User login

Hourly air pollution exposure: A risk factor for stroke

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Limited studies have investigated the association between hourly exposure to air pollutants and specific stroke subtypes, especially in regions with moderate to high levels of air pollution.

- The multicenter case-crossover study evaluated the association between hourly exposure to air pollution and stroke among 86,635 emergency admissions for stroke across 10 hospitals in 3 cities.

- Of 86,635 admissions, 79,478 were admitted for ischemic stroke, 3,122 for hemorrhagic stroke, and 4,035 for undetermined type of stroke.

- Hourly levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), respirable PM (PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) were collected from the China National Environmental Monitoring Center.

TAKEAWAY:

- Exposure to NO2 and SO2 increased the risk for emergency admission for stroke shortly after exposure by 3.34% (95% confidence interval, 1.41%-5.31%) and 2.81% (95% CI, 1.15%-4.51%), respectively.

- Among men, exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 increased the risk for emergency admission for stroke by 3.40% (95% CI, 1.21%-5.64%) and 4.33% (95% CI, 2.18%-6.53%), respectively.

- Among patients aged less than 65 years, exposure to PM10 and NO2 increased the risk for emergency admissions for stroke shortly after exposure by 4.88% (95% CI, 2.29%-7.54%) and 5.59% (95% CI, 2.34%-8.93%), respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“These variations in susceptibility highlight the importance of implementing effective health protection measures to reduce exposure to air pollution and mitigate the risk of stroke in younger and male populations,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Xin Lv, MD, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing. It was published online in the journal Stroke.

LIMITATIONS:

- Using data from the nearest monitoring site to the hospital address may lead to localized variations in pollution concentrations when assessing exposure.

- There may be a possibility of residual confounding resulting from time-varying lifestyle-related factors.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Project for Medical Research and Health Sciences. No disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Limited studies have investigated the association between hourly exposure to air pollutants and specific stroke subtypes, especially in regions with moderate to high levels of air pollution.

- The multicenter case-crossover study evaluated the association between hourly exposure to air pollution and stroke among 86,635 emergency admissions for stroke across 10 hospitals in 3 cities.

- Of 86,635 admissions, 79,478 were admitted for ischemic stroke, 3,122 for hemorrhagic stroke, and 4,035 for undetermined type of stroke.

- Hourly levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), respirable PM (PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) were collected from the China National Environmental Monitoring Center.

TAKEAWAY:

- Exposure to NO2 and SO2 increased the risk for emergency admission for stroke shortly after exposure by 3.34% (95% confidence interval, 1.41%-5.31%) and 2.81% (95% CI, 1.15%-4.51%), respectively.

- Among men, exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 increased the risk for emergency admission for stroke by 3.40% (95% CI, 1.21%-5.64%) and 4.33% (95% CI, 2.18%-6.53%), respectively.

- Among patients aged less than 65 years, exposure to PM10 and NO2 increased the risk for emergency admissions for stroke shortly after exposure by 4.88% (95% CI, 2.29%-7.54%) and 5.59% (95% CI, 2.34%-8.93%), respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“These variations in susceptibility highlight the importance of implementing effective health protection measures to reduce exposure to air pollution and mitigate the risk of stroke in younger and male populations,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Xin Lv, MD, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing. It was published online in the journal Stroke.

LIMITATIONS:

- Using data from the nearest monitoring site to the hospital address may lead to localized variations in pollution concentrations when assessing exposure.

- There may be a possibility of residual confounding resulting from time-varying lifestyle-related factors.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Project for Medical Research and Health Sciences. No disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Limited studies have investigated the association between hourly exposure to air pollutants and specific stroke subtypes, especially in regions with moderate to high levels of air pollution.

- The multicenter case-crossover study evaluated the association between hourly exposure to air pollution and stroke among 86,635 emergency admissions for stroke across 10 hospitals in 3 cities.

- Of 86,635 admissions, 79,478 were admitted for ischemic stroke, 3,122 for hemorrhagic stroke, and 4,035 for undetermined type of stroke.

- Hourly levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), respirable PM (PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) were collected from the China National Environmental Monitoring Center.

TAKEAWAY:

- Exposure to NO2 and SO2 increased the risk for emergency admission for stroke shortly after exposure by 3.34% (95% confidence interval, 1.41%-5.31%) and 2.81% (95% CI, 1.15%-4.51%), respectively.

- Among men, exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 increased the risk for emergency admission for stroke by 3.40% (95% CI, 1.21%-5.64%) and 4.33% (95% CI, 2.18%-6.53%), respectively.

- Among patients aged less than 65 years, exposure to PM10 and NO2 increased the risk for emergency admissions for stroke shortly after exposure by 4.88% (95% CI, 2.29%-7.54%) and 5.59% (95% CI, 2.34%-8.93%), respectively.

IN PRACTICE:

“These variations in susceptibility highlight the importance of implementing effective health protection measures to reduce exposure to air pollution and mitigate the risk of stroke in younger and male populations,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Xin Lv, MD, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing. It was published online in the journal Stroke.

LIMITATIONS:

- Using data from the nearest monitoring site to the hospital address may lead to localized variations in pollution concentrations when assessing exposure.

- There may be a possibility of residual confounding resulting from time-varying lifestyle-related factors.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Project for Medical Research and Health Sciences. No disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fibromyalgia, CFS more prevalent in patients with IBS

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The authors conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate the prevalence and predictors of fibromyalgia and CFS in patients hospitalized with IBS vs people without IBS.

- The researchers used ICD-10 codes to analyze U.S. National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data from 2016-2019.

- A subgroup analysis investigated associations with IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS-constipation (IBS-C), and IBS-mixed types.

- Variables included patient age, sex, ethnicity, race, household income, insurance status, and hospital-level characteristics (including location, bed size, and teaching status).

TAKEAWAY:

- Among 1.2 million patients with IBS included in the study, 10.7% also had fibromyalgia and 0.4% had CFS. The majority of fibromyalgia (96.5%) and CFS (89.9%) patients were female and White (86.5%). CFS prevalence also was highest among White persons (90.7%).

- The prevalence of fibromyalgia and CFS was significantly higher in patients with IBS compared to those without IBS (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 5.33 for fibromyalgia and AOR, 5.4 for CFS).

- IBS-D, IBS-C, and IBS-mixed types were independently associated with increased odds of fibromyalgia and CFS.

- Independent predictors of increased odds of fibromyalgia and CFS, respectively, were increasing age (AOR, 1.02 for both), female sex (AOR, 11.2; AOR, 1.86) and White race (AOR, 2.04; AOR, 1.69).

- Overall, White race, lower socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and hyperlipidemia were associated with increased odds of fibromyalgia. For CFS, increased odds were associated with White race, higher socioeconomic status, smoking, obesity, and hyperlipidemia.

IN PRACTICE:

“In current clinical practice, there is a high risk of neglecting multi-syndromic patients. We as clinicians should integrate in our practice with regular screening for other somatic disorders in the IBS population and determine the need to consult other specialties like rheumatology and psychiatry to improve the overall health outcome in IBS patients,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Zahid Ijaz Tarar, MD, University of Missouri, Columbia, led the study, which was published online in Biomedicines.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective design of the study can only show associations, not a causal relationship. Lack of blinding and randomization in the data creates bias. The NIS database does not provide medication and laboratory data, so the effect of pharmaceutical therapies cannot be measured.

DISCLOSURES:

The research received no external funding. The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The authors conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate the prevalence and predictors of fibromyalgia and CFS in patients hospitalized with IBS vs people without IBS.

- The researchers used ICD-10 codes to analyze U.S. National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data from 2016-2019.

- A subgroup analysis investigated associations with IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS-constipation (IBS-C), and IBS-mixed types.

- Variables included patient age, sex, ethnicity, race, household income, insurance status, and hospital-level characteristics (including location, bed size, and teaching status).

TAKEAWAY:

- Among 1.2 million patients with IBS included in the study, 10.7% also had fibromyalgia and 0.4% had CFS. The majority of fibromyalgia (96.5%) and CFS (89.9%) patients were female and White (86.5%). CFS prevalence also was highest among White persons (90.7%).

- The prevalence of fibromyalgia and CFS was significantly higher in patients with IBS compared to those without IBS (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 5.33 for fibromyalgia and AOR, 5.4 for CFS).

- IBS-D, IBS-C, and IBS-mixed types were independently associated with increased odds of fibromyalgia and CFS.

