User login

ASCO goes ahead online, as conference center is used as hospital

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traditionally at this time of year, everyone working in cancer turns their attention toward Chicago, and 40,000 or so travel to the city for the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Not this year.

The McCormick Place convention center has been converted to a field hospital to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The cavernous meeting halls have been filled with makeshift wards with 750 acute care beds, as shown in a tweet from Toni Choueiri, MD, chief of genitourinary oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Center in Boston.

But the annual meeting is still going ahead, having been transferred online.

“We have to remember that even though there’s a pandemic going on and people are dying every day from coronavirus, people are still dying every day from cancer,” Richard Schilsky, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at ASCO, told Medscape Medical News.

“This pandemic will end, but cancer will continue, and we need to be able to continue to get the most cutting edge scientific results out there to our members and our constituents so they can act on those results on behalf of their patients,” he said.

The ASCO Virtual Scientific Program will take place over the weekend of May 30-31.

“We’re certainly hoping that we’re going to deliver a program that features all of the most important science that would have been presented in person in Chicago,” Schilsky commented in an interview.

Most of the presentations will be prerecorded and then streamed, which “we hope will mitigate any of the technical glitches that could come from trying to do a live broadcast of the meeting,” he said.

There will be 250 oral and 2500 poster presentations in 24 disease-based and specialty tracks.

The majority of the abstracts will be released online on May 13. The majority of the on-demand content will be released on May 29. Some of the abstracts will be highlighted at ASCO press briefings and released on those two dates.

But some of the material will be made available only on the weekend of the meeting. The opening session, plenaries featuring late-breaking abstracts, special highlights sessions, and other clinical science symposia will be broadcast on Saturday, May 30, and Sunday, May 31 (the schedule for the weekend program is available on the ASCO meeting website).

Among the plenary presentations are some clinical results that are likely to change practice immediately, Schilsky predicted. These include data to be presented in the following abstracts:

- Abstract LBA4 on the KEYNOTE-177 study comparing immunotherapy using pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors show microsatellite instability or mismatch repair deficiency;

- Abstract LBA5 on the ADAURA study exploring osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) as adjuvant therapy after complete tumor reseaction in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer whose tumors are EGFR mutation positive;

- Abstract LBA1 on the JAVELIN Bladder 100 study exploring maintenance avelumab (Bavencio, Merck and Pfizer) with best supportive care after platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.

However, some of the material that would have been part of the annual meeting, which includes mostly educational sessions and invited talks, has been moved to another event, the ASCO Educational Program, to be held in August 2020.

“So I suppose, in the grand scheme of things, the meeting is going to be compressed a little bit,” Schilsky commented. “Obviously, we can’t deliver all the interactions that happen in the hallways and everywhere else at the meeting that really gives so much energy to the meeting, but, at this moment in our history, probably getting the science out there is what’s most important.”

Virtual exhibition hall

There will also be a virtual exhibition hall, which will open on May 29.

“Just as there is a typical exhibit hall in the convention center,” Schilsky commented, most of the companies that were planning to be in Chicago have “now transitioned to creating a virtual booth that people who are participating in the virtual meeting can visit.

“I don’t know exactly how each company is going to use their time and their virtual space, and that’s part of the whole learning process here to see how this whole experiment is going to work out,” he added.

Unlike some of the other conferences that have gone virtual, in which access has been made available to everyone for free, registration is still required for the ASCO meeting. But the society notes that the registration fee has been discounted for nonmembers and has been waived for ASCO members. Also, the fee covers both the Virtual Scientific Program in May and the ASCO Educational Program in August.

Registrants will have access to video and slide presentations, as well as discussant commentaries, for 180 days.

The article first appeared on Medscape.com.

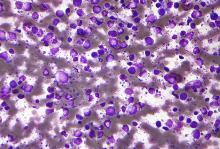

DLBCL patients at academic centers had significantly better survival

Researchers used the U.S. National Cancer Database to identify patients with a diagnosis of DLBCL from 2004 to 2015. The researchers identified 27,690 patients for the study. The majority of the patients were white (89.3%) and men (53.7%), with an average age of 64 years. A total of 57.6% of the patients had been treated at nonacademic centers and 42.4% at academic centers, and no notable differences were seen in facility choice among the low- to high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk categories.

The researchers found that overall survival of the DLBCL patients at academic centers was 108.3 months versus 74.5 months at nonacademic centers (P < .001), according to the study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

In addition, the median survival for patients with high-risk disease treated at academic centers was more than twice that of high-risk patients treated at nonacademic centers (33.5 months vs. 14.4 months, respectively; P < .001). Although the median survival for the other risk categories was also improved, the difference was less pronounced in the groups with lower IPI scores, according to the researchers.

Long-term overall survival for all patients with DLBCL at academic centers was significantly improved at both 5 and 10 years (59% and 43% survival, respectively) compared with those patients treated at nonacademic centers (51% and 35% survival, respectively; P < .001).

Speculating on factors that might be involved in this discrepancy in survival, the researchers suggested that academic centers might provide increased access to clinical trials, improved physician expertise, as well as improved treatment facilities and supportive care.

“Our results should prompt further investigation in precisely determining the factors that might support this significant effect on decreased survival among those treated in the community and help ameliorate this discrepancy,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ermann DA et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(4): e17483.

Researchers used the U.S. National Cancer Database to identify patients with a diagnosis of DLBCL from 2004 to 2015. The researchers identified 27,690 patients for the study. The majority of the patients were white (89.3%) and men (53.7%), with an average age of 64 years. A total of 57.6% of the patients had been treated at nonacademic centers and 42.4% at academic centers, and no notable differences were seen in facility choice among the low- to high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk categories.

