User login

AF tied to 45% increase in mild cognitive impairment

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- From over 4.3 million people in the UK primary electronic health record (EHR) database, researchers identified 233,833 (5.4%) with AF (mean age, 74.2 years) and randomly selected one age- and sex-matched control person without AF for each AF case patient.

- The primary outcome was incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

- The authors adjusted for age, sex, year at study entry, socioeconomic status, smoking, and a number of comorbid conditions.

- During a median of 5.3 years of follow-up, there were 4,269 incident MCI cases among both AF and non-AF patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with AF had a higher risk of MCI than that of those without AF (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-1.56).

- Besides AF, older age (risk ratio [RR], 1.08) and history of depression (RR, 1.44) were associated with greater risk of MCI, as were female sex, greater socioeconomic deprivation, stroke, and multimorbidity, including, for example, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral artery disease (all P < .001).

- Individuals with AF who received oral anticoagulants or amiodarone were not at increased risk of MCI, as was the case for those treated with digoxin.

- Individuals with AF and MCI were at greater risk of dementia (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.42). Sex, smoking, chronic kidney disease, and multi-comorbidity were among factors linked to elevated dementia risk.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings emphasize the association of multi-comorbidity and cardiovascular risk factors with development of MCI and progression to dementia in AF patients, the authors wrote. They noted that the data suggest combining anticoagulation and symptom and comorbidity management may prevent cognitive deterioration.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Sheng-Chia Chung, PhD, Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, and colleagues. It was published online Oct. 25, 2023, as a research letter in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Advances.

LIMITATIONS:

The EHR dataset may have lacked granularity and detail, and some risk factors or comorbidities may not have been measured. While those with AF receiving digoxin or amiodarone treatment had no higher risk of MCI than their non-AF peers, the study’s observational design and very wide confidence intervals for these subgroups prevent making solid inferences about causality or a potential protective role of these drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chung is supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Author Rui Providencia, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, is supported by the University College London British Heart Foundation and NIHR. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- From over 4.3 million people in the UK primary electronic health record (EHR) database, researchers identified 233,833 (5.4%) with AF (mean age, 74.2 years) and randomly selected one age- and sex-matched control person without AF for each AF case patient.

- The primary outcome was incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

- The authors adjusted for age, sex, year at study entry, socioeconomic status, smoking, and a number of comorbid conditions.

- During a median of 5.3 years of follow-up, there were 4,269 incident MCI cases among both AF and non-AF patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with AF had a higher risk of MCI than that of those without AF (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-1.56).

- Besides AF, older age (risk ratio [RR], 1.08) and history of depression (RR, 1.44) were associated with greater risk of MCI, as were female sex, greater socioeconomic deprivation, stroke, and multimorbidity, including, for example, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral artery disease (all P < .001).

- Individuals with AF who received oral anticoagulants or amiodarone were not at increased risk of MCI, as was the case for those treated with digoxin.

- Individuals with AF and MCI were at greater risk of dementia (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.42). Sex, smoking, chronic kidney disease, and multi-comorbidity were among factors linked to elevated dementia risk.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings emphasize the association of multi-comorbidity and cardiovascular risk factors with development of MCI and progression to dementia in AF patients, the authors wrote. They noted that the data suggest combining anticoagulation and symptom and comorbidity management may prevent cognitive deterioration.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Sheng-Chia Chung, PhD, Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, and colleagues. It was published online Oct. 25, 2023, as a research letter in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Advances.

LIMITATIONS:

The EHR dataset may have lacked granularity and detail, and some risk factors or comorbidities may not have been measured. While those with AF receiving digoxin or amiodarone treatment had no higher risk of MCI than their non-AF peers, the study’s observational design and very wide confidence intervals for these subgroups prevent making solid inferences about causality or a potential protective role of these drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chung is supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Author Rui Providencia, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, is supported by the University College London British Heart Foundation and NIHR. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- From over 4.3 million people in the UK primary electronic health record (EHR) database, researchers identified 233,833 (5.4%) with AF (mean age, 74.2 years) and randomly selected one age- and sex-matched control person without AF for each AF case patient.

- The primary outcome was incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

- The authors adjusted for age, sex, year at study entry, socioeconomic status, smoking, and a number of comorbid conditions.

- During a median of 5.3 years of follow-up, there were 4,269 incident MCI cases among both AF and non-AF patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with AF had a higher risk of MCI than that of those without AF (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-1.56).

- Besides AF, older age (risk ratio [RR], 1.08) and history of depression (RR, 1.44) were associated with greater risk of MCI, as were female sex, greater socioeconomic deprivation, stroke, and multimorbidity, including, for example, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral artery disease (all P < .001).

- Individuals with AF who received oral anticoagulants or amiodarone were not at increased risk of MCI, as was the case for those treated with digoxin.

- Individuals with AF and MCI were at greater risk of dementia (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.42). Sex, smoking, chronic kidney disease, and multi-comorbidity were among factors linked to elevated dementia risk.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings emphasize the association of multi-comorbidity and cardiovascular risk factors with development of MCI and progression to dementia in AF patients, the authors wrote. They noted that the data suggest combining anticoagulation and symptom and comorbidity management may prevent cognitive deterioration.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Sheng-Chia Chung, PhD, Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, and colleagues. It was published online Oct. 25, 2023, as a research letter in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Advances.

LIMITATIONS:

The EHR dataset may have lacked granularity and detail, and some risk factors or comorbidities may not have been measured. While those with AF receiving digoxin or amiodarone treatment had no higher risk of MCI than their non-AF peers, the study’s observational design and very wide confidence intervals for these subgroups prevent making solid inferences about causality or a potential protective role of these drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chung is supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Author Rui Providencia, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, is supported by the University College London British Heart Foundation and NIHR. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nightmare on CIL Street: A Simulation Series to Increase Confidence and Skill in Responding to Clinical Emergencies

The Central Texas Veteran’s Health Care System (CTVHCS) in Temple, Texas, is a 189-bed teaching hospital. CTVHCS opened the Center for Innovation and Learning (CIL) in 2022. The CIL has about 279 m2 of simulation space that includes high- and low-fidelity simulation equipment and multiple laboratories, which can be used to simulate inpatient and outpatient settings. The CIL high-fidelity manikins and environment allow learners to be immersed in the simulation for maximum realism. Computer and video systems provide clear viewing of training, which allows for more in-depth debriefing and learning. CIL simulation training is used by CTVHCS staff, medical residents, and medical and physician assistant students.

The utility of technology in medical education is rapidly evolving. As noted in many studies, simulation creates an environment that can imitate real patients in the format of a lifelike manikin, anatomic regions stations, clinical tasks, and many real-life circumstances.1 Task trainers for procedure simulation have been widely used and studied. A 2020 study noted that simulation training is effective for developing procedural skills in surgery and prevents the decay of surgical skills.2

In reviewing health care education curriculums, we noted that most of the rapid response situations are learned through active patient experiences. Rapid responses are managed by the intensive care unit and primary care teams during the day but at night are run primarily by the postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) night resident and intern. Knowing these logistics and current studies, we decided to build a rapid response simulation curriculum to improve preparedness for PGY1 residents, medical students, and physician assistant students.

