User login

Telemedicine: A primer for today’s ObGyn

If telemedicine had not yet begun to play a significant role in your ObGyn practice, it is almost certain to now as the COVID-19 pandemic demands new ways of caring for our patients while keeping others safe from disease. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the term “telemedicine” refers to delivering traditional clinical diagnosis and monitoring via technology (see “ACOG weighs in on telehealth”).1

Whether they realize it or not, most ObGyns have practiced a simple form of telemedicine when they take phone calls from patients who are seeking medication refills. In these cases, physicians either can call the pharmacy to refill the medication or suggest patients make an office appointment to receive a new prescription (much to the chagrin of many patients—especially millennials). Physicians who acquiesce to patients’ phone requests to have prescriptions filled or to others seeking free medical advice are not compensated for these services, yet are legally responsible for their actions and advice—a situation that does not make for good medicine.

This is where telemedicine can be an important addition to an ObGyn practice. Telemedicine saves the patient the time and effort of coming to the office, while providing compensation to the physician for his/her time and advice and providing a record of the interaction, all of which makes for far better medicine. This article—the first of 3 on the subject—discusses the process of integrating telemedicine into a practice with minimal time, energy, and expense.

Telemedicine and the ObGyn practice

Many ObGyn patients do not require an in-person visit in order to receive effective care. There is even the potential to provide prenatal care via telemedicine by replacing some of the many prenatal well-care office visits with at-home care for pregnant women with low-risk pregnancies. A typical virtual visit for a low-risk pregnancy includes utilizing home monitoring equipment to track fetal heart rate, maternal blood pressure, and fundal height.2

Practices typically use telemedicine platforms to manage one or both of the following types of encounters: 1) walk-in visits through the practice’s web site; for most of these, patients tend not to care which physicians they see; their priority is usually the first available provider; and 2) appointment-based consultations, where patients schedule video chats in advance, usually with a specific provider.

Although incorporating telemedicine into a practice may seem overwhelming, it requires minimal additional equipment, interfaces easily with a practice’s web site and electronic medical record (EMR) system, increases productivity, and improves workflow. And patients generally appreciate the option of not having to travel to the office for an appointment.

Most patients and physicians are already comfortable with their mobile phones, tablets, social media, and wearable technology, such as Fitbits. Telemedicine is a logical next step. And given the current situation with COVID-19, it is really not a matter of “if,” but rather “when” to incorporate telemedicine as a communication and practice tool, and the sooner the better.

Continue to: Getting started...

Getting started

Physicians and their colleagues and staff first need to become comfortable with telemedicine technology. Physicians can begin by using video communication for other purposes, such as for conducting staff meetings. They should practice starting and ending calls and adjusting audio volume and video quality to ensure good reception.

Selecting a video platform

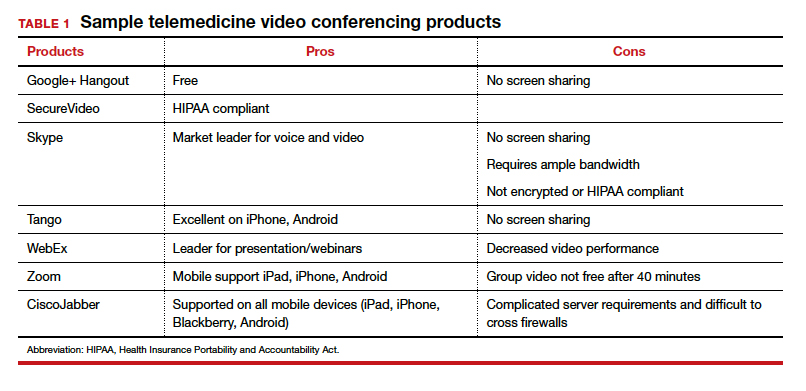

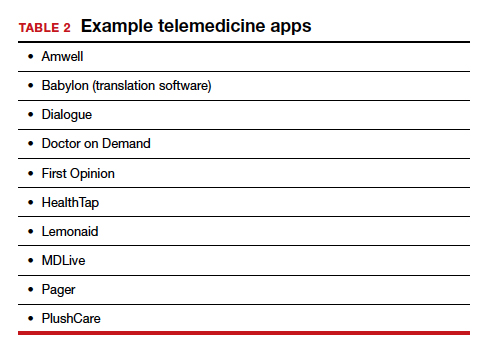

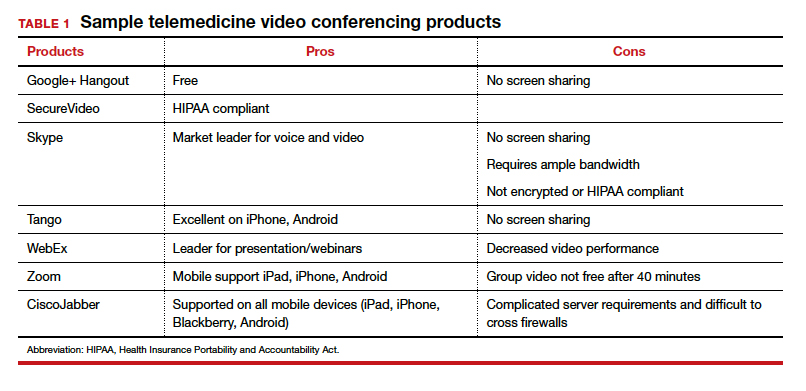

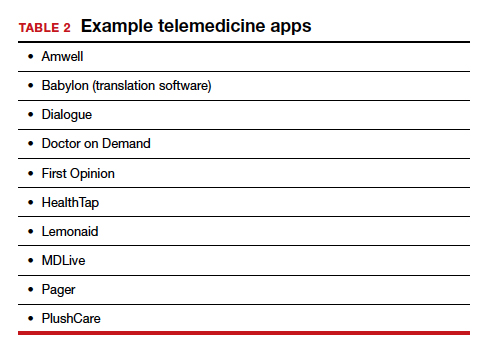

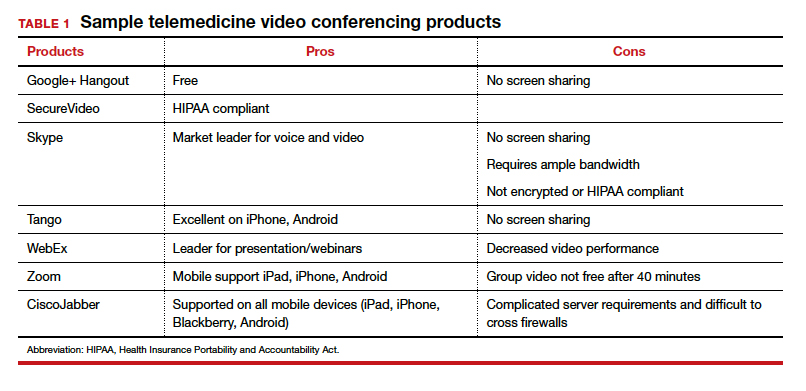

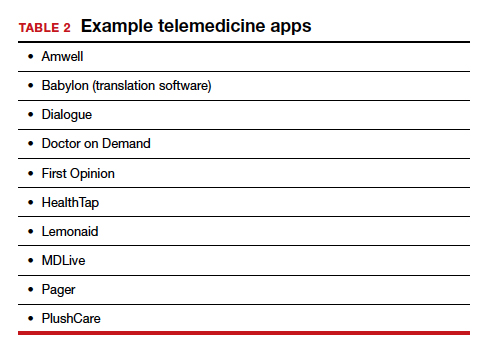

TABLE 1 provides a list of the most popular video providers and the advantages and disadvantages of each, and TABLE 2 shows a list of free video chat apps. Apps are available that can:

- share and mark up lab tests, magnetic resonance images, and other medical documents without exposing the entire desktop

- securely send documents over a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant video

- stream digital device images live while still seeing patients’ faces.