The researchers found that overall survival of the DLBCL patients at academic centers was 108.3 months versus 74.5 months at nonacademic centers (P < .001), according to the study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

In addition, the median survival for patients with high-risk disease treated at academic centers was more than twice that of high-risk patients treated at nonacademic centers (33.5 months vs. 14.4 months, respectively; P < .001). Although the median survival for the other risk categories was also improved, the difference was less pronounced in the groups with lower IPI scores, according to the researchers.

Long-term overall survival for all patients with DLBCL at academic centers was significantly improved at both 5 and 10 years (59% and 43% survival, respectively) compared with those patients treated at nonacademic centers (51% and 35% survival, respectively; P < .001).

Speculating on factors that might be involved in this discrepancy in survival, the researchers suggested that academic centers might provide increased access to clinical trials, improved physician expertise, as well as improved treatment facilities and supportive care.

“Our results should prompt further investigation in precisely determining the factors that might support this significant effect on decreased survival among those treated in the community and help ameliorate this discrepancy,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ermann DA et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(4): e17483.

Researchers used the U.S. National Cancer Database to identify patients with a diagnosis of DLBCL from 2004 to 2015. The researchers identified 27,690 patients for the study. The majority of the patients were white (89.3%) and men (53.7%), with an average age of 64 years. A total of 57.6% of the patients had been treated at nonacademic centers and 42.4% at academic centers, and no notable differences were seen in facility choice among the low- to high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk categories.

The researchers found that overall survival of the DLBCL patients at academic centers was 108.3 months versus 74.5 months at nonacademic centers (P < .001), according to the study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

In addition, the median survival for patients with high-risk disease treated at academic centers was more than twice that of high-risk patients treated at nonacademic centers (33.5 months vs. 14.4 months, respectively; P < .001). Although the median survival for the other risk categories was also improved, the difference was less pronounced in the groups with lower IPI scores, according to the researchers.

Long-term overall survival for all patients with DLBCL at academic centers was significantly improved at both 5 and 10 years (59% and 43% survival, respectively) compared with those patients treated at nonacademic centers (51% and 35% survival, respectively; P < .001).

Speculating on factors that might be involved in this discrepancy in survival, the researchers suggested that academic centers might provide increased access to clinical trials, improved physician expertise, as well as improved treatment facilities and supportive care.

“Our results should prompt further investigation in precisely determining the factors that might support this significant effect on decreased survival among those treated in the community and help ameliorate this discrepancy,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ermann DA et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(4): e17483.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA AND LEUKEMIA

COVID-19 death rate was twice as high in cancer patients in NYC study

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

FROM CANCER DISCOVERY

The Diagnosis and Management of Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas (FULL)

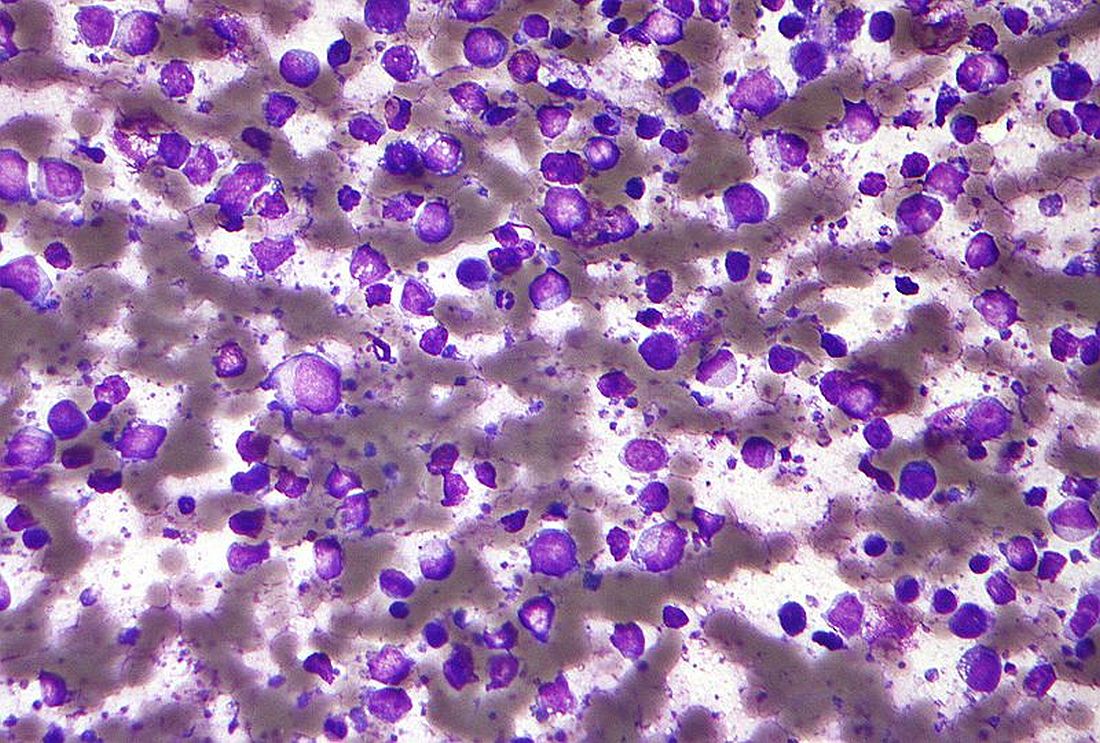

John Zic, MD. Let’s start by defining cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) and how they differ from other non-Hodgkin lymphomas. We also should discuss classification, which can be very confusing and epidemiology as it relates to the veteran population. Then I think we should dive into challenges with diagnosis and when should a VA or any provider consider mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome—the 2 most common variants of CTCLs.

I like to define the primary CTCLs as malignancies of the T-cell where the primary organ of involvement is the skin. However, this disease can spread to lymph nodes and visceral organs and the blood compartment in more advanced patients. Alejandro, could you provide some highlights about how CTCLs are classified?

