according to Dr. Rhon.

In terms of downstream utilization of health care, there were two knee arthroplasties and one arthroscopy in the study population, all in the intra-articular corticosteroid group. Seven patients in the intra-articular steroid group received more than three injections, including one patient with nine. And 13 patients in the physical therapy arm went outside the study in order to receive at least one corticosteroid injection.

One audience member pointed out that the physical therapy approach offers an important side benefit: In addition to improving pain and function, the exercise regimen has a favorable effect on comorbid metabolic diseases commonly associated with knee OA.

“An injection doesn’t achieve that,” he noted.

Dr. Rhon reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the randomized trial, sponsored by Madigan Army Medical Center. He receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs.

SOURCE: Rhon DI et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S32, Abstract 13

TORONTO – Eight physical therapy sessions spread over 4-6 weeks in patients with knee osteoarthritis provided significantly greater and longer-lasting improvements in both pain and function than an intra-articular corticosteroid injection in a randomized, multicenter trial with 12 months of prospective, blinded follow-up, Daniel I. Rhon, DPT, DSc, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

“Considering the very low utilization rate of physical therapy prior to arthroplasty, perhaps we should more often give it a try before declaring that conservative care has failed and moving on to surgical management,” concluded Dr. Rhon, director of the primary care musculoskeletal research center at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio.

Various studies have shown that close to 50% of patients with knee OA receive one or more intra-articular corticosteroid injections within 5 years prior to undergoing total knee arthroplasty, compared with physical therapy in only about 10% of patients, even though most guidelines rate both as first-line therapies, he noted at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

He presented a randomized trial of 156 patients who sought treatment for pain caused by knee OA at army medical center primary care clinics. To his knowledge, this was the first-ever randomized, head-to-head comparison of the effectiveness of a physical therapy regimen versus corticosteroid injections for knee OA. Because he and his coinvestigators wanted a pragmatic study giving each treatment strategy its due, booster therapy was available to patients who requested it. Patients in the corticosteroid arm were able to receive up to two additional spaced intra-articular injections as needed, while those assigned to the individualized manual physical therapy intervention, which utilized exercises targeting the typical strength and movement deficits found in patients with knee OA, could have up to three additional sessions. At the outset, all participants received education about the benefits of regular low-impact physical activity, weight reduction, and strength and flexibility exercises.

The two treatment groups were comparable except that the physical therapy group had a longer disease duration – a mean of 123 months as compared with 89 in the corticosteroid group – and more radiographically severe disease. Indeed, 60% of patients randomized to physical therapy were Kellgren-Lawrence scale grade III-IV, versus 45% of those assigned to intra-articular corticosteroid injection.

The primary outcome in the study was change in Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score at 12 months. As early as 4 weeks into the study, the physical therapy group showed significantly greater improvement than in the comparison arm: from a mean baseline WOMAC score of 115 to 42.9 at 4 weeks, 42.5 at 6 months, and 38.4 at 1 year. The comparable figures in the intra-articular corticosteroid group were 113.3 at baseline, 53.3 at 4 weeks, 57.9 at 6 months, and 53.8 at 1 year.

“Physical therapy provided clinically important benefit that was superior to corticosteroid injection out to 1 year, while also providing the short-term benefit typically sought from corticosteroid injection,” Dr. Rhon observed.

The median improvement in WOMAC score at 1 year was 52% in the corticosteroid group and 71% in the physical therapy arm. About 59% of the physical therapy group experienced at least a 50% reduction in WOMAC score at 12 months, as did 38% of intra-articular injection recipients. The number needed to treat with physical therapy instead of intra-articular corticosteroids in order for one additional patient to achieve at least a 50% improvement in WOMAC score through 1 year of follow-up was four.

“We were a little bit surprised that there was such a large effect size in the study. The effect size in the injection group was bigger than reported in some other trials,” according to Dr. Rhon.

In terms of downstream utilization of health care, there were two knee arthroplasties and one arthroscopy in the study population, all in the intra-articular corticosteroid group. Seven patients in the intra-articular steroid group received more than three injections, including one patient with nine. And 13 patients in the physical therapy arm went outside the study in order to receive at least one corticosteroid injection.

One audience member pointed out that the physical therapy approach offers an important side benefit: In addition to improving pain and function, the exercise regimen has a favorable effect on comorbid metabolic diseases commonly associated with knee OA.

“An injection doesn’t achieve that,” he noted.

Dr. Rhon reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the randomized trial, sponsored by Madigan Army Medical Center. He receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs.

SOURCE: Rhon DI et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S32, Abstract 13

TORONTO – Eight physical therapy sessions spread over 4-6 weeks in patients with knee osteoarthritis provided significantly greater and longer-lasting improvements in both pain and function than an intra-articular corticosteroid injection in a randomized, multicenter trial with 12 months of prospective, blinded follow-up, Daniel I. Rhon, DPT, DSc, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

“Considering the very low utilization rate of physical therapy prior to arthroplasty, perhaps we should more often give it a try before declaring that conservative care has failed and moving on to surgical management,” concluded Dr. Rhon, director of the primary care musculoskeletal research center at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio.