Curriculum Planning

Planning the simulation curriculum began with the CTVHCS internal medicine chief resident and registered nurse (RN) educator. CTVHCS data were reviewed to identify the 3 most common rapid response calls from the past 3 years; research on the most common systems affected by rapid responses also was evaluated.

A 2019 study by Lyons and colleagues evaluated 402,023 rapid response activations across 360 hospitals and found that respiratory scenarios made up 38% and cardiac scenarios made up 37%.3 In addition, the CTVHCS has limited support in stroke neurology. Therefore, the internal medicine chief resident and RN educator decided to run 3 evolving rapid response scenarios per session that included cardiac, respiratory, and neurological scenarios. Capabilities and limitations of different high-fidelity manikins were discussed to identify and use the most appropriate simulator for each situation. Objectives that met both general medicine and site-specific education were discussed, and the program was formulated.

Program Description

Nightmare on CIL Street is a simulation-based program designed for new internal medicine residents and students to encounter difficult situations (late at night, on call, or when resources are limited; ie, weekends/holidays) in a controlled simulation environment. During the simulation, learners will be unable to transfer the patient and no additional help is available. Each learner must determine a differential diagnosis and make appropriate medical interventions with only the assistance of a nurse. Scenarios are derived from common rapid response team calls and low-volume/high-impact situations where clinical decisions must be made quickly to ensure the best patient outcomes. High-fidelity manikins that have abilities to respond to questions, simulate breathing, reproduce pathological heart and breath sounds and more are used to create a realistic patient environment.

This program aligns with 2 national Veterans Health Administration priorities: (1) connect veterans to the soonest and best care; and (2) accelerate the Veterans Health Administration journey to be a high-reliability organization (sensitivity to operations, preoccupation with failure, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise). Nightmare on CIL Street has 3 clinical episodes: 2 cardiac (A Tell-Tale Heart), respiratory (Don’t Breathe), and neurologic (Brain Scan). Additional clinical episodes will be added based on learner feedback and assessed need.

Each simulation event encompassed all 3 episodes that an individual or a team of 2 learners rotate through in a round-robin fashion. The overarching theme for each episode was a rapid response team call with minimal resources that the learner would have to provide care and stabilization. A literature search for rapid response team training programs found few results, but the literature assisted with providing a foundation for Nightmare on CIL Street.4,5 The goal was to completely envelop the learners in a nightmare scenario that required a solution.

After the safety brief and predata collection, learners received a phone call with minimal information about a patient in need of care. The learners responded to the requested area and provided treatment to the emergency over 25 minutes with the bedside nurse (who is an embedded participant). At the conclusion of the scenario, a physician subject matter expert who has been observing, provided a personalized 10-minute debriefing to the learner, which presented specific learning points and opportunities for the learner’s educational development. After the debriefing, learners returned to a conference room and awaited the next call. After all learners completed the 3 episodes, a group debriefing was conducted using the gather, analyze, summarize debriefing framework. The debriefing begins with an open-ended forum for learners to express their thoughts. Then, each scenario is discussed and broken down by key learning objectives. Starting with cardiac and ending with neurology, the logistics of the cases are discussed based on the trajectory of the learners during the scenarios. Each objective is discussed, and learners are allowed to ask questions before moving to the next scenario. After the debriefing, postevent data were gathered.

Objectives

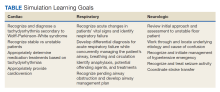

The program objective was to educate residents and students on common rapid response scenarios. We devised each scenario as an evolving simulation where various interventions would improve or worsen vital signs and symptoms. Each scenario had an end goal: cardioversion (cardiac), intubation (respiratory), and transfer (neurologic). Objectives were tailored to the trainees present during the specific simulation (Table).

IMPLEMENTATION

The initial run of the simulation curriculum was implemented on February 22, 2023, and ended on May 17, 2023, with 5 events. Participants included internal medicine PGY1 residents, third-year medical students, and fourth-year physician assistant students. Internal medicine residents ran each scenario with a subject matter expert monitoring; the undergraduate medical trainees partnered with another student. Students were pulled from their ward rotations to attend the simulation, and residents were pulled from electives and wards. Each trainee was able to experience each planned scenario. They were then briefed, participated in each scenario, and ended with a debriefing, discussing each case in detail. Two subject matter experts were always available, and occasionally 4 were present to provide additional knowledge transfer to learners. These included board-certified physicians in internal medicine and pulmonary critical care. Most scenarios were conducted on Wednesday afternoon or Thursday.

The CIL provided 6 staff minimum for every event. The staff controlled the manikins and acted as embedded players for the learners to interact and work with at the bedside. Every embedded RN was provided the same script: They were a new nurse just off orientation and did not know what to do. In addition, they were instructed that no matter who the learner wanted to call/page, that person or service was not answering or unavailable. This forced learners to respond and treat the simulated patient on their own.

Survey Responses

To evaluate the effect of this program on medical education, we administered surveys to the trainees before and after the simulation (Appendix). All questions were evaluated on a 10-point Likert scale (1, minimal comfort; 10, maximum comfort). The postsurvey added an additional Likert scale question and an open-ended question.

Sixteen trainees underwent the simulation curriculum during the 2022 to 2023 academic year, 9 internal medicine PGY1 residents, 4 medical students, and 3 physician assistant students. Postsimulation surveys indicated a mean 2.2 point increase in comfort compared with the presimulation surveys across all questions and participants.

DISCUSSION

The simulation curriculum proved to be successful for all parties, including trainees, medical educators, and simulation staff. Trainees expressed gratitude for the teaching ability of the simulation and the challenge of confronting an evolving scenario. Students also stated that the simulation allowed them to identify knowledge weaknesses.

Medical technology is rapidly advancing. A study evaluating high-fidelity medical simulations between 1969 and 2003 found that they are educationally effective and complement other medical education modalities.6 It is also noted that care provided by junior physicians with a lack of prior exposure to emergencies and unusual clinical syndromes can lead to more adverse effects.7 Simulation curriculums can be used to educate junior physicians as well as trainees on a multitude of medical emergencies, teach systematic approaches to medical scenarios, and increase exposure to unfamiliar experiences.

The goals of this article are to share program details and encourage other training programs with similar capabilities to incorporate simulation into medical education. Using pre- and postsimulation surveys, there was a concrete improvement in the value obtained by participating in this simulation. The Nightmare on CIL Street learners experienced a mean 2.2 point improvement from presimulation survey to postsimulation survey. Some notable improvements were the feelings of preparedness for rapid response situations and developing a systematic approach. As the students who participated in our Nightmare on CIL Street simulation were early in training, we believe the improvement in preparation and developing a systematic approach can be key to their success in their practical environments.

From a site-specific standpoint, improvement in confidence working through cardiac, respiratory, and neurological emergencies will be very useful. The anesthesiology service intubates during respiratory failures and there is no stroke neurologist available at the CTVHCS hospital. Giving trainees experience in these conditions may allow them to better understand their role in coordination during these times and potentially improve patient outcomes. A follow-up questionnaire administered a year after this simulation may be useful in ascertaining the usefulness of the simulation and what items may have been approached differently. We encourage other institutions to build in aspects of their site-specific challenges to improve trainee awareness in approaches to critical scenarios.