Alejandro Ariel Gru, MD. Lymphomas are divided in the general hematology/oncology practice as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Traditionally all lymphomas that occur on the skin are non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes. That has specific connotations in terms of diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Because the T cells are one of the main residents of the subtypes of lymphocytes you encounter on the skin, most lymphomas that occur on the skin are derived of T-cell origin. B-cell lymphomas, in general, tend to be relatively uncommon or more infrequent.

There are 3 main subtypes of CTCL that present on the skin.1 MF is, by far, the most common subtype of CTCL. The disease tends to present in patients who are usually aged > 60 years and is more frequent in white males. It’s a lymphoma that is particularly relevant to the veteran population. The second subtype has many similarities to MF but shows substantial peripheral blood involvement and is referred to as Sézary syndrome. The third group is encompassed under the term CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. This group includes 2 main subtypes: primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma and lymphomatoid papulosis. Some cases of MF develop progression to what we call large cell transformation, which implies cytologic transformation to a more aggressive lymphoma.

There are other cutaneous lymphomas that are far less common. Some are indolent and others can be more aggressive, but they represent < 5% of all CTCL subtypes.

Lauren Pinter-Brown, MD. That was a great summary about these non-Hodgkin lymphomas. In the veteran population, it’s wise to remember that there are many kinds of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Because of the action that they have seen, some people, such as Vietnam veterans, might be more susceptible to non-Hodgkin lymphomas than others.

John Zic. That’s a good point because certainly non-Hodgkin lymphomas are listed as one of the potential disease associations with exposure to Agent Orange.

I’d like to move on to epidemiology and the incidence of MF and Sézary syndrome. An article that came out of Emory University in 2013 is one of the more up-to-date articles to examine the incidence and survival patterns of CTCL.2 The authors looked at patients from 2005 to 2008 and identified 2,273 patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. They estimated that the incidence of MF in the US population is about 5.5 per 1,000,000 per year, which certainly makes it a rare disease. The incidence of Sézary syndrome was 0.1 per 1,000,000 per year, which comes out to about 1 per 10 million per year.

However, the MF incidence needs to be contrasted to the estimated incidence in the veteran population. In 2016, Larisa Geskin and colleagues from Columbia University and the Bronx US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center examined the VA database of patients with diagnoses of MF and Sézary syndrome.3 They combined them, but I have a feeling that the amount of Sézary syndrome patients was much less than those with MF. They estimated an incidence per million of 62 to 79 cases per 1,000,000 per year. The conclusion of Dr. Geskin’s study stated that the incidence of CTCL in the veteran population appears to be anywhere from 6 to 8 times higher. But if we use the most recent US incidence rates, it’s more than 10 times higher.

Those of you who have worked with veterans, either at the VA or in your private practice, do you have any ideas about why that might be?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. As you previously discussed, this is an illness of older people, and Vietnam veterans now are in their 60s and 70s. They may account for a lot of these diagnoses.

John Zic. That’s a good point. There’s quite a bit of talk about exposure to Agent Orange. But honestly, we really don’t know the cause of any of the CTCLs. We have not been able to identify a single cause. There are some risk factors. A 2014 article from the Journal of the National Cancer Institute looked at 324 cases of CTCL and compared it with 17,000 controls.4 They showed some interesting risk factors, such as body mass index (BMI) > 30 and smoking > 40 years. Similar to previous European studies, they showed that occupations like being a farmer, a painter, a woodworker, or a carpenter may carry additional risk.I wonder whether or not veterans were more likely to have some of these risk factors that this epidemiologic study picked up in addition to exposures that they may have encountered during their active-duty service. Interestingly, a decreased risk factor for developing MF was moderate physical activity. Clearly though, there are a large number of patients with CTCL in the veteran population.

I’d like to turn now to some of the challenges with diagnosis. Marianne, could you share some of your experience with early-stage disease and about how long it took them to be diagnosed?

Marianne Tawa, RN, MSN, ANP. Speaking specifically about early-stage disease, patients often share a history of waxing and waning rash that may not be particularly itchy. Confounding the picture, the distribution of early patch or plaque stage CTCL rash frequently occurs in covered areas. Many patients miss out on complete skin examinations by providers, thus early-stage CTCL may not be appreciated in a timely manner.

In certain scenarios, it may take upward of 5 to 7 years before the CTCL diagnosis is rendered. This is not because the patient delayed care. Nor is it because a skin biopsy was not performed. The progression of the disease and meeting the classic features of histology under the microscope can require clinical observation over time and repeated skin biopsies. We recommend patients refrain from topical steroid applications for 2 to 4 weeks prior to skin biopsy if we have a strong suspicion of CTCL. Many patients will report having a chronic eczematous process. Some patients may have a history of parapsoriasis, and they’re on the continuum for CTCL. That’s a common story for CTCL patients.

John Zic. What is the role of a skin biopsy in the diagnosis of CTCL? We see many patients who have had multiple skin biopsies who often wonder whether or not the diagnosis was missed by either the clinician or the pathologist.

Alejandro Ariel Gru. That is a great area of challenge in terms of pathologic diagnosis of early MF. A study led by Julia Scarisbrick, from an international registry data (PROCLIPI) on the early stages of the disease, showed a median delay of diagnosis of early MF of approximately 36 months.5 For all physicians involved in the diagnosis and care of patients with MF, the delay is probably significantly higher than that. We’ve seen patients who have lived without a diagnosis for a period of 10 or sometimes 15 years. That suggests that many cases are behaving in an indolent fashion, and patients are not progressing through the ‘natural’ stages of the disease and remain at the early stage. There also is the potential that other chronic inflammatory conditions, particularly psoriasis or parapsoriasis, can be confused with this entity. The diagnosis of certain types of parapsoriasis, can belong to the same spectrum of MF and can be treated in a similar way than patients with early stage MF are, such as phototherapy or methotrexate.

