User login

Primary hPTH often goes unnoticed

SAN FRANCISCO – Primary hyperparathyroidism was detected in 7% of 742 patients with recurrent kidney stones at a single tertiary care clinic, and the patients’ primary care physicians may have missed the diagnosis because several affected patients’ calcium levels were in the high normal range.

Of the 53 patients diagnosed with primary hyperparathyroidism (hPTH), 72% had high normal serum calcium levels. After examining the charts of those patients, researchers found that 11 of the 53 patients (21%) had been tested for parathyroid hormone and serum calcium levels and could have been identified by their primary care physicians.

None of the 742 patients with kidney stones in the study had vitamin D deficiency or gastrointestinal malabsorption. All were tested for serum calcium and intact serum PTH, and those with hypercalcemia or high normal calcium (greater than 10 mg/dL) and elevated intact serum PTH were diagnosed with primary hPTH.

The findings emphasize “the importance of [looking] for not just outright primary hyperparathyroidism, but the ratio between PTH and calcium levels,” said Mr. Boyd.

The study received no funding. Mr. Boyd declared no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Boyd C et al. AUA 2018, Abstract MP13-03.

SAN FRANCISCO – Primary hyperparathyroidism was detected in 7% of 742 patients with recurrent kidney stones at a single tertiary care clinic, and the patients’ primary care physicians may have missed the diagnosis because several affected patients’ calcium levels were in the high normal range.

Of the 53 patients diagnosed with primary hyperparathyroidism (hPTH), 72% had high normal serum calcium levels. After examining the charts of those patients, researchers found that 11 of the 53 patients (21%) had been tested for parathyroid hormone and serum calcium levels and could have been identified by their primary care physicians.

None of the 742 patients with kidney stones in the study had vitamin D deficiency or gastrointestinal malabsorption. All were tested for serum calcium and intact serum PTH, and those with hypercalcemia or high normal calcium (greater than 10 mg/dL) and elevated intact serum PTH were diagnosed with primary hPTH.

The findings emphasize “the importance of [looking] for not just outright primary hyperparathyroidism, but the ratio between PTH and calcium levels,” said Mr. Boyd.

The study received no funding. Mr. Boyd declared no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Boyd C et al. AUA 2018, Abstract MP13-03.

SAN FRANCISCO – Primary hyperparathyroidism was detected in 7% of 742 patients with recurrent kidney stones at a single tertiary care clinic, and the patients’ primary care physicians may have missed the diagnosis because several affected patients’ calcium levels were in the high normal range.

Of the 53 patients diagnosed with primary hyperparathyroidism (hPTH), 72% had high normal serum calcium levels. After examining the charts of those patients, researchers found that 11 of the 53 patients (21%) had been tested for parathyroid hormone and serum calcium levels and could have been identified by their primary care physicians.

None of the 742 patients with kidney stones in the study had vitamin D deficiency or gastrointestinal malabsorption. All were tested for serum calcium and intact serum PTH, and those with hypercalcemia or high normal calcium (greater than 10 mg/dL) and elevated intact serum PTH were diagnosed with primary hPTH.

The findings emphasize “the importance of [looking] for not just outright primary hyperparathyroidism, but the ratio between PTH and calcium levels,” said Mr. Boyd.

The study received no funding. Mr. Boyd declared no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Boyd C et al. AUA 2018, Abstract MP13-03.

REPORTING FROM THE AUA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Calcium levels in the high normal range may be confounding diagnoses.

Major finding: About 20% of primary hyperparathyroidism cases could have been spotted by the primary care physician based on tests that had been ordered.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 742 patients at a tertiary care kidney stone clinic.

Disclosures: The study received no funding. Mr. Boyd declared no relevant financial relationships.

Source: Boyd C et al. AUA 2018, Abstract MP13-03.

Testosterone therapy tied to kidney stone risk

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to an analysis of more than 50,000 men with low testosterone.

When researchers compared hypogonadal men to age- and comorbidity-matched controls, they found a statistically significantly higher number of clinical diagnoses of a kidney stone, or of patients undergoing a kidney stone–related procedure.

The new study is the first large-scale analysis of the question in humans, according to Tyler McClintock, MD, who presented the findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association. Dr. McClintock is a urology resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Dr. McClintock and his colleagues analyzed data from the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR). The MDR includes beneficiaries of the TRICARE program for service members, retirees, and their families. They looked at 26,586 men aged 40-64 years who had been diagnosed with low testosterone and who had received continuous testosterone replacement therapy between April 2006 and March 2014. The researchers compared them to 26,586 controls with low testosterone who did not receive testosterone replacement therapy.

Stone events were significantly higher in the treatment group. There were 67 extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy procedures in the treatment group, compared with 51 among controls. Similar trends were seen with ureteroscopy with lithotripsy (75 vs. 46) and clinical diagnoses of kidney stone (1,059 vs. 794).

The researchers also broke down stone events by type of testosterone replacement therapy. A total of 5.4% of patients who received pellets (9 of 167) experienced an event (P = .27), compared with 5.1% of those who received injections (218 of 4,259; P = .004) and 3.5% of those who received it topically (655 of 18,895; P less than .0001).

At 2 years, Dr. McClintock reported that there were significantly more kidney stone events in the testosterone-treated group than in the untreated group (659 and 482, respectively; P less than .001). Two years after starting testosterone replacement therapy, significantly more of the treatment group had experienced a stone episode, compared with the matched controls during the same time period (3.9% and 3%, respectively; P less than .001).

Dr. McClintock said the study is convincing in part because it used data from TRICARE, which sets a lower testosterone level even than AUA guidelines for determining if a patient is eligible for testosterone therapy.

