User login

Perinatal problems raise adult OCD risk

Adverse events during the perinatal period were independently associated with an increased risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder at age 40 years, based on data published Oct. 5 from a population-based cohort study of more than 2 million Swedish children.

Perinatal complications, including C-section delivery and preterm birth, have been linked to psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, autism, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but evidence of an impact of obsessive-compulsive disorders has not been well studied, reported Gustaf Brander of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, and his colleagues.

The researchers reviewed data from 2,421,284 live singleton births in Sweden between Jan. 1, 1973, and Dec. 31, 1996. The overall prevalence of OCD was 1.3% at 40 years of age. Several perinatal factors were independently associated with an increased OCD risk: breech presentation, cesarean section delivery, gestational age of less than 32 weeks, maternal smoking during pregnancy, Apgar scores near the distress level, and both low and high birth weight (defined as 1,500-2,500 g and greater than 4,500 g, respectively).

“These findings contradict the widely held notion that, although mental disorders share genetic risk factors, the contribution of environmental risk factors is largely disorder specific,” with the exception of maternal smoking during pregnancy, the researchers wrote. In addition, the researchers found a dose-response relationship in which the risk for OCD increased with the greater number of perinatal adverse events.

“The findings are important for the understanding of the cause of OCD and will inform future studies of gene by environment interaction and epigenetics,” the researchers said. “If the finding is replication, the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and OCD may emerge as an interesting disorder-specific risk factor for evaluation in future research,” they added.

Mr. Brander had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Eli Lilly, Shire, and Medice.

Find the full study here: (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2095).

Adverse events during the perinatal period were independently associated with an increased risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder at age 40 years, based on data published Oct. 5 from a population-based cohort study of more than 2 million Swedish children.

Perinatal complications, including C-section delivery and preterm birth, have been linked to psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, autism, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but evidence of an impact of obsessive-compulsive disorders has not been well studied, reported Gustaf Brander of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, and his colleagues.

The researchers reviewed data from 2,421,284 live singleton births in Sweden between Jan. 1, 1973, and Dec. 31, 1996. The overall prevalence of OCD was 1.3% at 40 years of age. Several perinatal factors were independently associated with an increased OCD risk: breech presentation, cesarean section delivery, gestational age of less than 32 weeks, maternal smoking during pregnancy, Apgar scores near the distress level, and both low and high birth weight (defined as 1,500-2,500 g and greater than 4,500 g, respectively).

“These findings contradict the widely held notion that, although mental disorders share genetic risk factors, the contribution of environmental risk factors is largely disorder specific,” with the exception of maternal smoking during pregnancy, the researchers wrote. In addition, the researchers found a dose-response relationship in which the risk for OCD increased with the greater number of perinatal adverse events.

“The findings are important for the understanding of the cause of OCD and will inform future studies of gene by environment interaction and epigenetics,” the researchers said. “If the finding is replication, the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and OCD may emerge as an interesting disorder-specific risk factor for evaluation in future research,” they added.

Mr. Brander had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Eli Lilly, Shire, and Medice.

Find the full study here: (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2095).

Adverse events during the perinatal period were independently associated with an increased risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder at age 40 years, based on data published Oct. 5 from a population-based cohort study of more than 2 million Swedish children.

Perinatal complications, including C-section delivery and preterm birth, have been linked to psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, autism, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but evidence of an impact of obsessive-compulsive disorders has not been well studied, reported Gustaf Brander of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, and his colleagues.

The researchers reviewed data from 2,421,284 live singleton births in Sweden between Jan. 1, 1973, and Dec. 31, 1996. The overall prevalence of OCD was 1.3% at 40 years of age. Several perinatal factors were independently associated with an increased OCD risk: breech presentation, cesarean section delivery, gestational age of less than 32 weeks, maternal smoking during pregnancy, Apgar scores near the distress level, and both low and high birth weight (defined as 1,500-2,500 g and greater than 4,500 g, respectively).

“These findings contradict the widely held notion that, although mental disorders share genetic risk factors, the contribution of environmental risk factors is largely disorder specific,” with the exception of maternal smoking during pregnancy, the researchers wrote. In addition, the researchers found a dose-response relationship in which the risk for OCD increased with the greater number of perinatal adverse events.

“The findings are important for the understanding of the cause of OCD and will inform future studies of gene by environment interaction and epigenetics,” the researchers said. “If the finding is replication, the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and OCD may emerge as an interesting disorder-specific risk factor for evaluation in future research,” they added.

Mr. Brander had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Eli Lilly, Shire, and Medice.

Find the full study here: (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2095).