The diagnosis of MF relies on a combination of clinical, pathologic, and immunophenotypic findings where it is desired or preferred that at least 2 biopsies are done from different sides of the body. In addition to having a good clinical history that supports the diagnosis, a history of patches, plaques, and sometimes tumors in advanced stages in particular locations that are covered from the light (eg, trunk, buttocks, upper thighs, etc) combined with specific histopathologic criteria are capital to establish an accurate diagnosis.

In the biopsies, we look particularly for a lymphoid infiltrate that shows extension to the epidermis. We use the term epidermotropism to imply that these abnormal or neoplastic lymphocytes extend into the epidermis. They are also cytologically atypical. We see variations in the nucleus. In the size, we see a different character of the chromatin where they can be hyperchromatic. We also look for immunophenotypic aberrations, and particularly we analyze for patterns of expression of T-cell markers. Most cases of MF belong to a subset of T cells that are called CD4-positive or T-helper cells. We look for a patterned ratio of the CD4 and CD8 between the epidermis and an aberrant loss of the CD7 T-cell marker. Once we establish that we can see significant loss of these markers, we can tell where there is something wrong with that T-cell population, and likely belong to a neoplastic category.

In addition, we also rely on the molecular evaluation and search of a clonal population of T cells, by means of a T-cell receptor gene rearrangement study. Ideally, we like to see the establishment of a single clone of T cells that is matched in different biopsy sites. Proving that the same clone is present in 2 separate biopsies in 2 separate sites is the gold standard for diagnosis.6

John Zic. To recap, a biopsy is indicated for patients who have patches or plaques (that are slightly raised above the skin) in sun-protected areas that are fixed; rather than completely go away in the summer and come back in the winter, they are fixed if they have been present > 6 to 12 months. Many of these patients are diagnosed with eczema, psoriasis, allergic contact dermatitis, and other skin diseases before the clinician starts to think about other diagnoses, such as CTCL.

I agree that I would not rule out the diagnosis with 1 biopsy that does not show classic histologic changes. Also, I think that it’s important to alert the pathologist that you’re considering a diagnosis of T-cell lymphoma, either MF or some of the other subtypes, because that will certainly alert them to look a little closer at the infiltrating cells and perhaps do some of the other testing that was mentioned. Once we establish the MF diagnosis, staging studies may be indicated.

Lauren Pinter-Brown. Early stage would be patients with patches or plaques. Stage IA would be < 10% body surface area, and stage IB would be > 10%. I don’t perform scans for early-stage patients, but I do a very thorough physical and perform blood tests. For patients that have more advanced disease, such as tumors, erythroderma, or Sézary syndrome, I would conduct the same thorough examination and blood tests and scan the patient either with a computed tomography (CT) or a positron emission tomography (PET)/CT to detect adenopathy. We have to recognize that most of the adenopathy that is detected in these patients is peripheral, and we can feel it on physical examination.

John Zic. Do you prefer one imaging modality over the other? CT scan with IV contrast vs PET/CT?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. I tend to use PET/CT because it illuminates extranodal sites as well. I have to admit that sometimes it’s a problem to get that approved with insurance.

John Zic. In the federal system, many PET/CT scans are performed at other facilities. That would be an extra step in getting approval.

You mentioned Sézary syndrome. We should consider a diagnosis of Sézary syndrome when you have a patient with erythroderma, which means that they have > 80% of the skin covered in redness and scaling.

Lauren Pinter-Brown. The first step is to do a complete blood count (CBC) and see if there’s a lymphocytosis. Sometimes that really isn’t very sensitive, so my go-to test is flow cytometry. We are looking for an abnormal population of cells that, unlike normal T cells, often lack certain T-cell antigens. The most common would be CD7. We can confirm that this is a clone by T-cell gene rearrangement, and often in Sézary we like to compare the gene rearrangement seen in blood with what might be seen in the skin biopsy to confirm that they’re the same clone.

John Zic. That’s an excellent point. I know there are specific criteria to meet significant blood involvement. That is a topic of conversation among CTCL experts and something that might be changing over the next few years. But I think as it stands right now, having a lymphocytosis or at least an elevated CD4 count along with having a clone in the blood matching the clone in the skin are the first 2 steps in assessing blood involvement. However, the flow cytometry is very important. Not all medical centers are going to do flow cytometry—looking specifically for a drop of the CD7 or CD26 antigen among the CD4 population. But that is one of the major criteria that we look for in those patients with suspected blood involvement.

Marianne Tawa. Additionally, we would advise obtaining flow cytometry on patients that look like they have a robust skin burden with lots of patches, plaques, or tumors. We also perform lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) with staging.

John Zic. What do you usually tell patients with early-stage disease, those that have patches and plaques?

Marianne Tawa. For patients with stage IA disease, we are very optimistic about their prospects. We explain that the likelihood that early-stage disease will progress to a more advanced stage or rare variant is unlikely. This is very much a chronic disease, and the goal is to manage appropriately, palliate symptoms, and preserve quality of life (QOL).

Lauren Pinter-Brown. I often refer to a landmark paper by Youn H. Kim and colleagues that shows us that patients with IA disease who are at least treated usually have a normal lifespan.7 I encourage patients by sharing that data with them.

John Zic. Sean Whittaker and colleagues in the United Kingdom identified 5 risk factors for early-stage patients that may put them at higher risk for progressing: aged > 60 years; having a variant called folliculotropic MF; having palpable lymph nodes even if they’re reactive on biopsy, having plaques, and male sex.8 For staging of lymph nodes, what’s your usual approach when you see a patient with palpable lymph nodes?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. Many patients, particularly those with advanced skin disease, may have palpable lymph nodes that are reacting to their skin disease and on pathology would be dermatopathic. That would not change my management. I pay attention to the quality of the lymph node—if it’s very firm, if it’s > 2 cm, if it is persistent—before I biopsy. These patients have a higher incidence of wound infection after excisional biopsy. If the patient has pathologic lymph node involvement and effacement of the node with malignant cells, I would change my management. I do need to know that sort of information.

