User login

NIH launches HEAL Initiative to combat opioid crisis

The NIH HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Initiative aims to bring together agencies across the federal government, as well as academic institutions, private industry, and patient advocates to find new solutions to address the current national health emergency.

“There are 15 initiatives altogether that are being put out that we think are pretty bold and should make a big difference in our understanding of what to do about this national public health crisis,” NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, said in an interview.

HEAL will investigate ways to reformulate existing treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD), to improve efficacy and extend their availability to more patients.

“Although there are effective medications for OUD (methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone), only a small percentage of individuals in the United States who would benefit receive these medications,” according to an editorial introducing the NIH HEAL Initiative published in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8826). “Even among those who have initiated these medications, about half will relapse within 6 months.”

The editorial was authored by Dr. Collins, Walter J. Koroshetz, MD, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

For example, the current formulation of naltrexone lasts about a month within the body, Dr. Collins said in an interview. “If we had a 6-month version of that, I think it would be much more effective because oftentimes the relapses happen after a month or so, before people have fully gotten themselves on the ground.”

Better overdose antidotes are needed as well, he said, particularly for fentanyl overdose. “Narcan may not be strong enough for those long-lasting and very potent opioids like fentanyl,” he said.

HEAL also will seek a better understanding of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), also referred to as neonatal abstinence syndrome, which has become alarmingly common as more women of childbearing potential struggle with opioid addiction.

“Innovative methods to identify and treat newborns exposed to opioids, often along with other drugs, have the potential to improve both short- and long-term developmental outcomes in such children,” Dr. Collins and colleagues noted. “To determine better approaches, HEAL will expand Advancing Clinical Trials in Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (ACT NOW). This pilot study is designed to assess the prevalence of NOWS, understand current approaches to managing NOWS , and develop common approaches for larger-scale studies that will determine best practices for clinical care of infants with NOWS throughout the country.”

HEAL efforts also seek to find integrated approaches to OUD treatment.

“One particularly bold element is to put together a number of pilot projects that enable bringing together all of the ways in which we are trying to turn this epidemic around by making it possible to assess whether individuals who are addicted can be successfully treated and maintained in abstinence for long periods of time,” Dr. Collins said. “Right now, the success is not so great.

“Suppose we brought together all of the treatment programs – the primary care facilities, the emergency rooms, the fire departments, the social work experts, the health departments in the states, the local communities, the criminal justice system. We brought together all of those players in a research design where we can really see what was working. Could we do a lot more to turn this around than basically doing one of those at a time? There is this multisite idea of a national research effort, still somewhat in development, but to do integration of all of these efforts. I am pretty excited about that one.”

In looking for better ways to treat pain safely and effectively, “we need to understand how it is that people transition from acute pain to chronic pain … and what can we do increase the likelihood of recovery from acute pain without making that transition,” Dr. Collins said. “Then we need to identify additional novel targets for developing pain therapies, both devices and pharmaceuticals. We need better means of testing those ideas.”

In addition to gaining a better understanding of chronic pain, HEAL aims to investigate new nonaddictive pain treatments and find ways to expedite those treatments through the clinical pipeline, according to Dr. Collins and colleagues.

HEAL “lays the foundation for an innovative therapy-development pipeline through a planned new public-private partnership. In collaboration with biopharmaceutical groups, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Foundation for the NIH, the NIH will collect and evaluate treatment assets from academia and biopharmaceutical and device companies to coordinate and accelerate the development of effective treatments for pain and addiction,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Collins F et al, JAMA doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8826.

The NIH HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Initiative aims to bring together agencies across the federal government, as well as academic institutions, private industry, and patient advocates to find new solutions to address the current national health emergency.

“There are 15 initiatives altogether that are being put out that we think are pretty bold and should make a big difference in our understanding of what to do about this national public health crisis,” NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, said in an interview.

HEAL will investigate ways to reformulate existing treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD), to improve efficacy and extend their availability to more patients.

“Although there are effective medications for OUD (methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone), only a small percentage of individuals in the United States who would benefit receive these medications,” according to an editorial introducing the NIH HEAL Initiative published in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8826). “Even among those who have initiated these medications, about half will relapse within 6 months.”

The editorial was authored by Dr. Collins, Walter J. Koroshetz, MD, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

For example, the current formulation of naltrexone lasts about a month within the body, Dr. Collins said in an interview. “If we had a 6-month version of that, I think it would be much more effective because oftentimes the relapses happen after a month or so, before people have fully gotten themselves on the ground.”

Better overdose antidotes are needed as well, he said, particularly for fentanyl overdose. “Narcan may not be strong enough for those long-lasting and very potent opioids like fentanyl,” he said.

HEAL also will seek a better understanding of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), also referred to as neonatal abstinence syndrome, which has become alarmingly common as more women of childbearing potential struggle with opioid addiction.

“Innovative methods to identify and treat newborns exposed to opioids, often along with other drugs, have the potential to improve both short- and long-term developmental outcomes in such children,” Dr. Collins and colleagues noted. “To determine better approaches, HEAL will expand Advancing Clinical Trials in Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (ACT NOW). This pilot study is designed to assess the prevalence of NOWS, understand current approaches to managing NOWS , and develop common approaches for larger-scale studies that will determine best practices for clinical care of infants with NOWS throughout the country.”

HEAL efforts also seek to find integrated approaches to OUD treatment.

“One particularly bold element is to put together a number of pilot projects that enable bringing together all of the ways in which we are trying to turn this epidemic around by making it possible to assess whether individuals who are addicted can be successfully treated and maintained in abstinence for long periods of time,” Dr. Collins said. “Right now, the success is not so great.

“Suppose we brought together all of the treatment programs – the primary care facilities, the emergency rooms, the fire departments, the social work experts, the health departments in the states, the local communities, the criminal justice system. We brought together all of those players in a research design where we can really see what was working. Could we do a lot more to turn this around than basically doing one of those at a time? There is this multisite idea of a national research effort, still somewhat in development, but to do integration of all of these efforts. I am pretty excited about that one.”

In looking for better ways to treat pain safely and effectively, “we need to understand how it is that people transition from acute pain to chronic pain … and what can we do increase the likelihood of recovery from acute pain without making that transition,” Dr. Collins said. “Then we need to identify additional novel targets for developing pain therapies, both devices and pharmaceuticals. We need better means of testing those ideas.”

In addition to gaining a better understanding of chronic pain, HEAL aims to investigate new nonaddictive pain treatments and find ways to expedite those treatments through the clinical pipeline, according to Dr. Collins and colleagues.

HEAL “lays the foundation for an innovative therapy-development pipeline through a planned new public-private partnership. In collaboration with biopharmaceutical groups, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Foundation for the NIH, the NIH will collect and evaluate treatment assets from academia and biopharmaceutical and device companies to coordinate and accelerate the development of effective treatments for pain and addiction,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Collins F et al, JAMA doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8826.

The NIH HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Initiative aims to bring together agencies across the federal government, as well as academic institutions, private industry, and patient advocates to find new solutions to address the current national health emergency.

“There are 15 initiatives altogether that are being put out that we think are pretty bold and should make a big difference in our understanding of what to do about this national public health crisis,” NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, said in an interview.

