User login

Safe to skip radiotherapy with negative PET in Hodgkin lymphoma

and can skip the additional radiotherapy that is normally included in the combined modality treatment, say experts reporting the final results from an international phase 3 randomized trial dubbed HD17.

“Most patients with this disease will not need radiotherapy any longer,” concluded first author Peter Borchmann, MD, assistant medical director in the department of hematology/oncology at the University Hospital Cologne (Germany).

Dr. Borchmann was speaking online as part of the virtual edition of the European Hematology Association 25th Annual Congress 2020.

“Importantly, the mortality of patients with early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma in the HD17 study did not differ from the normal healthy German population, and this is the first time we have had this finding in one of our studies,” he emphasized.

Dr. Borchmann added that positron emission tomography imaging is key in deciding which patients can skip radiation.

“We conclude from the HD17 trial that the combined modality concept can and should be replaced by a PET-guided omission of radiotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma,” he said.

“The vast majority of early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma patients can be treated with the brief and highly effective 2+2 chemotherapy alone,” he added.

Therefore, he continued, “PET-guided 2+2 chemotherapy is the new standard of care for the German Hodgkin study group,” which conducted the trial.

The use of both chemotherapy and radiation has long been a standard approach to treatment, and this combined modality treatment is highly effective, Dr. Borchmann explained. But it can cause long-term damage, and the known longer-term negative effects of radiotherapy, such as cardiovascular disease and second malignancies, are a particular concern because patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma are relatively young, with a median age of around 30 years at disease onset.

An expert approached for comment said that the momentum to skip radiotherapy when possible is an ongoing issue, and importantly, this study adds to those efforts.

“The treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma has moved for many years now to less radiation therapy, and this trend will continue with the results of this study,” commented John G. Gribben, MD, director of the Stem Cell Transplantation Program and medical director of the North East London Cancer Research Network Centre at Barts Cancer Center of Excellence and the London School of Medicine.

“We have moved to lower doses and involved fields with the intent of decreasing toxicity, and particularly long-term toxicity from radiotherapy,” he said in an interview.

HD17 study details

For the multicenter, phase 3 HD17 trial, Dr. Borchmann and colleagues turned to PET to identify patients who had and had not responded well to chemotherapy (PET negative and PET positive) and to determine if those who had responded well could safely avoid radiotherapy without compromising efficacy.

“We wanted to determine if we could reduce the treatment intensity by omission of radiotherapy in patients who respond very well to the systemic treatment, so who have a complete metabolic remission after the chemotherapy,” Dr. Borchmann said.

The 2+2 treatment approach includes two cycles of eBEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) and two subsequent cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine).

The trial enrolled 1,100 patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma between January 2012 and March 2017. Of these, 979 patients had confirmed PET results, with 651 (66.5%) found to be PET negative, defined as having a Deauville score (DS) of less than 3 (DS3); 238 (24.3%) were DS3, and 90 (9.2%) were DS4.

The study met its primary endpoint of noninferiority in progression-free survival (PFS) at 5 years, with a PFS of 95.1% in the PET-guided group (n = 447), compared with 97.3% in the standard combined-modality treatment group (n = 428), over a median observation time of 45 months, for a difference of 2.2% (P = .12).

“We found that the survival levels were very high, and we can safely conclude the noninferiority of the PET-guided approach in PET-negative patients,” Dr. Borchmann said.

A further analysis showed that the 597 PET-negative patients who did not receive radiotherapy because of their PET status had 5-year PFS that was noninferior to the combined modality group (95.9% vs. 97.7%, respectively; P = .20).

And among 646 patients who received the 2+2 regimen plus radiotherapy, of those confirmed as PET positive (n = 328), the estimated 5-year PFS was significantly lower (94.2%), compared with those determined to be PET negative (n = 318; 97.6%; hazard ratio, 3.03).

A cut-off of DS4 for positivity was associated with a stronger effect, with a lower estimated 5-year PFS of 81.6% vs. 98.8% for DS3 patients and 97.6% for DS less than 3 (P < .0001).

“Only DS4 has a prognostic impact, but not DS3,” Dr. Borchmann said. “DS4 positivity indicates a relevant risk for treatment failure, however, there are few patients in this risk group (9.2% in this trial).”

The 5-year overall survival rates in an intent-to-treat analysis were 98.8% in the standard combined modality group and 98.4% in the PET-guided group.

With a median observation time of 47 months, there have been 10 fatal events in the trial out of 1,100 patients, including two Hodgkin lymphoma-related events and one treatment-related death.

“Overall, Hodgkin lymphoma or treatment-related mortality rates were extremely low,” Dr. Borchmann said.

The study was funded by Deutsche Krebshilfe. Dr. Borchmann and Dr. Gribben have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

and can skip the additional radiotherapy that is normally included in the combined modality treatment, say experts reporting the final results from an international phase 3 randomized trial dubbed HD17.

“Most patients with this disease will not need radiotherapy any longer,” concluded first author Peter Borchmann, MD, assistant medical director in the department of hematology/oncology at the University Hospital Cologne (Germany).

Dr. Borchmann was speaking online as part of the virtual edition of the European Hematology Association 25th Annual Congress 2020.

“Importantly, the mortality of patients with early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma in the HD17 study did not differ from the normal healthy German population, and this is the first time we have had this finding in one of our studies,” he emphasized.

Dr. Borchmann added that positron emission tomography imaging is key in deciding which patients can skip radiation.

“We conclude from the HD17 trial that the combined modality concept can and should be replaced by a PET-guided omission of radiotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma,” he said.

“The vast majority of early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma patients can be treated with the brief and highly effective 2+2 chemotherapy alone,” he added.

Therefore, he continued, “PET-guided 2+2 chemotherapy is the new standard of care for the German Hodgkin study group,” which conducted the trial.

The use of both chemotherapy and radiation has long been a standard approach to treatment, and this combined modality treatment is highly effective, Dr. Borchmann explained. But it can cause long-term damage, and the known longer-term negative effects of radiotherapy, such as cardiovascular disease and second malignancies, are a particular concern because patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma are relatively young, with a median age of around 30 years at disease onset.

An expert approached for comment said that the momentum to skip radiotherapy when possible is an ongoing issue, and importantly, this study adds to those efforts.

“The treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma has moved for many years now to less radiation therapy, and this trend will continue with the results of this study,” commented John G. Gribben, MD, director of the Stem Cell Transplantation Program and medical director of the North East London Cancer Research Network Centre at Barts Cancer Center of Excellence and the London School of Medicine.

“We have moved to lower doses and involved fields with the intent of decreasing toxicity, and particularly long-term toxicity from radiotherapy,” he said in an interview.

HD17 study details

For the multicenter, phase 3 HD17 trial, Dr. Borchmann and colleagues turned to PET to identify patients who had and had not responded well to chemotherapy (PET negative and PET positive) and to determine if those who had responded well could safely avoid radiotherapy without compromising efficacy.

“We wanted to determine if we could reduce the treatment intensity by omission of radiotherapy in patients who respond very well to the systemic treatment, so who have a complete metabolic remission after the chemotherapy,” Dr. Borchmann said.

