User login

Age-related cognitive decline not inevitable?

Investigators found that despite the presence of neuropathologies associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), many centenarians maintained high levels of cognitive performance.

“Cognitive decline is not inevitable,” senior author Henne Holstege, PhD, assistant professor, Amsterdam Alzheimer Center and Clinical Genetics, Amsterdam University Medical Center, said in an interview.

“At 100 years or older, high levels of cognitive performance can be maintained for several years, even when individuals are exposed to risk factors associated with cognitive decline,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 15 in JAMA Network Open.

Escaping cognitive decline

Dr. Holstege said her interest in researching aging and cognitive health was inspired by the “fascinating” story of Hendrikje van Andel-Schipper, who died at age 115 in 2015 “completely cognitively healthy.” Her mother, who died at age 100, also was cognitively intact at the end of her life.

“I wanted to know how it is possible that some people can completely escape all aspects of cognitive decline while reaching extreme ages,” Dr. Holstege said.

To discover the secret to cognitive health in the oldest old, Dr. Holstege initiated the 100-Plus Study, which involved a cohort of healthy centenarians.

The investigators conducted extensive neuropsychological testing and collected blood and fecal samples to examine “the myriad factors that influence physical health, including genetics, neuropathology, blood markers, and the gut microbiome, to explore the molecular and neuropsychologic constellations associated with the escape from cognitive decline.”

The goal of the research was to investigate “to what extent centenarians were able to maintain their cognitive health after study inclusion, and to what extent this was associated with genetic, physical, or neuropathological features,” she said.

The study included 330 centenarians who completed one or more neuropsychological assessments. Neuropathologic studies were available for 44 participants.

To assess baseline cognitive performance, the researchers administered a wide array of neurocognitive tests, as well as the Mini–Mental State Examination, from which mean z scores for cognitive domains were calculated.

Additional factors in the analysis included sex, age, APOE status, cognitive reserve, physical health, and whether participants lived independently.

At autopsy, amyloid-beta (A-beta) level, the level of intracellular accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and the neuritic plaque (NP) load were assessed.

Resilience and cognitive reserve

At baseline, the median age of the centenarians (n = 330, 72.4% women) was 100.5 years (interquartile range, 100.2-101.7). A little over half (56.7%) lived independently, and the majority had good vision (65%) and hearing (56.4%). Most (78.8%) were able to walk independently, and 37.9% had achieved the highest International Standard Classification of Education level of postsecondary education.

The researchers found “varying degrees of neuropathology” in the brains of the 44 donors, including A-beta, NFT, and NPs.

The duration of follow-up in analyzing cognitive trajectories ranged from 0 to 4 years (median, 1.6 years).

Assessments of all cognitive domains showed no decline, with the exception of a “slight” decrement in memory function (beta −.10 SD per year; 95% confidence interval, –.14 to –.05 SD; P < .001).

Cognitive performance was associated with factors of physical health or cognitive reserve, for example, greater independence in performing activities of daily living, as assessed by the Barthel index (beta .37 SD per year; 95% CI, .24-.49; P < .001), or higher educational level (beta .41 SD per year; 95% CI, .29-.53; P < .001).

Despite findings of neuropathologic “hallmarks” of AD post mortem in the brains of the centenarians, these were not associated with cognitive performance or rate of decline.

APOE epsilon-4 or an APOE epsilon-3 alleles also were not significantly associated with cognitive performance or decline, suggesting that the “effects of APOE alleles are exerted before the age of 100 years,” the authors noted.

“Our findings suggest that after reaching age 100 years, cognitive performance remains relatively stable during ensuing years. Therefore, these centenarians might be resilient or resistant against different risk factors of cognitive decline,” the authors wrote. They also speculate that resilience may be attributable to greater cognitive reserve.

“Our preliminary data indicate that approximately 60% of the chance to reach 100 years old is heritable. Therefore, to get a better understanding of which genetic factors associate with the prolonged maintenance of cognitive health, we are looking into which genetic variants occur more commonly in centenarians compared to younger individuals,” said Dr. Holstege.

“Of course, more research needs to be performed to get a better understanding of how such genetic elements might sustain brain health,” she added.

A ‘landmark study’

Commenting on the study in an interview, Thomas Perls, MD, MPH, professor of medicine, Boston University, called it a “landmark” study in research on exceptional longevity in humans.

Dr. Perls, the author of an accompanying editorial, noted that “one cannot absolutely assume a certain level or disability or risk for disease just because a person has achieved extreme age – in fact, if anything, their ability to achieve much older ages likely indicates that they have resistance or resilience to aging-related problems.”

Understanding the mechanism of the resilience could lead to treatment or prevention of AD, said Dr. Perls, who was not involved in the research.

“People have to be careful about ageist myths and attitudes and not have the ageist idea that the older you get, the sicker you get, because many individuals disprove that,” he cautioned.

The study was supported by Stichting Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting Vumc Fonds. Research from the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience. Dr. Holstege and Dr. Perls reported having no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that despite the presence of neuropathologies associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), many centenarians maintained high levels of cognitive performance.

“Cognitive decline is not inevitable,” senior author Henne Holstege, PhD, assistant professor, Amsterdam Alzheimer Center and Clinical Genetics, Amsterdam University Medical Center, said in an interview.

“At 100 years or older, high levels of cognitive performance can be maintained for several years, even when individuals are exposed to risk factors associated with cognitive decline,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 15 in JAMA Network Open.

Escaping cognitive decline

Dr. Holstege said her interest in researching aging and cognitive health was inspired by the “fascinating” story of Hendrikje van Andel-Schipper, who died at age 115 in 2015 “completely cognitively healthy.” Her mother, who died at age 100, also was cognitively intact at the end of her life.

“I wanted to know how it is possible that some people can completely escape all aspects of cognitive decline while reaching extreme ages,” Dr. Holstege said.

To discover the secret to cognitive health in the oldest old, Dr. Holstege initiated the 100-Plus Study, which involved a cohort of healthy centenarians.

The investigators conducted extensive neuropsychological testing and collected blood and fecal samples to examine “the myriad factors that influence physical health, including genetics, neuropathology, blood markers, and the gut microbiome, to explore the molecular and neuropsychologic constellations associated with the escape from cognitive decline.”

The goal of the research was to investigate “to what extent centenarians were able to maintain their cognitive health after study inclusion, and to what extent this was associated with genetic, physical, or neuropathological features,” she said.

The study included 330 centenarians who completed one or more neuropsychological assessments. Neuropathologic studies were available for 44 participants.

To assess baseline cognitive performance, the researchers administered a wide array of neurocognitive tests, as well as the Mini–Mental State Examination, from which mean z scores for cognitive domains were calculated.

Additional factors in the analysis included sex, age, APOE status, cognitive reserve, physical health, and whether participants lived independently.

At autopsy, amyloid-beta (A-beta) level, the level of intracellular accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and the neuritic plaque (NP) load were assessed.

Resilience and cognitive reserve

At baseline, the median age of the centenarians (n = 330, 72.4% women) was 100.5 years (interquartile range, 100.2-101.7). A little over half (56.7%) lived independently, and the majority had good vision (65%) and hearing (56.4%). Most (78.8%) were able to walk independently, and 37.9% had achieved the highest International Standard Classification of Education level of postsecondary education.

The researchers found “varying degrees of neuropathology” in the brains of the 44 donors, including A-beta, NFT, and NPs.

The duration of follow-up in analyzing cognitive trajectories ranged from 0 to 4 years (median, 1.6 years).

Assessments of all cognitive domains showed no decline, with the exception of a “slight” decrement in memory function (beta −.10 SD per year; 95% confidence interval, –.14 to –.05 SD; P < .001).

