User login

Childhood cancer survivors face several long-term risks

Chicago – Survivors of childhood cancers face several later risks from treatment, and investigators presented studies evaluating risks in three specific areas – secondary neoplasms, premature menopause, and neurocognitive function – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Discussant Paul Nathan, M.D., of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, said “the whole purpose” of research in this area “is to start to understand the predictors and modifiers of late effects” and then to design risk assessment tools and interventions to reduce long-term toxicity. These interventions include modification of chemotherapy and radiation doses, protective strategies, and disease risk stratification to adjust intensity of therapies.

Other strategies are to use behavioral interventions directed at improving compliance with follow-up to detect problems earlier and the use of real-time monitoring, such as with smart phones or fitness trackers. He said one limitation of this sort of research and implementing interventions to reduce late toxicities is that “you need time to document long-term outcomes.” So tracking newer therapies, such as proton beam radiation, small molecule drugs, and immunotherapy, is “going to take time, perhaps decades, before you understand their impact on patients.”

Risk of secondary neoplasms reduced

Risk-stratifying of disease “has allowed us to make attempts to minimize late effects by modifying therapy over time in certain subgroups of lower-risk patients,” said Dr. Lucie Turcotte of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

To study the effects of these changes, she determined the risk of certain subsequent malignant or benign neoplasms over three periods of therapeutic exposure among 23,603 5-year survivors of childhood cancers diagnosed at less than 21 years of age from 1970 to 1999, drawing from the cohort of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). The CCSS represents about 20% of childhood cancer survivors in the United States for the study period.

Over the decades of 1970-1979, 1980-1989, and 1990-1999, the use of any radiation went from 77% to 58% to 41%, respectively. Cranial radiation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) decreased from 85% to 19%, abdominal radiation for Wilms tumor from 78% to 43%, and chest radiotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma from 87% to 61%. The proportion of children receiving alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and epipodophyllotoxins went up, but the cumulative doses went down (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 3;374(9):833-42).

Dr. Nathan said today, almost no child gets cranial radiation for ALL. “So we’ve slowly learned that our treatments are toxic, and we’ve certainly done what we can to change them.”

But have these changes made a difference? Dr. Turcotte found that survivors remain at increased risk of a secondary neoplasm, but the risk was lower for children treated in later time periods.

Dr. Nathan pointed to Dr. Turcotte’s data showing that the incidence of subsequent malignant neoplasms decreased from 1970 to 1999 by 7% for each 5-year era (15-year risk: 2.3% to 1.6%; P = .001; number needed to treat, NNT = 143). Similarly, non-melanoma skin cancer 15-year risk decreased from 0.7% to 0.1% (P less than .001; NNT = 167). The NNT’s are “certainly important, but these are not major differences over time,” Dr. Nathan said. Knowing the impact of newer, targeted therapeutic approaches will take some time.

Predicting risk of premature menopause

Also using the CCSS data, Dr. Jennifer Levine of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, N.Y., studied the prevalence of and risk factors for nonsurgical premature menopause (NSPM), defined as cessation of menses prior to age 40 years, as well as the effect on reproductive outcomes for survivors of childhood cancers.

Dr. Nathan said when a child is first diagnosed with cancer, seldom does the issue of fertility come up early in the discussion, “but when you treat young adults who are survivors, the number one thing they talk about often is fertility. And so doing a better job in predicting who is at risk for infertility is clearly a priority for survivorship research.”

He said the development of the cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED) by D.M Green et al. (Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014 Jan;61(1):53-67) has been very helpful for quantifying alkylating agent exposure to make comparisons between studies. The goal is to develop a risk assessment tool to be able to tell patients and families their fertility risk based on demographics, therapy, and biomarkers.

Being able to evaluate risk is critically important because for girls, oocyte or ovarian harvesting or even transvaginal ultrasound is highly invasive, and these procedures should be recommended only if their risk for infertility is very high.

Dr. Levine studied 2,930 female cancer survivors diagnosed at a median age of 6 years between 1979 and 1986 and a median age at follow-up of 34 years, who were compared with 1,399 healthy siblings. Of the survivor cohort, 110 developed NSPM at a median age of 32 years, and the prevalence of NSPM at age 40 years for the entire cohort was 9.1%, giving a relative risk of NSPM of 10.5 compared with siblings, who had a 0.9% NSPM prevalence at age 40.

She found that exposure to alkylating agents and older age at diagnosis put childhood cancer survivors at increased risk of NSPM, which was associated with lower rates of pregnancy and live births after age 31 years. The greatest risk of NSPM occurred if the cyclophosphamide equivalent dose was greater than 6000 mg/m2 (odds ratio = 3.6 compared with no CED); if there had been any radiation to the ovaries (less than 5 Gy: OR = 4.0; 5 Gy or more: OR = 20.4); or if the age at diagnosis was greater than 14 years (OR = 2.3).

Women with NSPM, compared with survivors without NSPM, were less likely ever to be pregnant (OR = 0.41) or to have a live birth after age 30 (OR = 0.35). However, these outcomes were no different between the ages of 21 and 30. Dr. Levine said this information can assist clinicians in counseling their patients about the risk for early menopause and planning for alternative reproductive means, such as oocyte or embryo harvesting and preservation.

Neurocognitive functioning after treatment

Dr. Wei Liu of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., studied the neurocognitive function of long-term survivors of ALL.

Dr. Nathan called ALL “the paradigm for how we’ve sort of learned and adjusted how we treat patients based on late effects.” Early on, the disease was treated with craniospinal radiation and intrathecal chemotherapy, and while patients survived, it became obvious that they suffered neurocognitive and endocrine problems, growth abnormalities, and secondary malignancies. These findings forced a reevaluatuon of treatments, leading to elimination of spinal radiation, reduction of cranial radiation dose, intensification of systemic therapy, including methotrexate, and risk stratification allowing modification of therapies.

Survival was sustained, but long-term outcomes were still based on children treated with radiation. So long-term cognitive consequences in the more modern era of therapy were unknown. Only recently have adult cohorts become available who were treated in the chemotherapy-only era.

Dr. Liu studied 159 ALL survivors who had been treated with chemotherapy alone at a mean age of 9.2 years. The follow-up was at a median of 7.6 years off therapy at a mean age of 13.7 years. At the end of the chemotherapy protocol, patients completed tests of sustained attention, and parents rated survivors’ behavior on standard scales.

She found that for these childhood cancer survivors, sustained attention and behavior functioning at the end of chemotherapy predicted long-term attention and processing speed outcomes. Only exposure to chemotherapy, and not end-of-therapy function, predicted that survivors would have poor executive function of fluency and flexibility at long-term follow up.

Dr. Nathan praised the investigators for their foresight to collect data on the methotrexate area under the curve, number of triple intrathecal therapies (cytarabine, methotrexate, and hydrocortisone), and neurocognitive functioning at the end of chemotherapy. “What’s clear is that chemotherapy alone can lead to neurocognitive late effects,” he said. “But what’s also important is that not all late effects can be predicted by end of therapy assessments.” These late effects appear to evolve over time, so ongoing assessments are needed.

Dr. Turcotte, Dr. Liu, Dr. Levine, and Dr. Nathan each reported no financial disclosures.

Chicago – Survivors of childhood cancers face several later risks from treatment, and investigators presented studies evaluating risks in three specific areas – secondary neoplasms, premature menopause, and neurocognitive function – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Discussant Paul Nathan, M.D., of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, said “the whole purpose” of research in this area “is to start to understand the predictors and modifiers of late effects” and then to design risk assessment tools and interventions to reduce long-term toxicity. These interventions include modification of chemotherapy and radiation doses, protective strategies, and disease risk stratification to adjust intensity of therapies.

