User login

Rural areas with local obstetrical care have better perinatal outcomes

according to a retrospective study using county-level data from the Alabama Department of Public Health.

Although association does not establish causation, these data raise concern “for the current trend of diminishing L&D units that is occurring in many rural settings,” according to the authors of the study, led by John B. Waits, MD, of Cahaba Medical Care, Centreville, Ala., in Annals of Family Medicine.

When mortality per 1,000 live births was compared over a 15-year period (2003-2017) between 15 counties with and 21 counties without local L&D units, those with the units had lower overall infant mortality (9.23 vs. 7.89; P = .0011), perinatal mortality (8.89 vs. 10.82; P < .001), and neonatal mortality (4.74 vs. 5.67; P = .0034). The percentages of low-birth-weight babies born between 2003 and 2014 were 9.86% versus 10.61% (P < .001) for counties with and without L&D units, respectively.

The relative increased risks (RR) for these adverse outcomes in counties without L&D units were statistically significant and substantial, ranging from about 8% for a pregnancy resulting in a low-birth-weight infant to slightly more than 21% for perinatal mortality.

Over the study period, there were 165,525 live births in the 15 counties with L&D units and 72,177 births in the 21 counties with no such units. In counties without L&D units, the average proportion of White people was higher (73.47% vs. 60.86%), and that of African Americans was lower (22.76% vs. 36.23%). Median income ($40,759 vs. $35,604) and per capita income ($22,474 vs. $20,641) was slightly higher.

Of the 67 counties in Alabama, this study did not include those considered urbanized by the Alabama Office of Management and Budget even if classified rural by other statewide offices, such as the Alabama Rural Health Association. Any county with at least one L&D unit was considered to have a local unit. Three counties with L&D units that closed before the observation period was completed were excluded from the analysis.

The Alabama data appear to identify a major problem in need of an urgent solution, according to John S. Cullen, MD, a family physician in Valdez, Alaska, and chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians Board of Directors.

“Almost 20% of U.S. women of reproductive age live in rural communities,” he said in an interview. The data from this study provides compelling evidence “that the loss of rural maternity care in this country has contributed to the increase in newborn mortality in rural communities.”

There are many limitations for this study, according to the authors. They acknowledged that they could not control for many potentially important variables, such as travel time to hospitals for those in counties with L&D units when compared with those without. They also acknowledged the lack of data regarding availability of prenatal care in places with or without L&D units.

If lack of L&D services in rural areas is a source of adverse outcomes, data suggesting that the ongoing decline in L&D units are worrisome, according to the authors. Of studies they cited, one showed nearly a 10% loss in rural L&D services in a recent 10-year period.

The authors also noted that about half of the 3,143 counties in the United States do not have a practicing obstetrician, and that fewer than 7% of obstetricians-gynecologists practice in rural settings.

In many rural counties, including the county where the lead author practices, family practitioners provide 100% of local obstetric care, but access to these clinicians also appears to be declining, according to the paper. The ratio of primary care physicians to patients is already lower in non-metropolitan than metropolitan areas (39.8 vs. 53.3). The American Board of Family Medicine has reported that fewer than 10% of family physicians now provide maternity care, the authors wrote.

“If a causal relationship does exist [between lack of L&D units and adverse perinatal outcomes], then rural populations would definitively benefit from having local access to a L&D unit,” the authors stated.

The lead author, Dr. Waits, said in an interview that there are two obstacles to an increase in rural L&D units: malpractice premiums and reimbursement for indigent deliveries. The large malpractice premiums required to cover OB care are hurdles for caregivers, such as family physicians, as well as the hospitals where they practice.

Reforms from the legislative or regulatory perspective are needed to permit malpractice insurance to be issued at a reasonable cost, according to Dr. Waits. Such reforms are a “moral imperative” so that the malpractice issue is not allowed to “shipwreck infant and maternal mortality,” he said.

Of the many potential solutions, such as increased use of telemedicine, legislative initiatives to reduce the malpractice burden, or new support and incentives for family physicians to deliver OB care, each is burdened with obstacles to overcome, according to Dr. Waits. This does not mean these solutions should not be pursued alone or together, but he made it clear that the no solution is easy. In the meantime, Dr. Waits indicated a need to consider practical and immediate strategies to fix the problem.

“There should be incentives for rural emergency departments and ambulance systems to train in the [American Academy of Family Physicians’] Basic Life Support in Obstetrics (BLSO) certification courses each year. I am not aware of any specific evidence around this, but it is a known fact that, when L&Ds close, institutional memory of OB emergencies recede, and preparedness suffers,” he said.

Dr. Cullen agreed that if the closing of L&D units explains the higher rate of perinatal mortality in rural areas, both short-term and long-term solutions are needed.

“Every community must have a plan for obstetric and newborn emergencies. The decision to not offer maternity care means that rural providers will still provide maternity care but not be ready for emergencies,” he said, echoing a point made by Dr. Waits.

The study authors disclosed no conflicts. Dr. Cullen reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Waits JB et al. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:446-51.

according to a retrospective study using county-level data from the Alabama Department of Public Health.

Although association does not establish causation, these data raise concern “for the current trend of diminishing L&D units that is occurring in many rural settings,” according to the authors of the study, led by John B. Waits, MD, of Cahaba Medical Care, Centreville, Ala., in Annals of Family Medicine.

When mortality per 1,000 live births was compared over a 15-year period (2003-2017) between 15 counties with and 21 counties without local L&D units, those with the units had lower overall infant mortality (9.23 vs. 7.89; P = .0011), perinatal mortality (8.89 vs. 10.82; P < .001), and neonatal mortality (4.74 vs. 5.67; P = .0034). The percentages of low-birth-weight babies born between 2003 and 2014 were 9.86% versus 10.61% (P < .001) for counties with and without L&D units, respectively.

The relative increased risks (RR) for these adverse outcomes in counties without L&D units were statistically significant and substantial, ranging from about 8% for a pregnancy resulting in a low-birth-weight infant to slightly more than 21% for perinatal mortality.

Over the study period, there were 165,525 live births in the 15 counties with L&D units and 72,177 births in the 21 counties with no such units. In counties without L&D units, the average proportion of White people was higher (73.47% vs. 60.86%), and that of African Americans was lower (22.76% vs. 36.23%). Median income ($40,759 vs. $35,604) and per capita income ($22,474 vs. $20,641) was slightly higher.

Of the 67 counties in Alabama, this study did not include those considered urbanized by the Alabama Office of Management and Budget even if classified rural by other statewide offices, such as the Alabama Rural Health Association. Any county with at least one L&D unit was considered to have a local unit. Three counties with L&D units that closed before the observation period was completed were excluded from the analysis.

The Alabama data appear to identify a major problem in need of an urgent solution, according to John S. Cullen, MD, a family physician in Valdez, Alaska, and chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians Board of Directors.

“Almost 20% of U.S. women of reproductive age live in rural communities,” he said in an interview. The data from this study provides compelling evidence “that the loss of rural maternity care in this country has contributed to the increase in newborn mortality in rural communities.”

There are many limitations for this study, according to the authors. They acknowledged that they could not control for many potentially important variables, such as travel time to hospitals for those in counties with L&D units when compared with those without. They also acknowledged the lack of data regarding availability of prenatal care in places with or without L&D units.

If lack of L&D services in rural areas is a source of adverse outcomes, data suggesting that the ongoing decline in L&D units are worrisome, according to the authors. Of studies they cited, one showed nearly a 10% loss in rural L&D services in a recent 10-year period.