Cognitive performance was associated with factors of physical health or cognitive reserve, for example, greater independence in performing activities of daily living, as assessed by the Barthel index (beta .37 SD per year; 95% CI, .24-.49; P < .001), or higher educational level (beta .41 SD per year; 95% CI, .29-.53; P < .001).

Despite findings of neuropathologic “hallmarks” of AD post mortem in the brains of the centenarians, these were not associated with cognitive performance or rate of decline.

APOE epsilon-4 or an APOE epsilon-3 alleles also were not significantly associated with cognitive performance or decline, suggesting that the “effects of APOE alleles are exerted before the age of 100 years,” the authors noted.

“Our findings suggest that after reaching age 100 years, cognitive performance remains relatively stable during ensuing years. Therefore, these centenarians might be resilient or resistant against different risk factors of cognitive decline,” the authors wrote. They also speculate that resilience may be attributable to greater cognitive reserve.

“Our preliminary data indicate that approximately 60% of the chance to reach 100 years old is heritable. Therefore, to get a better understanding of which genetic factors associate with the prolonged maintenance of cognitive health, we are looking into which genetic variants occur more commonly in centenarians compared to younger individuals,” said Dr. Holstege.

“Of course, more research needs to be performed to get a better understanding of how such genetic elements might sustain brain health,” she added.

A ‘landmark study’

Commenting on the study in an interview, Thomas Perls, MD, MPH, professor of medicine, Boston University, called it a “landmark” study in research on exceptional longevity in humans.

Dr. Perls, the author of an accompanying editorial, noted that “one cannot absolutely assume a certain level or disability or risk for disease just because a person has achieved extreme age – in fact, if anything, their ability to achieve much older ages likely indicates that they have resistance or resilience to aging-related problems.”

Understanding the mechanism of the resilience could lead to treatment or prevention of AD, said Dr. Perls, who was not involved in the research.

“People have to be careful about ageist myths and attitudes and not have the ageist idea that the older you get, the sicker you get, because many individuals disprove that,” he cautioned.

The study was supported by Stichting Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting Vumc Fonds. Research from the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience. Dr. Holstege and Dr. Perls reported having no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that despite the presence of neuropathologies associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), many centenarians maintained high levels of cognitive performance.

“Cognitive decline is not inevitable,” senior author Henne Holstege, PhD, assistant professor, Amsterdam Alzheimer Center and Clinical Genetics, Amsterdam University Medical Center, said in an interview.

“At 100 years or older, high levels of cognitive performance can be maintained for several years, even when individuals are exposed to risk factors associated with cognitive decline,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 15 in JAMA Network Open.

Escaping cognitive decline

Dr. Holstege said her interest in researching aging and cognitive health was inspired by the “fascinating” story of Hendrikje van Andel-Schipper, who died at age 115 in 2015 “completely cognitively healthy.” Her mother, who died at age 100, also was cognitively intact at the end of her life.

“I wanted to know how it is possible that some people can completely escape all aspects of cognitive decline while reaching extreme ages,” Dr. Holstege said.

To discover the secret to cognitive health in the oldest old, Dr. Holstege initiated the 100-Plus Study, which involved a cohort of healthy centenarians.

The investigators conducted extensive neuropsychological testing and collected blood and fecal samples to examine “the myriad factors that influence physical health, including genetics, neuropathology, blood markers, and the gut microbiome, to explore the molecular and neuropsychologic constellations associated with the escape from cognitive decline.”

The goal of the research was to investigate “to what extent centenarians were able to maintain their cognitive health after study inclusion, and to what extent this was associated with genetic, physical, or neuropathological features,” she said.

The study included 330 centenarians who completed one or more neuropsychological assessments. Neuropathologic studies were available for 44 participants.

To assess baseline cognitive performance, the researchers administered a wide array of neurocognitive tests, as well as the Mini–Mental State Examination, from which mean z scores for cognitive domains were calculated.

Additional factors in the analysis included sex, age, APOE status, cognitive reserve, physical health, and whether participants lived independently.

At autopsy, amyloid-beta (A-beta) level, the level of intracellular accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and the neuritic plaque (NP) load were assessed.

Resilience and cognitive reserve

At baseline, the median age of the centenarians (n = 330, 72.4% women) was 100.5 years (interquartile range, 100.2-101.7). A little over half (56.7%) lived independently, and the majority had good vision (65%) and hearing (56.4%). Most (78.8%) were able to walk independently, and 37.9% had achieved the highest International Standard Classification of Education level of postsecondary education.

The researchers found “varying degrees of neuropathology” in the brains of the 44 donors, including A-beta, NFT, and NPs.

The duration of follow-up in analyzing cognitive trajectories ranged from 0 to 4 years (median, 1.6 years).

Assessments of all cognitive domains showed no decline, with the exception of a “slight” decrement in memory function (beta −.10 SD per year; 95% confidence interval, –.14 to –.05 SD; P < .001).

Cognitive performance was associated with factors of physical health or cognitive reserve, for example, greater independence in performing activities of daily living, as assessed by the Barthel index (beta .37 SD per year; 95% CI, .24-.49; P < .001), or higher educational level (beta .41 SD per year; 95% CI, .29-.53; P < .001).

Despite findings of neuropathologic “hallmarks” of AD post mortem in the brains of the centenarians, these were not associated with cognitive performance or rate of decline.

APOE epsilon-4 or an APOE epsilon-3 alleles also were not significantly associated with cognitive performance or decline, suggesting that the “effects of APOE alleles are exerted before the age of 100 years,” the authors noted.

“Our findings suggest that after reaching age 100 years, cognitive performance remains relatively stable during ensuing years. Therefore, these centenarians might be resilient or resistant against different risk factors of cognitive decline,” the authors wrote. They also speculate that resilience may be attributable to greater cognitive reserve.

“Our preliminary data indicate that approximately 60% of the chance to reach 100 years old is heritable. Therefore, to get a better understanding of which genetic factors associate with the prolonged maintenance of cognitive health, we are looking into which genetic variants occur more commonly in centenarians compared to younger individuals,” said Dr. Holstege.

“Of course, more research needs to be performed to get a better understanding of how such genetic elements might sustain brain health,” she added.

A ‘landmark study’

Commenting on the study in an interview, Thomas Perls, MD, MPH, professor of medicine, Boston University, called it a “landmark” study in research on exceptional longevity in humans.

Dr. Perls, the author of an accompanying editorial, noted that “one cannot absolutely assume a certain level or disability or risk for disease just because a person has achieved extreme age – in fact, if anything, their ability to achieve much older ages likely indicates that they have resistance or resilience to aging-related problems.”

Understanding the mechanism of the resilience could lead to treatment or prevention of AD, said Dr. Perls, who was not involved in the research.

“People have to be careful about ageist myths and attitudes and not have the ageist idea that the older you get, the sicker you get, because many individuals disprove that,” he cautioned.

The study was supported by Stichting Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting Vumc Fonds. Research from the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience. Dr. Holstege and Dr. Perls reported having no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Green light puts the stop on migraine

, according to results of a small study from the University of Arizona, Tucson.

“This is the first clinical study to evaluate green light exposure as a potential preventive therapy for patients with migraine, “ senior author Mohab M. Ibrahim, MD, PhD, said in a press release. “Now I have another tool in my toolbox to treat one of the most difficult neurologic conditions – migraine.”

“Given the safety, affordability, and efficacy of green light exposure, there is merit to conduct a larger study,” he and coauthors from the university wrote in their paper.

