User login

Opportunities and limits in universal screening for perinatal depression

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Obstetric Practice recently published a revised opinion on screening for perinatal depression, recommending that “clinicians screen patients at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms using a standard, validated tool.” The statement adds that “women with current depression or anxiety, a history of perinatal mood disorders, or risk factors for perinatal mood disorders warrant particularly close monitoring, evaluation, and assessment.” A list of validated depression screening tools is included (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:1268-71). In previous iterations, the committee had not recommended formal screening for perinatal depression (referred to as major or minor depressive episodes occurring during pregnancy or during the first 12 months after delivery) and left the utility of screening as an open question to the field.

Noting that screening alone cannot improve clinical outcomes, the ACOG opinion says that it “must be coupled with appropriate follow-up and treatment when indicated,” and – most critically – adds that clinical staff in the practice “should be prepared to initiate medical therapy, refer patients to appropriate health resources when indicated, or both.” The latter recommendation is followed by the statement that “systems should be in place to ensure follow-up for diagnosis and treatment.”

Many states have initiated programs for screening for perinatal depression, which is intuitive given the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in women of reproductive age. Unfortunately, to date, there are no data indicating whether screening results in improved outcomes, or what type of treatment women receive as a result of screening; the ACOG opinion notes that definitive evidence on the benefit of screening is “limited.”

In prevalence studies, maternal morbidity associated with untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders clearly exceeds the morbidity associated with hemorrhage and pregnancy-induced hypertension, with significant effects on families and children as well. Therefore, even in the absence of an evidence base, there is support for routine screening and for ob.gyns. to initiate treatment and to facilitate referrals to appropriate settings.

In Massachusetts, where I practice, screening is not mandatory but is becoming increasingly popular, and resources to manage those with positive screening results are being developed.

The MCPAP (Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project) for Moms was established to enhance screening for perinatal depression and to provide screening and educational tools, as well as free telephone backup, consultation, and referral service for ob.gyn. practices. MCPAP for Moms is coupled with an extensive community-based perinatal mood and anxiety service network: mental health providers, including social workers; specialized nurses with expertise in perinatal mental health; and support groups for women suffering from perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. The program is new and has promise, although evidence supporting its effectiveness is not yet available.

Some argue that screening and treatment of perinatal depression by nonpsychiatric providers opens up a “Pandora’s box.” But should the box be opened nonetheless?

Obvious problems might include many women with positive screening results not being referred for appropriate treatment or, if referred, receiving incomplete treatment – all very valid concerns. But one could also argue that with a highly prevalent illness that presents during a discrete period of time, the opportunity to screen in the obstetric setting (or in the pediatric setting, a separate topic) is an opportunity to at least help mitigate some of the suffering associated with perinatal depression.

The clinician in the community who will screen these women will need to manage the substantial responsibility of initiating treatment for patients with perinatal depression or referring them for management. The main question following diagnosis of perinatal depression is really not necessarily how “best” to treat a patient with perinatal depression. An evidence base exists supporting efficacy for treatments, including medication and certain psychotherapies. Perhaps the greatest pitfall inherent in an opinion like the one from ACOG relates to the incomplete infrastructure and associated resources in many parts of the country – and in our health care system – needed to accommodate and effectively manage the increasing number of women who will be diagnosed with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders as a consequence of more widespread screening.

Whether community-based ob.gyns. will be comfortable with direct treatment of perinatal psychiatric illness or the extent to which they view this as part of their clinical responsibility remains to be seen. It is possible that they will follow suit, just as primary care physicians became increasingly comfortable prescribing antidepressants in the early 1990s as easy and safe antidepressant treatments became available, particularly for patients with relatively straightforward major depression.

This committee opinion is an incremental advance, compared with previous opinions, and most critically, puts the conversation back on the national scene at an important time, as population health management is becoming an increasingly proximate reality.

The opinion leaves many unanswered questions regarding implementation on a national level, which may be beyond the scope of the committee’s task. But the recommendations, if carried out, will increase the likelihood of mitigating at least some of the substantial suffering associated with a highly prevalent illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected].

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Obstetric Practice recently published a revised opinion on screening for perinatal depression, recommending that “clinicians screen patients at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms using a standard, validated tool.” The statement adds that “women with current depression or anxiety, a history of perinatal mood disorders, or risk factors for perinatal mood disorders warrant particularly close monitoring, evaluation, and assessment.” A list of validated depression screening tools is included (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:1268-71). In previous iterations, the committee had not recommended formal screening for perinatal depression (referred to as major or minor depressive episodes occurring during pregnancy or during the first 12 months after delivery) and left the utility of screening as an open question to the field.

Noting that screening alone cannot improve clinical outcomes, the ACOG opinion says that it “must be coupled with appropriate follow-up and treatment when indicated,” and – most critically – adds that clinical staff in the practice “should be prepared to initiate medical therapy, refer patients to appropriate health resources when indicated, or both.” The latter recommendation is followed by the statement that “systems should be in place to ensure follow-up for diagnosis and treatment.”

Many states have initiated programs for screening for perinatal depression, which is intuitive given the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in women of reproductive age. Unfortunately, to date, there are no data indicating whether screening results in improved outcomes, or what type of treatment women receive as a result of screening; the ACOG opinion notes that definitive evidence on the benefit of screening is “limited.”

In prevalence studies, maternal morbidity associated with untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders clearly exceeds the morbidity associated with hemorrhage and pregnancy-induced hypertension, with significant effects on families and children as well. Therefore, even in the absence of an evidence base, there is support for routine screening and for ob.gyns. to initiate treatment and to facilitate referrals to appropriate settings.

In Massachusetts, where I practice, screening is not mandatory but is becoming increasingly popular, and resources to manage those with positive screening results are being developed.

The MCPAP (Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project) for Moms was established to enhance screening for perinatal depression and to provide screening and educational tools, as well as free telephone backup, consultation, and referral service for ob.gyn. practices. MCPAP for Moms is coupled with an extensive community-based perinatal mood and anxiety service network: mental health providers, including social workers; specialized nurses with expertise in perinatal mental health; and support groups for women suffering from perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. The program is new and has promise, although evidence supporting its effectiveness is not yet available.

Some argue that screening and treatment of perinatal depression by nonpsychiatric providers opens up a “Pandora’s box.” But should the box be opened nonetheless?

Obvious problems might include many women with positive screening results not being referred for appropriate treatment or, if referred, receiving incomplete treatment – all very valid concerns. But one could also argue that with a highly prevalent illness that presents during a discrete period of time, the opportunity to screen in the obstetric setting (or in the pediatric setting, a separate topic) is an opportunity to at least help mitigate some of the suffering associated with perinatal depression.

The clinician in the community who will screen these women will need to manage the substantial responsibility of initiating treatment for patients with perinatal depression or referring them for management. The main question following diagnosis of perinatal depression is really not necessarily how “best” to treat a patient with perinatal depression. An evidence base exists supporting efficacy for treatments, including medication and certain psychotherapies. Perhaps the greatest pitfall inherent in an opinion like the one from ACOG relates to the incomplete infrastructure and associated resources in many parts of the country – and in our health care system – needed to accommodate and effectively manage the increasing number of women who will be diagnosed with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders as a consequence of more widespread screening.

Whether community-based ob.gyns. will be comfortable with direct treatment of perinatal psychiatric illness or the extent to which they view this as part of their clinical responsibility remains to be seen. It is possible that they will follow suit, just as primary care physicians became increasingly comfortable prescribing antidepressants in the early 1990s as easy and safe antidepressant treatments became available, particularly for patients with relatively straightforward major depression.