“It would suggest that those are the real low testosterone patients, not necessarily men who heard an ad or went to a test center,” noted Patrick Shepherd Lowry, MD, associate professor of urology at Scott & White Medical Center, Temple, Texas, who attended the presentation but was not involved in the study. “It’s preliminary, but it’s very interesting. It hasn’t been shown before.”

The Department of Defense funded the study. Dr. McClintock reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McClintock T. AUA Annual Meeting. Abstract MP13-19.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to an analysis of more than 50,000 men with low testosterone.

When researchers compared hypogonadal men to age- and comorbidity-matched controls, they found a statistically significantly higher number of clinical diagnoses of a kidney stone, or of patients undergoing a kidney stone–related procedure.

The new study is the first large-scale analysis of the question in humans, according to Tyler McClintock, MD, who presented the findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association. Dr. McClintock is a urology resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Dr. McClintock and his colleagues analyzed data from the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR). The MDR includes beneficiaries of the TRICARE program for service members, retirees, and their families. They looked at 26,586 men aged 40-64 years who had been diagnosed with low testosterone and who had received continuous testosterone replacement therapy between April 2006 and March 2014. The researchers compared them to 26,586 controls with low testosterone who did not receive testosterone replacement therapy.

Stone events were significantly higher in the treatment group. There were 67 extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy procedures in the treatment group, compared with 51 among controls. Similar trends were seen with ureteroscopy with lithotripsy (75 vs. 46) and clinical diagnoses of kidney stone (1,059 vs. 794).

The researchers also broke down stone events by type of testosterone replacement therapy. A total of 5.4% of patients who received pellets (9 of 167) experienced an event (P = .27), compared with 5.1% of those who received injections (218 of 4,259; P = .004) and 3.5% of those who received it topically (655 of 18,895; P less than .0001).

At 2 years, Dr. McClintock reported that there were significantly more kidney stone events in the testosterone-treated group than in the untreated group (659 and 482, respectively; P less than .001). Two years after starting testosterone replacement therapy, significantly more of the treatment group had experienced a stone episode, compared with the matched controls during the same time period (3.9% and 3%, respectively; P less than .001).

Dr. McClintock said the study is convincing in part because it used data from TRICARE, which sets a lower testosterone level even than AUA guidelines for determining if a patient is eligible for testosterone therapy.

“It would suggest that those are the real low testosterone patients, not necessarily men who heard an ad or went to a test center,” noted Patrick Shepherd Lowry, MD, associate professor of urology at Scott & White Medical Center, Temple, Texas, who attended the presentation but was not involved in the study. “It’s preliminary, but it’s very interesting. It hasn’t been shown before.”

The Department of Defense funded the study. Dr. McClintock reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McClintock T. AUA Annual Meeting. Abstract MP13-19.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to an analysis of more than 50,000 men with low testosterone.

When researchers compared hypogonadal men to age- and comorbidity-matched controls, they found a statistically significantly higher number of clinical diagnoses of a kidney stone, or of patients undergoing a kidney stone–related procedure.

The new study is the first large-scale analysis of the question in humans, according to Tyler McClintock, MD, who presented the findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association. Dr. McClintock is a urology resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Dr. McClintock and his colleagues analyzed data from the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR). The MDR includes beneficiaries of the TRICARE program for service members, retirees, and their families. They looked at 26,586 men aged 40-64 years who had been diagnosed with low testosterone and who had received continuous testosterone replacement therapy between April 2006 and March 2014. The researchers compared them to 26,586 controls with low testosterone who did not receive testosterone replacement therapy.

Stone events were significantly higher in the treatment group. There were 67 extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy procedures in the treatment group, compared with 51 among controls. Similar trends were seen with ureteroscopy with lithotripsy (75 vs. 46) and clinical diagnoses of kidney stone (1,059 vs. 794).

The researchers also broke down stone events by type of testosterone replacement therapy. A total of 5.4% of patients who received pellets (9 of 167) experienced an event (P = .27), compared with 5.1% of those who received injections (218 of 4,259; P = .004) and 3.5% of those who received it topically (655 of 18,895; P less than .0001).

At 2 years, Dr. McClintock reported that there were significantly more kidney stone events in the testosterone-treated group than in the untreated group (659 and 482, respectively; P less than .001). Two years after starting testosterone replacement therapy, significantly more of the treatment group had experienced a stone episode, compared with the matched controls during the same time period (3.9% and 3%, respectively; P less than .001).

Dr. McClintock said the study is convincing in part because it used data from TRICARE, which sets a lower testosterone level even than AUA guidelines for determining if a patient is eligible for testosterone therapy.

“It would suggest that those are the real low testosterone patients, not necessarily men who heard an ad or went to a test center,” noted Patrick Shepherd Lowry, MD, associate professor of urology at Scott & White Medical Center, Temple, Texas, who attended the presentation but was not involved in the study. “It’s preliminary, but it’s very interesting. It hasn’t been shown before.”

The Department of Defense funded the study. Dr. McClintock reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McClintock T. AUA Annual Meeting. Abstract MP13-19.

REPORTING FROM THE AUA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Kidney stone risk may be a factor when considering testosterone replacement therapy.

Major finding: In untreated men, 482 kidney stone events occurred, compared with 659 in those receiving testosterone.

Study details: A case-control analysis of 26,586 treated men and 26,586 matched controls.

Disclosures: The Department of Defense funded the study. Dr. McClintock reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: McClintock T. AUA Annual Meeting. Abstract MP13-19.

