User login

Reworked OxyContin fails to cut overall opioid abuse, FDA panel says

The long-awaited postmarketing studies of the abuse-deterrent formulation (ADF) of OxyContin (Perdue Pharma) received mixed reviews from a Food and Drug Administration joint advisory committee.

After a 2-day discussion of new research submitted by Perdue, as well as other relevant published data, most members of the Drug Safety and Risk Management and Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products advisory committees came to the conclusion that the reformulated drug “meaningfully” reduced abuse via intranasal administration and intravenous injection, but not overall opioid abuse or overdose.

The reformulated OxyContin “was the first out of the gate,” and “has the greatest market penetration of any ADF” so “it gives us the greatest opportunity to measure change before and after reformulation,” said committee member Traci C. Green, PhD, MSc, professor and director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, Waltham, Mass.

The FDA approved the original formulation of OxyContin (oxycodone hydrochloride), a mu-receptor opioid agonist, in December 1995 for the management of pain requiring daily round-the-clock opioid treatment in cases where other treatments were inadequate. It approved an ADF version of the product in April 2010.

The updated formulation incorporates polyethylene oxide, an inactive polymer that makes the tablet harder and more crush resistant. The tablet turns into a gel or glue-like substance when wet.

At the request of the FDA, the company carried out four postmarketing studies, which the FDA also reviewed.

- A National Addictions Vigilance Intervention and Prevention Program study that included 66,897 assessments in patients undergoing evaluation for substance use or entering an opioid addiction program. Results showed a drop in up to 52% of self-reported past 30-day OxyContin injection and snorting versus comparators, including extended-release morphine and immediate-release hydrocodone.

- An analysis of 308,465 calls to U.S. poison centers showing a reduction of up to 28% for calls regarding intentional OxyContin-related exposures immediately following the drug’s reformulation. However, the FDA analysis concluded it is unclear whether the decline was attributable to the drug’s reformulation or co-occurring trends.

- A study of 63,528 individuals entering methadone clinics or treatment programs that showed a reduction of up to 27% in OxyContin abuse versus comparators. There was no information on route of abuse. Here, the FDA analysis determined the results were mixed and didn’t provide compelling evidence.

- A claims-based analysis of patients who were dispensed an opioid (297,836 OxyContin; 659,673 a comparator) that showed no evidence that the updated product affected the rate of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses.

During the meeting, committee members heard that opioid use in the United States peaked in 2012, with 260 million prescriptions dispensed, then declined by 41% by 2019. ADFs accounted for only 2% of prescriptions in 2019. They also heard that results of a wide variety of studies and surveys support the conclusion that misuse, abuse, and diversion of OxyContin decreased after it was reformulated.

Ultimately, the joint committee voted 20 to 7 (with 1 abstention) that the reformulated drug reduced nonoral abuse. Most members who voted in favor cited the NAVIPPRO study as a reason for their decision, but few found the strength of the evidence better than moderate.

Meeting chair Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, MD, professor of epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, noted the reduction in abuse may, in part, be a result of the overall reduction in opioid use.

Jon E. Zibbell, PhD, senior public health scientist, behavioral health research division, RTI International, Atlanta, who voted “no,” was disappointed there was not more data.

“We had a bunch of years for this and so many of us could have done some amazing studies” related to how abuse changed post reformulation, he said.

As for overall abuse deterrence, the committee believed the evidence was less compelling. Only two members voted that the reformulated version of the drug reduced overall abuse and only one member voted that the reformulated tablets reduced opioid overdose.

Members generally agreed that all of the studies had limitations, including retrospective designs, confounding, and potential misclassifications. Many noted the challenge of assessing abuse pre- and post reformulation given the evolving situation.

For instance, at the time the reformulated drug was launched, public health initiatives targeting opioid abuse were introduced, more treatment centers were opening, and there was a crackdown on “pill-mill” doctors.

In addition, prescribing and consumption habits were changing. Some doctors may have switched only “at-risk” patients to the reformulated opioid and there may have been “self-selection” among patients – with some potentially opting for another drug such as immediate-release oxycodone.

During the meeting, there was discussion about how to interpret a “meaningful” abuse reduction. However, there was no consensus of a percentage the reduction had to reach in order to be deemed meaningful.

Another issue discussed was the term “abuse deterrent,” which some members believed was stigmatizing and should be changed to crush resistant.

There was also concern that prescribers might consider the ADF a “safe” or less addictive opioid. Michael Sprintz, DO, clinical assistant professor, division of geriatric and palliative medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said ADFs might provide physicians with “a false sense of security.”

Dr. Sprintz, also founder of the Sprintz Center for Pain and Recovery, noted the importance of pain medicine physicians understanding addiction and addiction specialists understanding pain management.

Other committee members voiced concern that the reformulation results in patients switching from intravenous and intranasal abuse to oral abuse. Committed abusers can still swallow multiple pills.

Some members noted that reformulated OxyContin coincided with increased transition to heroin, which is relatively cheap and readily available. However, they recognized that proving causality is difficult.

The committee was reminded that the reformulated drug provides a significant barrier against, but doesn’t altogether eliminate, opioid abuse. With hot water and the right tools, the tablets can still be manipulated.

In addition, the reformulated drug will not solve the U.S. opioid epidemic, which requires a multifaceted approach. The opioid crisis, said Wilson Compton, MD, deputy director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, has resulted in a “skyrocketing” of deaths linked to “tremendously potent” forms of fentanyl, emerging stimulant use issues, and the possible increase in drug overdoses linked to COVID-19.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-awaited postmarketing studies of the abuse-deterrent formulation (ADF) of OxyContin (Perdue Pharma) received mixed reviews from a Food and Drug Administration joint advisory committee.

After a 2-day discussion of new research submitted by Perdue, as well as other relevant published data, most members of the Drug Safety and Risk Management and Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products advisory committees came to the conclusion that the reformulated drug “meaningfully” reduced abuse via intranasal administration and intravenous injection, but not overall opioid abuse or overdose.

The reformulated OxyContin “was the first out of the gate,” and “has the greatest market penetration of any ADF” so “it gives us the greatest opportunity to measure change before and after reformulation,” said committee member Traci C. Green, PhD, MSc, professor and director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, Waltham, Mass.

The FDA approved the original formulation of OxyContin (oxycodone hydrochloride), a mu-receptor opioid agonist, in December 1995 for the management of pain requiring daily round-the-clock opioid treatment in cases where other treatments were inadequate. It approved an ADF version of the product in April 2010.

The updated formulation incorporates polyethylene oxide, an inactive polymer that makes the tablet harder and more crush resistant. The tablet turns into a gel or glue-like substance when wet.

At the request of the FDA, the company carried out four postmarketing studies, which the FDA also reviewed.