The study included 29 adult patients (average age 52.2 years), 22 with chronic migraine and the rest with episodic migraine who were recruited from the University of Arizona/Banner Medical Center chronic pain clinic. To be included, patients had to meet the International Headache Society diagnostic criteria for chronic or episodic migraine, have an average headache pain intensity of 5 out of 10 or greater on the numeric pain scale (NPS) over the 10 weeks prior to enrolling in the study, and be dissatisfied with their current migraine therapy.

The patients were free to start, continue, or discontinue any other migraine treatments as recommended by their physicians as long as this was reported to the study team.

White versus green

The one-way crossover design involved exposure to 10 weeks of white light emitting diodes, for 1-2 hours per day, followed by a 2-week washout period and then 10 weeks’ exposure to green light emitting diodes (GLED) for the same daily duration. The protocol involved use of a light strip emitting an intensity of between 4 and 100 lux measured at approximately 2 m and 1 m from a lux meter.

Patients were instructed to use the light in a dark room, without falling asleep, and to participate in activities that did not require external light sources, such as listening to music, reading books, doing exercises, or engaging in similar activities. The daily minimum exposure of 1 hour, up to a maximum of 2 hours, was to be completed in one sitting.

The primary outcome measure was the number of headache days per month, defined as days with moderate to severe headache pain for at least 4 hours. Secondary outcomes included perceived reduction in duration and intensity of the headache phase of the migraine episodes assessed every 2 weeks with the NPS, improved ability to fall and stay asleep, improved ability to perform work and daily activity, improved quality of life, and reduction of pain medications.

The researchers found that when the patients with chronic migraine and episodic migraine were examined as separate groups, white light exposure did not significantly reduce the number of headache days per month, but when the chronic migraine and episodic migraine groups were combined there was a significant reduction from 18.2 to 16.5 headache days per month.

On the other hand, green light did result in significantly reduced headache days both in the separate (from 7.9 to 2.4 days in the episodic migraine group and 22.3 to 9.4 days in the chronic migraine group) and combined groups (from 18.4 to 7.4 days).

“While some improvement in secondary outcomes was observed with white light emitting diodes, more secondary outcomes with significantly greater magnitude including assessments of quality of life, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, Headache Impact Test-6, and Five-level version of the EuroQol five-dimensional survey without reported side effects were observed with green light emitting diodes,” the authors reported.

“The use of a nonpharmacological therapy such as green light can be of tremendous help to a variety of patients that either do not want to be on medications or do not respond to them,” coauthor Amol M. Patwardhan, MD, PhD, said in the press release. “The beauty of this approach is the lack of associated side effects. If at all, it appears to improve sleep and other quality of life measures,” said Dr. Patwardhan, associate professor and vice chair of research in the University of Arizona’s department of anesthesiology.

Better than white light

Asked to comment on the findings, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said research has shown for some time that exposure to green light has beneficial effects in migraine patients. This study, although small, does indicate that green light is more beneficial than is white light and reduces headache days and intensity. “I believe patients would be willing to spend 1-2 hours a day in green light to reduce and improve their migraine with few side effects. A larger randomized trial should be done,” he said.

The study was funded by support from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (to Dr. Ibrahim), the Comprehensive Chronic Pain and Addiction Center–University of Arizona, and the University of Arizona CHiLLI initiative. Dr. Ibrahim and one coauthor have a patent pending through the University of Arizona for use of green light therapy for the management of chronic pain. Dr. Rapoport is a former president of the International Headache Society. He is an editor of Headache and CNS Drugs, and Editor-in-Chief of Neurology Reviews. He reviews for many peer-reviewed journals such as Cephalalgia, Neurology, New England Journal of Medicine, and Headache.

, according to results of a small study from the University of Arizona, Tucson.

“This is the first clinical study to evaluate green light exposure as a potential preventive therapy for patients with migraine, “ senior author Mohab M. Ibrahim, MD, PhD, said in a press release. “Now I have another tool in my toolbox to treat one of the most difficult neurologic conditions – migraine.”

“Given the safety, affordability, and efficacy of green light exposure, there is merit to conduct a larger study,” he and coauthors from the university wrote in their paper.

The study included 29 adult patients (average age 52.2 years), 22 with chronic migraine and the rest with episodic migraine who were recruited from the University of Arizona/Banner Medical Center chronic pain clinic. To be included, patients had to meet the International Headache Society diagnostic criteria for chronic or episodic migraine, have an average headache pain intensity of 5 out of 10 or greater on the numeric pain scale (NPS) over the 10 weeks prior to enrolling in the study, and be dissatisfied with their current migraine therapy.

The patients were free to start, continue, or discontinue any other migraine treatments as recommended by their physicians as long as this was reported to the study team.

White versus green

The one-way crossover design involved exposure to 10 weeks of white light emitting diodes, for 1-2 hours per day, followed by a 2-week washout period and then 10 weeks’ exposure to green light emitting diodes (GLED) for the same daily duration. The protocol involved use of a light strip emitting an intensity of between 4 and 100 lux measured at approximately 2 m and 1 m from a lux meter.

Patients were instructed to use the light in a dark room, without falling asleep, and to participate in activities that did not require external light sources, such as listening to music, reading books, doing exercises, or engaging in similar activities. The daily minimum exposure of 1 hour, up to a maximum of 2 hours, was to be completed in one sitting.

The primary outcome measure was the number of headache days per month, defined as days with moderate to severe headache pain for at least 4 hours. Secondary outcomes included perceived reduction in duration and intensity of the headache phase of the migraine episodes assessed every 2 weeks with the NPS, improved ability to fall and stay asleep, improved ability to perform work and daily activity, improved quality of life, and reduction of pain medications.

The researchers found that when the patients with chronic migraine and episodic migraine were examined as separate groups, white light exposure did not significantly reduce the number of headache days per month, but when the chronic migraine and episodic migraine groups were combined there was a significant reduction from 18.2 to 16.5 headache days per month.

On the other hand, green light did result in significantly reduced headache days both in the separate (from 7.9 to 2.4 days in the episodic migraine group and 22.3 to 9.4 days in the chronic migraine group) and combined groups (from 18.4 to 7.4 days).

“While some improvement in secondary outcomes was observed with white light emitting diodes, more secondary outcomes with significantly greater magnitude including assessments of quality of life, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, Headache Impact Test-6, and Five-level version of the EuroQol five-dimensional survey without reported side effects were observed with green light emitting diodes,” the authors reported.

“The use of a nonpharmacological therapy such as green light can be of tremendous help to a variety of patients that either do not want to be on medications or do not respond to them,” coauthor Amol M. Patwardhan, MD, PhD, said in the press release. “The beauty of this approach is the lack of associated side effects. If at all, it appears to improve sleep and other quality of life measures,” said Dr. Patwardhan, associate professor and vice chair of research in the University of Arizona’s department of anesthesiology.

Better than white light

Asked to comment on the findings, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said research has shown for some time that exposure to green light has beneficial effects in migraine patients. This study, although small, does indicate that green light is more beneficial than is white light and reduces headache days and intensity. “I believe patients would be willing to spend 1-2 hours a day in green light to reduce and improve their migraine with few side effects. A larger randomized trial should be done,” he said.

The study was funded by support from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (to Dr. Ibrahim), the Comprehensive Chronic Pain and Addiction Center–University of Arizona, and the University of Arizona CHiLLI initiative. Dr. Ibrahim and one coauthor have a patent pending through the University of Arizona for use of green light therapy for the management of chronic pain. Dr. Rapoport is a former president of the International Headache Society. He is an editor of Headache and CNS Drugs, and Editor-in-Chief of Neurology Reviews. He reviews for many peer-reviewed journals such as Cephalalgia, Neurology, New England Journal of Medicine, and Headache.

