User login

Ezetimibe-statin combo lowers liver fat in open-label trial

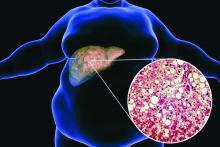

Ezetimibe given in combination with rosuvastatin has a beneficial effect on liver fat in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according results of a randomized, active-controlled trial.

The findings, which come from the investigator-initiated ESSENTIAL trial, are likely to add to the debate over whether or not the lipid-lowering combination could be of benefit beyond its effects in the blood.

“We used magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction [MRI-PDFF], which is highly reliable method of assessing hepatic steatosis,” Youngjoon Kim, PhD, one of the study investigators, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Barcelona.

“It enables accurate, repeatable and reproducible quantitative assessment of liver fat over the entire liver,” observed Dr. Kim, who works at Severance Hospital, part of Yonsei University in Seoul.

He reported that there was a significant 5.8% decrease in liver fat following 24 weeks’ treatment with ezetimibe and rosuvastatin comparing baseline with end of treatment MRI-PDFF values; a drop that was significant (18.2% vs. 12.3%, P < .001).

Rosuvastatin monotherapy also reduced liver fat from 15.0% at baseline to 12.4% after 24 weeks; this drop of 2.6% was also significant (P = .003).

This gave an absolute mean difference between the two study arms of 3.2% (P = .02).

Rationale for the ESSENTIAL study

Dr. Kim observed during his presentation that NAFLD is burgeoning problem around the world. Ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin was a combination treatment already used widely in clinical practice, and there had been some suggestion that ezetimibe might have an effect on liver fat.

“Although the effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis is still controversial, ezetimibe has been reported to reduce visceral fat and improve insulin resistance in several studies” Dr. Kim said.

“Recently, our group reported that the use of ezetimibe affects autophagy of hepatocytes and the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptors containing pyrin domain 3] inflammasome,” he said.

Moreover, he added, “ezetimibe improved NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] in an animal model. However, the effects of ezetimibe have not been clearly shown in a human study.”

Dr. Kim also acknowledged a prior randomized control trial that had looked at the role of ezetimibe in 50 patients with NASH, but had not shown a benefit for the drug over placebo in terms of liver fat reduction.

Addressing the Hawthorne effect

“The size of the effect by that might actually be more modest due to the Hawthorne effect,” said session chair Onno Holleboom, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands.

“What we observe in the large clinical trials is an enormous Hawthorne effect – participating in a NAFLD trial makes people live healthier because they have health checks,” he said.

“That’s a major problem for showing efficacy for the intervention arm,” he added, but of course the open design meant that the trial only had intervention arms; “there was no placebo arm.”

A randomized, active-controlled, clinician-initiated trial

The main objective of the ESSENTIAL trial was therefore to take another look at the potential effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis and doing so in the setting of statin therapy.

In all, 70 patients with NAFLD that had been confirmed via ultrasound were recruited into the prospective, single center, phase 4 trial. Participants were randomized 1:1 to received either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks.

Change in liver fat was measured via MRI-PDFF, taking the average values in each of nine liver segments. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) was also used to measure liver fibrosis, although results did not show any differences either from baseline to end of treatment values in either group or when the two treatment groups were compared.

Dr. Kim reported that both treatment with the ezetimibe-rosuvastatin combination and rosuvastatin monotherapy reduced parameters that might be associated with a negative outcome in NAFLD, such as body mass index and waist circumference, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol. There was also a reduction in C-reactive protein levels in the blood, and interleulin-18. There was no change in liver enzymes.

Several subgroup analyses were performed indicating that “individuals with higher BMI, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, and severe liver fibrosis were likely to be good responders to ezetimibe treatment,” Dr. Kim said.

“These data indicate that ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin is a safe and effective therapeutic option to treat patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia,” he concluded.

The results of the ESSENTIAL study have been published in BMC Medicine.

The study was funded by the Yuhan Corporation. Dr. Kim had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Holleboom was not involved in the study and had no conflicts of interest.

Ezetimibe given in combination with rosuvastatin has a beneficial effect on liver fat in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according results of a randomized, active-controlled trial.

The findings, which come from the investigator-initiated ESSENTIAL trial, are likely to add to the debate over whether or not the lipid-lowering combination could be of benefit beyond its effects in the blood.

“We used magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction [MRI-PDFF], which is highly reliable method of assessing hepatic steatosis,” Youngjoon Kim, PhD, one of the study investigators, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Barcelona.

“It enables accurate, repeatable and reproducible quantitative assessment of liver fat over the entire liver,” observed Dr. Kim, who works at Severance Hospital, part of Yonsei University in Seoul.

He reported that there was a significant 5.8% decrease in liver fat following 24 weeks’ treatment with ezetimibe and rosuvastatin comparing baseline with end of treatment MRI-PDFF values; a drop that was significant (18.2% vs. 12.3%, P < .001).

Rosuvastatin monotherapy also reduced liver fat from 15.0% at baseline to 12.4% after 24 weeks; this drop of 2.6% was also significant (P = .003).

This gave an absolute mean difference between the two study arms of 3.2% (P = .02).

Rationale for the ESSENTIAL study

Dr. Kim observed during his presentation that NAFLD is burgeoning problem around the world. Ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin was a combination treatment already used widely in clinical practice, and there had been some suggestion that ezetimibe might have an effect on liver fat.

“Although the effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis is still controversial, ezetimibe has been reported to reduce visceral fat and improve insulin resistance in several studies” Dr. Kim said.

“Recently, our group reported that the use of ezetimibe affects autophagy of hepatocytes and the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptors containing pyrin domain 3] inflammasome,” he said.

Moreover, he added, “ezetimibe improved NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] in an animal model. However, the effects of ezetimibe have not been clearly shown in a human study.”

Dr. Kim also acknowledged a prior randomized control trial that had looked at the role of ezetimibe in 50 patients with NASH, but had not shown a benefit for the drug over placebo in terms of liver fat reduction.

Addressing the Hawthorne effect

“The size of the effect by that might actually be more modest due to the Hawthorne effect,” said session chair Onno Holleboom, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands.

“What we observe in the large clinical trials is an enormous Hawthorne effect – participating in a NAFLD trial makes people live healthier because they have health checks,” he said.

“That’s a major problem for showing efficacy for the intervention arm,” he added, but of course the open design meant that the trial only had intervention arms; “there was no placebo arm.”

A randomized, active-controlled, clinician-initiated trial

The main objective of the ESSENTIAL trial was therefore to take another look at the potential effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis and doing so in the setting of statin therapy.

In all, 70 patients with NAFLD that had been confirmed via ultrasound were recruited into the prospective, single center, phase 4 trial. Participants were randomized 1:1 to received either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks.

Change in liver fat was measured via MRI-PDFF, taking the average values in each of nine liver segments. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) was also used to measure liver fibrosis, although results did not show any differences either from baseline to end of treatment values in either group or when the two treatment groups were compared.

Dr. Kim reported that both treatment with the ezetimibe-rosuvastatin combination and rosuvastatin monotherapy reduced parameters that might be associated with a negative outcome in NAFLD, such as body mass index and waist circumference, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol. There was also a reduction in C-reactive protein levels in the blood, and interleulin-18. There was no change in liver enzymes.

