User login

VIDEO: Don’t forget folate for women on antiepilepsy drugs

WASHINGTON – Only 20% of women of childbearing age taking antiepileptic drugs also received a folate prescription, a small study revealed – but a brief intervention helped boost the rate above 60%.

Folic acid supplementation is de rigueur for women of childbearing age – and especially important in very early pregnancy. The need appears even greater in women who take antiepileptic drugs, many of which increase the risk of birth defects.

Despite current recommendations for folic acid supplementation in all women, prescription by neurologists seems low, according to Dr. Brian D. Moseley of the University of Cincinnati.

“We wanted to look at the rates of the prescription of folic acid to women on antiepileptic drugs who were seen in our general neurology clinic,” Dr. Moseley explained.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, Dr. Moseley discussed the study’s findings, how a brief intervention with the clinic’s physicians increased folic acid prescription rates, and which folic acid dosages may be optimal.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Only 20% of women of childbearing age taking antiepileptic drugs also received a folate prescription, a small study revealed – but a brief intervention helped boost the rate above 60%.

Folic acid supplementation is de rigueur for women of childbearing age – and especially important in very early pregnancy. The need appears even greater in women who take antiepileptic drugs, many of which increase the risk of birth defects.

Despite current recommendations for folic acid supplementation in all women, prescription by neurologists seems low, according to Dr. Brian D. Moseley of the University of Cincinnati.

“We wanted to look at the rates of the prescription of folic acid to women on antiepileptic drugs who were seen in our general neurology clinic,” Dr. Moseley explained.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, Dr. Moseley discussed the study’s findings, how a brief intervention with the clinic’s physicians increased folic acid prescription rates, and which folic acid dosages may be optimal.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Only 20% of women of childbearing age taking antiepileptic drugs also received a folate prescription, a small study revealed – but a brief intervention helped boost the rate above 60%.

Folic acid supplementation is de rigueur for women of childbearing age – and especially important in very early pregnancy. The need appears even greater in women who take antiepileptic drugs, many of which increase the risk of birth defects.

Despite current recommendations for folic acid supplementation in all women, prescription by neurologists seems low, according to Dr. Brian D. Moseley of the University of Cincinnati.

“We wanted to look at the rates of the prescription of folic acid to women on antiepileptic drugs who were seen in our general neurology clinic,” Dr. Moseley explained.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, Dr. Moseley discussed the study’s findings, how a brief intervention with the clinic’s physicians increased folic acid prescription rates, and which folic acid dosages may be optimal.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE AAN 2015 ANNUAL MEETING

Hepatitis B perinatal infection risk factors identified

Hepatitis B vertical infections are rare, but they are more likely if any of several risk factors are present, according to the results of a study led by Dr. Sarah Schillie.

Dr. Schillie of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates analyzed prospectively collected data from 2007 to 2013 on 17,951 infant-mother pairs (including 15,938 mothers) in five U.S.-funded Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Programs in Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, and most of Texas. The mothers had a median age of 30 years, and all tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).

Most infants born to mothers with active hepatitis B virus (HBV) received the vaccine plus immune globulin, but 1.1% acquired the infection perinatally (Pediatrics 2014 April 20 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3213]).

Newborns were more likely to acquire an infection if their mother was younger, was of Asian or Pacific Islander race, tested positive for hepatitis B antigens, tested negative for antibodies to hepatitis B antigens, or had a viral load of at least 2,000 IU/mL.

Further, 6.7% of infants with fewer than three doses of the vaccine developed an HBV infection, compared with 1.1% of infants who received at least three doses. Developing an infection was not linked to gestational age, birth weight, or timing of the vaccine or immune globulin (within or after 12 hours of birth).

“The identification of women with a higher risk of perinatal hepatitis B transmission in the context of optimal postexposure prophylaxis suggests that interventions such as maternal antiviral therapy might further decrease or eliminate perinatal hepatitis B infections,” Dr. Schillie and her associates reported.

Among 11,479 infants with information on HBV vaccine timing, 96.4% received the vaccine within 12 hours of birth; 95.5% of 11,633 newborns with timing data received hepatitis B immune globulin. Among 11,335 newborns with information available, 94.9% received both. HBsAg results were available for 51.5% of the total group (9,252 infants): 99.5% of these received at least three doses of the vaccine, and 1.1% (100 infants) acquired HBV perinatal infections.

The research was funded by the CDC and the U.S. Department of Energy. The authors reported no disclosures.

Much of the data [Dr. Schillie and her associates] share is good news. These results should cause us to stop and recognize the scope and success of the tremendous efforts of everyone involved in preventing HBV vertical transmission.

This article should also spur us to take the next step in HBV prevention. Some studies have shown that using antiviral agents, specifically tenofovir, to suppress HBV DNA in pregnant women with active disease in the third trimester can prevent vertical transmission when combined with standard of care. Many adult hepatologists already do this routinely for those women with chronic HBV infection with risk factors for vertical transmission prophylaxis failure when they become pregnant.

To find the women with previously unknown disease, we as a medical community need to broaden, standardize, and implement these practices so they can be used by everyone. Further studies are important because there are tangible downstream risks to using antiviral agents during pregnancy. Women in the “immune tolerant” phase of chronic HBV, with HBV e antigen–positive and high-level HBV DNA in the absence of symptoms or elevated liver enzymes, may transition to a more active phase of hepatitis when treatment is stopped post partum. Despite the published warning, there is likely little infant drug exposure if a woman breastfeeds while taking tenofovir, but fetal drug exposure before delivery could have some long-term effect that is not yet appreciated.

It is clear that we have come a long way in preventing HBV vertical transmission. It is also clear that it is time to take the next step. We have the tools available; we just need to have the will.

Dr. Ravi Jhaveri is a pediatric infectious diseases expert at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. These comments were excerpted from an editorial accompanying Dr. Schillie’s study (Pediatrics 2015 [doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0360]). Dr. Jhaveri reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Much of the data [Dr. Schillie and her associates] share is good news. These results should cause us to stop and recognize the scope and success of the tremendous efforts of everyone involved in preventing HBV vertical transmission.

This article should also spur us to take the next step in HBV prevention. Some studies have shown that using antiviral agents, specifically tenofovir, to suppress HBV DNA in pregnant women with active disease in the third trimester can prevent vertical transmission when combined with standard of care. Many adult hepatologists already do this routinely for those women with chronic HBV infection with risk factors for vertical transmission prophylaxis failure when they become pregnant.

To find the women with previously unknown disease, we as a medical community need to broaden, standardize, and implement these practices so they can be used by everyone. Further studies are important because there are tangible downstream risks to using antiviral agents during pregnancy. Women in the “immune tolerant” phase of chronic HBV, with HBV e antigen–positive and high-level HBV DNA in the absence of symptoms or elevated liver enzymes, may transition to a more active phase of hepatitis when treatment is stopped post partum. Despite the published warning, there is likely little infant drug exposure if a woman breastfeeds while taking tenofovir, but fetal drug exposure before delivery could have some long-term effect that is not yet appreciated.

It is clear that we have come a long way in preventing HBV vertical transmission. It is also clear that it is time to take the next step. We have the tools available; we just need to have the will.

Dr. Ravi Jhaveri is a pediatric infectious diseases expert at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. These comments were excerpted from an editorial accompanying Dr. Schillie’s study (Pediatrics 2015 [doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0360]). Dr. Jhaveri reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Much of the data [Dr. Schillie and her associates] share is good news. These results should cause us to stop and recognize the scope and success of the tremendous efforts of everyone involved in preventing HBV vertical transmission.

This article should also spur us to take the next step in HBV prevention. Some studies have shown that using antiviral agents, specifically tenofovir, to suppress HBV DNA in pregnant women with active disease in the third trimester can prevent vertical transmission when combined with standard of care. Many adult hepatologists already do this routinely for those women with chronic HBV infection with risk factors for vertical transmission prophylaxis failure when they become pregnant.

To find the women with previously unknown disease, we as a medical community need to broaden, standardize, and implement these practices so they can be used by everyone. Further studies are important because there are tangible downstream risks to using antiviral agents during pregnancy. Women in the “immune tolerant” phase of chronic HBV, with HBV e antigen–positive and high-level HBV DNA in the absence of symptoms or elevated liver enzymes, may transition to a more active phase of hepatitis when treatment is stopped post partum. Despite the published warning, there is likely little infant drug exposure if a woman breastfeeds while taking tenofovir, but fetal drug exposure before delivery could have some long-term effect that is not yet appreciated.