The 2+2 treatment approach includes two cycles of eBEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) and two subsequent cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine).

The trial enrolled 1,100 patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma between January 2012 and March 2017. Of these, 979 patients had confirmed PET results, with 651 (66.5%) found to be PET negative, defined as having a Deauville score (DS) of less than 3 (DS3); 238 (24.3%) were DS3, and 90 (9.2%) were DS4.

The study met its primary endpoint of noninferiority in progression-free survival (PFS) at 5 years, with a PFS of 95.1% in the PET-guided group (n = 447), compared with 97.3% in the standard combined-modality treatment group (n = 428), over a median observation time of 45 months, for a difference of 2.2% (P = .12).

“We found that the survival levels were very high, and we can safely conclude the noninferiority of the PET-guided approach in PET-negative patients,” Dr. Borchmann said.

A further analysis showed that the 597 PET-negative patients who did not receive radiotherapy because of their PET status had 5-year PFS that was noninferior to the combined modality group (95.9% vs. 97.7%, respectively; P = .20).

And among 646 patients who received the 2+2 regimen plus radiotherapy, of those confirmed as PET positive (n = 328), the estimated 5-year PFS was significantly lower (94.2%), compared with those determined to be PET negative (n = 318; 97.6%; hazard ratio, 3.03).

A cut-off of DS4 for positivity was associated with a stronger effect, with a lower estimated 5-year PFS of 81.6% vs. 98.8% for DS3 patients and 97.6% for DS less than 3 (P < .0001).

“Only DS4 has a prognostic impact, but not DS3,” Dr. Borchmann said. “DS4 positivity indicates a relevant risk for treatment failure, however, there are few patients in this risk group (9.2% in this trial).”

The 5-year overall survival rates in an intent-to-treat analysis were 98.8% in the standard combined modality group and 98.4% in the PET-guided group.

With a median observation time of 47 months, there have been 10 fatal events in the trial out of 1,100 patients, including two Hodgkin lymphoma-related events and one treatment-related death.

“Overall, Hodgkin lymphoma or treatment-related mortality rates were extremely low,” Dr. Borchmann said.

The study was funded by Deutsche Krebshilfe. Dr. Borchmann and Dr. Gribben have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

and can skip the additional radiotherapy that is normally included in the combined modality treatment, say experts reporting the final results from an international phase 3 randomized trial dubbed HD17.

“Most patients with this disease will not need radiotherapy any longer,” concluded first author Peter Borchmann, MD, assistant medical director in the department of hematology/oncology at the University Hospital Cologne (Germany).

Dr. Borchmann was speaking online as part of the virtual edition of the European Hematology Association 25th Annual Congress 2020.

“Importantly, the mortality of patients with early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma in the HD17 study did not differ from the normal healthy German population, and this is the first time we have had this finding in one of our studies,” he emphasized.

Dr. Borchmann added that positron emission tomography imaging is key in deciding which patients can skip radiation.

“We conclude from the HD17 trial that the combined modality concept can and should be replaced by a PET-guided omission of radiotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma,” he said.

“The vast majority of early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma patients can be treated with the brief and highly effective 2+2 chemotherapy alone,” he added.

Therefore, he continued, “PET-guided 2+2 chemotherapy is the new standard of care for the German Hodgkin study group,” which conducted the trial.

The use of both chemotherapy and radiation has long been a standard approach to treatment, and this combined modality treatment is highly effective, Dr. Borchmann explained. But it can cause long-term damage, and the known longer-term negative effects of radiotherapy, such as cardiovascular disease and second malignancies, are a particular concern because patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma are relatively young, with a median age of around 30 years at disease onset.

An expert approached for comment said that the momentum to skip radiotherapy when possible is an ongoing issue, and importantly, this study adds to those efforts.

“The treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma has moved for many years now to less radiation therapy, and this trend will continue with the results of this study,” commented John G. Gribben, MD, director of the Stem Cell Transplantation Program and medical director of the North East London Cancer Research Network Centre at Barts Cancer Center of Excellence and the London School of Medicine.

“We have moved to lower doses and involved fields with the intent of decreasing toxicity, and particularly long-term toxicity from radiotherapy,” he said in an interview.

HD17 study details

For the multicenter, phase 3 HD17 trial, Dr. Borchmann and colleagues turned to PET to identify patients who had and had not responded well to chemotherapy (PET negative and PET positive) and to determine if those who had responded well could safely avoid radiotherapy without compromising efficacy.

“We wanted to determine if we could reduce the treatment intensity by omission of radiotherapy in patients who respond very well to the systemic treatment, so who have a complete metabolic remission after the chemotherapy,” Dr. Borchmann said.

The 2+2 treatment approach includes two cycles of eBEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) and two subsequent cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine).

The trial enrolled 1,100 patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma between January 2012 and March 2017. Of these, 979 patients had confirmed PET results, with 651 (66.5%) found to be PET negative, defined as having a Deauville score (DS) of less than 3 (DS3); 238 (24.3%) were DS3, and 90 (9.2%) were DS4.

The study met its primary endpoint of noninferiority in progression-free survival (PFS) at 5 years, with a PFS of 95.1% in the PET-guided group (n = 447), compared with 97.3% in the standard combined-modality treatment group (n = 428), over a median observation time of 45 months, for a difference of 2.2% (P = .12).

“We found that the survival levels were very high, and we can safely conclude the noninferiority of the PET-guided approach in PET-negative patients,” Dr. Borchmann said.

A further analysis showed that the 597 PET-negative patients who did not receive radiotherapy because of their PET status had 5-year PFS that was noninferior to the combined modality group (95.9% vs. 97.7%, respectively; P = .20).

And among 646 patients who received the 2+2 regimen plus radiotherapy, of those confirmed as PET positive (n = 328), the estimated 5-year PFS was significantly lower (94.2%), compared with those determined to be PET negative (n = 318; 97.6%; hazard ratio, 3.03).

A cut-off of DS4 for positivity was associated with a stronger effect, with a lower estimated 5-year PFS of 81.6% vs. 98.8% for DS3 patients and 97.6% for DS less than 3 (P < .0001).

“Only DS4 has a prognostic impact, but not DS3,” Dr. Borchmann said. “DS4 positivity indicates a relevant risk for treatment failure, however, there are few patients in this risk group (9.2% in this trial).”

The 5-year overall survival rates in an intent-to-treat analysis were 98.8% in the standard combined modality group and 98.4% in the PET-guided group.

With a median observation time of 47 months, there have been 10 fatal events in the trial out of 1,100 patients, including two Hodgkin lymphoma-related events and one treatment-related death.

“Overall, Hodgkin lymphoma or treatment-related mortality rates were extremely low,” Dr. Borchmann said.

The study was funded by Deutsche Krebshilfe. Dr. Borchmann and Dr. Gribben have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

American Cancer Society update: ‘It is best not to drink alcohol’

In its updated cancer prevention guidelines, the American Cancer Society now recommends that “it is best not to drink alcohol.”

