User login

New uterine compression technique controls postpartum hemorrhage

A newly described uterine compression technique that uses simple supplies and does not require hysterotomy was successful in controlling postpartum hemorrhage in 16 of 18 (89%) women in two teaching hospitals in Nigeria, averting the need for hysterectomy in these women.

Each of the women had severe postpartum hemorrhage attributable to uterine atony and had undergone local protocols for medical management “to no avail,” Chidi Ochu Uzoma Esike, MD, who developed the technique, wrote in a report published in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The technique involves placing six polyglactin (Vicryl) #2 or chromic #2 sutures in the lower uterine segment – three anteriorly and three posteriorly – and could be particularly useful in developing countries, where many women die from postpartum hemorrhage “because most of the medical officers who attend the majority of births in health facilities can perform cesarean delivery but cannot perform hysterectomy and find existing compression suture techniques too complex to perform,” Dr. Esike wrote in the case series report.

In addition, “specialized sutures and needles required for some of the known compression techniques are not readily available,” said Dr. Esike of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Alex Ekwueme Federal University Hospital and Ebyonyi State University in Abakaliki, Nigeria.

Angela Martin, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said that “having a quick and effective surgical technique [for uncontrollable postpartum hemorrhage] is essential.”

“I love that Esike’s technique uses polyglactin (Vicryl) or chromic sutures. These are familiar to most surgeons, cheap, and typically available even in most resource-deficient settings,” said Dr. Martin, who was asked to comment on the report, adding that several of the known surgical techniques for uterine atony require a skilled operator and are indeed not universally feasible.

“If successful,” Dr. Martin said in an interview, “compression sutures can be lifesaving and fertility preserving.”

The technique involves tying the two middle sutures (one placed anteriorly and one posteriorly) at the fundus as an assistant slowly and continuously compresses the uterus. The more laterally placed sutures are tied similarly, with each pair tied at about 4 cm from the lateral edge of the uterus. “As the uterus is compressed, the slack should be taken up by the sutures before tying,” said Dr. Esike, whose report features both diagrammatic and photographic representations of suture insertion and tying.

For patients who delivered vaginally – nine in this case series – the technique involves performing a laparotomy and exteriorizing the uterus. The technique’s “suture placement,” Dr. Esike wrote, “took 11-25 minutes from the onset of laparotomy to completion.” There were no short or long-term complications in any of the 18 patients.

B-Lynch compression sutures are more complex to perform and require a larger curved needle, Dr. Esike wrote, and the Hayman technique similarly requires a longer needle that may not be available in resource-constrained countries. The hysterotomy required in the B-Lynch technique, Dr. Esike added, “leads to the uterus not contracting maximally until it is repaired,” which increases blood loss from the procedure.

Dr. Martin said the small size of the case series is not discouraging. “The B-Lynch suture was widely adopted after it was described in five cases in 1997,” she said. There are no randomized controlled trials to suggest that one method of uterine compression sutures is better than another. “Ultimately,” she said, “the technique chosen will depend on the surgeon’s training and available supplies.”

Dr. Esike had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Martin had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Esike COU. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003947.

A newly described uterine compression technique that uses simple supplies and does not require hysterotomy was successful in controlling postpartum hemorrhage in 16 of 18 (89%) women in two teaching hospitals in Nigeria, averting the need for hysterectomy in these women.

Each of the women had severe postpartum hemorrhage attributable to uterine atony and had undergone local protocols for medical management “to no avail,” Chidi Ochu Uzoma Esike, MD, who developed the technique, wrote in a report published in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The technique involves placing six polyglactin (Vicryl) #2 or chromic #2 sutures in the lower uterine segment – three anteriorly and three posteriorly – and could be particularly useful in developing countries, where many women die from postpartum hemorrhage “because most of the medical officers who attend the majority of births in health facilities can perform cesarean delivery but cannot perform hysterectomy and find existing compression suture techniques too complex to perform,” Dr. Esike wrote in the case series report.

In addition, “specialized sutures and needles required for some of the known compression techniques are not readily available,” said Dr. Esike of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Alex Ekwueme Federal University Hospital and Ebyonyi State University in Abakaliki, Nigeria.

Angela Martin, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said that “having a quick and effective surgical technique [for uncontrollable postpartum hemorrhage] is essential.”

“I love that Esike’s technique uses polyglactin (Vicryl) or chromic sutures. These are familiar to most surgeons, cheap, and typically available even in most resource-deficient settings,” said Dr. Martin, who was asked to comment on the report, adding that several of the known surgical techniques for uterine atony require a skilled operator and are indeed not universally feasible.

“If successful,” Dr. Martin said in an interview, “compression sutures can be lifesaving and fertility preserving.”

The technique involves tying the two middle sutures (one placed anteriorly and one posteriorly) at the fundus as an assistant slowly and continuously compresses the uterus. The more laterally placed sutures are tied similarly, with each pair tied at about 4 cm from the lateral edge of the uterus. “As the uterus is compressed, the slack should be taken up by the sutures before tying,” said Dr. Esike, whose report features both diagrammatic and photographic representations of suture insertion and tying.

For patients who delivered vaginally – nine in this case series – the technique involves performing a laparotomy and exteriorizing the uterus. The technique’s “suture placement,” Dr. Esike wrote, “took 11-25 minutes from the onset of laparotomy to completion.” There were no short or long-term complications in any of the 18 patients.

B-Lynch compression sutures are more complex to perform and require a larger curved needle, Dr. Esike wrote, and the Hayman technique similarly requires a longer needle that may not be available in resource-constrained countries. The hysterotomy required in the B-Lynch technique, Dr. Esike added, “leads to the uterus not contracting maximally until it is repaired,” which increases blood loss from the procedure.

Dr. Martin said the small size of the case series is not discouraging. “The B-Lynch suture was widely adopted after it was described in five cases in 1997,” she said. There are no randomized controlled trials to suggest that one method of uterine compression sutures is better than another. “Ultimately,” she said, “the technique chosen will depend on the surgeon’s training and available supplies.”

Dr. Esike had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Martin had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Esike COU. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003947.

A newly described uterine compression technique that uses simple supplies and does not require hysterotomy was successful in controlling postpartum hemorrhage in 16 of 18 (89%) women in two teaching hospitals in Nigeria, averting the need for hysterectomy in these women.

Each of the women had severe postpartum hemorrhage attributable to uterine atony and had undergone local protocols for medical management “to no avail,” Chidi Ochu Uzoma Esike, MD, who developed the technique, wrote in a report published in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The technique involves placing six polyglactin (Vicryl) #2 or chromic #2 sutures in the lower uterine segment – three anteriorly and three posteriorly – and could be particularly useful in developing countries, where many women die from postpartum hemorrhage “because most of the medical officers who attend the majority of births in health facilities can perform cesarean delivery but cannot perform hysterectomy and find existing compression suture techniques too complex to perform,” Dr. Esike wrote in the case series report.

In addition, “specialized sutures and needles required for some of the known compression techniques are not readily available,” said Dr. Esike of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Alex Ekwueme Federal University Hospital and Ebyonyi State University in Abakaliki, Nigeria.

Angela Martin, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said that “having a quick and effective surgical technique [for uncontrollable postpartum hemorrhage] is essential.”

“I love that Esike’s technique uses polyglactin (Vicryl) or chromic sutures. These are familiar to most surgeons, cheap, and typically available even in most resource-deficient settings,” said Dr. Martin, who was asked to comment on the report, adding that several of the known surgical techniques for uterine atony require a skilled operator and are indeed not universally feasible.

“If successful,” Dr. Martin said in an interview, “compression sutures can be lifesaving and fertility preserving.”

The technique involves tying the two middle sutures (one placed anteriorly and one posteriorly) at the fundus as an assistant slowly and continuously compresses the uterus. The more laterally placed sutures are tied similarly, with each pair tied at about 4 cm from the lateral edge of the uterus. “As the uterus is compressed, the slack should be taken up by the sutures before tying,” said Dr. Esike, whose report features both diagrammatic and photographic representations of suture insertion and tying.

For patients who delivered vaginally – nine in this case series – the technique involves performing a laparotomy and exteriorizing the uterus. The technique’s “suture placement,” Dr. Esike wrote, “took 11-25 minutes from the onset of laparotomy to completion.” There were no short or long-term complications in any of the 18 patients.

B-Lynch compression sutures are more complex to perform and require a larger curved needle, Dr. Esike wrote, and the Hayman technique similarly requires a longer needle that may not be available in resource-constrained countries. The hysterotomy required in the B-Lynch technique, Dr. Esike added, “leads to the uterus not contracting maximally until it is repaired,” which increases blood loss from the procedure.

Dr. Martin said the small size of the case series is not discouraging. “The B-Lynch suture was widely adopted after it was described in five cases in 1997,” she said. There are no randomized controlled trials to suggest that one method of uterine compression sutures is better than another. “Ultimately,” she said, “the technique chosen will depend on the surgeon’s training and available supplies.”

Dr. Esike had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Martin had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Esike COU. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003947.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Treatment for a tobacco-dependent adult

Applying American Thoracic Society’s new clinical practice guideline

Complications from tobacco use are the most common preventable cause of death, disability, and disease in the United States. Tobacco use causes 480,000 premature deaths every year. In pregnancy, tobacco use causes complications such as premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and placental abruption. In the perinatal period, it is associated with sudden infant death syndrome. While cigarette smoking is decreasing in adolescents, e-cigarette use in on the rise. Approximately 1,600 children aged 12-17 smoke their first cigarette every day and it is estimated that 5.6 million children and adolescents will die of a tobacco use–related death.1 For these reasons it is important to address tobacco use and cessation with patients whenever it is possible.

Case

A forty-five-year-old male who rarely comes to the office is here today for a physical exam at the urging of his partner. He has been smoking a pack a day since age 17. You have tried at past visits to discuss quitting, but he had been in the precontemplative stage and had been unwilling to consider any change. This visit, however, he is ready to try to quit. What can you offer him?

Core recommendations from ATS guidelines

This patient can be offered varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy rather than nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, e-cigarettes, or varenicline alone. His course of therapy should extend beyond 12 weeks instead of the standard 6- to 12-week therapy. Alternatively, he could be offered varenicline alone, rather than nicotine replacement.2

A change from previous guidelines

What makes this recommendation so interesting and new is the emphasis it places on varenicline. The United States Preventive Services Task Force released a recommendation statement in 2015 that stressed a combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. It discussed nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, but did not recommend any one over any of the others.3 The new recommendation from the American Thoracic Society favors varenicline over other pharmacologic interventions. It is based on an independent systematic review of the literature that showed higher rates of tobacco use abstinence at the 6-month follow-up with varenicline alone versus nicotine replacement therapy alone, bupropion alone, or e-cigarette use only.

A review of 14 randomized controlled trials showed that varenicline improves abstinence rates during treatment by approximately 40% compared with nicotine replacement, and by 20% at the end of 6 months of treatment. The review found that varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy is more effective than varenicline alone. In this comparison, based on three trials, there was a 36% higher abstinence rate at 6 months using varenicline plus nicotine replacement. When varenicline use was compared with use of a nicotine patch, bupropion, or e-cigarettes, there was a reduction in serious adverse events – changes in mood, suicidal ideation, and neurological side effects such as seizures.2 Clinicians may remember a black box warning on the varenicline label citing neuropsychiatric effects and it is important to note that the Food and Drug Administration removed this boxed warning in 2016.4

Opinion

This recommendation represents an important, evidence-based change from previous guidelines. It presents the opportunity for better outcomes, but will likely take a while to filter into practice, as clinicians need to become more comfortable with the use of varenicline and insurance supports the cost of varenicline.

The average cost of varenicline for 12 weeks is between $1,220 and $1,584. For comparison, nicotine replacement therapy costs $170 to $240 for the same number of weeks. To put those costs in perspective, the 12-week cost of cigarettes for a two-pack-a-day smoker is approximately $1,000.

For some patients, the motivation to quit smoking comes from the realization of how much they are spending on cigarettes each month. That said, if a patient does not have insurance or their insurance does not cover the cost of varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy might be more appealing. It should be noted that better abstinence rates have been seen in patients taking varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy versus varenicline alone.

Suggested treatment

Based on a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the American Thoracic Society’s guideline on pharmacological treatment in tobacco-dependent adults concludes that varenicline plus nicotine patch is the preferred pharmacological treatment for tobacco cessation when compared with varenicline alone, bupropion alone, nicotine replacement therapy alone, and e-cigarettes alone. If the patient does not want to start two medicines at once, then varenicline alone would be the preferred choice.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Sprogell is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA.2020;323(16):1590-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679.

2. Leone FT et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5–e31.

3. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015 Sep 21.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. 2016 Dec. 16.

Applying American Thoracic Society’s new clinical practice guideline

Applying American Thoracic Society’s new clinical practice guideline

Complications from tobacco use are the most common preventable cause of death, disability, and disease in the United States. Tobacco use causes 480,000 premature deaths every year. In pregnancy, tobacco use causes complications such as premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and placental abruption. In the perinatal period, it is associated with sudden infant death syndrome. While cigarette smoking is decreasing in adolescents, e-cigarette use in on the rise. Approximately 1,600 children aged 12-17 smoke their first cigarette every day and it is estimated that 5.6 million children and adolescents will die of a tobacco use–related death.1 For these reasons it is important to address tobacco use and cessation with patients whenever it is possible.

Case

A forty-five-year-old male who rarely comes to the office is here today for a physical exam at the urging of his partner. He has been smoking a pack a day since age 17. You have tried at past visits to discuss quitting, but he had been in the precontemplative stage and had been unwilling to consider any change. This visit, however, he is ready to try to quit. What can you offer him?

Core recommendations from ATS guidelines

This patient can be offered varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy rather than nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, e-cigarettes, or varenicline alone. His course of therapy should extend beyond 12 weeks instead of the standard 6- to 12-week therapy. Alternatively, he could be offered varenicline alone, rather than nicotine replacement.2

A change from previous guidelines

What makes this recommendation so interesting and new is the emphasis it places on varenicline. The United States Preventive Services Task Force released a recommendation statement in 2015 that stressed a combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. It discussed nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, but did not recommend any one over any of the others.3 The new recommendation from the American Thoracic Society favors varenicline over other pharmacologic interventions. It is based on an independent systematic review of the literature that showed higher rates of tobacco use abstinence at the 6-month follow-up with varenicline alone versus nicotine replacement therapy alone, bupropion alone, or e-cigarette use only.

A review of 14 randomized controlled trials showed that varenicline improves abstinence rates during treatment by approximately 40% compared with nicotine replacement, and by 20% at the end of 6 months of treatment. The review found that varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy is more effective than varenicline alone. In this comparison, based on three trials, there was a 36% higher abstinence rate at 6 months using varenicline plus nicotine replacement. When varenicline use was compared with use of a nicotine patch, bupropion, or e-cigarettes, there was a reduction in serious adverse events – changes in mood, suicidal ideation, and neurological side effects such as seizures.2 Clinicians may remember a black box warning on the varenicline label citing neuropsychiatric effects and it is important to note that the Food and Drug Administration removed this boxed warning in 2016.4

Opinion

This recommendation represents an important, evidence-based change from previous guidelines. It presents the opportunity for better outcomes, but will likely take a while to filter into practice, as clinicians need to become more comfortable with the use of varenicline and insurance supports the cost of varenicline.

The average cost of varenicline for 12 weeks is between $1,220 and $1,584. For comparison, nicotine replacement therapy costs $170 to $240 for the same number of weeks. To put those costs in perspective, the 12-week cost of cigarettes for a two-pack-a-day smoker is approximately $1,000.

For some patients, the motivation to quit smoking comes from the realization of how much they are spending on cigarettes each month. That said, if a patient does not have insurance or their insurance does not cover the cost of varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy might be more appealing. It should be noted that better abstinence rates have been seen in patients taking varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy versus varenicline alone.

Suggested treatment

Based on a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the American Thoracic Society’s guideline on pharmacological treatment in tobacco-dependent adults concludes that varenicline plus nicotine patch is the preferred pharmacological treatment for tobacco cessation when compared with varenicline alone, bupropion alone, nicotine replacement therapy alone, and e-cigarettes alone. If the patient does not want to start two medicines at once, then varenicline alone would be the preferred choice.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Sprogell is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA.2020;323(16):1590-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679.

2. Leone FT et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5–e31.

3. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015 Sep 21.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. 2016 Dec. 16.

Complications from tobacco use are the most common preventable cause of death, disability, and disease in the United States. Tobacco use causes 480,000 premature deaths every year. In pregnancy, tobacco use causes complications such as premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and placental abruption. In the perinatal period, it is associated with sudden infant death syndrome. While cigarette smoking is decreasing in adolescents, e-cigarette use in on the rise. Approximately 1,600 children aged 12-17 smoke their first cigarette every day and it is estimated that 5.6 million children and adolescents will die of a tobacco use–related death.1 For these reasons it is important to address tobacco use and cessation with patients whenever it is possible.

Case

A forty-five-year-old male who rarely comes to the office is here today for a physical exam at the urging of his partner. He has been smoking a pack a day since age 17. You have tried at past visits to discuss quitting, but he had been in the precontemplative stage and had been unwilling to consider any change. This visit, however, he is ready to try to quit. What can you offer him?

Core recommendations from ATS guidelines

This patient can be offered varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy rather than nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, e-cigarettes, or varenicline alone. His course of therapy should extend beyond 12 weeks instead of the standard 6- to 12-week therapy. Alternatively, he could be offered varenicline alone, rather than nicotine replacement.2

A change from previous guidelines

What makes this recommendation so interesting and new is the emphasis it places on varenicline. The United States Preventive Services Task Force released a recommendation statement in 2015 that stressed a combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. It discussed nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, but did not recommend any one over any of the others.3 The new recommendation from the American Thoracic Society favors varenicline over other pharmacologic interventions. It is based on an independent systematic review of the literature that showed higher rates of tobacco use abstinence at the 6-month follow-up with varenicline alone versus nicotine replacement therapy alone, bupropion alone, or e-cigarette use only.

A review of 14 randomized controlled trials showed that varenicline improves abstinence rates during treatment by approximately 40% compared with nicotine replacement, and by 20% at the end of 6 months of treatment. The review found that varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy is more effective than varenicline alone. In this comparison, based on three trials, there was a 36% higher abstinence rate at 6 months using varenicline plus nicotine replacement. When varenicline use was compared with use of a nicotine patch, bupropion, or e-cigarettes, there was a reduction in serious adverse events – changes in mood, suicidal ideation, and neurological side effects such as seizures.2 Clinicians may remember a black box warning on the varenicline label citing neuropsychiatric effects and it is important to note that the Food and Drug Administration removed this boxed warning in 2016.4

Opinion

This recommendation represents an important, evidence-based change from previous guidelines. It presents the opportunity for better outcomes, but will likely take a while to filter into practice, as clinicians need to become more comfortable with the use of varenicline and insurance supports the cost of varenicline.

The average cost of varenicline for 12 weeks is between $1,220 and $1,584. For comparison, nicotine replacement therapy costs $170 to $240 for the same number of weeks. To put those costs in perspective, the 12-week cost of cigarettes for a two-pack-a-day smoker is approximately $1,000.

For some patients, the motivation to quit smoking comes from the realization of how much they are spending on cigarettes each month. That said, if a patient does not have insurance or their insurance does not cover the cost of varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy might be more appealing. It should be noted that better abstinence rates have been seen in patients taking varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy versus varenicline alone.

Suggested treatment

Based on a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the American Thoracic Society’s guideline on pharmacological treatment in tobacco-dependent adults concludes that varenicline plus nicotine patch is the preferred pharmacological treatment for tobacco cessation when compared with varenicline alone, bupropion alone, nicotine replacement therapy alone, and e-cigarettes alone. If the patient does not want to start two medicines at once, then varenicline alone would be the preferred choice.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Sprogell is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA.2020;323(16):1590-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679.

2. Leone FT et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5–e31.

3. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015 Sep 21.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. 2016 Dec. 16.

Comment & Controversy

How do you feel about expectantly managing a well-dated pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Is it reasonable to choose the age of 40 for proposing an anticipation of labor induction?

In physiologic ongoing pregnancies (whether they are spontaneous or autologous in vitro fertilization [IVF] or heterologous IVF), the evidence for anticipating labor induction based upon the only factor of age (after 40 years) is missing. Nonetheless, the number of women becoming pregnant at an older age is expected to increase, and from my perspective, to induce all physiologic pregnancies at term by 41 weeks and 5 days’ gestation does not appear to be best practice. I favor the idea of all women aged 40 and older to start labor induction earlier (for instance, to offer labor induction, with proper informed consent, by 41+ 0 and not 41+ 5 through 42+ 0 weeks of pregnancy).

Luca Bernardini, MD

La Spezia, Italy

Dr. Barbieri responds

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, our approach is to offer women ≥40 years of age induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there is an obstetric contraindication to IOL. We believe that IOL at 39 weeks’ gestation is associated with a reduced risk of both cesarean delivery and a new diagnosis of hypertension.1

Reference

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy, UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

What is the optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; JANUARY 2020)

OCs and spironolactone study

I often recommend oral contraceptives (OCs) containing drospirenone for patients with polycyctic ovary syndrome (PCOS)-associated mild acne and hirsutism—since OCs are already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for acne, with similar effects as spironolactone. My patients seem to do well on an OC, and require only one medication. Of course, I would add spironolactone to the treatment regimen and switch OCs if she was not responding well.

Michael T. Cane, MD

Arlington, Texas

Dr. Barbieri responds

The Endocrine Society agrees with Dr. Cane’s approach, recommending the initiation of monotherapy with an estrogen-progestin followed by the addition of spironolactone if 6 months of monotherapy produces insufficient improvement in dermatologic symptoms of PCOS, including hirsutism and acne. Most contraceptives contain 3 mg or 4 mg of drospirenone, which is thought to have antiandrogenic effects similar to spironolactone 25 mg. I believe that spironolactone 100 mg provides more complete and rapid resolution of the dermatologic symptoms caused by PCOS. Hence, I initiate both an estrogen-progestin contraceptive with spironolactone.

How do you feel about expectantly managing a well-dated pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Is it reasonable to choose the age of 40 for proposing an anticipation of labor induction?

In physiologic ongoing pregnancies (whether they are spontaneous or autologous in vitro fertilization [IVF] or heterologous IVF), the evidence for anticipating labor induction based upon the only factor of age (after 40 years) is missing. Nonetheless, the number of women becoming pregnant at an older age is expected to increase, and from my perspective, to induce all physiologic pregnancies at term by 41 weeks and 5 days’ gestation does not appear to be best practice. I favor the idea of all women aged 40 and older to start labor induction earlier (for instance, to offer labor induction, with proper informed consent, by 41+ 0 and not 41+ 5 through 42+ 0 weeks of pregnancy).

Luca Bernardini, MD

La Spezia, Italy

Dr. Barbieri responds

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, our approach is to offer women ≥40 years of age induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there is an obstetric contraindication to IOL. We believe that IOL at 39 weeks’ gestation is associated with a reduced risk of both cesarean delivery and a new diagnosis of hypertension.1

Reference

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy, UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

What is the optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; JANUARY 2020)

OCs and spironolactone study

I often recommend oral contraceptives (OCs) containing drospirenone for patients with polycyctic ovary syndrome (PCOS)-associated mild acne and hirsutism—since OCs are already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for acne, with similar effects as spironolactone. My patients seem to do well on an OC, and require only one medication. Of course, I would add spironolactone to the treatment regimen and switch OCs if she was not responding well.

Michael T. Cane, MD

Arlington, Texas

Dr. Barbieri responds

The Endocrine Society agrees with Dr. Cane’s approach, recommending the initiation of monotherapy with an estrogen-progestin followed by the addition of spironolactone if 6 months of monotherapy produces insufficient improvement in dermatologic symptoms of PCOS, including hirsutism and acne. Most contraceptives contain 3 mg or 4 mg of drospirenone, which is thought to have antiandrogenic effects similar to spironolactone 25 mg. I believe that spironolactone 100 mg provides more complete and rapid resolution of the dermatologic symptoms caused by PCOS. Hence, I initiate both an estrogen-progestin contraceptive with spironolactone.

How do you feel about expectantly managing a well-dated pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Is it reasonable to choose the age of 40 for proposing an anticipation of labor induction?

In physiologic ongoing pregnancies (whether they are spontaneous or autologous in vitro fertilization [IVF] or heterologous IVF), the evidence for anticipating labor induction based upon the only factor of age (after 40 years) is missing. Nonetheless, the number of women becoming pregnant at an older age is expected to increase, and from my perspective, to induce all physiologic pregnancies at term by 41 weeks and 5 days’ gestation does not appear to be best practice. I favor the idea of all women aged 40 and older to start labor induction earlier (for instance, to offer labor induction, with proper informed consent, by 41+ 0 and not 41+ 5 through 42+ 0 weeks of pregnancy).

Luca Bernardini, MD

La Spezia, Italy

Dr. Barbieri responds

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, our approach is to offer women ≥40 years of age induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there is an obstetric contraindication to IOL. We believe that IOL at 39 weeks’ gestation is associated with a reduced risk of both cesarean delivery and a new diagnosis of hypertension.1

Reference

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy, UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

What is the optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; JANUARY 2020)

OCs and spironolactone study

I often recommend oral contraceptives (OCs) containing drospirenone for patients with polycyctic ovary syndrome (PCOS)-associated mild acne and hirsutism—since OCs are already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for acne, with similar effects as spironolactone. My patients seem to do well on an OC, and require only one medication. Of course, I would add spironolactone to the treatment regimen and switch OCs if she was not responding well.

Michael T. Cane, MD

Arlington, Texas

Dr. Barbieri responds

The Endocrine Society agrees with Dr. Cane’s approach, recommending the initiation of monotherapy with an estrogen-progestin followed by the addition of spironolactone if 6 months of monotherapy produces insufficient improvement in dermatologic symptoms of PCOS, including hirsutism and acne. Most contraceptives contain 3 mg or 4 mg of drospirenone, which is thought to have antiandrogenic effects similar to spironolactone 25 mg. I believe that spironolactone 100 mg provides more complete and rapid resolution of the dermatologic symptoms caused by PCOS. Hence, I initiate both an estrogen-progestin contraceptive with spironolactone.

Pregnancy of unknown location: Evidence-based evaluation and management

CASE Woman with bleeding in early pregnancy

A 31-year-old woman (G1P0) presents to the local emergency department (ED) due to bleeding in pregnancy. She reports a prior open appendectomy for ruptured appendix; she denies a history of sexually transmitted infections, smoking, and contraception use. She reports having regular menstrual cycles and trying to conceive with her husband for 18 months without success until now.

The patient reports that the previous week she took a home pregnancy test that was positive; she endorses having dark brown spotting for the past 2 days but denies pain. Based on the date of her last menstrual period, gestational age is estimated to be 5 weeks and 1 day. Her human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is 1,670 mIU/mL. Transvaginal ultrasonography demonstrates a normal uterus with an endometrial thickness of 10 mm, no evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), normal adnexa bilaterally, and scant free fluid in the pelvis.

Identifying and evaluating pregnancy of unknown location

A pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) is defined by a positive serum hCG level in the absence of a visualized IUP or ectopic pregnancy (EP) by pelvic ultrasonography.

Because of variations in screening tools and clinical practices between institutions and care settings (for example, EDs versus specialized outpatient offices), the incidence of PUL is difficult to capture. In specialized early pregnancy clinics, the rate is 8% to 10%, whereas in the ED setting, the PUL rate has been reported to be as high as 42%.1-6 While approximately 98% to 99% of all pregnancies are intrauterine, only 30% of PULs will continue to develop as viable ongoing intrauterine gestations.7-9 The remainder are revealed as failing IUPs or EPs. To counsel patients, set expectations, and triage to appropriate management, it is critical to diagnose pregnancy location as efficiently as possible.

Ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancies represent only 1% to 2% of conceptions (both spontaneous and through assisted reproduction) and occur most commonly in the fallopian tube, although EPs also can implant in the cornua of the uterus, the cervix, cesarean scar, and more rarely on the ovary or abdominal viscera.10,11 Least common, heterotopic pregnancies—in which an IUP coexists with an EP—occur in 1 in 4,000 to 30,000 pregnancies, more commonly in women who used assisted reproduction.11

Major risk factors for EP include a history of tubal surgery, sexually transmitted infections (particularly Chlamydia trachomatis), pelvic inflammatory disease, conception with an intrauterine device in situ, and a history of prior EP or tubal surgery, particularly prior tubal ligation; minor risk factors include a history of infertility (excluding known tubal factor infertility) or smoking (in a dose-dependent manner).11,12 The concern for an EP is heightened in patients with these risk factors.

Because of the possibility of rupture and life-threatening hemorrhage, EP carries a risk of significant morbidity and mortality.13 Ruptured EPs account for approximately 2.7% of all maternal deaths each year.14 When diagnosed sufficiently early in a stable patient, most EPs can be managed medically with methotrexate, a folic acid antagonist.15 Ectopic pregnancies also may be managed surgically, and emergency surgery is indicated in women with evidence of EP rupture and intraperitoneal bleeding.

Continue to: Intrauterine pregnancy...

Intrauterine pregnancy

While excluding EP is critical, it is equally important to diagnose an IUP as expeditiously as possible to avoid inadvertent, destructive intervention. Diagnosis and management of a PUL can involve endometrial aspiration, which would interrupt an IUP and should be avoided until the possibility of a viable IUP has been eliminated in desired pregnancies. The inadvertent administration of methotrexate, a known teratogen, to a patient with an undiagnosed viable IUP can result in miscarriage, elective termination, or a live-born infant with significant malformations, all of which expose the administering physician to malpractice litigation.16,17

In desired pregnancies, it is essential to differentiate between a viable IUP, a nonviable IUP, and an EP to guide appropriate management and ensure patient safety, whereas exclusion of EP is the priority in undesired pregnancies.

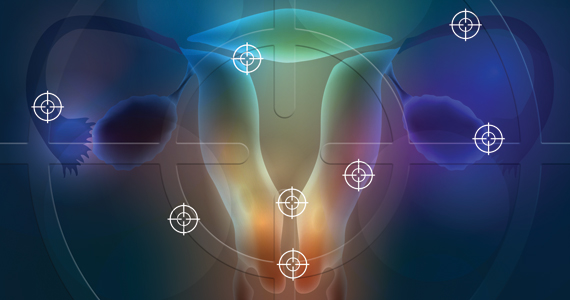

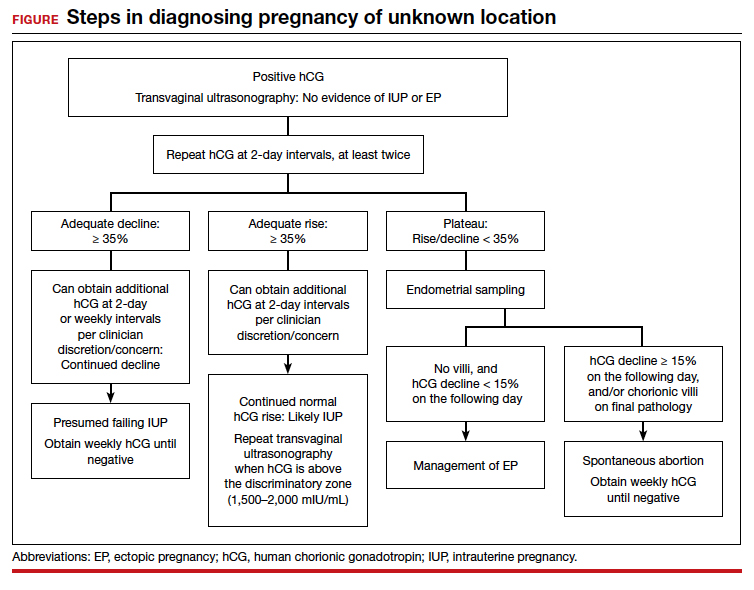

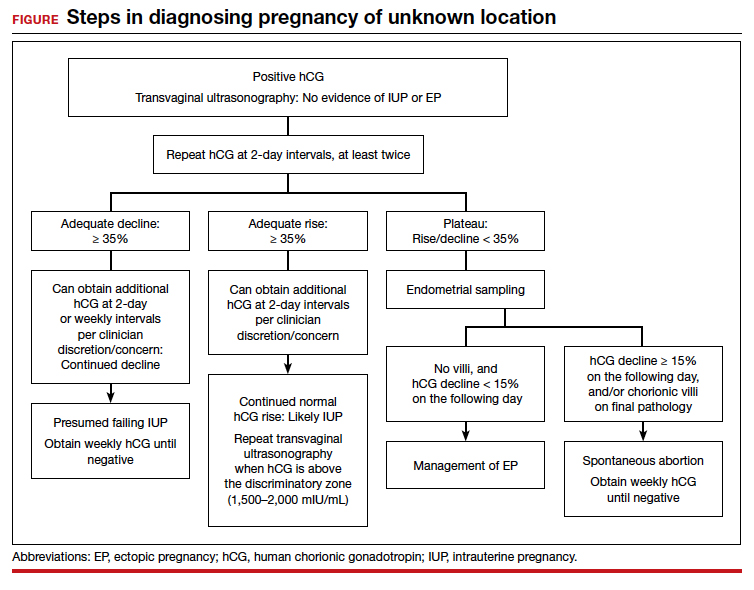

Tools for diagnosing pregnancy location

For diagnosing pregnancy location, serial hCG measurement, transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography, and outpatient endometrial aspiration are all relevant clinical tools. Pregnancy location can be diagnosed with either direct visualization of an IUP or EP by ultrasonography or with confirmed pathology (chorionic villi or trophoblast cells) from endometrial aspiration (FIGURE). A decline in hCG to an undetectable level following endometrial aspiration also is considered sufficient to diagnose a failed IUP, even in the absence of a confirmatory ultrasonography.

Trending hCG values

In stable patients with PUL, serum hCG levels are commonly measured at 2-day intervals, ideally for a minimum of 3 values. Conventional wisdom dictates that in viable IUPs, the hCG level should roughly double every 2 days. However, more recent data suggest that the threshold for minimum expected hCG rise for an ongoing IUP should be far lower when the pregnancy is desired.18 A less conservative cutoff can be considered when a pregnancy is not desired.

In a multisite cohort study of 1,005 women with PUL, a minimum hCG rise of 35% in 2 days captured the majority of IUPs, with a negative predictive value of 97.2% for IUP.19 Of note, although the cutoff of 35% was selected to reduce the risk of misdiagnosing an IUP as an EP, 7.7% of IUPs (and 16.8% of EPs) were still misclassified, showing that hCG trends must be interpreted in the context of other clinical data, including ultrasonography findings and patient symptoms and history.

A follow-up study demonstrated that hCG rises are lower (but still within this normal range) when the initial hCG value is higher, particularly greater than 3,000 mIU/mL.20

Studies show that the rate of spontaneous hCG decline in failing IUPs ranges from 12% to 47% in 2 days, falling more rapidly from higher starting hCG values.19,21 In a retrospective review of 443 women with spontaneously resolving PUL (presumed to be failing IUPs), the minimum 2-day decline in hCG was 35%.22 Any spontaneous hCG decline less than 35% in 2 days in a PUL should raise physician concern for EP.

Conversely, EPs do not demonstrate predictable hCG trends and can mimic the hCG trends of viable or failing IUPs. Although typically half of EPs present with an increasing hCG value and half present with a decreasing hCG value, the majority (71%) demonstrate a slower rate of change than either a viable IUP or a miscarriage.11 This slower change (plateau) should heighten the clinician’s suspicion for an EP.

Continue to: Progesterone levels...

Progesterone levels

A progesterone level often is used to attempt to determine pregnancy viability in women who are not receiving progesterone supplementation, although it ultimately has limited utility. While far less sensitive than an hCG value trend, a serum progesterone level of less than 5 to 10 ng/mL is a rough marker of nonviable pregnancy.23

In a large meta-analysis of women with pain and bleeding, 96.8% of pregnancies with a single progesterone level of less than 10 ng/mL were nonviable.23 When an inconclusive ultrasonography was documented in addition to symptoms of pain and bleeding, 99.2% of pregnancies with a progesterone level of less than 3.2 to 6 ng/mL were nonviable.

Progesterone’s usefulness in assessing for a PUL is limited: While progesterone levels may indicate nonviability, they provide no indication of pregnancy location (intrauterine or ectopic).

Alternative serologic markers

Various other reproductive and pregnancy-related hormones have been investigated for use in the diagnosis of pregnancy location in PULs, including activin A, inhibin A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A), placental-like growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, follistatin, and various microRNAs.24,25 While research into these biomarkers is ongoing, none have been studied in prospective trials, and they are not for use in current clinical care.

Pelvic ultrasonography

Pelvic ultrasonography is a crucial part of PUL assessment. Transvaginal ultrasonography should be interpreted in the context of the estimated gestational age of the pregnancy and serial hCG values, if available; the patient’s symptoms; and the sensitivity of the ultrasonography equipment, which also may be affected by variables that can reduce visualization, such as uterine fibroids and obesity.

The “discriminatory zone” refers to the hCG value above which an IUP should be visualized by ultrasonography. Generally, with an hCG value of 1,500 to 2,000 mIU/mL or greater, an IUP is expected to be seen with transvaginal sonography.3,26 Many exceptions to the discriminatory zone have been reported, however, including multiple pregnancies, which will have a higher hCG value at an earlier gestational age. Even in singleton pregnancies, viable IUPs have been documented as developing from PULs with an elevated initial hCG value as high as 4,300 mIU/mL.27 The discriminatory zone may vary among clinical hCG assays, and it also is affected by the quality and modernity of the ultrasonography equipment as well as by the ultrasonography operator’s experience and skill.28,29

The estimated gestational age, based on either the last menstrual period or assisted reproduction procedure, provides a helpful data point to guide expectations for ultrasonography findings.30 Using transvaginal ultrasonography in a normally progressing IUP, a gestational sac—typically measuring 2 to 3 mm—should be visualized at 5 weeks.15,30 At approximately 5.5 weeks, a yolk sac measuring 3 to 5 mm should appear. At 6 weeks, an embryo with cardiac activity should be visualized.

In a pregnancy reliably dated beyond 5 weeks, the lack of an intrauterine gestational sac is suspicious for, but not diagnostic of, an EP. Conversely, the visualization of a gestational sac alone (without a yolk sac) is insufficient to definitively exclude an EP, since a small fluid collection in the endometrium (a “pseudosac”) can convincingly mimic the appearance of a gestational sac, and a follow-up ultrasonography should be performed in such cases.

Among patients without ultrasonographic evidence of an IUP, endometrial thickness has been posited as a way to differentiate between IUP and EP.31,32 Evidence suggests that an endometrial stripe of at least 8 to 10 mm may be somewhat predictive of an IUP, while endometrial thickness below 8 mm is more concerning for EP. This clinical variable, however, has been shown repeatedly to lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for IUP and should be considered only within the entire clinical context.

Continue to: Endometrial aspiration...

Endometrial aspiration

A persistently abnormal hCG trend and an ultrasonography without evidence of an IUP—particularly with an hCG value above the discriminatory zone and/or with reliable pregnancy dating beyond 5 to 6 weeks—is highly concerning for either a failing IUP or an EP. Once a viable desired IUP is excluded beyond reasonable doubt through these measures, endometrial aspiration to determine pregnancy location is a reasonable next step in PUL management.

Endometrial aspiration can identify a failing IUP by detection of trophoblasts or chorionic villi on pathology and/or by a decline of at least 15% in hCG, measured on the day of endometrial aspiration and again the following day. Endometrial aspiration is effective even in clinical care settings that do not have rapid pathologic analysis available, as hCG measurement before and within 24 hours after the procedure still can be performed.

Vacuum aspiration (electric or manual) in an operating room or office setting is an effective tool for diagnosing pregnancy location.33,34 The use of an endometrial Pipelle for endometrial sampling (typically used for an office endometrial biopsy to diagnose hyperplasia or malignancy) is insufficient for determining pregnancy location.35 For all patients managed with this protocol, the hCG value ideally should be followed until it is undetectable, regardless of whether an EP or failing IUP was diagnosed. In rare cases, an EP may be diagnosed by a late plateau in hCG values, following an initial decline consistent with a failing IUP.

Utility for diagnosis. Retrospective studies in patients with PUL following in vitro fertilization have established the utility of outpatient endometrial aspiration with a Karman cannula, followed by a repeat hCG measurement on the day after the procedure.34,36 These data demonstrate that between 42% and 69% of women were ultimately diagnosed with a failed IUP following endometrial aspiration, thereby sparing them unnecessary exposure to methotrexate.

A decline in hCG levels of at least 15% within 24 hours after the procedure indicates that a failed IUP is the most likely diagnosis and further intervention is not indicated (although falling hCG values should be monitored for confirmation); confirmatory pathology with chorionic villi or trophoblasts was present in less than half of these women and is not necessary to diagnose a failed IUP.36 Women diagnosed with a failed IUP after endometrial aspiration also benefitted from a shorter time to resolution of the nonviable pregnancy by approximately 2 weeks.36

Despite the efficacy of endometrial aspiration for the diagnosis of pregnancy location, recent data show that physicians have highly variable approaches to PUL with an hCG plateaued above the discriminatory zone: One-third would first perform endometrial aspiration, while one-third would give methotrexate without further diagnostics.37 Academic physicians were 4 times more likely to recommend endometrial aspiration.37

Presumed EP. Following endometrial aspiration, if pathology does not confirm an intrauterine gestation and the hCG fails to decline by at least 15%, the diagnosis of a presumed EP is made.

For stable patients with neither evidence of intra-abdominal bleeding nor contraindications to methotrexate (such as blood dyscrasias, hepatic or renal insufficiency, active pulmonary or peptic ulcer disease, breastfeeding, or a known intolerance to the medication), methotrexate is recommended for medical management.26 Following screening blood work that includes a complete blood count and liver function and renal function tests, the typical methotrexate dose is 50 mg/m2 of body surface area. The single-dose regimen entails checking hCG on the day of methotrexate administration and again on days 4 and 7 thereafter. A minimum decline in hCG of 15% between days 4 and 7 indicates successful treatment; if the hCG decline is below 15%, the patient should receive an additional dose of methotrexate.

There are several published alternative regimens for methotrexate administration, including 2-dose and multidose regimens; the 2-dose protocol (2 doses within 7 days) may be more effective in women with higher hCG (> 3,000 mIU/mL) or known adnexal mass.26,38

Continue to: Contraindications to methotrexate...

Contraindications to methotrexate. In addition to strict medical contraindications to methotrexate, relative contraindications that indicate a higher risk of methotrexate failure include the presence of fetal cardiac activity, EP mass greater than 4 cm, and serum hCG above 5,000 mIU/mL.26 Because of the potential risk of tubal rupture during medical management, relative contraindications also include patient inability to follow up as an outpatient and patient refusal of blood transfusion.26 Patients with contraindications to methotrexate, hemodynamic instability, ultrasonographic or clinical evidence of EP rupture, or those electing for surgical management may be managed with laparoscopy.11 Discussion of surgical management of EP is beyond the scope of this article.

Follow the hCG level. In patients with a failing IUP or an EP treated with methotrexate or salpingostomy, the hCG level should always be followed until it is negative, usually by weekly measurements once the diagnosis is made. In some cases, the hCG level may plateau after an initial decline, alerting the clinician to failed treatment for a known EP or the need for recategorization of a failed IUP as an EP.

CASE Concluded

The patient’s second and third hCG measurements at 2-day intervals were 1,903 mIU/mL (14% rise) and 2,264 mIU/mL (16% rise). At that point, a repeat transvaginal ultrasonography showed no IUP, adnexal mass, or free fluid. The patient was counseled for outpatient endometrial aspiration, which was performed using manual vacuum aspiration. The serum hCG level on the morning of the procedure was 2,420 mIU/mL. On postprocedure day 1, the serum hCG level fell to 1,615 mIU/mL, a 33% decline. The patient was counseled that this decline in hCG indicated a failing IUP. The final pathologic analysis was returned 3 days later, showing no evidence of trophoblasts and chorionic villi. Regardless, the diagnosis of failing IUP remained given the rapid hCG decline; the tissue from the disrupted failing IUP was likely very scant or simply not drawn into the cannula. Serum hCG levels repeated at weekly intervals revealed ongoing decline, and after 4 weeks, the serum hCG was negative.

In summary

For women diagnosed with PUL, the primary goal is to distinguish an IUP from an EP to reduce the risk of EP rupture through expeditious diagnosis and treatment. In women for whom the pregnancy is desired, distinguishing a viable IUP from a nonviable IUP or an EP is the more specific goal to avoid intervention on a viable IUP (with methotrexate or endometrial aspiration). In women with abnormal hCG trends and indeterminate ultrasonography results (particularly with a serum hCG above the discriminatory zone), outpatient endometrial aspiration is a highly effective way to determine pregnancy location, which dictates further treatment. ●

- Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T. Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:250-261.

- Kirk E, Condous G, Bourne T. Pregnancies of unknown location. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23:493-499.

- Carusi D. Pregnancy of unknown location: evaluation and management. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:95-100.

- Banerjee S, Aslam N, Zosmer N, et al. The expectant management of women with early pregnancy of unknown location. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;14:231-236.

- Cordina M, Schramm-Gajraj K, Ross JA, et al. Introduction of a single visit protocol in the management of selected patients with pregnancy of unknown location: a prospective study. BJOG. 2011;118:693-697.

- Mol BW, Hajenius PJ, Engelsbel S, et al. Serum human chorionic gonadotropin measurement in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy when transvaginal sonography is inconclusive. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:972-981.

- Kirk E, Condous G, Van Calster B, et al. Rationalizing the follow-up of pregnancies of unknown location. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1744-1750.

- Stulberg DB, Cain LR, Dahlquist I, et al. Ectopic pregnancy rates and racial disparities in the Medicaid population, 2004-2008. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1671-1676.

- Zeng MF, Li LM. Frozen blastocyst transfer reduces incidence of ectopic pregnancy compared with fresh blastocyst transfer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35:93-99.

- Farquhar CM. Ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 2005;366:583-591.

- Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:379-387.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Shojaei T, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a comprehensive analysis based on a large case-control, population-based study in France. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:185-194.

- Creanga AA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Bish CL, et al. Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:837-843.

- Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:366-373.

- Brady PC. Handbook of Consult and Inpatient Gynecology. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Fridman D, Hawkins E, Dar P, et al. Methotrexate administration to patients with presumed ectopic pregnancy leads to methotrexate exposure of intrauterine pregnancies. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:675-684.

- Nurmohamed L, Moretti ME, Schechter T, et al. Outcome following high-dose methotrexate in pregnancies misdiagnosed as ectopic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:533.e1-533.e3.

- Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Rinaudo PF, et al. Symptomatic patients with an early viable intrauterine pregnancy: hCG curves redefined. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:50-55.

- Morse CB, Sammel MD, Shaunik A, et al. Performance of human chorionic gonadotropin curves in women at risk for ectopic pregnancy: exceptions to the rules. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:101-6.e2.

- Barnhart KT, Guo W, Cary MS, et al. Differences in serum human chorionic gonadotropin rise in early pregnancy by race and value at presentation. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:504-511.

- Barnhart K, Sammel MD, Chung K, et al. Decline of serum human chorionic gonadotropin and spontaneous complete abortion: defining the normal curve. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5, pt 1):975-981.

- Butts SF, Guo W, Cary MS, et al. Predicting the decline in human chorionic gonadotropin in a resolving pregnancy of unknown location. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):337-343.

- Verhaegen J, Gallos ID, van Mello NM, et al. Accuracy of single progesterone test to predict early pregnancy outcome in women with pain or bleeding: meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2012;345:e6077.

- Senapati S, Sammel MD, Butts SF, et al. Predicting first trimester pregnancy outcome: derivation of a multiple marker test. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:1725-1732.e3.

- Refaat B, Bahathiq AO. The performances of serum activins and follistatin in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy: a prospective case-control study. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;500:69-74.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:638-644.

- Doubilet PM, Benson CB. Further evidence against the reliability of the human chorionic gonadotropin discriminatory level. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:1637-1642.

- Desai D, Lu J, Wyness SP, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin discriminatory zone in ectopic pregnancy: does assay harmonization matter? Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1671-1674.

- Ko JK, Cheung VY. Time to revisit the human chorionic gonadotropin discriminatory level in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:465-471.

- Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1443-1451.

- Moschos E, Twickler DM. Endometrial thickness predicts intrauterine pregnancy in patients with pregnancy of unknown location. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:929-934.

- Ellaithy M, Abdelaziz A, Hassan MF. Outcome prediction in pregnancies of unknown location using endometrial thickness measurement: is this of real clinical value? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;168:68-74.

- Shaunik A, Kulp J, Appleby DH, et al. Utility of dilation and curettage in the diagnosis of pregnancy of unknown location. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:130.e1-130.e6.

- Brady P, Imudia AN, Awonuga AO, et al. Pregnancies of unknown location after in vitro fertilization: minimally invasive management with Karman cannula aspiration. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:420-426.

- Barnhart KT, Gracia CR, Reindl B, et al. Usefulness of pipelle endometrial biopsy in the diagnosis of women at risk for ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:906-909.

- Insogna IG, Farland LV, Missmer SA, et al. Outpatient endometrial aspiration: an alternative to methotrexate for pregnancy of unknown location. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:185.e1-185.e9.

- Parks MA, Barnhart KT, Howard DL. Trends in the management of nonviable pregnancies of unknown location in the United States. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2018;83:552-557.

- Alur-Gupta S, Cooney LG, Senapati S, et al. Two-dose versus single-dose methotrexate for treatment of ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:95-108.e2.

CASE Woman with bleeding in early pregnancy

A 31-year-old woman (G1P0) presents to the local emergency department (ED) due to bleeding in pregnancy. She reports a prior open appendectomy for ruptured appendix; she denies a history of sexually transmitted infections, smoking, and contraception use. She reports having regular menstrual cycles and trying to conceive with her husband for 18 months without success until now.

The patient reports that the previous week she took a home pregnancy test that was positive; she endorses having dark brown spotting for the past 2 days but denies pain. Based on the date of her last menstrual period, gestational age is estimated to be 5 weeks and 1 day. Her human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is 1,670 mIU/mL. Transvaginal ultrasonography demonstrates a normal uterus with an endometrial thickness of 10 mm, no evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), normal adnexa bilaterally, and scant free fluid in the pelvis.

Identifying and evaluating pregnancy of unknown location

A pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) is defined by a positive serum hCG level in the absence of a visualized IUP or ectopic pregnancy (EP) by pelvic ultrasonography.

Because of variations in screening tools and clinical practices between institutions and care settings (for example, EDs versus specialized outpatient offices), the incidence of PUL is difficult to capture. In specialized early pregnancy clinics, the rate is 8% to 10%, whereas in the ED setting, the PUL rate has been reported to be as high as 42%.1-6 While approximately 98% to 99% of all pregnancies are intrauterine, only 30% of PULs will continue to develop as viable ongoing intrauterine gestations.7-9 The remainder are revealed as failing IUPs or EPs. To counsel patients, set expectations, and triage to appropriate management, it is critical to diagnose pregnancy location as efficiently as possible.

Ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancies represent only 1% to 2% of conceptions (both spontaneous and through assisted reproduction) and occur most commonly in the fallopian tube, although EPs also can implant in the cornua of the uterus, the cervix, cesarean scar, and more rarely on the ovary or abdominal viscera.10,11 Least common, heterotopic pregnancies—in which an IUP coexists with an EP—occur in 1 in 4,000 to 30,000 pregnancies, more commonly in women who used assisted reproduction.11

Major risk factors for EP include a history of tubal surgery, sexually transmitted infections (particularly Chlamydia trachomatis), pelvic inflammatory disease, conception with an intrauterine device in situ, and a history of prior EP or tubal surgery, particularly prior tubal ligation; minor risk factors include a history of infertility (excluding known tubal factor infertility) or smoking (in a dose-dependent manner).11,12 The concern for an EP is heightened in patients with these risk factors.

Because of the possibility of rupture and life-threatening hemorrhage, EP carries a risk of significant morbidity and mortality.13 Ruptured EPs account for approximately 2.7% of all maternal deaths each year.14 When diagnosed sufficiently early in a stable patient, most EPs can be managed medically with methotrexate, a folic acid antagonist.15 Ectopic pregnancies also may be managed surgically, and emergency surgery is indicated in women with evidence of EP rupture and intraperitoneal bleeding.

Continue to: Intrauterine pregnancy...

Intrauterine pregnancy

While excluding EP is critical, it is equally important to diagnose an IUP as expeditiously as possible to avoid inadvertent, destructive intervention. Diagnosis and management of a PUL can involve endometrial aspiration, which would interrupt an IUP and should be avoided until the possibility of a viable IUP has been eliminated in desired pregnancies. The inadvertent administration of methotrexate, a known teratogen, to a patient with an undiagnosed viable IUP can result in miscarriage, elective termination, or a live-born infant with significant malformations, all of which expose the administering physician to malpractice litigation.16,17

In desired pregnancies, it is essential to differentiate between a viable IUP, a nonviable IUP, and an EP to guide appropriate management and ensure patient safety, whereas exclusion of EP is the priority in undesired pregnancies.

Tools for diagnosing pregnancy location

For diagnosing pregnancy location, serial hCG measurement, transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography, and outpatient endometrial aspiration are all relevant clinical tools. Pregnancy location can be diagnosed with either direct visualization of an IUP or EP by ultrasonography or with confirmed pathology (chorionic villi or trophoblast cells) from endometrial aspiration (FIGURE). A decline in hCG to an undetectable level following endometrial aspiration also is considered sufficient to diagnose a failed IUP, even in the absence of a confirmatory ultrasonography.

Trending hCG values

In stable patients with PUL, serum hCG levels are commonly measured at 2-day intervals, ideally for a minimum of 3 values. Conventional wisdom dictates that in viable IUPs, the hCG level should roughly double every 2 days. However, more recent data suggest that the threshold for minimum expected hCG rise for an ongoing IUP should be far lower when the pregnancy is desired.18 A less conservative cutoff can be considered when a pregnancy is not desired.

In a multisite cohort study of 1,005 women with PUL, a minimum hCG rise of 35% in 2 days captured the majority of IUPs, with a negative predictive value of 97.2% for IUP.19 Of note, although the cutoff of 35% was selected to reduce the risk of misdiagnosing an IUP as an EP, 7.7% of IUPs (and 16.8% of EPs) were still misclassified, showing that hCG trends must be interpreted in the context of other clinical data, including ultrasonography findings and patient symptoms and history.

A follow-up study demonstrated that hCG rises are lower (but still within this normal range) when the initial hCG value is higher, particularly greater than 3,000 mIU/mL.20

Studies show that the rate of spontaneous hCG decline in failing IUPs ranges from 12% to 47% in 2 days, falling more rapidly from higher starting hCG values.19,21 In a retrospective review of 443 women with spontaneously resolving PUL (presumed to be failing IUPs), the minimum 2-day decline in hCG was 35%.22 Any spontaneous hCG decline less than 35% in 2 days in a PUL should raise physician concern for EP.

Conversely, EPs do not demonstrate predictable hCG trends and can mimic the hCG trends of viable or failing IUPs. Although typically half of EPs present with an increasing hCG value and half present with a decreasing hCG value, the majority (71%) demonstrate a slower rate of change than either a viable IUP or a miscarriage.11 This slower change (plateau) should heighten the clinician’s suspicion for an EP.

Continue to: Progesterone levels...

Progesterone levels

A progesterone level often is used to attempt to determine pregnancy viability in women who are not receiving progesterone supplementation, although it ultimately has limited utility. While far less sensitive than an hCG value trend, a serum progesterone level of less than 5 to 10 ng/mL is a rough marker of nonviable pregnancy.23

In a large meta-analysis of women with pain and bleeding, 96.8% of pregnancies with a single progesterone level of less than 10 ng/mL were nonviable.23 When an inconclusive ultrasonography was documented in addition to symptoms of pain and bleeding, 99.2% of pregnancies with a progesterone level of less than 3.2 to 6 ng/mL were nonviable.

Progesterone’s usefulness in assessing for a PUL is limited: While progesterone levels may indicate nonviability, they provide no indication of pregnancy location (intrauterine or ectopic).

Alternative serologic markers

Various other reproductive and pregnancy-related hormones have been investigated for use in the diagnosis of pregnancy location in PULs, including activin A, inhibin A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A), placental-like growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, follistatin, and various microRNAs.24,25 While research into these biomarkers is ongoing, none have been studied in prospective trials, and they are not for use in current clinical care.

Pelvic ultrasonography

Pelvic ultrasonography is a crucial part of PUL assessment. Transvaginal ultrasonography should be interpreted in the context of the estimated gestational age of the pregnancy and serial hCG values, if available; the patient’s symptoms; and the sensitivity of the ultrasonography equipment, which also may be affected by variables that can reduce visualization, such as uterine fibroids and obesity.

The “discriminatory zone” refers to the hCG value above which an IUP should be visualized by ultrasonography. Generally, with an hCG value of 1,500 to 2,000 mIU/mL or greater, an IUP is expected to be seen with transvaginal sonography.3,26 Many exceptions to the discriminatory zone have been reported, however, including multiple pregnancies, which will have a higher hCG value at an earlier gestational age. Even in singleton pregnancies, viable IUPs have been documented as developing from PULs with an elevated initial hCG value as high as 4,300 mIU/mL.27 The discriminatory zone may vary among clinical hCG assays, and it also is affected by the quality and modernity of the ultrasonography equipment as well as by the ultrasonography operator’s experience and skill.28,29

The estimated gestational age, based on either the last menstrual period or assisted reproduction procedure, provides a helpful data point to guide expectations for ultrasonography findings.30 Using transvaginal ultrasonography in a normally progressing IUP, a gestational sac—typically measuring 2 to 3 mm—should be visualized at 5 weeks.15,30 At approximately 5.5 weeks, a yolk sac measuring 3 to 5 mm should appear. At 6 weeks, an embryo with cardiac activity should be visualized.

In a pregnancy reliably dated beyond 5 weeks, the lack of an intrauterine gestational sac is suspicious for, but not diagnostic of, an EP. Conversely, the visualization of a gestational sac alone (without a yolk sac) is insufficient to definitively exclude an EP, since a small fluid collection in the endometrium (a “pseudosac”) can convincingly mimic the appearance of a gestational sac, and a follow-up ultrasonography should be performed in such cases.

Among patients without ultrasonographic evidence of an IUP, endometrial thickness has been posited as a way to differentiate between IUP and EP.31,32 Evidence suggests that an endometrial stripe of at least 8 to 10 mm may be somewhat predictive of an IUP, while endometrial thickness below 8 mm is more concerning for EP. This clinical variable, however, has been shown repeatedly to lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for IUP and should be considered only within the entire clinical context.

Continue to: Endometrial aspiration...

Endometrial aspiration

A persistently abnormal hCG trend and an ultrasonography without evidence of an IUP—particularly with an hCG value above the discriminatory zone and/or with reliable pregnancy dating beyond 5 to 6 weeks—is highly concerning for either a failing IUP or an EP. Once a viable desired IUP is excluded beyond reasonable doubt through these measures, endometrial aspiration to determine pregnancy location is a reasonable next step in PUL management.

Endometrial aspiration can identify a failing IUP by detection of trophoblasts or chorionic villi on pathology and/or by a decline of at least 15% in hCG, measured on the day of endometrial aspiration and again the following day. Endometrial aspiration is effective even in clinical care settings that do not have rapid pathologic analysis available, as hCG measurement before and within 24 hours after the procedure still can be performed.

Vacuum aspiration (electric or manual) in an operating room or office setting is an effective tool for diagnosing pregnancy location.33,34 The use of an endometrial Pipelle for endometrial sampling (typically used for an office endometrial biopsy to diagnose hyperplasia or malignancy) is insufficient for determining pregnancy location.35 For all patients managed with this protocol, the hCG value ideally should be followed until it is undetectable, regardless of whether an EP or failing IUP was diagnosed. In rare cases, an EP may be diagnosed by a late plateau in hCG values, following an initial decline consistent with a failing IUP.

Utility for diagnosis. Retrospective studies in patients with PUL following in vitro fertilization have established the utility of outpatient endometrial aspiration with a Karman cannula, followed by a repeat hCG measurement on the day after the procedure.34,36 These data demonstrate that between 42% and 69% of women were ultimately diagnosed with a failed IUP following endometrial aspiration, thereby sparing them unnecessary exposure to methotrexate.

A decline in hCG levels of at least 15% within 24 hours after the procedure indicates that a failed IUP is the most likely diagnosis and further intervention is not indicated (although falling hCG values should be monitored for confirmation); confirmatory pathology with chorionic villi or trophoblasts was present in less than half of these women and is not necessary to diagnose a failed IUP.36 Women diagnosed with a failed IUP after endometrial aspiration also benefitted from a shorter time to resolution of the nonviable pregnancy by approximately 2 weeks.36

Despite the efficacy of endometrial aspiration for the diagnosis of pregnancy location, recent data show that physicians have highly variable approaches to PUL with an hCG plateaued above the discriminatory zone: One-third would first perform endometrial aspiration, while one-third would give methotrexate without further diagnostics.37 Academic physicians were 4 times more likely to recommend endometrial aspiration.37

Presumed EP. Following endometrial aspiration, if pathology does not confirm an intrauterine gestation and the hCG fails to decline by at least 15%, the diagnosis of a presumed EP is made.