User login

Eculizumab benefited pregnant women with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Eculizumab therapy led to “acceptable” outcomes among pregnant women with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, investigators reported Sept. 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

No woman who received eculizumab died while pregnant or within 6 months of delivery; historic mortality rates for these patients are 8%-20%, said Dr. Richard Kelly at St. James’s University Hospital in Leeds, England, and his associates. Treatment with the monoclonal antibody, “has reduced mortality and morbidity associated with PNH and has allowed patients who were previously severely affected to lead a relatively normal life.”

The fetal death rate was 4%, resembling rates of 4%-9% from the era before eculizumab, the researchers said. The rate of premature births also was high (29%) as a result of preeclampsia, suspected intrauterine growth retardation, maternal thrombocytopenia, and slowed fetal movements, they said.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is a rare, chronic stem-cell disease in which complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis causes anemia, fatigue, and venous thromboembolism (Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;735:155-72.). Increased complement activation during pregnancy intensifies the risk of severe hemolytic anemia, fetal morbidity, and fetal mortality for women with PNH. Eculizumab blocks terminal complement activation by binding complement protein C5, and has improved PNH symptoms to the extent that treated women are more likely to consider pregnancy than in the past.

Dr. Kelly and his associates surveyed members of the International PNH Interest Group to study pregnancy outcomes among these women (N Engl J. Med. 2015;373:1032-9). A total of 80% of clinicians responded, reporting data for 75 pregnancies among 61 women, the investigators said. All patients had PNH diagnosed by flow cytometry, and 61% had begun eculizumab therapy before conception. Median age at first pregnancy was 29 years, with a range of 18 to 40 years. The patients received weekly 600-mg IV infusions for 4 weeks, followed by 900 mg every 14 days. Clinicians increased the dose or treatment frequency at their own discretion if patients showed signs of breakthrough intravascular hemolysis.

Two women experienced thrombotic events during treatment, both of which happened soon after delivery. One was a lower-limb deep venous thrombosis, but the other occurred after a patient received a plasma infusion for postpartum hemorrhage. “Plasma contains high levels of complement and can overcome the effects of eculizumab and thereby render the patient susceptible to complications of PNH,” noted the investigators. “The use of plasma should thus be avoided if possible.” Ten samples of breast milk were negative for eculizumab, they added.

Dr. Kelly and 14 of 15 coauthors reported financial relationships outside this work with Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the maker of eculizumab. One coauthor also reported grant support outside this work from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Ra Pharma.

Eculizumab therapy led to “acceptable” outcomes among pregnant women with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, investigators reported Sept. 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

No woman who received eculizumab died while pregnant or within 6 months of delivery; historic mortality rates for these patients are 8%-20%, said Dr. Richard Kelly at St. James’s University Hospital in Leeds, England, and his associates. Treatment with the monoclonal antibody, “has reduced mortality and morbidity associated with PNH and has allowed patients who were previously severely affected to lead a relatively normal life.”

The fetal death rate was 4%, resembling rates of 4%-9% from the era before eculizumab, the researchers said. The rate of premature births also was high (29%) as a result of preeclampsia, suspected intrauterine growth retardation, maternal thrombocytopenia, and slowed fetal movements, they said.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is a rare, chronic stem-cell disease in which complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis causes anemia, fatigue, and venous thromboembolism (Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;735:155-72.). Increased complement activation during pregnancy intensifies the risk of severe hemolytic anemia, fetal morbidity, and fetal mortality for women with PNH. Eculizumab blocks terminal complement activation by binding complement protein C5, and has improved PNH symptoms to the extent that treated women are more likely to consider pregnancy than in the past.

Dr. Kelly and his associates surveyed members of the International PNH Interest Group to study pregnancy outcomes among these women (N Engl J. Med. 2015;373:1032-9). A total of 80% of clinicians responded, reporting data for 75 pregnancies among 61 women, the investigators said. All patients had PNH diagnosed by flow cytometry, and 61% had begun eculizumab therapy before conception. Median age at first pregnancy was 29 years, with a range of 18 to 40 years. The patients received weekly 600-mg IV infusions for 4 weeks, followed by 900 mg every 14 days. Clinicians increased the dose or treatment frequency at their own discretion if patients showed signs of breakthrough intravascular hemolysis.

Two women experienced thrombotic events during treatment, both of which happened soon after delivery. One was a lower-limb deep venous thrombosis, but the other occurred after a patient received a plasma infusion for postpartum hemorrhage. “Plasma contains high levels of complement and can overcome the effects of eculizumab and thereby render the patient susceptible to complications of PNH,” noted the investigators. “The use of plasma should thus be avoided if possible.” Ten samples of breast milk were negative for eculizumab, they added.

Dr. Kelly and 14 of 15 coauthors reported financial relationships outside this work with Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the maker of eculizumab. One coauthor also reported grant support outside this work from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Ra Pharma.

Eculizumab therapy led to “acceptable” outcomes among pregnant women with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, investigators reported Sept. 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

No woman who received eculizumab died while pregnant or within 6 months of delivery; historic mortality rates for these patients are 8%-20%, said Dr. Richard Kelly at St. James’s University Hospital in Leeds, England, and his associates. Treatment with the monoclonal antibody, “has reduced mortality and morbidity associated with PNH and has allowed patients who were previously severely affected to lead a relatively normal life.”

The fetal death rate was 4%, resembling rates of 4%-9% from the era before eculizumab, the researchers said. The rate of premature births also was high (29%) as a result of preeclampsia, suspected intrauterine growth retardation, maternal thrombocytopenia, and slowed fetal movements, they said.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is a rare, chronic stem-cell disease in which complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis causes anemia, fatigue, and venous thromboembolism (Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;735:155-72.). Increased complement activation during pregnancy intensifies the risk of severe hemolytic anemia, fetal morbidity, and fetal mortality for women with PNH. Eculizumab blocks terminal complement activation by binding complement protein C5, and has improved PNH symptoms to the extent that treated women are more likely to consider pregnancy than in the past.

Dr. Kelly and his associates surveyed members of the International PNH Interest Group to study pregnancy outcomes among these women (N Engl J. Med. 2015;373:1032-9). A total of 80% of clinicians responded, reporting data for 75 pregnancies among 61 women, the investigators said. All patients had PNH diagnosed by flow cytometry, and 61% had begun eculizumab therapy before conception. Median age at first pregnancy was 29 years, with a range of 18 to 40 years. The patients received weekly 600-mg IV infusions for 4 weeks, followed by 900 mg every 14 days. Clinicians increased the dose or treatment frequency at their own discretion if patients showed signs of breakthrough intravascular hemolysis.

Two women experienced thrombotic events during treatment, both of which happened soon after delivery. One was a lower-limb deep venous thrombosis, but the other occurred after a patient received a plasma infusion for postpartum hemorrhage. “Plasma contains high levels of complement and can overcome the effects of eculizumab and thereby render the patient susceptible to complications of PNH,” noted the investigators. “The use of plasma should thus be avoided if possible.” Ten samples of breast milk were negative for eculizumab, they added.

Dr. Kelly and 14 of 15 coauthors reported financial relationships outside this work with Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the maker of eculizumab. One coauthor also reported grant support outside this work from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Ra Pharma.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: None of the pregnant women with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria died on eculizumab therapy.

Major finding: The fetal death rate was 4%, and the premature birth rate was 29%.

Data source: A retrospective, survey-based study of 75 pregnancies among 61 women with PNH.

Disclosures: Dr. Kelly and 14 of 15 coauthors reported financial relationships outside this work with Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the maker of eculizumab. One coauthor also reported grant support outside this work from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Ra Pharma.

Better outcomes seen for some extremely preterm infants

There has been a significant increase in survival without major neonatal morbidity for infants born at 25-28 weeks’ gestation in the United States in the past 2 decades, researchers reported online Sept. 8 in JAMA.

Survival without major complications improved by about 2% per year for these babies, said Dr. Barbara Stoll of Emory University in Atlanta and her associates. But outcomes for earlier preterm births were mixed. “Although overall survival increased for infants aged 23 and 24 weeks, few infants younger than 25 weeks’ gestational age survived without major neonatal morbidity, underscoring the continued need for interventions to improve outcomes for the most immature infants,” the investigators said.

Despite advances in perinatal care, preterm infants face disproportionate rates of morbidity and mortality. The investigators studied outcomes for 34,636 such babies who were born between 1993 and 2012 at 26 U.S. Neonatal Research Network centers, including 8 that participated for the entire study. All the infants were born at 22-28 weeks’ gestation and weighed 401-1,500 g at birth (JAMA 2015;314[10]:1039-51).

“The percent of infants from a multiple birth increased from 18% in 1993 to 27% in 1998 (P less than .001),with no further increase noted,” Dr. Stoll and her associates reported.

Between 2009 and 2012, survival improved the most for infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation (from 27% to 33%) and at 24 weeks’ gestation (from 63% to 65%). But survival increased only slightly for infants born at 25 and 27 weeks’ gestation, and remained static for infants born at 22, 26, and 28 weeks. Furthermore, although survival without major morbidity improved markedly for infants born at 25-28 weeks, it did not change for those born at 24 weeks.

Rates of late-onset sepsis fell among all gestational age groups, but bronchopulmonary dysplasia rose significantly (P less than .001). The latter “may partly be explained by increased active resuscitation, intensive care, and increased survival, especially for the most immature infants,” the investigators said. Use of prenatal corticosteroids rose from 24% to 87% during the study period (P less than .001), as did rates of cesarean delivery (from 44% to 64%; P less than .001), they added.

The preterm registry used in the study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Research Resources, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported no financial disclosures.

This article provides an important historical perspective over the last 2 decades in neonatal-perinatal medicine and the most recent update on trends in neonatal care. Although there has been progress, it is clear that there are still a substantial number of extremely preterm infants who either die or survive after experiencing one or more major neonatal morbidities known to be associated with both short- and long-term adverse consequences. Hence, an additional commitment must be made to further improvements.

There is no obvious breakthrough therapy emerging in the coming years. Perhaps cellular therapy, such as mesenchymal stem cells, will be an important advance in the care of these fragile infants. However, it is more likely that incremental change, such as applying quality improvement practices to outcomes other than nosocomial infection, will lead to improved outcomes.

Dr. Roger F. Soll is at the neonatal-perinatal medicine division, department of pediatrics, University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington. These comments were excerpted from his accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015;314[10]:1007-8). He reported receiving personal fees from the Vermont Oxford Network outside this work.

This article provides an important historical perspective over the last 2 decades in neonatal-perinatal medicine and the most recent update on trends in neonatal care. Although there has been progress, it is clear that there are still a substantial number of extremely preterm infants who either die or survive after experiencing one or more major neonatal morbidities known to be associated with both short- and long-term adverse consequences. Hence, an additional commitment must be made to further improvements.

There is no obvious breakthrough therapy emerging in the coming years. Perhaps cellular therapy, such as mesenchymal stem cells, will be an important advance in the care of these fragile infants. However, it is more likely that incremental change, such as applying quality improvement practices to outcomes other than nosocomial infection, will lead to improved outcomes.

Dr. Roger F. Soll is at the neonatal-perinatal medicine division, department of pediatrics, University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington. These comments were excerpted from his accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015;314[10]:1007-8). He reported receiving personal fees from the Vermont Oxford Network outside this work.

This article provides an important historical perspective over the last 2 decades in neonatal-perinatal medicine and the most recent update on trends in neonatal care. Although there has been progress, it is clear that there are still a substantial number of extremely preterm infants who either die or survive after experiencing one or more major neonatal morbidities known to be associated with both short- and long-term adverse consequences. Hence, an additional commitment must be made to further improvements.

There is no obvious breakthrough therapy emerging in the coming years. Perhaps cellular therapy, such as mesenchymal stem cells, will be an important advance in the care of these fragile infants. However, it is more likely that incremental change, such as applying quality improvement practices to outcomes other than nosocomial infection, will lead to improved outcomes.

Dr. Roger F. Soll is at the neonatal-perinatal medicine division, department of pediatrics, University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington. These comments were excerpted from his accompanying editorial (JAMA 2015;314[10]:1007-8). He reported receiving personal fees from the Vermont Oxford Network outside this work.

There has been a significant increase in survival without major neonatal morbidity for infants born at 25-28 weeks’ gestation in the United States in the past 2 decades, researchers reported online Sept. 8 in JAMA.

Survival without major complications improved by about 2% per year for these babies, said Dr. Barbara Stoll of Emory University in Atlanta and her associates. But outcomes for earlier preterm births were mixed. “Although overall survival increased for infants aged 23 and 24 weeks, few infants younger than 25 weeks’ gestational age survived without major neonatal morbidity, underscoring the continued need for interventions to improve outcomes for the most immature infants,” the investigators said.

Despite advances in perinatal care, preterm infants face disproportionate rates of morbidity and mortality. The investigators studied outcomes for 34,636 such babies who were born between 1993 and 2012 at 26 U.S. Neonatal Research Network centers, including 8 that participated for the entire study. All the infants were born at 22-28 weeks’ gestation and weighed 401-1,500 g at birth (JAMA 2015;314[10]:1039-51).

“The percent of infants from a multiple birth increased from 18% in 1993 to 27% in 1998 (P less than .001),with no further increase noted,” Dr. Stoll and her associates reported.

Between 2009 and 2012, survival improved the most for infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation (from 27% to 33%) and at 24 weeks’ gestation (from 63% to 65%). But survival increased only slightly for infants born at 25 and 27 weeks’ gestation, and remained static for infants born at 22, 26, and 28 weeks. Furthermore, although survival without major morbidity improved markedly for infants born at 25-28 weeks, it did not change for those born at 24 weeks.

Rates of late-onset sepsis fell among all gestational age groups, but bronchopulmonary dysplasia rose significantly (P less than .001). The latter “may partly be explained by increased active resuscitation, intensive care, and increased survival, especially for the most immature infants,” the investigators said. Use of prenatal corticosteroids rose from 24% to 87% during the study period (P less than .001), as did rates of cesarean delivery (from 44% to 64%; P less than .001), they added.

The preterm registry used in the study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Research Resources, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported no financial disclosures.

There has been a significant increase in survival without major neonatal morbidity for infants born at 25-28 weeks’ gestation in the United States in the past 2 decades, researchers reported online Sept. 8 in JAMA.

Survival without major complications improved by about 2% per year for these babies, said Dr. Barbara Stoll of Emory University in Atlanta and her associates. But outcomes for earlier preterm births were mixed. “Although overall survival increased for infants aged 23 and 24 weeks, few infants younger than 25 weeks’ gestational age survived without major neonatal morbidity, underscoring the continued need for interventions to improve outcomes for the most immature infants,” the investigators said.

Despite advances in perinatal care, preterm infants face disproportionate rates of morbidity and mortality. The investigators studied outcomes for 34,636 such babies who were born between 1993 and 2012 at 26 U.S. Neonatal Research Network centers, including 8 that participated for the entire study. All the infants were born at 22-28 weeks’ gestation and weighed 401-1,500 g at birth (JAMA 2015;314[10]:1039-51).

“The percent of infants from a multiple birth increased from 18% in 1993 to 27% in 1998 (P less than .001),with no further increase noted,” Dr. Stoll and her associates reported.

Between 2009 and 2012, survival improved the most for infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation (from 27% to 33%) and at 24 weeks’ gestation (from 63% to 65%). But survival increased only slightly for infants born at 25 and 27 weeks’ gestation, and remained static for infants born at 22, 26, and 28 weeks. Furthermore, although survival without major morbidity improved markedly for infants born at 25-28 weeks, it did not change for those born at 24 weeks.

Rates of late-onset sepsis fell among all gestational age groups, but bronchopulmonary dysplasia rose significantly (P less than .001). The latter “may partly be explained by increased active resuscitation, intensive care, and increased survival, especially for the most immature infants,” the investigators said. Use of prenatal corticosteroids rose from 24% to 87% during the study period (P less than .001), as did rates of cesarean delivery (from 44% to 64%; P less than .001), they added.

The preterm registry used in the study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Research Resources, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: There has been a significant increase in survival without major neonatal morbidity for infants born at 25-28 weeks’ gestation in the United States in the past 2 decades.

Major finding: Survival without major morbidity rose by about 2% per year for infants born at 25-28 weeks’ gestation.

Data source: A prospective registry study of 34,636 extremely preterm infants born at U.S. academic centers between 1993 and 2012.

Disclosures: The preterm registry used in the study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Research Resources, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators reported no financial disclosures.

USPSTF silent on iron supplementation in pregnancy

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force announced, in a recommendation on Sept. 7, that it is unsure whether pregnant women who are asymptomatic for iron deficiency anemia should be screened for this condition or take iron supplements.

The recommendation is an update to the 2006 USPSTF recommendation, which also expressed uncertainty on whether iron supplementation is beneficial to pregnant women.

“Both the 2006 and the current recommendation statements found insufficient evidence to determine the balance of the benefits and harms of iron supplementation during pregnancy,” Dr. Albert L. Siu wrote on behalf of members of the USPSTF.

The 2006 recommendation differed from the current one in that it had advocated for routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women.

“In its review of the evidence to update the 2006 recommendation, the USPSTF found no good- or fair-quality studies on the benefits or harms of screening that would be applicable to the current U.S. population of pregnant women,” according to the task force recommendation statement published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF based the updated recommendation on a systematic evidence review, which focused on whether pregnant women and adolescents’ use of oral iron supplementation or treatment was associated with changes in iron status and improvement in maternal and infant health outcomes. It reviewed “studies conducted in settings similar to the United States in rates of malnutrition, hemoparasite burden, and general socioeconomic status.”

The USPSTF’s review included 12 “good- or fair-quality randomized controlled trials,” which evaluated the effects of iron supplementation on various maternal hematologic indexes, including hemoglobin level, serum ferritin level, anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia.

Eight of the studies reported maternal hemoglobin levels at term or delivery, with six of the studies having reported a significantly higher mean hemoglobin level in the supplemented groups than in the control groups (122-139 g/L vs. 115-128 g/L, respectively). Seven studies reported serum ferritin levels at term or delivery, with five of these having reported a significantly higher ferritin level in the supplemented groups, compared with the control groups (12.0-30.0 mcg/L vs. 6.2-24.9 mcg/L, respectively).

“Although adequate evidence shows that [iron] supplementation increases hemoglobin and ferritin levels, the evidence is unclear on whether this increase leads to an improvement in maternal and fetal outcomes. In most of these studies, the supplemented groups had higher mean hemoglobin levels than the nonsupplemented groups; however, both groups reported values within normal limits,” the USPSTF wrote.

Research on the harmful effects of iron supplementation in pregnant women better addressed the USPSTF’s questions; 10 of the trials showed that the harms of iron supplementation during pregnancy were “small to none,” with most of the harms reported having been nausea, constipation, and diarrhea.

While the USPSTF found adequate evidence about the lack of harm from iron supplementation, it failed to find adequate evidence on the benefits of supplementation.

“Reported benefits of supplementation were limited to intermediate outcomes (maternal hematologic indexes), and evidence on the benefits of supplementation on maternal and infant health outcomes was inadequate because of inconsistent results and underpowered studies,” the USPSTF wrote.

The group found less research on the outcomes of screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic pregnant women and adolescents. “No good- or fair quality studies were found that evaluated the benefits or harms of screening in this population,” according to the recommendation.

The USPSTF concluded that the “current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women … [and] of routine iron supplementation for pregnant women to prevent adverse maternal health and birth outcomes.”

Read the full recommendation in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M15-1707).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force announced, in a recommendation on Sept. 7, that it is unsure whether pregnant women who are asymptomatic for iron deficiency anemia should be screened for this condition or take iron supplements.

The recommendation is an update to the 2006 USPSTF recommendation, which also expressed uncertainty on whether iron supplementation is beneficial to pregnant women.

“Both the 2006 and the current recommendation statements found insufficient evidence to determine the balance of the benefits and harms of iron supplementation during pregnancy,” Dr. Albert L. Siu wrote on behalf of members of the USPSTF.

The 2006 recommendation differed from the current one in that it had advocated for routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women.

“In its review of the evidence to update the 2006 recommendation, the USPSTF found no good- or fair-quality studies on the benefits or harms of screening that would be applicable to the current U.S. population of pregnant women,” according to the task force recommendation statement published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF based the updated recommendation on a systematic evidence review, which focused on whether pregnant women and adolescents’ use of oral iron supplementation or treatment was associated with changes in iron status and improvement in maternal and infant health outcomes. It reviewed “studies conducted in settings similar to the United States in rates of malnutrition, hemoparasite burden, and general socioeconomic status.”

The USPSTF’s review included 12 “good- or fair-quality randomized controlled trials,” which evaluated the effects of iron supplementation on various maternal hematologic indexes, including hemoglobin level, serum ferritin level, anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia.