Previously, ACS suggested that, for those who consume alcoholic beverages, intake should be no more than one drink per day for women or two per day for men. That recommendation is still in place, but is now accompanied by this new, stronger directive.

The revised guidelines also place more emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat and highly processed foods, and on increasing physical activity.

But importantly, there is also a call for action from public, private, and community organizations to work to together to increase access to affordable, nutritious foods and physical activity.

“Making healthy choices can be challenging for many, and there are strategies included in the guidelines that communities can undertake to help reduce barriers to eating well and physical activity,” said Laura Makaroff, DO, American Cancer Society senior vice president. “Individual choice is an important part of a healthy lifestyle, but having the right policies and environmental factors to break down these barriers is also important, and that is something that clinicians can support.”

The guidelines were published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

The link between cancer and lifestyle factors has long been established, and for the past 4 decades, both government and leading nonprofit health organizations, including the ACS and the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR), have released cancer prevention guidelines and recommendations that focus on managing weight, diet, physical activity, and alcohol consumption.

In 2012, the ACS issued guidelines on diet and physical activity, and their current guideline is largely based on the WCRF/AICR systematic reviews and Continuous Update Project reports, which were last updated in 2018. The ACS guidelines also incorporated systematic reviews conducted by the International Agency on Cancer Research (IARC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services (USDA/HHS) and other analyses that were published since the WCRF/AICR recommendations were released.

Emphasis on three areas

The differences between the old guidelines and the update do not differ dramatically, but Makaroff highlighted a few areas that have increased emphasis.

Time spent being physically active is critical. The recommendation has changed to encourage adults to engage in 150-300 minutes (2.5-5 hours) of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 75-150 minutes (1.25-2.5 hours) of vigorous-intensity physical activity, or an equivalent combination, per week. Achieving or exceeding the upper limit of 300 minutes is optimal.

“That is more than what we have recommended in the past, along with the continued message that children and adolescents engage in at least 1 hour of moderate- or vigorous-intensity activity each day,” she told Medscape Medical News.

The ACS has also increased emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat. “This is part of a healthy eating pattern and making sure that people are eating food that is high in nutrients that help achieve and maintain a healthy body weight,” said Makaroff.

A healthy diet should include a variety of dark green, red, and orange vegetables; fiber-rich legumes; and fruits with a variety of colors and whole grains, according to the guidelines. Sugar-sweetened beverages, highly processed foods, and refined grain products should be limited or avoided.

The revised dietary recommendations reflect a shift from a “reductionist or nutrient-centric” approach to one that is more “holistic” and that focuses on dietary patterns. In contrast to a focus on individual nutrients and bioactive compounds, the new approach is more consistent with what and how people actually eat, ACS points out.

The third area that Makaroff highlighted is alcohol, where the recommendation is to avoid or limit consumption. “The current update says not to drink alcohol, which is in line with the scientific evidence, but for those people who choose to drink alcohol, to limit it to one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men.”

Thus, the change here is that the previous guideline only recommended limiting alcohol consumption, while the update suggests that, optimally, it should be avoided completely.

The ACS has also called for community involvement to help implement these goals: “Public, private, and community organizations should work collaboratively at national, state, and local levels to develop, advocate for, and implement policy and environmental changes that increase access to affordable, nutritious foods; provide safe, enjoyable, and accessible opportunities for physical activity; and limit alcohol for all individuals.”

No smoking guns

Commenting on the guidelines, Steven K. Clinton, MD, PhD, associate director of the Center for Advanced Functional Foods Research and Entrepreneurship at the Ohio State University, Columbus, explained that he didn’t view the change in alcohol as that much of an evolution. “It’s been 8 years since they revised their overall guidelines, and during that time frame, there has been an enormous growth in the evidence that has been used by many organizations,” he said.

Clinton noted that the guidelines are consistent with the whole body of current scientific literature. “It’s very easy to go to the document and look for the ‘smoking gun’ – but the smoking gun is really not one thing,” he said. “It’s a pattern, and what dietitians and nutritionists are telling people is that you need to orchestrate a healthy lifestyle and diet, with a diet that has a foundation of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and modest intake of refined grains and meat. You are orchestrating an entire pattern to get the maximum benefit.”

Makaroff is an employee of the ACS. Clinton has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In its updated cancer prevention guidelines, the American Cancer Society now recommends that “it is best not to drink alcohol.”

Previously, ACS suggested that, for those who consume alcoholic beverages, intake should be no more than one drink per day for women or two per day for men. That recommendation is still in place, but is now accompanied by this new, stronger directive.

The revised guidelines also place more emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat and highly processed foods, and on increasing physical activity.

But importantly, there is also a call for action from public, private, and community organizations to work to together to increase access to affordable, nutritious foods and physical activity.

“Making healthy choices can be challenging for many, and there are strategies included in the guidelines that communities can undertake to help reduce barriers to eating well and physical activity,” said Laura Makaroff, DO, American Cancer Society senior vice president. “Individual choice is an important part of a healthy lifestyle, but having the right policies and environmental factors to break down these barriers is also important, and that is something that clinicians can support.”

The guidelines were published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

The link between cancer and lifestyle factors has long been established, and for the past 4 decades, both government and leading nonprofit health organizations, including the ACS and the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR), have released cancer prevention guidelines and recommendations that focus on managing weight, diet, physical activity, and alcohol consumption.

In 2012, the ACS issued guidelines on diet and physical activity, and their current guideline is largely based on the WCRF/AICR systematic reviews and Continuous Update Project reports, which were last updated in 2018. The ACS guidelines also incorporated systematic reviews conducted by the International Agency on Cancer Research (IARC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services (USDA/HHS) and other analyses that were published since the WCRF/AICR recommendations were released.

Emphasis on three areas

The differences between the old guidelines and the update do not differ dramatically, but Makaroff highlighted a few areas that have increased emphasis.

Time spent being physically active is critical. The recommendation has changed to encourage adults to engage in 150-300 minutes (2.5-5 hours) of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 75-150 minutes (1.25-2.5 hours) of vigorous-intensity physical activity, or an equivalent combination, per week. Achieving or exceeding the upper limit of 300 minutes is optimal.

“That is more than what we have recommended in the past, along with the continued message that children and adolescents engage in at least 1 hour of moderate- or vigorous-intensity activity each day,” she told Medscape Medical News.

The ACS has also increased emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat. “This is part of a healthy eating pattern and making sure that people are eating food that is high in nutrients that help achieve and maintain a healthy body weight,” said Makaroff.

A healthy diet should include a variety of dark green, red, and orange vegetables; fiber-rich legumes; and fruits with a variety of colors and whole grains, according to the guidelines. Sugar-sweetened beverages, highly processed foods, and refined grain products should be limited or avoided.

The revised dietary recommendations reflect a shift from a “reductionist or nutrient-centric” approach to one that is more “holistic” and that focuses on dietary patterns. In contrast to a focus on individual nutrients and bioactive compounds, the new approach is more consistent with what and how people actually eat, ACS points out.

The third area that Makaroff highlighted is alcohol, where the recommendation is to avoid or limit consumption. “The current update says not to drink alcohol, which is in line with the scientific evidence, but for those people who choose to drink alcohol, to limit it to one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men.”