Other strategies are to use behavioral interventions directed at improving compliance with follow-up to detect problems earlier and the use of real-time monitoring, such as with smart phones or fitness trackers. He said one limitation of this sort of research and implementing interventions to reduce late toxicities is that “you need time to document long-term outcomes.” So tracking newer therapies, such as proton beam radiation, small molecule drugs, and immunotherapy, is “going to take time, perhaps decades, before you understand their impact on patients.”

Risk of secondary neoplasms reduced

Risk-stratifying of disease “has allowed us to make attempts to minimize late effects by modifying therapy over time in certain subgroups of lower-risk patients,” said Dr. Lucie Turcotte of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

To study the effects of these changes, she determined the risk of certain subsequent malignant or benign neoplasms over three periods of therapeutic exposure among 23,603 5-year survivors of childhood cancers diagnosed at less than 21 years of age from 1970 to 1999, drawing from the cohort of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). The CCSS represents about 20% of childhood cancer survivors in the United States for the study period.

Over the decades of 1970-1979, 1980-1989, and 1990-1999, the use of any radiation went from 77% to 58% to 41%, respectively. Cranial radiation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) decreased from 85% to 19%, abdominal radiation for Wilms tumor from 78% to 43%, and chest radiotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma from 87% to 61%. The proportion of children receiving alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and epipodophyllotoxins went up, but the cumulative doses went down (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 3;374(9):833-42).

Dr. Nathan said today, almost no child gets cranial radiation for ALL. “So we’ve slowly learned that our treatments are toxic, and we’ve certainly done what we can to change them.”

But have these changes made a difference? Dr. Turcotte found that survivors remain at increased risk of a secondary neoplasm, but the risk was lower for children treated in later time periods.

Dr. Nathan pointed to Dr. Turcotte’s data showing that the incidence of subsequent malignant neoplasms decreased from 1970 to 1999 by 7% for each 5-year era (15-year risk: 2.3% to 1.6%; P = .001; number needed to treat, NNT = 143). Similarly, non-melanoma skin cancer 15-year risk decreased from 0.7% to 0.1% (P less than .001; NNT = 167). The NNT’s are “certainly important, but these are not major differences over time,” Dr. Nathan said. Knowing the impact of newer, targeted therapeutic approaches will take some time.

Predicting risk of premature menopause

Also using the CCSS data, Dr. Jennifer Levine of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, N.Y., studied the prevalence of and risk factors for nonsurgical premature menopause (NSPM), defined as cessation of menses prior to age 40 years, as well as the effect on reproductive outcomes for survivors of childhood cancers.

Dr. Nathan said when a child is first diagnosed with cancer, seldom does the issue of fertility come up early in the discussion, “but when you treat young adults who are survivors, the number one thing they talk about often is fertility. And so doing a better job in predicting who is at risk for infertility is clearly a priority for survivorship research.”

He said the development of the cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED) by D.M Green et al. (Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014 Jan;61(1):53-67) has been very helpful for quantifying alkylating agent exposure to make comparisons between studies. The goal is to develop a risk assessment tool to be able to tell patients and families their fertility risk based on demographics, therapy, and biomarkers.

Being able to evaluate risk is critically important because for girls, oocyte or ovarian harvesting or even transvaginal ultrasound is highly invasive, and these procedures should be recommended only if their risk for infertility is very high.

Dr. Levine studied 2,930 female cancer survivors diagnosed at a median age of 6 years between 1979 and 1986 and a median age at follow-up of 34 years, who were compared with 1,399 healthy siblings. Of the survivor cohort, 110 developed NSPM at a median age of 32 years, and the prevalence of NSPM at age 40 years for the entire cohort was 9.1%, giving a relative risk of NSPM of 10.5 compared with siblings, who had a 0.9% NSPM prevalence at age 40.

She found that exposure to alkylating agents and older age at diagnosis put childhood cancer survivors at increased risk of NSPM, which was associated with lower rates of pregnancy and live births after age 31 years. The greatest risk of NSPM occurred if the cyclophosphamide equivalent dose was greater than 6000 mg/m2 (odds ratio = 3.6 compared with no CED); if there had been any radiation to the ovaries (less than 5 Gy: OR = 4.0; 5 Gy or more: OR = 20.4); or if the age at diagnosis was greater than 14 years (OR = 2.3).

Women with NSPM, compared with survivors without NSPM, were less likely ever to be pregnant (OR = 0.41) or to have a live birth after age 30 (OR = 0.35). However, these outcomes were no different between the ages of 21 and 30. Dr. Levine said this information can assist clinicians in counseling their patients about the risk for early menopause and planning for alternative reproductive means, such as oocyte or embryo harvesting and preservation.

Neurocognitive functioning after treatment

Dr. Wei Liu of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., studied the neurocognitive function of long-term survivors of ALL.

Dr. Nathan called ALL “the paradigm for how we’ve sort of learned and adjusted how we treat patients based on late effects.” Early on, the disease was treated with craniospinal radiation and intrathecal chemotherapy, and while patients survived, it became obvious that they suffered neurocognitive and endocrine problems, growth abnormalities, and secondary malignancies. These findings forced a reevaluatuon of treatments, leading to elimination of spinal radiation, reduction of cranial radiation dose, intensification of systemic therapy, including methotrexate, and risk stratification allowing modification of therapies.

Survival was sustained, but long-term outcomes were still based on children treated with radiation. So long-term cognitive consequences in the more modern era of therapy were unknown. Only recently have adult cohorts become available who were treated in the chemotherapy-only era.

Dr. Liu studied 159 ALL survivors who had been treated with chemotherapy alone at a mean age of 9.2 years. The follow-up was at a median of 7.6 years off therapy at a mean age of 13.7 years. At the end of the chemotherapy protocol, patients completed tests of sustained attention, and parents rated survivors’ behavior on standard scales.

She found that for these childhood cancer survivors, sustained attention and behavior functioning at the end of chemotherapy predicted long-term attention and processing speed outcomes. Only exposure to chemotherapy, and not end-of-therapy function, predicted that survivors would have poor executive function of fluency and flexibility at long-term follow up.

Dr. Nathan praised the investigators for their foresight to collect data on the methotrexate area under the curve, number of triple intrathecal therapies (cytarabine, methotrexate, and hydrocortisone), and neurocognitive functioning at the end of chemotherapy. “What’s clear is that chemotherapy alone can lead to neurocognitive late effects,” he said. “But what’s also important is that not all late effects can be predicted by end of therapy assessments.” These late effects appear to evolve over time, so ongoing assessments are needed.

Dr. Turcotte, Dr. Liu, Dr. Levine, and Dr. Nathan each reported no financial disclosures.

Chicago – Survivors of childhood cancers face several later risks from treatment, and investigators presented studies evaluating risks in three specific areas – secondary neoplasms, premature menopause, and neurocognitive function – at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Discussant Paul Nathan, M.D., of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, said “the whole purpose” of research in this area “is to start to understand the predictors and modifiers of late effects” and then to design risk assessment tools and interventions to reduce long-term toxicity. These interventions include modification of chemotherapy and radiation doses, protective strategies, and disease risk stratification to adjust intensity of therapies.

Other strategies are to use behavioral interventions directed at improving compliance with follow-up to detect problems earlier and the use of real-time monitoring, such as with smart phones or fitness trackers. He said one limitation of this sort of research and implementing interventions to reduce late toxicities is that “you need time to document long-term outcomes.” So tracking newer therapies, such as proton beam radiation, small molecule drugs, and immunotherapy, is “going to take time, perhaps decades, before you understand their impact on patients.”