John Zic. Alejandro, as a hematopathologist can you comment on the debate about whether or not we actually do need an excisional biopsy or whether or not we can get a core lymph node biopsy to give you all the information that you need to grade it?

Alejandro Ariel Gru. There are 2 main modalities of biopsies we typically see for lymph nodes for evaluation and staging for involvement of CTCL. One is the traditional excisional biopsy that for the most part requires surgery with general anesthesia and has all the major implications that that type of procedure has. Many centers are looking at less invasive types of procedures, and needle core biopsies have become one of the most common forms of biopsy for all lymphoma subtypes. Excisional biopsies have the advantage of being able to see the whole lymph node, so you can determine and evaluate the architecture very well. Whereas needle core biopsies typically use a small needle to obtain a small piece of the tissue.

The likelihood of a successful diagnosis and accurate staging was compared recently in the British Journal of Dermatology.9 They were able to perform accurate staging in needle core biopsies of patients with MF. However, this is still a matter of debate; many people feel they are more likely to get enough information from an excisional biopsy. As we know, excisional biopsies sometimes can be hard, particularly if the large lymph node is located in an area that is difficult to access, for example, a retroperitoneal lymph node.

There are many staging categories that are used in the pathologic evaluation of lymph node involvement. On one hand, we could see the so-called dermatopathic changes, which is a reactive form of lymphadenopathy that typically happens in patients who have skin rashes and where there is no evidence of direct involvement by the disease (although there are some patients who can have T-cell clones by molecular methods). The patients who have clonal T cells perhaps might not do as well as the ones who do not. On the other hand, we have patients for whom the whole architecture of the lymph node is effaced or replaced by neoplastic malignant cells. Those patients are probably going to need more aggressive forms of therapy.10

John Zic. The type of lymph node biopsy has been a hot topic. If patients have palpable lymph nodes in the cervical, axillary, and inguinal area, I don’t know if it’s a consensus, but the recommendation right now is to consider performing a lymph node biopsy of the cervical lymph nodes first, axillary second, and inguinal lymph nodes third. That might have to do with the complication rates for those different areas.

I’d like to switch to a discussion to more advanced disease. CTCL tumors are defined as a dome-shaped nodule > 1 cm. They don’t have to be very big before we label it a tumor, and the disease is considered more advanced. For patients with a few tumors, what does your prognosis discussion sound like?

Marianne Tawa. Certainly, the prognosis discussion can become slightly more complicated when you move into the realm of tumor-stage development. This is especially true if a CTCL patient has lived with and managed indolent patches or plaques for several years. We approach these patients with optimism and with the goal of managing their tumors, whether it be with a skin-directed option, such as localized radiation or a host of approved systemic therapies. Patients presenting with or developing tumor-stage disease over time will require additional staging workup compared with early-stage disease staging practice. Patients are counseled on imaging use in tumor-stage disease and why flow cytometry may be requested to rule in or rule out accompanying peripheral blood involvement. Patients are exposed to a myriad of pictures, stories, and survival statistics from Internet research. It becomes our task to inform them of their unique presentation and tailored treatment plan, which thankfully may produce more favorable responses than those presented online.

Lauren Pinter-Brown. One thing that we focus on is the idea that a statistic regarding prognosis isn’t predictive for an individual patient. When patients go online, we caution them that many of the statistics are really old. There’s been a lot of new therapies in the past 10 years. Just looking at my patients, my feeling is that their prognosis has continued to improve over the decades that I’ve been involved in this area.

We have to take the statistics with a grain of salt, though certainly someone that has Sézary syndrome or someone that has nodal involvement or tumors is not going to fare as well as the patients that we talked about with stage I disease. However, if we all continue to do our jobs and have more and more treatment options for patients, that’s certainly going to change over time as it has with other non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

John Zic. We’ve all treated advanced patients with disease and some, of course, have died of the disease. When patients die of advanced CTCL, what are the things that lead to their demise?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. Probably the most common would be infections because their skin barrier has been broken. As the disease advances, their immune system also deteriorates. We may contribute to that sometimes with some of the therapies that we use, although we try and be judicious. First and foremost, the primary cause of death remains infection and sometimes inanition.

Marianne Tawa. I agree, infection or just the unfortunate progression of their lymphoma through the various armamentarium of treatments would be the 2 reasons.

John Zic. Let’s dive into therapy. I want to start with early stage. While, I don’t think there’s a role for systemic anticancer agents, certainly the IV agents for most patients with early-stage disease Marianne, you mentioned phototherapy. What are the types of phototherapy that you offer?

Marianne Tawa. We would start out with narrow band UVB therapy for patients with > 10% body surface area involvement. When applying topical corticosteroids to wider surface areas of the patient’s body is no longer feasible or effective, we recommend the initiation of narrow band UVB phototherapy. This is preferred because of its lessor adverse effect (AE) profile as far as nonmelanoma skin cancer risk. Patients commence narrow band UVB 3 times per week, with a goal of getting the patient into remission over a matter of months and then slowly tapering the phototherapy so that they get to a maintenance of once weekly.

Realizing that narrow band UVB may not penetrate deeper plaques or effectively reach folliculotropic variant of CTCL, we would employ PUVA, (psoralen and UVA). Patients are expected to protect their eyes with UVA glasses and remain out of the sun 24 hours following PUVA treatments. The cost of the methoxsalen can be an issue for some patients. Nonmelanoma skin cancer risks are increased in patients undergoing long-term PUVA treatments. Routine skin cancer surveillance is key.