CKD triples risk of bad outcomes in HIV

BOSTON – A lot of people do well with HIV thanks to potent antiretrovirals, but there’s still at least one group that needs extra attention: HIV patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to Lene Ryom, MD, PhD, an HIV researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

She was the lead investigator on a review of 2,467 HIV patients with CKD – which is becoming more common in HIV as patients live longer – and 33,427 HIV patients without CKD.

The incidence of serious clinical events following CKD diagnosis was 68.9 events per 1,000 patient-years. Among the HIV patients without CKD, the incidence was 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

“In an era when many HIV patients require much less management due to effective antiretroviral treatment, those living with CKD have a much higher burden of serious clinical events and require much closer monitoring. Modifiable risk factors ... play a central role in CKD morbidity and mortality, highlighting the need for increased awareness, effective treatment, and preventative measures. In particular, smoking seems to be quite important for all” serious adverse outcomes, “so that’s a good place to start,” Dr. Ryom said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Most of the 2,467 HIV patients with CKD were white men who have sex with men. At baseline, the median age was 60 years, and median CD4 cell count was above 500. One in three were smokers, 22.4% were HCV positive, and most had viral loads below 400 copies/mL. More than half of the patients were estimated to have died within 5 years of CKD diagnosis.

CKD was defined as two estimated glomerular filtration rates at or below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 taken at least 3 months apart, or a 25% decrease in eGFR when patients entered the study at that level.

The subjects were all participants in the D:A:D project [Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs], an ongoing international cohort study based at the University of Copenhagen, and funded by pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Dr. Ryom had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

BOSTON – A lot of people do well with HIV thanks to potent antiretrovirals, but there’s still at least one group that needs extra attention: HIV patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to Lene Ryom, MD, PhD, an HIV researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

She was the lead investigator on a review of 2,467 HIV patients with CKD – which is becoming more common in HIV as patients live longer – and 33,427 HIV patients without CKD.

The incidence of serious clinical events following CKD diagnosis was 68.9 events per 1,000 patient-years. Among the HIV patients without CKD, the incidence was 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

“In an era when many HIV patients require much less management due to effective antiretroviral treatment, those living with CKD have a much higher burden of serious clinical events and require much closer monitoring. Modifiable risk factors ... play a central role in CKD morbidity and mortality, highlighting the need for increased awareness, effective treatment, and preventative measures. In particular, smoking seems to be quite important for all” serious adverse outcomes, “so that’s a good place to start,” Dr. Ryom said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Most of the 2,467 HIV patients with CKD were white men who have sex with men. At baseline, the median age was 60 years, and median CD4 cell count was above 500. One in three were smokers, 22.4% were HCV positive, and most had viral loads below 400 copies/mL. More than half of the patients were estimated to have died within 5 years of CKD diagnosis.

CKD was defined as two estimated glomerular filtration rates at or below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 taken at least 3 months apart, or a 25% decrease in eGFR when patients entered the study at that level.

The subjects were all participants in the D:A:D project [Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs], an ongoing international cohort study based at the University of Copenhagen, and funded by pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Dr. Ryom had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

BOSTON – A lot of people do well with HIV thanks to potent antiretrovirals, but there’s still at least one group that needs extra attention: HIV patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to Lene Ryom, MD, PhD, an HIV researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

She was the lead investigator on a review of 2,467 HIV patients with CKD – which is becoming more common in HIV as patients live longer – and 33,427 HIV patients without CKD.

The incidence of serious clinical events following CKD diagnosis was 68.9 events per 1,000 patient-years. Among the HIV patients without CKD, the incidence was 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

“In an era when many HIV patients require much less management due to effective antiretroviral treatment, those living with CKD have a much higher burden of serious clinical events and require much closer monitoring. Modifiable risk factors ... play a central role in CKD morbidity and mortality, highlighting the need for increased awareness, effective treatment, and preventative measures. In particular, smoking seems to be quite important for all” serious adverse outcomes, “so that’s a good place to start,” Dr. Ryom said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Most of the 2,467 HIV patients with CKD were white men who have sex with men. At baseline, the median age was 60 years, and median CD4 cell count was above 500. One in three were smokers, 22.4% were HCV positive, and most had viral loads below 400 copies/mL. More than half of the patients were estimated to have died within 5 years of CKD diagnosis.

CKD was defined as two estimated glomerular filtration rates at or below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 taken at least 3 months apart, or a 25% decrease in eGFR when patients entered the study at that level.

The subjects were all participants in the D:A:D project [Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs], an ongoing international cohort study based at the University of Copenhagen, and funded by pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Dr. Ryom had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

REPORTING FROM CROI

Key clinical point: Smoking, diabetes, dyslipidemia, low body mass index, and poor HIV control increase the risk of poor outcomes in HIV patients who have chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: In HIV patients with CKD, the incidence of a serious clinical event is 68.9 per 1,000 patient-years; in HIV patients without CKD, it’s 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

Study details: Review of nearly 36,000 HIV patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures. Funding came from pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Source: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

CANVAS: Canagliflozin improved renal outcomes in diabetes

AUSTIN, TEX. – Canagliflozin can improve renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, even when they have mild or moderate kidney disease, new data from the CANVAS program suggested.

“The effect of canagliflozin on composite renal outcomes was large, particularly in people with preserved kidney function,” Brendon L. Neuen, MBBS, of University of New South Wales, Sydney, and his associates wrote in a poster. Baseline renal function also did not appear to affect the safety of canagliflozin, the investigators reported at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

In patients with diabetes mellitus, increased proximal reabsorption of glucose and sodium decreases the amount of sodium reaching the macula densa in the distal convoluted tubule. This results in reduced use of adenosine triphosphate for sodium reabsorption, which thereby decreases adenosine release and vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. Left unchecked, this dampening of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism increases glomerular filtration and leads to diabetic nephropathy.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as canagliflozin (Invokana) and empagliflozin (Jardiance) help mitigate this pathology by vasoconstricting afferent arterioles. Previously, in an exploratory analysis of the multicenter, placebo-controlled EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes) trial, empagliflozin led to modest but statistically significant long-term reductions in urinary albumin secretion for diabetic patients, regardless of their baseline urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Aug;5[8]:610-21). Treatment with empagliflozin also significantly reduced the risk of developing microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (P less than .0001).

The multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) and CANVAS-R (A Study of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal Endpoints in Adult Participants with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) trials included more than 10,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. In the primary analysis, canagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:644-57).

Dr. Neuen and his associates compared the effects of canagliflozin on renal outcomes and safety among CANVAS patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was preserved (greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Actual mean eGFRs in each of these groups were 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 49 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with placebo, canagliflozin acutely reduced eGFR in patients with either preserved (average, –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (–2.83 mL/min/1.73 m2 ) baseline kidney function (P = 0.21).

Among patients with preserved function at baseline, canagliflozin was associated with a statistically significant 47% decrease in risk of renal death, end-stage kidney disease, or a 40% or greater drop in eGFR (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.73). Canagliflozin also showed renal benefits for patients with reduced kidney function, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.49-1.17). Findings were similar when the researchers tweaked the composite renal endpoint by replacing the eGFR criterion with doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75 and HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.37-1.77, respectively).

Canagliflozin has a black box warning for amputation risk. There was no indication that early renal function further increased this risk, the researchers reported. CANVAS patients who received canagliflozin underwent amputations (usually at the level of the toe or metatarsal) at rates of 6.3 per 1,000 person-years overall, 5.6 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of preserved kidney function, and 9.9 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of reduced kidney function. Rates in the placebo group were 3.4, 3.0, and 4.8 amputations per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Additionally, baseline renal status did not significantly affect risk of fracture, serious kidney-related adverse events, or serious acute kidney injury. Patients with baseline renal insufficiency were at increased risk of developing serious hyperkalemia (HR, 2.11; P = .06), but these events were uncommon in both treatment groups.

No CANVAS patient had stage 4 or worse kidney disease (eGFR less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) at enrollment, the researchers noted. The ongoing phase 3 CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation) trial will shed more light on canagliflozin in the setting of renal disease, they added. This multicenter, double-blind trial compares canagliflozin with placebo in more than 4,000 patients with diabetic nephropathy. Results are expected in 2019.

Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials. Disclosures were not provided.

SOURCE: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Canagliflozin can improve renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, even when they have mild or moderate kidney disease, new data from the CANVAS program suggested.

“The effect of canagliflozin on composite renal outcomes was large, particularly in people with preserved kidney function,” Brendon L. Neuen, MBBS, of University of New South Wales, Sydney, and his associates wrote in a poster. Baseline renal function also did not appear to affect the safety of canagliflozin, the investigators reported at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

In patients with diabetes mellitus, increased proximal reabsorption of glucose and sodium decreases the amount of sodium reaching the macula densa in the distal convoluted tubule. This results in reduced use of adenosine triphosphate for sodium reabsorption, which thereby decreases adenosine release and vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. Left unchecked, this dampening of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism increases glomerular filtration and leads to diabetic nephropathy.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as canagliflozin (Invokana) and empagliflozin (Jardiance) help mitigate this pathology by vasoconstricting afferent arterioles. Previously, in an exploratory analysis of the multicenter, placebo-controlled EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes) trial, empagliflozin led to modest but statistically significant long-term reductions in urinary albumin secretion for diabetic patients, regardless of their baseline urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Aug;5[8]:610-21). Treatment with empagliflozin also significantly reduced the risk of developing microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (P less than .0001).

The multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) and CANVAS-R (A Study of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal Endpoints in Adult Participants with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) trials included more than 10,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. In the primary analysis, canagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:644-57).

Dr. Neuen and his associates compared the effects of canagliflozin on renal outcomes and safety among CANVAS patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was preserved (greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Actual mean eGFRs in each of these groups were 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 49 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with placebo, canagliflozin acutely reduced eGFR in patients with either preserved (average, –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (–2.83 mL/min/1.73 m2 ) baseline kidney function (P = 0.21).

Among patients with preserved function at baseline, canagliflozin was associated with a statistically significant 47% decrease in risk of renal death, end-stage kidney disease, or a 40% or greater drop in eGFR (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.73). Canagliflozin also showed renal benefits for patients with reduced kidney function, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.49-1.17). Findings were similar when the researchers tweaked the composite renal endpoint by replacing the eGFR criterion with doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75 and HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.37-1.77, respectively).

Canagliflozin has a black box warning for amputation risk. There was no indication that early renal function further increased this risk, the researchers reported. CANVAS patients who received canagliflozin underwent amputations (usually at the level of the toe or metatarsal) at rates of 6.3 per 1,000 person-years overall, 5.6 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of preserved kidney function, and 9.9 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of reduced kidney function. Rates in the placebo group were 3.4, 3.0, and 4.8 amputations per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Additionally, baseline renal status did not significantly affect risk of fracture, serious kidney-related adverse events, or serious acute kidney injury. Patients with baseline renal insufficiency were at increased risk of developing serious hyperkalemia (HR, 2.11; P = .06), but these events were uncommon in both treatment groups.

No CANVAS patient had stage 4 or worse kidney disease (eGFR less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) at enrollment, the researchers noted. The ongoing phase 3 CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation) trial will shed more light on canagliflozin in the setting of renal disease, they added. This multicenter, double-blind trial compares canagliflozin with placebo in more than 4,000 patients with diabetic nephropathy. Results are expected in 2019.

Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials. Disclosures were not provided.

SOURCE: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Canagliflozin can improve renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, even when they have mild or moderate kidney disease, new data from the CANVAS program suggested.

“The effect of canagliflozin on composite renal outcomes was large, particularly in people with preserved kidney function,” Brendon L. Neuen, MBBS, of University of New South Wales, Sydney, and his associates wrote in a poster. Baseline renal function also did not appear to affect the safety of canagliflozin, the investigators reported at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

In patients with diabetes mellitus, increased proximal reabsorption of glucose and sodium decreases the amount of sodium reaching the macula densa in the distal convoluted tubule. This results in reduced use of adenosine triphosphate for sodium reabsorption, which thereby decreases adenosine release and vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. Left unchecked, this dampening of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism increases glomerular filtration and leads to diabetic nephropathy.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as canagliflozin (Invokana) and empagliflozin (Jardiance) help mitigate this pathology by vasoconstricting afferent arterioles. Previously, in an exploratory analysis of the multicenter, placebo-controlled EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes) trial, empagliflozin led to modest but statistically significant long-term reductions in urinary albumin secretion for diabetic patients, regardless of their baseline urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Aug;5[8]:610-21). Treatment with empagliflozin also significantly reduced the risk of developing microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (P less than .0001).

The multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) and CANVAS-R (A Study of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal Endpoints in Adult Participants with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) trials included more than 10,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. In the primary analysis, canagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:644-57).

Dr. Neuen and his associates compared the effects of canagliflozin on renal outcomes and safety among CANVAS patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was preserved (greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Actual mean eGFRs in each of these groups were 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and 49 mL/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with placebo, canagliflozin acutely reduced eGFR in patients with either preserved (average, –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2) or reduced (–2.83 mL/min/1.73 m2 ) baseline kidney function (P = 0.21).

Among patients with preserved function at baseline, canagliflozin was associated with a statistically significant 47% decrease in risk of renal death, end-stage kidney disease, or a 40% or greater drop in eGFR (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.73). Canagliflozin also showed renal benefits for patients with reduced kidney function, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.49-1.17). Findings were similar when the researchers tweaked the composite renal endpoint by replacing the eGFR criterion with doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75 and HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.37-1.77, respectively).

Canagliflozin has a black box warning for amputation risk. There was no indication that early renal function further increased this risk, the researchers reported. CANVAS patients who received canagliflozin underwent amputations (usually at the level of the toe or metatarsal) at rates of 6.3 per 1,000 person-years overall, 5.6 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of preserved kidney function, and 9.9 per 1,000 person-years in the setting of reduced kidney function. Rates in the placebo group were 3.4, 3.0, and 4.8 amputations per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Additionally, baseline renal status did not significantly affect risk of fracture, serious kidney-related adverse events, or serious acute kidney injury. Patients with baseline renal insufficiency were at increased risk of developing serious hyperkalemia (HR, 2.11; P = .06), but these events were uncommon in both treatment groups.

No CANVAS patient had stage 4 or worse kidney disease (eGFR less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) at enrollment, the researchers noted. The ongoing phase 3 CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation) trial will shed more light on canagliflozin in the setting of renal disease, they added. This multicenter, double-blind trial compares canagliflozin with placebo in more than 4,000 patients with diabetic nephropathy. Results are expected in 2019.

Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials. Disclosures were not provided.

SOURCE: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

REPORTING FROM SCM 18

Key clinical point: Canagliflozin improved kidney function and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: Reduction in risk of a composite endpoint (end-stage kidney disease, renal death, or at least 40% decline in eGFR) was 47% for patients with preserved baseline kidney function and 24% for patients with reduced baseline function.

Study details: Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of 10,140 patients (CANVAS and CANVAS-R).

Disclosures: Janssen funded the CANVAS and CANVAS-R trials.

Source: Neuen BL et al. SCM 2018.