- Independent predictors of increased odds of fibromyalgia and CFS, respectively, were increasing age (AOR, 1.02 for both), female sex (AOR, 11.2; AOR, 1.86) and White race (AOR, 2.04; AOR, 1.69).

- Overall, White race, lower socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and hyperlipidemia were associated with increased odds of fibromyalgia. For CFS, increased odds were associated with White race, higher socioeconomic status, smoking, obesity, and hyperlipidemia.

IN PRACTICE:

“In current clinical practice, there is a high risk of neglecting multi-syndromic patients. We as clinicians should integrate in our practice with regular screening for other somatic disorders in the IBS population and determine the need to consult other specialties like rheumatology and psychiatry to improve the overall health outcome in IBS patients,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Zahid Ijaz Tarar, MD, University of Missouri, Columbia, led the study, which was published online in Biomedicines.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective design of the study can only show associations, not a causal relationship. Lack of blinding and randomization in the data creates bias. The NIS database does not provide medication and laboratory data, so the effect of pharmaceutical therapies cannot be measured.

DISCLOSURES:

The research received no external funding. The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The authors conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate the prevalence and predictors of fibromyalgia and CFS in patients hospitalized with IBS vs people without IBS.

- The researchers used ICD-10 codes to analyze U.S. National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data from 2016-2019.

- A subgroup analysis investigated associations with IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS-constipation (IBS-C), and IBS-mixed types.

- Variables included patient age, sex, ethnicity, race, household income, insurance status, and hospital-level characteristics (including location, bed size, and teaching status).

TAKEAWAY:

- Among 1.2 million patients with IBS included in the study, 10.7% also had fibromyalgia and 0.4% had CFS. The majority of fibromyalgia (96.5%) and CFS (89.9%) patients were female and White (86.5%). CFS prevalence also was highest among White persons (90.7%).

- The prevalence of fibromyalgia and CFS was significantly higher in patients with IBS compared to those without IBS (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 5.33 for fibromyalgia and AOR, 5.4 for CFS).

- IBS-D, IBS-C, and IBS-mixed types were independently associated with increased odds of fibromyalgia and CFS.

- Independent predictors of increased odds of fibromyalgia and CFS, respectively, were increasing age (AOR, 1.02 for both), female sex (AOR, 11.2; AOR, 1.86) and White race (AOR, 2.04; AOR, 1.69).

- Overall, White race, lower socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and hyperlipidemia were associated with increased odds of fibromyalgia. For CFS, increased odds were associated with White race, higher socioeconomic status, smoking, obesity, and hyperlipidemia.

IN PRACTICE:

“In current clinical practice, there is a high risk of neglecting multi-syndromic patients. We as clinicians should integrate in our practice with regular screening for other somatic disorders in the IBS population and determine the need to consult other specialties like rheumatology and psychiatry to improve the overall health outcome in IBS patients,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Zahid Ijaz Tarar, MD, University of Missouri, Columbia, led the study, which was published online in Biomedicines.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective design of the study can only show associations, not a causal relationship. Lack of blinding and randomization in the data creates bias. The NIS database does not provide medication and laboratory data, so the effect of pharmaceutical therapies cannot be measured.

DISCLOSURES:

The research received no external funding. The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Spinal cord stimulator restores Parkinson patient’s gait

The neuroprosthesis involves targeted epidural electrical stimulation of areas of the lumbosacral spinal cord that produce walking.

This new therapeutic tool offers hope to patients with PD and, combined with existing approaches, may alleviate a motor sign in PD for which there is currently “no real solution,” study investigator Eduardo Martin Moraud, PhD, who leads PD research at the Defitech Center for Interventional Neurotherapies (NeuroRestore), Lausanne, Switzerland, said in an interview.

“This is exciting for the many patients that develop gait deficits and experience frequent falls, who can only rely on physical therapy to try and minimize the consequences,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Medicine.

Personalized stimulation

About 90% of people with advanced PD experience gait and balance problems or freezing-of-gait episodes. These locomotor deficits typically don’t respond well to dopamine replacement therapy or deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus, possibly because the neural origins of these motor problems involve brain circuits not related to dopamine, said Dr. Moraud.

Continuous electrical stimulation over the cervical or thoracic segments of the spinal cord reduces locomotor deficits in some people with PD, but the broader application of this strategy has led to variable and unsatisfying outcomes.

The new approach focuses on correcting abnormal activation of circuits in the lumbar spinal cord, a region that hosts all the neurons that control activation of the leg muscles used for walking.

The stimulating device is placed on the lumbar region of the spinal cord, which sends messages to leg muscles. It is wired to a small impulse generator implanted under the skin of the abdomen. Sensors placed in shoes align the stimulation to the patient’s movement.

The system can detect the beginning of a movement, immediately activate the appropriate electrode, and so facilitate the necessary movement, be that leg flexion, extension, or propulsion, said Dr. Moraud. “This allows for increased walking symmetry, reinforced balance, and increased length of steps.”

The concept of this neuroprosthesis is similar to that used to allow patients with a spinal cord injury (SCI) to walk. But unlike patients with SCI, those with PD can move their legs, indicating that there is a descending command from the brain that needs to interact with the stimulation of the spinal cord, and patients with PD can feel the stimulation.

“Both these elements imply that amplitudes of stimulation need to be much lower in PD than SCI, and that stimulation needs to be fully personalized in PD to synergistically interact with the descending commands from the brain.”

After fine-tuning this new neuroprosthesis in animal models, researchers implanted the device in a 62-year-old man with a 30-year history of PD who presented with severe gait impairments, including marked gait asymmetry, reduced stride length, and balance problems.

Gait restored to near normal

The patient had frequent freezing-of-gait episodes when turning and passing through narrow paths, which led to multiple falls a day. This was despite being treated with DBS and dopaminergic replacement therapies.

But after getting used to the neuroprosthesis, the patient now walks with a gait akin to that of people without PD.

“Our experience in the preclinical animal models and this first patient is that gait can be restored to an almost healthy level, but this, of course, may vary across patients, depending on the severity of their disease progression, and their other motor deficits,” said Dr. Moraud.

When the neuroprosthesis is turned on, freezing of gait nearly vanishes, both with and without DBS.

In addition, the neuroprosthesis augmented the impact of the patient’s rehabilitation program, which involved a variety of regular exercises, including walking on basic and complex terrains, navigating outdoors in community settings, balance training, and basic physical therapy.

Frequent use of the neuroprosthesis during gait rehabilitation also translated into “highly improved” quality of life as reported by the patient (and his wife), said Dr. Moraud.

The patient has now been using the neuroprosthesis about 8 hours a day for nearly 2 years, only switching it off when sitting for long periods of time or while sleeping.

“He regained the capacity to walk in complex or crowded environments such as shops, airports, or his own home, without falling,” said Dr. Moraud. “He went from falling five to six times per day to one or two [falls] every couple of weeks. He’s also much more confident. He can walk for many miles, run, and go on holidays, without the constant fear of falling and having related injuries.”

Dr. Moraud stressed that the device does not replace DBS, which is a “key therapy” that addresses other deficits in PD, such as rigidity or slowness of movement. “What we propose here is a fully complementary approach for the gait problems that are not well addressed by DBS.”

One of the next steps will be to evaluate the efficacy of this approach across a wider spectrum of patient profiles to fully define the best responders, said Dr. Moraud.

A ‘tour de force’

In a comment, Michael S. Okun, MD, director of the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, and medical director of the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the researchers used “a smarter device” than past approaches that failed to adequately address progressive walking challenges of patients with PD.

Although it’s “tempting to get excited” about the findings, it’s important to consider that the study included only one human subject and did not target circuits for both walking and balance, said Dr. Okun. “It’s possible that even if future studies revealed a benefit for walking, the device may or may not address falling.”

In an accompanying editorial, Aviv Mizrahi-Kliger, MD, PhD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, and Karunesh Ganguly, MD, PhD, Neurology and Rehabilitation Service, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, called the study an “impressive tour de force,” with data from the nonhuman primate model and the individual with PD “jointly” indicating that epidural electrical stimulation (EES) “is a very promising treatment for several aspects of gait, posture and balance impairments in PD.”

But although the effect in the single patient “is quite impressive,” the “next crucial step” is to test this approach in a larger cohort of patients, they said.

They noted the nonhuman model does not exhibit freezing of gait, “which precluded the ability to corroborate or further study the role of EES in alleviating this symptom of PD in an animal model.”

In addition, stimulation parameters in the patient with PD “had to rely on estimated normal activity patterns, owing to the inability to measure pre-disease patterns at the individual level,” they wrote.