Eight of the studies reported maternal hemoglobin levels at term or delivery, with six of the studies having reported a significantly higher mean hemoglobin level in the supplemented groups than in the control groups (122-139 g/L vs. 115-128 g/L, respectively). Seven studies reported serum ferritin levels at term or delivery, with five of these having reported a significantly higher ferritin level in the supplemented groups, compared with the control groups (12.0-30.0 mcg/L vs. 6.2-24.9 mcg/L, respectively).

“Although adequate evidence shows that [iron] supplementation increases hemoglobin and ferritin levels, the evidence is unclear on whether this increase leads to an improvement in maternal and fetal outcomes. In most of these studies, the supplemented groups had higher mean hemoglobin levels than the nonsupplemented groups; however, both groups reported values within normal limits,” the USPSTF wrote.

Research on the harmful effects of iron supplementation in pregnant women better addressed the USPSTF’s questions; 10 of the trials showed that the harms of iron supplementation during pregnancy were “small to none,” with most of the harms reported having been nausea, constipation, and diarrhea.

While the USPSTF found adequate evidence about the lack of harm from iron supplementation, it failed to find adequate evidence on the benefits of supplementation.

“Reported benefits of supplementation were limited to intermediate outcomes (maternal hematologic indexes), and evidence on the benefits of supplementation on maternal and infant health outcomes was inadequate because of inconsistent results and underpowered studies,” the USPSTF wrote.

The group found less research on the outcomes of screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic pregnant women and adolescents. “No good- or fair quality studies were found that evaluated the benefits or harms of screening in this population,” according to the recommendation.

The USPSTF concluded that the “current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women … [and] of routine iron supplementation for pregnant women to prevent adverse maternal health and birth outcomes.”

Read the full recommendation in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M15-1707).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force announced, in a recommendation on Sept. 7, that it is unsure whether pregnant women who are asymptomatic for iron deficiency anemia should be screened for this condition or take iron supplements.

The recommendation is an update to the 2006 USPSTF recommendation, which also expressed uncertainty on whether iron supplementation is beneficial to pregnant women.

“Both the 2006 and the current recommendation statements found insufficient evidence to determine the balance of the benefits and harms of iron supplementation during pregnancy,” Dr. Albert L. Siu wrote on behalf of members of the USPSTF.

The 2006 recommendation differed from the current one in that it had advocated for routine screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women.

“In its review of the evidence to update the 2006 recommendation, the USPSTF found no good- or fair-quality studies on the benefits or harms of screening that would be applicable to the current U.S. population of pregnant women,” according to the task force recommendation statement published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF based the updated recommendation on a systematic evidence review, which focused on whether pregnant women and adolescents’ use of oral iron supplementation or treatment was associated with changes in iron status and improvement in maternal and infant health outcomes. It reviewed “studies conducted in settings similar to the United States in rates of malnutrition, hemoparasite burden, and general socioeconomic status.”

The USPSTF’s review included 12 “good- or fair-quality randomized controlled trials,” which evaluated the effects of iron supplementation on various maternal hematologic indexes, including hemoglobin level, serum ferritin level, anemia, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia.

Eight of the studies reported maternal hemoglobin levels at term or delivery, with six of the studies having reported a significantly higher mean hemoglobin level in the supplemented groups than in the control groups (122-139 g/L vs. 115-128 g/L, respectively). Seven studies reported serum ferritin levels at term or delivery, with five of these having reported a significantly higher ferritin level in the supplemented groups, compared with the control groups (12.0-30.0 mcg/L vs. 6.2-24.9 mcg/L, respectively).

“Although adequate evidence shows that [iron] supplementation increases hemoglobin and ferritin levels, the evidence is unclear on whether this increase leads to an improvement in maternal and fetal outcomes. In most of these studies, the supplemented groups had higher mean hemoglobin levels than the nonsupplemented groups; however, both groups reported values within normal limits,” the USPSTF wrote.

Research on the harmful effects of iron supplementation in pregnant women better addressed the USPSTF’s questions; 10 of the trials showed that the harms of iron supplementation during pregnancy were “small to none,” with most of the harms reported having been nausea, constipation, and diarrhea.

While the USPSTF found adequate evidence about the lack of harm from iron supplementation, it failed to find adequate evidence on the benefits of supplementation.

“Reported benefits of supplementation were limited to intermediate outcomes (maternal hematologic indexes), and evidence on the benefits of supplementation on maternal and infant health outcomes was inadequate because of inconsistent results and underpowered studies,” the USPSTF wrote.

The group found less research on the outcomes of screening for iron deficiency anemia in asymptomatic pregnant women and adolescents. “No good- or fair quality studies were found that evaluated the benefits or harms of screening in this population,” according to the recommendation.

The USPSTF concluded that the “current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnant women … [and] of routine iron supplementation for pregnant women to prevent adverse maternal health and birth outcomes.”

Read the full recommendation in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M15-1707).

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

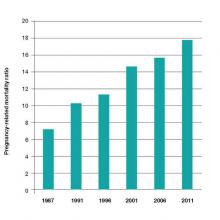

A mother’s untimely death in childbirth is a grave loss that sends shock waves of grief across generations of her family and community. As obstetricians practicing in the United States, we face a terrible problem. We have a continually rising rate of maternal death in a country with exceptional medical resources (FIGURE).1 Our national decentralized approach to dealing with maternal mortality is a factor contributing to the decades-long increase in the maternal mortality ratio. Let’s get organized to better respond to this public health crisis.

Medical education— Let’s get focused on maternal mortality

The 140-page Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology CREOG Educational Objectives: Core Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology provides a detailed enumeration of the key learning objectives for residents in obstetrics and gynecology.2 Surprisingly, the CREOG objectives do not mention reducing maternal mortality as an important curricular goal. Learning clinical processes and practices that decrease the risk of maternal mortality should be an important educational goal for all residents training in obstetrics and gynecology.

Nationwide action is needed to address the problem

Many countries have organized widespread efforts to reduce maternal mortality. In the United Kingdom and France there are nationwide reviews of maternal deaths with detailed analyses of clinical events and identification of areas for future improvement. These reviews result in the dissemination of countrywide clinical recommendations that change practice and hopefully reduce the risk of future maternal deaths. For example, following the identification of pulmonary embolism as a leading cause of maternal death in the United Kingdom there was a nationwide effort to increase the use of mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis to prevent deep venous thrombosis.

In the United States, experts have proposed that a national program of clinical review of severe maternal morbidity cases should be mandatory. (There are many more cases of “near misses” with severe maternal morbidity than there are maternal deaths.) The greater number of cases available for review should help institutions to quickly recognize potential areas for clinical improvement. One group of experts has recommended that all deliveries in which a pregnant woman received 4 or more units of blood or was admitted to an intensive care unit should be thoroughly reviewed to identify opportunities for clinical improvement.3

In the United Kingdom a contemporary clinical problem that is being addressed in an organized and systematic manner is how to respond to the rising rate of severe maternal morbidity caused by placenta accreta. Experts have concluded that women with a suspected placenta accreta should deliver in regional centers with advanced clinical resources—including an emergency surgical response team, interventional radiology, a high capacity blood bank, and an intensive care unit.

A similar approach has been proposed for managing placenta accreta in the United States.4 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have proposed a tiered system of obstetric care with more complex cases being referred to regional perinatal centers.5 Regionalization of trauma services has been an important part of the US health care system for decades. Cases of severe trauma are brought to regional centers equipped to emergently treat complex injuries. A similar system of regulation and regionalization could be adapted for optimizing maternity care.

High-risk clinical events: Is your unit prepared?

In the United States the leading causes of maternal mortality, in descending order, are6−8:

- cardiovascular diseases

- infection

- hemorrhage

- cardiomyopathy

- pulmonary embolism

- hypertension

- amniotic fluid embolism

- stroke

- anesthesia complications.

Over the last decade, the Joint Commission has recommended that birthing centers develop standardized protocols and use simulation to improve the institution’s ability to respond in a timely manner to clinical events that may result in maternal morbidity or death.

The quality of published protocols dealing with hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism is continuously improving, and every birthing center should have written protocols that are updated on a regular timetable for these common high-risk events.9,10 Does your birthing unit have written protocols to deal with cardiac diseases, infection, obstetric hemorrhage, thromboembolism, and severe hypertension? Are simulation exercises used to strengthen familiarity with the protocols?

High-risk patients

An amazing fact of today’s medical care is that sexually active women of reproductive age who have high-risk medical problems often have not been counseled to use a highly effective contraceptive, resulting in an increased risk of unintended pregnancy and maternal death. For example, adult women with a history of congenital heart disease are known to be at increased risk of death if they become pregnant. In a recent study, women with a history of congenital heart disease had 178 maternal deaths per 100,000 deliveries—a rate approximately 10-fold higher than the US maternal mortality ratio.11 Yet, many of these women are not using a highly effective contraceptive, and this results in a high rate of unplanned pregnancy.12

In order to reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy in women with high-risk medical problems, health systems could make contraception an important “vital sign” for women with high-risk medical conditions.

Race and age matter greatly when it comes to maternal mortality risk

There are major racial differences in pregnancy-related mortality, with black women having much higher rates than white women. In the United States in 2011, the pregnancy-related mortality ratio for white, black, and women of other races was 12.5, 42.8, and 17.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively. This represents a major racial disparity in pregnancy outcomes.1

The age of the mother is an important determinant of the risk of maternal death. Women younger than age 35 years have the lowest risk of maternal death. From 2006 to 2010, pregnant women older than age 40 had a risk of death approximately 3 times greater than women aged 34 or younger.2

References

- Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www .cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006-2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5−12.

Let’s get organized

In a country with a history of embracing the “live free or die” ethic, it is often difficult for physicians to enthusiastically embrace the need for a higher level of organization and a potential reduction in individual freedom in order to improve health outcomes. And with a US maternal mortality ratio of 1 maternal death for every 5,400 births, many obstetricians will never have one of their patients die in childbirth. In fact, most obstetricians will have only 1 maternal death during their entire career. In this reality, when clinical events occur rarely, it is not possible for any single clinician, working alone, to impact the overall outcomes of those rare events. Therefore, teamwork and national efforts, such as the National Partnership for Maternal Safety,13 will be necessary to reverse our alarming trend of increasing maternal mortality. Let’s get organized to stop the rise of maternal deaths in the United States.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Chescheir NC. Enough already! Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):2−4.

- Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology (CREOG) Educational Objectives: Core Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 10th ed. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013:140.

- Callaghan WM, Grobman WA, Kilpatrick SJ, Main EK, D’Alton M. Facility-based identification of women with severe maternal morbidity: it is time to start. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):978−981.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):561−568.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus No 2: levels of maternal care. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):502−515.

- Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998−2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1302−1309.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006−2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5−12.

- Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Shields LE, Wiesner S, Fulton J, Pelletreau B. Comprehensive maternal hemorrhage protocols reduce the use of blood products and improve patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):272−280.

- James A. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin No. 123: thromboembolism in pregnancy. ACOG. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):718−729.

- Thompson JL, Kuklina EV, Bateman BT, Callaghan WM, James AH, Grotegut CA. Medical and obstetrical outcomes among pregnant women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):346−354.

- Lindley KJ, Madden T, Cahill AG, Ludbrook PA, Billadello JJ. Contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):363−369.

- D’Alton ME, Main EK, Menard MK, Levy BS. The National Partnership for Maternal Safety. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):973−977.

A mother’s untimely death in childbirth is a grave loss that sends shock waves of grief across generations of her family and community. As obstetricians practicing in the United States, we face a terrible problem. We have a continually rising rate of maternal death in a country with exceptional medical resources (FIGURE).1 Our national decentralized approach to dealing with maternal mortality is a factor contributing to the decades-long increase in the maternal mortality ratio. Let’s get organized to better respond to this public health crisis.

Medical education— Let’s get focused on maternal mortality

The 140-page Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology CREOG Educational Objectives: Core Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology provides a detailed enumeration of the key learning objectives for residents in obstetrics and gynecology.2 Surprisingly, the CREOG objectives do not mention reducing maternal mortality as an important curricular goal. Learning clinical processes and practices that decrease the risk of maternal mortality should be an important educational goal for all residents training in obstetrics and gynecology.

Nationwide action is needed to address the problem

Many countries have organized widespread efforts to reduce maternal mortality. In the United Kingdom and France there are nationwide reviews of maternal deaths with detailed analyses of clinical events and identification of areas for future improvement. These reviews result in the dissemination of countrywide clinical recommendations that change practice and hopefully reduce the risk of future maternal deaths. For example, following the identification of pulmonary embolism as a leading cause of maternal death in the United Kingdom there was a nationwide effort to increase the use of mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis to prevent deep venous thrombosis.

In the United States, experts have proposed that a national program of clinical review of severe maternal morbidity cases should be mandatory. (There are many more cases of “near misses” with severe maternal morbidity than there are maternal deaths.) The greater number of cases available for review should help institutions to quickly recognize potential areas for clinical improvement. One group of experts has recommended that all deliveries in which a pregnant woman received 4 or more units of blood or was admitted to an intensive care unit should be thoroughly reviewed to identify opportunities for clinical improvement.3

In the United Kingdom a contemporary clinical problem that is being addressed in an organized and systematic manner is how to respond to the rising rate of severe maternal morbidity caused by placenta accreta. Experts have concluded that women with a suspected placenta accreta should deliver in regional centers with advanced clinical resources—including an emergency surgical response team, interventional radiology, a high capacity blood bank, and an intensive care unit.

A similar approach has been proposed for managing placenta accreta in the United States.4 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have proposed a tiered system of obstetric care with more complex cases being referred to regional perinatal centers.5 Regionalization of trauma services has been an important part of the US health care system for decades. Cases of severe trauma are brought to regional centers equipped to emergently treat complex injuries. A similar system of regulation and regionalization could be adapted for optimizing maternity care.

High-risk clinical events: Is your unit prepared?

In the United States the leading causes of maternal mortality, in descending order, are6−8:

- cardiovascular diseases

- infection

- hemorrhage

- cardiomyopathy

- pulmonary embolism

- hypertension

- amniotic fluid embolism

- stroke

- anesthesia complications.

Over the last decade, the Joint Commission has recommended that birthing centers develop standardized protocols and use simulation to improve the institution’s ability to respond in a timely manner to clinical events that may result in maternal morbidity or death.

The quality of published protocols dealing with hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism is continuously improving, and every birthing center should have written protocols that are updated on a regular timetable for these common high-risk events.9,10 Does your birthing unit have written protocols to deal with cardiac diseases, infection, obstetric hemorrhage, thromboembolism, and severe hypertension? Are simulation exercises used to strengthen familiarity with the protocols?

High-risk patients

An amazing fact of today’s medical care is that sexually active women of reproductive age who have high-risk medical problems often have not been counseled to use a highly effective contraceptive, resulting in an increased risk of unintended pregnancy and maternal death. For example, adult women with a history of congenital heart disease are known to be at increased risk of death if they become pregnant. In a recent study, women with a history of congenital heart disease had 178 maternal deaths per 100,000 deliveries—a rate approximately 10-fold higher than the US maternal mortality ratio.11 Yet, many of these women are not using a highly effective contraceptive, and this results in a high rate of unplanned pregnancy.12

In order to reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy in women with high-risk medical problems, health systems could make contraception an important “vital sign” for women with high-risk medical conditions.

Race and age matter greatly when it comes to maternal mortality risk

There are major racial differences in pregnancy-related mortality, with black women having much higher rates than white women. In the United States in 2011, the pregnancy-related mortality ratio for white, black, and women of other races was 12.5, 42.8, and 17.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively. This represents a major racial disparity in pregnancy outcomes.1

The age of the mother is an important determinant of the risk of maternal death. Women younger than age 35 years have the lowest risk of maternal death. From 2006 to 2010, pregnant women older than age 40 had a risk of death approximately 3 times greater than women aged 34 or younger.2

References

- Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www .cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006-2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5−12.

Let’s get organized

In a country with a history of embracing the “live free or die” ethic, it is often difficult for physicians to enthusiastically embrace the need for a higher level of organization and a potential reduction in individual freedom in order to improve health outcomes. And with a US maternal mortality ratio of 1 maternal death for every 5,400 births, many obstetricians will never have one of their patients die in childbirth. In fact, most obstetricians will have only 1 maternal death during their entire career. In this reality, when clinical events occur rarely, it is not possible for any single clinician, working alone, to impact the overall outcomes of those rare events. Therefore, teamwork and national efforts, such as the National Partnership for Maternal Safety,13 will be necessary to reverse our alarming trend of increasing maternal mortality. Let’s get organized to stop the rise of maternal deaths in the United States.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A mother’s untimely death in childbirth is a grave loss that sends shock waves of grief across generations of her family and community. As obstetricians practicing in the United States, we face a terrible problem. We have a continually rising rate of maternal death in a country with exceptional medical resources (FIGURE).1 Our national decentralized approach to dealing with maternal mortality is a factor contributing to the decades-long increase in the maternal mortality ratio. Let’s get organized to better respond to this public health crisis.

Medical education— Let’s get focused on maternal mortality

The 140-page Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology CREOG Educational Objectives: Core Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology provides a detailed enumeration of the key learning objectives for residents in obstetrics and gynecology.2 Surprisingly, the CREOG objectives do not mention reducing maternal mortality as an important curricular goal. Learning clinical processes and practices that decrease the risk of maternal mortality should be an important educational goal for all residents training in obstetrics and gynecology.

Nationwide action is needed to address the problem

Many countries have organized widespread efforts to reduce maternal mortality. In the United Kingdom and France there are nationwide reviews of maternal deaths with detailed analyses of clinical events and identification of areas for future improvement. These reviews result in the dissemination of countrywide clinical recommendations that change practice and hopefully reduce the risk of future maternal deaths. For example, following the identification of pulmonary embolism as a leading cause of maternal death in the United Kingdom there was a nationwide effort to increase the use of mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis to prevent deep venous thrombosis.

In the United States, experts have proposed that a national program of clinical review of severe maternal morbidity cases should be mandatory. (There are many more cases of “near misses” with severe maternal morbidity than there are maternal deaths.) The greater number of cases available for review should help institutions to quickly recognize potential areas for clinical improvement. One group of experts has recommended that all deliveries in which a pregnant woman received 4 or more units of blood or was admitted to an intensive care unit should be thoroughly reviewed to identify opportunities for clinical improvement.3

In the United Kingdom a contemporary clinical problem that is being addressed in an organized and systematic manner is how to respond to the rising rate of severe maternal morbidity caused by placenta accreta. Experts have concluded that women with a suspected placenta accreta should deliver in regional centers with advanced clinical resources—including an emergency surgical response team, interventional radiology, a high capacity blood bank, and an intensive care unit.

A similar approach has been proposed for managing placenta accreta in the United States.4 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have proposed a tiered system of obstetric care with more complex cases being referred to regional perinatal centers.5 Regionalization of trauma services has been an important part of the US health care system for decades. Cases of severe trauma are brought to regional centers equipped to emergently treat complex injuries. A similar system of regulation and regionalization could be adapted for optimizing maternity care.

High-risk clinical events: Is your unit prepared?

In the United States the leading causes of maternal mortality, in descending order, are6−8:

- cardiovascular diseases

- infection

- hemorrhage

- cardiomyopathy

- pulmonary embolism

- hypertension

- amniotic fluid embolism

- stroke

- anesthesia complications.

Over the last decade, the Joint Commission has recommended that birthing centers develop standardized protocols and use simulation to improve the institution’s ability to respond in a timely manner to clinical events that may result in maternal morbidity or death.

The quality of published protocols dealing with hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism is continuously improving, and every birthing center should have written protocols that are updated on a regular timetable for these common high-risk events.9,10 Does your birthing unit have written protocols to deal with cardiac diseases, infection, obstetric hemorrhage, thromboembolism, and severe hypertension? Are simulation exercises used to strengthen familiarity with the protocols?

High-risk patients

An amazing fact of today’s medical care is that sexually active women of reproductive age who have high-risk medical problems often have not been counseled to use a highly effective contraceptive, resulting in an increased risk of unintended pregnancy and maternal death. For example, adult women with a history of congenital heart disease are known to be at increased risk of death if they become pregnant. In a recent study, women with a history of congenital heart disease had 178 maternal deaths per 100,000 deliveries—a rate approximately 10-fold higher than the US maternal mortality ratio.11 Yet, many of these women are not using a highly effective contraceptive, and this results in a high rate of unplanned pregnancy.12

In order to reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy in women with high-risk medical problems, health systems could make contraception an important “vital sign” for women with high-risk medical conditions.

Race and age matter greatly when it comes to maternal mortality risk

There are major racial differences in pregnancy-related mortality, with black women having much higher rates than white women. In the United States in 2011, the pregnancy-related mortality ratio for white, black, and women of other races was 12.5, 42.8, and 17.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively. This represents a major racial disparity in pregnancy outcomes.1

The age of the mother is an important determinant of the risk of maternal death. Women younger than age 35 years have the lowest risk of maternal death. From 2006 to 2010, pregnant women older than age 40 had a risk of death approximately 3 times greater than women aged 34 or younger.2

References

- Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www .cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006-2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5−12.

Let’s get organized

In a country with a history of embracing the “live free or die” ethic, it is often difficult for physicians to enthusiastically embrace the need for a higher level of organization and a potential reduction in individual freedom in order to improve health outcomes. And with a US maternal mortality ratio of 1 maternal death for every 5,400 births, many obstetricians will never have one of their patients die in childbirth. In fact, most obstetricians will have only 1 maternal death during their entire career. In this reality, when clinical events occur rarely, it is not possible for any single clinician, working alone, to impact the overall outcomes of those rare events. Therefore, teamwork and national efforts, such as the National Partnership for Maternal Safety,13 will be necessary to reverse our alarming trend of increasing maternal mortality. Let’s get organized to stop the rise of maternal deaths in the United States.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Chescheir NC. Enough already! Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):2−4.

- Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology (CREOG) Educational Objectives: Core Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 10th ed. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013:140.

- Callaghan WM, Grobman WA, Kilpatrick SJ, Main EK, D’Alton M. Facility-based identification of women with severe maternal morbidity: it is time to start. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):978−981.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):561−568.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus No 2: levels of maternal care. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):502−515.

- Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998−2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1302−1309.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006−2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5−12.

- Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Shields LE, Wiesner S, Fulton J, Pelletreau B. Comprehensive maternal hemorrhage protocols reduce the use of blood products and improve patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):272−280.

- James A. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin No. 123: thromboembolism in pregnancy. ACOG. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):718−729.

- Thompson JL, Kuklina EV, Bateman BT, Callaghan WM, James AH, Grotegut CA. Medical and obstetrical outcomes among pregnant women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):346−354.

- Lindley KJ, Madden T, Cahill AG, Ludbrook PA, Billadello JJ. Contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):363−369.

- D’Alton ME, Main EK, Menard MK, Levy BS. The National Partnership for Maternal Safety. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):973−977.

- Chescheir NC. Enough already! Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):2−4.

- Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology (CREOG) Educational Objectives: Core Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 10th ed. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013:140.

- Callaghan WM, Grobman WA, Kilpatrick SJ, Main EK, D’Alton M. Facility-based identification of women with severe maternal morbidity: it is time to start. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):978−981.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):561−568.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus No 2: levels of maternal care. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):502−515.

- Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998−2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1302−1309.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006−2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5−12.

- Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Shields LE, Wiesner S, Fulton J, Pelletreau B. Comprehensive maternal hemorrhage protocols reduce the use of blood products and improve patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):272−280.

- James A. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin No. 123: thromboembolism in pregnancy. ACOG. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):718−729.

- Thompson JL, Kuklina EV, Bateman BT, Callaghan WM, James AH, Grotegut CA. Medical and obstetrical outcomes among pregnant women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):346−354.

- Lindley KJ, Madden T, Cahill AG, Ludbrook PA, Billadello JJ. Contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):363−369.

- D’Alton ME, Main EK, Menard MK, Levy BS. The National Partnership for Maternal Safety. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):973−977.

Balance Caution With Necessity When Prescribing Dermatology Drugs in Pregnancy

NEW YORK – Disease exacerbations during pregnancy can be more dangerous for the fetus than some of the medications used to treat them..

No one wants to take unnecessary drugs during pregnancy, Dr. Jenny Murase said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. But concern about medication safety should never override the need to treat new-onset disease or control existing disorders.

“Often, patients are so worried about the effects of medicines on the baby that they don’t think about the effects of the disease. This is a thing we need to address with each patient. What would happen to you, and your baby, if this disease is not treated?” said Dr. Murase of the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, San Francisco.

Primary herpes simplex infections are an excellent example of this dilemma, she said. “Primary HSV has up to a 50% transmission rate to the fetus. In utero infections are associated with microcephaly, hydrocephalus, and chorioretinitis. About a third of neonates have central nervous system disease, and a quarter are born with disseminated disease,” and the neonatal mortality rate is nearly 70%.

“On the other hand, acyclovir is very, very safe,” based on data on thousands of patients, Dr. Murase said. Famciclovir and valacyclovir are also likely safe but data on those drugs are more limited, she added.

Sometimes, ideas about a drug’s safety during pregnancy are based on old or confusing studies. The worries about the teratogenicity of systemic steroids, for example, stem from a 1951 report that cortisone caused orofacial cleft in prenatally exposed mice.

“Since then, no prospective studies have found any evidence of congenital malformations associated with systemic steroids,” Dr. Murase said. However, “epidemiologic studies have suggested a threefold increase, which, interestingly, is in line with the mouse findings.”

The drugs do, however, have an important place in the armamentarium; they should be used judiciously and as part of a careful risk-benefit analysis. Both betamethasone and dexamethasone pass the placental barrier well; prednisone is not as transferable.

Dr. Murase provided a list of some medications commonly employed in dermatologic practice, with considerations for their use during pregnancy.

• Topical steroids. A 2013 study found that pregnancy-long exposure to more than 300 g of a potent or superpotent topical corticosteroid did not increase risk of orofacial cleft in the newborn, but did increase risk of low birth weight. “So if you are giving more than five tubes of 60 g, there is a potential for low birth weight – although this could also be related to the actual severity of the disease. Still, you should discuss this risk with your patient.”

• Antihistamines. These should be avoided in the last month of pregnancy as they can stimulate uterine contractions, especially if they are given intravenously or in very high doses. There have been reports of a doubling of retinopathy in premature infants (22% vs. 11%) associated with antihistamines used within 2 weeks of delivery. Some infants can have withdrawal symptoms, including seizure, if the mother has been taking high doses of the drugs.

• Antibiotics. The first-line antibiotics are penicillin, cephalosporins, and dicloxacillin; all are safe. Of the macrolides, erythromycin is preferred. However, the estolate form of the drug has been associated with reversible abnormalities in liver enzymes; the base and ethylsuccinate forms don’t have this risk. Rifampin may be used, but vitamin K should be given with it. Sulfonamides are a second-line choice up until the third trimester. They shouldn’t be used after that, as they can cause anemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and kernicterus. Tetracycline can be used up to 14 weeks’ gestation but not after that, because of the risks of bone growth inhibition and tooth discoloration in the infant, and maternal hepatitis.

• Antifungals. Topical antifungals are not too concerning. Nystatin is safe, but not as effective as the later-generation medications. Clotrimazole is the first choice, followed by miconazole and ketoconazole. Data are limited, but topical terbinafine, naftifine, and ciclopirox are also probably safe, she said.

Systemic antifungals are a different matter. None of the imidazole derivatives are advised during pregnancy, as they have been associated with craniosynostosis, congenital heart defects, and skeletal anomalies. If they are used, a diagnostic ultrasound at 20 weeks is advisable.

• Light. Light therapy is generally considered safe, although there is some evidence that narrow-band ultraviolet can deplete folic acid levels. Despite that, there are no reports of neural tube or orofacial defects associated with light therapy. Nevertheless, make sure patients are supplementing with folic acid if they receive light therapy.

Light therapy should never be combined with oxsoralen in pregnant women; the drug is a known mutagen. Data on cyclosporine are more limited, but it’s a category C drug in pregnancy, so it’s best to avoid it.

• Biologics. Etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and alefacept are all category B drugs in pregnancy. There are some hints that they, as well as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitors, may be associated with some fetal anomalies in the VACTERL association cluster (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities). A confirmation of the syndrome requires three signs to be present. Only two infants born to mothers taking a biologic have had three qualifying signs.

However, pregnancy outcome reports for the drugs have recorded malformations. Among the adalimumab cohorts totaling 256 pregnancies, there were 14 fetal anomalies (5.5%); of these, nine were VACTERL-related. In the etanercept cohorts totaling 204 pregnancies, there were 13 anomalies (6.4%); of these, six were VACTERL-related. In the infliximab cohorts totaling 112 pregnancies, there was only one anomaly, which was in the VACTERL cluster. Among the 407 pregnancies in the TNF-inhibitors, there were three anomalies, none of which were related to VACTERL.

Dr. Murase had no financial disclosures relevant to her talk.

The current system of using letter categories to denote risk of prescription drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding is being replaced by the Food and Drug Administration, with the addition of subsections in drug labeling.

NEW YORK – Disease exacerbations during pregnancy can be more dangerous for the fetus than some of the medications used to treat them..

No one wants to take unnecessary drugs during pregnancy, Dr. Jenny Murase said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. But concern about medication safety should never override the need to treat new-onset disease or control existing disorders.

“Often, patients are so worried about the effects of medicines on the baby that they don’t think about the effects of the disease. This is a thing we need to address with each patient. What would happen to you, and your baby, if this disease is not treated?” said Dr. Murase of the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, San Francisco.

Primary herpes simplex infections are an excellent example of this dilemma, she said. “Primary HSV has up to a 50% transmission rate to the fetus. In utero infections are associated with microcephaly, hydrocephalus, and chorioretinitis. About a third of neonates have central nervous system disease, and a quarter are born with disseminated disease,” and the neonatal mortality rate is nearly 70%.

“On the other hand, acyclovir is very, very safe,” based on data on thousands of patients, Dr. Murase said. Famciclovir and valacyclovir are also likely safe but data on those drugs are more limited, she added.

Sometimes, ideas about a drug’s safety during pregnancy are based on old or confusing studies. The worries about the teratogenicity of systemic steroids, for example, stem from a 1951 report that cortisone caused orofacial cleft in prenatally exposed mice.

“Since then, no prospective studies have found any evidence of congenital malformations associated with systemic steroids,” Dr. Murase said. However, “epidemiologic studies have suggested a threefold increase, which, interestingly, is in line with the mouse findings.”

The drugs do, however, have an important place in the armamentarium; they should be used judiciously and as part of a careful risk-benefit analysis. Both betamethasone and dexamethasone pass the placental barrier well; prednisone is not as transferable.

Dr. Murase provided a list of some medications commonly employed in dermatologic practice, with considerations for their use during pregnancy.

• Topical steroids. A 2013 study found that pregnancy-long exposure to more than 300 g of a potent or superpotent topical corticosteroid did not increase risk of orofacial cleft in the newborn, but did increase risk of low birth weight. “So if you are giving more than five tubes of 60 g, there is a potential for low birth weight – although this could also be related to the actual severity of the disease. Still, you should discuss this risk with your patient.”

• Antihistamines. These should be avoided in the last month of pregnancy as they can stimulate uterine contractions, especially if they are given intravenously or in very high doses. There have been reports of a doubling of retinopathy in premature infants (22% vs. 11%) associated with antihistamines used within 2 weeks of delivery. Some infants can have withdrawal symptoms, including seizure, if the mother has been taking high doses of the drugs.

• Antibiotics. The first-line antibiotics are penicillin, cephalosporins, and dicloxacillin; all are safe. Of the macrolides, erythromycin is preferred. However, the estolate form of the drug has been associated with reversible abnormalities in liver enzymes; the base and ethylsuccinate forms don’t have this risk. Rifampin may be used, but vitamin K should be given with it. Sulfonamides are a second-line choice up until the third trimester. They shouldn’t be used after that, as they can cause anemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and kernicterus. Tetracycline can be used up to 14 weeks’ gestation but not after that, because of the risks of bone growth inhibition and tooth discoloration in the infant, and maternal hepatitis.

• Antifungals. Topical antifungals are not too concerning. Nystatin is safe, but not as effective as the later-generation medications. Clotrimazole is the first choice, followed by miconazole and ketoconazole. Data are limited, but topical terbinafine, naftifine, and ciclopirox are also probably safe, she said.

Systemic antifungals are a different matter. None of the imidazole derivatives are advised during pregnancy, as they have been associated with craniosynostosis, congenital heart defects, and skeletal anomalies. If they are used, a diagnostic ultrasound at 20 weeks is advisable.

• Light. Light therapy is generally considered safe, although there is some evidence that narrow-band ultraviolet can deplete folic acid levels. Despite that, there are no reports of neural tube or orofacial defects associated with light therapy. Nevertheless, make sure patients are supplementing with folic acid if they receive light therapy.

Light therapy should never be combined with oxsoralen in pregnant women; the drug is a known mutagen. Data on cyclosporine are more limited, but it’s a category C drug in pregnancy, so it’s best to avoid it.

• Biologics. Etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and alefacept are all category B drugs in pregnancy. There are some hints that they, as well as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitors, may be associated with some fetal anomalies in the VACTERL association cluster (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities). A confirmation of the syndrome requires three signs to be present. Only two infants born to mothers taking a biologic have had three qualifying signs.

However, pregnancy outcome reports for the drugs have recorded malformations. Among the adalimumab cohorts totaling 256 pregnancies, there were 14 fetal anomalies (5.5%); of these, nine were VACTERL-related. In the etanercept cohorts totaling 204 pregnancies, there were 13 anomalies (6.4%); of these, six were VACTERL-related. In the infliximab cohorts totaling 112 pregnancies, there was only one anomaly, which was in the VACTERL cluster. Among the 407 pregnancies in the TNF-inhibitors, there were three anomalies, none of which were related to VACTERL.

Dr. Murase had no financial disclosures relevant to her talk.

The current system of using letter categories to denote risk of prescription drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding is being replaced by the Food and Drug Administration, with the addition of subsections in drug labeling.

NEW YORK – Disease exacerbations during pregnancy can be more dangerous for the fetus than some of the medications used to treat them..

No one wants to take unnecessary drugs during pregnancy, Dr. Jenny Murase said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. But concern about medication safety should never override the need to treat new-onset disease or control existing disorders.

“Often, patients are so worried about the effects of medicines on the baby that they don’t think about the effects of the disease. This is a thing we need to address with each patient. What would happen to you, and your baby, if this disease is not treated?” said Dr. Murase of the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, San Francisco.