Physicians should make sure their implementation team has the necessary equipment, including webcams, microphones, and speakers, and they should take the time to do research and test out a few programs before selecting one for their practice. Consider appointing a telemedicine point person who is knowledgeable about the technology and can patiently explain it to others. And keep in mind that video chatting is dependent upon a fast, strong Internet connection that has sufficient bandwidth to transport a large amount of data. If your practice has connectivity problems, consider consulting with an information technology (IT) expert.

Testing it out and obtaining feedback

Once a team is comfortable using video within the practice, it is time to test it out with a few patients and perhaps a few payers. Most patients are eager to start using video for their medical encounters. Even senior patients are often willing to try consults via video. According to a recent survey, 64% of patients are willing to see a physician over video.3 And among those who were comfortable accepting an invitation to participate in a video encounter, increasing age was actually associated with a higher likelihood to accept an invite.

Physician colleagues, medical assistants, and nurse practitioners will need some basic telemedicine skills, and physicians and staff should be prepared to make video connections seamless for patients. Usually, patients need some guidance and encouragement, such as telling them to check their spam folder for their invites if the invites fail to arrive in their email inbox, adjusting audio settings, or setting up a webcam. In the beginning, ObGyns should make sure they build in plenty of buffer time for the unexpected, as there will certainly be some “bugs” that need to be worked out.

ObGyns should encourage and collect patient feedback to such questions as:

- What kinds of devices (laptop, mobile) do they prefer using?

- What kind of networks are they using (3G, corporate, home)?

- What features do they like? What features do they have a hard time finding?

- What do they like or not like about the video experience?

- Keep track of the types of questions patients ask, and be patient as patients become acclimated to the video consultation experience.

Continue to: Streamlining online workflow...

Streamlining online workflow

Armed with feedback from patients, it is time to start streamlining online workflow. Most ObGyns want to be able to manage video visits in a way that is similar to the way they manage face-to-face visits with patients. This may mean experimenting with a virtual waiting room. A virtual waiting room is a simple web page or link that can be sent to patients. On that page, patients sign in with minimal demographic information and select one of the time slots when the physician is available. Typically, these programs are designed to alert the physicians and/or staff when a patient enters the virtual waiting room. Patients have access to the online patient queue and can start a chat or video call when both parties are ready. Such a waiting room model serves as a stepping stone for new practices to familiarize themselves with video conferencing. This approach is also perfect for practices that already have a practice management system and just want to add a video component.

Influences on practice workflow

With good time management, telemedicine can improve the efficiency and productivity of your practice. Your daily schedule and management of patients will need some minor changes, but significant alterations to your existing schedule and workflow are generally unnecessary. One of the advantages of telemedicine is the convenience of prompt care and the easy access patients have to your practice. This decreases visits to the emergency department and to urgent care centers.

Consider scheduling telemedicine appointments at the end of the day when your staff has left the office, as no staff members are required for a telemedicine visit. Ideally, you should offer a set time to communicate with patients, as this avoids having to make multiple calls to reach a patient. Another advantage of telemedicine is that you can provide care in the evenings and on weekends if you want. Whereas before you might have been fielding calls from patients during these times and not being compensated, with telemedicine you can conduct a virtual visit from any location and any computer or mobile phone and receive remuneration for your care.

And while access to care has been a problem in many ObGyn practices, many additional patients can be accommodated into a busy ObGyn practice by using telemedicine.

Telemedicine and the coronavirus

The current health care crisis makes implementing telemedicine essential. Patients who think they may have COVID-19 or who have been diagnosed need to be quarantined. Such patients can be helped safely in the comfort of their own homes without endangering others. Patients can be triaged virtually. All those who are febrile or have respiratory symptoms can continue to avail themselves of virtual visits.

According to reports in the media, COVID-19 is stretching the health care workforce to its limits and creating a shortage, both because of the sheer number of cases and because health care workers are getting sick themselves. Physicians who test positive do not have to be completely removed from the workforce if they have the ability to care for patients remotely from their homes. And not incidentally the new environment has prompted the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) and private payers to initiate national payment policies that create parity between office and telemedicine visits.4

Continue to: Bottom line...

Bottom line

Patient-driven care is the future, and telemedicine is part of that. Patients want to have ready access to their health care providers without having to devote hours to a medical encounter that could be completed in a matter of minutes via telemedicine.

In the next article in this series, we will review the proper coding for a telemedicine visit so that appropriate compensation is gleaned. We will also review the barriers to implementing telemedicine visits. The third article is written with the assistance of 2 health care attorneys, Anjali Dooley and Nadia de la Houssaye, who are experts in telemedicine and who have helped dozens of practices and hospitals implement the technology. They provide legal guidelines for ObGyns who are considering adding telemedicine to their practice. ●

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) encourages all practices and facilities without telemedicine capabilities “to strategize about how telehealth could be integrated into their services as appropriate.”1 In doing so, they also encourage consideration of ways to care for those who may not have access to such technology or who do not know how to use it. They also explain that a number of federal telehealth policy changes have been made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and that most private health insurers are following suit.2 Such changes include:

- covering all telehealth visits for all traditional Medicare beneficiaries regardless of geographic location or originating site

- not requiring physicians to have a pre-existing relationship with a patient to provide a telehealth visit

- permitting the use of FaceTime, Skype, and other everyday communication technologies to provide telehealth visits.

A summary of the major telehealth policy changes, as well as information on how to code and bill for telehealth visits can be found at https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/~/link .aspx?_id=3803296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 FAQs for obstetriciangynecologists, gynecology. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid19faqs-for-ob-gyns-gynecology. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. Updated April 2, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinicalinformation/physician-faqs/~/link.aspx?_id=3803296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Implementing telehealth in practice. ACOG Committee Opinion. February 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/02 /implementing-telehealth-in-practice. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- de Mooij MJM, Hodny RL, O’Neil DA, et al. OB nest: reimagining low-risk prenatal care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:458-466.

- Gardner MR, Jenkins SM, O’Neil DA, et al. Perceptions of video-based appointments from the patient’s home: a patient survey. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:281-285.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. Updated April 2, 2020. https://www.acog.org /clinical-information/physician-faqs/~/link.aspx?_id=380 3296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z. Accessed April 8, 2020.

If telemedicine had not yet begun to play a significant role in your ObGyn practice, it is almost certain to now as the COVID-19 pandemic demands new ways of caring for our patients while keeping others safe from disease. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the term “telemedicine” refers to delivering traditional clinical diagnosis and monitoring via technology (see “ACOG weighs in on telehealth”).1

Whether they realize it or not, most ObGyns have practiced a simple form of telemedicine when they take phone calls from patients who are seeking medication refills. In these cases, physicians either can call the pharmacy to refill the medication or suggest patients make an office appointment to receive a new prescription (much to the chagrin of many patients—especially millennials). Physicians who acquiesce to patients’ phone requests to have prescriptions filled or to others seeking free medical advice are not compensated for these services, yet are legally responsible for their actions and advice—a situation that does not make for good medicine.

This is where telemedicine can be an important addition to an ObGyn practice. Telemedicine saves the patient the time and effort of coming to the office, while providing compensation to the physician for his/her time and advice and providing a record of the interaction, all of which makes for far better medicine. This article—the first of 3 on the subject—discusses the process of integrating telemedicine into a practice with minimal time, energy, and expense.