, according to results of a small study from the University of Arizona, Tucson.

“This is the first clinical study to evaluate green light exposure as a potential preventive therapy for patients with migraine, “ senior author Mohab M. Ibrahim, MD, PhD, said in a press release. “Now I have another tool in my toolbox to treat one of the most difficult neurologic conditions – migraine.”

“Given the safety, affordability, and efficacy of green light exposure, there is merit to conduct a larger study,” he and coauthors from the university wrote in their paper.

The study included 29 adult patients (average age 52.2 years), 22 with chronic migraine and the rest with episodic migraine who were recruited from the University of Arizona/Banner Medical Center chronic pain clinic. To be included, patients had to meet the International Headache Society diagnostic criteria for chronic or episodic migraine, have an average headache pain intensity of 5 out of 10 or greater on the numeric pain scale (NPS) over the 10 weeks prior to enrolling in the study, and be dissatisfied with their current migraine therapy.

The patients were free to start, continue, or discontinue any other migraine treatments as recommended by their physicians as long as this was reported to the study team.

White versus green

The one-way crossover design involved exposure to 10 weeks of white light emitting diodes, for 1-2 hours per day, followed by a 2-week washout period and then 10 weeks’ exposure to green light emitting diodes (GLED) for the same daily duration. The protocol involved use of a light strip emitting an intensity of between 4 and 100 lux measured at approximately 2 m and 1 m from a lux meter.

Patients were instructed to use the light in a dark room, without falling asleep, and to participate in activities that did not require external light sources, such as listening to music, reading books, doing exercises, or engaging in similar activities. The daily minimum exposure of 1 hour, up to a maximum of 2 hours, was to be completed in one sitting.

The primary outcome measure was the number of headache days per month, defined as days with moderate to severe headache pain for at least 4 hours. Secondary outcomes included perceived reduction in duration and intensity of the headache phase of the migraine episodes assessed every 2 weeks with the NPS, improved ability to fall and stay asleep, improved ability to perform work and daily activity, improved quality of life, and reduction of pain medications.

The researchers found that when the patients with chronic migraine and episodic migraine were examined as separate groups, white light exposure did not significantly reduce the number of headache days per month, but when the chronic migraine and episodic migraine groups were combined there was a significant reduction from 18.2 to 16.5 headache days per month.

On the other hand, green light did result in significantly reduced headache days both in the separate (from 7.9 to 2.4 days in the episodic migraine group and 22.3 to 9.4 days in the chronic migraine group) and combined groups (from 18.4 to 7.4 days).

“While some improvement in secondary outcomes was observed with white light emitting diodes, more secondary outcomes with significantly greater magnitude including assessments of quality of life, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, Headache Impact Test-6, and Five-level version of the EuroQol five-dimensional survey without reported side effects were observed with green light emitting diodes,” the authors reported.

“The use of a nonpharmacological therapy such as green light can be of tremendous help to a variety of patients that either do not want to be on medications or do not respond to them,” coauthor Amol M. Patwardhan, MD, PhD, said in the press release. “The beauty of this approach is the lack of associated side effects. If at all, it appears to improve sleep and other quality of life measures,” said Dr. Patwardhan, associate professor and vice chair of research in the University of Arizona’s department of anesthesiology.

Better than white light

Asked to comment on the findings, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said research has shown for some time that exposure to green light has beneficial effects in migraine patients. This study, although small, does indicate that green light is more beneficial than is white light and reduces headache days and intensity. “I believe patients would be willing to spend 1-2 hours a day in green light to reduce and improve their migraine with few side effects. A larger randomized trial should be done,” he said.

The study was funded by support from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (to Dr. Ibrahim), the Comprehensive Chronic Pain and Addiction Center–University of Arizona, and the University of Arizona CHiLLI initiative. Dr. Ibrahim and one coauthor have a patent pending through the University of Arizona for use of green light therapy for the management of chronic pain. Dr. Rapoport is a former president of the International Headache Society. He is an editor of Headache and CNS Drugs, and Editor-in-Chief of Neurology Reviews. He reviews for many peer-reviewed journals such as Cephalalgia, Neurology, New England Journal of Medicine, and Headache.

FROM CEPHALALGIA

The Future of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Therapies (FULL)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, with recent estimates of around 1 million people living with MS in the US.1 In many countries, MS is a leading cause of disability among young adults, second only to trauma.2 Clinically, neurologic worsening (ie, disability) in MS can occur in the relapsing-remitting (RRMS) phase of disease due to incomplete recovery from neuroinflammatory relapses. However, in the 15% of patients with a progressive course from onset (PPMS), and in those with RRMS who transition to a secondary progressive phenotype (SPMS), neurologic worsening follows a slowly progressive pattern.3 A progressive disease course—either PPMS at onset or transitioning to SPMS—is the dominant factor affecting MS-related neurologic disability accumulation. In particular, epidemiologic studies have shown that, in the absence of transitioning to a progressive disease course, < 5% of individuals with MS will accumulate sufficient disability to necessitate use of a cane for ambulation.4-6 Therefore, developing disease modifying therapies (DMTs) that are highly effective at slowing or stopping the gradual accumulation of neurologic disability in progressive MS represent a critical unmet need.

Research into the development of DMTs for progressive MS has been hindered by a number of factors. In particular, the clinical definition and diagnosis of progressive MS has been an evolving concept. Diagnostic criteria for MS, which help facilitate the enrollment of appropriate subjects into clinical trials, have only recently clarified the current consensus definition for progressive MS—steadily increasing neurologic disability independent of clinical relapses. Looking back to the Schumacher criteria in 1965 and Poser criteria in 1983, it was acknowledged that neurologic symptoms in MS may follow a relapsing-remitting or progressive pattern, but little attempt was made to define progressive MS.7,8 The original McDonald criteria in 2001 defined diagnostic criteria for progressive MS.9 These criteria continued to evolve through subsequent revisions (eg, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] specific oligoclonal bands no longer are an absolute requirement), and only in the 2017 revision was it emphasized that disability progression must occur independent of clinical relapses, concordant with similar emphasis in the 2013 revision of MS clinical course definitions.3,10

The interpretation of prior clinical trials of DMT for progressive MS must consider this evolving clinical definition. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved mitoxantrone in 2000—making it the first DMT to carry an approved label for SPMS. While achieving significant clinical efficacy, it is clear from the details of the trial that the enrolled subjects had a high degree of inflammatory disease activity, which suggests that mitoxantrone treats neuroinflammation and not relapse-independent worsening. More recently, disparate results were seen in the anti-CD20 (rituximab, ocrelizumab) and S1P receptor modulator (fingolimod, siponimod) trials targeted at patients with primary and secondary progressive MS.11-14 Although there are differences between these therapies, they are more similar than not within the same therapeutic class. Taken together, these trials illustrate the critical impact the narrower inclusion/exclusion criteria (namely age and extent of inflammatory activity) had on attaining positive outcomes. Other considerations, such as confounding illness, also may impact trial recruitment and generalizability of findings.