Risk of secondary neoplasms reduced

Risk-stratifying of disease “has allowed us to make attempts to minimize late effects by modifying therapy over time in certain subgroups of lower-risk patients,” said Dr. Lucie Turcotte of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

To study the effects of these changes, she determined the risk of certain subsequent malignant or benign neoplasms over three periods of therapeutic exposure among 23,603 5-year survivors of childhood cancers diagnosed at less than 21 years of age from 1970 to 1999, drawing from the cohort of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). The CCSS represents about 20% of childhood cancer survivors in the United States for the study period.

Over the decades of 1970-1979, 1980-1989, and 1990-1999, the use of any radiation went from 77% to 58% to 41%, respectively. Cranial radiation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) decreased from 85% to 19%, abdominal radiation for Wilms tumor from 78% to 43%, and chest radiotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma from 87% to 61%. The proportion of children receiving alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and epipodophyllotoxins went up, but the cumulative doses went down (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 3;374(9):833-42).

Dr. Nathan said today, almost no child gets cranial radiation for ALL. “So we’ve slowly learned that our treatments are toxic, and we’ve certainly done what we can to change them.”

But have these changes made a difference? Dr. Turcotte found that survivors remain at increased risk of a secondary neoplasm, but the risk was lower for children treated in later time periods.

Dr. Nathan pointed to Dr. Turcotte’s data showing that the incidence of subsequent malignant neoplasms decreased from 1970 to 1999 by 7% for each 5-year era (15-year risk: 2.3% to 1.6%; P = .001; number needed to treat, NNT = 143). Similarly, non-melanoma skin cancer 15-year risk decreased from 0.7% to 0.1% (P less than .001; NNT = 167). The NNT’s are “certainly important, but these are not major differences over time,” Dr. Nathan said. Knowing the impact of newer, targeted therapeutic approaches will take some time.

Predicting risk of premature menopause

Also using the CCSS data, Dr. Jennifer Levine of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, N.Y., studied the prevalence of and risk factors for nonsurgical premature menopause (NSPM), defined as cessation of menses prior to age 40 years, as well as the effect on reproductive outcomes for survivors of childhood cancers.

Dr. Nathan said when a child is first diagnosed with cancer, seldom does the issue of fertility come up early in the discussion, “but when you treat young adults who are survivors, the number one thing they talk about often is fertility. And so doing a better job in predicting who is at risk for infertility is clearly a priority for survivorship research.”

He said the development of the cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED) by D.M Green et al. (Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014 Jan;61(1):53-67) has been very helpful for quantifying alkylating agent exposure to make comparisons between studies. The goal is to develop a risk assessment tool to be able to tell patients and families their fertility risk based on demographics, therapy, and biomarkers.

Being able to evaluate risk is critically important because for girls, oocyte or ovarian harvesting or even transvaginal ultrasound is highly invasive, and these procedures should be recommended only if their risk for infertility is very high.

Dr. Levine studied 2,930 female cancer survivors diagnosed at a median age of 6 years between 1979 and 1986 and a median age at follow-up of 34 years, who were compared with 1,399 healthy siblings. Of the survivor cohort, 110 developed NSPM at a median age of 32 years, and the prevalence of NSPM at age 40 years for the entire cohort was 9.1%, giving a relative risk of NSPM of 10.5 compared with siblings, who had a 0.9% NSPM prevalence at age 40.

She found that exposure to alkylating agents and older age at diagnosis put childhood cancer survivors at increased risk of NSPM, which was associated with lower rates of pregnancy and live births after age 31 years. The greatest risk of NSPM occurred if the cyclophosphamide equivalent dose was greater than 6000 mg/m2 (odds ratio = 3.6 compared with no CED); if there had been any radiation to the ovaries (less than 5 Gy: OR = 4.0; 5 Gy or more: OR = 20.4); or if the age at diagnosis was greater than 14 years (OR = 2.3).

Women with NSPM, compared with survivors without NSPM, were less likely ever to be pregnant (OR = 0.41) or to have a live birth after age 30 (OR = 0.35). However, these outcomes were no different between the ages of 21 and 30. Dr. Levine said this information can assist clinicians in counseling their patients about the risk for early menopause and planning for alternative reproductive means, such as oocyte or embryo harvesting and preservation.

Neurocognitive functioning after treatment

Dr. Wei Liu of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., studied the neurocognitive function of long-term survivors of ALL.

Dr. Nathan called ALL “the paradigm for how we’ve sort of learned and adjusted how we treat patients based on late effects.” Early on, the disease was treated with craniospinal radiation and intrathecal chemotherapy, and while patients survived, it became obvious that they suffered neurocognitive and endocrine problems, growth abnormalities, and secondary malignancies. These findings forced a reevaluatuon of treatments, leading to elimination of spinal radiation, reduction of cranial radiation dose, intensification of systemic therapy, including methotrexate, and risk stratification allowing modification of therapies.

Survival was sustained, but long-term outcomes were still based on children treated with radiation. So long-term cognitive consequences in the more modern era of therapy were unknown. Only recently have adult cohorts become available who were treated in the chemotherapy-only era.

Dr. Liu studied 159 ALL survivors who had been treated with chemotherapy alone at a mean age of 9.2 years. The follow-up was at a median of 7.6 years off therapy at a mean age of 13.7 years. At the end of the chemotherapy protocol, patients completed tests of sustained attention, and parents rated survivors’ behavior on standard scales.

She found that for these childhood cancer survivors, sustained attention and behavior functioning at the end of chemotherapy predicted long-term attention and processing speed outcomes. Only exposure to chemotherapy, and not end-of-therapy function, predicted that survivors would have poor executive function of fluency and flexibility at long-term follow up.

Dr. Nathan praised the investigators for their foresight to collect data on the methotrexate area under the curve, number of triple intrathecal therapies (cytarabine, methotrexate, and hydrocortisone), and neurocognitive functioning at the end of chemotherapy. “What’s clear is that chemotherapy alone can lead to neurocognitive late effects,” he said. “But what’s also important is that not all late effects can be predicted by end of therapy assessments.” These late effects appear to evolve over time, so ongoing assessments are needed.

Dr. Turcotte, Dr. Liu, Dr. Levine, and Dr. Nathan each reported no financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Despite improvements, survivors of childhood cancers still face long-term risks in terms of secondary neoplasms, nonsurgical premature menopause (NSPM), and neurocognitive function.

Major finding: Of the survivor cohort, 110 developed NSPM at a median age of 32 years, so the prevalence of NSPM at age 40 years for the entire cohort was 9.1%, while siblings had a 0.9% NSPM prevalence at age 40.

Data source: Retrospective study of 2,930 childhood cancer survivors diagnosed at age 6 years and follow-up at median age 34 years and 1,390 healthy siblings. Also cross-sectional prospective study for neurocognitive assessment of 159 ALL survivors, and risks of secondary neoplasms in 23,603 5-year survivors of childhood cancers .

Disclosures: Dr. Turcotte, Dr. Liu, Dr. Levine, and Dr. Nathan each reported no financial disclosures.

One-time AMH level predicts rapid perimenopausal bone loss

BOSTON – Anti-Müllerian hormone levels strongly predict the rate of perimenopausal loss of bone mineral density and might help identify women who need early intervention to prevent future osteoporotic fractures, according to data from a review of 474 perimenopausal women that was presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The team matched anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and bone mineral density (BMD) measurements taken 2-4 years before the final menstrual period to BMD measurements taken 3 years later. The women were part of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), an ongoing multicenter study of women during their middle years.

When perimenopausal AMH “goes below 250 pg/mL, you are beginning to lose bone, and, when it goes below 200 pg/mL, you are losing bone fast, so that’s when you might want to intervene.” The finding “opens up the possibility of identifying women who are going to lose the most bone mass during the transition and targeting them before they have lost a substantial amount,” said lead investigator Dr. Arun Karlamangla of the department of geriatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

BMD loss is normal during menopause but rates of decline vary among women. AMH is a product of ovarian granulosa cells commonly used in fertility clinics to gauge ovarian reserve, but AMH levels also decline during menopause, and in a fairly stable fashion, he explained.