Telemedicine and the ObGyn practice

Many ObGyn patients do not require an in-person visit in order to receive effective care. There is even the potential to provide prenatal care via telemedicine by replacing some of the many prenatal well-care office visits with at-home care for pregnant women with low-risk pregnancies. A typical virtual visit for a low-risk pregnancy includes utilizing home monitoring equipment to track fetal heart rate, maternal blood pressure, and fundal height.2

Practices typically use telemedicine platforms to manage one or both of the following types of encounters: 1) walk-in visits through the practice’s web site; for most of these, patients tend not to care which physicians they see; their priority is usually the first available provider; and 2) appointment-based consultations, where patients schedule video chats in advance, usually with a specific provider.

Although incorporating telemedicine into a practice may seem overwhelming, it requires minimal additional equipment, interfaces easily with a practice’s web site and electronic medical record (EMR) system, increases productivity, and improves workflow. And patients generally appreciate the option of not having to travel to the office for an appointment.

Most patients and physicians are already comfortable with their mobile phones, tablets, social media, and wearable technology, such as Fitbits. Telemedicine is a logical next step. And given the current situation with COVID-19, it is really not a matter of “if,” but rather “when” to incorporate telemedicine as a communication and practice tool, and the sooner the better.

Continue to: Getting started...

Getting started

Physicians and their colleagues and staff first need to become comfortable with telemedicine technology. Physicians can begin by using video communication for other purposes, such as for conducting staff meetings. They should practice starting and ending calls and adjusting audio volume and video quality to ensure good reception.

Selecting a video platform

TABLE 1 provides a list of the most popular video providers and the advantages and disadvantages of each, and TABLE 2 shows a list of free video chat apps. Apps are available that can:

- share and mark up lab tests, magnetic resonance images, and other medical documents without exposing the entire desktop

- securely send documents over a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant video

- stream digital device images live while still seeing patients’ faces.

Physicians should make sure their implementation team has the necessary equipment, including webcams, microphones, and speakers, and they should take the time to do research and test out a few programs before selecting one for their practice. Consider appointing a telemedicine point person who is knowledgeable about the technology and can patiently explain it to others. And keep in mind that video chatting is dependent upon a fast, strong Internet connection that has sufficient bandwidth to transport a large amount of data. If your practice has connectivity problems, consider consulting with an information technology (IT) expert.

Testing it out and obtaining feedback

Once a team is comfortable using video within the practice, it is time to test it out with a few patients and perhaps a few payers. Most patients are eager to start using video for their medical encounters. Even senior patients are often willing to try consults via video. According to a recent survey, 64% of patients are willing to see a physician over video.3 And among those who were comfortable accepting an invitation to participate in a video encounter, increasing age was actually associated with a higher likelihood to accept an invite.

Physician colleagues, medical assistants, and nurse practitioners will need some basic telemedicine skills, and physicians and staff should be prepared to make video connections seamless for patients. Usually, patients need some guidance and encouragement, such as telling them to check their spam folder for their invites if the invites fail to arrive in their email inbox, adjusting audio settings, or setting up a webcam. In the beginning, ObGyns should make sure they build in plenty of buffer time for the unexpected, as there will certainly be some “bugs” that need to be worked out.

ObGyns should encourage and collect patient feedback to such questions as:

- What kinds of devices (laptop, mobile) do they prefer using?

- What kind of networks are they using (3G, corporate, home)?

- What features do they like? What features do they have a hard time finding?

- What do they like or not like about the video experience?

- Keep track of the types of questions patients ask, and be patient as patients become acclimated to the video consultation experience.

Continue to: Streamlining online workflow...

Streamlining online workflow

Armed with feedback from patients, it is time to start streamlining online workflow. Most ObGyns want to be able to manage video visits in a way that is similar to the way they manage face-to-face visits with patients. This may mean experimenting with a virtual waiting room. A virtual waiting room is a simple web page or link that can be sent to patients. On that page, patients sign in with minimal demographic information and select one of the time slots when the physician is available. Typically, these programs are designed to alert the physicians and/or staff when a patient enters the virtual waiting room. Patients have access to the online patient queue and can start a chat or video call when both parties are ready. Such a waiting room model serves as a stepping stone for new practices to familiarize themselves with video conferencing. This approach is also perfect for practices that already have a practice management system and just want to add a video component.

Influences on practice workflow

With good time management, telemedicine can improve the efficiency and productivity of your practice. Your daily schedule and management of patients will need some minor changes, but significant alterations to your existing schedule and workflow are generally unnecessary. One of the advantages of telemedicine is the convenience of prompt care and the easy access patients have to your practice. This decreases visits to the emergency department and to urgent care centers.

Consider scheduling telemedicine appointments at the end of the day when your staff has left the office, as no staff members are required for a telemedicine visit. Ideally, you should offer a set time to communicate with patients, as this avoids having to make multiple calls to reach a patient. Another advantage of telemedicine is that you can provide care in the evenings and on weekends if you want. Whereas before you might have been fielding calls from patients during these times and not being compensated, with telemedicine you can conduct a virtual visit from any location and any computer or mobile phone and receive remuneration for your care.

And while access to care has been a problem in many ObGyn practices, many additional patients can be accommodated into a busy ObGyn practice by using telemedicine.

Telemedicine and the coronavirus

The current health care crisis makes implementing telemedicine essential. Patients who think they may have COVID-19 or who have been diagnosed need to be quarantined. Such patients can be helped safely in the comfort of their own homes without endangering others. Patients can be triaged virtually. All those who are febrile or have respiratory symptoms can continue to avail themselves of virtual visits.

According to reports in the media, COVID-19 is stretching the health care workforce to its limits and creating a shortage, both because of the sheer number of cases and because health care workers are getting sick themselves. Physicians who test positive do not have to be completely removed from the workforce if they have the ability to care for patients remotely from their homes. And not incidentally the new environment has prompted the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) and private payers to initiate national payment policies that create parity between office and telemedicine visits.4

Continue to: Bottom line...

Bottom line

Patient-driven care is the future, and telemedicine is part of that. Patients want to have ready access to their health care providers without having to devote hours to a medical encounter that could be completed in a matter of minutes via telemedicine.

In the next article in this series, we will review the proper coding for a telemedicine visit so that appropriate compensation is gleaned. We will also review the barriers to implementing telemedicine visits. The third article is written with the assistance of 2 health care attorneys, Anjali Dooley and Nadia de la Houssaye, who are experts in telemedicine and who have helped dozens of practices and hospitals implement the technology. They provide legal guidelines for ObGyns who are considering adding telemedicine to their practice. ●

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) encourages all practices and facilities without telemedicine capabilities “to strategize about how telehealth could be integrated into their services as appropriate.”1 In doing so, they also encourage consideration of ways to care for those who may not have access to such technology or who do not know how to use it. They also explain that a number of federal telehealth policy changes have been made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and that most private health insurers are following suit.2 Such changes include:

- covering all telehealth visits for all traditional Medicare beneficiaries regardless of geographic location or originating site

- not requiring physicians to have a pre-existing relationship with a patient to provide a telehealth visit

- permitting the use of FaceTime, Skype, and other everyday communication technologies to provide telehealth visits.

A summary of the major telehealth policy changes, as well as information on how to code and bill for telehealth visits can be found at https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/~/link .aspx?_id=3803296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 FAQs for obstetriciangynecologists, gynecology. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid19faqs-for-ob-gyns-gynecology. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. Updated April 2, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinicalinformation/physician-faqs/~/link.aspx?_id=3803296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z. Accessed April 8, 2020.