Challenges

The greatest challenge for Nightmare on CIL Street was the ability to pull internal medicine residents from their clinical duties to participate in the simulation. As there are many moving parts to their clinical scheduling, residents do not always have sufficient coverage to participate in training. There were also instances where residents needed to cover for another resident preventing them from attending the simulation. In the future, this program will schedule residents months in advance and will have the simulation training built into their rotations.

Medical and physician assistant students were pulled from their ward rotations as well. They rotate on a 2-to-4-week basis and often had already experienced the simulation the week prior, leaving out students for the following week. With more longitudinal planning, students can be pulled on a rotating monthly basis to maximize their participation. Another challenge was deciding whether residents should partner or experience the simulation on their own. After some feedback, it was noted that residents preferred to experience the simulation on their own as this improves their learning value. With the limited resources available, only rotating 3 residents on a scenario limits the number of trainees who can be reached with the program. Running this program throughout an academic year can help to reach more trainees.

CONCLUSIONS

Educating trainees on rapid response scenarios by using a simulation curriculum provides many benefits. Our trainees reported improvement in addressing cardiac, respiratory, and neurological rapid response scenarios after experiencing the simulation. They felt better prepared and had developed a better systematic approach for the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pawan Sikka, MD, George Martinez, MD and Braden Anderson, MD for participating as physician experts and educating our students. We thank Naomi Devers; Dinetra Jones; Stephanie Garrett; Sara Holton; Evelina Bartnick; Tanelle Smith; Michael Lomax; Shaun Kelemen for their participation as nurses, assistants, and simulation technology experts.

1. Guze PA. Using technology to meet the challenges of medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:260-270.

2. Higgins M, Madan C, Patel R. Development and decay of procedural skills in surgery: a systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation-based medical education interventions. Surgeon. 2021;19(4):e67-e77. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2020.07.013

3. Lyons PG, Edelson DP, Carey KA, et al. Characteristics of rapid response calls in the United States: an analysis of the first 402,023 adult cases from the Get With the Guidelines Resuscitation-Medical Emergency Team registry. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1283-1289. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003912

4. McMurray L, Hall AK, Rich J, Merchant S, Chaplin T. The nightmares course: a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, simulation-based curriculum to train and assess resident competence in resuscitation. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):503-508. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00462.1

5. Gilic F, Schultz K, Sempowski I, Blagojevic A. “Nightmares-Family Medicine” course is an effective acute care teaching tool for family medicine residents. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(3):157-162. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000355

6. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10-28. doi:10.1080/01421590500046924

7. Datta R, Upadhyay K, Jaideep C. Simulation and its role in medical education. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(2):167-172. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60040-9

The Central Texas Veteran’s Health Care System (CTVHCS) in Temple, Texas, is a 189-bed teaching hospital. CTVHCS opened the Center for Innovation and Learning (CIL) in 2022. The CIL has about 279 m2 of simulation space that includes high- and low-fidelity simulation equipment and multiple laboratories, which can be used to simulate inpatient and outpatient settings. The CIL high-fidelity manikins and environment allow learners to be immersed in the simulation for maximum realism. Computer and video systems provide clear viewing of training, which allows for more in-depth debriefing and learning. CIL simulation training is used by CTVHCS staff, medical residents, and medical and physician assistant students.

The utility of technology in medical education is rapidly evolving. As noted in many studies, simulation creates an environment that can imitate real patients in the format of a lifelike manikin, anatomic regions stations, clinical tasks, and many real-life circumstances.1 Task trainers for procedure simulation have been widely used and studied. A 2020 study noted that simulation training is effective for developing procedural skills in surgery and prevents the decay of surgical skills.2

In reviewing health care education curriculums, we noted that most of the rapid response situations are learned through active patient experiences. Rapid responses are managed by the intensive care unit and primary care teams during the day but at night are run primarily by the postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) night resident and intern. Knowing these logistics and current studies, we decided to build a rapid response simulation curriculum to improve preparedness for PGY1 residents, medical students, and physician assistant students.

Curriculum Planning

Planning the simulation curriculum began with the CTVHCS internal medicine chief resident and registered nurse (RN) educator. CTVHCS data were reviewed to identify the 3 most common rapid response calls from the past 3 years; research on the most common systems affected by rapid responses also was evaluated.

A 2019 study by Lyons and colleagues evaluated 402,023 rapid response activations across 360 hospitals and found that respiratory scenarios made up 38% and cardiac scenarios made up 37%.3 In addition, the CTVHCS has limited support in stroke neurology. Therefore, the internal medicine chief resident and RN educator decided to run 3 evolving rapid response scenarios per session that included cardiac, respiratory, and neurological scenarios. Capabilities and limitations of different high-fidelity manikins were discussed to identify and use the most appropriate simulator for each situation. Objectives that met both general medicine and site-specific education were discussed, and the program was formulated.

Program Description

Nightmare on CIL Street is a simulation-based program designed for new internal medicine residents and students to encounter difficult situations (late at night, on call, or when resources are limited; ie, weekends/holidays) in a controlled simulation environment. During the simulation, learners will be unable to transfer the patient and no additional help is available. Each learner must determine a differential diagnosis and make appropriate medical interventions with only the assistance of a nurse. Scenarios are derived from common rapid response team calls and low-volume/high-impact situations where clinical decisions must be made quickly to ensure the best patient outcomes. High-fidelity manikins that have abilities to respond to questions, simulate breathing, reproduce pathological heart and breath sounds and more are used to create a realistic patient environment.

This program aligns with 2 national Veterans Health Administration priorities: (1) connect veterans to the soonest and best care; and (2) accelerate the Veterans Health Administration journey to be a high-reliability organization (sensitivity to operations, preoccupation with failure, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise). Nightmare on CIL Street has 3 clinical episodes: 2 cardiac (A Tell-Tale Heart), respiratory (Don’t Breathe), and neurologic (Brain Scan). Additional clinical episodes will be added based on learner feedback and assessed need.

Each simulation event encompassed all 3 episodes that an individual or a team of 2 learners rotate through in a round-robin fashion. The overarching theme for each episode was a rapid response team call with minimal resources that the learner would have to provide care and stabilization. A literature search for rapid response team training programs found few results, but the literature assisted with providing a foundation for Nightmare on CIL Street.4,5 The goal was to completely envelop the learners in a nightmare scenario that required a solution.

After the safety brief and predata collection, learners received a phone call with minimal information about a patient in need of care. The learners responded to the requested area and provided treatment to the emergency over 25 minutes with the bedside nurse (who is an embedded participant). At the conclusion of the scenario, a physician subject matter expert who has been observing, provided a personalized 10-minute debriefing to the learner, which presented specific learning points and opportunities for the learner’s educational development. After the debriefing, learners returned to a conference room and awaited the next call. After all learners completed the 3 episodes, a group debriefing was conducted using the gather, analyze, summarize debriefing framework. The debriefing begins with an open-ended forum for learners to express their thoughts. Then, each scenario is discussed and broken down by key learning objectives. Starting with cardiac and ending with neurology, the logistics of the cases are discussed based on the trajectory of the learners during the scenarios. Each objective is discussed, and learners are allowed to ask questions before moving to the next scenario. After the debriefing, postevent data were gathered.

Objectives

The program objective was to educate residents and students on common rapid response scenarios. We devised each scenario as an evolving simulation where various interventions would improve or worsen vital signs and symptoms. Each scenario had an end goal: cardioversion (cardiac), intubation (respiratory), and transfer (neurologic). Objectives were tailored to the trainees present during the specific simulation (Table).

IMPLEMENTATION

The initial run of the simulation curriculum was implemented on February 22, 2023, and ended on May 17, 2023, with 5 events. Participants included internal medicine PGY1 residents, third-year medical students, and fourth-year physician assistant students. Internal medicine residents ran each scenario with a subject matter expert monitoring; the undergraduate medical trainees partnered with another student. Students were pulled from their ward rotations to attend the simulation, and residents were pulled from electives and wards. Each trainee was able to experience each planned scenario. They were then briefed, participated in each scenario, and ended with a debriefing, discussing each case in detail. Two subject matter experts were always available, and occasionally 4 were present to provide additional knowledge transfer to learners. These included board-certified physicians in internal medicine and pulmonary critical care. Most scenarios were conducted on Wednesday afternoon or Thursday.

The CIL provided 6 staff minimum for every event. The staff controlled the manikins and acted as embedded players for the learners to interact and work with at the bedside. Every embedded RN was provided the same script: They were a new nurse just off orientation and did not know what to do. In addition, they were instructed that no matter who the learner wanted to call/page, that person or service was not answering or unavailable. This forced learners to respond and treat the simulated patient on their own.

Survey Responses

To evaluate the effect of this program on medical education, we administered surveys to the trainees before and after the simulation (Appendix). All questions were evaluated on a 10-point Likert scale (1, minimal comfort; 10, maximum comfort). The postsurvey added an additional Likert scale question and an open-ended question.

Sixteen trainees underwent the simulation curriculum during the 2022 to 2023 academic year, 9 internal medicine PGY1 residents, 4 medical students, and 3 physician assistant students. Postsimulation surveys indicated a mean 2.2 point increase in comfort compared with the presimulation surveys across all questions and participants.

DISCUSSION

The simulation curriculum proved to be successful for all parties, including trainees, medical educators, and simulation staff. Trainees expressed gratitude for the teaching ability of the simulation and the challenge of confronting an evolving scenario. Students also stated that the simulation allowed them to identify knowledge weaknesses.

Medical technology is rapidly advancing. A study evaluating high-fidelity medical simulations between 1969 and 2003 found that they are educationally effective and complement other medical education modalities.6 It is also noted that care provided by junior physicians with a lack of prior exposure to emergencies and unusual clinical syndromes can lead to more adverse effects.7 Simulation curriculums can be used to educate junior physicians as well as trainees on a multitude of medical emergencies, teach systematic approaches to medical scenarios, and increase exposure to unfamiliar experiences.

The goals of this article are to share program details and encourage other training programs with similar capabilities to incorporate simulation into medical education. Using pre- and postsimulation surveys, there was a concrete improvement in the value obtained by participating in this simulation. The Nightmare on CIL Street learners experienced a mean 2.2 point improvement from presimulation survey to postsimulation survey. Some notable improvements were the feelings of preparedness for rapid response situations and developing a systematic approach. As the students who participated in our Nightmare on CIL Street simulation were early in training, we believe the improvement in preparation and developing a systematic approach can be key to their success in their practical environments.

From a site-specific standpoint, improvement in confidence working through cardiac, respiratory, and neurological emergencies will be very useful. The anesthesiology service intubates during respiratory failures and there is no stroke neurologist available at the CTVHCS hospital. Giving trainees experience in these conditions may allow them to better understand their role in coordination during these times and potentially improve patient outcomes. A follow-up questionnaire administered a year after this simulation may be useful in ascertaining the usefulness of the simulation and what items may have been approached differently. We encourage other institutions to build in aspects of their site-specific challenges to improve trainee awareness in approaches to critical scenarios.

Challenges

The greatest challenge for Nightmare on CIL Street was the ability to pull internal medicine residents from their clinical duties to participate in the simulation. As there are many moving parts to their clinical scheduling, residents do not always have sufficient coverage to participate in training. There were also instances where residents needed to cover for another resident preventing them from attending the simulation. In the future, this program will schedule residents months in advance and will have the simulation training built into their rotations.

Medical and physician assistant students were pulled from their ward rotations as well. They rotate on a 2-to-4-week basis and often had already experienced the simulation the week prior, leaving out students for the following week. With more longitudinal planning, students can be pulled on a rotating monthly basis to maximize their participation. Another challenge was deciding whether residents should partner or experience the simulation on their own. After some feedback, it was noted that residents preferred to experience the simulation on their own as this improves their learning value. With the limited resources available, only rotating 3 residents on a scenario limits the number of trainees who can be reached with the program. Running this program throughout an academic year can help to reach more trainees.

CONCLUSIONS

Educating trainees on rapid response scenarios by using a simulation curriculum provides many benefits. Our trainees reported improvement in addressing cardiac, respiratory, and neurological rapid response scenarios after experiencing the simulation. They felt better prepared and had developed a better systematic approach for the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pawan Sikka, MD, George Martinez, MD and Braden Anderson, MD for participating as physician experts and educating our students. We thank Naomi Devers; Dinetra Jones; Stephanie Garrett; Sara Holton; Evelina Bartnick; Tanelle Smith; Michael Lomax; Shaun Kelemen for their participation as nurses, assistants, and simulation technology experts.

The Central Texas Veteran’s Health Care System (CTVHCS) in Temple, Texas, is a 189-bed teaching hospital. CTVHCS opened the Center for Innovation and Learning (CIL) in 2022. The CIL has about 279 m2 of simulation space that includes high- and low-fidelity simulation equipment and multiple laboratories, which can be used to simulate inpatient and outpatient settings. The CIL high-fidelity manikins and environment allow learners to be immersed in the simulation for maximum realism. Computer and video systems provide clear viewing of training, which allows for more in-depth debriefing and learning. CIL simulation training is used by CTVHCS staff, medical residents, and medical and physician assistant students.

The utility of technology in medical education is rapidly evolving. As noted in many studies, simulation creates an environment that can imitate real patients in the format of a lifelike manikin, anatomic regions stations, clinical tasks, and many real-life circumstances.1 Task trainers for procedure simulation have been widely used and studied. A 2020 study noted that simulation training is effective for developing procedural skills in surgery and prevents the decay of surgical skills.2

In reviewing health care education curriculums, we noted that most of the rapid response situations are learned through active patient experiences. Rapid responses are managed by the intensive care unit and primary care teams during the day but at night are run primarily by the postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) night resident and intern. Knowing these logistics and current studies, we decided to build a rapid response simulation curriculum to improve preparedness for PGY1 residents, medical students, and physician assistant students.

Curriculum Planning

Planning the simulation curriculum began with the CTVHCS internal medicine chief resident and registered nurse (RN) educator. CTVHCS data were reviewed to identify the 3 most common rapid response calls from the past 3 years; research on the most common systems affected by rapid responses also was evaluated.