This committee opinion is an incremental advance, compared with previous opinions, and most critically, puts the conversation back on the national scene at an important time, as population health management is becoming an increasingly proximate reality.

The opinion leaves many unanswered questions regarding implementation on a national level, which may be beyond the scope of the committee’s task. But the recommendations, if carried out, will increase the likelihood of mitigating at least some of the substantial suffering associated with a highly prevalent illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected].

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Obstetric Practice recently published a revised opinion on screening for perinatal depression, recommending that “clinicians screen patients at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms using a standard, validated tool.” The statement adds that “women with current depression or anxiety, a history of perinatal mood disorders, or risk factors for perinatal mood disorders warrant particularly close monitoring, evaluation, and assessment.” A list of validated depression screening tools is included (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:1268-71). In previous iterations, the committee had not recommended formal screening for perinatal depression (referred to as major or minor depressive episodes occurring during pregnancy or during the first 12 months after delivery) and left the utility of screening as an open question to the field.

Noting that screening alone cannot improve clinical outcomes, the ACOG opinion says that it “must be coupled with appropriate follow-up and treatment when indicated,” and – most critically – adds that clinical staff in the practice “should be prepared to initiate medical therapy, refer patients to appropriate health resources when indicated, or both.” The latter recommendation is followed by the statement that “systems should be in place to ensure follow-up for diagnosis and treatment.”

Many states have initiated programs for screening for perinatal depression, which is intuitive given the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in women of reproductive age. Unfortunately, to date, there are no data indicating whether screening results in improved outcomes, or what type of treatment women receive as a result of screening; the ACOG opinion notes that definitive evidence on the benefit of screening is “limited.”

In prevalence studies, maternal morbidity associated with untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders clearly exceeds the morbidity associated with hemorrhage and pregnancy-induced hypertension, with significant effects on families and children as well. Therefore, even in the absence of an evidence base, there is support for routine screening and for ob.gyns. to initiate treatment and to facilitate referrals to appropriate settings.

In Massachusetts, where I practice, screening is not mandatory but is becoming increasingly popular, and resources to manage those with positive screening results are being developed.

The MCPAP (Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project) for Moms was established to enhance screening for perinatal depression and to provide screening and educational tools, as well as free telephone backup, consultation, and referral service for ob.gyn. practices. MCPAP for Moms is coupled with an extensive community-based perinatal mood and anxiety service network: mental health providers, including social workers; specialized nurses with expertise in perinatal mental health; and support groups for women suffering from perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. The program is new and has promise, although evidence supporting its effectiveness is not yet available.

Some argue that screening and treatment of perinatal depression by nonpsychiatric providers opens up a “Pandora’s box.” But should the box be opened nonetheless?

Obvious problems might include many women with positive screening results not being referred for appropriate treatment or, if referred, receiving incomplete treatment – all very valid concerns. But one could also argue that with a highly prevalent illness that presents during a discrete period of time, the opportunity to screen in the obstetric setting (or in the pediatric setting, a separate topic) is an opportunity to at least help mitigate some of the suffering associated with perinatal depression.

The clinician in the community who will screen these women will need to manage the substantial responsibility of initiating treatment for patients with perinatal depression or referring them for management. The main question following diagnosis of perinatal depression is really not necessarily how “best” to treat a patient with perinatal depression. An evidence base exists supporting efficacy for treatments, including medication and certain psychotherapies. Perhaps the greatest pitfall inherent in an opinion like the one from ACOG relates to the incomplete infrastructure and associated resources in many parts of the country – and in our health care system – needed to accommodate and effectively manage the increasing number of women who will be diagnosed with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders as a consequence of more widespread screening.

Whether community-based ob.gyns. will be comfortable with direct treatment of perinatal psychiatric illness or the extent to which they view this as part of their clinical responsibility remains to be seen. It is possible that they will follow suit, just as primary care physicians became increasingly comfortable prescribing antidepressants in the early 1990s as easy and safe antidepressant treatments became available, particularly for patients with relatively straightforward major depression.

This committee opinion is an incremental advance, compared with previous opinions, and most critically, puts the conversation back on the national scene at an important time, as population health management is becoming an increasingly proximate reality.

The opinion leaves many unanswered questions regarding implementation on a national level, which may be beyond the scope of the committee’s task. But the recommendations, if carried out, will increase the likelihood of mitigating at least some of the substantial suffering associated with a highly prevalent illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected].

Q&A with the FDA: Implementing the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule

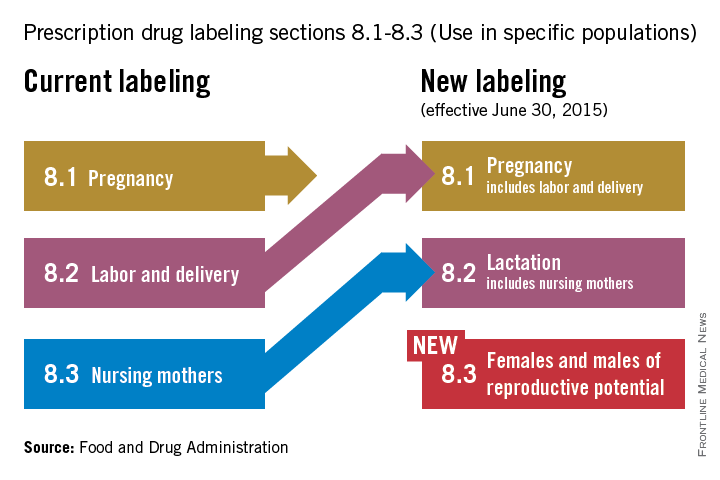

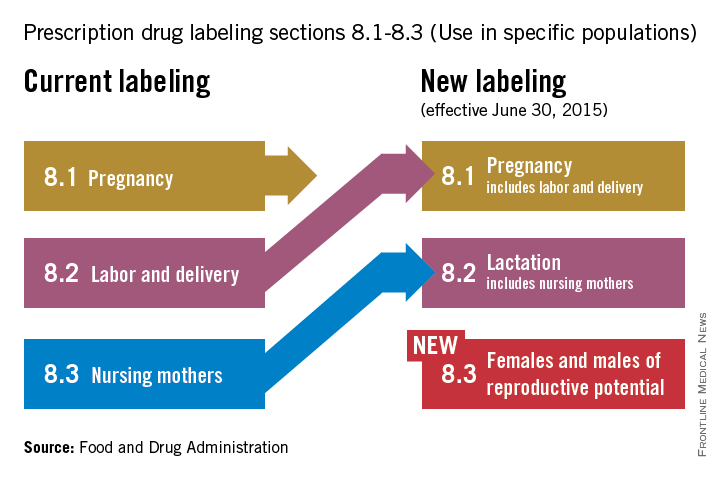

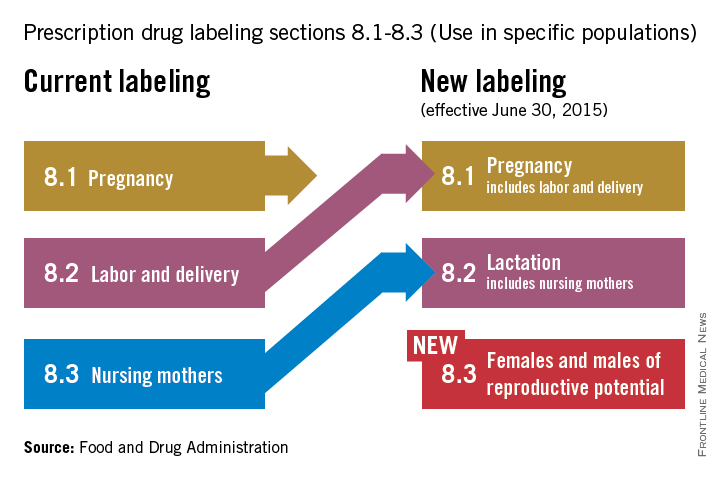

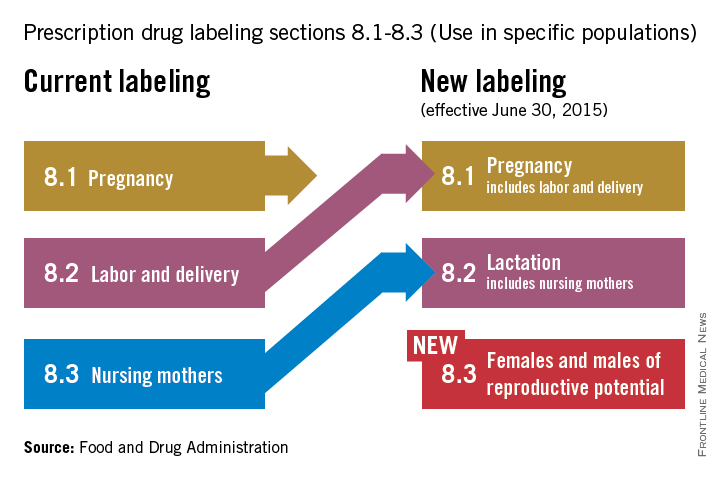

On June 30, pharmaceutical and biological manufacturers will begin implementing the Food and Drug Administration’s revised rules for pregnancy and lactation drug labeling. The Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) amends the Physician Labeling Rule (PLR, issued in 2006) and new labels aimed at providing clearer and more accurate information on drug risks will gradually roll out over the next 5 years.

The new rule – several years in the making – replaces pregnancy categories A, B, C, D, and X with short, integrated summaries that provide physicians with more information for discussing with patients the risks and benefits of a medication. The summaries will be brief and easy to read, and will contain evidence-based information that specifically addresses drug risks for women during pregnancy and lactation, as well as for men and women of reproductive potential. Under the PLLR, the pregnancy subsection of the risk summary will include for the first time information for any drug that has a pregnancy exposure registry.

Dr. John Whyte, director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagment (PASE) at the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, answers questions about the new rule from Ob.Gyn. News journalists and our Drugs, Pregnancy & Lactation columnists.

Question: Instead of the traditional letter categories, prescribers will now have to read the pregnancy and lactation subsections of the labeling. What can the agency do to ensure prescribers are reading all of the new contextual information in the drug label?

Answer: The agency has initiated outreach efforts to help prescribers become familiar with the new information in labeling. The most important information is now under a new heading called Risk Summary. This narrative summary replaces the pregnancy letter categories with a summary of information that is known about a product. The new labeling rule explains, based on available information, the potential benefits and risks for the mother, the fetus, and the breastfeeding child. The decision to replace the pregnancy letter categories with the summary paragraph was reached after extensive consultation with experts and stakeholders who were concerned that the traditional letter categories were overly simplistic.

Q: PLLR praises the value of pregnancy exposure registries and mandates that if a registry exists for an approved product, then the label must include the registry’s website address. There is no requirement, however, that industry actually fund these registries. Why did the agency stop short of requiring companies to provide ongoing support for pregnancy exposure registries?

A: FDA has the authority to require the establishment of pregnancy registries when there is a safety concern that would benefit from the collection of data in a postapproval study, or when a particular product will be used by a large number of females of reproductive age. However, FDA does not have the authority to require companies to fund existing pregnancy exposure registries.

Q: How does the FDA plan to review all of the summary statements of available data regarding reproductive safety considering the breadth of drugs in various therapeutic areas that will need to be reviewed?

A: All labeling changes, including the changes required by the PLLR, must be submitted to the FDA for review and approval. Changes to the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of labeling have been integrated into standard labeling review processes. In addition, the Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health, in the Office of New Drugs, works with the primary review divisions to help coordinate PLLR review processes.

Q: Are the manufacturers of generic drugs expected to “piggyback” the label for a branded molecule with respect to the pregnancy label?

A: Generic drug products (Abbreviated New Drug Applications) are required by regulation to have the “same” labeling as the reference drug listed. When the labeling is revised for the referenced drug, generic drug manufacturers also are required to update their labeling.

Q: In the new system, how will labeling stay up to date when important new data are published on a drug sometimes two to three times a year?

A: When new information becomes available that causes the labeling to be inaccurate, false, or misleading, drug manufacturers are required by regulation to update labeling.

Q: The rule is phased in over time. Drugs already on the market are given more time to switch to the new system. How long will physicians need to deal simultaneously with the old and the new formats?

A: There have been two labeling formats in use for some time as products approved prior to 2001 are not required to conform to either PLLR or PLR. The agency encourages manufacturers to voluntarily convert labeling of older products into PLR format. However, products approved prior to 2001 will be required to remove the pregnancy letter category by June 30, 2018, (3 years after the implementation of the PLLR).

Q: Does the FDA have any plans to address labeling for over-the-counter products in terms of their impact on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential?

A: The PLLR does not apply to over-the-counter products. However, the agency is continually reviewing the safety of products used over the counter, including impacts on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential.

Q: How does the FDA plan to assess over time the usefulness of the new labeling for prescribers and patients and make revisions?

A: The draft guidance was issued concurrently with PLLR. Based on the comments received from the public on the draft, as well as learning from the initial revisions of labeling, the guidance will be revised as needed. Guidance statements issued by FDA are regularly reviewed and revised as needed.

Dr. Whyte, a board-certified internist, is the director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagement at the FDA. Do you have other questions about the PLLR? Send them to [email protected].

On June 30, pharmaceutical and biological manufacturers will begin implementing the Food and Drug Administration’s revised rules for pregnancy and lactation drug labeling. The Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) amends the Physician Labeling Rule (PLR, issued in 2006) and new labels aimed at providing clearer and more accurate information on drug risks will gradually roll out over the next 5 years.

The new rule – several years in the making – replaces pregnancy categories A, B, C, D, and X with short, integrated summaries that provide physicians with more information for discussing with patients the risks and benefits of a medication. The summaries will be brief and easy to read, and will contain evidence-based information that specifically addresses drug risks for women during pregnancy and lactation, as well as for men and women of reproductive potential. Under the PLLR, the pregnancy subsection of the risk summary will include for the first time information for any drug that has a pregnancy exposure registry.

Dr. John Whyte, director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagment (PASE) at the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, answers questions about the new rule from Ob.Gyn. News journalists and our Drugs, Pregnancy & Lactation columnists.

Question: Instead of the traditional letter categories, prescribers will now have to read the pregnancy and lactation subsections of the labeling. What can the agency do to ensure prescribers are reading all of the new contextual information in the drug label?

Answer: The agency has initiated outreach efforts to help prescribers become familiar with the new information in labeling. The most important information is now under a new heading called Risk Summary. This narrative summary replaces the pregnancy letter categories with a summary of information that is known about a product. The new labeling rule explains, based on available information, the potential benefits and risks for the mother, the fetus, and the breastfeeding child. The decision to replace the pregnancy letter categories with the summary paragraph was reached after extensive consultation with experts and stakeholders who were concerned that the traditional letter categories were overly simplistic.

Q: PLLR praises the value of pregnancy exposure registries and mandates that if a registry exists for an approved product, then the label must include the registry’s website address. There is no requirement, however, that industry actually fund these registries. Why did the agency stop short of requiring companies to provide ongoing support for pregnancy exposure registries?

A: FDA has the authority to require the establishment of pregnancy registries when there is a safety concern that would benefit from the collection of data in a postapproval study, or when a particular product will be used by a large number of females of reproductive age. However, FDA does not have the authority to require companies to fund existing pregnancy exposure registries.