The authors also noted that about half of the 3,143 counties in the United States do not have a practicing obstetrician, and that fewer than 7% of obstetricians-gynecologists practice in rural settings.

In many rural counties, including the county where the lead author practices, family practitioners provide 100% of local obstetric care, but access to these clinicians also appears to be declining, according to the paper. The ratio of primary care physicians to patients is already lower in non-metropolitan than metropolitan areas (39.8 vs. 53.3). The American Board of Family Medicine has reported that fewer than 10% of family physicians now provide maternity care, the authors wrote.

“If a causal relationship does exist [between lack of L&D units and adverse perinatal outcomes], then rural populations would definitively benefit from having local access to a L&D unit,” the authors stated.

The lead author, Dr. Waits, said in an interview that there are two obstacles to an increase in rural L&D units: malpractice premiums and reimbursement for indigent deliveries. The large malpractice premiums required to cover OB care are hurdles for caregivers, such as family physicians, as well as the hospitals where they practice.

Reforms from the legislative or regulatory perspective are needed to permit malpractice insurance to be issued at a reasonable cost, according to Dr. Waits. Such reforms are a “moral imperative” so that the malpractice issue is not allowed to “shipwreck infant and maternal mortality,” he said.

Of the many potential solutions, such as increased use of telemedicine, legislative initiatives to reduce the malpractice burden, or new support and incentives for family physicians to deliver OB care, each is burdened with obstacles to overcome, according to Dr. Waits. This does not mean these solutions should not be pursued alone or together, but he made it clear that the no solution is easy. In the meantime, Dr. Waits indicated a need to consider practical and immediate strategies to fix the problem.

“There should be incentives for rural emergency departments and ambulance systems to train in the [American Academy of Family Physicians’] Basic Life Support in Obstetrics (BLSO) certification courses each year. I am not aware of any specific evidence around this, but it is a known fact that, when L&Ds close, institutional memory of OB emergencies recede, and preparedness suffers,” he said.

Dr. Cullen agreed that if the closing of L&D units explains the higher rate of perinatal mortality in rural areas, both short-term and long-term solutions are needed.

“Every community must have a plan for obstetric and newborn emergencies. The decision to not offer maternity care means that rural providers will still provide maternity care but not be ready for emergencies,” he said, echoing a point made by Dr. Waits.

The study authors disclosed no conflicts. Dr. Cullen reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Waits JB et al. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:446-51.

according to a retrospective study using county-level data from the Alabama Department of Public Health.

Although association does not establish causation, these data raise concern “for the current trend of diminishing L&D units that is occurring in many rural settings,” according to the authors of the study, led by John B. Waits, MD, of Cahaba Medical Care, Centreville, Ala., in Annals of Family Medicine.

When mortality per 1,000 live births was compared over a 15-year period (2003-2017) between 15 counties with and 21 counties without local L&D units, those with the units had lower overall infant mortality (9.23 vs. 7.89; P = .0011), perinatal mortality (8.89 vs. 10.82; P < .001), and neonatal mortality (4.74 vs. 5.67; P = .0034). The percentages of low-birth-weight babies born between 2003 and 2014 were 9.86% versus 10.61% (P < .001) for counties with and without L&D units, respectively.

The relative increased risks (RR) for these adverse outcomes in counties without L&D units were statistically significant and substantial, ranging from about 8% for a pregnancy resulting in a low-birth-weight infant to slightly more than 21% for perinatal mortality.

Over the study period, there were 165,525 live births in the 15 counties with L&D units and 72,177 births in the 21 counties with no such units. In counties without L&D units, the average proportion of White people was higher (73.47% vs. 60.86%), and that of African Americans was lower (22.76% vs. 36.23%). Median income ($40,759 vs. $35,604) and per capita income ($22,474 vs. $20,641) was slightly higher.

Of the 67 counties in Alabama, this study did not include those considered urbanized by the Alabama Office of Management and Budget even if classified rural by other statewide offices, such as the Alabama Rural Health Association. Any county with at least one L&D unit was considered to have a local unit. Three counties with L&D units that closed before the observation period was completed were excluded from the analysis.

The Alabama data appear to identify a major problem in need of an urgent solution, according to John S. Cullen, MD, a family physician in Valdez, Alaska, and chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians Board of Directors.

“Almost 20% of U.S. women of reproductive age live in rural communities,” he said in an interview. The data from this study provides compelling evidence “that the loss of rural maternity care in this country has contributed to the increase in newborn mortality in rural communities.”

There are many limitations for this study, according to the authors. They acknowledged that they could not control for many potentially important variables, such as travel time to hospitals for those in counties with L&D units when compared with those without. They also acknowledged the lack of data regarding availability of prenatal care in places with or without L&D units.

If lack of L&D services in rural areas is a source of adverse outcomes, data suggesting that the ongoing decline in L&D units are worrisome, according to the authors. Of studies they cited, one showed nearly a 10% loss in rural L&D services in a recent 10-year period.

The authors also noted that about half of the 3,143 counties in the United States do not have a practicing obstetrician, and that fewer than 7% of obstetricians-gynecologists practice in rural settings.

In many rural counties, including the county where the lead author practices, family practitioners provide 100% of local obstetric care, but access to these clinicians also appears to be declining, according to the paper. The ratio of primary care physicians to patients is already lower in non-metropolitan than metropolitan areas (39.8 vs. 53.3). The American Board of Family Medicine has reported that fewer than 10% of family physicians now provide maternity care, the authors wrote.

“If a causal relationship does exist [between lack of L&D units and adverse perinatal outcomes], then rural populations would definitively benefit from having local access to a L&D unit,” the authors stated.

The lead author, Dr. Waits, said in an interview that there are two obstacles to an increase in rural L&D units: malpractice premiums and reimbursement for indigent deliveries. The large malpractice premiums required to cover OB care are hurdles for caregivers, such as family physicians, as well as the hospitals where they practice.

Reforms from the legislative or regulatory perspective are needed to permit malpractice insurance to be issued at a reasonable cost, according to Dr. Waits. Such reforms are a “moral imperative” so that the malpractice issue is not allowed to “shipwreck infant and maternal mortality,” he said.

Of the many potential solutions, such as increased use of telemedicine, legislative initiatives to reduce the malpractice burden, or new support and incentives for family physicians to deliver OB care, each is burdened with obstacles to overcome, according to Dr. Waits. This does not mean these solutions should not be pursued alone or together, but he made it clear that the no solution is easy. In the meantime, Dr. Waits indicated a need to consider practical and immediate strategies to fix the problem.

“There should be incentives for rural emergency departments and ambulance systems to train in the [American Academy of Family Physicians’] Basic Life Support in Obstetrics (BLSO) certification courses each year. I am not aware of any specific evidence around this, but it is a known fact that, when L&Ds close, institutional memory of OB emergencies recede, and preparedness suffers,” he said.

Dr. Cullen agreed that if the closing of L&D units explains the higher rate of perinatal mortality in rural areas, both short-term and long-term solutions are needed.

“Every community must have a plan for obstetric and newborn emergencies. The decision to not offer maternity care means that rural providers will still provide maternity care but not be ready for emergencies,” he said, echoing a point made by Dr. Waits.

The study authors disclosed no conflicts. Dr. Cullen reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Waits JB et al. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:446-51.

FROM ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The absence of labor and delivery (L&D) services in rural counties predicts adverse outcomes, including higher child mortality.

Major finding: In the absence of L&D units, the risk of perinatal mortality per 1,000 live births is 19% higher (5.67 vs. 4.74; P = .0034).

Data Source: Retrospective cohort study.

Disclosures: Potential conflicts of interest involving this topic were not reported.