There are monetary, time, and travel demands for patients receiving phototherapy. Thus, many CTCL patients are moving toward home-based narrow band UVB units supervised by their treating dermatologist. Other skin-directed treatment options, aside from topical corticosteroids and phototherapy, would include topical nitrogen mustard, imiquimod, and localized or total skin electron beam radiation.

John Zic. Here in Nashville, some of our veterans travel hundreds of miles to get to our center. It’s not practical for them to come here for the narrow band UVB phototherapy. Veterans can get approval through the VA Choice programs to have phototherapy performed by a local dermatologist closer to home. We also have had many veterans who choose to get home narrow band UVB phototherapy, which can be quite effective. Narrow band UVB phototherapy is among the most effective therapies for patients with generalized patches in particular, and maybe some with just a few plaques.

Medium potency topical steroids are not as helpful as superpotent topical steroids such as clobetasol, dipropionate ointment, or betamethasone dipropionate ointment. Usually, I tell patients to apply it twice a day for 8 weeks. You must be careful because these high-potency topical steroids can cause thinning of the skin, but it’s rarely seen, even in patients that may use them for 8 weeks if they’re applying them just to their patches and thin plaques. There are a few other topicals. There’s bexarotene gel, which is a topical retinoid, and mechlorethamine or nitrogen mustard gel that are available as topicals. Both of those can be helpful if patients have < 10% body surface area of patches or plaques because they can apply that at home.

Because of the excellent prognosis for patients in early stages, this is an area we want to try to avoid doing harm. For patients with advanced disease, what are some of the decisions that you think about in recommending a patient to get radiation therapy?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. I use radiation therapy sparingly and primarily for patients who either have only 1 tumor and the rest of their disease is patch and plaque or for patients who have very large tumors that are either cosmetically unacceptable or creating infection or pain. I treat people with systemic therapies primarily to prevent the formation of tumors.

John Zic. There probably is a role for total skin electron beam radiotherapy in patients who have failed multiple other skin-directed therapies and are progressing and then perhaps a role for more advanced patients who have multiple tumors where you’re trying to get some control of the disease. Are there any other situations where you might consider total skin electron beam?

Marianne Tawa. Yes, those are 2 scenarios. A third scenario would be in patients preparing for stem cell transplant. We typically do a modified 12 Gy regimen of total skin electron beam for palliation and up to 24 Gy regimen for patients who are in earnest preparing for a stem cell transplant.

John Zic. Systemic therapies also treat this disease. There are 2 oral agents. One is bexarotene capsules, a retinoid that binds to the RXR receptor and has a multitude of effects on different organ systems. It is probably the best tolerated oral agent we have. The other FDA-approved agent is vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, but it has more gastrointestinal AEs than does bexarotene. Bexarotene has AEs as well, including hypertriglyceridemia and central hypothyroidism, which can throw a curveball to unsuspecting primary care physicians who might check thyroid function studies in these patients.

We certainly need to know about those AEs. There are many patients who have tumor-stage disease that can have radiotherapy to several tumors, then go on a drug like bexarotene capsules and may be able to maintain the remission for years. In my experience, it’s a drug that patients usually stay on. They can be weaned to a very low dose, but I’ve had several patients who come off of bexarotene only to suffer relapses.

Lauren, what are some of the things that you think about when you declare someone as having failed bexarotene or vorinostat and you’re thinking about IV therapies?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. Patient comorbidities and the particular compartment of their body that is involved are important factors. Do they have blood involvement, or not? Do they have nodal involvement, or not? Another concern is both acute and chronic toxicities that need to be discussed with the patient to determine an acceptable QOL. Finally, the schedule that you’re giving the drug. Some people may not be able to come in frequently. There are a lot of variables that go into making an individual decision at a particular time for a specific patient who will be using parenteral therapies.

John Zic. If we have a patient with advanced MF, tumors, and perhaps lymph node involvement, what are some of the systemic options that you would consider?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. With nodal involvement, an attractive option is something like IV romidepsin because we know that it treats peripheral T-cell lymphomas, which are aggressive nodal T-cell lymphomas. It’s FDA approved and also treats CTCL. Another is brentuximab vedotin if there is significant CD30 expression. It also is FDA approved for CTCL and has a long track record of treating certain peripheral T-cell lymphomas like anaplastic large cell.

John Zic. When would the stem cell transplant discussion start at your institution?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. It starts earlier for a younger patient because even though we do have lots of treatment if someone is aged 20 or30 years, I don’t really have any illusions that I have enough treatment options for them to live a normal lifespan if they have advanced disease. It’s a possibility for any patient when I see that the future options are dwindling, and that I am not going to be able to control the patient’s disease for much longer. Having said that, patients who have tumor-stage disease are among those that don’t do quite as well with allogeneic transplantation; ironically, patients with Sézary syndrome or erythroderma might do a little bit better.

John Zic. Before considering a stem cell transplant for patients with Sézary syndrome, that is erythroderma with significant blood involvement, what other treatment options would you offer?

Marianne Tawa. For low blood-burden disease, we might look at extracorporeal photopheresis as monotherapy or in combination with interferon or bexarotene. For patients with higher blood burden we might recommend low-dose alemtuzumab, especially if they have abundant CD52 expression. We also consider the newly FDA-approved anti-CCR4 antibody treatment, mogamulizumab, for patients presenting with Sézary syndrome. It is generally well tolerated but does have the potential for producing infusion reactions or drug rash.

Romidepsin has efficacy in blood, lymph node, and skin compartments. The primary considerations for patients considering romidepsin are prolonged infusion times and QOL AEs with gastrointestinal and taste disturbances and fatigue.