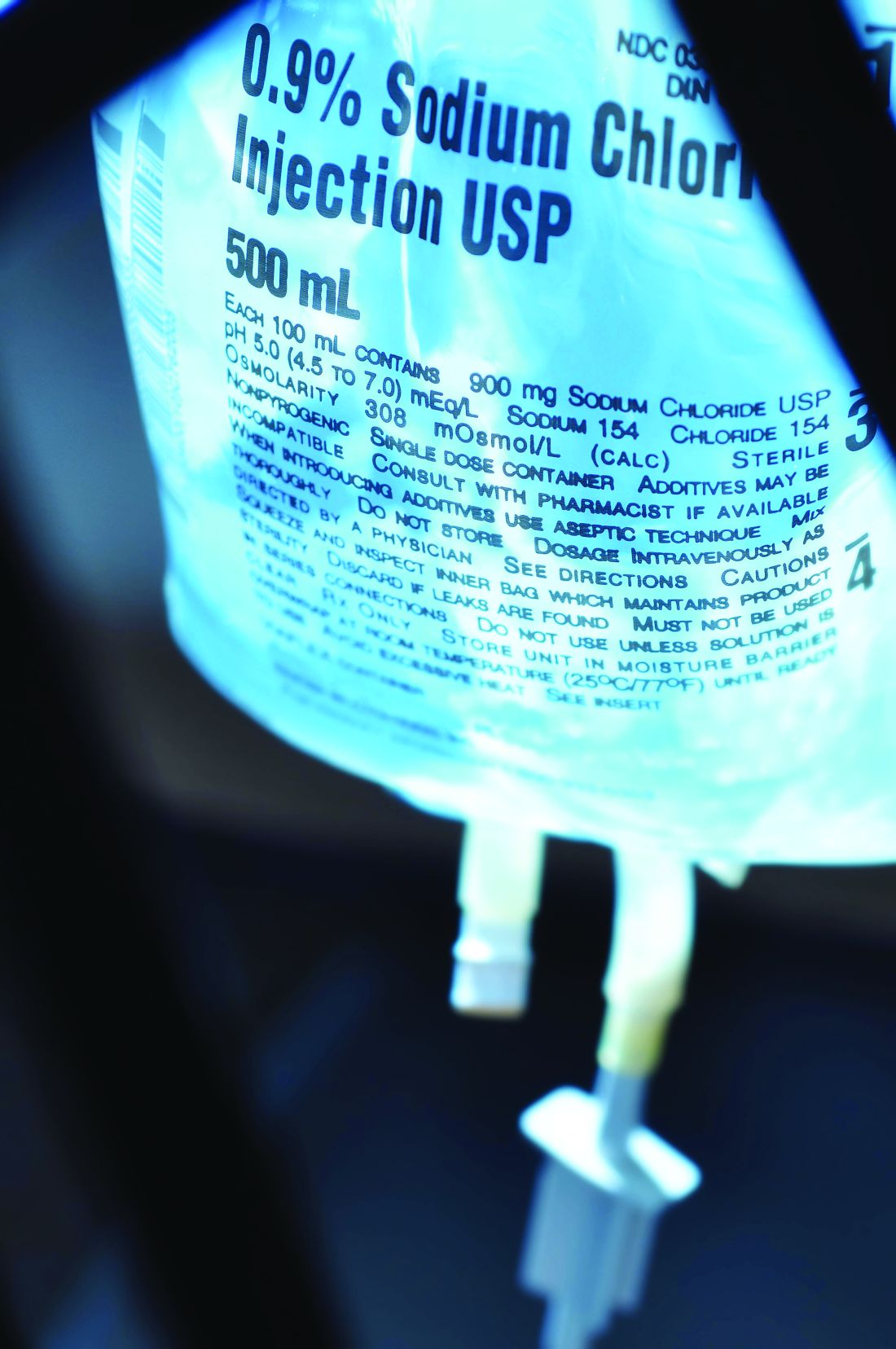

Restrictive fluids tied to kidney injury after major abdominal surgery

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Compared with a liberal fluid regimen, restricting fluids did not improve disability-free survival and was tied to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Major finding: Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% with restrictive fluids and 5.0% with liberal fluids.

Study details: International randomized trial of 3,000 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Disclosures: Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

Source: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601

Even a year of increased water intake did not change CKD course

Coaching adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) to increase water intake did not significantly slow decline in kidney function, results of a randomized clinical trial show.

Compared with coaching to maintain water intake, coaching to increase water intake did in fact increase water intake but did not prevent a decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over 1 year, according to findings of the study, which was published in JAMA..

However, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically important difference in this primary endpoint, and certain secondary endpoints did suggest a favorable effect of the intervention, according to William F. Clark, MD, of the London (Ontario) Health Sciences Centre and his coauthors.

“The increased water intake achieved in this trial was sufficient to lower vasopressin secretion, as assessed by plasma copeptin concentrations,” Dr. Clark and his colleagues said in their report

An increasing number of studies suggest that drinking water may benefit the kidneys. In some human studies, water intake was associated with reduced risk of kidney stones and better kidney function.

However, it remains unknown whether increasing water intake would benefit patients with CKD. To evaluate this question, Dr. Clark and colleagues initiated CKD WIT (Chronic Kidney Disease Water Intake Trial), a randomized clinical trial conducted in 9 centers in Ontario.

The study included 631 patients with stage 3 CKD and a 24-hour urine volume below 3 L. Patients randomized to the hydration group were coached to increase water intake gradually to 1-1.5 L/day for 1 year, while those randomized to the control group were coached to maintain their usual water intake.

Patients in the hydration group were also given reusable drinking containers and 20 vouchers per month redeemable for 1.5 L of bottled water, investigators reported.

Urine volume did significantly increase in the hydration group versus controls, by 0.6 L per day (P less than .001). However, change in eGFR – the primary outcome – was not significantly different between groups. Mean change in eGFR was –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in patients coached to drink more water and –1.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in those coached to maintain water intake (P = .74).

Some secondary outcome measures demonstrated significant differences in favor of the hydration group. Plasma copeptin and creatinine clearance both showed significant differences in favor of the hydration group. In contrast, there were no significant differences between intervention arms in urine albumin or quality of health, according to analyses of secondary outcomes described in the study report.

There are several ways to interpret the finding that drinking more water had no effect on eGFR, investigators said. Increasing water intake may simply not be protective against kidney function decline. Perhaps follow-up longer than 1 year would be needed to see an effect, or perhaps there was an effect, but the study was underpowered to detect it.

It could also be that a greater volume of water would be needed to demonstrate a protective effect for the kidneys. Despite the coaching efforts of dietitians and research assistants, the mean urine volume increase in the hydration group relative to the control group was just 0.6 liter per day, or 2.4 cups.

“This highlights how difficult it would be to achieve a large sustained increase in water intake in routine practice,” Dr. Clark and colleagues said in their report.

Dr. Clark reported disclosures related to Danone Research. Thermo Fisher Scientific provided instrumentation, assay reagent, and disposables used in the study.

SOURCE: Clark WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1870-9.

Coaching adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) to increase water intake did not significantly slow decline in kidney function, results of a randomized clinical trial show.

Compared with coaching to maintain water intake, coaching to increase water intake did in fact increase water intake but did not prevent a decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over 1 year, according to findings of the study, which was published in JAMA..

However, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically important difference in this primary endpoint, and certain secondary endpoints did suggest a favorable effect of the intervention, according to William F. Clark, MD, of the London (Ontario) Health Sciences Centre and his coauthors.

“The increased water intake achieved in this trial was sufficient to lower vasopressin secretion, as assessed by plasma copeptin concentrations,” Dr. Clark and his colleagues said in their report

An increasing number of studies suggest that drinking water may benefit the kidneys. In some human studies, water intake was associated with reduced risk of kidney stones and better kidney function.

However, it remains unknown whether increasing water intake would benefit patients with CKD. To evaluate this question, Dr. Clark and colleagues initiated CKD WIT (Chronic Kidney Disease Water Intake Trial), a randomized clinical trial conducted in 9 centers in Ontario.

The study included 631 patients with stage 3 CKD and a 24-hour urine volume below 3 L. Patients randomized to the hydration group were coached to increase water intake gradually to 1-1.5 L/day for 1 year, while those randomized to the control group were coached to maintain their usual water intake.

Patients in the hydration group were also given reusable drinking containers and 20 vouchers per month redeemable for 1.5 L of bottled water, investigators reported.

Urine volume did significantly increase in the hydration group versus controls, by 0.6 L per day (P less than .001). However, change in eGFR – the primary outcome – was not significantly different between groups. Mean change in eGFR was –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in patients coached to drink more water and –1.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in those coached to maintain water intake (P = .74).

Some secondary outcome measures demonstrated significant differences in favor of the hydration group. Plasma copeptin and creatinine clearance both showed significant differences in favor of the hydration group. In contrast, there were no significant differences between intervention arms in urine albumin or quality of health, according to analyses of secondary outcomes described in the study report.

There are several ways to interpret the finding that drinking more water had no effect on eGFR, investigators said. Increasing water intake may simply not be protective against kidney function decline. Perhaps follow-up longer than 1 year would be needed to see an effect, or perhaps there was an effect, but the study was underpowered to detect it.

It could also be that a greater volume of water would be needed to demonstrate a protective effect for the kidneys. Despite the coaching efforts of dietitians and research assistants, the mean urine volume increase in the hydration group relative to the control group was just 0.6 liter per day, or 2.4 cups.

“This highlights how difficult it would be to achieve a large sustained increase in water intake in routine practice,” Dr. Clark and colleagues said in their report.

Dr. Clark reported disclosures related to Danone Research. Thermo Fisher Scientific provided instrumentation, assay reagent, and disposables used in the study.

SOURCE: Clark WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1870-9.

Coaching adults with stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD) to increase water intake did not significantly slow decline in kidney function, results of a randomized clinical trial show.

Compared with coaching to maintain water intake, coaching to increase water intake did in fact increase water intake but did not prevent a decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over 1 year, according to findings of the study, which was published in JAMA..

However, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically important difference in this primary endpoint, and certain secondary endpoints did suggest a favorable effect of the intervention, according to William F. Clark, MD, of the London (Ontario) Health Sciences Centre and his coauthors.

“The increased water intake achieved in this trial was sufficient to lower vasopressin secretion, as assessed by plasma copeptin concentrations,” Dr. Clark and his colleagues said in their report

An increasing number of studies suggest that drinking water may benefit the kidneys. In some human studies, water intake was associated with reduced risk of kidney stones and better kidney function.

However, it remains unknown whether increasing water intake would benefit patients with CKD. To evaluate this question, Dr. Clark and colleagues initiated CKD WIT (Chronic Kidney Disease Water Intake Trial), a randomized clinical trial conducted in 9 centers in Ontario.

The study included 631 patients with stage 3 CKD and a 24-hour urine volume below 3 L. Patients randomized to the hydration group were coached to increase water intake gradually to 1-1.5 L/day for 1 year, while those randomized to the control group were coached to maintain their usual water intake.

Patients in the hydration group were also given reusable drinking containers and 20 vouchers per month redeemable for 1.5 L of bottled water, investigators reported.

Urine volume did significantly increase in the hydration group versus controls, by 0.6 L per day (P less than .001). However, change in eGFR – the primary outcome – was not significantly different between groups. Mean change in eGFR was –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in patients coached to drink more water and –1.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in those coached to maintain water intake (P = .74).

Some secondary outcome measures demonstrated significant differences in favor of the hydration group. Plasma copeptin and creatinine clearance both showed significant differences in favor of the hydration group. In contrast, there were no significant differences between intervention arms in urine albumin or quality of health, according to analyses of secondary outcomes described in the study report.

There are several ways to interpret the finding that drinking more water had no effect on eGFR, investigators said. Increasing water intake may simply not be protective against kidney function decline. Perhaps follow-up longer than 1 year would be needed to see an effect, or perhaps there was an effect, but the study was underpowered to detect it.

It could also be that a greater volume of water would be needed to demonstrate a protective effect for the kidneys. Despite the coaching efforts of dietitians and research assistants, the mean urine volume increase in the hydration group relative to the control group was just 0.6 liter per day, or 2.4 cups.

“This highlights how difficult it would be to achieve a large sustained increase in water intake in routine practice,” Dr. Clark and colleagues said in their report.

Dr. Clark reported disclosures related to Danone Research. Thermo Fisher Scientific provided instrumentation, assay reagent, and disposables used in the study.

SOURCE: Clark WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1870-9.

Key clinical point: Adults with CKD were coached to increase water intake, but that intervention did not appear to slow their decline in kidney function.

Major finding: The 1-year change in eGFR was –2.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in patients coached to drink more water and –1.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in those coached to maintain water intake; the difference was not significant.