It is clear that we have come a long way in preventing HBV vertical transmission. It is also clear that it is time to take the next step. We have the tools available; we just need to have the will.

Dr. Ravi Jhaveri is a pediatric infectious diseases expert at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. These comments were excerpted from an editorial accompanying Dr. Schillie’s study (Pediatrics 2015 [doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0360]). Dr. Jhaveri reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Hepatitis B vertical infections are rare, but they are more likely if any of several risk factors are present, according to the results of a study led by Dr. Sarah Schillie.

Dr. Schillie of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates analyzed prospectively collected data from 2007 to 2013 on 17,951 infant-mother pairs (including 15,938 mothers) in five U.S.-funded Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Programs in Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, and most of Texas. The mothers had a median age of 30 years, and all tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).

Most infants born to mothers with active hepatitis B virus (HBV) received the vaccine plus immune globulin, but 1.1% acquired the infection perinatally (Pediatrics 2014 April 20 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3213]).

Newborns were more likely to acquire an infection if their mother was younger, was of Asian or Pacific Islander race, tested positive for hepatitis B antigens, tested negative for antibodies to hepatitis B antigens, or had a viral load of at least 2,000 IU/mL.

Further, 6.7% of infants with fewer than three doses of the vaccine developed an HBV infection, compared with 1.1% of infants who received at least three doses. Developing an infection was not linked to gestational age, birth weight, or timing of the vaccine or immune globulin (within or after 12 hours of birth).

“The identification of women with a higher risk of perinatal hepatitis B transmission in the context of optimal postexposure prophylaxis suggests that interventions such as maternal antiviral therapy might further decrease or eliminate perinatal hepatitis B infections,” Dr. Schillie and her associates reported.

Among 11,479 infants with information on HBV vaccine timing, 96.4% received the vaccine within 12 hours of birth; 95.5% of 11,633 newborns with timing data received hepatitis B immune globulin. Among 11,335 newborns with information available, 94.9% received both. HBsAg results were available for 51.5% of the total group (9,252 infants): 99.5% of these received at least three doses of the vaccine, and 1.1% (100 infants) acquired HBV perinatal infections.

The research was funded by the CDC and the U.S. Department of Energy. The authors reported no disclosures.

Hepatitis B vertical infections are rare, but they are more likely if any of several risk factors are present, according to the results of a study led by Dr. Sarah Schillie.

Dr. Schillie of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates analyzed prospectively collected data from 2007 to 2013 on 17,951 infant-mother pairs (including 15,938 mothers) in five U.S.-funded Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Programs in Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, and most of Texas. The mothers had a median age of 30 years, and all tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).

Most infants born to mothers with active hepatitis B virus (HBV) received the vaccine plus immune globulin, but 1.1% acquired the infection perinatally (Pediatrics 2014 April 20 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3213]).

Newborns were more likely to acquire an infection if their mother was younger, was of Asian or Pacific Islander race, tested positive for hepatitis B antigens, tested negative for antibodies to hepatitis B antigens, or had a viral load of at least 2,000 IU/mL.

Further, 6.7% of infants with fewer than three doses of the vaccine developed an HBV infection, compared with 1.1% of infants who received at least three doses. Developing an infection was not linked to gestational age, birth weight, or timing of the vaccine or immune globulin (within or after 12 hours of birth).

“The identification of women with a higher risk of perinatal hepatitis B transmission in the context of optimal postexposure prophylaxis suggests that interventions such as maternal antiviral therapy might further decrease or eliminate perinatal hepatitis B infections,” Dr. Schillie and her associates reported.

Among 11,479 infants with information on HBV vaccine timing, 96.4% received the vaccine within 12 hours of birth; 95.5% of 11,633 newborns with timing data received hepatitis B immune globulin. Among 11,335 newborns with information available, 94.9% received both. HBsAg results were available for 51.5% of the total group (9,252 infants): 99.5% of these received at least three doses of the vaccine, and 1.1% (100 infants) acquired HBV perinatal infections.

The research was funded by the CDC and the U.S. Department of Energy. The authors reported no disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Several risk factors increase likelihood of hepatitis B perinatal transmission.

Major finding: Newborns were more likely to acquire an infection if their mother was younger, was of Asian or Pacific Islander race, tested positive for hepatitis B antigens, tested negative for antibodies to hepatitis B antigens, or had a viral load of at least 2,000 IU/mL.

Data source: The findings are based on an analysis of prospectively collected data on 17,951 mother-infant pairs at five U.S.-funded Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Programs in Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, and Texas from 2007 to 2013.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the CDC and U.S. Department of Energy. The authors reported no disclosures.

Risk factors identified for gestational eczema

HOUSTON– New-onset eczema during pregnancy is a common phenomenon with several newly identified risk factors.

This disease entity deserves a proper name: gestational eczema, Dr. Wilfried J.J. Karmaus asserted at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

In contrast, the likelihood of new-onset asthma arising during pregnancy isn’t significantly more common than in an affected woman’s male partner during the same time frame.

“There was no large difference in wheezing between the women and men. Therefore, we cannot propose the term ‘gestational asthma,’” said Dr. Karmaus, professor of epidemiology at the University of Memphis. “Investigations into how to prevent eczema and asthma in pregnancy are really important, because eczema and asthma in pregnancy can increase the risk of these diseases in the offspring. This is a totally undeveloped field.”

He presented new findings from the Isle of Wight study, a prospective study in which a cohort of women has been followed from birth through pregnancy across three generations.

Eczema and asthma are common atopic diseases, and they are particularly common during pregnancy. Indeed, eczema is the most common skin disease seen in pregnancy, accounting for 35%-50% of all dermatoses in previous studies by other investigators. In those studies, only 20%-40% of women with eczema during pregnancy had a prepregnancy history of the disease.

In the Isle of Wight cohort, women were evaluated for asthma and eczema symptoms at ages 1, 2, 4, 10, and 18 years and again during pregnancy at gestational weeks 20 and 28. A total of 26 of 116 women developed eczema during pregnancy, with eight of them (31%) experiencing the skin disease for the first time in their lives. In contrast, only six of their male partners had eczema during the pregnancy time frame, and just one of them had new-onset eczema.

A history of maternal eczema in the preceding generation was associated with a 52% increased relative risk of having eczema by age 18 and a 3.1-fold increased likelihood of eczema during pregnancy. Also, methylation of the filaggrin gene at the cytosine-phosphate-guanine site cg13447818 when assessed at age 18 was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of eczema in a subject’s mother as well as increased risk of gestational eczema 1-7 years later, Dr. Karmaus continued.

Eighteen percent of women in the Isle of Wight cohort had asthma during pregnancy, as did a similar proportion of their male partners. Twenty-seven percent of women with asthma during pregnancy had no previous history of the respiratory disease, a rate which was again comparable in their male partners with asthma.

DNA methylation of the IL1RL1 gene at cg17738684 was significantly associated with asthma heritability across three generations in the Isle of Wight study. The IL1RL1 gene at cg17738684 is a candidate gene for asthma that encodes for interleukin-33. This finding raises the possibility that addressing this DNA methylation could prove fruitful as a transgenerational asthma prevention strategy.

The Isle of Wight birth cohort study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Asthma UK, and the Isle of Wight Trust. Dr. Karmaus reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

HOUSTON– New-onset eczema during pregnancy is a common phenomenon with several newly identified risk factors.

This disease entity deserves a proper name: gestational eczema, Dr. Wilfried J.J. Karmaus asserted at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

In contrast, the likelihood of new-onset asthma arising during pregnancy isn’t significantly more common than in an affected woman’s male partner during the same time frame.

“There was no large difference in wheezing between the women and men. Therefore, we cannot propose the term ‘gestational asthma,’” said Dr. Karmaus, professor of epidemiology at the University of Memphis. “Investigations into how to prevent eczema and asthma in pregnancy are really important, because eczema and asthma in pregnancy can increase the risk of these diseases in the offspring. This is a totally undeveloped field.”