Source: Waits JB et al. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:446-51.

How to build your identity as a physician online

To have a thriving business in today’s world, a functioning website is crucial to the overall business health. For a medical practice in general, and for its physicians specifically, it is one of the first steps for maintaining a practice. But to grow that practice, it is crucial to take the steps beyond just having a website. Growth requires website optimization for search engines, an expanding referral base, and the knowledge to use web tools and social media at your disposal to promote the practice and its physicians. In this roundtable, several marketing experts and web-savvy physicians discuss using available tools to best position and grow a practice.

Choosing a web upgrade

Patrick J. Culligan, MD: Peter, can you start us off by describing your relationship with Heather, and how your practice benefitted from her expertise?

Peter M. Lotze, MD: Sure. I am a urogynecologist in the competitive market of pelvic reconstructive surgery in Houston, Texas. Within that market, my main approach was to reach out to other physicians to refer patients to my practice. It generally would work, but took increasingly greater amounts of time to call these physicians up, write them letters, and maintain relationships. I felt that the large, national practice group that I am in did not have a significant web presence optimized to promote my practice, which makes it difficult for patients seeking your services to find you in their search for a doctor. It is helpful for patients to be able to understand from your website who you are, what you do, and what their experience may be like.

Glaring to me was that a web search specific for me or things that I do, would not produce our company’s results until page 2 or more on Google. This can be devastating for a practice because most people don’t go past the first page, and you can end up with fewer self-referrals, which should be a significant portion of new patients to your practice. I knew I needed guidance; I knew of Heather’s expertise given her exceptional past work building marketing strategies.

Digital go-tos for marketing

Heather Schueppert: Yes, I was pleased to work with Dr. Lotze, and at the time was a marketing consultant for practices such as his. But gone are the days of printed material—brochures, pamphlets, or even billboards—to effectively promote a business, or in this case, a practice. What still withstands the test of time, however, as the number 1 marketing referral source is word of mouth—from your trusted friend, family member, or coworker.

It is now proven that the number 2 most trusted form of advertising, the most persuasive and the most motivating, is online marketing.1 It is the “digital word of mouth”—the review. Patients are actively online, and a strong digital presence is critical to provide that direct value to retain and grow your patient base.

Continue to: Foundations of private practice reach out...

Foundations of private practice reach out

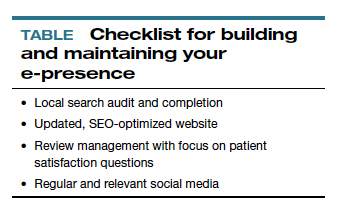

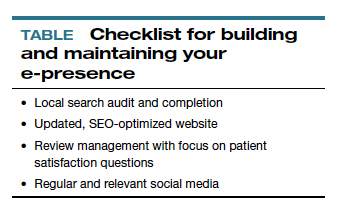

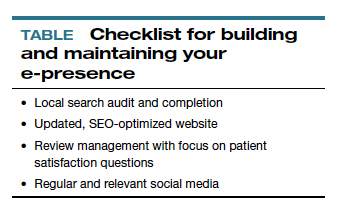

There are 3 important areas that I consider the foundation of any private practice marketing strategy (TABLE). First is an updated website that is search engine optimized (SEO). You can’t just set it and forget it, it needs to be an updated website. The algorithms for search engines are changing constantly to try to make it as fair and relevant as possible for patients or consumers to find the businesses they are searching for online.

The second area is review management, and for a physician, or even a care center, to do this on your own is a daunting task. It is a critical component, however, to making sure that your reputation out there, that online word of mouth, is as high a star rating as possible.

The third component is local search, which is basically a form of SEO that helps businesses show up in relevant local searches. We are all familiar with the search, “find a restaurant near me,” anything that pushes those search engines to find something local.

Those are what I call the effective triad: that updated website, the review management, and the local search, and all of these are tied together. I think Dr. Lotze and his practice did these effectively well, and I believe that he achieved his goals for the longer term.

Review/reputation management

Dr. Culligan: Brad, is there something that doctors may not know about Healthgrades, and are there opportunities to take full advantage of this physician-rating site?

Brad Bowman, MD: I agree with everything that Dr. Lotze and Heather have said. Start with yourself—what is it that you want to be, the one thing you want to stand for? Get your own marketing, your website right, then, the point is, once you do all that and you are number 1 in SEO, you are still only going to get about 25% of the people looking for you by name to come to your website. The other 75% are going to look at all the other different sites that are out there to provide information to consumers. So the question becomes what do you do with all these other third-party sites? Healthgrades is the most comprehensive and has the highest traffic of the third-party “find a doctor” sites. In 2020, half of all Americans who go to a doctor will use Healthgrades at some point to help select and connect with that doctor.

Physicians have their focus on the quality of the care they provide. Patients, however, focus on the quality of the entire health care experience. Did I get better? How long did I have to wait? Was the office staff helpful? Scarily enough, we still spend more time shopping for a refrigerator or mattress than we do shopping for a doctor. We still tend to think that all doctors are the same. It is the reality of how we have been trained by our insurance companies and by the health care system. That is why getting your marketing right and getting what is it that you want to be known for out there is important, so that you can get the types of patients you want.

Listings management is very important. Make sure that you are findable everywhere. There are services that will do this: Doctor.com, Reputation.com, and many others. They can help you make sure you get all your basic materials right: addresses, phone numbers, your picture. Because 75% of people are going to end up on third-party websites, if your phone number is wrong there, you could lose that patient.

Then the second piece of working with third-party sites is reputation management. Physician reviews are not a bad thing, they are the new word of mouth, as Heather pointed out. Most (80%) of the reviews are going to be positive. The others will be negative, and that is okay. It is important that you get at least 1 or 2 reviews on all the different sites. We know from Healthgrades.com that going from zero reviews to 1 review will increase your call volume by 60%. If you have the choice between 2 physicians and one practice looks like people have been there before, you will go to that one.

You can learn from reviews as well, consumers provide valid feedback. Best practice is to respond to every positive and negative review. Thank them, indicate that you have listened to them, and address any concerns as necessary.

Continue to: Dr. Lotze...

Dr. Lotze: As an example, one of the paramount things that Heather introduced me to was the third party I use to run my website. That company sends a HIPAA-compliant review out to each patient we have seen that day and gives them the opportunity to rate our services and leave comments. If a patient brings up a concern, we can respond immediately, which is important. Patients appreciate feeling that they have been heard. Typically, communicating with a patient will turn the 3-star review into a 5-star as she follows up with the practice.

Ms. Schueppert: Timeliness is important. And just to mention, there certainly is a time commitment to this (and it is a marathon versus a sprint) and there is some financial investment to get it going, but it could truly be detrimental to a practice if you decide not to do anything at all.

Dr. Bowman: Agencies can really help with the time commitment.

Handling bad reviews

Dr. Culligan: What about that person who seems to have it out for you, perhaps giving you multiple bad reviews?

Dr. Bowman: I have seen this before. At Healthgrades, we recently analyzed 8.4 million patient reviews to see what people wrote about.2 The first thing they will talk about is quality of care as they see it. Did I get better or not? You can’t “fix” every patient; there will be some that you cannot help. The next thing patients comment on is bedside manner. With negative reviews, you will see more comments about the office staff.2

A single negative review actually helps make the positive ones look more credible. But if you do believe someone is trolling you, we can flag it and will investigate to the best of our ability. (Different sites likely have different editorial policies.) For example, we look at the IP addresses of all reviews, and if multiple reviews are coming from the same location, we would only let one through, overwriting the previous review from that address.

Patients just want to be heard. We have seen people change their views, based on how their review is handled and responded to.

Dr. Lotze: Is there a response by the physician that you think tends to work better in terms of resolving the issue that can minimize a perceived caustic reaction to a patient’s criticism?

Dr. Bowman: First, just like with any stressful situation, take a deep breath and respond when you feel like you can be constructive. When you do respond, be gracious. Thank them for their feedback. Make sure you reference something about their concern: “I understand that you had to wait longer than you would have liked.” Acknowledge the problem they reference, and then just apologize: “I’m sorry we didn’t meet your expectations.” Then, if they waited too long for example, “We have a new system where no one should have to wait more than 30 minutes….” You can respond privately or publically. Generally, public responses are better as it shows other consumers that you are willing to listen and consider their point of view.

Continue to: The next phase at Healthgrades...

The next phase at Healthgrades

Dr. Culligan: Do you see changes to the way physician-rating sites are working now? Are we going to stay status quo over the next 10 years, or do you see frontiers in how your site is going to develop?

Dr. Bowman: For Healthgrades, we rely on quantitative and objective measures, not just the qualitative. We are investing heavily right now in trying to help consumers understand what are the relative volumes of different procedures or different patient types that each individual doctor sees. Orthopedics is an easy example—if you have a knee problem, you want to go to someone who specializes in knees. Our job is to help consumers easily identify, “This is a shoulder doctor, this is a knee doctor, and this is why that matters.”

In the meantime, as a physician, you can always go into our site and state your care philosophy, identifying what is the sort of patient that you like to treat. Transparency is good for everyone, and especially physicians. It helps the right patient show up for you, and it helps you do a better job providing referrals.

Social media: Avoid pitfalls, and use it to your benefit

Dr. Lotze: Branding was one of the things that I was confused about, and Heather really helped me out. As physicians, we put ourselves out there on our websites, which we try to make professional sources of information for patients. But patients often want to see what else they can find out about us, including Healthgrades and social media. I think the thing that is important to know with social media is that it is a place where people learn about you as a person. Your social media should be another avenue of promotion. Whether it is your personal or professional Facebook page, people are going to see those sites. You have an opportunity to promote yourself as a good physician and a good person with a wholesome practice that you want people to come to. If a physician is posting questionable things about themselves on any kind of social media, it could be perceived as inappropriate by the patient. That can impact how patients think of you as a person, and how they are going to grade you. If people lose sight of who you are due to a questionable social media posting, everything else (SEO, the website) can be for naught.

Dr. Culligan: What are the most important social media tools to invest your time in?

Ms. Schueppert: Before anybody jumps into social media, I firmly recommend that you make sure your local search and your Google 3-pack is set up—which is basically a method Google uses to display the top 3 results on its listings page. Then make sure you have a review management system in place. Make sure you have that updated website. Those are the foundational elements. Once you have that going, social media is the next added layer to that digital presence.

I usually recommend LinkedIn. It is huge because you are staying in contact with your colleagues, that business-to-business type of connection. It remains a way for physicians to set themselves up as experts in their level of specialty.

From there, it’s either Instagram or Facebook. If you are serving more of the younger generations, the millennials and younger, then Instagram is the way to go. If you are focusing on your 40+, 50+, they are going to be far more on Facebook.

Continue to: Dr. Lotze...

Dr. Lotze: For me, a Facebook page was a great place to start. The cost of those Google ads—the first things we see at the top of a Google search in their own separate box—is significant. If a practice has that kind of money to invest, great; it is an instant way to be first on the page during a search. But there are more cost-effective ways of doing that, especially as you are getting your name out. Facebook provides, at a smaller cost, promotion of whatever it is that you are seeking to promote. You can find people within a certain zip code, for instance, and use a Facebook ad campaign that can drive people to your Facebook page—which should have both routinely updated new posts and a link to your website. The posts should be interesting topics relevant to the patients you wish to treat (avoiding personal stories or controversial discussions). You can put a post together, or you can have a third-party service do this. People who follow your page will get reminders of you and your practice with each new post. As your page followers increase, your Facebook rank will improve, and your page will more likely be discovered by Facebook searches for your services. With an added link to your office practice website, those patients go straight to your site without getting lost in the noise of Google search results.

For Instagram, a short video or an interesting picture, along with a brief statement, are the essentials. You can add a single link. Marketing here is by direct messaging or having patients going to your website through a link. Instagram, like Facebook, offers analytics to help show you what your audience likes to read about, improving the quality of your posts and increasing number of followers.

YouTube is the number 2 search engine behind Google. A Google search for your field of medicine may be filled with pages of competitors. However, YouTube has a much lower volume of competing practices, making it easier for patients to find you. The only downside to YouTube is that it will list your video along with other competing videos, which can draw attention away from your practice.

If you want to promote your website or practice with video, using a company such as Vimeo is a better choice compared with YouTube, as YouTube gets credit for video views—which improves YouTube’s SEO and not your own website. Vimeo allows for your website to get credit each time the video is watched. Regardless of where you place your videos, make them short and to the point, with links to your website. Videos only need to be long enough to get your message across and stimulate interest in your practice.

If you can have a blog on your website, it also will help with SEO. What a search engine like Google wants to see is that a patient is on your web page and looking at something for at least 60 seconds. If so, the website is deemed to have information that is relevant, improving your SEO ranking.

Finally, Twitter also can be used for getting messaging out and for branding. The problem with it is that many people go to Twitter to follow a Hollywood celebrity, a sports star, or are looking for mass communication. There is less interest on Twitter for physician outreach.

Continue to: Measuring ROI...

Measuring ROI

Dr. Culligan: What’s the best way to track your return on investment?

Dr. Lotze: First for me was to find out what didn’t work in the office and fix that before really promoting my practice. It’s about the global experience for a patient, as Brad mentioned. As a marketing expert, Heather met with me to understand my goals. She then called my office as a patient to set up an appointment and went through that entire office experience. We identified issues needing improvement.

The next step was to develop a working relationship with my webmaster—someone who can help manage Internet image and SEO. Together, you will develop goals for what the SEO should promote specific to your practice. Once a good SEO program is in place, your website’s ranking will go up—although it can take a minimum of 6 months to see a significant increase. To help understand your website’s performance, your webmaster should provide you with reports on your site’s analytics.

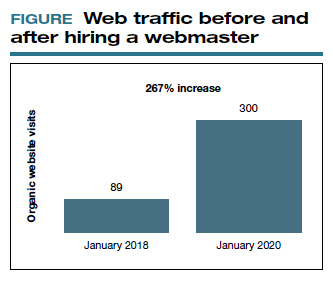

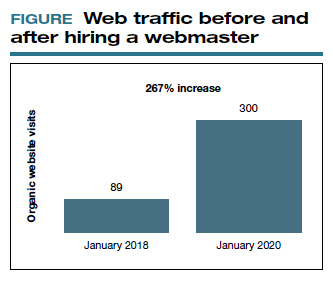

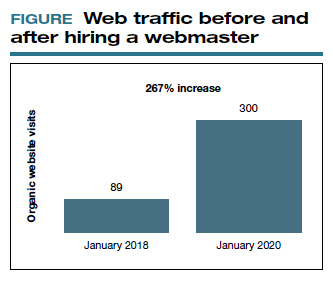

As you go through this process, it is great to have a marketing expert to be the point person. You will work closely together for a while, but eventually you can back off over time. The time and expense you invest on the front end have huge rewards on the back end. Currently, I still spend a reasonable amount of money every month. I have a high self-referral base because of these efforts, however, which results in more patient surgeries and easily covers my expenses. It is money well invested. My website traffic increased by 268% over 2 years (FIGURE). I’ll propose that currently more than half of my patients are self-referrals due to online marketing.