John Zic. Both of you have brought up an excellent point. This is a disease that while we do not have a good chance of curing, we have a pretty fair chance of controlling, especially if it’s early stage. The data from the stem cell transplant literature indicate that stem cell transplant may be one of the few modalities that we have that may offer a cure.11

Lauren Pinter-Brown. There are patients who are cured with allogeneic transplants; and the very first allogeneic transplants were performed well over 20 years ago. Many patients, even some in my practice, who were among those patients and continue to do extremely well without any evidence of disease. Sometimes when people have allogeneic transplantation, their disease relapse may be in a more indolent form that’s much easier to deal with than their original disease. Even if they’re not cured, the fact that the aggressive disease seems to be at bay may make them much easier to treat.

John Zic. Those are excellent points. You brought up photopheresis as a treatment modality for patients with evolving or early Sézary syndrome and patients with erythrodermic MF can also respond. We have a lot of experience with that at the Nashville VA medical center. We’re one of the few VA hospitals in the US that has a photopheresis unit. But the modality is available at many academic medical centers because it’s a treatment for graft-vs-host disease.

We tend to also consider photopheresis in patients who may have had an excellent response to another systemic agent. There are some data that patients who received photopheresis, after total skin electron beam therapy vs those who received chemotherapy after radiation, had a longer disease-free survival.12

I’d like to end with a discussion of something that’s very important, which is managing QOL issues for patients with CTCL. Itch is among some of the worst symptoms that can cause suffering in patients. But it is sometimes not a problem at all for patients who have a few patches or plaques. That’s one reason why they might ignore their rash. Certainly, as the disease progresses, especially those patients with erythroderma, the itch can be intractable and can have a major impact on their life. What are some approaches to managing itch at your institutions?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. One thing to be aware of is that the itch is not usually mediated by histamine, though people will often put the patients on a lot of antihistamines. I don’t find those to be the most effective treatments. I think of the itch in these patients as more of a neuropathic condition and would tend to treat more with things that you might use for neuropathy, such as gabapentin or doxepin or antidepressants. There’s a whole host of other treatments, such as aprepitant, something that I would use as an antiemetic, that might also be helpful for pruritus in this patient population.

John Zic. That’s my experience as well. I have found gabapentin to be helpful for patients with itch, though not universally.

Marianne Tawa. I consider itch a huge QOL concern for a large majority of our patients with a CTCL diagnosis. It’s on par with pain. In early-stage disease, pruritus levels improve as the cutaneous burden is reduced with skin-directed therapies such as, topical corticosteroid or phototherapy.

SSRI agents could also be considered for select patients. The antiemetic agent, aprepitant has been useful for addressing itch in a subset of our patients with Sézary syndrome. Patients will also seek out complementary modalities such acupuncture, hypnosis, and guided imagery.

John Zic. Because the disease itself affects the skin and can lead to dryness, patients often suffer with dry skin. When I trained in Chicago, that was the foundation of our treatment, making sure that patients are using a super fatted soap such as Dove (Unilever, London, United Kingdom) or Cetaphil (Galderma Laboratories; Fort Worth, TX), making sure that they’re lubricating their skin frequently with something perhaps in the wintertime as thick as petroleum jelly. And then in the summertime perhaps with Sarna lotion (Crown Laboratories; Johnson City, TN), which has menthol. It’s important to note that when the patient’s skin is infected, the itch can skyrocket. Being aware and monitoring the skin for signs of infection such as crusting and impetigo-like findings can be helpful.

I also wanted to touch on fatigue. Patients can have fatigue for many reasons. Sometimes it’s because the itch is interfering with their sleep. How do you approach managing fatigue?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. There have been many studies about cancer fatigue, and it appears that one of the cheapest and easiest modalities is for patients to walk. We often suggest that our patients go on walks, however much they can do, because that has been seen over and over again in studies of cancer fatigue to be beneficial.

John Zic. Do you have any advice for nurses that might be helping to manage patients in a cutaneous lymphoma clinic?

Marianne Tawa. As this is a rare disease, nursing encounters with patients carrying a diagnosis of CTCL in both oncology and dermatology settings may be few and far between. I recommend nurses familiarize themselves with articles published on CTCL topics found in both dermatology and oncology peer review journals. Another avenue for gaining insight and education would be through continuing education courses. Resources can also be found for nurses, patients, and caregivers through advocacy foundations such as the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation (www.clfoundation.org) and the Lymphoma Research Foundation ([email protected]).

John Zic. Is there anything else that anyone would like to add to our discussion?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. One thing that we touched upon, but I was concerned that we didn’t emphasize, was the use of flow cytometry as a diagnostic tool in a patient with erythroderma. Sometimes biopsies of patients with erythroderma are not diagnostic, so clinicians need to be aware that there are other ways of diagnosing patients—nodal biopsy or flow cytometry. They should not only think of it as a staging tool but sometimes as a diagnostic tool.

Alejandro Ariel Gru. I agree. Particularly in patients who have Sézary syndrome or MF with peripheral blood involvement, sometimes the findings on the biopsy show a dissociation between how impressive the clinical presentation of the patient might be and how very few findings you might encounter on the skin biopsy. Therefore, relying on flow cytometry as a diagnostic tool is capital. Lauren, you briefly mentioned the criteria, which is looking for an abnormal CD4 to CD8 ratio of > 10%, abnormal loss of CD7, > 40%, or abnormal loss of CD26 of > 30%.

In addition, there are new markers that are now undergoing validation in the diagnosis of Sézary syndrome. One is KIR3DL2, which is a natural killer receptor that has been shown to be significantly upregulated in Sézary syndrome and appears to be both more sensitive and specific. With that also comes therapies that target the KIR3DL2 molecule.

John Zic. One of the first things we teach our dermatology residents to work up patients with erythroderma is that they shouldn’t expect the skin biopsy to help them sort out the cause of the erythroderma. As you mentioned, Lauren, the flow cytometry of peripheral blood should always be accompanied by a CBC with differential and platelets. And if the patients do have lymph nodes, consider a biopsy because sometimes that’s where you can make the firmest diagnosis of a T-cell lymphoma.