If telemedicine had not yet begun to play a significant role in your ObGyn practice, it is almost certain to now as the COVID-19 pandemic demands new ways of caring for our patients while keeping others safe from disease. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the term “telemedicine” refers to delivering traditional clinical diagnosis and monitoring via technology (see “ACOG weighs in on telehealth”).1

Whether they realize it or not, most ObGyns have practiced a simple form of telemedicine when they take phone calls from patients who are seeking medication refills. In these cases, physicians either can call the pharmacy to refill the medication or suggest patients make an office appointment to receive a new prescription (much to the chagrin of many patients—especially millennials). Physicians who acquiesce to patients’ phone requests to have prescriptions filled or to others seeking free medical advice are not compensated for these services, yet are legally responsible for their actions and advice—a situation that does not make for good medicine.

This is where telemedicine can be an important addition to an ObGyn practice. Telemedicine saves the patient the time and effort of coming to the office, while providing compensation to the physician for his/her time and advice and providing a record of the interaction, all of which makes for far better medicine. This article—the first of 3 on the subject—discusses the process of integrating telemedicine into a practice with minimal time, energy, and expense.

Telemedicine and the ObGyn practice

Many ObGyn patients do not require an in-person visit in order to receive effective care. There is even the potential to provide prenatal care via telemedicine by replacing some of the many prenatal well-care office visits with at-home care for pregnant women with low-risk pregnancies. A typical virtual visit for a low-risk pregnancy includes utilizing home monitoring equipment to track fetal heart rate, maternal blood pressure, and fundal height.2

Practices typically use telemedicine platforms to manage one or both of the following types of encounters: 1) walk-in visits through the practice’s web site; for most of these, patients tend not to care which physicians they see; their priority is usually the first available provider; and 2) appointment-based consultations, where patients schedule video chats in advance, usually with a specific provider.

Although incorporating telemedicine into a practice may seem overwhelming, it requires minimal additional equipment, interfaces easily with a practice’s web site and electronic medical record (EMR) system, increases productivity, and improves workflow. And patients generally appreciate the option of not having to travel to the office for an appointment.

Most patients and physicians are already comfortable with their mobile phones, tablets, social media, and wearable technology, such as Fitbits. Telemedicine is a logical next step. And given the current situation with COVID-19, it is really not a matter of “if,” but rather “when” to incorporate telemedicine as a communication and practice tool, and the sooner the better.

Continue to: Getting started...

Getting started

Physicians and their colleagues and staff first need to become comfortable with telemedicine technology. Physicians can begin by using video communication for other purposes, such as for conducting staff meetings. They should practice starting and ending calls and adjusting audio volume and video quality to ensure good reception.

Selecting a video platform

TABLE 1 provides a list of the most popular video providers and the advantages and disadvantages of each, and TABLE 2 shows a list of free video chat apps. Apps are available that can:

- share and mark up lab tests, magnetic resonance images, and other medical documents without exposing the entire desktop

- securely send documents over a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant video

- stream digital device images live while still seeing patients’ faces.

Physicians should make sure their implementation team has the necessary equipment, including webcams, microphones, and speakers, and they should take the time to do research and test out a few programs before selecting one for their practice. Consider appointing a telemedicine point person who is knowledgeable about the technology and can patiently explain it to others. And keep in mind that video chatting is dependent upon a fast, strong Internet connection that has sufficient bandwidth to transport a large amount of data. If your practice has connectivity problems, consider consulting with an information technology (IT) expert.

Testing it out and obtaining feedback

Once a team is comfortable using video within the practice, it is time to test it out with a few patients and perhaps a few payers. Most patients are eager to start using video for their medical encounters. Even senior patients are often willing to try consults via video. According to a recent survey, 64% of patients are willing to see a physician over video.3 And among those who were comfortable accepting an invitation to participate in a video encounter, increasing age was actually associated with a higher likelihood to accept an invite.

Physician colleagues, medical assistants, and nurse practitioners will need some basic telemedicine skills, and physicians and staff should be prepared to make video connections seamless for patients. Usually, patients need some guidance and encouragement, such as telling them to check their spam folder for their invites if the invites fail to arrive in their email inbox, adjusting audio settings, or setting up a webcam. In the beginning, ObGyns should make sure they build in plenty of buffer time for the unexpected, as there will certainly be some “bugs” that need to be worked out.

ObGyns should encourage and collect patient feedback to such questions as:

- What kinds of devices (laptop, mobile) do they prefer using?

- What kind of networks are they using (3G, corporate, home)?

- What features do they like? What features do they have a hard time finding?

- What do they like or not like about the video experience?

- Keep track of the types of questions patients ask, and be patient as patients become acclimated to the video consultation experience.

Continue to: Streamlining online workflow...

Streamlining online workflow

Armed with feedback from patients, it is time to start streamlining online workflow. Most ObGyns want to be able to manage video visits in a way that is similar to the way they manage face-to-face visits with patients. This may mean experimenting with a virtual waiting room. A virtual waiting room is a simple web page or link that can be sent to patients. On that page, patients sign in with minimal demographic information and select one of the time slots when the physician is available. Typically, these programs are designed to alert the physicians and/or staff when a patient enters the virtual waiting room. Patients have access to the online patient queue and can start a chat or video call when both parties are ready. Such a waiting room model serves as a stepping stone for new practices to familiarize themselves with video conferencing. This approach is also perfect for practices that already have a practice management system and just want to add a video component.

Influences on practice workflow

With good time management, telemedicine can improve the efficiency and productivity of your practice. Your daily schedule and management of patients will need some minor changes, but significant alterations to your existing schedule and workflow are generally unnecessary. One of the advantages of telemedicine is the convenience of prompt care and the easy access patients have to your practice. This decreases visits to the emergency department and to urgent care centers.

Consider scheduling telemedicine appointments at the end of the day when your staff has left the office, as no staff members are required for a telemedicine visit. Ideally, you should offer a set time to communicate with patients, as this avoids having to make multiple calls to reach a patient. Another advantage of telemedicine is that you can provide care in the evenings and on weekends if you want. Whereas before you might have been fielding calls from patients during these times and not being compensated, with telemedicine you can conduct a virtual visit from any location and any computer or mobile phone and receive remuneration for your care.

And while access to care has been a problem in many ObGyn practices, many additional patients can be accommodated into a busy ObGyn practice by using telemedicine.

Telemedicine and the coronavirus

The current health care crisis makes implementing telemedicine essential. Patients who think they may have COVID-19 or who have been diagnosed need to be quarantined. Such patients can be helped safely in the comfort of their own homes without endangering others. Patients can be triaged virtually. All those who are febrile or have respiratory symptoms can continue to avail themselves of virtual visits.

According to reports in the media, COVID-19 is stretching the health care workforce to its limits and creating a shortage, both because of the sheer number of cases and because health care workers are getting sick themselves. Physicians who test positive do not have to be completely removed from the workforce if they have the ability to care for patients remotely from their homes. And not incidentally the new environment has prompted the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) and private payers to initiate national payment policies that create parity between office and telemedicine visits.4

Continue to: Bottom line...

Bottom line

Patient-driven care is the future, and telemedicine is part of that. Patients want to have ready access to their health care providers without having to devote hours to a medical encounter that could be completed in a matter of minutes via telemedicine.

In the next article in this series, we will review the proper coding for a telemedicine visit so that appropriate compensation is gleaned. We will also review the barriers to implementing telemedicine visits. The third article is written with the assistance of 2 health care attorneys, Anjali Dooley and Nadia de la Houssaye, who are experts in telemedicine and who have helped dozens of practices and hospitals implement the technology. They provide legal guidelines for ObGyns who are considering adding telemedicine to their practice. ●

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) encourages all practices and facilities without telemedicine capabilities “to strategize about how telehealth could be integrated into their services as appropriate.”1 In doing so, they also encourage consideration of ways to care for those who may not have access to such technology or who do not know how to use it. They also explain that a number of federal telehealth policy changes have been made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and that most private health insurers are following suit.2 Such changes include:

- covering all telehealth visits for all traditional Medicare beneficiaries regardless of geographic location or originating site

- not requiring physicians to have a pre-existing relationship with a patient to provide a telehealth visit

- permitting the use of FaceTime, Skype, and other everyday communication technologies to provide telehealth visits.