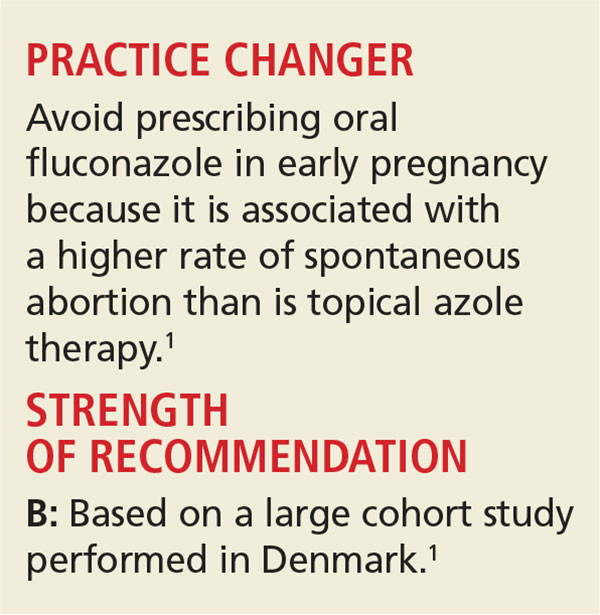

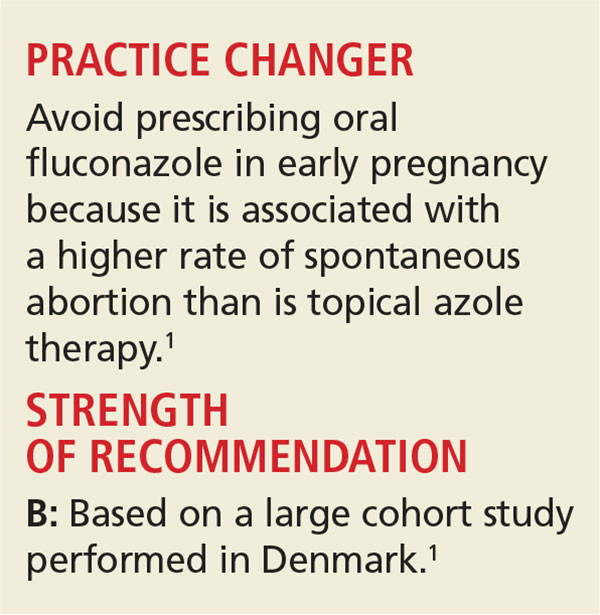

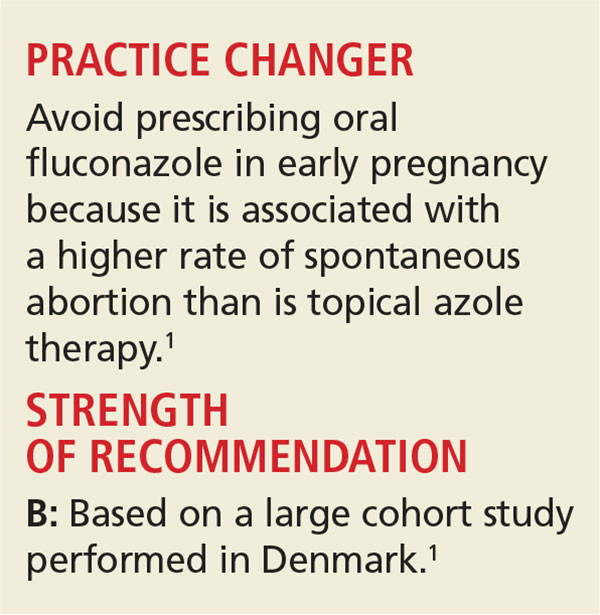

Yeast Infection in Pregnancy? Think Twice About Fluconazole

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

Zika funding slated for prevention, vaccine development

Federal health officials are wasting no time in putting to use long-awaited congressional funding aimed at strengthening Zika prevention and advancing research efforts.

The country’s health care agencies will split the $1.1 billion in funding approved by Congress on Sept. 28, dividing the money among Zika vaccine development, mosquito control, and response to virus outbreaks in the United States and globally, Sylvia Burwell, Health and Human Services secretary, said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“At HHS, we’ll put this funding to use quickly and wisely,” Secretary Burwell said during the press conference. “It will support essential strategies to combat this virus, like expanding mosquito surveillance and control programs. It will also help us further accelerate the development of tests to detect Zika treatment and vaccines, including beginning human testing of additional vaccine candidates. It will also fund vital research as we continue to learn about the virus and monitor the progress of babies born with Zika-related birth defects.”

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million will go to the state of Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will receive $394 million, of which $44 million will go toward replenishing funds pulled from the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement to address the Zika crisis, said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. The CDC’s remaining $350 million will allow the agency to extend existing responses to Zika outbreaks and grow partnerships with state and local authorities.

The National Institutes of Health will use its portion of the Zika funding – $152 million – to further vaccine development and move forward clinical trials already in the works, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The NIH is well on its way with a phase I vaccine trial, having enrolled 80 patients thus far, Dr. Fauci said during the press call. The agency will soon have enough information to determine to move onto phase II, he said.

Meanwhile, HHS will use its portion of the funding – $245 million – to support advanced vaccine development and ensure the drug manufacturing process runs smoothly and quickly, said Nicole Lurie, MD, HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response. Agency officials also plan to support more clinical trials that will be integrated with the ongoing NIH trials, she said.

The remaining funds from the bill will go toward global health programs, operating costs, and other expenses.

Despite the positives from the supplemental funding, Secretary Burwell noted that Congress’ delay in approving the extra money has caused irreparable harm to other health care programs and initiatives. HHS diverted funds from other departments, such as the Administration for Children and Families and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to address Zika outbreaks and begin research. Vaccine and diagnostic developments are also behind because of funding delays, according to officials.

“The damage that occurred because we took those funds will continue,” Secretary Burwell said. “The time and energy that was spent in seeking and working to get the funding instead of working to use the funding [was detrimental]. That money would be out the door if we were in a situation where we had received that money at the point at which we had asked for it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Federal health officials are wasting no time in putting to use long-awaited congressional funding aimed at strengthening Zika prevention and advancing research efforts.

The country’s health care agencies will split the $1.1 billion in funding approved by Congress on Sept. 28, dividing the money among Zika vaccine development, mosquito control, and response to virus outbreaks in the United States and globally, Sylvia Burwell, Health and Human Services secretary, said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“At HHS, we’ll put this funding to use quickly and wisely,” Secretary Burwell said during the press conference. “It will support essential strategies to combat this virus, like expanding mosquito surveillance and control programs. It will also help us further accelerate the development of tests to detect Zika treatment and vaccines, including beginning human testing of additional vaccine candidates. It will also fund vital research as we continue to learn about the virus and monitor the progress of babies born with Zika-related birth defects.”

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million will go to the state of Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will receive $394 million, of which $44 million will go toward replenishing funds pulled from the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement to address the Zika crisis, said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. The CDC’s remaining $350 million will allow the agency to extend existing responses to Zika outbreaks and grow partnerships with state and local authorities.

The National Institutes of Health will use its portion of the Zika funding – $152 million – to further vaccine development and move forward clinical trials already in the works, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The NIH is well on its way with a phase I vaccine trial, having enrolled 80 patients thus far, Dr. Fauci said during the press call. The agency will soon have enough information to determine to move onto phase II, he said.

Meanwhile, HHS will use its portion of the funding – $245 million – to support advanced vaccine development and ensure the drug manufacturing process runs smoothly and quickly, said Nicole Lurie, MD, HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response. Agency officials also plan to support more clinical trials that will be integrated with the ongoing NIH trials, she said.

The remaining funds from the bill will go toward global health programs, operating costs, and other expenses.

Despite the positives from the supplemental funding, Secretary Burwell noted that Congress’ delay in approving the extra money has caused irreparable harm to other health care programs and initiatives. HHS diverted funds from other departments, such as the Administration for Children and Families and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to address Zika outbreaks and begin research. Vaccine and diagnostic developments are also behind because of funding delays, according to officials.

“The damage that occurred because we took those funds will continue,” Secretary Burwell said. “The time and energy that was spent in seeking and working to get the funding instead of working to use the funding [was detrimental]. That money would be out the door if we were in a situation where we had received that money at the point at which we had asked for it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Federal health officials are wasting no time in putting to use long-awaited congressional funding aimed at strengthening Zika prevention and advancing research efforts.

The country’s health care agencies will split the $1.1 billion in funding approved by Congress on Sept. 28, dividing the money among Zika vaccine development, mosquito control, and response to virus outbreaks in the United States and globally, Sylvia Burwell, Health and Human Services secretary, said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“At HHS, we’ll put this funding to use quickly and wisely,” Secretary Burwell said during the press conference. “It will support essential strategies to combat this virus, like expanding mosquito surveillance and control programs. It will also help us further accelerate the development of tests to detect Zika treatment and vaccines, including beginning human testing of additional vaccine candidates. It will also fund vital research as we continue to learn about the virus and monitor the progress of babies born with Zika-related birth defects.”

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million will go to the state of Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will receive $394 million, of which $44 million will go toward replenishing funds pulled from the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement to address the Zika crisis, said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. The CDC’s remaining $350 million will allow the agency to extend existing responses to Zika outbreaks and grow partnerships with state and local authorities.

The National Institutes of Health will use its portion of the Zika funding – $152 million – to further vaccine development and move forward clinical trials already in the works, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The NIH is well on its way with a phase I vaccine trial, having enrolled 80 patients thus far, Dr. Fauci said during the press call. The agency will soon have enough information to determine to move onto phase II, he said.

Meanwhile, HHS will use its portion of the funding – $245 million – to support advanced vaccine development and ensure the drug manufacturing process runs smoothly and quickly, said Nicole Lurie, MD, HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response. Agency officials also plan to support more clinical trials that will be integrated with the ongoing NIH trials, she said.

The remaining funds from the bill will go toward global health programs, operating costs, and other expenses.

Despite the positives from the supplemental funding, Secretary Burwell noted that Congress’ delay in approving the extra money has caused irreparable harm to other health care programs and initiatives. HHS diverted funds from other departments, such as the Administration for Children and Families and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to address Zika outbreaks and begin research. Vaccine and diagnostic developments are also behind because of funding delays, according to officials.

“The damage that occurred because we took those funds will continue,” Secretary Burwell said. “The time and energy that was spent in seeking and working to get the funding instead of working to use the funding [was detrimental]. That money would be out the door if we were in a situation where we had received that money at the point at which we had asked for it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Congenital Zika syndrome includes range of neurologic abnormalities

Researchers have proposed the term “congenital Zika syndrome” to cover the range of severe damage and developmental abnormalities – including microcephaly – caused by Zika virus infection.

In the Oct. 3 online edition of JAMA Neurology, Adriana Suely de Oliveira Melo, MD, PhD, of the Instituto de Pesquisa Professor Amorim Neto in Campina Grande, Brazil, and her coauthors report on 11 babies with congenital Zika virus infection who were followed from gestation to 6 months of age.