The women in SWAN were 42-52 years old at baseline with an intact uterus, at least one ovary, and no use of exogenous hormones. Blood was drawn during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

The median rate of BMD decline was 1.26% per year in the lumbar spine and 1.03% per year in the femoral neck. The median AMH was 49 pg/mL but varied widely.

Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, race, and study site, the team found that for each 75% (or fourfold) decrement in AMH level, there was a 0.15% per year faster decline in spine BMD and 0.13% per year faster decline in femoral neck BMD. Each fourfold decrement was also associated with an 18% increase in the odds of faster than median decline in spine BMD and 17% increase in the odds of faster than median decline in femoral neck BMD. The fast losers lost more than 2% of their BMD per year in both the lumbar spine and femoral neck.

The results were the same after adjustment for follicle-stimulating hormone and estrogen levels, “so AMH provides information that cannot be obtained from estrogen and FSH,” Dr. Karlamangla said.

He cautioned that the technique needs further development and validation before it’s ready for the clinic. The team used the PicoAMH test from Ansh Labs in Webster, Tex.

The investigators had no disclosures. Ansh provided the assays for free. SWAN is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

The current recommendation is to start bone mineral density screening in women at age 65 years. All of us who see patients in the menopause years worry that we are missing someone with faster than normal bone loss. Fast losers are critical to identify because if we wait until they are 65 years old, it’s too late. A clinical test such as this to identify fast losers for earlier BMD measurement would be a tremendous benefit.

Dr. Cynthia Stuenkel is a clinical professor of endocrinology at the University of California, San Diego. She moderated the presentation and was not involved in the research.

The current recommendation is to start bone mineral density screening in women at age 65 years. All of us who see patients in the menopause years worry that we are missing someone with faster than normal bone loss. Fast losers are critical to identify because if we wait until they are 65 years old, it’s too late. A clinical test such as this to identify fast losers for earlier BMD measurement would be a tremendous benefit.

Dr. Cynthia Stuenkel is a clinical professor of endocrinology at the University of California, San Diego. She moderated the presentation and was not involved in the research.

The current recommendation is to start bone mineral density screening in women at age 65 years. All of us who see patients in the menopause years worry that we are missing someone with faster than normal bone loss. Fast losers are critical to identify because if we wait until they are 65 years old, it’s too late. A clinical test such as this to identify fast losers for earlier BMD measurement would be a tremendous benefit.

Dr. Cynthia Stuenkel is a clinical professor of endocrinology at the University of California, San Diego. She moderated the presentation and was not involved in the research.

BOSTON – Anti-Müllerian hormone levels strongly predict the rate of perimenopausal loss of bone mineral density and might help identify women who need early intervention to prevent future osteoporotic fractures, according to data from a review of 474 perimenopausal women that was presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The team matched anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and bone mineral density (BMD) measurements taken 2-4 years before the final menstrual period to BMD measurements taken 3 years later. The women were part of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), an ongoing multicenter study of women during their middle years.

When perimenopausal AMH “goes below 250 pg/mL, you are beginning to lose bone, and, when it goes below 200 pg/mL, you are losing bone fast, so that’s when you might want to intervene.” The finding “opens up the possibility of identifying women who are going to lose the most bone mass during the transition and targeting them before they have lost a substantial amount,” said lead investigator Dr. Arun Karlamangla of the department of geriatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

BMD loss is normal during menopause but rates of decline vary among women. AMH is a product of ovarian granulosa cells commonly used in fertility clinics to gauge ovarian reserve, but AMH levels also decline during menopause, and in a fairly stable fashion, he explained.

The women in SWAN were 42-52 years old at baseline with an intact uterus, at least one ovary, and no use of exogenous hormones. Blood was drawn during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

The median rate of BMD decline was 1.26% per year in the lumbar spine and 1.03% per year in the femoral neck. The median AMH was 49 pg/mL but varied widely.

Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, race, and study site, the team found that for each 75% (or fourfold) decrement in AMH level, there was a 0.15% per year faster decline in spine BMD and 0.13% per year faster decline in femoral neck BMD. Each fourfold decrement was also associated with an 18% increase in the odds of faster than median decline in spine BMD and 17% increase in the odds of faster than median decline in femoral neck BMD. The fast losers lost more than 2% of their BMD per year in both the lumbar spine and femoral neck.

The results were the same after adjustment for follicle-stimulating hormone and estrogen levels, “so AMH provides information that cannot be obtained from estrogen and FSH,” Dr. Karlamangla said.

He cautioned that the technique needs further development and validation before it’s ready for the clinic. The team used the PicoAMH test from Ansh Labs in Webster, Tex.

The investigators had no disclosures. Ansh provided the assays for free. SWAN is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

BOSTON – Anti-Müllerian hormone levels strongly predict the rate of perimenopausal loss of bone mineral density and might help identify women who need early intervention to prevent future osteoporotic fractures, according to data from a review of 474 perimenopausal women that was presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The team matched anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and bone mineral density (BMD) measurements taken 2-4 years before the final menstrual period to BMD measurements taken 3 years later. The women were part of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), an ongoing multicenter study of women during their middle years.

When perimenopausal AMH “goes below 250 pg/mL, you are beginning to lose bone, and, when it goes below 200 pg/mL, you are losing bone fast, so that’s when you might want to intervene.” The finding “opens up the possibility of identifying women who are going to lose the most bone mass during the transition and targeting them before they have lost a substantial amount,” said lead investigator Dr. Arun Karlamangla of the department of geriatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

BMD loss is normal during menopause but rates of decline vary among women. AMH is a product of ovarian granulosa cells commonly used in fertility clinics to gauge ovarian reserve, but AMH levels also decline during menopause, and in a fairly stable fashion, he explained.

The women in SWAN were 42-52 years old at baseline with an intact uterus, at least one ovary, and no use of exogenous hormones. Blood was drawn during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

The median rate of BMD decline was 1.26% per year in the lumbar spine and 1.03% per year in the femoral neck. The median AMH was 49 pg/mL but varied widely.

Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, race, and study site, the team found that for each 75% (or fourfold) decrement in AMH level, there was a 0.15% per year faster decline in spine BMD and 0.13% per year faster decline in femoral neck BMD. Each fourfold decrement was also associated with an 18% increase in the odds of faster than median decline in spine BMD and 17% increase in the odds of faster than median decline in femoral neck BMD. The fast losers lost more than 2% of their BMD per year in both the lumbar spine and femoral neck.

The results were the same after adjustment for follicle-stimulating hormone and estrogen levels, “so AMH provides information that cannot be obtained from estrogen and FSH,” Dr. Karlamangla said.

He cautioned that the technique needs further development and validation before it’s ready for the clinic. The team used the PicoAMH test from Ansh Labs in Webster, Tex.

The investigators had no disclosures. Ansh provided the assays for free. SWAN is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

AT ENDO 2016

Key clinical point: Anti-Müllerian hormone levels strongly predict the rate of perimenopausal bone mineral density loss and might help identify women who need early intervention to prevent future osteoporotic fractures, according to a review of 474 perimenopausal women that was presented at the Endocrine Society annual meeting.

Major finding: Adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, race, and study site, the team found that for each 75% (or fourfold) decrement in AMH level, there was a 0.15% per year faster decline in lumbar spine BMD and 0.13% per year faster decline in femoral neck BMD.

Data source: Review of 474 perimenopausal women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation.

Disclosures: The investigators had no disclosures. Ansh Labs provided the assays for free. SWAN is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Early estrogen likely prevents bone fractures in Turner syndrome

BOSTON – The longer that estrogen therapy is delayed in girls with Turner syndrome, the lower their bone density will be in subsequent years, based on results of a retrospective, cross-sectional study from Monash University, in Melbourne, Australia.