A summary of the major telehealth policy changes, as well as information on how to code and bill for telehealth visits can be found at https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/~/link .aspx?_id=3803296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 FAQs for obstetriciangynecologists, gynecology. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid19faqs-for-ob-gyns-gynecology. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. Updated April 2, 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinicalinformation/physician-faqs/~/link.aspx?_id=3803296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Implementing telehealth in practice. ACOG Committee Opinion. February 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/02 /implementing-telehealth-in-practice. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- de Mooij MJM, Hodny RL, O’Neil DA, et al. OB nest: reimagining low-risk prenatal care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:458-466.

- Gardner MR, Jenkins SM, O’Neil DA, et al. Perceptions of video-based appointments from the patient’s home: a patient survey. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:281-285.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. Updated April 2, 2020. https://www.acog.org /clinical-information/physician-faqs/~/link.aspx?_id=380 3296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Implementing telehealth in practice. ACOG Committee Opinion. February 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/02 /implementing-telehealth-in-practice. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- de Mooij MJM, Hodny RL, O’Neil DA, et al. OB nest: reimagining low-risk prenatal care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:458-466.

- Gardner MR, Jenkins SM, O’Neil DA, et al. Perceptions of video-based appointments from the patient’s home: a patient survey. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:281-285.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Managing patients remotely: billing for digital and telehealth services. Updated April 2, 2020. https://www.acog.org /clinical-information/physician-faqs/~/link.aspx?_id=380 3296EAAD940C69525D4DD2679A00E&_z=z. Accessed April 8, 2020.

COVID-19: We are in a war, without the most effective weapons to fight a novel viral pathogen

On June 17, 1775, American colonists, defending a forward redoubt on Breed’s Hill, ran out of gunpowder, and their position was overrun by British troops. The Battle of Bunker Hill resulted in the death of 140 colonists and 226 British soldiers, setting the stage for major combat throughout the colonies. American colonists lacked many necessary weapons. They had almost no gunpowder, few field cannons, and no warships. Yet, they fought on with the weapons at hand for 6 long years.

In the spring of 2020, American society has been shaken by the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals have been overrun with thousands of people infected with the disease. Some hospitals are breaking under the crush of intensely ill people filling up and spilling out of intensive care units. We are in a war, fighting a viral disease with a limited supply of weapons. We do not have access to the most powerful medical munitions: easily available rapid testing, proven antiviral medications, and an effective vaccine. Nevertheless, clinicians and patients are courageous, and we will continue the fight with the limited weapons we have until the pandemic is brought to an end.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus is aptly named because it is usually transmitted through close contact with respiratory droplets. The disease can progress acutely, and some people experience a remarkably severe respiratory syndrome, including tachypnea, hypoxia, and interstitial and alveolar opacities on chest x-ray, necessitating ventilatory support. The virus is an encapsulated single-stranded RNA virus. When viewed by electron microscopy, the virus appears to have a halo or crown, hence it is named “coronavirus.” Among infected individuals, the virus is present in the upper respiratory system and in feces but not in urine.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) believes that respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces are the major routes of transmission.2 The highest risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease occurs in people with one or more of the following characteristics: age greater than 70 years, hypertension, diabetes, respiratory disease, heart disease, and immunosuppression.3,4 Pregnant women do not appear to be at increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease.4 The case fatality rate is highest in people 80 years of age or older.5

Who is infected with SARS-CoV-2?

Rapid high-fidelity testing for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid sequences would be the best approach to identifying people with COVID-19 disease. At the beginning of the pandemic, testing was strictly rationed because of lack of reagents and test swabs. Clinicians were permitted to test only a minority of people who had symptoms. Asymptomatic individuals were not eligible to be tested. This terribly flawed approach to screening permitted a vast army of SARS-CoV-2–positive asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic people to circulate unchecked in the general population, infecting dozens of other people, some of whom developed moderate or severe disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported on 7 independent clusters of COVID-19 disease, each of which appear to have been caused by one asymptomatic infected individual.6 Another cluster of COVID-19 disease from China appears to have been caused by one asymptomatic infected individual.7 Based on limited data, it appears that there may be a 1- to 3-day window where an individual with COVID-19 may be asymptomatic and able to infect others. I suspect that we will soon discover, based on testing for the presence of high-titre anti SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, that many people with no history of illness and people with mild respiratory symptoms had an undiagnosed COVID-19 infection.

As testing capacity expands we likely will be testing all women, including asymptomatic women, before they arrive at the hospital for childbirth or gynecologic surgery, as well as all inpatients and women with respiratory symptoms having an ambulatory encounter.

With expanded testing capability, some pregnant women who were symptomatic and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 have had sequential long-term follow-up testing. A frequent observation is that over one to two weeks the viral symptoms resolve and the nasopharyngeal test becomes negative for SARS-CoV-2 on multiple sequential tests, only to become positive at a later date. The cause of the positive-negative-negative-positive test results is unknown, but it raises the possibility that once a person tests positive for SARS-CoV-2, they may be able to transmit the infection over many weeks, even after viral symptoms resolve.

Continue to: COVID-19: Respiratory droplet or aerosol transmission?

COVID-19: Respiratory droplet or aerosol transmission?

Respiratory droplets are large particles (> 5 µm in diameter) that tend to be pulled to the ground or furniture surfaces by gravity. Respiratory droplets do not circulate in the air for an extended period of time. Droplet nuclei are small particles less than 5 µm in diameter. These small particles may become aerosolized and float through the air for an extended period of time. The CDC and WHO believe that under ordinary conditions, SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted through respiratory droplets and contact routes.2 In an analysis of more than 75,000 COVID-19 cases in China there were no reports of transmission by aerosolized airborne virus. Therefore, under ordinary conditions, surgical masks, face shields, gowns, and gloves provide a high level of protection from infection.8

In contrast to the WHO’s perspective, Dr. Harvey Fineberg, Chair of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats, wrote a letter to the federal Office of Science and Technology Policy warning that normal breathing might generate aerosolization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and result in airborne transmission.9 A report from the University of Nebraska Medical Center supports the concept of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. In a study of 13 patients with COVID-19, room surfaces, toilet facilities, and air had evidence of viral contamination.10 The investigators concluded that disease spreads through respiratory droplets, person-to-person touch, contaminated surfaces, and airborne routes. Other investigators also have reported that aersolization of SARS-CoV-2 may occur.11 Professional societies recommend that all medical staff caring for potential or confirmed COVID-19 patients should use personal protective equipment (PPE), including respirators (N95 respirators) when available. Importantly, all medical staff should be trained in and adhere to proper donning and doffing of PPE. The controversy about the modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 will continue, but as clinicians we need to work within the constraints of the equipment we have.