HEAL will investigate ways to reformulate existing treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD), to improve efficacy and extend their availability to more patients.

“Although there are effective medications for OUD (methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone), only a small percentage of individuals in the United States who would benefit receive these medications,” according to an editorial introducing the NIH HEAL Initiative published in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8826). “Even among those who have initiated these medications, about half will relapse within 6 months.”

The editorial was authored by Dr. Collins, Walter J. Koroshetz, MD, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and Nora Volkow, MD, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

For example, the current formulation of naltrexone lasts about a month within the body, Dr. Collins said in an interview. “If we had a 6-month version of that, I think it would be much more effective because oftentimes the relapses happen after a month or so, before people have fully gotten themselves on the ground.”

Better overdose antidotes are needed as well, he said, particularly for fentanyl overdose. “Narcan may not be strong enough for those long-lasting and very potent opioids like fentanyl,” he said.

HEAL also will seek a better understanding of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), also referred to as neonatal abstinence syndrome, which has become alarmingly common as more women of childbearing potential struggle with opioid addiction.

“Innovative methods to identify and treat newborns exposed to opioids, often along with other drugs, have the potential to improve both short- and long-term developmental outcomes in such children,” Dr. Collins and colleagues noted. “To determine better approaches, HEAL will expand Advancing Clinical Trials in Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (ACT NOW). This pilot study is designed to assess the prevalence of NOWS, understand current approaches to managing NOWS , and develop common approaches for larger-scale studies that will determine best practices for clinical care of infants with NOWS throughout the country.”

HEAL efforts also seek to find integrated approaches to OUD treatment.

“One particularly bold element is to put together a number of pilot projects that enable bringing together all of the ways in which we are trying to turn this epidemic around by making it possible to assess whether individuals who are addicted can be successfully treated and maintained in abstinence for long periods of time,” Dr. Collins said. “Right now, the success is not so great.

“Suppose we brought together all of the treatment programs – the primary care facilities, the emergency rooms, the fire departments, the social work experts, the health departments in the states, the local communities, the criminal justice system. We brought together all of those players in a research design where we can really see what was working. Could we do a lot more to turn this around than basically doing one of those at a time? There is this multisite idea of a national research effort, still somewhat in development, but to do integration of all of these efforts. I am pretty excited about that one.”

In looking for better ways to treat pain safely and effectively, “we need to understand how it is that people transition from acute pain to chronic pain … and what can we do increase the likelihood of recovery from acute pain without making that transition,” Dr. Collins said. “Then we need to identify additional novel targets for developing pain therapies, both devices and pharmaceuticals. We need better means of testing those ideas.”

In addition to gaining a better understanding of chronic pain, HEAL aims to investigate new nonaddictive pain treatments and find ways to expedite those treatments through the clinical pipeline, according to Dr. Collins and colleagues.

HEAL “lays the foundation for an innovative therapy-development pipeline through a planned new public-private partnership. In collaboration with biopharmaceutical groups, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Foundation for the NIH, the NIH will collect and evaluate treatment assets from academia and biopharmaceutical and device companies to coordinate and accelerate the development of effective treatments for pain and addiction,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Collins F et al, JAMA doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8826.

FROM JAMA

Mifepristone, then misoprostol is best in early pregnancy loss

In a randomized trial of women with early pregnancy loss, pretreatment with mifepristone before misoprostol was superior to misoprostol alone at achieving gestational sac expulsion by the time of the first follow-up visit without additional intervention.

“Women generally prefer active management; the ability to have control over the management of miscarriage may relieve some of the emotional burden that accompanies first trimester pregnancy loss,” Courtney A. Schreiber, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her coauthors wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. But misoprostol (Cytotec) alone for women with a closed cervical os can require a second dose or intervention.

The trial enrolled 300 participants. Each had an ultrasound showing a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy of 5-12 weeks’ gestation. Women with an incomplete or inevitable abortion (that is, the absence of a gestational sac, an open cervical os, or both) were excluded, as misoprostol alone is effective for management of that diagnosis.

After randomization, 149 participants received 200 mg of oral mifepristone (Mifeprex), with 800 mcg misoprostol administered approximately 24 hours later. The other 151 participants received the standard 800 mcg dose of misoprostol alone. In both groups, the misoprostol was self-administered vaginally at home by inserting four 200-mcg tablets.

Follow-up came 24 hours to 4 days after misoprostol administration. The primary outcome was a gestational sac expulsion by the time of this follow-up, and no additional surgical or medical intervention within 30 days. If the gestational sac was present at follow-up, participants chose either expectant management, surgical management, or a second misoprostol dose.

The primary outcome was achieved in 124 of 148 women (83.8%; 95% confidence interval, 76.8-89.3) in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and in 100 of 149 women (67.1%; 95% CI, 59.0-74.6) in the misoprostol-alone group for a relative risk of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.09 to 1.43). Two women were lost to follow-up and one who was declared ineligible because of a possible ectopic pregnancy.

At 30 days’ follow-up, the cumulative rate of gestational sac expulsion with up to two doses of misoprostol was 91.2% (95% CI, 85.4-95.2) in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and 75.8% (95% CI, 68.2%-82.5%) in the misoprostol-alone group. Also by 30 days’ follow-up, 13 women in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and 35 women in the misoprostol-alone group had undergone uterine aspiration (relative risk, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68).

Serious adverse events were rare in both groups, and both groups had matching mean scores for bleeding intensity and pain.

“Pretreatment with mifepristone followed by treatment with misoprostol resulted in a significantly higher rate of complete gestational sac expulsion by approximately 2 days after treatment ... [and] a significantly lower rate of uterine aspiration than misoprostol use alone,” wrote Dr. Schreiber and her coauthors. Patient satisfaction was similar between the two groups (89.4% vs. 87.4%, respectively, described their experience overall as either “good” or “neutral”).

The trial was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Two coauthors reported grants from the National Institutes of Health during the study and another reported personal fees from Danco Laboratories, which markets mifepristone, outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-70.

The results of this study provide strong evidence that the sequential regimen of mifepristone followed by misoprostol is safe and superior to misoprostol alone in achieving treatment success and avoiding an aspiration procedure, wrote Carolyn L. Westhoff, MD, in an editorial accompanying the article.

In addition to its greater efficacy, the mifepristone treatment is quicker, which is more desirable for patients and reduces costs, inconvenience, and patient anxiety. Some women still will need prompt access to aspiration.

The mifepristone-pretreatment regimen should be the standard of care, Dr. Westhoff writes, but access to mifepristone is limited by the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy restriction, which requires that the oral drug be taken in the doctor’s office rather than obtained at a retail pharmacy. “Extensive clinical experience with mifepristone indicates that there is no need for such restrictions,” she wrote.

Carolyn L. Westhoff, MD, is a professor of epidemiology and population and family health at Columbia University in New York. Her remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2232-3). She reported personal fees from Planned Parenthood, Bayer, Agile Therapeutics, Cooper Surgical, Allergan, Elsevier, and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Merck.