- A National Addictions Vigilance Intervention and Prevention Program study that included 66,897 assessments in patients undergoing evaluation for substance use or entering an opioid addiction program. Results showed a drop in up to 52% of self-reported past 30-day OxyContin injection and snorting versus comparators, including extended-release morphine and immediate-release hydrocodone.

- An analysis of 308,465 calls to U.S. poison centers showing a reduction of up to 28% for calls regarding intentional OxyContin-related exposures immediately following the drug’s reformulation. However, the FDA analysis concluded it is unclear whether the decline was attributable to the drug’s reformulation or co-occurring trends.

- A study of 63,528 individuals entering methadone clinics or treatment programs that showed a reduction of up to 27% in OxyContin abuse versus comparators. There was no information on route of abuse. Here, the FDA analysis determined the results were mixed and didn’t provide compelling evidence.

- A claims-based analysis of patients who were dispensed an opioid (297,836 OxyContin; 659,673 a comparator) that showed no evidence that the updated product affected the rate of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses.

During the meeting, committee members heard that opioid use in the United States peaked in 2012, with 260 million prescriptions dispensed, then declined by 41% by 2019. ADFs accounted for only 2% of prescriptions in 2019. They also heard that results of a wide variety of studies and surveys support the conclusion that misuse, abuse, and diversion of OxyContin decreased after it was reformulated.

Ultimately, the joint committee voted 20 to 7 (with 1 abstention) that the reformulated drug reduced nonoral abuse. Most members who voted in favor cited the NAVIPPRO study as a reason for their decision, but few found the strength of the evidence better than moderate.

Meeting chair Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, MD, professor of epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, noted the reduction in abuse may, in part, be a result of the overall reduction in opioid use.

Jon E. Zibbell, PhD, senior public health scientist, behavioral health research division, RTI International, Atlanta, who voted “no,” was disappointed there was not more data.

“We had a bunch of years for this and so many of us could have done some amazing studies” related to how abuse changed post reformulation, he said.

As for overall abuse deterrence, the committee believed the evidence was less compelling. Only two members voted that the reformulated version of the drug reduced overall abuse and only one member voted that the reformulated tablets reduced opioid overdose.

Members generally agreed that all of the studies had limitations, including retrospective designs, confounding, and potential misclassifications. Many noted the challenge of assessing abuse pre- and post reformulation given the evolving situation.

For instance, at the time the reformulated drug was launched, public health initiatives targeting opioid abuse were introduced, more treatment centers were opening, and there was a crackdown on “pill-mill” doctors.

In addition, prescribing and consumption habits were changing. Some doctors may have switched only “at-risk” patients to the reformulated opioid and there may have been “self-selection” among patients – with some potentially opting for another drug such as immediate-release oxycodone.

During the meeting, there was discussion about how to interpret a “meaningful” abuse reduction. However, there was no consensus of a percentage the reduction had to reach in order to be deemed meaningful.

Another issue discussed was the term “abuse deterrent,” which some members believed was stigmatizing and should be changed to crush resistant.

There was also concern that prescribers might consider the ADF a “safe” or less addictive opioid. Michael Sprintz, DO, clinical assistant professor, division of geriatric and palliative medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said ADFs might provide physicians with “a false sense of security.”

Dr. Sprintz, also founder of the Sprintz Center for Pain and Recovery, noted the importance of pain medicine physicians understanding addiction and addiction specialists understanding pain management.

Other committee members voiced concern that the reformulation results in patients switching from intravenous and intranasal abuse to oral abuse. Committed abusers can still swallow multiple pills.

Some members noted that reformulated OxyContin coincided with increased transition to heroin, which is relatively cheap and readily available. However, they recognized that proving causality is difficult.

The committee was reminded that the reformulated drug provides a significant barrier against, but doesn’t altogether eliminate, opioid abuse. With hot water and the right tools, the tablets can still be manipulated.

In addition, the reformulated drug will not solve the U.S. opioid epidemic, which requires a multifaceted approach. The opioid crisis, said Wilson Compton, MD, deputy director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, has resulted in a “skyrocketing” of deaths linked to “tremendously potent” forms of fentanyl, emerging stimulant use issues, and the possible increase in drug overdoses linked to COVID-19.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-awaited postmarketing studies of the abuse-deterrent formulation (ADF) of OxyContin (Perdue Pharma) received mixed reviews from a Food and Drug Administration joint advisory committee.

After a 2-day discussion of new research submitted by Perdue, as well as other relevant published data, most members of the Drug Safety and Risk Management and Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products advisory committees came to the conclusion that the reformulated drug “meaningfully” reduced abuse via intranasal administration and intravenous injection, but not overall opioid abuse or overdose.

The reformulated OxyContin “was the first out of the gate,” and “has the greatest market penetration of any ADF” so “it gives us the greatest opportunity to measure change before and after reformulation,” said committee member Traci C. Green, PhD, MSc, professor and director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, Waltham, Mass.

The FDA approved the original formulation of OxyContin (oxycodone hydrochloride), a mu-receptor opioid agonist, in December 1995 for the management of pain requiring daily round-the-clock opioid treatment in cases where other treatments were inadequate. It approved an ADF version of the product in April 2010.

The updated formulation incorporates polyethylene oxide, an inactive polymer that makes the tablet harder and more crush resistant. The tablet turns into a gel or glue-like substance when wet.

At the request of the FDA, the company carried out four postmarketing studies, which the FDA also reviewed.

- A National Addictions Vigilance Intervention and Prevention Program study that included 66,897 assessments in patients undergoing evaluation for substance use or entering an opioid addiction program. Results showed a drop in up to 52% of self-reported past 30-day OxyContin injection and snorting versus comparators, including extended-release morphine and immediate-release hydrocodone.

- An analysis of 308,465 calls to U.S. poison centers showing a reduction of up to 28% for calls regarding intentional OxyContin-related exposures immediately following the drug’s reformulation. However, the FDA analysis concluded it is unclear whether the decline was attributable to the drug’s reformulation or co-occurring trends.

- A study of 63,528 individuals entering methadone clinics or treatment programs that showed a reduction of up to 27% in OxyContin abuse versus comparators. There was no information on route of abuse. Here, the FDA analysis determined the results were mixed and didn’t provide compelling evidence.

- A claims-based analysis of patients who were dispensed an opioid (297,836 OxyContin; 659,673 a comparator) that showed no evidence that the updated product affected the rate of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses.

During the meeting, committee members heard that opioid use in the United States peaked in 2012, with 260 million prescriptions dispensed, then declined by 41% by 2019. ADFs accounted for only 2% of prescriptions in 2019. They also heard that results of a wide variety of studies and surveys support the conclusion that misuse, abuse, and diversion of OxyContin decreased after it was reformulated.