Certain medical procedures and devices are known to generate aerosolization of respiratory secretions. These procedures and devices include: bronchoscopy, intubation, extubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, nebulization, high-flow oxygen masks, and continuous- and bilevel-positive airway pressure devices. When aerosols are generated during the care of a patient with COVID-19, surgical masks are not sufficient protection against infection. When an aerosol is generated maximal protection of health care workers from viral transmission requires use of a negative-pressure room and an N95 respirator or powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) device. However, negative-pressure rooms, N95 masks, and PAPRs are in very short supply or are unavailable in some health systems. We are lucky at our hospital that all of the labor rooms can be configured to operate in a negative-pressure mode, limiting potential airborne spread of the virus on the unit. Many hospitals restrict the use of N95 masks to anesthesiologists, leaving nurses, ObGyns, and surgical technicians without the best protective equipment, risking their health. As one action to reduce aerosolization of virus, obstetricians can markedly reduce the use of oxygen masks and nasal cannulas by laboring women.

Universal use of surgical masks and mouth-nose coverings

During the entire COVID-19 pandemic, PPE has been in short supply, including severe shortages of N95 masks, PAPRs, and in some health systems, surgical masks, gowns, eye protection, and face shields. Given the severe shortages, some clinicians have needed to conserve PPE, using the same PPE across multiple patient encounters and across multiple work shifts.

Given that the virus is transmitted by respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces, use of face coverings, including surgical masks, face shields, and gloves is critically important. Scrupulous hand hygiene is a simple approach to reducing infection risk. In my health system, all employees are required to wear a surgical mask, all day every day, requiring distribution of 35,000 masks daily.12 We also require every patient and visitor to our health care facilities to use a face mask. The purpose of the procedure or surgical mask is to prevent presymptomatic spread of COVID-19 from an asymptomatic health care worker to an uninfected patient or a colleague by reducing the transmission of respiratory droplets. Another benefit is to protect the uninfected health care worker from patients and colleagues who are infected and not yet diagnosed with COVID-19. The CDC now recommends that all people wear a mouth and nose covering when they are outside of their residence. America may become a nation where wearing masks in public becomes a routine practice. Since SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted by respiratory droplets, social distancing is an important preventive measure.

Continue to: Obstetric care...

Obstetric care

Can it be repeated too often? No. Containing COVID-19 disease requires social distancing, fastidious hand hygiene, and using a mask that covers the mouth and nose.

Pregnant women should be advised to assiduously practice social distancing and to wear a face covering or mask in public. Hand hygiene should be emphasized. Pregnant women with children should be advised to not allow their children to play with non‒cohabiting children because children may be asymptomatic vectors for COVID-19.

Pregnant health care workers should stop face-to-face contact with patients after 36 weeks’ gestation to avoid a late pregnancy infection that might cause the mother to be separated from her newborn. Based on data currently available, pregnancy in the absence of another risk factor is not a major risk factor for developing severe COVID-19 disease.13

Hyperthermia is a common feature of COVID-19. Acetaminophen is recommended treatment to suppress pyrexia during pregnancy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has transformed prenatal care from a series of face-to-face encounters at a health care facility to telemedicine either by telephone or a videoconferencing portal. Many factors contributed to the rapid switch to telemedicine, including orders by governors to restrict unnecessary travel, patients’ fear of contracting COVID-19 at their clinicians’ offices, clinicians’ fear of contracting COVID-19 from patients, and insurers’ rapid implementation of policies to pay for telemedicine visits. Most prenatal visits can be provided through telemedicine as long as the patient has a home blood pressure cuff and can reliably use the instrument. In-person visits may be required for blood testing, ultrasound assessment, anti-Rh immunoglobulin administration, and group B streptococcal infection screening. One regimen is to limit in-person prenatal visits to encounters at 12, 20, 28, and 36 weeks’ gestation when blood testing and ultrasound examinations are needed. The postpartum visit also may be conducted using telemedicine.

Pregnant women with COVID-19 and pneumonia are reported to have high rates of preterm birth less than 37 weeks (41%) and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (19%).14

The rate of vertical transmission from mother to fetus is probably very low (<1%).15 However, based on serological studies, an occasional newborn has been reported to have IgM and IgG antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein at birth.16,17

Pregnant women should be consistently and regularly screened for symptoms of an upper respiratory infection, including: fever, new cough, new runny nose or nasal congestion, new sore throat, shortness of breath, muscle aches, and anosmia. A report of any of these symptoms should result in nucleic acid testing of a nasal swab for SARS-CoV-2 of all pregnant women. Given limited testing resources, however, symptomatic pregnant women with the following characteristics should be prioritized for testing: if the woman is more than 36 weeks pregnant, intrapartum, or in the hospital after delivery. Ambulatory pregnant women with symptoms who do not need medical care should quarantine themselves at home, if possible, or at another secure location away from their families. In some regions, testing of ambulatory patients with upper respiratory symptoms is limited.

All women scheduled for induction or cesarean delivery (CD) and their support person should have a symptom screen 24 to 48 hours before arrival to the hospital and should be rescreened prior to entry to labor and delivery. In this situation if the pregnant woman screens positive, she should be tested for SARS-CoV-2, and if the test result is positive, the scheduled induction and CD should be rescheduled, if possible. All hospitalized women and their support persons should be screened for symptoms daily. If the pregnant woman screens positive she should have a nucleic acid test for SARS-CoV-2. If the support person screens positive, he or she should be sent home.

Systemic glucocorticoids may worsen the course of COVID-19. For pregnant women with COVID-19 disease, betamethasone administration should be limited to women at high risk for preterm delivery within 7 days and only given to women between 23 weeks to 33 weeks 6 days of gestation. Women at risk for preterm delivery at 34 weeks to 36 weeks and 6 days of gestation should not be given betamethasone.

If cervical ripening is required, outpatient regimens should be prioritized.

One support person plays an important role in optimal labor outcome and should be permitted at the hospital. All support persons should wear a surgical or procedure mask.

Nitrous oxide for labor anesthesia should not be used during the pandemic because it might cause aerosolization of respiratory secretions, endangering health care workers. Neuraxial anesthesia is an optimal approach to labor anesthesia.

Labor management and timing of delivery does not need to be altered during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, pregnant women with moderate or severe COVID-19 disease who are not improving may have a modest improvement in respiratory function if they are delivered preterm.

At the beginning of the COVID pandemic, the CDC recommended separation of a COVID-positive mother and her newborn until the mother’s respiratory symptoms resolved. However, the CDC now recommends that, for a COVID-positive mother, joint decision-making should be used to decide whether to support the baby rooming-in with the mother or to practice separation of mother and baby at birth to reduce the risk for postnatal infection from mother to newborn. There is no evidence that breast milk contains virus that can cause an infection. One option is for the mother who recently tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 to provide newborn nutrition with expressed breast milk.

Pregnant women with COVID-19 may be at increased risk for venous thromboembolism. Some experts recommend that hospitalized pregnant women and postpartum women with COVID-19 receive thromboembolism prophylaxis.

The Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention described a classification system for COVID-19 disease, including 3 categories18:

- mild: no dyspnea, no pneumonia, or mild pneumonia

- severe: dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥ 30 breaths per minute, blood oxygen saturation ≤ 93%, lung infiltrates > 50% within 48 hours of onset of symptoms

- critical: respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction or failure.

Among 72,314 cases in China, 81% had mild disease, 14% had severe disease, and 5% had critical disease. In a report of 118 pregnant women in China, 92% of the women had mild disease; 8% had severe disease (hypoxemia), one of whom developed critical disease requiring mechanical ventilation.19 In this cohort, the most common presenting symptoms were fever (75%), cough (73%), chest tightness (18%), fatigue (17%), shortness of breath (7%), diarrhea (7%), and headache (6%). Lymphopenia was present in 44% of the women.

Severe and critical COVID-19 disease are associated with elevations in D-dimer, C-reactive protein, troponin, ferritin, and creatine phosphokinase levels. These markers return to the normal range with resolution of disease.

Continue to: Gynecologic care...