The study received funding from the Defitech Foundation, ONWARD Medical, CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Parkinson Schweiz Foundation, European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (NeuWalk), European Research Council, Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, Bertarelli Foundation, and Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Moraud and other study authors hold various patents or applications in relation to the present work. Dr. Mizrahi-Kliger has no relevant conflicts of interest; Dr. Ganguly has a patent for modulation of sensory inputs to improve motor recovery from stroke and has been a consultant to Cala Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuroprosthesis involves targeted epidural electrical stimulation of areas of the lumbosacral spinal cord that produce walking.

This new therapeutic tool offers hope to patients with PD and, combined with existing approaches, may alleviate a motor sign in PD for which there is currently “no real solution,” study investigator Eduardo Martin Moraud, PhD, who leads PD research at the Defitech Center for Interventional Neurotherapies (NeuroRestore), Lausanne, Switzerland, said in an interview.

“This is exciting for the many patients that develop gait deficits and experience frequent falls, who can only rely on physical therapy to try and minimize the consequences,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Medicine.

Personalized stimulation

About 90% of people with advanced PD experience gait and balance problems or freezing-of-gait episodes. These locomotor deficits typically don’t respond well to dopamine replacement therapy or deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus, possibly because the neural origins of these motor problems involve brain circuits not related to dopamine, said Dr. Moraud.

Continuous electrical stimulation over the cervical or thoracic segments of the spinal cord reduces locomotor deficits in some people with PD, but the broader application of this strategy has led to variable and unsatisfying outcomes.

The new approach focuses on correcting abnormal activation of circuits in the lumbar spinal cord, a region that hosts all the neurons that control activation of the leg muscles used for walking.

The stimulating device is placed on the lumbar region of the spinal cord, which sends messages to leg muscles. It is wired to a small impulse generator implanted under the skin of the abdomen. Sensors placed in shoes align the stimulation to the patient’s movement.

The system can detect the beginning of a movement, immediately activate the appropriate electrode, and so facilitate the necessary movement, be that leg flexion, extension, or propulsion, said Dr. Moraud. “This allows for increased walking symmetry, reinforced balance, and increased length of steps.”

The concept of this neuroprosthesis is similar to that used to allow patients with a spinal cord injury (SCI) to walk. But unlike patients with SCI, those with PD can move their legs, indicating that there is a descending command from the brain that needs to interact with the stimulation of the spinal cord, and patients with PD can feel the stimulation.

“Both these elements imply that amplitudes of stimulation need to be much lower in PD than SCI, and that stimulation needs to be fully personalized in PD to synergistically interact with the descending commands from the brain.”

After fine-tuning this new neuroprosthesis in animal models, researchers implanted the device in a 62-year-old man with a 30-year history of PD who presented with severe gait impairments, including marked gait asymmetry, reduced stride length, and balance problems.

Gait restored to near normal

The patient had frequent freezing-of-gait episodes when turning and passing through narrow paths, which led to multiple falls a day. This was despite being treated with DBS and dopaminergic replacement therapies.

But after getting used to the neuroprosthesis, the patient now walks with a gait akin to that of people without PD.

“Our experience in the preclinical animal models and this first patient is that gait can be restored to an almost healthy level, but this, of course, may vary across patients, depending on the severity of their disease progression, and their other motor deficits,” said Dr. Moraud.

When the neuroprosthesis is turned on, freezing of gait nearly vanishes, both with and without DBS.

In addition, the neuroprosthesis augmented the impact of the patient’s rehabilitation program, which involved a variety of regular exercises, including walking on basic and complex terrains, navigating outdoors in community settings, balance training, and basic physical therapy.

Frequent use of the neuroprosthesis during gait rehabilitation also translated into “highly improved” quality of life as reported by the patient (and his wife), said Dr. Moraud.

The patient has now been using the neuroprosthesis about 8 hours a day for nearly 2 years, only switching it off when sitting for long periods of time or while sleeping.

“He regained the capacity to walk in complex or crowded environments such as shops, airports, or his own home, without falling,” said Dr. Moraud. “He went from falling five to six times per day to one or two [falls] every couple of weeks. He’s also much more confident. He can walk for many miles, run, and go on holidays, without the constant fear of falling and having related injuries.”

Dr. Moraud stressed that the device does not replace DBS, which is a “key therapy” that addresses other deficits in PD, such as rigidity or slowness of movement. “What we propose here is a fully complementary approach for the gait problems that are not well addressed by DBS.”

One of the next steps will be to evaluate the efficacy of this approach across a wider spectrum of patient profiles to fully define the best responders, said Dr. Moraud.

A ‘tour de force’

In a comment, Michael S. Okun, MD, director of the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, and medical director of the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the researchers used “a smarter device” than past approaches that failed to adequately address progressive walking challenges of patients with PD.

Although it’s “tempting to get excited” about the findings, it’s important to consider that the study included only one human subject and did not target circuits for both walking and balance, said Dr. Okun. “It’s possible that even if future studies revealed a benefit for walking, the device may or may not address falling.”

In an accompanying editorial, Aviv Mizrahi-Kliger, MD, PhD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, and Karunesh Ganguly, MD, PhD, Neurology and Rehabilitation Service, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, called the study an “impressive tour de force,” with data from the nonhuman primate model and the individual with PD “jointly” indicating that epidural electrical stimulation (EES) “is a very promising treatment for several aspects of gait, posture and balance impairments in PD.”

But although the effect in the single patient “is quite impressive,” the “next crucial step” is to test this approach in a larger cohort of patients, they said.

They noted the nonhuman model does not exhibit freezing of gait, “which precluded the ability to corroborate or further study the role of EES in alleviating this symptom of PD in an animal model.”

In addition, stimulation parameters in the patient with PD “had to rely on estimated normal activity patterns, owing to the inability to measure pre-disease patterns at the individual level,” they wrote.

The study received funding from the Defitech Foundation, ONWARD Medical, CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Parkinson Schweiz Foundation, European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (NeuWalk), European Research Council, Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, Bertarelli Foundation, and Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Moraud and other study authors hold various patents or applications in relation to the present work. Dr. Mizrahi-Kliger has no relevant conflicts of interest; Dr. Ganguly has a patent for modulation of sensory inputs to improve motor recovery from stroke and has been a consultant to Cala Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuroprosthesis involves targeted epidural electrical stimulation of areas of the lumbosacral spinal cord that produce walking.

This new therapeutic tool offers hope to patients with PD and, combined with existing approaches, may alleviate a motor sign in PD for which there is currently “no real solution,” study investigator Eduardo Martin Moraud, PhD, who leads PD research at the Defitech Center for Interventional Neurotherapies (NeuroRestore), Lausanne, Switzerland, said in an interview.

“This is exciting for the many patients that develop gait deficits and experience frequent falls, who can only rely on physical therapy to try and minimize the consequences,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Medicine.

Personalized stimulation

About 90% of people with advanced PD experience gait and balance problems or freezing-of-gait episodes. These locomotor deficits typically don’t respond well to dopamine replacement therapy or deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus, possibly because the neural origins of these motor problems involve brain circuits not related to dopamine, said Dr. Moraud.

Continuous electrical stimulation over the cervical or thoracic segments of the spinal cord reduces locomotor deficits in some people with PD, but the broader application of this strategy has led to variable and unsatisfying outcomes.

The new approach focuses on correcting abnormal activation of circuits in the lumbar spinal cord, a region that hosts all the neurons that control activation of the leg muscles used for walking.

The stimulating device is placed on the lumbar region of the spinal cord, which sends messages to leg muscles. It is wired to a small impulse generator implanted under the skin of the abdomen. Sensors placed in shoes align the stimulation to the patient’s movement.

The system can detect the beginning of a movement, immediately activate the appropriate electrode, and so facilitate the necessary movement, be that leg flexion, extension, or propulsion, said Dr. Moraud. “This allows for increased walking symmetry, reinforced balance, and increased length of steps.”

The concept of this neuroprosthesis is similar to that used to allow patients with a spinal cord injury (SCI) to walk. But unlike patients with SCI, those with PD can move their legs, indicating that there is a descending command from the brain that needs to interact with the stimulation of the spinal cord, and patients with PD can feel the stimulation.

“Both these elements imply that amplitudes of stimulation need to be much lower in PD than SCI, and that stimulation needs to be fully personalized in PD to synergistically interact with the descending commands from the brain.”

After fine-tuning this new neuroprosthesis in animal models, researchers implanted the device in a 62-year-old man with a 30-year history of PD who presented with severe gait impairments, including marked gait asymmetry, reduced stride length, and balance problems.