Ultimately, the joint committee voted 20 to 7 (with 1 abstention) that the reformulated drug reduced nonoral abuse. Most members who voted in favor cited the NAVIPPRO study as a reason for their decision, but few found the strength of the evidence better than moderate.

Meeting chair Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, MD, professor of epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, noted the reduction in abuse may, in part, be a result of the overall reduction in opioid use.

Jon E. Zibbell, PhD, senior public health scientist, behavioral health research division, RTI International, Atlanta, who voted “no,” was disappointed there was not more data.

“We had a bunch of years for this and so many of us could have done some amazing studies” related to how abuse changed post reformulation, he said.

As for overall abuse deterrence, the committee believed the evidence was less compelling. Only two members voted that the reformulated version of the drug reduced overall abuse and only one member voted that the reformulated tablets reduced opioid overdose.

Members generally agreed that all of the studies had limitations, including retrospective designs, confounding, and potential misclassifications. Many noted the challenge of assessing abuse pre- and post reformulation given the evolving situation.

For instance, at the time the reformulated drug was launched, public health initiatives targeting opioid abuse were introduced, more treatment centers were opening, and there was a crackdown on “pill-mill” doctors.

In addition, prescribing and consumption habits were changing. Some doctors may have switched only “at-risk” patients to the reformulated opioid and there may have been “self-selection” among patients – with some potentially opting for another drug such as immediate-release oxycodone.

During the meeting, there was discussion about how to interpret a “meaningful” abuse reduction. However, there was no consensus of a percentage the reduction had to reach in order to be deemed meaningful.

Another issue discussed was the term “abuse deterrent,” which some members believed was stigmatizing and should be changed to crush resistant.

There was also concern that prescribers might consider the ADF a “safe” or less addictive opioid. Michael Sprintz, DO, clinical assistant professor, division of geriatric and palliative medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said ADFs might provide physicians with “a false sense of security.”

Dr. Sprintz, also founder of the Sprintz Center for Pain and Recovery, noted the importance of pain medicine physicians understanding addiction and addiction specialists understanding pain management.

Other committee members voiced concern that the reformulation results in patients switching from intravenous and intranasal abuse to oral abuse. Committed abusers can still swallow multiple pills.

Some members noted that reformulated OxyContin coincided with increased transition to heroin, which is relatively cheap and readily available. However, they recognized that proving causality is difficult.

The committee was reminded that the reformulated drug provides a significant barrier against, but doesn’t altogether eliminate, opioid abuse. With hot water and the right tools, the tablets can still be manipulated.

In addition, the reformulated drug will not solve the U.S. opioid epidemic, which requires a multifaceted approach. The opioid crisis, said Wilson Compton, MD, deputy director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, has resulted in a “skyrocketing” of deaths linked to “tremendously potent” forms of fentanyl, emerging stimulant use issues, and the possible increase in drug overdoses linked to COVID-19.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

One in seven high schoolers is misusing opioids

according to an analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

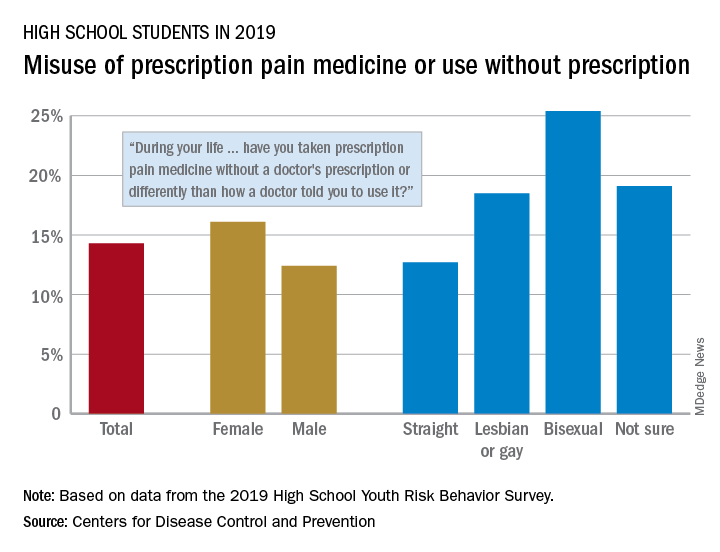

That type of opioid use/misuse, reported by 14.3% of respondents to the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, was more common among females (16.1%) than males (12.4%) and even more prevalent among nonheterosexuals and those who are unsure about their sexual identity, Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, DrPH, and associates at the CDC said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The YRBS data show that 18.5% of gay or lesbian students had, at some point in their lives, used a prescription opioid differently than a physician had told them to or taken one without a prescription. That figure was slightly higher (19.1%) for those unsure of their sexual identity, considerably higher (25.4%) for bisexuals, and lower for heterosexuals (12.7%), they reported.

The pattern for current use/misuse of opioids, defined as use one or more times in the 30 days before the survey, was similar to ever use but somewhat less pronounced in 2019. Prevalence was 7.2% for all students in grades 9-12, 8.3% for females, and 6.1% for males. By sexual identity, prevalence was 6.4% for heterosexuals, 7.6% for gays or lesbians, 11.5% for those unsure about their sexual identity, and 13.1% for bisexuals, based on the YRBS data.

This increased misuse of opioids among sexual minority youths, “even after controlling for other demographic and substance use characteristics ... emphasizes the importance of identifying tailored prevention strategies to address disparities among this vulnerable population,” the CDC researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Jones CM et al. MMWR Suppl. 2020 Aug 21;69(1):38-46.

according to an analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

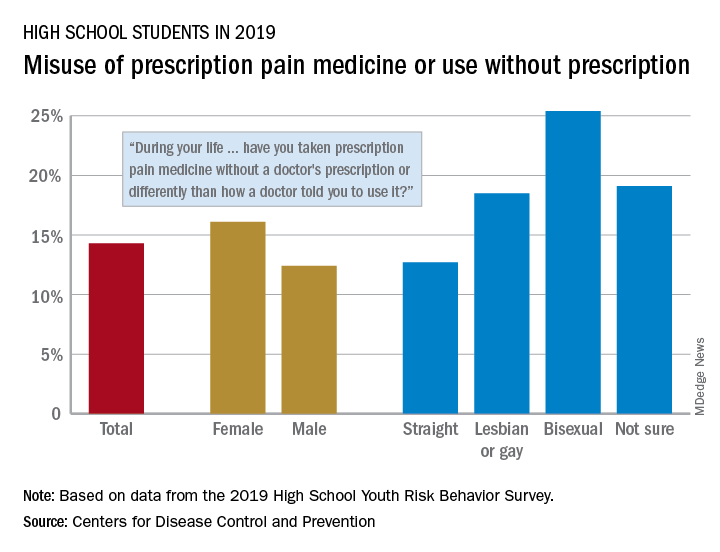

That type of opioid use/misuse, reported by 14.3% of respondents to the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, was more common among females (16.1%) than males (12.4%) and even more prevalent among nonheterosexuals and those who are unsure about their sexual identity, Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, DrPH, and associates at the CDC said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The YRBS data show that 18.5% of gay or lesbian students had, at some point in their lives, used a prescription opioid differently than a physician had told them to or taken one without a prescription. That figure was slightly higher (19.1%) for those unsure of their sexual identity, considerably higher (25.4%) for bisexuals, and lower for heterosexuals (12.7%), they reported.

The pattern for current use/misuse of opioids, defined as use one or more times in the 30 days before the survey, was similar to ever use but somewhat less pronounced in 2019. Prevalence was 7.2% for all students in grades 9-12, 8.3% for females, and 6.1% for males. By sexual identity, prevalence was 6.4% for heterosexuals, 7.6% for gays or lesbians, 11.5% for those unsure about their sexual identity, and 13.1% for bisexuals, based on the YRBS data.

This increased misuse of opioids among sexual minority youths, “even after controlling for other demographic and substance use characteristics ... emphasizes the importance of identifying tailored prevention strategies to address disparities among this vulnerable population,” the CDC researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Jones CM et al. MMWR Suppl. 2020 Aug 21;69(1):38-46.

according to an analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

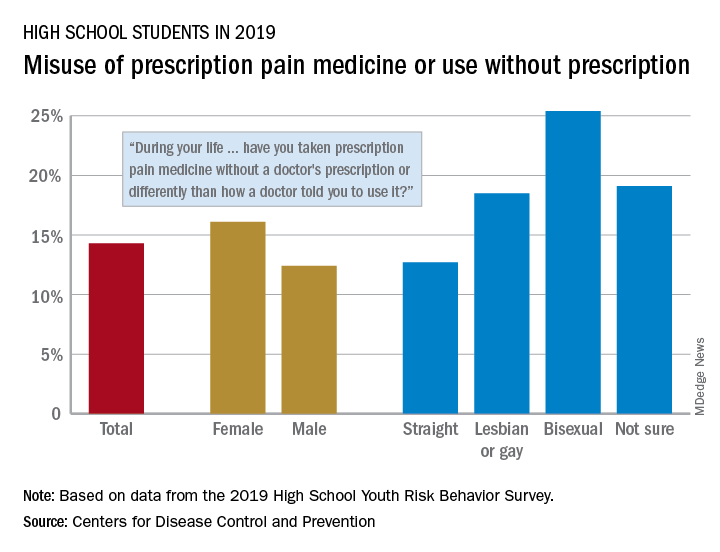

That type of opioid use/misuse, reported by 14.3% of respondents to the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, was more common among females (16.1%) than males (12.4%) and even more prevalent among nonheterosexuals and those who are unsure about their sexual identity, Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, DrPH, and associates at the CDC said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The YRBS data show that 18.5% of gay or lesbian students had, at some point in their lives, used a prescription opioid differently than a physician had told them to or taken one without a prescription. That figure was slightly higher (19.1%) for those unsure of their sexual identity, considerably higher (25.4%) for bisexuals, and lower for heterosexuals (12.7%), they reported.

The pattern for current use/misuse of opioids, defined as use one or more times in the 30 days before the survey, was similar to ever use but somewhat less pronounced in 2019. Prevalence was 7.2% for all students in grades 9-12, 8.3% for females, and 6.1% for males. By sexual identity, prevalence was 6.4% for heterosexuals, 7.6% for gays or lesbians, 11.5% for those unsure about their sexual identity, and 13.1% for bisexuals, based on the YRBS data.

This increased misuse of opioids among sexual minority youths, “even after controlling for other demographic and substance use characteristics ... emphasizes the importance of identifying tailored prevention strategies to address disparities among this vulnerable population,” the CDC researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Jones CM et al. MMWR Suppl. 2020 Aug 21;69(1):38-46.

FROM MMWR

Deaths, despair tied to drug dependence are accelerating amid COVID-19

Patients with OUDs need assistance now more than ever.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported recently that opioid overdose deaths will increase to a new U.S. record, and more are expected as pandemic-related overdose deaths are yet to be counted.1

Specifically, according to the CDC, 70,980 people died from fatal overdoses in 2019,2 which is record high. Experts such as Bruce A. Goldberger, PhD, fear that the 2020 numbers could rise even higher, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

Deaths from drug overdoses remain higher than the peak yearly death totals ever recorded for car accidents, guns, or AIDS. Overdose deaths have accelerated further – pushing down overall life expectancy in the United States.3 Headlines purporting to identify good news in drug death figures don’t always get below top-level data. Deaths and despair tied to drug dependence are indeed accelerating. I am concerned about these alarmingly dangerous trends.

Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl accounted for about 3,000 deaths in 2013. By 2019, they accounted for more than 37,137.4 In addition, 16,539 deaths involved stimulants such as methamphetamine, and 16,196 deaths involved cocaine, the most recent CDC reporting shows. Opioids continue to play a role in U.S. “deaths of despair,” or rising fatalities from drugs, suicides, and alcohol among Americans without employment, hope of job opportunities, or college degrees.5 As the American Medical Association has warned,6 more people are dying from overdoses amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians need to be aware of trends so that we can help our patients navigate these challenges.

Fentanyl presents dangers

Experts had predicted that the pandemic, by limiting access to treatment, rescue, or overdose services, and increasing time at home and in the neighborhood, would result in more tragedy. In addition, the shift from prescription opioids to heroin and now to fentanyl has made deaths more common.

Fentanyls – synthetic opioids – are involved in more than half of overdose deaths, and in many of the cocaine and methamphetamine-related deaths, which also are on the rise. Fentanyl is about 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. Breathing can stop after use of just 2 mg of fentanyl, which is about as much as trace amounts of table salt. Fentanyl has replaced heroin in many cities as the pandemic changed the relative ease of importing raw drugs such as heroin.

Another important trend is that fentanyl production and distribution throughout the United States have expanded. The ease of manufacture in unregulated sectors of the Chinese and Mexican economies is difficult for U.S. authorities to curb or eliminate. The Internet promotes novel strategies for synthesizing the substance, spreading its production across many labs; suppliers use the U.S. Postal Service for distribution, and e-commerce helps to get the drug from manufacturers to U.S. consumers for fentanyl transactions.

A recent RAND report observes that, for only $10 through the postal service, suppliers can ship a 1-kg parcel from China to the United States, and private shipments cost about $100.7 And with large volumes of legal trade between the two countries making rigorous scrutiny of products difficult, especially given the light weight of fentanyl, suppliers find it relatively easy to hide illicit substances in licit shipments. Opioid users have made the switch to fentanyl, and have seen fentanyl added to cocaine and methamphetamine they buy on the streets.

OUD and buprenorphine

Fentanyl is one part of the overdose crisis. Opioid use disorder (OUD) is the other. Both need to be addressed if we are to make any progress in this epidemic of death and dependency.

The OUD crisis continues amid the pandemic – and isn’t going away.8 Slips, relapses, and overdoses are all too common. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and OUD treatment programs are essential parts of our response to overdose initiatives. After naloxone rescue, the best anti-overdose response is to get the OUD patient into treatment with MATs. Patients with OUD have continuously high risks of overdose. The best outcomes appear to be related to treatment duration of greater than 2 years. But it is common to see patients with OUDs who have been in treatment multiple times, taking MATs, dropping out, overdosing, and dying. Some have been described as treatment resistant.9 It is clear that treatment can work, but also that even evidence-based treatments often fail.10

A recent study compared OUD patients who continued treatment for 6-9 months to those patients who had continued MAT treatment for 15-18 months. The longer the treatment, the fewer emergencies, prescriptions, or hospitalizations.11

But this study reminds us that all OUD patients, whether they are currently buprenorphine treated or not, experience overdoses and emergency department interventions. Short and longer treatment groups have a similar nonfatal overdose rate, about 6%, and went to the emergency department at a high rate, above 40%. Discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment is a major risk factor in opioid relapse, emergency department visits, and overdose. Cures are not common. Whether an OUD patient is being treated or has been treated in the past, carrying naloxone (brand name Narcan), makes sense and can save lives.

Methadone still considered most effective

Methadone is a synthetic opioid first studied as a treatment for OUD at Rockefeller University in New York City in the 1960s. Methadone may be the most effective treatment for OUD in promoting treatment retention for years, decreasing intravenous drug use, and decreasing deaths.12 It has been studied and safely used in treatment programs for decades. Methadone is typically administered in a clinic, daily, and with observation. In addition, methadone patients periodically take urine drug tests, which can distinguish methadone from substances of abuse. They also receive counseling. But methadone can be prescribed and administered only in methadone clinics in the United States. It is available for prescription in primary care clinics in Great Britain, Canada, and Australia.13 Numerous experts have suggested passing new legislation aimed at changing how methadone can be prescribed. Allowing primary care to administer methadone, just like buprenorphine, can improve access and benefit OUD patients.12

Availability of Narcan is critical

A comprehensive treatment model for OUDs includes prescribing naloxone, encouraging those patients with an OUD and their loved ones to have naloxone with them, and providing MATs and appropriate therapies, such as counseling.

As described by Allison L. Pitt and colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University,14 the United States might be on track to have up to 500,000 deaths tied to opioid overdoses that might occur over the next 5 years. They modeled the effect on overdose of a long list of interventions, but only a few had an impact. At the top of the list was naloxone availability. We need to focus on saving lives by increasing naloxone availability, improving initiation, and expanding access to MAT, and increasing psychosocial treatment to improve outcomes, increase life-years and quality-adjusted life-years, and reduce opioid-related deaths. When Ms. Pitt and colleagues looked at what would make the most impact in reducing OUD deaths, it was naloxone. Pain patients on higher doses of opioids, nonprescription opioid users, OUD patients should be given naloxone prescriptions. While many can give a Heimlich to a choking person or CPR, few have naloxone to rescue a person who has overdosed on opioids. If an overdose is suspected, it should be administered by anyone who has it, as soon as possible. Then, the person who is intervening should call 911.

What we can do today

At this moment, clinicians can follow the Surgeon General’s advice,15 and prescribe naloxone.

We should give naloxone to OUD patients and their families, to pain patients at dosages of greater than or equal to 50 MME. Our top priorities should be patients with comorbid pain syndromes, those being treated with benzodiazepines and sleeping medications, and patients with alcohol use disorders. This is also an important intervention for those who binge drink, and have sleep apnea, and heart and respiratory diseases.

Naloxone is available without a prescription in at least 43 states. Naloxone is available in harm reduction programs and in hospitals, and is carried by emergency medical staff, law enforcement, and EMTs. It also is available on the streets, though it does not appear to have a dollar value like opioids or even buprenorphine. Also, the availability of naloxone in pharmacies has made it easier for family members and caregivers of pain patients or those with OUD to have it to administer in an emergency.

An excellent place for MDs to start is to do more to encourage all patients with OUD to carry naloxone, for their loved ones to carry naloxone, and for their homes to have naloxone nearby in the bedroom or bathroom. It is not logical to expect a person with an OUD to rescue themselves. Current and past OUD patients, as well as their loved ones, are at high risk – and should have naloxone nearby at all times.

Naloxone reverses an opioid overdose, but it should be thought about like cardioversion or CPR rather than a treatment for an underlying disease. Increasing access to buprenorphine, buprenorphine + naloxone, and naltrexone treatment for OUDs is an important organizing principle. Initiation of MAT treatment in the emergency setting or most anywhere and any place a patient with an OUD can begin treatment is necessary. Treatment with buprenorphine or methadone reduces opioid overdose and opioid-related acute care use.16

Reducing racial disparities in OUD treatment is necessary, because buprenorphine treatment is concentrated among White patients who either use private insurance or are self-pay.17 Reducing barriers to methadone program licenses, expanding sites for distribution,18 prescribing methadone in an office setting might help. Clinicians can do a better job of explaining the risks associated with opioid prescriptions, including diversion and overdose, and the benefits of OUD treatment. So, To reduce opioid overdoses, we must increase physician competencies in addiction medicine.

Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University, St. Louis. He is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. For more than 40 years, Dr. Gold has worked on developing models for understanding the effects of opioid, tobacco, cocaine, and other drugs, as well as food, on the brain and behavior. He disclosed financial ties with ADAPT Pharma and Magstim Ltd.

References

1. Kamp J. Overdose deaths rise, may reach record level, federal data show. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Jul 15.

2. 12 month–ending provisional number of drug overdose drugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Jul 5.

3. Katz J et al. In shadow of pandemic, U.S. drug overdose deaths resurge to record. New York Times. 2020 Jul 15.

4. Gold MS. The fentanyl crisis is only getting worse. Addiction Policy Forum. Updated 2020 Mar 12.

5. Gold MS. Mo Med. 2020-Mar-Apr;117(2):99-101.

6. Reports of increases in opioid-related overdoses and other concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Medical Association. Issue brief. Updated 2020 Jul 20.

7. Pardo B et al. The future of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. RAND report.

8. Gold MS. New challenges in the opioid epidemic. Addiction Policy Forum. 2020 Jun 4.

9. Patterson Silver Wolf DA and Gold MS. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116718.

10. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(10):2072-86.

11. Connery HS and Weiss RD. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(2):104-6.

12. Kleber HD. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2303-5.

13. Samet JH et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):7-8.

14. Pitt AL et al. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1394-1400.

15. U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Naloxone and Opioid Overdose. hhs.gov.

16. Wakeman SE et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622.

17. Lagisetty PA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979-81.

18. Kleinman RA. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 15. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1624.

Patients with OUDs need assistance now more than ever.

Patients with OUDs need assistance now more than ever.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported recently that opioid overdose deaths will increase to a new U.S. record, and more are expected as pandemic-related overdose deaths are yet to be counted.1

Specifically, according to the CDC, 70,980 people died from fatal overdoses in 2019,2 which is record high. Experts such as Bruce A. Goldberger, PhD, fear that the 2020 numbers could rise even higher, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

Deaths from drug overdoses remain higher than the peak yearly death totals ever recorded for car accidents, guns, or AIDS. Overdose deaths have accelerated further – pushing down overall life expectancy in the United States.3 Headlines purporting to identify good news in drug death figures don’t always get below top-level data. Deaths and despair tied to drug dependence are indeed accelerating. I am concerned about these alarmingly dangerous trends.

Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl accounted for about 3,000 deaths in 2013. By 2019, they accounted for more than 37,137.4 In addition, 16,539 deaths involved stimulants such as methamphetamine, and 16,196 deaths involved cocaine, the most recent CDC reporting shows. Opioids continue to play a role in U.S. “deaths of despair,” or rising fatalities from drugs, suicides, and alcohol among Americans without employment, hope of job opportunities, or college degrees.5 As the American Medical Association has warned,6 more people are dying from overdoses amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians need to be aware of trends so that we can help our patients navigate these challenges.

Fentanyl presents dangers

Experts had predicted that the pandemic, by limiting access to treatment, rescue, or overdose services, and increasing time at home and in the neighborhood, would result in more tragedy. In addition, the shift from prescription opioids to heroin and now to fentanyl has made deaths more common.

Fentanyls – synthetic opioids – are involved in more than half of overdose deaths, and in many of the cocaine and methamphetamine-related deaths, which also are on the rise. Fentanyl is about 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. Breathing can stop after use of just 2 mg of fentanyl, which is about as much as trace amounts of table salt. Fentanyl has replaced heroin in many cities as the pandemic changed the relative ease of importing raw drugs such as heroin.

Another important trend is that fentanyl production and distribution throughout the United States have expanded. The ease of manufacture in unregulated sectors of the Chinese and Mexican economies is difficult for U.S. authorities to curb or eliminate. The Internet promotes novel strategies for synthesizing the substance, spreading its production across many labs; suppliers use the U.S. Postal Service for distribution, and e-commerce helps to get the drug from manufacturers to U.S. consumers for fentanyl transactions.

A recent RAND report observes that, for only $10 through the postal service, suppliers can ship a 1-kg parcel from China to the United States, and private shipments cost about $100.7 And with large volumes of legal trade between the two countries making rigorous scrutiny of products difficult, especially given the light weight of fentanyl, suppliers find it relatively easy to hide illicit substances in licit shipments. Opioid users have made the switch to fentanyl, and have seen fentanyl added to cocaine and methamphetamine they buy on the streets.

OUD and buprenorphine

Fentanyl is one part of the overdose crisis. Opioid use disorder (OUD) is the other. Both need to be addressed if we are to make any progress in this epidemic of death and dependency.

The OUD crisis continues amid the pandemic – and isn’t going away.8 Slips, relapses, and overdoses are all too common. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and OUD treatment programs are essential parts of our response to overdose initiatives. After naloxone rescue, the best anti-overdose response is to get the OUD patient into treatment with MATs. Patients with OUD have continuously high risks of overdose. The best outcomes appear to be related to treatment duration of greater than 2 years. But it is common to see patients with OUDs who have been in treatment multiple times, taking MATs, dropping out, overdosing, and dying. Some have been described as treatment resistant.9 It is clear that treatment can work, but also that even evidence-based treatments often fail.10

A recent study compared OUD patients who continued treatment for 6-9 months to those patients who had continued MAT treatment for 15-18 months. The longer the treatment, the fewer emergencies, prescriptions, or hospitalizations.11

But this study reminds us that all OUD patients, whether they are currently buprenorphine treated or not, experience overdoses and emergency department interventions. Short and longer treatment groups have a similar nonfatal overdose rate, about 6%, and went to the emergency department at a high rate, above 40%. Discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment is a major risk factor in opioid relapse, emergency department visits, and overdose. Cures are not common. Whether an OUD patient is being treated or has been treated in the past, carrying naloxone (brand name Narcan), makes sense and can save lives.

Methadone still considered most effective

Methadone is a synthetic opioid first studied as a treatment for OUD at Rockefeller University in New York City in the 1960s. Methadone may be the most effective treatment for OUD in promoting treatment retention for years, decreasing intravenous drug use, and decreasing deaths.12 It has been studied and safely used in treatment programs for decades. Methadone is typically administered in a clinic, daily, and with observation. In addition, methadone patients periodically take urine drug tests, which can distinguish methadone from substances of abuse. They also receive counseling. But methadone can be prescribed and administered only in methadone clinics in the United States. It is available for prescription in primary care clinics in Great Britain, Canada, and Australia.13 Numerous experts have suggested passing new legislation aimed at changing how methadone can be prescribed. Allowing primary care to administer methadone, just like buprenorphine, can improve access and benefit OUD patients.12

Availability of Narcan is critical

A comprehensive treatment model for OUDs includes prescribing naloxone, encouraging those patients with an OUD and their loved ones to have naloxone with them, and providing MATs and appropriate therapies, such as counseling.

As described by Allison L. Pitt and colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University,14 the United States might be on track to have up to 500,000 deaths tied to opioid overdoses that might occur over the next 5 years. They modeled the effect on overdose of a long list of interventions, but only a few had an impact. At the top of the list was naloxone availability. We need to focus on saving lives by increasing naloxone availability, improving initiation, and expanding access to MAT, and increasing psychosocial treatment to improve outcomes, increase life-years and quality-adjusted life-years, and reduce opioid-related deaths. When Ms. Pitt and colleagues looked at what would make the most impact in reducing OUD deaths, it was naloxone. Pain patients on higher doses of opioids, nonprescription opioid users, OUD patients should be given naloxone prescriptions. While many can give a Heimlich to a choking person or CPR, few have naloxone to rescue a person who has overdosed on opioids. If an overdose is suspected, it should be administered by anyone who has it, as soon as possible. Then, the person who is intervening should call 911.

What we can do today

At this moment, clinicians can follow the Surgeon General’s advice,15 and prescribe naloxone.

We should give naloxone to OUD patients and their families, to pain patients at dosages of greater than or equal to 50 MME. Our top priorities should be patients with comorbid pain syndromes, those being treated with benzodiazepines and sleeping medications, and patients with alcohol use disorders. This is also an important intervention for those who binge drink, and have sleep apnea, and heart and respiratory diseases.

Naloxone is available without a prescription in at least 43 states. Naloxone is available in harm reduction programs and in hospitals, and is carried by emergency medical staff, law enforcement, and EMTs. It also is available on the streets, though it does not appear to have a dollar value like opioids or even buprenorphine. Also, the availability of naloxone in pharmacies has made it easier for family members and caregivers of pain patients or those with OUD to have it to administer in an emergency.

An excellent place for MDs to start is to do more to encourage all patients with OUD to carry naloxone, for their loved ones to carry naloxone, and for their homes to have naloxone nearby in the bedroom or bathroom. It is not logical to expect a person with an OUD to rescue themselves. Current and past OUD patients, as well as their loved ones, are at high risk – and should have naloxone nearby at all times.

Naloxone reverses an opioid overdose, but it should be thought about like cardioversion or CPR rather than a treatment for an underlying disease. Increasing access to buprenorphine, buprenorphine + naloxone, and naltrexone treatment for OUDs is an important organizing principle. Initiation of MAT treatment in the emergency setting or most anywhere and any place a patient with an OUD can begin treatment is necessary. Treatment with buprenorphine or methadone reduces opioid overdose and opioid-related acute care use.16

Reducing racial disparities in OUD treatment is necessary, because buprenorphine treatment is concentrated among White patients who either use private insurance or are self-pay.17 Reducing barriers to methadone program licenses, expanding sites for distribution,18 prescribing methadone in an office setting might help. Clinicians can do a better job of explaining the risks associated with opioid prescriptions, including diversion and overdose, and the benefits of OUD treatment. So, To reduce opioid overdoses, we must increase physician competencies in addiction medicine.

Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University, St. Louis. He is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. For more than 40 years, Dr. Gold has worked on developing models for understanding the effects of opioid, tobacco, cocaine, and other drugs, as well as food, on the brain and behavior. He disclosed financial ties with ADAPT Pharma and Magstim Ltd.

References

1. Kamp J. Overdose deaths rise, may reach record level, federal data show. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Jul 15.

2. 12 month–ending provisional number of drug overdose drugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Jul 5.

3. Katz J et al. In shadow of pandemic, U.S. drug overdose deaths resurge to record. New York Times. 2020 Jul 15.

4. Gold MS. The fentanyl crisis is only getting worse. Addiction Policy Forum. Updated 2020 Mar 12.

5. Gold MS. Mo Med. 2020-Mar-Apr;117(2):99-101.

6. Reports of increases in opioid-related overdoses and other concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Medical Association. Issue brief. Updated 2020 Jul 20.

7. Pardo B et al. The future of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. RAND report.

8. Gold MS. New challenges in the opioid epidemic. Addiction Policy Forum. 2020 Jun 4.

9. Patterson Silver Wolf DA and Gold MS. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116718.

10. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(10):2072-86.

11. Connery HS and Weiss RD. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(2):104-6.

12. Kleber HD. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2303-5.

13. Samet JH et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):7-8.

14. Pitt AL et al. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1394-1400.

15. U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Naloxone and Opioid Overdose. hhs.gov.

16. Wakeman SE et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622.

17. Lagisetty PA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979-81.

18. Kleinman RA. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 15. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1624.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported recently that opioid overdose deaths will increase to a new U.S. record, and more are expected as pandemic-related overdose deaths are yet to be counted.1

Specifically, according to the CDC, 70,980 people died from fatal overdoses in 2019,2 which is record high. Experts such as Bruce A. Goldberger, PhD, fear that the 2020 numbers could rise even higher, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

Deaths from drug overdoses remain higher than the peak yearly death totals ever recorded for car accidents, guns, or AIDS. Overdose deaths have accelerated further – pushing down overall life expectancy in the United States.3 Headlines purporting to identify good news in drug death figures don’t always get below top-level data. Deaths and despair tied to drug dependence are indeed accelerating. I am concerned about these alarmingly dangerous trends.

Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl accounted for about 3,000 deaths in 2013. By 2019, they accounted for more than 37,137.4 In addition, 16,539 deaths involved stimulants such as methamphetamine, and 16,196 deaths involved cocaine, the most recent CDC reporting shows. Opioids continue to play a role in U.S. “deaths of despair,” or rising fatalities from drugs, suicides, and alcohol among Americans without employment, hope of job opportunities, or college degrees.5 As the American Medical Association has warned,6 more people are dying from overdoses amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians need to be aware of trends so that we can help our patients navigate these challenges.

Fentanyl presents dangers

Experts had predicted that the pandemic, by limiting access to treatment, rescue, or overdose services, and increasing time at home and in the neighborhood, would result in more tragedy. In addition, the shift from prescription opioids to heroin and now to fentanyl has made deaths more common.

Fentanyls – synthetic opioids – are involved in more than half of overdose deaths, and in many of the cocaine and methamphetamine-related deaths, which also are on the rise. Fentanyl is about 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. Breathing can stop after use of just 2 mg of fentanyl, which is about as much as trace amounts of table salt. Fentanyl has replaced heroin in many cities as the pandemic changed the relative ease of importing raw drugs such as heroin.

Another important trend is that fentanyl production and distribution throughout the United States have expanded. The ease of manufacture in unregulated sectors of the Chinese and Mexican economies is difficult for U.S. authorities to curb or eliminate. The Internet promotes novel strategies for synthesizing the substance, spreading its production across many labs; suppliers use the U.S. Postal Service for distribution, and e-commerce helps to get the drug from manufacturers to U.S. consumers for fentanyl transactions.

A recent RAND report observes that, for only $10 through the postal service, suppliers can ship a 1-kg parcel from China to the United States, and private shipments cost about $100.7 And with large volumes of legal trade between the two countries making rigorous scrutiny of products difficult, especially given the light weight of fentanyl, suppliers find it relatively easy to hide illicit substances in licit shipments. Opioid users have made the switch to fentanyl, and have seen fentanyl added to cocaine and methamphetamine they buy on the streets.

OUD and buprenorphine

Fentanyl is one part of the overdose crisis. Opioid use disorder (OUD) is the other. Both need to be addressed if we are to make any progress in this epidemic of death and dependency.

The OUD crisis continues amid the pandemic – and isn’t going away.8 Slips, relapses, and overdoses are all too common. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and OUD treatment programs are essential parts of our response to overdose initiatives. After naloxone rescue, the best anti-overdose response is to get the OUD patient into treatment with MATs. Patients with OUD have continuously high risks of overdose. The best outcomes appear to be related to treatment duration of greater than 2 years. But it is common to see patients with OUDs who have been in treatment multiple times, taking MATs, dropping out, overdosing, and dying. Some have been described as treatment resistant.9 It is clear that treatment can work, but also that even evidence-based treatments often fail.10

A recent study compared OUD patients who continued treatment for 6-9 months to those patients who had continued MAT treatment for 15-18 months. The longer the treatment, the fewer emergencies, prescriptions, or hospitalizations.11

But this study reminds us that all OUD patients, whether they are currently buprenorphine treated or not, experience overdoses and emergency department interventions. Short and longer treatment groups have a similar nonfatal overdose rate, about 6%, and went to the emergency department at a high rate, above 40%. Discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment is a major risk factor in opioid relapse, emergency department visits, and overdose. Cures are not common. Whether an OUD patient is being treated or has been treated in the past, carrying naloxone (brand name Narcan), makes sense and can save lives.

Methadone still considered most effective

Methadone is a synthetic opioid first studied as a treatment for OUD at Rockefeller University in New York City in the 1960s. Methadone may be the most effective treatment for OUD in promoting treatment retention for years, decreasing intravenous drug use, and decreasing deaths.12 It has been studied and safely used in treatment programs for decades. Methadone is typically administered in a clinic, daily, and with observation. In addition, methadone patients periodically take urine drug tests, which can distinguish methadone from substances of abuse. They also receive counseling. But methadone can be prescribed and administered only in methadone clinics in the United States. It is available for prescription in primary care clinics in Great Britain, Canada, and Australia.13 Numerous experts have suggested passing new legislation aimed at changing how methadone can be prescribed. Allowing primary care to administer methadone, just like buprenorphine, can improve access and benefit OUD patients.12

Availability of Narcan is critical

A comprehensive treatment model for OUDs includes prescribing naloxone, encouraging those patients with an OUD and their loved ones to have naloxone with them, and providing MATs and appropriate therapies, such as counseling.

As described by Allison L. Pitt and colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University,14 the United States might be on track to have up to 500,000 deaths tied to opioid overdoses that might occur over the next 5 years. They modeled the effect on overdose of a long list of interventions, but only a few had an impact. At the top of the list was naloxone availability. We need to focus on saving lives by increasing naloxone availability, improving initiation, and expanding access to MAT, and increasing psychosocial treatment to improve outcomes, increase life-years and quality-adjusted life-years, and reduce opioid-related deaths. When Ms. Pitt and colleagues looked at what would make the most impact in reducing OUD deaths, it was naloxone. Pain patients on higher doses of opioids, nonprescription opioid users, OUD patients should be given naloxone prescriptions. While many can give a Heimlich to a choking person or CPR, few have naloxone to rescue a person who has overdosed on opioids. If an overdose is suspected, it should be administered by anyone who has it, as soon as possible. Then, the person who is intervening should call 911.

What we can do today

At this moment, clinicians can follow the Surgeon General’s advice,15 and prescribe naloxone.

We should give naloxone to OUD patients and their families, to pain patients at dosages of greater than or equal to 50 MME. Our top priorities should be patients with comorbid pain syndromes, those being treated with benzodiazepines and sleeping medications, and patients with alcohol use disorders. This is also an important intervention for those who binge drink, and have sleep apnea, and heart and respiratory diseases.

Naloxone is available without a prescription in at least 43 states. Naloxone is available in harm reduction programs and in hospitals, and is carried by emergency medical staff, law enforcement, and EMTs. It also is available on the streets, though it does not appear to have a dollar value like opioids or even buprenorphine. Also, the availability of naloxone in pharmacies has made it easier for family members and caregivers of pain patients or those with OUD to have it to administer in an emergency.

An excellent place for MDs to start is to do more to encourage all patients with OUD to carry naloxone, for their loved ones to carry naloxone, and for their homes to have naloxone nearby in the bedroom or bathroom. It is not logical to expect a person with an OUD to rescue themselves. Current and past OUD patients, as well as their loved ones, are at high risk – and should have naloxone nearby at all times.

Naloxone reverses an opioid overdose, but it should be thought about like cardioversion or CPR rather than a treatment for an underlying disease. Increasing access to buprenorphine, buprenorphine + naloxone, and naltrexone treatment for OUDs is an important organizing principle. Initiation of MAT treatment in the emergency setting or most anywhere and any place a patient with an OUD can begin treatment is necessary. Treatment with buprenorphine or methadone reduces opioid overdose and opioid-related acute care use.16

Reducing racial disparities in OUD treatment is necessary, because buprenorphine treatment is concentrated among White patients who either use private insurance or are self-pay.17 Reducing barriers to methadone program licenses, expanding sites for distribution,18 prescribing methadone in an office setting might help. Clinicians can do a better job of explaining the risks associated with opioid prescriptions, including diversion and overdose, and the benefits of OUD treatment. So, To reduce opioid overdoses, we must increase physician competencies in addiction medicine.

Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University, St. Louis. He is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. For more than 40 years, Dr. Gold has worked on developing models for understanding the effects of opioid, tobacco, cocaine, and other drugs, as well as food, on the brain and behavior. He disclosed financial ties with ADAPT Pharma and Magstim Ltd.

References

1. Kamp J. Overdose deaths rise, may reach record level, federal data show. Wall Street Journal. 2020 Jul 15.

2. 12 month–ending provisional number of drug overdose drugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Jul 5.

3. Katz J et al. In shadow of pandemic, U.S. drug overdose deaths resurge to record. New York Times. 2020 Jul 15.

4. Gold MS. The fentanyl crisis is only getting worse. Addiction Policy Forum. Updated 2020 Mar 12.

5. Gold MS. Mo Med. 2020-Mar-Apr;117(2):99-101.

6. Reports of increases in opioid-related overdoses and other concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Medical Association. Issue brief. Updated 2020 Jul 20.

7. Pardo B et al. The future of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. RAND report.

8. Gold MS. New challenges in the opioid epidemic. Addiction Policy Forum. 2020 Jun 4.

9. Patterson Silver Wolf DA and Gold MS. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116718.

10. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(10):2072-86.

11. Connery HS and Weiss RD. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(2):104-6.

12. Kleber HD. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2303-5.

13. Samet JH et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):7-8.

14. Pitt AL et al. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1394-1400.

15. U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Naloxone and Opioid Overdose. hhs.gov.

16. Wakeman SE et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622.

17. Lagisetty PA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979-81.

18. Kleinman RA. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 15. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1624.

AMA urges change after dramatic increase in illicit opioid fatalities

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.