Various studies have shown that close to 50% of patients with knee OA receive one or more intra-articular corticosteroid injections within 5 years prior to undergoing total knee arthroplasty, compared with physical therapy in only about 10% of patients, even though most guidelines rate both as first-line therapies, he noted at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

He presented a randomized trial of 156 patients who sought treatment for pain caused by knee OA at army medical center primary care clinics. To his knowledge, this was the first-ever randomized, head-to-head comparison of the effectiveness of a physical therapy regimen versus corticosteroid injections for knee OA. Because he and his coinvestigators wanted a pragmatic study giving each treatment strategy its due, booster therapy was available to patients who requested it. Patients in the corticosteroid arm were able to receive up to two additional spaced intra-articular injections as needed, while those assigned to the individualized manual physical therapy intervention, which utilized exercises targeting the typical strength and movement deficits found in patients with knee OA, could have up to three additional sessions. At the outset, all participants received education about the benefits of regular low-impact physical activity, weight reduction, and strength and flexibility exercises.

The two treatment groups were comparable except that the physical therapy group had a longer disease duration – a mean of 123 months as compared with 89 in the corticosteroid group – and more radiographically severe disease. Indeed, 60% of patients randomized to physical therapy were Kellgren-Lawrence scale grade III-IV, versus 45% of those assigned to intra-articular corticosteroid injection.

The primary outcome in the study was change in Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score at 12 months. As early as 4 weeks into the study, the physical therapy group showed significantly greater improvement than in the comparison arm: from a mean baseline WOMAC score of 115 to 42.9 at 4 weeks, 42.5 at 6 months, and 38.4 at 1 year. The comparable figures in the intra-articular corticosteroid group were 113.3 at baseline, 53.3 at 4 weeks, 57.9 at 6 months, and 53.8 at 1 year.

“Physical therapy provided clinically important benefit that was superior to corticosteroid injection out to 1 year, while also providing the short-term benefit typically sought from corticosteroid injection,” Dr. Rhon observed.

The median improvement in WOMAC score at 1 year was 52% in the corticosteroid group and 71% in the physical therapy arm. About 59% of the physical therapy group experienced at least a 50% reduction in WOMAC score at 12 months, as did 38% of intra-articular injection recipients. The number needed to treat with physical therapy instead of intra-articular corticosteroids in order for one additional patient to achieve at least a 50% improvement in WOMAC score through 1 year of follow-up was four.

“We were a little bit surprised that there was such a large effect size in the study. The effect size in the injection group was bigger than reported in some other trials,” according to Dr. Rhon.

In terms of downstream utilization of health care, there were two knee arthroplasties and one arthroscopy in the study population, all in the intra-articular corticosteroid group. Seven patients in the intra-articular steroid group received more than three injections, including one patient with nine. And 13 patients in the physical therapy arm went outside the study in order to receive at least one corticosteroid injection.

One audience member pointed out that the physical therapy approach offers an important side benefit: In addition to improving pain and function, the exercise regimen has a favorable effect on comorbid metabolic diseases commonly associated with knee OA.

“An injection doesn’t achieve that,” he noted.

Dr. Rhon reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the randomized trial, sponsored by Madigan Army Medical Center. He receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs.

SOURCE: Rhon DI et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S32, Abstract 13

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

High-intensity statins may cut risk of joint replacement

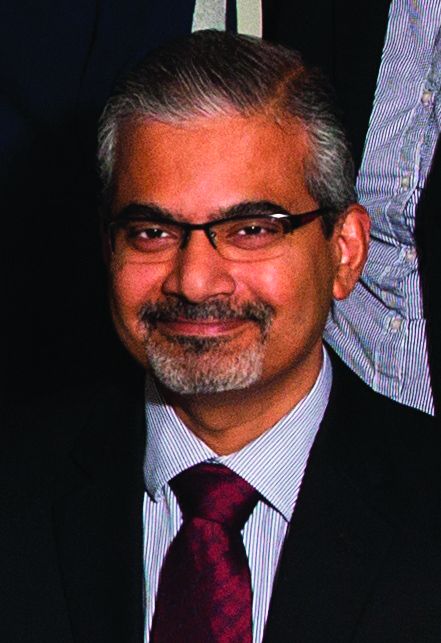

TORONTO – comparing nearly 180,000 statin users with an equal number of propensity-matched nonusers, Jie Wei, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Less intensive statin therapy was associated with significantly less need for joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients, but not in those with osteoarthritis, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“In summary, statins may reduce the risk of joint replacement, especially when given at high strength and in people with rheumatoid arthritis,” said Dr. Wei, an epidemiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Central South University in Changsha, Hunan, China.

She was quick to note that this study can’t be considered the final, definitive word on the topic, since other investigators’ studies of the relationship between statin usage and joint replacement surgery for arthritis have yielded conflicting results. However, given the thoroughly established super-favorable risk/benefit ratio of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, the possibility of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial addressing the joint surgery issue is for ethical reasons a train that’s left the station.

Dr. Wei presented an analysis drawn from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink for the years 1989 through mid-2017. The initial sample included the medical records of 17.1 million patients, or 26% of the total U.K. population. From that massive pool, she and her coinvestigators zeroed in on 178,467 statin users and an equal number of non–statin-user controls under the care of 718 primary care physicians, with the pairs propensity score-matched on the basis of age, gender, locality, comorbid conditions, nonstatin medications, lifestyle factors, and duration of rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. The mean age of the matched pairs was 62 years, 52% were women, and the mean prospective follow-up was 6.5 years.