Ms. Schueppert: The only thing I would add is training your front staff. They are checking people in, taking appointments, checking your patients out. Have them be mindful that there are campaigns going on, whether it is a social media push, or a new video that went on the website. They can ask, “How did you hear about us?” when a new patient calls.

Dr. Bowman: Unless you are a large university hospital, where the analytics get significantly more advanced in terms of measuring return on investment (ROI), I think you should just be looking at your schedule and looking at your monthly billings and seeing how they change over time. You can calculate how much a new patient is worth because you can figure out how many patients you have and how much you bill and what your profits are.

Dr. Culligan: For those of us who are hospital employees, you can try to convince the hospital that you can do a detailed ROI analysis, or you can just look at it like (say it’s $3,000 per month), how many surgeries does this project have to generate before the hospital makes that back? The answer is a fraction of 1 case.

Thank you to all of you for your expertise on this roundtable.

- Anderson A. Online reviews vs. word of mouth: Which one is more important. https://www.revlocal.com/blog/reviewandreputationmanagement/onlinereviewsvswordofmouthwhichoneismoreimportant. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 2020 Patient sentiment report. Healthgrades; Medical Group Management Association. https://www.healthgrades.com/content /patientsentimentreport. Accessed July 17, 2020

To have a thriving business in today’s world, a functioning website is crucial to the overall business health. For a medical practice in general, and for its physicians specifically, it is one of the first steps for maintaining a practice. But to grow that practice, it is crucial to take the steps beyond just having a website. Growth requires website optimization for search engines, an expanding referral base, and the knowledge to use web tools and social media at your disposal to promote the practice and its physicians. In this roundtable, several marketing experts and web-savvy physicians discuss using available tools to best position and grow a practice.

Choosing a web upgrade

Patrick J. Culligan, MD: Peter, can you start us off by describing your relationship with Heather, and how your practice benefitted from her expertise?

Peter M. Lotze, MD: Sure. I am a urogynecologist in the competitive market of pelvic reconstructive surgery in Houston, Texas. Within that market, my main approach was to reach out to other physicians to refer patients to my practice. It generally would work, but took increasingly greater amounts of time to call these physicians up, write them letters, and maintain relationships. I felt that the large, national practice group that I am in did not have a significant web presence optimized to promote my practice, which makes it difficult for patients seeking your services to find you in their search for a doctor. It is helpful for patients to be able to understand from your website who you are, what you do, and what their experience may be like.

Glaring to me was that a web search specific for me or things that I do, would not produce our company’s results until page 2 or more on Google. This can be devastating for a practice because most people don’t go past the first page, and you can end up with fewer self-referrals, which should be a significant portion of new patients to your practice. I knew I needed guidance; I knew of Heather’s expertise given her exceptional past work building marketing strategies.

Digital go-tos for marketing

Heather Schueppert: Yes, I was pleased to work with Dr. Lotze, and at the time was a marketing consultant for practices such as his. But gone are the days of printed material—brochures, pamphlets, or even billboards—to effectively promote a business, or in this case, a practice. What still withstands the test of time, however, as the number 1 marketing referral source is word of mouth—from your trusted friend, family member, or coworker.

It is now proven that the number 2 most trusted form of advertising, the most persuasive and the most motivating, is online marketing.1 It is the “digital word of mouth”—the review. Patients are actively online, and a strong digital presence is critical to provide that direct value to retain and grow your patient base.

Continue to: Foundations of private practice reach out...

Foundations of private practice reach out

There are 3 important areas that I consider the foundation of any private practice marketing strategy (TABLE). First is an updated website that is search engine optimized (SEO). You can’t just set it and forget it, it needs to be an updated website. The algorithms for search engines are changing constantly to try to make it as fair and relevant as possible for patients or consumers to find the businesses they are searching for online.

The second area is review management, and for a physician, or even a care center, to do this on your own is a daunting task. It is a critical component, however, to making sure that your reputation out there, that online word of mouth, is as high a star rating as possible.

The third component is local search, which is basically a form of SEO that helps businesses show up in relevant local searches. We are all familiar with the search, “find a restaurant near me,” anything that pushes those search engines to find something local.

Those are what I call the effective triad: that updated website, the review management, and the local search, and all of these are tied together. I think Dr. Lotze and his practice did these effectively well, and I believe that he achieved his goals for the longer term.

Review/reputation management

Dr. Culligan: Brad, is there something that doctors may not know about Healthgrades, and are there opportunities to take full advantage of this physician-rating site?

Brad Bowman, MD: I agree with everything that Dr. Lotze and Heather have said. Start with yourself—what is it that you want to be, the one thing you want to stand for? Get your own marketing, your website right, then, the point is, once you do all that and you are number 1 in SEO, you are still only going to get about 25% of the people looking for you by name to come to your website. The other 75% are going to look at all the other different sites that are out there to provide information to consumers. So the question becomes what do you do with all these other third-party sites? Healthgrades is the most comprehensive and has the highest traffic of the third-party “find a doctor” sites. In 2020, half of all Americans who go to a doctor will use Healthgrades at some point to help select and connect with that doctor.

Physicians have their focus on the quality of the care they provide. Patients, however, focus on the quality of the entire health care experience. Did I get better? How long did I have to wait? Was the office staff helpful? Scarily enough, we still spend more time shopping for a refrigerator or mattress than we do shopping for a doctor. We still tend to think that all doctors are the same. It is the reality of how we have been trained by our insurance companies and by the health care system. That is why getting your marketing right and getting what is it that you want to be known for out there is important, so that you can get the types of patients you want.

Listings management is very important. Make sure that you are findable everywhere. There are services that will do this: Doctor.com, Reputation.com, and many others. They can help you make sure you get all your basic materials right: addresses, phone numbers, your picture. Because 75% of people are going to end up on third-party websites, if your phone number is wrong there, you could lose that patient.

Then the second piece of working with third-party sites is reputation management. Physician reviews are not a bad thing, they are the new word of mouth, as Heather pointed out. Most (80%) of the reviews are going to be positive. The others will be negative, and that is okay. It is important that you get at least 1 or 2 reviews on all the different sites. We know from Healthgrades.com that going from zero reviews to 1 review will increase your call volume by 60%. If you have the choice between 2 physicians and one practice looks like people have been there before, you will go to that one.

You can learn from reviews as well, consumers provide valid feedback. Best practice is to respond to every positive and negative review. Thank them, indicate that you have listened to them, and address any concerns as necessary.

Continue to: Dr. Lotze...

Dr. Lotze: As an example, one of the paramount things that Heather introduced me to was the third party I use to run my website. That company sends a HIPAA-compliant review out to each patient we have seen that day and gives them the opportunity to rate our services and leave comments. If a patient brings up a concern, we can respond immediately, which is important. Patients appreciate feeling that they have been heard. Typically, communicating with a patient will turn the 3-star review into a 5-star as she follows up with the practice.

Ms. Schueppert: Timeliness is important. And just to mention, there certainly is a time commitment to this (and it is a marathon versus a sprint) and there is some financial investment to get it going, but it could truly be detrimental to a practice if you decide not to do anything at all.

Dr. Bowman: Agencies can really help with the time commitment.

Handling bad reviews

Dr. Culligan: What about that person who seems to have it out for you, perhaps giving you multiple bad reviews?