Gynecologic care

Gynecologists are highly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Most state governments have requested that all elective surgery be suspended for the duration of the pandemic in order to redeploy health resources to the care of COVID-19 patients. Except for high-priority gynecologic surgery, including cancer surgery, treatment of heavy vaginal bleeding, and surgical care of ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage, most gynecologic surgery has ceased.

All office visits for routine gynecologic care have been suspended. Video and telephone visits can be used for contraceptive counseling and prescribing and for managing problems associated with the menopause, endometriosis, and vaginitis. Cervical cancer screening can be deferred for 3 to 6 months, depending on patient risk factors.

Medicines to treat COVID-19 infections

There are many highly effective medicines to manage HIV infection and medicines that cure hepatitis C. There is an urgent need to develop precision medicines to treat this disease. Early in the pandemic some experts thought that hydroxychloroquine might be helpful in the treatment of COVID-19 disease. But recent evidence suggests that hydroxychloroquine is probably not an effective treatment. As the pandemic has evolved, there is evidence that remdesivir may have modest efficacy in treating COVID-19 disease.20 Remdesivir has received emergency-use authorization by the FDA to treat COVID-19 infection.

Remdesivir

Based on expert opinion, in the absence of high-quality clinical trial evidence, our current practice is to offer pregnant women with severe or critical COVID-19 disease treatment with remdesivir.

Remdesivir (Gilead Sciences, Inc) is a nucleoside analog that inhibits RNA synthesis. A dose regimen for remdesivir is a 200-mg loading dose given intravenously, followed by 100 mg daily given intravenously for 5 to 10 days. Remdesivir may cause elevation of hepatic enzymes. Remdesivir has been administered to a few pregnant women to treat Ebola and Marburg virus disease.21

Experts in infectious disease are important resources for determining optimal medication regimens for the treatment of COVID-19 disease in pregnant women.

Continue to: Convalescent serum...

Convalescent serum

There are no high-quality studies demonstrating the efficacy of convalescent serum for treatment of COVID-19. A small case series suggests that there may be modest benefit to treatment of people with severe COVID-19 disease with convalescent serum.22

Testing for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies

We may have a serious problem in our current approach to detecting COVID-19 disease. Based on measurement of IgM and IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein, our current nucleic acid tests for SARS-CoV-2 may detect less than 80% of infections early in the course of disease. In two studies of IgM and IgG antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein, a single polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2 had less than a 60% sensitivity for detecting the virus.23,24 During the second week of COVID-19 illness, IgM or IgG antibodies were detected in greater than 89% of infected patients.23 Severe disease resulted in high concentrations of antibody.

When testing for IgM and IgG antibodies is widely available, it may become an option to test all health care workers. This will permit the assignment of those health care workers with the highest levels of antibody to frontline duties with COVID-19 patients during the next disease outbreak, likely to occur at some point during the next 12 months.

A COVID-19 vaccine

Dozens of research teams, including pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies and many academic laboratories, are working on developing and testing vaccines to prevent COVID-19 disease. An effective vaccine would reduce the number of people who develop severe disease during the next outbreak, reducing deaths, avoiding a shutdown of the country, and allowing the health systems to function normally. A vaccine is unlikely to be widely available until sometime early in 2021.

Facing COVID-19 well-being and mental health

SARS-CoV-2, like all viral particles, is incredibly small. Remarkably, it has changed permanently life on earth. COVID-19 is affecting our physical health, psychological well-being, economics, and patterns of social interaction. As clinicians it is difficult to face a viral enemy that cannot be stopped from causing the death of more than 100,000 people, including some of our clinical colleagues, within a short period of time.

- F—focus on what is in your control

- A—acknowledge your thoughts and feelings

- C—come back to a focus on your body

- E—engage in what you are doing

- C—commit to acting effectively based on your core values

- O—opening up to difficult feelings and being kind to yourself and others

- V—values should guide your actions

- I—identify resources for help, assistance, support, and advice

- D—disinfect and practice social distancing.

This war will come to an end

During the American Revolution, colonists faced housing and food insecurity, epidemics of typhus and smallpox, traumatic injury including amputation of limbs, and a complete disruption of normal life activities. They persevered and, against the odds, successfully concluded the war. Unlike the colonists, who did not know if their conflict would end with success or failure, we clinicians know that the COVID-19 pandemic will end. We also know that eventually the global community of clinicians will develop and deploy the effective weapons we need to prevent a recurrence of this traumatic pandemic: population-wide testing for both the SARS-CoV-2 virus and serologic testing for IgG and IgM antibodies to the virus, effective antiviral medications, and a potent vaccine. ●

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens [published online March 11, 2020]. JAMA . doi: 10.1001/ jama . 2020 .3786.

- World Health Organization. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations. March 29, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations. Accessed April 16, 2020.

- Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State [published online March 19, 2020]. JAMA . doi: 10.1001/ jama . 2020 .4326.

- Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, et al; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis [published online March 26, 2020]. Eur Respir J . doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547- 2020 .

- Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy [published online March 23, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/ jama . 2020 .4683.

- Wei WE, Li Z, Chiew CJ, et al. Presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 - Singapore, January 23 to March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2020;69:411-415.

- Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19 [published online February 21, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/ jama . 2020 .2565.

- Ong SW, Tan YK, Chia PY, et al. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient [published online March 4, 2020]. JAMA . doi: 10.1001/ jama .2020.3227.

- Fineberg HV. Rapid expert consultation on the possibility of bioaerosol spread of SARS-CoV-2 for the COVID-19 pandemic. April 1, 2020. https://www.nap.edu/read/25769/chapter/1. Accessed April 16, 2020.

- Santarpia JL, River DN, Herrera V, et al. Transmission potential of SARS-CoV-2 in viral shedding observed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. MedRxiv. March 26, 2020. doi.org10.1101/2020.03.23.20039466.

- Liu Y, Ning Z, Chen Y, et al. Aerodynamic characteristics and RNA concentration of SARS-CoV-2 aerosol in Wuhan Hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak. BioRxiv. March 10, 2020. doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.08.982637.

- Klompas M, Morris CA, Sinclair J, et al. Universal masking in hospitals in the COVID-19 era [published online April 1, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006372.

- Liu D, Li L, Wu X, et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a preliminary analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1-6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23072.

- Di Mascio D, Khalik A, Saccone G, et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.

100107. - Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens [published online March 11, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786.

- Dong L, Tian J, He S, et al. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn [published online March 26, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/ jama .2020.4621.

- Zeng H, Xu C, Fan J, et al. Antibodies in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 pneumonia [published online March 26, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/ jama .2020.4861.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Diease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [published online February 24, 2020]. JAMA . doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Chen L, Li Q, Zheng D, et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China [published online April 17, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi 10.1056/NEJMc2009226.

- Chen Z, Hu J, Zhang Z, et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. MedRxiv. April 10, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.20040758.

- Maulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT Jr, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2293-2303.

- Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, et al. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma [published online March 27, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/ jama . 2020 .4783.

- Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019 [published online March 29, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344.

- Guo L, Ren L, Yang S, et al. Profiling early humoral response to diagnose novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [published online March 21, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa310.

On June 17, 1775, American colonists, defending a forward redoubt on Breed’s Hill, ran out of gunpowder, and their position was overrun by British troops. The Battle of Bunker Hill resulted in the death of 140 colonists and 226 British soldiers, setting the stage for major combat throughout the colonies. American colonists lacked many necessary weapons. They had almost no gunpowder, few field cannons, and no warships. Yet, they fought on with the weapons at hand for 6 long years.