The results of this study provide strong evidence that the sequential regimen of mifepristone followed by misoprostol is safe and superior to misoprostol alone in achieving treatment success and avoiding an aspiration procedure, wrote Carolyn L. Westhoff, MD, in an editorial accompanying the article.

In addition to its greater efficacy, the mifepristone treatment is quicker, which is more desirable for patients and reduces costs, inconvenience, and patient anxiety. Some women still will need prompt access to aspiration.

The mifepristone-pretreatment regimen should be the standard of care, Dr. Westhoff writes, but access to mifepristone is limited by the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy restriction, which requires that the oral drug be taken in the doctor’s office rather than obtained at a retail pharmacy. “Extensive clinical experience with mifepristone indicates that there is no need for such restrictions,” she wrote.

Carolyn L. Westhoff, MD, is a professor of epidemiology and population and family health at Columbia University in New York. Her remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2232-3). She reported personal fees from Planned Parenthood, Bayer, Agile Therapeutics, Cooper Surgical, Allergan, Elsevier, and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Merck.

The results of this study provide strong evidence that the sequential regimen of mifepristone followed by misoprostol is safe and superior to misoprostol alone in achieving treatment success and avoiding an aspiration procedure, wrote Carolyn L. Westhoff, MD, in an editorial accompanying the article.

In addition to its greater efficacy, the mifepristone treatment is quicker, which is more desirable for patients and reduces costs, inconvenience, and patient anxiety. Some women still will need prompt access to aspiration.

The mifepristone-pretreatment regimen should be the standard of care, Dr. Westhoff writes, but access to mifepristone is limited by the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy restriction, which requires that the oral drug be taken in the doctor’s office rather than obtained at a retail pharmacy. “Extensive clinical experience with mifepristone indicates that there is no need for such restrictions,” she wrote.

Carolyn L. Westhoff, MD, is a professor of epidemiology and population and family health at Columbia University in New York. Her remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2232-3). She reported personal fees from Planned Parenthood, Bayer, Agile Therapeutics, Cooper Surgical, Allergan, Elsevier, and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Merck.

In a randomized trial of women with early pregnancy loss, pretreatment with mifepristone before misoprostol was superior to misoprostol alone at achieving gestational sac expulsion by the time of the first follow-up visit without additional intervention.

“Women generally prefer active management; the ability to have control over the management of miscarriage may relieve some of the emotional burden that accompanies first trimester pregnancy loss,” Courtney A. Schreiber, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her coauthors wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. But misoprostol (Cytotec) alone for women with a closed cervical os can require a second dose or intervention.

The trial enrolled 300 participants. Each had an ultrasound showing a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy of 5-12 weeks’ gestation. Women with an incomplete or inevitable abortion (that is, the absence of a gestational sac, an open cervical os, or both) were excluded, as misoprostol alone is effective for management of that diagnosis.

After randomization, 149 participants received 200 mg of oral mifepristone (Mifeprex), with 800 mcg misoprostol administered approximately 24 hours later. The other 151 participants received the standard 800 mcg dose of misoprostol alone. In both groups, the misoprostol was self-administered vaginally at home by inserting four 200-mcg tablets.

Follow-up came 24 hours to 4 days after misoprostol administration. The primary outcome was a gestational sac expulsion by the time of this follow-up, and no additional surgical or medical intervention within 30 days. If the gestational sac was present at follow-up, participants chose either expectant management, surgical management, or a second misoprostol dose.

The primary outcome was achieved in 124 of 148 women (83.8%; 95% confidence interval, 76.8-89.3) in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and in 100 of 149 women (67.1%; 95% CI, 59.0-74.6) in the misoprostol-alone group for a relative risk of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.09 to 1.43). Two women were lost to follow-up and one who was declared ineligible because of a possible ectopic pregnancy.

At 30 days’ follow-up, the cumulative rate of gestational sac expulsion with up to two doses of misoprostol was 91.2% (95% CI, 85.4-95.2) in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and 75.8% (95% CI, 68.2%-82.5%) in the misoprostol-alone group. Also by 30 days’ follow-up, 13 women in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and 35 women in the misoprostol-alone group had undergone uterine aspiration (relative risk, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68).

Serious adverse events were rare in both groups, and both groups had matching mean scores for bleeding intensity and pain.

“Pretreatment with mifepristone followed by treatment with misoprostol resulted in a significantly higher rate of complete gestational sac expulsion by approximately 2 days after treatment ... [and] a significantly lower rate of uterine aspiration than misoprostol use alone,” wrote Dr. Schreiber and her coauthors. Patient satisfaction was similar between the two groups (89.4% vs. 87.4%, respectively, described their experience overall as either “good” or “neutral”).

The trial was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Two coauthors reported grants from the National Institutes of Health during the study and another reported personal fees from Danco Laboratories, which markets mifepristone, outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-70.

In a randomized trial of women with early pregnancy loss, pretreatment with mifepristone before misoprostol was superior to misoprostol alone at achieving gestational sac expulsion by the time of the first follow-up visit without additional intervention.

“Women generally prefer active management; the ability to have control over the management of miscarriage may relieve some of the emotional burden that accompanies first trimester pregnancy loss,” Courtney A. Schreiber, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her coauthors wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. But misoprostol (Cytotec) alone for women with a closed cervical os can require a second dose or intervention.

The trial enrolled 300 participants. Each had an ultrasound showing a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy of 5-12 weeks’ gestation. Women with an incomplete or inevitable abortion (that is, the absence of a gestational sac, an open cervical os, or both) were excluded, as misoprostol alone is effective for management of that diagnosis.

After randomization, 149 participants received 200 mg of oral mifepristone (Mifeprex), with 800 mcg misoprostol administered approximately 24 hours later. The other 151 participants received the standard 800 mcg dose of misoprostol alone. In both groups, the misoprostol was self-administered vaginally at home by inserting four 200-mcg tablets.

Follow-up came 24 hours to 4 days after misoprostol administration. The primary outcome was a gestational sac expulsion by the time of this follow-up, and no additional surgical or medical intervention within 30 days. If the gestational sac was present at follow-up, participants chose either expectant management, surgical management, or a second misoprostol dose.

The primary outcome was achieved in 124 of 148 women (83.8%; 95% confidence interval, 76.8-89.3) in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and in 100 of 149 women (67.1%; 95% CI, 59.0-74.6) in the misoprostol-alone group for a relative risk of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.09 to 1.43). Two women were lost to follow-up and one who was declared ineligible because of a possible ectopic pregnancy.

At 30 days’ follow-up, the cumulative rate of gestational sac expulsion with up to two doses of misoprostol was 91.2% (95% CI, 85.4-95.2) in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and 75.8% (95% CI, 68.2%-82.5%) in the misoprostol-alone group. Also by 30 days’ follow-up, 13 women in the mifepristone-pretreatment group and 35 women in the misoprostol-alone group had undergone uterine aspiration (relative risk, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68).

Serious adverse events were rare in both groups, and both groups had matching mean scores for bleeding intensity and pain.