The lack of known biological targets in progressive MS, which is a complex disease with an incompletely understood and heterogeneous pathology, also hinders DMT development. Decades of research has characterized multifocal central nervous system (CNS) lesions that exhibit features of demyelination, inflammation, reactive gliosis, axonal loss, and neuronal damage. Until recently, however, much of this research focused on the relapsing phase of disease, and so the understanding of the pathologic underpinnings of progressive disease has remained limited. Current areas of investigation encompass a broad range of pathological processes, such as microglial activation, meningeal lymphoid follicles, remyelination failure, vulnerability of chronically demyelinated axons, oxidative injury, iron accumulation, mitochondrial damage, and others. There is the added complication that the pathologic processes underlying progressive MS are superimposed on the CNS aging process. In particular, the transition to progressive MS and the rate of disability accumulation during progressive MS show strong correlation with age.6,15-17

Finally, DMT development for progressive MS also is hindered by the lack of specific surrogate and clinical outcome measures. Trials for relapsing MS have benefited greatly from the relatively straightforward assessment of clinical relapses and inflammatory disease activity on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). With the goal of developing DMTs that are highly effective at slowing or stopping the gradual accumulation of neurologic disability in progressive MS, which by definition occurs independent of clinical relapses, these measures are not directly relevant. The longitudinal clinical disability outcome measures change at a slower rate than in early, relapsing disease. The use of standardized scales (eg, the Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]), lower limb function, upper limb function, cognition, or a combination is a subject of ongoing debate. For example, the ASCEND and IMPACT trials (placebo-controlled trials for SPMS with natalizumab and interferon β-1a, respectively) showed no significant impact in EDSS progression—but in both of these trials, the 9-hole peg test (9-HPT), a performance measure for upper limb function, showed significant improvement.10,18 Particularly in those with an EDSS of > 6.5, who are unlikely to have measurable EDSS progression, functional tests such as the 9-HPT or timed 25-foot walk may be more sensitive as measures for disability progression.11 MRI measures of brain atrophy is the current gold standard surrogate outcome for clinical trials in progressive MS, but others that may warrant consideration include optical coherence tomography (OCT) or CSF markers of axonal degeneration.

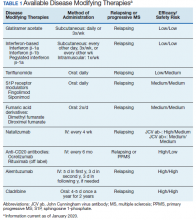

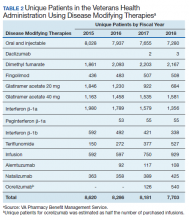

DMT for Progressive MS

Current diagnostic nomenclature separates patients with active (superimposed clinical and/or radiographic relapses) from those with inactive disease.3,12 Relapsing forms of MS include all RRMS and those with SPMS with superimposed relapses (ie, active SPMS). Following this paradigm shift, the FDA changed the indication for already approved DMT from RRMS to relapsing forms of MS. Below is a discussion of DMT that specifically use the term SPMS and PPMS in the indication, where phase 3 trial data for progressive MS is available.

In 2019, the FDA approved the first oral medication (siponimod) for active SPMS. Subsequently, updates to the labels of the older DMT expanded to include active SPMS. Until 2019, the only FDA approved medication for SPMS was mitoxantrone, and use of this medication was limited due to unfavorable adverse effects (AEs). No medications had obtained FDA approval for inactive SPMS to this point, which represented an unmet need for a considerable number of patients.

Mitoxantrone became the first DMT approved for use in SPMS in 2000 following early trials that showed reductions in EDSS worsening, change in ambulation index, reduced number of treated relapses, and prolonged time to first treated relapse. However, as with some of the other positive trials in progressive MS, it is difficult to discern the impact of suppression of relapses as opposed to direct impact on progressive pathophysiology. Within the placebo arm, for example, there were 129 relapses among the 64 subjects, which suggests that these cases had particularly active disease or were in the early stages of SPMS.13 Furthermore, the use of this medication was limited due to concerns of cardiotoxicity and hematologic malignancy as serious AEs.

The trials of interferon β-1b illustrate the same difficulty of isolating possible benefits in disease progression from disability accumulated from relapses. The first interferon β-1b trial for SPMS, was conducted in Europe using fingolimod and showed a delay in confirmed disability progression compared to placebo as measured with the EDSS.14 However, a North American trial that followed in 2004 was unable to replicate this finding.15 The patients in the European trial appeared to be in an earlier phase of SPMS with more active disease, and a post-hoc pooled analysis suggested that patients with active disease and those with more pronounced disability progression were more likely to benefit from treatment.16 Overall, interferons do not appear to appreciably alter disability in the long-term for patients with SPMS, though they may modify short-term, relapse-related disability.

Perhaps the most encouraging data for SPMS was found in the EXPAND trial, which investigated siponimod, an S1P receptor modulator that is more selective than fingolimod. The trial identified a 21% reduction in 3-month confirmed disability progression for SPMS patients taking siponimod compared with those taking a placebo.17 Although the patients in EXPAND did seem to have relatively less disease activity at baseline than those who participated in other SPMS trials, those who benefitted from siponimod were primarily patients who had clinical and/or radiographic relapses over the prior 2 years. Based on this, the FDA approved siponimod for active SPMS. The extent to which siponimod exerts a true neuroprotective effect beyond reducing inflammation has not been clearly established.

B-cell depleting therapies rituximab and ocrelizumab have been evaluated in both primary and secondary progressive MS populations. Early investigations of the chimeric rituximab in PPMS did not show benefits on disability (EDSS) progression; however, benefits were seen in analysis of some subgroups.18 With this in mind, the ORATORIO trial for the humanized version, ocreluzimab, included PPMS patients that were younger (aged < 55 years) and had cutoffs for disease duration (< 15 years for those with EDSS more than 5 years, < 10 years for those with EDSS less than 5 years). The study showed statistically significant changes on disability progression, which led to ocrelizumab receiving the first FDA indication for PPMS.11 There are substantial pathophysiologic similarities between PPMS and SPMS in the progressive phase.19 While these medications may have similar effects across these disease processes, these benefits have not yet been demonstrated in a prospective trial for the SPMS population. Regardless, B-cell depleting therapy is a reasonable consideration for select patients with active SPMS, consistent with a relapsing form of MS.

Therapies in Development

DMT development for progressive MS is a high priority area. Current immunomodulatory therapies for RRMS have consistently been ineffective in the inactive forms of MS, with the possible exceptions of ocrelizumab and siponimod. Therefore, instead of immunosuppression, many agents currently in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials target alternative pathophysiological processes in order to provide neuroprotection, and/or promote remyelination and neurogenesis. These targets include oxidative stress (OS), non-T cell mediated inflammation, and mitochondrial/energy failure.20 Below we review a selection of clinical trials testing agents following these approaches. Many agents have more than one potential mechanism of action (MOA) that could benefit progressive MS.

Lipoic acid (LA), also known as α-lipoic acid and thiotic acid, is one such agent targeting alternative pathophysiology in SPMS. LA is an endogenous agent synthesized de novo from fatty acids and cysteine as well as obtained in small amounts from foods.21 It has antioxidant (AO) properties including direct radical scavenging, regeneration of glutathione, and upregulation of AO enzymes via the NrF2 pathway.22 It supports mitochondria as a key cofactor for pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and it also aids mitochondrial DNA synthesis.21,22 Studies in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a widely used experimental mouse model of inflammatory demyelinating disease, also indicate a reduction in excessive microglial activation.23 A phase 2 pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 1200 mg LA in SPMS (n = 51) resulted in significantly less whole brain atrophy by SIENA (Structural Image Evaluation, Using Normalization, of Atrophy) at 2 years.24 A follow-up multicenter trial is ongoing.