Several subgroup analyses were performed indicating that “individuals with higher BMI, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, and severe liver fibrosis were likely to be good responders to ezetimibe treatment,” Dr. Kim said.

“These data indicate that ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin is a safe and effective therapeutic option to treat patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia,” he concluded.

The results of the ESSENTIAL study have been published in BMC Medicine.

The study was funded by the Yuhan Corporation. Dr. Kim had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Holleboom was not involved in the study and had no conflicts of interest.

Ezetimibe given in combination with rosuvastatin has a beneficial effect on liver fat in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according results of a randomized, active-controlled trial.

The findings, which come from the investigator-initiated ESSENTIAL trial, are likely to add to the debate over whether or not the lipid-lowering combination could be of benefit beyond its effects in the blood.

“We used magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction [MRI-PDFF], which is highly reliable method of assessing hepatic steatosis,” Youngjoon Kim, PhD, one of the study investigators, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Barcelona.

“It enables accurate, repeatable and reproducible quantitative assessment of liver fat over the entire liver,” observed Dr. Kim, who works at Severance Hospital, part of Yonsei University in Seoul.

He reported that there was a significant 5.8% decrease in liver fat following 24 weeks’ treatment with ezetimibe and rosuvastatin comparing baseline with end of treatment MRI-PDFF values; a drop that was significant (18.2% vs. 12.3%, P < .001).

Rosuvastatin monotherapy also reduced liver fat from 15.0% at baseline to 12.4% after 24 weeks; this drop of 2.6% was also significant (P = .003).

This gave an absolute mean difference between the two study arms of 3.2% (P = .02).

Rationale for the ESSENTIAL study

Dr. Kim observed during his presentation that NAFLD is burgeoning problem around the world. Ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin was a combination treatment already used widely in clinical practice, and there had been some suggestion that ezetimibe might have an effect on liver fat.

“Although the effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis is still controversial, ezetimibe has been reported to reduce visceral fat and improve insulin resistance in several studies” Dr. Kim said.

“Recently, our group reported that the use of ezetimibe affects autophagy of hepatocytes and the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptors containing pyrin domain 3] inflammasome,” he said.

Moreover, he added, “ezetimibe improved NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] in an animal model. However, the effects of ezetimibe have not been clearly shown in a human study.”

Dr. Kim also acknowledged a prior randomized control trial that had looked at the role of ezetimibe in 50 patients with NASH, but had not shown a benefit for the drug over placebo in terms of liver fat reduction.

Addressing the Hawthorne effect

“The size of the effect by that might actually be more modest due to the Hawthorne effect,” said session chair Onno Holleboom, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands.

“What we observe in the large clinical trials is an enormous Hawthorne effect – participating in a NAFLD trial makes people live healthier because they have health checks,” he said.

“That’s a major problem for showing efficacy for the intervention arm,” he added, but of course the open design meant that the trial only had intervention arms; “there was no placebo arm.”

A randomized, active-controlled, clinician-initiated trial

The main objective of the ESSENTIAL trial was therefore to take another look at the potential effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis and doing so in the setting of statin therapy.

In all, 70 patients with NAFLD that had been confirmed via ultrasound were recruited into the prospective, single center, phase 4 trial. Participants were randomized 1:1 to received either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks.

Change in liver fat was measured via MRI-PDFF, taking the average values in each of nine liver segments. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) was also used to measure liver fibrosis, although results did not show any differences either from baseline to end of treatment values in either group or when the two treatment groups were compared.

Dr. Kim reported that both treatment with the ezetimibe-rosuvastatin combination and rosuvastatin monotherapy reduced parameters that might be associated with a negative outcome in NAFLD, such as body mass index and waist circumference, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol. There was also a reduction in C-reactive protein levels in the blood, and interleulin-18. There was no change in liver enzymes.

Several subgroup analyses were performed indicating that “individuals with higher BMI, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, and severe liver fibrosis were likely to be good responders to ezetimibe treatment,” Dr. Kim said.

“These data indicate that ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin is a safe and effective therapeutic option to treat patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia,” he concluded.

The results of the ESSENTIAL study have been published in BMC Medicine.

The study was funded by the Yuhan Corporation. Dr. Kim had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Holleboom was not involved in the study and had no conflicts of interest.

FROM EASD 2022

Aspirin primary prevention benefit in those with raised Lp(a)?

Aspirin may be of specific benefit for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in individuals with raised Lp(a) levels, a new study has suggested.

The study analyzed data from the ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial, which randomized 19,000 individuals aged 70 years or older without a history of cardiovascular disease to aspirin (100 mg/day) or placebo. While the main results, reported previously, showed no net benefit of aspirin in the overall population, the current analysis suggests there may be a benefit in individuals with raised Lp(a) levels.

The current analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Our study provides evidence that aspirin may specifically benefit older individuals with genotypes for elevated plasma Lp(a) in the setting of high-risk primary prevention of cardiovascular events and that overall benefit may outweigh harm related to major bleeding,” the authors, led by Paul Lacaze, PhD, Monash University, Melbourne, conclude.

They also point out that similar observations have been previously seen in another large aspirin primary prevention study conducted in younger women, the Women’s Health Study, and the current analysis provides validation of those findings.

“Our results provide new evidence to support the potential use of aspirin to target individuals with elevated Lp(a) for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” the researchers say.

They acknowledge that these results would be strengthened by the use of directly measured plasma Lp(a) levels, in addition to Lp(a) genotypes.

But they add: “Nonetheless, given the lack of any currently approved therapies for targeting elevated Lp(a), our findings may have widespread clinical implications, adding evidence to the rationale that aspirin may be a viable option for reducing Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular risk.”

Dr. Lacaze and colleagues explain that elevated plasma Lp(a) levels confer up to fourfold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, with around 20%-30% of the general population affected. Despite the high burden and prevalence of elevated plasma Lp(a), there are currently no approved pharmacologic therapies targeting this lipoprotein. Although promising candidates are in development for the secondary prevention of Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular disease, it will be many years before these candidates are assessed for primary prevention.

For the current study, researchers analyzed data from 12,815 ASPREE participants who had undergone genotyping and compared outcomes with aspirin versus placebo in those with and without genotypes associated with elevated Lp(a) levels.

Results showed that individuals with elevated Lp(a)-associated genotypes, defined in two different ways, showed a reduction in ischemic events with aspirin versus placebo, and this benefit was not outweighed by an increased bleeding risk.

Specifically, in the placebo group, individuals who carried the rs3798220-C allele, which is known to be associated with raised Lp(a) levels, making up 3.2% of the genotyped population in the study, had an almost twofold increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events than those not carrying this genotype. However, the risk was attenuated in the aspirin group, with carriers of the rs3798220-C allele actually having a lower rate of cardiovascular events than noncarriers.

In addition, rs3798220-C carrier status was not significantly associated with increased risk of clinically significant bleeding events in the aspirin group.

Similar results were seen with the second way of identifying patients with a high risk of elevated Lp(a) levels using a 43-variant genetic risk score (LPA-GRS).

In the whole study population, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years and increased clinically significant bleeding events by 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years, suggesting parity between overall benefit versus harm.

However, in the rs3798220-C subgroup, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 11.4 events per 1,000 person-years (a more than sixfold higher magnitude of cardiovascular disease risk reduction than in the overall cohort), with a bleeding risk of 3.3 events per 1,000 person-years, the researchers report.