He presented new findings from the Isle of Wight study, a prospective study in which a cohort of women has been followed from birth through pregnancy across three generations.

Eczema and asthma are common atopic diseases, and they are particularly common during pregnancy. Indeed, eczema is the most common skin disease seen in pregnancy, accounting for 35%-50% of all dermatoses in previous studies by other investigators. In those studies, only 20%-40% of women with eczema during pregnancy had a prepregnancy history of the disease.

In the Isle of Wight cohort, women were evaluated for asthma and eczema symptoms at ages 1, 2, 4, 10, and 18 years and again during pregnancy at gestational weeks 20 and 28. A total of 26 of 116 women developed eczema during pregnancy, with eight of them (31%) experiencing the skin disease for the first time in their lives. In contrast, only six of their male partners had eczema during the pregnancy time frame, and just one of them had new-onset eczema.

A history of maternal eczema in the preceding generation was associated with a 52% increased relative risk of having eczema by age 18 and a 3.1-fold increased likelihood of eczema during pregnancy. Also, methylation of the filaggrin gene at the cytosine-phosphate-guanine site cg13447818 when assessed at age 18 was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of eczema in a subject’s mother as well as increased risk of gestational eczema 1-7 years later, Dr. Karmaus continued.

Eighteen percent of women in the Isle of Wight cohort had asthma during pregnancy, as did a similar proportion of their male partners. Twenty-seven percent of women with asthma during pregnancy had no previous history of the respiratory disease, a rate which was again comparable in their male partners with asthma.

DNA methylation of the IL1RL1 gene at cg17738684 was significantly associated with asthma heritability across three generations in the Isle of Wight study. The IL1RL1 gene at cg17738684 is a candidate gene for asthma that encodes for interleukin-33. This finding raises the possibility that addressing this DNA methylation could prove fruitful as a transgenerational asthma prevention strategy.

The Isle of Wight birth cohort study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Asthma UK, and the Isle of Wight Trust. Dr. Karmaus reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

HOUSTON– New-onset eczema during pregnancy is a common phenomenon with several newly identified risk factors.

This disease entity deserves a proper name: gestational eczema, Dr. Wilfried J.J. Karmaus asserted at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

In contrast, the likelihood of new-onset asthma arising during pregnancy isn’t significantly more common than in an affected woman’s male partner during the same time frame.

“There was no large difference in wheezing between the women and men. Therefore, we cannot propose the term ‘gestational asthma,’” said Dr. Karmaus, professor of epidemiology at the University of Memphis. “Investigations into how to prevent eczema and asthma in pregnancy are really important, because eczema and asthma in pregnancy can increase the risk of these diseases in the offspring. This is a totally undeveloped field.”

He presented new findings from the Isle of Wight study, a prospective study in which a cohort of women has been followed from birth through pregnancy across three generations.

Eczema and asthma are common atopic diseases, and they are particularly common during pregnancy. Indeed, eczema is the most common skin disease seen in pregnancy, accounting for 35%-50% of all dermatoses in previous studies by other investigators. In those studies, only 20%-40% of women with eczema during pregnancy had a prepregnancy history of the disease.

In the Isle of Wight cohort, women were evaluated for asthma and eczema symptoms at ages 1, 2, 4, 10, and 18 years and again during pregnancy at gestational weeks 20 and 28. A total of 26 of 116 women developed eczema during pregnancy, with eight of them (31%) experiencing the skin disease for the first time in their lives. In contrast, only six of their male partners had eczema during the pregnancy time frame, and just one of them had new-onset eczema.

A history of maternal eczema in the preceding generation was associated with a 52% increased relative risk of having eczema by age 18 and a 3.1-fold increased likelihood of eczema during pregnancy. Also, methylation of the filaggrin gene at the cytosine-phosphate-guanine site cg13447818 when assessed at age 18 was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of eczema in a subject’s mother as well as increased risk of gestational eczema 1-7 years later, Dr. Karmaus continued.

Eighteen percent of women in the Isle of Wight cohort had asthma during pregnancy, as did a similar proportion of their male partners. Twenty-seven percent of women with asthma during pregnancy had no previous history of the respiratory disease, a rate which was again comparable in their male partners with asthma.

DNA methylation of the IL1RL1 gene at cg17738684 was significantly associated with asthma heritability across three generations in the Isle of Wight study. The IL1RL1 gene at cg17738684 is a candidate gene for asthma that encodes for interleukin-33. This finding raises the possibility that addressing this DNA methylation could prove fruitful as a transgenerational asthma prevention strategy.

The Isle of Wight birth cohort study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Asthma UK, and the Isle of Wight Trust. Dr. Karmaus reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Thirty-one percent of cases of eczema and 27% of asthma in a group of pregnant women occurred for the first time in the woman’s life.

Major finding: A history of maternal eczema was associated with a 3.1-fold increased likelihood of eczema during the offspring’s pregnancy.

Data source: The Isle of Wight birth cohort study is a prospective study following three generations from birth through pregnancy.

Disclosures: The study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, Asthma UK, and the Isle of Wight Trust. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Pregnancy in the cancer survivor

Obstetric providers are being called upon to care for an increasing number of cancer survivors. Whether it was a childhood cancer or one faced in early adulthood, pregnant cancer survivors raise a unique set of questions and concerns. A general knowledge about management is essential in counseling these women prior to and early in pregnancy.

For the woman who presents preconception, one of the most common questions is when is the best time for pregnancy. Importantly, there are no absolute guidelines on how long a woman should be “disease free.” Many providers suggest waiting 2 years from the time of diagnosis. This “conventional wisdom” is not based on evidence (Oncology 2005;19:693-7). Instead, the type of cancer and the length of treatment can help determine the answer.

Many oncologists prefer a specific time for monitoring after treatment to ensure that initial treatment has been successful. For example, in the case of melanoma, after 2 years, the estimate of recurrence risk may be more accurate (Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:437-42). After breast cancer, women are often followed with MRI with contrast and mammogram. Since both are problematic in pregnancy, 3-5 years may be more appropriate.

Many patients are concerned about the risk of recurrence during pregnancy. Though data are limited, pregnancy does not appear to increase the risk of disease recurrence or decrease disease-free survival, even in the case of more aggressive cancers such as melanoma. This remains true in the setting of hormone receptor–positive cancers, specifically breast cancer (Lancet 1997;350:319-22).

Preconception counseling

The risks for a cancer survivor during pregnancy will vary depending on the treatments she has received. Preconception evaluation should be modified for the specific oncologic therapies. For example, women who received chest radiation, or anthracycline-based chemotherapies (or any cardiotoxic medications) should have a cardiac evaluation as they are at risk of cardiac dysfunction prior to and during pregnancy (Matern. Child. Health J. 2006;10[suppl. 1]:165-8).

Additionally, because chemotherapy may be hepatotoxic or nephrotoxic, baseline liver and renal function tests should almost always be performed. It is not unreasonable to follow these during pregnancy given the physiologic changes.

Many women also are concerned about the risks that prior cancer therapies may have for their baby. Prior chemotherapy and radiation therapy do not appear to confer any increased risk for genetic conditions, anomalies, or childhood cancer (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;187:1070-80). Additionally, previous chemotherapy alone does not increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In contrast, prior radiation to the abdomen and pelvis has been associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, growth restriction, preterm delivery, and stillbirth (J. Natl. Cancer Instit. Monogr. 2005;34:64-8; Lancet 2010;376:624-30). There is an increased risk of cancer in the offspring of women whose cancer is the result of hereditary cancer syndromes, such as BRCA or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Discussions with a genetics counselor may be helpful if there are any questions related to these syndromes.

Pregnancy management

Once pregnant, management requires a multidisciplinary approach. Surveillance options are limited during pregnancy. CT should be avoided, and radiographs limited. Ultrasound of the abdomen is safe, but optimal images are often obscured in later trimesters. Ultimately, indicated imaging should not be forsaken if there are any signs or symptoms that raise concerns for recurrence. Additionally, many tumor markers may be unreliable during pregnancy, such as CA-125 in the first trimester, or alpha-FP and CEA anytime.

Specific recommendations for antenatal testing do not exist and should be assessed on a case-by-case basis; especially in the case of women who have had prior radiation therapy. Our recommendation is to perform growth surveillance, which may include sonography at varying intervals. Also consider weekly fetal testing from 32 weeks in normally growing fetuses.