The use of high-intensity statin therapy – for example, atorvastatin at 40-80 mg/day or rosuvastatin (Crestor) at 20-40 mg/day – was independently associated with a 21% reduction in the risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for osteoarthritis and a 90% reduction for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers. Notably, joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis was roughly 25-fold more common than for rheumatoid arthritis.

Statin therapy overall, including the more widely prescribed low- and intermediate-intensity regimens, was associated with a 23% reduction in joint replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers, but had no significant impact on surgery for the osteoarthritis population.

A couple of distinguished American rheumatologists in the audience rose to voice reluctance about drawing broad conclusions from this study.

“Bias, as you’ve said yourself, is a bit of a concern,” said David T. Felson, MD, professor of medicine and public health and director of clinical epidemiology at Boston University.

He was troubled that the study design was such that anyone who filled as few as two statin prescriptions during the more than 6-year study period was categorized as a statin user. That, he said, muddies the waters. Does the database contain information on duration of statin therapy, and whether joint replacement surgery was more likely to occur when patients were on or off statin therapy? he asked.

It does, Dr. Wei replied, adding that she will take that suggestion for additional analysis back to her international team of coinvestigators.

“It seems to me,” said Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, “that the major risk of potential bias is that people who were provided high-intensity statins were prescribed that because they were at risk for or had cardiac disease.”

That high cardiovascular risk might have curbed orthopedic surgeons’ enthusiasm to operate. Thus, it would be helpful to learn whether patients who underwent joint replacement were less likely to have undergone coronary revascularization or other cardiac interventions than were those without joint replacement, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Dr. Wei agreed that confounding by indication is always a possibility in an observational study such as this. Identification of a plausible mechanism by which statins might reduce the risk of joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis – something that hasn’t happened yet – would help counter such concerns.

She noted that a separate recent analysis of the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink by other investigators concluded that statin therapy started up to 5 years following total hip or knee replacement was associated with a significantly reduced risk of revision arthroplasty. Moreover, the benefit was treatment duration-dependent: Patients on statin therapy for more than 5 years were 26% less likely to undergo revision arthroplasty than were those on a statin for less than 1 year (J Rheumatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180574).

On the other hand, Swedish investigators found that statin use wasn’t associated with a reduced risk of consultation or surgery for osteoarthritis in a pooled analysis of four cohort studies totaling more than 132,000 Swedes followed for 7.5 years (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Nov;25[11]:1804-13).

Dr. Wei reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders in Hunan, China, and several British universities.

SOURCE: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

TORONTO – comparing nearly 180,000 statin users with an equal number of propensity-matched nonusers, Jie Wei, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Less intensive statin therapy was associated with significantly less need for joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients, but not in those with osteoarthritis, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“In summary, statins may reduce the risk of joint replacement, especially when given at high strength and in people with rheumatoid arthritis,” said Dr. Wei, an epidemiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Central South University in Changsha, Hunan, China.

She was quick to note that this study can’t be considered the final, definitive word on the topic, since other investigators’ studies of the relationship between statin usage and joint replacement surgery for arthritis have yielded conflicting results. However, given the thoroughly established super-favorable risk/benefit ratio of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, the possibility of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial addressing the joint surgery issue is for ethical reasons a train that’s left the station.

Dr. Wei presented an analysis drawn from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink for the years 1989 through mid-2017. The initial sample included the medical records of 17.1 million patients, or 26% of the total U.K. population. From that massive pool, she and her coinvestigators zeroed in on 178,467 statin users and an equal number of non–statin-user controls under the care of 718 primary care physicians, with the pairs propensity score-matched on the basis of age, gender, locality, comorbid conditions, nonstatin medications, lifestyle factors, and duration of rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. The mean age of the matched pairs was 62 years, 52% were women, and the mean prospective follow-up was 6.5 years.

The use of high-intensity statin therapy – for example, atorvastatin at 40-80 mg/day or rosuvastatin (Crestor) at 20-40 mg/day – was independently associated with a 21% reduction in the risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for osteoarthritis and a 90% reduction for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers. Notably, joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis was roughly 25-fold more common than for rheumatoid arthritis.

Statin therapy overall, including the more widely prescribed low- and intermediate-intensity regimens, was associated with a 23% reduction in joint replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers, but had no significant impact on surgery for the osteoarthritis population.

A couple of distinguished American rheumatologists in the audience rose to voice reluctance about drawing broad conclusions from this study.

“Bias, as you’ve said yourself, is a bit of a concern,” said David T. Felson, MD, professor of medicine and public health and director of clinical epidemiology at Boston University.

He was troubled that the study design was such that anyone who filled as few as two statin prescriptions during the more than 6-year study period was categorized as a statin user. That, he said, muddies the waters. Does the database contain information on duration of statin therapy, and whether joint replacement surgery was more likely to occur when patients were on or off statin therapy? he asked.

It does, Dr. Wei replied, adding that she will take that suggestion for additional analysis back to her international team of coinvestigators.

