User login

Erectile dysfunction meds’ link to melanoma not causal

The erectile dysfunction agents sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil showed a modest but significant association with increased risk of malignant melanoma in a large Swedish cohort study, but the pattern of the association suggests that the association is not causal, a report published online June 23 in JAMA shows.

These phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors target a part of the signaling pathway that has been implicated in the development of malignant melanoma, and the findings of a small cohort study (14 cases) suggested that the drugs might raise the risk of the malignancy. “It has been suggested that PDE5 inhibitors represent an important part of the medical history for dermatologists, and that melanoma screening could be performed by the physician when a sildenafil prescription is written for an older man with a history of sunburns,” said Dr. Stacy Loeb, of the department of urology and population health, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, and her associates.

To examine this possible association, the investigators performed a case-control study using information from nationwide Swedish drug and cancer registries. They focused on 4,065 previously cancer-free men who developed malignant melanoma during the 6-year study period and 20,325 control subjects who did not develop melanoma.

Eleven percent of the men with melanoma had filled prescriptions for PDE5 inhibitors, compared with only 8% of the control subjects, for a crude odds ratio of 1.31. Further multivariable analysis showed a persistently increased risk of melanoma among users of ED drugs (OR, 1.21). This translates to 7 additional cases of melanoma for every 100,000 ED drug users in Sweden, Dr. Loeb and her associates said (JAMA 2015 June 23 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6604]).

However, no dose-response relationship was found when the data were analyzed according to the number of prescriptions filled or the different exposure levels of the three PDE5 inhibitors. Men who filled the highest number of prescriptions did not have a higher risk of melanoma, and neither did men who took vardenafil or tadalafil, which have a longer half-life and thus a greater exposure time than sildenafil. This “raises questions about whether this association is causal. Rather, [it] may reflect confounding by lifestyle factors associated with both PDE5 inhibitor use and melanoma,” the researchers said.

Men who used ED agents were younger, and had fewer comorbidities, higher education levels, and higher incomes than those who did not. Malignant melanoma is known to be associated with higher SES and lower comorbidity burden. So it is possible that the association found in this study reflects residual confounding from “differences in lifestyle factors (such as leisure travel with ensuing sunburns) and health care seeking behavior,” they added.

This study was supported by several entities, including the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at the NYU Langone Medical Center. Dr. Loeb reported receiving personal fees from Bayer and Sanofi-Aventis, and her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Ferring, and AstraZeneca.

The erectile dysfunction agents sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil showed a modest but significant association with increased risk of malignant melanoma in a large Swedish cohort study, but the pattern of the association suggests that the association is not causal, a report published online June 23 in JAMA shows.

These phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors target a part of the signaling pathway that has been implicated in the development of malignant melanoma, and the findings of a small cohort study (14 cases) suggested that the drugs might raise the risk of the malignancy. “It has been suggested that PDE5 inhibitors represent an important part of the medical history for dermatologists, and that melanoma screening could be performed by the physician when a sildenafil prescription is written for an older man with a history of sunburns,” said Dr. Stacy Loeb, of the department of urology and population health, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, and her associates.

To examine this possible association, the investigators performed a case-control study using information from nationwide Swedish drug and cancer registries. They focused on 4,065 previously cancer-free men who developed malignant melanoma during the 6-year study period and 20,325 control subjects who did not develop melanoma.

Eleven percent of the men with melanoma had filled prescriptions for PDE5 inhibitors, compared with only 8% of the control subjects, for a crude odds ratio of 1.31. Further multivariable analysis showed a persistently increased risk of melanoma among users of ED drugs (OR, 1.21). This translates to 7 additional cases of melanoma for every 100,000 ED drug users in Sweden, Dr. Loeb and her associates said (JAMA 2015 June 23 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6604]).

However, no dose-response relationship was found when the data were analyzed according to the number of prescriptions filled or the different exposure levels of the three PDE5 inhibitors. Men who filled the highest number of prescriptions did not have a higher risk of melanoma, and neither did men who took vardenafil or tadalafil, which have a longer half-life and thus a greater exposure time than sildenafil. This “raises questions about whether this association is causal. Rather, [it] may reflect confounding by lifestyle factors associated with both PDE5 inhibitor use and melanoma,” the researchers said.

Men who used ED agents were younger, and had fewer comorbidities, higher education levels, and higher incomes than those who did not. Malignant melanoma is known to be associated with higher SES and lower comorbidity burden. So it is possible that the association found in this study reflects residual confounding from “differences in lifestyle factors (such as leisure travel with ensuing sunburns) and health care seeking behavior,” they added.

This study was supported by several entities, including the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at the NYU Langone Medical Center. Dr. Loeb reported receiving personal fees from Bayer and Sanofi-Aventis, and her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Ferring, and AstraZeneca.

The erectile dysfunction agents sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil showed a modest but significant association with increased risk of malignant melanoma in a large Swedish cohort study, but the pattern of the association suggests that the association is not causal, a report published online June 23 in JAMA shows.

These phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors target a part of the signaling pathway that has been implicated in the development of malignant melanoma, and the findings of a small cohort study (14 cases) suggested that the drugs might raise the risk of the malignancy. “It has been suggested that PDE5 inhibitors represent an important part of the medical history for dermatologists, and that melanoma screening could be performed by the physician when a sildenafil prescription is written for an older man with a history of sunburns,” said Dr. Stacy Loeb, of the department of urology and population health, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, and her associates.

To examine this possible association, the investigators performed a case-control study using information from nationwide Swedish drug and cancer registries. They focused on 4,065 previously cancer-free men who developed malignant melanoma during the 6-year study period and 20,325 control subjects who did not develop melanoma.

Eleven percent of the men with melanoma had filled prescriptions for PDE5 inhibitors, compared with only 8% of the control subjects, for a crude odds ratio of 1.31. Further multivariable analysis showed a persistently increased risk of melanoma among users of ED drugs (OR, 1.21). This translates to 7 additional cases of melanoma for every 100,000 ED drug users in Sweden, Dr. Loeb and her associates said (JAMA 2015 June 23 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6604]).

However, no dose-response relationship was found when the data were analyzed according to the number of prescriptions filled or the different exposure levels of the three PDE5 inhibitors. Men who filled the highest number of prescriptions did not have a higher risk of melanoma, and neither did men who took vardenafil or tadalafil, which have a longer half-life and thus a greater exposure time than sildenafil. This “raises questions about whether this association is causal. Rather, [it] may reflect confounding by lifestyle factors associated with both PDE5 inhibitor use and melanoma,” the researchers said.

Men who used ED agents were younger, and had fewer comorbidities, higher education levels, and higher incomes than those who did not. Malignant melanoma is known to be associated with higher SES and lower comorbidity burden. So it is possible that the association found in this study reflects residual confounding from “differences in lifestyle factors (such as leisure travel with ensuing sunburns) and health care seeking behavior,” they added.