Solely being a cancer survivor is not an indication for early delivery or induction of labor. In the majority of cases, mode of delivery should be guided by obstetric indications, though previous pelvic surgery and reconstruction may be indications for cesarean delivery. Despite being in remission, some cancers metastasize to the placenta, most commonly melanoma and hematologic cancers. Very rarely, these cancers can also metastasize to the fetus. Thus, the placenta should be sent for histologic evaluation, with a notation to the pathologist about the patient’s prior cancer (Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1989;44:535-40; Ultrasound. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;33:235-44).

In most cases, pregnancy after cancer is uncomplicated with good outcomes for both mother and baby. However, there are potential medical and obstetric complications that cannot be overlooked. Interdisciplinary management is crucial to ensure a safe transition from cancer survivor to mother.

What to consider when counseling cancer survivors about pregnancy

• The recommended disease-free interval prior to pregnancy may vary by cancer type, and is largely driven by disease surveillance needs and recurrence intervals.

• Prior cancer, associated operations, and chemotherapies do not typically confer additional risks in pregnancy. Exceptions include melanoma and blood cell cancers, which may metastasize to the placenta and fetus, even following periods of remission.

• Radiation therapy to the abdomen and pelvis may induce changes that predispose to growth restriction, preterm birth, and stillbirth. Enhanced surveillance may be reasonable in these cases.

• Preconception or early pregnancy assessment for end organ dysfunction is recommended for women who have received certain therapies: cardiac evaluation following chest radiation or anthracycline-based therapy; liver and kidney function for most chemotherapies.

Dr. Ivester is an associate professor of maternal-fetal medicine and an associate professor of maternal and child health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Dotters-Katz is a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who completed her ob.gyn. residency at Duke University. Her academic interests include oncology and infectious diseases as they relate to pregnancy. The authors reported having no financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

Obstetric providers are being called upon to care for an increasing number of cancer survivors. Whether it was a childhood cancer or one faced in early adulthood, pregnant cancer survivors raise a unique set of questions and concerns. A general knowledge about management is essential in counseling these women prior to and early in pregnancy.

For the woman who presents preconception, one of the most common questions is when is the best time for pregnancy. Importantly, there are no absolute guidelines on how long a woman should be “disease free.” Many providers suggest waiting 2 years from the time of diagnosis. This “conventional wisdom” is not based on evidence (Oncology 2005;19:693-7). Instead, the type of cancer and the length of treatment can help determine the answer.

Many oncologists prefer a specific time for monitoring after treatment to ensure that initial treatment has been successful. For example, in the case of melanoma, after 2 years, the estimate of recurrence risk may be more accurate (Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:437-42). After breast cancer, women are often followed with MRI with contrast and mammogram. Since both are problematic in pregnancy, 3-5 years may be more appropriate.

Many patients are concerned about the risk of recurrence during pregnancy. Though data are limited, pregnancy does not appear to increase the risk of disease recurrence or decrease disease-free survival, even in the case of more aggressive cancers such as melanoma. This remains true in the setting of hormone receptor–positive cancers, specifically breast cancer (Lancet 1997;350:319-22).

Preconception counseling

The risks for a cancer survivor during pregnancy will vary depending on the treatments she has received. Preconception evaluation should be modified for the specific oncologic therapies. For example, women who received chest radiation, or anthracycline-based chemotherapies (or any cardiotoxic medications) should have a cardiac evaluation as they are at risk of cardiac dysfunction prior to and during pregnancy (Matern. Child. Health J. 2006;10[suppl. 1]:165-8).

Additionally, because chemotherapy may be hepatotoxic or nephrotoxic, baseline liver and renal function tests should almost always be performed. It is not unreasonable to follow these during pregnancy given the physiologic changes.

Many women also are concerned about the risks that prior cancer therapies may have for their baby. Prior chemotherapy and radiation therapy do not appear to confer any increased risk for genetic conditions, anomalies, or childhood cancer (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;187:1070-80). Additionally, previous chemotherapy alone does not increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In contrast, prior radiation to the abdomen and pelvis has been associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, growth restriction, preterm delivery, and stillbirth (J. Natl. Cancer Instit. Monogr. 2005;34:64-8; Lancet 2010;376:624-30). There is an increased risk of cancer in the offspring of women whose cancer is the result of hereditary cancer syndromes, such as BRCA or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Discussions with a genetics counselor may be helpful if there are any questions related to these syndromes.

Pregnancy management

Once pregnant, management requires a multidisciplinary approach. Surveillance options are limited during pregnancy. CT should be avoided, and radiographs limited. Ultrasound of the abdomen is safe, but optimal images are often obscured in later trimesters. Ultimately, indicated imaging should not be forsaken if there are any signs or symptoms that raise concerns for recurrence. Additionally, many tumor markers may be unreliable during pregnancy, such as CA-125 in the first trimester, or alpha-FP and CEA anytime.

Specific recommendations for antenatal testing do not exist and should be assessed on a case-by-case basis; especially in the case of women who have had prior radiation therapy. Our recommendation is to perform growth surveillance, which may include sonography at varying intervals. Also consider weekly fetal testing from 32 weeks in normally growing fetuses.

Solely being a cancer survivor is not an indication for early delivery or induction of labor. In the majority of cases, mode of delivery should be guided by obstetric indications, though previous pelvic surgery and reconstruction may be indications for cesarean delivery. Despite being in remission, some cancers metastasize to the placenta, most commonly melanoma and hematologic cancers. Very rarely, these cancers can also metastasize to the fetus. Thus, the placenta should be sent for histologic evaluation, with a notation to the pathologist about the patient’s prior cancer (Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1989;44:535-40; Ultrasound. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;33:235-44).

In most cases, pregnancy after cancer is uncomplicated with good outcomes for both mother and baby. However, there are potential medical and obstetric complications that cannot be overlooked. Interdisciplinary management is crucial to ensure a safe transition from cancer survivor to mother.

What to consider when counseling cancer survivors about pregnancy

• The recommended disease-free interval prior to pregnancy may vary by cancer type, and is largely driven by disease surveillance needs and recurrence intervals.

• Prior cancer, associated operations, and chemotherapies do not typically confer additional risks in pregnancy. Exceptions include melanoma and blood cell cancers, which may metastasize to the placenta and fetus, even following periods of remission.

• Radiation therapy to the abdomen and pelvis may induce changes that predispose to growth restriction, preterm birth, and stillbirth. Enhanced surveillance may be reasonable in these cases.

• Preconception or early pregnancy assessment for end organ dysfunction is recommended for women who have received certain therapies: cardiac evaluation following chest radiation or anthracycline-based therapy; liver and kidney function for most chemotherapies.

Dr. Ivester is an associate professor of maternal-fetal medicine and an associate professor of maternal and child health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Dotters-Katz is a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who completed her ob.gyn. residency at Duke University. Her academic interests include oncology and infectious diseases as they relate to pregnancy. The authors reported having no financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

Obstetric providers are being called upon to care for an increasing number of cancer survivors. Whether it was a childhood cancer or one faced in early adulthood, pregnant cancer survivors raise a unique set of questions and concerns. A general knowledge about management is essential in counseling these women prior to and early in pregnancy.

For the woman who presents preconception, one of the most common questions is when is the best time for pregnancy. Importantly, there are no absolute guidelines on how long a woman should be “disease free.” Many providers suggest waiting 2 years from the time of diagnosis. This “conventional wisdom” is not based on evidence (Oncology 2005;19:693-7). Instead, the type of cancer and the length of treatment can help determine the answer.

Many oncologists prefer a specific time for monitoring after treatment to ensure that initial treatment has been successful. For example, in the case of melanoma, after 2 years, the estimate of recurrence risk may be more accurate (Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:437-42). After breast cancer, women are often followed with MRI with contrast and mammogram. Since both are problematic in pregnancy, 3-5 years may be more appropriate.

Many patients are concerned about the risk of recurrence during pregnancy. Though data are limited, pregnancy does not appear to increase the risk of disease recurrence or decrease disease-free survival, even in the case of more aggressive cancers such as melanoma. This remains true in the setting of hormone receptor–positive cancers, specifically breast cancer (Lancet 1997;350:319-22).