“It seems to me,” said Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, “that the major risk of potential bias is that people who were provided high-intensity statins were prescribed that because they were at risk for or had cardiac disease.”

That high cardiovascular risk might have curbed orthopedic surgeons’ enthusiasm to operate. Thus, it would be helpful to learn whether patients who underwent joint replacement were less likely to have undergone coronary revascularization or other cardiac interventions than were those without joint replacement, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Dr. Wei agreed that confounding by indication is always a possibility in an observational study such as this. Identification of a plausible mechanism by which statins might reduce the risk of joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis – something that hasn’t happened yet – would help counter such concerns.

She noted that a separate recent analysis of the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink by other investigators concluded that statin therapy started up to 5 years following total hip or knee replacement was associated with a significantly reduced risk of revision arthroplasty. Moreover, the benefit was treatment duration-dependent: Patients on statin therapy for more than 5 years were 26% less likely to undergo revision arthroplasty than were those on a statin for less than 1 year (J Rheumatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180574).

On the other hand, Swedish investigators found that statin use wasn’t associated with a reduced risk of consultation or surgery for osteoarthritis in a pooled analysis of four cohort studies totaling more than 132,000 Swedes followed for 7.5 years (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Nov;25[11]:1804-13).

Dr. Wei reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders in Hunan, China, and several British universities.

SOURCE: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

TORONTO – comparing nearly 180,000 statin users with an equal number of propensity-matched nonusers, Jie Wei, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Less intensive statin therapy was associated with significantly less need for joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis patients, but not in those with osteoarthritis, she said at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“In summary, statins may reduce the risk of joint replacement, especially when given at high strength and in people with rheumatoid arthritis,” said Dr. Wei, an epidemiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Central South University in Changsha, Hunan, China.

She was quick to note that this study can’t be considered the final, definitive word on the topic, since other investigators’ studies of the relationship between statin usage and joint replacement surgery for arthritis have yielded conflicting results. However, given the thoroughly established super-favorable risk/benefit ratio of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, the possibility of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial addressing the joint surgery issue is for ethical reasons a train that’s left the station.

Dr. Wei presented an analysis drawn from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink for the years 1989 through mid-2017. The initial sample included the medical records of 17.1 million patients, or 26% of the total U.K. population. From that massive pool, she and her coinvestigators zeroed in on 178,467 statin users and an equal number of non–statin-user controls under the care of 718 primary care physicians, with the pairs propensity score-matched on the basis of age, gender, locality, comorbid conditions, nonstatin medications, lifestyle factors, and duration of rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. The mean age of the matched pairs was 62 years, 52% were women, and the mean prospective follow-up was 6.5 years.

The use of high-intensity statin therapy – for example, atorvastatin at 40-80 mg/day or rosuvastatin (Crestor) at 20-40 mg/day – was independently associated with a 21% reduction in the risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for osteoarthritis and a 90% reduction for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers. Notably, joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis was roughly 25-fold more common than for rheumatoid arthritis.

Statin therapy overall, including the more widely prescribed low- and intermediate-intensity regimens, was associated with a 23% reduction in joint replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis, compared with statin nonusers, but had no significant impact on surgery for the osteoarthritis population.

A couple of distinguished American rheumatologists in the audience rose to voice reluctance about drawing broad conclusions from this study.

“Bias, as you’ve said yourself, is a bit of a concern,” said David T. Felson, MD, professor of medicine and public health and director of clinical epidemiology at Boston University.

He was troubled that the study design was such that anyone who filled as few as two statin prescriptions during the more than 6-year study period was categorized as a statin user. That, he said, muddies the waters. Does the database contain information on duration of statin therapy, and whether joint replacement surgery was more likely to occur when patients were on or off statin therapy? he asked.

It does, Dr. Wei replied, adding that she will take that suggestion for additional analysis back to her international team of coinvestigators.

“It seems to me,” said Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, “that the major risk of potential bias is that people who were provided high-intensity statins were prescribed that because they were at risk for or had cardiac disease.”

That high cardiovascular risk might have curbed orthopedic surgeons’ enthusiasm to operate. Thus, it would be helpful to learn whether patients who underwent joint replacement were less likely to have undergone coronary revascularization or other cardiac interventions than were those without joint replacement, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Dr. Wei agreed that confounding by indication is always a possibility in an observational study such as this. Identification of a plausible mechanism by which statins might reduce the risk of joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis – something that hasn’t happened yet – would help counter such concerns.

She noted that a separate recent analysis of the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink by other investigators concluded that statin therapy started up to 5 years following total hip or knee replacement was associated with a significantly reduced risk of revision arthroplasty. Moreover, the benefit was treatment duration-dependent: Patients on statin therapy for more than 5 years were 26% less likely to undergo revision arthroplasty than were those on a statin for less than 1 year (J Rheumatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180574).

On the other hand, Swedish investigators found that statin use wasn’t associated with a reduced risk of consultation or surgery for osteoarthritis in a pooled analysis of four cohort studies totaling more than 132,000 Swedes followed for 7.5 years (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Nov;25[11]:1804-13).

Dr. Wei reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders in Hunan, China, and several British universities.