A 2019 study by Lyons and colleagues evaluated 402,023 rapid response activations across 360 hospitals and found that respiratory scenarios made up 38% and cardiac scenarios made up 37%.3 In addition, the CTVHCS has limited support in stroke neurology. Therefore, the internal medicine chief resident and RN educator decided to run 3 evolving rapid response scenarios per session that included cardiac, respiratory, and neurological scenarios. Capabilities and limitations of different high-fidelity manikins were discussed to identify and use the most appropriate simulator for each situation. Objectives that met both general medicine and site-specific education were discussed, and the program was formulated.

Program Description

Nightmare on CIL Street is a simulation-based program designed for new internal medicine residents and students to encounter difficult situations (late at night, on call, or when resources are limited; ie, weekends/holidays) in a controlled simulation environment. During the simulation, learners will be unable to transfer the patient and no additional help is available. Each learner must determine a differential diagnosis and make appropriate medical interventions with only the assistance of a nurse. Scenarios are derived from common rapid response team calls and low-volume/high-impact situations where clinical decisions must be made quickly to ensure the best patient outcomes. High-fidelity manikins that have abilities to respond to questions, simulate breathing, reproduce pathological heart and breath sounds and more are used to create a realistic patient environment.

This program aligns with 2 national Veterans Health Administration priorities: (1) connect veterans to the soonest and best care; and (2) accelerate the Veterans Health Administration journey to be a high-reliability organization (sensitivity to operations, preoccupation with failure, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise). Nightmare on CIL Street has 3 clinical episodes: 2 cardiac (A Tell-Tale Heart), respiratory (Don’t Breathe), and neurologic (Brain Scan). Additional clinical episodes will be added based on learner feedback and assessed need.

Each simulation event encompassed all 3 episodes that an individual or a team of 2 learners rotate through in a round-robin fashion. The overarching theme for each episode was a rapid response team call with minimal resources that the learner would have to provide care and stabilization. A literature search for rapid response team training programs found few results, but the literature assisted with providing a foundation for Nightmare on CIL Street.4,5 The goal was to completely envelop the learners in a nightmare scenario that required a solution.

After the safety brief and predata collection, learners received a phone call with minimal information about a patient in need of care. The learners responded to the requested area and provided treatment to the emergency over 25 minutes with the bedside nurse (who is an embedded participant). At the conclusion of the scenario, a physician subject matter expert who has been observing, provided a personalized 10-minute debriefing to the learner, which presented specific learning points and opportunities for the learner’s educational development. After the debriefing, learners returned to a conference room and awaited the next call. After all learners completed the 3 episodes, a group debriefing was conducted using the gather, analyze, summarize debriefing framework. The debriefing begins with an open-ended forum for learners to express their thoughts. Then, each scenario is discussed and broken down by key learning objectives. Starting with cardiac and ending with neurology, the logistics of the cases are discussed based on the trajectory of the learners during the scenarios. Each objective is discussed, and learners are allowed to ask questions before moving to the next scenario. After the debriefing, postevent data were gathered.

Objectives

The program objective was to educate residents and students on common rapid response scenarios. We devised each scenario as an evolving simulation where various interventions would improve or worsen vital signs and symptoms. Each scenario had an end goal: cardioversion (cardiac), intubation (respiratory), and transfer (neurologic). Objectives were tailored to the trainees present during the specific simulation (Table).

IMPLEMENTATION

The initial run of the simulation curriculum was implemented on February 22, 2023, and ended on May 17, 2023, with 5 events. Participants included internal medicine PGY1 residents, third-year medical students, and fourth-year physician assistant students. Internal medicine residents ran each scenario with a subject matter expert monitoring; the undergraduate medical trainees partnered with another student. Students were pulled from their ward rotations to attend the simulation, and residents were pulled from electives and wards. Each trainee was able to experience each planned scenario. They were then briefed, participated in each scenario, and ended with a debriefing, discussing each case in detail. Two subject matter experts were always available, and occasionally 4 were present to provide additional knowledge transfer to learners. These included board-certified physicians in internal medicine and pulmonary critical care. Most scenarios were conducted on Wednesday afternoon or Thursday.

The CIL provided 6 staff minimum for every event. The staff controlled the manikins and acted as embedded players for the learners to interact and work with at the bedside. Every embedded RN was provided the same script: They were a new nurse just off orientation and did not know what to do. In addition, they were instructed that no matter who the learner wanted to call/page, that person or service was not answering or unavailable. This forced learners to respond and treat the simulated patient on their own.

Survey Responses

To evaluate the effect of this program on medical education, we administered surveys to the trainees before and after the simulation (Appendix). All questions were evaluated on a 10-point Likert scale (1, minimal comfort; 10, maximum comfort). The postsurvey added an additional Likert scale question and an open-ended question.

Sixteen trainees underwent the simulation curriculum during the 2022 to 2023 academic year, 9 internal medicine PGY1 residents, 4 medical students, and 3 physician assistant students. Postsimulation surveys indicated a mean 2.2 point increase in comfort compared with the presimulation surveys across all questions and participants.

DISCUSSION

The simulation curriculum proved to be successful for all parties, including trainees, medical educators, and simulation staff. Trainees expressed gratitude for the teaching ability of the simulation and the challenge of confronting an evolving scenario. Students also stated that the simulation allowed them to identify knowledge weaknesses.

Medical technology is rapidly advancing. A study evaluating high-fidelity medical simulations between 1969 and 2003 found that they are educationally effective and complement other medical education modalities.6 It is also noted that care provided by junior physicians with a lack of prior exposure to emergencies and unusual clinical syndromes can lead to more adverse effects.7 Simulation curriculums can be used to educate junior physicians as well as trainees on a multitude of medical emergencies, teach systematic approaches to medical scenarios, and increase exposure to unfamiliar experiences.

The goals of this article are to share program details and encourage other training programs with similar capabilities to incorporate simulation into medical education. Using pre- and postsimulation surveys, there was a concrete improvement in the value obtained by participating in this simulation. The Nightmare on CIL Street learners experienced a mean 2.2 point improvement from presimulation survey to postsimulation survey. Some notable improvements were the feelings of preparedness for rapid response situations and developing a systematic approach. As the students who participated in our Nightmare on CIL Street simulation were early in training, we believe the improvement in preparation and developing a systematic approach can be key to their success in their practical environments.

From a site-specific standpoint, improvement in confidence working through cardiac, respiratory, and neurological emergencies will be very useful. The anesthesiology service intubates during respiratory failures and there is no stroke neurologist available at the CTVHCS hospital. Giving trainees experience in these conditions may allow them to better understand their role in coordination during these times and potentially improve patient outcomes. A follow-up questionnaire administered a year after this simulation may be useful in ascertaining the usefulness of the simulation and what items may have been approached differently. We encourage other institutions to build in aspects of their site-specific challenges to improve trainee awareness in approaches to critical scenarios.

Challenges

The greatest challenge for Nightmare on CIL Street was the ability to pull internal medicine residents from their clinical duties to participate in the simulation. As there are many moving parts to their clinical scheduling, residents do not always have sufficient coverage to participate in training. There were also instances where residents needed to cover for another resident preventing them from attending the simulation. In the future, this program will schedule residents months in advance and will have the simulation training built into their rotations.

Medical and physician assistant students were pulled from their ward rotations as well. They rotate on a 2-to-4-week basis and often had already experienced the simulation the week prior, leaving out students for the following week. With more longitudinal planning, students can be pulled on a rotating monthly basis to maximize their participation. Another challenge was deciding whether residents should partner or experience the simulation on their own. After some feedback, it was noted that residents preferred to experience the simulation on their own as this improves their learning value. With the limited resources available, only rotating 3 residents on a scenario limits the number of trainees who can be reached with the program. Running this program throughout an academic year can help to reach more trainees.

CONCLUSIONS

Educating trainees on rapid response scenarios by using a simulation curriculum provides many benefits. Our trainees reported improvement in addressing cardiac, respiratory, and neurological rapid response scenarios after experiencing the simulation. They felt better prepared and had developed a better systematic approach for the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pawan Sikka, MD, George Martinez, MD and Braden Anderson, MD for participating as physician experts and educating our students. We thank Naomi Devers; Dinetra Jones; Stephanie Garrett; Sara Holton; Evelina Bartnick; Tanelle Smith; Michael Lomax; Shaun Kelemen for their participation as nurses, assistants, and simulation technology experts.

1. Guze PA. Using technology to meet the challenges of medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:260-270.

2. Higgins M, Madan C, Patel R. Development and decay of procedural skills in surgery: a systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation-based medical education interventions. Surgeon. 2021;19(4):e67-e77. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2020.07.013

3. Lyons PG, Edelson DP, Carey KA, et al. Characteristics of rapid response calls in the United States: an analysis of the first 402,023 adult cases from the Get With the Guidelines Resuscitation-Medical Emergency Team registry. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1283-1289. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003912

4. McMurray L, Hall AK, Rich J, Merchant S, Chaplin T. The nightmares course: a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, simulation-based curriculum to train and assess resident competence in resuscitation. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):503-508. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00462.1

5. Gilic F, Schultz K, Sempowski I, Blagojevic A. “Nightmares-Family Medicine” course is an effective acute care teaching tool for family medicine residents. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(3):157-162. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000355

6. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10-28. doi:10.1080/01421590500046924

7. Datta R, Upadhyay K, Jaideep C. Simulation and its role in medical education. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(2):167-172. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60040-9

1. Guze PA. Using technology to meet the challenges of medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:260-270.

2. Higgins M, Madan C, Patel R. Development and decay of procedural skills in surgery: a systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation-based medical education interventions. Surgeon. 2021;19(4):e67-e77. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2020.07.013

3. Lyons PG, Edelson DP, Carey KA, et al. Characteristics of rapid response calls in the United States: an analysis of the first 402,023 adult cases from the Get With the Guidelines Resuscitation-Medical Emergency Team registry. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1283-1289. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003912

4. McMurray L, Hall AK, Rich J, Merchant S, Chaplin T. The nightmares course: a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, simulation-based curriculum to train and assess resident competence in resuscitation. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):503-508. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00462.1

5. Gilic F, Schultz K, Sempowski I, Blagojevic A. “Nightmares-Family Medicine” course is an effective acute care teaching tool for family medicine residents. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(3):157-162. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000355

6. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10-28. doi:10.1080/01421590500046924

7. Datta R, Upadhyay K, Jaideep C. Simulation and its role in medical education. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(2):167-172. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60040-9

More evidence metformin may be neuroprotective

TOPLINE:

New research suggests terminating metformin may raise the risk for dementia in older adults with type 2 diabetes, providing more evidence of metformin’s potential neuroprotective effects.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the association between discontinuing metformin for reasons unrelated to kidney dysfunction and dementia incidence.

- The cohort included 12,220 Kaiser Permanente Northern California members who stopped metformin early (with normal kidney function) and 29,126 routine metformin users.

- The cohort of early terminators was 46% women with an average age of 59 years at the start of metformin prescription. The cohort continuing metformin was 47% women, with a start age of 61 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Adults who stopped metformin early were 21% more likely to be diagnosed with dementia during follow up (hazard ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.30), compared with routine metformin users.

- This association was largely independent of changes in A1c level and insulin usage.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings “corroborate the largely consistent evidence from other observational studies showing an association between metformin use and lower dementia incidence [and] may have important implications for clinical treatment of adults with diabetes,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Scott Zimmerman, MPH, University of California, San Francisco, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Dementia diagnosis was obtained based on medical records. Factors such as race, ethnicity, or time on metformin were not evaluated. Information on the exact reason for stopping metformin was not available.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. Mr. Zimmerman owns stock in AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Abbott Laboratories. Disclosure for the other study authors can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

New research suggests terminating metformin may raise the risk for dementia in older adults with type 2 diabetes, providing more evidence of metformin’s potential neuroprotective effects.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the association between discontinuing metformin for reasons unrelated to kidney dysfunction and dementia incidence.

- The cohort included 12,220 Kaiser Permanente Northern California members who stopped metformin early (with normal kidney function) and 29,126 routine metformin users.

- The cohort of early terminators was 46% women with an average age of 59 years at the start of metformin prescription. The cohort continuing metformin was 47% women, with a start age of 61 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Adults who stopped metformin early were 21% more likely to be diagnosed with dementia during follow up (hazard ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.30), compared with routine metformin users.

- This association was largely independent of changes in A1c level and insulin usage.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings “corroborate the largely consistent evidence from other observational studies showing an association between metformin use and lower dementia incidence [and] may have important implications for clinical treatment of adults with diabetes,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Scott Zimmerman, MPH, University of California, San Francisco, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Dementia diagnosis was obtained based on medical records. Factors such as race, ethnicity, or time on metformin were not evaluated. Information on the exact reason for stopping metformin was not available.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. Mr. Zimmerman owns stock in AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Abbott Laboratories. Disclosure for the other study authors can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

New research suggests terminating metformin may raise the risk for dementia in older adults with type 2 diabetes, providing more evidence of metformin’s potential neuroprotective effects.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the association between discontinuing metformin for reasons unrelated to kidney dysfunction and dementia incidence.

- The cohort included 12,220 Kaiser Permanente Northern California members who stopped metformin early (with normal kidney function) and 29,126 routine metformin users.

- The cohort of early terminators was 46% women with an average age of 59 years at the start of metformin prescription. The cohort continuing metformin was 47% women, with a start age of 61 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Adults who stopped metformin early were 21% more likely to be diagnosed with dementia during follow up (hazard ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.30), compared with routine metformin users.

- This association was largely independent of changes in A1c level and insulin usage.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings “corroborate the largely consistent evidence from other observational studies showing an association between metformin use and lower dementia incidence [and] may have important implications for clinical treatment of adults with diabetes,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Scott Zimmerman, MPH, University of California, San Francisco, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Dementia diagnosis was obtained based on medical records. Factors such as race, ethnicity, or time on metformin were not evaluated. Information on the exact reason for stopping metformin was not available.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. Mr. Zimmerman owns stock in AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Abbott Laboratories. Disclosure for the other study authors can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Brain structural and cognitive changes during pregnancy

Pregnancy is unquestionably a major milestone in a woman’s life. During gestation, her body shape noticeably changes, but the invisible structural and cognitive changes in her brain are more striking. Some of those neurobiological changes are short-term, while others are long-lasting, well beyond delivery, and even into old age.

Physiological changes during pregnancy are extraordinary. The dramatic increases in estrogen, progesterone, and glucocorticoids help maintain pregnancy, ensure safe delivery of the baby, and trigger maternal behavior. However, other important changes also occur in the mother’s cardiac output, blood volume, renal function, respiratory output, and immune adaptations to accommodate the growth of the fetus. Gene expression also occurs to accomplish those changes, and there are lifelong repercussions from those drastic physiological changes.

During pregnancy, the brain is exposed to escalating levels of hormones released from the placenta, which the woman had never experienced. Those hormones regulate neuroplasticity, neuroinflammation, behavior, and cognition.

Structural brain changes1-6

Brain volume declines during pregnancy, reaching a nadir at the time of parturition. However, recovery occurs within 5 months after delivery. During the postpartum period, gray matter volume increases in the first 3 to 4 weeks, especially in areas involved in maternal behavior, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hypothalamus. Hippocampal gray matter decreases at 2 months postpartum compared to preconception levels, and reductions can still be observed up to 2 years following delivery. Gray matter reductions occur in multiple brain regions involved in social cognition, including the superior temporal gyrus, medial and inferior frontal cortex, fusiform areas, and hippocampus. Those changes correlate with positive maternal attachment. It is noteworthy that neural activity is highest in areas with reduced gray volume, so a decline in brain volume is associated with enhanced maternal attachment. Interestingly, those changes occur in fathers, too.

Childbearing improves stroke outcomes in middle age, but body weight will increase. The risk of Alzheimer’s disease increases with a higher number of gestations, but longevity is higher if the pregnancy occurs at an older age. Reproduction is also associated with shorter telomeres, which can elevate the risk of cancer, inflammation, diabetes, and dementia.

Cognitive changes7-10

The term “pregnancy brain” refers to cognitive changes during pregnancy and postpartum; these include decreased memory and concentration, absent-mindedness, heightened reactivity to threatening stimuli, and a decrease in motivation and executive functions. After delivery a mother has increased empathy (sometimes referred to as Theory of Mind) and greater activation in brain structures involved in empathy, including the paracingulate cortex, the posterior cingulate, and the insula. Also, the mirror neuron system becomes more activated in response to a woman’s own children compared to unfamiliar children. This incudes the ventral premotor cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the posterior parietal cortex.

Certain forms of memory are impaired during pregnancy and early postpartum, including verbal free recall and working memory, as well as executive functions. Those are believed to correlate with glucocorticoids and estrogen levels.

Continue to: The following cognitive functions...

The following cognitive functions increase between the first and second trimester: verbal memory, attention, executive functions processing speed, verbal, and visuospatial abilities. Interestingly, mothers of a male fetus outperformed mothers of a female fetus on working memory and spatial ability.

Other changes11-16

- Cells from the fetus can traffic to the mother’s body and create microchimeric cells, which have short-term benefits (healing some of the other’s organs as stem cells do) but long-term downsides include future brain disorders such as Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease, as well as autoimmune diseases and various types of cancer. The reverse also occurs with cells transferring from the mother to the fetus, persisting into infancy and childhood.

- Postpartum psychosis is associated with reductions in the volumes of the anterior cingulate, left parahippocampal gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus.

- A woman’s white matter increases during pregnancy compared to preconception. This is attributed to the high levels of prolactin, which proliferates oligodendrocytes, the glial cells that continuously manufacture myelin.

- The pituitary gland increases by 200% to 300% during pregnancy and returns to pre-pregnancy levels approximately 8 months following delivery. Prolactin also mediates the production of brain cells in the hippocampus (ie, neurogenesis).

- Sexual activity, even without pregnancy, increases neurogenesis. Plasma levels of prolactin increase significantly following an orgasm in both men and women, which indicates that sexual activity has beneficial brain effects.

- With pregnancy, the immune system shifts from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory signaling. This protects the fetus from being attacked and rejected as foreign tissue. However, at the end of pregnancy, there is a “burst” of proinflammatory signaling, which serves as a major trigger to induce uterine contractions and initiate labor (to expel the foreign tissue).

- Brain levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 increase in the postpartum period, which represents a significant modification in the neuroimmune environment, and the maternal brain assumes an inflammatory-resistant state, which has cognitive and neuroplasticity implications. However, this neuroimmune dysregulation is implicated in postpartum depression and anxiety.

- Older females who were never pregnant or only had 1 pregnancy had better overall cognitive functioning than females who became pregnant at an young age.

- In animal studies, reproduction alleviates the negative effects of aging on several hippocampal functions, especially neurogenesis. Dendritic spine density in the CA1 region of the hippocampus is higher in pregnancy and early postpartum period compared to nulliparous females (based on animal studies).

Pregnancy is indispensable for the perpetuation of the species. Its hormonal, physiologic, neurobiological, and cognitive correlates are extensive. The cognitive changes in the postpartum period are designed by evolution to prepare a woman to care for her newborn and to ensure its survival. But the biological sequelae of pregnancy extend to the rest of a woman’s life and may predispose her to immune and brain disorders as she ages.

1. Barba-Müller E, Craddock S, Carmona S, et al. Brain plasticity in pregnancy and the postpartum period: links to maternal caregiving and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2019;22(2):289-299.

2. Pawluski JL, Hoekzema E, Leuner B, et al. Less can be more: fine tuning the maternal brain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;133:104475. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.045

3. Hoekzema E, Barba-Müller E, Pozzobon C, et al. Pregnancy leads to long-lasting changes in human brain structure. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(2):287-296.

4. Cárdenas EF, Kujawa A, Humphreys KL. Neurobiological changes during the peripartum period: implications for health and behavior. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2020;15(10):1097-1110.

5. Eid RS, Chaiton JA, Lieblich SE, et al. Early and late effects of maternal experience on hippocampal neurogenesis, microglia, and the circulating cytokine milieu. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;78:1-17.

6. Galea LA, Leuner B, Slattery DA. Hippocampal plasticity during the peripartum period: influence of sex steroids, stress and ageing. J Neuroendocrinol. 2014;26(10):641-648.

7. Henry JF, Sherwin BB. Hormones and cognitive functioning during late pregnancy and postpartum: a longitudinal study. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126(1):73-85.

8. Barda G, Mizrachi Y, Borokchovich I, et al. The effect of pregnancy on maternal cognition. Sci Rep. 2011;11(1)12187. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-91504-9

9. Davies SJ, Lum JA, Skouteris H, et al. Cognitive impairment during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Med J Aust. 2018;208(1):35-40.

10. Pownall M, Hutter RRC, Rockliffe L, et al. Memory and mood changes in pregnancy: a qualitative content analysis of women’s first-hand accounts. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2023;41(5):516-527.

11. Hoekzema E, Barba-Müller E, Pozzobon C, et al. Pregnancy leads to long-lasting changes in human brain structure. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(2):287-296.

12. Duarte-Guterman P, Leuner B, Galea LAM. The long and short term effects of motherhood on the brain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019;53:100740. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.02.004

13. Haim A, Julian D, Albin-Brooks C, et al. A survey of neuroimmune changes in pregnant and postpartum female rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;59:67-78.

14. Benson JC, Malyuk DF, Madhavan A, et al. Pituitary volume changes in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Neuroradiol J. 2023. doi:10.1177/19714009231196470

15. Schepanski S, Chini M, Sternemann V, et al. Pregnancy-induced maternal microchimerism shapes neurodevelopment and behavior in mice. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4571. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-32230-2

16. Larsen CM, Grattan DR. Prolactin, neurogenesis, and maternal behaviors. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(2):201-209.

Pregnancy is unquestionably a major milestone in a woman’s life. During gestation, her body shape noticeably changes, but the invisible structural and cognitive changes in her brain are more striking. Some of those neurobiological changes are short-term, while others are long-lasting, well beyond delivery, and even into old age.

Physiological changes during pregnancy are extraordinary. The dramatic increases in estrogen, progesterone, and glucocorticoids help maintain pregnancy, ensure safe delivery of the baby, and trigger maternal behavior. However, other important changes also occur in the mother’s cardiac output, blood volume, renal function, respiratory output, and immune adaptations to accommodate the growth of the fetus. Gene expression also occurs to accomplish those changes, and there are lifelong repercussions from those drastic physiological changes.

During pregnancy, the brain is exposed to escalating levels of hormones released from the placenta, which the woman had never experienced. Those hormones regulate neuroplasticity, neuroinflammation, behavior, and cognition.

Structural brain changes1-6

Brain volume declines during pregnancy, reaching a nadir at the time of parturition. However, recovery occurs within 5 months after delivery. During the postpartum period, gray matter volume increases in the first 3 to 4 weeks, especially in areas involved in maternal behavior, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hypothalamus. Hippocampal gray matter decreases at 2 months postpartum compared to preconception levels, and reductions can still be observed up to 2 years following delivery. Gray matter reductions occur in multiple brain regions involved in social cognition, including the superior temporal gyrus, medial and inferior frontal cortex, fusiform areas, and hippocampus. Those changes correlate with positive maternal attachment. It is noteworthy that neural activity is highest in areas with reduced gray volume, so a decline in brain volume is associated with enhanced maternal attachment. Interestingly, those changes occur in fathers, too.

Childbearing improves stroke outcomes in middle age, but body weight will increase. The risk of Alzheimer’s disease increases with a higher number of gestations, but longevity is higher if the pregnancy occurs at an older age. Reproduction is also associated with shorter telomeres, which can elevate the risk of cancer, inflammation, diabetes, and dementia.

Cognitive changes7-10

The term “pregnancy brain” refers to cognitive changes during pregnancy and postpartum; these include decreased memory and concentration, absent-mindedness, heightened reactivity to threatening stimuli, and a decrease in motivation and executive functions. After delivery a mother has increased empathy (sometimes referred to as Theory of Mind) and greater activation in brain structures involved in empathy, including the paracingulate cortex, the posterior cingulate, and the insula. Also, the mirror neuron system becomes more activated in response to a woman’s own children compared to unfamiliar children. This incudes the ventral premotor cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the posterior parietal cortex.

Certain forms of memory are impaired during pregnancy and early postpartum, including verbal free recall and working memory, as well as executive functions. Those are believed to correlate with glucocorticoids and estrogen levels.

Continue to: The following cognitive functions...

The following cognitive functions increase between the first and second trimester: verbal memory, attention, executive functions processing speed, verbal, and visuospatial abilities. Interestingly, mothers of a male fetus outperformed mothers of a female fetus on working memory and spatial ability.

Other changes11-16

- Cells from the fetus can traffic to the mother’s body and create microchimeric cells, which have short-term benefits (healing some of the other’s organs as stem cells do) but long-term downsides include future brain disorders such as Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease, as well as autoimmune diseases and various types of cancer. The reverse also occurs with cells transferring from the mother to the fetus, persisting into infancy and childhood.

- Postpartum psychosis is associated with reductions in the volumes of the anterior cingulate, left parahippocampal gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus.

- A woman’s white matter increases during pregnancy compared to preconception. This is attributed to the high levels of prolactin, which proliferates oligodendrocytes, the glial cells that continuously manufacture myelin.

- The pituitary gland increases by 200% to 300% during pregnancy and returns to pre-pregnancy levels approximately 8 months following delivery. Prolactin also mediates the production of brain cells in the hippocampus (ie, neurogenesis).

- Sexual activity, even without pregnancy, increases neurogenesis. Plasma levels of prolactin increase significantly following an orgasm in both men and women, which indicates that sexual activity has beneficial brain effects.

- With pregnancy, the immune system shifts from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory signaling. This protects the fetus from being attacked and rejected as foreign tissue. However, at the end of pregnancy, there is a “burst” of proinflammatory signaling, which serves as a major trigger to induce uterine contractions and initiate labor (to expel the foreign tissue).

- Brain levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 increase in the postpartum period, which represents a significant modification in the neuroimmune environment, and the maternal brain assumes an inflammatory-resistant state, which has cognitive and neuroplasticity implications. However, this neuroimmune dysregulation is implicated in postpartum depression and anxiety.

- Older females who were never pregnant or only had 1 pregnancy had better overall cognitive functioning than females who became pregnant at an young age.

- In animal studies, reproduction alleviates the negative effects of aging on several hippocampal functions, especially neurogenesis. Dendritic spine density in the CA1 region of the hippocampus is higher in pregnancy and early postpartum period compared to nulliparous females (based on animal studies).

Pregnancy is indispensable for the perpetuation of the species. Its hormonal, physiologic, neurobiological, and cognitive correlates are extensive. The cognitive changes in the postpartum period are designed by evolution to prepare a woman to care for her newborn and to ensure its survival. But the biological sequelae of pregnancy extend to the rest of a woman’s life and may predispose her to immune and brain disorders as she ages.

Pregnancy is unquestionably a major milestone in a woman’s life. During gestation, her body shape noticeably changes, but the invisible structural and cognitive changes in her brain are more striking. Some of those neurobiological changes are short-term, while others are long-lasting, well beyond delivery, and even into old age.

Physiological changes during pregnancy are extraordinary. The dramatic increases in estrogen, progesterone, and glucocorticoids help maintain pregnancy, ensure safe delivery of the baby, and trigger maternal behavior. However, other important changes also occur in the mother’s cardiac output, blood volume, renal function, respiratory output, and immune adaptations to accommodate the growth of the fetus. Gene expression also occurs to accomplish those changes, and there are lifelong repercussions from those drastic physiological changes.

During pregnancy, the brain is exposed to escalating levels of hormones released from the placenta, which the woman had never experienced. Those hormones regulate neuroplasticity, neuroinflammation, behavior, and cognition.

Structural brain changes1-6

Brain volume declines during pregnancy, reaching a nadir at the time of parturition. However, recovery occurs within 5 months after delivery. During the postpartum period, gray matter volume increases in the first 3 to 4 weeks, especially in areas involved in maternal behavior, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hypothalamus. Hippocampal gray matter decreases at 2 months postpartum compared to preconception levels, and reductions can still be observed up to 2 years following delivery. Gray matter reductions occur in multiple brain regions involved in social cognition, including the superior temporal gyrus, medial and inferior frontal cortex, fusiform areas, and hippocampus. Those changes correlate with positive maternal attachment. It is noteworthy that neural activity is highest in areas with reduced gray volume, so a decline in brain volume is associated with enhanced maternal attachment. Interestingly, those changes occur in fathers, too.