“Pretreatment with mifepristone followed by treatment with misoprostol resulted in a significantly higher rate of complete gestational sac expulsion by approximately 2 days after treatment ... [and] a significantly lower rate of uterine aspiration than misoprostol use alone,” wrote Dr. Schreiber and her coauthors. Patient satisfaction was similar between the two groups (89.4% vs. 87.4%, respectively, described their experience overall as either “good” or “neutral”).

The trial was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Two coauthors reported grants from the National Institutes of Health during the study and another reported personal fees from Danco Laboratories, which markets mifepristone, outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-70.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Gestational sac expulsion was achieved in 83.8% of the mifepristone pretreatment group and in 67.1% of the misoprostol-only group.

Study details: A randomized trial of 300 women who experienced early pregnancy loss.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Two coauthors reported grants from the National Institutes of Health during the study and another reported personal fees from Danco Laboratories, outside the submitted work.

Source: Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2161-70.

Supreme Court case NIFLA v Becerra: What you need to know

On March 20, 2018, the United States Supreme Court heard arguments in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA) v Becerra. The Court is expected to issue its decision in June and the results could shape legislation around the country. Here is what you need to know.

The background

There are more than 4,000 Crisis Pregnancy Centers (CPCs) around the country, vastly out numbering abortion clinics.1 The services offered and the make-up of the staff who work in CPCs can vary. CPCs can be licensed to provide medical services, including urine pregnancy tests and ultrasounds, and may have clinicians on staff. Alternatively, other CPCs may be volunteer-run and provide counseling as well as supplies for women, including diapers and baby formula. Within CPCs, however, women are often given misleading and medically inaccurate information about abortion and contraception and are not provided with appropriate or timely referrals if they seek abortion care.

To ensure women have access to comprehensive reproductive health services, California passed the Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency (FACT) Act in 2015. This act requires licensed clinics — which may include some CPCs — to notify patients that they may access state-funded prenatal care, family planning, and abortion services through a county health department phone number. Additionally, facilities that provide pregnancy testing and ultrasounds are required to notify clients if they do not employ a licensed medical professional.

In response, NIFLA sued the state of California, alleging that the law violated their freedom of speech by forcing them to communicate about abortion with women who visited their centers.

The case

NIFLA argues that California is violating CPCs’ freedom of speech by requiring them to post statements about medications and medical procedures they strongly oppose. According to NIFLA, if California wants to promote state-funded options, they should publicize that information and not require the CPCs to post it.

The State of California enacted the law to ensure that California women have timely access to all available health care services, including contraception and abortion, and are made aware that the clinic they visit does not offer licensed medical care. Women may not know of their publicly funded options and, without this law, CPCs could withhold that information or provide misleading information, delaying or preventing women from accessing care.

Possible outcomes

If the Supreme Court strikes down California’s FACT Act as a violation of the First Amendment, CPCs in that state would not be required to provide information about free or low-cost prenatal care, contraception, and abortion services or post, if appropriate, that they were an unlicensed facility. However, such a ruling could call into question laws in 18 other states that require doctors to give women false information about possible side effects and complications of abortion during the consent process. This case could provide precedent for physicians to assert that such requirements violate their freedom of speech.

If the Supreme Court upholds California’s FACT Act, this would likely lead to similar laws around the country requiring CPCs to disclose the availability of affordable contraception and abortion services in their state and the lack of licensed medical providers.

For more information, check out https://www.supremecourt.gov/

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Sara Needleman Kline, Esq, Chief Legal Officer, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for aid with this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dias E. The Abortion Battleground: Crisis Pregnancy Centers. Time Magazine. http://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2008846,00.html. Published August 5, 2010. Accessed May 16, 2018.

On March 20, 2018, the United States Supreme Court heard arguments in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA) v Becerra. The Court is expected to issue its decision in June and the results could shape legislation around the country. Here is what you need to know.

The background

There are more than 4,000 Crisis Pregnancy Centers (CPCs) around the country, vastly out numbering abortion clinics.1 The services offered and the make-up of the staff who work in CPCs can vary. CPCs can be licensed to provide medical services, including urine pregnancy tests and ultrasounds, and may have clinicians on staff. Alternatively, other CPCs may be volunteer-run and provide counseling as well as supplies for women, including diapers and baby formula. Within CPCs, however, women are often given misleading and medically inaccurate information about abortion and contraception and are not provided with appropriate or timely referrals if they seek abortion care.

To ensure women have access to comprehensive reproductive health services, California passed the Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency (FACT) Act in 2015. This act requires licensed clinics — which may include some CPCs — to notify patients that they may access state-funded prenatal care, family planning, and abortion services through a county health department phone number. Additionally, facilities that provide pregnancy testing and ultrasounds are required to notify clients if they do not employ a licensed medical professional.

In response, NIFLA sued the state of California, alleging that the law violated their freedom of speech by forcing them to communicate about abortion with women who visited their centers.

The case

NIFLA argues that California is violating CPCs’ freedom of speech by requiring them to post statements about medications and medical procedures they strongly oppose. According to NIFLA, if California wants to promote state-funded options, they should publicize that information and not require the CPCs to post it.

The State of California enacted the law to ensure that California women have timely access to all available health care services, including contraception and abortion, and are made aware that the clinic they visit does not offer licensed medical care. Women may not know of their publicly funded options and, without this law, CPCs could withhold that information or provide misleading information, delaying or preventing women from accessing care.

Possible outcomes

If the Supreme Court strikes down California’s FACT Act as a violation of the First Amendment, CPCs in that state would not be required to provide information about free or low-cost prenatal care, contraception, and abortion services or post, if appropriate, that they were an unlicensed facility. However, such a ruling could call into question laws in 18 other states that require doctors to give women false information about possible side effects and complications of abortion during the consent process. This case could provide precedent for physicians to assert that such requirements violate their freedom of speech.

If the Supreme Court upholds California’s FACT Act, this would likely lead to similar laws around the country requiring CPCs to disclose the availability of affordable contraception and abortion services in their state and the lack of licensed medical providers.

For more information, check out https://www.supremecourt.gov/

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Sara Needleman Kline, Esq, Chief Legal Officer, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for aid with this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

On March 20, 2018, the United States Supreme Court heard arguments in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA) v Becerra. The Court is expected to issue its decision in June and the results could shape legislation around the country. Here is what you need to know.

The background

There are more than 4,000 Crisis Pregnancy Centers (CPCs) around the country, vastly out numbering abortion clinics.1 The services offered and the make-up of the staff who work in CPCs can vary. CPCs can be licensed to provide medical services, including urine pregnancy tests and ultrasounds, and may have clinicians on staff. Alternatively, other CPCs may be volunteer-run and provide counseling as well as supplies for women, including diapers and baby formula. Within CPCs, however, women are often given misleading and medically inaccurate information about abortion and contraception and are not provided with appropriate or timely referrals if they seek abortion care.

To ensure women have access to comprehensive reproductive health services, California passed the Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency (FACT) Act in 2015. This act requires licensed clinics — which may include some CPCs — to notify patients that they may access state-funded prenatal care, family planning, and abortion services through a county health department phone number. Additionally, facilities that provide pregnancy testing and ultrasounds are required to notify clients if they do not employ a licensed medical professional.

In response, NIFLA sued the state of California, alleging that the law violated their freedom of speech by forcing them to communicate about abortion with women who visited their centers.