Researchers observed hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis and cerebellum in nine patients, while MRI and CT imaging also found that all patients showed callosal hypoplasia, reduced cerebral volume, abnormal cortical development, and subcortical calcifications.

Four of the infants showed gyral disorganization, five showed evidence of pachygyria, and two had lissencephaly (JAMA Neurol. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3720).

“Although there was variable damage resulting from brain lesions associated with [Zika virus] congenital infection, a common pattern of brain atrophy and changes associated with disturbances in neuronal migration were observed,” the authors wrote. “Some patients presented with mild brain atrophy and calcifications, and others presented with more severe malformations, such as the absence of the thalamus and lissencephaly.”

Three of the infants died after delivery, representing a fatality rate of 27.3%. All three were found to have akinesia deformation sequence or arthrogryposis. One of the three pregnancies also involved polyhydramnios, and the infant was delivered at 36 weeks because of severe maternal respiratory distress.

All but one of the pregnant women had reported a skin rash at a median of 9.5 weeks in the pregnancy, suggesting Zika virus infection was acquired early.

Postmortem tissue analysis of two of the infants who died found Zika virus genome in the brain, cerebellum, spinal cord, and lung; a higher viral load in the tissue of one of the infants was associated with more severe brain damage.

Overall, nine patients tested positive for Zika virus using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain

reactions during gestation and/or after birth, while two patients only had serologic evidence of infection.

“It was interesting to note that the viral sequences amplified from patients 1 and 7 after birth gained a new substitution, V23I, which is located in the envelope domain I and may be implicated in viral tropism to different tissues.”

The study was supported by Consellho Nacional de Desenvolvimento e Pesquisa, Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, and Prefeitura Municipal de Campina Grande. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Many unanswered questions remain about Zika virus: How frequently does asymptomatic infection or second- and third-trimester infection lead to CNS disease? What are the long-term sequelae of intrauterine Zika virus infection? What is the reason for the substantial size, severity, and unexpected complications of the recent Zika virus outbreak in the Americas, compared with what has been seen with this virus in the past? And a broader question: How many CNS birth defects presently of unclear cause will be found to be virus induced?

It would be valuable to have adult and pediatric neurologists network with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to establish a surveillance system that could track Zika virus–induced Guillain-Barré syndrome and CNS disease. This would facilitate the identification and characterization of disorders, the formation of a registry, and the mounting of comprehensive epidemiological studies.

Dr. Raymond P. Roos is with the Department of Neurology at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3677). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Many unanswered questions remain about Zika virus: How frequently does asymptomatic infection or second- and third-trimester infection lead to CNS disease? What are the long-term sequelae of intrauterine Zika virus infection? What is the reason for the substantial size, severity, and unexpected complications of the recent Zika virus outbreak in the Americas, compared with what has been seen with this virus in the past? And a broader question: How many CNS birth defects presently of unclear cause will be found to be virus induced?

It would be valuable to have adult and pediatric neurologists network with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to establish a surveillance system that could track Zika virus–induced Guillain-Barré syndrome and CNS disease. This would facilitate the identification and characterization of disorders, the formation of a registry, and the mounting of comprehensive epidemiological studies.

Dr. Raymond P. Roos is with the Department of Neurology at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3677). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Many unanswered questions remain about Zika virus: How frequently does asymptomatic infection or second- and third-trimester infection lead to CNS disease? What are the long-term sequelae of intrauterine Zika virus infection? What is the reason for the substantial size, severity, and unexpected complications of the recent Zika virus outbreak in the Americas, compared with what has been seen with this virus in the past? And a broader question: How many CNS birth defects presently of unclear cause will be found to be virus induced?

It would be valuable to have adult and pediatric neurologists network with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to establish a surveillance system that could track Zika virus–induced Guillain-Barré syndrome and CNS disease. This would facilitate the identification and characterization of disorders, the formation of a registry, and the mounting of comprehensive epidemiological studies.

Dr. Raymond P. Roos is with the Department of Neurology at the University of Chicago. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3677). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Researchers have proposed the term “congenital Zika syndrome” to cover the range of severe damage and developmental abnormalities – including microcephaly – caused by Zika virus infection.

In the Oct. 3 online edition of JAMA Neurology, Adriana Suely de Oliveira Melo, MD, PhD, of the Instituto de Pesquisa Professor Amorim Neto in Campina Grande, Brazil, and her coauthors report on 11 babies with congenital Zika virus infection who were followed from gestation to 6 months of age.

Researchers observed hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis and cerebellum in nine patients, while MRI and CT imaging also found that all patients showed callosal hypoplasia, reduced cerebral volume, abnormal cortical development, and subcortical calcifications.

Four of the infants showed gyral disorganization, five showed evidence of pachygyria, and two had lissencephaly (JAMA Neurol. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3720).

“Although there was variable damage resulting from brain lesions associated with [Zika virus] congenital infection, a common pattern of brain atrophy and changes associated with disturbances in neuronal migration were observed,” the authors wrote. “Some patients presented with mild brain atrophy and calcifications, and others presented with more severe malformations, such as the absence of the thalamus and lissencephaly.”

Three of the infants died after delivery, representing a fatality rate of 27.3%. All three were found to have akinesia deformation sequence or arthrogryposis. One of the three pregnancies also involved polyhydramnios, and the infant was delivered at 36 weeks because of severe maternal respiratory distress.