In the spring of 2020, American society has been shaken by the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals have been overrun with thousands of people infected with the disease. Some hospitals are breaking under the crush of intensely ill people filling up and spilling out of intensive care units. We are in a war, fighting a viral disease with a limited supply of weapons. We do not have access to the most powerful medical munitions: easily available rapid testing, proven antiviral medications, and an effective vaccine. Nevertheless, clinicians and patients are courageous, and we will continue the fight with the limited weapons we have until the pandemic is brought to an end.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus is aptly named because it is usually transmitted through close contact with respiratory droplets. The disease can progress acutely, and some people experience a remarkably severe respiratory syndrome, including tachypnea, hypoxia, and interstitial and alveolar opacities on chest x-ray, necessitating ventilatory support. The virus is an encapsulated single-stranded RNA virus. When viewed by electron microscopy, the virus appears to have a halo or crown, hence it is named “coronavirus.” Among infected individuals, the virus is present in the upper respiratory system and in feces but not in urine.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) believes that respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces are the major routes of transmission.2 The highest risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease occurs in people with one or more of the following characteristics: age greater than 70 years, hypertension, diabetes, respiratory disease, heart disease, and immunosuppression.3,4 Pregnant women do not appear to be at increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease.4 The case fatality rate is highest in people 80 years of age or older.5

Who is infected with SARS-CoV-2?

Rapid high-fidelity testing for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid sequences would be the best approach to identifying people with COVID-19 disease. At the beginning of the pandemic, testing was strictly rationed because of lack of reagents and test swabs. Clinicians were permitted to test only a minority of people who had symptoms. Asymptomatic individuals were not eligible to be tested. This terribly flawed approach to screening permitted a vast army of SARS-CoV-2–positive asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic people to circulate unchecked in the general population, infecting dozens of other people, some of whom developed moderate or severe disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported on 7 independent clusters of COVID-19 disease, each of which appear to have been caused by one asymptomatic infected individual.6 Another cluster of COVID-19 disease from China appears to have been caused by one asymptomatic infected individual.7 Based on limited data, it appears that there may be a 1- to 3-day window where an individual with COVID-19 may be asymptomatic and able to infect others. I suspect that we will soon discover, based on testing for the presence of high-titre anti SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, that many people with no history of illness and people with mild respiratory symptoms had an undiagnosed COVID-19 infection.

As testing capacity expands we likely will be testing all women, including asymptomatic women, before they arrive at the hospital for childbirth or gynecologic surgery, as well as all inpatients and women with respiratory symptoms having an ambulatory encounter.

With expanded testing capability, some pregnant women who were symptomatic and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 have had sequential long-term follow-up testing. A frequent observation is that over one to two weeks the viral symptoms resolve and the nasopharyngeal test becomes negative for SARS-CoV-2 on multiple sequential tests, only to become positive at a later date. The cause of the positive-negative-negative-positive test results is unknown, but it raises the possibility that once a person tests positive for SARS-CoV-2, they may be able to transmit the infection over many weeks, even after viral symptoms resolve.

Continue to: COVID-19: Respiratory droplet or aerosol transmission?

COVID-19: Respiratory droplet or aerosol transmission?

Respiratory droplets are large particles (> 5 µm in diameter) that tend to be pulled to the ground or furniture surfaces by gravity. Respiratory droplets do not circulate in the air for an extended period of time. Droplet nuclei are small particles less than 5 µm in diameter. These small particles may become aerosolized and float through the air for an extended period of time. The CDC and WHO believe that under ordinary conditions, SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted through respiratory droplets and contact routes.2 In an analysis of more than 75,000 COVID-19 cases in China there were no reports of transmission by aerosolized airborne virus. Therefore, under ordinary conditions, surgical masks, face shields, gowns, and gloves provide a high level of protection from infection.8

In contrast to the WHO’s perspective, Dr. Harvey Fineberg, Chair of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats, wrote a letter to the federal Office of Science and Technology Policy warning that normal breathing might generate aerosolization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and result in airborne transmission.9 A report from the University of Nebraska Medical Center supports the concept of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. In a study of 13 patients with COVID-19, room surfaces, toilet facilities, and air had evidence of viral contamination.10 The investigators concluded that disease spreads through respiratory droplets, person-to-person touch, contaminated surfaces, and airborne routes. Other investigators also have reported that aersolization of SARS-CoV-2 may occur.11 Professional societies recommend that all medical staff caring for potential or confirmed COVID-19 patients should use personal protective equipment (PPE), including respirators (N95 respirators) when available. Importantly, all medical staff should be trained in and adhere to proper donning and doffing of PPE. The controversy about the modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 will continue, but as clinicians we need to work within the constraints of the equipment we have.

Certain medical procedures and devices are known to generate aerosolization of respiratory secretions. These procedures and devices include: bronchoscopy, intubation, extubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, nebulization, high-flow oxygen masks, and continuous- and bilevel-positive airway pressure devices. When aerosols are generated during the care of a patient with COVID-19, surgical masks are not sufficient protection against infection. When an aerosol is generated maximal protection of health care workers from viral transmission requires use of a negative-pressure room and an N95 respirator or powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) device. However, negative-pressure rooms, N95 masks, and PAPRs are in very short supply or are unavailable in some health systems. We are lucky at our hospital that all of the labor rooms can be configured to operate in a negative-pressure mode, limiting potential airborne spread of the virus on the unit. Many hospitals restrict the use of N95 masks to anesthesiologists, leaving nurses, ObGyns, and surgical technicians without the best protective equipment, risking their health. As one action to reduce aerosolization of virus, obstetricians can markedly reduce the use of oxygen masks and nasal cannulas by laboring women.

Universal use of surgical masks and mouth-nose coverings

During the entire COVID-19 pandemic, PPE has been in short supply, including severe shortages of N95 masks, PAPRs, and in some health systems, surgical masks, gowns, eye protection, and face shields. Given the severe shortages, some clinicians have needed to conserve PPE, using the same PPE across multiple patient encounters and across multiple work shifts.

Given that the virus is transmitted by respiratory droplets and contaminated surfaces, use of face coverings, including surgical masks, face shields, and gloves is critically important. Scrupulous hand hygiene is a simple approach to reducing infection risk. In my health system, all employees are required to wear a surgical mask, all day every day, requiring distribution of 35,000 masks daily.12 We also require every patient and visitor to our health care facilities to use a face mask. The purpose of the procedure or surgical mask is to prevent presymptomatic spread of COVID-19 from an asymptomatic health care worker to an uninfected patient or a colleague by reducing the transmission of respiratory droplets. Another benefit is to protect the uninfected health care worker from patients and colleagues who are infected and not yet diagnosed with COVID-19. The CDC now recommends that all people wear a mouth and nose covering when they are outside of their residence. America may become a nation where wearing masks in public becomes a routine practice. Since SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted by respiratory droplets, social distancing is an important preventive measure.

Continue to: Obstetric care...

Obstetric care

Can it be repeated too often? No. Containing COVID-19 disease requires social distancing, fastidious hand hygiene, and using a mask that covers the mouth and nose.

Pregnant women should be advised to assiduously practice social distancing and to wear a face covering or mask in public. Hand hygiene should be emphasized. Pregnant women with children should be advised to not allow their children to play with non‒cohabiting children because children may be asymptomatic vectors for COVID-19.

Pregnant health care workers should stop face-to-face contact with patients after 36 weeks’ gestation to avoid a late pregnancy infection that might cause the mother to be separated from her newborn. Based on data currently available, pregnancy in the absence of another risk factor is not a major risk factor for developing severe COVID-19 disease.13

Hyperthermia is a common feature of COVID-19. Acetaminophen is recommended treatment to suppress pyrexia during pregnancy.