SOURCE: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

Key clinical point: High-intensity statin therapy may reduce need for joint replacement in arthritis.

Major finding: The risk of knee or hip replacement surgery for rheumatoid arthritis was slashed by 90%, and by 21% for osteoarthritis.

Study details: This study included nearly 180,000 statin users propensity score-matched to an equal number of nonusers and prospectively followed for a mean of 6.5 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Clinical Research Center of Geriatric Disorders at Central South University in Hunan, China, and by several British universities. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Sarmanova A et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S78-S79. Abstract 77.

Restricting opioids after knee surgery did not increase refills

according to a study in the Journal of Arthroplasty.

Contrary to concerns that restrictive opioid prescribing might increase the number of patient call-ins and refill requests, one academic institution had significantly fewer call-ins and refills after it implemented a strict postoperative opioid prescribing protocol on Jan. 1, 2018.

“Orthopedic surgeons might be reluctant to change practice without evidence that new, more-restrictive practice will not impede patient care,” the researchers wrote. “As the current study demonstrates, there is room to significantly decrease postoperative opioid prescriptions in total joint arthroplasty. This places patients at lower risk of opioid abuse and diversion without significantly altering the risk of postoperative complications or compromising postoperative pain control.”

Opioid overuse is a major public health concern, and orthopedic surgeons may overprescribe opioids after surgery. The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City implemented strict postoperative opioid prescription guidelines that are based on the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines. As part of the protocol, patients receive a preoperative education session that emphasizes risks associated with opioid use. Before initiating this protocol, postoperative drug choice and quantity had not been standardized.

To examine changes in opioid prescriptions and the number of call-ins, postoperative complications, and prescription refill requests after the implementation of the restrictive opioid prescribing protocol, investigators at the institution conducted a retrospective study.

Andrew J. Holte, a researcher in the department of orthopedics and rehabilitation, and his colleagues reviewed cases from June 2017 to February 2018. Their analysis included 399 patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty.

In all, 282 patients underwent surgery before the restrictive protocol (the historical cohort) and 117 after (the restrictive cohort). In the historical cohort, about 48% of the patients underwent total knee arthroplasty. In the restrictive cohort, about 44% underwent total knee arthroplasty. Patients had an average age of about 61 years, and approximately 52% were women.

According to comparisons of morphine mg equivalents (MME), the historical cohort received significantly larger mean initial opioid prescriptions (752 MME vs. 387 MME), significantly more refills per patient (0.5 vs. 0.3), and significantly more medication through refills (253 MME vs. 84 MME).

“For reference, 50 pills of 5 mg oxycodone is equivalent to 300 MMEs,” the authors noted.

A multivariable model found that younger age and total knee arthroplasty, compared with total hip arthroplasty, were associated with increased likelihood of requests for refills and patient call-ins.

“Surprisingly, there were significantly more patient call-ins and requests for refills of opioids in the historical cohort,” Mr. Holte and his colleagues said. “Although this study did not collect direct data on patient pain scores, we believe that call-ins and requests for refills are sufficient surrogate markers for inadequate pain control.”

The study does not account for prescriptions from other providers or whether patients took none, some, or all of their filled prescriptions. Future studies are needed to assess how reduced opioid prescriptions affect pain and functional outcomes in the long term, the researchers said.

One or more study authors disclosed potential conflicts of interest. The disclosures can be found in Appendix A, Supplementary Data, at the end of the journal article.

SOURCE: Holte AJ et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.022.

according to a study in the Journal of Arthroplasty.

Contrary to concerns that restrictive opioid prescribing might increase the number of patient call-ins and refill requests, one academic institution had significantly fewer call-ins and refills after it implemented a strict postoperative opioid prescribing protocol on Jan. 1, 2018.

“Orthopedic surgeons might be reluctant to change practice without evidence that new, more-restrictive practice will not impede patient care,” the researchers wrote. “As the current study demonstrates, there is room to significantly decrease postoperative opioid prescriptions in total joint arthroplasty. This places patients at lower risk of opioid abuse and diversion without significantly altering the risk of postoperative complications or compromising postoperative pain control.”

Opioid overuse is a major public health concern, and orthopedic surgeons may overprescribe opioids after surgery. The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City implemented strict postoperative opioid prescription guidelines that are based on the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines. As part of the protocol, patients receive a preoperative education session that emphasizes risks associated with opioid use. Before initiating this protocol, postoperative drug choice and quantity had not been standardized.

To examine changes in opioid prescriptions and the number of call-ins, postoperative complications, and prescription refill requests after the implementation of the restrictive opioid prescribing protocol, investigators at the institution conducted a retrospective study.

Andrew J. Holte, a researcher in the department of orthopedics and rehabilitation, and his colleagues reviewed cases from June 2017 to February 2018. Their analysis included 399 patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty.

In all, 282 patients underwent surgery before the restrictive protocol (the historical cohort) and 117 after (the restrictive cohort). In the historical cohort, about 48% of the patients underwent total knee arthroplasty. In the restrictive cohort, about 44% underwent total knee arthroplasty. Patients had an average age of about 61 years, and approximately 52% were women.

According to comparisons of morphine mg equivalents (MME), the historical cohort received significantly larger mean initial opioid prescriptions (752 MME vs. 387 MME), significantly more refills per patient (0.5 vs. 0.3), and significantly more medication through refills (253 MME vs. 84 MME).

“For reference, 50 pills of 5 mg oxycodone is equivalent to 300 MMEs,” the authors noted.

A multivariable model found that younger age and total knee arthroplasty, compared with total hip arthroplasty, were associated with increased likelihood of requests for refills and patient call-ins.

“Surprisingly, there were significantly more patient call-ins and requests for refills of opioids in the historical cohort,” Mr. Holte and his colleagues said. “Although this study did not collect direct data on patient pain scores, we believe that call-ins and requests for refills are sufficient surrogate markers for inadequate pain control.”

The study does not account for prescriptions from other providers or whether patients took none, some, or all of their filled prescriptions. Future studies are needed to assess how reduced opioid prescriptions affect pain and functional outcomes in the long term, the researchers said.

One or more study authors disclosed potential conflicts of interest. The disclosures can be found in Appendix A, Supplementary Data, at the end of the journal article.

SOURCE: Holte AJ et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.022.

according to a study in the Journal of Arthroplasty.

Contrary to concerns that restrictive opioid prescribing might increase the number of patient call-ins and refill requests, one academic institution had significantly fewer call-ins and refills after it implemented a strict postoperative opioid prescribing protocol on Jan. 1, 2018.

“Orthopedic surgeons might be reluctant to change practice without evidence that new, more-restrictive practice will not impede patient care,” the researchers wrote. “As the current study demonstrates, there is room to significantly decrease postoperative opioid prescriptions in total joint arthroplasty. This places patients at lower risk of opioid abuse and diversion without significantly altering the risk of postoperative complications or compromising postoperative pain control.”

Opioid overuse is a major public health concern, and orthopedic surgeons may overprescribe opioids after surgery. The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City implemented strict postoperative opioid prescription guidelines that are based on the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines. As part of the protocol, patients receive a preoperative education session that emphasizes risks associated with opioid use. Before initiating this protocol, postoperative drug choice and quantity had not been standardized.

To examine changes in opioid prescriptions and the number of call-ins, postoperative complications, and prescription refill requests after the implementation of the restrictive opioid prescribing protocol, investigators at the institution conducted a retrospective study.

Andrew J. Holte, a researcher in the department of orthopedics and rehabilitation, and his colleagues reviewed cases from June 2017 to February 2018. Their analysis included 399 patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty.

In all, 282 patients underwent surgery before the restrictive protocol (the historical cohort) and 117 after (the restrictive cohort). In the historical cohort, about 48% of the patients underwent total knee arthroplasty. In the restrictive cohort, about 44% underwent total knee arthroplasty. Patients had an average age of about 61 years, and approximately 52% were women.

According to comparisons of morphine mg equivalents (MME), the historical cohort received significantly larger mean initial opioid prescriptions (752 MME vs. 387 MME), significantly more refills per patient (0.5 vs. 0.3), and significantly more medication through refills (253 MME vs. 84 MME).

“For reference, 50 pills of 5 mg oxycodone is equivalent to 300 MMEs,” the authors noted.

A multivariable model found that younger age and total knee arthroplasty, compared with total hip arthroplasty, were associated with increased likelihood of requests for refills and patient call-ins.

“Surprisingly, there were significantly more patient call-ins and requests for refills of opioids in the historical cohort,” Mr. Holte and his colleagues said. “Although this study did not collect direct data on patient pain scores, we believe that call-ins and requests for refills are sufficient surrogate markers for inadequate pain control.”

The study does not account for prescriptions from other providers or whether patients took none, some, or all of their filled prescriptions. Future studies are needed to assess how reduced opioid prescriptions affect pain and functional outcomes in the long term, the researchers said.

One or more study authors disclosed potential conflicts of interest. The disclosures can be found in Appendix A, Supplementary Data, at the end of the journal article.

SOURCE: Holte AJ et al. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.022.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ARTHROPLASTY

Platelet-rich plasma shows promise in hemophilic arthropathy of the knee

A single intra-articular injection of platelet-rich plasma showed better pain and function scores at 6 months than did weekly injections of hyaluronic acid in patients with hemophilic arthropathy of the knee.

“In patients with chronic knee joint pain, our study shows that treatment with intra-articular [platelet-rich plasma] injection could reduce pain, improve hyperaemia and enhance knee joint function,” wrote Tsung-Ying Li, MD, of Tri-Service General Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan, and his colleagues. The results of the comparison study were published in Haemophilia.

Researchers conducted a nonrandomized, single-center, open-label comparison study of 22 patients with hemophilia A who had chronic hemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Patients were stratified into two treatment groups using a matched sampling method.

“Patients who could commit to hyaluronic acid treatment were allocated to the hyaluronic acid group, otherwise patients were allocated to the platelet‐rich plasma group,” the researchers wrote.

Participants in the hyaluronic acid arm were given five sequential weekly injections and those in the platelet-rich plasma arm received only a single injection. Outcomes were measured via the visual analogue scale (VAS), the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Chinese Version, and ultrasonography to determine synovial change.

Pain and function scores were significantly lower in patients administered intra-articular platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid at 6 months (P less than .05), the researchers reported. However, comparative analysis found no significant differences at earlier follow-up time points.