All but one of the pregnant women had reported a skin rash at a median of 9.5 weeks in the pregnancy, suggesting Zika virus infection was acquired early.

Postmortem tissue analysis of two of the infants who died found Zika virus genome in the brain, cerebellum, spinal cord, and lung; a higher viral load in the tissue of one of the infants was associated with more severe brain damage.

Overall, nine patients tested positive for Zika virus using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain

reactions during gestation and/or after birth, while two patients only had serologic evidence of infection.

“It was interesting to note that the viral sequences amplified from patients 1 and 7 after birth gained a new substitution, V23I, which is located in the envelope domain I and may be implicated in viral tropism to different tissues.”

The study was supported by Consellho Nacional de Desenvolvimento e Pesquisa, Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, and Prefeitura Municipal de Campina Grande. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Researchers have proposed the term “congenital Zika syndrome” to cover the range of severe damage and developmental abnormalities – including microcephaly – caused by Zika virus infection.

In the Oct. 3 online edition of JAMA Neurology, Adriana Suely de Oliveira Melo, MD, PhD, of the Instituto de Pesquisa Professor Amorim Neto in Campina Grande, Brazil, and her coauthors report on 11 babies with congenital Zika virus infection who were followed from gestation to 6 months of age.

Researchers observed hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis and cerebellum in nine patients, while MRI and CT imaging also found that all patients showed callosal hypoplasia, reduced cerebral volume, abnormal cortical development, and subcortical calcifications.

Four of the infants showed gyral disorganization, five showed evidence of pachygyria, and two had lissencephaly (JAMA Neurol. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3720).

“Although there was variable damage resulting from brain lesions associated with [Zika virus] congenital infection, a common pattern of brain atrophy and changes associated with disturbances in neuronal migration were observed,” the authors wrote. “Some patients presented with mild brain atrophy and calcifications, and others presented with more severe malformations, such as the absence of the thalamus and lissencephaly.”

Three of the infants died after delivery, representing a fatality rate of 27.3%. All three were found to have akinesia deformation sequence or arthrogryposis. One of the three pregnancies also involved polyhydramnios, and the infant was delivered at 36 weeks because of severe maternal respiratory distress.

All but one of the pregnant women had reported a skin rash at a median of 9.5 weeks in the pregnancy, suggesting Zika virus infection was acquired early.

Postmortem tissue analysis of two of the infants who died found Zika virus genome in the brain, cerebellum, spinal cord, and lung; a higher viral load in the tissue of one of the infants was associated with more severe brain damage.

Overall, nine patients tested positive for Zika virus using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain

reactions during gestation and/or after birth, while two patients only had serologic evidence of infection.

“It was interesting to note that the viral sequences amplified from patients 1 and 7 after birth gained a new substitution, V23I, which is located in the envelope domain I and may be implicated in viral tropism to different tissues.”

The study was supported by Consellho Nacional de Desenvolvimento e Pesquisa, Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, and Prefeitura Municipal de Campina Grande. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Congenital Zika syndrome is associated with microcephaly, reduced cerebral volume, cerebellar hypoplasia, lissencephaly with hydrocephalus, and fetal akinesia deformation sequence.

Data source: Prospective study of 11 Zika-affected infants followed from gestation to 6 months of age.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Consellho Nacional de Desenvolvimento e Pesquisa, Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, and Prefeitura Municipal de Campina Grande. No conflicts of interest were declared.

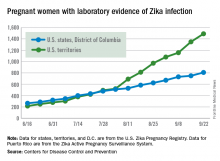

Zika virus shows no signs of slowing down

Zika virus transmission continues at a rapid clip as the number of new cases among pregnant women topped 200 again for the week ending Sept. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After setting a new high of 210 the previous week, there were 201 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 22. There were 59 new cases in the 50 states and the District of Columbia and 142 new cases in the U.S. territories, the CDC reported Sept. 29. In the United States this year, there have been 2,298 reported cases of Zika-infected pregnant women: 808 in the states and D.C. and 1,490 in the territories.

Among all Americans, there were 2,559 new cases of Zika infection as of Sept. 28 – 267 in the states/D.C. and 2,292 in the territories – although Puerto Rico continues to retroactively report cases, which has been pushing the numbers higher in recent weeks. There have been 25,694 total cases of Zika infection in 2015-2016, the CDC reported.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus transmission continues at a rapid clip as the number of new cases among pregnant women topped 200 again for the week ending Sept. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After setting a new high of 210 the previous week, there were 201 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 22. There were 59 new cases in the 50 states and the District of Columbia and 142 new cases in the U.S. territories, the CDC reported Sept. 29. In the United States this year, there have been 2,298 reported cases of Zika-infected pregnant women: 808 in the states and D.C. and 1,490 in the territories.

Among all Americans, there were 2,559 new cases of Zika infection as of Sept. 28 – 267 in the states/D.C. and 2,292 in the territories – although Puerto Rico continues to retroactively report cases, which has been pushing the numbers higher in recent weeks. There have been 25,694 total cases of Zika infection in 2015-2016, the CDC reported.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus transmission continues at a rapid clip as the number of new cases among pregnant women topped 200 again for the week ending Sept. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After setting a new high of 210 the previous week, there were 201 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 22. There were 59 new cases in the 50 states and the District of Columbia and 142 new cases in the U.S. territories, the CDC reported Sept. 29. In the United States this year, there have been 2,298 reported cases of Zika-infected pregnant women: 808 in the states and D.C. and 1,490 in the territories.