Acknowledgmentszz

The participants and Federal Practitioner would like to thank Susan Thornton, CEO of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation for helping to arrange this roundtable discussion.

1. Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-1714.

2. Imam MH, Shenoy PJ, Flowers CR, Phillips A, Lechowicz MJ. Incidence and survival patterns of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(4):752-759.

3. Del Guzzo C, Levin A, Dana A, et al. The incidence of cutaneous T-Cell lymphoma in the veteran population. Abstract 133. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(5 suppl 1):S24.

4. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Cocco P, La Vecchia C, et al. Medical history, lifestyle, family history, and occupational risk factors for mycosis fungoides and Sèzary syndrome: the InterLymph Non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes project. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;48:98-105.

5. Scarisbrick JJ, Quaglino P, Prince HM, et al. The PROCLIPI international registry of early-stage mycosis fungoides identifies substantial diagnostic delay in most patients. Br J Dermatol. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

6. Thurber SE, Zhang B, Kim YH, Schrijver I, Zehnder J, Kohler S. T-cell clonality analysis in biopsy specimens from two different skin sites shows high specificity in the diagnosis of patients with suggested mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):782-790.

7. Kim YH, Jensen RA, Watanabe GL, Varghese A, Hoppe RT. Clinical stage IA (limited patch and plaque) mycosis fungoides. A long-term outcome analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(11):1309-1313.

8. Benton EC, Crichton S, Talpur R, et al. A cutaneous lymphoma international prognostic index (CLIPi) for mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 2013; 49(13):2859-2868.

9. Battistella M, Sallé de Chou C, de Bazelaire C, et al. Lymph node image-guided core-needle biopsy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma staging. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(6):1397-1400.

10. Johnson WT, Mukherji R, Kartan S, Nikbakht N, Porcu P, Alpdogan O. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in advanced stage mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a concise review. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(1):12.

11. Johnson WT, Mukherji R, Kartan S, Nikbakht N, Porcu P, Alpdogan O. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in advanced stage mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a concise review. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(1):12.

12. Wilson LD, Jones GW, Kim D, et al. Experience with total skin electron beam therapy in combination with extracorporeal photopheresis in the management of patients with erythrodermic (T4) mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1 Pt 1):54-60.

John Zic, MD. Let’s start by defining cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) and how they differ from other non-Hodgkin lymphomas. We also should discuss classification, which can be very confusing and epidemiology as it relates to the veteran population. Then I think we should dive into challenges with diagnosis and when should a VA or any provider consider mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome—the 2 most common variants of CTCLs.

I like to define the primary CTCLs as malignancies of the T-cell where the primary organ of involvement is the skin. However, this disease can spread to lymph nodes and visceral organs and the blood compartment in more advanced patients. Alejandro, could you provide some highlights about how CTCLs are classified?

Alejandro Ariel Gru, MD. Lymphomas are divided in the general hematology/oncology practice as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Traditionally all lymphomas that occur on the skin are non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes. That has specific connotations in terms of diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Because the T cells are one of the main residents of the subtypes of lymphocytes you encounter on the skin, most lymphomas that occur on the skin are derived of T-cell origin. B-cell lymphomas, in general, tend to be relatively uncommon or more infrequent.

There are 3 main subtypes of CTCL that present on the skin.1 MF is, by far, the most common subtype of CTCL. The disease tends to present in patients who are usually aged > 60 years and is more frequent in white males. It’s a lymphoma that is particularly relevant to the veteran population. The second subtype has many similarities to MF but shows substantial peripheral blood involvement and is referred to as Sézary syndrome. The third group is encompassed under the term CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. This group includes 2 main subtypes: primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma and lymphomatoid papulosis. Some cases of MF develop progression to what we call large cell transformation, which implies cytologic transformation to a more aggressive lymphoma.

There are other cutaneous lymphomas that are far less common. Some are indolent and others can be more aggressive, but they represent < 5% of all CTCL subtypes.

Lauren Pinter-Brown, MD. That was a great summary about these non-Hodgkin lymphomas. In the veteran population, it’s wise to remember that there are many kinds of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Because of the action that they have seen, some people, such as Vietnam veterans, might be more susceptible to non-Hodgkin lymphomas than others.

John Zic. That’s a good point because certainly non-Hodgkin lymphomas are listed as one of the potential disease associations with exposure to Agent Orange.

I’d like to move on to epidemiology and the incidence of MF and Sézary syndrome. An article that came out of Emory University in 2013 is one of the more up-to-date articles to examine the incidence and survival patterns of CTCL.2 The authors looked at patients from 2005 to 2008 and identified 2,273 patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. They estimated that the incidence of MF in the US population is about 5.5 per 1,000,000 per year, which certainly makes it a rare disease. The incidence of Sézary syndrome was 0.1 per 1,000,000 per year, which comes out to about 1 per 10 million per year.

However, the MF incidence needs to be contrasted to the estimated incidence in the veteran population. In 2016, Larisa Geskin and colleagues from Columbia University and the Bronx US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center examined the VA database of patients with diagnoses of MF and Sézary syndrome.3 They combined them, but I have a feeling that the amount of Sézary syndrome patients was much less than those with MF. They estimated an incidence per million of 62 to 79 cases per 1,000,000 per year. The conclusion of Dr. Geskin’s study stated that the incidence of CTCL in the veteran population appears to be anywhere from 6 to 8 times higher. But if we use the most recent US incidence rates, it’s more than 10 times higher.

Those of you who have worked with veterans, either at the VA or in your private practice, do you have any ideas about why that might be?

Lauren Pinter-Brown. As you previously discussed, this is an illness of older people, and Vietnam veterans now are in their 60s and 70s. They may account for a lot of these diagnoses.