For every year after age 11 that Turner patients went without estrogen – generally due to delayed initiation, but sometimes noncompliance – there was a significant reduction in bone mineral density in both the lumbar spine (Beta -0.582, P less than 0.001) and femoral neck (Beta -0.383, P = 0.008).

Estrogen deficiency and subsequent suboptimal bone mass accrual are known to contribute to the increased risk of osteoporosis in women with Turner syndrome, and about a doubling of the risk of fragility fractures, mostly of the forearm. About a third of the 76 women in the study had at least one fracture, explained investigator Dr. Amanda Vincent, head of the Midlife Health and Menopause Program at Monash.

“Avoiding estrogen deficiency is important to optimize bone health in Turner syndrome.” It “depends on early diagnosis, age-appropriate pubertal induction, and optimization of compliance,” Dr. Vincent said at the Endocrine Society annual meeting.

The median age of Turner syndrome diagnosis was 11 years, but estrogen treatments didn’t begin until a median age of 15. The women in the study were a median of about 30 years old, which means that they were adolescents at the time when estrogen treatment was often delayed in the mistaken belief that growth hormone therapy would be more effective before puberty was induced.

It’s now known that estrogen replacement works synergistically with, and even potentiates, the effects of growth hormone. Current guidelines recommend pubertal induction by age 13 (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Jan;92(1):10-25).

The women had at least one dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan at Monash since 1998. Z-scores below - 2, indicating low bone density, were found in the lumbar spines of about a quarter the subjects, and in the femoral necks of about 8%. Primary amenorrhea and premature menopause, followed by vitamin D deficiency, were the most common risk factors for low bone mass. Almost 40% of the women reported non-continuous use of estrogen. About half had undergone growth hormone therapy.

At a median height of 149 cm, the subjects were about 15 cm shorter than age-matched, healthy controls, and also had a slightly higher median body mass index of 25.6 kg/m2. Lumbar spine bone area, bone mineral content, areal bone mineral density, and bone mineral apparent density were significantly lower in Turner syndrome patients. In the femoral neck, areal bone mineral density was significantly lower.

There was no relationship between bone markers and growth hormone use or Turner syndrome karyotype; the predominant karyotype was 45XO, but the study also included mosaic karyotypes.

The investigators had no disclosures.

These are important observations. The bottom line is early recognition and early referral. It’s clear from this study and others that earlier institution of estrogen is beneficial for height, bone density, and fracture risk throughout life. It’s not just an issue of a 20 year old with low bone density; that 20 year old later becomes a 60 year old with low bone density.

|

Dr. Michael Levine |

[However,] we still have a problem with delayed recognition and referral of young girls with Turner syndrome. Most girls with Turner syndrome have some typical phenotypic features, but some do not, so the diagnosis is often made too late. [To get around that problem,] we recommend that all children below the 5th percentile for height – or who flatten out too early on growth curves – be referred to rule out Turner syndrome and other problems.

Dr. Michael Levine is chief of the Division of Endocrinology at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He made his comments after the study presentation, and was not involved in the work.

These are important observations. The bottom line is early recognition and early referral. It’s clear from this study and others that earlier institution of estrogen is beneficial for height, bone density, and fracture risk throughout life. It’s not just an issue of a 20 year old with low bone density; that 20 year old later becomes a 60 year old with low bone density.

|

Dr. Michael Levine |

[However,] we still have a problem with delayed recognition and referral of young girls with Turner syndrome. Most girls with Turner syndrome have some typical phenotypic features, but some do not, so the diagnosis is often made too late. [To get around that problem,] we recommend that all children below the 5th percentile for height – or who flatten out too early on growth curves – be referred to rule out Turner syndrome and other problems.

Dr. Michael Levine is chief of the Division of Endocrinology at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He made his comments after the study presentation, and was not involved in the work.

These are important observations. The bottom line is early recognition and early referral. It’s clear from this study and others that earlier institution of estrogen is beneficial for height, bone density, and fracture risk throughout life. It’s not just an issue of a 20 year old with low bone density; that 20 year old later becomes a 60 year old with low bone density.

|

Dr. Michael Levine |

[However,] we still have a problem with delayed recognition and referral of young girls with Turner syndrome. Most girls with Turner syndrome have some typical phenotypic features, but some do not, so the diagnosis is often made too late. [To get around that problem,] we recommend that all children below the 5th percentile for height – or who flatten out too early on growth curves – be referred to rule out Turner syndrome and other problems.

Dr. Michael Levine is chief of the Division of Endocrinology at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He made his comments after the study presentation, and was not involved in the work.

BOSTON – The longer that estrogen therapy is delayed in girls with Turner syndrome, the lower their bone density will be in subsequent years, based on results of a retrospective, cross-sectional study from Monash University, in Melbourne, Australia.

For every year after age 11 that Turner patients went without estrogen – generally due to delayed initiation, but sometimes noncompliance – there was a significant reduction in bone mineral density in both the lumbar spine (Beta -0.582, P less than 0.001) and femoral neck (Beta -0.383, P = 0.008).

Estrogen deficiency and subsequent suboptimal bone mass accrual are known to contribute to the increased risk of osteoporosis in women with Turner syndrome, and about a doubling of the risk of fragility fractures, mostly of the forearm. About a third of the 76 women in the study had at least one fracture, explained investigator Dr. Amanda Vincent, head of the Midlife Health and Menopause Program at Monash.

“Avoiding estrogen deficiency is important to optimize bone health in Turner syndrome.” It “depends on early diagnosis, age-appropriate pubertal induction, and optimization of compliance,” Dr. Vincent said at the Endocrine Society annual meeting.

The median age of Turner syndrome diagnosis was 11 years, but estrogen treatments didn’t begin until a median age of 15. The women in the study were a median of about 30 years old, which means that they were adolescents at the time when estrogen treatment was often delayed in the mistaken belief that growth hormone therapy would be more effective before puberty was induced.

It’s now known that estrogen replacement works synergistically with, and even potentiates, the effects of growth hormone. Current guidelines recommend pubertal induction by age 13 (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Jan;92(1):10-25).

The women had at least one dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan at Monash since 1998. Z-scores below - 2, indicating low bone density, were found in the lumbar spines of about a quarter the subjects, and in the femoral necks of about 8%. Primary amenorrhea and premature menopause, followed by vitamin D deficiency, were the most common risk factors for low bone mass. Almost 40% of the women reported non-continuous use of estrogen. About half had undergone growth hormone therapy.

At a median height of 149 cm, the subjects were about 15 cm shorter than age-matched, healthy controls, and also had a slightly higher median body mass index of 25.6 kg/m2. Lumbar spine bone area, bone mineral content, areal bone mineral density, and bone mineral apparent density were significantly lower in Turner syndrome patients. In the femoral neck, areal bone mineral density was significantly lower.

There was no relationship between bone markers and growth hormone use or Turner syndrome karyotype; the predominant karyotype was 45XO, but the study also included mosaic karyotypes.

The investigators had no disclosures.

BOSTON – The longer that estrogen therapy is delayed in girls with Turner syndrome, the lower their bone density will be in subsequent years, based on results of a retrospective, cross-sectional study from Monash University, in Melbourne, Australia.

For every year after age 11 that Turner patients went without estrogen – generally due to delayed initiation, but sometimes noncompliance – there was a significant reduction in bone mineral density in both the lumbar spine (Beta -0.582, P less than 0.001) and femoral neck (Beta -0.383, P = 0.008).

Estrogen deficiency and subsequent suboptimal bone mass accrual are known to contribute to the increased risk of osteoporosis in women with Turner syndrome, and about a doubling of the risk of fragility fractures, mostly of the forearm. About a third of the 76 women in the study had at least one fracture, explained investigator Dr. Amanda Vincent, head of the Midlife Health and Menopause Program at Monash.

“Avoiding estrogen deficiency is important to optimize bone health in Turner syndrome.” It “depends on early diagnosis, age-appropriate pubertal induction, and optimization of compliance,” Dr. Vincent said at the Endocrine Society annual meeting.

The median age of Turner syndrome diagnosis was 11 years, but estrogen treatments didn’t begin until a median age of 15. The women in the study were a median of about 30 years old, which means that they were adolescents at the time when estrogen treatment was often delayed in the mistaken belief that growth hormone therapy would be more effective before puberty was induced.

It’s now known that estrogen replacement works synergistically with, and even potentiates, the effects of growth hormone. Current guidelines recommend pubertal induction by age 13 (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Jan;92(1):10-25).

The women had at least one dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan at Monash since 1998. Z-scores below - 2, indicating low bone density, were found in the lumbar spines of about a quarter the subjects, and in the femoral necks of about 8%. Primary amenorrhea and premature menopause, followed by vitamin D deficiency, were the most common risk factors for low bone mass. Almost 40% of the women reported non-continuous use of estrogen. About half had undergone growth hormone therapy.

At a median height of 149 cm, the subjects were about 15 cm shorter than age-matched, healthy controls, and also had a slightly higher median body mass index of 25.6 kg/m2. Lumbar spine bone area, bone mineral content, areal bone mineral density, and bone mineral apparent density were significantly lower in Turner syndrome patients. In the femoral neck, areal bone mineral density was significantly lower.

There was no relationship between bone markers and growth hormone use or Turner syndrome karyotype; the predominant karyotype was 45XO, but the study also included mosaic karyotypes.

The investigators had no disclosures.

AT ENDO 2016

Key clinical point: Induce puberty by age 13 in Turner syndrome.

Major finding: For every year after age 11 that Turner patients went without estrogen – generally due to delayed initiation, but sometimes noncompliance – there was a significant reduction in bone mineral density in both the lubar spine (Beta -0.582, P less than 0.001) and femoral neck (Beta -0.383, P = 0.008).

Data source: Retrospective, cross-section study of 76 Turner syndrome patients

Disclosures: The investigators had no disclosures.

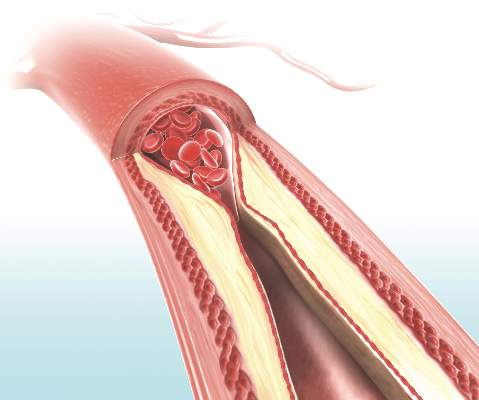

Only ‘early’ estradiol limits atherosclerosis progression

Hormone therapy – estradiol with or without progesterone – only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause onset, according to a report published online March 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The “hormone-timing hypothesis” posits that hormone therapy’s beneficial effects on atherosclerosis depend on the timing of initiating that therapy relative to menopause. To test this hypothesis, researchers began the ELITE study (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) in 2002, using serial noninvasive measurements of carotid-artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a marker of atherosclerosis progression.

Several other studies since 2002 have reported that the timing hypothesis appears to be valid, wrote Dr. Howard N. Hodis of the Atherosclerosis Research Unit, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and his associates.

Their single-center trial involved 643 healthy postmenopausal women who had no diabetes and no evidence of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and who were randomly assigned to receive either daily oral estradiol or a matching placebo for 5 years. Women who had an intact uterus and took active estradiol also received a 4% micronized progesterone vaginal gel, while those who had an intact uterus and took placebo also received a matching placebo gel.

The participants were stratified according to the number of years they were past menopause: less than 6 years (271 women in the “early” group) or more than 10 years (372 in the “late” group).

A total of 137 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to active estradiol, while 134 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to placebo. As expected, serum estradiol levels were at least 3 times higher among women assigned to active treatment, compared with those assigned to placebo.

The primary outcome – the effect of hormone therapy on CIMT progression – differed by timing of the initiation of treatment. In the “early” group, the mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo.

In contrast, in the “late” group, the rates of CIMT progression were not significantly different between estradiol and placebo, the investigators wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1221-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241).

This beneficial effect remained significant in a sensitivity analysis restricted only to study participants who showed at least 80% adherence to their assigned treatment. The benefit also remained significant in a post-hoc analysis comparing women who took estradiol alone against those who took estradiol plus progestogen, as well as in a separate analysis comparing women who used lipid-lowering and/or hypertensive medications against those who did not.

The findings add further evidence in favor of the hormone timing hypothesis. The effect of estradiol therapy on CIMT progression was significantly modified by time since menopause (P = .007 for the interaction), the researchers wrote.

Cardiac computer tomography (CT) was used as a different method of assessing coronary atherosclerosis in a subgroup of 167 women in the early group (88 receiving estradiol and 79 receiving placebo) and 214 in the late group (101 receiving estradiol and 113 receiving placebo). The timing of estradiol treatment did not affect coronary artery calcium and other cardiac CT measures. This is consistent with previous reports that hormone therapy has no significant effect on established lesions in the coronary arteries, the researchers wrote.

The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.

Despite the favorable effect of estrogen on atherosclerosis in early postmenopausal women in the ELITE trial, the relevance of these results to clinical coronary heart disease events remains questionable. The trial assessed only surrogate measures of coronary heart disease and was not designed or powered to assess clinical events. The occurrence of myocardial infarction and stroke involves not only atherosclerotic plaque formation but also plaque rupture and thrombosis. Any changes in these latter two phenomena would not be captured by the CIMT measurements in ELITE — a point of particular interest, given that postmenopausal hormone therapy may promote thrombosis and inflammation. A final caution is that the available clinical data in support of the timing hypothesis are suggestive but inconsistent.

Guidelines from various professional organizations currently caution against using postmenopausal hormone therapy for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular events. Although the ELITE trial results support the hypothesis that postmenopausal hormone therapy may have more favorable effects on atherosclerosis when initiated soon after menopause, extrapolation of these results to clinical events would be premature, and the present guidance remains prudent.

Dr. John F. Keaney, Jr., is at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester and is an associate editor at the New England Journal of Medicine, and Dr. Caren G. Solomon is a deputy editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1602846).

Despite the favorable effect of estrogen on atherosclerosis in early postmenopausal women in the ELITE trial, the relevance of these results to clinical coronary heart disease events remains questionable. The trial assessed only surrogate measures of coronary heart disease and was not designed or powered to assess clinical events. The occurrence of myocardial infarction and stroke involves not only atherosclerotic plaque formation but also plaque rupture and thrombosis. Any changes in these latter two phenomena would not be captured by the CIMT measurements in ELITE — a point of particular interest, given that postmenopausal hormone therapy may promote thrombosis and inflammation. A final caution is that the available clinical data in support of the timing hypothesis are suggestive but inconsistent.

Guidelines from various professional organizations currently caution against using postmenopausal hormone therapy for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular events. Although the ELITE trial results support the hypothesis that postmenopausal hormone therapy may have more favorable effects on atherosclerosis when initiated soon after menopause, extrapolation of these results to clinical events would be premature, and the present guidance remains prudent.

Dr. John F. Keaney, Jr., is at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester and is an associate editor at the New England Journal of Medicine, and Dr. Caren G. Solomon is a deputy editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1602846).

Despite the favorable effect of estrogen on atherosclerosis in early postmenopausal women in the ELITE trial, the relevance of these results to clinical coronary heart disease events remains questionable. The trial assessed only surrogate measures of coronary heart disease and was not designed or powered to assess clinical events. The occurrence of myocardial infarction and stroke involves not only atherosclerotic plaque formation but also plaque rupture and thrombosis. Any changes in these latter two phenomena would not be captured by the CIMT measurements in ELITE — a point of particular interest, given that postmenopausal hormone therapy may promote thrombosis and inflammation. A final caution is that the available clinical data in support of the timing hypothesis are suggestive but inconsistent.

Guidelines from various professional organizations currently caution against using postmenopausal hormone therapy for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular events. Although the ELITE trial results support the hypothesis that postmenopausal hormone therapy may have more favorable effects on atherosclerosis when initiated soon after menopause, extrapolation of these results to clinical events would be premature, and the present guidance remains prudent.

Dr. John F. Keaney, Jr., is at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester and is an associate editor at the New England Journal of Medicine, and Dr. Caren G. Solomon is a deputy editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1602846).

Hormone therapy – estradiol with or without progesterone – only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause onset, according to a report published online March 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The “hormone-timing hypothesis” posits that hormone therapy’s beneficial effects on atherosclerosis depend on the timing of initiating that therapy relative to menopause. To test this hypothesis, researchers began the ELITE study (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) in 2002, using serial noninvasive measurements of carotid-artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a marker of atherosclerosis progression.

Several other studies since 2002 have reported that the timing hypothesis appears to be valid, wrote Dr. Howard N. Hodis of the Atherosclerosis Research Unit, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and his associates.

Their single-center trial involved 643 healthy postmenopausal women who had no diabetes and no evidence of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and who were randomly assigned to receive either daily oral estradiol or a matching placebo for 5 years. Women who had an intact uterus and took active estradiol also received a 4% micronized progesterone vaginal gel, while those who had an intact uterus and took placebo also received a matching placebo gel.

The participants were stratified according to the number of years they were past menopause: less than 6 years (271 women in the “early” group) or more than 10 years (372 in the “late” group).

A total of 137 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to active estradiol, while 134 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to placebo. As expected, serum estradiol levels were at least 3 times higher among women assigned to active treatment, compared with those assigned to placebo.

The primary outcome – the effect of hormone therapy on CIMT progression – differed by timing of the initiation of treatment. In the “early” group, the mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo.

In contrast, in the “late” group, the rates of CIMT progression were not significantly different between estradiol and placebo, the investigators wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1221-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241).

This beneficial effect remained significant in a sensitivity analysis restricted only to study participants who showed at least 80% adherence to their assigned treatment. The benefit also remained significant in a post-hoc analysis comparing women who took estradiol alone against those who took estradiol plus progestogen, as well as in a separate analysis comparing women who used lipid-lowering and/or hypertensive medications against those who did not.

The findings add further evidence in favor of the hormone timing hypothesis. The effect of estradiol therapy on CIMT progression was significantly modified by time since menopause (P = .007 for the interaction), the researchers wrote.

Cardiac computer tomography (CT) was used as a different method of assessing coronary atherosclerosis in a subgroup of 167 women in the early group (88 receiving estradiol and 79 receiving placebo) and 214 in the late group (101 receiving estradiol and 113 receiving placebo). The timing of estradiol treatment did not affect coronary artery calcium and other cardiac CT measures. This is consistent with previous reports that hormone therapy has no significant effect on established lesions in the coronary arteries, the researchers wrote.

The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.

Hormone therapy – estradiol with or without progesterone – only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause onset, according to a report published online March 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The “hormone-timing hypothesis” posits that hormone therapy’s beneficial effects on atherosclerosis depend on the timing of initiating that therapy relative to menopause. To test this hypothesis, researchers began the ELITE study (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) in 2002, using serial noninvasive measurements of carotid-artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a marker of atherosclerosis progression.

Several other studies since 2002 have reported that the timing hypothesis appears to be valid, wrote Dr. Howard N. Hodis of the Atherosclerosis Research Unit, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and his associates.

Their single-center trial involved 643 healthy postmenopausal women who had no diabetes and no evidence of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and who were randomly assigned to receive either daily oral estradiol or a matching placebo for 5 years. Women who had an intact uterus and took active estradiol also received a 4% micronized progesterone vaginal gel, while those who had an intact uterus and took placebo also received a matching placebo gel.

The participants were stratified according to the number of years they were past menopause: less than 6 years (271 women in the “early” group) or more than 10 years (372 in the “late” group).

A total of 137 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to active estradiol, while 134 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to placebo. As expected, serum estradiol levels were at least 3 times higher among women assigned to active treatment, compared with those assigned to placebo.

The primary outcome – the effect of hormone therapy on CIMT progression – differed by timing of the initiation of treatment. In the “early” group, the mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo.

In contrast, in the “late” group, the rates of CIMT progression were not significantly different between estradiol and placebo, the investigators wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1221-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241).

This beneficial effect remained significant in a sensitivity analysis restricted only to study participants who showed at least 80% adherence to their assigned treatment. The benefit also remained significant in a post-hoc analysis comparing women who took estradiol alone against those who took estradiol plus progestogen, as well as in a separate analysis comparing women who used lipid-lowering and/or hypertensive medications against those who did not.

The findings add further evidence in favor of the hormone timing hypothesis. The effect of estradiol therapy on CIMT progression was significantly modified by time since menopause (P = .007 for the interaction), the researchers wrote.

Cardiac computer tomography (CT) was used as a different method of assessing coronary atherosclerosis in a subgroup of 167 women in the early group (88 receiving estradiol and 79 receiving placebo) and 214 in the late group (101 receiving estradiol and 113 receiving placebo). The timing of estradiol treatment did not affect coronary artery calcium and other cardiac CT measures. This is consistent with previous reports that hormone therapy has no significant effect on established lesions in the coronary arteries, the researchers wrote.

The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Estradiol only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause, not later.

Major finding: The mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo, but only in women who initiated hormone therapy within 6 years of menopause onset.

Data source: A single-center randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 643 healthy postmenopausal women treated for 5 years.

Disclosures: The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.

Can CA 125 screening reduce mortality from ovarian cancer?

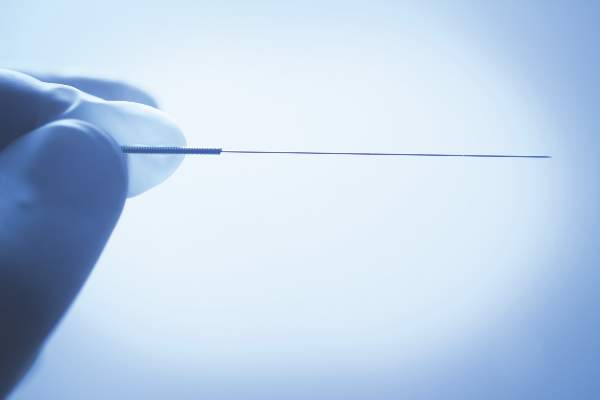

To date, screening has not been found effective in reducing mortality from ovarian cancer. Collaborative trial investigators in the United Kingdom studied postmenopausal women in the general population to assess whether early detection by screening could decrease ovarian cancer mortality.

Details of the study

During 2001 to 2005, more than 200,000 UK postmenopausal women aged 50 to 74 years (mean age at baseline, 60.6 years) were randomly assigned to no screening, annual transvaginal ultrasound screening (TVUS), or annual multimodal screening (MMS) with serum CA 125 using the Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm (ROCA), which takes into account changes in CA 125 levels over time. When ROCA scores indicated normal risk for ovarian cancer, women were advised to undergo repeat CA 125 assessment in 1 year. Women with intermediate risk were advised to repeat CA 125 assessment in 3 months, while high-risk women were advised to undergo TVUS.

With a median of 11.1 years of follow-up, ovarian cancer (including fallopian tube malignancies) was diagnosed in 1,282 participants (0.6%), with fatal outcomes among the 3 groups as follows: 0.34% in the no-screening group, 0.30% in the TVUS group, and 0.29% in the MMS group. Based on the results of a planned secondary analysis that excluded prevalent cases of ovarian cancer, annual MMS was associated with an overall average mortality reduction of 20% compared with no screening (P = .021). When the mortality reduction was broken down by years of annual screening, 0 to 7 years was associated with an 8% mortality reduction over no screening, and this jumped to 28% for 7 to 14 annual MMS screening years.

The overall average mortality reduction with TVUS compared with no screening was smaller than with MMS. With MMS, the number needed to screen to prevent 1 death from ovarian cancer was 641.

Assessing unnecessary treatment

False-positive screens that resulted in surgical intervention with findings of benign adnexal pathology or normal adnexa occurred in 14 and 50 per 10,000 screens in the MMS and TVUS groups, respectively. For each ovarian cancer detected in the MMS and TVUS groups, an additional 2 and 10 women, respectively, underwent surgery based on false-positive results.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This massive trial’s findings provide optimism that screening for ovarian cancer can indeed reduce mortality from this uncommon but too-often lethal disease. There are unanswered questions, however, which include the cost-effectiveness of MMS screening and how well this strategy can be implemented outside of a highly centralized and controlled clinical trial. While encouraging, these trial results should be viewed as preliminary until additional efficacy and cost-effectiveness data—and guidance from professional organizations—are available.

—ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

To date, screening has not been found effective in reducing mortality from ovarian cancer. Collaborative trial investigators in the United Kingdom studied postmenopausal women in the general population to assess whether early detection by screening could decrease ovarian cancer mortality.

Details of the study

During 2001 to 2005, more than 200,000 UK postmenopausal women aged 50 to 74 years (mean age at baseline, 60.6 years) were randomly assigned to no screening, annual transvaginal ultrasound screening (TVUS), or annual multimodal screening (MMS) with serum CA 125 using the Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm (ROCA), which takes into account changes in CA 125 levels over time. When ROCA scores indicated normal risk for ovarian cancer, women were advised to undergo repeat CA 125 assessment in 1 year. Women with intermediate risk were advised to repeat CA 125 assessment in 3 months, while high-risk women were advised to undergo TVUS.

With a median of 11.1 years of follow-up, ovarian cancer (including fallopian tube malignancies) was diagnosed in 1,282 participants (0.6%), with fatal outcomes among the 3 groups as follows: 0.34% in the no-screening group, 0.30% in the TVUS group, and 0.29% in the MMS group. Based on the results of a planned secondary analysis that excluded prevalent cases of ovarian cancer, annual MMS was associated with an overall average mortality reduction of 20% compared with no screening (P = .021). When the mortality reduction was broken down by years of annual screening, 0 to 7 years was associated with an 8% mortality reduction over no screening, and this jumped to 28% for 7 to 14 annual MMS screening years.

The overall average mortality reduction with TVUS compared with no screening was smaller than with MMS. With MMS, the number needed to screen to prevent 1 death from ovarian cancer was 641.

Assessing unnecessary treatment

False-positive screens that resulted in surgical intervention with findings of benign adnexal pathology or normal adnexa occurred in 14 and 50 per 10,000 screens in the MMS and TVUS groups, respectively. For each ovarian cancer detected in the MMS and TVUS groups, an additional 2 and 10 women, respectively, underwent surgery based on false-positive results.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This massive trial’s findings provide optimism that screening for ovarian cancer can indeed reduce mortality from this uncommon but too-often lethal disease. There are unanswered questions, however, which include the cost-effectiveness of MMS screening and how well this strategy can be implemented outside of a highly centralized and controlled clinical trial. While encouraging, these trial results should be viewed as preliminary until additional efficacy and cost-effectiveness data—and guidance from professional organizations—are available.

—ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

To date, screening has not been found effective in reducing mortality from ovarian cancer. Collaborative trial investigators in the United Kingdom studied postmenopausal women in the general population to assess whether early detection by screening could decrease ovarian cancer mortality.

Details of the study

During 2001 to 2005, more than 200,000 UK postmenopausal women aged 50 to 74 years (mean age at baseline, 60.6 years) were randomly assigned to no screening, annual transvaginal ultrasound screening (TVUS), or annual multimodal screening (MMS) with serum CA 125 using the Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm (ROCA), which takes into account changes in CA 125 levels over time. When ROCA scores indicated normal risk for ovarian cancer, women were advised to undergo repeat CA 125 assessment in 1 year. Women with intermediate risk were advised to repeat CA 125 assessment in 3 months, while high-risk women were advised to undergo TVUS.

With a median of 11.1 years of follow-up, ovarian cancer (including fallopian tube malignancies) was diagnosed in 1,282 participants (0.6%), with fatal outcomes among the 3 groups as follows: 0.34% in the no-screening group, 0.30% in the TVUS group, and 0.29% in the MMS group. Based on the results of a planned secondary analysis that excluded prevalent cases of ovarian cancer, annual MMS was associated with an overall average mortality reduction of 20% compared with no screening (P = .021). When the mortality reduction was broken down by years of annual screening, 0 to 7 years was associated with an 8% mortality reduction over no screening, and this jumped to 28% for 7 to 14 annual MMS screening years.

The overall average mortality reduction with TVUS compared with no screening was smaller than with MMS. With MMS, the number needed to screen to prevent 1 death from ovarian cancer was 641.

Assessing unnecessary treatment

False-positive screens that resulted in surgical intervention with findings of benign adnexal pathology or normal adnexa occurred in 14 and 50 per 10,000 screens in the MMS and TVUS groups, respectively. For each ovarian cancer detected in the MMS and TVUS groups, an additional 2 and 10 women, respectively, underwent surgery based on false-positive results.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This massive trial’s findings provide optimism that screening for ovarian cancer can indeed reduce mortality from this uncommon but too-often lethal disease. There are unanswered questions, however, which include the cost-effectiveness of MMS screening and how well this strategy can be implemented outside of a highly centralized and controlled clinical trial. While encouraging, these trial results should be viewed as preliminary until additional efficacy and cost-effectiveness data—and guidance from professional organizations—are available.

—ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Readers weigh in on vaginal cleansing prior to cesarean delivery

“SHOULD YOU ADOPT THE PRACTICE OF VAGINAL CLEANSING WITH POVIDONE-IODINE PRIOR TO CESAREAN DELIVERY?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; JANUARY 2016)

In his January 2016 Editorial, Editor in Chief Robert L. Barbieri, MD, presented evidence supporting the practice of vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine prior to cesarean delivery (CD) to prevent postoperative endometritis. He then asked readers if they would consider adopting such a practice. More than 250 readers weighed in through the Quick Poll at obgmanagement.com, and many readers sent in letters with follow-up questions and comments on controlling bacterial contamination, vaginal seeding, etc. Here are some of the letters, along with Dr. Barbieri’s response and the Quick Poll results.

A contradiction in definitions?

There seems to be a contradiction in definitions. The second sentence of the article defines endometritis as the presence of fever plus low abdominal tenderness. However, the studies presented state that vaginal cleansing pre-CD decreased endometritis but did not decrease postpartum fever. Is this not a discrepancy?

Nancy Kerr, MD, MPH

Albuquerque, New Mexico

A question about povidone-iodine

Have any studies been done on newborn iodine levels after vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine prior to CD?

G. Millard Simmons Jr, MD

Hilton Head, Bluffton, South Carolina

Additional tips for controlling bacterial contamination

Dr. Barbieri’s editorial on vaginal cleansing prior to CD is eye opening. I have a few additional suggestions to control bacterial contamination.