Dr. Bowman: I have seen this before. At Healthgrades, we recently analyzed 8.4 million patient reviews to see what people wrote about.2 The first thing they will talk about is quality of care as they see it. Did I get better or not? You can’t “fix” every patient; there will be some that you cannot help. The next thing patients comment on is bedside manner. With negative reviews, you will see more comments about the office staff.2

A single negative review actually helps make the positive ones look more credible. But if you do believe someone is trolling you, we can flag it and will investigate to the best of our ability. (Different sites likely have different editorial policies.) For example, we look at the IP addresses of all reviews, and if multiple reviews are coming from the same location, we would only let one through, overwriting the previous review from that address.

Patients just want to be heard. We have seen people change their views, based on how their review is handled and responded to.

Dr. Lotze: Is there a response by the physician that you think tends to work better in terms of resolving the issue that can minimize a perceived caustic reaction to a patient’s criticism?

Dr. Bowman: First, just like with any stressful situation, take a deep breath and respond when you feel like you can be constructive. When you do respond, be gracious. Thank them for their feedback. Make sure you reference something about their concern: “I understand that you had to wait longer than you would have liked.” Acknowledge the problem they reference, and then just apologize: “I’m sorry we didn’t meet your expectations.” Then, if they waited too long for example, “We have a new system where no one should have to wait more than 30 minutes….” You can respond privately or publically. Generally, public responses are better as it shows other consumers that you are willing to listen and consider their point of view.

Continue to: The next phase at Healthgrades...

The next phase at Healthgrades

Dr. Culligan: Do you see changes to the way physician-rating sites are working now? Are we going to stay status quo over the next 10 years, or do you see frontiers in how your site is going to develop?

Dr. Bowman: For Healthgrades, we rely on quantitative and objective measures, not just the qualitative. We are investing heavily right now in trying to help consumers understand what are the relative volumes of different procedures or different patient types that each individual doctor sees. Orthopedics is an easy example—if you have a knee problem, you want to go to someone who specializes in knees. Our job is to help consumers easily identify, “This is a shoulder doctor, this is a knee doctor, and this is why that matters.”

In the meantime, as a physician, you can always go into our site and state your care philosophy, identifying what is the sort of patient that you like to treat. Transparency is good for everyone, and especially physicians. It helps the right patient show up for you, and it helps you do a better job providing referrals.

Social media: Avoid pitfalls, and use it to your benefit

Dr. Lotze: Branding was one of the things that I was confused about, and Heather really helped me out. As physicians, we put ourselves out there on our websites, which we try to make professional sources of information for patients. But patients often want to see what else they can find out about us, including Healthgrades and social media. I think the thing that is important to know with social media is that it is a place where people learn about you as a person. Your social media should be another avenue of promotion. Whether it is your personal or professional Facebook page, people are going to see those sites. You have an opportunity to promote yourself as a good physician and a good person with a wholesome practice that you want people to come to. If a physician is posting questionable things about themselves on any kind of social media, it could be perceived as inappropriate by the patient. That can impact how patients think of you as a person, and how they are going to grade you. If people lose sight of who you are due to a questionable social media posting, everything else (SEO, the website) can be for naught.

Dr. Culligan: What are the most important social media tools to invest your time in?

Ms. Schueppert: Before anybody jumps into social media, I firmly recommend that you make sure your local search and your Google 3-pack is set up—which is basically a method Google uses to display the top 3 results on its listings page. Then make sure you have a review management system in place. Make sure you have that updated website. Those are the foundational elements. Once you have that going, social media is the next added layer to that digital presence.

I usually recommend LinkedIn. It is huge because you are staying in contact with your colleagues, that business-to-business type of connection. It remains a way for physicians to set themselves up as experts in their level of specialty.

From there, it’s either Instagram or Facebook. If you are serving more of the younger generations, the millennials and younger, then Instagram is the way to go. If you are focusing on your 40+, 50+, they are going to be far more on Facebook.

Continue to: Dr. Lotze...

Dr. Lotze: For me, a Facebook page was a great place to start. The cost of those Google ads—the first things we see at the top of a Google search in their own separate box—is significant. If a practice has that kind of money to invest, great; it is an instant way to be first on the page during a search. But there are more cost-effective ways of doing that, especially as you are getting your name out. Facebook provides, at a smaller cost, promotion of whatever it is that you are seeking to promote. You can find people within a certain zip code, for instance, and use a Facebook ad campaign that can drive people to your Facebook page—which should have both routinely updated new posts and a link to your website. The posts should be interesting topics relevant to the patients you wish to treat (avoiding personal stories or controversial discussions). You can put a post together, or you can have a third-party service do this. People who follow your page will get reminders of you and your practice with each new post. As your page followers increase, your Facebook rank will improve, and your page will more likely be discovered by Facebook searches for your services. With an added link to your office practice website, those patients go straight to your site without getting lost in the noise of Google search results.

For Instagram, a short video or an interesting picture, along with a brief statement, are the essentials. You can add a single link. Marketing here is by direct messaging or having patients going to your website through a link. Instagram, like Facebook, offers analytics to help show you what your audience likes to read about, improving the quality of your posts and increasing number of followers.

YouTube is the number 2 search engine behind Google. A Google search for your field of medicine may be filled with pages of competitors. However, YouTube has a much lower volume of competing practices, making it easier for patients to find you. The only downside to YouTube is that it will list your video along with other competing videos, which can draw attention away from your practice.

If you want to promote your website or practice with video, using a company such as Vimeo is a better choice compared with YouTube, as YouTube gets credit for video views—which improves YouTube’s SEO and not your own website. Vimeo allows for your website to get credit each time the video is watched. Regardless of where you place your videos, make them short and to the point, with links to your website. Videos only need to be long enough to get your message across and stimulate interest in your practice.

If you can have a blog on your website, it also will help with SEO. What a search engine like Google wants to see is that a patient is on your web page and looking at something for at least 60 seconds. If so, the website is deemed to have information that is relevant, improving your SEO ranking.

Finally, Twitter also can be used for getting messaging out and for branding. The problem with it is that many people go to Twitter to follow a Hollywood celebrity, a sports star, or are looking for mass communication. There is less interest on Twitter for physician outreach.

Continue to: Measuring ROI...

Measuring ROI

Dr. Culligan: What’s the best way to track your return on investment?

Dr. Lotze: First for me was to find out what didn’t work in the office and fix that before really promoting my practice. It’s about the global experience for a patient, as Brad mentioned. As a marketing expert, Heather met with me to understand my goals. She then called my office as a patient to set up an appointment and went through that entire office experience. We identified issues needing improvement.

The next step was to develop a working relationship with my webmaster—someone who can help manage Internet image and SEO. Together, you will develop goals for what the SEO should promote specific to your practice. Once a good SEO program is in place, your website’s ranking will go up—although it can take a minimum of 6 months to see a significant increase. To help understand your website’s performance, your webmaster should provide you with reports on your site’s analytics.

As you go through this process, it is great to have a marketing expert to be the point person. You will work closely together for a while, but eventually you can back off over time. The time and expense you invest on the front end have huge rewards on the back end. Currently, I still spend a reasonable amount of money every month. I have a high self-referral base because of these efforts, however, which results in more patient surgeries and easily covers my expenses. It is money well invested. My website traffic increased by 268% over 2 years (FIGURE). I’ll propose that currently more than half of my patients are self-referrals due to online marketing.

Ms. Schueppert: The only thing I would add is training your front staff. They are checking people in, taking appointments, checking your patients out. Have them be mindful that there are campaigns going on, whether it is a social media push, or a new video that went on the website. They can ask, “How did you hear about us?” when a new patient calls.

Dr. Bowman: Unless you are a large university hospital, where the analytics get significantly more advanced in terms of measuring return on investment (ROI), I think you should just be looking at your schedule and looking at your monthly billings and seeing how they change over time. You can calculate how much a new patient is worth because you can figure out how many patients you have and how much you bill and what your profits are.

Dr. Culligan: For those of us who are hospital employees, you can try to convince the hospital that you can do a detailed ROI analysis, or you can just look at it like (say it’s $3,000 per month), how many surgeries does this project have to generate before the hospital makes that back? The answer is a fraction of 1 case.

Thank you to all of you for your expertise on this roundtable.

To have a thriving business in today’s world, a functioning website is crucial to the overall business health. For a medical practice in general, and for its physicians specifically, it is one of the first steps for maintaining a practice. But to grow that practice, it is crucial to take the steps beyond just having a website. Growth requires website optimization for search engines, an expanding referral base, and the knowledge to use web tools and social media at your disposal to promote the practice and its physicians. In this roundtable, several marketing experts and web-savvy physicians discuss using available tools to best position and grow a practice.

Choosing a web upgrade

Patrick J. Culligan, MD: Peter, can you start us off by describing your relationship with Heather, and how your practice benefitted from her expertise?

Peter M. Lotze, MD: Sure. I am a urogynecologist in the competitive market of pelvic reconstructive surgery in Houston, Texas. Within that market, my main approach was to reach out to other physicians to refer patients to my practice. It generally would work, but took increasingly greater amounts of time to call these physicians up, write them letters, and maintain relationships. I felt that the large, national practice group that I am in did not have a significant web presence optimized to promote my practice, which makes it difficult for patients seeking your services to find you in their search for a doctor. It is helpful for patients to be able to understand from your website who you are, what you do, and what their experience may be like.

Glaring to me was that a web search specific for me or things that I do, would not produce our company’s results until page 2 or more on Google. This can be devastating for a practice because most people don’t go past the first page, and you can end up with fewer self-referrals, which should be a significant portion of new patients to your practice. I knew I needed guidance; I knew of Heather’s expertise given her exceptional past work building marketing strategies.

Digital go-tos for marketing

Heather Schueppert: Yes, I was pleased to work with Dr. Lotze, and at the time was a marketing consultant for practices such as his. But gone are the days of printed material—brochures, pamphlets, or even billboards—to effectively promote a business, or in this case, a practice. What still withstands the test of time, however, as the number 1 marketing referral source is word of mouth—from your trusted friend, family member, or coworker.

It is now proven that the number 2 most trusted form of advertising, the most persuasive and the most motivating, is online marketing.1 It is the “digital word of mouth”—the review. Patients are actively online, and a strong digital presence is critical to provide that direct value to retain and grow your patient base.

Continue to: Foundations of private practice reach out...

Foundations of private practice reach out

There are 3 important areas that I consider the foundation of any private practice marketing strategy (TABLE). First is an updated website that is search engine optimized (SEO). You can’t just set it and forget it, it needs to be an updated website. The algorithms for search engines are changing constantly to try to make it as fair and relevant as possible for patients or consumers to find the businesses they are searching for online.

The second area is review management, and for a physician, or even a care center, to do this on your own is a daunting task. It is a critical component, however, to making sure that your reputation out there, that online word of mouth, is as high a star rating as possible.

The third component is local search, which is basically a form of SEO that helps businesses show up in relevant local searches. We are all familiar with the search, “find a restaurant near me,” anything that pushes those search engines to find something local.

Those are what I call the effective triad: that updated website, the review management, and the local search, and all of these are tied together. I think Dr. Lotze and his practice did these effectively well, and I believe that he achieved his goals for the longer term.

Review/reputation management

Dr. Culligan: Brad, is there something that doctors may not know about Healthgrades, and are there opportunities to take full advantage of this physician-rating site?

Brad Bowman, MD: I agree with everything that Dr. Lotze and Heather have said. Start with yourself—what is it that you want to be, the one thing you want to stand for? Get your own marketing, your website right, then, the point is, once you do all that and you are number 1 in SEO, you are still only going to get about 25% of the people looking for you by name to come to your website. The other 75% are going to look at all the other different sites that are out there to provide information to consumers. So the question becomes what do you do with all these other third-party sites? Healthgrades is the most comprehensive and has the highest traffic of the third-party “find a doctor” sites. In 2020, half of all Americans who go to a doctor will use Healthgrades at some point to help select and connect with that doctor.

Physicians have their focus on the quality of the care they provide. Patients, however, focus on the quality of the entire health care experience. Did I get better? How long did I have to wait? Was the office staff helpful? Scarily enough, we still spend more time shopping for a refrigerator or mattress than we do shopping for a doctor. We still tend to think that all doctors are the same. It is the reality of how we have been trained by our insurance companies and by the health care system. That is why getting your marketing right and getting what is it that you want to be known for out there is important, so that you can get the types of patients you want.

Listings management is very important. Make sure that you are findable everywhere. There are services that will do this: Doctor.com, Reputation.com, and many others. They can help you make sure you get all your basic materials right: addresses, phone numbers, your picture. Because 75% of people are going to end up on third-party websites, if your phone number is wrong there, you could lose that patient.

Then the second piece of working with third-party sites is reputation management. Physician reviews are not a bad thing, they are the new word of mouth, as Heather pointed out. Most (80%) of the reviews are going to be positive. The others will be negative, and that is okay. It is important that you get at least 1 or 2 reviews on all the different sites. We know from Healthgrades.com that going from zero reviews to 1 review will increase your call volume by 60%. If you have the choice between 2 physicians and one practice looks like people have been there before, you will go to that one.

You can learn from reviews as well, consumers provide valid feedback. Best practice is to respond to every positive and negative review. Thank them, indicate that you have listened to them, and address any concerns as necessary.

Continue to: Dr. Lotze...

Dr. Lotze: As an example, one of the paramount things that Heather introduced me to was the third party I use to run my website. That company sends a HIPAA-compliant review out to each patient we have seen that day and gives them the opportunity to rate our services and leave comments. If a patient brings up a concern, we can respond immediately, which is important. Patients appreciate feeling that they have been heard. Typically, communicating with a patient will turn the 3-star review into a 5-star as she follows up with the practice.

Ms. Schueppert: Timeliness is important. And just to mention, there certainly is a time commitment to this (and it is a marathon versus a sprint) and there is some financial investment to get it going, but it could truly be detrimental to a practice if you decide not to do anything at all.

Dr. Bowman: Agencies can really help with the time commitment.

Handling bad reviews

Dr. Culligan: What about that person who seems to have it out for you, perhaps giving you multiple bad reviews?

Dr. Bowman: I have seen this before. At Healthgrades, we recently analyzed 8.4 million patient reviews to see what people wrote about.2 The first thing they will talk about is quality of care as they see it. Did I get better or not? You can’t “fix” every patient; there will be some that you cannot help. The next thing patients comment on is bedside manner. With negative reviews, you will see more comments about the office staff.2

A single negative review actually helps make the positive ones look more credible. But if you do believe someone is trolling you, we can flag it and will investigate to the best of our ability. (Different sites likely have different editorial policies.) For example, we look at the IP addresses of all reviews, and if multiple reviews are coming from the same location, we would only let one through, overwriting the previous review from that address.

Patients just want to be heard. We have seen people change their views, based on how their review is handled and responded to.

Dr. Lotze: Is there a response by the physician that you think tends to work better in terms of resolving the issue that can minimize a perceived caustic reaction to a patient’s criticism?

Dr. Bowman: First, just like with any stressful situation, take a deep breath and respond when you feel like you can be constructive. When you do respond, be gracious. Thank them for their feedback. Make sure you reference something about their concern: “I understand that you had to wait longer than you would have liked.” Acknowledge the problem they reference, and then just apologize: “I’m sorry we didn’t meet your expectations.” Then, if they waited too long for example, “We have a new system where no one should have to wait more than 30 minutes….” You can respond privately or publically. Generally, public responses are better as it shows other consumers that you are willing to listen and consider their point of view.

Continue to: The next phase at Healthgrades...

The next phase at Healthgrades

Dr. Culligan: Do you see changes to the way physician-rating sites are working now? Are we going to stay status quo over the next 10 years, or do you see frontiers in how your site is going to develop?

Dr. Bowman: For Healthgrades, we rely on quantitative and objective measures, not just the qualitative. We are investing heavily right now in trying to help consumers understand what are the relative volumes of different procedures or different patient types that each individual doctor sees. Orthopedics is an easy example—if you have a knee problem, you want to go to someone who specializes in knees. Our job is to help consumers easily identify, “This is a shoulder doctor, this is a knee doctor, and this is why that matters.”

In the meantime, as a physician, you can always go into our site and state your care philosophy, identifying what is the sort of patient that you like to treat. Transparency is good for everyone, and especially physicians. It helps the right patient show up for you, and it helps you do a better job providing referrals.

Social media: Avoid pitfalls, and use it to your benefit

Dr. Lotze: Branding was one of the things that I was confused about, and Heather really helped me out. As physicians, we put ourselves out there on our websites, which we try to make professional sources of information for patients. But patients often want to see what else they can find out about us, including Healthgrades and social media. I think the thing that is important to know with social media is that it is a place where people learn about you as a person. Your social media should be another avenue of promotion. Whether it is your personal or professional Facebook page, people are going to see those sites. You have an opportunity to promote yourself as a good physician and a good person with a wholesome practice that you want people to come to. If a physician is posting questionable things about themselves on any kind of social media, it could be perceived as inappropriate by the patient. That can impact how patients think of you as a person, and how they are going to grade you. If people lose sight of who you are due to a questionable social media posting, everything else (SEO, the website) can be for naught.

Dr. Culligan: What are the most important social media tools to invest your time in?

Ms. Schueppert: Before anybody jumps into social media, I firmly recommend that you make sure your local search and your Google 3-pack is set up—which is basically a method Google uses to display the top 3 results on its listings page. Then make sure you have a review management system in place. Make sure you have that updated website. Those are the foundational elements. Once you have that going, social media is the next added layer to that digital presence.

I usually recommend LinkedIn. It is huge because you are staying in contact with your colleagues, that business-to-business type of connection. It remains a way for physicians to set themselves up as experts in their level of specialty.

From there, it’s either Instagram or Facebook. If you are serving more of the younger generations, the millennials and younger, then Instagram is the way to go. If you are focusing on your 40+, 50+, they are going to be far more on Facebook.

Continue to: Dr. Lotze...

Dr. Lotze: For me, a Facebook page was a great place to start. The cost of those Google ads—the first things we see at the top of a Google search in their own separate box—is significant. If a practice has that kind of money to invest, great; it is an instant way to be first on the page during a search. But there are more cost-effective ways of doing that, especially as you are getting your name out. Facebook provides, at a smaller cost, promotion of whatever it is that you are seeking to promote. You can find people within a certain zip code, for instance, and use a Facebook ad campaign that can drive people to your Facebook page—which should have both routinely updated new posts and a link to your website. The posts should be interesting topics relevant to the patients you wish to treat (avoiding personal stories or controversial discussions). You can put a post together, or you can have a third-party service do this. People who follow your page will get reminders of you and your practice with each new post. As your page followers increase, your Facebook rank will improve, and your page will more likely be discovered by Facebook searches for your services. With an added link to your office practice website, those patients go straight to your site without getting lost in the noise of Google search results.

For Instagram, a short video or an interesting picture, along with a brief statement, are the essentials. You can add a single link. Marketing here is by direct messaging or having patients going to your website through a link. Instagram, like Facebook, offers analytics to help show you what your audience likes to read about, improving the quality of your posts and increasing number of followers.

YouTube is the number 2 search engine behind Google. A Google search for your field of medicine may be filled with pages of competitors. However, YouTube has a much lower volume of competing practices, making it easier for patients to find you. The only downside to YouTube is that it will list your video along with other competing videos, which can draw attention away from your practice.

If you want to promote your website or practice with video, using a company such as Vimeo is a better choice compared with YouTube, as YouTube gets credit for video views—which improves YouTube’s SEO and not your own website. Vimeo allows for your website to get credit each time the video is watched. Regardless of where you place your videos, make them short and to the point, with links to your website. Videos only need to be long enough to get your message across and stimulate interest in your practice.

If you can have a blog on your website, it also will help with SEO. What a search engine like Google wants to see is that a patient is on your web page and looking at something for at least 60 seconds. If so, the website is deemed to have information that is relevant, improving your SEO ranking.

Finally, Twitter also can be used for getting messaging out and for branding. The problem with it is that many people go to Twitter to follow a Hollywood celebrity, a sports star, or are looking for mass communication. There is less interest on Twitter for physician outreach.

Continue to: Measuring ROI...

Measuring ROI

Dr. Culligan: What’s the best way to track your return on investment?

Dr. Lotze: First for me was to find out what didn’t work in the office and fix that before really promoting my practice. It’s about the global experience for a patient, as Brad mentioned. As a marketing expert, Heather met with me to understand my goals. She then called my office as a patient to set up an appointment and went through that entire office experience. We identified issues needing improvement.

The next step was to develop a working relationship with my webmaster—someone who can help manage Internet image and SEO. Together, you will develop goals for what the SEO should promote specific to your practice. Once a good SEO program is in place, your website’s ranking will go up—although it can take a minimum of 6 months to see a significant increase. To help understand your website’s performance, your webmaster should provide you with reports on your site’s analytics.

As you go through this process, it is great to have a marketing expert to be the point person. You will work closely together for a while, but eventually you can back off over time. The time and expense you invest on the front end have huge rewards on the back end. Currently, I still spend a reasonable amount of money every month. I have a high self-referral base because of these efforts, however, which results in more patient surgeries and easily covers my expenses. It is money well invested. My website traffic increased by 268% over 2 years (FIGURE). I’ll propose that currently more than half of my patients are self-referrals due to online marketing.

Ms. Schueppert: The only thing I would add is training your front staff. They are checking people in, taking appointments, checking your patients out. Have them be mindful that there are campaigns going on, whether it is a social media push, or a new video that went on the website. They can ask, “How did you hear about us?” when a new patient calls.

Dr. Bowman: Unless you are a large university hospital, where the analytics get significantly more advanced in terms of measuring return on investment (ROI), I think you should just be looking at your schedule and looking at your monthly billings and seeing how they change over time. You can calculate how much a new patient is worth because you can figure out how many patients you have and how much you bill and what your profits are.

Dr. Culligan: For those of us who are hospital employees, you can try to convince the hospital that you can do a detailed ROI analysis, or you can just look at it like (say it’s $3,000 per month), how many surgeries does this project have to generate before the hospital makes that back? The answer is a fraction of 1 case.

Thank you to all of you for your expertise on this roundtable.

- Anderson A. Online reviews vs. word of mouth: Which one is more important. https://www.revlocal.com/blog/reviewandreputationmanagement/onlinereviewsvswordofmouthwhichoneismoreimportant. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 2020 Patient sentiment report. Healthgrades; Medical Group Management Association. https://www.healthgrades.com/content /patientsentimentreport. Accessed July 17, 2020