The case

NIFLA argues that California is violating CPCs’ freedom of speech by requiring them to post statements about medications and medical procedures they strongly oppose. According to NIFLA, if California wants to promote state-funded options, they should publicize that information and not require the CPCs to post it.

The State of California enacted the law to ensure that California women have timely access to all available health care services, including contraception and abortion, and are made aware that the clinic they visit does not offer licensed medical care. Women may not know of their publicly funded options and, without this law, CPCs could withhold that information or provide misleading information, delaying or preventing women from accessing care.

Possible outcomes

If the Supreme Court strikes down California’s FACT Act as a violation of the First Amendment, CPCs in that state would not be required to provide information about free or low-cost prenatal care, contraception, and abortion services or post, if appropriate, that they were an unlicensed facility. However, such a ruling could call into question laws in 18 other states that require doctors to give women false information about possible side effects and complications of abortion during the consent process. This case could provide precedent for physicians to assert that such requirements violate their freedom of speech.

If the Supreme Court upholds California’s FACT Act, this would likely lead to similar laws around the country requiring CPCs to disclose the availability of affordable contraception and abortion services in their state and the lack of licensed medical providers.

For more information, check out https://www.supremecourt.gov/

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Sara Needleman Kline, Esq, Chief Legal Officer, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for aid with this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dias E. The Abortion Battleground: Crisis Pregnancy Centers. Time Magazine. http://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2008846,00.html. Published August 5, 2010. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Dias E. The Abortion Battleground: Crisis Pregnancy Centers. Time Magazine. http://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2008846,00.html. Published August 5, 2010. Accessed May 16, 2018.

What do the genes GDF15 and IGFBP7 mean for the future of hyperemesis gravidarum treatment?

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

Genes GDF15 and IGFBP7 have been associated with hyperemesis gravidarum

The association may allow for future techniques in the prediction, prevention, and treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum

Pregnancy may be ideal time to consider switching MS drugs

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NASHVILLE, TENN – Women with multiple sclerosis who fare poorly on specific medications before pregnancy don’t tend to do any better afterward, a new study finds. This suggests that pregnancy – a period when many women with MS stop taking their medication – should trigger discussions about switching from drugs that aren’t doing the job, the study’s lead author said.

“It’s a good time to consider the therapy that the individual is on, whether it’s one that’s effective for them, and whether it’s one they should return to when they start up therapy post-partum. It’s likely it will affect them the same way” after pregnancy as before, Caila Vaughn, MPH, PhD, of the University of Buffalo, said in an interview at the 2018 annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Clinics.

From 2012-2017, the study authors sent surveys to 1,651 women in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium as part of an effort to understand how pregnancy affects women with MS, especially when relapses return in the post-partum period.

Of the 1,651 women, 635 (38% of the total) agreed to answer questions about their reproductive history.

Pregnancy data was available for 627 patients of whom 490 (78%) had been pregnant. Of those, 109 said they became pregnant after their MS diagnosis.

Fifty-three (49%) reported relapses in the 2 years prior to pregnancy and 46% reported them in the 2 subsequent years. Just 12% reported relapses during pregnancy, and 16% said they took disease-modifying drugs during pregnancy (60% had taken them before pregnancy).

Why does MS become less severe during pregnancy? “We believe the dormancy of the disease is related to an immune system that is naturally decreased and depressed during pregnancy,” Dr. Vaughn said. Afterward, she said, “the relapses are related to the recovery of the immune system post-partum.”

The researchers didn’t find any links between the use of disease-modifying drugs and relapses before, during, or after pregnancy.

Those who had relapses prior to pregnancy were more likely (P = 0.011) to have them afterward too. But researchers didn’t find a statistically significant link between relapses that occurred during and after pregnancy.

More than three-quarters of those who took disease-modifying drugs before pregnancy returned to using them afterward, in most cases within 3 months.

The study findings suggest that pregnancy is a helpful decision point when patients should take a closer look at the effects of their medications, Dr. Vaughn said. “In conjunction with a physician, they should decide if it’s a good one they should return to.”

Reflecting the findings of other research that suggests pregnancy is safe in women with MS, the study shows no sign that pregnancy – either before or after diagnosis of MS – boosts the risk that MS will get worse.

As for the possible effects of disease-modifying drugs on new mothers who breast-feed, the researchers found no evidence of adverse outcomes in 5 patients who took the medications while breast-feeding.

The study was funded by Teva. Dr. Vaughn reported no relevant disclosures. Several other study authors report various disclosures, including relationships with Teva.

SOURCE: Vaughn C. et al. Abstract FC04, 2018 annual meeting, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NASHVILLE, TENN – Women with multiple sclerosis who fare poorly on specific medications before pregnancy don’t tend to do any better afterward, a new study finds. This suggests that pregnancy – a period when many women with MS stop taking their medication – should trigger discussions about switching from drugs that aren’t doing the job, the study’s lead author said.

“It’s a good time to consider the therapy that the individual is on, whether it’s one that’s effective for them, and whether it’s one they should return to when they start up therapy post-partum. It’s likely it will affect them the same way” after pregnancy as before, Caila Vaughn, MPH, PhD, of the University of Buffalo, said in an interview at the 2018 annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Clinics.

From 2012-2017, the study authors sent surveys to 1,651 women in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium as part of an effort to understand how pregnancy affects women with MS, especially when relapses return in the post-partum period.

Of the 1,651 women, 635 (38% of the total) agreed to answer questions about their reproductive history.

Pregnancy data was available for 627 patients of whom 490 (78%) had been pregnant. Of those, 109 said they became pregnant after their MS diagnosis.

Fifty-three (49%) reported relapses in the 2 years prior to pregnancy and 46% reported them in the 2 subsequent years. Just 12% reported relapses during pregnancy, and 16% said they took disease-modifying drugs during pregnancy (60% had taken them before pregnancy).

Why does MS become less severe during pregnancy? “We believe the dormancy of the disease is related to an immune system that is naturally decreased and depressed during pregnancy,” Dr. Vaughn said. Afterward, she said, “the relapses are related to the recovery of the immune system post-partum.”

The researchers didn’t find any links between the use of disease-modifying drugs and relapses before, during, or after pregnancy.

Those who had relapses prior to pregnancy were more likely (P = 0.011) to have them afterward too. But researchers didn’t find a statistically significant link between relapses that occurred during and after pregnancy.

More than three-quarters of those who took disease-modifying drugs before pregnancy returned to using them afterward, in most cases within 3 months.

The study findings suggest that pregnancy is a helpful decision point when patients should take a closer look at the effects of their medications, Dr. Vaughn said. “In conjunction with a physician, they should decide if it’s a good one they should return to.”

Reflecting the findings of other research that suggests pregnancy is safe in women with MS, the study shows no sign that pregnancy – either before or after diagnosis of MS – boosts the risk that MS will get worse.

As for the possible effects of disease-modifying drugs on new mothers who breast-feed, the researchers found no evidence of adverse outcomes in 5 patients who took the medications while breast-feeding.

The study was funded by Teva. Dr. Vaughn reported no relevant disclosures. Several other study authors report various disclosures, including relationships with Teva.

SOURCE: Vaughn C. et al. Abstract FC04, 2018 annual meeting, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NASHVILLE, TENN – Women with multiple sclerosis who fare poorly on specific medications before pregnancy don’t tend to do any better afterward, a new study finds. This suggests that pregnancy – a period when many women with MS stop taking their medication – should trigger discussions about switching from drugs that aren’t doing the job, the study’s lead author said.

“It’s a good time to consider the therapy that the individual is on, whether it’s one that’s effective for them, and whether it’s one they should return to when they start up therapy post-partum. It’s likely it will affect them the same way” after pregnancy as before, Caila Vaughn, MPH, PhD, of the University of Buffalo, said in an interview at the 2018 annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Clinics.

From 2012-2017, the study authors sent surveys to 1,651 women in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium as part of an effort to understand how pregnancy affects women with MS, especially when relapses return in the post-partum period.

Of the 1,651 women, 635 (38% of the total) agreed to answer questions about their reproductive history.

Pregnancy data was available for 627 patients of whom 490 (78%) had been pregnant. Of those, 109 said they became pregnant after their MS diagnosis.

Fifty-three (49%) reported relapses in the 2 years prior to pregnancy and 46% reported them in the 2 subsequent years. Just 12% reported relapses during pregnancy, and 16% said they took disease-modifying drugs during pregnancy (60% had taken them before pregnancy).

Why does MS become less severe during pregnancy? “We believe the dormancy of the disease is related to an immune system that is naturally decreased and depressed during pregnancy,” Dr. Vaughn said. Afterward, she said, “the relapses are related to the recovery of the immune system post-partum.”

The researchers didn’t find any links between the use of disease-modifying drugs and relapses before, during, or after pregnancy.

Those who had relapses prior to pregnancy were more likely (P = 0.011) to have them afterward too. But researchers didn’t find a statistically significant link between relapses that occurred during and after pregnancy.

More than three-quarters of those who took disease-modifying drugs before pregnancy returned to using them afterward, in most cases within 3 months.

The study findings suggest that pregnancy is a helpful decision point when patients should take a closer look at the effects of their medications, Dr. Vaughn said. “In conjunction with a physician, they should decide if it’s a good one they should return to.”

Reflecting the findings of other research that suggests pregnancy is safe in women with MS, the study shows no sign that pregnancy – either before or after diagnosis of MS – boosts the risk that MS will get worse.

As for the possible effects of disease-modifying drugs on new mothers who breast-feed, the researchers found no evidence of adverse outcomes in 5 patients who took the medications while breast-feeding.

The study was funded by Teva. Dr. Vaughn reported no relevant disclosures. Several other study authors report various disclosures, including relationships with Teva.

SOURCE: Vaughn C. et al. Abstract FC04, 2018 annual meeting, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

REPORTING FROM THE CMSC ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Multiple sclerosis relapse rates are similar before and after pregnancy, suggesting it may be a good time to consider switching medications if feasible.

Major finding: 49% of women who were pregnant after MS diagnosis reported relapses in the 2 years prior to pregnancy and 46% reported them in the 2 subsequent years. Those who had relapses prior to pregnancy were more likely to have them afterward, too.

Study details: Survey of 109 women who became pregnant after MS diagnosis.

Disclosures: Teva funded the study. Several study authors report various disclosures, including relationships with Teva.

Source: Vaughn C. et al. Abstract FC04, 2018 annual meeting, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Neonatal deaths lower in high-volume hospitals

AUSTIN, TEX. – A first look at the timing of neonatal deaths showed an association with weekend deliveries in one Texas county. However, birth weight and ethnicity attenuated the association, according to a recent study. Higher hospital volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal deaths.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study, presented during the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, used data from birth certificates and infant death certificates in the state of Texas. The investigators, said Elizabeth Restrepo, PhD, chose to examine data from Tarrant County, Tex., which has historically had persistently high infant mortality rates; in 2013, she said, the infant mortality rate in that county was 7.11/1,000 births – the highest in the state for that year.

The first question Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues at Texas Women’s University, Denton, wanted to answer was whether there was an association between the risk of neonatal mortality and the day of the week of the birth. For this and the study’s other research questions, she and her colleagues looked at 2012 data, matching 32,140 birth certificate records with 92 infant death certificates.

The investigators found an independent association between the risk of neonatal death and whether the birth happened on a weekday (Monday at 7:00 a.m. through Friday at 6:59 p.m.), or on a weekend (Friday at 7:00 p.m. through Monday at 6:59 a.m.). However, once birth weight and ethnicity were controlled in the statistical analysis, the association was not statistically significant despite an odds ratio of 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.911-2.27; P = .119).

“Births in the 12 hospitals studied appear to have been organized to take place more frequently on the working weekday rather than weekend days,” wrote Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation. Although the study wasn’t designed to answer this particular question, Dr. Restrepo said in discussion during the poster session that planned deliveries, such as inductions and cesarean deliveries, are likely to happen during the week, while the case mix is wider on weekends. Patient characteristics, as well as staffing patterns, may come into play.

The researchers also asked whether birth volume at a given institution increases the odds of neonatal death on weekends. Here, they found a significant inverse relationship between hospital birth volume and neonatal deaths (r = –0.021; P less than .001). With each additional increase of 1% in the weekday birth rate, the odds of neonatal death dropped by approximately 7.4%.

Examining the Tarrant County data further, Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues found that the hospitals with higher birth volumes had a more even distribution of births across the days of the week, with resulting lower concentrations of births during the week (r = –.394; P less than .001).

To classify infant deaths, the investigators included only ICD-10 diagnoses classified as P-codes to capture deaths occurring in the first 28 days after birth, but excluding congenital problems that are incompatible with life or that usually cause early death.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study was funded by a research enhancement program award from the Texas Women’s University Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

SOURCE: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A first look at the timing of neonatal deaths showed an association with weekend deliveries in one Texas county. However, birth weight and ethnicity attenuated the association, according to a recent study. Higher hospital volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal deaths.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study, presented during the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, used data from birth certificates and infant death certificates in the state of Texas. The investigators, said Elizabeth Restrepo, PhD, chose to examine data from Tarrant County, Tex., which has historically had persistently high infant mortality rates; in 2013, she said, the infant mortality rate in that county was 7.11/1,000 births – the highest in the state for that year.

The first question Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues at Texas Women’s University, Denton, wanted to answer was whether there was an association between the risk of neonatal mortality and the day of the week of the birth. For this and the study’s other research questions, she and her colleagues looked at 2012 data, matching 32,140 birth certificate records with 92 infant death certificates.

The investigators found an independent association between the risk of neonatal death and whether the birth happened on a weekday (Monday at 7:00 a.m. through Friday at 6:59 p.m.), or on a weekend (Friday at 7:00 p.m. through Monday at 6:59 a.m.). However, once birth weight and ethnicity were controlled in the statistical analysis, the association was not statistically significant despite an odds ratio of 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.911-2.27; P = .119).