Thus, the change here is that the previous guideline only recommended limiting alcohol consumption, while the update suggests that, optimally, it should be avoided completely.

The ACS has also called for community involvement to help implement these goals: “Public, private, and community organizations should work collaboratively at national, state, and local levels to develop, advocate for, and implement policy and environmental changes that increase access to affordable, nutritious foods; provide safe, enjoyable, and accessible opportunities for physical activity; and limit alcohol for all individuals.”

No smoking guns

Commenting on the guidelines, Steven K. Clinton, MD, PhD, associate director of the Center for Advanced Functional Foods Research and Entrepreneurship at the Ohio State University, Columbus, explained that he didn’t view the change in alcohol as that much of an evolution. “It’s been 8 years since they revised their overall guidelines, and during that time frame, there has been an enormous growth in the evidence that has been used by many organizations,” he said.

Clinton noted that the guidelines are consistent with the whole body of current scientific literature. “It’s very easy to go to the document and look for the ‘smoking gun’ – but the smoking gun is really not one thing,” he said. “It’s a pattern, and what dietitians and nutritionists are telling people is that you need to orchestrate a healthy lifestyle and diet, with a diet that has a foundation of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and modest intake of refined grains and meat. You are orchestrating an entire pattern to get the maximum benefit.”

Makaroff is an employee of the ACS. Clinton has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In its updated cancer prevention guidelines, the American Cancer Society now recommends that “it is best not to drink alcohol.”

Previously, ACS suggested that, for those who consume alcoholic beverages, intake should be no more than one drink per day for women or two per day for men. That recommendation is still in place, but is now accompanied by this new, stronger directive.

The revised guidelines also place more emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat and highly processed foods, and on increasing physical activity.

But importantly, there is also a call for action from public, private, and community organizations to work to together to increase access to affordable, nutritious foods and physical activity.

“Making healthy choices can be challenging for many, and there are strategies included in the guidelines that communities can undertake to help reduce barriers to eating well and physical activity,” said Laura Makaroff, DO, American Cancer Society senior vice president. “Individual choice is an important part of a healthy lifestyle, but having the right policies and environmental factors to break down these barriers is also important, and that is something that clinicians can support.”

The guidelines were published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

The link between cancer and lifestyle factors has long been established, and for the past 4 decades, both government and leading nonprofit health organizations, including the ACS and the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR), have released cancer prevention guidelines and recommendations that focus on managing weight, diet, physical activity, and alcohol consumption.

In 2012, the ACS issued guidelines on diet and physical activity, and their current guideline is largely based on the WCRF/AICR systematic reviews and Continuous Update Project reports, which were last updated in 2018. The ACS guidelines also incorporated systematic reviews conducted by the International Agency on Cancer Research (IARC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services (USDA/HHS) and other analyses that were published since the WCRF/AICR recommendations were released.

Emphasis on three areas

The differences between the old guidelines and the update do not differ dramatically, but Makaroff highlighted a few areas that have increased emphasis.

Time spent being physically active is critical. The recommendation has changed to encourage adults to engage in 150-300 minutes (2.5-5 hours) of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 75-150 minutes (1.25-2.5 hours) of vigorous-intensity physical activity, or an equivalent combination, per week. Achieving or exceeding the upper limit of 300 minutes is optimal.

“That is more than what we have recommended in the past, along with the continued message that children and adolescents engage in at least 1 hour of moderate- or vigorous-intensity activity each day,” she told Medscape Medical News.

The ACS has also increased emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat. “This is part of a healthy eating pattern and making sure that people are eating food that is high in nutrients that help achieve and maintain a healthy body weight,” said Makaroff.

A healthy diet should include a variety of dark green, red, and orange vegetables; fiber-rich legumes; and fruits with a variety of colors and whole grains, according to the guidelines. Sugar-sweetened beverages, highly processed foods, and refined grain products should be limited or avoided.

The revised dietary recommendations reflect a shift from a “reductionist or nutrient-centric” approach to one that is more “holistic” and that focuses on dietary patterns. In contrast to a focus on individual nutrients and bioactive compounds, the new approach is more consistent with what and how people actually eat, ACS points out.

The third area that Makaroff highlighted is alcohol, where the recommendation is to avoid or limit consumption. “The current update says not to drink alcohol, which is in line with the scientific evidence, but for those people who choose to drink alcohol, to limit it to one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men.”

Thus, the change here is that the previous guideline only recommended limiting alcohol consumption, while the update suggests that, optimally, it should be avoided completely.

The ACS has also called for community involvement to help implement these goals: “Public, private, and community organizations should work collaboratively at national, state, and local levels to develop, advocate for, and implement policy and environmental changes that increase access to affordable, nutritious foods; provide safe, enjoyable, and accessible opportunities for physical activity; and limit alcohol for all individuals.”

No smoking guns

Commenting on the guidelines, Steven K. Clinton, MD, PhD, associate director of the Center for Advanced Functional Foods Research and Entrepreneurship at the Ohio State University, Columbus, explained that he didn’t view the change in alcohol as that much of an evolution. “It’s been 8 years since they revised their overall guidelines, and during that time frame, there has been an enormous growth in the evidence that has been used by many organizations,” he said.

Clinton noted that the guidelines are consistent with the whole body of current scientific literature. “It’s very easy to go to the document and look for the ‘smoking gun’ – but the smoking gun is really not one thing,” he said. “It’s a pattern, and what dietitians and nutritionists are telling people is that you need to orchestrate a healthy lifestyle and diet, with a diet that has a foundation of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and modest intake of refined grains and meat. You are orchestrating an entire pattern to get the maximum benefit.”

Makaroff is an employee of the ACS. Clinton has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Can an app guide cancer treatment decisions during the pandemic?

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early April, as the COVID-19 surge was bearing down on New York City, those treatment decisions were “a juggling act every single day,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, a radiation oncologist from New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

Eventually, a glut of guidelines, recommendations, and expert opinions aimed at helping oncologists emerged. The tools help navigate the complicated risk-benefit analysis of their patient’s risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and delaying therapy.

Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help?

Three-Tier Systems Are Not Very Sophisticated

OncCOVID, a free tool that was launched May 26 by the University of Michigan, allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care.

Combining these personal details with data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registry and the National Cancer Database, the Michigan app then estimates a patient’s 5- or 10-year survival with immediate vs delayed treatment and weighs that against their risk for COVID-19 using data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

“We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine.

Spratt explained that almost every organization, professional society, and government has created something like a three-tier system. Tier 1 represents urgent cases and patients who need immediate treatment. For tier 2, treatment can be delayed weeks or a month, and with tier 3, it can be delayed until the pandemic is over or it’s deemed safe.

“[This system] sounds good at first glance, but in cancer, we’re always talking about personalized medicine, and it’s mind-blowing that these tier systems are only based on urgency and prognosis,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Spratt offered an example. Consider a patient with a very aggressive brain tumor ― that patient is in tier 1 and should undergo treatment immediately. But will the treatment actually help? And how helpful would the procedure be if, say, the patient is 80 years old and, if infected, would have a 30% to 50% chance of dying from the coronavirus?

“If the model says this guy has a 5% harm and this one has 30% harm, you can use that to help prioritize,” summarized Spratt.

The app can generate risk estimates for patients living anywhere in the world and has already been accessed by people from 37 countries. However, Spratt cautions that it is primarily “designed and calibrated for the US.

“The estimates are based on very large US registries, and though it’s probably somewhat similar across much of the world, there’s probably certain cancer types that are more region specific ― especially something like stomach cancer or certain types of head and neck cancer in parts of Asia, for example,” he said.

Although the app’s COVID-19 data are specific to the county level in the United States, elsewhere in the world, it is only country specific.

“We’re using the best data we have for coronavirus, but everyone knows we still have large data gaps,” he acknowledged.

How Accurate?

Asked to comment on the app, Richard Bleicher, MD, leader of the Breast Cancer Program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, praised the effort and the goal but had some concerns.

“Several questions arise, most important of which is, How accurate is this, and how has this been validated, if at all ― especially as it is too soon to see the outcomes of patients affected in this pandemic?” he told Medscape Medical News.

“We are imposing delays on a broad scale because of the coronavirus, and we are getting continuously changing data as we test more patients. But both situations are novel and may not be accurately represented by the data being pulled, because the datasets use patients from a few years ago, and confounders in these datasets may not apply to this situation,” Bleicher continued.

Although acknowledging the “value in delineating the risk of dying from cancer vs the risk of dying from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Bleicher urged caution in using the tool to make individual patient decisions.

“We need to remember that the best of modeling ... can be wildly inaccurate and needs to be validated using patients having the circumstances in question. ... This won’t be possible until long after the pandemic is completed, and so the model’s accuracy remains unknown.”

That sentiment was echoed by Giampaolo Bianchini, MD, head of the Breast Cancer Group, Department of Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Raffaele, in Milan, Italy.

“Arbitrarily postponing and modifying treatment strategies including surgery, radiation therapy, and medical therapy without properly balancing the risk/benefit ratio may lead to significantly worse cancer-related outcomes, which largely exceed the actual risks for COVID,” he wrote in an email.

“The OncCOVID app is a remarkable attempt to fill the gap between perception and estimation,” he said. The app provides side by side the COVID-19 risk estimation and the consequences of arbitrary deviation from the standard of care, observed Bianchini.

However, he pointed out weaknesses, including the fact that the “data generated in literature are not always of high quality and do not take into consideration relevant characteristics of the disease and treatment benefit. It should for sure be used, but then also interpreted with caution.”

Another Italian group responded more positively.

“In our opinion, it could be a useful tool for clinicians,” wrote colleagues Alessio Cortelinni and Giampiero Porzio, both medical oncologists at San Salvatore Hospital and the University of L’Aquila, in Italy. “This Web app might assist clinicians in balancing the risk/benefit ratio of being treated and/or access to the outpatient cancer center for each kind of patient (both early and advanced stages), in order to make a more tailored counseling,” they wrote in an email. “Importantly, the Web app might help those clinicians who work ‘alone,’ in peripheral centers, without resources, colleagues, and multidisciplinary tumor boards on whom they can rely.”

Bleicher, who was involved in the COVID-19 Breast Cancer Consortium’s recommendations for prioritizing breast cancer treatment, summarized that the app “may end up being close or accurate, but we won’t know except in hindsight.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early April, as the COVID-19 surge was bearing down on New York City, those treatment decisions were “a juggling act every single day,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, a radiation oncologist from New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

Eventually, a glut of guidelines, recommendations, and expert opinions aimed at helping oncologists emerged. The tools help navigate the complicated risk-benefit analysis of their patient’s risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and delaying therapy.

Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help?

Three-Tier Systems Are Not Very Sophisticated

OncCOVID, a free tool that was launched May 26 by the University of Michigan, allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care.

Combining these personal details with data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registry and the National Cancer Database, the Michigan app then estimates a patient’s 5- or 10-year survival with immediate vs delayed treatment and weighs that against their risk for COVID-19 using data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

“We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine.

Spratt explained that almost every organization, professional society, and government has created something like a three-tier system. Tier 1 represents urgent cases and patients who need immediate treatment. For tier 2, treatment can be delayed weeks or a month, and with tier 3, it can be delayed until the pandemic is over or it’s deemed safe.

“[This system] sounds good at first glance, but in cancer, we’re always talking about personalized medicine, and it’s mind-blowing that these tier systems are only based on urgency and prognosis,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Spratt offered an example. Consider a patient with a very aggressive brain tumor ― that patient is in tier 1 and should undergo treatment immediately. But will the treatment actually help? And how helpful would the procedure be if, say, the patient is 80 years old and, if infected, would have a 30% to 50% chance of dying from the coronavirus?

“If the model says this guy has a 5% harm and this one has 30% harm, you can use that to help prioritize,” summarized Spratt.

The app can generate risk estimates for patients living anywhere in the world and has already been accessed by people from 37 countries. However, Spratt cautions that it is primarily “designed and calibrated for the US.

“The estimates are based on very large US registries, and though it’s probably somewhat similar across much of the world, there’s probably certain cancer types that are more region specific ― especially something like stomach cancer or certain types of head and neck cancer in parts of Asia, for example,” he said.

Although the app’s COVID-19 data are specific to the county level in the United States, elsewhere in the world, it is only country specific.

“We’re using the best data we have for coronavirus, but everyone knows we still have large data gaps,” he acknowledged.

How Accurate?

Asked to comment on the app, Richard Bleicher, MD, leader of the Breast Cancer Program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, praised the effort and the goal but had some concerns.

“Several questions arise, most important of which is, How accurate is this, and how has this been validated, if at all ― especially as it is too soon to see the outcomes of patients affected in this pandemic?” he told Medscape Medical News.

“We are imposing delays on a broad scale because of the coronavirus, and we are getting continuously changing data as we test more patients. But both situations are novel and may not be accurately represented by the data being pulled, because the datasets use patients from a few years ago, and confounders in these datasets may not apply to this situation,” Bleicher continued.

Although acknowledging the “value in delineating the risk of dying from cancer vs the risk of dying from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Bleicher urged caution in using the tool to make individual patient decisions.

“We need to remember that the best of modeling ... can be wildly inaccurate and needs to be validated using patients having the circumstances in question. ... This won’t be possible until long after the pandemic is completed, and so the model’s accuracy remains unknown.”

That sentiment was echoed by Giampaolo Bianchini, MD, head of the Breast Cancer Group, Department of Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Raffaele, in Milan, Italy.

“Arbitrarily postponing and modifying treatment strategies including surgery, radiation therapy, and medical therapy without properly balancing the risk/benefit ratio may lead to significantly worse cancer-related outcomes, which largely exceed the actual risks for COVID,” he wrote in an email.

“The OncCOVID app is a remarkable attempt to fill the gap between perception and estimation,” he said. The app provides side by side the COVID-19 risk estimation and the consequences of arbitrary deviation from the standard of care, observed Bianchini.

However, he pointed out weaknesses, including the fact that the “data generated in literature are not always of high quality and do not take into consideration relevant characteristics of the disease and treatment benefit. It should for sure be used, but then also interpreted with caution.”

Another Italian group responded more positively.

“In our opinion, it could be a useful tool for clinicians,” wrote colleagues Alessio Cortelinni and Giampiero Porzio, both medical oncologists at San Salvatore Hospital and the University of L’Aquila, in Italy. “This Web app might assist clinicians in balancing the risk/benefit ratio of being treated and/or access to the outpatient cancer center for each kind of patient (both early and advanced stages), in order to make a more tailored counseling,” they wrote in an email. “Importantly, the Web app might help those clinicians who work ‘alone,’ in peripheral centers, without resources, colleagues, and multidisciplinary tumor boards on whom they can rely.”

Bleicher, who was involved in the COVID-19 Breast Cancer Consortium’s recommendations for prioritizing breast cancer treatment, summarized that the app “may end up being close or accurate, but we won’t know except in hindsight.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early April, as the COVID-19 surge was bearing down on New York City, those treatment decisions were “a juggling act every single day,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, a radiation oncologist from New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

Eventually, a glut of guidelines, recommendations, and expert opinions aimed at helping oncologists emerged. The tools help navigate the complicated risk-benefit analysis of their patient’s risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 and delaying therapy.

Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help?

Three-Tier Systems Are Not Very Sophisticated

OncCOVID, a free tool that was launched May 26 by the University of Michigan, allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care.

Combining these personal details with data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registry and the National Cancer Database, the Michigan app then estimates a patient’s 5- or 10-year survival with immediate vs delayed treatment and weighs that against their risk for COVID-19 using data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

“We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine.

Spratt explained that almost every organization, professional society, and government has created something like a three-tier system. Tier 1 represents urgent cases and patients who need immediate treatment. For tier 2, treatment can be delayed weeks or a month, and with tier 3, it can be delayed until the pandemic is over or it’s deemed safe.

“[This system] sounds good at first glance, but in cancer, we’re always talking about personalized medicine, and it’s mind-blowing that these tier systems are only based on urgency and prognosis,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Spratt offered an example. Consider a patient with a very aggressive brain tumor ― that patient is in tier 1 and should undergo treatment immediately. But will the treatment actually help? And how helpful would the procedure be if, say, the patient is 80 years old and, if infected, would have a 30% to 50% chance of dying from the coronavirus?

“If the model says this guy has a 5% harm and this one has 30% harm, you can use that to help prioritize,” summarized Spratt.

The app can generate risk estimates for patients living anywhere in the world and has already been accessed by people from 37 countries. However, Spratt cautions that it is primarily “designed and calibrated for the US.

“The estimates are based on very large US registries, and though it’s probably somewhat similar across much of the world, there’s probably certain cancer types that are more region specific ― especially something like stomach cancer or certain types of head and neck cancer in parts of Asia, for example,” he said.

Although the app’s COVID-19 data are specific to the county level in the United States, elsewhere in the world, it is only country specific.

“We’re using the best data we have for coronavirus, but everyone knows we still have large data gaps,” he acknowledged.

How Accurate?

Asked to comment on the app, Richard Bleicher, MD, leader of the Breast Cancer Program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, praised the effort and the goal but had some concerns.

“Several questions arise, most important of which is, How accurate is this, and how has this been validated, if at all ― especially as it is too soon to see the outcomes of patients affected in this pandemic?” he told Medscape Medical News.

“We are imposing delays on a broad scale because of the coronavirus, and we are getting continuously changing data as we test more patients. But both situations are novel and may not be accurately represented by the data being pulled, because the datasets use patients from a few years ago, and confounders in these datasets may not apply to this situation,” Bleicher continued.

Although acknowledging the “value in delineating the risk of dying from cancer vs the risk of dying from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Bleicher urged caution in using the tool to make individual patient decisions.

“We need to remember that the best of modeling ... can be wildly inaccurate and needs to be validated using patients having the circumstances in question. ... This won’t be possible until long after the pandemic is completed, and so the model’s accuracy remains unknown.”

That sentiment was echoed by Giampaolo Bianchini, MD, head of the Breast Cancer Group, Department of Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Raffaele, in Milan, Italy.

“Arbitrarily postponing and modifying treatment strategies including surgery, radiation therapy, and medical therapy without properly balancing the risk/benefit ratio may lead to significantly worse cancer-related outcomes, which largely exceed the actual risks for COVID,” he wrote in an email.

“The OncCOVID app is a remarkable attempt to fill the gap between perception and estimation,” he said. The app provides side by side the COVID-19 risk estimation and the consequences of arbitrary deviation from the standard of care, observed Bianchini.

However, he pointed out weaknesses, including the fact that the “data generated in literature are not always of high quality and do not take into consideration relevant characteristics of the disease and treatment benefit. It should for sure be used, but then also interpreted with caution.”

Another Italian group responded more positively.

“In our opinion, it could be a useful tool for clinicians,” wrote colleagues Alessio Cortelinni and Giampiero Porzio, both medical oncologists at San Salvatore Hospital and the University of L’Aquila, in Italy. “This Web app might assist clinicians in balancing the risk/benefit ratio of being treated and/or access to the outpatient cancer center for each kind of patient (both early and advanced stages), in order to make a more tailored counseling,” they wrote in an email. “Importantly, the Web app might help those clinicians who work ‘alone,’ in peripheral centers, without resources, colleagues, and multidisciplinary tumor boards on whom they can rely.”

Bleicher, who was involved in the COVID-19 Breast Cancer Consortium’s recommendations for prioritizing breast cancer treatment, summarized that the app “may end up being close or accurate, but we won’t know except in hindsight.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘A good and peaceful death’: Cancer hospice during the pandemic

Lillie Shockney, RN, MAS, a two-time breast cancer survivor and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland, mourns the many losses that her patients with advanced cancer now face in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in the void of the usual support networks and treatment plans, she sees the resurgence of something that has recently been crowded out: hospice.

The pandemic has forced patients and their physicians to reassess the risk/benefit balance of continuing or embarking on yet another cancer treatment.

“It’s one of the pearls that we will get out of this nightmare,” said Ms. Shockney, who recently retired as administrative director of the cancer survivorship programs at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Physicians have been taught to treat the disease – so as long as there’s a treatment they give another treatment,” she told Medscape Medical News during a Zoom call from her home. “But for some patients with advanced disease, those treatments were making them very sick, so they were trading longevity over quality of life.”

Of course, longevity has never been a guarantee with cancer treatment, and even less so now, with the risk of COVID-19.

“This is going to bring them to some hard discussions,” says Brenda Nevidjon, RN, MSN, chief executive officer at the Oncology Nursing Society.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are patients who are on third- and fourth-round treatment options that have very little evidence of prolonging life or quality of life,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Do we bring these people out of their home to a setting where there could be a fair number of COVID-positive patients? Do we expose them to that?”

Across the world, these dilemmas are pushing cancer specialists to initiate discussions of hospice sooner with patients who have advanced disease, and with more clarity than before.

One of the reasons such conversations have often been avoided is that the concept of hospice is generally misunderstood, said Ms. Shockney.

