User login

Crisis in Medicine: Part 3. The Physician as the Captain—A Personal Touch

"Report to the Administrator’s Office for a discussion 7:00 am sharp,” reads the email on your phone. The phone log sheet from your administrator is handed to you as you are running to the operating room and reads, “Call back Mr. Smith’s health insurance company because your patient stayed overnight unexpectedly in the hospital, and if the return phone call is not received by 8:40 am the complete hospital stay will be disallowed.” The text message reads, “The head nurse from the emergency department wants to have a discussion with you tomorrow about what transpired in room 23 last night at 1:33 am.” Your physician assistant calls you because a recent history and physical examination from the out-of-state internist has not been cosigned by you, and, therefore, the patient is still in the admitting office; the admitting officer is waiting to go home and won’t accept the physician assistant’s signature.

This simple illustration of a surgeon’s typical morning is hardly hyperbole. Demands and finger-pointing are routine aspects of care, with a concurrent need to attribute blame and create a hostile work environment whether in the office, operating room, or floor of the hospital by anyone who can proudly say to the physician, “Gotcha!” The environment that produces this ethos is toxic and needs to be changed. While all members of a patient care team must be accountable, no member should be antagonistic toward another, and each member must feel a part of a working whole that is led by a competent, caring, and identifiable physician. Yes, the doctor must be the team captain; he or she must take back the reins of care immediately in order to provide the patient with the best possible outcome.

The loss of leadership can be traced back to the rise of regulatory controls put in place by government entities or local hospital administration to contain costs and limit liability. While the target goals of such measures are laudable, the negative impact on the doctor–patient relationship has been palpable and problematic and requires reassessment. The profession itself will be preserved by refocusing on the doctor–patient relationship and returning the physician to the role of team leader. Our patients deserve to feel as though their health care resides in the hands of the physician as the leader of a team that is pursuing a common goal: patient care with minimal distractions.

What, though, makes a great captain or leader? Sociologists have said that in a stable environment a “participatory model” of leadership is appropriate, while in a high-growth or changing environment, like the one in which we presently live, an “authoritative model” can be used to right the ship.1,2 Many types of leaders exist within both models. Leaders who are “innovators” will design and bring new ideas and original thought but may generate too many ideas that can’t be implemented practically in the hospital setting. Leaders who are “developers” will build and move forward to achieve challenging goals but may be impatient when ideas do not work and may be perceived in many interdisciplinary meetings as unruly. “Bureaucratic” leaders, presently seen in many leadership positions, can be classified as stabilizers and, while they may maintain equilibrium and keep things running smoothly, they often insist on a policy for every situation, resulting in stasis and sometimes even paralysis of the surgical center or hospital system.

I believe that health management and patient care require the simultaneous use of the authoritative and participatory models to encourage innovation, set attainable short- and long-term goals, and maintain the physician as the team leader. To lead effectively under this hybrid model, the physician must be accessible and fair, a teacher and a student, and a risk-taker, but, ultimately, at the end of every day, the physician must be accountable.

The time has come for physician leaders to assemble the troops: administrators, clinical providers, and nonclinical support staff. To paraphrase John Quincy Adams, in your actions inspire others to dream more and become more; then, and only then, are you an excellent leader. A secret to effective leadership is in finding one’s voice and acknowledging strengths and weaknesses. The leader must recruit other leaders who are very different from himself or herself and must listen to them deeply and trust them completely. One of our former first ladies said wisely, “A leader takes people where they want to go. A great leader takes people where they don’t necessarily want to go, but ought to be.” To truly find this leadership model, we as busy surgeons must spend some concentrated time away from our patients and exciting research to sit in the room with our nurses, administrators, and all other members of the health care community and listen to their thoughts and understand their concerns. We must understand policy to assess if it is reasonable and, if it is not, to reject it and propose more effective and appropriate rules for good care. We must remove from leadership positions those that do not have the interest of the patient as their primary concern. We must challenge any policy that does not have the patient’s interest and health as its raison d’etre. We must be proactive and not reactive. We must be ready to stand tall and politely question when dictated to unless evidence-based medical reasons can be presented.

You may ask, therefore, where should we lead? The answer is obvious! We need to be involved in every aspect of this great profession. We need to be the leaders of hospital systems, we need to be in charge of research institutions, and, as always, we need to be the chief of the operating room and the chief within each room as the team leader for the nurse, anesthesiologist, and nonclinical staff in order to safely guide our patients through the stress of a medical crisis or routine intervention. We need to find those of us with other degrees, whether MPH, MBA, MHA, or JD, and place those physicians in positions of business and political leadership as well as in leadership positions in hospitals and private practitioner offices. We need to encourage our medical students, residents, and fellows to continue their rigorous training to include an understanding of health care policy and economics so as to help manage and resolve the crisis at hand.

We must now navigate the sea of change to allow for continuity of care and not throw up our arms in despair. The role of physician as private practitioner or as full-time faculty member has its origins deeply imbedded in the roots of our profession, and this traditional role as caretaker and scientist must continue. But in this century, we need to be leaders in the political and business communities as well. This vision requires a new and fresh momentum. We cannot sit idly by as patient care becomes increasingly managed by nonphysicians. The time has come to use our unique position as doctors to frame the debate, participate in the discussion, and lead our profession and the management of health care toward calmer waters with compassion, science, and responsibility. To do this, we must demand transparency, proceed with respect, and require excellence from everyone around us and make sure it is demanded from all of us.◾

1. Morgan G. Developing the art of organizational analysis. In: Morgan G. Images of Organization. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1986:321-337.

2. Cherry KA. Leadership styles. About.com website. http://psychology.about.com/od/leadership/a/leadstyles.htm. Published 2006. Accessed October 20, 2015.

"Report to the Administrator’s Office for a discussion 7:00 am sharp,” reads the email on your phone. The phone log sheet from your administrator is handed to you as you are running to the operating room and reads, “Call back Mr. Smith’s health insurance company because your patient stayed overnight unexpectedly in the hospital, and if the return phone call is not received by 8:40 am the complete hospital stay will be disallowed.” The text message reads, “The head nurse from the emergency department wants to have a discussion with you tomorrow about what transpired in room 23 last night at 1:33 am.” Your physician assistant calls you because a recent history and physical examination from the out-of-state internist has not been cosigned by you, and, therefore, the patient is still in the admitting office; the admitting officer is waiting to go home and won’t accept the physician assistant’s signature.

This simple illustration of a surgeon’s typical morning is hardly hyperbole. Demands and finger-pointing are routine aspects of care, with a concurrent need to attribute blame and create a hostile work environment whether in the office, operating room, or floor of the hospital by anyone who can proudly say to the physician, “Gotcha!” The environment that produces this ethos is toxic and needs to be changed. While all members of a patient care team must be accountable, no member should be antagonistic toward another, and each member must feel a part of a working whole that is led by a competent, caring, and identifiable physician. Yes, the doctor must be the team captain; he or she must take back the reins of care immediately in order to provide the patient with the best possible outcome.

The loss of leadership can be traced back to the rise of regulatory controls put in place by government entities or local hospital administration to contain costs and limit liability. While the target goals of such measures are laudable, the negative impact on the doctor–patient relationship has been palpable and problematic and requires reassessment. The profession itself will be preserved by refocusing on the doctor–patient relationship and returning the physician to the role of team leader. Our patients deserve to feel as though their health care resides in the hands of the physician as the leader of a team that is pursuing a common goal: patient care with minimal distractions.

What, though, makes a great captain or leader? Sociologists have said that in a stable environment a “participatory model” of leadership is appropriate, while in a high-growth or changing environment, like the one in which we presently live, an “authoritative model” can be used to right the ship.1,2 Many types of leaders exist within both models. Leaders who are “innovators” will design and bring new ideas and original thought but may generate too many ideas that can’t be implemented practically in the hospital setting. Leaders who are “developers” will build and move forward to achieve challenging goals but may be impatient when ideas do not work and may be perceived in many interdisciplinary meetings as unruly. “Bureaucratic” leaders, presently seen in many leadership positions, can be classified as stabilizers and, while they may maintain equilibrium and keep things running smoothly, they often insist on a policy for every situation, resulting in stasis and sometimes even paralysis of the surgical center or hospital system.

I believe that health management and patient care require the simultaneous use of the authoritative and participatory models to encourage innovation, set attainable short- and long-term goals, and maintain the physician as the team leader. To lead effectively under this hybrid model, the physician must be accessible and fair, a teacher and a student, and a risk-taker, but, ultimately, at the end of every day, the physician must be accountable.

The time has come for physician leaders to assemble the troops: administrators, clinical providers, and nonclinical support staff. To paraphrase John Quincy Adams, in your actions inspire others to dream more and become more; then, and only then, are you an excellent leader. A secret to effective leadership is in finding one’s voice and acknowledging strengths and weaknesses. The leader must recruit other leaders who are very different from himself or herself and must listen to them deeply and trust them completely. One of our former first ladies said wisely, “A leader takes people where they want to go. A great leader takes people where they don’t necessarily want to go, but ought to be.” To truly find this leadership model, we as busy surgeons must spend some concentrated time away from our patients and exciting research to sit in the room with our nurses, administrators, and all other members of the health care community and listen to their thoughts and understand their concerns. We must understand policy to assess if it is reasonable and, if it is not, to reject it and propose more effective and appropriate rules for good care. We must remove from leadership positions those that do not have the interest of the patient as their primary concern. We must challenge any policy that does not have the patient’s interest and health as its raison d’etre. We must be proactive and not reactive. We must be ready to stand tall and politely question when dictated to unless evidence-based medical reasons can be presented.

You may ask, therefore, where should we lead? The answer is obvious! We need to be involved in every aspect of this great profession. We need to be the leaders of hospital systems, we need to be in charge of research institutions, and, as always, we need to be the chief of the operating room and the chief within each room as the team leader for the nurse, anesthesiologist, and nonclinical staff in order to safely guide our patients through the stress of a medical crisis or routine intervention. We need to find those of us with other degrees, whether MPH, MBA, MHA, or JD, and place those physicians in positions of business and political leadership as well as in leadership positions in hospitals and private practitioner offices. We need to encourage our medical students, residents, and fellows to continue their rigorous training to include an understanding of health care policy and economics so as to help manage and resolve the crisis at hand.

We must now navigate the sea of change to allow for continuity of care and not throw up our arms in despair. The role of physician as private practitioner or as full-time faculty member has its origins deeply imbedded in the roots of our profession, and this traditional role as caretaker and scientist must continue. But in this century, we need to be leaders in the political and business communities as well. This vision requires a new and fresh momentum. We cannot sit idly by as patient care becomes increasingly managed by nonphysicians. The time has come to use our unique position as doctors to frame the debate, participate in the discussion, and lead our profession and the management of health care toward calmer waters with compassion, science, and responsibility. To do this, we must demand transparency, proceed with respect, and require excellence from everyone around us and make sure it is demanded from all of us.◾

"Report to the Administrator’s Office for a discussion 7:00 am sharp,” reads the email on your phone. The phone log sheet from your administrator is handed to you as you are running to the operating room and reads, “Call back Mr. Smith’s health insurance company because your patient stayed overnight unexpectedly in the hospital, and if the return phone call is not received by 8:40 am the complete hospital stay will be disallowed.” The text message reads, “The head nurse from the emergency department wants to have a discussion with you tomorrow about what transpired in room 23 last night at 1:33 am.” Your physician assistant calls you because a recent history and physical examination from the out-of-state internist has not been cosigned by you, and, therefore, the patient is still in the admitting office; the admitting officer is waiting to go home and won’t accept the physician assistant’s signature.

This simple illustration of a surgeon’s typical morning is hardly hyperbole. Demands and finger-pointing are routine aspects of care, with a concurrent need to attribute blame and create a hostile work environment whether in the office, operating room, or floor of the hospital by anyone who can proudly say to the physician, “Gotcha!” The environment that produces this ethos is toxic and needs to be changed. While all members of a patient care team must be accountable, no member should be antagonistic toward another, and each member must feel a part of a working whole that is led by a competent, caring, and identifiable physician. Yes, the doctor must be the team captain; he or she must take back the reins of care immediately in order to provide the patient with the best possible outcome.

The loss of leadership can be traced back to the rise of regulatory controls put in place by government entities or local hospital administration to contain costs and limit liability. While the target goals of such measures are laudable, the negative impact on the doctor–patient relationship has been palpable and problematic and requires reassessment. The profession itself will be preserved by refocusing on the doctor–patient relationship and returning the physician to the role of team leader. Our patients deserve to feel as though their health care resides in the hands of the physician as the leader of a team that is pursuing a common goal: patient care with minimal distractions.

What, though, makes a great captain or leader? Sociologists have said that in a stable environment a “participatory model” of leadership is appropriate, while in a high-growth or changing environment, like the one in which we presently live, an “authoritative model” can be used to right the ship.1,2 Many types of leaders exist within both models. Leaders who are “innovators” will design and bring new ideas and original thought but may generate too many ideas that can’t be implemented practically in the hospital setting. Leaders who are “developers” will build and move forward to achieve challenging goals but may be impatient when ideas do not work and may be perceived in many interdisciplinary meetings as unruly. “Bureaucratic” leaders, presently seen in many leadership positions, can be classified as stabilizers and, while they may maintain equilibrium and keep things running smoothly, they often insist on a policy for every situation, resulting in stasis and sometimes even paralysis of the surgical center or hospital system.

I believe that health management and patient care require the simultaneous use of the authoritative and participatory models to encourage innovation, set attainable short- and long-term goals, and maintain the physician as the team leader. To lead effectively under this hybrid model, the physician must be accessible and fair, a teacher and a student, and a risk-taker, but, ultimately, at the end of every day, the physician must be accountable.

The time has come for physician leaders to assemble the troops: administrators, clinical providers, and nonclinical support staff. To paraphrase John Quincy Adams, in your actions inspire others to dream more and become more; then, and only then, are you an excellent leader. A secret to effective leadership is in finding one’s voice and acknowledging strengths and weaknesses. The leader must recruit other leaders who are very different from himself or herself and must listen to them deeply and trust them completely. One of our former first ladies said wisely, “A leader takes people where they want to go. A great leader takes people where they don’t necessarily want to go, but ought to be.” To truly find this leadership model, we as busy surgeons must spend some concentrated time away from our patients and exciting research to sit in the room with our nurses, administrators, and all other members of the health care community and listen to their thoughts and understand their concerns. We must understand policy to assess if it is reasonable and, if it is not, to reject it and propose more effective and appropriate rules for good care. We must remove from leadership positions those that do not have the interest of the patient as their primary concern. We must challenge any policy that does not have the patient’s interest and health as its raison d’etre. We must be proactive and not reactive. We must be ready to stand tall and politely question when dictated to unless evidence-based medical reasons can be presented.

You may ask, therefore, where should we lead? The answer is obvious! We need to be involved in every aspect of this great profession. We need to be the leaders of hospital systems, we need to be in charge of research institutions, and, as always, we need to be the chief of the operating room and the chief within each room as the team leader for the nurse, anesthesiologist, and nonclinical staff in order to safely guide our patients through the stress of a medical crisis or routine intervention. We need to find those of us with other degrees, whether MPH, MBA, MHA, or JD, and place those physicians in positions of business and political leadership as well as in leadership positions in hospitals and private practitioner offices. We need to encourage our medical students, residents, and fellows to continue their rigorous training to include an understanding of health care policy and economics so as to help manage and resolve the crisis at hand.

We must now navigate the sea of change to allow for continuity of care and not throw up our arms in despair. The role of physician as private practitioner or as full-time faculty member has its origins deeply imbedded in the roots of our profession, and this traditional role as caretaker and scientist must continue. But in this century, we need to be leaders in the political and business communities as well. This vision requires a new and fresh momentum. We cannot sit idly by as patient care becomes increasingly managed by nonphysicians. The time has come to use our unique position as doctors to frame the debate, participate in the discussion, and lead our profession and the management of health care toward calmer waters with compassion, science, and responsibility. To do this, we must demand transparency, proceed with respect, and require excellence from everyone around us and make sure it is demanded from all of us.◾

1. Morgan G. Developing the art of organizational analysis. In: Morgan G. Images of Organization. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1986:321-337.

2. Cherry KA. Leadership styles. About.com website. http://psychology.about.com/od/leadership/a/leadstyles.htm. Published 2006. Accessed October 20, 2015.

1. Morgan G. Developing the art of organizational analysis. In: Morgan G. Images of Organization. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1986:321-337.

2. Cherry KA. Leadership styles. About.com website. http://psychology.about.com/od/leadership/a/leadstyles.htm. Published 2006. Accessed October 20, 2015.

Excision of Symptomatic Spinous Process Nonunion in Adolescent Athletes

Fractures of the spinous process of the lower cervical spine or upper thoracic spine are frequently referred to as clay-shoveler’s fractures. Originally reported by Hall1 in 1940, these fractures were described in workers in Australia who dug drains in clay soil and threw the clay overhead with long shovels. Occasionally, the mud would not release from the shovel, causing excess force to be transmitted to the supraspinous ligaments and resulting in a forceful avulsion fracture of one or multiple spinous processes. The few reports following the earliest description in the literature frequently describe the mechanism of injury as being athletic in nature.2-4 The forceful contraction of the paraspinal and trapezius muscles on the supraspinous ligaments and the resultant attachment to the spinous processes make this a not uncommon injury during athletics, especially with a flexed position of the neck and shoulders. The resultant fracture or apophyseal avulsion is painful and often necessitates a visit to the physician, with plain films, computed tomography (CT) scans, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirming the diagnosis.5

Treatment of these fractures has not been well described, but frequently a period of rest followed by physical therapy will allow a return to activity. We present a series of adolescent athletes who developed nonunion of the fracture of the T1 spinous process with continued symptoms, despite rest and conservative therapy, and who underwent surgical excision of the ununited fragment.

Materials and Methods

We obtained institutional review board permission for this study and searched the surgical database between 2006 and 2013 for patients who had undergone resection of a spinous process nonunion. We collected demographic data on the patients, evaluated the radiographic studies, and reviewed operative reports and follow-up patient data.

Results

Dr. Hedequist operated on 3 patients with a spinous process nonunion over the study time period. The average age of the patients was 14 years; the location of the spinous process fracture was the T1 vertebra in all patients. Two patients sustained the injury while playing hockey and 1 during wrestling. The average duration of symptoms prior to operation was 10 months; all patients had seen physicians without a diagnosis prior to evaluation at out institution. All patients had a trial of physical therapy before surgery, and all had been unable to return to sport after injury secondary to pain.

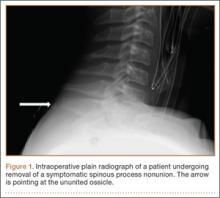

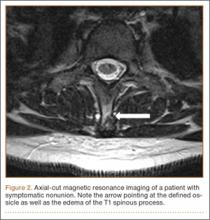

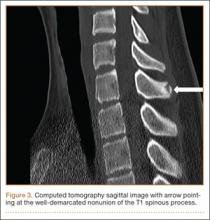

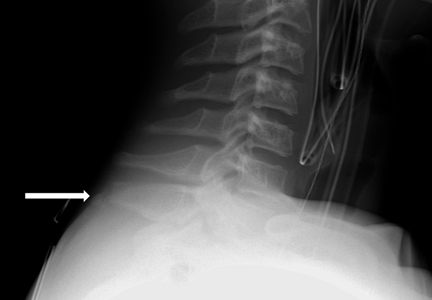

Examination of all patients revealed pain directly over the fracture site and accentuated by forward flexion of the neck and shoulders. Evaluation of injury plain films revealed a fracture fragment in 2 patients (Figure 1). All 3 patients underwent MRI and CT scans confirming the diagnosis. MRI confirmed areas of increased signal at the tip of the T1 spinous process, with inflammation in the supraspinous ligament directly at that region (Figure 2). The CT scans confirmed the presence of a bony fragment correlating with the tip of the T1 spinous process (Figure 3).

Surgery was performed under general endotracheal anesthesia via a midline incision over the affected area down to the spinous process. The supraspinous ligament was opened revealing an easily identified and definable ununited ossicle, which was removed without taking down the interspinous ligament. All 3 nonunions were noted to be atrophic with no evidence of surrounding inflammatory tissue or bursa. The residual end of the spinous process was smoothed down with a rongeur. Standard closure was performed. There were no surgical complications.

All patients had complete relief of pain at follow-up; 1 patient returned to full sports activity at 6 weeks and the other 2 returned to full sports activity at 3 months. There was no loss of cervical motion or trapezial strength at follow-up. All patients voiced satisfaction with the decision for surgical intervention.

Discussion

Clay-shoveler’s fracture is an injury well known to orthopedists. This fracture is thought to be caused by a forceful contraction of the thoracic paraspinal and trapezial muscles, causing an avulsion fracture with pain and frequently a “pop” experienced by the patient.1 Usually considered self-limiting injuries, treatment involves a period of rest and activity modification with occasional physical therapy. Return to sports has been reported with occasional pain but with patient satisfaction.3,5,6

Our series of patients represent a group of adolescent athletes who sustained spinous process fractures of the T1 vertebra and, despite a significant period of rest and activity modification, were unable to return to sports given their pain. The examination of these patients revealed focal tenderness at the tip of the spinous process. The diagnosis is made clinically, with radiographic studies confirming the diagnosis. In our series of patients, MRI was the original modality used to confirm injury to the area, with hyperintensity seen in the area of the supraspinous ligament and tip of the spinous process. CT confirmed the nonunion and presence of an ossicle in all patients. Surgical exposure of that area easily exposed the ununited ossicle, which was removed in all patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature describing surgical excision of an ununited spinous process fracture in adolescent athletes. The original descriptive case series by Hall1 states “in the minds of surgeons who have seen many of these cases that early operative removal of the fragments is the proper routine treatment.” Since that original series, we have not found articles in the literature that support surgical removal; however, persistent symptoms after fracture are described.5 It is not surprising that these patients developed pain at the site of the fracture given the forces acting in that area. The trapezial and paraspinal muscles acting on that area are forceful and repetitive during activities, especially sports. All our patients had pain with attempts at activity and all had had a significant period of rest. In a recent article, this injury was described in adolescents without the patients having clear relief of symptoms despite a period of inactivity.5 While physical therapy is therapeutic in some patients experiencing pain, it can be a source of aggravation due to neck and shoulder motion and muscle contraction. It is not surprising that therapy would not help in most cases, as neck and shoulder motion and muscle contraction are the sources of continuing discomfort.

Clinical practice suggests that most patients with spinous process fractures will become pain-free; however, that is not universal. This series demonstrates that a small subset of patients with this injury will continue to have significant symptoms despite a period of rest. In those patients who desire a pain-free return to sports, we recommend consideration of surgical excision after confirmation of nonunion with radiographic studies. The inherent risks of surgical treatment are minimal with this procedure, and the benefits include return to pain-free sports activity, with the resultant physical and psychosocial benefits for adolescent athletes.

1. Hall RDM. Clay-shoveler’s fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1940;22(1):63-75.

2. Herrick RT. Clay-shoveler’s fracture in power-lifting. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9(1):29-30.

3. Hetsroni I, Mann G, Dolev E, Morgenstern D, Nyska M. Clay shoveler’s fracture in a volleyball player. Phys Sportsmed. 2005;33(7):38-42.

4. Kaloostian PE, Kim JE, Calabresi PA, Bydon A, Witham T. Clay-shoveler’s fracture during indoor rock climbing. Orthopedics. 2013;36(3):e381-e383.

5. Yamaguchi KT Jr, Myung KS, Alonso MA, Skaggs DL. Clay-shoveler’s fracture equivalent in children. Spine. 2012;37(26):e1672-e1675.

6. Kang DH, Lee SH. Multiple spinous process fractures of the thoracic vertebrae (clay-shoveler’s fracture) in a beginning golfer: a case report. Spine. 2009;34(15):e534-e537.

Fractures of the spinous process of the lower cervical spine or upper thoracic spine are frequently referred to as clay-shoveler’s fractures. Originally reported by Hall1 in 1940, these fractures were described in workers in Australia who dug drains in clay soil and threw the clay overhead with long shovels. Occasionally, the mud would not release from the shovel, causing excess force to be transmitted to the supraspinous ligaments and resulting in a forceful avulsion fracture of one or multiple spinous processes. The few reports following the earliest description in the literature frequently describe the mechanism of injury as being athletic in nature.2-4 The forceful contraction of the paraspinal and trapezius muscles on the supraspinous ligaments and the resultant attachment to the spinous processes make this a not uncommon injury during athletics, especially with a flexed position of the neck and shoulders. The resultant fracture or apophyseal avulsion is painful and often necessitates a visit to the physician, with plain films, computed tomography (CT) scans, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirming the diagnosis.5

Treatment of these fractures has not been well described, but frequently a period of rest followed by physical therapy will allow a return to activity. We present a series of adolescent athletes who developed nonunion of the fracture of the T1 spinous process with continued symptoms, despite rest and conservative therapy, and who underwent surgical excision of the ununited fragment.

Materials and Methods

We obtained institutional review board permission for this study and searched the surgical database between 2006 and 2013 for patients who had undergone resection of a spinous process nonunion. We collected demographic data on the patients, evaluated the radiographic studies, and reviewed operative reports and follow-up patient data.

Results

Dr. Hedequist operated on 3 patients with a spinous process nonunion over the study time period. The average age of the patients was 14 years; the location of the spinous process fracture was the T1 vertebra in all patients. Two patients sustained the injury while playing hockey and 1 during wrestling. The average duration of symptoms prior to operation was 10 months; all patients had seen physicians without a diagnosis prior to evaluation at out institution. All patients had a trial of physical therapy before surgery, and all had been unable to return to sport after injury secondary to pain.

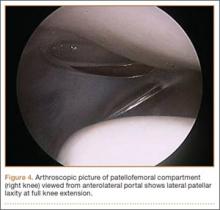

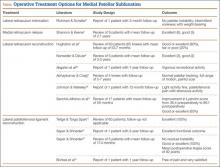

Examination of all patients revealed pain directly over the fracture site and accentuated by forward flexion of the neck and shoulders. Evaluation of injury plain films revealed a fracture fragment in 2 patients (Figure 1). All 3 patients underwent MRI and CT scans confirming the diagnosis. MRI confirmed areas of increased signal at the tip of the T1 spinous process, with inflammation in the supraspinous ligament directly at that region (Figure 2). The CT scans confirmed the presence of a bony fragment correlating with the tip of the T1 spinous process (Figure 3).

Surgery was performed under general endotracheal anesthesia via a midline incision over the affected area down to the spinous process. The supraspinous ligament was opened revealing an easily identified and definable ununited ossicle, which was removed without taking down the interspinous ligament. All 3 nonunions were noted to be atrophic with no evidence of surrounding inflammatory tissue or bursa. The residual end of the spinous process was smoothed down with a rongeur. Standard closure was performed. There were no surgical complications.

All patients had complete relief of pain at follow-up; 1 patient returned to full sports activity at 6 weeks and the other 2 returned to full sports activity at 3 months. There was no loss of cervical motion or trapezial strength at follow-up. All patients voiced satisfaction with the decision for surgical intervention.

Discussion

Clay-shoveler’s fracture is an injury well known to orthopedists. This fracture is thought to be caused by a forceful contraction of the thoracic paraspinal and trapezial muscles, causing an avulsion fracture with pain and frequently a “pop” experienced by the patient.1 Usually considered self-limiting injuries, treatment involves a period of rest and activity modification with occasional physical therapy. Return to sports has been reported with occasional pain but with patient satisfaction.3,5,6

Our series of patients represent a group of adolescent athletes who sustained spinous process fractures of the T1 vertebra and, despite a significant period of rest and activity modification, were unable to return to sports given their pain. The examination of these patients revealed focal tenderness at the tip of the spinous process. The diagnosis is made clinically, with radiographic studies confirming the diagnosis. In our series of patients, MRI was the original modality used to confirm injury to the area, with hyperintensity seen in the area of the supraspinous ligament and tip of the spinous process. CT confirmed the nonunion and presence of an ossicle in all patients. Surgical exposure of that area easily exposed the ununited ossicle, which was removed in all patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature describing surgical excision of an ununited spinous process fracture in adolescent athletes. The original descriptive case series by Hall1 states “in the minds of surgeons who have seen many of these cases that early operative removal of the fragments is the proper routine treatment.” Since that original series, we have not found articles in the literature that support surgical removal; however, persistent symptoms after fracture are described.5 It is not surprising that these patients developed pain at the site of the fracture given the forces acting in that area. The trapezial and paraspinal muscles acting on that area are forceful and repetitive during activities, especially sports. All our patients had pain with attempts at activity and all had had a significant period of rest. In a recent article, this injury was described in adolescents without the patients having clear relief of symptoms despite a period of inactivity.5 While physical therapy is therapeutic in some patients experiencing pain, it can be a source of aggravation due to neck and shoulder motion and muscle contraction. It is not surprising that therapy would not help in most cases, as neck and shoulder motion and muscle contraction are the sources of continuing discomfort.

Clinical practice suggests that most patients with spinous process fractures will become pain-free; however, that is not universal. This series demonstrates that a small subset of patients with this injury will continue to have significant symptoms despite a period of rest. In those patients who desire a pain-free return to sports, we recommend consideration of surgical excision after confirmation of nonunion with radiographic studies. The inherent risks of surgical treatment are minimal with this procedure, and the benefits include return to pain-free sports activity, with the resultant physical and psychosocial benefits for adolescent athletes.

Fractures of the spinous process of the lower cervical spine or upper thoracic spine are frequently referred to as clay-shoveler’s fractures. Originally reported by Hall1 in 1940, these fractures were described in workers in Australia who dug drains in clay soil and threw the clay overhead with long shovels. Occasionally, the mud would not release from the shovel, causing excess force to be transmitted to the supraspinous ligaments and resulting in a forceful avulsion fracture of one or multiple spinous processes. The few reports following the earliest description in the literature frequently describe the mechanism of injury as being athletic in nature.2-4 The forceful contraction of the paraspinal and trapezius muscles on the supraspinous ligaments and the resultant attachment to the spinous processes make this a not uncommon injury during athletics, especially with a flexed position of the neck and shoulders. The resultant fracture or apophyseal avulsion is painful and often necessitates a visit to the physician, with plain films, computed tomography (CT) scans, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirming the diagnosis.5

Treatment of these fractures has not been well described, but frequently a period of rest followed by physical therapy will allow a return to activity. We present a series of adolescent athletes who developed nonunion of the fracture of the T1 spinous process with continued symptoms, despite rest and conservative therapy, and who underwent surgical excision of the ununited fragment.

Materials and Methods

We obtained institutional review board permission for this study and searched the surgical database between 2006 and 2013 for patients who had undergone resection of a spinous process nonunion. We collected demographic data on the patients, evaluated the radiographic studies, and reviewed operative reports and follow-up patient data.

Results

Dr. Hedequist operated on 3 patients with a spinous process nonunion over the study time period. The average age of the patients was 14 years; the location of the spinous process fracture was the T1 vertebra in all patients. Two patients sustained the injury while playing hockey and 1 during wrestling. The average duration of symptoms prior to operation was 10 months; all patients had seen physicians without a diagnosis prior to evaluation at out institution. All patients had a trial of physical therapy before surgery, and all had been unable to return to sport after injury secondary to pain.

Examination of all patients revealed pain directly over the fracture site and accentuated by forward flexion of the neck and shoulders. Evaluation of injury plain films revealed a fracture fragment in 2 patients (Figure 1). All 3 patients underwent MRI and CT scans confirming the diagnosis. MRI confirmed areas of increased signal at the tip of the T1 spinous process, with inflammation in the supraspinous ligament directly at that region (Figure 2). The CT scans confirmed the presence of a bony fragment correlating with the tip of the T1 spinous process (Figure 3).

Surgery was performed under general endotracheal anesthesia via a midline incision over the affected area down to the spinous process. The supraspinous ligament was opened revealing an easily identified and definable ununited ossicle, which was removed without taking down the interspinous ligament. All 3 nonunions were noted to be atrophic with no evidence of surrounding inflammatory tissue or bursa. The residual end of the spinous process was smoothed down with a rongeur. Standard closure was performed. There were no surgical complications.

All patients had complete relief of pain at follow-up; 1 patient returned to full sports activity at 6 weeks and the other 2 returned to full sports activity at 3 months. There was no loss of cervical motion or trapezial strength at follow-up. All patients voiced satisfaction with the decision for surgical intervention.

Discussion

Clay-shoveler’s fracture is an injury well known to orthopedists. This fracture is thought to be caused by a forceful contraction of the thoracic paraspinal and trapezial muscles, causing an avulsion fracture with pain and frequently a “pop” experienced by the patient.1 Usually considered self-limiting injuries, treatment involves a period of rest and activity modification with occasional physical therapy. Return to sports has been reported with occasional pain but with patient satisfaction.3,5,6

Our series of patients represent a group of adolescent athletes who sustained spinous process fractures of the T1 vertebra and, despite a significant period of rest and activity modification, were unable to return to sports given their pain. The examination of these patients revealed focal tenderness at the tip of the spinous process. The diagnosis is made clinically, with radiographic studies confirming the diagnosis. In our series of patients, MRI was the original modality used to confirm injury to the area, with hyperintensity seen in the area of the supraspinous ligament and tip of the spinous process. CT confirmed the nonunion and presence of an ossicle in all patients. Surgical exposure of that area easily exposed the ununited ossicle, which was removed in all patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature describing surgical excision of an ununited spinous process fracture in adolescent athletes. The original descriptive case series by Hall1 states “in the minds of surgeons who have seen many of these cases that early operative removal of the fragments is the proper routine treatment.” Since that original series, we have not found articles in the literature that support surgical removal; however, persistent symptoms after fracture are described.5 It is not surprising that these patients developed pain at the site of the fracture given the forces acting in that area. The trapezial and paraspinal muscles acting on that area are forceful and repetitive during activities, especially sports. All our patients had pain with attempts at activity and all had had a significant period of rest. In a recent article, this injury was described in adolescents without the patients having clear relief of symptoms despite a period of inactivity.5 While physical therapy is therapeutic in some patients experiencing pain, it can be a source of aggravation due to neck and shoulder motion and muscle contraction. It is not surprising that therapy would not help in most cases, as neck and shoulder motion and muscle contraction are the sources of continuing discomfort.

Clinical practice suggests that most patients with spinous process fractures will become pain-free; however, that is not universal. This series demonstrates that a small subset of patients with this injury will continue to have significant symptoms despite a period of rest. In those patients who desire a pain-free return to sports, we recommend consideration of surgical excision after confirmation of nonunion with radiographic studies. The inherent risks of surgical treatment are minimal with this procedure, and the benefits include return to pain-free sports activity, with the resultant physical and psychosocial benefits for adolescent athletes.

1. Hall RDM. Clay-shoveler’s fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1940;22(1):63-75.

2. Herrick RT. Clay-shoveler’s fracture in power-lifting. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9(1):29-30.

3. Hetsroni I, Mann G, Dolev E, Morgenstern D, Nyska M. Clay shoveler’s fracture in a volleyball player. Phys Sportsmed. 2005;33(7):38-42.

4. Kaloostian PE, Kim JE, Calabresi PA, Bydon A, Witham T. Clay-shoveler’s fracture during indoor rock climbing. Orthopedics. 2013;36(3):e381-e383.

5. Yamaguchi KT Jr, Myung KS, Alonso MA, Skaggs DL. Clay-shoveler’s fracture equivalent in children. Spine. 2012;37(26):e1672-e1675.

6. Kang DH, Lee SH. Multiple spinous process fractures of the thoracic vertebrae (clay-shoveler’s fracture) in a beginning golfer: a case report. Spine. 2009;34(15):e534-e537.

1. Hall RDM. Clay-shoveler’s fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1940;22(1):63-75.

2. Herrick RT. Clay-shoveler’s fracture in power-lifting. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9(1):29-30.

3. Hetsroni I, Mann G, Dolev E, Morgenstern D, Nyska M. Clay shoveler’s fracture in a volleyball player. Phys Sportsmed. 2005;33(7):38-42.

4. Kaloostian PE, Kim JE, Calabresi PA, Bydon A, Witham T. Clay-shoveler’s fracture during indoor rock climbing. Orthopedics. 2013;36(3):e381-e383.

5. Yamaguchi KT Jr, Myung KS, Alonso MA, Skaggs DL. Clay-shoveler’s fracture equivalent in children. Spine. 2012;37(26):e1672-e1675.

6. Kang DH, Lee SH. Multiple spinous process fractures of the thoracic vertebrae (clay-shoveler’s fracture) in a beginning golfer: a case report. Spine. 2009;34(15):e534-e537.

Academic Characteristics of Orthopedic Team Physicians Affiliated With High School, Collegiate, and Professional Teams

The responsibilities of team physicians have increased dramatically since the early 19th century, when these physicians first appeared on the sidelines during football games.1 Although the primary role of the team physician is to care for the athlete, other responsibilities include administrative and legal duties, equipment- and environment-related duties, teaching, and communication with parents, coaches, and other physicians.2-4 These responsibilities differ greatly by the level of the athlete and the team being covered. For example, compared with high school and collegiate sport physicians, physicians caring for professional athletes may have increased interaction with the media.5

Despite the increasing demands and responsibilities of team physicians, it is important that they continue to advance the field of sports medicine through teaching and research.3,6 Team physicians have direct access to athletes at multiple levels of competition, from novice to professional, and therefore have a unique understanding of the injuries that commonly affect these athletes. Efforts to both teach and study the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these injuries have dramatically advanced the field of sports medicine. In fact, several advancements in sports medicine have come from team physicians, including advancements in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,7,8 shoulder arthroscopy,9 and “Tommy John” surgery,10 to name a few.

Given the important role of team physicians (particularly orthopedic team physicians) in advancing sports medicine, it is important to understand the degree to which team physicians at all levels of sport contribute to teaching and research.

We conducted a study to determine the overall academic involvement of orthopedic team physicians at all levels of sport, including the degree to which these physicians are affiliated with academic medical centers (by level of sport and by professional sport) and the quantity and impact of these physicians’ scientific publications. We hypothesized that orthopedic physician academic involvement would be higher at the professional level of sport than at the collegiate or high school level and that the degree of physician academic involvement would differ between professional sporting leagues.

Materials and Methods

In August 2012, we performed a comprehensive telephone- and Internet-based search to identify a sample of team physicians caring for athletes at the high school, collegiate, and professional levels of sport. Data were collected on all team physicians, regardless of medical specialty. We defined a physician as any person listed as having either a doctor of medicine (MD) or a doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO) degree. A physician listed as a team physician at 2 different levels of competition (high school, college, professional) was included in both cohorts. A physician listed as a team physician in 2 different professional sports leagues was included independently for both leagues. All other medical personnel, including athletic trainers, therapists, and nursing staff, were excluded. Data on our sample population were collected as follows:

1. High school. Performing a comprehensive database search through the US Department of Education, we generated a list of all 20,989 US schools that include grades 9 to 12.11 We then used a random number generator (random.org) to randomly select a sample of 120 high schools. These schools were contacted by telephone and asked to identify the team physician(s) for their sports teams. Twenty of these schools reported not having an athletic team, so we randomly generated a list of 20 additional high schools. High schools that had an athletic team but denied having a team physician were included in the analysis.

2. College. We used the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) website (ncaa.org) to generate a list of all colleges affiliated with the NCAA. Of these colleges, 347 were Division I, 316 were Division II, and 443 were Division III. The random.org random number generator was used to generate a list of 40 schools for each division, for a total of 120 schools. An Internet-based search was then performed to identify any and all team physicians caring for athletes at that particular school. In select cases, telephone calls were made to determine all the team physicians involved in the care of athletes at that institution.

3. Professional. Team physician data were collected for 4 of the most popular professional sporting leagues12: Major League Baseball (MLB), National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL), and National Hockey League (NHL). Each team’s official website was identified through its league website (mlb.com, nba.com, nfl.com, nhl.com), and the roster or directory listing of all team physicians was recorded. In 2 cases, the team’s medical personnel listing could not be retrieved through the Internet, and a telephone call had to be made to identify all team physicians. Team physicians were identified for 122 professional teams: 30 MLB, 30 NBA, 32 NFL, and 30 NHL.

For this study, all physicians were classified as either orthopedic or nonorthopedic. Orthopedic surgeons—the focus of this study—were defined as those who completed residency training in orthopedic surgery. Median number of orthopedic and nonorthopedic surgeons per team was calculated at the high school, collegiate, and professional levels.

After identifying all orthopedic team physicians, we performed additional Internet searches to determine any affiliation between each physician and an applicable academic medical center. Physicians were placed in 1 of 3 different categories based on “level” of academic affiliation. Orthopedists with no identifiable connection to an academic medical center were listed under none. The first 100 search results were studied before this determination was made. Orthopedists with any academic affiliation below the level of full professorship were placed in the category associate/assistant/adjunct professor, which included any physician who was an associate professor, adjunct professor, clinical instructor, or volunteer instructor at an academic medical center. Last, orthopedists listed as full professors were placed in the professor category.

Number of publications written by each orthopedic team physician was then calculated using SciVerse Scopus (scopus.com), a comprehensive abstract and citation database of research literature that offers complete coverage of the Medline and Embase databases.13 Scopus offers a Scopus Author Identifier, which assigns each author in Scopus a unique identification number.14 This number is based on an “algorithm that matches author names based on their affiliation, address, subject area, source title, dates of publication citations, and co-authors.”14 Authors whose names did not appear in Scopus were assumed to have no publications, and this was reported after cross-referencing with Medline to ensure no documents were missed. This study included all publications: original research articles, reviews, letters, and commentaries. Any level of authorship (first, second, etc) was included. All publications were scanned, and duplicate listings were not included. Median number of publications per orthopedic team physician was calculated at the high school, college, and professional levels.

We also determined the h-index for each orthopedic team physician. The h-index is used to measure the impact of the published work of a scholar: “A scientist has index h if h of his/her papers have at least h citations each, and the other papers have no more than h citations each.”15 For example, an h-index of 12 means that, out of an author’s total number of publications, 12 have been cited at least 12 times, and all of his or her other publications have been cited fewer than 12 times. All authors in Scopus are automatically assigned h-indexes, and we collected these numbers.16 Of note, citations for articles published before 1996 are not included in the h-index calculation. Median h-index score per orthopedic team physician was calculated at the high school, college, and professional levels.

Analysis of variance was used to compare continuous data (eg, number of publications per surgeon) across different groups (eg, physicians from respective sports). Chi-square tests were used to detect whole-number differences between groups (eg, difference in number of physicians per team across the various professional sports leagues). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

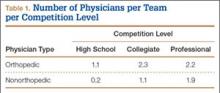

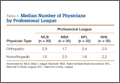

We identified 1054 team physicians among the 362 total high schools, colleges, and professional sports teams included in this study. Of the 1054 physicians, 678 (64%) were orthopedic surgeons (Table 1). Seventy-two (60%) of the 120 high schools did not have a team physician, whereas all the colleges and professional teams did. Number of orthopedic surgeons per team was higher at the collegiate level (2.29; range, 0-11) and professional level (2.21; range, 1-9) than at the high school level (1.11; range, 0-24) (Table 1). Median number of nonorthopedic surgeons was highest in professional sports (1.88; range, 0-9) followed by college sports (1.06; range, 0-9) and high school sports (0.16; range, 0-2) (Table 1).

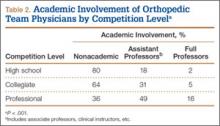

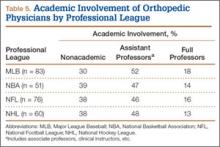

Of the 678 orthopedic team physicians, 298 (44%) were officially affiliated with an academic medical center, either as clinical instructor, associate/adjunct professor, or full professor. Percentage of orthopedists affiliated with an academic medical center was highest in professional sports (173/270, 64%) followed by collegiate sports (98/275, 36%) and high school sports (27/133, 20%) (P < .001, Table 2). Percentage of orthopedists identified as full professors was highest at the professional level (42/270, 16%) followed by the collegiate level (14/275, 5.1%) and the high school level (3/133, 2.3%) (P < .001, Table 2).

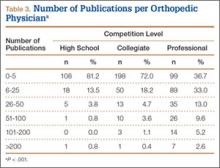

We found 12,036 publications written by the 678 orthopedic team physicians included in this study. Median number of publications per orthopedist was significantly higher in professional sports (30.6; range, 0-460) than in collegiate sports (10.7; range, 0-581) and high school sports (6.0; range, 0-220) (P < .001). Number of authors with more than 25 publications was highest at the professional level (82) followed by the collegiate level (27) and the high school level (7) (Table 3). Median number of publications per orthopedist was also higher at the professional level (12) than at the collegiate level (2) and high school level (1). Median h-index was higher among orthopedists in professional sports (7.1; range, 0-50) than at colleges (2.7; range, 0-63) and high schools (1.8; range, 0-32) (P < .001). Median h-index was also significantly higher at the professional level (5) than at the collegiate level (1) and high school level (0).

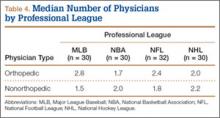

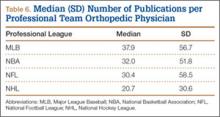

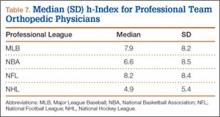

At the professional level of sports, we identified 499 team physicians (270 orthopedic, 54%; 229 nonorthopedic, 46%). Median number of orthopedic team physicians varied by sport, with MLB (2.8; range, 1-8) and the NFL (2.4; range, 1-4) having relatively more of these physicians than the NHL (2.0; range, 1-6) and the NBA (1.7; range, 1-9) (Table 4). Percentage of orthopedic team physicians affiliated with academic medical centers was highest in MLB (58/83, 69.9%) followed by the NFL (47/76, 61.8%), the NHL (37/60, 61.7%), and the NBA (31/51, 60.8%) (Table 5). Median number of publications by orthopedists also varied by sport, with the highest number in MLB (37.9; range, 0-225) followed by the NBA (32.0; range, 0-227) and the NFL (30.4; range, 0-460), with the lowest number in the NHL (20.7; range, 0-144) (Table 6). Median number of publications was the same (17.5) in MLB and the NFL and lower in the NBA (11) and the NHL (7.5). Median h-index was highest in the NFL (8.2; range, 0-50) and MLB (7.9; range, 0-32) followed by the NBA (6.6; range, 0-35) and the NHL (4.9; range, 0-20) (Table 7) Median h-index was the same (6) in MLB and the NFL and lower (3) in the NBA and the NHL.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of academic involvement and the research activities of orthopedic team physicians at the high school, college, and professional levels of sport. We found that, on average, there were almost twice as many orthopedists at the collegiate and professional levels than at the high school level—likely because 72 of the 120 high schools randomly selected did not have a team physician, despite having sports teams. We can attribute this to the organizational structure of teams in a high school setting, where it is fairly common that no medically educated health care provider is readily available for the student athletes.5 Although the median number of orthopedists was similar at the collegiate and professional levels, the number of nonorthopedic team physicians was higher at the professional level than at the collegiate level. Although most collegiate and professional teams have an internist and an orthopedist on staff, medical staff at the professional level may also include several subspecialists from a variety of medical fields (eg, dental medicine, ophthalmology, neurology).17

We found that a significantly larger proportion of orthopedists at the professional level (64%) were affiliated with academic medical centers as associate/adjunct professors and full professors compared with orthopedists at the collegiate level (36%) and high school level (20%). The academic relationship with collegiate teams was much lower than expected. Regarding professional sports, however, this finding confirmed our hypothesis, and the explanation is likely multifactorial and historical. Moreover, the median number of publications was higher for orthopedists at the professional level (30.8) than at the collegiate level (10.7) and high school level (6). In the late 1940s and early 1950s, many orthopedic team physicians entered into contracts with major universities.4 For many physicians, this contractual relationship increased their prestige, and some orthopedic groups were alleged to have endorsed scholarships at those schools.4 Given the high level of publicity and scrutiny surrounding medical decisions at the professional level of sports, it is possible that professional sports teams specifically seek orthopedists who are well respected within academia. Moreover, contracts between universities/academic medical centers and professional teams may mandate that a faculty member from that organization provide the orthopedic/medical care for the team. This may also increase the likelihood of professional teams being paired with academic orthopedic physicians. However, such contractual agreements are made between professional teams and large private medical groups as well.

In addition to measuring quantity of publications, we used the h-index to measure their quality. Following the same pattern as the publication rate, median h-index per orthopedic team physician was significantly higher at the professional level (7.1) than at the collegiate level (2.7) and high school level (1.8). As with publication volume, this is not entirely surprising, as h-index has been shown to correlate with academic rank in other surgical specialties,18 and there was a higher percentage of academic physicians at the professional level than at the collegiate and high school levels.

At the professional level of sports, 56% of all team physicians were orthopedic surgeons. Orthopedists caring for MLB teams had the highest median number of publications (37.9), followed by the NBA (32.0), the NFL (30.4), and the NHL (20.7). One likely explanation is the higher percentage of MLB physicians affiliated with academic medical centers. Regarding the h-index, MLB and NFL physicians had the highest values (7.9 and 8.2, respectively).

Our study had several limitations. First, we may not have captured data on all the team physicians at the high school, college, and professional levels. By following a detailed protocol in identifying surgeons, however, we tried to minimize the impact of any such omissions. In addition, teams may have had many unofficial consultants acting as team physicians, whether orthopedic or nonorthopedic, and, if these physicians were not listed in an official capacity, they may have been omitted from this study. We further realize that a true measure of academic productivity should also include book chapters and books published, research grants awarded, and patents registered. By including only peer-reviewed articles, we omitted these other criteria.

To our knowledge, the data presented here represent the first attempt to quantify the academic involvement and research productivity of orthopedic team physicians at the high school, college, and professional levels of sport. These data help us understand how research productivity varies by orthopedic team physicians at different levels of sport and may be useful to those considering a career as a team physician, as they can better evaluate their own productivity in the context of team physicians across different levels of competition.

1. Thorndike A. Athletic Injuries: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1956.

2. The team physician. A statement of the Committee on the Medical Aspects of Sports of the American Medical Association, September 1967. J School Health. 1967;37(10):510-514.

3. Team physician consensus statement. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(3):440-441.

4. Whiteside J, Andrews JR. Trends for the future as a team physician: Herodicus to hereafter. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(2):285-304.

5. Goforth M, Almquist J, Matney M, et al. Understanding organization structures of the college, university, high school, clinical, and professional settings. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(2):201-226.

6. Hughston JC. Want to be in sports medicine? Get involved. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7(2):79-80.

7. Marshall JL, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL, Reider B. The anterior cruciate ligament: a technique of repair and reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(143):97-106.

8. Clancy WG Jr, Nelson DA, Reider B, Narechania RG. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using one-third of the patellar ligament, augmented by extra-articular tendon transfers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(3):352-359.

9. Andrews JR, Carson WG Jr, McLeod WD. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(5):337-341.

10. Indelicato PA, Jobe FW, Kerlan RK, Carter VS, Shields CL, Lombardo SJ. Correctable elbow lesions in professional baseball players: a review of 25 cases. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7(1):72-75.

11. Elementary/Secondary Information System (EISi). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education website. http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/elsi/. Accessed September 21, 2015.

12. Corso RA; Harris Interactive. Football is America’s favorite sport as lead over baseball continues to grow; college football and auto racing come next. Harris Interactive website. http://www.harrisinteractive.com/vault/Harris Poll 9 - Favorite sport_1.25.12.pdf. Harris Poll 9, January 25, 2012. Accessed September 21, 2015.

13. [Scopus content]. Elsevier website. http://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus/content. Accessed September 21, 2015.

14. Scopus Author Identifier. Scopus website. http://help.scopus.com/Content/h_autsrch_intro.htm. Accessed October 5, 2015.

15. Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16569-16572.

16. Author Evaluator h Index Tab. Scopus website. http://help.scopus.com/Content/h_auteval_hindex.htm. Accessed October 5, 2015.

17. Boyd JL. Understanding the politics of being a team physician. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(2):161-172.

18. Lee J, Kraus KL, Couldwell WT. Use of the h index in neurosurgery. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(2):387-

The responsibilities of team physicians have increased dramatically since the early 19th century, when these physicians first appeared on the sidelines during football games.1 Although the primary role of the team physician is to care for the athlete, other responsibilities include administrative and legal duties, equipment- and environment-related duties, teaching, and communication with parents, coaches, and other physicians.2-4 These responsibilities differ greatly by the level of the athlete and the team being covered. For example, compared with high school and collegiate sport physicians, physicians caring for professional athletes may have increased interaction with the media.5

Despite the increasing demands and responsibilities of team physicians, it is important that they continue to advance the field of sports medicine through teaching and research.3,6 Team physicians have direct access to athletes at multiple levels of competition, from novice to professional, and therefore have a unique understanding of the injuries that commonly affect these athletes. Efforts to both teach and study the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these injuries have dramatically advanced the field of sports medicine. In fact, several advancements in sports medicine have come from team physicians, including advancements in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,7,8 shoulder arthroscopy,9 and “Tommy John” surgery,10 to name a few.

Given the important role of team physicians (particularly orthopedic team physicians) in advancing sports medicine, it is important to understand the degree to which team physicians at all levels of sport contribute to teaching and research.

We conducted a study to determine the overall academic involvement of orthopedic team physicians at all levels of sport, including the degree to which these physicians are affiliated with academic medical centers (by level of sport and by professional sport) and the quantity and impact of these physicians’ scientific publications. We hypothesized that orthopedic physician academic involvement would be higher at the professional level of sport than at the collegiate or high school level and that the degree of physician academic involvement would differ between professional sporting leagues.

Materials and Methods

In August 2012, we performed a comprehensive telephone- and Internet-based search to identify a sample of team physicians caring for athletes at the high school, collegiate, and professional levels of sport. Data were collected on all team physicians, regardless of medical specialty. We defined a physician as any person listed as having either a doctor of medicine (MD) or a doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO) degree. A physician listed as a team physician at 2 different levels of competition (high school, college, professional) was included in both cohorts. A physician listed as a team physician in 2 different professional sports leagues was included independently for both leagues. All other medical personnel, including athletic trainers, therapists, and nursing staff, were excluded. Data on our sample population were collected as follows:

1. High school. Performing a comprehensive database search through the US Department of Education, we generated a list of all 20,989 US schools that include grades 9 to 12.11 We then used a random number generator (random.org) to randomly select a sample of 120 high schools. These schools were contacted by telephone and asked to identify the team physician(s) for their sports teams. Twenty of these schools reported not having an athletic team, so we randomly generated a list of 20 additional high schools. High schools that had an athletic team but denied having a team physician were included in the analysis.

2. College. We used the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) website (ncaa.org) to generate a list of all colleges affiliated with the NCAA. Of these colleges, 347 were Division I, 316 were Division II, and 443 were Division III. The random.org random number generator was used to generate a list of 40 schools for each division, for a total of 120 schools. An Internet-based search was then performed to identify any and all team physicians caring for athletes at that particular school. In select cases, telephone calls were made to determine all the team physicians involved in the care of athletes at that institution.

3. Professional. Team physician data were collected for 4 of the most popular professional sporting leagues12: Major League Baseball (MLB), National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL), and National Hockey League (NHL). Each team’s official website was identified through its league website (mlb.com, nba.com, nfl.com, nhl.com), and the roster or directory listing of all team physicians was recorded. In 2 cases, the team’s medical personnel listing could not be retrieved through the Internet, and a telephone call had to be made to identify all team physicians. Team physicians were identified for 122 professional teams: 30 MLB, 30 NBA, 32 NFL, and 30 NHL.

For this study, all physicians were classified as either orthopedic or nonorthopedic. Orthopedic surgeons—the focus of this study—were defined as those who completed residency training in orthopedic surgery. Median number of orthopedic and nonorthopedic surgeons per team was calculated at the high school, collegiate, and professional levels.

After identifying all orthopedic team physicians, we performed additional Internet searches to determine any affiliation between each physician and an applicable academic medical center. Physicians were placed in 1 of 3 different categories based on “level” of academic affiliation. Orthopedists with no identifiable connection to an academic medical center were listed under none. The first 100 search results were studied before this determination was made. Orthopedists with any academic affiliation below the level of full professorship were placed in the category associate/assistant/adjunct professor, which included any physician who was an associate professor, adjunct professor, clinical instructor, or volunteer instructor at an academic medical center. Last, orthopedists listed as full professors were placed in the professor category.

Number of publications written by each orthopedic team physician was then calculated using SciVerse Scopus (scopus.com), a comprehensive abstract and citation database of research literature that offers complete coverage of the Medline and Embase databases.13 Scopus offers a Scopus Author Identifier, which assigns each author in Scopus a unique identification number.14 This number is based on an “algorithm that matches author names based on their affiliation, address, subject area, source title, dates of publication citations, and co-authors.”14 Authors whose names did not appear in Scopus were assumed to have no publications, and this was reported after cross-referencing with Medline to ensure no documents were missed. This study included all publications: original research articles, reviews, letters, and commentaries. Any level of authorship (first, second, etc) was included. All publications were scanned, and duplicate listings were not included. Median number of publications per orthopedic team physician was calculated at the high school, college, and professional levels.

We also determined the h-index for each orthopedic team physician. The h-index is used to measure the impact of the published work of a scholar: “A scientist has index h if h of his/her papers have at least h citations each, and the other papers have no more than h citations each.”15 For example, an h-index of 12 means that, out of an author’s total number of publications, 12 have been cited at least 12 times, and all of his or her other publications have been cited fewer than 12 times. All authors in Scopus are automatically assigned h-indexes, and we collected these numbers.16 Of note, citations for articles published before 1996 are not included in the h-index calculation. Median h-index score per orthopedic team physician was calculated at the high school, college, and professional levels.

Analysis of variance was used to compare continuous data (eg, number of publications per surgeon) across different groups (eg, physicians from respective sports). Chi-square tests were used to detect whole-number differences between groups (eg, difference in number of physicians per team across the various professional sports leagues). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

We identified 1054 team physicians among the 362 total high schools, colleges, and professional sports teams included in this study. Of the 1054 physicians, 678 (64%) were orthopedic surgeons (Table 1). Seventy-two (60%) of the 120 high schools did not have a team physician, whereas all the colleges and professional teams did. Number of orthopedic surgeons per team was higher at the collegiate level (2.29; range, 0-11) and professional level (2.21; range, 1-9) than at the high school level (1.11; range, 0-24) (Table 1). Median number of nonorthopedic surgeons was highest in professional sports (1.88; range, 0-9) followed by college sports (1.06; range, 0-9) and high school sports (0.16; range, 0-2) (Table 1).

Of the 678 orthopedic team physicians, 298 (44%) were officially affiliated with an academic medical center, either as clinical instructor, associate/adjunct professor, or full professor. Percentage of orthopedists affiliated with an academic medical center was highest in professional sports (173/270, 64%) followed by collegiate sports (98/275, 36%) and high school sports (27/133, 20%) (P < .001, Table 2). Percentage of orthopedists identified as full professors was highest at the professional level (42/270, 16%) followed by the collegiate level (14/275, 5.1%) and the high school level (3/133, 2.3%) (P < .001, Table 2).

We found 12,036 publications written by the 678 orthopedic team physicians included in this study. Median number of publications per orthopedist was significantly higher in professional sports (30.6; range, 0-460) than in collegiate sports (10.7; range, 0-581) and high school sports (6.0; range, 0-220) (P < .001). Number of authors with more than 25 publications was highest at the professional level (82) followed by the collegiate level (27) and the high school level (7) (Table 3). Median number of publications per orthopedist was also higher at the professional level (12) than at the collegiate level (2) and high school level (1). Median h-index was higher among orthopedists in professional sports (7.1; range, 0-50) than at colleges (2.7; range, 0-63) and high schools (1.8; range, 0-32) (P < .001). Median h-index was also significantly higher at the professional level (5) than at the collegiate level (1) and high school level (0).

At the professional level of sports, we identified 499 team physicians (270 orthopedic, 54%; 229 nonorthopedic, 46%). Median number of orthopedic team physicians varied by sport, with MLB (2.8; range, 1-8) and the NFL (2.4; range, 1-4) having relatively more of these physicians than the NHL (2.0; range, 1-6) and the NBA (1.7; range, 1-9) (Table 4). Percentage of orthopedic team physicians affiliated with academic medical centers was highest in MLB (58/83, 69.9%) followed by the NFL (47/76, 61.8%), the NHL (37/60, 61.7%), and the NBA (31/51, 60.8%) (Table 5). Median number of publications by orthopedists also varied by sport, with the highest number in MLB (37.9; range, 0-225) followed by the NBA (32.0; range, 0-227) and the NFL (30.4; range, 0-460), with the lowest number in the NHL (20.7; range, 0-144) (Table 6). Median number of publications was the same (17.5) in MLB and the NFL and lower in the NBA (11) and the NHL (7.5). Median h-index was highest in the NFL (8.2; range, 0-50) and MLB (7.9; range, 0-32) followed by the NBA (6.6; range, 0-35) and the NHL (4.9; range, 0-20) (Table 7) Median h-index was the same (6) in MLB and the NFL and lower (3) in the NBA and the NHL.

Discussion