Among all Americans, there were 2,559 new cases of Zika infection as of Sept. 28 – 267 in the states/D.C. and 2,292 in the territories – although Puerto Rico continues to retroactively report cases, which has been pushing the numbers higher in recent weeks. There have been 25,694 total cases of Zika infection in 2015-2016, the CDC reported.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

New FASD diagnosis guidelines: Comprehensive or overly broad?

One of the most challenging elements in making a diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is obtaining a thorough history of the mother’s drinking during pregnancy. This is something that ob.gyns. have struggled with for many years, and while there are ways to improve the collection of this information, it’s often an uncomfortable conversation that yields unreliable answers.

In August, a group of experts on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), organized by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, proposed new clinical guidelines for diagnosing these disorders, the first update since 2005 (Pediatrics. 2016;138[2]:e20154256). The update creates a more inclusive definition of FASD and puts a greater emphasis on the sometimes subtle physical and behavioral changes that occur in children.

Growth restriction

The updated diagnosis begins with the acknowledgment of maternal drinking during pregnancy and growth restriction in the infant, which the new guidelines set at the 10th percentile. That’s an important change because it significantly increases sensitivity, expanding the number of infants who could be diagnosed by raising the growth restriction threshold from the third percentile. Clinicians must take into account other factors, such as the size of the natural parents and whether growth restriction could be caused by other conditions.

Facial changes

A key component on the FASD diagnosis is the assessment of facial changes. The three typical facial changes that have been used to make this diagnosis since the 1970s include short palpebral fissures, a shallow or lack of philtrum, and a thin vermilion border of the upper lip. Previously, if all three of these facial features were present, a history of maternal drinking was not needed in the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome. If two of the three features were present, it was considered partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Now, if maternal drinking has been determined, it’s not necessary to have all three facial features to make a diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome.

For the first time, the guidelines describe other facial changes common in FASD that can be used to diagnose partial fetal alcohol syndrome, including a flat nasal bridge, epicanthal folds, and other signs. Again, the guidelines increase sensitivity and make it likely that more cases will be picked up through these criteria.

Neurobehavioral changes

The most devastating part of FASD are the complex neurobehavioral changes, resulting from damage to the fetal brain. Under the updated guidelines, the authors relaxed the criteria so that children can be diagnosed if they have domains of either intellectual impairment or behavioral changes that are 1.5 standard deviations below the age-adjusted mean, rather than the previous 2 standard deviations.

The challenge with making this change is that unlike with the facial changes, there’s a lack of specificity in assessing intellectual impairment and behavioral changes. In addition, these issues often emerge with other conditions unrelated to fetal exposure to alcohol.

Sensitivity vs. specificity

Statistically, the authors of the updated guidelines have moved to increase sensitivity, reaching more children who need interventions for the devastating manifestations of FASD. But the price of this expansion of the diagnostic criteria is a decrease in specificity. The authors seek to combat this potential lack of specificity by emphasizing that an FASD diagnosis should be made not by a single clinician but by a multidisciplinary team that includes physicians, a psychologist, social worker, and speech and language specialists.

While a specialized team will certainly help to make a better diagnosis, the literature shows very large variability in obtaining FASD diagnosis by using different guidelines. A May 2016 paper in Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research found wide diagnostic variation of between roughly 5% (using guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and 60% (using 2006 guidelines from Hoyme et al.) in the same group of alcohol- and drug-exposed children, when five different guidelines were used (doi: 10.1111/acer.13032). This type of variation would not be acceptable in other conditions, such as autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and it highlights a serious unresolved gap in advancing FASD.

Ob.gyn. role

The role for the ob.gyn. is a complicated one, both in terms of diagnosis and prevention of FASD. Quite often the mother is abusing both alcohol and drugs and the infant may be at risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome in addition to FASD. And because alcohol abuse is often chronic, this is an issue that could affect future children.

While there are still many unanswered questions on the genetics of FASD, we do know that it’s not an equal opportunity condition. Mothers who have had a child with the syndrome have a higher likelihood of its occurring with a second child, compared with mothers who drink heavily but did not have a previous child with FASD.

For now, it’s imperative that ob.gyns. continue to ask about drinking in a nonjudgmental way and that they ask this question of all their patients, not just ones they consider to be in high risk populations.

Dr. Koren is professor of physiology/pharmacology at Western University in Ontario. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

One of the most challenging elements in making a diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is obtaining a thorough history of the mother’s drinking during pregnancy. This is something that ob.gyns. have struggled with for many years, and while there are ways to improve the collection of this information, it’s often an uncomfortable conversation that yields unreliable answers.

In August, a group of experts on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), organized by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, proposed new clinical guidelines for diagnosing these disorders, the first update since 2005 (Pediatrics. 2016;138[2]:e20154256). The update creates a more inclusive definition of FASD and puts a greater emphasis on the sometimes subtle physical and behavioral changes that occur in children.