Simvastatin also targets alternative pathophysiology in SPMS. It has anti-inflammatory effects, improves vascular function, and promotes neuroprotection by reducing excitotoxicity. A phase 2 RCT demonstrated a reduction in whole brain atrophy in SPMS (n = 140), and a phase 3 trial is underway.25 Ibudilast is another repurposed drug that targets alternative inflammation by inhibiting several cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, macrophage migration inhibitory factor and toll-like receptor 4. A phase 2 trial (n = 225) in both SPMS and PPMS also demonstrated a reduction in brain atrophy, but participants had high rates of AEs.26

Lithium and riluzole promote neuroprotection by reducing excitotoxicity. Lithium is a pharmacologic active cation used as a mood stabilizer and causes inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Animal models also indicate that lithium may decrease inflammation and positively impact neurogenesis.27 A crossover pilot trial demonstrated tolerability with trends toward stabilization of EDSS and reductions in brain atrophy.28 Three neuroprotective agents, riluzole (reduces glutamate excitotoxicity), fluoxetine (stimulates glycogenolysis and improves mitochondrial energy production), and amiloride (an acid-sensing ion channel blocker that opens in response to inflammation) were tested in a phase 2b multi-arm, multi-site parallel group RCT in SPMS (n = 445). The study failed to yield differences from placebo for any agent in reduction of brain volume loss.29 A prior study of lamotrigine, a sodium channel blocker, also failed to find changes in brain volume loss.30 These studies highlight the large sample sizes and/or long study durations needed to test agents using brain atrophy as primary outcome. In the future, precise surrogate markers of neuroprotection will be a great need for earlier phase trials. These results also suggest that targeting > 1 MOA may be necessary to treat SPMS effectively.

Efforts to promote remyelination target one hallmark of MS damage. High dose biotin (about 10,000× usual dose) may promote myelin repair as a cofactor for fatty acid synthesis and support mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. While a RCT yielded a greater proportion of participants with either PPMS or SPMS with improvement in disability than placebo at 12 months, an open label trial suggested otherwise indicating a need for a more definitive trial.31,32

Anti-LINGO-1 (opicinumab) is a monoclonal antibody that targets LINGO, a potent negative regulator of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination.33 Although this agent failed in a phase 2 trial in relapsing MS, and is thus unlikely to be tested in progressive forms, the innovative approach to stimulating oligodendrocytes is ongoing. One such effort is to use thyroid hormone, crucial to myelin formation during development, as a repair agent in MS.34 A dose-finding study of thyroid hormone was completed and efforts to develop a thyromimetic agent are ongoing.

Finally, efforts to promote neurogenesis remain a goal for many neurodegenerative diseases. Exercise appears to prevent age-related atrophy of the hippocampus in animals and humans and help maintain neuronal health.35 In patients with RRMS, cortical thickness is impacted positively by resistance training, which suggests a neuroprotective effect.36 A multi-center trial of exercise in patients with progressive MS investigating cognitive outcomes is ongoing.

Discontinuing DMT

In the early 1990s, the successful development of immune modulating therapies that reliably reduced disease activity in RRMS led to widespread initiation in patients with relapsing disease. However, guidance on when or if to discontinue DMT, even in those who have transitioned to SPMS, remains largely absent at this time. Requests to discontinue DMT may come from patients weary of taking medication (especially injections), bothered by AEs, or those who no longer perceive efficacy from their treatments. Clinicians also may question the benefit of immune modulation in patients with longstanding freedom from relapses or changes in MRI lesion burden.

To inform discussion centered on treatment discontinuation, a clinical trial is currently underway to better answer the question of when and how to withdraw MS therapy. Discontinuation of Disease Modifying Therapies in Multiple Sclerosis (DISCO-MS) is a prospective, placebo-controlled RCT and its primary endpoint is recurrence of disease activity over a 2 year follow-up period.37 Eligibility requirements for the trial include age > 55 years, 5-year freedom from relapses, and 3-year freedom from new MRI lesions (criteria informed by progressive MS cohort studies).31 In addition to demonstrating the active disease recurrence rates in this patient population, the trial also aims to identify risk factors for recurrent disease activity among treated MS patients.37 DISCO-MS builds upon a series of retrospective and observational studies that partially answered these questions, albeit in the context of biases inherent in retrospective or observational studies.

A Minneapolis MS Treatment and Research Center single-center study identified 77 SPMS patients with no acute CNS inflammatory events over 2 to 20 years and advised these patients to stop taking DMT.32 In this group, 11.7% of subjects experienced recurrent active disease. Age was the primary discriminating factor. The mean age of those who experienced disease activity was 56 years vs 61 years those who did not. A second observational study from France found that among 100 SPMS patients treated either with interferon β or glatiramer acetate for at least 6 months, 35% experienced some form of inflammatory disease upon discontinuation.38 Sixteen patients relapsed and 19 developed gadolinium-enhancing MR lesions after DMT discontinuation. However, the age of the cohort was younger than the Minneapolis study (47.2 years vs 61 years), and reasons for discontinuation (eg, AEs or lack of disease activity) were not considered in the analysis.

Other studies examining the safety of DMT discontinuation have not considered MS subtype or excluded patients with progressive subtypes of MS. The largest studies to date on DMT discontinuation utilized the international MSBase global patient registry, which identified nearly 5,000 patients who discontinued interferons (73%), glatiramer acetate (18%), natalizumab (6%), or fingolimod (3%), without specifying the reasons for discontinuation.39 Despite these shortcomings, data reveal trends that are helpful in predicting how MS tends to behave in patients who have discontinued therapy. Not surprisingly, disability progression was most likely among patients already characterized as having a progressive phenotype, while relapses were less likely to occur among older, progressive patients.

Although clinicians may be increasingly willing to discuss DMT discontinuation with their patients, at least 1 study exploring patient perspectives on stopping treatment suggests widespread reluctance to stop treatment. A survey conducted with participants in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis patient-report registry found that among survey respondents, only 11.9% would discontinue their MS medication if deemed stable, while 66.3% stated they were unlikely to stop treatment.40

These results suggest that before clinicians incorporate DMT discontinuation into the normal course of discussion with patients, they should be prepared to provide both education (on the wisdom of stopping under the right circumstances) and evidence to support when and how to make the recommendation. Based on existing evidence, criteria for recommending treatment discontinuation might include prolonged freedom from disease activity (≥ 5 years), age > 55 years or 60 years, and a progressive disease course. Thus far, no combination of factors has been shown to completely predict an event-free transition off of medicine. Since no fixed algorithm yet exists to guide DMT stoppage in MS, reasonable suggestions for monitoring patients might include surveillance MRIs, more frequent clinic visits, and possible transitional treatment for patients coming off of natalizumab or fingolimod, since these drugs have been associated with rebound disease activity when discontinued.41,42

Clinicians wishing to maximize function and quality of life for their patients at any age or stage of disease should look to nonpharmacologic interventions to lessen disability and maximize quality of life. While beyond the scope of this discussion, preliminary evidence suggests multimodal (aerobic, resistance, balance) exercise may enhance endurance and cognitive processing speed, and that treatment of comorbid diseases affecting vascular health benefits MS. 43

Conclusions

The development of numerous treatments for RRMS has established an entirely new landscape and disease course for those with MS. While this benefit has not entirely extended to those with progressive MS, those with active disease with superimposed relapses may receive limited benefit from these medications. New insights into the pathophysiology of progressive MS may lead us to new treatments through multiple alternative pathophysiologic pathways. Some early studies using this strategy show promise in slowing the progressive phase. Medication development for progressive MS faces multiple challenges due to lack of a single animal model demonstrating both pathology and clinical effects, absence of phase 1 surrogate biomarkers, and later phase trial endpoints that require large sample sizes and extended study durations. Nevertheless, the increase in number of trials and diversity of therapeutic approaches for progressive MS provides hope for effective therapy. Currently, the heterogeneity of the population with progressive MS requires an individualized treatment approach, and in some of these patients, stopping therapy may be a reasonable consideration. Symptomatic management remains critical for all patients with progressive MS as well as non-pharmacologic approaches that maximize quality of life.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data [published correction appears in Neurology. 2019;93(15):688]. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C, et al. Atlas of multiple sclerosis 2013: A growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology. 2014;83(11):1022-1024.

3. Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

4. Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. I. Clinical course and disability. Brain. 1989;112(Pt 1):133-146. 5. Confavreux C, Vukusic S. Age at disability milestones in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 3):595-605.

6. Tutuncu M, Tang J, Zeid NA, et al. Onset of progressive phase is an age-dependent clinical milestone in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19(2):188-198.

7. Schumacher GA, Beebe G, Kibler RF, et al. Problems of experimental trials of therapy in multiple sclerosis: report by the panel on the evaluation of experimental trials of therapy in multiple sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1965;122:552-568.

8. Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol. 1983;13(3):227-231.

9. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(1):121-127.

10. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173.

11. Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, et al; ORATORIO Clinical Investigators. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):209-220.

12. Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, et al; OLYMPUS trial group. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(4):460-471.

13. Kappos L, Bar-Or A, Cree BAC, et al; EXPAND Clinical Investigators. Siponimod versus placebo in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (EXPAND): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 study [published correction appears in Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2170]. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1263-1273.

14. Lublin F, Miller DH, Freedman MS, et al; INFORMS study investigators. Oral fingolimod in primary progressive multiple sclerosis (INFORMS): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017;389(10066):254]. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1075-1084.

15. Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Moreau T, Adeleine P. Relapses and progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(20):1430-1438.

16. Kremenchutzky M, Rice GP, Baskerville J, Wingerchuk DM, Ebers GC. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 9: observations on the progressive phase of the disease. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 3):584-594.

17. Leray E, Yaouanq J, Le Page E, et al. Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1900–1913.

18. Kapoor R, Ho PR, Campbell N, et al; ASCEND investigators. Effect of natalizumab on disease progression in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (ASCEND): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extension. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(5):405-415.

19. Koch MW, Mostert J, Uitdehaag B, Cutter G. Clinical outcome measures in SPMS trials: an analysis of the IMPACT and ASCEND original trial data sets [published online ahead of print, 2019 Sep 13]. Mult Scler. 2019;1352458519876701.

20. Hartung HP, Gonsette R, König N, et al; Mitoxantrone in Multiple Sclerosis Study Group (MIMS). Mitoxantrone in progressive multiple sclerosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9350):2018-2025.

21. Placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon beta-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. European Study Group on interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS. Lancet. 1998;352(9139):1491-1497.

22. Gorąca A, Huk-Kolega H, Piechota A, Kleniewska P, Ciejka E, Skibska B. Lipoic acid - biological activity and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:849-858.

23. Chaudhary P, Marracci G, Pocius E, Galipeau D, Morris B, Bourdette D. Effects of lipoic acid on primary murine microglial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2019;334:576972.

24. Spain R, Powers K, Murchison C, et al. Lipoic acid in secondary progressive MS: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4:e374.

25. Chataway J, Schuerer N, Alsanousi A, et al. Effect of high-dose simvastatin on brain atrophy and disability in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-STAT): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:2213-2221.

26. Fox RJ, Coffey CS, Conwit R, et al. Phase 2 Trial of Ibudilast in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:846-855.

27. Rinker JR, 2nd, Cossey TC, Cutter GR, Culpepper WJ. A retrospective review of lithium usage in veterans with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2013;2:327-333.

28. Rinker JR, W Meador, V Sung, A Nicholas, G Cutter. Results of a pilot trial of lithium in progressive multiple sclerosis. ECTRIMS Online Library. 09/16/16; 145965; P12822016.

29. Chataway J, De Angelis F, Connick P, et al; MS-SMART Investigators. Efficacy of three neuroprotective drugs in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-SMART): a phase 2b, multiarm, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(3):214-225.

30. Kapoor R, Furby J, Hayton T, et al. Lamotrigine for neuroprotection in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:681-688.

31. Paz Soldan MM, Novotna M, Abou Zeid N, et al. Relapses and disability accumulation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84:81-88.

32. Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in nonrelapsing multiple sclerosis: experience from a clinical practice. Int J MS Care. 2017;19:11-14.

33. Ruggieri S, Tortorella C, Gasperini C. Anti lingo 1 (opicinumab) a new monoclonal antibody tested in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother 2017;17:1081-1089.

34. Hartley MD, Banerji T, Tagge IJ, et al. Myelin repair stimulated by CNS-selective thyroid hormone action. JCI Insight. 2019;4(8):e126329.

35. Firth J, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 2018;166:230-238.

36. Kjolhede T, Siemonsen S, Wenzel D, et al. Can resistance training impact MRI outcomes in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler. 2018;24:1356-1365.

37. US National Library of Medicine, Clinicaltrials.gov. Discontinuation of Disease Modifying Therapies (DMTs) in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) (DISCOMS). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03073603. Updated February 10, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

38. Bonenfant J, Bajeux E, Deburghgraeve V, Le Page E, Edan G, Kerbrat A. Can we stop immunomodulatory treatments in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis? Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:237-244.

39. Kister I, Spelman T, Patti F, et al. Predictors of relapse and disability progression in MS patients who discontinue disease-modifying therapy. J Neurol Sci. 2018;391:72-76.

40. McGinley MP, Cola PA, Fox RJ, Cohen JA, Corboy JJ, Miller D. Perspectives of individuals with multiple sclerosis on discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies. Mult Scler. 2019:1352458519867314.

41. Hatcher SE, Waubant E, Graves JS. Rebound Syndrome in Multiple Sclerosis After Fingolimod Cessation-Reply. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1376.

42. Vellinga MM, Castelijns JA, Barkhof F, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH. Postwithdrawal rebound increase in T2 lesional activity in natalizumab-treated MS patients. Neurology. 2008;70:1150-1151.

43. Sandroff BM, Bollaert RE, Pilutti LA, et al. Multimodal exercise training in multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial in persons with substantial mobility disability. Contemp Clin Trials 2017;61:39-47.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, with recent estimates of around 1 million people living with MS in the US.1 In many countries, MS is a leading cause of disability among young adults, second only to trauma.2 Clinically, neurologic worsening (ie, disability) in MS can occur in the relapsing-remitting (RRMS) phase of disease due to incomplete recovery from neuroinflammatory relapses. However, in the 15% of patients with a progressive course from onset (PPMS), and in those with RRMS who transition to a secondary progressive phenotype (SPMS), neurologic worsening follows a slowly progressive pattern.3 A progressive disease course—either PPMS at onset or transitioning to SPMS—is the dominant factor affecting MS-related neurologic disability accumulation. In particular, epidemiologic studies have shown that, in the absence of transitioning to a progressive disease course, < 5% of individuals with MS will accumulate sufficient disability to necessitate use of a cane for ambulation.4-6 Therefore, developing disease modifying therapies (DMTs) that are highly effective at slowing or stopping the gradual accumulation of neurologic disability in progressive MS represent a critical unmet need.