Q: How does the FDA plan to review all of the summary statements of available data regarding reproductive safety considering the breadth of drugs in various therapeutic areas that will need to be reviewed?

A: All labeling changes, including the changes required by the PLLR, must be submitted to the FDA for review and approval. Changes to the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of labeling have been integrated into standard labeling review processes. In addition, the Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health, in the Office of New Drugs, works with the primary review divisions to help coordinate PLLR review processes.

Q: Are the manufacturers of generic drugs expected to “piggyback” the label for a branded molecule with respect to the pregnancy label?

A: Generic drug products (Abbreviated New Drug Applications) are required by regulation to have the “same” labeling as the reference drug listed. When the labeling is revised for the referenced drug, generic drug manufacturers also are required to update their labeling.

Q: In the new system, how will labeling stay up to date when important new data are published on a drug sometimes two to three times a year?

A: When new information becomes available that causes the labeling to be inaccurate, false, or misleading, drug manufacturers are required by regulation to update labeling.

Q: The rule is phased in over time. Drugs already on the market are given more time to switch to the new system. How long will physicians need to deal simultaneously with the old and the new formats?

A: There have been two labeling formats in use for some time as products approved prior to 2001 are not required to conform to either PLLR or PLR. The agency encourages manufacturers to voluntarily convert labeling of older products into PLR format. However, products approved prior to 2001 will be required to remove the pregnancy letter category by June 30, 2018, (3 years after the implementation of the PLLR).

Q: Does the FDA have any plans to address labeling for over-the-counter products in terms of their impact on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential?

A: The PLLR does not apply to over-the-counter products. However, the agency is continually reviewing the safety of products used over the counter, including impacts on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential.

Q: How does the FDA plan to assess over time the usefulness of the new labeling for prescribers and patients and make revisions?

A: The draft guidance was issued concurrently with PLLR. Based on the comments received from the public on the draft, as well as learning from the initial revisions of labeling, the guidance will be revised as needed. Guidance statements issued by FDA are regularly reviewed and revised as needed.

Dr. Whyte, a board-certified internist, is the director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagement at the FDA. Do you have other questions about the PLLR? Send them to [email protected].

On June 30, pharmaceutical and biological manufacturers will begin implementing the Food and Drug Administration’s revised rules for pregnancy and lactation drug labeling. The Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) amends the Physician Labeling Rule (PLR, issued in 2006) and new labels aimed at providing clearer and more accurate information on drug risks will gradually roll out over the next 5 years.

The new rule – several years in the making – replaces pregnancy categories A, B, C, D, and X with short, integrated summaries that provide physicians with more information for discussing with patients the risks and benefits of a medication. The summaries will be brief and easy to read, and will contain evidence-based information that specifically addresses drug risks for women during pregnancy and lactation, as well as for men and women of reproductive potential. Under the PLLR, the pregnancy subsection of the risk summary will include for the first time information for any drug that has a pregnancy exposure registry.

Dr. John Whyte, director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagment (PASE) at the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, answers questions about the new rule from Ob.Gyn. News journalists and our Drugs, Pregnancy & Lactation columnists.

Question: Instead of the traditional letter categories, prescribers will now have to read the pregnancy and lactation subsections of the labeling. What can the agency do to ensure prescribers are reading all of the new contextual information in the drug label?

Answer: The agency has initiated outreach efforts to help prescribers become familiar with the new information in labeling. The most important information is now under a new heading called Risk Summary. This narrative summary replaces the pregnancy letter categories with a summary of information that is known about a product. The new labeling rule explains, based on available information, the potential benefits and risks for the mother, the fetus, and the breastfeeding child. The decision to replace the pregnancy letter categories with the summary paragraph was reached after extensive consultation with experts and stakeholders who were concerned that the traditional letter categories were overly simplistic.

Q: PLLR praises the value of pregnancy exposure registries and mandates that if a registry exists for an approved product, then the label must include the registry’s website address. There is no requirement, however, that industry actually fund these registries. Why did the agency stop short of requiring companies to provide ongoing support for pregnancy exposure registries?

A: FDA has the authority to require the establishment of pregnancy registries when there is a safety concern that would benefit from the collection of data in a postapproval study, or when a particular product will be used by a large number of females of reproductive age. However, FDA does not have the authority to require companies to fund existing pregnancy exposure registries.

Q: How does the FDA plan to review all of the summary statements of available data regarding reproductive safety considering the breadth of drugs in various therapeutic areas that will need to be reviewed?

A: All labeling changes, including the changes required by the PLLR, must be submitted to the FDA for review and approval. Changes to the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of labeling have been integrated into standard labeling review processes. In addition, the Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health, in the Office of New Drugs, works with the primary review divisions to help coordinate PLLR review processes.

Q: Are the manufacturers of generic drugs expected to “piggyback” the label for a branded molecule with respect to the pregnancy label?

A: Generic drug products (Abbreviated New Drug Applications) are required by regulation to have the “same” labeling as the reference drug listed. When the labeling is revised for the referenced drug, generic drug manufacturers also are required to update their labeling.

Q: In the new system, how will labeling stay up to date when important new data are published on a drug sometimes two to three times a year?

A: When new information becomes available that causes the labeling to be inaccurate, false, or misleading, drug manufacturers are required by regulation to update labeling.

Q: The rule is phased in over time. Drugs already on the market are given more time to switch to the new system. How long will physicians need to deal simultaneously with the old and the new formats?

A: There have been two labeling formats in use for some time as products approved prior to 2001 are not required to conform to either PLLR or PLR. The agency encourages manufacturers to voluntarily convert labeling of older products into PLR format. However, products approved prior to 2001 will be required to remove the pregnancy letter category by June 30, 2018, (3 years after the implementation of the PLLR).

Q: Does the FDA have any plans to address labeling for over-the-counter products in terms of their impact on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential?

A: The PLLR does not apply to over-the-counter products. However, the agency is continually reviewing the safety of products used over the counter, including impacts on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential.

Q: How does the FDA plan to assess over time the usefulness of the new labeling for prescribers and patients and make revisions?

A: The draft guidance was issued concurrently with PLLR. Based on the comments received from the public on the draft, as well as learning from the initial revisions of labeling, the guidance will be revised as needed. Guidance statements issued by FDA are regularly reviewed and revised as needed.

Dr. Whyte, a board-certified internist, is the director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagement at the FDA. Do you have other questions about the PLLR? Send them to [email protected].

ADA: Stress may up risk for excess gestational weight gain

BOSTON – Psychosocial stress is an independent risk factor for excess weight gain among women with gestational diabetes mellitus, findings from the Gestational Diabetes Effects on Moms (GEM) study suggest.

Among nearly 1,300 women in the cluster randomized trial conducted within Kaiser Permanent Northern California, perceived stress near the time of gestational diabetes diagnosis at around 32 weeks’ gestation was significantly associated with a risk of excess gestational weight gain.

After adjusting for gestational and maternal age at the time of gestational diabetes diagnosis, education level, pregravid body mass index, and race/ethnicity, an upper-quartile score on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), compared with a lower score, was associated with a 54% increased odds of weight gain that exceeded Institute of Medicine recommendations (odds ratio, 1.54), Ai Kubo, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

A significant trend between PSS score and gestational weight gain was seen, and the association was not attenuated by inclusion of other lifestyle variables, including diet and physical activity, Dr. Kubo said, noting that no association was seen between PSS and the odds of gaining weight at a level below the IOM recommendations.

Dr. Kubo and her colleagues examined the relationship between stress and weight gain using baseline data from the GEM study. Subjects were women who delivered a term singleton at greater than 37 weeks’ gestation. Total gestational weight gain (about 20 pounds on average) and prepregnancy body mass index were obtained from electronic health records. Weight gain was categorized according to 2009 IOM recommendations.

Women with lower socioeconomic status tended to be in the highest stress group, and although there was no significant differences in prepregnancy weight between the highest and lowest stress groups, more of those with BMIs over 35 were in the highest stress group, she noted.

“Excess gestational weight gain has become an important public health concern,” Dr. Kubo said, noting that nearly 60% of women exceed IOM recommendations for weight gain, which increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, including obesity, in both women and their offspring.

Gestational diabetes mellitus occurs in about 8% of all pregnant women and also increases the risk of adverse outcomes in both mothers and offspring, she said.

The current findings suggest that stress reduction interventions may be warranted in women with gestational diabetes mellitus to optimize weight gain and possibly reduce the risks to both mother and offspring, she said, noting that the study is limited by a lack of assessment regarding the timing of stress relative to weight gain and gestational diabetes diagnosis.

“For future studies, use of a [non–gestational diabetes] population, and assessment of stress at the beginning of the pregnancy or even prior to the pregnancy would help us better understand the role of psychosocial stress on weight gain during pregnancy,” she said.

Dr. Kubo reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – Psychosocial stress is an independent risk factor for excess weight gain among women with gestational diabetes mellitus, findings from the Gestational Diabetes Effects on Moms (GEM) study suggest.

Among nearly 1,300 women in the cluster randomized trial conducted within Kaiser Permanent Northern California, perceived stress near the time of gestational diabetes diagnosis at around 32 weeks’ gestation was significantly associated with a risk of excess gestational weight gain.

After adjusting for gestational and maternal age at the time of gestational diabetes diagnosis, education level, pregravid body mass index, and race/ethnicity, an upper-quartile score on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), compared with a lower score, was associated with a 54% increased odds of weight gain that exceeded Institute of Medicine recommendations (odds ratio, 1.54), Ai Kubo, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

A significant trend between PSS score and gestational weight gain was seen, and the association was not attenuated by inclusion of other lifestyle variables, including diet and physical activity, Dr. Kubo said, noting that no association was seen between PSS and the odds of gaining weight at a level below the IOM recommendations.

Dr. Kubo and her colleagues examined the relationship between stress and weight gain using baseline data from the GEM study. Subjects were women who delivered a term singleton at greater than 37 weeks’ gestation. Total gestational weight gain (about 20 pounds on average) and prepregnancy body mass index were obtained from electronic health records. Weight gain was categorized according to 2009 IOM recommendations.

Women with lower socioeconomic status tended to be in the highest stress group, and although there was no significant differences in prepregnancy weight between the highest and lowest stress groups, more of those with BMIs over 35 were in the highest stress group, she noted.

“Excess gestational weight gain has become an important public health concern,” Dr. Kubo said, noting that nearly 60% of women exceed IOM recommendations for weight gain, which increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, including obesity, in both women and their offspring.

Gestational diabetes mellitus occurs in about 8% of all pregnant women and also increases the risk of adverse outcomes in both mothers and offspring, she said.

The current findings suggest that stress reduction interventions may be warranted in women with gestational diabetes mellitus to optimize weight gain and possibly reduce the risks to both mother and offspring, she said, noting that the study is limited by a lack of assessment regarding the timing of stress relative to weight gain and gestational diabetes diagnosis.

“For future studies, use of a [non–gestational diabetes] population, and assessment of stress at the beginning of the pregnancy or even prior to the pregnancy would help us better understand the role of psychosocial stress on weight gain during pregnancy,” she said.

Dr. Kubo reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – Psychosocial stress is an independent risk factor for excess weight gain among women with gestational diabetes mellitus, findings from the Gestational Diabetes Effects on Moms (GEM) study suggest.

Among nearly 1,300 women in the cluster randomized trial conducted within Kaiser Permanent Northern California, perceived stress near the time of gestational diabetes diagnosis at around 32 weeks’ gestation was significantly associated with a risk of excess gestational weight gain.

After adjusting for gestational and maternal age at the time of gestational diabetes diagnosis, education level, pregravid body mass index, and race/ethnicity, an upper-quartile score on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), compared with a lower score, was associated with a 54% increased odds of weight gain that exceeded Institute of Medicine recommendations (odds ratio, 1.54), Ai Kubo, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

A significant trend between PSS score and gestational weight gain was seen, and the association was not attenuated by inclusion of other lifestyle variables, including diet and physical activity, Dr. Kubo said, noting that no association was seen between PSS and the odds of gaining weight at a level below the IOM recommendations.

Dr. Kubo and her colleagues examined the relationship between stress and weight gain using baseline data from the GEM study. Subjects were women who delivered a term singleton at greater than 37 weeks’ gestation. Total gestational weight gain (about 20 pounds on average) and prepregnancy body mass index were obtained from electronic health records. Weight gain was categorized according to 2009 IOM recommendations.

Women with lower socioeconomic status tended to be in the highest stress group, and although there was no significant differences in prepregnancy weight between the highest and lowest stress groups, more of those with BMIs over 35 were in the highest stress group, she noted.

“Excess gestational weight gain has become an important public health concern,” Dr. Kubo said, noting that nearly 60% of women exceed IOM recommendations for weight gain, which increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, including obesity, in both women and their offspring.

Gestational diabetes mellitus occurs in about 8% of all pregnant women and also increases the risk of adverse outcomes in both mothers and offspring, she said.

The current findings suggest that stress reduction interventions may be warranted in women with gestational diabetes mellitus to optimize weight gain and possibly reduce the risks to both mother and offspring, she said, noting that the study is limited by a lack of assessment regarding the timing of stress relative to weight gain and gestational diabetes diagnosis.

“For future studies, use of a [non–gestational diabetes] population, and assessment of stress at the beginning of the pregnancy or even prior to the pregnancy would help us better understand the role of psychosocial stress on weight gain during pregnancy,” she said.

Dr. Kubo reported having no disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Psychosocial stress is an independent risk factor for excess weight gain among women with gestational diabetes mellitus, findings from the Gestational Diabetes Effects on Moms (GEM) study suggest.

Major finding: An upper-quartile score on the Perceived Stress Scale, compared with a lower score, was associated with a 54% increased odds of weight gain that exceeded Institute of Medicine recommendations (odds ratio, 1.54).

Data source: The cluster randomized GEM study of nearly 1,300 women.

Disclosures: Dr. Kubo reported having no disclosures.

Uncomplicated pregnancies in women with lupus may not boost risk for CV events

Pregnancy may not increase the risk of a cardiovascular event (CVE) in women with systemic lupus erythematosus as much as disease-related morbidities, according to findings from a large, retrospective study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In fact, uncomplicated pregnancy may be a positive marker for later cardiovascular health in lupus patients, Dr. May Ching Soh reported at the meeting.

“Physicians and patients may derive some reassurance that perhaps a pregnancy uncomplicated by maternal-placental pathology may be associated with lower risk for future cardiovascular events,” Dr. Soh said in an interview. “However, we cannot at this time recommend relaxing on our laurels and not screening and actively managing cardiovascular risk factors in all patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.”

Dr. Soh, an obstetrician in the Women’s Centre at Oxford Radcliffe Hospital, part of the Oxford (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, extracted data from linked Swedish population registries on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients’ parity status, the occurrence of features of maternal-placental syndrome (MPS, defined as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, small-for-gestational-age, stillbirth, and placental abruption), SLE-related morbidities (in-patient admissions, renal disease, malignancies, and infections), and CVE outcomes (coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and death from these causes).