Growth restriction

The updated diagnosis begins with the acknowledgment of maternal drinking during pregnancy and growth restriction in the infant, which the new guidelines set at the 10th percentile. That’s an important change because it significantly increases sensitivity, expanding the number of infants who could be diagnosed by raising the growth restriction threshold from the third percentile. Clinicians must take into account other factors, such as the size of the natural parents and whether growth restriction could be caused by other conditions.

Facial changes

A key component on the FASD diagnosis is the assessment of facial changes. The three typical facial changes that have been used to make this diagnosis since the 1970s include short palpebral fissures, a shallow or lack of philtrum, and a thin vermilion border of the upper lip. Previously, if all three of these facial features were present, a history of maternal drinking was not needed in the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome. If two of the three features were present, it was considered partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Now, if maternal drinking has been determined, it’s not necessary to have all three facial features to make a diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome.

For the first time, the guidelines describe other facial changes common in FASD that can be used to diagnose partial fetal alcohol syndrome, including a flat nasal bridge, epicanthal folds, and other signs. Again, the guidelines increase sensitivity and make it likely that more cases will be picked up through these criteria.

Neurobehavioral changes

The most devastating part of FASD are the complex neurobehavioral changes, resulting from damage to the fetal brain. Under the updated guidelines, the authors relaxed the criteria so that children can be diagnosed if they have domains of either intellectual impairment or behavioral changes that are 1.5 standard deviations below the age-adjusted mean, rather than the previous 2 standard deviations.

The challenge with making this change is that unlike with the facial changes, there’s a lack of specificity in assessing intellectual impairment and behavioral changes. In addition, these issues often emerge with other conditions unrelated to fetal exposure to alcohol.

Sensitivity vs. specificity

Statistically, the authors of the updated guidelines have moved to increase sensitivity, reaching more children who need interventions for the devastating manifestations of FASD. But the price of this expansion of the diagnostic criteria is a decrease in specificity. The authors seek to combat this potential lack of specificity by emphasizing that an FASD diagnosis should be made not by a single clinician but by a multidisciplinary team that includes physicians, a psychologist, social worker, and speech and language specialists.

While a specialized team will certainly help to make a better diagnosis, the literature shows very large variability in obtaining FASD diagnosis by using different guidelines. A May 2016 paper in Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research found wide diagnostic variation of between roughly 5% (using guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and 60% (using 2006 guidelines from Hoyme et al.) in the same group of alcohol- and drug-exposed children, when five different guidelines were used (doi: 10.1111/acer.13032). This type of variation would not be acceptable in other conditions, such as autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and it highlights a serious unresolved gap in advancing FASD.

Ob.gyn. role

The role for the ob.gyn. is a complicated one, both in terms of diagnosis and prevention of FASD. Quite often the mother is abusing both alcohol and drugs and the infant may be at risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome in addition to FASD. And because alcohol abuse is often chronic, this is an issue that could affect future children.

While there are still many unanswered questions on the genetics of FASD, we do know that it’s not an equal opportunity condition. Mothers who have had a child with the syndrome have a higher likelihood of its occurring with a second child, compared with mothers who drink heavily but did not have a previous child with FASD.

For now, it’s imperative that ob.gyns. continue to ask about drinking in a nonjudgmental way and that they ask this question of all their patients, not just ones they consider to be in high risk populations.

Dr. Koren is professor of physiology/pharmacology at Western University in Ontario. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

One of the most challenging elements in making a diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is obtaining a thorough history of the mother’s drinking during pregnancy. This is something that ob.gyns. have struggled with for many years, and while there are ways to improve the collection of this information, it’s often an uncomfortable conversation that yields unreliable answers.

In August, a group of experts on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), organized by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, proposed new clinical guidelines for diagnosing these disorders, the first update since 2005 (Pediatrics. 2016;138[2]:e20154256). The update creates a more inclusive definition of FASD and puts a greater emphasis on the sometimes subtle physical and behavioral changes that occur in children.

Growth restriction

The updated diagnosis begins with the acknowledgment of maternal drinking during pregnancy and growth restriction in the infant, which the new guidelines set at the 10th percentile. That’s an important change because it significantly increases sensitivity, expanding the number of infants who could be diagnosed by raising the growth restriction threshold from the third percentile. Clinicians must take into account other factors, such as the size of the natural parents and whether growth restriction could be caused by other conditions.

Facial changes

A key component on the FASD diagnosis is the assessment of facial changes. The three typical facial changes that have been used to make this diagnosis since the 1970s include short palpebral fissures, a shallow or lack of philtrum, and a thin vermilion border of the upper lip. Previously, if all three of these facial features were present, a history of maternal drinking was not needed in the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome. If two of the three features were present, it was considered partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Now, if maternal drinking has been determined, it’s not necessary to have all three facial features to make a diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome.

For the first time, the guidelines describe other facial changes common in FASD that can be used to diagnose partial fetal alcohol syndrome, including a flat nasal bridge, epicanthal folds, and other signs. Again, the guidelines increase sensitivity and make it likely that more cases will be picked up through these criteria.

Neurobehavioral changes

The most devastating part of FASD are the complex neurobehavioral changes, resulting from damage to the fetal brain. Under the updated guidelines, the authors relaxed the criteria so that children can be diagnosed if they have domains of either intellectual impairment or behavioral changes that are 1.5 standard deviations below the age-adjusted mean, rather than the previous 2 standard deviations.