“Births in the 12 hospitals studied appear to have been organized to take place more frequently on the working weekday rather than weekend days,” wrote Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation. Although the study wasn’t designed to answer this particular question, Dr. Restrepo said in discussion during the poster session that planned deliveries, such as inductions and cesarean deliveries, are likely to happen during the week, while the case mix is wider on weekends. Patient characteristics, as well as staffing patterns, may come into play.

The researchers also asked whether birth volume at a given institution increases the odds of neonatal death on weekends. Here, they found a significant inverse relationship between hospital birth volume and neonatal deaths (r = –0.021; P less than .001). With each additional increase of 1% in the weekday birth rate, the odds of neonatal death dropped by approximately 7.4%.

Examining the Tarrant County data further, Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues found that the hospitals with higher birth volumes had a more even distribution of births across the days of the week, with resulting lower concentrations of births during the week (r = –.394; P less than .001).

To classify infant deaths, the investigators included only ICD-10 diagnoses classified as P-codes to capture deaths occurring in the first 28 days after birth, but excluding congenital problems that are incompatible with life or that usually cause early death.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study was funded by a research enhancement program award from the Texas Women’s University Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

SOURCE: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A first look at the timing of neonatal deaths showed an association with weekend deliveries in one Texas county. However, birth weight and ethnicity attenuated the association, according to a recent study. Higher hospital volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal deaths.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study, presented during the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, used data from birth certificates and infant death certificates in the state of Texas. The investigators, said Elizabeth Restrepo, PhD, chose to examine data from Tarrant County, Tex., which has historically had persistently high infant mortality rates; in 2013, she said, the infant mortality rate in that county was 7.11/1,000 births – the highest in the state for that year.

The first question Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues at Texas Women’s University, Denton, wanted to answer was whether there was an association between the risk of neonatal mortality and the day of the week of the birth. For this and the study’s other research questions, she and her colleagues looked at 2012 data, matching 32,140 birth certificate records with 92 infant death certificates.

The investigators found an independent association between the risk of neonatal death and whether the birth happened on a weekday (Monday at 7:00 a.m. through Friday at 6:59 p.m.), or on a weekend (Friday at 7:00 p.m. through Monday at 6:59 a.m.). However, once birth weight and ethnicity were controlled in the statistical analysis, the association was not statistically significant despite an odds ratio of 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.911-2.27; P = .119).

“Births in the 12 hospitals studied appear to have been organized to take place more frequently on the working weekday rather than weekend days,” wrote Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation. Although the study wasn’t designed to answer this particular question, Dr. Restrepo said in discussion during the poster session that planned deliveries, such as inductions and cesarean deliveries, are likely to happen during the week, while the case mix is wider on weekends. Patient characteristics, as well as staffing patterns, may come into play.

The researchers also asked whether birth volume at a given institution increases the odds of neonatal death on weekends. Here, they found a significant inverse relationship between hospital birth volume and neonatal deaths (r = –0.021; P less than .001). With each additional increase of 1% in the weekday birth rate, the odds of neonatal death dropped by approximately 7.4%.

Examining the Tarrant County data further, Dr. Restrepo and her colleagues found that the hospitals with higher birth volumes had a more even distribution of births across the days of the week, with resulting lower concentrations of births during the week (r = –.394; P less than .001).

To classify infant deaths, the investigators included only ICD-10 diagnoses classified as P-codes to capture deaths occurring in the first 28 days after birth, but excluding congenital problems that are incompatible with life or that usually cause early death.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest; the study was funded by a research enhancement program award from the Texas Women’s University Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

SOURCE: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Key clinical point: Neonatal deaths were lower in hospitals with higher delivery volumes.

Major finding: Higher weekday birth volumes were associated with lower risk of neonatal death (P = .002).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 92 neonatal deaths in a single Texas county in 2012.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Texas Women’s University. The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

Source: Restrepo E et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 22R.

Lessons from a daunting malpractice event

CASE Failure to perform cesarean delivery1–4

A 19-year-old woman (G1P0) received prenatal care at a federally funded health center. Her pregnancy was normal without complications. She presented to the hospital after spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM). The on-call ObGyn employed by the clinic was offsite when the mother was admitted.

The mother signed a standard consent form for vaginal and cesarean deliveries and any other surgical procedure required during the course of giving birth.

The ObGyn ordered low-dose oxytocin to augment labor in light of her SROM. Oxytocin was started at 9:46

Upon delivery, the infant was flaccid and not breathing. His Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 6 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively, and the cord pH was 7. The neonatal intensive care (NICU) team provided aggressive resuscitation.

At the time of trial, the 18-month-old boy was being fed through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube and had a tracheostomy that required periodic suctioning. The child was not able to stand, crawl, or support himself, and will require 24-hour nursing care for the rest of his life.

LAWSUIT. The parents filed a lawsuit in federal court for damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act (see “Notes about this case,”). The mother claimed that she had requested a cesarean delivery early in labor when FHR tracings showed fetal distress, and again prior to vacuum extraction; the ObGyn refused both times.

The ObGyn claimed that when he noted a category III tracing, he recommended cesarean delivery, but the patient refused. He recorded the refusal in the chart some time later, after he had noted the neonate’s appearance.

The parents’ expert testified that restarting oxytocin and using vacuum extraction multiple times were dangerous and gross deviations from acceptable practice. Prolonged and repetitive use of the vacuum extractor caused a large subgaleal hematoma that decreased blood flow to the fetal brain, resulting in irreversible central nervous system (CNS) damage secondary to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed at the first sign of fetal distress.

The defense expert pointed out that the ObGyn discussed the need for cesarean delivery with the patient when fetal distress occurred and that the ObGyn was bedside and monitoring the fetus and the mother. Although the mother consented to a cesarean delivery at time of admission, she refused to allow the procedure.

The labor and delivery (L&D) nurse corroborated the mother’s story that a cesarean delivery was not offered by the ObGyn, and when the patient asked for a cesarean delivery, he refused. The nurse stated that the note added to the records by the ObGyn about the mother’s refusal was a lie. If the mother had refused a cesarean, the nurse would have documented the refusal by completing a Refusal of Treatment form that would have been faxed to the risk manager. No such form was required because nothing was ever offered that the mother refused.

The nurse also testified that during the course of the latter part of labor, the ObGyn left the room several times to assist other patients, deliver another baby, and make an 8-minute phone call to his stockbroker. She reported that the ObGyn was out of the room when delivery occurred.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

Read about the verdict and medical considerations.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The medical care and the federal-court bench trial held in front of a judge (not a jury) occurred in Florida. The verdict suggests that the ObGyn breached the standard of care by not offering or proceeding with a cesarean delivery and this management resulted in the child’s injuries. The court awarded damages in the amount of $33,813,495.91, including $29,413,495.91 for the infant; $3,300,000.00 for the plaintiff; and $1,100,000.00 for her spouse.4

Medical considerations

Refusal of medical care

Although it appears that in this case the patient did not actually refuse medical care (cesarean delivery), the case does raise the question of refusal. Refusal of medical care has been addressed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) predicated upon care that supports maternal and fetal wellbeing.5 There may be a fine balance between safeguarding the pregnant woman’s autonomy and optimization of fetal wellbeing. “Forced compliance,” on the other hand, is the alternative to respecting refusal of treatment. Ethical issues come into play: patient rights; respect for autonomy; violations of bodily integrity; power differentials; and gender equality.5 The use of coercion is “not only ethically impermissible but also medically inadvisable secondary to the realities of prognostic uncertainty and the limitations of medical knowledge.”5 There is an obligation to elicit the patient’s reasoning and lived experience. Perhaps most importantly, as clinicians working to achieve a resolution, consideration of the following is appropriate5:

- reliability and validity of evidence-based medicine

- severity of the prospective outcome

- degree of risk or burden placed on the patient

- patient understanding of the gravity of the situation and risks

- degree of urgency.