“Patients think ‘you’re giving up on me, you’ve abandoned me’, but hospice is all about preserving the remainder of their quality of life and letting them have time with family and time to fulfill those elements of experiencing a good and peaceful death,” she said.

Indeed, hospice is “a benefit meant for somebody with at least a 6-month horizon,” agrees Ms. Nevidjon. Yet the average length of hospice in the United States is just 5 days. “It’s at the very, very end, and yet for some of these patients the 6 months they could get in hospice might be a better quality of life than the 4 months on another whole plan of chemotherapy. I can’t imagine that on the backside of this pandemic we will not have learned and we won’t start to change practices around initiating more of these conversations.”

Silver lining of this pandemic?

It’s too early into the pandemic to have hard data on whether hospice uptake has increased, but “it’s encouraging to hear that hospice is being discussed and offered sooner as an alternative to that third- or fourth-round chemo,” said Lori Bishop, MHA, RN, vice president of palliative and advanced care at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

“I agree that improving informed-decision discussions and timely access to hospice is a silver lining of the pandemic,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But she points out that today’s hospice looks quite different than it did before the pandemic, with the immediate and very obvious difference being telehealth, which was not widely utilized previously.

In March, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded telehealth options for hospice providers, something that Ms. Bishop and other hospice providers hope will remain in place after the pandemic passes.

“Telehealth visits are offered to replace some in-home visits both to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19 and reduce the drain on personal protective equipment,” Bishop explained.

“In-patient hospice programs are also finding unique ways to provide support and connect patients to their loved ones: visitors are allowed but limited to one or two. Music and pet therapy are being provided through the window or virtually and devices such as iPads are being used to help patients connect with loved ones,” she said.

Telehealth links patients out of loneliness, but the one thing it cannot do is provide the comfort of touch – an important part of any hospice program.

“Hand-holding ... I miss that a lot,” says Ms. Shockney, her eyes filling with tears. “When you take somebody’s hand, you don’t even have to speak; that connection, and eye contact, is all you need to help that person emotionally heal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lillie Shockney, RN, MAS, a two-time breast cancer survivor and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland, mourns the many losses that her patients with advanced cancer now face in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in the void of the usual support networks and treatment plans, she sees the resurgence of something that has recently been crowded out: hospice.

The pandemic has forced patients and their physicians to reassess the risk/benefit balance of continuing or embarking on yet another cancer treatment.

“It’s one of the pearls that we will get out of this nightmare,” said Ms. Shockney, who recently retired as administrative director of the cancer survivorship programs at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Physicians have been taught to treat the disease – so as long as there’s a treatment they give another treatment,” she told Medscape Medical News during a Zoom call from her home. “But for some patients with advanced disease, those treatments were making them very sick, so they were trading longevity over quality of life.”

Of course, longevity has never been a guarantee with cancer treatment, and even less so now, with the risk of COVID-19.

“This is going to bring them to some hard discussions,” says Brenda Nevidjon, RN, MSN, chief executive officer at the Oncology Nursing Society.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are patients who are on third- and fourth-round treatment options that have very little evidence of prolonging life or quality of life,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Do we bring these people out of their home to a setting where there could be a fair number of COVID-positive patients? Do we expose them to that?”

Across the world, these dilemmas are pushing cancer specialists to initiate discussions of hospice sooner with patients who have advanced disease, and with more clarity than before.

One of the reasons such conversations have often been avoided is that the concept of hospice is generally misunderstood, said Ms. Shockney.

“Patients think ‘you’re giving up on me, you’ve abandoned me’, but hospice is all about preserving the remainder of their quality of life and letting them have time with family and time to fulfill those elements of experiencing a good and peaceful death,” she said.

Indeed, hospice is “a benefit meant for somebody with at least a 6-month horizon,” agrees Ms. Nevidjon. Yet the average length of hospice in the United States is just 5 days. “It’s at the very, very end, and yet for some of these patients the 6 months they could get in hospice might be a better quality of life than the 4 months on another whole plan of chemotherapy. I can’t imagine that on the backside of this pandemic we will not have learned and we won’t start to change practices around initiating more of these conversations.”

Silver lining of this pandemic?

It’s too early into the pandemic to have hard data on whether hospice uptake has increased, but “it’s encouraging to hear that hospice is being discussed and offered sooner as an alternative to that third- or fourth-round chemo,” said Lori Bishop, MHA, RN, vice president of palliative and advanced care at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

“I agree that improving informed-decision discussions and timely access to hospice is a silver lining of the pandemic,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But she points out that today’s hospice looks quite different than it did before the pandemic, with the immediate and very obvious difference being telehealth, which was not widely utilized previously.

In March, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded telehealth options for hospice providers, something that Ms. Bishop and other hospice providers hope will remain in place after the pandemic passes.

“Telehealth visits are offered to replace some in-home visits both to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19 and reduce the drain on personal protective equipment,” Bishop explained.

“In-patient hospice programs are also finding unique ways to provide support and connect patients to their loved ones: visitors are allowed but limited to one or two. Music and pet therapy are being provided through the window or virtually and devices such as iPads are being used to help patients connect with loved ones,” she said.

Telehealth links patients out of loneliness, but the one thing it cannot do is provide the comfort of touch – an important part of any hospice program.

“Hand-holding ... I miss that a lot,” says Ms. Shockney, her eyes filling with tears. “When you take somebody’s hand, you don’t even have to speak; that connection, and eye contact, is all you need to help that person emotionally heal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lillie Shockney, RN, MAS, a two-time breast cancer survivor and adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland, mourns the many losses that her patients with advanced cancer now face in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in the void of the usual support networks and treatment plans, she sees the resurgence of something that has recently been crowded out: hospice.

The pandemic has forced patients and their physicians to reassess the risk/benefit balance of continuing or embarking on yet another cancer treatment.

“It’s one of the pearls that we will get out of this nightmare,” said Ms. Shockney, who recently retired as administrative director of the cancer survivorship programs at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Physicians have been taught to treat the disease – so as long as there’s a treatment they give another treatment,” she told Medscape Medical News during a Zoom call from her home. “But for some patients with advanced disease, those treatments were making them very sick, so they were trading longevity over quality of life.”

Of course, longevity has never been a guarantee with cancer treatment, and even less so now, with the risk of COVID-19.

“This is going to bring them to some hard discussions,” says Brenda Nevidjon, RN, MSN, chief executive officer at the Oncology Nursing Society.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are patients who are on third- and fourth-round treatment options that have very little evidence of prolonging life or quality of life,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Do we bring these people out of their home to a setting where there could be a fair number of COVID-positive patients? Do we expose them to that?”

Across the world, these dilemmas are pushing cancer specialists to initiate discussions of hospice sooner with patients who have advanced disease, and with more clarity than before.

One of the reasons such conversations have often been avoided is that the concept of hospice is generally misunderstood, said Ms. Shockney.

“Patients think ‘you’re giving up on me, you’ve abandoned me’, but hospice is all about preserving the remainder of their quality of life and letting them have time with family and time to fulfill those elements of experiencing a good and peaceful death,” she said.