Gait restored to near normal

The patient had frequent freezing-of-gait episodes when turning and passing through narrow paths, which led to multiple falls a day. This was despite being treated with DBS and dopaminergic replacement therapies.

But after getting used to the neuroprosthesis, the patient now walks with a gait akin to that of people without PD.

“Our experience in the preclinical animal models and this first patient is that gait can be restored to an almost healthy level, but this, of course, may vary across patients, depending on the severity of their disease progression, and their other motor deficits,” said Dr. Moraud.

When the neuroprosthesis is turned on, freezing of gait nearly vanishes, both with and without DBS.

In addition, the neuroprosthesis augmented the impact of the patient’s rehabilitation program, which involved a variety of regular exercises, including walking on basic and complex terrains, navigating outdoors in community settings, balance training, and basic physical therapy.

Frequent use of the neuroprosthesis during gait rehabilitation also translated into “highly improved” quality of life as reported by the patient (and his wife), said Dr. Moraud.

The patient has now been using the neuroprosthesis about 8 hours a day for nearly 2 years, only switching it off when sitting for long periods of time or while sleeping.

“He regained the capacity to walk in complex or crowded environments such as shops, airports, or his own home, without falling,” said Dr. Moraud. “He went from falling five to six times per day to one or two [falls] every couple of weeks. He’s also much more confident. He can walk for many miles, run, and go on holidays, without the constant fear of falling and having related injuries.”

Dr. Moraud stressed that the device does not replace DBS, which is a “key therapy” that addresses other deficits in PD, such as rigidity or slowness of movement. “What we propose here is a fully complementary approach for the gait problems that are not well addressed by DBS.”

One of the next steps will be to evaluate the efficacy of this approach across a wider spectrum of patient profiles to fully define the best responders, said Dr. Moraud.

A ‘tour de force’

In a comment, Michael S. Okun, MD, director of the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, and medical director of the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the researchers used “a smarter device” than past approaches that failed to adequately address progressive walking challenges of patients with PD.

Although it’s “tempting to get excited” about the findings, it’s important to consider that the study included only one human subject and did not target circuits for both walking and balance, said Dr. Okun. “It’s possible that even if future studies revealed a benefit for walking, the device may or may not address falling.”

In an accompanying editorial, Aviv Mizrahi-Kliger, MD, PhD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, and Karunesh Ganguly, MD, PhD, Neurology and Rehabilitation Service, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, called the study an “impressive tour de force,” with data from the nonhuman primate model and the individual with PD “jointly” indicating that epidural electrical stimulation (EES) “is a very promising treatment for several aspects of gait, posture and balance impairments in PD.”

But although the effect in the single patient “is quite impressive,” the “next crucial step” is to test this approach in a larger cohort of patients, they said.

They noted the nonhuman model does not exhibit freezing of gait, “which precluded the ability to corroborate or further study the role of EES in alleviating this symptom of PD in an animal model.”

In addition, stimulation parameters in the patient with PD “had to rely on estimated normal activity patterns, owing to the inability to measure pre-disease patterns at the individual level,” they wrote.

The study received funding from the Defitech Foundation, ONWARD Medical, CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Parkinson Schweiz Foundation, European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (NeuWalk), European Research Council, Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, Bertarelli Foundation, and Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Moraud and other study authors hold various patents or applications in relation to the present work. Dr. Mizrahi-Kliger has no relevant conflicts of interest; Dr. Ganguly has a patent for modulation of sensory inputs to improve motor recovery from stroke and has been a consultant to Cala Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Atrial fibrillation linked to dementia, especially when diagnosed before age 65 years

TOPLINE:

Adults with atrial fibrillation (AFib) are at increased risk for dementia, especially when AFib occurs before age 65 years, new research shows. Investigators note the findings highlight the importance of monitoring cognitive function in adults with AF.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective, population-based cohort study leveraged data from 433,746 UK Biobank participants (55% women), including 30,601 with AFib, who were followed for a median of 12.6 years

- Incident cases of dementia were determined through linkage from multiple databases.

- Cox proportional hazards models and propensity score matching were used to estimate the association between age at onset of AFib and incident dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up, new-onset dementia occurred in 5,898 participants (2,546 with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] and 1,211 with vascular dementia [VD]), of which, 1,031 had AFib (350 with AD; 320 with VD).

- Compared with participants without AFib, those with AFib had a 42% higher risk for all-cause dementia (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.42; P < .001) and more than double the risk for VD (aHR, 2.06; P < .001), but no significantly higher risk for AD.

- Younger age at AFib onset was associated with higher risks for all-cause dementia, AD and VD, with aHRs per 10-year decrease of 1.23, 1.27, and 1.35, respectively (P < .001 for all).

- After propensity score matching, AFib onset before age 65 years had the highest risk for all-cause dementia (aHR, 1.82; P < .001), followed by AF onset at age 65-74 years (aHR, 1.47; P < .001). Similar results were seen in AD and VD.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that careful monitoring of cognitive function for patients with a younger [AFib] onset age, particularly those diagnosed with [AFib] before age 65 years, is important to attenuate the risk of subsequent dementia,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Wenya Zhang, with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the study was observational, a cause-effect relationship cannot be established. Despite the adjustment for many underlying confounders, residual unidentified confounders may still exist. The vast majority of participants were White. The analyses did not consider the potential impact of effective treatment of AFib on dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with atrial fibrillation (AFib) are at increased risk for dementia, especially when AFib occurs before age 65 years, new research shows. Investigators note the findings highlight the importance of monitoring cognitive function in adults with AF.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective, population-based cohort study leveraged data from 433,746 UK Biobank participants (55% women), including 30,601 with AFib, who were followed for a median of 12.6 years

- Incident cases of dementia were determined through linkage from multiple databases.

- Cox proportional hazards models and propensity score matching were used to estimate the association between age at onset of AFib and incident dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up, new-onset dementia occurred in 5,898 participants (2,546 with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] and 1,211 with vascular dementia [VD]), of which, 1,031 had AFib (350 with AD; 320 with VD).

- Compared with participants without AFib, those with AFib had a 42% higher risk for all-cause dementia (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.42; P < .001) and more than double the risk for VD (aHR, 2.06; P < .001), but no significantly higher risk for AD.

- Younger age at AFib onset was associated with higher risks for all-cause dementia, AD and VD, with aHRs per 10-year decrease of 1.23, 1.27, and 1.35, respectively (P < .001 for all).

- After propensity score matching, AFib onset before age 65 years had the highest risk for all-cause dementia (aHR, 1.82; P < .001), followed by AF onset at age 65-74 years (aHR, 1.47; P < .001). Similar results were seen in AD and VD.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that careful monitoring of cognitive function for patients with a younger [AFib] onset age, particularly those diagnosed with [AFib] before age 65 years, is important to attenuate the risk of subsequent dementia,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Wenya Zhang, with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the study was observational, a cause-effect relationship cannot be established. Despite the adjustment for many underlying confounders, residual unidentified confounders may still exist. The vast majority of participants were White. The analyses did not consider the potential impact of effective treatment of AFib on dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with atrial fibrillation (AFib) are at increased risk for dementia, especially when AFib occurs before age 65 years, new research shows. Investigators note the findings highlight the importance of monitoring cognitive function in adults with AF.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective, population-based cohort study leveraged data from 433,746 UK Biobank participants (55% women), including 30,601 with AFib, who were followed for a median of 12.6 years

- Incident cases of dementia were determined through linkage from multiple databases.

- Cox proportional hazards models and propensity score matching were used to estimate the association between age at onset of AFib and incident dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up, new-onset dementia occurred in 5,898 participants (2,546 with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] and 1,211 with vascular dementia [VD]), of which, 1,031 had AFib (350 with AD; 320 with VD).

- Compared with participants without AFib, those with AFib had a 42% higher risk for all-cause dementia (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.42; P < .001) and more than double the risk for VD (aHR, 2.06; P < .001), but no significantly higher risk for AD.

- Younger age at AFib onset was associated with higher risks for all-cause dementia, AD and VD, with aHRs per 10-year decrease of 1.23, 1.27, and 1.35, respectively (P < .001 for all).

- After propensity score matching, AFib onset before age 65 years had the highest risk for all-cause dementia (aHR, 1.82; P < .001), followed by AF onset at age 65-74 years (aHR, 1.47; P < .001). Similar results were seen in AD and VD.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that careful monitoring of cognitive function for patients with a younger [AFib] onset age, particularly those diagnosed with [AFib] before age 65 years, is important to attenuate the risk of subsequent dementia,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Wenya Zhang, with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the study was observational, a cause-effect relationship cannot be established. Despite the adjustment for many underlying confounders, residual unidentified confounders may still exist. The vast majority of participants were White. The analyses did not consider the potential impact of effective treatment of AFib on dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Blood test could predict future disability in MS

a new study suggests.

Rising NfL levels are a known indicator of neuroaxonal injury and correlate with MS disease activity. Levels rise in the presence of an MS relapse or MRI activity and fall following treatment with disease-modifying therapies. But the link between NfL levels and worsening disability was less understood.

This new analysis of NfL in two large MS cohorts found that elevated levels of the neuronal protein at baseline were associated with large increases in future disability risk, even in patients with no clinical relapse.

“This rising of NfL up to 2 years before signs of disability worsening represents the window when interventions may prevent worsening,” lead investigator Ahmed Abdelhak, MD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, said in a press release.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Early warning system?

The study included data on 1,899 patients with nearly 13,000 patient visits from two observational, long-term, real-world cohorts: the U.S.-based Expression, Proteomics, Imaging, Clinical (EPIC) study (n = 609 patients), and the Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Cohort trial (SMSC; n = 1,290 patients).

Investigators analyzed longitudinal serum NfL measurements in conjunction with clinical disability worsening, defined as 6 months or more of increased impairment as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Researchers also assessed the temporal association between NfL measurements and the risk of increased disability and distinguished between disability with and without relapse.

Worsening disability was reported in 227 patients in the EPIC group and 435 in the SMSC trial.

Elevated NfL at baseline was associated with a 70% higher risk for worsening disability with relapse about 11 months later in the SMSC study (hazard ratio, 1.70; P = .02). In the EPIC trial, there was trend toward a 91% higher risk for worsening disability with relapse at 12.6 months, although the findings did not meet statistical significance (HR, 1.91; P = .07).

The risk of future disability progression independent of clinical relapse was 40% higher in those with high NfL at baseline in the EPIC study 12 months after baseline (HR, 1.40; P = .02) and 49% higher in the SMSC trial 21 months later (HR, 1.49; P < .001).

The early elevation of NfL levels suggests a slower degradation of nerve cells and could be a possible early warning system of future progression of disability, allowing time for interventions that could slow or even halt further disability.

“Monitoring NfL levels might be able to detect disease activity with higher sensitivity than clinical exam or conventional imaging,” senior author Jens Kuhle, MD, PhD, leader of the Swiss cohort and head of the Multiple Sclerosis Center at University Hospital and University of Basel, said in a statement.

Challenges for clinicians

Commenting on the findings, Robert Fox, MD, staff neurologist at the Mellen Center for MS and vice chair for research, Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, said that, while there is a clinical test to measure NfL levels, incorporating that test into standard of care isn’t straightforward.

“The challenge for the practicing clinician is to translate these population-level studies to individual patient management decisions,” said Dr. Fox, who was not a part of the study.

“The published prediction curves corrected for age, sex, disease course, disease-modifying treatment, relapse within the past 90 days, and current disability status, the combination of which makes it rather challenging to calculate and interpret adjusted z score NfL levels in routine practice and then use it in clinical decision-making.”

The investigators said the study underscores the importance of NfL as an MS biomarker and “points to the existence of different windows of dynamic central nervous system pathology” that precedes worsening disability with or without relapse. But there may be a simpler explanation, Dr. Fox suggested.

“We know MRI activity occurs 5-10 times more frequently than relapses, and we know that MRI activity is associated with both NfL increases and future disability progression,” Dr. Fox said. “It is quite likely that the elevations in NfL seen here are reflective of new MRI disease activity, which frequently is seen without symptoms of an MS relapse,” he said

The study was funded by the Westridge Foundation, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the Fishman Family, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Valhalla Foundation. Dr. Abdelhak reported receiving grants from the German Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Weill Institute for Neurosciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Kuhle has received grants from Swiss MS Society, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the Progressive MS Alliance, Biogen, Merck, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Octave Bioscience, Roche, Sanofi, Alnylam, Bayer, Immunic, Quanterix, Neurogenesis, Stata DX, and the University of Basel outside the submitted work. Dr. Fox reported receiving consulting fees from Siemens and Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

a new study suggests.

Rising NfL levels are a known indicator of neuroaxonal injury and correlate with MS disease activity. Levels rise in the presence of an MS relapse or MRI activity and fall following treatment with disease-modifying therapies. But the link between NfL levels and worsening disability was less understood.

This new analysis of NfL in two large MS cohorts found that elevated levels of the neuronal protein at baseline were associated with large increases in future disability risk, even in patients with no clinical relapse.

“This rising of NfL up to 2 years before signs of disability worsening represents the window when interventions may prevent worsening,” lead investigator Ahmed Abdelhak, MD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, said in a press release.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Early warning system?

The study included data on 1,899 patients with nearly 13,000 patient visits from two observational, long-term, real-world cohorts: the U.S.-based Expression, Proteomics, Imaging, Clinical (EPIC) study (n = 609 patients), and the Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Cohort trial (SMSC; n = 1,290 patients).

Investigators analyzed longitudinal serum NfL measurements in conjunction with clinical disability worsening, defined as 6 months or more of increased impairment as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Researchers also assessed the temporal association between NfL measurements and the risk of increased disability and distinguished between disability with and without relapse.

Worsening disability was reported in 227 patients in the EPIC group and 435 in the SMSC trial.

Elevated NfL at baseline was associated with a 70% higher risk for worsening disability with relapse about 11 months later in the SMSC study (hazard ratio, 1.70; P = .02). In the EPIC trial, there was trend toward a 91% higher risk for worsening disability with relapse at 12.6 months, although the findings did not meet statistical significance (HR, 1.91; P = .07).

The risk of future disability progression independent of clinical relapse was 40% higher in those with high NfL at baseline in the EPIC study 12 months after baseline (HR, 1.40; P = .02) and 49% higher in the SMSC trial 21 months later (HR, 1.49; P < .001).

The early elevation of NfL levels suggests a slower degradation of nerve cells and could be a possible early warning system of future progression of disability, allowing time for interventions that could slow or even halt further disability.

“Monitoring NfL levels might be able to detect disease activity with higher sensitivity than clinical exam or conventional imaging,” senior author Jens Kuhle, MD, PhD, leader of the Swiss cohort and head of the Multiple Sclerosis Center at University Hospital and University of Basel, said in a statement.

Challenges for clinicians

Commenting on the findings, Robert Fox, MD, staff neurologist at the Mellen Center for MS and vice chair for research, Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, said that, while there is a clinical test to measure NfL levels, incorporating that test into standard of care isn’t straightforward.

“The challenge for the practicing clinician is to translate these population-level studies to individual patient management decisions,” said Dr. Fox, who was not a part of the study.

“The published prediction curves corrected for age, sex, disease course, disease-modifying treatment, relapse within the past 90 days, and current disability status, the combination of which makes it rather challenging to calculate and interpret adjusted z score NfL levels in routine practice and then use it in clinical decision-making.”

The investigators said the study underscores the importance of NfL as an MS biomarker and “points to the existence of different windows of dynamic central nervous system pathology” that precedes worsening disability with or without relapse. But there may be a simpler explanation, Dr. Fox suggested.

“We know MRI activity occurs 5-10 times more frequently than relapses, and we know that MRI activity is associated with both NfL increases and future disability progression,” Dr. Fox said. “It is quite likely that the elevations in NfL seen here are reflective of new MRI disease activity, which frequently is seen without symptoms of an MS relapse,” he said

The study was funded by the Westridge Foundation, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the Fishman Family, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Valhalla Foundation. Dr. Abdelhak reported receiving grants from the German Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Weill Institute for Neurosciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Kuhle has received grants from Swiss MS Society, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the Progressive MS Alliance, Biogen, Merck, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Octave Bioscience, Roche, Sanofi, Alnylam, Bayer, Immunic, Quanterix, Neurogenesis, Stata DX, and the University of Basel outside the submitted work. Dr. Fox reported receiving consulting fees from Siemens and Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

a new study suggests.

Rising NfL levels are a known indicator of neuroaxonal injury and correlate with MS disease activity. Levels rise in the presence of an MS relapse or MRI activity and fall following treatment with disease-modifying therapies. But the link between NfL levels and worsening disability was less understood.

This new analysis of NfL in two large MS cohorts found that elevated levels of the neuronal protein at baseline were associated with large increases in future disability risk, even in patients with no clinical relapse.

“This rising of NfL up to 2 years before signs of disability worsening represents the window when interventions may prevent worsening,” lead investigator Ahmed Abdelhak, MD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, said in a press release.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Early warning system?