The final cohort comprised 3,232 women with SLE who had been born in 1951-1971. A total of 72% had children.

The mean age at follow-up was 49 years. Nulliparous women had more SLE-related morbidities, more cardiovascular risk factors, and more cardiovascular events than did parous women.

CVEs were most common among those women who had never given birth (3.4 per 1,000 person-years), followed by women with pregnancies complicated by MPS (2.8 per 1,000 person-years). Compared with women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy, the risk of a CVE was doubled in the nulliparous group (hazard ratio, 2.2) and close to double in the MPS-pregnancy group (HR, 1.8).

The time to first CVE also was significantly delayed in women who had uncomplicated pregnancies. By age 30, almost none had occurred in these women, but 5% of those with MPS-complicated pregnancies and 10% of the nulliparous women had experienced an event by that age. The separation continued as women aged. By age 40, an event had occurred in about 4% of the MPS-free women, 8% of the MPS group, and 10% of the nulliparous group. The rates at age 45 were 5%, 8%, and 15%, respectively.

“Our nonparous cohort did develop cardiovascular events earlier, but the MPS cohort also had accelerated development compared to the women who had uncomplicated pregnancies,” Dr. Soh said. “In fact, an adverse pregnancy outcome should serve as a red flag for physicians to start screening early for cardiovascular disease and actively managing risk factors.”

She had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Pregnancy may not increase the risk of a cardiovascular event (CVE) in women with systemic lupus erythematosus as much as disease-related morbidities, according to findings from a large, retrospective study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In fact, uncomplicated pregnancy may be a positive marker for later cardiovascular health in lupus patients, Dr. May Ching Soh reported at the meeting.

“Physicians and patients may derive some reassurance that perhaps a pregnancy uncomplicated by maternal-placental pathology may be associated with lower risk for future cardiovascular events,” Dr. Soh said in an interview. “However, we cannot at this time recommend relaxing on our laurels and not screening and actively managing cardiovascular risk factors in all patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.”

Dr. Soh, an obstetrician in the Women’s Centre at Oxford Radcliffe Hospital, part of the Oxford (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, extracted data from linked Swedish population registries on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients’ parity status, the occurrence of features of maternal-placental syndrome (MPS, defined as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, small-for-gestational-age, stillbirth, and placental abruption), SLE-related morbidities (in-patient admissions, renal disease, malignancies, and infections), and CVE outcomes (coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and death from these causes).

The final cohort comprised 3,232 women with SLE who had been born in 1951-1971. A total of 72% had children.

The mean age at follow-up was 49 years. Nulliparous women had more SLE-related morbidities, more cardiovascular risk factors, and more cardiovascular events than did parous women.

CVEs were most common among those women who had never given birth (3.4 per 1,000 person-years), followed by women with pregnancies complicated by MPS (2.8 per 1,000 person-years). Compared with women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy, the risk of a CVE was doubled in the nulliparous group (hazard ratio, 2.2) and close to double in the MPS-pregnancy group (HR, 1.8).

The time to first CVE also was significantly delayed in women who had uncomplicated pregnancies. By age 30, almost none had occurred in these women, but 5% of those with MPS-complicated pregnancies and 10% of the nulliparous women had experienced an event by that age. The separation continued as women aged. By age 40, an event had occurred in about 4% of the MPS-free women, 8% of the MPS group, and 10% of the nulliparous group. The rates at age 45 were 5%, 8%, and 15%, respectively.

“Our nonparous cohort did develop cardiovascular events earlier, but the MPS cohort also had accelerated development compared to the women who had uncomplicated pregnancies,” Dr. Soh said. “In fact, an adverse pregnancy outcome should serve as a red flag for physicians to start screening early for cardiovascular disease and actively managing risk factors.”

She had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Pregnancy may not increase the risk of a cardiovascular event (CVE) in women with systemic lupus erythematosus as much as disease-related morbidities, according to findings from a large, retrospective study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In fact, uncomplicated pregnancy may be a positive marker for later cardiovascular health in lupus patients, Dr. May Ching Soh reported at the meeting.

“Physicians and patients may derive some reassurance that perhaps a pregnancy uncomplicated by maternal-placental pathology may be associated with lower risk for future cardiovascular events,” Dr. Soh said in an interview. “However, we cannot at this time recommend relaxing on our laurels and not screening and actively managing cardiovascular risk factors in all patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.”

Dr. Soh, an obstetrician in the Women’s Centre at Oxford Radcliffe Hospital, part of the Oxford (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, extracted data from linked Swedish population registries on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients’ parity status, the occurrence of features of maternal-placental syndrome (MPS, defined as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, small-for-gestational-age, stillbirth, and placental abruption), SLE-related morbidities (in-patient admissions, renal disease, malignancies, and infections), and CVE outcomes (coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and death from these causes).

The final cohort comprised 3,232 women with SLE who had been born in 1951-1971. A total of 72% had children.

The mean age at follow-up was 49 years. Nulliparous women had more SLE-related morbidities, more cardiovascular risk factors, and more cardiovascular events than did parous women.

CVEs were most common among those women who had never given birth (3.4 per 1,000 person-years), followed by women with pregnancies complicated by MPS (2.8 per 1,000 person-years). Compared with women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy, the risk of a CVE was doubled in the nulliparous group (hazard ratio, 2.2) and close to double in the MPS-pregnancy group (HR, 1.8).

The time to first CVE also was significantly delayed in women who had uncomplicated pregnancies. By age 30, almost none had occurred in these women, but 5% of those with MPS-complicated pregnancies and 10% of the nulliparous women had experienced an event by that age. The separation continued as women aged. By age 40, an event had occurred in about 4% of the MPS-free women, 8% of the MPS group, and 10% of the nulliparous group. The rates at age 45 were 5%, 8%, and 15%, respectively.

“Our nonparous cohort did develop cardiovascular events earlier, but the MPS cohort also had accelerated development compared to the women who had uncomplicated pregnancies,” Dr. Soh said. “In fact, an adverse pregnancy outcome should serve as a red flag for physicians to start screening early for cardiovascular disease and actively managing risk factors.”

She had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM THE EULAR 2015 CONGRESS

Key clinical point: An uncomplicated pregnancy doesn’t appear to accelerate the risk of cardiovascular events in women with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Major finding: Nulliparous women or women who had a pregnancy complicated by lupus had twice the risk for a cardiovascular event, compared with women who had an uncomplicated pregnancy.

Data source: The retrospective cohort study involved 3,232 women.

Disclosures: Dr. Soh had no financial disclosures.

Diet, exercise in pregnancy keep excessive weight gain in check

Expectant mothers can reduce the likelihood that they will gain too much weight during pregnancy by improving their diet, increasing their exercise, or using a combined diet and exercise program, according to an updated Cochrane review.

The original review published in 2012 found too little evidence to conclude that diet and exercise interventions could benefit pregnant women and their newborns, but the update includes an additional 41 randomized controlled studies published between October 2011 and November 2014, along with 24 studies from the original review.

“Moderate-intensity exercise appears to be an important part of controlling weight gain in pregnancy; however, the evidence on the risk of preterm birth is limited, and more research is needed to establish safe guidelines,” wrote Benja Muktabhant of Khon Kaen (Thailand) University and associates (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 June 10 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007145.pub3]).

Excessive weight gain in pregnancy is well known to increase the risk for poor maternal and neonatal outcomes, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, cesarean delivery, macrosomia, and stillbirth. But research shows that pregnant women continue to struggle to stay within recommended weight limits. In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended that normal weight women with singleton pregnancies gain 25-35 pounds, while overweight women should gain 15-25 pounds. For obese women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, the IOM recommendation is 11-20 pounds of weight gain.