Much of this boils down to the obligation to discuss “risks and benefits of treatment, alternatives and consequences of refusing treatment.”6

Complications from vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery

Ghidini and associates, in a multicenter retrospective study, evaluated complications relating to vacuum-assisted delivery. They listed major primary outcomes of subgaleal hemorrhage, skull fracture, and intracranial bleeding, and minor primary outcomes of cephalohematoma, scalp laceration, and extensive skin abrasions. Secondary outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of <7, umbilical artery pH of <7.10, shoulder dystocia, and NICU admission.7

A retrospective study from Sweden assessing all vacuum deliveries over a 2-year period compared the use of the Kiwi OmniCup (Clinical Innovations) to use of the Malmström metal cup (Medela). No statistical differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes as well as failure rates were noted. However, the duration of the procedure was longer and the requirement for fundal pressure was higher with the Malmström device.8

Subgaleal hemorrhage. Ghidini and colleagues reported a heightened incidence of head injury related to the duration of vacuum application and birth weight.7 Specifically, vacuum delivery devices increase the risk of subgaleal hemorrhage. Blood can accumulate between the scalp’s epicranial aponeurosis and the periosteum and potentially can extend forward to the orbital margins, backward to the nuchal ridge, and laterally to the temporal fascia. As much as 260 mL of blood can get into this subaponeurotic space in term babies.9 Up to one-quarter of babies who require NICU admission for this condition die.10 This injury seldom occurs with forceps.

Shoulder dystocia. In a meta-analysisfrom Italy, the vacuum extractor was associated with increased risk of shoulder dystocia compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery.11

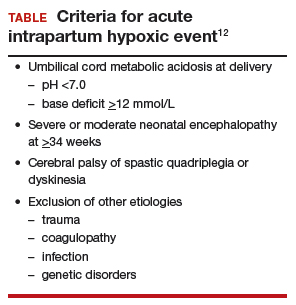

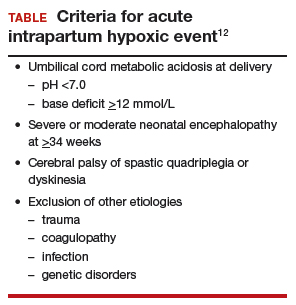

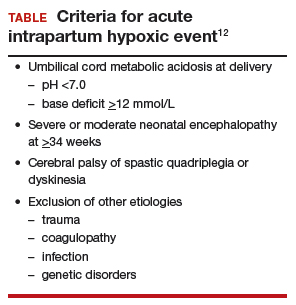

Intrapartum hypoxia. In 2003, the ACOG Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy defined an acute intrapartum hypoxic event (TABLE).12

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as “a chronic neuromuscular disability characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture appearing early in life and not the result of recognized progressive disease.”13,14

The Collaborative Perinatal Project concluded that birth trauma plays a minimal role in development of CP.15 Arrested labor, use of oxytocin, or prolonged labor did not play a role. CP can develop following significant cerebral or posterior fossa hemorrhage in term infants.16

Perinatal asphyxia is a poor and imprecise term and use of the expression should be abandoned. Overall, 90% of children with CP do not have birth asphyxia as the underlying etiology.14

Prognostic assessment can be made, in part, by using the Sarnat classification system (classification scale for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of the newborn) or an electroencephalogram to stratify the severity of neonatal encephalopathy.12 Such tests are not stand-alone but a segment of assessment. At this point “a better understanding of the processes leading to neonatal encephalopathy and associated outcomes” appear to be required to understand and associate outcomes.12 “More accurate and reliable tools (are required) for prognostic forecasting.”12

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy involves multisystem organ failure including renal, hepatic, hematologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and metabolic abnormalities. There is no correlation between the degree of CNS injury and level of other organ abnormalities.12

Differential diagnosis

When events such as those described in this case occur, develop a differential diagnosis by considering the following12:

- uterine rupture

- severe placental abruption

- umbilical cord prolapse

- amniotic fluid embolus

- maternal cardiovascular collapse

- fetal exsanguination.

Read about the legal considerations.

Legal considerations

Although ObGyns are among the specialties most likely to experience malpractice claims,17 a verdict of more than $33 million is unusual.18 Despite the failure of adequate care, and the enormous damages, the ObGyn involved probably will not be responsible for paying the verdict (see “Notes about this case”). The case presents a number of important lessons and reminders for anyone practicing obstetrics.

A procedural comment

The case in this article arose under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA).1 Most government entities have sovereign immunity, meaning that they can be sued only with their consent. In the FTCA, the federal government consented to being sued for the acts of its employees. This right has a number of limitations and some technical procedures, but at its core, it permits the United States to be sued as though it was a private individual.2 Private individuals can be sued for the acts of the agents (including employees).

Although the FTCA is a federal law, and these cases are tried in federal court, the substantive law of the state applies. This case occurred in Florida, so Florida tort law, defenses, and limitation on claims applied here also. Had the events occurred in Iowa, Iowa law would have applied.

In FTCA cases, the United States is the defendant (generally it is the government, not the employee who is the defendant).3 In this case, the ObGyn was employed by a federal government entity to provide delivery services. As a result, the United States was the primary defendant, had the obligation to defend the suit, and will almost certainly be obligated to pay the verdict.

The case facts

Although this description is based on an actual case, the facts were taken from the opinion of the trial court, legal summaries and press reports and not from the full case documents.4-7 We could not independently assess the accuracy of the facts, but for the purpose of this discussion, we have assumed the facts to be correct. The government has apparently filed an appeal in the Eleventh Circuit.

References

- Federal Tort Claims Act. Vol 28 U.S.C. Pt.VI Ch.171 and 28 U.S.C. § 1346(b).

- About the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). Health Resources & Services Administration: Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/ftca/about/index.html. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Dowell MA, Scott CD. Federally Qualified Health Center Federal Tort Claims Act Insurance Coverage. Health Law. 2015;5:31-43.

- Chang D. Miami doctor's call to broker during baby's delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17-18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

Very large verdict

The extraordinary size of this verdict ($33 million without any punitive damages) is a reminder that in obstetrics, mistakes can have catastrophic consequences and very high costs.19 This fact is reflected in malpractice insurance rates.

A substantial amount of this case’s award will provide around-the-clock care for the child. This verdict was not the result of a runaway jury—it was a judge’s decision. It is also noteworthy to report that a small percentage of physicians (1%) appear responsible for a significant number (about one-third) of paid claims.20