Indeed, hospice is “a benefit meant for somebody with at least a 6-month horizon,” agrees Ms. Nevidjon. Yet the average length of hospice in the United States is just 5 days. “It’s at the very, very end, and yet for some of these patients the 6 months they could get in hospice might be a better quality of life than the 4 months on another whole plan of chemotherapy. I can’t imagine that on the backside of this pandemic we will not have learned and we won’t start to change practices around initiating more of these conversations.”

Silver lining of this pandemic?

It’s too early into the pandemic to have hard data on whether hospice uptake has increased, but “it’s encouraging to hear that hospice is being discussed and offered sooner as an alternative to that third- or fourth-round chemo,” said Lori Bishop, MHA, RN, vice president of palliative and advanced care at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

“I agree that improving informed-decision discussions and timely access to hospice is a silver lining of the pandemic,” she told Medscape Medical News.

But she points out that today’s hospice looks quite different than it did before the pandemic, with the immediate and very obvious difference being telehealth, which was not widely utilized previously.

In March, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded telehealth options for hospice providers, something that Ms. Bishop and other hospice providers hope will remain in place after the pandemic passes.

“Telehealth visits are offered to replace some in-home visits both to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19 and reduce the drain on personal protective equipment,” Bishop explained.

“In-patient hospice programs are also finding unique ways to provide support and connect patients to their loved ones: visitors are allowed but limited to one or two. Music and pet therapy are being provided through the window or virtually and devices such as iPads are being used to help patients connect with loved ones,” she said.

Telehealth links patients out of loneliness, but the one thing it cannot do is provide the comfort of touch – an important part of any hospice program.

“Hand-holding ... I miss that a lot,” says Ms. Shockney, her eyes filling with tears. “When you take somebody’s hand, you don’t even have to speak; that connection, and eye contact, is all you need to help that person emotionally heal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

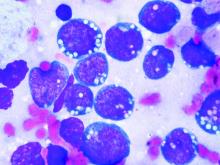

Added rituximab was effective in children and adolescents with high-risk B-cell NHL

The addition of rituximab to standard chemotherapy was a more effective therapy in children and adolescents with high-risk, high-grade,mature B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma than the use of chemotherapy alone, according to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The addition of rituximab resulted in long-term complete remission in the vast majority of patients, reported Veronique Minard-Colin, MD, of the Gustave Roussy Institute, Villejuif Cedex, France, and her colleagues on behalf of the European Intergroup for Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and the Children’s Oncology Group.

The researchers performed an open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial of 328 patients younger than 18 years of age with high-risk, mature B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (stage III with an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level or stage IV) or acute leukemia to compare the addition of six doses of rituximab to standard lymphomes malins B (LMB) chemotherapy with standard LMB chemotherapy alone. There were 164 patients assigned to each group. The primary end point of the study was event-free survival; overall survival and toxic effects were also followed.

The majority of patients had Burkitt’s lymphoma: 139 (84.8%) in the rituximab-chemotherapy group and 142 (86.6%) in the chemotherapy-alone group, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma being the second most common cancer: 19 (11.6%) vs. 12 (7.3%), respectively.

Event-free survival at 3 years was 93.9% (95% confidence interval, 89.1-96.7) in the rituximab-chemotherapy group and 82.3% (95% CI, 75.7-87.5) in the chemotherapy group.

Higher 3-year overall survival was also observed (95.1% in the rituximab-chemotherapy group vs. 87.3% in the chemotherapy group; hazard ratio for death, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.16 -0.82).

Eight patients in the rituximab-chemotherapy group died (4 deaths were disease related, 3 were treatment related, and 1 was from a second cancer), as did 20 in the chemotherapy group (17 deaths disease related, and 3 treatment related); HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.16-0.82.

The incidence of acute adverse events of grade 4 or higher after prephase treatment was 33.3% in the rituximab-chemotherapy group and 24.2% in the chemotherapy group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .07). However, around twice as many patients in the rituximab-chemotherapy group had a low IgG level at 1 year after trial inclusion, compared with the chemotherapy-alone group, which could indicate the potential for more frequent infections in the long term, the researchers stated.

“An assessment of the long-term effects of combining rituximab with this chemotherapy regimen in children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including data on immune status, will be useful,” they added.

The study was funded by the French Ministry of Health, Cancer Research UK, the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, the Children’s Cancer Foundation Hong Kong, the U.S. National Cancer Institute, and F. Hoffmann–La Roche–Genentech. Several of the authors reported consulting for and institutional and grant funding from F. Hoffmann-LaRoche, which markets rituximab, as well as relationships with other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Minard-Colin V et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2207-19.

The addition of rituximab to standard chemotherapy was a more effective therapy in children and adolescents with high-risk, high-grade,mature B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma than the use of chemotherapy alone, according to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The addition of rituximab resulted in long-term complete remission in the vast majority of patients, reported Veronique Minard-Colin, MD, of the Gustave Roussy Institute, Villejuif Cedex, France, and her colleagues on behalf of the European Intergroup for Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and the Children’s Oncology Group.

The researchers performed an open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial of 328 patients younger than 18 years of age with high-risk, mature B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (stage III with an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level or stage IV) or acute leukemia to compare the addition of six doses of rituximab to standard lymphomes malins B (LMB) chemotherapy with standard LMB chemotherapy alone. There were 164 patients assigned to each group. The primary end point of the study was event-free survival; overall survival and toxic effects were also followed.

The majority of patients had Burkitt’s lymphoma: 139 (84.8%) in the rituximab-chemotherapy group and 142 (86.6%) in the chemotherapy-alone group, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma being the second most common cancer: 19 (11.6%) vs. 12 (7.3%), respectively.

Event-free survival at 3 years was 93.9% (95% confidence interval, 89.1-96.7) in the rituximab-chemotherapy group and 82.3% (95% CI, 75.7-87.5) in the chemotherapy group.

Higher 3-year overall survival was also observed (95.1% in the rituximab-chemotherapy group vs. 87.3% in the chemotherapy group; hazard ratio for death, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.16 -0.82).

Eight patients in the rituximab-chemotherapy group died (4 deaths were disease related, 3 were treatment related, and 1 was from a second cancer), as did 20 in the chemotherapy group (17 deaths disease related, and 3 treatment related); HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.16-0.82.

The incidence of acute adverse events of grade 4 or higher after prephase treatment was 33.3% in the rituximab-chemotherapy group and 24.2% in the chemotherapy group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .07). However, around twice as many patients in the rituximab-chemotherapy group had a low IgG level at 1 year after trial inclusion, compared with the chemotherapy-alone group, which could indicate the potential for more frequent infections in the long term, the researchers stated.

“An assessment of the long-term effects of combining rituximab with this chemotherapy regimen in children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including data on immune status, will be useful,” they added.

The study was funded by the French Ministry of Health, Cancer Research UK, the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, the Children’s Cancer Foundation Hong Kong, the U.S. National Cancer Institute, and F. Hoffmann–La Roche–Genentech. Several of the authors reported consulting for and institutional and grant funding from F. Hoffmann-LaRoche, which markets rituximab, as well as relationships with other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Minard-Colin V et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2207-19.