The challenge with making this change is that unlike with the facial changes, there’s a lack of specificity in assessing intellectual impairment and behavioral changes. In addition, these issues often emerge with other conditions unrelated to fetal exposure to alcohol.

Sensitivity vs. specificity

Statistically, the authors of the updated guidelines have moved to increase sensitivity, reaching more children who need interventions for the devastating manifestations of FASD. But the price of this expansion of the diagnostic criteria is a decrease in specificity. The authors seek to combat this potential lack of specificity by emphasizing that an FASD diagnosis should be made not by a single clinician but by a multidisciplinary team that includes physicians, a psychologist, social worker, and speech and language specialists.

While a specialized team will certainly help to make a better diagnosis, the literature shows very large variability in obtaining FASD diagnosis by using different guidelines. A May 2016 paper in Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research found wide diagnostic variation of between roughly 5% (using guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and 60% (using 2006 guidelines from Hoyme et al.) in the same group of alcohol- and drug-exposed children, when five different guidelines were used (doi: 10.1111/acer.13032). This type of variation would not be acceptable in other conditions, such as autism or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and it highlights a serious unresolved gap in advancing FASD.

Ob.gyn. role

The role for the ob.gyn. is a complicated one, both in terms of diagnosis and prevention of FASD. Quite often the mother is abusing both alcohol and drugs and the infant may be at risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome in addition to FASD. And because alcohol abuse is often chronic, this is an issue that could affect future children.

While there are still many unanswered questions on the genetics of FASD, we do know that it’s not an equal opportunity condition. Mothers who have had a child with the syndrome have a higher likelihood of its occurring with a second child, compared with mothers who drink heavily but did not have a previous child with FASD.

For now, it’s imperative that ob.gyns. continue to ask about drinking in a nonjudgmental way and that they ask this question of all their patients, not just ones they consider to be in high risk populations.

Dr. Koren is professor of physiology/pharmacology at Western University in Ontario. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

The importance of studying the placenta

It makes logical, intellectual sense that the placenta, an organ that is so integrally involved in pregnancy, will be of such great importance to the well-being, sustenance, and growth and development of the fetus. After all, the placental compartment and fetal compartment have the same origin early in embryogenesis, and the placenta is the sole source of nutrients and oxygen for the fetus.

However, the placenta has been extraordinarily poorly understood. Much of medicine has regarded the placenta like the appendix – an organ that may be easily discarded. We know too little about its functions and its biology. We do not even know whether there is a minimum amount of placenta that’s necessary for fetal health.

Over the years, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has placed an emphasis on certain key areas of study through efforts such as the Human Genome Project, the BRAIN Initiative, and the Cancer Moonshot. Such efforts involve sustained, fundamental research and usually lead to significant findings and subsequent application of the findings.

It is exciting to know that the NIH has launched its Human Placenta Project in an effort to better understand the biology of the placenta and to elucidate its functions. The technology that is employed will play an adjunctive role.

Fortunately, over the years various investigators have studied the placenta using ultrasound, color Doppler technology, and other techniques, and have reported important findings. The work of pathologist Carolyn M. Salafia, MD, and others has called attention to the importance of the shape and vasculature of the placenta, as well as blood flow.

To bring us up to date, as the NIH’s Human Placenta Project proceeds, I have asked Dr. Salafia to provide us with a review discussion of our current knowledge and its implications. Dr. Salafia specializes in reproductive and developmental pathology and reviews thousands of placentas each year through her work with various hospitals and as head of the Placental Modulation Laboratory at the Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities in Staten Island, N.Y.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

It makes logical, intellectual sense that the placenta, an organ that is so integrally involved in pregnancy, will be of such great importance to the well-being, sustenance, and growth and development of the fetus. After all, the placental compartment and fetal compartment have the same origin early in embryogenesis, and the placenta is the sole source of nutrients and oxygen for the fetus.

However, the placenta has been extraordinarily poorly understood. Much of medicine has regarded the placenta like the appendix – an organ that may be easily discarded. We know too little about its functions and its biology. We do not even know whether there is a minimum amount of placenta that’s necessary for fetal health.

Over the years, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has placed an emphasis on certain key areas of study through efforts such as the Human Genome Project, the BRAIN Initiative, and the Cancer Moonshot. Such efforts involve sustained, fundamental research and usually lead to significant findings and subsequent application of the findings.

It is exciting to know that the NIH has launched its Human Placenta Project in an effort to better understand the biology of the placenta and to elucidate its functions. The technology that is employed will play an adjunctive role.

Fortunately, over the years various investigators have studied the placenta using ultrasound, color Doppler technology, and other techniques, and have reported important findings. The work of pathologist Carolyn M. Salafia, MD, and others has called attention to the importance of the shape and vasculature of the placenta, as well as blood flow.

To bring us up to date, as the NIH’s Human Placenta Project proceeds, I have asked Dr. Salafia to provide us with a review discussion of our current knowledge and its implications. Dr. Salafia specializes in reproductive and developmental pathology and reviews thousands of placentas each year through her work with various hospitals and as head of the Placental Modulation Laboratory at the Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities in Staten Island, N.Y.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].