Research into the development of DMTs for progressive MS has been hindered by a number of factors. In particular, the clinical definition and diagnosis of progressive MS has been an evolving concept. Diagnostic criteria for MS, which help facilitate the enrollment of appropriate subjects into clinical trials, have only recently clarified the current consensus definition for progressive MS—steadily increasing neurologic disability independent of clinical relapses. Looking back to the Schumacher criteria in 1965 and Poser criteria in 1983, it was acknowledged that neurologic symptoms in MS may follow a relapsing-remitting or progressive pattern, but little attempt was made to define progressive MS.7,8 The original McDonald criteria in 2001 defined diagnostic criteria for progressive MS.9 These criteria continued to evolve through subsequent revisions (eg, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] specific oligoclonal bands no longer are an absolute requirement), and only in the 2017 revision was it emphasized that disability progression must occur independent of clinical relapses, concordant with similar emphasis in the 2013 revision of MS clinical course definitions.3,10

The interpretation of prior clinical trials of DMT for progressive MS must consider this evolving clinical definition. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved mitoxantrone in 2000—making it the first DMT to carry an approved label for SPMS. While achieving significant clinical efficacy, it is clear from the details of the trial that the enrolled subjects had a high degree of inflammatory disease activity, which suggests that mitoxantrone treats neuroinflammation and not relapse-independent worsening. More recently, disparate results were seen in the anti-CD20 (rituximab, ocrelizumab) and S1P receptor modulator (fingolimod, siponimod) trials targeted at patients with primary and secondary progressive MS.11-14 Although there are differences between these therapies, they are more similar than not within the same therapeutic class. Taken together, these trials illustrate the critical impact the narrower inclusion/exclusion criteria (namely age and extent of inflammatory activity) had on attaining positive outcomes. Other considerations, such as confounding illness, also may impact trial recruitment and generalizability of findings.

The lack of known biological targets in progressive MS, which is a complex disease with an incompletely understood and heterogeneous pathology, also hinders DMT development. Decades of research has characterized multifocal central nervous system (CNS) lesions that exhibit features of demyelination, inflammation, reactive gliosis, axonal loss, and neuronal damage. Until recently, however, much of this research focused on the relapsing phase of disease, and so the understanding of the pathologic underpinnings of progressive disease has remained limited. Current areas of investigation encompass a broad range of pathological processes, such as microglial activation, meningeal lymphoid follicles, remyelination failure, vulnerability of chronically demyelinated axons, oxidative injury, iron accumulation, mitochondrial damage, and others. There is the added complication that the pathologic processes underlying progressive MS are superimposed on the CNS aging process. In particular, the transition to progressive MS and the rate of disability accumulation during progressive MS show strong correlation with age.6,15-17

Finally, DMT development for progressive MS also is hindered by the lack of specific surrogate and clinical outcome measures. Trials for relapsing MS have benefited greatly from the relatively straightforward assessment of clinical relapses and inflammatory disease activity on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). With the goal of developing DMTs that are highly effective at slowing or stopping the gradual accumulation of neurologic disability in progressive MS, which by definition occurs independent of clinical relapses, these measures are not directly relevant. The longitudinal clinical disability outcome measures change at a slower rate than in early, relapsing disease. The use of standardized scales (eg, the Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]), lower limb function, upper limb function, cognition, or a combination is a subject of ongoing debate. For example, the ASCEND and IMPACT trials (placebo-controlled trials for SPMS with natalizumab and interferon β-1a, respectively) showed no significant impact in EDSS progression—but in both of these trials, the 9-hole peg test (9-HPT), a performance measure for upper limb function, showed significant improvement.10,18 Particularly in those with an EDSS of > 6.5, who are unlikely to have measurable EDSS progression, functional tests such as the 9-HPT or timed 25-foot walk may be more sensitive as measures for disability progression.11 MRI measures of brain atrophy is the current gold standard surrogate outcome for clinical trials in progressive MS, but others that may warrant consideration include optical coherence tomography (OCT) or CSF markers of axonal degeneration.

DMT for Progressive MS

Current diagnostic nomenclature separates patients with active (superimposed clinical and/or radiographic relapses) from those with inactive disease.3,12 Relapsing forms of MS include all RRMS and those with SPMS with superimposed relapses (ie, active SPMS). Following this paradigm shift, the FDA changed the indication for already approved DMT from RRMS to relapsing forms of MS. Below is a discussion of DMT that specifically use the term SPMS and PPMS in the indication, where phase 3 trial data for progressive MS is available.

In 2019, the FDA approved the first oral medication (siponimod) for active SPMS. Subsequently, updates to the labels of the older DMT expanded to include active SPMS. Until 2019, the only FDA approved medication for SPMS was mitoxantrone, and use of this medication was limited due to unfavorable adverse effects (AEs). No medications had obtained FDA approval for inactive SPMS to this point, which represented an unmet need for a considerable number of patients.

Mitoxantrone became the first DMT approved for use in SPMS in 2000 following early trials that showed reductions in EDSS worsening, change in ambulation index, reduced number of treated relapses, and prolonged time to first treated relapse. However, as with some of the other positive trials in progressive MS, it is difficult to discern the impact of suppression of relapses as opposed to direct impact on progressive pathophysiology. Within the placebo arm, for example, there were 129 relapses among the 64 subjects, which suggests that these cases had particularly active disease or were in the early stages of SPMS.13 Furthermore, the use of this medication was limited due to concerns of cardiotoxicity and hematologic malignancy as serious AEs.

The trials of interferon β-1b illustrate the same difficulty of isolating possible benefits in disease progression from disability accumulated from relapses. The first interferon β-1b trial for SPMS, was conducted in Europe using fingolimod and showed a delay in confirmed disability progression compared to placebo as measured with the EDSS.14 However, a North American trial that followed in 2004 was unable to replicate this finding.15 The patients in the European trial appeared to be in an earlier phase of SPMS with more active disease, and a post-hoc pooled analysis suggested that patients with active disease and those with more pronounced disability progression were more likely to benefit from treatment.16 Overall, interferons do not appear to appreciably alter disability in the long-term for patients with SPMS, though they may modify short-term, relapse-related disability.

Perhaps the most encouraging data for SPMS was found in the EXPAND trial, which investigated siponimod, an S1P receptor modulator that is more selective than fingolimod. The trial identified a 21% reduction in 3-month confirmed disability progression for SPMS patients taking siponimod compared with those taking a placebo.17 Although the patients in EXPAND did seem to have relatively less disease activity at baseline than those who participated in other SPMS trials, those who benefitted from siponimod were primarily patients who had clinical and/or radiographic relapses over the prior 2 years. Based on this, the FDA approved siponimod for active SPMS. The extent to which siponimod exerts a true neuroprotective effect beyond reducing inflammation has not been clearly established.

B-cell depleting therapies rituximab and ocrelizumab have been evaluated in both primary and secondary progressive MS populations. Early investigations of the chimeric rituximab in PPMS did not show benefits on disability (EDSS) progression; however, benefits were seen in analysis of some subgroups.18 With this in mind, the ORATORIO trial for the humanized version, ocreluzimab, included PPMS patients that were younger (aged < 55 years) and had cutoffs for disease duration (< 15 years for those with EDSS more than 5 years, < 10 years for those with EDSS less than 5 years). The study showed statistically significant changes on disability progression, which led to ocrelizumab receiving the first FDA indication for PPMS.11 There are substantial pathophysiologic similarities between PPMS and SPMS in the progressive phase.19 While these medications may have similar effects across these disease processes, these benefits have not yet been demonstrated in a prospective trial for the SPMS population. Regardless, B-cell depleting therapy is a reasonable consideration for select patients with active SPMS, consistent with a relapsing form of MS.

Therapies in Development

DMT development for progressive MS is a high priority area. Current immunomodulatory therapies for RRMS have consistently been ineffective in the inactive forms of MS, with the possible exceptions of ocrelizumab and siponimod. Therefore, instead of immunosuppression, many agents currently in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials target alternative pathophysiological processes in order to provide neuroprotection, and/or promote remyelination and neurogenesis. These targets include oxidative stress (OS), non-T cell mediated inflammation, and mitochondrial/energy failure.20 Below we review a selection of clinical trials testing agents following these approaches. Many agents have more than one potential mechanism of action (MOA) that could benefit progressive MS.