In the current review, the researchers identified a total of 65 randomized controlled trials that focused on using exercise, diet, or both to prevent excessive gestational weight gain. The 49 studies that were part of the quantitative meta-analysis included 11,444 women, but the methodologies varied greatly among the studies, and 20 studies had a moderate to high risk of bias. Further, the majority of studies included participants from high-income countries, primarily the United States, Canada, Australia, and European countries, making generalization to lower-income populations difficult to assess.

Using diet, exercise, or both reduced the risk of excessive weight gain in pregnancy by 20% based on 24 studies involving 7,096 participants. This evidence, rated high quality, found that low-glycemic-load diets, exercise with and without supervision, and combined diet and exercise programs all reduced women’s weights by similar amounts. Diet and/or exercise programs also increased the likelihood by 14% that women would have a low gestational weight gain, based on 4,422 participants in 11 studies with moderate-quality evidence.

Exercise programs included moderate exercise such as walking, dance, or aerobics.

The risk of maternal hypertension was lower in the diet and/or exercise intervention groups based on 11 studies involving 5,162 participants, but the researchers graded the evidence as low quality because of inconsistency and risk of bias concerns. The researchers found no reduced risk for preeclampsia in the 15 studies that included it as an outcome.

Similarly, the 16 studies assessing preterm birth and the 28 studies assessing risk of cesarean delivery found no difference between the intervention and control groups. However, when the researchers looked only at a combined diet and exercise intervention, they found a 13% reduction in cesarean delivery, which had borderline statistical significance.

The potential risk reduction of infant macrosomia depended on a woman’s prepregnancy weight, with only the findings for overweight or obese women, or those with or at risk for gestational diabetes, barely reaching statistical significance. Among the 27 studies with 8,598 participants that included macrosomia as an outcome, the 7% lower risk for oversized newborns just missed statistical significance. Among high-risk women, combined diet and exercise counseling reduced macrosomia risk by 15% (P = .05) with moderate-quality evidence from 3,252 participants in nine studies.

There was no difference between the two groups in risk for shoulder dystocia, neonatal hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and birth trauma, according to the review.

The project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom, and the World Health Organization. The researchers reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Expectant mothers can reduce the likelihood that they will gain too much weight during pregnancy by improving their diet, increasing their exercise, or using a combined diet and exercise program, according to an updated Cochrane review.

The original review published in 2012 found too little evidence to conclude that diet and exercise interventions could benefit pregnant women and their newborns, but the update includes an additional 41 randomized controlled studies published between October 2011 and November 2014, along with 24 studies from the original review.

“Moderate-intensity exercise appears to be an important part of controlling weight gain in pregnancy; however, the evidence on the risk of preterm birth is limited, and more research is needed to establish safe guidelines,” wrote Benja Muktabhant of Khon Kaen (Thailand) University and associates (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 June 10 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007145.pub3]).

Excessive weight gain in pregnancy is well known to increase the risk for poor maternal and neonatal outcomes, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, cesarean delivery, macrosomia, and stillbirth. But research shows that pregnant women continue to struggle to stay within recommended weight limits. In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended that normal weight women with singleton pregnancies gain 25-35 pounds, while overweight women should gain 15-25 pounds. For obese women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, the IOM recommendation is 11-20 pounds of weight gain.

In the current review, the researchers identified a total of 65 randomized controlled trials that focused on using exercise, diet, or both to prevent excessive gestational weight gain. The 49 studies that were part of the quantitative meta-analysis included 11,444 women, but the methodologies varied greatly among the studies, and 20 studies had a moderate to high risk of bias. Further, the majority of studies included participants from high-income countries, primarily the United States, Canada, Australia, and European countries, making generalization to lower-income populations difficult to assess.

Using diet, exercise, or both reduced the risk of excessive weight gain in pregnancy by 20% based on 24 studies involving 7,096 participants. This evidence, rated high quality, found that low-glycemic-load diets, exercise with and without supervision, and combined diet and exercise programs all reduced women’s weights by similar amounts. Diet and/or exercise programs also increased the likelihood by 14% that women would have a low gestational weight gain, based on 4,422 participants in 11 studies with moderate-quality evidence.

Exercise programs included moderate exercise such as walking, dance, or aerobics.

The risk of maternal hypertension was lower in the diet and/or exercise intervention groups based on 11 studies involving 5,162 participants, but the researchers graded the evidence as low quality because of inconsistency and risk of bias concerns. The researchers found no reduced risk for preeclampsia in the 15 studies that included it as an outcome.

Similarly, the 16 studies assessing preterm birth and the 28 studies assessing risk of cesarean delivery found no difference between the intervention and control groups. However, when the researchers looked only at a combined diet and exercise intervention, they found a 13% reduction in cesarean delivery, which had borderline statistical significance.

The potential risk reduction of infant macrosomia depended on a woman’s prepregnancy weight, with only the findings for overweight or obese women, or those with or at risk for gestational diabetes, barely reaching statistical significance. Among the 27 studies with 8,598 participants that included macrosomia as an outcome, the 7% lower risk for oversized newborns just missed statistical significance. Among high-risk women, combined diet and exercise counseling reduced macrosomia risk by 15% (P = .05) with moderate-quality evidence from 3,252 participants in nine studies.

There was no difference between the two groups in risk for shoulder dystocia, neonatal hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and birth trauma, according to the review.

The project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom, and the World Health Organization. The researchers reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Expectant mothers can reduce the likelihood that they will gain too much weight during pregnancy by improving their diet, increasing their exercise, or using a combined diet and exercise program, according to an updated Cochrane review.

The original review published in 2012 found too little evidence to conclude that diet and exercise interventions could benefit pregnant women and their newborns, but the update includes an additional 41 randomized controlled studies published between October 2011 and November 2014, along with 24 studies from the original review.

“Moderate-intensity exercise appears to be an important part of controlling weight gain in pregnancy; however, the evidence on the risk of preterm birth is limited, and more research is needed to establish safe guidelines,” wrote Benja Muktabhant of Khon Kaen (Thailand) University and associates (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 June 10 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007145.pub3]).

Excessive weight gain in pregnancy is well known to increase the risk for poor maternal and neonatal outcomes, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, cesarean delivery, macrosomia, and stillbirth. But research shows that pregnant women continue to struggle to stay within recommended weight limits. In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended that normal weight women with singleton pregnancies gain 25-35 pounds, while overweight women should gain 15-25 pounds. For obese women with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, the IOM recommendation is 11-20 pounds of weight gain.

In the current review, the researchers identified a total of 65 randomized controlled trials that focused on using exercise, diet, or both to prevent excessive gestational weight gain. The 49 studies that were part of the quantitative meta-analysis included 11,444 women, but the methodologies varied greatly among the studies, and 20 studies had a moderate to high risk of bias. Further, the majority of studies included participants from high-income countries, primarily the United States, Canada, Australia, and European countries, making generalization to lower-income populations difficult to assess.

Using diet, exercise, or both reduced the risk of excessive weight gain in pregnancy by 20% based on 24 studies involving 7,096 participants. This evidence, rated high quality, found that low-glycemic-load diets, exercise with and without supervision, and combined diet and exercise programs all reduced women’s weights by similar amounts. Diet and/or exercise programs also increased the likelihood by 14% that women would have a low gestational weight gain, based on 4,422 participants in 11 studies with moderate-quality evidence.

Exercise programs included moderate exercise such as walking, dance, or aerobics.

The risk of maternal hypertension was lower in the diet and/or exercise intervention groups based on 11 studies involving 5,162 participants, but the researchers graded the evidence as low quality because of inconsistency and risk of bias concerns. The researchers found no reduced risk for preeclampsia in the 15 studies that included it as an outcome.