“Hence in rs3798220-C carriers, aspirin appeared to have a net benefit of 8.1 events per 1,000 person-years,” they state.

In the highest LPA-GRS quintile, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 3.3 events per 1,000 person-years (approximately twofold higher magnitude of risk reduction, compared with the overall cohort), with an increase in bleeding risk of 1.6 events per 1,000 person-years (almost identical bleeding risk to the overall cohort). This shifted the benefit versus harm balance in the highest LPA-GRS quintile to a net benefit of 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years.

Similar findings in the Women’s Health Study

Dr. Lacaze and colleagues point out that similar results have also been seen in another large aspirin primary prevention study – the Women’s Health Study (WHS).

The WHS compared aspirin 100 mg every other day with placebo in initially healthy younger women. Previously reported results showed that women carrying the rs3798220-C variant, associated with highly elevated Lp(a) levels, had a twofold higher risk of cardiovascular events than noncarrier women in the placebo group, but this risk was reduced in the aspirin group. And there was no increased risk of bleeding in women with elevated Lp(a).

“These results, in the absence of any other randomized controlled trial evidence or approved therapy for treating Lp(a)-associated risk, have been used by some physicians as justification for prescribing aspirin in patients with elevated Lp(a),” Dr. Lacaze and colleagues note.

“In the present study of the ASPREE trial population, our results were consistent with the WHS analysis, despite randomizing older individuals (both men and women),” they add.

They say this validation of the WHS result provides evidence that a very high-risk subgroup of individuals with highly elevated Lp(a) – those carrying the rs3798220-C allele – may benefit from low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events. Further, the benefits in this subgroup specifically may outweigh any bleeding risk.

But they point out that rs3798220-C carriers comprise only a small portion of all individuals with elevated Lp(a) in the general population, while the polygenic LPA-GRS explains about 60% of the variation in directly measured plasma Lp(a) levels and has the potential advantage of being able to identify a larger group of individuals at increased risk.

The researchers note, however, that it is not clear to what extent the LPA-GRS results add further evidence to suggest that individuals with elevated Lp(a), beyond rs3798220-C carriers, may be more likely to benefit from aspirin.

“If the benefit of aspirin extends beyond very high-risk rs3798220-C carriers alone, to the broader 20%-30% of individuals with elevated Lp(a), the potential utility of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events would increase substantially,” they say.

‘Very high clinical relevance’

In an accompanying editorial, Ana Devesa, MD, Borja Ibanez, MD, PhD, and Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, The National Center for Cardiovascular Research, Madrid, say that: “[Dr.] Lacaze et al. are to be congratulated for a study of very high clinical relevance that represents a first indication for primary prevention for patients at high cardiovascular risk.”

They explain that the pathogenic mechanism of Lp(a) is believed to be a combination of prothrombotic and proatherogenic effects, and the current findings support the hypothesis that the prothrombotic mechanism of Lp(a) is mediated by platelet aggregation.

This would explain the occurrence of thrombotic events in the presence of atherosclerosis in that elevated Lp(a) levels may induce platelet adhesion and aggregation to the activated atherosclerotic plaque, thus enhancing the atherothrombotic process. Moreover, activated platelets release several mediators that result in cell adhesion and attraction of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines, driving an inflammatory response and mediating atherosclerosis progression, they add.

The editorialists highlight the limitations of the study already acknowledged by the authors: The analysis used genotypes rather than elevated Lp(a) levels and included only those of European ancestry, meaning the results are difficult to extrapolate to other populations.

“The next steps in clinical practice should be defined, and there are still questions to be answered,” they conclude. “Will every patient benefit from antithrombotic therapies? Should all patients who have elevated Lp(a) levels be treated with aspirin?”

The ASPREE Biobank is supported by grants from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Monash University, Menzies Research Institute, Australian National University, University of Melbourne, National Institutes of Health, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Dr. Lacaze is supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin may be of specific benefit for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in individuals with raised Lp(a) levels, a new study has suggested.

The study analyzed data from the ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial, which randomized 19,000 individuals aged 70 years or older without a history of cardiovascular disease to aspirin (100 mg/day) or placebo. While the main results, reported previously, showed no net benefit of aspirin in the overall population, the current analysis suggests there may be a benefit in individuals with raised Lp(a) levels.

The current analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Our study provides evidence that aspirin may specifically benefit older individuals with genotypes for elevated plasma Lp(a) in the setting of high-risk primary prevention of cardiovascular events and that overall benefit may outweigh harm related to major bleeding,” the authors, led by Paul Lacaze, PhD, Monash University, Melbourne, conclude.

They also point out that similar observations have been previously seen in another large aspirin primary prevention study conducted in younger women, the Women’s Health Study, and the current analysis provides validation of those findings.

“Our results provide new evidence to support the potential use of aspirin to target individuals with elevated Lp(a) for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” the researchers say.

They acknowledge that these results would be strengthened by the use of directly measured plasma Lp(a) levels, in addition to Lp(a) genotypes.

But they add: “Nonetheless, given the lack of any currently approved therapies for targeting elevated Lp(a), our findings may have widespread clinical implications, adding evidence to the rationale that aspirin may be a viable option for reducing Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular risk.”

Dr. Lacaze and colleagues explain that elevated plasma Lp(a) levels confer up to fourfold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, with around 20%-30% of the general population affected. Despite the high burden and prevalence of elevated plasma Lp(a), there are currently no approved pharmacologic therapies targeting this lipoprotein. Although promising candidates are in development for the secondary prevention of Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular disease, it will be many years before these candidates are assessed for primary prevention.

For the current study, researchers analyzed data from 12,815 ASPREE participants who had undergone genotyping and compared outcomes with aspirin versus placebo in those with and without genotypes associated with elevated Lp(a) levels.

Results showed that individuals with elevated Lp(a)-associated genotypes, defined in two different ways, showed a reduction in ischemic events with aspirin versus placebo, and this benefit was not outweighed by an increased bleeding risk.

Specifically, in the placebo group, individuals who carried the rs3798220-C allele, which is known to be associated with raised Lp(a) levels, making up 3.2% of the genotyped population in the study, had an almost twofold increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events than those not carrying this genotype. However, the risk was attenuated in the aspirin group, with carriers of the rs3798220-C allele actually having a lower rate of cardiovascular events than noncarriers.

In addition, rs3798220-C carrier status was not significantly associated with increased risk of clinically significant bleeding events in the aspirin group.

Similar results were seen with the second way of identifying patients with a high risk of elevated Lp(a) levels using a 43-variant genetic risk score (LPA-GRS).

In the whole study population, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years and increased clinically significant bleeding events by 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years, suggesting parity between overall benefit versus harm.

However, in the rs3798220-C subgroup, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 11.4 events per 1,000 person-years (a more than sixfold higher magnitude of cardiovascular disease risk reduction than in the overall cohort), with a bleeding risk of 3.3 events per 1,000 person-years, the researchers report.

“Hence in rs3798220-C carriers, aspirin appeared to have a net benefit of 8.1 events per 1,000 person-years,” they state.

In the highest LPA-GRS quintile, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 3.3 events per 1,000 person-years (approximately twofold higher magnitude of risk reduction, compared with the overall cohort), with an increase in bleeding risk of 1.6 events per 1,000 person-years (almost identical bleeding risk to the overall cohort). This shifted the benefit versus harm balance in the highest LPA-GRS quintile to a net benefit of 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years.

Similar findings in the Women’s Health Study

Dr. Lacaze and colleagues point out that similar results have also been seen in another large aspirin primary prevention study – the Women’s Health Study (WHS).

The WHS compared aspirin 100 mg every other day with placebo in initially healthy younger women. Previously reported results showed that women carrying the rs3798220-C variant, associated with highly elevated Lp(a) levels, had a twofold higher risk of cardiovascular events than noncarrier women in the placebo group, but this risk was reduced in the aspirin group. And there was no increased risk of bleeding in women with elevated Lp(a).

“These results, in the absence of any other randomized controlled trial evidence or approved therapy for treating Lp(a)-associated risk, have been used by some physicians as justification for prescribing aspirin in patients with elevated Lp(a),” Dr. Lacaze and colleagues note.

“In the present study of the ASPREE trial population, our results were consistent with the WHS analysis, despite randomizing older individuals (both men and women),” they add.

They say this validation of the WHS result provides evidence that a very high-risk subgroup of individuals with highly elevated Lp(a) – those carrying the rs3798220-C allele – may benefit from low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events. Further, the benefits in this subgroup specifically may outweigh any bleeding risk.

But they point out that rs3798220-C carriers comprise only a small portion of all individuals with elevated Lp(a) in the general population, while the polygenic LPA-GRS explains about 60% of the variation in directly measured plasma Lp(a) levels and has the potential advantage of being able to identify a larger group of individuals at increased risk.

The researchers note, however, that it is not clear to what extent the LPA-GRS results add further evidence to suggest that individuals with elevated Lp(a), beyond rs3798220-C carriers, may be more likely to benefit from aspirin.

“If the benefit of aspirin extends beyond very high-risk rs3798220-C carriers alone, to the broader 20%-30% of individuals with elevated Lp(a), the potential utility of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events would increase substantially,” they say.

‘Very high clinical relevance’

In an accompanying editorial, Ana Devesa, MD, Borja Ibanez, MD, PhD, and Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, The National Center for Cardiovascular Research, Madrid, say that: “[Dr.] Lacaze et al. are to be congratulated for a study of very high clinical relevance that represents a first indication for primary prevention for patients at high cardiovascular risk.”

They explain that the pathogenic mechanism of Lp(a) is believed to be a combination of prothrombotic and proatherogenic effects, and the current findings support the hypothesis that the prothrombotic mechanism of Lp(a) is mediated by platelet aggregation.

This would explain the occurrence of thrombotic events in the presence of atherosclerosis in that elevated Lp(a) levels may induce platelet adhesion and aggregation to the activated atherosclerotic plaque, thus enhancing the atherothrombotic process. Moreover, activated platelets release several mediators that result in cell adhesion and attraction of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines, driving an inflammatory response and mediating atherosclerosis progression, they add.

The editorialists highlight the limitations of the study already acknowledged by the authors: The analysis used genotypes rather than elevated Lp(a) levels and included only those of European ancestry, meaning the results are difficult to extrapolate to other populations.

“The next steps in clinical practice should be defined, and there are still questions to be answered,” they conclude. “Will every patient benefit from antithrombotic therapies? Should all patients who have elevated Lp(a) levels be treated with aspirin?”

The ASPREE Biobank is supported by grants from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Monash University, Menzies Research Institute, Australian National University, University of Melbourne, National Institutes of Health, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Dr. Lacaze is supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin may be of specific benefit for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in individuals with raised Lp(a) levels, a new study has suggested.

The study analyzed data from the ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial, which randomized 19,000 individuals aged 70 years or older without a history of cardiovascular disease to aspirin (100 mg/day) or placebo. While the main results, reported previously, showed no net benefit of aspirin in the overall population, the current analysis suggests there may be a benefit in individuals with raised Lp(a) levels.

The current analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Our study provides evidence that aspirin may specifically benefit older individuals with genotypes for elevated plasma Lp(a) in the setting of high-risk primary prevention of cardiovascular events and that overall benefit may outweigh harm related to major bleeding,” the authors, led by Paul Lacaze, PhD, Monash University, Melbourne, conclude.

They also point out that similar observations have been previously seen in another large aspirin primary prevention study conducted in younger women, the Women’s Health Study, and the current analysis provides validation of those findings.

“Our results provide new evidence to support the potential use of aspirin to target individuals with elevated Lp(a) for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” the researchers say.

They acknowledge that these results would be strengthened by the use of directly measured plasma Lp(a) levels, in addition to Lp(a) genotypes.

But they add: “Nonetheless, given the lack of any currently approved therapies for targeting elevated Lp(a), our findings may have widespread clinical implications, adding evidence to the rationale that aspirin may be a viable option for reducing Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular risk.”

Dr. Lacaze and colleagues explain that elevated plasma Lp(a) levels confer up to fourfold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, with around 20%-30% of the general population affected. Despite the high burden and prevalence of elevated plasma Lp(a), there are currently no approved pharmacologic therapies targeting this lipoprotein. Although promising candidates are in development for the secondary prevention of Lp(a)-mediated cardiovascular disease, it will be many years before these candidates are assessed for primary prevention.

For the current study, researchers analyzed data from 12,815 ASPREE participants who had undergone genotyping and compared outcomes with aspirin versus placebo in those with and without genotypes associated with elevated Lp(a) levels.

Results showed that individuals with elevated Lp(a)-associated genotypes, defined in two different ways, showed a reduction in ischemic events with aspirin versus placebo, and this benefit was not outweighed by an increased bleeding risk.

Specifically, in the placebo group, individuals who carried the rs3798220-C allele, which is known to be associated with raised Lp(a) levels, making up 3.2% of the genotyped population in the study, had an almost twofold increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events than those not carrying this genotype. However, the risk was attenuated in the aspirin group, with carriers of the rs3798220-C allele actually having a lower rate of cardiovascular events than noncarriers.

In addition, rs3798220-C carrier status was not significantly associated with increased risk of clinically significant bleeding events in the aspirin group.

Similar results were seen with the second way of identifying patients with a high risk of elevated Lp(a) levels using a 43-variant genetic risk score (LPA-GRS).

In the whole study population, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years and increased clinically significant bleeding events by 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years, suggesting parity between overall benefit versus harm.

However, in the rs3798220-C subgroup, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 11.4 events per 1,000 person-years (a more than sixfold higher magnitude of cardiovascular disease risk reduction than in the overall cohort), with a bleeding risk of 3.3 events per 1,000 person-years, the researchers report.

“Hence in rs3798220-C carriers, aspirin appeared to have a net benefit of 8.1 events per 1,000 person-years,” they state.

In the highest LPA-GRS quintile, aspirin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 3.3 events per 1,000 person-years (approximately twofold higher magnitude of risk reduction, compared with the overall cohort), with an increase in bleeding risk of 1.6 events per 1,000 person-years (almost identical bleeding risk to the overall cohort). This shifted the benefit versus harm balance in the highest LPA-GRS quintile to a net benefit of 1.7 events per 1,000 person-years.

Similar findings in the Women’s Health Study

Dr. Lacaze and colleagues point out that similar results have also been seen in another large aspirin primary prevention study – the Women’s Health Study (WHS).

The WHS compared aspirin 100 mg every other day with placebo in initially healthy younger women. Previously reported results showed that women carrying the rs3798220-C variant, associated with highly elevated Lp(a) levels, had a twofold higher risk of cardiovascular events than noncarrier women in the placebo group, but this risk was reduced in the aspirin group. And there was no increased risk of bleeding in women with elevated Lp(a).

“These results, in the absence of any other randomized controlled trial evidence or approved therapy for treating Lp(a)-associated risk, have been used by some physicians as justification for prescribing aspirin in patients with elevated Lp(a),” Dr. Lacaze and colleagues note.

“In the present study of the ASPREE trial population, our results were consistent with the WHS analysis, despite randomizing older individuals (both men and women),” they add.

They say this validation of the WHS result provides evidence that a very high-risk subgroup of individuals with highly elevated Lp(a) – those carrying the rs3798220-C allele – may benefit from low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events. Further, the benefits in this subgroup specifically may outweigh any bleeding risk.

But they point out that rs3798220-C carriers comprise only a small portion of all individuals with elevated Lp(a) in the general population, while the polygenic LPA-GRS explains about 60% of the variation in directly measured plasma Lp(a) levels and has the potential advantage of being able to identify a larger group of individuals at increased risk.

The researchers note, however, that it is not clear to what extent the LPA-GRS results add further evidence to suggest that individuals with elevated Lp(a), beyond rs3798220-C carriers, may be more likely to benefit from aspirin.

“If the benefit of aspirin extends beyond very high-risk rs3798220-C carriers alone, to the broader 20%-30% of individuals with elevated Lp(a), the potential utility of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events would increase substantially,” they say.

‘Very high clinical relevance’

In an accompanying editorial, Ana Devesa, MD, Borja Ibanez, MD, PhD, and Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, The National Center for Cardiovascular Research, Madrid, say that: “[Dr.] Lacaze et al. are to be congratulated for a study of very high clinical relevance that represents a first indication for primary prevention for patients at high cardiovascular risk.”

They explain that the pathogenic mechanism of Lp(a) is believed to be a combination of prothrombotic and proatherogenic effects, and the current findings support the hypothesis that the prothrombotic mechanism of Lp(a) is mediated by platelet aggregation.

This would explain the occurrence of thrombotic events in the presence of atherosclerosis in that elevated Lp(a) levels may induce platelet adhesion and aggregation to the activated atherosclerotic plaque, thus enhancing the atherothrombotic process. Moreover, activated platelets release several mediators that result in cell adhesion and attraction of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines, driving an inflammatory response and mediating atherosclerosis progression, they add.

The editorialists highlight the limitations of the study already acknowledged by the authors: The analysis used genotypes rather than elevated Lp(a) levels and included only those of European ancestry, meaning the results are difficult to extrapolate to other populations.

“The next steps in clinical practice should be defined, and there are still questions to be answered,” they conclude. “Will every patient benefit from antithrombotic therapies? Should all patients who have elevated Lp(a) levels be treated with aspirin?”

The ASPREE Biobank is supported by grants from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Monash University, Menzies Research Institute, Australian National University, University of Melbourne, National Institutes of Health, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Dr. Lacaze is supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Coffee linked to reduced cardiovascular disease and mortality risk

Drinking two to three daily cups of – ground, instant, or decaffeinated – is associated with significant reductions in new cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality risk, compared with avoiding coffee, a new analysis of the prospective UK Biobank suggests.

Ground and instant coffee, but not decaffeinated coffee, also was associated with reduced risk of new-onset arrhythmia, including atrial fibrillation.

“Our study is the first to look at differences in coffee subtypes to tease out important differences which may explain some of the mechanisms through which coffee works,” Peter M. Kistler, MD, of the Alfred Hospital and Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Australia, told this news organization.

“Daily coffee intake should not be discouraged by physicians but rather considered part of a healthy diet,” Dr. Kistler said.

“This study supports that coffee is safe and even potentially beneficial, which is consistent with most of the prior evidence,” Carl “Chip” Lavie, MD, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“We do not prescribe coffee to patients, but for the majority who like coffee, they can be encouraged it is fine to take a few cups daily,” said Dr. Lavie, with the Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans.

The study was published online in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

Clear cardiovascular benefits

A total of 449,563 UK Biobank participants (median age 58 years; 55% women), who were free of arrhythmias or other CVD at baseline, reported in questionnaires their level of daily coffee intake and preferred type of coffee.

During more than 12.5 years of follow-up, 27,809 participants (6.2%) died.

Drinking one to five cups per day of ground or instant coffee (but not decaffeinated coffee) was associated with a significant reduction in incident arrhythmia. The lowest risk was with four to five cups per day for ground coffee (hazard ratio [HR] 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76-0.91; P < .0001) and two to three cups per day for instant coffee (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.85-0.92; P < .0001).

Habitual coffee drinking of up to five cups perday was also associated with significant reductions in the risk of incident CVD, when compared with nondrinkers.

Significant reductions in the risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) were associated with habitual coffee intake of up to five cups per day, with the lowest risk for CHD observed in those who consumed two to three cups per day (HR 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86-0.91; P < .0001).

Coffee consumption at all levels was linked to significant reduction in the risk of congestive cardiac failure (CCF) and ischemic stroke. The lowest risks were observed in those who consumed two to three cups per day, with HR, 0.83 (95% CI, 0.79-0.87; P < .0001) for CCF and HR, 0.84 (95% CI, 0.78-0.90; P < .0001) for ischemic stroke.

Death from any cause was significantly reduced for all coffee subtypes, with the greatest risk reduction seen with two to three cups per day for decaffeinated (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.81-0.91; P < .0001); ground (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.69-0.78; P < .0001); and instant coffee (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86-0.93; P < .0001).

“Coffee consumption is associated with cardiovascular benefits and should not empirically be discontinued in those with underlying heart rhythm disorders or cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Kistler told this news organization.

Plausible mechanisms

There are a number of proposed mechanisms to explain the benefits of coffee on CVD.

“Caffeine has antiarrhythmic properties through adenosine A1 and A2A receptor inhibition, hence the difference in effects of decaf vs. full-strength coffee on heart rhythm disorders,” Dr. Kistler explained.

Coffee has vasodilatory effects and coffee also contains antioxidant polyphenols, which reduce oxidative stress and modulate metabolism.

“The explanation for improved survival with habitual coffee consumption remains unclear,” Dr. Kistler said.

“Putative mechanisms include improved endothelial function, circulating antioxidants, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced inflammation. Another potential mechanism includes the beneficial effects of coffee on metabolic syndrome,” he said.

“Caffeine has a role in weight loss through inhibition of gut fatty acid absorption and increase in basal metabolic rate. Furthermore, coffee has been associated with a significantly lower incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” Dr. Kistler added.

Direction of relationship unclear

Charlotte Mills, PhD, University of Reading, England, said this study “adds to the body of evidence from observational trials associating moderate coffee consumption with cardioprotection, which looks promising.”

However, with the observational design, it’s unclear “which direction the relationship goes – for example, does coffee make you healthy or do inherently healthier people consume coffee? Randomized controlled trials are needed to fully understand the relationship between coffee and health before recommendations can be made,” Dr. Mills told the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre.

Annette Creedon, PhD, nutrition scientist with the British Nutrition Foundation, said it’s possible that respondents over- or underestimated the amount of coffee that they were consuming at the start of the study when they self-reported their intake.

“It is therefore difficult to determine whether the outcomes can be directly associated with the behaviors in coffee consumption reported at the start of the study,” she told the Science Media Centre.

The study had no funding. Dr. Kistler has received funding from Abbott Medical for consultancy and speaking engagements and fellowship support from Biosense Webster. Dr. Lavie has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Mills has worked in collaboration with Nestle on research relating to coffee and health funded by UKRI. Dr. Creedon has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Drinking two to three daily cups of – ground, instant, or decaffeinated – is associated with significant reductions in new cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality risk, compared with avoiding coffee, a new analysis of the prospective UK Biobank suggests.

Ground and instant coffee, but not decaffeinated coffee, also was associated with reduced risk of new-onset arrhythmia, including atrial fibrillation.

“Our study is the first to look at differences in coffee subtypes to tease out important differences which may explain some of the mechanisms through which coffee works,” Peter M. Kistler, MD, of the Alfred Hospital and Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Australia, told this news organization.

“Daily coffee intake should not be discouraged by physicians but rather considered part of a healthy diet,” Dr. Kistler said.

“This study supports that coffee is safe and even potentially beneficial, which is consistent with most of the prior evidence,” Carl “Chip” Lavie, MD, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“We do not prescribe coffee to patients, but for the majority who like coffee, they can be encouraged it is fine to take a few cups daily,” said Dr. Lavie, with the Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans.

The study was published online in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

Clear cardiovascular benefits

A total of 449,563 UK Biobank participants (median age 58 years; 55% women), who were free of arrhythmias or other CVD at baseline, reported in questionnaires their level of daily coffee intake and preferred type of coffee.

During more than 12.5 years of follow-up, 27,809 participants (6.2%) died.

Drinking one to five cups per day of ground or instant coffee (but not decaffeinated coffee) was associated with a significant reduction in incident arrhythmia. The lowest risk was with four to five cups per day for ground coffee (hazard ratio [HR] 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76-0.91; P < .0001) and two to three cups per day for instant coffee (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.85-0.92; P < .0001).

Habitual coffee drinking of up to five cups perday was also associated with significant reductions in the risk of incident CVD, when compared with nondrinkers.

Significant reductions in the risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) were associated with habitual coffee intake of up to five cups per day, with the lowest risk for CHD observed in those who consumed two to three cups per day (HR 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86-0.91; P < .0001).

Coffee consumption at all levels was linked to significant reduction in the risk of congestive cardiac failure (CCF) and ischemic stroke. The lowest risks were observed in those who consumed two to three cups per day, with HR, 0.83 (95% CI, 0.79-0.87; P < .0001) for CCF and HR, 0.84 (95% CI, 0.78-0.90; P < .0001) for ischemic stroke.

Death from any cause was significantly reduced for all coffee subtypes, with the greatest risk reduction seen with two to three cups per day for decaffeinated (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.81-0.91; P < .0001); ground (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.69-0.78; P < .0001); and instant coffee (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86-0.93; P < .0001).

“Coffee consumption is associated with cardiovascular benefits and should not empirically be discontinued in those with underlying heart rhythm disorders or cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Kistler told this news organization.

Plausible mechanisms

There are a number of proposed mechanisms to explain the benefits of coffee on CVD.

“Caffeine has antiarrhythmic properties through adenosine A1 and A2A receptor inhibition, hence the difference in effects of decaf vs. full-strength coffee on heart rhythm disorders,” Dr. Kistler explained.

Coffee has vasodilatory effects and coffee also contains antioxidant polyphenols, which reduce oxidative stress and modulate metabolism.

“The explanation for improved survival with habitual coffee consumption remains unclear,” Dr. Kistler said.

“Putative mechanisms include improved endothelial function, circulating antioxidants, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced inflammation. Another potential mechanism includes the beneficial effects of coffee on metabolic syndrome,” he said.

“Caffeine has a role in weight loss through inhibition of gut fatty acid absorption and increase in basal metabolic rate. Furthermore, coffee has been associated with a significantly lower incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” Dr. Kistler added.

Direction of relationship unclear

Charlotte Mills, PhD, University of Reading, England, said this study “adds to the body of evidence from observational trials associating moderate coffee consumption with cardioprotection, which looks promising.”

However, with the observational design, it’s unclear “which direction the relationship goes – for example, does coffee make you healthy or do inherently healthier people consume coffee? Randomized controlled trials are needed to fully understand the relationship between coffee and health before recommendations can be made,” Dr. Mills told the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre.

Annette Creedon, PhD, nutrition scientist with the British Nutrition Foundation, said it’s possible that respondents over- or underestimated the amount of coffee that they were consuming at the start of the study when they self-reported their intake.

“It is therefore difficult to determine whether the outcomes can be directly associated with the behaviors in coffee consumption reported at the start of the study,” she told the Science Media Centre.

The study had no funding. Dr. Kistler has received funding from Abbott Medical for consultancy and speaking engagements and fellowship support from Biosense Webster. Dr. Lavie has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Mills has worked in collaboration with Nestle on research relating to coffee and health funded by UKRI. Dr. Creedon has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Drinking two to three daily cups of – ground, instant, or decaffeinated – is associated with significant reductions in new cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality risk, compared with avoiding coffee, a new analysis of the prospective UK Biobank suggests.

Ground and instant coffee, but not decaffeinated coffee, also was associated with reduced risk of new-onset arrhythmia, including atrial fibrillation.

“Our study is the first to look at differences in coffee subtypes to tease out important differences which may explain some of the mechanisms through which coffee works,” Peter M. Kistler, MD, of the Alfred Hospital and Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Australia, told this news organization.

“Daily coffee intake should not be discouraged by physicians but rather considered part of a healthy diet,” Dr. Kistler said.

“This study supports that coffee is safe and even potentially beneficial, which is consistent with most of the prior evidence,” Carl “Chip” Lavie, MD, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“We do not prescribe coffee to patients, but for the majority who like coffee, they can be encouraged it is fine to take a few cups daily,” said Dr. Lavie, with the Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans.

The study was published online in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

Clear cardiovascular benefits

A total of 449,563 UK Biobank participants (median age 58 years; 55% women), who were free of arrhythmias or other CVD at baseline, reported in questionnaires their level of daily coffee intake and preferred type of coffee.

During more than 12.5 years of follow-up, 27,809 participants (6.2%) died.

Drinking one to five cups per day of ground or instant coffee (but not decaffeinated coffee) was associated with a significant reduction in incident arrhythmia. The lowest risk was with four to five cups per day for ground coffee (hazard ratio [HR] 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76-0.91; P < .0001) and two to three cups per day for instant coffee (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.85-0.92; P < .0001).

Habitual coffee drinking of up to five cups perday was also associated with significant reductions in the risk of incident CVD, when compared with nondrinkers.

Significant reductions in the risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) were associated with habitual coffee intake of up to five cups per day, with the lowest risk for CHD observed in those who consumed two to three cups per day (HR 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86-0.91; P < .0001).

Coffee consumption at all levels was linked to significant reduction in the risk of congestive cardiac failure (CCF) and ischemic stroke. The lowest risks were observed in those who consumed two to three cups per day, with HR, 0.83 (95% CI, 0.79-0.87; P < .0001) for CCF and HR, 0.84 (95% CI, 0.78-0.90; P < .0001) for ischemic stroke.

Death from any cause was significantly reduced for all coffee subtypes, with the greatest risk reduction seen with two to three cups per day for decaffeinated (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.81-0.91; P < .0001); ground (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.69-0.78; P < .0001); and instant coffee (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86-0.93; P < .0001).

“Coffee consumption is associated with cardiovascular benefits and should not empirically be discontinued in those with underlying heart rhythm disorders or cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Kistler told this news organization.

Plausible mechanisms

There are a number of proposed mechanisms to explain the benefits of coffee on CVD.

“Caffeine has antiarrhythmic properties through adenosine A1 and A2A receptor inhibition, hence the difference in effects of decaf vs. full-strength coffee on heart rhythm disorders,” Dr. Kistler explained.

Coffee has vasodilatory effects and coffee also contains antioxidant polyphenols, which reduce oxidative stress and modulate metabolism.

“The explanation for improved survival with habitual coffee consumption remains unclear,” Dr. Kistler said.

“Putative mechanisms include improved endothelial function, circulating antioxidants, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced inflammation. Another potential mechanism includes the beneficial effects of coffee on metabolic syndrome,” he said.

“Caffeine has a role in weight loss through inhibition of gut fatty acid absorption and increase in basal metabolic rate. Furthermore, coffee has been associated with a significantly lower incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus,” Dr. Kistler added.

Direction of relationship unclear

Charlotte Mills, PhD, University of Reading, England, said this study “adds to the body of evidence from observational trials associating moderate coffee consumption with cardioprotection, which looks promising.”

However, with the observational design, it’s unclear “which direction the relationship goes – for example, does coffee make you healthy or do inherently healthier people consume coffee? Randomized controlled trials are needed to fully understand the relationship between coffee and health before recommendations can be made,” Dr. Mills told the UK nonprofit Science Media Centre.

Annette Creedon, PhD, nutrition scientist with the British Nutrition Foundation, said it’s possible that respondents over- or underestimated the amount of coffee that they were consuming at the start of the study when they self-reported their intake.

“It is therefore difficult to determine whether the outcomes can be directly associated with the behaviors in coffee consumption reported at the start of the study,” she told the Science Media Centre.

The study had no funding. Dr. Kistler has received funding from Abbott Medical for consultancy and speaking engagements and fellowship support from Biosense Webster. Dr. Lavie has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Mills has worked in collaboration with Nestle on research relating to coffee and health funded by UKRI. Dr. Creedon has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE CARDIOLOGY

Emphasis on weight loss in new type 2 diabetes guidance

STOCKHOLM – Weight loss should be a co–primary management goal for type 2 diabetes in adults, according to a new comprehensive joint consensus report from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association.

And while metformin is still recommended as first-line therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes with no other comorbidities, the statement expands the indications for use of other agents or combinations of agents as initial therapy for subgroups of patients, as part of individualized and patient-centered decision-making.

Last updated in 2019, the new “Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes” statement also places increased emphasis on social determinants of health, incorporates recent clinical trial data for cardiovascular and kidney outcomes for sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists to broaden recommendations for cardiorenal protection, and discusses health behaviors such as sleep and sitting. It also targets a wider audience than in the past by addressing health system organization to optimize delivery of diabetes care.

The new statement was presented during a 90-minute session at the annual meeting of the EASD, with 12 of its 14 European and American authors as presenters. The document was simultaneously published in Diabetologia and Diabetes Care.

During the discussion, panel member Jennifer Brigitte Green, MD, commented: “Many of these recommendations are not new. They’re modest revisions of recommendations that have been in place for years, but we know that actual implementation rates of use of these drugs in patients with established comorbidities are very low.”

“I think it’s time for communities, health care systems, etc, to actually introduce these as expectations of care... to assess quality because unless it’s considered formally to be a requirement of care I just don’t think we’re going to move that needle very much,” added Dr. Green, who is professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Vanita R. Aroda, MD, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, commented: “In the past, sometimes these recommendations created fodder for debate, but I don’t think this one will. It’s just really solidly evidence based, with the rationales presented throughout, including the figures. I think just having very clear evidence-based directions should support their dissemination and use.”

Weight management plays a prominent role in treatment

In an interview, writing panel cochair John B. Buse, MD, PhD, said: “We are saying that the four major components of type 2 diabetes care are glycemic management, cardiovascular risk management, weight management, and prevention of end-organ damage, particularly with regard to cardiorenal risk.”

“The weight management piece is much more explicit now,” said Dr. Buse, director of the Diabetes Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He noted that recent evidence from the intensive lifestyle trial DiRECT, conducted in the United Kingdom, the bariatric surgery literature, and the emergence of potent weight-loss drugs have meant that “achieving 10%-15% body weight loss is now possible.

“So, aiming for remission is something that might be attractive to patients and providers. This could be based on weight management, with the [chosen] method based on shared decision-making.”

According to the new report: “Weight loss of 5%-10% confers metabolic improvement; weight loss of 10%-15% or more can have a disease-modifying effect and lead to remission of diabetes, defined as normal blood glucose levels for 3 months or more in the absence of pharmacological therapy in a 2021 consensus report.”

“Weight loss may exert benefits that extend beyond glycemic management to improve risk factors for cardiometabolic disease and quality of life,” it adds.

Individualization featured throughout

The report’s sections cover principles of care, including the importance of diabetes self-management education and support and avoidance of therapeutic inertia. Detailed guidance addresses therapeutic options including lifestyle, weight management, and pharmacotherapy for treating type 2 diabetes.

Another entire section is devoted to personalizing treatment approaches based on individual characteristics, including new evidence from cardiorenal outcomes studies for SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists that have come out since the last consensus report.

The document advises: “Consider initial combination therapy with glucose-lowering agents, especially in those with high [hemoglobin] A1c at diagnosis (that is, > 70 mmol/mol [> 8.5%]), in younger people with type 2 diabetes (regardless of A1c), and in those in whom a stepwise approach would delay access to agents that provide cardiorenal protection beyond their glucose-lowering effects.”

Designed to be used and user-friendly

Under the “Putting it all together: strategies for implementation” section, several lists of “practical tips for clinicians” are provided for many of the topics covered.

A series of colorful infographics are included as well, addressing the “decision cycle for person-centered glycemic management in type 2 diabetes,” including a chart summarizing characteristics of available glucose-lowering medications, including cardiorenal protection.

Also mentioned is the importance of 24-hour physical behaviors (including sleep, sitting, and sweating) and the impact on cardiometabolic health, use of a “holistic person-centered approach” to type 2 diabetes management, and an algorithm on insulin use.

Dr. Buse has financial ties to numerous drug and device companies. Dr. Green is a consultant for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, Bayer, Sanofi, Anji, Vertex/ICON, and Valo. Dr. Aroda has served as a consultant for Applied Therapeutics, Duke, Fractyl, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Weight loss should be a co–primary management goal for type 2 diabetes in adults, according to a new comprehensive joint consensus report from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association.

And while metformin is still recommended as first-line therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes with no other comorbidities, the statement expands the indications for use of other agents or combinations of agents as initial therapy for subgroups of patients, as part of individualized and patient-centered decision-making.

Last updated in 2019, the new “Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes” statement also places increased emphasis on social determinants of health, incorporates recent clinical trial data for cardiovascular and kidney outcomes for sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists to broaden recommendations for cardiorenal protection, and discusses health behaviors such as sleep and sitting. It also targets a wider audience than in the past by addressing health system organization to optimize delivery of diabetes care.

The new statement was presented during a 90-minute session at the annual meeting of the EASD, with 12 of its 14 European and American authors as presenters. The document was simultaneously published in Diabetologia and Diabetes Care.

During the discussion, panel member Jennifer Brigitte Green, MD, commented: “Many of these recommendations are not new. They’re modest revisions of recommendations that have been in place for years, but we know that actual implementation rates of use of these drugs in patients with established comorbidities are very low.”

“I think it’s time for communities, health care systems, etc, to actually introduce these as expectations of care... to assess quality because unless it’s considered formally to be a requirement of care I just don’t think we’re going to move that needle very much,” added Dr. Green, who is professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Vanita R. Aroda, MD, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, commented: “In the past, sometimes these recommendations created fodder for debate, but I don’t think this one will. It’s just really solidly evidence based, with the rationales presented throughout, including the figures. I think just having very clear evidence-based directions should support their dissemination and use.”

Weight management plays a prominent role in treatment

In an interview, writing panel cochair John B. Buse, MD, PhD, said: “We are saying that the four major components of type 2 diabetes care are glycemic management, cardiovascular risk management, weight management, and prevention of end-organ damage, particularly with regard to cardiorenal risk.”

“The weight management piece is much more explicit now,” said Dr. Buse, director of the Diabetes Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He noted that recent evidence from the intensive lifestyle trial DiRECT, conducted in the United Kingdom, the bariatric surgery literature, and the emergence of potent weight-loss drugs have meant that “achieving 10%-15% body weight loss is now possible.

“So, aiming for remission is something that might be attractive to patients and providers. This could be based on weight management, with the [chosen] method based on shared decision-making.”

According to the new report: “Weight loss of 5%-10% confers metabolic improvement; weight loss of 10%-15% or more can have a disease-modifying effect and lead to remission of diabetes, defined as normal blood glucose levels for 3 months or more in the absence of pharmacological therapy in a 2021 consensus report.”

“Weight loss may exert benefits that extend beyond glycemic management to improve risk factors for cardiometabolic disease and quality of life,” it adds.

Individualization featured throughout

The report’s sections cover principles of care, including the importance of diabetes self-management education and support and avoidance of therapeutic inertia. Detailed guidance addresses therapeutic options including lifestyle, weight management, and pharmacotherapy for treating type 2 diabetes.

Another entire section is devoted to personalizing treatment approaches based on individual characteristics, including new evidence from cardiorenal outcomes studies for SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists that have come out since the last consensus report.

The document advises: “Consider initial combination therapy with glucose-lowering agents, especially in those with high [hemoglobin] A1c at diagnosis (that is, > 70 mmol/mol [> 8.5%]), in younger people with type 2 diabetes (regardless of A1c), and in those in whom a stepwise approach would delay access to agents that provide cardiorenal protection beyond their glucose-lowering effects.”

Designed to be used and user-friendly

Under the “Putting it all together: strategies for implementation” section, several lists of “practical tips for clinicians” are provided for many of the topics covered.

A series of colorful infographics are included as well, addressing the “decision cycle for person-centered glycemic management in type 2 diabetes,” including a chart summarizing characteristics of available glucose-lowering medications, including cardiorenal protection.

Also mentioned is the importance of 24-hour physical behaviors (including sleep, sitting, and sweating) and the impact on cardiometabolic health, use of a “holistic person-centered approach” to type 2 diabetes management, and an algorithm on insulin use.

Dr. Buse has financial ties to numerous drug and device companies. Dr. Green is a consultant for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, Bayer, Sanofi, Anji, Vertex/ICON, and Valo. Dr. Aroda has served as a consultant for Applied Therapeutics, Duke, Fractyl, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Weight loss should be a co–primary management goal for type 2 diabetes in adults, according to a new comprehensive joint consensus report from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association.

And while metformin is still recommended as first-line therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes with no other comorbidities, the statement expands the indications for use of other agents or combinations of agents as initial therapy for subgroups of patients, as part of individualized and patient-centered decision-making.

Last updated in 2019, the new “Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes” statement also places increased emphasis on social determinants of health, incorporates recent clinical trial data for cardiovascular and kidney outcomes for sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists to broaden recommendations for cardiorenal protection, and discusses health behaviors such as sleep and sitting. It also targets a wider audience than in the past by addressing health system organization to optimize delivery of diabetes care.

The new statement was presented during a 90-minute session at the annual meeting of the EASD, with 12 of its 14 European and American authors as presenters. The document was simultaneously published in Diabetologia and Diabetes Care.

During the discussion, panel member Jennifer Brigitte Green, MD, commented: “Many of these recommendations are not new. They’re modest revisions of recommendations that have been in place for years, but we know that actual implementation rates of use of these drugs in patients with established comorbidities are very low.”

“I think it’s time for communities, health care systems, etc, to actually introduce these as expectations of care... to assess quality because unless it’s considered formally to be a requirement of care I just don’t think we’re going to move that needle very much,” added Dr. Green, who is professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Vanita R. Aroda, MD, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and hypertension at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, commented: “In the past, sometimes these recommendations created fodder for debate, but I don’t think this one will. It’s just really solidly evidence based, with the rationales presented throughout, including the figures. I think just having very clear evidence-based directions should support their dissemination and use.”

Weight management plays a prominent role in treatment

In an interview, writing panel cochair John B. Buse, MD, PhD, said: “We are saying that the four major components of type 2 diabetes care are glycemic management, cardiovascular risk management, weight management, and prevention of end-organ damage, particularly with regard to cardiorenal risk.”

“The weight management piece is much more explicit now,” said Dr. Buse, director of the Diabetes Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He noted that recent evidence from the intensive lifestyle trial DiRECT, conducted in the United Kingdom, the bariatric surgery literature, and the emergence of potent weight-loss drugs have meant that “achieving 10%-15% body weight loss is now possible.

“So, aiming for remission is something that might be attractive to patients and providers. This could be based on weight management, with the [chosen] method based on shared decision-making.”

According to the new report: “Weight loss of 5%-10% confers metabolic improvement; weight loss of 10%-15% or more can have a disease-modifying effect and lead to remission of diabetes, defined as normal blood glucose levels for 3 months or more in the absence of pharmacological therapy in a 2021 consensus report.”

“Weight loss may exert benefits that extend beyond glycemic management to improve risk factors for cardiometabolic disease and quality of life,” it adds.

Individualization featured throughout

The report’s sections cover principles of care, including the importance of diabetes self-management education and support and avoidance of therapeutic inertia. Detailed guidance addresses therapeutic options including lifestyle, weight management, and pharmacotherapy for treating type 2 diabetes.

Another entire section is devoted to personalizing treatment approaches based on individual characteristics, including new evidence from cardiorenal outcomes studies for SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists that have come out since the last consensus report.

The document advises: “Consider initial combination therapy with glucose-lowering agents, especially in those with high [hemoglobin] A1c at diagnosis (that is, > 70 mmol/mol [> 8.5%]), in younger people with type 2 diabetes (regardless of A1c), and in those in whom a stepwise approach would delay access to agents that provide cardiorenal protection beyond their glucose-lowering effects.”

Designed to be used and user-friendly

Under the “Putting it all together: strategies for implementation” section, several lists of “practical tips for clinicians” are provided for many of the topics covered.