This study was supported by several entities, including the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at the NYU Langone Medical Center. Dr. Loeb reported receiving personal fees from Bayer and Sanofi-Aventis, and her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Ferring, and AstraZeneca.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil are associated with a modestly but significantly increased risk of malignant melanoma.

Major finding: Eleven percent of the men with melanoma had filled prescriptions for phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors, compared with only 8% of the control subjects, for a crude odds ratio of 1.31.

Data source: A case-control study involving 4,065 older men in a Swedish cohort who developed malignant melanoma and 20,325 who did not.

Disclosures: This study was supported by several entities, including the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, and the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at the NYU Langone Medical Center, New York. Dr. Loeb reported receiving personal fees from Bayer and Sanofi-Aventis, and her associates reported ties to Pfizer, Ferring, and AstraZeneca.

Medications for Advanced Melanoma

After, test your knowledge by answering the 5 practice questions.

Practice Questions

1. Which of the following medications is considered an MEK inhibitor?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

2. Which of the following medications has been shown to be associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

3. What medication can be administered as a subcutaneous injection?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

4. Which of the following medications is a monoclonal antibody to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

5. Which of the following medications is an IL-2 cytokine?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

The answers appear on the next page.

Practice Question Answers

1. Which of the following medications is considered an MEK inhibitor?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

2. Which of the following medications has been shown to be associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

3. What medication can be administered as a subcutaneous injection?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

4. Which of the following medications is a monoclonal antibody to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

5. Which of the following medications is an IL-2 cytokine?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

After, test your knowledge by answering the 5 practice questions.

Practice Questions

1. Which of the following medications is considered an MEK inhibitor?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

2. Which of the following medications has been shown to be associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

3. What medication can be administered as a subcutaneous injection?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

4. Which of the following medications is a monoclonal antibody to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

5. Which of the following medications is an IL-2 cytokine?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

The answers appear on the next page.

Practice Question Answers

1. Which of the following medications is considered an MEK inhibitor?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

2. Which of the following medications has been shown to be associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

3. What medication can be administered as a subcutaneous injection?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

4. Which of the following medications is a monoclonal antibody to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

5. Which of the following medications is an IL-2 cytokine?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

After, test your knowledge by answering the 5 practice questions.

Practice Questions

1. Which of the following medications is considered an MEK inhibitor?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

2. Which of the following medications has been shown to be associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

3. What medication can be administered as a subcutaneous injection?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

4. Which of the following medications is a monoclonal antibody to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

5. Which of the following medications is an IL-2 cytokine?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

The answers appear on the next page.

Practice Question Answers

1. Which of the following medications is considered an MEK inhibitor?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

2. Which of the following medications has been shown to be associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

3. What medication can be administered as a subcutaneous injection?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

4. Which of the following medications is a monoclonal antibody to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

5. Which of the following medications is an IL-2 cytokine?

a. aldesleukin

b. dacarbazine

c. ipilimumab

d. recombinant interferon alfa-2b

e. trametinib

Fake Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer “Cures”

Skin cancer patients should beware of products available online that fraudulently claim to prevent and cure cancer, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, according to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These products often are marketed as natural treatments or dietary supplements. They have not gained FDA approval and therefore are not proven to be safe or effective. Rather, they can cause more harm to patients and delay the effects of conventional cancer treatments.

Firms that illegally market fraudulent cancer treatments often use exaggerated unsubstantiated claims to promote their products. The FDA has provided consumer health information with several phrases that consumers should recognize as warning signs for fraudulent cancer treatments:

- “Scientific breakthrough”

- “Miraculous cure”

- “Ancient remedy”

- “Treats all forms of cancer”

- “Skin cancers disappear”

- “Shrinks malignant tumors”

- “Nontoxic”

- “Doesn’t make you sick”

- “Avoid painful surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other conventional treatments”

- “Treat nonmelanoma skin cancers easily and safely”

- “Target cancer cells while leaving healthy cells alone”

Undocumented case histories or personal testimonials from patients or physicians claiming amazing results; suggestions that a product can treat serious or incurable diseases; and promises of no-risk, money-back guarantees also are signs of health fraud.

The FDA has cited black salves as one of the fake cancer remedies that have proven to be harmful. In a June 2015 Cutis article “Black Salve and Bloodroot Extract in Dermatologic Conditions,” Hou and Brewer reported an increased popularity of self-treatment with black salves in curing skin cancers and healing other skin conditions due to extensive advertising of its effectiveness. According to the FDA, black salves are sold with false promises that they will cure melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers by “drawing out” the disease from beneath the skin. However, Hou and Brewer warned that some black salves contain escharotics such as zinc chloride and bloodroot, which could cause damage to healthy tissue.

“Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies,” the authors reported. “[It] is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions.”

Dermatologists should be aware that skin cancer patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves. Health care professionals should educate patients about fraudulent cancer treatments versus investigational treatments.

For a complete list of fake cancer cures consumers should avoid, consult the FDA.

Skin cancer patients should beware of products available online that fraudulently claim to prevent and cure cancer, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, according to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These products often are marketed as natural treatments or dietary supplements. They have not gained FDA approval and therefore are not proven to be safe or effective. Rather, they can cause more harm to patients and delay the effects of conventional cancer treatments.

Firms that illegally market fraudulent cancer treatments often use exaggerated unsubstantiated claims to promote their products. The FDA has provided consumer health information with several phrases that consumers should recognize as warning signs for fraudulent cancer treatments:

- “Scientific breakthrough”

- “Miraculous cure”

- “Ancient remedy”

- “Treats all forms of cancer”

- “Skin cancers disappear”

- “Shrinks malignant tumors”

- “Nontoxic”

- “Doesn’t make you sick”

- “Avoid painful surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other conventional treatments”

- “Treat nonmelanoma skin cancers easily and safely”

- “Target cancer cells while leaving healthy cells alone”

Undocumented case histories or personal testimonials from patients or physicians claiming amazing results; suggestions that a product can treat serious or incurable diseases; and promises of no-risk, money-back guarantees also are signs of health fraud.

The FDA has cited black salves as one of the fake cancer remedies that have proven to be harmful. In a June 2015 Cutis article “Black Salve and Bloodroot Extract in Dermatologic Conditions,” Hou and Brewer reported an increased popularity of self-treatment with black salves in curing skin cancers and healing other skin conditions due to extensive advertising of its effectiveness. According to the FDA, black salves are sold with false promises that they will cure melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers by “drawing out” the disease from beneath the skin. However, Hou and Brewer warned that some black salves contain escharotics such as zinc chloride and bloodroot, which could cause damage to healthy tissue.

“Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies,” the authors reported. “[It] is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions.”

Dermatologists should be aware that skin cancer patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves. Health care professionals should educate patients about fraudulent cancer treatments versus investigational treatments.

For a complete list of fake cancer cures consumers should avoid, consult the FDA.

Skin cancer patients should beware of products available online that fraudulently claim to prevent and cure cancer, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, according to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These products often are marketed as natural treatments or dietary supplements. They have not gained FDA approval and therefore are not proven to be safe or effective. Rather, they can cause more harm to patients and delay the effects of conventional cancer treatments.

Firms that illegally market fraudulent cancer treatments often use exaggerated unsubstantiated claims to promote their products. The FDA has provided consumer health information with several phrases that consumers should recognize as warning signs for fraudulent cancer treatments:

- “Scientific breakthrough”

- “Miraculous cure”

- “Ancient remedy”

- “Treats all forms of cancer”

- “Skin cancers disappear”

- “Shrinks malignant tumors”

- “Nontoxic”

- “Doesn’t make you sick”

- “Avoid painful surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other conventional treatments”

- “Treat nonmelanoma skin cancers easily and safely”

- “Target cancer cells while leaving healthy cells alone”

Undocumented case histories or personal testimonials from patients or physicians claiming amazing results; suggestions that a product can treat serious or incurable diseases; and promises of no-risk, money-back guarantees also are signs of health fraud.

The FDA has cited black salves as one of the fake cancer remedies that have proven to be harmful. In a June 2015 Cutis article “Black Salve and Bloodroot Extract in Dermatologic Conditions,” Hou and Brewer reported an increased popularity of self-treatment with black salves in curing skin cancers and healing other skin conditions due to extensive advertising of its effectiveness. According to the FDA, black salves are sold with false promises that they will cure melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers by “drawing out” the disease from beneath the skin. However, Hou and Brewer warned that some black salves contain escharotics such as zinc chloride and bloodroot, which could cause damage to healthy tissue.

“Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies,” the authors reported. “[It] is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions.”

Dermatologists should be aware that skin cancer patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves. Health care professionals should educate patients about fraudulent cancer treatments versus investigational treatments.

For a complete list of fake cancer cures consumers should avoid, consult the FDA.

Prevalence and Impact of Health-Related Internet and Smartphone Use Among Dermatology Patients

Patients increasingly use the Internet and/or smartphone applications (apps) to seek health information and track personal health data,1,2 typically in the spirit of being a more educated consumer. However, many patients use the Internet in an attempt to self-diagnose and independently find treatment options, thus avoiding (in their opinion) the need to seek in-person medical care. Additionally, electronic access to health information has expanded beyond computers to smartphones with apps that can provide users with a simple interface to personalize the health information they seek and receive.

Prior studies have shown that seeking online health information and health-related social media is more common among women, younger patients, those with a college education, and those with a higher income.3,4 However, the prevalence of health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients as well as how patients ultimately use this information is not well studied. This information about patient behavior is important because of the potential harm that may come from patient self-diagnosis, which may delay or prevent treatment, as well as the benefits of patient self-education, which may expedite diagnosis and treatment.5 We surveyed a heterogeneous patient population at 2 dermatology offices in a major academic medical center to assess the prevalence and predictors of Internet and smartphone use to obtain both general medical and dermatologic information among dermatology patients. We also evaluated the impact that health information obtained from online sources has on a patient’s degree of concern about cutaneous disease and the likelihood of seeing a dermatologist for a skin problem.

Methods

Survey and Participants

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. All patients aged 18 years or older who presented to the department of dermatology at 2 offices of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from September 2013 through July 2014 were invited to participate in an anonymous 33-question survey regarding their use of the Internet and smartphone apps to obtain health information and make health care decisions. Patients were asked to complete the survey prior to seeing a health care provider and return it to a locked box by the front desk before leaving the office. Survey questions were designed by physicians with content expertise (J.A.W. and L.K.F.) and were reviewed by a statistician with survey expertise (D.G.W.). The survey included questions about patient demographics, Internet and smartphone use (both general and health related), and specific sources accessed. The survey also inquired about the impact of health information obtained via the Internet and smartphone apps on respondents’ degree of worry about a hypothetical skin condition or lesion using a 5-point Likert scale (1=no worry; 5=very worried). Respondents also were asked which skin conditions they previously researched online and whether their findings impacted their decision to see a dermatologist. Additionally, respondents were asked to list the smartphone apps and other online health resources they had used within the last 3 months. Prior to distribution, the survey was piloted with 10 participants and no issues with comprehensibility were noted.

Statistical Analysis

We described demographic traits (eg, age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of education, income) and factors associated with access to health care (eg, specialist co-pay, travel time from dermatology office) of respondents using proportions. We evaluated respondents’ access to and use of Internet- and smartphone-based health information using proportions and used χ² tests to quantify differences by sex and age (<50 years and ≥50 years).

We analyzed the impact of Internet and smartphone-based health information on patient worry about skin conditions by obtaining median worry on a 5-point Likert scale. Due to the nonparametric nature of the data, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to quantify differences by sex and age (<50 and ≥50 years). We used multiple logistic regression to identify factors associated with 3 outcomes: (1) using the Internet to self-diagnose a dermatologic disease, (2) using the Internet to obtain dermatology-related information within the last 3 months, (3) and previously refraining from visiting a dermatologist based on reassurance from online resources. Predictors included the aforementioned demographic and health-care access–related traits. We also categorized smartphone apps used by respondents (ie, fitness/nutrition, reference, self-help, health monitoring, diagnostic aids, electronic medical record) and calculated the proportion of respondents with 1 or more of each type of app on their smartphones. Analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 and IBM SPSS 22.0.

Results

Of 1000 patients who were invited to participate in the study, a total of 775 respondents completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 77.5%. The majority of respondents were aged 30 to 60 years (mean age [standard deviation], 44.5 [17.2] years; median age [interquartile range], 44 [29–59] years), female (66.7%), and non-Hispanic white (83.3%)(Table 1). The majority of respondents (88.8%) had completed at least some college. Nearly all respondents had medical insurance (97.8%), but annual household income and insurance co-pay varied considerably. Only 10.8% of respondents traveled more than an hour to our offices.

The majority of respondents had access to home Internet and owned a smartphone (Table 2). Use of the Internet to obtain health-related information in the 3 months prior to presentation was more common among females (77.9% vs 70.1%; P=.03) and respondents younger than 50 years (83.4% vs 62.5%; P<.001); the same was true for dermatology-related infor-mation (females: 43.2% vs 31.0%; P=.003; aged <50 years, 51.6% vs 22.2%; P<.001). The majority of respondents indicated that they use the Internet to obtain health-related information both before and after they see their doctor. Most respondents indicated that they sometimes discuss health-related information found on the Internet with a physician. Smartphone use to obtain health-related information was more common among respondents younger than 50 years versus those who were 50 years or older (55.5% vs 24.1%; P<.001), as was smartphone use to diagnose skin problems (20.0% vs 6.3%; P<.001).

In multivariable analysis, use of the Internet or a smartphone to obtain health-related information was associated with younger age (<50 years) and a higher level of education (both P<.001). Use of the Internet to obtain dermatology-related information (P<.001) and use of a smartphone to help diagnose a skin problem (P=.001) was associated with younger age (<50 years) only. Income, sex, co-pay to see a dermatologist, and travel time to the dermatology office were not associated with use of online resources for general or dermatology-specific health-related information or assistance with diagnosing a skin problem.

Of 204 respondents who indicated that they previously attempted to self-diagnose a skin condition using the Internet, the most commonly researched condition was skin cancer/moles/unknown spots (64.7%), followed by rashes (40.7%), acne (20.6%), cosmetic issues (16.2%), psoriasis (12.7%), dermatitis (3.4%), warts (1.5%), tick bites (1.0%), and lupus (1.0%)(some respondents selected more than one condition). Only 7.0% of respondents indicated that they previously had refrained from visiting a dermatologist based on reassurance from online resources. Compared to the rest of the surveyed population, these respondents were younger (P=.001), but there were no significant differences in sex, highest level of education, household income, or travel time to the dermatology office. The most commonly researched condition among these respondents was acne (12 respondents), and 11 respondents indicated that they had attempted to self-diagnose a mole or potential cancer using online sources.

Of 557 respondents who owned a smartphone, 31.8% reported using at least 1 health-related app (mean number of health apps per respondent, 1.5). Of the apps that respondents used, 45.9% focused on fitness/nutrition, 28.7% provided reference information, 13.4% were a patient portal for receiving information from their electronic medical record, 8.6% provided a health monitoring function, 1.9% served as a diagnostic aid, and 1.5% provided coping assistance and emotional support for individuals with cognitive or emotional conditions; only 1 respondent reported using an app related to dermatology.

All respondents were asked to rate their anticipated degree of worry if the Internet or a smartphone app suggested that a skin lesion was benign versus dangerous on a 5-point scale. Overall, the median worry rating increased from 3 to 5 when information accessed via the Internet or a smartphone app suggested a lesion was dangerous rather than benign. A change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 36.1% of females and 49.1% of males (P=.002) when information obtained via the Internet indicated a lesion was dangerous and in 47.5% of females and 58.8% of males (P=.006) when a smartphone app indicated that a lesion was dangerous. When information obtained via the Internet indicated a lesion was dangerous, a change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 41.8% of respondents who were younger than 50 years and in 41.1% of those who were 50 years or older (P=.93). When a smartphone app indicated a lesion was dangerous, a change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 50.2% of respondents who were younger than 50 years and in 52.2% of those who were 50 years or older (P=.61).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found that health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients is common and may impact both patients’ degree of concern about a skin lesion as well as the likelihood of seeking in-person medical care if they are reassured by the results of their online findings. Age and level of education were associated with Internet and smartphone use to obtain dermatology-related health information but not factors related to health care access. More patients used the Internet or a smartphone to obtain general medical information versus dermatology-related information. Respondents who indicated that they used the Internet to obtain health-related information tended to do so before visiting their physician.

Our finding that a patient’s level of worry about a hypothetical skin condition or lesion is influenced by health information obtained via the Internet or a smartphone app is concerning. One study found that participants who used a popular search engine to look for information about vaccine safety and dangers were directed to Web sites with inaccurate information more than 50% of the time, and 65% of the information they obtained from these sites was false.6 In our study, approximately 25% of respondents had previously consulted online resources to attempt toself-diagnose a skin condition. Online sources about dermatologic conditions were consulted most frequently for information about potential skin cancers, moles, and unknown spots. A prior study showed that smartphone apps that claim to aid patients in determining whether a skin lesion is low or high risk for melanoma often are inaccurate and are associated with a high rate of missed melanomas.5 Even though we surveyed patients who did end up seeing a dermatologist, some respondents had previously opted out of seeing a dermatologist based on information they had found online. Because our study was conducted among patients who chose to seek care at a dermatology office, the problem is likely greater than estimated from our findings because we had no way of reaching individuals who decided to completely forgo a visit with a dermatologist.

Although use of the Internet to obtain health-related information was common among older adults in our population, it was nearly universal in younger adults. Health-related smartphone use was more than twice as common in younger versus older adults, which could be due to an increased comfort with technology and its integration into daily life. The fact that age and education were associated with Internet use for dermatology-related health information but not household income or travel time to the dermatology office suggests that information seeking is not due to lack of resources limiting access to dermatologic care but rather to the greater role that rapid access to online information plays in patients’ lives. Our findings are similar to another study that examined the use of online sources for general health information.7

This study has several limitations. First, there may have been some selection bias. We specifically aimed to understand the health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients, thus restricting our sample to this population. By doing so, we were unable to assess the use of such resources by the general population, particularly those individuals who chose not to see a dermatologist at all based on their own online research. Our findings may not apply to other practices and regions of the country, as we implemented our study in one geographic location and in offices of an academic practice. Although our sample size and diversity with regard to income, education, and age suggest that our results are likely generalizable to many settings, it is important to note that nearly all respondents in this study had health insurance and our findings are thus not necessarily applicable to those individuals who are uninsured.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the availability of online health information regarding dermatologic conditions provides dermatologists with both opportunities and challenges. Many patients consult online resources for health information, and the popularity of this practice is likely to increase with time, particularly as newer smartphones with features designed to allow users to monitor their health are developed with health-conscious consumers in mind. Most large health care systems provide patients with resources to view laboratory results and communicate with physicians online. It is important for dermatologists to be involved in the development of high-quality online content that educates the public while also emphasizing the need to seek in-person medical care, particularly in potential cases of skin cancer. It also is important for patients to be involved in the content development process to ensure that the messages they take away from online resources are the ones physicians wish to convey. Ideally, online forms of education will increase patients’ sense of self-efficacy while encouraging appropriate consultation for potentially harmful skin conditions.

1. Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the Internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e4.

2. Ybarra M, Suman M. Reasons, assessments and actions taken: sex and age differences in uses of Internet health information. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:512-521.

3. Bhandari N, Shi Y, Jung K. Seeking health information online: does limited healthcare access matter? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:1113-1117.

4. Thackeray R, Crookston BT, West JH. Correlates of health-related social media use among adults. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e21.

5. Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Akilov O, et al. Diagnostic inaccuracy of smartphone applications for melanoma detection. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:422-426.

6. Kortum P, Edwards C, Richards-Kortum R. The impact of inaccurate Internet health information in a secondary school learning environment. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e17.

7. Mead N, Varnam R, Rogers A, et al. What predicts patients’ interest in the internet as a health resource in primary care in England? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8:33-39.

Patients increasingly use the Internet and/or smartphone applications (apps) to seek health information and track personal health data,1,2 typically in the spirit of being a more educated consumer. However, many patients use the Internet in an attempt to self-diagnose and independently find treatment options, thus avoiding (in their opinion) the need to seek in-person medical care. Additionally, electronic access to health information has expanded beyond computers to smartphones with apps that can provide users with a simple interface to personalize the health information they seek and receive.

Prior studies have shown that seeking online health information and health-related social media is more common among women, younger patients, those with a college education, and those with a higher income.3,4 However, the prevalence of health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients as well as how patients ultimately use this information is not well studied. This information about patient behavior is important because of the potential harm that may come from patient self-diagnosis, which may delay or prevent treatment, as well as the benefits of patient self-education, which may expedite diagnosis and treatment.5 We surveyed a heterogeneous patient population at 2 dermatology offices in a major academic medical center to assess the prevalence and predictors of Internet and smartphone use to obtain both general medical and dermatologic information among dermatology patients. We also evaluated the impact that health information obtained from online sources has on a patient’s degree of concern about cutaneous disease and the likelihood of seeing a dermatologist for a skin problem.

Methods

Survey and Participants

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. All patients aged 18 years or older who presented to the department of dermatology at 2 offices of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from September 2013 through July 2014 were invited to participate in an anonymous 33-question survey regarding their use of the Internet and smartphone apps to obtain health information and make health care decisions. Patients were asked to complete the survey prior to seeing a health care provider and return it to a locked box by the front desk before leaving the office. Survey questions were designed by physicians with content expertise (J.A.W. and L.K.F.) and were reviewed by a statistician with survey expertise (D.G.W.). The survey included questions about patient demographics, Internet and smartphone use (both general and health related), and specific sources accessed. The survey also inquired about the impact of health information obtained via the Internet and smartphone apps on respondents’ degree of worry about a hypothetical skin condition or lesion using a 5-point Likert scale (1=no worry; 5=very worried). Respondents also were asked which skin conditions they previously researched online and whether their findings impacted their decision to see a dermatologist. Additionally, respondents were asked to list the smartphone apps and other online health resources they had used within the last 3 months. Prior to distribution, the survey was piloted with 10 participants and no issues with comprehensibility were noted.

Statistical Analysis

We described demographic traits (eg, age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of education, income) and factors associated with access to health care (eg, specialist co-pay, travel time from dermatology office) of respondents using proportions. We evaluated respondents’ access to and use of Internet- and smartphone-based health information using proportions and used χ² tests to quantify differences by sex and age (<50 years and ≥50 years).

We analyzed the impact of Internet and smartphone-based health information on patient worry about skin conditions by obtaining median worry on a 5-point Likert scale. Due to the nonparametric nature of the data, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to quantify differences by sex and age (<50 and ≥50 years). We used multiple logistic regression to identify factors associated with 3 outcomes: (1) using the Internet to self-diagnose a dermatologic disease, (2) using the Internet to obtain dermatology-related information within the last 3 months, (3) and previously refraining from visiting a dermatologist based on reassurance from online resources. Predictors included the aforementioned demographic and health-care access–related traits. We also categorized smartphone apps used by respondents (ie, fitness/nutrition, reference, self-help, health monitoring, diagnostic aids, electronic medical record) and calculated the proportion of respondents with 1 or more of each type of app on their smartphones. Analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 and IBM SPSS 22.0.

Results

Of 1000 patients who were invited to participate in the study, a total of 775 respondents completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 77.5%. The majority of respondents were aged 30 to 60 years (mean age [standard deviation], 44.5 [17.2] years; median age [interquartile range], 44 [29–59] years), female (66.7%), and non-Hispanic white (83.3%)(Table 1). The majority of respondents (88.8%) had completed at least some college. Nearly all respondents had medical insurance (97.8%), but annual household income and insurance co-pay varied considerably. Only 10.8% of respondents traveled more than an hour to our offices.

The majority of respondents had access to home Internet and owned a smartphone (Table 2). Use of the Internet to obtain health-related information in the 3 months prior to presentation was more common among females (77.9% vs 70.1%; P=.03) and respondents younger than 50 years (83.4% vs 62.5%; P<.001); the same was true for dermatology-related infor-mation (females: 43.2% vs 31.0%; P=.003; aged <50 years, 51.6% vs 22.2%; P<.001). The majority of respondents indicated that they use the Internet to obtain health-related information both before and after they see their doctor. Most respondents indicated that they sometimes discuss health-related information found on the Internet with a physician. Smartphone use to obtain health-related information was more common among respondents younger than 50 years versus those who were 50 years or older (55.5% vs 24.1%; P<.001), as was smartphone use to diagnose skin problems (20.0% vs 6.3%; P<.001).

In multivariable analysis, use of the Internet or a smartphone to obtain health-related information was associated with younger age (<50 years) and a higher level of education (both P<.001). Use of the Internet to obtain dermatology-related information (P<.001) and use of a smartphone to help diagnose a skin problem (P=.001) was associated with younger age (<50 years) only. Income, sex, co-pay to see a dermatologist, and travel time to the dermatology office were not associated with use of online resources for general or dermatology-specific health-related information or assistance with diagnosing a skin problem.

Of 204 respondents who indicated that they previously attempted to self-diagnose a skin condition using the Internet, the most commonly researched condition was skin cancer/moles/unknown spots (64.7%), followed by rashes (40.7%), acne (20.6%), cosmetic issues (16.2%), psoriasis (12.7%), dermatitis (3.4%), warts (1.5%), tick bites (1.0%), and lupus (1.0%)(some respondents selected more than one condition). Only 7.0% of respondents indicated that they previously had refrained from visiting a dermatologist based on reassurance from online resources. Compared to the rest of the surveyed population, these respondents were younger (P=.001), but there were no significant differences in sex, highest level of education, household income, or travel time to the dermatology office. The most commonly researched condition among these respondents was acne (12 respondents), and 11 respondents indicated that they had attempted to self-diagnose a mole or potential cancer using online sources.

Of 557 respondents who owned a smartphone, 31.8% reported using at least 1 health-related app (mean number of health apps per respondent, 1.5). Of the apps that respondents used, 45.9% focused on fitness/nutrition, 28.7% provided reference information, 13.4% were a patient portal for receiving information from their electronic medical record, 8.6% provided a health monitoring function, 1.9% served as a diagnostic aid, and 1.5% provided coping assistance and emotional support for individuals with cognitive or emotional conditions; only 1 respondent reported using an app related to dermatology.

All respondents were asked to rate their anticipated degree of worry if the Internet or a smartphone app suggested that a skin lesion was benign versus dangerous on a 5-point scale. Overall, the median worry rating increased from 3 to 5 when information accessed via the Internet or a smartphone app suggested a lesion was dangerous rather than benign. A change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 36.1% of females and 49.1% of males (P=.002) when information obtained via the Internet indicated a lesion was dangerous and in 47.5% of females and 58.8% of males (P=.006) when a smartphone app indicated that a lesion was dangerous. When information obtained via the Internet indicated a lesion was dangerous, a change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 41.8% of respondents who were younger than 50 years and in 41.1% of those who were 50 years or older (P=.93). When a smartphone app indicated a lesion was dangerous, a change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 50.2% of respondents who were younger than 50 years and in 52.2% of those who were 50 years or older (P=.61).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found that health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients is common and may impact both patients’ degree of concern about a skin lesion as well as the likelihood of seeking in-person medical care if they are reassured by the results of their online findings. Age and level of education were associated with Internet and smartphone use to obtain dermatology-related health information but not factors related to health care access. More patients used the Internet or a smartphone to obtain general medical information versus dermatology-related information. Respondents who indicated that they used the Internet to obtain health-related information tended to do so before visiting their physician.

Our finding that a patient’s level of worry about a hypothetical skin condition or lesion is influenced by health information obtained via the Internet or a smartphone app is concerning. One study found that participants who used a popular search engine to look for information about vaccine safety and dangers were directed to Web sites with inaccurate information more than 50% of the time, and 65% of the information they obtained from these sites was false.6 In our study, approximately 25% of respondents had previously consulted online resources to attempt toself-diagnose a skin condition. Online sources about dermatologic conditions were consulted most frequently for information about potential skin cancers, moles, and unknown spots. A prior study showed that smartphone apps that claim to aid patients in determining whether a skin lesion is low or high risk for melanoma often are inaccurate and are associated with a high rate of missed melanomas.5 Even though we surveyed patients who did end up seeing a dermatologist, some respondents had previously opted out of seeing a dermatologist based on information they had found online. Because our study was conducted among patients who chose to seek care at a dermatology office, the problem is likely greater than estimated from our findings because we had no way of reaching individuals who decided to completely forgo a visit with a dermatologist.

Although use of the Internet to obtain health-related information was common among older adults in our population, it was nearly universal in younger adults. Health-related smartphone use was more than twice as common in younger versus older adults, which could be due to an increased comfort with technology and its integration into daily life. The fact that age and education were associated with Internet use for dermatology-related health information but not household income or travel time to the dermatology office suggests that information seeking is not due to lack of resources limiting access to dermatologic care but rather to the greater role that rapid access to online information plays in patients’ lives. Our findings are similar to another study that examined the use of online sources for general health information.7

This study has several limitations. First, there may have been some selection bias. We specifically aimed to understand the health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients, thus restricting our sample to this population. By doing so, we were unable to assess the use of such resources by the general population, particularly those individuals who chose not to see a dermatologist at all based on their own online research. Our findings may not apply to other practices and regions of the country, as we implemented our study in one geographic location and in offices of an academic practice. Although our sample size and diversity with regard to income, education, and age suggest that our results are likely generalizable to many settings, it is important to note that nearly all respondents in this study had health insurance and our findings are thus not necessarily applicable to those individuals who are uninsured.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the availability of online health information regarding dermatologic conditions provides dermatologists with both opportunities and challenges. Many patients consult online resources for health information, and the popularity of this practice is likely to increase with time, particularly as newer smartphones with features designed to allow users to monitor their health are developed with health-conscious consumers in mind. Most large health care systems provide patients with resources to view laboratory results and communicate with physicians online. It is important for dermatologists to be involved in the development of high-quality online content that educates the public while also emphasizing the need to seek in-person medical care, particularly in potential cases of skin cancer. It also is important for patients to be involved in the content development process to ensure that the messages they take away from online resources are the ones physicians wish to convey. Ideally, online forms of education will increase patients’ sense of self-efficacy while encouraging appropriate consultation for potentially harmful skin conditions.

Patients increasingly use the Internet and/or smartphone applications (apps) to seek health information and track personal health data,1,2 typically in the spirit of being a more educated consumer. However, many patients use the Internet in an attempt to self-diagnose and independently find treatment options, thus avoiding (in their opinion) the need to seek in-person medical care. Additionally, electronic access to health information has expanded beyond computers to smartphones with apps that can provide users with a simple interface to personalize the health information they seek and receive.

Prior studies have shown that seeking online health information and health-related social media is more common among women, younger patients, those with a college education, and those with a higher income.3,4 However, the prevalence of health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients as well as how patients ultimately use this information is not well studied. This information about patient behavior is important because of the potential harm that may come from patient self-diagnosis, which may delay or prevent treatment, as well as the benefits of patient self-education, which may expedite diagnosis and treatment.5 We surveyed a heterogeneous patient population at 2 dermatology offices in a major academic medical center to assess the prevalence and predictors of Internet and smartphone use to obtain both general medical and dermatologic information among dermatology patients. We also evaluated the impact that health information obtained from online sources has on a patient’s degree of concern about cutaneous disease and the likelihood of seeing a dermatologist for a skin problem.

Methods

Survey and Participants

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. All patients aged 18 years or older who presented to the department of dermatology at 2 offices of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from September 2013 through July 2014 were invited to participate in an anonymous 33-question survey regarding their use of the Internet and smartphone apps to obtain health information and make health care decisions. Patients were asked to complete the survey prior to seeing a health care provider and return it to a locked box by the front desk before leaving the office. Survey questions were designed by physicians with content expertise (J.A.W. and L.K.F.) and were reviewed by a statistician with survey expertise (D.G.W.). The survey included questions about patient demographics, Internet and smartphone use (both general and health related), and specific sources accessed. The survey also inquired about the impact of health information obtained via the Internet and smartphone apps on respondents’ degree of worry about a hypothetical skin condition or lesion using a 5-point Likert scale (1=no worry; 5=very worried). Respondents also were asked which skin conditions they previously researched online and whether their findings impacted their decision to see a dermatologist. Additionally, respondents were asked to list the smartphone apps and other online health resources they had used within the last 3 months. Prior to distribution, the survey was piloted with 10 participants and no issues with comprehensibility were noted.

Statistical Analysis

We described demographic traits (eg, age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of education, income) and factors associated with access to health care (eg, specialist co-pay, travel time from dermatology office) of respondents using proportions. We evaluated respondents’ access to and use of Internet- and smartphone-based health information using proportions and used χ² tests to quantify differences by sex and age (<50 years and ≥50 years).

We analyzed the impact of Internet and smartphone-based health information on patient worry about skin conditions by obtaining median worry on a 5-point Likert scale. Due to the nonparametric nature of the data, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to quantify differences by sex and age (<50 and ≥50 years). We used multiple logistic regression to identify factors associated with 3 outcomes: (1) using the Internet to self-diagnose a dermatologic disease, (2) using the Internet to obtain dermatology-related information within the last 3 months, (3) and previously refraining from visiting a dermatologist based on reassurance from online resources. Predictors included the aforementioned demographic and health-care access–related traits. We also categorized smartphone apps used by respondents (ie, fitness/nutrition, reference, self-help, health monitoring, diagnostic aids, electronic medical record) and calculated the proportion of respondents with 1 or more of each type of app on their smartphones. Analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 and IBM SPSS 22.0.

Results

Of 1000 patients who were invited to participate in the study, a total of 775 respondents completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 77.5%. The majority of respondents were aged 30 to 60 years (mean age [standard deviation], 44.5 [17.2] years; median age [interquartile range], 44 [29–59] years), female (66.7%), and non-Hispanic white (83.3%)(Table 1). The majority of respondents (88.8%) had completed at least some college. Nearly all respondents had medical insurance (97.8%), but annual household income and insurance co-pay varied considerably. Only 10.8% of respondents traveled more than an hour to our offices.

The majority of respondents had access to home Internet and owned a smartphone (Table 2). Use of the Internet to obtain health-related information in the 3 months prior to presentation was more common among females (77.9% vs 70.1%; P=.03) and respondents younger than 50 years (83.4% vs 62.5%; P<.001); the same was true for dermatology-related infor-mation (females: 43.2% vs 31.0%; P=.003; aged <50 years, 51.6% vs 22.2%; P<.001). The majority of respondents indicated that they use the Internet to obtain health-related information both before and after they see their doctor. Most respondents indicated that they sometimes discuss health-related information found on the Internet with a physician. Smartphone use to obtain health-related information was more common among respondents younger than 50 years versus those who were 50 years or older (55.5% vs 24.1%; P<.001), as was smartphone use to diagnose skin problems (20.0% vs 6.3%; P<.001).

In multivariable analysis, use of the Internet or a smartphone to obtain health-related information was associated with younger age (<50 years) and a higher level of education (both P<.001). Use of the Internet to obtain dermatology-related information (P<.001) and use of a smartphone to help diagnose a skin problem (P=.001) was associated with younger age (<50 years) only. Income, sex, co-pay to see a dermatologist, and travel time to the dermatology office were not associated with use of online resources for general or dermatology-specific health-related information or assistance with diagnosing a skin problem.

Of 204 respondents who indicated that they previously attempted to self-diagnose a skin condition using the Internet, the most commonly researched condition was skin cancer/moles/unknown spots (64.7%), followed by rashes (40.7%), acne (20.6%), cosmetic issues (16.2%), psoriasis (12.7%), dermatitis (3.4%), warts (1.5%), tick bites (1.0%), and lupus (1.0%)(some respondents selected more than one condition). Only 7.0% of respondents indicated that they previously had refrained from visiting a dermatologist based on reassurance from online resources. Compared to the rest of the surveyed population, these respondents were younger (P=.001), but there were no significant differences in sex, highest level of education, household income, or travel time to the dermatology office. The most commonly researched condition among these respondents was acne (12 respondents), and 11 respondents indicated that they had attempted to self-diagnose a mole or potential cancer using online sources.

Of 557 respondents who owned a smartphone, 31.8% reported using at least 1 health-related app (mean number of health apps per respondent, 1.5). Of the apps that respondents used, 45.9% focused on fitness/nutrition, 28.7% provided reference information, 13.4% were a patient portal for receiving information from their electronic medical record, 8.6% provided a health monitoring function, 1.9% served as a diagnostic aid, and 1.5% provided coping assistance and emotional support for individuals with cognitive or emotional conditions; only 1 respondent reported using an app related to dermatology.

All respondents were asked to rate their anticipated degree of worry if the Internet or a smartphone app suggested that a skin lesion was benign versus dangerous on a 5-point scale. Overall, the median worry rating increased from 3 to 5 when information accessed via the Internet or a smartphone app suggested a lesion was dangerous rather than benign. A change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 36.1% of females and 49.1% of males (P=.002) when information obtained via the Internet indicated a lesion was dangerous and in 47.5% of females and 58.8% of males (P=.006) when a smartphone app indicated that a lesion was dangerous. When information obtained via the Internet indicated a lesion was dangerous, a change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 41.8% of respondents who were younger than 50 years and in 41.1% of those who were 50 years or older (P=.93). When a smartphone app indicated a lesion was dangerous, a change in worry of 2 or more points was seen in 50.2% of respondents who were younger than 50 years and in 52.2% of those who were 50 years or older (P=.61).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found that health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients is common and may impact both patients’ degree of concern about a skin lesion as well as the likelihood of seeking in-person medical care if they are reassured by the results of their online findings. Age and level of education were associated with Internet and smartphone use to obtain dermatology-related health information but not factors related to health care access. More patients used the Internet or a smartphone to obtain general medical information versus dermatology-related information. Respondents who indicated that they used the Internet to obtain health-related information tended to do so before visiting their physician.

Our finding that a patient’s level of worry about a hypothetical skin condition or lesion is influenced by health information obtained via the Internet or a smartphone app is concerning. One study found that participants who used a popular search engine to look for information about vaccine safety and dangers were directed to Web sites with inaccurate information more than 50% of the time, and 65% of the information they obtained from these sites was false.6 In our study, approximately 25% of respondents had previously consulted online resources to attempt toself-diagnose a skin condition. Online sources about dermatologic conditions were consulted most frequently for information about potential skin cancers, moles, and unknown spots. A prior study showed that smartphone apps that claim to aid patients in determining whether a skin lesion is low or high risk for melanoma often are inaccurate and are associated with a high rate of missed melanomas.5 Even though we surveyed patients who did end up seeing a dermatologist, some respondents had previously opted out of seeing a dermatologist based on information they had found online. Because our study was conducted among patients who chose to seek care at a dermatology office, the problem is likely greater than estimated from our findings because we had no way of reaching individuals who decided to completely forgo a visit with a dermatologist.

Although use of the Internet to obtain health-related information was common among older adults in our population, it was nearly universal in younger adults. Health-related smartphone use was more than twice as common in younger versus older adults, which could be due to an increased comfort with technology and its integration into daily life. The fact that age and education were associated with Internet use for dermatology-related health information but not household income or travel time to the dermatology office suggests that information seeking is not due to lack of resources limiting access to dermatologic care but rather to the greater role that rapid access to online information plays in patients’ lives. Our findings are similar to another study that examined the use of online sources for general health information.7

This study has several limitations. First, there may have been some selection bias. We specifically aimed to understand the health-related Internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients, thus restricting our sample to this population. By doing so, we were unable to assess the use of such resources by the general population, particularly those individuals who chose not to see a dermatologist at all based on their own online research. Our findings may not apply to other practices and regions of the country, as we implemented our study in one geographic location and in offices of an academic practice. Although our sample size and diversity with regard to income, education, and age suggest that our results are likely generalizable to many settings, it is important to note that nearly all respondents in this study had health insurance and our findings are thus not necessarily applicable to those individuals who are uninsured.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the availability of online health information regarding dermatologic conditions provides dermatologists with both opportunities and challenges. Many patients consult online resources for health information, and the popularity of this practice is likely to increase with time, particularly as newer smartphones with features designed to allow users to monitor their health are developed with health-conscious consumers in mind. Most large health care systems provide patients with resources to view laboratory results and communicate with physicians online. It is important for dermatologists to be involved in the development of high-quality online content that educates the public while also emphasizing the need to seek in-person medical care, particularly in potential cases of skin cancer. It also is important for patients to be involved in the content development process to ensure that the messages they take away from online resources are the ones physicians wish to convey. Ideally, online forms of education will increase patients’ sense of self-efficacy while encouraging appropriate consultation for potentially harmful skin conditions.

1. Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the Internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e4.

2. Ybarra M, Suman M. Reasons, assessments and actions taken: sex and age differences in uses of Internet health information. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:512-521.

3. Bhandari N, Shi Y, Jung K. Seeking health information online: does limited healthcare access matter? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:1113-1117.

4. Thackeray R, Crookston BT, West JH. Correlates of health-related social media use among adults. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e21.

5. Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Akilov O, et al. Diagnostic inaccuracy of smartphone applications for melanoma detection. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:422-426.

6. Kortum P, Edwards C, Richards-Kortum R. The impact of inaccurate Internet health information in a secondary school learning environment. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e17.

7. Mead N, Varnam R, Rogers A, et al. What predicts patients’ interest in the internet as a health resource in primary care in England? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8:33-39.

1. Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the Internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e4.

2. Ybarra M, Suman M. Reasons, assessments and actions taken: sex and age differences in uses of Internet health information. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:512-521.

3. Bhandari N, Shi Y, Jung K. Seeking health information online: does limited healthcare access matter? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:1113-1117.

4. Thackeray R, Crookston BT, West JH. Correlates of health-related social media use among adults. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e21.

5. Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Akilov O, et al. Diagnostic inaccuracy of smartphone applications for melanoma detection. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:422-426.

6. Kortum P, Edwards C, Richards-Kortum R. The impact of inaccurate Internet health information in a secondary school learning environment. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e17.

7. Mead N, Varnam R, Rogers A, et al. What predicts patients’ interest in the internet as a health resource in primary care in England? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8:33-39.

Black Salve and Bloodroot Extract in Dermatologic Conditions

Black salve is composed of various ingredients, many of which are inert; however, some black salves contain escharotics, the 2 most common are zinc chloride and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) extract. In high doses, such as those contained in most black salve products, these corrosive agents can indiscriminately damage both healthy and diseased tissue.1 Nevertheless, many black salve products currently are advertised as safe and natural methods for curing skin cancer2-4 or treating a variety of other skin conditions (eg, moles, warts, skin tags, boils, abscesses, bee stings, other minor wounds)1,5 and even nondermatologic conditions such as a sore throat.6 Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies. Black salve is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions. We report the case of application of black salve to a biopsy site of a compound nevus with moderate atypia that resulted in the formation of a dermatitis plaque with subsequent scarring and basal layer pigmentation.

Case Report

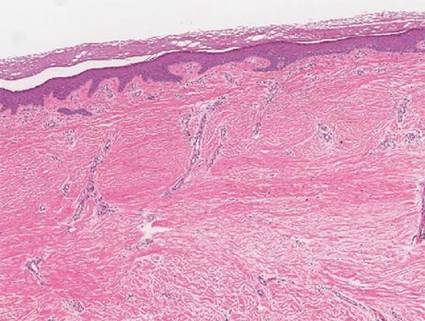

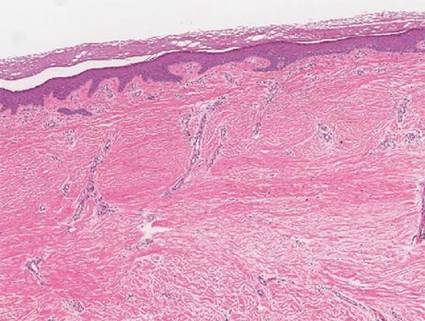

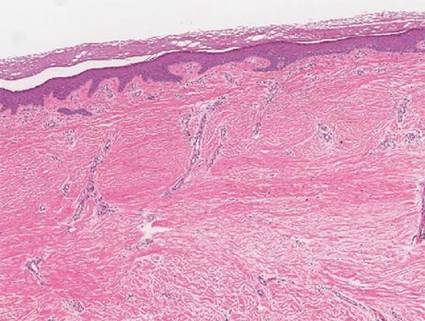

A 35-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma presented for follow-up of a compound nevus with moderate atypia on the right anterior thigh that had been biopsied 6 months prior. Complete excision of the lesion was recommended at the initial presentation but was not performed due to scheduling conflicts. The patient reported applying black salve to the biopsy site and also to the left thigh 3 months later. There was no reaction on the left thigh after one 24-hour application of black salve, but an area around the biopsy site on the right thigh became thickened and irritated with superficial erosion of the skin following 2 applications of black salve, each of 24 hours’ duration. Physical examination revealed a granulomatous plaque at the biopsy site that was approximately 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). One year later the lesion had completely healed (Figure 1B) and a biopsy revealed scarring with basal layer pigmentation (Figure 2).

|

|

| |||

| Figure 1. A 5-cm granulomatous reaction surrounding a biopsy site on the right anterior thigh 3 months after application of black salve (A). One year later, the lesion had completely healed (B). | Figure 2. A biopsy one year following application of black salve demonstrated scarring with basal layer pigmentation (H&E, original magnification ×4). | ||||

Comment

A Web search using the term black salve yields a large number of products labeled as skin cancer salves, many showing glowing reviews and some being sold by major US retailers. The ingredients in black salves often vary in the innocuous substances they contain, but most products include the escharotics zinc chloride and bloodroot extract, which is derived from the plant S canadensis.1,3 For example, the ingredients of one popular black salve product include zinc chloride, chaparral (active ingredient is nordihydroguaiaretic acid), graviola leaf extract, oleander leaf extract, bloodroot extract, and glycerine,7 while another product includes bloodroot extract, zinc chloride, chaparral, cayenne pepper, red clover, birch bark, dimethyl sulfoxide, and burdock root.4

Bloodroot extract’s antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects derive from its benzylisoquinoline alkaloids including sanguinarine, allocryptopine, berberine, coptisine, protopine, and stylopine.3,8 Bloodroot extract possesses some degree of tumoricidal potency, with one study finding that it selectively targets cancer cells.9 However, this differential response is seen only at low doses and not at the high concentrations contained in most black salve products.1 According to fluorometric assays, sanguinarine is not selective for tumor cells and therefore damages healthy tissue in addition to the unwanted lesions.6,10,11 The US Food and Drug Administration includes black salve products on its list of fake cancer cures that consumers should avoid.12 Reports of extensive damage from black salve use include skin ulceration2,10 and complete loss of a naris1 and nasal ala.5 Our case suggests the possible association between black salve use and an irritant reaction and erosion of the skin.

Furthermore, reliance on black salve alone in the treatment of skin cancer poses the threat of recurrence or metastasis of cancer because there is no way to know if the salve completely removed the cancer without a biopsy. Self-treatment can delay more effective therapy and may require further treatments.

Black salve should be subject to standarddrug regulations and its use discouraged by dermatologists due to the associated harmful effects and the availability of safer treatments. To better treat and inform their patients, dermatologists should be aware that patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves.

1. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289.