Similarly, the 16 studies assessing preterm birth and the 28 studies assessing risk of cesarean delivery found no difference between the intervention and control groups. However, when the researchers looked only at a combined diet and exercise intervention, they found a 13% reduction in cesarean delivery, which had borderline statistical significance.

The potential risk reduction of infant macrosomia depended on a woman’s prepregnancy weight, with only the findings for overweight or obese women, or those with or at risk for gestational diabetes, barely reaching statistical significance. Among the 27 studies with 8,598 participants that included macrosomia as an outcome, the 7% lower risk for oversized newborns just missed statistical significance. Among high-risk women, combined diet and exercise counseling reduced macrosomia risk by 15% (P = .05) with moderate-quality evidence from 3,252 participants in nine studies.

There was no difference between the two groups in risk for shoulder dystocia, neonatal hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and birth trauma, according to the review.

The project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom, and the World Health Organization. The researchers reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

FROM COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Key clinical point: Diet and/or exercise programs reduce the risk of excessive gestational weight gain.

Major finding: Women using diet and/or exercise interventions had a 20% lower risk of excessive weight gain during pregnancy.

Data source: An updated Cochrane review including 65 studies through November 2014, 49 of which were part of the overall meta-analysis with a combined 11,444 participants.

Disclosures: The project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom, and the World Health Organization. The researchers reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Pregnancy weight changes infant metabolic profiles

BOSTON – Maternal obesity and increased weight gain during pregnancy are associated with changes to newborns’ cardiometabolic markers, and these associations are largely independent of infant adiposity, according to new research findings.

Maternal obesity and weight gain during pregnancy are established risk factors for childhood obesity, but the reasons for this remain little understood.

In utero programming of infant metabolism may be occurring, providing reasons beyond fetal growth and fat accretion for the differences in lipid and hormonal profiles among infants, judging from the findings reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Presenting data from a cohort of 753 mother-infant pairs, Dominick J. Lemas, Ph.D., of the University of Colorado, Denver, said that samples of cord blood revealed “striking” associations.

Dr. Lemas and his colleagues found higher levels of cord blood glucose (P = .03), and leptin (P < .001) in newborns among mothers who gained more weight during pregnancy. Infants of women with higher body mass index when they became pregnant saw higher levels of leptin (P < .001) in cord blood and lower levels of HDL cholesterol (P = .05), even after adjusting for infant adiposity.

The leptin finding was particularly surprising, Dr. Lemas said. Leptin, a hormone that regulates food intake, energy output, and other functions, is synthesized by fatty tissues and therefore expected to be found in higher levels among infants with fatter body composition.

In this study, however, “the association actually became stronger when we adjusted for the adiposity of the infant,” he said.

The investigators looked carefully at cord blood lipids, including total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids. The finding that prepregnancy BMI was negatively associated with HDL cholesterol “was something very interesting for our group,” Dr. Lemas said at the conference. “In adults, abnormal lipid patterns are a very strong predictor of cardiovascular disease.”

The findings raise two main concerns, Dr. Lemas said. First, “what factors beyond maternal BMI and gestational weight gain contribute to the changes to these cardiometabolic biomarkers at delivery?” And second, he said, it remains to be seen if these markers persist or result in clinically meaningful differences: “It’s possible cord-blood biomarkers don’t predict the metabolic risk of these individuals a few years down the road.”

The investigators used data from Healthy Start, a cohort study funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. They disclosed no conflicts of interest, and the full paper on their findings will be published in the International Journal of Obesity.

BOSTON – Maternal obesity and increased weight gain during pregnancy are associated with changes to newborns’ cardiometabolic markers, and these associations are largely independent of infant adiposity, according to new research findings.

Maternal obesity and weight gain during pregnancy are established risk factors for childhood obesity, but the reasons for this remain little understood.

In utero programming of infant metabolism may be occurring, providing reasons beyond fetal growth and fat accretion for the differences in lipid and hormonal profiles among infants, judging from the findings reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Presenting data from a cohort of 753 mother-infant pairs, Dominick J. Lemas, Ph.D., of the University of Colorado, Denver, said that samples of cord blood revealed “striking” associations.

Dr. Lemas and his colleagues found higher levels of cord blood glucose (P = .03), and leptin (P < .001) in newborns among mothers who gained more weight during pregnancy. Infants of women with higher body mass index when they became pregnant saw higher levels of leptin (P < .001) in cord blood and lower levels of HDL cholesterol (P = .05), even after adjusting for infant adiposity.

The leptin finding was particularly surprising, Dr. Lemas said. Leptin, a hormone that regulates food intake, energy output, and other functions, is synthesized by fatty tissues and therefore expected to be found in higher levels among infants with fatter body composition.

In this study, however, “the association actually became stronger when we adjusted for the adiposity of the infant,” he said.

The investigators looked carefully at cord blood lipids, including total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids. The finding that prepregnancy BMI was negatively associated with HDL cholesterol “was something very interesting for our group,” Dr. Lemas said at the conference. “In adults, abnormal lipid patterns are a very strong predictor of cardiovascular disease.”

The findings raise two main concerns, Dr. Lemas said. First, “what factors beyond maternal BMI and gestational weight gain contribute to the changes to these cardiometabolic biomarkers at delivery?” And second, he said, it remains to be seen if these markers persist or result in clinically meaningful differences: “It’s possible cord-blood biomarkers don’t predict the metabolic risk of these individuals a few years down the road.”

The investigators used data from Healthy Start, a cohort study funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. They disclosed no conflicts of interest, and the full paper on their findings will be published in the International Journal of Obesity.

BOSTON – Maternal obesity and increased weight gain during pregnancy are associated with changes to newborns’ cardiometabolic markers, and these associations are largely independent of infant adiposity, according to new research findings.

Maternal obesity and weight gain during pregnancy are established risk factors for childhood obesity, but the reasons for this remain little understood.

In utero programming of infant metabolism may be occurring, providing reasons beyond fetal growth and fat accretion for the differences in lipid and hormonal profiles among infants, judging from the findings reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Presenting data from a cohort of 753 mother-infant pairs, Dominick J. Lemas, Ph.D., of the University of Colorado, Denver, said that samples of cord blood revealed “striking” associations.

Dr. Lemas and his colleagues found higher levels of cord blood glucose (P = .03), and leptin (P < .001) in newborns among mothers who gained more weight during pregnancy. Infants of women with higher body mass index when they became pregnant saw higher levels of leptin (P < .001) in cord blood and lower levels of HDL cholesterol (P = .05), even after adjusting for infant adiposity.

The leptin finding was particularly surprising, Dr. Lemas said. Leptin, a hormone that regulates food intake, energy output, and other functions, is synthesized by fatty tissues and therefore expected to be found in higher levels among infants with fatter body composition.

In this study, however, “the association actually became stronger when we adjusted for the adiposity of the infant,” he said.

The investigators looked carefully at cord blood lipids, including total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids. The finding that prepregnancy BMI was negatively associated with HDL cholesterol “was something very interesting for our group,” Dr. Lemas said at the conference. “In adults, abnormal lipid patterns are a very strong predictor of cardiovascular disease.”

The findings raise two main concerns, Dr. Lemas said. First, “what factors beyond maternal BMI and gestational weight gain contribute to the changes to these cardiometabolic biomarkers at delivery?” And second, he said, it remains to be seen if these markers persist or result in clinically meaningful differences: “It’s possible cord-blood biomarkers don’t predict the metabolic risk of these individuals a few years down the road.”

The investigators used data from Healthy Start, a cohort study funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. They disclosed no conflicts of interest, and the full paper on their findings will be published in the International Journal of Obesity.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS