User login

Office hysteroscopic evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

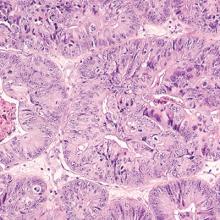

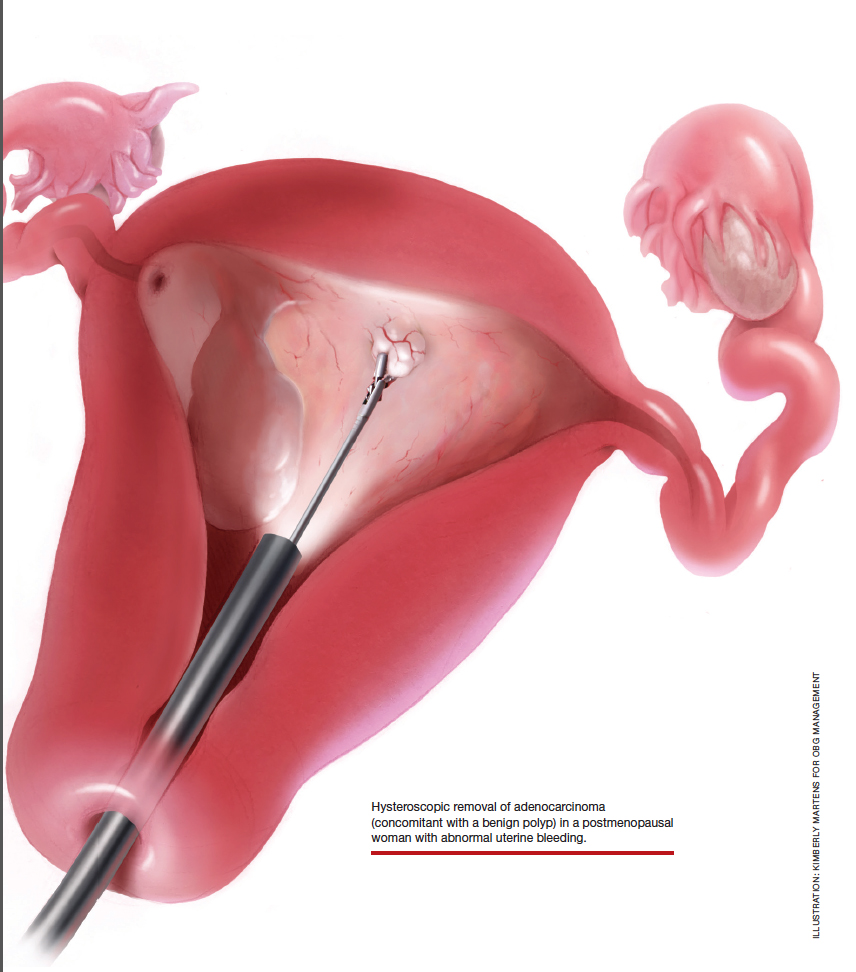

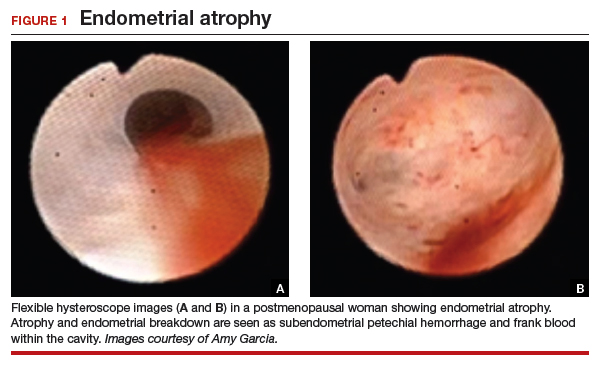

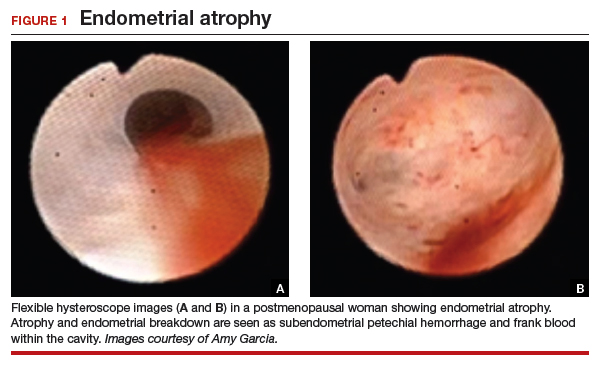

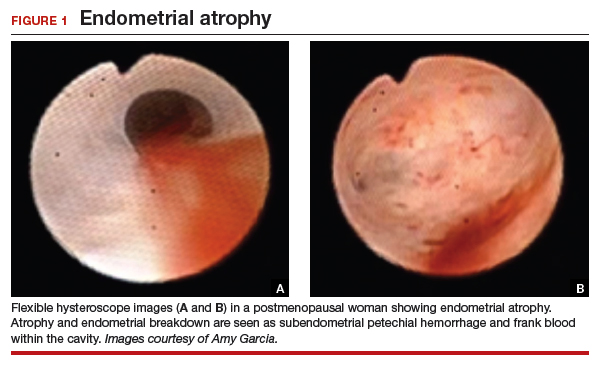

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Transvaginal ultrasound

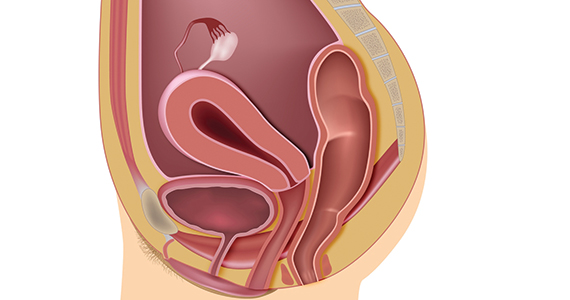

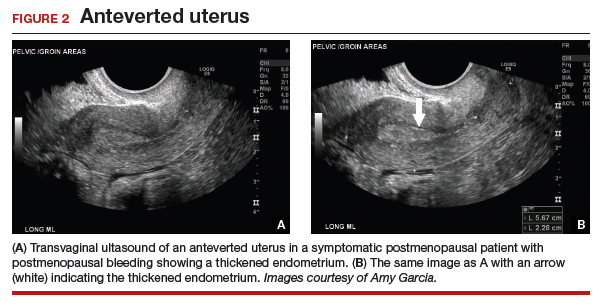

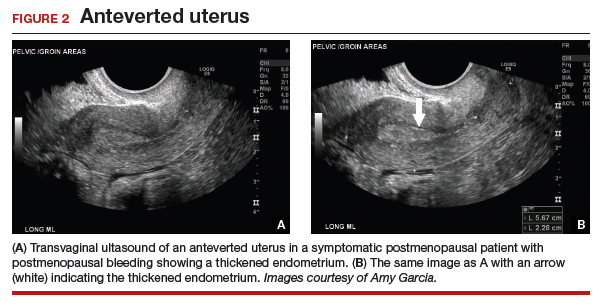

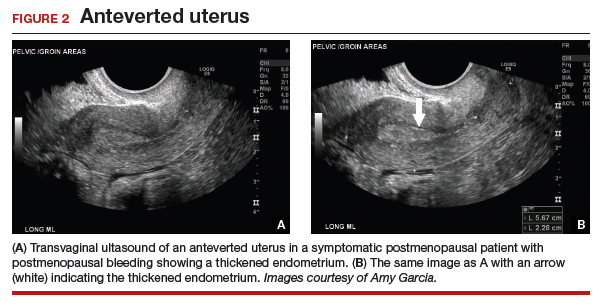

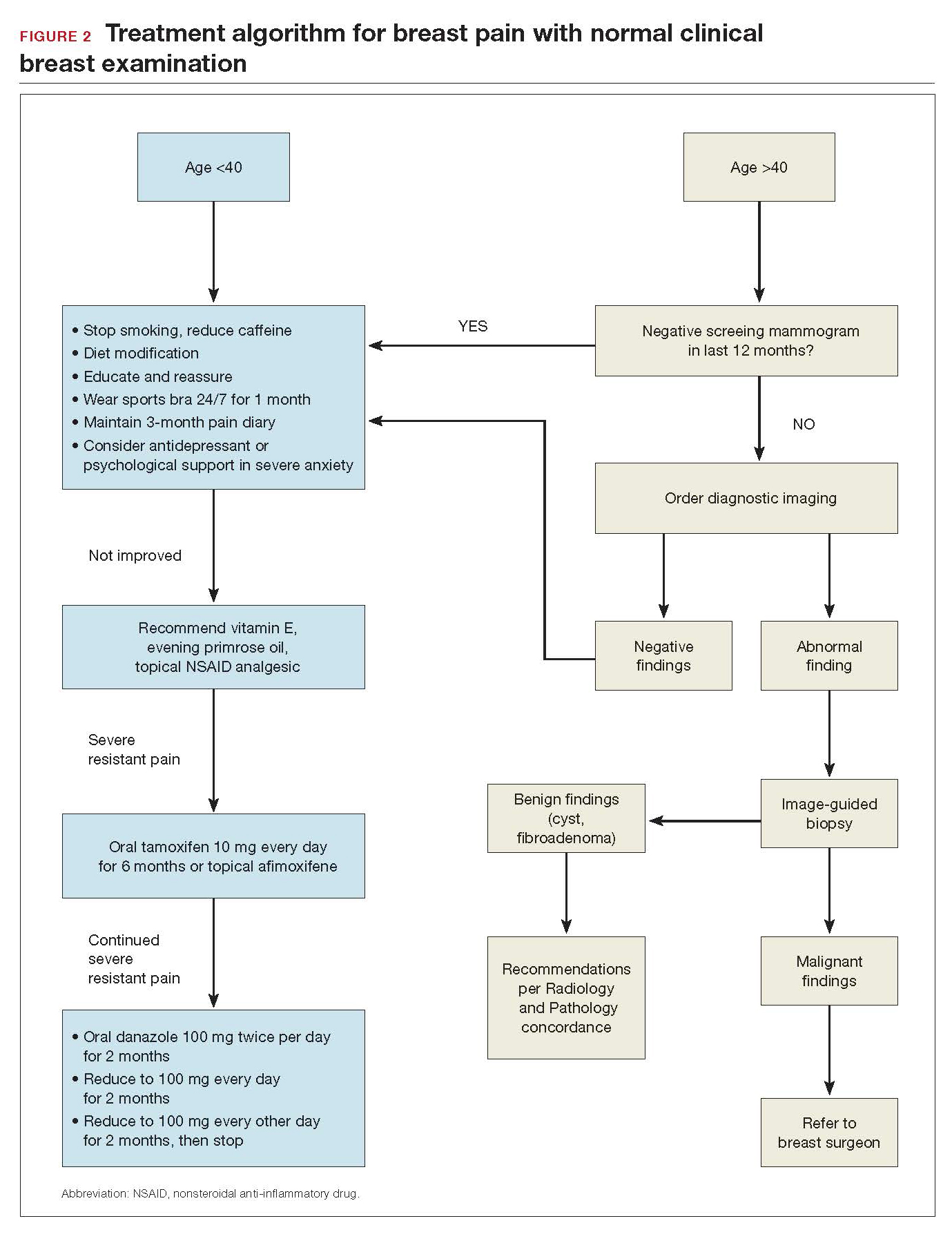

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

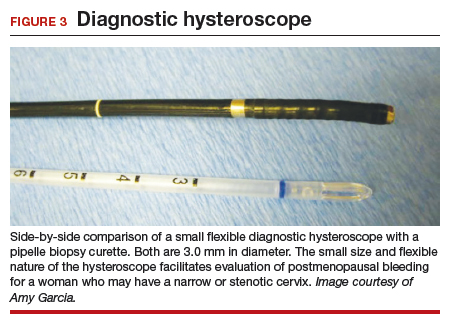

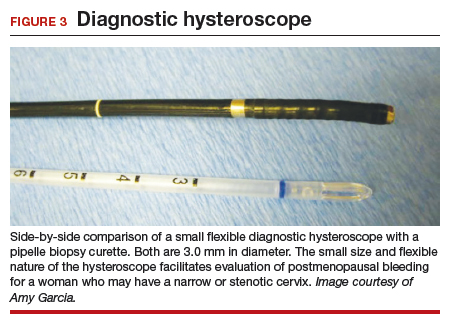

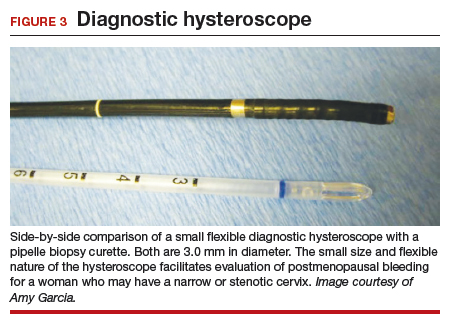

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9

A common occurrence in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is an initial TVUS finding of an enlarged endometrium and an endometrial biopsy that is negative or reveals scant or insufficient tissue. Unfortunately, the diagnostic evaluation process often stops here, and a diagnosis for the PMB is never actually identified. Here are several clinical scenarios that highlight the need for hysteroscopy in the initial evaluation of PMB, especially when there is a discordance between transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and endometrial biopsy findings.

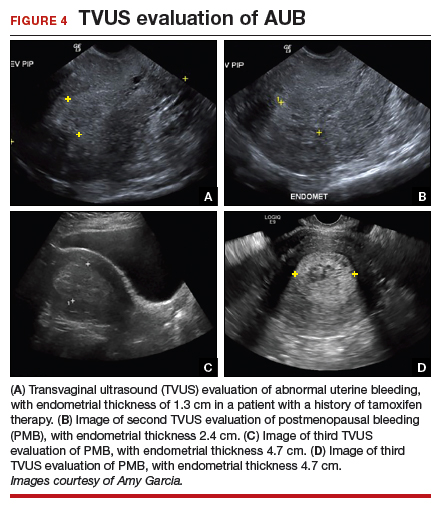

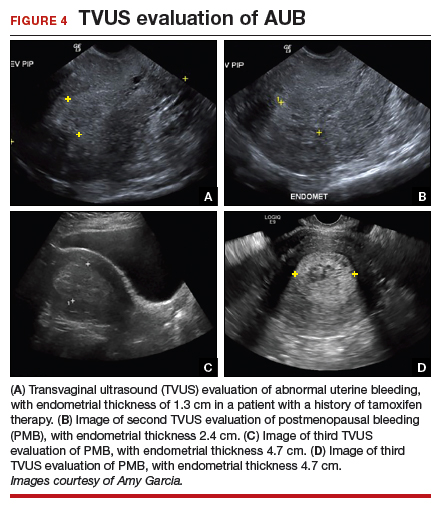

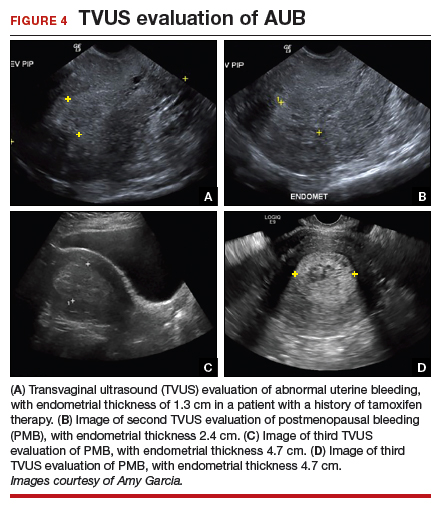

Patient 1: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with benign findings

The patient is a 52-year-old woman who presented to her gynecologist reporting abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). She has a history of breast cancer, and she completed tamoxifen treatment. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed; an enlarged endometrial stripe of 1.3 cm was found (FIGURE 4A). Endometrial biopsy was performed, showing adequate tissue but with a negative result. The patient is told that she is likely perimenopausal, which is the reason for her bleeding.

At the time of referral, the patient is evaluated with in-office hysteroscopy. Diagnosis of a 5 cm x 7 cm benign endometrial polyp is made. An uneventful hysteroscopic polypectomy is performed (VIDEO 2).

Video 2

This scenario illustrates the shortcoming of initial evaluation by not performing a hysteroscopy, especially in a woman with a thickened endometrium with previous tamoxifen therapy. Subsequent visits failed to correlate bleeding etiology with discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy results with hysteroscopy, and no hysteroscopy was performed in the operating room at the time of D&C.

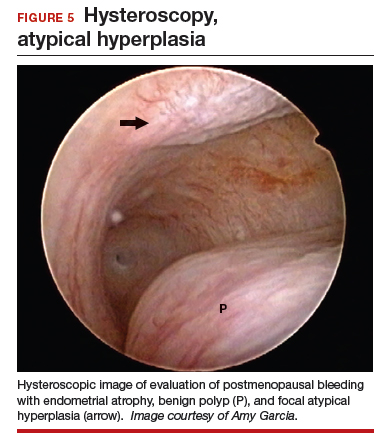

Patient 2: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with premalignant findings

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who had incidental findings of a thickened endometrium on computed tomography scan of the pelvis. TVUS confirmed a thickened endometrium measuring 17 mm, and an endometrial biopsy showed scant tissue.

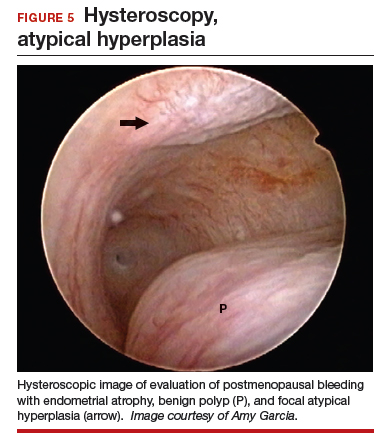

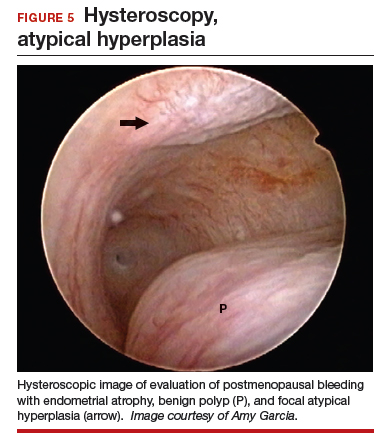

At the time of referral, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in the office. Endometrial atrophy, a large benign appearing polyp, and focal abnormal appearing tissue were seen (FIGURE 5). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology findings confirmed benign polyp and atypical hyperplasia (VIDEO 3).

Video 3

This scenario illustrates that while the patient was asymptomatic, there was discordance between the TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy identified a benign endometrial polyp, which is common in asymptomatic postmenopausal patients with a thickened endometrium and endometrial biopsy showing scant tissue. However, addition of the diagnostic hysteroscopy identified focal precancerous tissue, removed under directed biopsy.

Patient 3: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with malignant findings

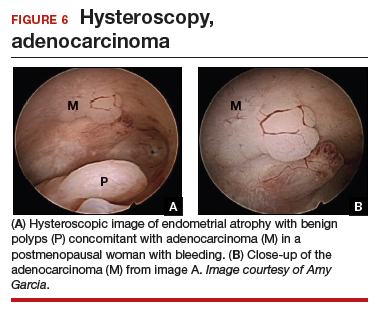

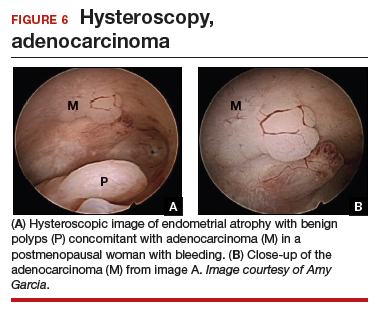

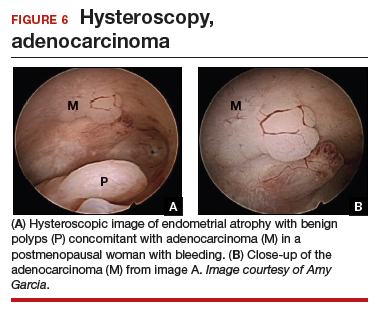

The patient is a 68-year-old woman with PMB. TVUS showed a thickened endometrium measuring 14 mm. An endometrial biopsy was negative, showing scant tissue. No additional diagnostic evaluation or management was offered.

Video 4A

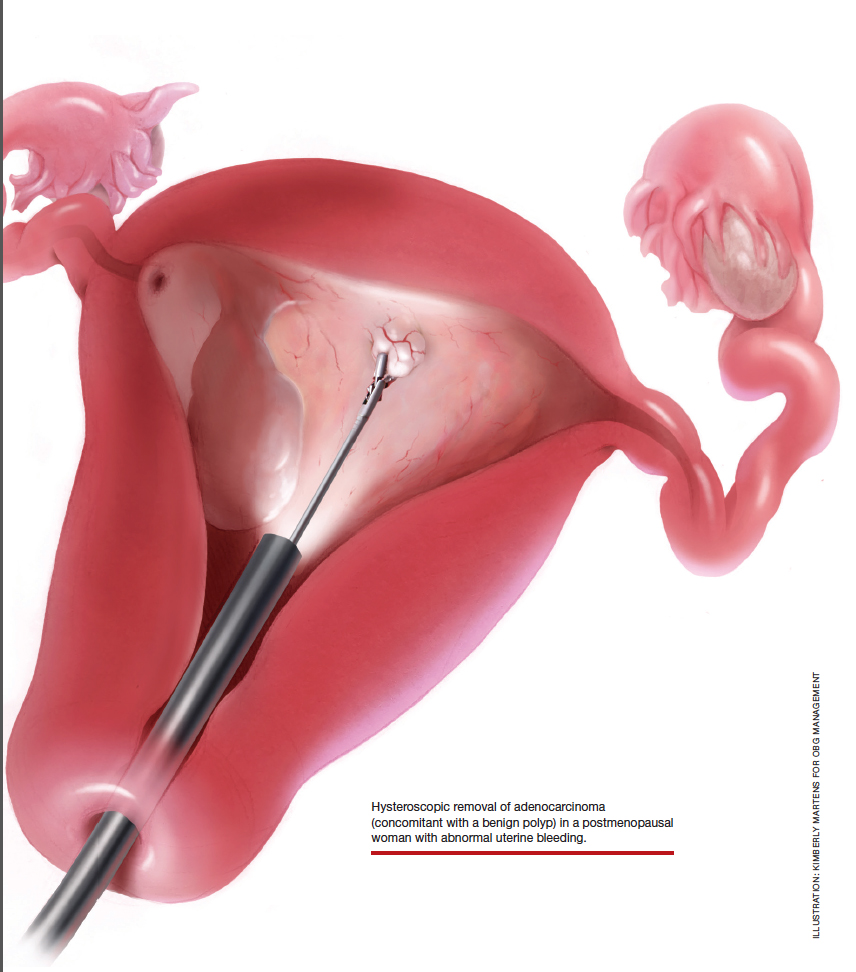

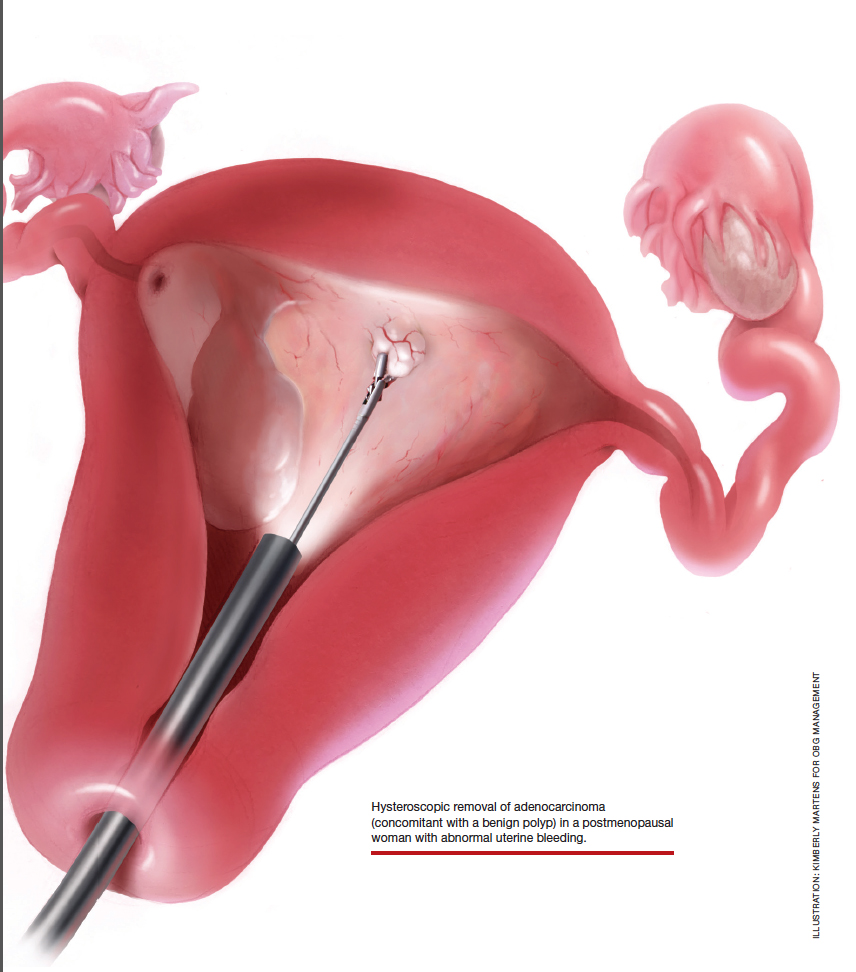

At the time of referral, the patient was evaluated with in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy, and the patient was found to have endometrial atrophy, benign appearing polyps, and focal abnormal tissue (FIGURE 6). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology confirmed benign polyps and grade 1 adenocarcinoma (VIDEOS 4A, 4B, 4C).

Video 4B

This scenario illustrates the possibility of having multiple endometrial pathologies present at the time of discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy plays a critical role in additional evaluation and diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma with directed biopsy, especially in a symptomatic woman with PMB.

Video 4C

Conclusion

Evaluation of PMB begins with a screening TVUS. Findings of an endometrium of ≤4 mm indicate a very low likelihood of the presence of endometrial cancer, and treatment for atrophy or changes to hormone replacement therapy regimen is reasonable first-line management; endometrial biopsy is not recommended. For patients with persistent PMB or thickened endometrium ≥4 mm on TVUS, biopsy sampling of the endometrium should be performed. If the endometrial biopsy does not explain the etiology of the PMB with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, then hysteroscopy should be performed to evaluate for focal endometrial disease and possible directed biopsy.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e124-e129.

- Goldstein SR. Appropriate evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Menopause. 2018;25:1476-1478.

- Bel S, Billard C, Godet J, et al. Risk of malignancy on suspicion of polyps in menopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:138-142.

- Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-155.

- Embracing hysteroscopy. September 6, 2017. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/embracing-hysteroscopy/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Chang YN, Zhang Y, Wang LP, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong WM, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174226.

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Transvaginal ultrasound

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9

A common occurrence in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is an initial TVUS finding of an enlarged endometrium and an endometrial biopsy that is negative or reveals scant or insufficient tissue. Unfortunately, the diagnostic evaluation process often stops here, and a diagnosis for the PMB is never actually identified. Here are several clinical scenarios that highlight the need for hysteroscopy in the initial evaluation of PMB, especially when there is a discordance between transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and endometrial biopsy findings.

Patient 1: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with benign findings

The patient is a 52-year-old woman who presented to her gynecologist reporting abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). She has a history of breast cancer, and she completed tamoxifen treatment. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed; an enlarged endometrial stripe of 1.3 cm was found (FIGURE 4A). Endometrial biopsy was performed, showing adequate tissue but with a negative result. The patient is told that she is likely perimenopausal, which is the reason for her bleeding.

At the time of referral, the patient is evaluated with in-office hysteroscopy. Diagnosis of a 5 cm x 7 cm benign endometrial polyp is made. An uneventful hysteroscopic polypectomy is performed (VIDEO 2).

Video 2

This scenario illustrates the shortcoming of initial evaluation by not performing a hysteroscopy, especially in a woman with a thickened endometrium with previous tamoxifen therapy. Subsequent visits failed to correlate bleeding etiology with discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy results with hysteroscopy, and no hysteroscopy was performed in the operating room at the time of D&C.

Patient 2: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with premalignant findings

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who had incidental findings of a thickened endometrium on computed tomography scan of the pelvis. TVUS confirmed a thickened endometrium measuring 17 mm, and an endometrial biopsy showed scant tissue.

At the time of referral, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in the office. Endometrial atrophy, a large benign appearing polyp, and focal abnormal appearing tissue were seen (FIGURE 5). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology findings confirmed benign polyp and atypical hyperplasia (VIDEO 3).

Video 3

This scenario illustrates that while the patient was asymptomatic, there was discordance between the TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy identified a benign endometrial polyp, which is common in asymptomatic postmenopausal patients with a thickened endometrium and endometrial biopsy showing scant tissue. However, addition of the diagnostic hysteroscopy identified focal precancerous tissue, removed under directed biopsy.

Patient 3: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with malignant findings

The patient is a 68-year-old woman with PMB. TVUS showed a thickened endometrium measuring 14 mm. An endometrial biopsy was negative, showing scant tissue. No additional diagnostic evaluation or management was offered.

Video 4A

At the time of referral, the patient was evaluated with in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy, and the patient was found to have endometrial atrophy, benign appearing polyps, and focal abnormal tissue (FIGURE 6). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology confirmed benign polyps and grade 1 adenocarcinoma (VIDEOS 4A, 4B, 4C).

Video 4B

This scenario illustrates the possibility of having multiple endometrial pathologies present at the time of discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy plays a critical role in additional evaluation and diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma with directed biopsy, especially in a symptomatic woman with PMB.

Video 4C

Conclusion

Evaluation of PMB begins with a screening TVUS. Findings of an endometrium of ≤4 mm indicate a very low likelihood of the presence of endometrial cancer, and treatment for atrophy or changes to hormone replacement therapy regimen is reasonable first-line management; endometrial biopsy is not recommended. For patients with persistent PMB or thickened endometrium ≥4 mm on TVUS, biopsy sampling of the endometrium should be performed. If the endometrial biopsy does not explain the etiology of the PMB with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, then hysteroscopy should be performed to evaluate for focal endometrial disease and possible directed biopsy.

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Transvaginal ultrasound

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9

A common occurrence in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is an initial TVUS finding of an enlarged endometrium and an endometrial biopsy that is negative or reveals scant or insufficient tissue. Unfortunately, the diagnostic evaluation process often stops here, and a diagnosis for the PMB is never actually identified. Here are several clinical scenarios that highlight the need for hysteroscopy in the initial evaluation of PMB, especially when there is a discordance between transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and endometrial biopsy findings.

Patient 1: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with benign findings

The patient is a 52-year-old woman who presented to her gynecologist reporting abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). She has a history of breast cancer, and she completed tamoxifen treatment. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed; an enlarged endometrial stripe of 1.3 cm was found (FIGURE 4A). Endometrial biopsy was performed, showing adequate tissue but with a negative result. The patient is told that she is likely perimenopausal, which is the reason for her bleeding.

At the time of referral, the patient is evaluated with in-office hysteroscopy. Diagnosis of a 5 cm x 7 cm benign endometrial polyp is made. An uneventful hysteroscopic polypectomy is performed (VIDEO 2).

Video 2

This scenario illustrates the shortcoming of initial evaluation by not performing a hysteroscopy, especially in a woman with a thickened endometrium with previous tamoxifen therapy. Subsequent visits failed to correlate bleeding etiology with discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy results with hysteroscopy, and no hysteroscopy was performed in the operating room at the time of D&C.

Patient 2: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with premalignant findings

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who had incidental findings of a thickened endometrium on computed tomography scan of the pelvis. TVUS confirmed a thickened endometrium measuring 17 mm, and an endometrial biopsy showed scant tissue.

At the time of referral, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in the office. Endometrial atrophy, a large benign appearing polyp, and focal abnormal appearing tissue were seen (FIGURE 5). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology findings confirmed benign polyp and atypical hyperplasia (VIDEO 3).

Video 3

This scenario illustrates that while the patient was asymptomatic, there was discordance between the TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy identified a benign endometrial polyp, which is common in asymptomatic postmenopausal patients with a thickened endometrium and endometrial biopsy showing scant tissue. However, addition of the diagnostic hysteroscopy identified focal precancerous tissue, removed under directed biopsy.

Patient 3: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with malignant findings

The patient is a 68-year-old woman with PMB. TVUS showed a thickened endometrium measuring 14 mm. An endometrial biopsy was negative, showing scant tissue. No additional diagnostic evaluation or management was offered.

Video 4A

At the time of referral, the patient was evaluated with in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy, and the patient was found to have endometrial atrophy, benign appearing polyps, and focal abnormal tissue (FIGURE 6). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology confirmed benign polyps and grade 1 adenocarcinoma (VIDEOS 4A, 4B, 4C).

Video 4B

This scenario illustrates the possibility of having multiple endometrial pathologies present at the time of discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy plays a critical role in additional evaluation and diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma with directed biopsy, especially in a symptomatic woman with PMB.

Video 4C

Conclusion

Evaluation of PMB begins with a screening TVUS. Findings of an endometrium of ≤4 mm indicate a very low likelihood of the presence of endometrial cancer, and treatment for atrophy or changes to hormone replacement therapy regimen is reasonable first-line management; endometrial biopsy is not recommended. For patients with persistent PMB or thickened endometrium ≥4 mm on TVUS, biopsy sampling of the endometrium should be performed. If the endometrial biopsy does not explain the etiology of the PMB with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, then hysteroscopy should be performed to evaluate for focal endometrial disease and possible directed biopsy.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e124-e129.

- Goldstein SR. Appropriate evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Menopause. 2018;25:1476-1478.

- Bel S, Billard C, Godet J, et al. Risk of malignancy on suspicion of polyps in menopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:138-142.

- Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-155.

- Embracing hysteroscopy. September 6, 2017. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/embracing-hysteroscopy/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Chang YN, Zhang Y, Wang LP, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong WM, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174226.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e124-e129.

- Goldstein SR. Appropriate evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Menopause. 2018;25:1476-1478.

- Bel S, Billard C, Godet J, et al. Risk of malignancy on suspicion of polyps in menopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:138-142.

- Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-155.

- Embracing hysteroscopy. September 6, 2017. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/embracing-hysteroscopy/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Chang YN, Zhang Y, Wang LP, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong WM, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174226.

Transdermal estradiol may modulate the relationship between sleep, cognition

LOS ANGELES – Estrogen therapy may have scored another goal in its comeback game, as a 7-year prospective study shows that a transdermal formulation preserves some measures of cognitive function and brain architecture in postmenopausal women.

In addition to performing better on subjective tests of memory, women using the estrogen patch experienced less cortical atrophy and were less likely to show amyloid on brain imaging. The observations were moderately associated with the improved sleep these women reported, Burcu Zeydan, MD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“By 7 years, among the cognitive domains studied ... [less brain and cognitive change] correlated with lower global sleep score, meaning better sleep quality in the estradiol group,” said Dr. Zeydan, assistant professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “We previously found that preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex over 7 years was associated with lower cortical beta-amyloid deposition on PET only in the estradiol group, pointing out the potential role of estrogen receptors in modulating this relationship.”

Dysregulated sleep is more common among women than men, particularly as menopause approaches and estrogen levels fluctuate, then decline, Dr. Zeydan said.

Dr. Zeydan reported the sleep substudy of KEEPS (the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study), a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multisite trial that compared oral conjugated equine estrogen with transdermal estradiol. A control group received oral placebo and a placebo patch.*

Brain architecture was similar between the placebo and transdermal groups, but it was actually worse in some measures in the oral-estrogen group, compared with the placebo group. Women taking oral estrogen had more white matter hyperintensities, greater ventricle enlargement, and more cortical thinning. Those differences resolved after they stopped taking the oral formulation, bringing them into line with the transdermal and placebo groups.

The investigation also found that the transdermal group showed lower cerebral amyloid binding on PET scans relative to both placebo and oral estrogen.

“The relative preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortical volume in the [transdermal estradiol] group over 7 years indicates that hormone therapy may have long-term effects on the brain,” the team concluded. They noted that the original KEEPS study didn’t find any cognitive correlation with these changes.

The subanalysis looked at 69 women of the KEEPS cohort who had been followed for the full 7 years (4 years on treatment and 3 years off treatment). They were randomized to oral placebo and a placebo patch,* oral conjugated equine estrogen (0.45 mg/day), or transdermal estradiol (50 mcg/day). Participants in the active treatment groups received oral micronized progesterone 12 days each month. All had complete data on cognitive testing and brain imaging. Sleep quality was measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Dr. Zeydan compared cognition and brain architecture findings in relation to the sleep score; lower scores mean better sleep.

The women were aged 42-58 years at baseline, and within 36 months from menopause. They had no history of menopausal hormone therapy or cardiovascular disease.

The investigators were particularly interested in how estrogen might have modulated the disturbed sleep patterns that often accompany perimenopause and early menopause, and whether the observed brain and cognitive changes tracked with sleep quality.

“During this time, 40% to 60% of women report problems sleeping, and estrogen decline seems to play an important role in sleep disturbances during this phase,” Dr. Zeydan said. “Although poor sleep quality is common in recently menopausal women, sleep quality improves with hormone therapy, as was previously demonstrated in KEEPS hormone therapy trial in recently menopausal women.”

By year 7, the cohort’s mean age was 61 years. The majority had at least some college education. The percentage who carried an apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 allele varied by group, with 15% positivity in the oral group, 48% in the transdermal group, and 16% in the placebo group.

Cognitive function was estimated with a global cognitive measure and four cognitive domain scores: verbal learning and memory, auditory attention and working memory, visual attention and executive function, and mental flexibility.

Higher attention and executive function scores were moderately correlated with a lower sleep score in the transdermal group (r = –0.54, a significant difference compared with the oral formulation). Lower sleep scores also showed a moderate correlation with preserved cortical volume of the dorsolateral prefrontal region (r = –0.47, also significantly different from the oral group).

Lower brain amyloid also positively correlated with better sleep. The correlation between sleep and global amyloid burden in the transdermal group was also moderate (r = 0.45), while the correlation in the oral group was significantly weaker (r = 0.18).

“We can say that sleep quality and transdermal estradiol during early postmenopausal years somehow interact to influence beta-amyloid deposition, preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume, and attention and executive function,” Dr. Zeydan said.

Dr. Zeydan had no financial disclosures.

*Correction, 8/7/2019: An earlier version of this story did not make clear that participants in the control group received oral placebo and a placebo patch.

LOS ANGELES – Estrogen therapy may have scored another goal in its comeback game, as a 7-year prospective study shows that a transdermal formulation preserves some measures of cognitive function and brain architecture in postmenopausal women.

In addition to performing better on subjective tests of memory, women using the estrogen patch experienced less cortical atrophy and were less likely to show amyloid on brain imaging. The observations were moderately associated with the improved sleep these women reported, Burcu Zeydan, MD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“By 7 years, among the cognitive domains studied ... [less brain and cognitive change] correlated with lower global sleep score, meaning better sleep quality in the estradiol group,” said Dr. Zeydan, assistant professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “We previously found that preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex over 7 years was associated with lower cortical beta-amyloid deposition on PET only in the estradiol group, pointing out the potential role of estrogen receptors in modulating this relationship.”

Dysregulated sleep is more common among women than men, particularly as menopause approaches and estrogen levels fluctuate, then decline, Dr. Zeydan said.

Dr. Zeydan reported the sleep substudy of KEEPS (the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study), a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multisite trial that compared oral conjugated equine estrogen with transdermal estradiol. A control group received oral placebo and a placebo patch.*

Brain architecture was similar between the placebo and transdermal groups, but it was actually worse in some measures in the oral-estrogen group, compared with the placebo group. Women taking oral estrogen had more white matter hyperintensities, greater ventricle enlargement, and more cortical thinning. Those differences resolved after they stopped taking the oral formulation, bringing them into line with the transdermal and placebo groups.

The investigation also found that the transdermal group showed lower cerebral amyloid binding on PET scans relative to both placebo and oral estrogen.

“The relative preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortical volume in the [transdermal estradiol] group over 7 years indicates that hormone therapy may have long-term effects on the brain,” the team concluded. They noted that the original KEEPS study didn’t find any cognitive correlation with these changes.

The subanalysis looked at 69 women of the KEEPS cohort who had been followed for the full 7 years (4 years on treatment and 3 years off treatment). They were randomized to oral placebo and a placebo patch,* oral conjugated equine estrogen (0.45 mg/day), or transdermal estradiol (50 mcg/day). Participants in the active treatment groups received oral micronized progesterone 12 days each month. All had complete data on cognitive testing and brain imaging. Sleep quality was measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Dr. Zeydan compared cognition and brain architecture findings in relation to the sleep score; lower scores mean better sleep.

The women were aged 42-58 years at baseline, and within 36 months from menopause. They had no history of menopausal hormone therapy or cardiovascular disease.

The investigators were particularly interested in how estrogen might have modulated the disturbed sleep patterns that often accompany perimenopause and early menopause, and whether the observed brain and cognitive changes tracked with sleep quality.

“During this time, 40% to 60% of women report problems sleeping, and estrogen decline seems to play an important role in sleep disturbances during this phase,” Dr. Zeydan said. “Although poor sleep quality is common in recently menopausal women, sleep quality improves with hormone therapy, as was previously demonstrated in KEEPS hormone therapy trial in recently menopausal women.”

By year 7, the cohort’s mean age was 61 years. The majority had at least some college education. The percentage who carried an apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 allele varied by group, with 15% positivity in the oral group, 48% in the transdermal group, and 16% in the placebo group.

Cognitive function was estimated with a global cognitive measure and four cognitive domain scores: verbal learning and memory, auditory attention and working memory, visual attention and executive function, and mental flexibility.

Higher attention and executive function scores were moderately correlated with a lower sleep score in the transdermal group (r = –0.54, a significant difference compared with the oral formulation). Lower sleep scores also showed a moderate correlation with preserved cortical volume of the dorsolateral prefrontal region (r = –0.47, also significantly different from the oral group).

Lower brain amyloid also positively correlated with better sleep. The correlation between sleep and global amyloid burden in the transdermal group was also moderate (r = 0.45), while the correlation in the oral group was significantly weaker (r = 0.18).

“We can say that sleep quality and transdermal estradiol during early postmenopausal years somehow interact to influence beta-amyloid deposition, preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume, and attention and executive function,” Dr. Zeydan said.

Dr. Zeydan had no financial disclosures.

*Correction, 8/7/2019: An earlier version of this story did not make clear that participants in the control group received oral placebo and a placebo patch.

LOS ANGELES – Estrogen therapy may have scored another goal in its comeback game, as a 7-year prospective study shows that a transdermal formulation preserves some measures of cognitive function and brain architecture in postmenopausal women.

In addition to performing better on subjective tests of memory, women using the estrogen patch experienced less cortical atrophy and were less likely to show amyloid on brain imaging. The observations were moderately associated with the improved sleep these women reported, Burcu Zeydan, MD, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“By 7 years, among the cognitive domains studied ... [less brain and cognitive change] correlated with lower global sleep score, meaning better sleep quality in the estradiol group,” said Dr. Zeydan, assistant professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “We previously found that preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex over 7 years was associated with lower cortical beta-amyloid deposition on PET only in the estradiol group, pointing out the potential role of estrogen receptors in modulating this relationship.”

Dysregulated sleep is more common among women than men, particularly as menopause approaches and estrogen levels fluctuate, then decline, Dr. Zeydan said.

Dr. Zeydan reported the sleep substudy of KEEPS (the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study), a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multisite trial that compared oral conjugated equine estrogen with transdermal estradiol. A control group received oral placebo and a placebo patch.*

Brain architecture was similar between the placebo and transdermal groups, but it was actually worse in some measures in the oral-estrogen group, compared with the placebo group. Women taking oral estrogen had more white matter hyperintensities, greater ventricle enlargement, and more cortical thinning. Those differences resolved after they stopped taking the oral formulation, bringing them into line with the transdermal and placebo groups.

The investigation also found that the transdermal group showed lower cerebral amyloid binding on PET scans relative to both placebo and oral estrogen.

“The relative preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortical volume in the [transdermal estradiol] group over 7 years indicates that hormone therapy may have long-term effects on the brain,” the team concluded. They noted that the original KEEPS study didn’t find any cognitive correlation with these changes.

The subanalysis looked at 69 women of the KEEPS cohort who had been followed for the full 7 years (4 years on treatment and 3 years off treatment). They were randomized to oral placebo and a placebo patch,* oral conjugated equine estrogen (0.45 mg/day), or transdermal estradiol (50 mcg/day). Participants in the active treatment groups received oral micronized progesterone 12 days each month. All had complete data on cognitive testing and brain imaging. Sleep quality was measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Dr. Zeydan compared cognition and brain architecture findings in relation to the sleep score; lower scores mean better sleep.

The women were aged 42-58 years at baseline, and within 36 months from menopause. They had no history of menopausal hormone therapy or cardiovascular disease.

The investigators were particularly interested in how estrogen might have modulated the disturbed sleep patterns that often accompany perimenopause and early menopause, and whether the observed brain and cognitive changes tracked with sleep quality.

“During this time, 40% to 60% of women report problems sleeping, and estrogen decline seems to play an important role in sleep disturbances during this phase,” Dr. Zeydan said. “Although poor sleep quality is common in recently menopausal women, sleep quality improves with hormone therapy, as was previously demonstrated in KEEPS hormone therapy trial in recently menopausal women.”

By year 7, the cohort’s mean age was 61 years. The majority had at least some college education. The percentage who carried an apolipoprotein E epsilon-4 allele varied by group, with 15% positivity in the oral group, 48% in the transdermal group, and 16% in the placebo group.

Cognitive function was estimated with a global cognitive measure and four cognitive domain scores: verbal learning and memory, auditory attention and working memory, visual attention and executive function, and mental flexibility.

Higher attention and executive function scores were moderately correlated with a lower sleep score in the transdermal group (r = –0.54, a significant difference compared with the oral formulation). Lower sleep scores also showed a moderate correlation with preserved cortical volume of the dorsolateral prefrontal region (r = –0.47, also significantly different from the oral group).

Lower brain amyloid also positively correlated with better sleep. The correlation between sleep and global amyloid burden in the transdermal group was also moderate (r = 0.45), while the correlation in the oral group was significantly weaker (r = 0.18).

“We can say that sleep quality and transdermal estradiol during early postmenopausal years somehow interact to influence beta-amyloid deposition, preservation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume, and attention and executive function,” Dr. Zeydan said.

Dr. Zeydan had no financial disclosures.

*Correction, 8/7/2019: An earlier version of this story did not make clear that participants in the control group received oral placebo and a placebo patch.

REPORTING FROM AAIC 2019

CVD risk upped in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors

according to a new study of nearly 300 women.

Previous studies have shown that cardiovascular risk is greater among postmenopausal women treated for breast cancer compared with those without cancer, but specific risk factors have not been well studied, wrote Daniel de Araujo Brito Buttros, MD, of Paulista State University, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and colleagues.

In a study published in Menopause, the researchers evaluated several CVD risk factors in 96 postmenopausal women with breast cancer and 192 women without breast cancer, including metabolic syndrome, subclinical atherosclerosis, and heat shock proteins (HSP) 60 and 70.

Overall, breast cancer patients had significantly higher HSP60 levels and lower HSP70 levels than those of their cancer-free peers. These two proteins have an antagonistic relationship in cardiovascular disease, with HSP60 considered a risk factor for CVD, and HSP70 considered a protective factor. Average HSP60 levels for the breast cancer and control groups were 35 ng/mL and 10.8 ng/mL, respectively; average HSP70 levels were 0.5 ng/mL and 1.3 ng/mL, respectively.

Both diabetes and metabolic syndrome were significantly more common among breast cancer patients vs. controls (19.8% vs. 6.8% and 54.2% vs. 30.7%, respectively). Carotid artery plaque also was more common in breast cancer patients vs. controls (19.8% vs. 9.4%, respectively, P = 0.013).

In addition, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels were significantly higher among the breast cancer patients, as were triglycerides and glucose.

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design that could not prove a causal relationship between CVD risk and breast cancer, the researchers noted.

However, the results demonstrate the increased CVD risk for breast cancer patients, and “[therefore], women diagnosed with breast cancer might receive multidisciplinary care, including cardiology consultation at the time of breast cancer diagnosis and also during oncologic follow-up visits,” they said.

“Heart disease appears more commonly in women treated for breast cancer because of the toxicities of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and use of aromatase inhibitors, which lower estrogen. Heart-healthy lifestyle modifications will decrease both the risk of recurrent breast cancer and the risk of developing heart disease,” JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, executive director of the North American Menopause Society, said in a statement. “Women should schedule a cardiology consultation when breast cancer is diagnosed and continue with ongoing follow-up after cancer treatments are completed,” she emphasized.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Buttros DAB et al. Menopause. 2019. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001348.

according to a new study of nearly 300 women.

Previous studies have shown that cardiovascular risk is greater among postmenopausal women treated for breast cancer compared with those without cancer, but specific risk factors have not been well studied, wrote Daniel de Araujo Brito Buttros, MD, of Paulista State University, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and colleagues.

In a study published in Menopause, the researchers evaluated several CVD risk factors in 96 postmenopausal women with breast cancer and 192 women without breast cancer, including metabolic syndrome, subclinical atherosclerosis, and heat shock proteins (HSP) 60 and 70.

Overall, breast cancer patients had significantly higher HSP60 levels and lower HSP70 levels than those of their cancer-free peers. These two proteins have an antagonistic relationship in cardiovascular disease, with HSP60 considered a risk factor for CVD, and HSP70 considered a protective factor. Average HSP60 levels for the breast cancer and control groups were 35 ng/mL and 10.8 ng/mL, respectively; average HSP70 levels were 0.5 ng/mL and 1.3 ng/mL, respectively.

Both diabetes and metabolic syndrome were significantly more common among breast cancer patients vs. controls (19.8% vs. 6.8% and 54.2% vs. 30.7%, respectively). Carotid artery plaque also was more common in breast cancer patients vs. controls (19.8% vs. 9.4%, respectively, P = 0.013).

In addition, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels were significantly higher among the breast cancer patients, as were triglycerides and glucose.

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design that could not prove a causal relationship between CVD risk and breast cancer, the researchers noted.

However, the results demonstrate the increased CVD risk for breast cancer patients, and “[therefore], women diagnosed with breast cancer might receive multidisciplinary care, including cardiology consultation at the time of breast cancer diagnosis and also during oncologic follow-up visits,” they said.

“Heart disease appears more commonly in women treated for breast cancer because of the toxicities of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and use of aromatase inhibitors, which lower estrogen. Heart-healthy lifestyle modifications will decrease both the risk of recurrent breast cancer and the risk of developing heart disease,” JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, executive director of the North American Menopause Society, said in a statement. “Women should schedule a cardiology consultation when breast cancer is diagnosed and continue with ongoing follow-up after cancer treatments are completed,” she emphasized.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Buttros DAB et al. Menopause. 2019. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001348.

according to a new study of nearly 300 women.

Previous studies have shown that cardiovascular risk is greater among postmenopausal women treated for breast cancer compared with those without cancer, but specific risk factors have not been well studied, wrote Daniel de Araujo Brito Buttros, MD, of Paulista State University, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and colleagues.

In a study published in Menopause, the researchers evaluated several CVD risk factors in 96 postmenopausal women with breast cancer and 192 women without breast cancer, including metabolic syndrome, subclinical atherosclerosis, and heat shock proteins (HSP) 60 and 70.

Overall, breast cancer patients had significantly higher HSP60 levels and lower HSP70 levels than those of their cancer-free peers. These two proteins have an antagonistic relationship in cardiovascular disease, with HSP60 considered a risk factor for CVD, and HSP70 considered a protective factor. Average HSP60 levels for the breast cancer and control groups were 35 ng/mL and 10.8 ng/mL, respectively; average HSP70 levels were 0.5 ng/mL and 1.3 ng/mL, respectively.

Both diabetes and metabolic syndrome were significantly more common among breast cancer patients vs. controls (19.8% vs. 6.8% and 54.2% vs. 30.7%, respectively). Carotid artery plaque also was more common in breast cancer patients vs. controls (19.8% vs. 9.4%, respectively, P = 0.013).

In addition, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels were significantly higher among the breast cancer patients, as were triglycerides and glucose.

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design that could not prove a causal relationship between CVD risk and breast cancer, the researchers noted.

However, the results demonstrate the increased CVD risk for breast cancer patients, and “[therefore], women diagnosed with breast cancer might receive multidisciplinary care, including cardiology consultation at the time of breast cancer diagnosis and also during oncologic follow-up visits,” they said.

“Heart disease appears more commonly in women treated for breast cancer because of the toxicities of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and use of aromatase inhibitors, which lower estrogen. Heart-healthy lifestyle modifications will decrease both the risk of recurrent breast cancer and the risk of developing heart disease,” JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, executive director of the North American Menopause Society, said in a statement. “Women should schedule a cardiology consultation when breast cancer is diagnosed and continue with ongoing follow-up after cancer treatments are completed,” she emphasized.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Buttros DAB et al. Menopause. 2019. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001348.

FROM MENOPAUSE

An app to help women and clinicians manage menopausal symptoms

In North America, women experience menopause (the permanent cessation of menstruation due to loss of ovarian activity) at a median age of 51 years. They may experience symptoms of perimenopause, or the menopause transition, for several years before menstruation ceases. Menopausal symptoms include vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes, and vaginal symptoms, such as vaginal dryness and pain during intercourse.1

Women may have questions about treating menopausal symptoms, maintaining their health, and preventing such age-related diseases as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. The decision to treat menopausal symptoms is challenging for women as well as their clinicians given that recommendations have changed over the past few years.

A free app with multiple features. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has developed a no-cost mobile health application called MenoPro for menopausal symptom management based on the organization’s 2017 recommendations.2 The app has 2 modes: one for clinicians and one for women/patients to support shared decision making.

For clinicians, the app helps identify which patients with menopausal symptoms are candidates for pharmacologic treatment and the options for optimal therapy. The app also can be used to calculate a 10-year cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) risk assessment. In addition, it contains links to a breast cancer risk assessment as well as an osteoporosis/bone fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX model calculator). Finally, MenoPro includes NAMS’s educational materials and information pages on lifestyle modifications to reduce hot flushes, contraindications and cautions to hormone therapy, pros and cons of hormonal versus nonhormonal options, a comparison of oral (pills) and transdermal (patches, gels, sprays) therapies, treatment options for vaginal dryness and pain with sexual activities, and direct links to tables with the various formulations and doses of medications.

The TABLE details the features of the MenoPro app based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3 I hope that the app described here will assist you in caring for women in the menopausal transition.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

2. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2018;25:13621387.

3. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

In North America, women experience menopause (the permanent cessation of menstruation due to loss of ovarian activity) at a median age of 51 years. They may experience symptoms of perimenopause, or the menopause transition, for several years before menstruation ceases. Menopausal symptoms include vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes, and vaginal symptoms, such as vaginal dryness and pain during intercourse.1

Women may have questions about treating menopausal symptoms, maintaining their health, and preventing such age-related diseases as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. The decision to treat menopausal symptoms is challenging for women as well as their clinicians given that recommendations have changed over the past few years.

A free app with multiple features. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has developed a no-cost mobile health application called MenoPro for menopausal symptom management based on the organization’s 2017 recommendations.2 The app has 2 modes: one for clinicians and one for women/patients to support shared decision making.

For clinicians, the app helps identify which patients with menopausal symptoms are candidates for pharmacologic treatment and the options for optimal therapy. The app also can be used to calculate a 10-year cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) risk assessment. In addition, it contains links to a breast cancer risk assessment as well as an osteoporosis/bone fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX model calculator). Finally, MenoPro includes NAMS’s educational materials and information pages on lifestyle modifications to reduce hot flushes, contraindications and cautions to hormone therapy, pros and cons of hormonal versus nonhormonal options, a comparison of oral (pills) and transdermal (patches, gels, sprays) therapies, treatment options for vaginal dryness and pain with sexual activities, and direct links to tables with the various formulations and doses of medications.

The TABLE details the features of the MenoPro app based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3 I hope that the app described here will assist you in caring for women in the menopausal transition.

In North America, women experience menopause (the permanent cessation of menstruation due to loss of ovarian activity) at a median age of 51 years. They may experience symptoms of perimenopause, or the menopause transition, for several years before menstruation ceases. Menopausal symptoms include vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes, and vaginal symptoms, such as vaginal dryness and pain during intercourse.1

Women may have questions about treating menopausal symptoms, maintaining their health, and preventing such age-related diseases as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. The decision to treat menopausal symptoms is challenging for women as well as their clinicians given that recommendations have changed over the past few years.

A free app with multiple features. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has developed a no-cost mobile health application called MenoPro for menopausal symptom management based on the organization’s 2017 recommendations.2 The app has 2 modes: one for clinicians and one for women/patients to support shared decision making.

For clinicians, the app helps identify which patients with menopausal symptoms are candidates for pharmacologic treatment and the options for optimal therapy. The app also can be used to calculate a 10-year cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) risk assessment. In addition, it contains links to a breast cancer risk assessment as well as an osteoporosis/bone fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX model calculator). Finally, MenoPro includes NAMS’s educational materials and information pages on lifestyle modifications to reduce hot flushes, contraindications and cautions to hormone therapy, pros and cons of hormonal versus nonhormonal options, a comparison of oral (pills) and transdermal (patches, gels, sprays) therapies, treatment options for vaginal dryness and pain with sexual activities, and direct links to tables with the various formulations and doses of medications.

The TABLE details the features of the MenoPro app based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3 I hope that the app described here will assist you in caring for women in the menopausal transition.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

2. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2018;25:13621387.

3. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

2. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2018;25:13621387.

3. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

2019 Update on menopause

Among peri- and postmenopausal women, abnormal bleeding, breast cancer, and mood disorders represent prevalent conditions. In this Update, we discuss data from a review that provides quantitative information on the likelihood of finding endometrial cancer among women with postmenopausal bleeding (PMB). We also summarize 2 recent consensus recommendations: One addresses the clinically important but controversial issue of the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in breast cancer survivors, and the other provides guidance on the management of depression in perimenopausal women.

Endometrial cancer is associated with a high prevalence of PMB

Clarke MA, Long BJ, Del Mar Morillo A, et al. Association of endometrial cancer risk with postmenopausal bleeding in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1210-1222.

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy and the fourth most common cancer among US women. In recent years, the incidence of and mortality from endometrial cancer have increased.1 Despite the high prevalence of endometrial cancer, population-based screening currently is not recommended.

PMB affects up to 10% of women and can be caused by endometrial atrophy, endometrial polyps, uterine leiomyoma, and malignancy. While it is well known that PMB is a common presenting symptom of endometrial cancer, we do not have good data to guide counseling patients with PMB on the likelihood that endometrial cancer is present. Similarly, estimates are lacking regarding what proportion of women with endometrial cancer will present with PMB.

To address these 2 issues, Clarke and colleagues conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of PMB among women with endometrial cancer (sensitivity) and the risk of endometrial cancer among women with PMB (positive predictive value). The authors included 129 studies--with 34,432 women with PMB and 6,358 with endometrial cancer--in their report.

Cancer prevalence varied with HT use, geographic location

The study findings demonstrated that the prevalence of PMB in women with endometrial cancer was 90% (95% confidence interval [CI], 84%-94%), and there was no significant difference in the occurrence of PMB by cancer stage. The risk of endometrial cancer in women with PMB ranged from 0% to 48%, yielding an overall pooled estimate of 9% (95% CI, 8%-11%). As an editorialist pointed out, the risk of endometrial cancer in women with PMB is similar to that of colorectal cancer in individuals with rectal bleeding (8%) and breast cancer in women with a palpable mass (10%), supporting current guidance that recommends evaluation of women with PMB.2 Evaluating 100 women with PMB to diagnose 9 endometrial cancers does not seem excessive.

Interestingly, among women with PMB, the prevalence of endometrial cancer was significantly higher among women not using hormone therapy (HT) than among users of HT (12% and 7%, respectively). In 7 studies restricted to women with PMB and polyps (n = 2,801), the pooled risk of endometrial cancer was 3% (95% CI, 3%-4%). In an analysis stratified by geographic region, a striking difference was noted in the risk of endometrial cancer among women with PMB in North America (5%), Northern Europe (7%), and in Western Europe (13%). This finding may be explained by regional differences in the approach to evaluating PMB, cultural perceptions of PMB that can affect thresholds to present for care, and differences in risk factors between these populations.

The study had several limitations, including an inability to evaluate the number of years since menopause and the effects of body mass index. Additionally, the study did not address endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.

PMB accounts for two-thirds of all gynecologic visits among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.3 This study revealed a 9% risk of endometrial cancer in patients experiencing PMB, which supports current practice guidelines to further evaluate and rule out endometrial cancer among all women presenting with PMB4; it also provides reassurance that targeting this high-risk group of women for early detection and prevention strategies will capture most cases of endometrial cancers. However, the relatively low positive predictive value of PMB emphasizes the need for additional triage tests with high specificity to improve management of PMB and minimize unnecessary biopsies in low-risk women.

Treating GSM in breast cancer survivors: New guidance targets QoL and sexuality

Faubion SS, Larkin LC, Stuenkel CA, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25:596-608.

Given that there is little evidence addressing the safety of vaginal estrogen, other hormonal therapies, and nonprescription treatments for GSM in breast cancer survivors, many survivors with bothersome GSM symptoms are not appropriately treated.

Continue to: Expert panel creates evidence-based guidance...

Expert panel creates evidence-based guidance

Against this backdrop, The North American Menopause Society and the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health convened a group comprised of menopause specialists (ObGyns, internists, and nurse practitioners), specialists in sexuality, medical oncologists specializing in breast cancer, and a psychologist to create evidence-based interdisciplinary consensus guidelines for enhancing quality of life and sexuality for breast cancer survivors with GSM.

Measures to help enhance quality of life and sexuality

The group's key recommendations for clinicians include: