User login

Biomechanical Evaluation of Two Arthroscopic Biceps Tenodesis Techniques: Proximal Interference Screw and Modified Percutaneous Intra-Articular Transtendon

Over the years, operative treatment of biceps pathology has escalated, likely secondary to increased identification and successful clinical outcomes. Although its true function remains controversial, the biceps tendon has been well accepted as a primary pain generator in the anterior aspect of the shoulder.1,2 Biceps pathology involves a spectrum of often overlapping findings—varying degrees of tearing, tendinitis, and instability. Pathology may be isolated or may present in association with other shoulder conditions, including impingement, bursitis, rotator cuff tears, SLAP (superior labral tear anterior to posterior) lesions, and acromioclavicular disorders.3

Operative treatment of disease of the long head of the biceps mandates an initial choice of tenotomy or tenodesis. Which approach is superior is controversial.4-6 Although tenotomy and tenodesis have comparably favorable clinical results, tenodesis is often recommended, particularly for younger, active patients, mostly because cosmetic deformity is possible with tenotomy.

Tenodesis may be performed arthroscopically or through an open incision, and the biceps tendon may be placed anywhere from in the joint to under the tendon of the pectoralis major tendon. In many recent biomechanical studies, interference screws had higher load to failure and improved stiffness in comparison with other fixation methods.7-19 Most of those studies focused on fixation in a subpectoral location. To our knowledge, only 2 studies of soft-tissue fixation have compared the percutaneous intra-articular transtendon (PITT) technique with other popular tenodesis techniques.20,21 The PITT technique demonstrated a common failure point, with sutures pulling through the tendon substance. It was hypothesized that adding a locking loop to the PITT suture configuration would further improve fixation.

We conducted a study to compare the biomechanical characteristics of 2 techniques for all-arthroscopic proximal biceps tenodesis: bioabsorbable interference screw (Biceptor; Smith & Nephew) and a locking-loop PITT modification developed at our institution.

Methods

Sixteen nonembalmed fresh-frozen human cadaveric shoulders (8 pairs: 3 male, 5 female) were used in this study. Mean specimen age was 55 years (range, 51-59 years). The specimens showed no evidence of high-grade osteoarthritic changes, biceps tendon fraying or tearing, biceps pulley lesions, or full-thickness rotator cuff tears. They were thawed at room temperature for 24 hours before the procedure.

In each pair, 1 shoulder was randomized to be treated with 1 of 2 arthroscopic biceps tenodesis techniques—modified PITT or Biceptor interference screw—and the other shoulder was treated with the other technique. Surgery was performed in an open fashion, and every attempt was made to simulate the arthroscopic approach. In all shoulders, biomechanical testing was completed immediately after tenodesis.

Modified PITT Technique

In an outside-in fashion, an 18-gauge spinal needle was used to pierce the transverse humeral ligament, the lateral aspect of the rotator interval tissue, and the biceps tendon. A second needle was then passed in similar fashion, piercing the biceps tendon just adjacent to the first needle (Figure 1A). A 0-polydioxanone monofilament suture (0-PDS; Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson) was threaded through the first needle and used to shuttle a single No. 2 braided nonabsorbable polyethylene suture (MaxBraid; Biomet Sports Medicine) back through the biceps tendon.

At this point, the free end of the nonabsorbable suture, which comes out of the anterior cannula during an arthroscopic procedure, was passed back into the glenohumeral joint (using a suture grasper), looped over the top of the biceps tendon, and brought back out of the joint anteriorly, thereby creating a locking loop around the tendon (Figure 1B). A shuttle suture (0-PDS) passed through the second needle was used to bring that anterior limb of nonabsorbable suture back through the biceps tendon, completing the stitch configuration (Figure 1C).

This process was repeated with another nonabsorbable suture. After suture passing was completed, the biceps was detached from its insertion at the superior labrum. The 2 nonabsorbable sutures, which would later be retrieved from the subacromial space, were then tied in standard fashion, securing the biceps tendon to the transverse humeral ligament/rotator interval tissue (Figure 1D).

Biceptor Interference Screw Technique

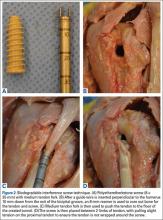

The interference screw technique was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s operative instructions.22 An 8 × 25-mm polyetheretherketone interference screw was used in all specimens, and the medium tendon fork was used to maintain tension on the biceps tendon during fixation (Figure 2A).

A 2.4-mm guide wire was inserted perpendicular to the humeral shaft, at the planned site of tenodesis, 10 mm distal to the entrance of the bicipital groove. An 8-mm cannulated reamer was passed over the wire, and a 30-mm tunnel was drilled (Figure 2B). The proximal part of the tendon was advanced into the center of the tunnel using the tendon fork (Figure 2C), and the tendon was held at the bottom of the tunnel with a 1.5-mm guide pin. The tendon fork was removed, and the cannulated interference screw was inserted over the guide pin between the 2 limbs of the biceps tendon (Figure 2D). The tendon was closely monitored to ensure it was not wrapped up when the screw was placed.

Biomechanical Testing

After each tenodesis, the humerus was amputated 5 inches distal to the fixation site. All extraneous soft tissue was dissected away, leaving the distal aspect of the biceps tendon as a free graft. Each proximal humerus–biceps tendon construct was then mounted on a materials testing machine. A custom-designed soft-tissue clamp was used to secure the distal aspect of the biceps tendon to the test actuator and load cell (Figure 3A). A custom-designed jig was used to stabilize the proximal humerus to the platform of the materials testing machine (Figure 3B). The specimens were mounted so that the line of pull throughout the testing protocol was applied parallel to the long axis of the humerus, thereby approximating the in vivo biceps force vector (Figure 3C). Digital cameras recorded each test for analysis of the mechanism of failure for each specimen. Marker dots were drawn on each tendon to assess tendon stretch before construct failure.

The tendons were preloaded to 10 N and then cycled at 0 to 50 N for 100 cycles at 1 Hz. After cyclic loading, axial load to failure was performed at a rate of 1.0 mm per second until a peak load was observed and subsequent loading led to tendon elongation with no further increase in load. Displacement and force applied during cyclic loading and load to failure were recorded. Stiffness was then calculated as the slope of the linear portion of the force-displacement curve using the least mean squares approach. Mechanism of failure was documented for each specimen.

Statistical Analysis

Analyzing our preliminary data with G*Power, we determined that a total sample size of 8 would be required (effect size [Cohen dz] was 1, α error probability was .05, power was .8). We hypothesized that the ultimate strength and stiffness of one group would be less than 1 SD above those of the other group. Paired t test with significance set at P < .05 was used to compare the techniques.

Results

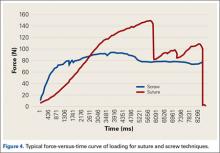

Both repair constructs exhibited standard load-displacement curves, with a linear increase in load with displacement until the point of failure, at which time further displacement occurred with no discernible increase in load (Figure 4). Ultimate load to failure is determined as the highest point of the curve, and stiffness is calculated as the slope of the load-displacement curve.

Mean axial displacement parallel to the shaft of the humerus with cyclic loading was 7.1 mm with the modified PITT technique and 7.9 mm with the interference screw technique. There was no macroscopically visible high-grade tearing or slippage of the biceps tendon in any specimen with cyclic loading for either repair construct.

Mean (SD) ultimate load to failure was significantly (P = .003) higher with the modified PITT technique, 157 (41) N, than with the interference screw technique, 107 (29) N; actual effect size (Cohen dz) was 1.19, difference of means was 50 N, and pooled SD was 42 N. The interference screw technique yielded significantly (P = .010) more mean (SD) stiffness, 38.7 (14.7) N/mm, than the modified PITT technique, 15.8 (9.1) N/mm; actual effect size (Cohen dz) was 1.37, difference of means was 22.9 N/mm, and pooled SD was 16.7 N/mm.

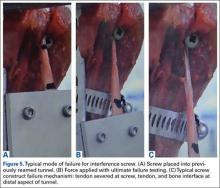

In the interference screw technique, the mode of failure was consistent. Of the 8 specimens, 7 failed at the screw–tendon interface at the distal aspect of the tunnel; in the eighth specimen, the entire tendon pulled out from under the screw construct. In the modified PITT technique, there was more variability in failure: tendon slipped through suture (4 specimens), tendon/suture construct as unit pulled through transverse ligament/rotator interval tissue (3), and suture failure (1).

Discussion

This study was the first to directly compare a bony interference screw technique with a soft-tissue technique (modified PITT). Fixation strength is crucial. A load of 112 N is applied to the long head of the biceps tendon when a person holds 1 kg of weight in the hand with the elbow at 90° flexion.22 As mean (SD) ultimate load to failure was 157 (41) N with the modified PITT technique and 107 (29) N with the interference screw technique in this study, the interference screw can be recommended only with some hesitation.

The interference screw was stiffer with cyclic loading—an expected outcome, as it was secured to rigid bone—vs soft tissue, as in the modified PITT technique. Although the clinical implications for the modified PITT technique are unknown, more than likely, with the tendon being secured to soft tissue, there will be scarring over time.

In laboratory testing of biceps tenodesis constructs, interference screw fixation has had superior load-to-failure characteristics in comparisons with other fixation methods. Golish and colleagues13 found significantly higher load to failure with a biotenodesis screw than with a double-loaded suture anchor for subpectoral tenodesis. Testing similar implants, in a location more proximal in the bicipital groove, Richards and Burkhart14 likewise found superior fixation strength with an interference screw. Ozalay and colleagues16 found superior strength in an interference screw compared with suture anchor, keyhole, and bone tunnel in sheep. In a pig model, the highest ultimate load to failure was found in an interference screw—vs keyhole, bone tunnel, suture anchor, and ligament washer.19 Load to failure for the interference screw in these studies ranged from 170 N to over 400 N.13,14,16,19

A few other investigators have studied the Biceptor interference screw. Slabaugh and colleagues15 found a mean (SD) load to failure of 173.9 (27.2) N for all specimens tested. Patzer and colleagues9,17 found that the mean (SD) ultimate load to failure with the Biceptor proximal interference screw, 173.9 (27.2) N, was superior to that of a suture anchor.

The mean (SD) ultimate load to failure reported for the Biceptor interference screw in the present study, 107 (29) N, is lower than the values reported in the other studies—not only for the Biceptor screw but for interference screws in general. Nevertheless, we performed the technique as the manufacturer recommended.22 Our results were consistent across all specimens studied. Interestingly, in the study by Slabaugh and colleagues,15 7 specimens failed at the tendon–screw interface during cyclic testing and were not included in the analysis of ultimate load to failure. As these specimens failed at a load between 5 N and 70 N, including their data would have significantly lowered the mean load to failure.

Concern over the Biceptor interference screw’s lower failure load relative to that of other interference screws has been raised before.9,17 A major issue is possible overstuffing of the humeral tunnel, as the hole is reamed the same size as the screw. With the Biceptor, the proximal and distal portions of the tendon are placed in the tunnel in a U-shaped configuration with the screw between these limbs. The idea is that the 2 biceps tendon limbs might become abraded and consecutively weaken as the screw is inserted between the tendon limbs, more so than with a single loop. This idea was suggested by the typical longitudinal tendon splitting that occurs at the screw–tendon interface at the distal aspect of the tunnel.23 In the present study, consistent failure (Figures 5A-5C) at the distal aspect of the screw–tendon junction supported the idea that the tendon is abraded during placement of the interference screw or during the friction-causing 90° turn the tendon takes into the bone on loading. There is no way to quantitatively examine tendon quality before interference screw placement, but on gross inspection all the tendons were of good quality. Slabaugh and colleagues15 also found consistent failure at the screw–tunnel interface.

The PITT technique has been described as a simple all-arthroscopic soft-tissue technique for biceps tenodesis.23,24 Subsequently developed soft-tissue techniques have demonstrated clinical benefits.25-27 Proposed advantages of these techniques are lower cost associated with decreased implant needs, no reliance on quality of bone for fixation, suturing while biceps tendon is still attached to anchor (anatomical tension is closely reproduced), and less interference with any subsequent use of magnetic resonance imaging for diagnostic purposes in the shoulder.

There have been only 2 biomechanical studies of the PITT technique. Lopez-Vidriero and colleagues20 compared the biomechanical properties of the PITT and suture anchor techniques in a human cadaveric laboratory study and found that the PITT technique had mean (SD) ultimate load to failure of 142.7 (30.9) N and mean (SD) stiffness of 13.3 (3) N/mm. They observed consistent suture pullout through the tendon substance during failure, which suggests the most important factor for strength is the quality of the biceps tendon. Su and colleagues21 found biomechanically inferior results of the classic PITT technique as compared with the interference screw technique.

This article provides the first description of the modified PITT technique. Our mean (SD) load to failure of the modified PITT technique was 157 (41) N, slightly higher than that reported for the classic PITT technique, albeit under a different setup.20 There was more variation in ultimate load to failure in our study than in previous studies, which could be secondary to tissue quality. As the modified PITT technique relies on surrounding tissue holding the biceps in place, this tissue would need to be of good quality and strength to obtain strong fixation. A possible concern is that placing stitches in the rotator interval could increase the risk of shoulder stiffness, but this has not been encountered clinically.

A more variable mechanism of failure was also found in the present study. Although half the specimens failed by suture pullout through the tendon, similar to what Lopez-Vidriero and colleagues20 described, 3 of our 8 specimens failed with the entire biceps tendon–suture construct pulling through the transverse ligament tissue, and 1 specimen failed by suture breakage. Although these numbers are too small for making definitive statements, our modified PITT technique may add some security to the tendon–suture construct. Such added security may be of particular value in the setting of poor-quality, diseased tendon tissue, and the construct may be more limited by the strength of surrounding tissues. In addition, if failure occurs at the suture transverse humeral ligament–rotator interval interface, more surrounding rotator interval tissue can be incorporated into the tenodesis to decrease the likelihood of failure through this mechanism.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a time zero study in a cadaveric model with simulated biomechanical loading. As such, it provided information only on initial fixation strength and could not prove any superior clinical outcomes or account for any biological changes with healing that occurred over time. Second, the study may have been underpowered, though sample size was chosen in accordance with other cadaveric biomechanical studies. Third, all procedures were performed in an open manner, simulating the arthroscopic approach. Particularly in the setting of the modified PITT technique, this represented a best case scenario. Spinal needles and subsequent sutures were easily passed under direct visualization through the transverse humeral ligament, rotator interval, and biceps tendon. There is likely marked variability in this step during arthroscopy in which visualization is more limited, as in the setting of concomitant procedures, such as subacromial decompression or rotator cuff repair. In addition, all tendons tested were normal in appearance and gave no indication of chronic degenerative changes.

Another study limitation is that we did not quantify bone mineral density, which if poor would have affected interference screw strength. However, mean specimen age was 55 years, minimizing chances of poor bone quality. In addition, 7 of the 8 failures in the interference screw group occurred not with pullout but at the screw–tendon junction, suggesting poor bone quality was not a significant factor. As tendon diameter was not measured before the procedures were performed, there is the possibility it could have been better in the modified PITT group and worse in the interference screw group because of tunnel crowding, as noted.

1. Alpantaki K, McLaughlin D, Karagogeos D, Hadjipavlou A, Kontakis G. Sympathetic and sensory neural elements in the tendon of the long head of the biceps. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1580-1583.

2. Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(11):645-656.

3. Khazzam M, George MS, Churchill RS, Kuhn JE. Disorders of the long head of biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):136-145.

4. Frost A, Zafar MS, Maffulli N. Tenotomy versus tenodesis in the management of pathologic lesions of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):828-833.

5. Hsu AR, Ghodadra NS, Provencher MT, Lewis PB, Bach BR. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a review of clinical outcomes and biomechanical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):326-332.

6. Slenker NR, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Dodson CC, Cohen SB. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):576-582.

7. Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Santangelo S, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1296-1306.

8. Millett PJ, Sanders B, Gobezie R, Braun S, Warner JJ. Interference screw vs. suture anchor fixation for open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: does it matter? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:121.

9. Patzer T, Rundic JM, Bobrowitsch E, Olender GD, Hurschler C, Schofer MD. Biomechanical comparison of arthroscopically performable techniques for suprapectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1036-1047.

10. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):170-176.

11. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

12. Klepps S, Hazrati Y, Flatow E. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(9):1040-1045.

13. Golish SR, Caldwell PE 3rd, Miller MD, et al. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for subpectoral tenodesis of the proximal biceps tendon: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1103-1108.

14. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. A biomechanical analysis of two biceps tenodesis fixation techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):861-866.

15. Slabaugh MA, Frank RM, Van Thiel GS, et al. Biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation: a biomechanical comparison of screw length and diameter. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(2):161-166.

16. Ozalay M, Akpinar S, Karaeminogullari O, et al. Mechanical strength of four different biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):992-998.

17. Patzer T, Santo G, Olender GD, Wellmann M, Hurschler C, Schofer MD. Suprapectoral or subpectoral position for biceps tenodesis: biomechanical comparison of four different techniques in both positions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):116-125.

18. Jayamoorthy T, Field JR, Costi JJ, Martin DK, Stanley RM, Hearn TC. Biceps tenodesis: a biomechanical study of fixation methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(2):160-164.

19. Kusma M, Dienst M, Eckert J, Steimer O, Kohn D. Tenodesis of the long head of biceps brachii: cyclic testing of five methods of fixation in a porcine model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):967-973.

20. Lopez-Vidriero E, Costic RS, Fu FH, Rodosky MW. Biomechanical evaluation of 2 arthroscopic biceps tenodeses: double anchor versus percutaneous intra-articular transtendon (PITT) techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):146-152.

21. Su WR, Budoff JE, Chiang CH, Lee CJ, Lin CL. Biomechanical study comparing biceps wedge tenodesis with other proximal long head of the biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(9):1498-1505.

22. Trenhaile SW. Biceptor Tenodesis System, Arthroscopic Biceps Tenodesis [operational instructions]. Andover, MA: Smith & Nephew; 2009:1-8.

23. Sekiya LC, Elkousy HA, Rodosky MW. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis using the percutaneous intra-articular transtendon technique. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1137-1141.

24. Elkousy HA, Fluhme DJ, O’Connor DP, Rodosky MW. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis using the percutaneous, intra-articular trans-tendon technique: preliminary results. Orthopedics. 2005;28(11):1316-1319.

25. Castagna A, Conti M, Mouhsine E, Bungaro P, Garofalo R. Arthroscopic biceps tendon tenodesis; the anchorage technical note. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(6):581-585.

26. Checchia SL, Doneux PS, Miyazaki AN, et al. Biceps tenodesis associated with arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(2):138-144.

27. Moros C, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Suture anchor and percutaneous intra-articular transtendon biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):177-179.

Over the years, operative treatment of biceps pathology has escalated, likely secondary to increased identification and successful clinical outcomes. Although its true function remains controversial, the biceps tendon has been well accepted as a primary pain generator in the anterior aspect of the shoulder.1,2 Biceps pathology involves a spectrum of often overlapping findings—varying degrees of tearing, tendinitis, and instability. Pathology may be isolated or may present in association with other shoulder conditions, including impingement, bursitis, rotator cuff tears, SLAP (superior labral tear anterior to posterior) lesions, and acromioclavicular disorders.3

Operative treatment of disease of the long head of the biceps mandates an initial choice of tenotomy or tenodesis. Which approach is superior is controversial.4-6 Although tenotomy and tenodesis have comparably favorable clinical results, tenodesis is often recommended, particularly for younger, active patients, mostly because cosmetic deformity is possible with tenotomy.

Tenodesis may be performed arthroscopically or through an open incision, and the biceps tendon may be placed anywhere from in the joint to under the tendon of the pectoralis major tendon. In many recent biomechanical studies, interference screws had higher load to failure and improved stiffness in comparison with other fixation methods.7-19 Most of those studies focused on fixation in a subpectoral location. To our knowledge, only 2 studies of soft-tissue fixation have compared the percutaneous intra-articular transtendon (PITT) technique with other popular tenodesis techniques.20,21 The PITT technique demonstrated a common failure point, with sutures pulling through the tendon substance. It was hypothesized that adding a locking loop to the PITT suture configuration would further improve fixation.

We conducted a study to compare the biomechanical characteristics of 2 techniques for all-arthroscopic proximal biceps tenodesis: bioabsorbable interference screw (Biceptor; Smith & Nephew) and a locking-loop PITT modification developed at our institution.

Methods

Sixteen nonembalmed fresh-frozen human cadaveric shoulders (8 pairs: 3 male, 5 female) were used in this study. Mean specimen age was 55 years (range, 51-59 years). The specimens showed no evidence of high-grade osteoarthritic changes, biceps tendon fraying or tearing, biceps pulley lesions, or full-thickness rotator cuff tears. They were thawed at room temperature for 24 hours before the procedure.

In each pair, 1 shoulder was randomized to be treated with 1 of 2 arthroscopic biceps tenodesis techniques—modified PITT or Biceptor interference screw—and the other shoulder was treated with the other technique. Surgery was performed in an open fashion, and every attempt was made to simulate the arthroscopic approach. In all shoulders, biomechanical testing was completed immediately after tenodesis.

Modified PITT Technique

In an outside-in fashion, an 18-gauge spinal needle was used to pierce the transverse humeral ligament, the lateral aspect of the rotator interval tissue, and the biceps tendon. A second needle was then passed in similar fashion, piercing the biceps tendon just adjacent to the first needle (Figure 1A). A 0-polydioxanone monofilament suture (0-PDS; Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson) was threaded through the first needle and used to shuttle a single No. 2 braided nonabsorbable polyethylene suture (MaxBraid; Biomet Sports Medicine) back through the biceps tendon.

At this point, the free end of the nonabsorbable suture, which comes out of the anterior cannula during an arthroscopic procedure, was passed back into the glenohumeral joint (using a suture grasper), looped over the top of the biceps tendon, and brought back out of the joint anteriorly, thereby creating a locking loop around the tendon (Figure 1B). A shuttle suture (0-PDS) passed through the second needle was used to bring that anterior limb of nonabsorbable suture back through the biceps tendon, completing the stitch configuration (Figure 1C).

This process was repeated with another nonabsorbable suture. After suture passing was completed, the biceps was detached from its insertion at the superior labrum. The 2 nonabsorbable sutures, which would later be retrieved from the subacromial space, were then tied in standard fashion, securing the biceps tendon to the transverse humeral ligament/rotator interval tissue (Figure 1D).

Biceptor Interference Screw Technique

The interference screw technique was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s operative instructions.22 An 8 × 25-mm polyetheretherketone interference screw was used in all specimens, and the medium tendon fork was used to maintain tension on the biceps tendon during fixation (Figure 2A).

A 2.4-mm guide wire was inserted perpendicular to the humeral shaft, at the planned site of tenodesis, 10 mm distal to the entrance of the bicipital groove. An 8-mm cannulated reamer was passed over the wire, and a 30-mm tunnel was drilled (Figure 2B). The proximal part of the tendon was advanced into the center of the tunnel using the tendon fork (Figure 2C), and the tendon was held at the bottom of the tunnel with a 1.5-mm guide pin. The tendon fork was removed, and the cannulated interference screw was inserted over the guide pin between the 2 limbs of the biceps tendon (Figure 2D). The tendon was closely monitored to ensure it was not wrapped up when the screw was placed.

Biomechanical Testing

After each tenodesis, the humerus was amputated 5 inches distal to the fixation site. All extraneous soft tissue was dissected away, leaving the distal aspect of the biceps tendon as a free graft. Each proximal humerus–biceps tendon construct was then mounted on a materials testing machine. A custom-designed soft-tissue clamp was used to secure the distal aspect of the biceps tendon to the test actuator and load cell (Figure 3A). A custom-designed jig was used to stabilize the proximal humerus to the platform of the materials testing machine (Figure 3B). The specimens were mounted so that the line of pull throughout the testing protocol was applied parallel to the long axis of the humerus, thereby approximating the in vivo biceps force vector (Figure 3C). Digital cameras recorded each test for analysis of the mechanism of failure for each specimen. Marker dots were drawn on each tendon to assess tendon stretch before construct failure.

The tendons were preloaded to 10 N and then cycled at 0 to 50 N for 100 cycles at 1 Hz. After cyclic loading, axial load to failure was performed at a rate of 1.0 mm per second until a peak load was observed and subsequent loading led to tendon elongation with no further increase in load. Displacement and force applied during cyclic loading and load to failure were recorded. Stiffness was then calculated as the slope of the linear portion of the force-displacement curve using the least mean squares approach. Mechanism of failure was documented for each specimen.

Statistical Analysis

Analyzing our preliminary data with G*Power, we determined that a total sample size of 8 would be required (effect size [Cohen dz] was 1, α error probability was .05, power was .8). We hypothesized that the ultimate strength and stiffness of one group would be less than 1 SD above those of the other group. Paired t test with significance set at P < .05 was used to compare the techniques.

Results

Both repair constructs exhibited standard load-displacement curves, with a linear increase in load with displacement until the point of failure, at which time further displacement occurred with no discernible increase in load (Figure 4). Ultimate load to failure is determined as the highest point of the curve, and stiffness is calculated as the slope of the load-displacement curve.

Mean axial displacement parallel to the shaft of the humerus with cyclic loading was 7.1 mm with the modified PITT technique and 7.9 mm with the interference screw technique. There was no macroscopically visible high-grade tearing or slippage of the biceps tendon in any specimen with cyclic loading for either repair construct.

Mean (SD) ultimate load to failure was significantly (P = .003) higher with the modified PITT technique, 157 (41) N, than with the interference screw technique, 107 (29) N; actual effect size (Cohen dz) was 1.19, difference of means was 50 N, and pooled SD was 42 N. The interference screw technique yielded significantly (P = .010) more mean (SD) stiffness, 38.7 (14.7) N/mm, than the modified PITT technique, 15.8 (9.1) N/mm; actual effect size (Cohen dz) was 1.37, difference of means was 22.9 N/mm, and pooled SD was 16.7 N/mm.

In the interference screw technique, the mode of failure was consistent. Of the 8 specimens, 7 failed at the screw–tendon interface at the distal aspect of the tunnel; in the eighth specimen, the entire tendon pulled out from under the screw construct. In the modified PITT technique, there was more variability in failure: tendon slipped through suture (4 specimens), tendon/suture construct as unit pulled through transverse ligament/rotator interval tissue (3), and suture failure (1).

Discussion

This study was the first to directly compare a bony interference screw technique with a soft-tissue technique (modified PITT). Fixation strength is crucial. A load of 112 N is applied to the long head of the biceps tendon when a person holds 1 kg of weight in the hand with the elbow at 90° flexion.22 As mean (SD) ultimate load to failure was 157 (41) N with the modified PITT technique and 107 (29) N with the interference screw technique in this study, the interference screw can be recommended only with some hesitation.

The interference screw was stiffer with cyclic loading—an expected outcome, as it was secured to rigid bone—vs soft tissue, as in the modified PITT technique. Although the clinical implications for the modified PITT technique are unknown, more than likely, with the tendon being secured to soft tissue, there will be scarring over time.

In laboratory testing of biceps tenodesis constructs, interference screw fixation has had superior load-to-failure characteristics in comparisons with other fixation methods. Golish and colleagues13 found significantly higher load to failure with a biotenodesis screw than with a double-loaded suture anchor for subpectoral tenodesis. Testing similar implants, in a location more proximal in the bicipital groove, Richards and Burkhart14 likewise found superior fixation strength with an interference screw. Ozalay and colleagues16 found superior strength in an interference screw compared with suture anchor, keyhole, and bone tunnel in sheep. In a pig model, the highest ultimate load to failure was found in an interference screw—vs keyhole, bone tunnel, suture anchor, and ligament washer.19 Load to failure for the interference screw in these studies ranged from 170 N to over 400 N.13,14,16,19

A few other investigators have studied the Biceptor interference screw. Slabaugh and colleagues15 found a mean (SD) load to failure of 173.9 (27.2) N for all specimens tested. Patzer and colleagues9,17 found that the mean (SD) ultimate load to failure with the Biceptor proximal interference screw, 173.9 (27.2) N, was superior to that of a suture anchor.

The mean (SD) ultimate load to failure reported for the Biceptor interference screw in the present study, 107 (29) N, is lower than the values reported in the other studies—not only for the Biceptor screw but for interference screws in general. Nevertheless, we performed the technique as the manufacturer recommended.22 Our results were consistent across all specimens studied. Interestingly, in the study by Slabaugh and colleagues,15 7 specimens failed at the tendon–screw interface during cyclic testing and were not included in the analysis of ultimate load to failure. As these specimens failed at a load between 5 N and 70 N, including their data would have significantly lowered the mean load to failure.

Concern over the Biceptor interference screw’s lower failure load relative to that of other interference screws has been raised before.9,17 A major issue is possible overstuffing of the humeral tunnel, as the hole is reamed the same size as the screw. With the Biceptor, the proximal and distal portions of the tendon are placed in the tunnel in a U-shaped configuration with the screw between these limbs. The idea is that the 2 biceps tendon limbs might become abraded and consecutively weaken as the screw is inserted between the tendon limbs, more so than with a single loop. This idea was suggested by the typical longitudinal tendon splitting that occurs at the screw–tendon interface at the distal aspect of the tunnel.23 In the present study, consistent failure (Figures 5A-5C) at the distal aspect of the screw–tendon junction supported the idea that the tendon is abraded during placement of the interference screw or during the friction-causing 90° turn the tendon takes into the bone on loading. There is no way to quantitatively examine tendon quality before interference screw placement, but on gross inspection all the tendons were of good quality. Slabaugh and colleagues15 also found consistent failure at the screw–tunnel interface.

The PITT technique has been described as a simple all-arthroscopic soft-tissue technique for biceps tenodesis.23,24 Subsequently developed soft-tissue techniques have demonstrated clinical benefits.25-27 Proposed advantages of these techniques are lower cost associated with decreased implant needs, no reliance on quality of bone for fixation, suturing while biceps tendon is still attached to anchor (anatomical tension is closely reproduced), and less interference with any subsequent use of magnetic resonance imaging for diagnostic purposes in the shoulder.

There have been only 2 biomechanical studies of the PITT technique. Lopez-Vidriero and colleagues20 compared the biomechanical properties of the PITT and suture anchor techniques in a human cadaveric laboratory study and found that the PITT technique had mean (SD) ultimate load to failure of 142.7 (30.9) N and mean (SD) stiffness of 13.3 (3) N/mm. They observed consistent suture pullout through the tendon substance during failure, which suggests the most important factor for strength is the quality of the biceps tendon. Su and colleagues21 found biomechanically inferior results of the classic PITT technique as compared with the interference screw technique.

This article provides the first description of the modified PITT technique. Our mean (SD) load to failure of the modified PITT technique was 157 (41) N, slightly higher than that reported for the classic PITT technique, albeit under a different setup.20 There was more variation in ultimate load to failure in our study than in previous studies, which could be secondary to tissue quality. As the modified PITT technique relies on surrounding tissue holding the biceps in place, this tissue would need to be of good quality and strength to obtain strong fixation. A possible concern is that placing stitches in the rotator interval could increase the risk of shoulder stiffness, but this has not been encountered clinically.

A more variable mechanism of failure was also found in the present study. Although half the specimens failed by suture pullout through the tendon, similar to what Lopez-Vidriero and colleagues20 described, 3 of our 8 specimens failed with the entire biceps tendon–suture construct pulling through the transverse ligament tissue, and 1 specimen failed by suture breakage. Although these numbers are too small for making definitive statements, our modified PITT technique may add some security to the tendon–suture construct. Such added security may be of particular value in the setting of poor-quality, diseased tendon tissue, and the construct may be more limited by the strength of surrounding tissues. In addition, if failure occurs at the suture transverse humeral ligament–rotator interval interface, more surrounding rotator interval tissue can be incorporated into the tenodesis to decrease the likelihood of failure through this mechanism.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a time zero study in a cadaveric model with simulated biomechanical loading. As such, it provided information only on initial fixation strength and could not prove any superior clinical outcomes or account for any biological changes with healing that occurred over time. Second, the study may have been underpowered, though sample size was chosen in accordance with other cadaveric biomechanical studies. Third, all procedures were performed in an open manner, simulating the arthroscopic approach. Particularly in the setting of the modified PITT technique, this represented a best case scenario. Spinal needles and subsequent sutures were easily passed under direct visualization through the transverse humeral ligament, rotator interval, and biceps tendon. There is likely marked variability in this step during arthroscopy in which visualization is more limited, as in the setting of concomitant procedures, such as subacromial decompression or rotator cuff repair. In addition, all tendons tested were normal in appearance and gave no indication of chronic degenerative changes.

Another study limitation is that we did not quantify bone mineral density, which if poor would have affected interference screw strength. However, mean specimen age was 55 years, minimizing chances of poor bone quality. In addition, 7 of the 8 failures in the interference screw group occurred not with pullout but at the screw–tendon junction, suggesting poor bone quality was not a significant factor. As tendon diameter was not measured before the procedures were performed, there is the possibility it could have been better in the modified PITT group and worse in the interference screw group because of tunnel crowding, as noted.

Over the years, operative treatment of biceps pathology has escalated, likely secondary to increased identification and successful clinical outcomes. Although its true function remains controversial, the biceps tendon has been well accepted as a primary pain generator in the anterior aspect of the shoulder.1,2 Biceps pathology involves a spectrum of often overlapping findings—varying degrees of tearing, tendinitis, and instability. Pathology may be isolated or may present in association with other shoulder conditions, including impingement, bursitis, rotator cuff tears, SLAP (superior labral tear anterior to posterior) lesions, and acromioclavicular disorders.3

Operative treatment of disease of the long head of the biceps mandates an initial choice of tenotomy or tenodesis. Which approach is superior is controversial.4-6 Although tenotomy and tenodesis have comparably favorable clinical results, tenodesis is often recommended, particularly for younger, active patients, mostly because cosmetic deformity is possible with tenotomy.

Tenodesis may be performed arthroscopically or through an open incision, and the biceps tendon may be placed anywhere from in the joint to under the tendon of the pectoralis major tendon. In many recent biomechanical studies, interference screws had higher load to failure and improved stiffness in comparison with other fixation methods.7-19 Most of those studies focused on fixation in a subpectoral location. To our knowledge, only 2 studies of soft-tissue fixation have compared the percutaneous intra-articular transtendon (PITT) technique with other popular tenodesis techniques.20,21 The PITT technique demonstrated a common failure point, with sutures pulling through the tendon substance. It was hypothesized that adding a locking loop to the PITT suture configuration would further improve fixation.

We conducted a study to compare the biomechanical characteristics of 2 techniques for all-arthroscopic proximal biceps tenodesis: bioabsorbable interference screw (Biceptor; Smith & Nephew) and a locking-loop PITT modification developed at our institution.

Methods

Sixteen nonembalmed fresh-frozen human cadaveric shoulders (8 pairs: 3 male, 5 female) were used in this study. Mean specimen age was 55 years (range, 51-59 years). The specimens showed no evidence of high-grade osteoarthritic changes, biceps tendon fraying or tearing, biceps pulley lesions, or full-thickness rotator cuff tears. They were thawed at room temperature for 24 hours before the procedure.

In each pair, 1 shoulder was randomized to be treated with 1 of 2 arthroscopic biceps tenodesis techniques—modified PITT or Biceptor interference screw—and the other shoulder was treated with the other technique. Surgery was performed in an open fashion, and every attempt was made to simulate the arthroscopic approach. In all shoulders, biomechanical testing was completed immediately after tenodesis.

Modified PITT Technique

In an outside-in fashion, an 18-gauge spinal needle was used to pierce the transverse humeral ligament, the lateral aspect of the rotator interval tissue, and the biceps tendon. A second needle was then passed in similar fashion, piercing the biceps tendon just adjacent to the first needle (Figure 1A). A 0-polydioxanone monofilament suture (0-PDS; Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson) was threaded through the first needle and used to shuttle a single No. 2 braided nonabsorbable polyethylene suture (MaxBraid; Biomet Sports Medicine) back through the biceps tendon.

At this point, the free end of the nonabsorbable suture, which comes out of the anterior cannula during an arthroscopic procedure, was passed back into the glenohumeral joint (using a suture grasper), looped over the top of the biceps tendon, and brought back out of the joint anteriorly, thereby creating a locking loop around the tendon (Figure 1B). A shuttle suture (0-PDS) passed through the second needle was used to bring that anterior limb of nonabsorbable suture back through the biceps tendon, completing the stitch configuration (Figure 1C).

This process was repeated with another nonabsorbable suture. After suture passing was completed, the biceps was detached from its insertion at the superior labrum. The 2 nonabsorbable sutures, which would later be retrieved from the subacromial space, were then tied in standard fashion, securing the biceps tendon to the transverse humeral ligament/rotator interval tissue (Figure 1D).

Biceptor Interference Screw Technique

The interference screw technique was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s operative instructions.22 An 8 × 25-mm polyetheretherketone interference screw was used in all specimens, and the medium tendon fork was used to maintain tension on the biceps tendon during fixation (Figure 2A).

A 2.4-mm guide wire was inserted perpendicular to the humeral shaft, at the planned site of tenodesis, 10 mm distal to the entrance of the bicipital groove. An 8-mm cannulated reamer was passed over the wire, and a 30-mm tunnel was drilled (Figure 2B). The proximal part of the tendon was advanced into the center of the tunnel using the tendon fork (Figure 2C), and the tendon was held at the bottom of the tunnel with a 1.5-mm guide pin. The tendon fork was removed, and the cannulated interference screw was inserted over the guide pin between the 2 limbs of the biceps tendon (Figure 2D). The tendon was closely monitored to ensure it was not wrapped up when the screw was placed.

Biomechanical Testing

After each tenodesis, the humerus was amputated 5 inches distal to the fixation site. All extraneous soft tissue was dissected away, leaving the distal aspect of the biceps tendon as a free graft. Each proximal humerus–biceps tendon construct was then mounted on a materials testing machine. A custom-designed soft-tissue clamp was used to secure the distal aspect of the biceps tendon to the test actuator and load cell (Figure 3A). A custom-designed jig was used to stabilize the proximal humerus to the platform of the materials testing machine (Figure 3B). The specimens were mounted so that the line of pull throughout the testing protocol was applied parallel to the long axis of the humerus, thereby approximating the in vivo biceps force vector (Figure 3C). Digital cameras recorded each test for analysis of the mechanism of failure for each specimen. Marker dots were drawn on each tendon to assess tendon stretch before construct failure.

The tendons were preloaded to 10 N and then cycled at 0 to 50 N for 100 cycles at 1 Hz. After cyclic loading, axial load to failure was performed at a rate of 1.0 mm per second until a peak load was observed and subsequent loading led to tendon elongation with no further increase in load. Displacement and force applied during cyclic loading and load to failure were recorded. Stiffness was then calculated as the slope of the linear portion of the force-displacement curve using the least mean squares approach. Mechanism of failure was documented for each specimen.

Statistical Analysis

Analyzing our preliminary data with G*Power, we determined that a total sample size of 8 would be required (effect size [Cohen dz] was 1, α error probability was .05, power was .8). We hypothesized that the ultimate strength and stiffness of one group would be less than 1 SD above those of the other group. Paired t test with significance set at P < .05 was used to compare the techniques.

Results

Both repair constructs exhibited standard load-displacement curves, with a linear increase in load with displacement until the point of failure, at which time further displacement occurred with no discernible increase in load (Figure 4). Ultimate load to failure is determined as the highest point of the curve, and stiffness is calculated as the slope of the load-displacement curve.

Mean axial displacement parallel to the shaft of the humerus with cyclic loading was 7.1 mm with the modified PITT technique and 7.9 mm with the interference screw technique. There was no macroscopically visible high-grade tearing or slippage of the biceps tendon in any specimen with cyclic loading for either repair construct.

Mean (SD) ultimate load to failure was significantly (P = .003) higher with the modified PITT technique, 157 (41) N, than with the interference screw technique, 107 (29) N; actual effect size (Cohen dz) was 1.19, difference of means was 50 N, and pooled SD was 42 N. The interference screw technique yielded significantly (P = .010) more mean (SD) stiffness, 38.7 (14.7) N/mm, than the modified PITT technique, 15.8 (9.1) N/mm; actual effect size (Cohen dz) was 1.37, difference of means was 22.9 N/mm, and pooled SD was 16.7 N/mm.

In the interference screw technique, the mode of failure was consistent. Of the 8 specimens, 7 failed at the screw–tendon interface at the distal aspect of the tunnel; in the eighth specimen, the entire tendon pulled out from under the screw construct. In the modified PITT technique, there was more variability in failure: tendon slipped through suture (4 specimens), tendon/suture construct as unit pulled through transverse ligament/rotator interval tissue (3), and suture failure (1).

Discussion

This study was the first to directly compare a bony interference screw technique with a soft-tissue technique (modified PITT). Fixation strength is crucial. A load of 112 N is applied to the long head of the biceps tendon when a person holds 1 kg of weight in the hand with the elbow at 90° flexion.22 As mean (SD) ultimate load to failure was 157 (41) N with the modified PITT technique and 107 (29) N with the interference screw technique in this study, the interference screw can be recommended only with some hesitation.

The interference screw was stiffer with cyclic loading—an expected outcome, as it was secured to rigid bone—vs soft tissue, as in the modified PITT technique. Although the clinical implications for the modified PITT technique are unknown, more than likely, with the tendon being secured to soft tissue, there will be scarring over time.

In laboratory testing of biceps tenodesis constructs, interference screw fixation has had superior load-to-failure characteristics in comparisons with other fixation methods. Golish and colleagues13 found significantly higher load to failure with a biotenodesis screw than with a double-loaded suture anchor for subpectoral tenodesis. Testing similar implants, in a location more proximal in the bicipital groove, Richards and Burkhart14 likewise found superior fixation strength with an interference screw. Ozalay and colleagues16 found superior strength in an interference screw compared with suture anchor, keyhole, and bone tunnel in sheep. In a pig model, the highest ultimate load to failure was found in an interference screw—vs keyhole, bone tunnel, suture anchor, and ligament washer.19 Load to failure for the interference screw in these studies ranged from 170 N to over 400 N.13,14,16,19

A few other investigators have studied the Biceptor interference screw. Slabaugh and colleagues15 found a mean (SD) load to failure of 173.9 (27.2) N for all specimens tested. Patzer and colleagues9,17 found that the mean (SD) ultimate load to failure with the Biceptor proximal interference screw, 173.9 (27.2) N, was superior to that of a suture anchor.

The mean (SD) ultimate load to failure reported for the Biceptor interference screw in the present study, 107 (29) N, is lower than the values reported in the other studies—not only for the Biceptor screw but for interference screws in general. Nevertheless, we performed the technique as the manufacturer recommended.22 Our results were consistent across all specimens studied. Interestingly, in the study by Slabaugh and colleagues,15 7 specimens failed at the tendon–screw interface during cyclic testing and were not included in the analysis of ultimate load to failure. As these specimens failed at a load between 5 N and 70 N, including their data would have significantly lowered the mean load to failure.

Concern over the Biceptor interference screw’s lower failure load relative to that of other interference screws has been raised before.9,17 A major issue is possible overstuffing of the humeral tunnel, as the hole is reamed the same size as the screw. With the Biceptor, the proximal and distal portions of the tendon are placed in the tunnel in a U-shaped configuration with the screw between these limbs. The idea is that the 2 biceps tendon limbs might become abraded and consecutively weaken as the screw is inserted between the tendon limbs, more so than with a single loop. This idea was suggested by the typical longitudinal tendon splitting that occurs at the screw–tendon interface at the distal aspect of the tunnel.23 In the present study, consistent failure (Figures 5A-5C) at the distal aspect of the screw–tendon junction supported the idea that the tendon is abraded during placement of the interference screw or during the friction-causing 90° turn the tendon takes into the bone on loading. There is no way to quantitatively examine tendon quality before interference screw placement, but on gross inspection all the tendons were of good quality. Slabaugh and colleagues15 also found consistent failure at the screw–tunnel interface.

The PITT technique has been described as a simple all-arthroscopic soft-tissue technique for biceps tenodesis.23,24 Subsequently developed soft-tissue techniques have demonstrated clinical benefits.25-27 Proposed advantages of these techniques are lower cost associated with decreased implant needs, no reliance on quality of bone for fixation, suturing while biceps tendon is still attached to anchor (anatomical tension is closely reproduced), and less interference with any subsequent use of magnetic resonance imaging for diagnostic purposes in the shoulder.

There have been only 2 biomechanical studies of the PITT technique. Lopez-Vidriero and colleagues20 compared the biomechanical properties of the PITT and suture anchor techniques in a human cadaveric laboratory study and found that the PITT technique had mean (SD) ultimate load to failure of 142.7 (30.9) N and mean (SD) stiffness of 13.3 (3) N/mm. They observed consistent suture pullout through the tendon substance during failure, which suggests the most important factor for strength is the quality of the biceps tendon. Su and colleagues21 found biomechanically inferior results of the classic PITT technique as compared with the interference screw technique.

This article provides the first description of the modified PITT technique. Our mean (SD) load to failure of the modified PITT technique was 157 (41) N, slightly higher than that reported for the classic PITT technique, albeit under a different setup.20 There was more variation in ultimate load to failure in our study than in previous studies, which could be secondary to tissue quality. As the modified PITT technique relies on surrounding tissue holding the biceps in place, this tissue would need to be of good quality and strength to obtain strong fixation. A possible concern is that placing stitches in the rotator interval could increase the risk of shoulder stiffness, but this has not been encountered clinically.

A more variable mechanism of failure was also found in the present study. Although half the specimens failed by suture pullout through the tendon, similar to what Lopez-Vidriero and colleagues20 described, 3 of our 8 specimens failed with the entire biceps tendon–suture construct pulling through the transverse ligament tissue, and 1 specimen failed by suture breakage. Although these numbers are too small for making definitive statements, our modified PITT technique may add some security to the tendon–suture construct. Such added security may be of particular value in the setting of poor-quality, diseased tendon tissue, and the construct may be more limited by the strength of surrounding tissues. In addition, if failure occurs at the suture transverse humeral ligament–rotator interval interface, more surrounding rotator interval tissue can be incorporated into the tenodesis to decrease the likelihood of failure through this mechanism.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a time zero study in a cadaveric model with simulated biomechanical loading. As such, it provided information only on initial fixation strength and could not prove any superior clinical outcomes or account for any biological changes with healing that occurred over time. Second, the study may have been underpowered, though sample size was chosen in accordance with other cadaveric biomechanical studies. Third, all procedures were performed in an open manner, simulating the arthroscopic approach. Particularly in the setting of the modified PITT technique, this represented a best case scenario. Spinal needles and subsequent sutures were easily passed under direct visualization through the transverse humeral ligament, rotator interval, and biceps tendon. There is likely marked variability in this step during arthroscopy in which visualization is more limited, as in the setting of concomitant procedures, such as subacromial decompression or rotator cuff repair. In addition, all tendons tested were normal in appearance and gave no indication of chronic degenerative changes.

Another study limitation is that we did not quantify bone mineral density, which if poor would have affected interference screw strength. However, mean specimen age was 55 years, minimizing chances of poor bone quality. In addition, 7 of the 8 failures in the interference screw group occurred not with pullout but at the screw–tendon junction, suggesting poor bone quality was not a significant factor. As tendon diameter was not measured before the procedures were performed, there is the possibility it could have been better in the modified PITT group and worse in the interference screw group because of tunnel crowding, as noted.

1. Alpantaki K, McLaughlin D, Karagogeos D, Hadjipavlou A, Kontakis G. Sympathetic and sensory neural elements in the tendon of the long head of the biceps. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1580-1583.

2. Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(11):645-656.

3. Khazzam M, George MS, Churchill RS, Kuhn JE. Disorders of the long head of biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):136-145.

4. Frost A, Zafar MS, Maffulli N. Tenotomy versus tenodesis in the management of pathologic lesions of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):828-833.

5. Hsu AR, Ghodadra NS, Provencher MT, Lewis PB, Bach BR. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a review of clinical outcomes and biomechanical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):326-332.

6. Slenker NR, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Dodson CC, Cohen SB. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):576-582.

7. Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Santangelo S, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1296-1306.

8. Millett PJ, Sanders B, Gobezie R, Braun S, Warner JJ. Interference screw vs. suture anchor fixation for open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: does it matter? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:121.

9. Patzer T, Rundic JM, Bobrowitsch E, Olender GD, Hurschler C, Schofer MD. Biomechanical comparison of arthroscopically performable techniques for suprapectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1036-1047.

10. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):170-176.

11. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

12. Klepps S, Hazrati Y, Flatow E. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(9):1040-1045.

13. Golish SR, Caldwell PE 3rd, Miller MD, et al. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for subpectoral tenodesis of the proximal biceps tendon: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1103-1108.

14. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. A biomechanical analysis of two biceps tenodesis fixation techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):861-866.

15. Slabaugh MA, Frank RM, Van Thiel GS, et al. Biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation: a biomechanical comparison of screw length and diameter. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(2):161-166.

16. Ozalay M, Akpinar S, Karaeminogullari O, et al. Mechanical strength of four different biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):992-998.

17. Patzer T, Santo G, Olender GD, Wellmann M, Hurschler C, Schofer MD. Suprapectoral or subpectoral position for biceps tenodesis: biomechanical comparison of four different techniques in both positions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):116-125.

18. Jayamoorthy T, Field JR, Costi JJ, Martin DK, Stanley RM, Hearn TC. Biceps tenodesis: a biomechanical study of fixation methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(2):160-164.

19. Kusma M, Dienst M, Eckert J, Steimer O, Kohn D. Tenodesis of the long head of biceps brachii: cyclic testing of five methods of fixation in a porcine model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):967-973.

20. Lopez-Vidriero E, Costic RS, Fu FH, Rodosky MW. Biomechanical evaluation of 2 arthroscopic biceps tenodeses: double anchor versus percutaneous intra-articular transtendon (PITT) techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):146-152.

21. Su WR, Budoff JE, Chiang CH, Lee CJ, Lin CL. Biomechanical study comparing biceps wedge tenodesis with other proximal long head of the biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(9):1498-1505.

22. Trenhaile SW. Biceptor Tenodesis System, Arthroscopic Biceps Tenodesis [operational instructions]. Andover, MA: Smith & Nephew; 2009:1-8.

23. Sekiya LC, Elkousy HA, Rodosky MW. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis using the percutaneous intra-articular transtendon technique. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1137-1141.

24. Elkousy HA, Fluhme DJ, O’Connor DP, Rodosky MW. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis using the percutaneous, intra-articular trans-tendon technique: preliminary results. Orthopedics. 2005;28(11):1316-1319.

25. Castagna A, Conti M, Mouhsine E, Bungaro P, Garofalo R. Arthroscopic biceps tendon tenodesis; the anchorage technical note. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(6):581-585.

26. Checchia SL, Doneux PS, Miyazaki AN, et al. Biceps tenodesis associated with arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(2):138-144.

27. Moros C, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Suture anchor and percutaneous intra-articular transtendon biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):177-179.

1. Alpantaki K, McLaughlin D, Karagogeos D, Hadjipavlou A, Kontakis G. Sympathetic and sensory neural elements in the tendon of the long head of the biceps. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1580-1583.

2. Nho SJ, Strauss EJ, Lenart BA, et al. Long head of the biceps tendinopathy: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(11):645-656.

3. Khazzam M, George MS, Churchill RS, Kuhn JE. Disorders of the long head of biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):136-145.

4. Frost A, Zafar MS, Maffulli N. Tenotomy versus tenodesis in the management of pathologic lesions of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):828-833.

5. Hsu AR, Ghodadra NS, Provencher MT, Lewis PB, Bach BR. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a review of clinical outcomes and biomechanical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):326-332.

6. Slenker NR, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Dodson CC, Cohen SB. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):576-582.

7. Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Santangelo S, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1296-1306.

8. Millett PJ, Sanders B, Gobezie R, Braun S, Warner JJ. Interference screw vs. suture anchor fixation for open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: does it matter? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:121.

9. Patzer T, Rundic JM, Bobrowitsch E, Olender GD, Hurschler C, Schofer MD. Biomechanical comparison of arthroscopically performable techniques for suprapectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(8):1036-1047.

10. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):170-176.

11. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

12. Klepps S, Hazrati Y, Flatow E. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(9):1040-1045.

13. Golish SR, Caldwell PE 3rd, Miller MD, et al. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for subpectoral tenodesis of the proximal biceps tendon: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1103-1108.

14. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. A biomechanical analysis of two biceps tenodesis fixation techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):861-866.

15. Slabaugh MA, Frank RM, Van Thiel GS, et al. Biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation: a biomechanical comparison of screw length and diameter. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(2):161-166.

16. Ozalay M, Akpinar S, Karaeminogullari O, et al. Mechanical strength of four different biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):992-998.

17. Patzer T, Santo G, Olender GD, Wellmann M, Hurschler C, Schofer MD. Suprapectoral or subpectoral position for biceps tenodesis: biomechanical comparison of four different techniques in both positions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):116-125.

18. Jayamoorthy T, Field JR, Costi JJ, Martin DK, Stanley RM, Hearn TC. Biceps tenodesis: a biomechanical study of fixation methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(2):160-164.

19. Kusma M, Dienst M, Eckert J, Steimer O, Kohn D. Tenodesis of the long head of biceps brachii: cyclic testing of five methods of fixation in a porcine model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):967-973.

20. Lopez-Vidriero E, Costic RS, Fu FH, Rodosky MW. Biomechanical evaluation of 2 arthroscopic biceps tenodeses: double anchor versus percutaneous intra-articular transtendon (PITT) techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):146-152.

21. Su WR, Budoff JE, Chiang CH, Lee CJ, Lin CL. Biomechanical study comparing biceps wedge tenodesis with other proximal long head of the biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(9):1498-1505.

22. Trenhaile SW. Biceptor Tenodesis System, Arthroscopic Biceps Tenodesis [operational instructions]. Andover, MA: Smith & Nephew; 2009:1-8.

23. Sekiya LC, Elkousy HA, Rodosky MW. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis using the percutaneous intra-articular transtendon technique. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1137-1141.

24. Elkousy HA, Fluhme DJ, O’Connor DP, Rodosky MW. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis using the percutaneous, intra-articular trans-tendon technique: preliminary results. Orthopedics. 2005;28(11):1316-1319.

25. Castagna A, Conti M, Mouhsine E, Bungaro P, Garofalo R. Arthroscopic biceps tendon tenodesis; the anchorage technical note. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(6):581-585.

26. Checchia SL, Doneux PS, Miyazaki AN, et al. Biceps tenodesis associated with arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(2):138-144.

27. Moros C, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Suture anchor and percutaneous intra-articular transtendon biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):177-179.

Is a Persistent Vacuum Phenomenon a Sign of Pseudarthrosis After Posterolateral Spinal Fusion?

The spinal vacuum sign or vacuum phenomenon (VP) is the radiographic finding of an air-density linear radiolucency in the intervertebral disc or vertebral body. The result of a gaseous accumulation, it is often a diagnostic sign of disc degeneration as well as a rare sign of infection, Schmorl node formation, or osteonecrosis.1,2 Although the VP was first described on plain radiographs, it is better seen on computed tomography (CT).3 Multiple studies have found a possible association between the VP and nonunion in diaphyseal fractures,4 ankylosing spondylitis,5,6 and lumbar spinal fusion.7

To our knowledge, no one has studied whether the intervertebral VP resolves after posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion in adults with degenerative spinal pathology, and no one has investigated the association between the persistence of the intervertebral VP and pseudarthrosis after posterolateral spinal fusion.

We conducted a study to determine whether the VP resolves after posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion procedures and whether persistence of the VP after fusion surgery is indicative of pseudarthrosis.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who had degenerative spinal stenosis with instability and the intervertebral vacuum sign on preoperative digital lumbar spine CT scans and who underwent posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion with or without instrumentation. Study inclusion criteria were lumbar spine CT at minimum 6-month follow-up after spinal fusion and preoperative and postoperative lumbar spine radiographs. Exclusion criteria were any type of interbody fusion procedure (anterior, posterior, transforaminal, lateral) at a level with the VP, age under 21 years, follow-up of less than 6 months, and incomplete radiographic records. As this was a retrospective study, patient consent was not required.

CT was performed with a 16-, 64-, or 128-slice multidetector CT scanner with effective tube current set at 250 to 320 mA, voltage set at 120 to 140 kV, and pitch set at 0.75 to 0.9. After axial acquisition of 3×3-mm isometric voxels, sagittal and coronal multiplanar images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 2 mm. Patient demographics, diagnoses, and surgical details were recorded. All digital lumbar spine CT scans and radiographs were initially screened on PACS (picture archiving and communication system) by the orthopedic spine surgery fellow at an academic medical institution; then they were reviewed on a radiology reading room monitor by 3 observers (senior radiologist, senior orthopedic spine surgeon, orthopedic spine surgery fellow). Axial images and sagittal and coronal reconstructed images of the preoperative and postoperative follow-up lumbar CT scans—together with the lateral and anteroposterior lumbar spine radiographs—were evaluated for the intervertebral VP. Mean (SD) follow-up (with CT to assess fusion) was 1.6 (0.86) years (range, 0.75-3.38 years). Fusion at each level was evaluated on the postoperative follow-up CT on axial images and sagittal and coronal reconstructed images; criteria for fusion were continuous bridging bone across posterolateral gutters and facets on one or both sides at each intervertebral level.8 Pseudarthrosis was recorded if there was no continuity of bridging bone across both posterolateral gutters and facets, a complete radiolucent line on both sides across a level, or lysis or loosening around screws. All recordings were made by consensus, or by majority decision in case of disagreement.

Presence of the VP at the lumbar levels not included in the fusion was also recorded on the preoperative and follow-up CT scan and radiographs.

Descriptive and inferential statistical tests were performed as applicable. Pearson χ2 test and Fischer exact test were used to evaluate if there was a significant association between the groups where the VP disappeared and persisted and fusion and pseudarthrosis. Significance was set at P < .05. Statistical analysis was performed with Stata Version 10.0.

Results

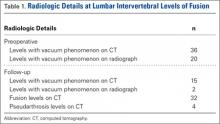

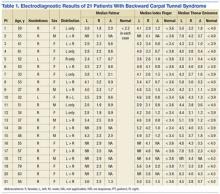

Using the preoperative lumbar spine CT scans of 18 patients (10 men, 8 women), we identified 36 cases of intervertebral levels exhibiting the VP (median positive vacuum sign levels per patient, 2; minimum, 1; maximum, 5) at the levels included in the fusion (Table 1). Mean (SD) age at surgery was 67.6 (9.4) years (range, 46.5-79.6 years). Mean (SD) radiologic follow-up was 1.6 (0.86) years (range, 0.75-3.38 years). All patients underwent lumbar fusion with local autograft, allograft, and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2. Spinal instrumentation was used in 16 of the 18 patients.

On preoperative CT, positive VP was diagnosed in the 36 cases as follows: L5–S1 (11 cases), L4–L5 (9 cases), L3–L4 (4 cases), L2–L3 (6 cases), L1–L2 (4 cases), and T12–L1 (2 cases). On follow-up CT, 15 cases showed persistence of the VP, and 21 cases showed disappearance of the VP (Table 1).

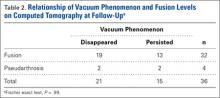

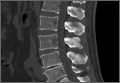

Evidence of spinal fusion was identified on follow-up CT in 32 (88.9%) of the 36 cases. In 3 of the 18 patients, nonunion was diagnosed. Of the 15 intervertebral cases in which the VP persisted, 13 (86.7%) showed evidence of fusion on CT, and 2 (13.3%) showed evidence of pseudarthrosis. Of the 21 intervertebral cases in which the VP disappeared, 19 (90.5%) showed evidence of fusion on CT, and 2 (9.5%) showed evidence of pseudarthrosis (Table 2). There was no significant difference in fusion rate or pseudarthrosis rate in the groups in which the VP persisted or disappeared (Fischer exact test, P = .99). There was no significant association between VP persistence or disappearance and sex, primary or revision surgery, or intervertebral level (Fischer exact test, P > .05). A case example is shown in the Figure.

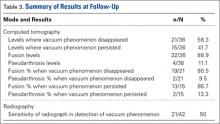

At levels not included in spinal fusion, CT identified the VP at 6 lumbar intervertebral levels before surgery and 11 levels at follow-up. The VP did not disappear at any level not included in the fusion. At follow-up, no new VP was identified in a segment included in fusion. Results are summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

The association of radiologic intervertebral VP and disc degeneration, first recognized by Knutsson1 in 1942, refers to the presence of gas, mainly containing nitrogen, in the crevices between or within vertebrae.2 The VP is more often seen in patients older than 50 years, on plain radiographs in hyperextension.9 CT is more sensitive than radiography in detecting the VP; Lardé and colleagues3 found it in about 50% of 50 patients on CT scans but in only 12% of patients on radiographs. The VP is visible because of the nitrogen gas that accumulates when there is a negative pressure within the disc space. Nitrogen emerges from the blood and moves into the disc space; perhaps the disc space opens, causing the negative pressure.1-3 On T1- or T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the VP is visible as a signal void. MRI, however, is less accurate than CT.10 In a study of 10 patients who had low back pain and more than 1 level of intradiscal VP, and who underwent supine MRI examinations at 0, 1, and 2 hours, Wang and colleagues11 found that, after prolonged supine positioning, the signal intensity of the vacuum was replaced by hyperintense fluid contents. D’Anastasi and colleagues,12 in a study of 20 patients who had lumbar vacuum phenomenon on CT and underwent MRI examinations, found a significant correlation between presence of intradiscal fluid and amount of bone marrow edema on MRI and degenerative endplate abnormalities on CT. In the present study, we found that, after the spinal fusion vacuum phenomenon disappeared in 58.3% of the lumbar levels and persisted in 41.7% on follow-up CT at the levels included in posterolateral fusion, there were 5 new levels, adjacent to the lumbar fusion, where the VP was seen on the follow-up CT.

We studied whether evidence of a persistent vacuum sign on CT is indicative of pseudarthrosis. Other authors have reported an association between the VP and nonunion in fractures4 and ankylosing spondylitis.5,6 In a study of 19 patients with diaphyseal fractures, Stallenberg and colleagues4 found that, in 7 of the 10 patients with nonunion, the VP was detected on CT at the nonunion site. Martel5 first reported on the intervertebral VP in a case of ankylosing spondylitis with spinal pseudarthrosis. Ten years later, in a study of 18 patients with advanced ankylosing spondylitis with spinal pseudarthrosis, Chan and colleagues6 identified the intervertebral VP on CT in 7 patients. Edwards and colleagues7 studied 15 patients with prior lumbar fusion with 17 positive intervertebral VP levels on CT and found that the vacuum disc sign was a strong predictor of lumbar nonunion as determined by surgical exploration. Mirovsky and colleagues13 identified the intravertebral vacuum cleft in 26 patients with an osteoporotic vertebral fracture treated with vertebroplasty and concluded that nonunion of the vertebral fracture could be identified by presence of the intravertebral vacuum cleft on radiography. In the present study, there was radiologic evidence of lumbar spinal fusion in 89% of disc levels with a preoperative positive intervertebral VP and pseudarthrosis in 11% of disc levels. The rate of fusion at levels with the VP was comparable to the rate at intervertebral levels without the phenomenon. These findings indicate that persistence of the VP after spinal fusion is not an indication that fusion has not been achieved. Preoperative VP also did not predispose to failure of fusion. That there is a persistent vacuum disc might imply that, even after successful fusion as seen on CT, some motion may be occurring at the disc level to cause a negative pressure phenomenon. Even in cases of facet fusion with bridging bone, there may still be motion at the disc level, as fusions can plastically deform (even with screws in), particularly in elderly osteopenic bone. We found no association between a persistent vacuum sign and pseudarthrosis. Our study findings are clinically useful even if the benefits are limited. These findings may help surgeons avoid misinterpreting this sign as an indication for additional surgery.