Preconception counseling

The risks for a cancer survivor during pregnancy will vary depending on the treatments she has received. Preconception evaluation should be modified for the specific oncologic therapies. For example, women who received chest radiation, or anthracycline-based chemotherapies (or any cardiotoxic medications) should have a cardiac evaluation as they are at risk of cardiac dysfunction prior to and during pregnancy (Matern. Child. Health J. 2006;10[suppl. 1]:165-8).

Additionally, because chemotherapy may be hepatotoxic or nephrotoxic, baseline liver and renal function tests should almost always be performed. It is not unreasonable to follow these during pregnancy given the physiologic changes.

Many women also are concerned about the risks that prior cancer therapies may have for their baby. Prior chemotherapy and radiation therapy do not appear to confer any increased risk for genetic conditions, anomalies, or childhood cancer (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;187:1070-80). Additionally, previous chemotherapy alone does not increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In contrast, prior radiation to the abdomen and pelvis has been associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, growth restriction, preterm delivery, and stillbirth (J. Natl. Cancer Instit. Monogr. 2005;34:64-8; Lancet 2010;376:624-30). There is an increased risk of cancer in the offspring of women whose cancer is the result of hereditary cancer syndromes, such as BRCA or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Discussions with a genetics counselor may be helpful if there are any questions related to these syndromes.

Pregnancy management

Once pregnant, management requires a multidisciplinary approach. Surveillance options are limited during pregnancy. CT should be avoided, and radiographs limited. Ultrasound of the abdomen is safe, but optimal images are often obscured in later trimesters. Ultimately, indicated imaging should not be forsaken if there are any signs or symptoms that raise concerns for recurrence. Additionally, many tumor markers may be unreliable during pregnancy, such as CA-125 in the first trimester, or alpha-FP and CEA anytime.

Specific recommendations for antenatal testing do not exist and should be assessed on a case-by-case basis; especially in the case of women who have had prior radiation therapy. Our recommendation is to perform growth surveillance, which may include sonography at varying intervals. Also consider weekly fetal testing from 32 weeks in normally growing fetuses.

Solely being a cancer survivor is not an indication for early delivery or induction of labor. In the majority of cases, mode of delivery should be guided by obstetric indications, though previous pelvic surgery and reconstruction may be indications for cesarean delivery. Despite being in remission, some cancers metastasize to the placenta, most commonly melanoma and hematologic cancers. Very rarely, these cancers can also metastasize to the fetus. Thus, the placenta should be sent for histologic evaluation, with a notation to the pathologist about the patient’s prior cancer (Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1989;44:535-40; Ultrasound. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;33:235-44).

In most cases, pregnancy after cancer is uncomplicated with good outcomes for both mother and baby. However, there are potential medical and obstetric complications that cannot be overlooked. Interdisciplinary management is crucial to ensure a safe transition from cancer survivor to mother.

What to consider when counseling cancer survivors about pregnancy

• The recommended disease-free interval prior to pregnancy may vary by cancer type, and is largely driven by disease surveillance needs and recurrence intervals.

• Prior cancer, associated operations, and chemotherapies do not typically confer additional risks in pregnancy. Exceptions include melanoma and blood cell cancers, which may metastasize to the placenta and fetus, even following periods of remission.

• Radiation therapy to the abdomen and pelvis may induce changes that predispose to growth restriction, preterm birth, and stillbirth. Enhanced surveillance may be reasonable in these cases.

• Preconception or early pregnancy assessment for end organ dysfunction is recommended for women who have received certain therapies: cardiac evaluation following chest radiation or anthracycline-based therapy; liver and kidney function for most chemotherapies.

Dr. Ivester is an associate professor of maternal-fetal medicine and an associate professor of maternal and child health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Dotters-Katz is a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who completed her ob.gyn. residency at Duke University. Her academic interests include oncology and infectious diseases as they relate to pregnancy. The authors reported having no financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

CDC: Nearly one-third of women have short birth spacing

In 2011, nearly 30% of women who gave birth to single infants had an interval of less than 18 months between the conception of their most recent pregnancy and the birth of their previous child, potentially putting them at risk for pregnancy complications.

The findings, released April 16, come from a new report from researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who analyzed birth certificate data covering 1,723,084 women who had singleton births in 2011. In addition to women with short birth intervals, the report found that nearly 21% of women had birth intervals of 60 months or longer, which is also associated with a higher risk for adverse health outcomes, the researchers wrote (National Vital Statistics Report 2015;64:1-10).

About half of women had an interval of 18-59 months between the birth of one child and the conception of the next child, the researchers found.

Age and race had an impact on the birth interval, according to the birth certificate data. The median interpregnancy interval increased along with the age of the mother. For instance, the median interpregnancy interval was 11-14 months for women under age 20 years, but it was 39-76 months for women aged 40 years and older. Non-Hispanic white women had the shortest median interpregnancy interval at 26 months. This is compared with 30 months for non-Hispanic black women and 34 months for Hispanic women.

The birth certificate data used in the study, from 36 states and the District of Columbia, is not nationally representative and may not be generalizable across the United States, but the researchers pointed out that the percentages of women with short and long pregnancy intervals were similar to pregnancy data from the 2006-2010 National Survey on Family Growth.

The researchers called for further studies to assess whether pregnancy intervals are “independently associated with adverse maternal and infant health outcomes or whether these relationships are due to other confounding factors” such as maternal age, socioeconomic status, and pregnancy health behaviors.

Find the full study here.

In 2011, nearly 30% of women who gave birth to single infants had an interval of less than 18 months between the conception of their most recent pregnancy and the birth of their previous child, potentially putting them at risk for pregnancy complications.

The findings, released April 16, come from a new report from researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who analyzed birth certificate data covering 1,723,084 women who had singleton births in 2011. In addition to women with short birth intervals, the report found that nearly 21% of women had birth intervals of 60 months or longer, which is also associated with a higher risk for adverse health outcomes, the researchers wrote (National Vital Statistics Report 2015;64:1-10).

About half of women had an interval of 18-59 months between the birth of one child and the conception of the next child, the researchers found.

Age and race had an impact on the birth interval, according to the birth certificate data. The median interpregnancy interval increased along with the age of the mother. For instance, the median interpregnancy interval was 11-14 months for women under age 20 years, but it was 39-76 months for women aged 40 years and older. Non-Hispanic white women had the shortest median interpregnancy interval at 26 months. This is compared with 30 months for non-Hispanic black women and 34 months for Hispanic women.

The birth certificate data used in the study, from 36 states and the District of Columbia, is not nationally representative and may not be generalizable across the United States, but the researchers pointed out that the percentages of women with short and long pregnancy intervals were similar to pregnancy data from the 2006-2010 National Survey on Family Growth.

The researchers called for further studies to assess whether pregnancy intervals are “independently associated with adverse maternal and infant health outcomes or whether these relationships are due to other confounding factors” such as maternal age, socioeconomic status, and pregnancy health behaviors.

Find the full study here.

In 2011, nearly 30% of women who gave birth to single infants had an interval of less than 18 months between the conception of their most recent pregnancy and the birth of their previous child, potentially putting them at risk for pregnancy complications.

The findings, released April 16, come from a new report from researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who analyzed birth certificate data covering 1,723,084 women who had singleton births in 2011. In addition to women with short birth intervals, the report found that nearly 21% of women had birth intervals of 60 months or longer, which is also associated with a higher risk for adverse health outcomes, the researchers wrote (National Vital Statistics Report 2015;64:1-10).

About half of women had an interval of 18-59 months between the birth of one child and the conception of the next child, the researchers found.

Age and race had an impact on the birth interval, according to the birth certificate data. The median interpregnancy interval increased along with the age of the mother. For instance, the median interpregnancy interval was 11-14 months for women under age 20 years, but it was 39-76 months for women aged 40 years and older. Non-Hispanic white women had the shortest median interpregnancy interval at 26 months. This is compared with 30 months for non-Hispanic black women and 34 months for Hispanic women.

The birth certificate data used in the study, from 36 states and the District of Columbia, is not nationally representative and may not be generalizable across the United States, but the researchers pointed out that the percentages of women with short and long pregnancy intervals were similar to pregnancy data from the 2006-2010 National Survey on Family Growth.

The researchers called for further studies to assess whether pregnancy intervals are “independently associated with adverse maternal and infant health outcomes or whether these relationships are due to other confounding factors” such as maternal age, socioeconomic status, and pregnancy health behaviors.

Find the full study here.

Different risks for two oral antidiabetics in GDM

Metformin and glyburide are both as effective as insulin in the management of gestational diabetes, a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials has found, though their risk profiles differ.

The investigators looked at 18 trials comparing the two oral agents with insulin, and in some cases with each other, in about 2,800 women with gestational diabetes.

The study showed significant differences among the oral drugs and insulin in maternal fasting blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin levels, suggesting that all are effective in controlling GDM, according to Dr. Yun-fa Jiang of Hebei Medical University in Shijiazhuang, China, and associates (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. [doi:10.1210/jc.2014-4403]).

However, compared with insulin, metformin was associated with lower maternal weight gain (weighted mean difference: –1.49 kg; 95% confidence interval, –2.26 to 0.31), and shorter gestational age (WMD, –0.16 kg/week; 95% CI, –0.30 to –0.03). Glyburide was associated with higher neonatal birth weight (130.68 g; 95% CI, 55.98 to 205.38), neonatal hypoglycemia (odds ratio, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.59 to 4.38), and increased incidence of macrosomia (OR, 3.09; 95% CI, 1.59 to 6.04) compared with insulin. In a network meta-analysis, metformin was seen associated with significantly less maternal weight gain, compared with glyburide (WMD, –1.34; 95% CI, –3.05 to 0.38; P = .009).

The differences might be attributable to different mechanisms of action in the two oral drugs, according to the investigators, who noted that this was the first network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of oral antidiabetics in management of gestational diabetes. “There exists some apprehension regarding the use of oral antidiabetic drugs during pregnancy,” they wrote. “While no long-term harms to the exposed offspring from either of these drugs have been demonstrated, no long-term studies have been performed with appropriate controls, either in humans or animal models.”

Dr. Jiang and colleagues noted among the weaknesses of their study the relatively few trials included, and that blinding was not possible in trials that compared oral agents with insulin therapy.

The study was funded by China’s National Science Foundation and none of its authors declared conflicts of interest.

Metformin and glyburide are both as effective as insulin in the management of gestational diabetes, a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials has found, though their risk profiles differ.

The investigators looked at 18 trials comparing the two oral agents with insulin, and in some cases with each other, in about 2,800 women with gestational diabetes.

The study showed significant differences among the oral drugs and insulin in maternal fasting blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin levels, suggesting that all are effective in controlling GDM, according to Dr. Yun-fa Jiang of Hebei Medical University in Shijiazhuang, China, and associates (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. [doi:10.1210/jc.2014-4403]).

However, compared with insulin, metformin was associated with lower maternal weight gain (weighted mean difference: –1.49 kg; 95% confidence interval, –2.26 to 0.31), and shorter gestational age (WMD, –0.16 kg/week; 95% CI, –0.30 to –0.03). Glyburide was associated with higher neonatal birth weight (130.68 g; 95% CI, 55.98 to 205.38), neonatal hypoglycemia (odds ratio, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.59 to 4.38), and increased incidence of macrosomia (OR, 3.09; 95% CI, 1.59 to 6.04) compared with insulin. In a network meta-analysis, metformin was seen associated with significantly less maternal weight gain, compared with glyburide (WMD, –1.34; 95% CI, –3.05 to 0.38; P = .009).

The differences might be attributable to different mechanisms of action in the two oral drugs, according to the investigators, who noted that this was the first network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of oral antidiabetics in management of gestational diabetes. “There exists some apprehension regarding the use of oral antidiabetic drugs during pregnancy,” they wrote. “While no long-term harms to the exposed offspring from either of these drugs have been demonstrated, no long-term studies have been performed with appropriate controls, either in humans or animal models.”

Dr. Jiang and colleagues noted among the weaknesses of their study the relatively few trials included, and that blinding was not possible in trials that compared oral agents with insulin therapy.

The study was funded by China’s National Science Foundation and none of its authors declared conflicts of interest.

Metformin and glyburide are both as effective as insulin in the management of gestational diabetes, a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials has found, though their risk profiles differ.

The investigators looked at 18 trials comparing the two oral agents with insulin, and in some cases with each other, in about 2,800 women with gestational diabetes.

The study showed significant differences among the oral drugs and insulin in maternal fasting blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin levels, suggesting that all are effective in controlling GDM, according to Dr. Yun-fa Jiang of Hebei Medical University in Shijiazhuang, China, and associates (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. [doi:10.1210/jc.2014-4403]).

However, compared with insulin, metformin was associated with lower maternal weight gain (weighted mean difference: –1.49 kg; 95% confidence interval, –2.26 to 0.31), and shorter gestational age (WMD, –0.16 kg/week; 95% CI, –0.30 to –0.03). Glyburide was associated with higher neonatal birth weight (130.68 g; 95% CI, 55.98 to 205.38), neonatal hypoglycemia (odds ratio, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.59 to 4.38), and increased incidence of macrosomia (OR, 3.09; 95% CI, 1.59 to 6.04) compared with insulin. In a network meta-analysis, metformin was seen associated with significantly less maternal weight gain, compared with glyburide (WMD, –1.34; 95% CI, –3.05 to 0.38; P = .009).

The differences might be attributable to different mechanisms of action in the two oral drugs, according to the investigators, who noted that this was the first network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of oral antidiabetics in management of gestational diabetes. “There exists some apprehension regarding the use of oral antidiabetic drugs during pregnancy,” they wrote. “While no long-term harms to the exposed offspring from either of these drugs have been demonstrated, no long-term studies have been performed with appropriate controls, either in humans or animal models.”

Dr. Jiang and colleagues noted among the weaknesses of their study the relatively few trials included, and that blinding was not possible in trials that compared oral agents with insulin therapy.

The study was funded by China’s National Science Foundation and none of its authors declared conflicts of interest.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Key clinical point: The risks of using glyburide in treatment of gestational diabetes are significant.

Major finding: Treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus with glyburide is associated with increased risk of neonatal hypoglycemia, high maternal weight gain, high neonatal birth weight, and macrosomia compared to standard treatment with insulin, while metformin was not seen associated with these.

Data source: A network meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials enrolling about 2800 patients with GDM in several countries, including Brazil, the United States, and India; trials occurred between 2000 and 2013

Disclosures: The study was funded by China’s National Science Foundation and none of its authors declared conflicts of interest.

Neonatal and teen maternal hospital admissions falling

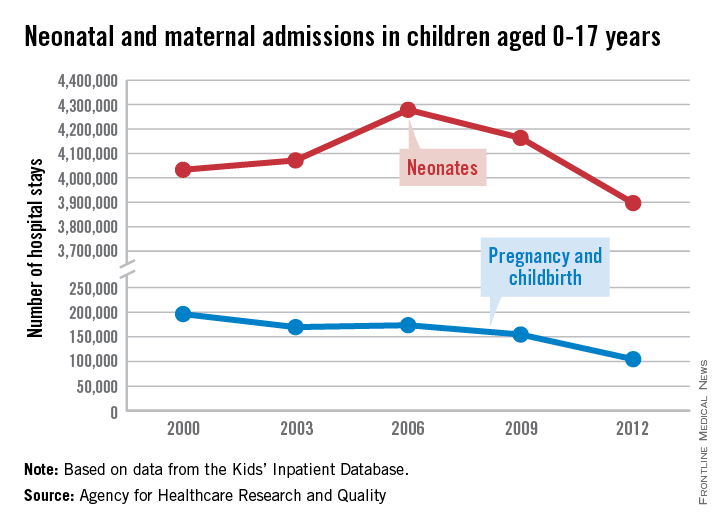

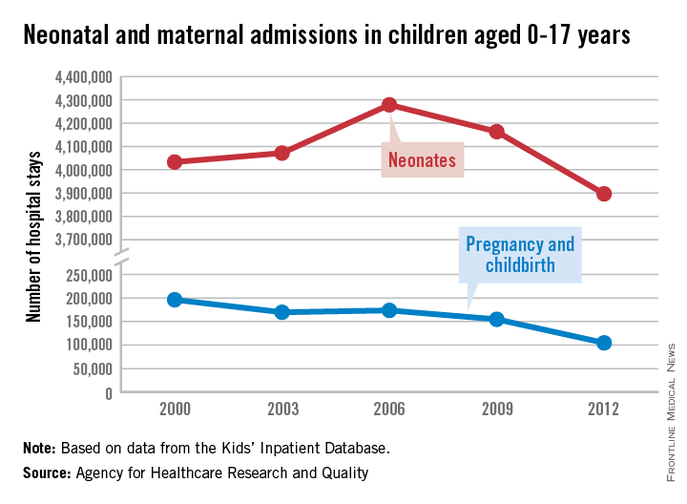

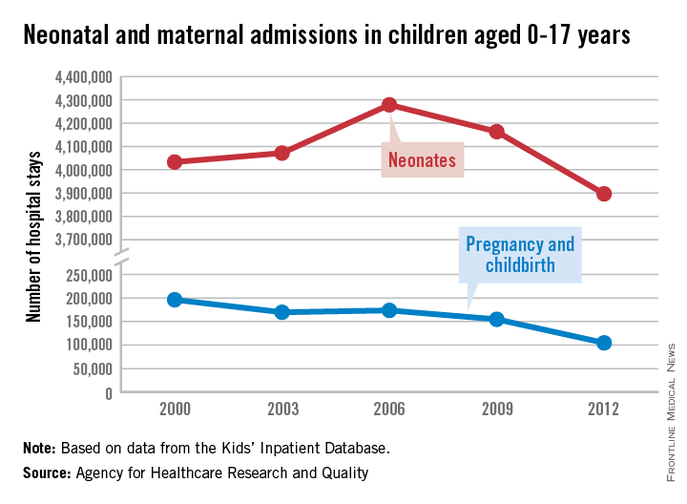

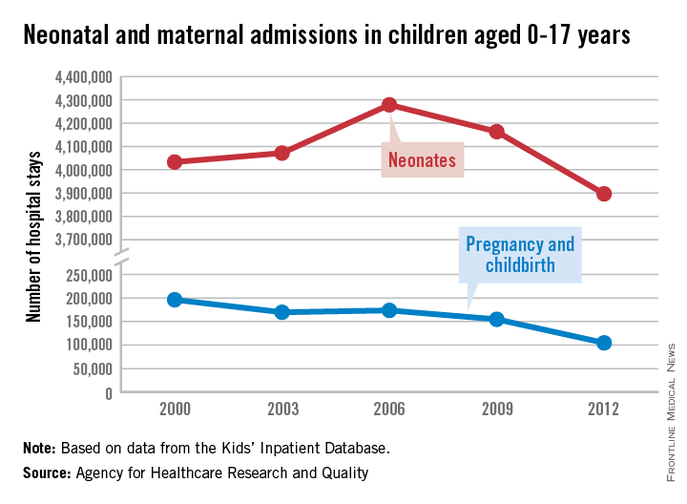

The number of neonatal and maternal hospitalizations in children less than 18 years old fell from 2000 to 2012, with maternal hospital stays in teenagers dropping significantly, according to a report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

From 2000 to 2006, the number of neonatal hospitalizations increased by about 250,000, rising from slightly more than 4 million to just under 4.3 million. From 2006 to 2012, the number dropped significantly, dipping below the 2000 level to about 3.9 million. Overall, neonatal hospitalizations fell by about 140,000 from 2000 to 2012, or 3.3%, the AHRQ reported.

Maternal hospital stays for teenage girls dropped significantly from 2000 to 2012, despite a small rise from 2003 to 2006. There were just over 196,000 maternal hospitalizations in 2000, but by 2012, the number fell to less than 105,000, a decrease of about 47%. More than half of the decrease occurred in the last 3 years measured, with maternal hospitalizations falling by 50,000 from 2009 to 2012.

There were 5.85 million total hospitalizations in 2012 of children under 18 years. Of these, about two-thirds were neonatal related, while maternal hospitalizations accounted for less than 2% of the total, according to the AHRQ.

The AHRQ report used data collected by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient Database.

The number of neonatal and maternal hospitalizations in children less than 18 years old fell from 2000 to 2012, with maternal hospital stays in teenagers dropping significantly, according to a report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

From 2000 to 2006, the number of neonatal hospitalizations increased by about 250,000, rising from slightly more than 4 million to just under 4.3 million. From 2006 to 2012, the number dropped significantly, dipping below the 2000 level to about 3.9 million. Overall, neonatal hospitalizations fell by about 140,000 from 2000 to 2012, or 3.3%, the AHRQ reported.

Maternal hospital stays for teenage girls dropped significantly from 2000 to 2012, despite a small rise from 2003 to 2006. There were just over 196,000 maternal hospitalizations in 2000, but by 2012, the number fell to less than 105,000, a decrease of about 47%. More than half of the decrease occurred in the last 3 years measured, with maternal hospitalizations falling by 50,000 from 2009 to 2012.

There were 5.85 million total hospitalizations in 2012 of children under 18 years. Of these, about two-thirds were neonatal related, while maternal hospitalizations accounted for less than 2% of the total, according to the AHRQ.

The AHRQ report used data collected by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient Database.

The number of neonatal and maternal hospitalizations in children less than 18 years old fell from 2000 to 2012, with maternal hospital stays in teenagers dropping significantly, according to a report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

From 2000 to 2006, the number of neonatal hospitalizations increased by about 250,000, rising from slightly more than 4 million to just under 4.3 million. From 2006 to 2012, the number dropped significantly, dipping below the 2000 level to about 3.9 million. Overall, neonatal hospitalizations fell by about 140,000 from 2000 to 2012, or 3.3%, the AHRQ reported.

Maternal hospital stays for teenage girls dropped significantly from 2000 to 2012, despite a small rise from 2003 to 2006. There were just over 196,000 maternal hospitalizations in 2000, but by 2012, the number fell to less than 105,000, a decrease of about 47%. More than half of the decrease occurred in the last 3 years measured, with maternal hospitalizations falling by 50,000 from 2009 to 2012.

There were 5.85 million total hospitalizations in 2012 of children under 18 years. Of these, about two-thirds were neonatal related, while maternal hospitalizations accounted for less than 2% of the total, according to the AHRQ.

The AHRQ report used data collected by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient Database.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome risk varies with modifiable factors

Infants born to women taking prescription opioids were more likely to have neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) if their mothers smoked tobacco or took selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to a recent study. Cumulative opioid exposure and opioid type (maintenance and long-acting) also increased the risk of NAS.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all opioid-exposed infants be observed in the hospital for 4 to 7 days after birth. However, our data suggest there was a wide variability in an infant’s risk of drug withdrawal based on opioid type, dose, SSRI use, and number of cigarettes smoked per day by the mother,” reported Dr. Stephen W. Patrick of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “Future studies should evaluate new care models for opioid-exposed infants at different risk levels of developing NAS,” wrote Dr. Patrick and his associates [Pediatrics 2015 April 13 [doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3299]).

Dr. Patrick’s team analyzed prescription data and vital statistics of 112,029 pregnant women and their newborns who were enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program between 2009 and 2011. Of these, 28% of the women filled at least one prescription for opioids; these included 96.2% taking short-acting medications, 2.7% receiving maintenance treatment for substance use disorders and 0.6% taking long-acting medications.

Among women taking prescription opioids, 5.3% had depression, 4.3% had an anxiety disorder, 41.8% smoked, 4.3% had been prescribed SSRIs within 30 days before birth, 8.3% had headache or migraine, and 23.7% had musculoskeletal disease, compared to 2.7%, 1.6% and 25.8%, 1.9%, 2.0% and 5.8%, respectively, for mothers not taking opioids.

Nearly a third of women on maintenance therapy (29.3%) had infants with NAS while 14.7% of mothers taking long-acting opioids and 1.4% of women taking short-acting preparations had newborns with NAS. Newborns were twice as likely to develop NAS if their mothers took SSRIs (odds ratio, 2.08), and their risk of NAS increased in a dose-response fashion with the number of daily cigarettes their mothers smoked.

NAS rates nearly doubled during the course of the study, landing at 10.7 per 1,000 births in the final year. Among the 1,086 newborns diagnosed with NAS, 21.2% had low birth weight, 16.7% were preterm, 28.7% had respiratory diagnoses, 13.1% had feeding difficulties, 7.2% had sepsis, and 3.7% had seizures. Among those exposed to opioids who did not develop NAS, 11.8% had low birth weight, 11.6% were preterm, 10.1% had respiratory diagnoses, 2.6% had feeding difficulties, 2.3% had sepsis and 0.4% had seizures. Among unexposed newborns, 9.9% had low birth weight, 11% were preterm, 8.8% had respiratory diagnoses, 2.3% had feeding difficulties, 1.9% had sepsis, and 0.3% had seizures.

“Public health efforts should focus on limiting inappropriate [opioid pain relievers] and tobacco use in pregnancy,” the authors wrote. “Prescribing opioids in pregnancy should be done with caution because it can lead to significant complications for the neonate.”

The research was funded by the Tennessee Department of Health and the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no disclosures.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome is a rapidly growing problem, increasing 16-fold in Tennessee in 13 years. At a rate of 12 cases per 1,000 births in 2013, the incidence is now 10 times more likely than group B strep sepsis, congenital deafness, or dislocated hips, and many times more likely than a bilirubin of 20. So screening for it must become standard newborn care.

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics 2012 guidelines (Pediatrics 2012;129:e540-60) noted that 45-87 out of 1,000 mothers are using illicit drugs during pregnancy, this new study indicates that use of prescription opioids during pregnancy has been increasing and is associated with this rise in NAS. The use of any opioids during pregnancy (28%) now matches the rate of any alcohol (23.7%) and tobacco use (27.7%). Chronic users of opioids are fewer in number, but much more likely to yield withdrawal in the neonate.

The article identifies cofactors (cigarette and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use) that increase the likelihood of a given amount of maternal opiate use leading to clinical NAS. So the use of those substances should be solicited in history along with the types, frequency, and duration of any opioid use. It would be ideal if this information was collected during the obstetric admission process along with maternal blood type, group B strep status, hepatitis B, and other labs. Observation for signs of withdrawal deserves as much attention as that paid to getting the hearing screen done and the bilirubin checked. It is harming more newborns.

Kevin T. Powell, M.D., Ph.D., is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome is a rapidly growing problem, increasing 16-fold in Tennessee in 13 years. At a rate of 12 cases per 1,000 births in 2013, the incidence is now 10 times more likely than group B strep sepsis, congenital deafness, or dislocated hips, and many times more likely than a bilirubin of 20. So screening for it must become standard newborn care.

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics 2012 guidelines (Pediatrics 2012;129:e540-60) noted that 45-87 out of 1,000 mothers are using illicit drugs during pregnancy, this new study indicates that use of prescription opioids during pregnancy has been increasing and is associated with this rise in NAS. The use of any opioids during pregnancy (28%) now matches the rate of any alcohol (23.7%) and tobacco use (27.7%). Chronic users of opioids are fewer in number, but much more likely to yield withdrawal in the neonate.

The article identifies cofactors (cigarette and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use) that increase the likelihood of a given amount of maternal opiate use leading to clinical NAS. So the use of those substances should be solicited in history along with the types, frequency, and duration of any opioid use. It would be ideal if this information was collected during the obstetric admission process along with maternal blood type, group B strep status, hepatitis B, and other labs. Observation for signs of withdrawal deserves as much attention as that paid to getting the hearing screen done and the bilirubin checked. It is harming more newborns.

Kevin T. Powell, M.D., Ph.D., is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome is a rapidly growing problem, increasing 16-fold in Tennessee in 13 years. At a rate of 12 cases per 1,000 births in 2013, the incidence is now 10 times more likely than group B strep sepsis, congenital deafness, or dislocated hips, and many times more likely than a bilirubin of 20. So screening for it must become standard newborn care.

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics 2012 guidelines (Pediatrics 2012;129:e540-60) noted that 45-87 out of 1,000 mothers are using illicit drugs during pregnancy, this new study indicates that use of prescription opioids during pregnancy has been increasing and is associated with this rise in NAS. The use of any opioids during pregnancy (28%) now matches the rate of any alcohol (23.7%) and tobacco use (27.7%). Chronic users of opioids are fewer in number, but much more likely to yield withdrawal in the neonate.

The article identifies cofactors (cigarette and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use) that increase the likelihood of a given amount of maternal opiate use leading to clinical NAS. So the use of those substances should be solicited in history along with the types, frequency, and duration of any opioid use. It would be ideal if this information was collected during the obstetric admission process along with maternal blood type, group B strep status, hepatitis B, and other labs. Observation for signs of withdrawal deserves as much attention as that paid to getting the hearing screen done and the bilirubin checked. It is harming more newborns.

Kevin T. Powell, M.D., Ph.D., is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Infants born to women taking prescription opioids were more likely to have neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) if their mothers smoked tobacco or took selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to a recent study. Cumulative opioid exposure and opioid type (maintenance and long-acting) also increased the risk of NAS.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all opioid-exposed infants be observed in the hospital for 4 to 7 days after birth. However, our data suggest there was a wide variability in an infant’s risk of drug withdrawal based on opioid type, dose, SSRI use, and number of cigarettes smoked per day by the mother,” reported Dr. Stephen W. Patrick of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “Future studies should evaluate new care models for opioid-exposed infants at different risk levels of developing NAS,” wrote Dr. Patrick and his associates [Pediatrics 2015 April 13 [doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3299]).

Dr. Patrick’s team analyzed prescription data and vital statistics of 112,029 pregnant women and their newborns who were enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program between 2009 and 2011. Of these, 28% of the women filled at least one prescription for opioids; these included 96.2% taking short-acting medications, 2.7% receiving maintenance treatment for substance use disorders and 0.6% taking long-acting medications.

Among women taking prescription opioids, 5.3% had depression, 4.3% had an anxiety disorder, 41.8% smoked, 4.3% had been prescribed SSRIs within 30 days before birth, 8.3% had headache or migraine, and 23.7% had musculoskeletal disease, compared to 2.7%, 1.6% and 25.8%, 1.9%, 2.0% and 5.8%, respectively, for mothers not taking opioids.

Nearly a third of women on maintenance therapy (29.3%) had infants with NAS while 14.7% of mothers taking long-acting opioids and 1.4% of women taking short-acting preparations had newborns with NAS. Newborns were twice as likely to develop NAS if their mothers took SSRIs (odds ratio, 2.08), and their risk of NAS increased in a dose-response fashion with the number of daily cigarettes their mothers smoked.

NAS rates nearly doubled during the course of the study, landing at 10.7 per 1,000 births in the final year. Among the 1,086 newborns diagnosed with NAS, 21.2% had low birth weight, 16.7% were preterm, 28.7% had respiratory diagnoses, 13.1% had feeding difficulties, 7.2% had sepsis, and 3.7% had seizures. Among those exposed to opioids who did not develop NAS, 11.8% had low birth weight, 11.6% were preterm, 10.1% had respiratory diagnoses, 2.6% had feeding difficulties, 2.3% had sepsis and 0.4% had seizures. Among unexposed newborns, 9.9% had low birth weight, 11% were preterm, 8.8% had respiratory diagnoses, 2.3% had feeding difficulties, 1.9% had sepsis, and 0.3% had seizures.

“Public health efforts should focus on limiting inappropriate [opioid pain relievers] and tobacco use in pregnancy,” the authors wrote. “Prescribing opioids in pregnancy should be done with caution because it can lead to significant complications for the neonate.”

The research was funded by the Tennessee Department of Health and the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no disclosures.

Infants born to women taking prescription opioids were more likely to have neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) if their mothers smoked tobacco or took selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to a recent study. Cumulative opioid exposure and opioid type (maintenance and long-acting) also increased the risk of NAS.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all opioid-exposed infants be observed in the hospital for 4 to 7 days after birth. However, our data suggest there was a wide variability in an infant’s risk of drug withdrawal based on opioid type, dose, SSRI use, and number of cigarettes smoked per day by the mother,” reported Dr. Stephen W. Patrick of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “Future studies should evaluate new care models for opioid-exposed infants at different risk levels of developing NAS,” wrote Dr. Patrick and his associates [Pediatrics 2015 April 13 [doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3299]).