Study details: The CKD WIT (Chronic Kidney Disease Water Intake Trial), a randomized clinical trial was conducted in 9 centers in Ontario, Canada, from 2013 until 2017 and included 631 patients with stage 3 CKD and a 24-hour urine volume below 3.0 L.

Disclosures: Authors reported disclosures related to Danone Research and the ISN/Danone Hydration for Kidney Health Research Initiative. Thermo Fisher Scientific provided instrumentation, assay reagent, and disposables used in the study.

Source: Clark WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1870-9.

MDedge Daily News: How to handle opioid constipation

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

An unusual complication of peritoneal dialysis

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

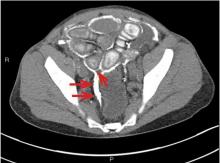

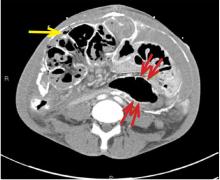

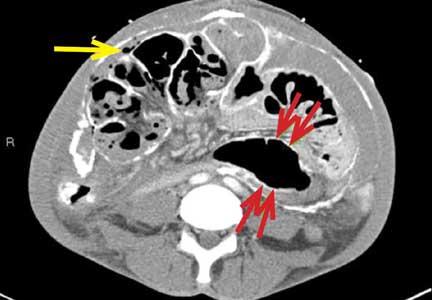

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

Cardiorenal syndrome

To the Editor: I read with interest the thoughtful review of cardiorenal syndrome by Drs. Thind, Loehrke, and Wilt1 and the accompanying editorial by Dr. Grodin.2 These articles certainly add to our growing knowledge of the syndrome and the importance of treating volume overload in these complex patients.

Indeed, we and others have stressed the primary importance of renal dysfunction in patients with volume overload and acute decompensated heart failure.3,4 We have learned that even small rises in serum creatinine predict poor outcomes in these patients. And even if the serum creatinine level comes back down during hospitalization, acute kidney injury (AKI) is still associated with risk.5

Nevertheless, clinicians remain frustrated with the practical management of patients with volume overload and worsening AKI. When faced with a rising serum creatinine level in a patient being treated for decompensated heart failure with signs or symptoms of volume overload, I suggest the following:

Perform careful bedside and chart review searching for evidence of AKI related to causes other than cardiorenal syndrome. Ask whether the rise in serum creatinine could be caused by new obstruction (eg, urinary retention, upper urinary tract obstruction), a nephrotoxin (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), a primary tubulointerstitial or glomerular process (eg, drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis, acute glomerulonephritis), acute tubular necrosis, or a new hemodynamic event threatening renal perfusion (eg, hypotension, a new arrhythmia). It is often best to arrive at a diagnosis of AKI due to cardiorenal dysfunction by exclusion, much like the working definitions of hepatorenal syndrome.6 This requires review of the urine sediment (looking for evidence of granular casts of acute tubular necrosis, or evidence of glomerulonephritis or interstitial nephritis), electronic medical record, vital signs, telemetry, and perhaps renal ultrasonography.

In the absence of frank evidence of “overdiuresis” such as worsening hypernatremia, with dropping blood pressure, clinical hypoperfusion, and contraction alkalosis, avoid the temptation to suspend diuretics. Alternatively, an increase in diuretic dose, or addition of a distal diuretic (ie, metolazone) may be needed to address persistent renal venous congestion as the cause of the AKI.3 In this situation, be sure to monitor electrolytes, volume status, and renal function closely while diuretic treatment is augmented. In many such cases, the serum creatinine may actually start to decrease after a more robust diuresis is generated. In these patients, it may also be prudent to temporarily suspend antagonists of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, although this remains controversial.

Management of such patients should be done collaboratively with cardiologists well versed in the treatment of cardiorenal syndrome. It may be possible that the worsening renal function in these patients represents important changes in cardiac rhythm or function (eg, low cardiac output state, new or worsening valvular disease, ongoing myocardial ischemia, cardiac tamponade, uncontrolled bradycardia or tachyarrythmia). Interventions aimed at reversing such perturbations could be the most important steps in improving cardiorenal function and reversing AKI.

- Thind GS, Loehrke M, Wilt JL. Acute cardiorenal syndrome: mechanisms and clinical implications. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(3):231–239. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17019

- Grodin JL. Hemodynamically, the kidney is at the heart of cardiorenal syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(3):240–242. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17126

- Freda BJ, Slawsky M, Mallidi J, Braden GL. Decongestive treatment of acute decompensated heart failure: cardiorenal implications of ultrafiltration and diuretics. Am J Kid Dis 2011; 58(6):1005–1017. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.07.023

- Tang WH, Kitai T. Intrarenal blood flow: a window into the congestive kidney failure phenotype of heart failure? JACC Heart Fail 2016; 4(8):683–686. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2016.05.009

- Freda BJ, Knee AB, Braden GL, Visintainer PF, Thakaer CV. Effect of transient and sustained acute kidney injury on readmissions in acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2017; 119(11):1809–1814. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.044

- Bucsics T, Krones E. Renal dysfunction in cirrhosis: acute kidney injury and the hepatorenal syndrome. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017; 5(2):127–137. doi:10.1093/gastro/gox009

To the Editor: I read with interest the thoughtful review of cardiorenal syndrome by Drs. Thind, Loehrke, and Wilt1 and the accompanying editorial by Dr. Grodin.2 These articles certainly add to our growing knowledge of the syndrome and the importance of treating volume overload in these complex patients.

Indeed, we and others have stressed the primary importance of renal dysfunction in patients with volume overload and acute decompensated heart failure.3,4 We have learned that even small rises in serum creatinine predict poor outcomes in these patients. And even if the serum creatinine level comes back down during hospitalization, acute kidney injury (AKI) is still associated with risk.5