“Both treatments were found to be effective in reducing pain and improving functional status of the knee,” the researchers wrote.

They acknowledged a key limitation of the study was the short duration of follow-up, which was due to budget restrictions at the treatment facility.

“Further investigation using rigorous research methodology is warranted to establish the benefit of [platelet-rich plasma] on hemophilic arthropathy and standardized [platelet-rich plasma] preparation and dosing regimens,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grant funding from Tri-Service General Hospital in Taiwan. Three of the authors reported receiving research grants from Shire.

SOURCE: Li TY et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1111/hae.13711.

A single intra-articular injection of platelet-rich plasma showed better pain and function scores at 6 months than did weekly injections of hyaluronic acid in patients with hemophilic arthropathy of the knee.

“In patients with chronic knee joint pain, our study shows that treatment with intra-articular [platelet-rich plasma] injection could reduce pain, improve hyperaemia and enhance knee joint function,” wrote Tsung-Ying Li, MD, of Tri-Service General Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan, and his colleagues. The results of the comparison study were published in Haemophilia.

Researchers conducted a nonrandomized, single-center, open-label comparison study of 22 patients with hemophilia A who had chronic hemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Patients were stratified into two treatment groups using a matched sampling method.

“Patients who could commit to hyaluronic acid treatment were allocated to the hyaluronic acid group, otherwise patients were allocated to the platelet‐rich plasma group,” the researchers wrote.

Participants in the hyaluronic acid arm were given five sequential weekly injections and those in the platelet-rich plasma arm received only a single injection. Outcomes were measured via the visual analogue scale (VAS), the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Chinese Version, and ultrasonography to determine synovial change.

Pain and function scores were significantly lower in patients administered intra-articular platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid at 6 months (P less than .05), the researchers reported. However, comparative analysis found no significant differences at earlier follow-up time points.

“Both treatments were found to be effective in reducing pain and improving functional status of the knee,” the researchers wrote.

They acknowledged a key limitation of the study was the short duration of follow-up, which was due to budget restrictions at the treatment facility.

“Further investigation using rigorous research methodology is warranted to establish the benefit of [platelet-rich plasma] on hemophilic arthropathy and standardized [platelet-rich plasma] preparation and dosing regimens,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grant funding from Tri-Service General Hospital in Taiwan. Three of the authors reported receiving research grants from Shire.

SOURCE: Li TY et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1111/hae.13711.

A single intra-articular injection of platelet-rich plasma showed better pain and function scores at 6 months than did weekly injections of hyaluronic acid in patients with hemophilic arthropathy of the knee.

“In patients with chronic knee joint pain, our study shows that treatment with intra-articular [platelet-rich plasma] injection could reduce pain, improve hyperaemia and enhance knee joint function,” wrote Tsung-Ying Li, MD, of Tri-Service General Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan, and his colleagues. The results of the comparison study were published in Haemophilia.

Researchers conducted a nonrandomized, single-center, open-label comparison study of 22 patients with hemophilia A who had chronic hemophilic arthropathy of the knee. Patients were stratified into two treatment groups using a matched sampling method.

“Patients who could commit to hyaluronic acid treatment were allocated to the hyaluronic acid group, otherwise patients were allocated to the platelet‐rich plasma group,” the researchers wrote.

Participants in the hyaluronic acid arm were given five sequential weekly injections and those in the platelet-rich plasma arm received only a single injection. Outcomes were measured via the visual analogue scale (VAS), the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Chinese Version, and ultrasonography to determine synovial change.

Pain and function scores were significantly lower in patients administered intra-articular platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid at 6 months (P less than .05), the researchers reported. However, comparative analysis found no significant differences at earlier follow-up time points.

“Both treatments were found to be effective in reducing pain and improving functional status of the knee,” the researchers wrote.

They acknowledged a key limitation of the study was the short duration of follow-up, which was due to budget restrictions at the treatment facility.

“Further investigation using rigorous research methodology is warranted to establish the benefit of [platelet-rich plasma] on hemophilic arthropathy and standardized [platelet-rich plasma] preparation and dosing regimens,” they wrote.

The study was supported by grant funding from Tri-Service General Hospital in Taiwan. Three of the authors reported receiving research grants from Shire.

SOURCE: Li TY et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1111/hae.13711.

FROM HAEMOPHILIA

Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

A panel of four biomarkers of cartilage metabolism, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation could help physicians to distinguish between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis, new research suggests.

Such a test for distinguishing between the two conditions, which have “similarities in the distribution of joints involved,” could offer a way to make earlier diagnoses and avoid inappropriate treatment, according to Vinod Chandran, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and Toronto Western Hospital and his colleagues. Dr. Chandran was first author on a study published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases that analyzed serum samples from the University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program and University Health Network Arthritis Program for differences in certain biomarkers from 201 individuals with osteoarthritis, 77 with psoriatic arthritis, and 76 healthy controls.

The samples were tested for 15 biomarkers, including those related to cartilage metabolism (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and hyaluronan), to metabolic syndrome (adiponectin, adipsin, resistin, hepatocyte growth factor, insulin, and leptin), and to inflammation (C-reactive protein, interleukin-1-beta, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor).