The study included data on 1,899 patients with nearly 13,000 patient visits from two observational, long-term, real-world cohorts: the U.S.-based Expression, Proteomics, Imaging, Clinical (EPIC) study (n = 609 patients), and the Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Cohort trial (SMSC; n = 1,290 patients).

Investigators analyzed longitudinal serum NfL measurements in conjunction with clinical disability worsening, defined as 6 months or more of increased impairment as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Researchers also assessed the temporal association between NfL measurements and the risk of increased disability and distinguished between disability with and without relapse.

Worsening disability was reported in 227 patients in the EPIC group and 435 in the SMSC trial.

Elevated NfL at baseline was associated with a 70% higher risk for worsening disability with relapse about 11 months later in the SMSC study (hazard ratio, 1.70; P = .02). In the EPIC trial, there was trend toward a 91% higher risk for worsening disability with relapse at 12.6 months, although the findings did not meet statistical significance (HR, 1.91; P = .07).

The risk of future disability progression independent of clinical relapse was 40% higher in those with high NfL at baseline in the EPIC study 12 months after baseline (HR, 1.40; P = .02) and 49% higher in the SMSC trial 21 months later (HR, 1.49; P < .001).

The early elevation of NfL levels suggests a slower degradation of nerve cells and could be a possible early warning system of future progression of disability, allowing time for interventions that could slow or even halt further disability.

“Monitoring NfL levels might be able to detect disease activity with higher sensitivity than clinical exam or conventional imaging,” senior author Jens Kuhle, MD, PhD, leader of the Swiss cohort and head of the Multiple Sclerosis Center at University Hospital and University of Basel, said in a statement.

Challenges for clinicians

Commenting on the findings, Robert Fox, MD, staff neurologist at the Mellen Center for MS and vice chair for research, Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, said that, while there is a clinical test to measure NfL levels, incorporating that test into standard of care isn’t straightforward.

“The challenge for the practicing clinician is to translate these population-level studies to individual patient management decisions,” said Dr. Fox, who was not a part of the study.

“The published prediction curves corrected for age, sex, disease course, disease-modifying treatment, relapse within the past 90 days, and current disability status, the combination of which makes it rather challenging to calculate and interpret adjusted z score NfL levels in routine practice and then use it in clinical decision-making.”

The investigators said the study underscores the importance of NfL as an MS biomarker and “points to the existence of different windows of dynamic central nervous system pathology” that precedes worsening disability with or without relapse. But there may be a simpler explanation, Dr. Fox suggested.

“We know MRI activity occurs 5-10 times more frequently than relapses, and we know that MRI activity is associated with both NfL increases and future disability progression,” Dr. Fox said. “It is quite likely that the elevations in NfL seen here are reflective of new MRI disease activity, which frequently is seen without symptoms of an MS relapse,” he said

The study was funded by the Westridge Foundation, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the Fishman Family, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Valhalla Foundation. Dr. Abdelhak reported receiving grants from the German Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Weill Institute for Neurosciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Kuhle has received grants from Swiss MS Society, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the Progressive MS Alliance, Biogen, Merck, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Octave Bioscience, Roche, Sanofi, Alnylam, Bayer, Immunic, Quanterix, Neurogenesis, Stata DX, and the University of Basel outside the submitted work. Dr. Fox reported receiving consulting fees from Siemens and Roche.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Short steroid taper tested with tocilizumab for giant cell arteritis

TOPLINE:

A combination of tocilizumab (Actemra) and 8 weeks of tapering prednisone was effective for inducing and maintaining disease remission in adults with giant cell arteritis (GCA).

METHODOLOGY:

- In a single-center, single-arm, open-label pilot study, 30 adults (mean age, 73.7 years) with GCA received 162 mg of tocilizumab as a subcutaneous injection once a week for 52 weeks, plus prednisone starting between 20 mg and 60 mg with a prespecified 8-week taper off the glucocorticoid.

- Patients had to be at least 50 years of age and could have either new-onset (diagnosis within 6 weeks of baseline) or relapsing disease (diagnosis > 6 weeks from baseline).

- The primary endpoint was sustained, prednisone-free remission at 52 weeks, defined by an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of less than 40 mm/h, C-reactive protein level less than 10 mg/L, and adherence to the prednisone taper; secondary endpoints included the proportions of patients in remission and relapse, cumulative prednisone dose, and glucocorticoid toxicity.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 52 weeks, 23 patients (77%) met the criteria for sustained remission after weaning off prednisone within 8 weeks of starting tocilizumab; 7 relapsed after a mean of 15.8 weeks.

- Of the patients who relapsed, six underwent a second prednisone taper for 8 weeks with a mean initial daily dose of 32.1 mg, four regained and maintained remission, and two experienced a second relapse and withdrew from the study.

- The mean cumulative prednisone dose at week 52 was 1,051.5 mg for responders and 1,673.1 mg for nonresponders.

- All 30 patients had at least one adverse event; four patients had a serious adverse event likely related to tocilizumab, prednisone, or both.

IN PRACTICE:

Studies such as this “are highly valuable as proof of concept, but of course cannot be definitive guides to treatment decisions without a comparator group,” according to authors of an editorial accompanying the study.

SOURCE:

The study, by Sebastian Unizony, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues, was published in The Lancet Rheumatology .

LIMITATIONS:

The small size and open-label design with no control group were limiting factors; more research is needed to confirm the findings before this treatment strategy can be recommended for clinical practice.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Genentech. Two authors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies outside of this report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A combination of tocilizumab (Actemra) and 8 weeks of tapering prednisone was effective for inducing and maintaining disease remission in adults with giant cell arteritis (GCA).

METHODOLOGY:

- In a single-center, single-arm, open-label pilot study, 30 adults (mean age, 73.7 years) with GCA received 162 mg of tocilizumab as a subcutaneous injection once a week for 52 weeks, plus prednisone starting between 20 mg and 60 mg with a prespecified 8-week taper off the glucocorticoid.

- Patients had to be at least 50 years of age and could have either new-onset (diagnosis within 6 weeks of baseline) or relapsing disease (diagnosis > 6 weeks from baseline).

- The primary endpoint was sustained, prednisone-free remission at 52 weeks, defined by an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of less than 40 mm/h, C-reactive protein level less than 10 mg/L, and adherence to the prednisone taper; secondary endpoints included the proportions of patients in remission and relapse, cumulative prednisone dose, and glucocorticoid toxicity.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 52 weeks, 23 patients (77%) met the criteria for sustained remission after weaning off prednisone within 8 weeks of starting tocilizumab; 7 relapsed after a mean of 15.8 weeks.

- Of the patients who relapsed, six underwent a second prednisone taper for 8 weeks with a mean initial daily dose of 32.1 mg, four regained and maintained remission, and two experienced a second relapse and withdrew from the study.

- The mean cumulative prednisone dose at week 52 was 1,051.5 mg for responders and 1,673.1 mg for nonresponders.

- All 30 patients had at least one adverse event; four patients had a serious adverse event likely related to tocilizumab, prednisone, or both.

IN PRACTICE:

Studies such as this “are highly valuable as proof of concept, but of course cannot be definitive guides to treatment decisions without a comparator group,” according to authors of an editorial accompanying the study.

SOURCE:

The study, by Sebastian Unizony, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues, was published in The Lancet Rheumatology .

LIMITATIONS:

The small size and open-label design with no control group were limiting factors; more research is needed to confirm the findings before this treatment strategy can be recommended for clinical practice.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Genentech. Two authors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies outside of this report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A combination of tocilizumab (Actemra) and 8 weeks of tapering prednisone was effective for inducing and maintaining disease remission in adults with giant cell arteritis (GCA).

METHODOLOGY:

- In a single-center, single-arm, open-label pilot study, 30 adults (mean age, 73.7 years) with GCA received 162 mg of tocilizumab as a subcutaneous injection once a week for 52 weeks, plus prednisone starting between 20 mg and 60 mg with a prespecified 8-week taper off the glucocorticoid.

- Patients had to be at least 50 years of age and could have either new-onset (diagnosis within 6 weeks of baseline) or relapsing disease (diagnosis > 6 weeks from baseline).

- The primary endpoint was sustained, prednisone-free remission at 52 weeks, defined by an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of less than 40 mm/h, C-reactive protein level less than 10 mg/L, and adherence to the prednisone taper; secondary endpoints included the proportions of patients in remission and relapse, cumulative prednisone dose, and glucocorticoid toxicity.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 52 weeks, 23 patients (77%) met the criteria for sustained remission after weaning off prednisone within 8 weeks of starting tocilizumab; 7 relapsed after a mean of 15.8 weeks.

- Of the patients who relapsed, six underwent a second prednisone taper for 8 weeks with a mean initial daily dose of 32.1 mg, four regained and maintained remission, and two experienced a second relapse and withdrew from the study.

- The mean cumulative prednisone dose at week 52 was 1,051.5 mg for responders and 1,673.1 mg for nonresponders.

- All 30 patients had at least one adverse event; four patients had a serious adverse event likely related to tocilizumab, prednisone, or both.

IN PRACTICE:

Studies such as this “are highly valuable as proof of concept, but of course cannot be definitive guides to treatment decisions without a comparator group,” according to authors of an editorial accompanying the study.

SOURCE:

The study, by Sebastian Unizony, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues, was published in The Lancet Rheumatology .

LIMITATIONS:

The small size and open-label design with no control group were limiting factors; more research is needed to confirm the findings before this treatment strategy can be recommended for clinical practice.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Genentech. Two authors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies outside of this report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

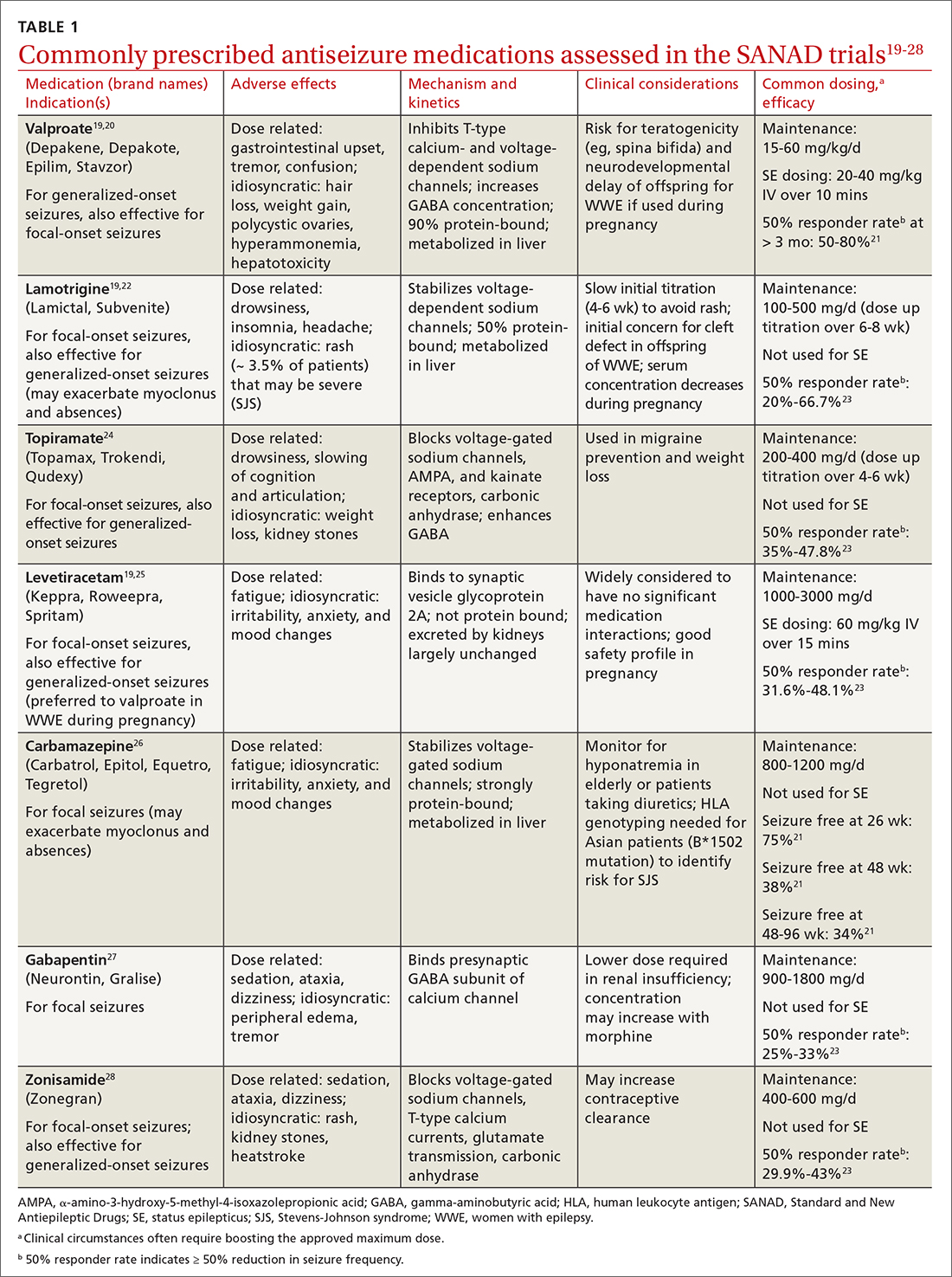

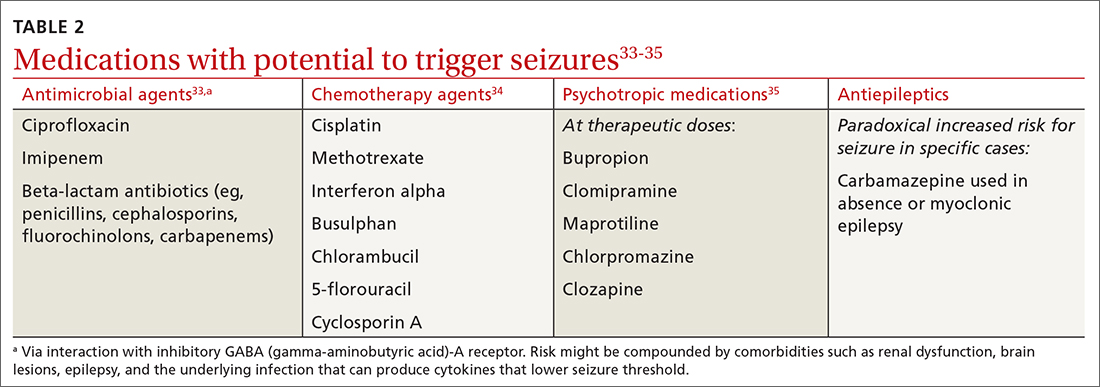

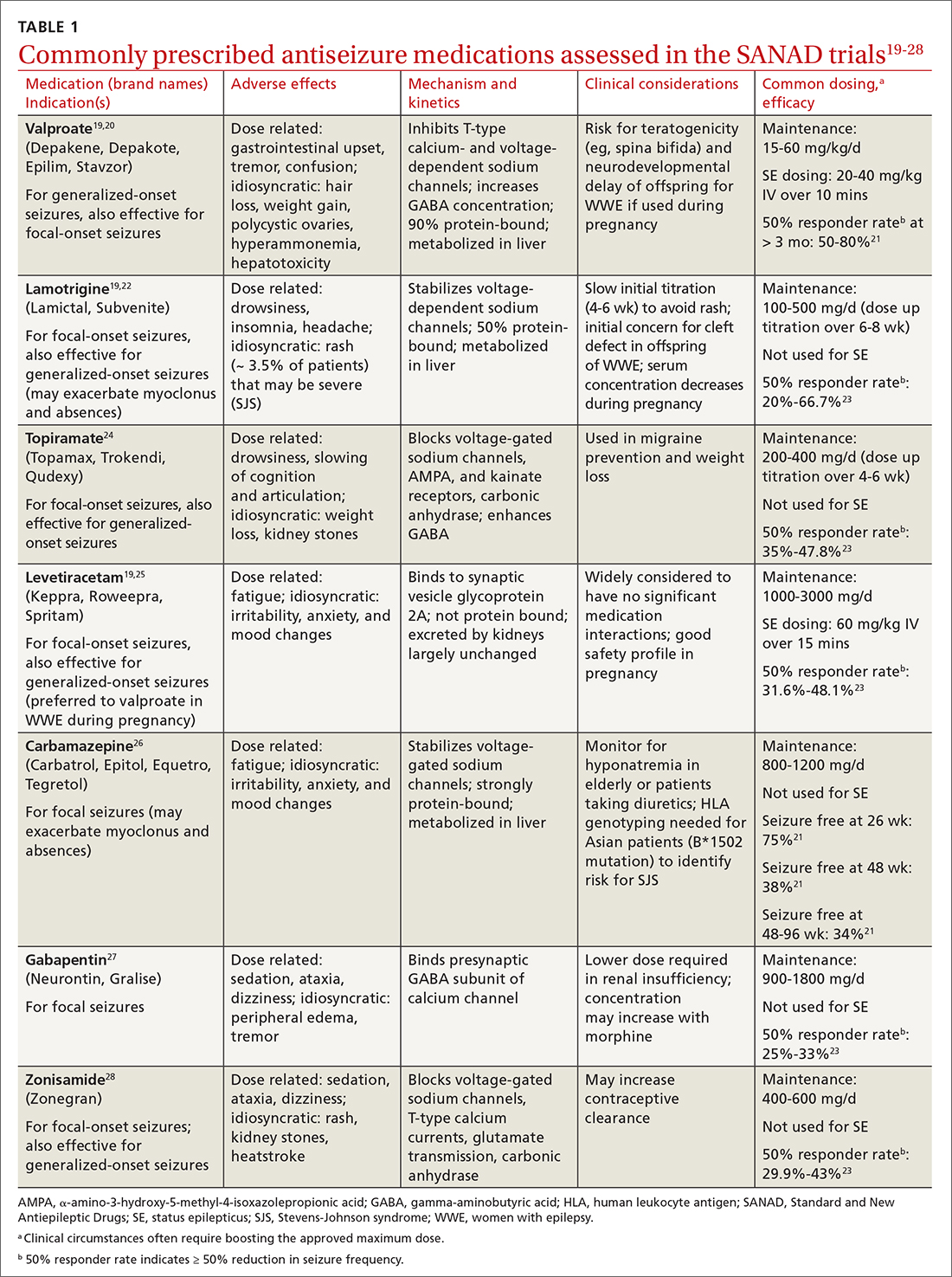

An FP’s guide to caring for patients with seizure and epilepsy

Managing first-time seizures and epilepsy often requires consultation with a neurologist or epileptologist for diagnosis and subsequent management, including when medical treatment fails or in determining whether patients may benefit from surgery. However, given the high prevalence of epilepsy and even higher incidence of a single seizure, family physicians contribute significantly to the management of these patients. The main issues are managing a first-time seizure, making the diagnosis, establishing a treatment plan, and exploring triggers and mitigating factors.

Seizure vs epilepsy

All patients with epilepsy experience seizures, but not every person who experiences a seizure has (or will develop) epilepsy. Nearly 10% of the population has one seizure during their lifetime, whereas the risk for epilepsy is just 3%.1 Therefore, a first-time seizure may not herald epilepsy, defined as repetitive (≥ 2) unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart.2 Seizures can be provoked (acute symptomatic) or unprovoked; a clear distinction between these 2 occurrences—as well as between single and recurrent seizures—is critical for proper management. A close look at the circumstances of a first-time seizure is imperative to define the nature of the event and the possibility of further seizures before devising a treatment plan.

Provoked seizures are due to an acute brain insult such as toxic-metabolic disorders, concussion, alcohol withdrawal, an adverse effect of a medication or its withdrawal, or photic stimulation presumably by disrupting the brain’s metabolic homeostasis or integrity. The key factor is that provoked seizures always happen in close temporal association with an acute insult. A single provoked seizure happens each year in 29 to 39 individuals per 100,000.3 While these seizures typically occur singly, there is a small risk they may recur if the triggering insult persists or repeats.1 Therefore, more than 1 seizure per se may not indicate epilepsy.3

Unprovoked seizures reflect an underlying brain dysfunction. A single unprovoked seizure happens in 23 to 61 individuals per 100,000 per year, often in men in either younger or older age groups.3 Unprovoked seizures may occur only once or may recur (ie, evolve into epilepsy). The latter scenario happens in only about half of cases; the overall risk for a recurrent seizure within 2 years of a first seizure is estimated at 42% (24% to 65%, depending on the etiology and electroencephalogram [EEG] findings).4 More specifically, without treatment the relapse rate will be 36% at 1 year and 47% at 2 years.4 Further, a second unprovoked seizure, if untreated, would increase the risk for third and fourth seizures to 73% and 76%, respectively, within 4 years.3

Evaluating the first-time seizure

Ask the patient or observers about the circumstances of the event to differentiate provoked from unprovoked onset. For one thing, not all “spells” are seizures. The differential diagnoses may include syncope, psychogenic nonepileptic events, drug intoxication or withdrawal, migraine, panic attacks, sleep disorders (parasomnia), transient global amnesia, concussion, and transient ischemic attack. EEG, neuroimaging, and other relevant diagnostic tests often are needed (eg, electrocardiogram/echocardiogram/Holter monitoring to evaluate for syncope/cardiac arrhythmia). Clinically, syncopal episodes tend to be brief with rapid recovery and no confusion, speech problems, aura, or lateralizing signs such as hand posturing or lip smacking that are typical with focal seizures. However, cases of convulsive syncope can be challenging to assess without diagnostic tests.

True convulsive seizures do not have the variability in clinical signs seen with psychogenic nonepileptic events (eg, alternating body parts involved or direction of movements). Transient global amnesia is a rare condition with no established diagnostic test and is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, although bitemporal hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may appear 12 to 48 hours after the clinical episode.5 Blood work is needed in patients with medical issues treated with multiple medications to evaluate for metabolic derangements; otherwise, routine blood work provides minimal information in stable patients.

Region-specific causes. Neurocysticercosis is common in some regions, such as Latin America; therefore, attention should be paid to this aspect of patient history.

Continue to: Is it really a first-time seizure?

Is it really a first-time seizure? A “first,” usually dramatic, generalized tonic-clonic seizure that triggers the diagnostic work-up may not be the very first seizure. Evidence suggests that many patients have experienced prior undiagnosed seizures. Subtle prior events often missed include episodes of deja vu, transient feelings of fear or unusual smells, speech difficulties, staring spells, or myoclonic jerks.1 A routine EEG to record epileptiform discharges and a high-resolution brain MRI to rule out any intracranial pathology are indicated. However, if the EEG indicates a primary generalized (as opposed to focal-onset) epilepsy, a brain MRI may not be needed. If a routine EEG is unrevealing, long-term video-EEG monitoring may be needed to detect an abnormality.

Accuracy of EEG and MRI. Following a first unprovoked seizure, routine EEG to detect epileptiform discharges in adults has yielded a sensitivity of 17.3% and specificity of 94.7%. In evaluating children, these values are 57.8% and 69.6%, respectively.6 If results are equivocal, a 24-hour EEG can increase the likelihood of detecting epileptiform discharges to 89% of patients.7 Brain MRI may detect an abnormality in 12% to 14% of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy, and in up to 80% of those with recurrent seizures.8 In confirming hippocampus sclerosis, MRI has demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 86%.9

When to treat a first-time seizure. Available data and prediction models identify risk factors that would help determine whether to start an antiseizure medication after a first unprovoked seizure:

Epilepsy diagnosis

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) previously defined epilepsy as 2 unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart. However, a more recent ILAE task force modified this definition: even a single unprovoked seizure would be enough to diagnose epilepsy if there is high probability of further seizures—eg, in the presence of definitive epileptiform discharges on EEG or presence of a brain tumor or a remote brain insult on imaging, since such conditions induce an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures. 2 Also, a single unprovoked seizure is enough to diagnose epilepsy if it is part of an epileptic syndrome such as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Further, a time limit was added to the definition—ie, epilepsy is considered resolved if a patient remains seizure free for 10 years without use of antiseizure medications during the past 5 years. However, given the multitude of variables and evidence, the task force acknowledged the need for individualized considerations. 2

Seizure classification

Classification of seizure type is based on the site of seizure onset and its spread pattern—ie, focal, generalized, or unknown onset.

Continue to: Focal-onset seizures

Focal-onset seizures originate “within networks limited to one hemisphere,” although possibly in more than 1 region (ie, multifocal, and presence or absence of loss of awareness). 12 Focal seizures may then be further classified into “motor onset” or “nonmotor onset” (eg, autonomic, emotional, sensory). 2

Generalized seizures are those “originating at some point within, and rapidly engaging, bilaterally distributed networks.” 13 Unlike focal-onset seizures, generalized seizures are not classified based on awareness, as most generalized seizures involve loss of awareness (absence) or total loss of consciousness (generalized tonic-clonic). They are instead categorized based on the presence of motor vs nonmotor features (eg, tonic-clonic, myoclonic, atonic). Epilepsy classification is quite dynamic and constantly updated based on new genetic, electroencephalographic, and neuroimaging discoveries.

Treatment of epilepsy

Antiseizure medications