Researchers found that levels of 12 of these markers were different in patients with psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, or controls, and 9 markers showed altered expression in psoriatic arthritis, compared with osteoarthritis.

Further analysis showed that levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, resistin, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor were significantly different between patients with psoriatic arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. The ROC curve for a model based on these four biomarkers that also incorporated age and sex had an area under the curve of 0.9984.

Researchers then validated the four biomarkers in an independent set of 75 patients with osteoarthritis and 73 with psoriatic arthritis and found these biomarkers were able to discriminate between the two conditions beyond what would be achieved based on age and sex alone.

The authors noted that previous research has observed high expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and resistin in patients with psoriatic arthritis when compared with those with osteoarthritis.

Nerve growth factor has been seen at elevated levels in the synovial fluid of individuals with osteoarthritis and is known to play a role in the chronic pain associated with that disease.

Similarly, higher cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels are associated with a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis.

However, the authors noted that individuals with osteoarthritis in the study were all undergoing joint replacement surgery and therefore may not be typical of patients presenting to family practices or rheumatology clinics.

The University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program is supported by the Krembil Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chandran V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214737.

A panel of four biomarkers of cartilage metabolism, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation could help physicians to distinguish between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis, new research suggests.

Such a test for distinguishing between the two conditions, which have “similarities in the distribution of joints involved,” could offer a way to make earlier diagnoses and avoid inappropriate treatment, according to Vinod Chandran, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and Toronto Western Hospital and his colleagues. Dr. Chandran was first author on a study published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases that analyzed serum samples from the University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program and University Health Network Arthritis Program for differences in certain biomarkers from 201 individuals with osteoarthritis, 77 with psoriatic arthritis, and 76 healthy controls.

The samples were tested for 15 biomarkers, including those related to cartilage metabolism (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and hyaluronan), to metabolic syndrome (adiponectin, adipsin, resistin, hepatocyte growth factor, insulin, and leptin), and to inflammation (C-reactive protein, interleukin-1-beta, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor).

Researchers found that levels of 12 of these markers were different in patients with psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, or controls, and 9 markers showed altered expression in psoriatic arthritis, compared with osteoarthritis.

Further analysis showed that levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, resistin, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor were significantly different between patients with psoriatic arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. The ROC curve for a model based on these four biomarkers that also incorporated age and sex had an area under the curve of 0.9984.

Researchers then validated the four biomarkers in an independent set of 75 patients with osteoarthritis and 73 with psoriatic arthritis and found these biomarkers were able to discriminate between the two conditions beyond what would be achieved based on age and sex alone.

The authors noted that previous research has observed high expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and resistin in patients with psoriatic arthritis when compared with those with osteoarthritis.

Nerve growth factor has been seen at elevated levels in the synovial fluid of individuals with osteoarthritis and is known to play a role in the chronic pain associated with that disease.

Similarly, higher cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels are associated with a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis.

However, the authors noted that individuals with osteoarthritis in the study were all undergoing joint replacement surgery and therefore may not be typical of patients presenting to family practices or rheumatology clinics.

The University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program is supported by the Krembil Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chandran V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214737.

A panel of four biomarkers of cartilage metabolism, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation could help physicians to distinguish between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis, new research suggests.

Such a test for distinguishing between the two conditions, which have “similarities in the distribution of joints involved,” could offer a way to make earlier diagnoses and avoid inappropriate treatment, according to Vinod Chandran, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and Toronto Western Hospital and his colleagues. Dr. Chandran was first author on a study published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases that analyzed serum samples from the University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program and University Health Network Arthritis Program for differences in certain biomarkers from 201 individuals with osteoarthritis, 77 with psoriatic arthritis, and 76 healthy controls.

The samples were tested for 15 biomarkers, including those related to cartilage metabolism (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and hyaluronan), to metabolic syndrome (adiponectin, adipsin, resistin, hepatocyte growth factor, insulin, and leptin), and to inflammation (C-reactive protein, interleukin-1-beta, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor).

Researchers found that levels of 12 of these markers were different in patients with psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, or controls, and 9 markers showed altered expression in psoriatic arthritis, compared with osteoarthritis.

Further analysis showed that levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, resistin, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor were significantly different between patients with psoriatic arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. The ROC curve for a model based on these four biomarkers that also incorporated age and sex had an area under the curve of 0.9984.

Researchers then validated the four biomarkers in an independent set of 75 patients with osteoarthritis and 73 with psoriatic arthritis and found these biomarkers were able to discriminate between the two conditions beyond what would be achieved based on age and sex alone.

The authors noted that previous research has observed high expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and resistin in patients with psoriatic arthritis when compared with those with osteoarthritis.

Nerve growth factor has been seen at elevated levels in the synovial fluid of individuals with osteoarthritis and is known to play a role in the chronic pain associated with that disease.

Similarly, higher cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels are associated with a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis.

However, the authors noted that individuals with osteoarthritis in the study were all undergoing joint replacement surgery and therefore may not be typical of patients presenting to family practices or rheumatology clinics.

The University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program is supported by the Krembil Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chandran V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214737.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Bariatric surgery may be appropriate for class 1 obesity

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, knee pain and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, knee pain and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, knee pain and chronic back pain.